An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

In Crisis? Call or Text 988

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Page title The Consequences of Underage Drinking

Download The Consequences of Underage Drinking in English (PDF | 180 KB)

Download The Consequences of Underage Drinking in Spanish (PDF | 57.2 KB)

Children who drink alcohol are more likely to:

Frequent binge drinkers (nearly 1 million high school students nationwide) are more likely to engage in risky behaviors, including using other drugs such as marijuana and cocaine.

Get bad grades

Children who use alcohol have higher rates of academic problems and poor school performance compared with nondrinkers.

Suffer injury or death

In 2009, an estimated 1,844 homicides; 949,400 nonfatal violent crimes such as rape, robbery, and assault; and 1,811,300 property crimes, including burglary, larceny, and car theft were attributed to underage drinking.

Engage in risky sexual activity

Young people who use alcohol are more likely to be sexually active at earlier ages, to have sexual intercourse more often, and to have unprotected sex.

Make bad decisions

Drinking lowers inhibitions and increases the chances that children will engage in risky behavior or do something that they will regret when they are sober.

Have health problems

Young people who drink are more likely to have health issues such as depression and anxiety disorders.

Last Updated: 04/14/2022

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

NIAAA Video Bank

Presentations and Educational Videos from NIAAA

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)

Short takes with niaaa: what are the dangers of underage drinking.

February 15, 2024

niaaa.nih.gov

An official website of the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Helping Someone with a Drinking Problem

Help for parents of troubled teens, parent’s guide to teen depression, choosing an alcohol rehab treatment program, staying social when you quit drinking.

- Vaping: The Health Risks and How to Quit

Women and Alcohol

- Binge Drinking: Effects, Causes, and Help

- Online Therapy: Is it Right for You?

- Mental Health

- Health & Wellness

- Children & Family

- Relationships

Are you or someone you know in crisis?

- Bipolar Disorder

- Eating Disorders

- Grief & Loss

- Personality Disorders

- PTSD & Trauma

- Schizophrenia

- Therapy & Medication

- Exercise & Fitness

- Healthy Eating

- Well-being & Happiness

- Weight Loss

- Work & Career

- Illness & Disability

- Heart Health

- Childhood Issues

- Learning Disabilities

- Family Caregiving

- Teen Issues

- Communication

- Emotional Intelligence

- Love & Friendship

- Domestic Abuse

- Healthy Aging

- Aging Issues

- Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia

- Senior Housing

- End of Life

- Meet Our Team

The dangers of underage drinking

Why kids and teens drink, how to talk to your teen about alcohol, helping a teen who’s already drinking, binge drinking and alcohol poisoning, if you’re a teen with a problem, underage drinking and teen alcohol use.

It’s normal for parents to worry about their children using alcohol. But there are ways to help your teen cope with the pressures to drink and make better choices.

Reviewed by Jeff Sounalath, MS, LPC, LCDC, NCC , an Austin-based counselor at ADHD Advisor specializing in integrated behavioral healthcare, addictions, and multicultural counseling

If you’ve discovered your child or teen is drinking alcohol, it’s normal to feel upset, angry, and worried. Underage drinking can have serious implications that may not show up until later in your child’s life. Using alcohol at a young age can impact how a teen’s brain develops, disrupt their sleeping patterns, delay puberty, make it harder to concentrate at school, and even increase their risk for liver and heart disease, high blood pressure, and certain types of cancer.

On top of that, there are also emotional and behavioral consequences to underage drinking. Alcohol use can affect a teen’s mood and personality, trigger depression, anxiety, or suicidal thoughts/ideation, and lead to an increase in risky behavior such as driving while impaired, having unprotected sex, fighting, stealing, or skipping school.

Kids and teens are more likely to binge drink and are more vulnerable to developing a problem with alcohol than adults. Experts believe this may be because the pleasure center of a teen’s brain matures before their capacity to make sound decisions. In other words, they’re able to experience ”pleasurable” effects from alcohol (such as suppressing anxiety or improving mood) before they’re able to make the right choices about when and how much to drink. This can lead them to do things that are embarrassing, dangerous, or even life-threatening to themselves or others.

While parenting an adolescent is rarely easy, it’s important to remember that you can still have a major impact on the choices your child makes, especially during their preteen and early teen years. With these guidelines can help you identify the best ways to talk to your child about alcohol, address potential underlying problems that may be triggering their alcohol use, and help them to make smarter choices in the future.

The adolescent years can be a time of great upheaval. The physical and hormonal changes can create emotional ups and downs as kids struggle to assert their independence and establish their own identities. According to United States government statistics, by age 15, nearly 30% of kids have had at least one drink, and by age 18, that figure leaps to almost 60%. Similar patterns are reported in other countries.

While many teens will try alcohol at some point out of curiosity or as an act of rebellion or defiance , there is rarely just a single reason why some decide to drink. The more you understand about potential reasons for underage alcohol use, the easier it can be to talk to your child about the dangers and identify any red flags in their behavior.

Common reasons why teens drink include:

Peer pressure . This is among the most common reasons for underage drinking. As kids enter their teens, friends exert more and more influence over the choices they make. Desperate to fit in and be accepted, kids are much more likely to drink when their friends drink. One major sign of underage drinking that you as a parent can look for is a sudden change in peer group. It may be that their new friends are encouraging this negative behavior.

Environmental influences . Films and TV can make it seem that every “cool”, independent teenager drinks. Alcohol advertising also focuses on positive experiences with alcohol, selling their brands as desirable lifestyle choices. Social media, in particular, can make your child feel like they’re missing out by not drinking or cause them to feel inadequate about how they live their life. You can help by educating your child on how social media portrays a distorted, glamorized snapshot of only the positives in a person’s life, rather than a realistic view that includes their daily struggles, such as unhealthy alcohol use.

To cope with an underlying problem. The teen years are tough and kids may turn to alcohol in a misguided attempt to cope with problems such as stress, boredom, the pressure of schoolwork, not fitting in, problems at home, or mental health issues such as anxiety , childhood trauma, ADHD, or depression. Since alcohol is a depressant, using it to self-medicate can make problems even worse. If your child is regularly drinking on their own or drinking during the day it could be they’re struggling to cope with a serious underlying issue. You can help by fostering a relationship with your child where they feel that they can be open and honest with you, rather than being immediately disciplined.

To appear older, more independent . Teens often want to prove that they’re no longer kids. So, if drinking is exclusively for adults only, that’s what they’ll do. They may also copy your own drinking habits to establish their maturity. Remember that as a parent, your child is much more likely to mimic your actions than listen to your words. No matter how much you preach about the dangers of underage drinking, if you reach for a drink to unwind at the end of a stressful day, your teen may be tempted to follow your example. If you have concerns about your child’s alcohol use, you may want to reevaluate and make changes to your own drinking habits as well.

They lack parental boundaries . No matter how tall or mature your teen seems, they need boundaries, discipline, and structure as much as ever. While your rules won’t be the same or as rigid as when they were younger, having loose boundaries can be confusing and overwhelming for a teen. While you can expect a teen to test any boundaries, be clear on what is and isn’t acceptable behavior and what the consequences are for breaking your rules.

As most parents know all too well, talking to a teen is rarely easy. You can feel discouraged when your attempts to communicate are greeted by a sullen roll of the eyes, an incoherent grunt, or the slamming of a door. Or you may despair at the relentless anger or indifference your teen displays towards you. However, if you feel that your child will be exposed to underage drinking, finding a way to talk to them about alcohol can be crucial in either preventing them from starting or curbing any existing alcohol use.

