The Future of Work Should Mean Working Less

By Jonathan Malesic Sept. 23, 2021

- Share full article

Mr. Malesic is a writer and a former academic, sushi chef and parking lot attendant who holds a Ph.D. in religious studies. He is the author of the forthcoming book “ The End of Burnout ,” from which this essay is adapted.

A dozen years ago, my friend Patricia Nordeen was an ambitious academic, teaching at the University of Chicago and speaking at conferences across the country. “Being a political theorist was my entire adult identity,” she told me recently. Her work determined where she lived and who her friends were. She loved it. Her life, from classes to research to hours spent in campus cafes, felt like one long, fascinating conversation about human nature and government.

But then she started getting very sick. She needed spinal fusion surgeries. She had daily migraines. It became impossible to continue her career. She went on disability and moved in with relatives. For three years she had frequent bouts of paralysis. She was eventually diagnosed with a subtype of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, a group of hereditary disorders that weaken collagen, a component of many sorts of tissue.

“I’ve had to evaluate my core values,” she said, and find a new identity and community without the work she loved. Chronic pain made it hard to write, sometimes even to read. She started drawing, painting and making collages, posting the art on Instagram. She made friends there and began collaborations with them, like a 100-day series of sketchbook pages — abstract watercolors, collages, flower studies — she exchanged with another artist. A project like this allows her to exercise her curiosity. It also “gives me a sense of validation, like I’m part of society,” she said.

Art does not give Patricia the total satisfaction academia did. It doesn’t order her whole life. But for that reason, I see in it an important effort, one every one of us will have to make sooner or later: an effort to prove, to herself and others, that we exist to do more than just work.

We need that truth now, when millions are returning to in-person work after nearly two years of mass unemployment and working from home. The conventional approach to work — from the sanctity of the 40-hour week to the ideal of upward mobility — led us to widespread dissatisfaction and seemingly ubiquitous burnout even before the pandemic. Now, the moral structure of work is up for grabs. And with labor-friendly economic conditions, workers have little to lose by making creative demands on employers. We now have space to reimagine how work fits into a good life.

As it is, work sits at the heart of Americans’ vision of human flourishing. It’s much more than how we earn a living. It’s how we earn dignity: the right to count in society and enjoy its benefits. It’s how we prove our moral character. And it’s where we seek meaning and purpose, which many of us interpret in spiritual terms.

Political, religious and business leaders have promoted this vision for centuries, from Capt. John Smith’s decree that slackers would be banished from the Jamestown settlement to Silicon Valley gurus’ touting work as a transcendent activity . Work is our highest good; “do your job,” our supreme moral mandate.

But work often doesn’t live up to these ideals. In our dissent from this vision and our creation of a better one, we ought to begin with the idea that each one of us has dignity whether we work or not. Your job, or lack of one, doesn’t define your human worth.

This view is simple yet radical. It justifies a universal basic income and rights to housing and health care. It justifies a living wage. It also allows us to see not just unemployment but retirement, disability and caregiving as normal, legitimate ways to live.

When American politicians talk about the dignity of work, like when they argue that welfare recipients must be employed, they usually mean you count only if you work for pay.

The pandemic revealed just how false this notion is. Millions lost their jobs overnight. They didn’t lose their dignity. Congress acknowledged this fact, offering unprecedented jobless benefits: for some, a living wage without having to work.

The idea that all people have dignity before they ever work, or if they never do, has been central to Catholic social teaching for at least 130 years. In that time, popes have argued that jobs ought to fit the capacities of the people who hold them, not the productivity metrics of their employers. Writing in 1891, Pope Leo XIII argued that working conditions, including hours, should be adapted to “the health and strength of the workman.”

Leo mentioned miners as deserving “shorter hours in proportion as their labor is more severe and trying to health.” Today, we might say the same about nurses, or any worker whose ordinary limitations — whether a bad back or a mental health condition — makes an intense eight-hour shift too much to bear. Patricia Nordeen would like to teach again one day, but given her health at the moment, full-time work seems out of the question.

Because each of us is both dignified and fragile, our new vision should prioritize compassion for workers, in light of work’s power to deform their bodies, minds and souls. As Eyal Press argues in his new book, “ Dirty Work ,” people who work in prisons, slaughterhouses and oil fields often suffer moral injury, including post-traumatic stress disorder, on the job. This reality challenges the notion that all work builds character.

Wage labor can harm us in subtle and insidious ways, too. The American ideal of a good life earned through work is “disciplinary,” according to the Marxist feminist political philosopher Kathi Weeks, a professor at Duke and often-cited critic of the modern work ethic. “It constructs docile subjects,” she wrote in her 2011 book, “ The Problem With Work .” Day to day, that means we feel pressure to become the people our bosses, colleagues, clients and customers want us to be. When that pressure conflicts with our human needs and well-being, we can fall into burnout and despair.

To limit work’s negative moral effects on people, we should set harder limits on working hours. Dr. Weeks calls for a six-hour work day with no pay reduction. And we who demand labor from others ought to expect a bit less of people whose jobs grind them down.

In recent years, the public has become more aware of conditions in warehouses and the gig economy. Yet we have relied on inventory pickers and delivery drivers ever more during the pandemic. Maybe compassion can lead us to realize we don’t need instant delivery of everything and that workers bear the often-invisible cost of our cheap meat and oil.

The vision of less work must also encompass more leisure. For a time the pandemic took away countless activities, from dinner parties and concerts to in-person civic meetings and religious worship. Once they can be enjoyed safely, we ought to reclaim them as what life is primarily about, where we are fully ourselves and aspire to transcendence.

Leisure is what we do for its own sake. It serves no higher end. Patricia said that making art is often “meditative” for her. “If I’m trying to draw a plant, I’m really looking at the plant,” she said. “I’m noticing all the different shades of color that maybe I wouldn’t have noticed if I wasn’t drawing it.” Her absorption in the task — the feel of the pen on paper — “puts the pain out of focus.”

It’s true that people often find their jobs meaningful, as Patricia did in her academic career or as I did while working on this essay. But for decades, business leaders have taken this obvious truth too far, preaching that we’ll find the purpose of our lives at work. It’s a convenient narrative for employers, but look at what we actually do all day: For too many of us, if we aren’t breaking our bodies, then we’re drowning in trivial email. This is not the purpose of a human life.

And for those of us fortunate enough to have jobs that consistently provide us with meaning, Patricia’s story is a reminder that we may not always have that kind of work. Anything from a sudden health issue to the natural effects of aging to changing economic conditions can leave us unemployed.

So we should look for purpose beyond our jobs and then fill work in around it. We each have limitless potential, a unique “genius,” as Henry David Thoreau called it. He believed that excessive toil had stunted the spiritual growth of the men who laid the railroad near Walden Pond, where he lived from 1845 to 1847. He saw the pride they took in their work but wrote, “I wish, as you are brothers of mine, that you could have spent your time better than digging in this dirt.”

Pursuing our genius, whether in art or conversation or sparring at a jiujitsu gym, will awaken us to “a higher life than we fell asleep from,” Thoreau wrote. It isn’t the sort of leisure, like culinary tourism, that heaps more labor on others. It is leisure that allows us to escape the normal passage of time without traveling a mile. The mornings Thoreau spent standing in his cabin doorway, “rapt in a revery,” he wrote, “were not time subtracted from my life, but so much over and above my usual allowance.” Compared with that, he thought, labor was time wasted.

