An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Risk Factors for Gambling Disorder: A Systematic Review

Diana moreira.

1 Centro de Solidariedade de Braga/Projecto Homem, Braga, Portugal

2 Faculty of Philosophy and Social Sciences, Centre for Philosophical and Humanistic Studies, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Rua de Camões, 60, 4710-362 Braga, Portugal

3 Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Laboratory of Neuropsychophysiology, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

4 Institute of Psychology and Neuropsychology of Porto – IPNP Health, Porto, Portugal

Andreia Azeredo

Gambling disorder is a common and problematic behavioral disorder associated with depression, substance abuse, domestic violence, bankruptcy, and high suicide rates. In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), pathological gambling was renamed “gambling disorder” and moved to the Substance-Related and Addiction Disorders chapter to acknowledge that research suggests that pathological gambling and alcohol and drug addiction are related. Therefore, this paper provides a systematic review of risk factors for gambling disorder. Systematic searches of EBSCO, PubMed, and Web of Science identified 33 records that met study inclusion criteria. A revised study acknowledges as risk factors for developing/maintaining a gambling disorder being a single young male, or married for less than 5 years, living alone, having a poor education, and struggling financially.

For most people, gambling is just an infrequent leisure activity that does not put their lives in danger (Wood & Griffiths, 2015 ). However, for a small rate of the world population, approximately between 0.12 and 5.8% (Calado & Griffiths, 2016 ), pathological gambling (PG) is a behavioral disorder. This disorder is defined as an inability to control gambling behavior itself (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013 ), leading to serious health consequences, and financial and legal problems, and representing a risk factor for aggressive behavior (Black, 2022 ). In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), PG was renamed Gambling Disorder and moved to the Substance-Related and Addiction Disorders chapter to acknowledge that PG is associated with alcohol and drug addiction (Black & Grant, 2014 ).

Custer ( 1985 ) describes PG as a multistage disease with different stages of gain, loss, and distress, while the DSM-5 (APA, 2013 ) describes PG as chronic and progressive. Recent work has shown that PG’s progression is more nuanced and, for most, has its ups and downs. Most players gradually shifted to lower levels of gaming activity, and most experienced spontaneous periods of remission. Research also shows that people who gamble recreationally (or do not gamble at all) are less likely to develop more rigorous levels of gambling activity. Still, some at-risk individuals may experience stressors that push them toward a gambling addiction (Black et al., 2017 ; LaPlante et al., 2008 ).

Despite the social and economic toll, there is very little data on predictors of PG progression. Follow-up studies are often small, underpowered, and consist primarily of treatment samples. For example, Hodgins and Peden ( 2005 ) re-interviewed 40 PG patients after an average of 40 months. Most tried to stop or reduce gambling, but more than 80% remained problem gamblers. The presence of emotional or substance use disorders was associated with poorer outcomes. Goudriaan et al. ( 2008 ) compared 24 PG patients who attended a treatment center with 22 who did not and found that relapsed patients performed worse on disinhibition and decision-making measures. Furthermore, Oei and Gordon ( 2008 ) assessed 75 Australian Gamblers Anonymous attendees to assess psychosocial predictors of abstinence and relapse. Those achieving abstinence were more involved in Gamblers Anonymous and reported better social support. More recently, research has investigated the course of gambling disorder in a sample of the general population. In the Quinte study of gambling and problem gambling, Williams et al. ( 2015 ) followed 4,121 randomly selected adults for 5 years to assess problematic behavior. They found that being a current problem gambler was the best predictor of future problem gambling. Experiencing “big wins” was also a strong predictor, as was greater gambling intensity.