Studies have shown that the earlier your child uses alcohol, the more problems they’re likely to experience later in life, so it’s never too early to start the conversation. It can even be easier to have these conversations early on in your child’s adolescent years, when they aren’t as rebellious and are less likely to be have already been exposed to underage drinking.

The following strategies can help you open the lines of communication with an adolescent without sparking more conflict:

Choose the right time . Trying to talk to a teen about drinking when they’re watching their favorite show, texting with their friends, or in the midst of a heated argument with you about something else isn’t going to be productive. Choose a time when your teen hasn’t been drinking and you’re both calm and focused—and turn off your phone to avoid distractions.

Find common ground . Attempting to dive straight in to a discussion about drinking may be a quick way to trigger an unpleasant fight. A better tactic is to find an area of common ground, such as sports or movies. Once you’re able to peacefully discuss a common interest, it may be easier to get your teen talking about the more sensitive issue of alcohol use.

Make it a conversation rather than a lecture . Allow your teen to talk and open up about their thoughts and opinions, and try to listen without being critical, disapproving, or judgmental. They want to feel heard and understood, so even when you don’t like or agree with what they’re saying, it’s important to withhold blame and criticism. This style of passive parenting, centered on support, non-judgement, and unconditional love, still allows you to appropriately discipline your child. But it can help your child feel that you are coming from a place of love and concern, rather than anger.

Discuss the benefits of not drinking . Teenagers often feel invincible—that nothing bad will ever happen to them—so preaching about the long-term health dangers of underage drinking may fail to discourage them from using alcohol. Instead, talk to your teen about the effects drinking can have on their appearance—bad breath, bad skin, and weight gain from all the empty calories and carbs. You can also talk about how drinking makes people do embarrassing things, like peeing themselves or throwing up.

Emphasize the message about drinking and driving . If your teen goes to a party and chooses to have a drink, it’s a mistake that can be rectified. If they drink and then drive or get into a vehicle driven by someone else who’s been drinking, that mistake could be a fatal one—for them or someone else. Ensure they always have access to an alternative means of getting home, whether that’s a taxi, a ride share service, or calling you, an older sibling, or another adult to pick them up.

Keep the conversation going . Talking to your teen about drinking is not a single task to tick off your to-do list, but rather an ongoing discussion. Things can change quickly in a teenager’s life, so keep making the time to talk about what’s going on with them, keep asking questions, and keep setting a good example for responsible alcohol use.

Plan ways to help your child handle peer pressure

As a teenager, your child is likely to be in social situations where they’re offered alcohol—at parties or in the homes of friends, for example. When all their peers are drinking, it can be hard for anyone to say “no.” While fitting in and being socially accepted are extremely important to teens, you can still help them find ways to decline alcohol without feeling left out.

Working on developing boundaries and the ability to say no in uncomfortable situations can help your child deal with peer pressure and resist the need to drink.

- Suggest reasons they can use to explain why they’re not drinking, such as “I don’t like drinking,” “I have homework to finish,” “I have to be up early for a game,” “My parents are picking me up,” or, “I’ll get grounded if I’m caught drinking again.”

- Teach them to only accept a beverage when they know exactly what’s in it.

- Make sure they have an exit strategy if they feel uncomfortable in a situation where people are drinking alcohol. That could involve a signal they make to a friend, a prepared excuse they have for leaving, or a text they send to you.

- Encourage them to have alternate plans, like going to the movies or watching a game, so they’re less tempted to spend all night in a drinking environment.

As disturbing as it can be to find out that your child or teen has been drinking, it’s important to remember that many teens try alcohol at some point, but that doesn’t mean they automatically have an abuse problem. Your goal should be to discourage further drinking and encourage better decision-making in the future.

It’s important to remain calm when confronting your teen, and only do so when everyone is sober. Explain your concerns and make it clear that your fears come from a place of love. Your child needs to feel you are supportive and that they can confide in you, since underage drinking is often triggered by other problem areas in their life.

Get to know your teen’s friends—and their parents . If their friends drink, your teen is more likely to as well, so it’s important you know where your teen goes and who they hang out with. By getting to know their friends, you can help to identify and discourage negative influences. And by working with their friends’ parents, you can share the responsibility of monitoring their behavior. Similarly, if your teen is spending too much time alone, that may be a red flag that they’re having trouble fitting in.

Monitor your teen’s activity . Keep any alcohol in your home locked away and routinely check potential hiding places your teen may have for alcohol, such as under the bed, between clothes in a drawer, or in a backpack. Explain to your teen that this lack of privacy is a consequence of having been caught using alcohol.

Talk to your teen about underlying issues . Kids face a huge amount of stress as they navigate the teenage years. Many turn to alcohol to relieve stress, cope with the pressures of school, to deal with major life changes, like a move or divorce, or to self-medicate a mental health issue such as anxiety or depression. Talk to your child about what’s going on in their life and any issues that may have prompted their alcohol use.

Lay down rules and consequences . Remind your teen that underage drinking is illegal and that they can be arrested for it. Your teen should also understand that drinking alcohol comes with specific consequences. Agree on rules and punishments ahead of time and stick to them—just don’t make hollow threats or set rules you cannot enforce. Make sure your spouse agrees with the rules and is also prepared to enforce them.

Encourage other interests and social activities . Some kids drink alone or with friends to alleviate boredom; others drink to gain confidence, especially in social situations . You can help by exposing your teen to healthy hobbies and activities, such as team sports, Scouts, and after-school clubs. Encouraging healthy interests and activities can help to boost their self-esteem and build resilience , qualities that make teens less likely to develop problems with alcohol.

[Read: Staying Social When You Quit Drinking]

Get outside help . You don’t have to tackle this problem alone. Teenagers often rebel against their parents but if they hear the same information from a different authority figure, they may be more inclined to listen. Try seeking help from a sports coach, family doctor, therapist , or counselor.

If your teen has an alcohol use disorder

You’ve found bottles of alcohol hidden in your child’s room and regularly smelled alcohol on their breath. You’ve noted the steep drop-off in their schoolwork, abrupt changes in their behavior, and the loss of interest in their former hobbies and interests. Spotting these signs may indicate your child is abusing alcohol.

Witnessing your child struggle with a drinking problem (also known as “alcohol use disorder”) can be as heartbreaking as it is frustrating. Your teen may be falling behind at school, disrupting family life, and even stealing money to finance their habit or getting into legal difficulties. But you’re not alone in your struggle. Drinking problems affect families all over the world from every different background.

While you can’t do the hard work of overcoming a drinking problem for your child, your patience, love, and support can play a crucial part in their long-term recovery. For more, see: Helping Someone with a Drinking Problem .

Speak to a Licensed Therapist

BetterHelp is an online therapy service that matches you to licensed, accredited therapists who can help with depression, anxiety, relationships, and more. Take the assessment and get matched with a therapist in as little as 48 hours.

Binge drinking is defined as drinking so much within a short space of time (about two hours) that blood alcohol levels reach the legal limit of intoxication. For kids and teens, that usually means having three or more drinks at one sitting. Young people who binge drink are more likely to miss classes at school, fall behind with their schoolwork, damage property, sustain an injury, or become victims of assault.

Because the adolescent years are a time of development, teens’ bodies are less able to process alcohol. That means they have a tendency to get drunk quicker and stay drunk longer than older drinkers.