Dignity, compassion, leisure: These are pillars of a more humane ethos, one that acknowledges that work is essential to a functioning society but often hinders individual workers’ flourishing. This ethos would certainly benefit Patricia Nordeen and might allow students to benefit from her teaching ability. In practice, this new vision should inspire us to implement universal basic income and a higher minimum wage, shorter shifts for many workers and a shorter workweek for all at full pay. Together, these pillars and policies would keep work in its place, as merely a support for people to spend their time nurturing their greatest talents — or simply being at ease with those they love.

It’s a vision we can approach from multiple directions, befitting America’s intellectual diversity. Pope Leo, Dr. Weeks and Thoreau criticized industrial society from the disparate, often incompatible traditions of Catholicism, Marxist feminism and Transcendentalism. But they agreed that we need to see inherent value in each person and to keep work in check so everyone can attain higher goods.

These thinkers are hardly alone. We might equally take inspiration from W.E.B. Du Bois’s contention that Black Americans would gain political rights through intellectual cultivation and not only relentless labor, or Abraham Joshua Heschel’s view that the Sabbath day of rest “is not an interlude but the climax of living,” or the “ right not to work ” advocated by the disabled artist and writer Sunaura Taylor.

The point is to subordinate work to life. “A life is what each of us needs to get,” wrote Dr. Weeks, and you can’t get one without freedom from work’s domination. “That said,” she continues, “one cannot get something as big as a life on one’s own.”

That means we need one more pillar: solidarity, a recognition that your good and mine are linked. Each of us, when we interact with people doing their jobs, has the power to make their lives miserable. If I’m overworked, I’m likely to overburden you. But the reverse is also true: Your compassion can evoke mine.

Early in the pandemic, we exhibited the virtues we need to realize this vision. Public health compelled us to set limits on many people’s work and provide for those who lost their jobs. We showed — imperfectly — that we could make human well-being more important than productivity. We had solidarity with one another and with the doctors and nurses who battled the disease on the front lines. We limited our trips to the grocery store. We tried to “flatten the curve.”

When the pandemic subsides but work’s threat to our thriving does not, we can practice those virtues again.

Advertisement

The bright future of working from home

There seems to be an endless tide of depressing news in this era of COVID-19. But one silver lining is the long-run explosion of working from home. Since March I have been talking to dozens of CEOs, senior managers, policymakers and journalists about the future of working from home. This has built on my own personal experience from running surveys about working from home and an experiment published in 2015 which saw a 13 percent increase in productivity by employees at a Chinese travel company called Ctrip who worked from home.

So here a few key themes that can hopefully make for some good news:

Mass working from home is here to stay

Once the COVID-19 pandemic passes, rates of people working from home will explode. In 2018, the Bureau of Labor Statistics figures show that 8 percent of all employees worked from home at least one day a week.

I see these numbers more than doubling in a post-pandemic world. I suspect almost all employees who can work from home — which is estimated at about 40 percent of employees — will be allowed to work from home at least one day a week.

Why? Consider these three reasons

Fear of crowds.

Even if COVID-19 passes, the fear of future pandemics will motivate people to move away from urban centers and avoid public transport. So firms will struggle to get their employees back to the office on a daily basis. With the pandemic, working from home has become a standard perk, like sick-leave or health insurance.

Investments in telecommuting technology

By now, we have plenty of experience working from home. We’ve become adept at video conferencing. We’ve fine-tuned our home offices and rescheduled our days. Similarly, offices have tried out, improved and refined life for home-based work forces. In short, we have all paid the startup cost for learning how to work from home, making it far easier to continue.

The end of stigma

Finally, the stigma of working from home has evaporated. Before COVID-19, I frequently heard comments like, “working from home is shirking from home,” or “working remotely is remotely working.” I remember Boris Johnson, who was Mayor of London in 2012 when the London Olympics closed the city down for three weeks, saying working from home was “a skivers paradise.” No longer. All of us have now tried this and we understand we can potentially work effectively — if you have your own room and no kids — at home.

Of course, working from home was already trending up due to improved technology and remote monitoring. It is relatively cheap and easy to buy a top-end laptop and connect it to broadband internet service. This technology also makes it easier to monitor employees at home. Indeed, one senior manager recently told me: “We already track our employees — we know how many emails they send, meetings they attend or documents they write using our office management system. So monitoring them at home is really no different from monitoring them in the office. I see how they are doing and what they are doing whether they are at home or in the office.”

This is not only good news for firms in terms of boosting employee morale while improving productivity, but can also free up significant office space. In our China experiment, Ctrip calculated it increased profits by $2,000 per employee who worked from home.

Best practices in working from home post pandemic

Many of us are currently working from home full-time, with kids in the house, often in shared rooms, bedrooms or even bathrooms. So if working from home is going to continue and even increase once the pandemic is over, there are a few lessons we’ve learned to make telecommuting more effective. Let’s take a look:

Working from home should be part-time

I think the ideal schedule is Monday, Wednesday and Friday in the office and Tuesday and Thursday at home. Most of us need time in the office to stay motivated and creative. Face-to-face meetings are important for spurring and developing new ideas, and at least personally I find it hard to stay focused day after day at home. But we also need peaceful time at home to concentrate, undertake longer-term thinking and often to catch-up on tedious paperwork. And spending the same regular three days in the office each week means we can schedule meetings, lunches, coffees, etc., around that, and plan our “concentration work” during our two days at home.

The choice of Tuesday and Thursday at home comes from talking to managers who are often fearful that a work-from-home day — particularly if attached to a weekend — will turn into a beach day. So Tuesday and Thursday at home avoids creating a big block of days that the boss and the boss of the boss may fear employees may use for unauthorized mini-breaks.

Working from home should be a choice

I found in the Ctrip experiment that many people did not want to work from home. Of the 1,000 employees we asked, only 50 percent volunteered to work from home four days a week for a nine-month stretch. Those who took the offer were typically older married employees with kids. For many younger workers, the office is a core part of their social life, and like the Chinese employees, would happily commute in and out of work each day to see their colleagues. Indeed, surveys in the U.S. suggest up to one-third of us meet our future spouses at work.

Working from home should be flexible

After the end of the 9-month Ctrip experiment, we asked all volunteers if they wanted to continue working from home. Surprisingly, 50 percent of them opted to return to the office. The saying is “the three great enemies of working from home are the fridge, the bed and the TV,” and many of them fell victim to one of them. They told us it was hard to predict in advance, but after a couple of months working from home they figured out if it worked for them or not. And after we let the less-successful home-based employees return to the office, those remaining had a 25 percent higher rate of productivity.

Working from home is a privilege

Working from home for employees should be a perk. In our Ctrip experiment, home-based workers increased their productivity by 13 percent. So on average were being highly productive. But there is always the fear that one or two employees may abuse the system. So those whose performance drops at home should be warned, and if necessary recalled into the office for a couple of months before they are given a second chance.

There are two other impacts of working from home that should be addressed

The first deals with the decline in prices for urban commercial and residential spaces. The impact of a massive roll-out in working from home is likely to be falling demand for both housing and office space in the center of cities like New York and San Francisco. Ever since the 1980s, the centers of large U.S. cities have become denser and more expensive. Younger graduate workers in particular have flocked to city centers and pushed up housing and office prices. This 40-year year bull run has ended .

