- Conjunctions

- Prepositions

DISSERTATION in a Sentence Examples: 21 Ways to Use Dissertation

A dissertation is a formal academic document presenting research and findings on a specific subject. Typically required for completion of a doctoral degree, a dissertation showcases original research and analysis conducted by the author.

This comprehensive document serves as a written representation of the author’s scholarly work and demonstrates their expertise in a particular field of study. Often ranging from 100 to over 300 pages, a dissertation requires meticulous research, critical thinking, and writing skills to produce a well-supported argument or study.

Table of Contents

7 Examples Of Dissertation Used In a Sentence For Kids

- Dissertation is a big project for students to show what they learned.

- I need to do a dissertation about animals for school.

- My sister is writing a dissertation about plants in her college.

- Dissertation is a long paper that needs lots of research.

- I will make a dissertation on colors and share it with my classmates.

- My friend’s dissertation is about space and planets.

- When I grow up, I want to write a dissertation like my mom.

14 Sentences with Dissertation Examples

- Dissertation submission deadline is approaching, make sure to proofread your work before final submission.

- It is essential to seek guidance from professors while choosing a topic for your dissertation .

- Library resources are crucial for conducting research for your dissertation .

- Forming a study group can help you stay motivated during the dissertation writing process.

- Use academic databases to find relevant literature for your dissertation .

- Time management is key when working on your dissertation alongside other academic commitments.

- Seek feedback from peers on your dissertation draft to improve the quality of your work.

- Creating an outline can help you structure your dissertation effectively.

- Make sure to cite all sources properly to avoid plagiarism in your dissertation .

- Attending workshops on research methodologies can improve your skills for dissertation writing.

- Collaborating with industry professionals can add valuable insights to your dissertation .

- Use software tools like EndNote for easier referencing in your dissertation .

- Take breaks during your dissertation writing process to prevent burnout.

- Presenting your dissertation findings at conferences can enhance your academic profile.

How To Use Dissertation in Sentences?

Dissertation is a formal academic document that presents research findings and conclusions on a particular topic. It is usually written by students pursuing a higher degree, such as a master’s or doctorate.

To use dissertation in a sentence, first, identify the main topic or idea you want to convey. For example, “Carla’s dissertation explores the impact of climate change on coral reefs.” In this sentence, the word “dissertation” is used to indicate that Carla has conducted research on a specific subject.

Make sure to place the word dissertation appropriately within the sentence to ensure clarity and coherence. You can also use it to describe the writer’s academic achievement or the significance of their research. For instance, “Dr. Patel’s dissertation on sustainable agriculture received high praise from her colleagues.”

Remember that dissertation is a formal and specific term, so it is important to use it accurately in academic or professional contexts. Avoid using it in casual conversations or when referring to general research papers.

By following these guidelines and practicing with different sentence structures, you will become more comfortable using dissertation in your writing.

In conclusion, the examples provided demonstrate how sentences with ‘dissertation’ encompass a range of academic and research-related contexts. Whether discussing the process of writing a dissertation, providing guidelines for structuring it, or highlighting the significance of original research in a dissertation, these sentences underscore the importance and complexity of this academic endeavor. Through these varied examples, it becomes clear that a dissertation serves as a cornerstone of advanced education, requiring careful planning, rigorous research, and critical analysis to successfully contribute to one’s field of study.

By highlighting the various aspects and stages involved in writing a dissertation, these sentences illustrate the comprehensive nature of this academic task. From defining research objectives and developing a methodology, to analyzing findings and drawing meaningful conclusions, the dissertation plays a crucial role in advancing knowledge and understanding in a particular subject area. Ultimately, these examples underscore the rigour, dedication, and intellectual effort required to produce a high-quality dissertation that makes a valuable contribution to academia.

Related Posts

In Front or Infront: Which Is the Correct Spelling?

As an expert blogger with years of experience, I’ve delved… Read More » In Front or Infront: Which Is the Correct Spelling?

Targeted vs. Targetted: Correct Spelling Explained in English (US) Usage

Are you unsure about whether to use “targetted” or “targeted”?… Read More » Targeted vs. Targetted: Correct Spelling Explained in English (US) Usage

As per Request or As per Requested: Understanding the Correct Usage

Having worked in various office environments, I’ve often pondered the… Read More » As per Request or As per Requested: Understanding the Correct Usage

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Thesis Statements

Basics of thesis statements.

The thesis statement is the brief articulation of your paper's central argument and purpose. You might hear it referred to as simply a "thesis." Every scholarly paper should have a thesis statement, and strong thesis statements are concise, specific, and arguable. Concise means the thesis is short: perhaps one or two sentences for a shorter paper. Specific means the thesis deals with a narrow and focused topic, appropriate to the paper's length. Arguable means that a scholar in your field could disagree (or perhaps already has!).

Strong thesis statements address specific intellectual questions, have clear positions, and use a structure that reflects the overall structure of the paper. Read on to learn more about constructing a strong thesis statement.

Being Specific

This thesis statement has no specific argument:

Needs Improvement: In this essay, I will examine two scholarly articles to find similarities and differences.

This statement is concise, but it is neither specific nor arguable—a reader might wonder, "Which scholarly articles? What is the topic of this paper? What field is the author writing in?" Additionally, the purpose of the paper—to "examine…to find similarities and differences" is not of a scholarly level. Identifying similarities and differences is a good first step, but strong academic argument goes further, analyzing what those similarities and differences might mean or imply.

Better: In this essay, I will argue that Bowler's (2003) autocratic management style, when coupled with Smith's (2007) theory of social cognition, can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover.

The new revision here is still concise, as well as specific and arguable. We can see that it is specific because the writer is mentioning (a) concrete ideas and (b) exact authors. We can also gather the field (business) and the topic (management and employee turnover). The statement is arguable because the student goes beyond merely comparing; he or she draws conclusions from that comparison ("can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover").