Also, since underage drinkers haven’t yet learned their limits with alcohol, they’re at far greater risk of drinking more than their bodies can handle, resulting in an alcohol overdose or alcohol poisoning when they binge drink. Mixing drinks, doing shots, playing drinking games, and natural teenage impulsiveness can all contribute to binge drinking and increase a young person’s risk for alcohol poisoning.

[Read: Binge Drinking: Effects, Causes, and Help]

Alcohol poisoning can cause vomiting, confusion, impaired judgment, slow or irregular breathing, loss of consciousness, a drop in body temperature and blood sugar level, and even seizures or death.

What to do if your child develops alcohol poisoning

It can be extremely distressing as a parent to witness the after-effects of your teen’s binge drinking. If your teen is in an unconscious or semiconscious state, their breathing is very slow, their skin clammy, and there’s a powerful odor of alcohol, there’s a strong chance they may have alcohol poisoning.

- Don’t leave them alone to “sleep it off.”

- Turn your child onto their side to avoid them choking if they vomit.

- Call your country’s emergency services number (911 in the U.S.) and wait with them for medical help to arrive.

The teen years don’t last forever

When your teen abuses alcohol, it’s easy to judge yourself or negatively compare your family to others. But it’s worth remembering that the teen years don’t last forever. With your guidance and support, your child can learn to resist the allure of underage drinking and, if they later choose to do so, develop a healthy, responsible relationship with alcohol when they reach adulthood.

If you’re a child or teen and are worried about your own or a friend’s drinking, it’s important to reach out to an adult you trust. If you don’t feel you can talk to a parent, reach out to a family friend, older sibling, or school counselor, for example, or call one of the helplines listed below.

Acknowledging you have a problem with alcohol is not a sign of weakness or some kind of character defect. In fact, it takes tremendous strength and courage to admit your problem and decide to face up to it. The teenage years can often be challenging and stressful, and it’s not unusual for people to turn to alcohol as a way of coping with their issues. But whatever difficulties you’re facing at the moment, there is help available and there are healthier, more effective ways of resolving them. The first step is to reach out.

Call SAMHSA’s National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357.

Call Drinkline at 0300 123 1110, visit Drinkaware .

Download Finding Quality Addiction Care in Canada for regional helplines.

Call the Family Drug Helpline at 1300 660 068.

More Information

- Kids and Alcohol - How to talk to your kids about alcohol, from preschoolers to teenagers. (KidsHealth)

- Alcohol Poisoning - How to recognize the signs and help someone. (Mayo Clinic)

- Talk. They Hear You - Articles, videos and other resources to help parents deal with underage drinking. (SAMHSA)

- Underage Drinking - Articles providing tips on preventing underage drinking, talking to your child, and recognizing problems. (Drinkaware)

- Soberful - Practical method for developing and maintaining an alcohol-free lifestyle from a HelpGuide affiliate . (Sounds True)

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders. (2013). In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . American Psychiatric Association. Link

- “Underage Drinking-Why Do Adolescents Drink, What Are the Risks, and How Can Underage Drinking Be Prevented?” Accessed July 15, 2021. Link

- “Section 2 PE Tables – Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, SAMHSA, CBHSQ.” Accessed July 15, 2021. Link

- Schilling, Elizabeth A., Robert H. Aseltine, Jaime L. Glanovsky, Amy James, and Douglas Jacobs. “Adolescent Alcohol Use, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicide Attempts.” The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 44, no. 4 (April 2009): 335–41. Link

- Miller, Jacqueline W., Timothy S. Naimi, Robert D. Brewer, and Sherry Everett Jones. “Binge Drinking and Associated Health Risk Behaviors among High School Students.” Pediatrics 119, no. 1 (January 2007): 76–85. Link

- Lopez-Quintero, Catalina, José Pérez de los Cobos, Deborah S. Hasin, Mayumi Okuda, Shuai Wang, Bridget F. Grant, and Carlos Blanco. “Probability and Predictors of Transition from First Use to Dependence on Nicotine, Alcohol, Cannabis, and Cocaine: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC).” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 115, no. 1–2 (May 1, 2011): 120–30. Link

- “Publications | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism | Measuring the Burden — Alcohol’s Evolving Impact on Individuals, Families, and Society.” Accessed July 15, 2021. Link

- Windle, Michael. “Substance Use, Risky Behaviors, and Victimization among a US National Adolescent Sample.” Addiction 89, no. 2 (1994): 175–82. Link

- “Youth Drinking: Risk Factors and Consequences – Alcohol Alert No. 37-1997.” Accessed July 15, 2021. Link

- Chung, Tammy, and Kristina M. Jackson. “Adolescent Alcohol Use.” In The Oxford Handbook of Adolescent Substance Abuse, by Tammy Chung and Kristina M. Jackson, 130–68. edited by Robert A. Zucker and Sandra A. Brown. Oxford University Press, 2019. Link

- “Early Drinking Linked to Higher Lifetime Alcoholism Risk | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).” Accessed March 7, 2024. Link

More in Addiction

Tips for helping a loved one get sober

Dealing with anger, violence, delinquency, and other behaviors

Recognizing the signs and symptoms, and helping your child

A guide to alcohol addiction treatment services

Cutting down on alcohol doesn’t have to mean losing your social life

The health risks in young people and how to quit

The hidden risks of drinking

Binge Drinking

Help if you have trouble stopping drinking once you start

Professional therapy, done online

BetterHelp makes starting therapy easy. Take the assessment and get matched with a professional, licensed therapist.

Help us help others

Millions of readers rely on HelpGuide.org for free, evidence-based resources to understand and navigate mental health challenges. Please donate today to help us save, support, and change lives.

Age 21 Minimum Legal Drinking Age

A minimum legal drinking age (mlda) of 21 saves lives and protects health.

Minimum Legal Drinking Age (MLDA) laws specify the legal age when an individual can purchase alcoholic beverages. The MLDA in the United States is 21 years. However, prior to the enactment of the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984, the legal age when alcohol could be purchased varied from state to state. 1

An age 21 MLDA is recommended by the:

• American Academy of Pediatrics 2 • Community Preventive Services Task Force 4 • Mothers Against Drunk Driving 5 • National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 1 • National Prevention Council 8 • National Academy of Sciences (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine) 9

The age 21 MLDA saves lives and improves health. 3

Fewer motor vehicle crashes

- States that increased the legal drinking age to 21 saw a 16% median decline in motor vehicle crashes. 6

Decreased drinking

- After all states adopted an age 21 MLDA, drinking during the previous month among persons aged 18 to 20 years declined from 59% in 1985 to 40% in 1991. 7

- Drinking among people aged 21 to 25 also declined significantly when states adopted the age 21 MLDA, from 70% in 1985 to 56% in 1991. 7

Other outcomes

- There is also evidence that the age 21 MLDA protects drinkers from alcohol and other drug dependence, adverse birth outcomes, and suicide and homicide. 4

Drinking by those under the age 21 is a public health problem.

- Excessive drinking contributes to about 4,000 deaths among people below the age of 21 in the U.S. each year. 10

- Underage drinking cost the U.S. economy $24 billion in 2010. 11

Drinking by those below the age of 21 is also strongly linked with 9,12,13 :

- Death from alcohol poisoning.

- Unintentional injuries, such as car crashes, falls, burns, and drowning.

- Suicide and violence, such as fighting and sexual assault.

- Changes in brain development.

- School performance problems, such as higher absenteeism and poor or failing grades.

- Alcohol dependence later in life.

