TWO WRITING TEACHERS

A meeting place for a world of reflective writers.

Literary Essays: Setting the Stage

As part my MFA program, I’ve had to write eight page papers on a paragraph or two of text. That’s a lot of words about not too many words. I’ve also watched my daughters draft critical analyses on literary works in both high school and college. Writing a literary essay is a lifelong skill that we are all working to master, so what can we expect our elementary writers to be able to do, and how can we provide instruction so they can succeed at a sophisticated task.

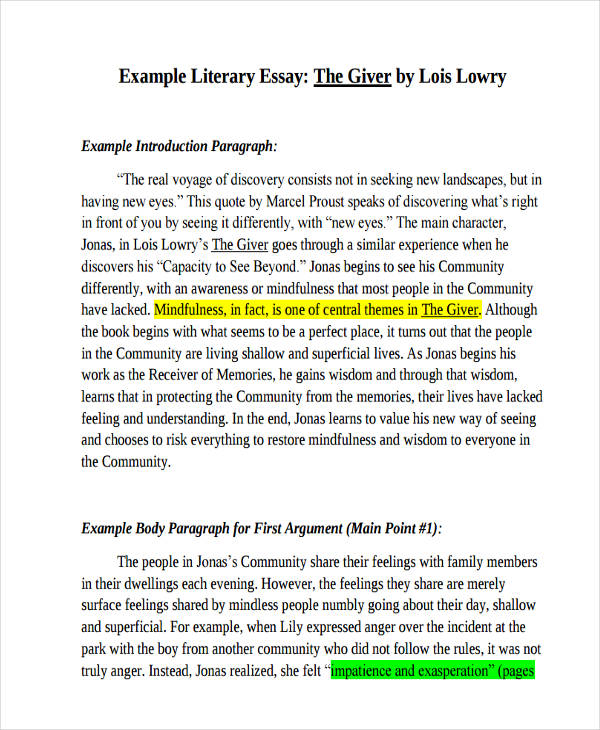

As with most writing units, the first thing I show students is a chart with the steps involved in writing a literary essay, a final product, and the student-facing checklist for opinion writing. Strong literary essays have a claim that is supported through text and interpretation, and it’s important for students to understand this concept.

More than anything else, a strong literary essay requires close reading. I teach students to read a passage many times, using different lenses each time. In this example, I have marked up the text, Spaghetti by Cynthia Rylant. This short story and many others can be found in Every Living Thing.

One of the ways I teach students to do this kind of work is to present them with a chart that looks something like this:

That way, each sticky note represents what you’re looking for in a read-through, what you might mark up with a specific color. These concepts might change depending on your students, but the idea of reading with just one particular focus is important. If you haven’t read Falling in Love With Close Reading by Kate Roberts and Chris Lehman, you will get lots of ideas about how to implement this sort of work from their book.

Depending on your students, you might want to consider making short text packets. Typed versions of favorite picture books work well, as well as poems. It’s important that whatever texts you use, students can (and are willing) to read them several times. Although I am always revamping and updating my short text collections, some tested and true texts are:

Picture Books

- Crow Call by Lois Lowry

- When I Was Young in the Mountains by Cynthia Rylant

- The Stranded Whale by Jane Yolen

- Owl Moon by Jane Yolen

- The Table Where Rich People Sit by Byrd Baylor

- A Day’s Work by Eve Bunting

Short Texts/Story Collections

- Hey World, Here I Am by Jean Little

- Every Living Thing by Cynthia Rylant

- Knots in My Yoyo String by Jerry Spinelli

Additionally, almost any poem works for analysis, and literary essays are a wonderful pathway to infuse poetry into your students’ lives.

Once you have students reading their texts over and over and marking it up, then it’s time to develop some more in-depth thinking. I have several examples of this that I keep in my teaching notebook.

The chart on the right tells students how to do this work and the examples show them what the work looks like. Both are important. I have to say that I have come to many new realizations–had many authentic a-ha moments–by using repeated thinking stems. It’s a powerful process if students have the time and the stamina to really take a deep dive into their thinking.

Once students have worked through their thinking, they can think about what they have the most to say about, and that decision helps drive the direction of their essay. The follwing chart works well for sorting through their thoughts and patches of thinking.

At this point, most students are ready to plan their essays. Again, I give them a chart of how to do it, and examples of what the work might look like.

I can’t guarantee that everyone will write prize-winning essays, but I will say that this sort of work is important for developing independent thinkers with stamina and appreciation for the work of writing.

Share this:

Published by Melanie Meehan

I am the Writing and Social Studies Coordinator in Simsbury, CT, and I love what I do. I get to write and inspire others to write! Additionally, I am the mom to four fabulous daughters and the wife of a great husband. View all posts by Melanie Meehan

9 thoughts on “ Literary Essays: Setting the Stage ”

You made it look so simple with all of the charts/visuals you share with us! (We both know this kind of unit isn’t so I appreciate you showing the steps involved.)

There is a lot of great thinking here to mull over. Thanks for providing such great information!

That’s super fabulous, I am a school owner of a Center of foreign languages and I teach English and French, here in Patras, Greece.I teach all levels and prepare students for certificate or diploma exams, they start at 6 and finish at 13 years old or later. This year I intend to have extra offered classes about writing stories, especially a team of 8 girls(6th grade) were begging me literally since last year because they write stories themselves! Essay writing is a crucial part of writing essays when the time comes to sit the exams so they need to know the craft of doing it. More girls heard about that from their siblings and now I have another group of 5th grade! I would love to have some models to show them and help them with their writing process! That would be awesome! Thank you, so much!

Reading this post brings me back to a world before the teaching of writing became an actual thing. In my day, you learned grammar and spelling and that an essay consisted of 5 paragraphs with a beginning, ending and two or three well supported ideas in the middle. We’ve come a long way. Sometimes I wonder, however, if all students are “ready” for the plethora of information that is available for teaching writing. When I taught writing I always enjoyed conferencing with students (grade 4 to college freshmen) to find out what they really wanted to say, or what was challenging them in their writing journey.

I love the way you guide the students with concrete examples. Thanks for sharing this work.

Dear Melanie, This is a beautifully written post that has inspired my preparation as I approach this unit with my 7th graders. I was just getting ready to pull out all of my TC work from last summer and now I am truly inspired. Thank you very much for your efforts!

