The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

The Ten Best American Essays Since 1950, According to Robert Atwan

in Books , Literature | November 15th, 2012 3 Comments

“Essays can be lots of things, maybe too many things,” writes Atwan in his foreward to the 2012 installment in the Best American series, “but at the core of the genre is an unmistakable receptivity to the ever-shifting processes of our minds and moods. If there is any essential characteristic we can attribute to the essay, it may be this: that the truest examples of the form enact that ever-shifting process, and in that enactment we can find the basis for the essay’s qualification to be regarded seriously as imaginative literature and the essayist’s claim to be taken seriously as a creative writer.”

In 2001 Atwan and Joyce Carol Oates took on the daunting task of tracing that ever-shifting process through the previous 100 years for The Best American Essays of the Century . Recently Atwan returned with a more focused selection for Publishers Weekly : “The Top 10 Essays Since 1950.” To pare it all down to such a small number, Atwan decided to reserve the “New Journalism” category, with its many memorable works by Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Michael Herr and others, for some future list. He also made a point of selecting the best essays , as opposed to examples from the best essayists. “A list of the top ten essayists since 1950 would feature some different writers.”

We were interested to see that six of the ten best essays are available for free reading online. Here is Atwan’s list, along with links to those essays that are on the Web:

- James Baldwin, “Notes of a Native Son,” 1955 (Read it here .)

- Norman Mailer, “The White Negro,” 1957 (Read it here .)

- Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” 1964 (Read it here .)

- John McPhee, “The Search for Marvin Gardens,” 1972 (Read it here with a subscription.)

- Joan Didion, “The White Album,” 1979

- Annie Dillard, “Total Eclipse,” 1982

- Phillip Lopate, “Against Joie de Vivre,” 1986 (Read it here .)

- Edward Hoagland, “Heaven and Nature,” 1988

- Jo Ann Beard, “The Fourth State of Matter,” 1996 (Read it here .)

- David Foster Wallace, “Consider the Lobster,” 2004 (Read it here in a version different from the one published in his 2005 book of the same name.)

“To my mind,” writes Atwan in his article, “the best essays are deeply personal (that doesn’t necessarily mean autobiographical) and deeply engaged with issues and ideas. And the best essays show that the name of the genre is also a verb, so they demonstrate a mind in process–reflecting, trying-out, essaying.”

To read more of Atwan’s commentary, see his article in Publishers Weekly .

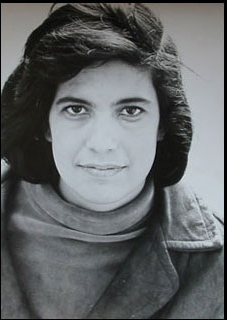

The photo above of Susan Sontag was taken by Peter Hujar in 1966.

Related Content:

30 Free Essays & Stories by David Foster Wallace on the Web

by Mike Springer | Permalink | Comments (3) |

Related posts:

Comments (3), 3 comments so far.

Check out Michael Ventura’s HEAR THAT LONG SNAKE MOAN: The VooDoo Origins of Rock n’ Roll

Wow I think there’s other greater ones out there. Just need to find them.

Boise mulberry bags uk http://www.cool-mulberrybags.info/

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Receive our newsletter!

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Americans and Brits Have Been Fighting Over the English Language for Centuries. Here’s How It Started

T he British and Americans have never gotten along very well where the English language is concerned. British mockery and indignation over what Americans were doing with and to the language began long before Independence, but after that it blossomed into a fully-fledged, ill-spirited, relentless attack that is still going on today. The conservative British politician and Brexit supporter Jacob Rees-Mogg, for example, has been defended as “one who dares to eschew the current, Americanized, mode of behaviour, speech, and dress.” In our own time, as has been the case for more than two centuries, fights about nationalism easily turn into skirmishes over language.

British ridicule of American ways of speaking became a vitriolic and crowded sport in the 18th and 19th centuries. New American words were springing up seemingly out of nowhere, and the British had no clue what many of them meant. Although he greatly admired America and Americans, the expatriate Scottish churchman John Witherspoon, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and member of Congress, had no taste for the language he heard cropping up in all walks of life in the country. “I have heard in this country,” he wrote in 1781, “in the senate, at the bar, and from the pulpit, and see daily in dissertations from the press, errors in grammar, improprieties and vulgarisms which hardly any person of the same class in point of rank and literature would have fallen into in Great Britain.” Among the Americanisms he said he heard everywhere were the use of “every” instead of “every one” and “mad” for “angry.” He particularly disliked “this here” or “that there.”

The British cringed over new American accents, coinages and vulgarisms. Prophets of doom flourished; the English language in America was going to disappear. “Their language will become as independent of England, as they themselves are,” wrote Jonathan Boucher, an English clergyman living in Maryland. Frances Trollope, mother of the novelist Anthony Trollope, was disgusted by “strange uncouth phrases and pronunciation” when she travelled in America in 1832. “Here then is the ruination of our classic English tongue,” mourned the British engineer, John Mactaggart. Even Thomas Jefferson found himself on the receiving end of an avalanche of British mockery, as The London Magazine in 1787 raged against his propensity to coin Americanisms: “For shame, Mr. Jefferson. Why, after trampling upon the honour of our country, and representing it as little better than a land of barbarism – why, we say, perpetually trample also upon the very grammar of our language? … Freely, good sir, will we forgive all your attacks, impotent as they are illiberal, upon our national character; but for the future, spare – O spare, we beseech you, our mother-tongue!”

But such protests did not stop Americans from telling the British to mind their own business, as they continued to use the language the way they felt they needed to in building their nation.