- Other risk behaviors such as smoking, drug misuse, and risky sexual behaviors.

Alcohol-impaired driving

Drinking by those below the age of 21 is strongly associated with alcohol-impaired driving. The 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey 14 found that among high school students, during the past 30 days

- 5% drove after drinking alcohol.

- 14% rode with a driver who had been drinking alcohol.

Rates of drinking and binge drinking among those under 21

The 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System found that among high school students, 23% drank alcohol and 11% binge drank during the past 30 days. 14

In 2021, the Monitoring the Future Survey reported that 6% of 8th graders and 28% of 12th graders drank alcohol during the past 30 days, and 2% of 8th graders and 13% of 12th graders binge drank during the past 2 weeks. 15

In 2014, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the New York State Liquor Authority found that more than half (58%) of the licensed alcohol retailers in the City sold alcohol to underage decoys. 17

Enforcing the age 21 MLDA

Communities can enhance the effectiveness of age 21 MLDA laws by actively enforcing them.

- A Community Guide review found that enhanced enforcement of laws prohibiting alcohol sales to minors reduced the ability of youthful-looking decoys to purchase alcoholic beverages by a median of 42%. 16

- Alcohol sales to minors are still a common problem in communities.

More information on underage drinking

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Determine Why There Are Fewer Young Alcohol Impaired Drivers External . Washington, DC. 2001.

- Committee on Substance Abuse, Kokotailo PK. Alcohol use by youth and adolescents: a pediatric concern External . Pediatrics . 2010;125(5):1078-1087.

- DeJong W, Blanchette J. Case closed: research evidence on the positive public health impact of the age 21 minimum legal drinking age in the United States External . J Stud Alcohol Drugs . 2014;75 Suppl 17:108-115.

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Recommendations to reduce injuries to motor vehicle occupants: increasing child safety seat use, increasing safety belt use, and reducing alcohol-impaired driving Cdc-pdf External [PDF-78 KB]. Am J Prev Med . 2001;21(4 Suppl):16-22.

- Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD). Why 21? 2018; https://www.madd.org/the-solution/teen-drinking-prevention/why-21/ External . Accessed May 3, 2018.

- Shults RA, Elder RW, Sleet DA, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce alcohol-impaired driving Cdc-pdf External [PDF-2 MB]. Am J Prev Med . 2001;21(4 Suppl):66-88.

- Serdula MK, Brewer RD, Gillespie C, Denny CH, Mokdad A. Trends in alcohol use and binge drinking, 1985-1999: results of a multi-state survey External . Am J Prev Med . 2004;26(4):294-298

- National Prevention Council. National Prevention Strategy: Preventing Drug Abuse and Excessive Alcohol Use [PDF-4.7MB]. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011.

- Bonnie RJ and O’Connell ME, editors. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility External . Committee on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) Application website . Accessed February 29, 2024.

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD. 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption External . Am J Prev Med . 2015;49(5):e73-79.

- Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students External . Pediatrics . 2007;119(1):76-85.

- Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent and reduce underage drinking External . Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General;2007.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data . Accessed on September 13, 2023.

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2021: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use external icon . Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2023.

- Elder R, Lawrence B, Janes G, et al. Enhanced enforcement of laws prohibiting sale of alcohol to minors: systematic review of effectiveness for reducing sales and underage drinking External [PDF-4MB]. Transportation Research E-Circular . 2007;E-C123:181-188.

- The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Alcohol & Health website . Accessed October 18, 2016.

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

- CDC Alcohol Portal

- Binge Drinking

- Check Your Drinking

- Drinking & Driving

- Underage Drinking

- Alcohol & Pregnancy

- Alcohol & Cancer

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Open access

- Published: 28 February 2023

Young people’s explanations for the decline in youth drinking in England

- Victoria Whitaker 1 ,

- Penny Curtis 2 ,

- Hannah Fairbrother 2 ,

- Melissa Oldham 3 &

- John Holmes 1

BMC Public Health volume 23 , Article number: 402 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

7 Citations

92 Altmetric

Metrics details

Youth alcohol consumption has fallen markedly over the last twenty years in England. This paper explores the drivers of the decline from the perspectives of young people.

The study used two methods in a convergent triangulation design. We undertook 38 individual or group qualitative interviews with 96 participants in various educational contexts in England. An online survey of 547 young people in England, was also conducted. Participants were aged between 12–19 years. For both data sources, participants were asked why they thought youth alcohol drinking might be in decline. Analysis of interview data was both deductive and inductive, guided by a thematic approach. Content analysis of survey responses further refined these themes and indicated their prevalence within a larger sample.

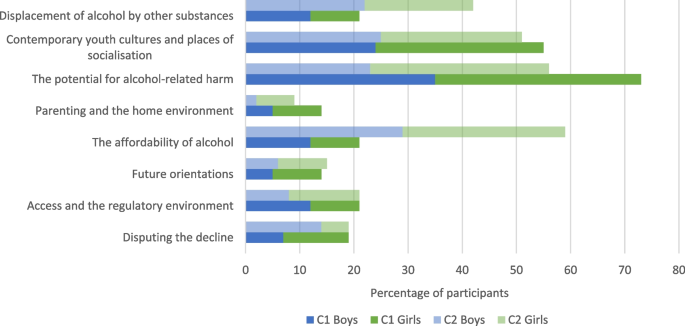

The research identified eight key themes that young people used to explain the decline in youth drinking: The potential for alcohol-related harm; Contemporary youth cultures and places of socialisation; The affordability of alcohol; Displacement of alcohol by other substances; Access and the regulatory environment; Disputing the decline; Future Orientations; and Parenting and the home environment. Heterogeneity in the experiences and perspectives of different groups of young people was evident, particularly in relation to age, gender, and socio-economic position.

Conclusions

Young people’s explanations for the decline in youth drinking in England aligned well with those generated by researchers and commentators in prior literature. Our findings suggest that changing practices of socialisation, decreased alcohol affordability and changed attitudes toward risk and self-governance may be key explanations.

Peer Review reports

Youth drinking is in decline in many high-income countries. This global trend manifests in terms of delayed age of initiation of drinking, and reductions in the volume and frequency of alcohol consumption [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. While approximately synchronous national declines in youth drinking are evident in a number of high-income countries, there is substantial variation between countries in these declines [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Although youth alcohol consumption in England was high at the turn of the millennium, relative to international counterparts, England has nonetheless seen particularly sharp declines in youth alcohol drinking, especially amongst boys [ 4 ].

A number of potential drivers have been proposed for these changes. These include policy initiatives targeting underage purchasing [ 8 , 9 ], the role of migration from countries with abstemious attitudes to alcohol [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], economic factors that have made alcohol less affordable to young people [ 9 , 12 , 13 ], changes in prevailing social norms, particularly young people’s conscientiousness with regard to education [ 6 , 14 , 15 ], changes towards more authoritative and warm parenting relationships [ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ], drug substitution – in particular toward the use of cannabis [ 22 , 23 , 24 ], greater health consciousness amongst young people [ 9 , 25 , 26 ] and multiple mechanisms related to the proliferation of digital and internet-based technologies, including changes in the spatio-temporal structure of young people’s lives [ 9 , 27 ]. However, reviews have concluded that there remains insufficient evidence in favour of any of these explanations as a key driver of the decline in youth drinking [ 5 , 9 , 25 ]. Instead, researchers have increasingly sought more complex explanations that draw on the interaction of multiple factors or the extent of change is moderated by country-level characteristics [ 28 , 29 ], although these remain untested.