Like Liked by 1 person

I am curious what grades you have used these with. Thanks. They are very helpful and well-done.

I have used them with grades 4 and 5, but I think they could be used with higher grades as well.

Thanks so much for this lesson. This gives me some great fresh ideas on how to teach this difficult topic! I am trying to build a bank of sample literary essays to share with students. I would like to share with them essays from different pieces of literature than what I am asking them to analyze. I find my student struggle with this type of writing. I would love to have a few models to show them. Does anyone have any quality student samples that they would be willing to share? I teach 7th, 8th, and 10th grades. Thanks!

Comments are closed.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

5th grade nonfiction writing samples

by: Jessica Kelmon | Updated: July 23, 2016

Print article

When it comes to writing, fifth grade is a red-letter year. To prepare for the demands of middle school and high school writing, fifth graders should be mastering skills required for strong nonfiction writing . Learn more about your fifth grader’s writing under Common Core . All students should be learning three styles of writing:

Informative/explanatory writing

Reports that convey information accurately with facts, details, and supporting information.

Narrative writing

Stories, poems, plays, and other types of fiction that convey a plot, character development, and/or personal stories.

Opinion writing

Writing in which students try to convince readers to accept their opinion about something using reasons and examples.

Fifth grade writing sample #1

Bipolar Children

This student’s report starts with a decorative cover and a table of contents. The report has eight sections, each clearly labeled with a bold subhead, and includes a bibliography. At the end, this student adds three visuals, two images from the internet with handwritten captions and a related, hand-drawn cartoon.

Type of writing: Informative/explanatory writing

Fifth grade writing sample #2

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team

Dylan’s report is thorough and well organized. There’s a cover page, an opening statement, and four clear sections with subheads, including a conclusion. You’ll see from the teacher’s note at the end that the assignment is for an opinion piece, but Dylan clearly writes a strong informational/explanatory piece, which is why it’s included here.

Fifth grade writing sample #3

The Harmful Ways of By-Catch and Overfishing

This student includes facts and examples to inform the reader about by-catch and overfishing. Then, at the end, the student tries to convince the reader to take a personal interest in these topics and gives example of how the reader can take action, too.

Type of writing: Opinion writing

See more examples of real kids’ writing in different grades: Kindergarten , first grade , second grade , third grade , fourth grade .

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

6 ways to improve a college essay

Quick writing tips for every age

Writing on the wall

Why parents must teach writing

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

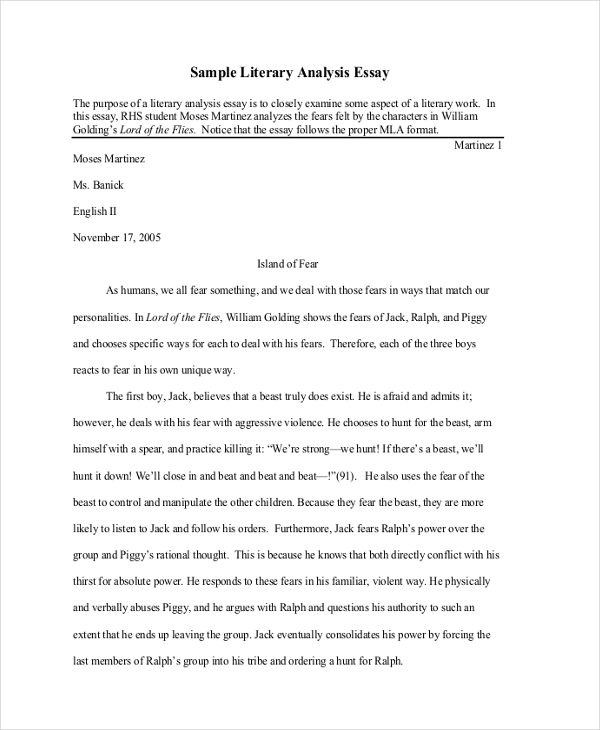

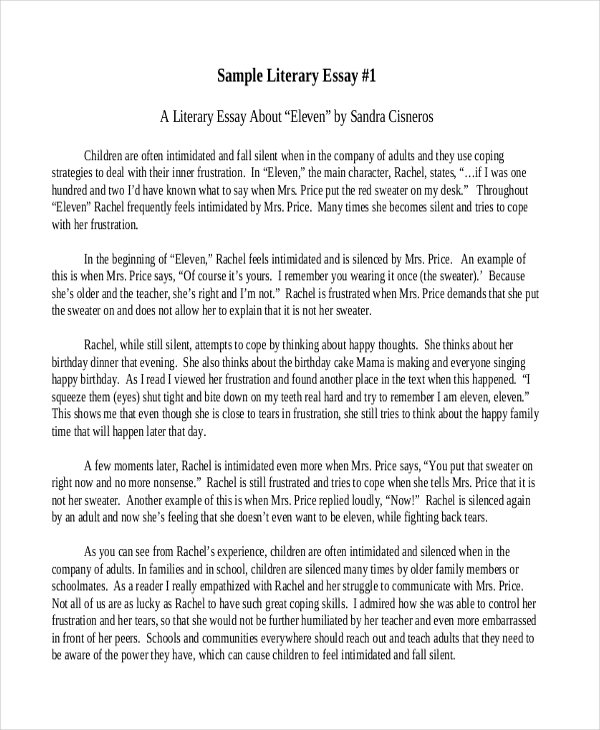

8.15: Sample Student Literary Analysis Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 101141

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The following examples are essays where student writers focused on close-reading a literary work.

While reading these examples, ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the essay's thesis statement, and how do you know it is the thesis statement?

- What is the main idea or topic sentence of each body paragraph, and how does it relate back to the thesis statement?

- Where and how does each essay use evidence (quotes or paraphrase from the literature)?

- What are some of the literary devices or structures the essays analyze or discuss?

- How does each author structure their conclusion, and how does their conclusion differ from their introduction?