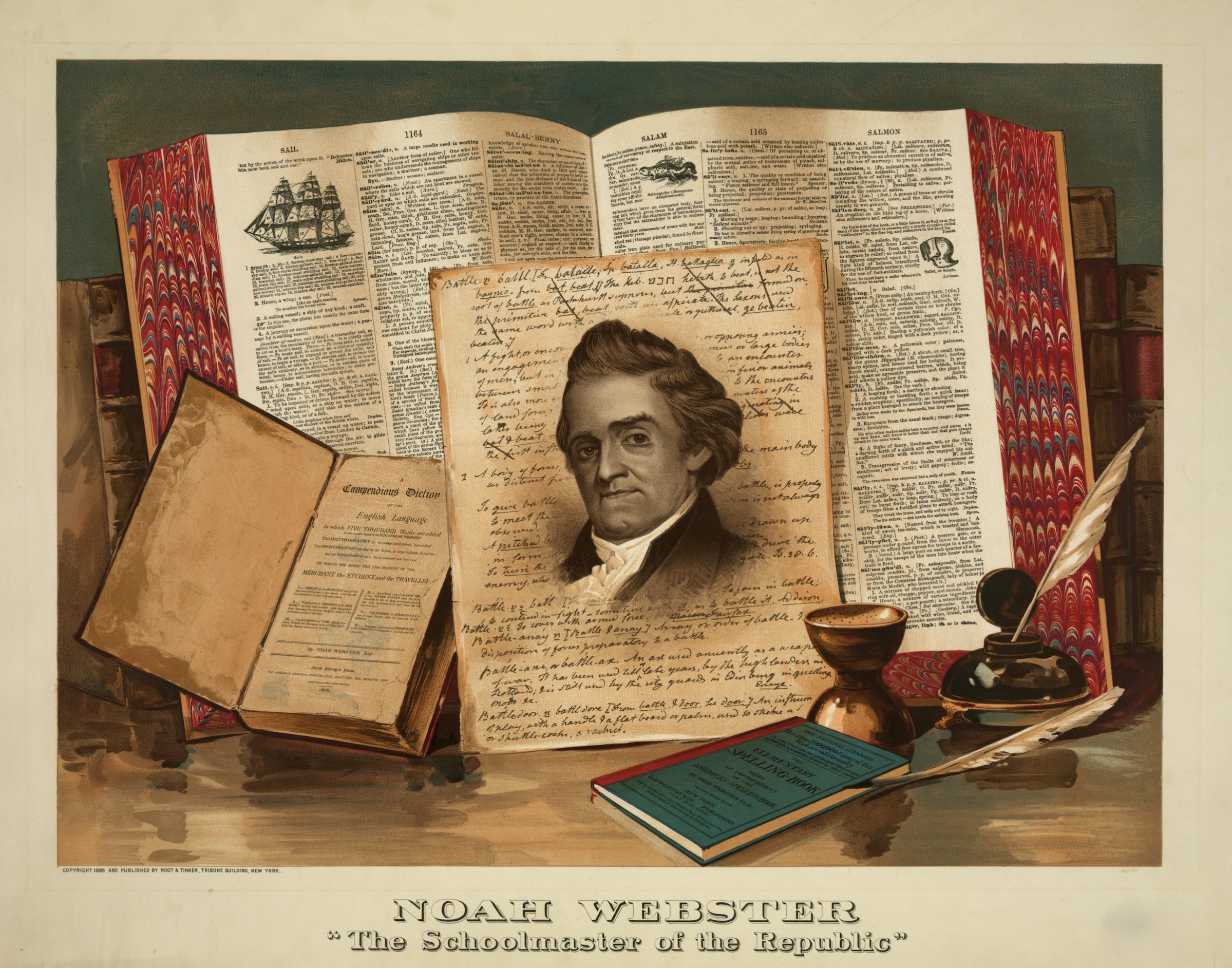

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Independence, it was felt by many, was a cultural as well as political matter that could never be complete without Americans taking pride in their own language. On the part of the more zealous American patriots like Thomas Jefferson and Noah Webster, the goal was national unity fostered by a conviction that Americans now ought to own and possess their own language. Jefferson led the charge by declaring war against Samuel Johnson’s famous Dictionary of the English Language , which continued to reign supreme for a century after its publication in 1755. Unless Johnson were toppled from his perch as the sage of the English language, he argued, America could remain hostage to British English deep into the 19th century. Webster, the self-styled grammarian who egotistically claimed for himself the role of “prophet of language to the American people,” was by far the most hostile to British interference in the development of the American language. He wrote an essay entitled, “English Corruption of the American Language,” casting Johnson as “the insidious Delilah by which the Samsons of our country are shorn of their locks.”

“Great Britain, whose children we are,” he claimed, “and whose language we speak, should no longer be our standard; for the taste of her writers is already corrupted, and her language on the decline.”

Yet, not all Americans were on board with Webster’s ideas and many Americans fought back, thoroughly and lastingly mocking him for his egregious reforms of the language, especially spelling, as a way of banishing the persistent American subservience to British culture. Pointing to him, one of his many American enemies remarked, “I expect to encounter the displeasure of our American reformers, who think we ought to throw off our native tongue as one of the badges of English servitude, and establish a new tongue for ourselves. … the best scholars in our country treat such a scheme with derision.”

We have to give it to Webster that he did write, as he made a point of putting it in his title, the first comprehensive unabridged “ American ” dictionary of the language. That effort, such as it was, 30 years in the making, brought on the golden age of American dictionaries — that is, those written in the U.S. The great historical irony, in light of decades of British ridicule of what Americans were doing with the language, is that Americans, like Webster’s superior and forgotten lexicographical rival Joseph Emerson Worcester, quickly surpassed British writers of dictionaries and continued to do so for more than half a century, until the birth of the monumental Oxford English Dictionary finally began to replace Johnson’s as Britain’s national dictionary.

Nonetheless, the flow of bad blood shed throughout the tortuous language and dictionary wars in the 19th century continued well into the 20th century, confirming that America and Britain were then and still are, as is often said, two nations “divided by a common language.” Divided, indeed, as with the same language they have always been able to understand their insults of one another.

Peter Martin is the author of the book The Dictionary Wars: The American Fight over the English Language (Princeton University Press 2019). He is also the author of the biographies Samuel Johnson and A Life of James Boswell . He has taught English literature in the United States and England.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

- Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt

- Asking Analytical Questions

- Introductions

- What Do Introductions Across the Disciplines Have in Common?

- Anatomy of a Body Paragraph

- Transitions

- Tips for Organizing Your Essay

- Counterargument

- Conclusions

- Strategies for Essay Writing: Downloadable PDFs

- Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

What Makes a Great American Essay?

Talking to phillip lopate about thwarted expectations, emerson, and the 21st-century essay boom.

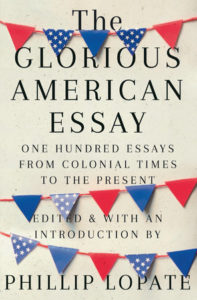

Phillip Lopate spoke to Literary Hub about the new anthology he has edited, The Glorious American Essay . He recounts his own development from an “unpatriotic” young man to someone, later in life, who would embrace such writers as Ralph Waldo Emerson, who personified the simultaneous darkness and optimism underlying the history of the United States. Lopate looks back to the Puritans and forward to writers like Wesley Yang and Jia Tolentino. What is the next face of the essay form?

Literary Hub: We’re at a point, politically speaking, when disagreements about the meaning of the word “American” are particularly vehement. What does the term mean to you in 2020? How has your understanding of the word evolved?

Phillip Lopate : First of all, I am fully aware that even using the word “American” to refer only to the United States is something of an insult to Latin American countries, and if I had said “North American” to signify the US, that might have offended Canadians. Still, I went ahead and put “American” in the title as a synonym for the United States, because I wanted to invoke that powerful positive myth of America as an idea, a democratic aspiration for the world, as well as an imperialist juggernaut replete with many unresolved social inequities, in negative terms.

I will admit that when I was younger, I tended to be very unpatriotic and critical of my country, although once I started to travel abroad and witness authoritarian regimes like Spain under Franco, I could never sign on to the fear that a fascist US was just around the corner. I came to the conclusion that we have our faults, but our virtues as well.

The more I’ve become interested in American history, the more I’ve seen how today’s problems and possible solutions are nothing new, but keep returning in cycles: economic booms and recessions, anti-immigrant sentiment, regional competition, racist Jim Crow policies followed by human rights advances, vigorous federal regulations and pendulum swings away from governmental intervention.