Qualitative studies echo many of these findings. For example, Torronen et al. [ 30 ] suggest, among other explanations, that drinking is no longer a key expression of normative masculinity, that social media deters drinking by facilitating surveillance of drunken behaviour while also provide socialising opportunities that do not involve drinking, and that a social trend towards healthiness has required a broad reorganisation of some young people’s habits and practices [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Despite some accounts suggesting that non-drinking is achievable due its normality within some age and peer groups [ 34 ], a separate literature also describes the complex strategies that many young people employ to achieve light drinking or abstinence. These include discrete management of consumption (e.g. pouring away half-finished drinks or pretending a non-alcoholic drink contains alcohol), claiming to be ‘taking a night off’ or actually having short- or long-term periods of abstinence while retaining the possibility of drinking in future [ 35 , 36 ]. Such strategies suggest that light- or non-drinking young people must still negotiate social tensions around alcohol consumption despite the decline in youth drinking, although successful negotiation of these tension may reinforce positive self-perceptions of autonomy, individuality and authenticity [ 37 ].

In this paper, we draw upon the social studies of childhood to inform a child-centred approach, and draw on two methods to explore young people’s own ideas about what might be driving the decline in youth alcohol consumption. This conceptual approach [ 38 ] is concerned with understanding “how children learn about the social world, the sense they make of it and the ways in which their experiential sense-making might shape the things they choose to do, the opinions they express and the perspectives on the world that they come to embrace and embody” ([ 38 ]:1). We take care to avoid the positioning of young people as somehow marginal to society and, instead, proceed from a standpoint that acknowledges that young people are active participants within society [ 39 ]. As social beings, young people learn about the world in which they live, and their place within it, through interactions with others. Our conceptual approach thus necessarily highlights the need to appreciate young people’s locatedness within networks of familial and extra-familial relationships of dependence, independence and interdependence [ 40 ].

Moreover, in grounding our research approach within the social studies of childhood, we also pay attention to the views of young people as individuals: “differentiated not only by gender, ethnicity, age or health status but also by the different and particular circumstances of their own biographies” ([ 38 ]:1). Reflecting this stance, we therefore present, in this paper, a child-centred account, articulated through the voices of individual young people and presented in verbatim quotes. This allows for an understanding of how young people themselves may be contributing to creating and sustaining the declines in alcohol consumption, rather than analysing these as phenomena happening to them and driven by forces external to them.

Data were generated in two phases between November 2018 and July 2019 within a convergent triangulation design [ 41 ]. This aimed to cross-validate young people’s perspectives on the decline in youth drinking using different data sources. In Phase 1, we undertook face-to-face discussions with young people in schools and other educational establishments. In Phase 2, we conducted an online survey to estimate the prevalence of different perspectives on the decline in youth drinking. As the survey used free-text responses, it also provided additional qualitative data to support the Phase 1 data. Triangulation took place during data analysis to align key themes across data sources, and then by comparing the prevalence of themes in the Phase 2 survey to their prominence and participants’ perceptions of their importance within the Phase 1 qualitative data.

Two age cohorts of young people were recruited: cohort 1 (C1) aged 12–15 and cohort 2 (C2) aged 16–19. These age cohorts were defined with reference to a larger project on the decline in youth drinking, of which this study is one component [ 42 ]. The data was collected in England, where the minimum legal purchase age for alcohol is 18. Although there is no prohibition on serving alcohol to anyone aged over five in a private home and over-16 s can consume alcohol (but not spirits) in a pub if it is served with a meal and they are accompanied by an adult, underage drinking is generally understood to mean drinking before age 18. We therefore treat such references in our data accordingly.

Phase one methods

Recruitment.

Ninety-six young people (Supplementary Table 1 ) were recruited from 5 socio-economically and geographically contrasting schools (two urban affluent, one urban deprived and two rural), two further education (FE) colleges and a university. All were within or close to a single city in the North of England.

Schools and FE colleges were identified by reference to the proportion of young people in each school in receipt of government financial support for school meals [ 43 ]. Rates of eligibility for free school meals are reported as percentage ranges to protect confidentiality (Table 1 ). Although free school meal data was absent for one of the FE colleges, it was chosen as a research site as it was situated in a highly deprived local authority area. The relative rurality of schools was determined through assessment of the distance between the school site and the city centre, and local area knowledge (these characteristics are not reported to protect the confidentiality of participating schools). University students were identified using an internal university email distribution list.

Recruitment was planned to take place in three schools (1 affluent, 1 deprived and 1 rural) As the first rural school admitted young people up to the age of 16 only, a second rural school, enrolling young people up to the age of 18, was also included. Following school-based recruitment and data collection, an under-representation of older, affluent school pupils was noted. Five additional C2 pupils from a second, urban affluent school were therefore recruited.

Information sheets were distributed prior to interviews, via email. For participants aged under 16, separate child and parent information sheets and parental consent forms were provided to schools, and distributed to both parents and young people.

All interviews were scheduled at the convenience of the educational institution and took place in either educational establishments or participants’ homes. On the day of the interview, the researcher recapped the information sheet and provided an opportunity to ask questions. All participants provided written consent and were advised that they could withdraw their consent to participate at any point. Written parental consent for young people aged under 16 was a prerequisite of participation. Participants were remunerated for their time with shopping vouchers and a small financial reward was offered to each participating school.

Data generation

Data were generated in 38 semi-structured, interviews. Participants had the option to participate individually or in friendship groups – according to their preferences. There was one individual interview with a university student and all other interviews were conducted in small friendship-groups, comprising between two and four young people. Friendship group interviews are argued to help young people to feel comfortable in sharing their views [ 44 ]. Interviews in schools ( n = 31) and colleges ( n = 4) were constrained by lesson duration and typically lasted between 40 and 60 min. The remaining interviews were not time-limited in this way and lasted up to an hour and a half. Interviews explored alcohol within the context of peer and family relationships, and in relation to other consumption and health practices. While interviews employed a range of creative, participatory methods (to be reported in a future publication), this paper reports young people’s spontaneous responses to the ‘mini-debate’ question, “why do you think young people today are drinking less alcohol?”.

Data analysis

Anonymisation of interviews took place at the point of transcription. Analysis was aided by the qualitative analysis software, NVivo 12. Given the congruence between the reasons for the decline that young people asserted in interviews and those discussed in the extant literature, debate data were deductively coded under the following headings: ‘Disputing the decline’, ‘Drug substitution’, ‘Digital technology’, Difficulty of access’, ‘Economic reasons’, ‘Parenting’, ‘Awareness of health risks’ and ‘Other’. Data recorded under each code was further sub-divided by educational context and age group. Members of the research team independently reviewed a sub-set of codes to facilitate an inductive, thematic analysis that facilitated the deduction of eight themes [ 45 ]. These initial eight themes were further refined via triangulation with the phase two data (see below). Final thematic headings are described at the start of the results section.

Phase two methods

Survey participants were recruited using targeted, paid-for advertisements on both Facebook and Instagram. This approach is responsive to the dynamic patterns of young people’s social media use [ 46 ]. The age range and geographical reach of the adverts aligned with Phase One of the methods to ensure a comparable sample. Participants provided consent before they were able to access the survey questions. Completion of the survey entered participants into a prize draw for a shopping voucher.

Participants completed an online survey, developed and administered using Qualtrics. The survey included two demographic questions (age and gender) followed by a free text question asking why the respondent thought youth drinking was in decline.