Example 1: Poetry

Victoria Morillo

Instructor Heather Ringo

3 August 2022

How Nguyen’s Structure Solidifies the Impact of Sexual Violence in “The Study”

Stripped of innocence, your body taken from you. No matter how much you try to block out the instance in which these two things occurred, memories surface and come back to haunt you. How does a person, a young boy , cope with an event that forever changes his life? Hieu Minh Nguyen deconstructs this very way in which an act of sexual violence affects a survivor. In his poem, “The Study,” the poem's speaker recounts the year in which his molestation took place, describing how his memory filters in and out. Throughout the poem, Nguyen writes in free verse, permitting a structural liberation to become the foundation for his message to shine through. While he moves the readers with this poignant narrative, Nguyen effectively conveys the resulting internal struggles of feeling alone and unseen.

The speaker recalls his experience with such painful memory through the use of specific punctuation choices. Just by looking at the poem, we see that the first period doesn’t appear until line 14. It finally comes after the speaker reveals to his readers the possible, central purpose for writing this poem: the speaker's molestation. In the first half, the poem makes use of commas, em dashes, and colons, which lends itself to the idea of the speaker stringing along all of these details to make sense of this time in his life. If reading the poem following the conventions of punctuation, a sense of urgency is present here, as well. This is exemplified by the lack of periods to finalize a thought; and instead, Nguyen uses other punctuation marks to connect them. Serving as another connector of thoughts, the two em dashes give emphasis to the role memory plays when the speaker discusses how “no one [had] a face” during that time (Nguyen 9-11). He speaks in this urgent manner until the 14th line, and when he finally gets it off his chest, the pace of the poem changes, as does the more frequent use of the period. This stream-of-consciousness-like section when juxtaposed with the latter half of the poem, causes readers to slow down and pay attention to the details. It also splits the poem in two: a section that talks of the fogginess of memory then transitions into one that remembers it all.

In tandem with the fluctuating nature of memory, the utilization of line breaks and word choice help reflect the damage the molestation has had. Within the first couple of lines of the poem, the poem demands the readers’ attention when the line breaks from “floating” to “dead” as the speaker describes his memory of Little Billy (Nguyen 1-4). This line break averts the readers’ expectation of the direction of the narrative and immediately shifts the tone of the poem. The break also speaks to the effect his trauma has ingrained in him and how “[f]or the longest time,” his only memory of that year revolves around an image of a boy’s death. In a way, the speaker sees himself in Little Billy; or perhaps, he’s representative of the tragic death of his boyhood, how the speaker felt so “dead” after enduring such a traumatic experience, even referring to himself as a “ghost” that he tries to evict from his conscience (Nguyen 24). The feeling that a part of him has died is solidified at the very end of the poem when the speaker describes himself as a nine-year-old boy who’s been “fossilized,” forever changed by this act (Nguyen 29). By choosing words associated with permanence and death, the speaker tries to recreate the atmosphere (for which he felt trapped in) in order for readers to understand the loneliness that came as a result of his trauma. With the assistance of line breaks, more attention is drawn to the speaker's words, intensifying their importance, and demanding to be felt by the readers.

Most importantly, the speaker expresses eloquently, and so heartbreakingly, about the effect sexual violence has on a person. Perhaps what seems to be the most frustrating are the people who fail to believe survivors of these types of crimes. This is evident when he describes “how angry” the tenants were when they filled the pool with cement (Nguyen 4). They seem to represent how people in the speaker's life were dismissive of his assault and who viewed his tragedy as a nuisance of some sorts. This sentiment is bookended when he says, “They say, give us details , so I give them my body. / They say, give us proof , so I give them my body,” (Nguyen 25-26). The repetition of these two lines reinforces the feeling many feel in these scenarios, as they’re often left to deal with trying to make people believe them, or to even see them.

It’s important to recognize how the structure of this poem gives the speaker space to express the pain he’s had to carry for so long. As a characteristic of free verse, the poem doesn’t follow any structured rhyme scheme or meter; which in turn, allows him to not have any constraints in telling his story the way he wants to. The speaker has the freedom to display his experience in a way that evades predictability and engenders authenticity of a story very personal to him. As readers, we abandon anticipating the next rhyme, and instead focus our attention to the other ways, like his punctuation or word choice, in which he effectively tells his story. The speaker recognizes that some part of him no longer belongs to himself, but by writing “The Study,” he shows other survivors that they’re not alone and encourages hope that eventually, they will be freed from the shackles of sexual violence.

Works Cited

Nguyen, Hieu Minh. “The Study” Poets.Org. Academy of American Poets, Coffee House Press, 2018, https://poets.org/poem/study-0 .

Example 2: Fiction

Todd Goodwin

Professor Stan Matyshak

Advanced Expository Writing

Sept. 17, 20—

Poe’s “Usher”: A Mirror of the Fall of the House of Humanity

Right from the outset of the grim story, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Edgar Allan Poe enmeshes us in a dark, gloomy, hopeless world, alienating his characters and the reader from any sort of physical or psychological norm where such values as hope and happiness could possibly exist. He fatalistically tells the story of how a man (the narrator) comes from the outside world of hope, religion, and everyday society and tries to bring some kind of redeeming happiness to his boyhood friend, Roderick Usher, who not only has physically and psychologically wasted away but is entrapped in a dilapidated house of ever-looming terror with an emaciated and deranged twin sister. Roderick Usher embodies the wasting away of what once was vibrant and alive, and his house of “insufferable gloom” (273), which contains his morbid sister, seems to mirror or reflect this fear of death and annihilation that he most horribly endures. A close reading of the story reveals that Poe uses mirror images, or reflections, to contribute to the fatalistic theme of “Usher”: each reflection serves to intensify an already prevalent tone of hopelessness, darkness, and fatalism.

It could be argued that the house of Roderick Usher is a “house of mirrors,” whose unpleasant and grim reflections create a dark and hopeless setting. For example, the narrator first approaches “the melancholy house of Usher on a dark and soundless day,” and finds a building which causes him a “sense of insufferable gloom,” which “pervades his spirit and causes an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart, an undiscerned dreariness of thought” (273). The narrator then optimistically states: “I reflected that a mere different arrangement of the scene, of the details of the picture, would be sufficient to modify, or perhaps annihilate its capacity for sorrowful impression” (274). But the narrator then sees the reflection of the house in the tarn and experiences a “shudder even more thrilling than before” (274). Thus the reader begins to realize that the narrator cannot change or stop the impending doom that will befall the house of Usher, and maybe humanity. The story cleverly plays with the word reflection : the narrator sees a physical reflection that leads him to a mental reflection about Usher’s surroundings.