Part of the thrill in putting together this anthology was to see it operating simultaneously on two tracks: first, it would record the development of a literary form that I loved, the essay, as it evolved over 400 years in this country. At the same time, it would be a running account of the history of the United States, in the hands of these essayists who were contending, directly or indirectly, with the pressing problems of their day. The promise of America was always being weighed against its failure to live up to that standard.

For instance, we have the educator John Dewey arguing for a more democratic schoolhouse, the founder of the settlement house movement Jane Addams analyzing the alienation of young people in big cities, the progressive writer Randolph Bourne describing his own harsh experiences as a disabled person, the feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton advocating for women’s rights, and W. E. B. Dubois and James Weldon Johnson eloquently addressing racial injustice.

Issues of identity, gender and intersectionality were explored by writers such as Richard Rodriguez, Audre Lorde, Leonard Michaels and N. Scott Momaday, sometimes with touches of irony and self-scrutiny, which have always been assets of the essay form.

LH : If a publisher had asked us to compile an anthology of 100 representative American essays, we wouldn’t know where to start. How did you? What were your criteria?

PL : I thought I knew the field fairly well to begin with, having edited the best-selling Art of the Personal Essay in 1994, taught the form for decades, served on book award juries and so on. But once I started researching and collecting material, I discovered that I had lots of gaps, partly because the mandate I had set for myself was so sweeping.

This time I would not restrict myself to personal essays but would include critical essays, impersonal essays, speeches that were in essence essays (such as George Washington’s Farewell Address or Martin Luther King, Jr’s sermon on Vietnam), letters that functioned as essays (Frederick Douglass’s Letter to His Master).

I wanted to expand the notion of what is an essay, to include, for instance, polemics such as Thomas Paine’s Common Sense , or one of the Federalist Papers; newspaper columnists (Fanny Fern, Christopher Morley); humorists (James Thurber, Finley Peter Dunne, Dorothy Parker).

But it also occurred to me that fine essayists must exist in every discipline, not only literature, which sent me on a hunt that took me to cultural criticism (Clement Greenberg, Kenneth Burke), theology (Paul Tillich), food writing (M.F. K. Fisher), geography (John Brinkerhoff Jackson), nature writing (John Muir, John Burroughs, Edward Abbey), science writing (Loren Eiseley, Lewis Thomas), philosophy (George Santayana). My one consistent criterion was that the essay be lively, engaging and intelligently written. In short, I had to like it myself.

Of course I would need to include the best-known practitioners of the American essay—Emerson, Thoreau, Mencken, Baldwin, Sontag, etc.—and was happy to do so. As it turned out, most of the masters of American fiction and poetry also tried their hand successfully at essay-writing, which meant including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, Theodore Dreiser, Willa Cather, Flannery O’Connor, Ralph Ellison. . .

But I was also eager to uncover powerful if almost forgotten voices such as John Jay Chapman, Agnes Repplier, Randolph Bourne, Mary Austin, or buried treasures such as William Dean Howells’ memoir essay of his days working in his father’s printing shop.

Finally, I wanted to show a wide variety of formal approaches, since the essay is by its very nature and nomenclature an experiment, which brought me to Gertrude Stein and Wayne Koestenbaum. Equally important, I was aided in all these searches by colleagues and friends who kept suggesting other names. For every fertile lead, probably four resulted in dead ends. Meanwhile, I was having a real learning adventure.

LH: Do you have a personal favorite among American essayists? If so, what appeals to you the most about them?

PL : I do. It’s Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was the one who cleared the ground for US essayists, in his famous piece, “The American Scholar,” which called on us to free ourselves from slavish imitation of European models and to think for ourselves. So much American thought grows out of Emerson, or is in contention with Emerson, even if that debt is sometimes unacknowledged or unconscious.

What I love about Emerson is his density of thought, and the surprising twists and turns that result from it. I can read an essay of his like “Experience” (the one I included in this anthology) a hundred times and never know where it’s going next. If it was said of Emily Dickenson that her poems made you feel like the top of your head was spinning, that’s what I feel in reading Emerson. He has a playful skepticism, a knack for thinking against himself. Each sentence starts a new rabbit of thought scampering off. He’s difficult but worth the trouble.

I once asked Susan Sontag who her favorite American essayist was, and she replied “Emerson, of course.” It’s no surprise that Nietzsche revered Emerson, as did Carlyle, and in our own time, Harold Bloom, Stanley Cavell, Richard Poirier. But here’s a confession: it took me awhile to come around to him.

I found his preacher’s manner and abstractions initially off-putting, I wasn’t sure about the character of the man who was speaking to me. Then I read his Notebooks and the mystery was cracked: suddenly I was able to follow essays such as “Circles” with pure pleasure, seeing as I could the darkness and complexity underneath the optimism.

LH: You make the interesting decision to open the anthology with an essay written in 1726, 50 years before the founding of the republic. Why?

PL : I wanted to start the anthology with the first fully-formed essayistic voices in this land, which turned out to belong to the Puritans. Regardless of the negative associations of zealous prudishness that have come to attach to the adjective “puritanical,” those American colonies founded as religious settlements were spearheaded by some remarkably learned and articulate spokespersons, whose robust prose enriched the American literary canon.

Cotton Mather and Jonathan Edwards were highly cultivated readers, familiar with the traditions of essay-writing, Montaigne and the English, and with the latest science, even as they inveighed against witchcraft. I will admit that it also amused me to open the book with Cotton Mather, a prescriptive, strait-is-the-gate character, and end it with Zadie Smith, who is not only bi-racial but bi-national, dividing her year between London and New York, and whose openness to self-doubt is signaled by her essay collection title, Changing My Mind .

The next group of writers I focused on were the Founding Fathers, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, and a foundational feminist, Judith Sargent Murray, who wrote the 1790 essay “On the Equality of the Sexes.” These authors, whose essays preceded, occurred during or immediately followed the founding of the republic, were in some ways the opposite of the Puritans, being for the most part Deists or secular followers of the Enlightenment.

Their attraction to reasoned argument and willingness to entertain possible objections to their points of view inspired a vigorous strand of American essay-writing. So, while we may fix the founding of the United States to a specific year, the actual culture and literature of the country book-ended that date.

LH: You end with Zadie Smith’s “Speaking in Tongues,” published in 2008. Which essay in the last 12 years would be your 101st selection?

PL : Funny you should ask. As it happens, I am currently putting the finishing touches on another anthology, this one entirely devoted to the Contemporary (i.e., 21st century) American Essay. I have been immersed in reading younger, up-and-coming writers, established mid-career writers, and some oldsters who are still going strong (Janet Malcolm, Vivian Gornick, Barry Lopez, John McPhee, for example).