Several studies have shown a high prevalence of personality disorder (PD) among those with PG, many of which focusing on the association between antisocial personality disorder and gambling (Pietrzak & Petry, 2005 ; Slutske et al., 2001 ). On the other hand, Steel and Blaszczynski ( 1998 ) observed that almost 53% of pathological gamblers have non-antisocial personality disorder. Other research papers have looked at the co-morbidity of PG with other PD. A recent meta-analysis highlighted that almost half of pathological gamblers show diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder. The majority of these were Cluster B disorders, such as borderline personality disorder, histrionic personality disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder. Other studies looked at comorbidity between PG and disorders from other clusters. There is a consistent comorbidity between PG and paranoid and schizoid personality disorders in Cluster A and with avoidant and obsessive–compulsive personality disorder in Cluster C.

Furthermore, several studies have focused on the overlap between gambling and substance use and have consistently observed significant positive associations between gambling, problem gambling, and alcohol use (Bhullar et al., 2012 ; Engwall et al., 2004 ; Goudriaan et al., 2009 ; Huang et al., 2011 ; LaBrie et al., 2003 ; Martens et al., 2009 ; Martin et al., 2014 ; Stuhldreher et al., 2007 ; Vitaro et al., 2001 ). Gambling is also significantly and positively associated with marijuana and other drug use (Engwall et al., 2004 ; Goudriaan et al., 2009 ; Huang et al., 2011 ; LaBrie et al., 2003 ; Lynch et al., 2004 ; Stuhldreher et al., 2007 ).

The concept of risk implies the concept of hazard and is associated with a high probability of adverse outcomes (Lupton, 1999 ). That is, risk exposes people to danger and potentially harmful consequences (Werner, 1993 ). However, risk varies throughout life: it varies according to life circumstances and varies from individual to individual (Cowan et al., 1996 ). Based on a literature review, Ciarrocchi ( 2001 ) described the following risk factors: age, gender, and family background. Pathological gamblers frequently gambled from an early age, suggesting that youth is a risk factor for problem gambling. Also, they are usually male and have relatives who are pathological gamblers (e.g., Cavalera et al., 2018). Regarding family background, some studies have found close relatives with gambling problems, especially parents, to be risk factors for gambling disorder (e.g., Vachon et al, 2004 ). Kessler et al. ( 2008 ) describe several risk factors for gambling disorder: male sex, low educational and socioeconomic levels, and unemployment. After a literature review, Johansson et al., ( 2009a , 2009b ) found that the following groups of risk factors were most frequently reported: (1) demographic variables (under 29; male); (2) cognitive distortions (misperception, illusion of control); (3) sensory characteristics (e.g., (4) reinforcement programs (e.g., operant conditioning); (5) delinquency (e.g., illegal behavior). Regarding older adults, Subramaniam et al. ( 2015 ) conducted a study of gamblers aged 60 or older and found that pathological gamblers were more likely to be single or divorced/separated and gambled to improve their emotional state compared to a control group and to compensate for their inability to perform activities of which they were previously capable.

Additionally, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19 pandemic) forced governments to adopt measures such as staying at home and practicing social distancing (Mazza et al., 2020 ). More adverse measures were also implemented, such as general or regional lockdowns. These stringent measures, associated with reduced social support, economic crises and unemployment, fear of the disease, increased time with the partner and reduced availability of health services, can significantly contribute to the increase of stress in an already strenuous relationship, precipitating or exacerbating gambling problems (Economou et al., 2019 ; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2014 ; Olason et al., 2017 ). In fact, historically, in economic crises, when people experienced stress due to, for example, isolation, gambling activity per se increased, and so did gambling problems (Economou et al., 2019 ; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2014 ; Olason et al., 2017 ), but recent studies on potential changes in gambling activity during the COVID-19 pandemic have reported different changes in behavior (Brodeur et al., 2021 ). One possible explanation might be the restrictions in place in the field of study, along with differences in study populations. Auer et al. ( 2020 ) and Lindner et al., ( 2020 ) found a substantial decrease in overall gambling activity, especially in gambling, where there were far fewer betting opportunities because of cancelled or postponed sports events such as football leagues.