Making a Unique Argument

This thesis draft repeats the language of the writing prompt without making a unique argument:

Needs Improvement: The purpose of this essay is to monitor, assess, and evaluate an educational program for its strengths and weaknesses. Then, I will provide suggestions for improvement.

You can see here that the student has simply stated the paper's assignment, without articulating specifically how he or she will address it. The student can correct this error simply by phrasing the thesis statement as a specific answer to the assignment prompt.

Better: Through a series of student interviews, I found that Kennedy High School's antibullying program was ineffective. In order to address issues of conflict between students, I argue that Kennedy High School should embrace policies outlined by the California Department of Education (2010).

Words like "ineffective" and "argue" show here that the student has clearly thought through the assignment and analyzed the material; he or she is putting forth a specific and debatable position. The concrete information ("student interviews," "antibullying") further prepares the reader for the body of the paper and demonstrates how the student has addressed the assignment prompt without just restating that language.

Creating a Debate

This thesis statement includes only obvious fact or plot summary instead of argument:

Needs Improvement: Leadership is an important quality in nurse educators.

A good strategy to determine if your thesis statement is too broad (and therefore, not arguable) is to ask yourself, "Would a scholar in my field disagree with this point?" Here, we can see easily that no scholar is likely to argue that leadership is an unimportant quality in nurse educators. The student needs to come up with a more arguable claim, and probably a narrower one; remember that a short paper needs a more focused topic than a dissertation.

Better: Roderick's (2009) theory of participatory leadership is particularly appropriate to nurse educators working within the emergency medicine field, where students benefit most from collegial and kinesthetic learning.

Here, the student has identified a particular type of leadership ("participatory leadership"), narrowing the topic, and has made an arguable claim (this type of leadership is "appropriate" to a specific type of nurse educator). Conceivably, a scholar in the nursing field might disagree with this approach. The student's paper can now proceed, providing specific pieces of evidence to support the arguable central claim.

Choosing the Right Words

This thesis statement uses large or scholarly-sounding words that have no real substance:

Needs Improvement: Scholars should work to seize metacognitive outcomes by harnessing discipline-based networks to empower collaborative infrastructures.

There are many words in this sentence that may be buzzwords in the student's field or key terms taken from other texts, but together they do not communicate a clear, specific meaning. Sometimes students think scholarly writing means constructing complex sentences using special language, but actually it's usually a stronger choice to write clear, simple sentences. When in doubt, remember that your ideas should be complex, not your sentence structure.

Better: Ecologists should work to educate the U.S. public on conservation methods by making use of local and national green organizations to create a widespread communication plan.

Notice in the revision that the field is now clear (ecology), and the language has been made much more field-specific ("conservation methods," "green organizations"), so the reader is able to see concretely the ideas the student is communicating.

Leaving Room for Discussion

This thesis statement is not capable of development or advancement in the paper:

Needs Improvement: There are always alternatives to illegal drug use.

This sample thesis statement makes a claim, but it is not a claim that will sustain extended discussion. This claim is the type of claim that might be appropriate for the conclusion of a paper, but in the beginning of the paper, the student is left with nowhere to go. What further points can be made? If there are "always alternatives" to the problem the student is identifying, then why bother developing a paper around that claim? Ideally, a thesis statement should be complex enough to explore over the length of the entire paper.

Better: The most effective treatment plan for methamphetamine addiction may be a combination of pharmacological and cognitive therapy, as argued by Baker (2008), Smith (2009), and Xavier (2011).

In the revised thesis, you can see the student make a specific, debatable claim that has the potential to generate several pages' worth of discussion. When drafting a thesis statement, think about the questions your thesis statement will generate: What follow-up inquiries might a reader have? In the first example, there are almost no additional questions implied, but the revised example allows for a good deal more exploration.

Thesis Mad Libs

If you are having trouble getting started, try using the models below to generate a rough model of a thesis statement! These models are intended for drafting purposes only and should not appear in your final work.

- In this essay, I argue ____, using ______ to assert _____.

- While scholars have often argued ______, I argue______, because_______.

- Through an analysis of ______, I argue ______, which is important because_______.

Words to Avoid and to Embrace

When drafting your thesis statement, avoid words like explore, investigate, learn, compile, summarize , and explain to describe the main purpose of your paper. These words imply a paper that summarizes or "reports," rather than synthesizing and analyzing.

Instead of the terms above, try words like argue, critique, question , and interrogate . These more analytical words may help you begin strongly, by articulating a specific, critical, scholarly position.

Read Kayla's blog post for tips on taking a stand in a well-crafted thesis statement.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Introductions

- Next Page: Conclusions

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- The Student Experience

- Financial Aid

- Degree Finder

- Undergraduate Arts & Sciences

- Departments and Programs

- Research, Scholarship & Creativity

- Centers & Institutes

- Geisel School of Medicine

- Guarini School of Graduate & Advanced Studies

- Thayer School of Engineering

- Tuck School of Business

Campus Life

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Athletics & Recreation

- Student Groups & Activities

- Residential Life

- [email protected] Contact & Department Info Mail

- About the Writing Center

- Hours & Location

- Appointments

- Undergraduate Sessions

- Graduate Sessions

- What To Expect at a Session

- Student Guides

- Guide for Students with Disabilities

- Sources and Citations Guide

- For Faculty

- Class Support

- Faculty Guidelines

- Work With Us

- Apply To Tutor

- Advice for Tutors

- Advice to Writing Assistants

- Diagnosing Problems: Ways of Reading Student Papers

- Responding to Problems: A Facilitative Approach

- Teaching Writing as a Process

Search form

- About Tutoring

The Thesis Sentence

The thesis sentence is arguably the most important sentence in an academic paper. Without a good, clear thesis that presents an intriguing arguable point, a paper risks becoming unfocused, aimless, not worth the reader's time.