It would be impossible for me to single out any one contemporary essayist, as they are all in different ways contributing to the stew, but just to name some I’ve been tracking recently: Meghan Daum, Maggie Nelson, Sloane Crosley, Eula Biss, Charles D’Ambrosio, Teju Cole, Lia Purpura, John D’Agata, Samantha Irby, Anne Carson, Alexander Chee, Aleksander Hemon, Hilton Als, Mary Cappello, Bernard Cooper, Leslie Jamison, Laura Kipnis, Rivka Galchen, Emily Fox Gordon, Darryl Pinckney, Yiyun Li, David Lazar, Lynn Freed, Ander Monson, David Shields, Rebecca Solnit, John Jeremiah Sullivan, Eileen Myles, Amy Tan, Jonathan Lethem, Chelsea Hodson, Ross Gay, Jia Tolentino, Jenny Boully, Durga Chew-Bose, Brian Blanchfield, Thomas Beller, Terry Castle, Wesley Yang, Floyd Skloot, David Sedaris. . .

Such a banquet of names speaks to the intergenerational appeal of the form. We’re going through a particularly rich time for American essays: especially compared to, 20 years ago, when editors wouldn’t even dare put the word “essays” on the cover, but kept trying to package these variegated assortments as single-theme discourses, we’ve seen many collections that have been commercially successful and attracted considerable critical attention.

It has something to do with the current moment, which has everyone more than a little confused and therefore trusting more than ever those strong individual voices that are willing to cop to their subjective fears, anxieties, doubts and ecstasies.

__________________________________

The Glorious American Essay , edited by Phillip Lopate, is available now.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Phillip Lopate

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Recent History: Lessons From Obama, Both Cautionary and Hopeful

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- TEFL Internship

- TEFL Masters

- Find a TEFL Course

- Special Offers

- Course Providers

- Teach English Abroad

- Find a TEFL Job

- About DoTEFL

- Our Mission

- How DoTEFL Works

Forgotten Password

- How To Write an Essay in English: 11 Tips To Write a Great Essay

- Learn English

- James Prior

- No Comments

- Updated February 23, 2024

Writing essays in English can be challenging even for native speakers, and they can be even more difficult if you’re learning English. Fortunately, there are various steps that you can take to make the essay writing process easier. In this guide, we delve into the intricacies of essay writing, providing a step-by-step approach on how to write an essay in English to help you craft more compelling and impactful essays.

So, if you want to know how to be good at writing essays in English, read on!

Important Essay Writing Considerations

Before we begin, it’s important to note that there are different types of essays in English. You could find yourself writing an academic essay, a college essay, an argumentative essay, a narrative essay, an expository essay, or an application essay, among others.

How you write an essay will depend upon the type of essay, its purpose, the subject matter, and the given topic. You therefore need to consider the goal of the essay and make sure you understand the assignment. If you’re unsure about this, seek clarification from your teacher, professor, or person who will be receiving the essay before you start writing. That way you can ensure that you are starting correctly and don’t end up submitting something that doesn’t match the initial brief.

Once you’re feeling confident about this, it’s time to get writing!

How To Write an Essay

Whether you’re a student navigating academia or a professional honing your communication skills, the ability to express your thoughts coherently in English is invaluable. And, while writing can often be a challenge, it forms a key part of communication and often comes in the form of essays.

Here we’ll run you through the steps you need to follow to write essays you can be proud of.

1. Understand the Prompt: The Foundation of Your Essay

At the core of every essay lies the prompt – an instruction that shapes and defines your writing. Before ink meets paper or fingers touch keys, it is paramount to analyze the prompt and make sure you understand it. This foundational understanding forms the bedrock upon which your entire essay will be built, so it’s vital that you uncover any requirements.

To truly grasp the essence of the prompt, consider the key terms or phrases. Identify the central essay question, discern any specific instructions, and take note of the intended scope.

For example, if the prompt requires an analysis, understand the depth of analysis expected. If you’re expected to write a narrative essay, what is it about?

You then need to consider the length of your essay. It could be that you need to write a five-paragraph essay, or you may be expected to write two pages.

The better your understanding of the prompt, the more effectively you can tailor your response. If you don’t understand the prompt and are unable to clarify it with someone, you can always seek out help from your teacher to get some valuable feedback.

Once you’ve established the exact requirements it’s time to start your preparation for the writing process. The first stage of this is to come up with a thesis statement and plan your essay.

2. Craft a Compelling Thesis Statement

With a clear understanding of the prompt, for most essays, the next step is to determine your thesis statement. This is a sentence or two that encapsulates the core of your argument, providing both you and your readers with a roadmap. A well-crafted thesis serves as your guide, ensuring a focused, purposeful essay.

The thesis statement should not merely summarize your main points on the essay topic but also articulate a specific stance or perspective. It acts as a beacon, signaling to your readers the central theme and direction of your essay. Think of it as a compass that navigates your audience through the topic you’re about to explore.

Having a strong thesis statement will be particularly important for an argumentative essay if you want to write a good essay.

However, just be aware that if you’re writing an essay from a narrative writing prompt , a thesis statement may not be as applicable. In this case, you may be better off with a good introductory paragraph that introduces what you’re going to write about. We’ll cover this shortly.

3. Build a Solid Outline

Organization is the glue that binds your ideas and essays together. Before you start writing, you should therefore create an outline for your essay. This acts as a basic structure for your essay and can include your thesis or introduction, plus the core ideas or topics that you want to cover in your essay. It can also help you establish your paragraph order so that you have a good idea of how your essay will flow before you’ve even written it.

Begin by identifying the key sections: introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Break down the body into specific points or arguments, each supported by evidence or examples. This detailed structure helps maintain focus and prevents your essay from meandering into unrelated tangents and forms the initial basis of a well-written essay.

Your outline should act as the blueprint for your essay, offering a structured framework for the thoughts and arguments that will follow. This step not only aids in organizing your ideas but also ensures a logical and coherent progression throughout your essay.

4. Write a Captivating Introduction: The Hook that Ignites Interest

The introduction is your essay’s first impression, and you chance to capture your reader’s attention. Therefore, your introduction paragraph should be strong and make the reader want to learn more.

A great idea is to start with a hook. This can be a compelling anecdote, a thought-provoking question, or a striking statistic. This initial engagement sets the tone for the entire essay, inviting readers to delve further into your exploration.

Consider the introduction as a narrative in itself. It should not only introduce the topic or thesis but also create anticipation. You can use vivid language and imagery to transport your reader into the world of your essay.

By the end of the introduction, your reader should be eager to explore the arguments you’re about to put forward or read the story you’re about to tell.

5. Provide Clear Topic Sentences: Navigating the Reader Through Your Essay

Each paragraph in your essay should have a purpose, and this purpose should be encapsulated in a clear and concise topic sentence. These sentences act as signposts, guiding readers through the various facets of your argument.

Once you get into the body paragraphs, consider the topic sentence as the main idea of each paragraph. It should encapsulate the essence of the paragraph and relate directly to your thesis or the story you are telling. This approach not only facilitates a smooth flow of ideas but also ensures that each paragraph contributes meaningfully to the overarching argument.

Clarity in topic sentences enhances the overall coherence of your essay, making it easier for readers to follow and understand your narrative or arguments.