Many studies have been dedicated to studying risk factors for the development/maintenance of gambling disorder. However, no study has systematically reviewed them to compile them. Therefore, this systematic review aims to explore what are the risk factors for the development/maintenance of gambling disorder. Particularly important if you can see a difference in the pattern between the pre-pandemic and the pandemic crisis.

Search Strategy

Studies were identified through search on EBSCO, PubMed, and Web of Science. The reference lists of the selected studies were also reviewed to identify other relevant studies (manual searching). The search equation in EBSCO was:

TI (gambling).

AND TI (“contributing factor*”

OR predictor*

OR caus*

OR vulnerabilit*

OR outcome*

OR chang*

OR barrier*

OR risk

OR seek*

OR treatment*).

(gambling[Title]).

AND (“contributing factor*”[Title].

OR predictor*[Title]

OR caus*[Title]

OR vulnerabilit*[Title]

OR outcome*[Title]

OR chang*[Title]

OR barrier*[Title]

OR risk[Title]

OR seek*[Title]

OR treatment*[Title]).

And in Web of Science:

(TI = (gambling)).

AND TI=(“contributing factor*”

The search was limited from the year 2016 and linguistic factors (Portuguese, English, Spanish, or French).

Study Selection

We had four inclusion criteria and built four corresponding exclusion criteria in response. We wanted population over 18 years old, so we excluded children and teenagers. We wanted only empirical studies, so we excluded all case studies, book chapters, theoretical essays, and systematic reviews (with or without meta-analyses). We only wanted studies involving problem or pathological gambling, so we excluded studies that did not include either of those two. Also, we wanted studies involving risk factors associated with gambling problems, so we excluded studies that did not include it. And we only wanted studies published in the last 6 years (since 2016), so we excluded the others.

The studies were selected by two independent reviewers (DM and AA), based on their titles and abstracts, according to recommendations of PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009 ).

The agreement index in the study selection process was assessed with Cohen’s Kappa and revealed almost perfect agreement, K = 0.98, p < 0.001 (Landis & Koch, 1977 ). The disagreements among reviewers were discussed and resolved by consensus.

Identification and Screening

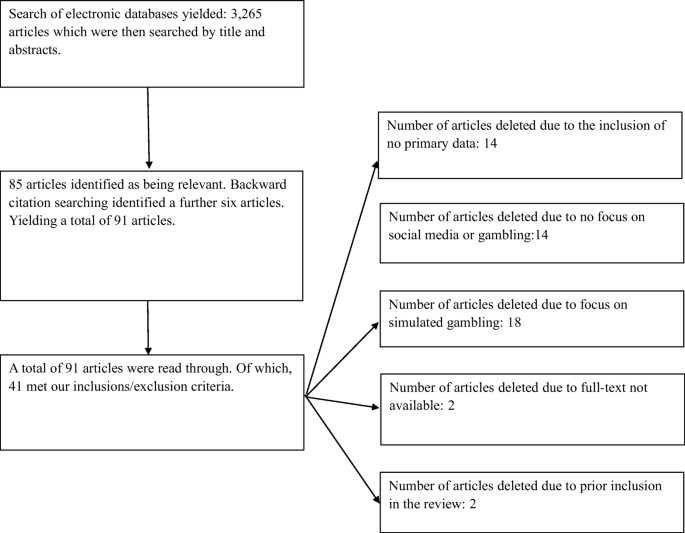

Our database searches have retrieved 1,294 studies published between 2016 and 2023. After removing duplicates, the search outcome was reduced to to 629 unique studies. Afterwards, we examined the abstracts and excluded another 498 articles based on wrong publication type ( n = 73), wrong theme ( n = 335), wrong population ( n = 72), or wrong outcome variable ( n = 18). After full text analysis, 105 articles were eliminated, based the following criteria: wrong publication type ( n = 13), wrong theme ( n = 8), wrong population ( n = 27), wrong outcome variable ( n = 57) (Fig. 1 ). A total of 33 articles were included (seven from manual searching and 26 from the three databases). The objectives, sample ( N , age, % male), and conclusions were extracted from each study.