The Challenge of the Thesis Sentence

Because the thesis sentence is the most important sentence of a paper, it is also the most difficult to write. Readers expect a great deal of a thesis sentence: they want it to powerfully and clearly indicate what the writer is going to say, why she is going to say it, and even how it is that she is going to go about getting it said. In other words, the job of the thesis sentence is to organize, predict, control, and define the paper's argument.

In many cases, a thesis sentence will not only present the paper's argument, it will also point to and direct the course that the argument is going to take. In other words, it may also include an "essay map" - i.e., phrases or clauses that map out for the reader (and the writer) the argument that is to come. In some cases, then, the thesis sentence not only promises an argument, it promises the structure of that argument as well.

The promises that a thesis sentence makes to a reader are important ones and must be kept. It's helpful sometimes to explain the thesis as a kind of contract between reader and writer: if this contract is broken, the reader will feel frustrated and betrayed. Accordingly, the writer must be very careful in the development of the thesis.

Working on the Thesis Sentence

Chances are if you've had trouble following or deciphering the argument of a paper, there's a problem with the thesis. If a tutor's first response to a paper is that he doesn't know what the paper is about, then the thesis sentence is either absent from the paper, or it's hiding. The first thing you might wish to do is to ask the writer what his thesis is. He may point to a particular sentence that he thinks is his thesis, giving you a very good place to start.

Let's say that you've read a paper in which you've encountered this thesis:

Although heterosexuality has long been regarded as the only natural expression of sexuality, this view has been recently and strongly challenged by the gay rights movement.

What's wrong with this sentence? Many things, the most troublesome of which is that it argues nothing. Who is going to deny that the heteronormative view has been challenged by the gay rights movement? At this point, you need to ask the writer some questions. In what specific ways has the gay rights movement challenged heterosexuality? Do these ways seem reasonable to the writer? Why or why not? What argument does he intend to make about this topic? Why does he want to make it? To whom does he want to make it?

After giving the writer some time to think about and talk about these questions, you'll probably want to bring up another problem that is certain to arise out of a thesis like this one: the matter of structure. Any paper that follows a thesis like this one is likely to ramble. How can the reader figure out what all the supporting paragraphs are doing when the argument itself is so ill-defined? You'll want to show the writer that a strong thesis suggests - even helps to create - strong topic sentences. (More on this when we consider matters of structure, below).

But before we move on to other matters, let's consider the problem of this thesis from another angle: its style. We can see without difficulty that the sentence presents us with at least two stylistic problems: 1) this thesis, which should be the most powerful sentence of the paper, employs the passive voice, and 2) the introductory clause functions as a dangling modifier (who regards heterosexuality as the only natural way to express sexuality?).

Both stylistic problems point to something at work in the sentence: the writer obliterates the actors - heterosexuals and homosexuals alike - by using the dangling modifier and the passive voice. Why does he do that? Is he avoiding naming the actors in these sentences because he's not comfortable with the positions they take? Is he unable to declare himself because he feels paralyzed by the sense that he must write a paper that is politically correct? Or does he obliterate the actors with the passive voice because he himself wishes to remain passive on this topic?

These are questions to pose to the writer, though they must be posed gently. In fact, you might gently pose these questions via a discussion of style. For instance, you might also suggest that the writer rewrite the sentence in the active voice:

Although our society has long regarded heterosexuality as the only natural expression of sexuality, members of the gay rights movement have challenged this view strongly.

This active construction helps us to see clearly what's missing:

Although our society has long regarded heterosexuality as the only natural expression of sexuality, members of the gay rights movement have challenged this view strongly, arguing XYZ.

This more active construction also makes it clear that merely enumerating the points the author wants to make is not the same thing as creating an argument. The writer should now be able to see that he needs to go one step further - he needs to reveal his own position on the gay rights movement. The rest of the paper will develop this position.

In short, there are many ways to begin work on a writer's thesis sentences. Almost all of them will lead you to other matters important to the paper's success: its structure, its language, its style. Try to make any conversation you have about thesis sentences point to other problems with the writing. Not only is this strategy efficient, but it also encourages a writer to see how important a thesis is to the overall success of his essay.

Talking Your Way to a Workable Thesis

For the sake of making (we hope) a somewhat humorous illustration of the matter at hand, we offer the following scenario, which shows how tutor and tutee can talk their way to a workable thesis - and, indeed, to a good essay. So sit back, and enjoy this "break" in your training.

Imagine (though it is indeed quite a stretch) that a freshman composition teacher has the audacity to assign a paper on cats (the animals, not the play). The students may write any kind of paper they like - narration, description, compare/contrast, etc. - as long as their essays contain a thesis (that is, that they argue some point) concerning cats. A writer comes to you for help in developing her thesis. You read the assignment, and then you tell the writer that she first must choose the kind of paper she would like to do. She decides to do a narrative because she thinks she has more freedom in the narrative form. Then you ask her what she has to say about cats. "I don't like them," is her reply.

"OK," you say, "that's a start. Why don't you like them?" The writer has lots of reasons: they smell, they're aloof, they shed, they keep you up nights when they're in heat, they're very middle class, they steal food off of the table, they don't get along with dogs (the writer loves dogs), and on, and on. After brainstorming for a while, you tell the writer to choose a few points on which she'd like to focus - preferably those points that she feels strongly about or those which seem unusual. She picks three: cats smell, they steal food, and they are middle class. She offers her thesis: "I don't like cats because they are smelly, thieving, and middle class."

"O.K.," you say, "It's not a very sophisticated thesis but we can use it for now. After all, it defines your stance, it controls your subject, it organizes your argument, and it predicts your strategy - all the things that a thesis ought to do. Now let's consider how to develop the thesis, point by point."