6. Support Your Arguments with Evidence: Building a Credible Case

Arguments, no matter how compelling, are strengthened by supporting evidence. When you’re writing an essay, back up your claims with relevant and credible evidence. This can take the form of quotations from authoritative sources, statistical data, or real-world examples. A well-supported argument not only validates your perspective but also demonstrates a thorough understanding of the subject matter.

When you incorporate or present evidence, consider the credibility of your sources. Peer-reviewed journals, expert opinions, and empirical data enhance the authenticity of your arguments. They can also showcase the depth of your research.

If you’re writing an academic essay, be meticulous in your citations, and adhere to the conventions of the chosen citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

7. Maintain Consistent Style and Tone

The mastery of writing an essay extends beyond individual sentences. You should aim for a consistent tone and style throughout your essay. This not only ensures a cohesive reading experience but also reflects a good understanding of the subject matter.

Consistency in style encompasses aspects such as sentence structure, vocabulary choice, and the use of rhetorical devices. These elements collectively contribute to the overall fluency and coherence of your essay.

You should also consider the tone of your writing. Whether formal, informal, persuasive, or analytical, the tone should align with the purpose and audience of your essay.

For example, if you’re doing a piece of narrative writing the tone is likely to be very different to that of an argumentative essay. Different writing styles can be applied to different essay types and this should be reflected in your writing process.

8. Revise and Edit

Once you’ve completed the first draft of your essay it’s time to revise and edit it. The first draft is the raw material of your essay, a foundation to be refined. Take the time to review it with a focus on clarity. Trim unnecessary words, refine overly long sentences, and ensure that each paragraph contributes seamlessly to the overall narrative. This process can transform your prose into a polished and articulate piece of writing and is a key part of writing an essay.

If you have time, it helps to approach the revision process with fresh eyes. Come back to your essay after having a break from writing and consider each sentence’s clarity, coherence, and relevance to the thesis.

Structural elements, such as paragraph transitions and the logical flow of ideas, are equally crucial. While focusing on clarity, also consider the engagement factor – does your writing captivate and maintain the reader’s interest?

The revision process is an opportunity to elevate your writing from functional to exceptional and turn a good essay into a great essay.

9. Check Grammar and Punctuation: The Finishing Touches

Even the most brilliant essays can be overshadowed by grammatical errors and punctuation mistakes. Before marking your essay complete, conduct a thorough review. Ensure that your grammar is impeccable, and your punctuation is spot-on.

You can use spell-check tools and grammar checkers like grammarchecker.com to check this but don’t rely on them entirely. After all, you won’t have them if you’re writing an essay in an exam!

Furthermore, manual proofreading can be essential to catch errors that automated tools might overlook. Pay attention to common pitfalls such as verb tense consistency and the appropriate use of punctuation marks. It’s easy to make mistakes with commas, semicolons , and colons if you’re not careful. And, if you’re unsure about something either don’t use it or look up how to use it.

This meticulous attention to detail adds a professional touch to your essay. A well-polished essay not only enhances your credibility as a writer but also makes your work more enjoyable to read. If you want to show off your writing skills and be rewarded for it, it’s important to spot and correct any common mistakes before submitting your essay.

10. Seek Peer Feedback: A Fresh Perspective

Before finalizing your essay, it can be helpful to seek feedback from peers or mentors. A fresh perspective can uncover blind spots, identify areas for improvement, and provide insights that enhance the overall quality of your essay.

When seeking feedback, be specific about the aspects you’d like your peers to focus on. Are you looking for input on the clarity of your thesis, the effectiveness of your evidence, or the overall structure of your essay? Constructive criticism is a valuable tool for refinement, helping you view your work through different lenses and identify opportunities for enhancement.

11. Conclude Strongly: Leaving a Lasting Impression

The conclusion paragraph is your final opportunity to leave a lasting impression. So, knowing how to write a conclusion is an important skill. It presents the chance to summarize your main points, restate your thesis, and leave your readers with something to ponder.

While summarizing your main points, avoid introducing new ideas. Instead, emphasize the significance of your argument in the broader context. A strong conclusion not only ties up the loose ends of your essay but also resonates with your audience, prompting further reflection on your arguments or points. Ideally, you want to leave a lasting imprint on your readers, inviting them to think about your essay beyond its final words.

And remember, there are many different ways to say in conclusion . So, don’t be afraid to mix it up, especially if you are writing more than one essay.

Conclusion: Write an Essay

Essay writing is a key skill and one that is worth mastering whether you’re a native speaker or if you’re trying to become more fluent in English .

By incorporating these eleven tips into your essay writing process, and with practice and a commitment to continual improvement, you can elevate your English essays from standard to exceptional.

So, armed with this guide, unleash the power of your words, start writing, and transform your essays into compelling narratives that captivate and resonate with your audience. I hope you’ll write an essay to be proud of!

- Recent Posts

- How to Write a TOEFL Essay - April 22, 2024

- What Can You Do with a TEFL Certificate? - April 5, 2024

- 19 Best Learning Management System Examples for 2024 - April 4, 2024

More from DoTEFL

17 of The Longest English Words: Can You Pronounce Them?!

- Updated January 29, 2024

Linking Words & Connector Words: Ultimate List With Examples

How Many Weeks Are in Summer & How Long is Summer Break?

- Updated November 1, 2023

What is Fluency in English & Can You Teach it?

- Updated January 12, 2024

What Does TEFL Stand For? TEFL Acronyms and Terms

- Updated January 9, 2023

15 Best Language Learning Apps for 2024

- Updated January 28, 2024

- The global TEFL course directory.

How to Write a Good English Literature Essay

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

How do you write a good English Literature essay? Although to an extent this depends on the particular subject you’re writing about, and on the nature of the question your essay is attempting to answer, there are a few general guidelines for how to write a convincing essay – just as there are a few guidelines for writing well in any field.

We at Interesting Literature call them ‘guidelines’ because we hesitate to use the word ‘rules’, which seems too programmatic. And as the writing habits of successful authors demonstrate, there is no one way to become a good writer – of essays, novels, poems, or whatever it is you’re setting out to write. The French writer Colette liked to begin her writing day by picking the fleas off her cat.

Edith Sitwell, by all accounts, liked to lie in an open coffin before she began her day’s writing. Friedrich von Schiller kept rotten apples in his desk, claiming he needed the scent of their decay to help him write. (For most student essay-writers, such an aroma is probably allowed to arise in the writing-room more organically, over time.)

We will address our suggestions for successful essay-writing to the average student of English Literature, whether at university or school level. There are many ways to approach the task of essay-writing, and these are just a few pointers for how to write a better English essay – and some of these pointers may also work for other disciplines and subjects, too.

Of course, these guidelines are designed to be of interest to the non-essay-writer too – people who have an interest in the craft of writing in general. If this describes you, we hope you enjoy the list as well. Remember, though, everyone can find writing difficult: as Thomas Mann memorably put it, ‘A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.’ Nora Ephron was briefer: ‘I think the hardest thing about writing is writing.’ So, the guidelines for successful essay-writing:

1. Planning is important, but don’t spend too long perfecting a structure that might end up changing.

This may seem like odd advice to kick off with, but the truth is that different approaches work for different students and essayists. You need to find out which method works best for you.