To reduce the likelihood that respondents would falsely specify their age in order to be eligible for the prize draw [ 47 ], we did not disclose the study’s age range to survey participants. Although we included all respondents in the prize draw, data from participants outside of the 12–19 age range were not included in our analyses. To minimise the time commitment required to complete the survey and promote engagement, we restricted the collection of demographic data to the factors noted (gender and age).

The online survey was completed over a period of two weeks, by 547 young people aged 12–19 years (Table 2 ).

Survey data were first stratified by age and gender before undertaking an initial reading of the free-text responses. Respondents typically provided a single sentence in response to the free-text question, but multiple reasons for the decline in youth drinking were often given.

The initial reading of the free-text responses suggested broad convergence with the eight themes identified in the interviews, but also enabled refinement of the initial themes as part of the triangulation process. For example, the concept of future orientations was developed to include notions of futurity related to work, not solely higher education. This refinement generated a common set of themes from phases one and two that structure our reporting of findings and comparison across data sources.

To assess the prevalence of each theme within the phase two dataset, we undertook a content analysis to code each of the survey responses to one of the eight themes and calculated the proportion of respondents citing each theme. Reflecting the multiple reasons that young people often gave in their free-text responses to the survey, individuals’ responses could be coded to multiple themes. Content analysis was undertaken by VW and PC, any coding disagreement was resolved by discussion. (Supplementary Table 2 ).

In the results below, we triangulate the phases one and two data by comparing the prevalence of themes in the survey with their prominence in the qualitative data and by using the free-text responses in the survey as qualitative data to provide support for or contrast with themes from the interviews. The information about the speaker provided after quotes is more detailed for phase one interviewees than phase two survey respondents, reflecting the data collected.

The research identified eight key themes that young people used to explain the decline in youth drinking: The research identified eight key themes that young people used to explain the decline in youth drinking: The potential for alcohol-related harm; Contemporary youth cultures and places of socialisation; The affordability of alcohol; Displacement of alcohol by other substances; Access and the regulatory environment; Disputing the decline; Future Orientations; and Parenting and the home environment.

The most commonly cited reasons for the decline in youth drinking identified by survey respondents fell under the themes ‘the potential for alcohol related harm’ (32%), contemporary youth cultures and places of socialisation (27%), and ‘affordability’ (22%). Young people were least likely to provide responses categorised as ‘parenting’ (6%), ‘future orientations’ (8%), or ‘disputing the decline’ (9%). There were some notable differences in responses between age cohorts, with largest disparities seen in relation to the themes of: affordability (C2 = 29%; C1 = 10%) and displacement of alcohol by other substances (C2 = 21%; C1 = 10%) (Supplementary Table 2 ; Fig. 1 ).

Percentage of respondents citing explanations for the decline in youth drinking by cohort and gender

In the following sections we use the interview data to discuss each theme, starting with those cited by most respondents in the survey, and then use the survey data to provide additional insight.

The potential for alcohol-related harm

Young people consistently noted a diversity of risks associated with the consumption of alcohol. There was broad understanding of the chronic health harms associated with alcohol consumption, including liver disease, cancer, mental ill-health, dependence and death, although cardiovascular risks were a notable omission from young people’s responses. However, concern for the shorter-term or social consequences of alcohol consumption were also prominent and included: public drunkenness, damage to personal relationships, accidents and drink-driving. Some girls also stressed the possibility of gendered risks: sexual violence for girls and physical violence for boys.

C2 participants additionally drew upon their experiential knowledge of alcohol consumption to emphasise the undesirable effects it could have, including vomiting, anti-social behaviour and hangovers, all of which were argued to be deterrents to drinking. Henry, for example, asked: ‘Who wants to really throw up and have a hangover? I mean it’s not really worth it in my opinion’ (male, C2, University Student).

Different patterns of drinking were, however, thought to be associated with different levels of risk of harm. Binge drinking, or daily drinking, were considered the antitheses of safe drinking. Nevertheless, alcohol consumption was generally described as purposeful and oriented towards intoxication to some degree; ‘I only want to drink if I know I’m going to feel the effects’ (Charlotte, female, C2, urban affluent). In this context, ‘properly-managed’ drunkenness was seen as a positive outcome of drinking, associated with a level of risk of harm that young people were prepared to accept.

Among survey respondents, the potential for alcohol related harm was the most frequently asserted contributory factor to the decline in youth alcohol consumption (32%). This remained true when sub-dividing responses by age and gender. In both datasets, discussion of risk and the associated patterns of self-governance were explicitly linked with the desire to avoid health-related harms, rather than a decision to promote healthy lifestyle choices.

Contemporary youth cultures and places of socialisation

Several aspects of contemporary youth culture were considered to be mediators of reductions in youth alcohol consumption by interview participants. In summary, these elements related to the timing and locations of young people’s alcohol consumption, and – as also suggested in the parenting theme below—a shift in the social cachet of alcohol for today’s young people relative to prior generations.

First, infrequent socialisation outside of the home during the school week and the importance of social media for everyday socialisation were highlighted. This was especially evident in the accounts of participants still in compulsory education and aged under 18. Moreover, there was also general agreement that young people benefited from the availability of diverse forms of distraction and entertainment – particularly, though not exclusively, associated with the use of social media—that both mitigated against boredom and facilitated forms of peer interaction within which alcohol played little, if any, part.

Second, legislative restrictions have significantly curtailed contemporary young people’s access to spaces licensed to sell alcohol and young people have responded with a shift away from public sites of alcohol-related socialisation, such as pubs. Drinking outside in parks or ‘the woods’ was also frowned upon and considered a mark of immaturity, or an unnecessary risk. Consequently, underage drinking was largely limited to parties within private homes, at weekends, or on special occasions. Drinking occasions were also timed to ensure they did not coincide with exams or impede study.

Third, alcohol was argued to have lost much of its potency as a marker of rebellion within youth culture: ‘you’ve not got the people trying to be like “Oh, I’m breaking the rules, I’m doing something I shouldn’t”, trying to get attention’ (Kelly, female, C2, rural). Young people across the age range noted both a lessening of pressure from peers to consume alcohol (compared with what they assumed had been the case previously) and a greater acceptance of abstinence. Nevertheless, alcohol retained value as a social lubricant for university students and there was a perception of other – and othered—manifestations of peer culture, within which alcohol consumption was more prevalent.

It probably varies a lot around the UK, […] where in some parts it’s kind of cool to go out drinking both days of the weekend like Friday, Saturday, Sunday, like, skipping school to go and get mashed or whatever, but then I kind of hear that’s just a bit desperate, like. (George, male, C2, urban affluent)

Changes in youth cultures and in young people’s experiences and places of socialisation were the second most common theme in the survey data (27%). Within this theme, and consistent with the interview data, three sub-themes were identified. First, alcohol was described as no longer highly valued in youth culture, partly due to its ubiquity, and a resultant lack of ‘hype’ or ‘coolness’ around it: ‘It’s become almost normalised to drink alcohol as you grow up you realise it’s not as rebellious as it seems and it loses its thrill in a way’ (C1 female). Second, young people described themselves as being able to enjoy themselves without recourse to alcohol (‘They don’t need it to have fun’, C1 male). Third, relative to prior generations, young people described themselves as having less free time, as socialising less frequently, and as socialising in ways that did not require leaving the home and/or face-to-face interaction.