You begin to ask questions about cats and their smell. "What do they smell like?" you say. The writer thinks awhile, and then says, "They smell like dirty gym shorts, like old hamburgers, like my eighth-grade math teacher's breath." The writer laughs, particularly fond of the final simile. Then she adds, "My boyfriend has a cat. A Tom. When he moved into his first apartment, that cat sprayed all over the place, you know, marking his territory. The place stunk so bad that I couldn't even go there for a week. Can you imagine? Your boyfriend gets his first apartment, and you can't even go in the place for a week?"

The writer has sparked your imagination; you think that she can spark her teacher's imagination as well. "Why don't you do your narrative about your boyfriend's cat? You could tell the story - or you could make up a story - about going over there for dinner, hoping for a romantic evening, and being put off by the cat." The writer likes this idea and goes off to write her draft. She returns with the following story about her boyfriend and his cat.

She was hoping for a romantic dinner; he was making her favorite meal. She could smell the T-bone and the apple pie before she even got to his door. But when she opened the door, her appetite was obliterated: the smell of cat spray smelled worse than her eighth-grade math teacher's breath. Of course, because she remained hopeful for a romantic evening, she put on her best face, tried not to grimace, and gave her boyfriend the flowers she'd picked up on the way. They chat; everything is going fine; he goes to the kitchen to check on dinner; she hears his shriek. The cat has stolen all of the food! Upon searching, they find the cat under the sofa, not only with their dinner, but with the writer's wallet, her favorite picture of her mom torn in half, her new leather jacket now full of cat hairs. This cat not only stinks, he's a thief as well. Still, the evening need not be a total waste. They order pizza, have some wine. She and her man talk; their moods improve, and she decides that it might be a nice time to kiss. She pulls the old yawn trick to get her arm around him, and just as she's ready to kiss him the cat jumps into his lap. "Oh, Pookie, Pookie, Pookie," her boyfriend says, giving himself over to the purring cat. "Damn lap cat," the writer says to herself, and leaves it at that. She has written a paper illustrating that cats are smelly, thieving, and middle class. She has fulfilled her thesis.

Now, you like this paper. It's got a great voice, and it's got humor. You feel, however, that the writer should refine the thesis. It has served the writer well in helping her to organize, control, predict, and define her essay; however, she needs now to consider how to choose words and a tone which will hook the reader and reel him in. You explain to the writer that her thesis can be humorous, that she can feel free to be extreme, because a funny, exaggerated thesis would suit this funny, exaggerated paper.

After some doodling and some dialogue, the writer comes up with the following thesis: "All cats should be exterminated because they are the stinking, kleptomaniacal darlings of the bourgeoisie." You laugh; you like it. Moreover, the thesis has given the writer an ending for her essay: she exterminates the cat in her boyfriend's microwave, convinces him to get a goldfish instead, and the two of them live happily ever after. The writer is happy. The tutor is happy. The paper works.

While you will likely not encounter a "cat" assignment at Dartmouth, this sort of experience with writing a thesis is a common one. Even when papers are more sophisticated than this one - even when the subject is Hitler's rise to power, or Freud's treatment of taboo - writers will often write a working thesis, one that guides them through the writing process. Then they will return to the thesis, sometimes several times before their paper is finished, revising it to better fit their paper's increasingly refined argument and tone.

Polishing the Thesis Sentence

Look at the sentence's structure. Is the main idea of the paper placed appropriately in the main clause? If there are parallel points made in the paper, does the thesis sentence signal this to the reader via some parallel structure? If the paper makes an interesting but necessary aside, is that aside predicted - perhaps in a parenthetical element? Remember: the structure of the thesis sentence also signals much to the reader about the structure of the argument. Be sure that the thesis reflects, reliably, what the paper itself is going to say.

As to the style of the sentence: hold the thesis sentence to the highest stylistic standards. Help a writer to make sure that it is as clear and concise as it can be, and that its language and phrasing reflect confidence, eloquence, and grace.

While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

Researching and Writing a Paper: Thesis Sentences

- Outline Note-Taking

- Summarizing

- Bibliography / Annotated Bibliography

Thesis Sentences

- Ideas for Topics

- The Big List of Databases and Resource Sources

- Keywords and Controlled Vocabulary

- Full Text Advice

- Database Searching Videos!

- How to Read a Scholarly Article.

- Citation Styles

- Citation Videos!

- Citation Tips & Tricks

- Videos about Evaluating Sources!

- Unreliable Sources and 'Fake News'

- An Outline for Writing!

- Formatting your paper!

Synopsis: "Tell them what you are going to tell them (i.e., your thesis statement), tell them (the body of your paper), tell them what you told them (your conclusion)."

Can you spot the thesis sentence(s) in this paragraph? A thesis sentence is a single sentence that summarizes the main idea of your topic and declares your position on it. This single sentence (sometimes two, almost never three) is the result of your thinking about the assignment and the information you have found. Before you can create a good thesis statement you need to collect and organize information, look for connections between known facts, and think about the significance of these connections. Most essays, whether compare/contrast, argumentative, explanatory, or narrative, have thesis statements that take a position and present evidence for that position being true. Unless your essay is simply to inform, your thesis is considered 'persuasive'. A persuasive thesis usually contains an opinion and the reason why your opinion is true. (A good way to write a thesis statement is to consider what is true in the articles, etc., you have read, and then describe how you know it is true. When you can do that in one or two sentences you probably have a good thesis sentence.) Once you have thought about the information you have found, you will likely have a “working thesis” that has the main idea of your paper and you will also have some thoughts about how to support your thesis statement with evidence. Both how you show the evidence that supports your thesis statement, and the exact wording of your thesis statement, are likely to need to change some as you do more reading and as you write. This is natural and quite common.

- Length: A thesis statement can be short or long, depending on how many points it mentions. Usually, it is only one relatively short and informative sentence. It contains at least two clauses, usually an independent clause (the opinion, which is usually stated first) and a dependent clause (the reasons for that opinion, usually coming after the opinion). Aim for a single sentence that is maybe two lines long, or maybe about 30 to 40 words long.