Flowchart of literature review process

Several studies have indicated different risk factors associated with gambling problems. At personal level, gender differences are clear and are mostly men the high-risk gamblers (Çakıcı et al., 2015 ; Çakıcı et al., 2021 ; Cunha et al., 2017 ; De Pasquale et al., 2018 ; Hing et al., 2016b ; Hing & Russell, 2020 ; Volberg et al., 2017 ), young and single (Buth et al., 2017 ; Çakıcı et al., 2015 ; Çakıcı et al., 2021 ; Hing et al., 2016a ; Hing et al., 2016b ; Hing & Russell, 2020 ; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2020 ; Volberg et al., 2017 ). These gamblers live alone and have been married less than 5 years (Çakıcı et al., 2021 ). In terms of education, they tend to be more educated (Buth et al., 2017 ; Çakıcı et al., 2015 ; Çakıcı et al., 2021 ; Hing et al., 2016a ; Hing et al., 2016b ; Hing & Russell, 2020 ; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2020 ; Volberg et al., 2017 ), despite some studies relate to a low level of formal education (Buth et al., 2017 ; Cavalera et al., 2017 ; Cunha et al., 2017 ; Hing et al., 2016a ; Volberg et al., 2017 ). In terms of occupation, studies found high-risk gamblers are working or studying full-time (Buth et al., 2017 ; Çakıcı et al., 2015 ; Çakıcı et al., 2021 ; Hing et al., 2016b ; Hing & Russell, 2020 ; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2020 ; Volberg et al., 2017 ), or unemployed (Hing et al., 2016a ), have financial difficulties (Cowlishaw et al., 2016 ). At familiar level, usually grew up either in a single-parent home or with parents who had addiction issues (Buth et al., 2017 ; Cavalera et al., 2017 ). However, a study by Browne et al. ( 2019 ) sought to measure and assess 25 known risk factors for gambling-related harm. It concluded that sociodemographic risk factors did not demonstrate a direct role in the development of gambling harm, when other factors were controlled (Browne et al., 2019 ) (Table (Table1 1 ).

Summary of Studies Characteristics

Physical and mental health are affected by gambling disorder (Black & Allen, 2021 ; Butler et al., 2019 ; Buth et al., 2017 ; Cowlishaw et al., 2016 ; Dennis et al., 2017 ), related to both psychiatric comorbidities (Bergamini, 2018 ), such as depression (Black & Allen, 2021 ; Dufour et al., 2019 ; Landreat et al., 2020 ; Rodriguez-Monguio et al., 2017 ; Volberg et al., 2017 ), anxiety (Landreat et al., 2020 ; Medeiros et al., 2016 ; Rodriguez-Monguio et al., 2017 ), and mood disorders (Rodriguez-Monguio et al., 2017 ), and substance use disorders (Bergamini, 2018 ; Cowlishaw et al., 2016 ; Rodriguez-Monguio et al., 2017 ; Wong et al., 2017 ), including excessive alcohol consumption (Browne et al., 2019 ; Hing & Russell, 2020 ). However, another study found that troublesome gambling and several of its mental health correlates—depression, anxiety, and stress—were not associated with troubling video game use (Biegun et al., 2020 ).

Regarding psychological risk factors, impulsivity was a significant risk factor (Browne et al., 2019 ; Dufour et al., 2019 ; Flórez et al., 2016 ; Gori et al., 2021 ; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2020 ), demonstrating that active gamblers have more cognitive impulsivity and explicit gambling cognition than inactive gamblers. Also, Wong et al. ( 2017 ) found that negative psychological states (i.e., stress) significantly moderated the relationship between gambling cognitions and gambling severity. Participants who reported a higher level of stress had more stable and serious gambling problems than those who reported a lower level of stress, regardless of their level of gambling-related cognitions (Black & Allen, 2021 ; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2020 ; Wong et al., 2017 ). Pathological gambling risk was positively correlated with dissociative experiences: depersonalization and derealization, absorption and imaginative involvement, and passive influence (De Pasquale et al., 2018 ). Also, alexithymia increases the risk of developing a gambling disorder (Bibby & Ross, 2017 ; Gori et al., 2021 ), and mediates the association between insecure attachment and dissociation (Gori et al., 2021 ). The results show a clear difference for the loss-chasing behavior (Bibby & Ross, 2017 ).