If prices fell back to their levels in say the 1990s or 2000s this would lead to massive drops of 50 percent or more in city-center apartment and office prices. In reverse, the suburbs may be staging a comeback. If COVID-19 pushed people to part-time working from home and part-time commuting by car, the suburbs are the natural place to locate these smaller drivable offices. The upside to this is the affordability crisis of apartments in city centers could be coming to an end as property prices drop.

The second impact I see is a risk of increased political polarization. In the 1950s, Americans all watched the same media, often lived in similar areas and attended similar schools. By the 2020s, media has become fragmented, residential segregation by income has increased dramatically , and even our schools are starting to fragment with the rise of charter schools.

The one constant equalizer — until recently — was the workplace. We all have to come into work and talk to our colleagues. Hence, those on the extreme left or right are forced to confront others over lunch and in breaks, hopefully moderating their views. If we end up increasing our time at home — particularly during the COVID lock-down — I worry about an explosion of radical political views.

But with an understanding of these risks and some forethought for how to mitigate them, a future with more of us working from home can certainly work well.

Related Topics

More publications, under the cover of darkness: using daylight saving time to measure how ambient light influences criminal behavior, testing paternalism: cash vs. in-kind transfer in rural mexico, humpty-dumpty competitive effects of the at&t - bellsouth merger.

- Yale University

- About Yale Insights

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility

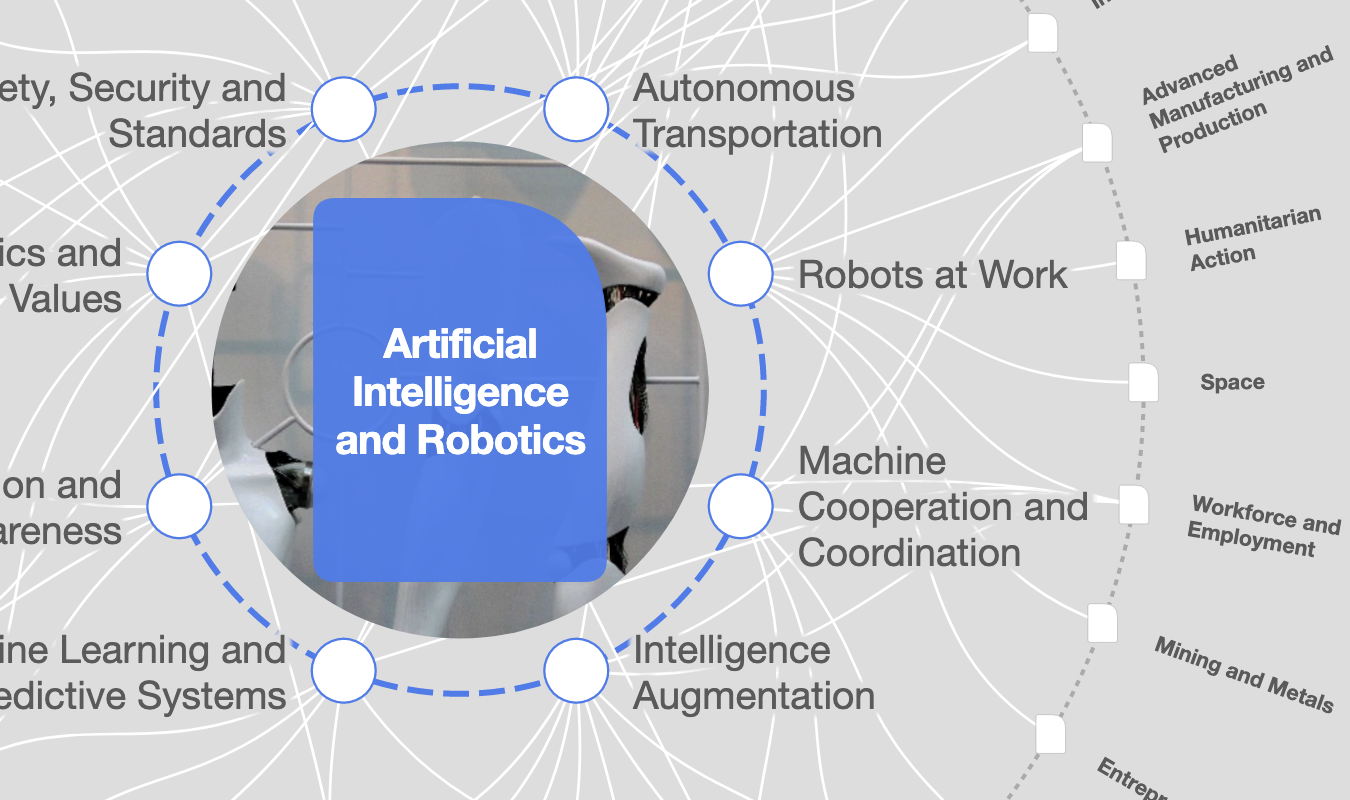

What’s the Future of Work?

Mix smart machines, businesses as platforms, and diverse teams solving complex problems, add a whole lot of uncertainty, and you have a recipe for the future of work. Jeff Schwartz ’87, a principal at Deloitte, discusses how leaders can navigate fast-approaching opportunities and challenges.

- Jeff Schwartz Principal, Deloitte Consulting

The robots are coming! A Pew Research Center survey found that 72% of Americans are concerned about robots and computers taking jobs currently done by humans—though just 2% report having actually lost a job to automation.

In a conversation with Yale Insights last year, Yale SOM labor economist Lisa Kahn said that the effects of automation are already being felt throughout the economy. In fact, the Great Recession likely accelerated the process, both by slowing demand, giving firms a chance to retool without losing sales, and by providing an excuse to lay off unproductive workers.

“We have seen the influences of automation in almost every pocket of the labor market, from the very low end of the skill spectrum to the very high end,” she said. “The future of labor essentially comes down to, where are computers going to replace us and where are computers going to augment us?”

The New Yorker said that economists have long believed that technological changes eliminate some jobs but create plenty of new ones to replace them. Now they aren’t so sure. MIT’s David Autor has found that automation fundamentally alters the supply-and-demand equilibrium. “A subset of people with low skill levels may not be able to earn a reasonable standard of living based on their labor,” he told the magazine. “We see that already.”

So what does it take to keep a job? Kahn’s research has shown that cognitive and social skills are key: “If you have one of them, and especially both of them, I think it’s very likely that you’re going to be pretty safe from automation for a long time.”

To find out more about the future of the work, and how artificial and human intelligence can co-exist in the office, Yale Insights talked with Jeff Schwartz ’87, a principal for Deloitte Consulting and the company’s global lead for human capital marketing, eminence, and brand. Q: What are the key forces shaping the future of work?

Two megatrends are driving the future of work. One is that organizations are being dramatically reoriented and restructured. The historical view of an organization as a hierarchy is being replaced by a view of the organization as a network or an ecosystem. Instead of divisions, functions, or processes, organizations are increasingly being built around teams.

The second big shift has to do with work itself changing. An increasing number of tasks are being accomplished through automation or cognitive computing. To simplify it greatly, if we can articulate the process of something, we can automate it. It’s my expectation that in the next five to ten years everyone will be working next to and with a smart machine they’re not working with today.

Q: What is the role of people in this emerging future?

The question that we’re looking at in every company and every industry is, what are the essential and enduring human skills? What are the things that smart machines can’t do? I’m not quoting it correctly, but Pablo Picasso said something like, “Calculating machines are useless. They can only give you answers.” Asking questions is an essential human skill. I’m not talking about the kind of questions a chat bot can manage. I’m talking about the sorts of creative thinking and inquiry that lets us frame a problem.