- Position: A thesis statement belongs at the beginning of an essay. It is a sentence that tells the reader what the writer is going to discuss. (Teachers will have different preferences for approximately where the thesis should be, but generally it is in the introduction paragraph, often within the last two or three sentences of that paragraph.)

- Strength: For a persuasive thesis to be strong, it needs to be arguable. This means that the statement is somewhat not obvious (to people unfamiliar with the articles/books/etc. you have been reading), and it is not something that everyone agrees is true. (The body paragraphs of your paper explain why you are convinced your thesis statement is true.)

Writing a thesis statement takes more thought than many other parts of an essay. But, because a thesis statement summarizes your entire argument in just a few words, it is worth taking the time to compose this sentence as early in your paper-writing as possible. It can help focus your research and how you present your evidence so that your essay is informative, focused, and gives your readers something to think about. (Do not worry if you discover that you can write a thesis sentence that better summarizes/introduces your paper after you write your conclusion - by the time you 'finish' your paper you have thought a lot more about what you need, or want, to say. So, it is not surprising that you might discover a better way to describe your paper than you had when you started your paper.)

*** Questions or confusions about anything on this page, in this LibGuide, or anything else? You can Ask Us Questions ! ***

- << Previous: Bibliography / Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Ideas for Topics >>

- Last Updated: Apr 23, 2024 10:24 AM

- URL: https://libguides.rtc.edu/researching_and_writing

- How to Write an Abstract for a Dissertation or Thesis

- Doing a PhD

What is a Thesis or Dissertation Abstract?

The Cambridge English Dictionary defines an abstract in academic writing as being “ a few sentences that give the main ideas in an article or a scientific paper ” and the Collins English Dictionary says “ an abstract of an article, document, or speech is a short piece of writing that gives the main points of it ”.

Whether you’re writing up your Master’s dissertation or PhD thesis, the abstract will be a key element of this document that you’ll want to make sure you give proper attention to.

What is the Purpose of an Abstract?

The aim of a thesis abstract is to give the reader a broad overview of what your research project was about and what you found that was novel, before he or she decides to read the entire thesis. The reality here though is that very few people will read the entire thesis, and not because they’re necessarily disinterested but because practically it’s too large a document for most people to have the time to read. The exception to this is your PhD examiner, however know that even they may not read the entire length of the document.

Some people may still skip to and read specific sections throughout your thesis such as the methodology, but the fact is that the abstract will be all that most read and will therefore be the section they base their opinions about your research on. In short, make sure you write a good, well-structured abstract.

How Long Should an Abstract Be?

If you’re a PhD student, having written your 100,000-word thesis, the abstract will be the 300 word summary included at the start of the thesis that succinctly explains the motivation for your study (i.e. why this research was needed), the main work you did (i.e. the focus of each chapter), what you found (the results) and concluding with how your research study contributed to new knowledge within your field.

Woodrow Wilson, the 28th President of the United States of America, once famously said:

The point here is that it’s easier to talk open-endedly about a subject that you know a lot about than it is to condense the key points into a 10-minute speech; the same applies for an abstract. Three hundred words is not a lot of words which makes it even more difficult to condense three (or more) years of research into a coherent, interesting story.

What Makes a Good PhD Thesis Abstract?

Whilst the abstract is one of the first sections in your PhD thesis, practically it’s probably the last aspect that you’ll ending up writing before sending the document to print. The reason being that you can’t write a summary about what you did, what you found and what it means until you’ve done the work.

A good abstract is one that can clearly explain to the reader in 300 words:

- What your research field actually is,

- What the gap in knowledge was in your field,

- The overarching aim and objectives of your PhD in response to these gaps,

- What methods you employed to achieve these,

- You key results and findings,

- How your work has added to further knowledge in your field of study.

Another way to think of this structure is:

- Introduction,

- Aims and objectives,

- Discussion,

- Conclusion.

Following this ‘formulaic’ approach to writing the abstract should hopefully make it a little easier to write but you can already see here that there’s a lot of information to convey in a very limited number of words.

How Do You Write a Good PhD Thesis Abstract?

The biggest challenge you’ll have is getting all the 6 points mentioned above across in your abstract within the limit of 300 words . Your particular university may give some leeway in going a few words over this but it’s good practice to keep within this; the art of succinctly getting your information across is an important skill for a researcher to have and one that you’ll be called on to use regularly as you write papers for peer review.

Keep It Concise

Every word in the abstract is important so make sure you focus on only the key elements of your research and the main outcomes and significance of your project that you want the reader to know about. You may have come across incidental findings during your research which could be interesting to discuss but this should not happen in the abstract as you simply don’t have enough words. Furthermore, make sure everything you talk about in your thesis is actually described in the main thesis.

Make a Unique Point Each Sentence

Keep the sentences short and to the point. Each sentence should give the reader new, useful information about your research so there’s no need to write out your project title again. Give yourself one or two sentences to introduce your subject area and set the context for your project. Then another sentence or two to explain the gap in the knowledge; there’s no need or expectation for you to include references in the abstract.

Explain Your Research

Some people prefer to write their overarching aim whilst others set out their research questions as they correspond to the structure of their thesis chapters; the approach you use is up to you, as long as the reader can understand what your dissertation or thesis had set out to achieve. Knowing this will help the reader better understand if your results help to answer the research questions or if further work is needed.

Keep It Factual

Keep the content of the abstract factual; that is to say that you should avoid bringing too much or any opinion into it, which inevitably can make the writing seem vague in the points you’re trying to get across and even lacking in structure.

Write, Edit and Then Rewrite

Spend suitable time editing your text, and if necessary, completely re-writing it. Show the abstract to others and ask them to explain what they understand about your research – are they able to explain back to you each of the 6 structure points, including why your project was needed, the research questions and results, and the impact it had on your research field? It’s important that you’re able to convey what new knowledge you contributed to your field but be mindful when writing your abstract that you don’t inadvertently overstate the conclusions, impact and significance of your work.