It’s not a bad idea, regardless of whether you’re a big planner or not, to sketch out perhaps a few points on a sheet of paper before you start, but don’t be surprised if you end up moving away from it slightly – or considerably – when you start to write.

Often the most extensively planned essays are the most mechanistic and dull in execution, precisely because the writer has drawn up a plan and refused to deviate from it. What is a more valuable skill is to be able to sense when your argument may be starting to go off-topic, or your point is getting out of hand, as you write . (For help on this, see point 5 below.)

We might even say that when it comes to knowing how to write a good English Literature essay, practising is more important than planning.

2. Make room for close analysis of the text, or texts.

Whilst it’s true that some first-class or A-grade essays will be impressive without containing any close reading as such, most of the highest-scoring and most sophisticated essays tend to zoom in on the text and examine its language and imagery closely in the course of the argument. (Close reading of literary texts arises from theology and the analysis of holy scripture, but really became a ‘thing’ in literary criticism in the early twentieth century, when T. S. Eliot, F. R. Leavis, William Empson, and other influential essayists started to subject the poem or novel to close scrutiny.)

Close reading has two distinct advantages: it increases the specificity of your argument (so you can’t be so easily accused of generalising a point), and it improves your chances of pointing up something about the text which none of the other essays your marker is reading will have said. For instance, take In Memoriam (1850), which is a long Victorian poem by the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson about his grief following the death of his close friend, Arthur Hallam, in the early 1830s.

When answering a question about the representation of religious faith in Tennyson’s poem In Memoriam (1850), how might you write a particularly brilliant essay about this theme? Anyone can make a general point about the poet’s crisis of faith; but to look closely at the language used gives you the chance to show how the poet portrays this.

For instance, consider this stanza, which conveys the poet’s doubt:

A solid and perfectly competent essay might cite this stanza in support of the claim that Tennyson is finding it increasingly difficult to have faith in God (following the untimely and senseless death of his friend, Arthur Hallam). But there are several ways of then doing something more with it. For instance, you might get close to the poem’s imagery, and show how Tennyson conveys this idea, through the image of the ‘altar-stairs’ associated with religious worship and the idea of the stairs leading ‘thro’ darkness’ towards God.

In other words, Tennyson sees faith as a matter of groping through the darkness, trusting in God without having evidence that he is there. If you like, it’s a matter of ‘blind faith’. That would be a good reading. Now, here’s how to make a good English essay on this subject even better: one might look at how the word ‘falter’ – which encapsulates Tennyson’s stumbling faith – disperses into ‘falling’ and ‘altar’ in the succeeding lines. The word ‘falter’, we might say, itself falters or falls apart.

That is doing more than just interpreting the words: it’s being a highly careful reader of the poetry and showing how attentive to the language of the poetry you can be – all the while answering the question, about how the poem portrays the idea of faith. So, read and then reread the text you’re writing about – and be sensitive to such nuances of language and style.

The best way to become attuned to such nuances is revealed in point 5. We might summarise this point as follows: when it comes to knowing how to write a persuasive English Literature essay, it’s one thing to have a broad and overarching argument, but don’t be afraid to use the microscope as well as the telescope.

3. Provide several pieces of evidence where possible.

Many essays have a point to make and make it, tacking on a single piece of evidence from the text (or from beyond the text, e.g. a critical, historical, or biographical source) in the hope that this will be enough to make the point convincing.

‘State, quote, explain’ is the Holy Trinity of the Paragraph for many. What’s wrong with it? For one thing, this approach is too formulaic and basic for many arguments. Is one quotation enough to support a point? It’s often a matter of degree, and although one piece of evidence is better than none, two or three pieces will be even more persuasive.

After all, in a court of law a single eyewitness account won’t be enough to convict the accused of the crime, and even a confession from the accused would carry more weight if it comes supported by other, objective evidence (e.g. DNA, fingerprints, and so on).

Let’s go back to the example about Tennyson’s faith in his poem In Memoriam mentioned above. Perhaps you don’t find the end of the poem convincing – when the poet claims to have rediscovered his Christian faith and to have overcome his grief at the loss of his friend.

You can find examples from the end of the poem to suggest your reading of the poet’s insincerity may have validity, but looking at sources beyond the poem – e.g. a good edition of the text, which will contain biographical and critical information – may help you to find a clinching piece of evidence to support your reading.

And, sure enough, Tennyson is reported to have said of In Memoriam : ‘It’s too hopeful, this poem, more than I am myself.’ And there we have it: much more convincing than simply positing your reading of the poem with a few ambiguous quotations from the poem itself.

Of course, this rule also works in reverse: if you want to argue, for instance, that T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is overwhelmingly inspired by the poet’s unhappy marriage to his first wife, then using a decent biographical source makes sense – but if you didn’t show evidence for this idea from the poem itself (see point 2), all you’ve got is a vague, general link between the poet’s life and his work.

Show how the poet’s marriage is reflected in the work, e.g. through men and women’s relationships throughout the poem being shown as empty, soulless, and unhappy. In other words, when setting out to write a good English essay about any text, don’t be afraid to pile on the evidence – though be sensible, a handful of quotations or examples should be more than enough to make your point convincing.

4. Avoid tentative or speculative phrasing.

Many essays tend to suffer from the above problem of a lack of evidence, so the point fails to convince. This has a knock-on effect: often the student making the point doesn’t sound especially convinced by it either. This leaks out in the telling use of, and reliance on, certain uncertain phrases: ‘Tennyson might have’ or ‘perhaps Harper Lee wrote this to portray’ or ‘it can be argued that’.

An English university professor used to write in the margins of an essay which used this last phrase, ‘What can’t be argued?’

This is a fair criticism: anything can be argued (badly), but it depends on what evidence you can bring to bear on it (point 3) as to whether it will be a persuasive argument. (Arguing that the plays of Shakespeare were written by a Martian who came down to Earth and ingratiated himself with the world of Elizabethan theatre is a theory that can be argued, though few would take it seriously. We wish we could say ‘none’, but that’s a story for another day.)

Many essay-writers, because they’re aware that texts are often open-ended and invite multiple interpretations (as almost all great works of literature invariably do), think that writing ‘it can be argued’ acknowledges the text’s rich layering of meaning and is therefore valid.

Whilst this is certainly a fact – texts are open-ended and can be read in wildly different ways – the phrase ‘it can be argued’ is best used sparingly if at all. It should be taken as true that your interpretation is, at bottom, probably unprovable. What would it mean to ‘prove’ a reading as correct, anyway? Because you found evidence that the author intended the same thing as you’ve argued of their text? Tennyson wrote in a letter, ‘I wrote In Memoriam because…’?

But the author might have lied about it (e.g. in an attempt to dissuade people from looking too much into their private life), or they might have changed their mind (to go back to the example of The Waste Land : T. S. Eliot championed the idea of poetic impersonality in an essay of 1919, but years later he described The Waste Land as ‘only the relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life’ – hardly impersonal, then).