For a range of reasons, the problems facing businesses and the public sector are much more complex and multi-disciplinary. The complexity of the problems and the pace of change means we need to work collaboratively, on teams. Working in teams is itself an essential human skill.

The relationship that we're developing with smart machines is different than before. We’re getting a glimpse beyond the digital native to the AI native who doesn't think twice about talking to their phone or any other device. We're getting to the point where natural language interaction—talking to our machines, our machines talking to us—is rebalancing work roles and the ways machines and people can augment each other.

Q: What does it look like to team with smart machines?

Let me offer two examples. Both have been highly popularized, so they should be in some sense familiar. One is IBM’s Watson platform as it relates to medicine. The way the IBM team put it is that after Watson won Jeopardy they sent it to medical school. That meant they fed Watson medical journal articles and data. They developed its capability to read radiology reports and to do oncology diagnoses. At this point, in terms of diagnosis accuracy, the average doctor is around the 50th percentile while Watson is 75th percentile.

Additionally, there’s an explosion of knowledge and data. A really great physician can read a couple hundred journal articles a year, but in any particular field there are thousands of articles written. Teaming with a machine learning technology like Watson could bring all that technical information to bear in diagnosis and coming up with potential treatments while doctors decide on the most appropriate approach and explain to a patient what a diagnosis means, something that currently is very difficult for a machine.

A very different industry, financial services, offers another example. My colleagues Tom Davenport and Jim Guszcza wrote about this recently in the Deloitte Review . One of the examples they use is robo-advisors. They are algorithms, basically, to help create financial portfolios.

Some investors interact directly with robo-advisors online. But many consumers are more comfortable interacting with a person. The financial advisor can still leverage the algorithm’s ability to do the calculations involved in setting up portfolios that meet the desired criteria while focusing on how she or he relates to the customer and ultimately working with more customers.

What these two examples have in common is that there are parts of knowledge work—data sorting, pattern matching, or algorithmic calculations—suited to the machines on our team. Other things are suited to the people on our team. The idea is to work together to augment each other.

Q: How are organizations changing?

What’s an organization going to look like in the 21st century? I think it’s up for grabs. Ronald Coase won his Nobel Prize for telling us in the late 1930s that firms were largely based on transaction costs. Our ability to transact and interact on internet-based platforms has blown away some of our concepts about transaction costs. Work and jobs are being separated from companies because there’s something competing with the traditional corporate organizational form, which is platforms. Beyond thinking about the key design principles of teams, networks, and ecosystems, we need to explore what it means to be a platform-based organization and what it means to be an asset-light organization.

It’s a taxi cab company taking out ads in the Yellow Pages, hiring dispatchers and drivers, and maintaining a fleet of taxis versus Uber, which owns no cars and doesn’t have any drivers. All they have is a platform that connects people that need rides and people that want to provide rides.

The boundaries of organizations in the 21st century are going to be shaped by companies that are the intermediaries between producers and consumers. Or, for many of us today, the platforms that let us constantly shift back and forth between being producers and consumers.

Q: So much of the discussion seems to split the future into either robopocalypse or techno-utopia? Is it that much of a binary?

In 1930, John Maynard Keynes wrote “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” an essay on the future of work. He envisioned that within 100 years the average person would be working 15 hours a week, and we’d have an excessive leisure problem. Obviously, that’s not what happened.

Keynes was a brilliant economist, but he missed something . He missed the number of new fields and human endeavors that would be invented—modern health care, education, and the technology industries, for a start. That’s largely what has driven employment and progress. That’s one of the things that make many of us who are looking at the future of work optimistic. The future doesn’t have to be about grinding out efficiency; it can be about exponential innovation.

It’s less a question of whether robots take our jobs, and more a question of how robots and technology will change our jobs. Automation, and not just robotics, but cognitive technology and AI, natural language processing, and machine learning will take some jobs while also creating new ways of working and extended labor platforms. I think it’s reasonable to expect that all of our jobs and all of our careers will be significantly or fundamentally changed by technology and different labor options.

As that is happening, we have the opportunity to redesign organizations, work, and how we think about careers and learning. If you’re motivated by the idea of living in fast-changing times, it’s going to be pretty exciting. If you’re in fear of fast-changing times, it’s going to be tough.

Q: Today’s cars are huge improvements over Ford’s Model T, but they aren’t so different that we can’t trace the lineage. To what degree have we seen where today’s technology and innovations will take us?

The short answer is, I don’t know. But I agree with William Gibson, who says the future is here, it’s just unevenly distributed. I’m not sure we know what today’s equivalent of the Model T is yet. If we could identify the Model T, the thing that we will incrementally improve far into the future, then we could extrapolate out.

I do think we have an idea of what the 21st century’s drivers might be. Mass production was the driver that enabled the Model T. Platforms, and the way that we interact in the economy, may be one primary driver for the 21st century.

In the early 1960s, Gordon Moore postulated basically that computing power doubles every 18 to 24 months. We’re now 25 to 30 turns into Moore’s Law. When you move something exponentially 25 or 30 turns, every additional doubling is a massive increase in computing and processing power. It makes possible things that simply were not imaginable, economically or technologically, before. We’re applying that to so many domains right now, it’s hard to know where that will go, but exponential technology is a likely another driver.

A third potential driver is in some ways the opposite of the Model T: extreme customization through technologies like additive manufacturing, where the setup costs for creating a different item is practically zero, so that we can both mass customize and mass produce. I think the 21st century will be in some way driven by platforms, exponential technology, and mass customization.

But the fourth driver, which is probably the biggest, is uncertainty and surprise. I was struck by the Queen of England asking after the financial crisis how all the brilliant economists in the UK and around the world, how the profession as a whole, missed something as big as the financial crisis. I think there’s some element of this now in every field. The interaction of highly complex global systems with the uncertainty and unpredictability of human behavior on a massive scale creates the potential for surprise that can happen extremely quickly and be very pervasive. I think that’s only going to continue. It may be fascinating or terrifying—probably a little bit of both.

I don’t think we have yet seen the potential and positive disruption of exponential technologies and platforms play out. I think the next 20 or 30 years will be about new technologies and platforms coming online, but also about adoption and pervasiveness as these ideas work their way into the economy.

Q: What does this mean for individuals?

Learning is the job in the 21st century. Full stop. As Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott at London Business School tell us in The 100-Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity , right now, we’re living on average into our 80s, but millennials can expect to live to 100. What does it look like when the average time in a job is four and a half years and the half-life of a learned domain skill, like a computer language, is five years? How many careers are you going to have?

Adaptability and continual learning are not among the core skills; they are the core skills. Learning new domain knowledge is important, but we can learn it relatively quickly and we can access it highly effectively by collaborating with smart machines. More importantly we need to develop essential human skills, and we need the skills and capacities that let us partner in a team with machines. Individuals and companies need to be organizing around learning. And the learning needs to be organized around dynamism and change at speed.

Individuals have a responsibility for maintaining and developing their own skills and retooling through lifelong learning. Businesses will be benefited by being thoughtful about how they redesign jobs and teams and find ways to facilitate learning. But there is a significant set of responsibilities for government, public policy, and social institutions.

Q: What should that look like?