The narrator’s disillusionment by such grim reflection continues in the story. For example, he describes Roderick Usher’s face as distinct with signs of old strength but lost vigor: the remains of what used to be. He describes the house as a once happy and vibrant place, which, like Roderick, lost its vitality. Also, the narrator describes Usher’s hair as growing wild on his rather obtrusive head, which directly mirrors the eerie moss and straw covering the outside of the house. The narrator continually longs to see these bleak reflections as a dream, for he states: “Shaking off from my spirit what must have been a dream, I scanned more narrowly the real aspect of the building” (276). He does not want to face the reality that Usher and his home are doomed to fall, regardless of what he does.

Although there are almost countless examples of these mirror images, two others stand out as important. First, Roderick and his sister, Madeline, are twins. The narrator aptly states just as he and Roderick are entombing Madeline that there is “a striking similitude between brother and sister” (288). Indeed, they are mirror images of each other. Madeline is fading away psychologically and physically, and Roderick is not too far behind! The reflection of “doom” that these two share helps intensify and symbolize the hopelessness of the entire situation; thus, they further develop the fatalistic theme. Second, in the climactic scene where Madeline has been mistakenly entombed alive, there is a pairing of images and sounds as the narrator tries to calm Roderick by reading him a romance story. Events in the story simultaneously unfold with events of the sister escaping her tomb. In the story, the hero breaks out of the coffin. Then, in the story, the dragon’s shriek as he is slain parallels Madeline’s shriek. Finally, the story tells of the clangor of a shield, matched by the sister’s clanging along a metal passageway. As the suspense reaches its climax, Roderick shrieks his last words to his “friend,” the narrator: “Madman! I tell you that she now stands without the door” (296).

Roderick, who slowly falls into insanity, ironically calls the narrator the “Madman.” We are left to reflect on what Poe means by this ironic twist. Poe’s bleak and dark imagery, and his use of mirror reflections, seem only to intensify the hopelessness of “Usher.” We can plausibly conclude that, indeed, the narrator is the “Madman,” for he comes from everyday society, which is a place where hope and faith exist. Poe would probably argue that such a place is opposite to the world of Usher because a world where death is inevitable could not possibly hold such positive values. Therefore, just as Roderick mirrors his sister, the reflection in the tarn mirrors the dilapidation of the house, and the story mirrors the final actions before the death of Usher. “The Fall of the House of Usher” reflects Poe’s view that humanity is hopelessly doomed.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Fall of the House of Usher.” 1839. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library . 1995. Web. 1 July 2012. < http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/PoeFall.html >.

Example 3: Poetry

Amy Chisnell

Professor Laura Neary

Writing and Literature

April 17, 20—

Don’t Listen to the Egg!: A Close Reading of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky”

“You seem very clever at explaining words, Sir,” said Alice. “Would you kindly tell me the meaning of the poem called ‘Jabberwocky’?”

“Let’s hear it,” said Humpty Dumpty. “I can explain all the poems that ever were invented—and a good many that haven’t been invented just yet.” (Carroll 164)

In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass , Humpty Dumpty confidently translates (to a not so confident Alice) the complicated language of the poem “Jabberwocky.” The words of the poem, though nonsense, aptly tell the story of the slaying of the Jabberwock. Upon finding “Jabberwocky” on a table in the looking-glass room, Alice is confused by the strange words. She is quite certain that “ somebody killed something ,” but she does not understand much more than that. When later she encounters Humpty Dumpty, she seizes the opportunity at having the knowledgeable egg interpret—or translate—the poem. Since Humpty Dumpty professes to be able to “make a word work” for him, he is quick to agree. Thus he acts like a New Critic who interprets the poem by performing a close reading of it. Through Humpty’s interpretation of the first stanza, however, we see the poem’s deeper comment concerning the practice of interpreting poetry and literature in general—that strict analytical translation destroys the beauty of a poem. In fact, Humpty Dumpty commits the “heresy of paraphrase,” for he fails to understand that meaning cannot be separated from the form or structure of the literary work.

Of the 71 words found in “Jabberwocky,” 43 have no known meaning. They are simply nonsense. Yet through this nonsensical language, the poem manages not only to tell a story but also gives the reader a sense of setting and characterization. One feels, rather than concretely knows, that the setting is dark, wooded, and frightening. The characters, such as the Jubjub bird, the Bandersnatch, and the doomed Jabberwock, also appear in the reader’s head, even though they will not be found in the local zoo. Even though most of the words are not real, the reader is able to understand what goes on because he or she is given free license to imagine what the words denote and connote. Simply, the poem’s nonsense words are the meaning.

Therefore, when Humpty interprets “Jabberwocky” for Alice, he is not doing her any favors, for he actually misreads the poem. Although the poem in its original is constructed from nonsense words, by the time Humpty is done interpreting it, it truly does not make any sense. The first stanza of the original poem is as follows:

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogroves,

An the mome raths outgrabe. (Carroll 164)

If we replace, however, the nonsense words of “Jabberwocky” with Humpty’s translated words, the effect would be something like this:

’Twas four o’clock in the afternoon, and the lithe and slimy badger-lizard-corkscrew creatures

Did go round and round and make holes in the grass-plot round the sun-dial:

All flimsy and miserable were the shabby-looking birds

with mop feathers,

And the lost green pigs bellowed-sneezed-whistled.

By translating the poem in such a way, Humpty removes the charm or essence—and the beauty, grace, and rhythm—from the poem. The poetry is sacrificed for meaning. Humpty Dumpty commits the heresy of paraphrase. As Cleanth Brooks argues, “The structure of a poem resembles that of a ballet or musical composition. It is a pattern of resolutions and balances and harmonizations” (203). When the poem is left as nonsense, the reader can easily imagine what a “slithy tove” might be, but when Humpty tells us what it is, he takes that imaginative license away from the reader. The beauty (if that is the proper word) of “Jabberwocky” is in not knowing what the words mean, and yet understanding. By translating the poem, Humpty takes that privilege from the reader. In addition, Humpty fails to recognize that meaning cannot be separated from the structure itself: the nonsense poem reflects this literally—it means “nothing” and achieves this meaning by using “nonsense” words.