The affordability of alcohol

Young people commonly referred to cost when discussing the decline in youth alcohol consumption. However, this played out quite differently among young people from different contexts. Young people in the affluent schools emphasised the relative cost of alcohol within a broader landscape of purchasing decisions. Although they had access to money to spend, they preferred to use this to purchase food, clothes, books or public transport rather than to buy alcohol:

Interviewer: What is it you choose to spend your money on then? Tom: Going to town, snacks from Sainsbury’s [ major supermarket chain ] and stuff. (male, C1, urban affluent school).

A few of the C2, affluent young people also reported saving their money for significant projects: university or to take holidays with friends. In contrast, young people from the deprived and rural schools, and from the FE colleges, indicated that they lacked adequate access to financial resources and the cost of alcohol was seen to be a deterrent to drinking, particularly when purchased in city centre locations. Maisie, for example, declared drinking in town to be: ‘More expensive, innit [isn’t it]’ (female, C1, rural school).

Whilst recognising that alcohol pricing might deter young people from some consumption practices, participants also pointed to taking alcohol from parental stores or purchasing cheap forms of alcohol as low-cost alternatives.

Cost was the third most commonly cited reason for the decline amongst survey responses (22%). In contrast to the interview data, where perspectives were differentiated most obviously by socio-economic status, survey responses referring to costs were differentiated by age. Reflecting the reality that most underage supply of alcohol is social [ 48 ], C2(29%) – not C1 (10%)—respondents tended to assert the high cost of alcohol as a plausible contributor to the decline in youth drinking.

Displacement of alcohol by other substances

All references during interviews to the displacement of alcohol by other substances occurred in discussions with C2 participants, potentially reflecting the greater likelihood of older adolescents having direct or indirect experience of wider substance use. Faith (female, C2 further education college), for example, explained that ‘there’s other things like drugs. If they’re not drinking alcohol I feel like they might be doing drugs such as weed.’ Weed (cannabis) was the most frequently mentioned alternative substance in all educational contexts.

Displacement of alcohol by other drugs was considered to be driven by ease of access: ‘it’s just easier to get other things now than it is to get alcohol because you don’t need ID to go and buy some drugs off some random man, do you?’ (Annabelle, female, C2, rural). For those in the deprived school where limited financial resources were noted as a barrier to alcohol use, drugs could also offer a cheaper alternative: ‘obviously alcohol’s monitored, it’s taxed, things like that, but obviously you can’t go to the shop and buy Spice, meaning you’re going to get it for less.’ (Liam, male, C2, urban deprived).

Further, the relative risk of using cannabis, compared with consuming alcohol, was thought to be low: cannabis was argued to have ‘far more benefits than disadvantages’ (Charlotte, female, C2,urban affluent). Cannabis was felt to allow young people to experience a pleasurable ‘high’ without the risk of a hangover the following day and, for affluent young people, the consequent negative effects that this could have on school, university or other work. In this way, the displacement of alcohol by cannabis was framed as a positive choice – derived from young people’s future orientations toward their education and their health.

Reflecting interview responses, age was also an important intersection in the survey data. As noted earlier: 21% of C2 respondents cited drug substitution as a plausible driver of decline, but only 10% of C1 respondents did. Overall 17% of respondents suggested that the substitution of alcohol by other substances might be contributing to the decline in youth drinking. The ready availability and the low cost of alternative substances, in comparison with the cost of alcohol, was reaffirmed by survey respondents.

Access and the regulatory environment

In interviews, young people across contexts and age cohorts, referred to a stricter regulatory environment as a reason for the decline in youth alcohol consumption. Participants cited family stories as key to their understandings of such changes. The penalties imposed on retailers who sell alcohol to young people were highlighted, in particular ‘Challenge / Think 25’ (a scheme that encourages retailers to check the identification of anyone who looks under 25 to prevent sales to under-18 s). Olivia, for example, noted:

Well I would have said it’s got a lot stricter, like, whenever I talk to my mum about it or my grandparents, like, my granny was talking the other day about it and she was saying that, you know, she’d go to the bar at fourteen and get served and not be questioned. (Olivia, female, C2, university student).

Although increased regulation could make access to alcohol more difficult, young people described strategies used to mitigate the deterrent effect. These included buying or borrowing identification in order to purchase alcohol, or drawing on parents’ willingness to supply alcohol to young people.

Perhaps reflecting the ability of young people to bypass restrictions on their access to alcohol (or their lack of desire, or need to buy alcohol), the regulatory environment was only cited in 11% of survey responses. Stricter laws, more stringent enforcement, and policing of regulations, and increasing surveillance of licensed venues were nonetheless considered to be contributory factors to reductions in youth drinking within survey data.

Disputing the decline

Few young people were aware of the decline in youth drinking. Indeed, a notable minority argued that alcohol remained highly visible in their everyday lives or peer relationships. The claim that drinking was in decline was therefore openly challenged by a number of participants from all educational contexts. Charlotte (female, C2, urban affluent school), for example, noted that: ‘I honestly don’t feel that there’s a visible decline, obviously we didn’t see our parents when they were teenagers, but I wouldn’t say we don’t drink a lot’.

The same scepticism was evident but less prominent in survey responses, being cited by only 9% of respondents. While the majority of such respondents simply denied that there had been a decline, with statements such as “They’re not [ drinking less ]”, some drew on personal experience to report heavy drinking either in their neighbourhood or amongst their peers. A small number of respondents suggested that that drinking had been masked, rather than reduced, by young people’s increasing skill in hiding their alcohol consumption from the adult gaze: “they’re just sneaky about it” (C1, girl) and are “doing it more secretly” (C2, boy).

Future orientations

A number of C2 young people in the affluent schools described their generation as more mature and responsible than previous generations and more concerned about ‘doing well’ to secure their futures.

‘I think especially like in sixth form [ the final two years of secondary school education, typically ages 16-18 ], like, it is a lot of work, we have like a lot of homework and everything and I feel like everyone wants to do good’ (Agnes, female, C2, urban affluent).

George and Alice (male and female, C2,urban affluent) also noted, they did not want to ‘throw away’ the opportunities that school offered them and young people in the affluent school were keen to achieve their academic potential and to study at university. School-related work was therefore an important structuring element in their everyday lives, as Iqbal (male, C2, urban affluent) made clear. He described spending ‘a few hours every day or something like that, just to like get homework done literally and keep up with notes, you’ve got to do a set amount’.

Focussing on educational achievement was seen as key to optimising young people’s futures and therefore as antithetical to drinking. As such, it was a plausible reason from the participants’ perspective for the decline in youth alcohol consumption.

Although ‘future orientations’ was amongst the least frequently cited reasons for the decline in the survey data (8%), a concern for young people’s future wellbeing was nonetheless evident. One young man (C1) noted: ‘We’re more worried about our futures than anyone so far – we don’t have the time or the privilege to waste getting drunk’. In contrast to the interview data where there was a predominance of data from C2 participants from the affluent school, evidence that concern for the future constituted a reason for declines in youth drinking emerged in the survey at a consistent level across age cohorts (8%); there was no socio-economic data to cross-reference. The aforementioned absence of data relating to ‘future orientations’ from specific subsets of young people within interviews cannot necessarily be interpreted as indicative of a difference in mind-set, however.

Parenting and the home environment

Young people in interviews highlighted changes in parenting practices as significant for the decline in youth drinking. Nafeesa (female, C2, further education college), for example, suggested: ‘I think parents probably might be stricter and might have an influence’. Contemporary parents were described as more concerned about under-age drinking than previous generations of parents and were thought to maintain closer surveillance over their children. C1 young people asserted that their parents would not wish them to drink at all while, within C2 accounts, parents were noted to advocate responsible drinking practices.