I recently co-wrote an article titled “ Navigating the Future of Work ” with John Hagel and Josh Bersin. Our observation is that if work is being augmented by on- and off-balance-sheet workers along with machines, in order to benefit from the incredible exponential power of technology and get our arms around the challenges that come along with it, we need to consider how we support people in these different arrangements.

Part of that is helping people through economic transitions. That includes healthcare and different kinds of income insurance. We are going to need really good data on people in a gig economy, so we need to improve the data that we gather on employment, education, and skills.

We need to recognize that each of us will need to do some version of going back to school every decade. We need to ask fundamental questions about how communities, cities, states, and the federal government support that. We need to look at every segment of the population and ask the question: what types of tuition credits, tax credits, or new forms of community college would incentivize people to educate themselves? That includes people in their 50s, 60s, and increasingly people in their 70s and beyond.

Q: Nearly every era thinks the challenges it faces are different. Is this time different?

We all decide every day, as students, employees, as business and government leaders: are we seeing incremental or exponential and transformative change? Are you going to bet on marginal changes during the life of your career, or are you going to bet on the world changing quite significantly? Will all the jobs be taken by machines or will more new jobs be created in your life than we’ve seen in the last couple of thousand years? We’re all dealing with those questions every day.

I don’t have the answers, but I do have two daughters who are 23 and 25. I’m hopeful about what might be in front of them and what will be in front of our grandchildren. It’s going to be a wild ride. The things that we’re talking about, exponential technology, platforms, uncertainty driven by the interconnectedness of the global economy and global systems can make wonderful things happen, and there will also be real difficulties.

- Global Business

- Competitive Strategy

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Future of Work, Essay Example

Pages: 5

Words: 1450

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

The Future of Work

People spend a third of their adult lives working, which has led to many of them looking for ways to reimagine work. Since people have to work to guarantee their survival and wealth, methods of making work more flexible and comfortable are being developed, a phenomenon regarded as the future of work. The future of work will involve working in places with equity and inclusion. Many businesses are changing to accommodate a stress-free working environment. Company leaders are starting to establish a culture of trust in their organizations, which will allow them to become more transparent, compassionate, and acquiring more vulnerable management styles. This essay discusses the characteristics that will define a flexible and comfortable workplace and how workers are being prepared to adapt to the future of work.

Artificial Intelligence

Many fields of work, such as health and development of leadership are continuously growing, which has led to the experts in these fields to seek wellness and professional advice from technical experts to help in their work. Artificial Intelligence has replaced many jobs, as Massachusetts Institute of Technology predicted a decade ago, that by 2017, the 1.7 million trucking jobs will be replaced by Artificial Intelligence Systems (Wang 10).

Seeking Flexibility and Autonomous work

Self-employment, which started in the UK after there was a global crisis, was regarded as an alternative that people took because there was no employment. However, when jobs became available, and there was an improvement in the economy, self-employment rates also went up. People involuntarily became self-employed, because they wanted to work flexible, and any age and a pace where they did not require to be controlled. This is similar to the use of new digital platforms in the workplace. Many employers are seeking to improve their workplace by allowing people to work the way they want to work through the use of digital technology. However, this will also affect a certain amount of employees who will need to be terminated to give room for the digital platforms.

Distribution

In the 20 th and early 21 st century, most jobs involved people being in a physical location. However, in the modern world, there are tools and new approaches that have allowed work to be successfully executed with people distributed across many places, including continents apart. For instance, the company Automattic has 762 people from 68 countries, and they speak 81 different languages (Franck 442). The employees meet online because of the availability of transparency, which allows them to understand each other. Based on the development of teleworking and open-source software projects that have made distribution easier, many companies are seeking to do away with offices, allowing their workers to work from home offices or spaces where they can co-work. Employees will, therefore, become flexible and will save more money because of avoiding commuting costs. Through distribution, an organization can employ people with great talents, with the constraint of geographical location or language differences. An example of a company living in the future of work is the Linux Foundation, which has membership from more than 1000 companies all over the world. Linux Foundation meetings involve video conferencing and remote calendars. Team building is done daily, where workers communicate through emails, calls, forums, and other forms of technology.

Open employment

The future of work will not be traditionally-based, where people are hired in a company to work until they resign after getting new jobs. In the modern world, according to the 2016 Gallup Report, millennials like to job-hop from company to company, because they are always looking for new job opportunities in new companies (Hoffman 47). This has turned 57.3 million American youths into freelancers, which is 36% of the American workforce. This means that the percentage of youths to employ is decreasing, which has led companies to come up with new strategies for the future business market.

The future of work involves organizations being more fluid in their terms of employment. Many companies are hiring youth as part-time employees, independent contractors, advisors, and consultants. In the new work setting, there is a whole network of contract and part-time workers, working based on the needs of projects in an organization and coming to work based on their preferences. An example of a company that has already implemented this setting is the management consultancy company called SYPartners, which has both full and part-time employees, and the company has several freelancers. When the company has new projects, it hires people with expertise in the project in question, after which they are dismissed at the end of the project.

The appearance of Monopolistic Companies

The future of work will also involve people witnessing the emergence of big companies that will have better quality than the existing businesses, and the companies will appear to be operating in a monopolistic system. A large group of satisfied consumers then characterizes such companies. An example of a large company that has already dominated the market is Uber (Merkert 49). The main characteristic of these companies is to pop up in places where the traditional or the standard version of their work did not exist. For instance, taxis were rarely found in poor neighborhoods or areas where accommodation was not easily found. Uber, other than joining the car-ride business, has improved service quality and made traveling more flexible, rendering the traditional taxi business ineffective

Preparing the Workforce for the Future of Work

The future of work mostly involves the use of technology, whose adoption in organizations gives the workers a bleak future. Therefore, before preparing their workers for a shift from the standard work arrangement, organizations first convince their workers that technology will be a form of deliverance, helping them have a more productive, brighter future. Organizations convince their workers of the importance of the future of work to make them open towards what they will be taught about the changes in the Organization. Some of the ways that employees are prepared for the future of work are discussed below

Developing Leadership skills

The future of work will require workers to be aware of to be inspirers, regardless of whether they are leaders or not. In the future, these workers will be required to guide new workers in organizations. Many companies seek to develop leadership skills among the youth to prepare them for leadership positions at higher levels after the senior employees have retired.

The best approach in developing leadership skills is to allow employees to be leaders at any capacity, regardless of how minor it is. For example, they can be in charge of running company projects or welfare groups, where they help solve issues in the workplace. Practicing leadership skills will make them more confident, and eventually skilled enough to assume significant leadership roles.

Learning to use Technology

Embracing technology is in the future of work, which makes it compulsory for every worker to be well versed with technology. Employees at all levels are prepared to embrace technology by teaching them about communication, operations, and insight. The organization provides technological gadgets to employees, such as computers, where they are trained on how to send emails, make calls, and other common forms of technology within the company. Showing employees that technology is not a competition or their enemy will encourage them to learn, therefore making their work easier.

Create Continuous learning Opportunities

Evolving of employees will be required as technology changes. Organizations have to instill a growth mindset among their employees to create room for growing (Claro, David, and Carol 8665). Employees are encouraged to develop their skills and be more creative in their work. Hard work, new strategies, and input are some of the methods that employers use to improve the learning opportunities of the employees. Employees with a growth mindset can learn, feel more empowered, and committed in their work.