Thesis and Dissertation Abstract Examples

Perhaps the best way to understand how to write a thesis abstract is to look at examples of what makes a good and bad abstract.

Example of A Bad Abstract

Let’s start with an example of a bad thesis abstract:

In this project on “The Analysis of the Structural Integrity of 3D Printed Polymers for use in Aircraft”, my research looked at how 3D printing of materials can help the aviation industry in the manufacture of planes. Plane parts can be made at a lower cost using 3D printing and made lighter than traditional components. This project investigated the structural integrity of EBM manufactured components, which could revolutionise the aviation industry.

What Makes This a Bad Abstract

Hopefully you’ll have spotted some of the reasons this would be considered a poor abstract, not least because the author used up valuable words by repeating the lengthy title of the project in the abstract.

Working through our checklist of the 6 key points you want to convey to the reader:

- There has been an attempt to introduce the research area , albeit half-way through the abstract but it’s not clear if this is a materials science project about 3D printing or is it about aircraft design.

- There’s no explanation about where the gap in the knowledge is that this project attempted to address.

- We can see that this project was focussed on the topic of structural integrity of materials in aircraft but the actual research aims or objectives haven’t been defined.

- There’s no mention at all of what the author actually did to investigate structural integrity. For example was this an experimental study involving real aircraft, or something in the lab, computer simulations etc.

- The author also doesn’t tell us a single result of his research, let alone the key findings !

- There’s a bold claim in the last sentence of the abstract that this project could revolutionise the aviation industry, and this may well be the case, but based on the abstract alone there is no evidence to support this as it’s not even clear what the author did .

This is an extreme example but is a good way to illustrate just how unhelpful a poorly written abstract can be. At only 71 words long, it definitely hasn’t maximised the amount of information that could be presented and the what they have presented has lacked clarity and structure.

A final point to note is the use of the EBM acronym, which stands for Electron Beam Melting in the context of 3D printing; this is a niche acronym for the author to assume that the reader would know the meaning of. It’s best to avoid acronyms in your abstract all together even if it’s something that you might expect most people to know about, unless you specifically define the meaning first.

Example of A Good Abstract

Having seen an example of a bad thesis abstract, now lets look at an example of a good PhD thesis abstract written about the same (fictional) project:

Additive manufacturing (AM) of titanium alloys has the potential to enable cheaper and lighter components to be produced with customised designs for use in aircraft engines. Whilst the proof-of-concept of these have been promising, the structural integrity of AM engine parts in response to full thrust and temperature variations is not clear.

The primary aim of this project was to determine the fracture modes and mechanisms of AM components designed for use in Boeing 747 engines. To achieve this an explicit finite element (FE) model was developed to simulate the environment and parameters that the engine is exposed to during flight. The FE model was validated using experimental data replicating the environmental parameters in a laboratory setting using ten AM engine components provided by the industry sponsor. The validated FE model was then used to investigate the extent of crack initiation and propagation as the environment parameters were adjusted.

This project was the first to investigate fracture patterns in AM titanium components used in aircraft engines; the key finding was that the presence of cavities within the structures due to errors in the printing process, significantly increased the risk of fracture. Secondly, the simulations showed that cracks formed within AM parts were more likely to worsen and lead to component failure at subzero temperatures when compared to conventionally manufactured parts. This has demonstrated an important safety concern which needs to be addressed before AM parts can be used in commercial aircraft.

What Makes This a Good Abstract

Having read this ‘good abstract’ you should have a much better understand about what the subject area is about, where the gap in the knowledge was, the aim of the project, the methods that were used, key results and finally the significance of these results. To break these points down further, from this good abstract we now know that:

- The research area is around additive manufacturing (i.e. 3D printing) of materials for use in aircraft.

- The gap in knowledge was how these materials will behave structural when used in aircraft engines.

- The aim was specifically to investigate how the components can fracture.

- The methods used to investigate this were a combination of computational and lab based experimental modelling.

- The key findings were the increased risk of fracture of these components due to the way they are manufactured.

- The significance of these findings were that it showed a potential risk of component failure that could comprise the safety of passengers and crew on the aircraft.

The abstract text has a much clearer flow through these different points in how it’s written and has made much better use of the available word count. Acronyms have even been used twice in this good abstract but they were clearly defined the first time they were introduced in the text so that there was no confusion about their meaning.

The abstract you write for your dissertation or thesis should succinctly explain to the reader why the work of your research was needed, what you did, what you found and what it means. Most people that come across your thesis, including any future employers, are likely to read only your abstract. Even just for this reason alone, it’s so important that you write the best abstract you can; this will not only convey your research effectively but also put you in the best light possible as a researcher.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

Published on 15 September 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 5 December 2023.

A thesis is a type of research paper based on your original research. It is usually submitted as the final step of a PhD program in the UK.

Writing a thesis can be a daunting experience. Indeed, alongside a dissertation , it is the longest piece of writing students typically complete. It relies on your ability to conduct research from start to finish: designing your research , collecting data , developing a robust analysis, drawing strong conclusions , and writing concisely .

Thesis template

You can also download our full thesis template in the format of your choice below. Our template includes a ready-made table of contents , as well as guidance for what each chapter should include. It’s easy to make it your own, and can help you get started.

Download Word template Download Google Docs template

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

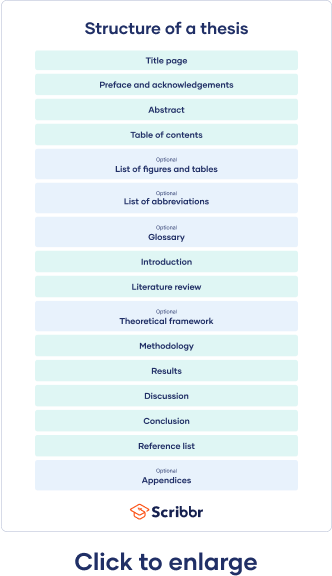

Table of contents

Thesis vs. thesis statement, how to structure a thesis, acknowledgements or preface, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review, methodology, reference list, proofreading and editing, defending your thesis, frequently asked questions about theses.