With the exception of families with religious beliefs that did not allow the consumption of alcohol, the majority of young people noted the continuing presence – rather than the absence—of alcohol and its ready accessibility in their home environments. Young people were therefore often able to access alcohol in the home either without parental permission—by ‘sneaking’ a drink (Jessica, female, C1, urban deprived), or with parental permission as part of their induction into ‘responsible drinking’. For example, Kelly (female, C2, rural), noted that her ‘first taste’ of alcohol was provided by her mum, at home.

Similar issues were raised by survey respondents. Although changes in parenting were least commonly noted as potential contributors to the decline in youth drinking (6%), similar sub-themes were identifiable in the free-text data. Respondents described contemporary parents as ‘stricter’, more controlling or more protective. However, a small number suggested that rather than being more controlling, some parents were more lenient and permissive, normalising drinking ‘so it becomes less of a taboo’ (C1 female), and ‘Because our parents let us drink small amounts younger, therefore meaning that as we get older, the urge to drink is much less severe’ (C1, male).

The research identified eight key themes that young people used to explain the decline in youth drinking and these were largely consistent across the two phases of the research. The themes were: Disputing the decline; The affordability of alcohol; Access and the regulatory environment; Parenting and the home environment; Future Orientations; Displacement of alcohol by other substances; The potential for alcohol-related harm; and Contemporary youth cultures and places of socialisation. The survey data additionally demonstrated a degree of heterogeneity in the experiences and perspectives of different groups of young people, such that those of different ages, gender, and socio-economic position appeared more or less likely to identify particular explanations for the decline.

The key themes derived from young people’s perspectives resonated strongly with reasons for the decline of youth drinking that have been hypothesised in the academic literature. Building on this, we further describe the importance of place and the responsibilisation of youth in shaping contemporary youth drinking practices in England. While both the qualitative data and the survey responses addressed a range of factors thought to be contributing to the decline in youth alcohol consumption, changing notions of risk and the ways these are interwoven with shifting social contexts appear to underpin many of these. In some cases, risk related to young people’s perceptions of risks to themselves, while in other cases risk related more to others’ perceptions of risks associated with young people.

For example, respondents highlighted the stringent regulatory retail environment for alcohol and the difficulties that under-age consumers had in accessing alcohol from licensed vendors. Regulatory changes in the UK have, to some extent, been driven by the desire to prevent binge drinking and the crime and anti-social behaviour associated with it, and to deter underage drinking. This arises in part from the growing understanding of the potential and specific damages of alcohol to young people [ 49 ], as well as the perceived threat that disorderly behaviour by young people poses to wider society [ 50 ].

Partly as a result of these regulatory constraints on access to alcohol and also the high cost of alcohol in licensed premises [ 51 ], drinking was almost entirely limited to the home for today’s underage drinkers. Domestic spaces were also key sites for drinking and ‘pre-drinking’ by those aged 18 and over [ 52 , 53 , 54 ]. However, this ‘homification’ of young people’s alcohol consumption also arises from other non-risk related factors. In the UK context, for example, specific policies targeting anti-social behaviour have sought to problematise and diminish young people’s presence and visibility within outdoor public spaces (for example, [ 55 ]). Such policies, we argue, reflect well-established contentions that some young people are seen to be ‘risky’ in public spaces, while others are ‘at risk’ [ 56 ]. And as James ([ 38 ]:15) has noted, young people’s social embeddedness means that they are, inevitably, influenced by such cultural moralities and institutional constraints.

Young people highlighted that underage drinking has become less socially acceptable to contemporary youth. Both displays of public drunkenness (in digital or physical spaces) and drinking in outdoor spaces – a practice reported for previous generations of youth, were denounced. This was particularly true within affluent and Higher Education contexts, perhaps suggesting that the ‘sensible, low-risk drinking message’ advocated within the English National Alcohol Strategy 2007 [ 57 ] has perfused cultural sensibilities in at least some sub-groups of young people. In addition to their denouncement of risky drinking, however, participants also described diversification of young people’s leisure-time activities – often including the physically-distanced use of digital media and/or gaming – that have opened up opportunities for young people to socialise in ways that do not involve alcohol consumption [ 30 ] and which, often, exclude the use of outdoor and public spaces.

Although evidence for changes in parenting styles over time is sparse [ 58 ], young people postulated that parenting had changed toward greater levels of strictness and surveillance. In general terms, this reaffirms accounts describing the intensification of contemporary parenting and greater levels of risk aversion amongst contemporary parents [ 59 ]. In terms of alcohol drinking specifically, it also echoes Larm et al.’s [ 58 ] finding that parental monitoring and restrictive parental attitudes toward alcohol have increased during the period of declining youth drinking. Moreover, some young people in our study suggested a more complex relationship between changes in parenting and trends in youth drinking, perhaps reflecting the diversities in familial adult–child relations, characterised by Zeiher [ 40 ] as dependent, independent and interdependent. Young people in our study argued that it is the relative leniency of contemporary parenting that may support declines in drinking by reducing the need for young people to rebel against parental rules. Nevertheless, findings in the broader alcohol literature suggest that parents harbour concerns that ‘strictness’ in relation to alcohol consumption can be counter-productive [ 6 , 60 , 61 , 62 ]. Any association between particular parenting styles and the emergence of recent alcohol trends is therefore unclear.

Young people’s suggestion that they exhibit greater maturity and responsibility than previous generations was closely aligned to how they made sense of the ‘risks’ posed by uncertain futures [ 63 ]. Educational success was considered key to some young people’s accomplishment within an increasingly competitive global economy. Consequently, young people restricted their drinking occasions to time periods when alcohol consumption would not impede their attainment. However, an important caveat to this finding is that a number of interview respondents were at a time in their education where they were due to sit national examinations and this may have sharpened the importance of educational success in their mindsThis finding aligns with the reduced frequency of alcohol consumption amongst 11–24 year olds in England [ 4 ]. The lack of references to the importance of education amongst deprived interview respondents, however, potentially reaffirms the centrality of class as a critical factor in the future economic security, and the educational experiences and aspirations of today’s young people [ 50 ]. It also confirms and reinforces the need to understand how perspectives and expectations, as they relate to alcohol consumption, manifest for individual young people who are variably located with respect to such issues as class, ethnicity, gender and age.

While the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) [ 64 ] has described today’s young people as ‘Generation Sensible’ because they’shun alcohol, tobacco and even sex’, declines in youth drinking have also been accompanied by declines in youth drug taking in England [ 42 ]. Despite this apparent risk aversion, young people in our study – particularly those aged-16–18 for whom drugs were visible in their everyday lives—considered drug substitution a plausible reason for declines in alcohol consumption. They emphasised cannabis as a key substitute for alcohol, cohering with data demonstrating that this is the most commonly used drug amongst young people [ 65 ] and reinforcing the suggestion that polices designed to limit alcohol use may have the unintended consequences of increasing cannabis use among some young people [ 66 ]. Cannabis was seen to be an accessible, low cost substitute for alcohol, echoing findings from a recent review by Subbaraman [ 67 ], which suggests that substitution is likely to occur in environments in which cannabis can be obtained with relative ease. However, importantly, substituting alcohol with cannabis was viewed as a risk-reducing activity. Our respondents argued cannabis has positive benefits for young people. They thought it was less harmful and less likely to be associated with negative effects on their school or work lives when compared to alcohol.