The future of work has people’s best interests, because they become more flexible, and they can work how they see comfortable. Workers can choose to be full or part-time employed, or they can work from home. The future of work does not only involve replacing human labor with technology, but also enhancing the skills of workers. If a worker loses their job because of technology, the skills that they learned from the organization will enable them to get employment at another skill level.

Works Cited

Claro, Susana, David Paunesku, and Carol S. Dweck. “Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113.31 (2016): 8664-8668.

Franck, Edwiygh. “Distributed Work Environments: The Impact of Technology in the Workplace.” Handbook of Research on Human Development in the Digital Age . IGI Global, 2018. 427-448.

Hoffman, Blaire. “Why Millennials Quit.” Journal of Property Management 83.3 (2018): 42-45.

Merkert, Eugene. “Antitrust vs. Monopoly: An Uber Disruption.” FAU Undergraduate Law Journal 2 (2015): 49.

Wang, Fei-Yue. “Toward a revolution in transportation operations: AI for complex systems.” IEEE Intelligent Systems 23.6 (2008): 8-13.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Nudge: Improving Decisions, Book Review Example

Introduction to Communication, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

Deeper Thinking On Work

My writing is an ongoing "conversation" with the ideas that matter to me. Currently writing about: the history of work, unleashing our creative potential, gift economy and books I read. I don't see anything I've written as "finished" so let me know what you think?

Get Started — 14 days FREE!

No credit card required, cancel anytime, no contracts.

Error: Contact form not found.

Who I Write For

- I might not be writing for you

- Experiments In The Gift Economy

- Burning Out At Age 32

- Beanie Baby Curiosity

- Ten Most Surprising Benefits of Self-Employment

- My Awakening: Quitting the Default Path

- Getting Rejected And Landing My Dream Job @ McKinsey

- Decoding High-Performance at McKinsey & Company

- Finding My Passion, My Journey To Unlock My Purpose

Carve Your Own Path

- The 10 "Hustle Traps" to avoid on the creative path

- The New Economy: Tech, Finance, or SOL

- Learn The Game, Don't Become The Game

- Unlocking The Second Chapter Of Success

- Navigating the Pathless Path: Four Stages of the Journey

- Reinvention: 5 Ways To Reinvent Yourself For The Future

- Finding the types of "Prestige" that you actually want

- Beyond Work Sucks: How To Actually Take Action

- The Other Side Of Rest: Taking A Break To Find What Matters

- 10 Career Myths We Should Stop Believing

- The Simple Guide For Starting a Podcast

- Career Transition Playbook

Organizations

- Maslow Didn't Invent The Pyramid

- Deep Dive into Edgar Schein's Theory of Organizational Culture

- The REAL Dark Side Of Consulting: Why Consulting Is A Symptom and Not A Problem

- Chaos Theory: How Companies Can Use Complexity Science To Build Better Futures

- Crisis At Work: Six Reasons Organizations Fail To Unleash Human Potential

- My Reflections On Why McKinsey & Company Is So Successful

Remote Work

- The Ultimate Guide to Becoming a Digital Nomad

- Five Levels Of Remote Work

- Non-Obvious Remote Working Tips

- Facilitating Virtual Sessions

- Interviews: CEO, Doist , CEO, Zapier , Consultant Laurel Farer

Future (History) Of Work

- The emergence of the knowledge worker mind

- Hamsternomics: Rethinking Our Fundamental Economic Future

- Boomer Blockade: How One Generation Reshaped Work

- The Nine Modern School Of Work That Shape Our Beliefs

- It's Time To Retire The Idea of a Steady Career Trajectory

- The Four Day Workweek Is Not About Working Less

- The *Five* Future Of Work Conversations

- Questioning Work: The Unintended Consequences of "Work"

- The Future of Work Mindset Shift

- The Future of Work: What Winning Orgs Will Look Like in 2025

Freelancing & Talent Platforms

- Failed Promise Of Freelance Talent Platforms

- Freelance Consultant Playbook

- Ultimate Guide To Talent Platforms

- Review of Aspiration by Agnes Callard

- Review of Alex Pang's Book Rest

- Review Of "Black Mass" On The Dangers Of Utopia

- All The Things Worth Reading In 2018 (175+ Links)

- John Maynard Keynes Famous 1930's essay "Dreams For My Grandchildren"

- Twelve Lessons From Adam Grant's Originals

- Bullshit Jobs PowerPoint Book Review

2023 Annual Review: New Additions, New Heights & Open Questions

Living Intentionally After “Enough” – Bilal Zaidi on leaving Google, emigrating to the US, the intensity of New York, writing poetry and spoken word, and travel vs. vacations (Pathless Path Podcast)

How To Take A Sabbatical: Stories From Five People Who Took Them

From Rugby to Writer & Book Influencer: How Ben Mercer Reinvented Himself

Ali Abdaal on Identity, Prestige, Quitting Medicine | The Pathless Path Podcast

Kyla Scanlon on the Passion Crisis, Vibecession, and Quitting Her Job To Bet On Herself | The Pathless Path Podcast

Aida Alston: College at 16, Med School in Cuba & Starting Over After Kids | The Pathless Path Podcast

Die With Zero: Why Too Many Save Too Much for Too Late In Their Lives (Book Review)

Luke Burgis on Mimetic Desire, The Three City Problem & Academia | The Pathless Path Podcast

AI, automation, and the future of work: Ten things to solve for

Automation and artificial intelligence (AI) are transforming businesses and will contribute to economic growth via contributions to productivity. They will also help address “moonshot” societal challenges in areas from health to climate change.

Stay current on your favorite topics

At the same time, these technologies will transform the nature of work and the workplace itself. Machines will be able to carry out more of the tasks done by humans, complement the work that humans do, and even perform some tasks that go beyond what humans can do. As a result, some occupations will decline, others will grow, and many more will change.

While we believe there will be enough work to go around (barring extreme scenarios), society will need to grapple with significant workforce transitions and dislocation. Workers will need to acquire new skills and adapt to the increasingly capable machines alongside them in the workplace. They may have to move from declining occupations to growing and, in some cases, new occupations.

This executive briefing, which draws on the latest research from the McKinsey Global Institute, examines both the promise and the challenge of automation and AI in the workplace and outlines some of the critical issues that policy makers, companies, and individuals will need to solve for.

Accelerating progress in AI and automation is creating opportunities for businesses, the economy, and society

How ai and automation will affect work, key workforce transitions and challenges, ten things to solve for.

Automation and AI are not new, but recent technological progress is pushing the frontier of what machines can do. Our research suggests that society needs these improvements to provide value for businesses, contribute to economic growth, and make once unimaginable progress on some of our most difficult societal challenges. In summary:

Rapid technological progress

Beyond traditional industrial automation and advanced robots, new generations of more capable autonomous systems are appearing in environments ranging from autonomous vehicles on roads to automated check-outs in grocery stores. Much of this progress has been driven by improvements in systems and components, including mechanics, sensors and software. AI has made especially large strides in recent years, as machine-learning algorithms have become more sophisticated and made use of huge increases in computing power and of the exponential growth in data available to train them. Spectacular breakthroughs are making headlines, many involving beyond-human capabilities in computer vision, natural language processing, and complex games such as Go.

Potential to transform businesses and contribute to economic growth

These technologies are already generating value in various products and services, and companies across sectors use them in an array of processes to personalize product recommendations, find anomalies in production, identify fraudulent transactions, and more. The latest generation of AI advances, including techniques that address classification, estimation, and clustering problems, promises significantly more value still. An analysis we conducted of several hundred AI use cases found that the most advanced deep learning techniques deploying artificial neural networks could account for as much as $3.5 trillion to $5.8 trillion in annual value, or 40 percent of the value created by all analytics techniques (Exhibit 1).