You may have heard the word thesis as a standalone term or as a component of academic writing called a thesis statement . Keep in mind that these are two very different things.

- A thesis statement is a very common component of an essay, particularly in the humanities. It usually comprises 1 or 2 sentences in the introduction of your essay , and should clearly and concisely summarise the central points of your academic essay .

- A thesis is a long-form piece of academic writing, often taking more than a full semester to complete. It is generally a degree requirement to complete a PhD program.

- In many countries, particularly the UK, a dissertation is generally written at the bachelor’s or master’s level.

- In the US, a dissertation is generally written as a final step toward obtaining a PhD.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

The final structure of your thesis depends on a variety of components, such as:

- Your discipline

- Your theoretical approach

Humanities theses are often structured more like a longer-form essay . Just like in an essay, you build an argument to support a central thesis.

In both hard and social sciences, theses typically include an introduction , literature review , methodology section , results section , discussion section , and conclusion section . These are each presented in their own dedicated section or chapter. In some cases, you might want to add an appendix .

Thesis examples

We’ve compiled a short list of thesis examples to help you get started.

- Example thesis #1: ‘Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the “Noble Savage” on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807’ by Suchait Kahlon.

- Example thesis #2: ‘”A Starving Man Helping Another Starving Man”: UNRRA, India, and the Genesis of Global Relief, 1943-1947’ by Julian Saint Reiman.

The very first page of your thesis contains all necessary identifying information, including:

- Your full title

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date.

Sometimes the title page also includes your student ID, the name of your supervisor, or the university’s logo. Check out your university’s guidelines if you’re not sure.

Read more about title pages

The acknowledgements section is usually optional. Its main point is to allow you to thank everyone who helped you in your thesis journey, such as supervisors, friends, or family. You can also choose to write a preface , but it’s typically one or the other, not both.

Read more about acknowledgements Read more about prefaces

An abstract is a short summary of your thesis. Usually a maximum of 300 words long, it’s should include brief descriptions of your research objectives , methods, results, and conclusions. Though it may seem short, it introduces your work to your audience, serving as a first impression of your thesis.

Read more about abstracts

A table of contents lists all of your sections, plus their corresponding page numbers and subheadings if you have them. This helps your reader seamlessly navigate your document.

Your table of contents should include all the major parts of your thesis. In particular, don’t forget the the appendices. If you used heading styles, it’s easy to generate an automatic table Microsoft Word.

Read more about tables of contents

While not mandatory, if you used a lot of tables and/or figures, it’s nice to include a list of them to help guide your reader. It’s also easy to generate one of these in Word: just use the ‘Insert Caption’ feature.

Read more about lists of figures and tables

If you have used a lot of industry- or field-specific abbreviations in your thesis, you should include them in an alphabetised list of abbreviations . This way, your readers can easily look up any meanings they aren’t familiar with.

Read more about lists of abbreviations

Relatedly, if you find yourself using a lot of very specialised or field-specific terms that may not be familiar to your reader, consider including a glossary . Alphabetise the terms you want to include with a brief definition.

Read more about glossaries

An introduction sets up the topic, purpose, and relevance of your thesis, as well as expectations for your reader. This should:

- Ground your research topic , sharing any background information your reader may need

- Define the scope of your work

- Introduce any existing research on your topic, situating your work within a broader problem or debate

- State your research question(s)

- Outline (briefly) how the remainder of your work will proceed

In other words, your introduction should clearly and concisely show your reader the “what, why, and how” of your research.

Read more about introductions

A literature review helps you gain a robust understanding of any extant academic work on your topic, encompassing:

- Selecting relevant sources

- Determining the credibility of your sources

- Critically evaluating each of your sources

- Drawing connections between sources, including any themes, patterns, conflicts, or gaps

A literature review is not merely a summary of existing work. Rather, your literature review should ultimately lead to a clear justification for your own research, perhaps via:

- Addressing a gap in the literature

- Building on existing knowledge to draw new conclusions

- Exploring a new theoretical or methodological approach

- Introducing a new solution to an unresolved problem

- Definitively advocating for one side of a theoretical debate

Read more about literature reviews

Theoretical framework

Your literature review can often form the basis for your theoretical framework, but these are not the same thing. A theoretical framework defines and analyses the concepts and theories that your research hinges on.

Read more about theoretical frameworks

Your methodology chapter shows your reader how you conducted your research. It should be written clearly and methodically, easily allowing your reader to critically assess the credibility of your argument. Furthermore, your methods section should convince your reader that your method was the best way to answer your research question.

A methodology section should generally include:

- Your overall approach ( quantitative vs. qualitative )

- Your research methods (e.g., a longitudinal study )

- Your data collection methods (e.g., interviews or a controlled experiment

- Any tools or materials you used (e.g., computer software)

- The data analysis methods you chose (e.g., statistical analysis , discourse analysis )

- A strong, but not defensive justification of your methods

Read more about methodology sections

Your results section should highlight what your methodology discovered. These two sections work in tandem, but shouldn’t repeat each other. While your results section can include hypotheses or themes, don’t include any speculation or new arguments here.

Your results section should:

- State each (relevant) result with any (relevant) descriptive statistics (e.g., mean , standard deviation ) and inferential statistics (e.g., test statistics , p values )

- Explain how each result relates to the research question

- Determine whether the hypothesis was supported

Additional data (like raw numbers or interview transcripts ) can be included as an appendix . You can include tables and figures, but only if they help the reader better understand your results.