Furthermore, the nonsense words Carroll chooses to use in “Jabberwocky” have a magical effect upon the reader; the shadowy sound of the words create the atmosphere, which may be described as a trance-like mood. When Alice first reads the poem, she says it seems to fill her head “with ideas.” The strange-sounding words in the original poem do give one ideas. Why is this? Even though the reader has never heard these words before, he or she is instantly aware of the murky, mysterious mood they set. In other words, diction operates not on the denotative level (the dictionary meaning) but on the connotative level (the emotion(s) they evoke). Thus “Jabberwocky” creates a shadowy mood, and the nonsense words are instrumental in creating this mood. Carroll could not have simply used any nonsense words.

For example, let us change the “dark,” “ominous” words of the first stanza to “lighter,” more “comic” words:

’Twas mearly, and the churly pells

Did bimble and ringle in the tink;

All timpy were the brimbledimps,

And the bip plips outlink.

Shifting the sounds of the words from dark to light merely takes a shift in thought. To create a specific mood using nonsense words, one must create new words from old words that convey the desired mood. In “Jabberwocky,” Carroll mixes “slimy,” a grim idea, “lithe,” a pliable image, to get a new adjective: “slithy” (a portmanteau word). In this translation, brighter words were used to get a lighter effect. “Mearly” is a combination of “morning” and “early,” and “ringle” is a blend of “ring” and "dingle.” The point is that “Jabberwocky’s” nonsense words are created specifically to convey this shadowy or mysterious mood and are integral to the “meaning.”

Consequently, Humpty’s rendering of the poem leaves the reader with a completely different feeling than does the original poem, which provided us with a sense of ethereal mystery, of a dark and foreign land with exotic creatures and fantastic settings. The mysteriousness is destroyed by Humpty’s literal paraphrase of the creatures and the setting; by doing so, he has taken the beauty away from the poem in his attempt to understand it. He has committed the heresy of paraphrase: “If we allow ourselves to be misled by it [this heresy], we distort the relation of the poem to its ‘truth’… we split the poem between its ‘form’ and its ‘content’” (Brooks 201). Humpty Dumpty’s ultimate demise might be seen to symbolize the heretical split between form and content: as a literary creation, Humpty Dumpty is an egg, a well-wrought urn of nonsense. His fall from the wall cracks him and separates the contents from the container, and not even all the King’s men can put the scrambled egg back together again!

Through the odd characters of a little girl and a foolish egg, “Jabberwocky” suggests a bit of sage advice about reading poetry, advice that the New Critics built their theories on. The importance lies not solely within strict analytical translation or interpretation, but in the overall effect of the imagery and word choice that evokes a meaning inseparable from those literary devices. As Archibald MacLeish so aptly writes: “A poem should not mean / But be.” Sometimes it takes a little nonsense to show us the sense in something.

Brooks, Cleanth. The Well-Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry . 1942. San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1956. Print.

Carroll, Lewis. Through the Looking-Glass. Alice in Wonderland . 2nd ed. Ed. Donald J. Gray. New York: Norton, 1992. Print.

MacLeish, Archibald. “Ars Poetica.” The Oxford Book of American Poetry . Ed. David Lehman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006. 385–86. Print.

Attribution

- Sample Essay 1 received permission from Victoria Morillo to publish, licensed Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International ( CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 )

- Sample Essays 2 and 3 adapted from Cordell, Ryan and John Pennington. "2.5: Student Sample Papers" from Creating Literary Analysis. 2012. Licensed Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported ( CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 )

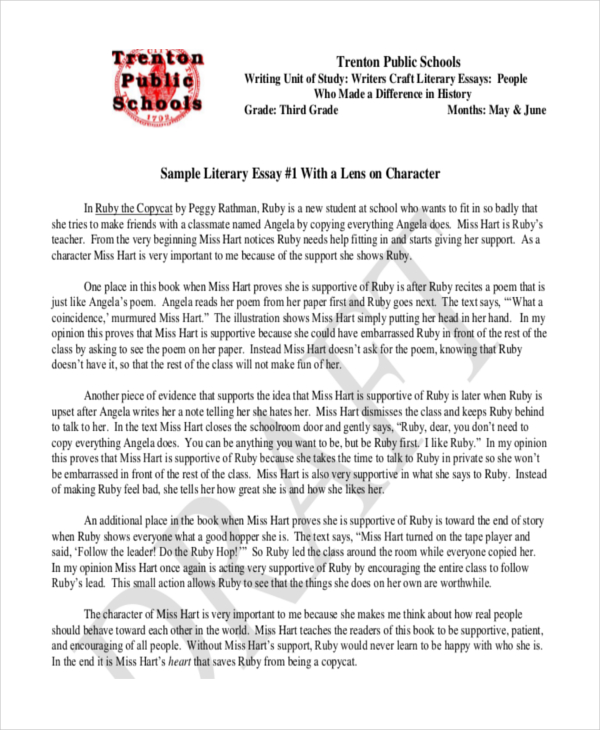

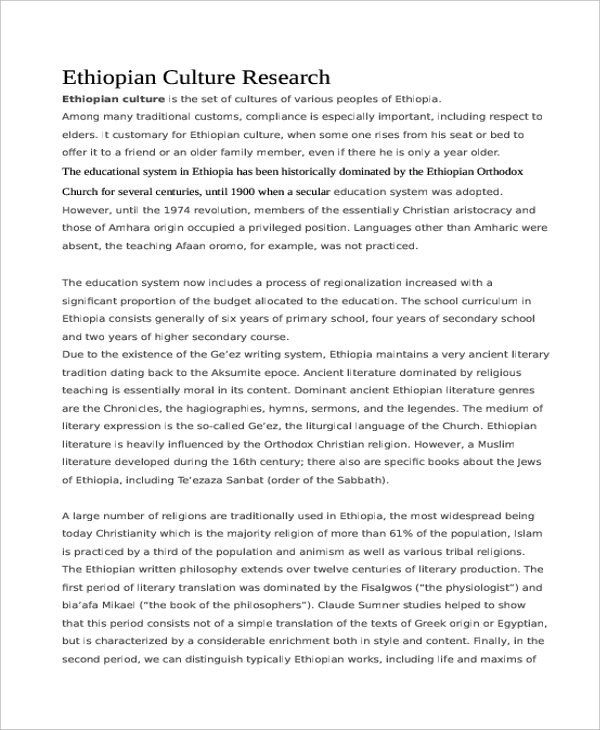

Literary Essay

Part of submissions you give in school are essays. Essay writing is introduced in school is largely due to prepare a student or individual for work which also involves writing essays of sorts. The practice of writing essays also develops critical thinking which is highly needed in any future job.