The analysis of gambling characteristics identified three distinct clinical traits of the gamblers: early and short-term onset (EOSC) (group 1), early and long-term onset (EOLC) (group 2), and late and short-term onset (LOSC) (Group 3) (Landreat et al., 2020 ). The incidence of gambling problems and the severity of gambling were higher in the EOSC group than in the other two groups. However, the onset age does not explain the gambling trajectories alone: the two clusters associated with the early onset age showed two distinct gambling trajectories, either a short-term evolution (~ 10 years) or a long-term evolution of the cluster. EOSC (~ 23 years) for the EOLC cluster. The EOLC cluster has a long history of gambling (35.4 years), they spend most money on gambling, with only 53.6% stopping gambling for at least a month. This cluster has a significantly higher preference for online gambling than other clusters. Although EOLC gamblers lived with their partners in most of the cases, they reported the lowest levels of family and social support related to gambling problems. An important feature was the absence of premorbid features of lifelong psychopathology before the onset of gambling problems. Most of LOSC gamblers preferred “pure” gambling (here understood as mere games of chance, as opposed to games that combine skill and chance). Women constituted the majority of the LOSC cluster, where game trajectories were the shortest observed in the study (Landreat et al., 2020 ).

Pathological gambling increases with the frequency (Cavalera et al., 2017 ; Hing et al., 2016b ; Hing & Russell, 2020 ) and the diversity of the games (Cavalera et al., 2017 ; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2020 ). Pathological gamblers engaged in a higher range of games of chance, and showed more impulsive responses towards gambling opportunities, including betting on live action games, individual bets, electronic gaming machines, scratch cards or bingo, table games, racing, sports or lotteries and winning non-social games (Hing et al., 2016a ).

Furthermore, the main proximal predictors for high-risk gambling in electronic gaming machines (EGM) are higher desires, higher levels of misperceptions, higher session spend, longer sessions, separate EGM games, and EGM games in more locations (Hing & Russell, 2020 ). Normative influences from media advertising and significant others were also associated with a higher risk of problem gambling (Hing et al., 2016b ).

A study that analyzed risk factors in online gaming concluded that more frequent gambling in online EGMs, substance use while gambling, and greater psychological distress were more frequent risk factors. Specifically, in an online sports betting group and an online racing betting group, researchers found that participants were mostly male, young, spoke a language other than English, were under greater psychological stress and showed more negative attitudes towards the game (Hing et al., 2017 ). However, sports betting gamblers had financial difficulties, while risk factors for online race betting gamblers included betting more often on races, engaging in more forms of gambling, self-reporting as a semi-professional/professional gambler, and used illicit drugs during the game (Hing et al., 2017 ).

Furthermore, moderate/highly severe gamblers were more likely to have a poor diet, engaged less in physical activities and had a poor general health than gamblers without problems. Also, tobacco use is associated with low and moderate/highly severe gambling. Low-severity gambling, opposing to moderate/highly severe gambling, was significantly associated with binge drinking and increased alcohol consumption. Unhealthy behaviors did tend to group together, and there was a scaled relationship between the severity of gambling problems and the likelihood of reporting at least two unhealthy behaviors. Compared to problem-free gamblers, low-severity gamblers were approximately twice as likely to have low mental well-being, and moderate/high-severity players were three times more likely to have low mental well-being (Butler et al., 2019 ).