Deployment of AI and automation technologies can do much to lift the global economy and increase global prosperity, at a time when aging and falling birth rates are acting as a drag on growth. Labor productivity growth, a key driver of economic growth, has slowed in many economies, dropping to an average of 0.5 percent in 2010–2014 from 2.4 percent a decade earlier in the United States and major European economies, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis after a previous productivity boom had waned. AI and automation have the potential to reverse that decline: productivity growth could potentially reach 2 percent annually over the next decade, with 60 percent of this increase from digital opportunities.

Potential to help tackle several societal moonshot challenges

AI is also being used in areas ranging from material science to medical research and climate science. Application of the technologies in these and other disciplines could help tackle societal moonshot challenges. For example, researchers at Geisinger have developed an algorithm that could reduce diagnostic times for intracranial hemorrhaging by up to 96 percent. Researchers at George Washington University, meanwhile, are using machine learning to more accurately weight the climate models used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Challenges remain before these technologies can live up to their potential for the good of the economy and society everywhere

AI and automation still face challenges. The limitations are partly technical, such as the need for massive training data and difficulties “generalizing” algorithms across use cases. Recent innovations are just starting to address these issues. Other challenges are in the use of AI techniques. For example, explaining decisions made by machine learning algorithms is technically challenging, which particularly matters for use cases involving financial lending or legal applications. Potential bias in the training data and algorithms, as well as data privacy, malicious use, and security are all issues that must be addressed . Europe is leading with the new General Data Protection Regulation, which codifies more rights for users over data collection and usage.

A different sort of challenge concerns the ability of organizations to adopt these technologies, where people, data availability, technology, and process readiness often make it difficult. Adoption is already uneven across sectors and countries. The finance, automotive, and telecommunications sectors lead AI adoption. Among countries, US investment in AI ranked first at $15 billion to $23 billion in 2016, followed by Asia’s investments of $8 billion to $12 billion, with Europe lagging behind at $3 billion to $4 billion.

Even as AI and automation bring benefits to business and society, we will need to prepare for major disruptions to work.

About half of the activities (not jobs) carried out by workers could be automated

Our analysis of more than 2000 work activities across more than 800 occupations shows that certain categories of activities are more easily automatable than others. They include physical activities in highly predictable and structured environments, as well as data collection and data processing. These account for roughly half of the activities that people do across all sectors. The least susceptible categories include managing others, providing expertise, and interfacing with stakeholders.

Nearly all occupations will be affected by automation, but only about 5 percent of occupations could be fully automated by currently demonstrated technologies. Many more occupations have portions of their constituent activities that are automatable: we find that about 30 percent of the activities in 60 percent of all occupations could be automated. This means that most workers—from welders to mortgage brokers to CEOs—will work alongside rapidly evolving machines. The nature of these occupations will likely change as a result.

Would you like to learn more about the McKinsey Global Institute ?

Jobs lost: some occupations will see significant declines by 2030.

Automation will displace some workers. We have found that around 15 percent of the global workforce , or about 400 million workers, could be displaced by automation in the period 2016–2030. This reflects our midpoint scenario in projecting the pace and scope of adoption. Under the fastest scenario we have modeled, that figure rises to 30 percent, or 800 million workers. In our slowest adoption scenario, only about 10 million people would be displaced, close to zero percent of the global workforce (Exhibit 2).

The wide range underscores the multiple factors that will impact the pace and scope of AI and automation adoption. Technical feasibility of automation is only the first influencing factor. Other factors include the cost of deployment; labor-market dynamics, including labor-supply quantity, quality, and the associated wages; the benefits beyond labor substitution that contribute to business cases for adoption; and, finally, social norms and acceptance. Adoption will continue to vary significantly across countries and sectors because of differences in the above factors, especially labor-market dynamics: in advanced economies with relatively high wage levels, such as France, Japan, and the United States, automation could displace 20 to 25 percent of the workforce by 2030, in a midpoint adoption scenario, more than double the rate in India.

Jobs gained: In the same period, jobs will also be created

Even as workers are displaced, there will be growth in demand for work and consequently jobs. We developed scenarios for labor demand to 2030 from several catalysts of demand for work, including rising incomes, increased spending on healthcare, and continuing or stepped-up investment in infrastructure, energy, and technology development and deployment. These scenarios showed a range of additional labor demand of between 21 percent to 33 percent of the global workforce (555 million and 890 million jobs) to 2030, more than offsetting the numbers of jobs lost. Some of the largest gains will be in emerging economies such as India, where the working-age population is already growing rapidly.

Additional economic growth, including from business dynamism and rising productivity growth, will also continue to create jobs. Many other new occupations that we cannot currently imagine will also emerge and may account for as much as 10 percent of jobs created by 2030, if history is a guide . Moreover, technology itself has historically been a net job creator. For example, the introduction of the personal computer in the 1970s and 1980s created millions of jobs not just for semiconductor makers, but also for software and app developers of all types, customer-service representatives, and information analysts.

Jobs changed: More jobs than those lost or gained will be changed as machines complement human labor in the workplace

Partial automation will become more prevalent as machines complement human labor. For example, AI algorithms that can read diagnostic scans with a high degree of accuracy will help doctors diagnose patient cases and identify suitable treatment. In other fields, jobs with repetitive tasks could shift toward a model of managing and troubleshooting automated systems. At retailer Amazon, employees who previously lifted and stacked objects are becoming robot operators, monitoring the automated arms and resolving issues such as an interruption in the flow of objects.

While we expect there will be enough work to ensure full employment in 2030 based on most of our scenarios, the transitions that will accompany automation and AI adoption will be significant. The mix of occupations will change, as will skill and educational requirements. Work will need to be redesigned to ensure that humans work alongside machines most effectively.

Workers will need different skills to thrive in the workplace of the future

Automation will accelerate the shift in required workforce skills we have seen over the past 15 years. Demand for advanced technological skills such as programming will grow rapidly. Social, emotional, and higher cognitive skills, such as creativity, critical thinking, and complex information processing, will also see growing demand. Basic digital skills demand has been increasing and that trend will continue and accelerate. Demand for physical and manual skills will decline but will remain the single largest category of workforce skills in 2030 in many countries (Exhibit 3). This will put additional pressure on the already existing workforce-skills challenge, as well as the need for new credentialing systems. While some innovative solutions are emerging, solutions that can match the scale of the challenge will be needed.

Many workers will likely need to change occupations

Our research suggests that, in a midpoint scenario, around 3 percent of the global workforce will need to change occupational categories by 2030, though scenarios range from about 0 to 14 percent. Some of these shifts will happen within companies and sectors, but many will occur across sectors and even geographies. Occupations made up of physical activities in highly structured environments or in data processing or collection will see declines. Growing occupations will include those with difficult to automate activities such as managers, and those in unpredictable physical environments such as plumbers. Other occupations that will see increasing demand for work include teachers, nursing aides, and tech and other professionals.

Workplaces and workflows will change as more people work alongside machines

As intelligent machines and software are integrated more deeply into the workplace, workflows and workspaces will continue to evolve to enable humans and machines to work together. As self-checkout machines are introduced in stores, for example, cashiers can become checkout assistance helpers, who can help answer questions or troubleshoot the machines. More system-level solutions will prompt rethinking of the entire workflow and workspace. Warehouse design may change significantly as some portions are designed to accommodate primarily robots and others to facilitate safe human-machine interaction.