There are many different elements involved in writing an effective essay . Examples in the page provide further information regarding how an essay is made and formed. Scroll down the page in order to view additional essay samples which may help you in making your own literary essay.

Literary Analysis Essay Outline Template

- Google Docs

Size: 93 KB

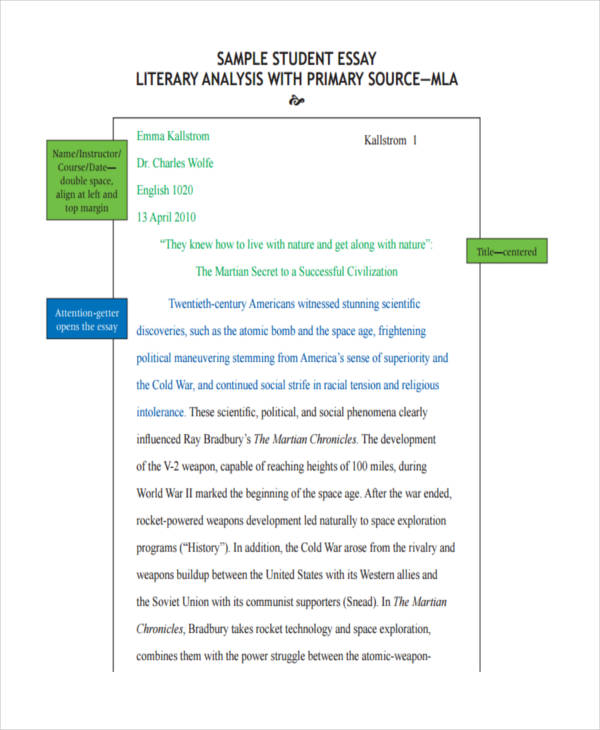

Student Literary Sample

Size: 116 KB

Literary Analysis Example

Size: 63 KB

Formal Literary Sample

Size: 160 KB

How to Write a Literary Essay

In writing a literary essay, it is important to know how to write a essay and take note of the following:

- Make sure you read and understand the plot of the chosen material which includes the characters involved.

- Take note of sections in the material and write down reactions

- Draw a character map or sequential events of the story.

- Review the notes indicated and decide what question you want an answer to regarding the material you have read.

Essay examples in Doc seen on the page give added information on how an essay is structured. Feel free to browse the page and click on any individual download link button below a sample that you like.

What Is the Format for a Literary Essay?

As with all standard formats in literature, a literary essay has basically an introduction, body, and essay conclusion .

- The introduction states the main point of your essay

- The body cites examples that support your thesis

- Conclusion is a summary of main points in relation to your thesis

Short essay examples are shown on the page to help you better understand the basics in writing an essay. These samples are all available for download via the download link button below each sample.

Persuasive Essay Example

Research Literary

Size: 25 KB

Short Literary Sample

Size: 467 KB

Free Literary Essay

Size: 90 KB

What Is the Purpose of a Literary Essay?

Literary essays are often made to convey a message. For students, it is a way to gauge their knowledge of books or stories they read. Sample essay outlines can be seen on the page to provide further information regarding a literary essay and how the components are placed to maintain the structure of an essay.

Guidelines for a Literary Essay

In writing a literary essay, the following guidelines and for content winning essay should help:

- Brainstorm all ideas and write them on a piece of paper and choose which will be best as your topic.

- Develop a sequence to your ideas. Numbering them helps you decide on the order.

- Make a flow chart in connection to the sequence of ideas starting with the introduction, body, and conclusion.

- Arrange each idea in an order which you want to take place in the essay.

- Ensure sequences support the flow of the essay and make the whole link with each other.

- Develop a conclusion which answers the introduction of your essay.

Persuasive writing examples are seen on the page and should help you in the better understanding of a literary essay. All the samples are available for download. Just click on the download link button below a sample to access the file.

Literary Essay Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Write a Literary Essay on the theme of heroism in classic literature.

Discuss the symbolism in "The Great Gatsby" in your Literary Essay.

literary essay 5th grade 5 paragraph essay

All Formats

Resource types, all resource types.

- Rating Count

- Price (Ascending)

- Price (Descending)

- Most Recent

Literary essay 5th grade 5 paragraph essay

5th /6th Grade Comparative Literary Essay Unit

- Word Document File

Baby Literary Essay Analysis Graphic Organizers Templates Writing About Reading

5th Grade Writing Topics and Unit Plans

Sample Five - Paragraph Essays (Middle Grades )

An Example of a Literary Analysis Essay and Unit

4th and 5th Grade Literary Essay Models (Teachers College)

The 5 - Paragraph Essay Rubric

ESSAYS : How to Write Them: A Literary Analysis of a Character Trait

Literary Analysis Essay Mentor Text Pack

Essay with 5 Paragraphs | Unit Plans

Essay Writing Prompts, Organizers, Rubrics *No Prep Printables and Mini-Lessons*

EDITABLE Rubric for Literary Essay Writing based on Lucy Calkins Units of Study

- Google Docs™

Literary Essay Digital Graphic Organizer - 5 paragraph essay

- Google Slides™

Mentor Text: Literary Essay on Jack and the Beanstalk

Literary Essay Graphic Organizer

Basic Literary Essay Scaffold

Grade 5 Reading Street Unit 2 Paired Text Essay

Literary Essay Rubric

RACES Text Evidence Expository Essay Writing: GRADES 4- 5

Writing a Literary Essay

Literary Essay Unit - Writing Unit and Printables

Middle School Book Project: Students Write Each Other Literary Letters!

ESSAY Prompts for EVERY Novel | Digital and Printable

Character Change Paragraph (Responding to Reading Grades 3, 4, 5 )

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

EL Education Curriculum

You are here.

- ELA G5:M1:U2:L15

Writing a Literary Essay: Conclusion

In this lesson, daily learning targets, ongoing assessment.

- Technology and Multimedia

Supporting English Language Learners

Universal design for learning, closing & assessments, you are here:.

- ELA Grade 5

- ELA G5:M1:U2

Like what you see?

Order printed materials, teacher guides and more.