To identify gambling trajectories in poker players, a latent class growth analysis was carried out over three years. Three gambling problem trajectories were identified, comprising a decreasing trajectory (1st: non-problematic-diminutive), a stable trajectory (2nd: low-risk-stable), and an increasing trajectory (3rd: problematic gamblers-increasing). The Internet as the main form of poker and the number of games played were associated with risk trajectories. Depression symptoms were significant predictors of the third trajectory, while impulsivity predicted the second trajectory. This study shows that the risk remains low over the years for most poker players. However, vulnerable poker players at the start of the study remain on a problematic growing trajectory (Dufour et al., 2019 ).

Regarding gender differentiation, studies have shown differences between the empirical groupings of men and women on different sociodemographic and clinical measures. In men, the number of DSM-5 criteria for disordered gambling (DG) reached the highest relative importance. This was followed by the degree of cognitive bias and the number of gambling activities. In women, the number of gambling activities reached the highest relative importance for grouping, followed by the number of DSM-5 criteria for PG. The relevance of the grouping was achieved by the cognitive bias (Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2020 ).

Women showed a preference for easy bets (easy bets are considered safer, therefore, with a greater chance of winning), electronic gambling machines, scratch cards or bingo for reasons other than socializing, earning money, or for general entertainment (Hing et al., 2016a ). Women also reported greater problem severity and shorter problem duration, greater pain, and lower quality of life than men (Delfabbro et al., 2017 ; Kim et al., 2016 ). Men prefer to bet on EGMs, table games, races, sports, or lotteries and win non-social games (Hing et al., 2016a ), and were more likely to exhibit aggressive behavior towards gaming equipment (Delfabbro et al., 2017 ). Men differed more between problem gamblers and non-problem gamblers, either through signs of emotional distress or trying to hide their presence in the game room from others. Among women, signs of anger, decreased care and attempts to obtain credit were the most prominent indicators (Delfabbro et al., 2017 ).

The risk of developing pathological gambling was higher for men with less education and less adaptive psychorelational skills. On the other hand, women with higher levels of education and more adapted psychorelational functioning were more likely to become pathological gamblers. Notwithstanding, the odds of being a pathological non-gambler (anything other than a pathological gambler) were higher for women with a high educational level and more adaptive psychorelational functioning (Cunha et al., 2017 ).

Risk Factors for Increased Online Gambling During COVID-19

During 2020/21 almost one-quarter of online gamblers increased their gambling during lockdown (Bellringer & Garrett, 2021 ; Fluharty et al., 2022 ; Swanton et al., 2021 ), with this most likely to be on overseas gambling sites, instant scratch card gambling and Lotto (Bellringer & Garrett, 2021 ; Price et al., 2022 ). The sociodemographic risk factor for increased online gambling was higher education (Bellringer & Garrett, 2021 ), or low education (Fluharty et al., 2022 ), and financial difficulties related to COVID (Price et al., 2022 ; Swanton et al., 2021 ).

The studies indicate a link between change in online gambling involvement during COVID-19 and increased mental health problems (Price et al., 2022 ), including stress from boredom (Fluharty et al., 2022 ), and higher levels of depression and anxiety (Fluharty et al., 2022 ; Price et al., 2022 ).

Behavioral risk factors included being a current low risk/moderate risk/problem gambler, a previously hazardous alcohol drinker (i.e., excessive) or past participation in free-to-play gambling-type games (Bellringer & Garrett, 2021 ), and alcohol consumption (Fluharty et al., 2022 ; Swanton et al., 2021 ). Financial well-being showed strong negative associations with problem gambling and psychological distress (Swanton et al., 2021 ).

As lockdown restrictions eased, ethnic minority individuals who were current smokers and were less educated were more likely to continue gambling more than usual (Fluharty et al., 2022 ).

With this systematic review, we aimed at exploring what are the risk factors for the development/maintenance of gambling disorder. We also searched the literature for information on differences between pre-pandemic gambling patterns and gambling patterns today. A total of 33 studies examined risk factors associated with gambling problems in adults.