Skill shift: Automation and the future of the workforce

Automation will likely put pressure on average wages in advanced economies.

The occupational mix shifts will likely put pressure on wages. Many of the current middle-wage jobs in advanced economies are dominated by highly automatable activities, such as in manufacturing or in accounting, which are likely to decline. High-wage jobs will grow significantly, especially for high-skill medical and tech or other professionals, but a large portion of jobs expected to be created, including teachers and nursing aides, typically have lower wage structures. The risk is that automation could exacerbate wage polarization, income inequality, and the lack of income advancement that has characterized the past decade across advanced economies, stoking social, and political tensions.

In the face of these looming challenges, workforce challenges already exist

Most countries already face the challenge of adequately educating and training their workforces to meet the current requirements of employers. Across the OECD, spending on worker education and training has been declining over the last two decades. Spending on worker transition and dislocation assistance has also continued to shrink as a percentage of GDP. One lesson of the past decade is that while globalization may have benefited economic growth and people as consumers, the wage and dislocation effects on workers were not adequately addressed. Most analyses, including our own, suggest that the scale of these issues is likely to grow in the coming decades. We have also seen in the past that large-scale workforce transitions can have a lasting effect on wages; during the 19th century Industrial Revolution, wages in the United Kingdom remained stagnant for about half a century despite rising productivity—a phenomenon known as “ Engels’ Pause ,” (PDF–690KB) after the German philosopher who identified it.

In the search for appropriate measures and policies to address these challenges, we should not seek to roll back or slow diffusion of the technologies. Companies and governments should harness automation and AI to benefit from the enhanced performance and productivity contributions as well as the societal benefits. These technologies will create the economic surpluses that will help societies manage workforce transitions. Rather, the focus should be on ways to ensure that the workforce transitions are as smooth as possible. This is likely to require actionable and scalable solutions in several key areas:

- Ensuring robust economic and productivity growth . Strong growth is not the magic answer for all the challenges posed by automation, but it is a prerequisite for job growth and increasing prosperity. Productivity growth is a key contributor to economic growth. Therefore, unlocking investment and demand, as well as embracing automation for its productivity contributions, is critical.

- Fostering business dynamism . Entrepreneurship and more rapid new business formation will not only boost productivity, but also drive job creation. A vibrant environment for small businesses as well as a competitive environment for large business fosters business dynamism and, with it, job growth. Accelerating the rate of new business formation and the growth and competitiveness of businesses, large and small, will require simpler and evolved regulations, tax and other incentives.

- Evolving education systems and learning for a changed workplace . Policy makers working with education providers (traditional and nontraditional) and employers themselves could do more to improve basic STEM skills through the school systems and improved on-the-job training. A new emphasis is needed on creativity, critical and systems thinking, and adaptive and life-long learning. There will need to be solutions at scale.

- Investing in human capital . Reversing the trend of low, and in some countries, declining public investment in worker training is critical. Through tax benefits and other incentives, policy makers can encourage companies to invest in human capital, including job creation, learning and capability building, and wage growth, similar to incentives for private sector to invest in other types of capital including R&D.

- Improving labor-market dynamism . Information signals that enable matching of workers to work, credentialing, could all work better in most economies. Digital platforms can also help match people with jobs and restore vibrancy to the labor market. When more people change jobs, even within a company, evidence suggests that wages rise . As more varieties of work and income-earning opportunities emerge including the gig economy , we will need to solve for issues such as portability of benefits, worker classification, and wage variability.

- Redesigning work . Workflow design and workspace design will need to adapt to a new era in which people work more closely with machines. This is both an opportunity and a challenge, in terms of creating a safe and productive environment. Organizations are changing too, as work becomes more collaborative and companies seek to become increasingly agile and nonhierarchical.

- Rethinking incomes . If automation (full or partial) does result in a significant reduction in employment and/or greater pressure on wages, some ideas such as conditional transfers, support for mobility, universal basic income, and adapted social safety nets could be considered and tested. The key will be to find solutions that are economically viable and incorporate the multiple roles that work plays for workers, including providing not only income, but also meaning, purpose, and dignity.

- Rethinking transition support and safety nets for workers affected . As work evolves at higher rates of change between sectors, locations, activities, and skill requirements, many workers will need assistance adjusting. Many best practice approaches to transition safety nets are available, and should be adopted and adapted, while new approaches should be considered and tested.

- Investing in drivers of demand for work . Governments will need to consider stepping up investments that are beneficial in their own right and will also contribute to demand for work (for example, infrastructure, climate-change adaptation). These types of jobs, from construction to rewiring buildings and installing solar panels, are often middle-wage jobs, those most affected by automation.

- Embracing AI and automation safely . Even as we capture the productivity benefits of these rapidly evolving technologies, we need to actively guard against the risks and mitigate any dangers. The use of data must always take into account concerns including data security, privacy, malicious use, and potential issues of bias, issues that policy makers, tech and other firms, and individuals will need to find effective ways to address.

There is work for everyone today and there will be work for everyone tomorrow, even in a future with automation. Yet that work will be different, requiring new skills, and a far greater adaptability of the workforce than we have seen. Training and retraining both midcareer workers and new generations for the coming challenges will be an imperative. Government, private-sector leaders, and innovators all need to work together to better coordinate public and private initiatives, including creating the right incentives to invest more in human capital. The future with automation and AI will be challenging, but a much richer one if we harness the technologies with aplomb—and mitigate the negative effects.

James Manyika is chairman and director of the McKinsey Global Institute and a senior partner at McKinsey & Company based in San Francisco. Kevin Sneader is McKinsey’s global managing partner-elect, based in Hong Kong.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Notes from the AI frontier: Applications and value of deep learning

Jobs lost, jobs gained: What the future of work will mean for jobs, skills, and wages

AI: 3 ways artificial intelligence is changing the future of work

Artificial intelligence (AI) will revolutionize the future of work. Image: Getty Images/iStockphoto

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Mark Rayner

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Artificial Intelligence is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, jobs and skills.

Listen to the article

- Artificial intelligence (AI) has dominated the business agenda since chatbot ChatGPT burst on to the scene in late 2022.

- Generative AI is estimated to eventually automate millions of jobs, but its employment benefits are harder to quantify.

- Here are three ways that artificial intelligence will change the future of work, and why its likely to augment rather than automate.

Since ChatGPT burst on to the scene in November 2022, generative artificial intelligence (AI) has come to dominate the business agenda.

Boosts of a few percentage points in productivity are weighed against labour-market disruptions, with Goldman Sachs estimating that generative AI will eventually automate 300 million of today’s jobs .

Have you read?

The future of jobs report 2023.

The employment benefits of generative AI are harder to quantify, but the Future of Jobs report’s cohort of 800 global business leaders is well placed to shed light on the future.

Here are three ways that AI will change the future of work:

1. AI will drive job creation

Businesses responding to our survey expect artificial intelligence to be a net job creator in the coming five years. Nearly half (49%) of companies expect adopting AI to create jobs, well ahead of the 23% of respondents who expect it to displace jobs.

The ranks of AI-linked roles such as data scientists, big data specialists and business intelligence analysts are expected to swell by 30 to 35%, with growth nearer 45% in companies operating in China.