How to order

Help us improve!

Tell us how the curriculum is working in your classroom and send us corrections or suggestions for improving it.

Leave feedback

These are the CCS Standards addressed in this lesson:

- RL.5.1: Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

- RL.5.3: Compare and contrast two or more characters, settings, or events in a story or drama, drawing on specific details in the text (e.g., how characters interact).

- RF.5.4: Read with sufficient accuracy and fluency to support comprehension.

- W.5.2: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas and information clearly.

- W.5.2a: Introduce a topic clearly, provide a general observation and focus, and group related information logically; include formatting (e.g., headings), illustrations, and multimedia when useful to aiding comprehension.

- W.5.2b: Develop the topic with facts, definitions, concrete details, quotations, or other information and examples related to the topic.

- W.5.2e: Provide a concluding statement or section related to the information or explanation presented.

- W.5.4: Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development and organization are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

- W.5.9: Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

- W.5.9a: Apply grade 5 Reading standards to literature (e.g., "Compare and contrast two or more characters, settings, or events in a story or a drama, drawing on specific details in the text [e.g., how characters interact]").

- L.5.1: Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking.

- I can write the conclusion of my essay. ( RL.5.1, RL.5.3, W.5.2a, W.5.2e, W.5.4, W.5.9a )

- Character Reaction Reflections note-catcher ( W.5.2e )

- Conclusion of partner literary essay ( RL.5.1, RL.5.3, W.5.2a, W.5.2e, W.5.4, W.5.9a )

- Organizing the Model: Conclusion Paragraph strips, one per pair, see supporting materials.

- Research reading share (see Independent Reading: Sample Plans).

- Review the Thumb-O-Meter Protocol. See Classroom Protocols.

- Post: Learning targets and applicable anchor charts.

Tech and Multimedia

- Work Time A: Students write their conclusion paragraph on a word-processing document--for example, a Google Doc.

Supports guided in part by CA ELD Standards 5.I.B.6, 5.I.C.10, and 5.II.A.1

Important points in the lesson itself

- The basic design of this lesson supports ELLs with opportunities to work closely with essay structure, building on their understanding one paragraph at a time. In this lesson, students focus exclusively on the conclusions to their literary essays. Students continue to benefit from the color-coding system established in prior lessons for visual support.

- ELLs may find it challenging to immediately apply their new learning about essay structure and write their conclusions within the time allotted. Consider working closely with a small group after working with the class, and support each student as needed. See "Levels of support" for details.

Levels of support

For lighter support:

- During Opening A, consider changing student partnerships so that students with similar proficiency levels are paired together. This will challenge students to work more independently, and it will provide an opportunity to assess the progress they have made.

For heavier support:

- During Work Time A, provide a template with a cloze version of a literary essay conclusion. Reduce the complexity of the task by allowing students who need prompting or who may be overwhelmed by starting from scratch to use a version with prepared sentence starters. For heavier support, provide a near-complete version of the template. Omit only a few words, such as the event and the names of the characters. Students can complete the paragraph as a cloze exercise while focusing on comprehending the paragraph and its purpose within the essay structure. (Example: Although [event] will profoundly change both their lives, [character] and [character] react very differently. [Character 1] is _____, so he or she reacted ______. In contrast, [character 2] is ______ so he or she _____.)

- Multiple Means of Representation (MMR): In this lesson, students write the conclusion to their literary essay. This requires drawing on several tools, such as the Painted Essay(r) template, model literary essay, and Informative Writing Checklist. Whenever possible, use think-alouds and/or peer models to make the thought process explicit. Consider offering a think-aloud to show how you incorporate ideas from the model literary essay into an original paragraph. This way, students will not only see the model visually but will also be able to understand the thought processes behind it.

- Multiple Means of Action and Expression (MMAE): This lesson provides 30 minutes of writing time. Some students may need additional support to build their writing stamina over such a long time period. Support students in building their stamina by providing scaffolds that build an environment that is conducive to writing (see Meeting Students' Needs column).

- Multiple Means of Engagement (MME): Students who need additional support with writing may have negative associations with writing tasks based on previous experiences. Help them feel successful with writing by allowing them to create feasible goals and celebrate when these goals are met. For instance, place a sticker or a star at a specific point on the page (e.g., two pages) that provides a visual writing target for the day. Also, construct goals for sustained writing by chunking the 25-minute writing block into smaller pieces. Provide choice for a break activity at specific time points when students have demonstrated writing progress. Celebrate students who meet their writing goals, whether it is the length of the text or sustained writing time.

Key: Lesson-Specific Vocabulary (L); Text-Specific Vocabulary (T); Vocabulary Used in Writing (W)

- conclusion, restate (L)

- Organizing the Model: Conclusion Paragraph strips (one part per pair)

- Painted Essay(r) template (from Lesson 12; one per student)

- Model literary essay (from Lesson 12; one per student and one for display)

- Literary Essay anchor chart (begun in Lesson 13; added to during Opening A; see supporting materials)

- Literary Essay anchor chart (example, for teacher reference)

- Literary essay prompt (from Lesson 12; one per student)

- Working to Become Effective Learners anchor chart (begun in Lesson 13)

- Informative Writing Checklist (from Lesson 13; one per student and one to display)

- Informative Writing Checklist (example, for teacher reference)

- Affix List (from Unit 1, Lesson 4; one per student)

- Vocabulary logs (from Unit 1, Lesson 4; one per student)

- Academic Word Wall (begun in Unit 1, Lesson 1)

- Character Reaction Reflections note-catcher (new; one per student and one to display)

- Character Reaction Reflections note-catcher (example, for teacher reference)

- Esperanza Rising (from Unit 1, Lesson 2; one per student)

- Domain-Specific Word Wall (begun in Unit 1, Lesson 3)

- Working to Become Ethical People anchor chart (begun in Unit 1, Lesson 2)

- Independent Reading: Sample Plans ( see the Tools page ; for teacher reference)

Each unit in the 3-5 Language Arts Curriculum has two standards-based assessments built in, one mid-unit assessment and one end of unit assessment. The module concludes with a performance task at the end of Unit 3 to synthesize their understanding of what they accomplished through supported, standards-based writing.

Copyright © 2013-2024 by EL Education, New York, NY.

Get updates about our new K-5 curriculum as new materials and tools debut.

Help us improve our curriculum..