Studies, with mixed samples, have shown several risk factors associated with risk problems for problem or pathological gamblers, namely being male, young, single or married less than 5 years, living alone, having a low level of education, and having financial difficulties.

As for relationships, pathological gamblers have greater difficulties in family and social relationships than non-players (Cowlishaw et al., 2016 ; Landreat et al., 2020 ). And they even increase the risk of gambling when they grew up with a single parent (Buth et al., 2017 ) or parents with addiction problems (Buth et al., 2017 ; Cavalera et al., 2017 ; Hing et al., 2017 ).

About health, there is a consensus that gambling addiction decreases quality of life, a reflection of worse mental health (Buth et al., 2017 ; Butler et al., 2019 ; Cowlishaw et al., 2016 ; Dennis et al., 2017 ; Delfabbro et al., 2017 ). Studies have shown a comorbidity of gambling problems with higher levels of stress (Hing et al., 2017 ; Wong et al., 2017 ), higher levels of impulsivity (Browne et al., 2019 ; Dufour et al., 2019 ; Gori et al., 2021 ; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2020 ; Flórez et al., 2016 ), cognitive distortions (Black & Allen, 2021 ; De Pasquale et al., 2018 ), and various pathologies, namely, anxiety (Fluharty et al., 2022 ; Landreat et al., 2020 ; Medeiros et al., 2016 ; Rodriguez-Monguio et al., 2017 ), schizophrenia (Bergamini, 2018 ), bipolar disorder (Bergamini, 2018 ), depression (Bergamini, 2018 ; Black & Allen, 2021 ; Dufour et al., 2019 ; Fluharty et al., 2022 ; Landreat et al., 2020 ), alexithymia (Bibby & Ross, 2017 ; Gori et al., 2021 ), mood disorders (Rodriguez-Monguio et al., 2017 ), and substance use disorders (Bergamini, 2018 ; Buth et al., 2017 ; Butler et al., 2019 ; Browne et al., 2019 ; Cowlishaw et al., 2016 ; Flórez et al., 2016 ; Fluharty et al., 2022 ; Hing & Russell, 2020 ; Hing et al., 2017 ; Rodriguez-Monguio et al., 2017 ).

As for the type of game, gamblers who played more than one game, and had longer gambling sessions, were at greater risk of problem gambling (Cavalera et al., 2017 ; Hing et al., 2016a ; Hing & Russell, 2020 ; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2020 ).

However, two studies presented different data (Biegun et al., 2020 ; Çakıcı et al., 2015 ). Biegun et al. ( 2020 ), did not find an association between problem gambling and various mental health correlates, such as depression, anxiety, and stress. In another study, players had higher levels of education and were employed, contrary to data found so far. However, it is necessary to bear in mind that the study was developed in Cyprus and, as the authors themselves mention, it is a country with sociocultural characteristics, such as a history of colonization, socioeconomic problems, and high unemployment (Çakıcı et al., 2015 ), which may justify that only people with income can become addicted to gambling.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, online gamblers have increased their gambling (Bellringer & Garrett, 2021 ), aggravating the psychological and social consequences for people with problematic gambling behaviors (Håkansson et al., 2020 ; Yayha & Khawaja, 2020 ). The authors highlighted the removal of protective factors, including structured daily life (Yayha & Khawaja, 2020 ), boredom (Fluharty et al., 2022 ; Lindner et al., 2020 ), depression and anxiety (Fluharty et al., 2022 ), as well a financial deprivation (Price, 2020; Swanton et al., 2021 ), as the main reasons for the increase in gambling problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is well known that the daily lives of many people have been substantially altered, with a high degree of homeschooling for school children and students (Tejedor et al., 2021 ), also with likely negative effects for young people and their families (Thorell et al., 2021 ). Likewise, restrictions related to COVID-19 and changes in the lives of many people have led to significant job insecurity, unemployment, and financial problems, as well as fear of illness and mortality, which has increased emotional distress (Shakil et al., 2021 ; Swanton et al., 2021 ). Researchers have expressed concerns that COVID-19 would have consequences for the mental health (Holmes et al., 2020 ; Zheng et al., 2021 ), as well as substance use disorders, and it is important to adapt treatment during the pandemic. (Marsden et al., 2020 ). The increase in the incidence and prevalence of behavioral addictions and the relevance of the early onset of the problem of gambling disorder, with its serious consequences, make it necessary to better understand these problems to develop and adapt prevention and treatment programs to the specific needs of according to sex and age. Furthermore, understanding gender-related differences is of great importance in treating behavioral addictions.