Read more about results sections

Your discussion section is where you can interpret your results in detail. Did they meet your expectations? How well do they fit within the framework that you built? You can refer back to any relevant source material to situate your results within your field, but leave most of that analysis in your literature review.

For any unexpected results, offer explanations or alternative interpretations of your data.

Read more about discussion sections

Your thesis conclusion should concisely answer your main research question. It should leave your reader with an ultra-clear understanding of your central argument, and emphasise what your research specifically has contributed to your field.

Why does your research matter? What recommendations for future research do you have? Lastly, wrap up your work with any concluding remarks.

Read more about conclusions

In order to avoid plagiarism , don’t forget to include a full reference list at the end of your thesis, citing the sources that you used. Choose one citation style and follow it consistently throughout your thesis, taking note of the formatting requirements of each style.

Which style you choose is often set by your department or your field, but common styles include MLA , Chicago , and APA.

Create APA citations Create MLA citations

In order to stay clear and concise, your thesis should include the most essential information needed to answer your research question. However, chances are you have many contributing documents, like interview transcripts or survey questions . These can be added as appendices , to save space in the main body.

Read more about appendices

Once you’re done writing, the next part of your editing process begins. Leave plenty of time for proofreading and editing prior to submission. Nothing looks worse than grammar mistakes or sloppy spelling errors!

Consider using a professional thesis editing service to make sure your final project is perfect.

Once you’ve submitted your final product, it’s common practice to have a thesis defense, an oral component of your finished work. This is scheduled by your advisor or committee, and usually entails a presentation and Q&A session.

After your defense, your committee will meet to determine if you deserve any departmental honors or accolades. However, keep in mind that defenses are usually just a formality. If there are any serious issues with your work, these should be resolved with your advisor way before a defense.

The conclusion of your thesis or dissertation shouldn’t take up more than 5-7% of your overall word count.

When you mention different chapters within your text, it’s considered best to use Roman numerals for most citation styles. However, the most important thing here is to remain consistent whenever using numbers in your dissertation .

If you only used a few abbreviations in your thesis or dissertation, you don’t necessarily need to include a list of abbreviations .

If your abbreviations are numerous, or if you think they won’t be known to your audience, it’s never a bad idea to add one. They can also improve readability, minimising confusion about abbreviations unfamiliar to your reader.

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical first steps in your writing process. It helps you to lay out and organise your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding what kind of research you’d like to undertake.

Generally, an outline contains information on the different sections included in your thesis or dissertation, such as:

- Your anticipated title

- Your abstract

- Your chapters (sometimes subdivided into further topics like literature review, research methods, avenues for future research, etc.)

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2023, December 05). What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/thesis-ultimate-guide/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, dissertation & thesis outline | example & free templates, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction.

Types of Sentence to Master: A Hands-On Tour to English Grammar

Table of contents

- 1 Main Four Kinds of Sentences in English

- 2 4 Different Types of Sentences in One Comparison Table

- 3 Saying What Is What: Exploring Declarative Sentences

- 4.1 The Language of Strong Emotion: Exclamatory Sentences

- 5.1 How to Improve Your Writing: Trying Different Sentence Styles

- 5.2 Offer Diversity to Improve the Flow

- 5.3 Final Advice After Reviewing Different Sentence Types

Sentences are the core of any academic work either dissertation or thesis. Constructing them in different ways can both enrich your reader’s experience and confuse them with obscure information. In today’s material, we aim to do the first ─ supplement you with critical info about sentences, so later you will:

- Discover 4 types of sentences and how to use any type of sentence you need.

- Find out various types of sentences according to their structure and their definitions.

- Review the comprehensive table with all four types of sentences and many examples for every kind of sentences.

- Find valuable tips and practical methods to enhance your writing skills.

- Start by exploring the basics of sentence types, their role, and the structure presented below.

Make sure to review each point so that you can create not a pile of confusing sentences but a comprehensive text that flows smoothly from one sentence to another!

Main Four Kinds of Sentences in English

Have you ever thought you could express yourself more clearly with a proper sentence construction process? Indeed, for effective communication, all students must grasp the nuances of language, especially the four types of sentences.

In English, there are four basic types of sentences: declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamatory. They all have a distinct function, whether making a declaration, posing a question, issuing instructions, or describing feelings.

4 Different Types of Sentences in One Comparison Table

We’ll examine the four types of sentences in the following comparison chart. For each type, we’ll explain what it does and how it’s built by showing examples from everyday talk.

Saying What Is What: Exploring Declarative Sentences

Declarative ones are the most prevalent kind of phrases. Their primary duty is to tell information without asking questions or giving orders. Thus, using different sentences and including details in your statements makes you clearer in communication.

Take a look at these declarative sentences:

- Roses are red, and violets are blue.

- His students play the violin perfectly.

They ask nothing and don’t make orders; they just state the facts or share their opinions.

Structurally, declarative sentences operate according to the subject-verb-object pattern: the subject performs the action indicated by the verb upon an object. How do you recognize them?

Declarative sentences typically have a period at the end. They have a calm tone, although they may disclose moods depending on the circumstances. Accordingly, they are the building blocks of both written and spoken communication.

Just Asking: About Interrogative Sentences

Want to ask a question? It’s time to craft some interrogative sentences! Their main function is to provoke a response and get certain information from others.

Here are a few examples of interrogative sentences:

- Where is the independent clause in this sentence?

- Are you available for a quick review?

- Have you been in this restaurant before?

- Who joined you at the concert?

Any interrogative sentence seeks to identify and gather answers. For this purpose, from a structural standpoint, they begin with “ who ,” “ what ,” “ where ,” “ how ,” “ why ,” and “ when ” question elements. At the end of the sentence, there is an obligatory question mark. Thus, these elements help define the information being sought.

Sometimes, interrogative sentences switch the order of the subject and verb to form yes/no questions. As a teaching instance, “ She is going to the market ” transforms into a question: “ Is she going to the market? ”.