Tell us what’s going well, share your concerns and feedback.

Terms of use . To learn more about EL Education, visit eleducation.org

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Lucy Calkins: Literary Essays Texts: Whole Group Classroom Short Texts for Modeling: (writing inside the story, close reading, characters, ... She also beat this girl, a fifth-grader named Yolanda, and asked her to join their group. They proceeded to more matches and more wins, and soon there was a crowd of people ...

2017 Released Items: Grade 5 Literary Analysis Task The Literary Analysis Task requires students to read two literary texts that are purposely paired. Students read the texts, answer questions for each text and for the texts as a pair, and then write an analytic essay. The 2017 blueprint for PARCC's grade 5 Literary Analysis Task

Wyoming Department of Education. 122 W. 25th St., Ste. E200 | Cheyenne, WY 82002 P: 307-777-7675 | F: 307-777-6234 | edu.wyoming.gov. The WY-TOPP ELA test has a Writing portion for grades 3, 5, 7, and 9. Each writing test contains one or more passages that relate to a prompt.

W.5.9a: Apply grade 5 Reading standards to literature (e.g., "Compare and contrast two or more characters, settings, or events in a story or a drama, drawing on specific details in the text ... Refer to Literary Essay anchor chart (example, for teacher reference) as necessary.

2018 Released Items: Grade 5 Literary Analysis Task The Literary Analysis Task requires students to read two literary texts that are purposely paired. Students read the texts, answer questions for each text and for the texts as a pair, and then write an analytic essay.

W.5.9a: Apply grade 5 Reading standards to literature (e.g., "Compare and contrast two or more characters, settings, ... Model and think aloud the process of revising the paragraph to meet the criteria for a proof paragraph on the Literary Essay anchor chart. (Example: "I am writing about Esperanza's and Mama's reactions to the camp conditions ...

A. Engaging the Reader: Model Literary Essay (10 minutes) Distribute and display the literary essay prompt and select a volunteer to read it aloud for the group. Tell students that for the rest of this unit, they will be writing an essay to respond to this prompt. Invite students to turn and talk to an elbow partner.

Literary Essays: Setting the Stage. Monday January 8, 2018Monday January 8, 2018 Melanie Meehan. As part my MFA program, I've had to write eight page papers on a paragraph or two of text. That's a lot of words about not too many words. I've also watched my daughters draft critical analyses on literary works in both high school and college.

With fan fiction writing exercises, book poster drawing pages, and more, fifth grade literary analysis worksheets make reading a breeze. Practice these educator-inspired sheets with your child at home for better literacy results. Fifth grade literary analysis worksheets help your ten- or eleven-year-old study prose and poems.

Fifth grade writing sample #1. Bipolar Children. This student's report starts with a decorative cover and a table of contents. The report has eight sections, each clearly labeled with a bold subhead, and includes a bibliography. At the end, this student adds three visuals, two images from the internet with handwritten captions and a related ...

My student's ELA proficiency scores increased 45% in one year and almost 70% in just two years. Those are not typos. >> CLICK HERE << to download the FREE Literary Analysis Reference Booklet. I broke down each area of teaching literary analysis in middle school into lessons, chunks, chart papers, reference materials, and examples.

Grade 5 - Unit 4 Writing - Literary Essay: Proving Your Interpretation of a Character Unit Focus Students will do the heavy lifting work of rehearsing and revising interpretations of literature in their social issues book clubs. Using the theories that students developed in book clubs using a variety of text they will write literary essays.

W.5.9: Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research. W.5.9a: Apply grade 5 Reading standards to literature (e.g., "Compare and contrast two or more characters, settings, or events in a story or a drama, drawing on specific details in the text [e.g., how characters interact]").

Fifth grade essay writing worksheets help your kid write academic and moving essays. Fifth grade essay writing worksheets focus on writing structure and more. ... Response to Literature ... Students will look at a sample essay and try to pick out the kind of details and big ideas that make an informative essay tick. 5th grade.

In this video students learn how to write a literary essay by stating a claim about the theme or a character in the book and providing three reasons. An simp...

Kerri Trucano. 5th & 6th Grade Comparative Literary Essay Units that are aligned to the common core & the PARCC assessment. Materials Included: 1. 5th Grade Unit Plan 2. 6th Grade Unit Plan 3. 5th Grade Comparing Stories Graphic Organizer 4. 6th Grade Comparing Stories Graphic Organizer 5. Creating a Thesis Graphic Organizer 6.

Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap. City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative. Table of contents. Example 1: Poetry. Example 2: Fiction. Example 3: Poetry. Attribution. The following examples are essays where student writers focused on close-reading a literary work.

W.5.9: Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research. W.5.9a: Apply grade 5 Reading standards to literature (e.g., "Compare and contrast two or more characters, settings, or events in a story or a drama, drawing on specific details in the text [e.g., how characters interact]").

• To provide benchmarks against which to determine student progress relative to grade level content standards, and • To promote professional dialogue. Notes of Caution The benchmark writing samples and commentaries represent a work in progress. Currently, a single example is provided for most writing applications. A single example is, clearly,

In writing a literary essay, the following guidelines and for content winning essay should help: Brainstorm all ideas and write them on a piece of paper and choose which will be best as your topic. Develop a sequence to your ideas. Numbering them helps you decide on the order. Make a flow chart in connection to the sequence of ideas starting ...

B. Engaging the Reader: Model Essay (5 minutes) 2. Work Time. A. Reading for Gist and Analyzing the Model Essay: The Painted Essay (20 minutes) B. Planning a Literary Analysis Essay: Selecting a Focus Statement and Quotes (20 minutes) 3. Closing and Assessment. A. Reading Fluency: The Most Beautiful Roof in the World, Page 28 (10 minutes) 4.

5th & 6th Grade Comparative Literary Essay Units that are aligned to the common core & the PARCC assessment. ... These examples of 5 paragraph essay writing are perfect for introducing a unit on descriptive, literary, persuasive (opinion), and informational writing in upper elementary. Teaching How to Write An Essay with 5 ParagraphsEach essay ...

W.5.9a: Apply grade 5 Reading standards to literature (e.g., "Compare and contrast two or more characters, settings, or events in a story or a drama, drawing on specific details in the text ... Refer to Literary Essay anchor chart (example, for teacher reference) as necessary.