Texts – and their writers – can often be contradictory, or cagey about their meaning. But we as critics have to act responsibly when writing about literary texts in any good English essay or exam answer. We need to argue honestly, and sincerely – and not use what Wikipedia calls ‘weasel words’ or hedging expressions.

So, if nothing is utterly provable, all that remains is to make the strongest possible case you can with the evidence available. You do this, not only through marshalling the evidence in an effective way, but by writing in a confident voice when making your case. Fundamentally, ‘There is evidence to suggest that’ says more or less the same thing as ‘It can be argued’, but it foregrounds the evidence rather than the argument, so is preferable as a phrase.

This point might be summarised by saying: the best way to write a good English Literature essay is to be honest about the reading you’re putting forward, so you can be confident in your interpretation and use clear, bold language. (‘Bold’ is good, but don’t get too cocky, of course…)

5. Read the work of other critics.

This might be viewed as the Holy Grail of good essay-writing tips, since it is perhaps the single most effective way to improve your own writing. Even if you’re writing an essay as part of school coursework rather than a university degree, and don’t need to research other critics for your essay, it’s worth finding a good writer of literary criticism and reading their work. Why is this worth doing?

Published criticism has at least one thing in its favour, at least if it’s published by an academic press or has appeared in an academic journal, and that is that it’s most probably been peer-reviewed, meaning that other academics have read it, closely studied its argument, checked it for errors or inaccuracies, and helped to ensure that it is expressed in a fluent, clear, and effective way.

If you’re serious about finding out how to write a better English essay, then you need to study how successful writers in the genre do it. And essay-writing is a genre, the same as novel-writing or poetry. But why will reading criticism help you? Because the critics you read can show you how to do all of the above: how to present a close reading of a poem, how to advance an argument that is not speculative or tentative yet not over-confident, how to use evidence from the text to make your argument more persuasive.

And, the more you read of other critics – a page a night, say, over a few months – the better you’ll get. It’s like textual osmosis: a little bit of their style will rub off on you, and every writer learns by the examples of other writers.

As T. S. Eliot himself said, ‘The poem which is absolutely original is absolutely bad.’ Don’t get precious about your own distinctive writing style and become afraid you’ll lose it. You can’t gain a truly original style before you’ve looked at other people’s and worked out what you like and what you can ‘steal’ for your own ends.

We say ‘steal’, but this is not the same as saying that plagiarism is okay, of course. But consider this example. You read an accessible book on Shakespeare’s language and the author makes a point about rhymes in Shakespeare. When you’re working on your essay on the poetry of Christina Rossetti, you notice a similar use of rhyme, and remember the point made by the Shakespeare critic.

This is not plagiarising a point but applying it independently to another writer. It shows independent interpretive skills and an ability to understand and apply what you have read. This is another of the advantages of reading critics, so this would be our final piece of advice for learning how to write a good English essay: find a critic whose style you like, and study their craft.

If you’re looking for suggestions, we can recommend a few favourites: Christopher Ricks, whose The Force of Poetry is a tour de force; Jonathan Bate, whose The Genius of Shakespeare , although written for a general rather than academic audience, is written by a leading Shakespeare scholar and academic; and Helen Gardner, whose The Art of T. S. Eliot , whilst dated (it came out in 1949), is a wonderfully lucid and articulate analysis of Eliot’s poetry.

James Wood’s How Fiction Works is also a fine example of lucid prose and how to close-read literary texts. Doubtless readers of Interesting Literature will have their own favourites to suggest in the comments, so do check those out, as these are just three personal favourites. What’s your favourite work of literary scholarship/criticism? Suggestions please.

Much of all this may strike you as common sense, but even the most commonsensical advice can go out of your mind when you have a piece of coursework to write, or an exam to revise for. We hope these suggestions help to remind you of some of the key tenets of good essay-writing practice – though remember, these aren’t so much commandments as recommendations. No one can ‘tell’ you how to write a good English Literature essay as such.

But it can be learned. And remember, be interesting – find the things in the poems or plays or novels which really ignite your enthusiasm. As John Mortimer said, ‘The only rule I have found to have any validity in writing is not to bore yourself.’

Finally, good luck – and happy writing!

And if you enjoyed these tips for how to write a persuasive English essay, check out our advice for how to remember things for exams and our tips for becoming a better close reader of poetry .

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

30 thoughts on “How to Write a Good English Literature Essay”

You must have taken AP Literature. I’m always saying these same points to my students.

I also think a crucial part of excellent essay writing that too many students do not realize is that not every point or interpretation needs to be addressed. When offered the chance to write your interpretation of a work of literature, it is important to note that there of course are many but your essay should choose one and focus evidence on this one view rather than attempting to include all views and evidence to back up each view.

Reblogged this on SocioTech'nowledge .

Not a bad effort…not at all! (Did you intend “subject” instead of “object” in numbered paragraph two, line seven?”

Oops! I did indeed – many thanks for spotting. Duly corrected ;)

That’s what comes of writing about philosophy and the subject/object for another post at the same time!

Reblogged this on Scribing English .

- Pingback: Recommended Resource: Interesting Literature.com & how to write an essay | Write Out Loud

Great post on essay writing! I’ve shared a post about this and about the blog site in general which you can look at here: http://writeoutloudblog.com/2015/01/13/recommended-resource-interesting-literature-com-how-to-write-an-essay/

All of these are very good points – especially I like 2 and 5. I’d like to read the essay on the Martian who wrote Shakespeare’s plays).

Reblogged this on Uniqely Mustered and commented: Dedicate this to all upcoming writers and lovers of Writing!

I shall take this as my New Year boost in Writing Essays. Please try to visit often for corrections,advise and criticisms.

Reblogged this on Blue Banana Bread .

Reblogged this on worldsinthenet .

All very good points, but numbers 2 and 4 are especially interesting.

- Pingback: Weekly Digest | Alpha Female, Mainstream Cat

Reblogged this on rainniewu .

Reblogged this on pixcdrinks .

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay? Interesting Literature | EngLL.Com

Great post. Interesting infographic how to write an argumentative essay http://www.essay-profy.com/blog/how-to-write-an-essay-writing-an-argumentative-essay/

Reblogged this on DISTINCT CHARACTER and commented: Good Tips

Reblogged this on quirkywritingcorner and commented: This could be applied to novel or short story writing as well.

Reblogged this on rosetech67 and commented: Useful, albeit maybe a bit late for me :-)

- Pingback: How to Write a Good English Essay | georg28ang

such a nice pieace of content you shared in this write up about “How to Write a Good English Essay” going to share on another useful resource that is

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: How to Remember Things for Exams | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Michael Moorcock: How to Write a Novel in 3 Days | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Shakespeare and the Essay | Interesting Literature

A well rounded summary on all steps to keep in mind while starting on writing. There are many new avenues available though. Benefit from the writing options of the 21st century from here, i loved it! http://authenticwritingservices.com

- Pingback: Mark Twain’s Rules for Good Writing | Peacejusticelove's Blog

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Literatures

- Asian Literatures

- British and Irish Literatures

- Latin American and Caribbean Literatures

- North American Literatures

- Oceanic Literatures

- Slavic and Eastern European Literatures

- West Asian Literatures, including Middle East

- Western European Literatures

- Ancient Literatures (before 500)

- Middle Ages and Renaissance (500-1600)

- Enlightenment and Early Modern (1600-1800)

- 19th Century (1800-1900)

- 20th and 21st Century (1900-present)

- Children’s Literature

- Cultural Studies

- Film, TV, and Media

- Literary Theory

- Non-Fiction and Life Writing

- Print Culture and Digital Humanities

- Theater and Drama

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The american essay.

- Jenny Spinner Jenny Spinner The Writing Center, St. Joseph's University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.545

- Published online: 26 September 2017

- This version: 20 April 2022

- Previous version

America’s earliest essayists largely imitated their European counterparts. The writers abroad they most admired—periodical essayists like Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in the 18th century and familiar essayists like Charles Lamb and Leigh Hunt in the 19th century—heavily influenced the essays they penned at home. Yet amid these imitations are glimmers of voices and experiences unique to America. Benjamin Franklin’s clear and direct prose style, combined with his down-to-earth diction, make him one of the best and most readable of the early American periodical essayists. In the first half of the 19th century, American essayists found reception for their work in the country’s many new magazines and quarterlies founded in the wake of the Revolutionary War. Among these writers, Washington Irving is often named as America’s first true essayist. Other influential essayists of this period include humor essayists like Mark Twain, who published social and political lampoons of American life. Ralph Waldo Emerson and Margaret Fuller, leaders of the American Transcendentalist movement, were influential thinkers and prolific writers as well. Emerson’s disciple, Henry David Thoreau, is a pioneer of the nature essay, which numerous writers since have used to explore America’s vast and varied landscape. Nineteenth-century America also provided women with increased opportunities to publish essays, and many, like Fanny Fern, achieved substantial commercial successes as newspaper essayists. Gertrude Bustill Mossell, the highest paid African American newspaperwoman at the time, was one of the first African American women to write a newspaper column. Political essayists like Maria W. Miller Stewart, Frederick Douglass, Anna Julia Cooper, and W. E. B. DuBois, wrote on two of the most relevant issues of the day: slavery and women’s rights. Ann Plato became the first African American to publish a collection of essays with her 1820 book. By the turn of the 20th century, the genteel essay—marked by its yearning for a romanticized past and typically European, rather than American, in flavor—dominated the American essay scene. Agnes Repplier and Katharine Fullerton Gerould were prominent writers in the Genteel Tradition, along with Charles S. Brooks, Samuel McChord Crothers, and Donald Grant Mitchell (Ik Marvel). The 1920s and 1930s marked the heyday of the newspaper essay columnist and the decline of the genteel essay. One such columnist, H. L. Mencken, railing against the “booboise,” was one of the most influential voices of his time. The 1925 founding of The New Yorker magazine heralded a new moment for the American essay. The New Yorker provided an important outlet for the nation’s essayists, including E. B. White, whose influence on the personal essayists following in his footsteps ever since is hard to measure. Joan Didion’s work in the field of New Journalism, along with Norman Mailer, opened additional possibilities for the essay writer, adding techniques from both fiction and journalism to the essayist’s craft belt. Over two decades into the 21st century, American essayists continue to crack the form even wider, pushing against genre boundaries as well as using the essay to document the full range of American, and human, experiences.

Updated in this version

Enhanced discussion, updated references, images added

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Literature. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 26 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.136]

- 81.177.182.136

Character limit 500 /500

Classic British and American Essays and Speeches

English Prose From Jack London to Dorothy Parker

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

From the works and musings of Walt Witman to those of Virginia Woolf, some of the cultural heroes and prolific artists of prose are listed below--along with some of the world's greatest essays and speeches ever composed by these British and American literary treasures.

George Ade (1866-1944)

George Ade was an America playwright, newspaper columnist and humorist whose greatest recognition was "Fables in Slang" (1899), a satire that explored the colloquial vernacular of America. Ade eventually succeeded in doing what he set out to do: Make America laugh.

- The Difference Between Learning and Learning How : "In due time the Faculty gave the Degree of M.A. to what was left of Otis and still his Ambition was not satisfied."

- Luxuries: "About sixty-five per cent of all the people in the world think they are getting along great when they are not starving to death."

- Vacations: "The planet you are now visiting may be the only one you ever see."

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906)

American activist Susan B. Anthony crusaded for the women's suffrage movement, making way for the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution in 1920, giving women the right to vote. Anthony is principally known for the six-volume "History of Woman Suffrage."

- On Women's Right to Vote : "The only question left to be settled now is: Are women persons?"

Robert Benchley (1889-1945)

The writings of American humorist, actor and drama critic Robert Benchley are considered his best achievement. His socially awkward, slightly confused persona allowed him to write about the inanity of the world to great effect.

- Advice to Writers : "A terrible plague of insufferably artificial and affected authors"

- Business Letters : "As it stands now things are pretty black for the boy."

- Christmas Afternoon : "Done in the Manner, If Not in the Spirit of Dickens"

- Do Insects Think? : "It really was more like a child of our own than a wasp, except that it looked more like a wasp than a child of our own."

- The Most Popular Book of the Month: "In practice, the book is not flawless. There are five hundred thousand names, each with a corresponding telephone number."

Joseph Conrad (1857-1924)

British novelist and short-story writer Joseph Conrad rendered about the "tragedy of loneliness" at sea and became known for his colorful, rich descriptions about the sea and other exotic places. He is regarded as one of the greatest English novelists of all time.

- Outside Literature : "A sea voyage would have done him good. But it was I who went to sea--this time bound to Calcutta."

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895)

American Frederick Douglass' great oratory and literary skills helped him to become the first African American citizen to hold high office in the US government. He was one of the 19th century's most prominent human rights activist, and his autobiography, "Life and Times of Frederick Douglass" (1882), became an American literary classic.

- The Destiny of Colored Americans : "Slavery is the peculiar weakness of America, as well as its peculiar crime."

- A Glorious Resurrection: "My long-crushed spirit rose."

W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963)

W.E.B. Du Bois was an American scholar and human rights activist, a respected author and historian of literature. His literature and studies analyzed the unreachable depths of American racism. Du Bois' seminal work is a collection of 14 essays titled "The Souls of Black Folk" (1903).

- Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others : "Mr. Washington represents in Negro thought the old attitude of adjustment and submission."

- Of the Passing of the First-Born : "He knew no color-line, poor dear--and the Veil, though it shadowed him, had not yet darkened half his sun."

F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940)

Known foremost for his novel "The Great Gatsby," American novelist and short-story writer F. Scott Fitzgerald was also a renown playboy and had a tumultuous life compounded by alcoholism and depression. Only after his death did he become known as a preeminent American literary author.

- What I Think and Feel at 25: "The main thing is to be your own kind of a darn fool."

Ben Hecht (1894-1964)

American novelist, short-story writer and playwright Ben Hecht is remembered as one of Hollywood's greatest screenplay writers and may best be remembered for "Scarface," Wuthering Heights" and "Guys and Dolls."