The growing availability of gambling in recent decades, a low social knowledge about gambling disorders, and a perception of gambling more in terms of moral weakness than a psychological/psychiatric disorder have an impact on the social acceptance of gambling behaviors (e.g., Hing et al., 2015 ; Petry & Blanco, 2013 ; St-Pierre et al., 2014 ).

This systematic review presents limitations. As in all systematic reviews, there is the risk of reporting bias. As only studies published in identifiable sources were included, unpublished studies may be more likely to not have significant results, thus indicating the absence of risk factors in the involvement in problematic or pathological gambling that we have analyzed. For this reason, we had no constraints regarding geographic and linguistic criteria. Also, the adherence to the PRISMA guidelines, including definition of accurate inclusion and exclusion criteria, the use of independent reviewers, as well as the efforts to diminish publication bias, strengthen this systematic review and better elucidate about risk factors in the involvement in problematic or pathological gambling. Another limitation of this study is the little literature on the post-COVID pathological gambling, which does not allow us to draw conclusions from comparisons. Future research would benefit from making comparisons, not just across gender, but also across culture. Researchers should further explore and understand how cultural environments influence the development of problematic gambling.

Treatment providers must consider the specificities of people with gambling disorders. Therefore, a strong educational/training background for therapists and other professionals, considering the problem of gambling disorders in the diagnosis, a better adaptation of the contents of therapeutic programs, and the creation of materials used in therapy adapted to the patient’s needs, would be very much advisable. It would also be helpful to establish therapeutic groups, ideally with at least a couple of patients with gambling disorders.

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Declarations

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Diana Moreira, Centro de Solidariedade de Braga/Projecto Homem, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Faculty of Philosophy and Social Sciences, Centre for Philosophical and Humanistic Studies, Laboratory of Neuropsychophysiology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Porto, and Institute of Psychology and Neuropsychology of Porto – IPNP Health (Portugal). Andreia Azeredo, Laboratory of Neuropsychophysiology, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Porto (Portugal). Paulo Dias, Centro de Solidariedade de Braga/Projecto Homem and Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Faculty of Philosophy and Social Sciences, Centre for Philosophical and Humanistic Studies (Portugal). The authors do not have any interests that might be interpreted as influencing the research. The study was conducted according to APA ethical standards.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Auer M, Malischnig D, Griffiths M. Gambling before and during the covid-19 pandemic among European regular sports bettors: An empirical study using behavioral tracking data. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020; 29 :1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00327-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bellringer ME, Garrett N. Risk factors for increased online gambling during covid-19 lockdowns in New Zealand: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18 (24):12946. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182412946. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bergamini A, Turrina C, Bettini F, Toccagni A, Valsecchi P, Sacchetti E, Vita A. At-risk gambling in patients with severe mental illness: Prevalence and associated features. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2018; 7 (2):348–354. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.47. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhullar N, Simons L, Joshi K, Amoroso K. The relationship among drinking games, binge drinking and gambling activities in college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2012; 56 (2):58–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bibby PA, Ross KE. Alexithymia predicts loss chasing for people at risk for problem gambling. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2017; 6 (4):630–638. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.076. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Biegun J, Edgerton JD, Roberts LW. Measuring problem online video gaming and its association with problem gambling and suspected motivational, mental health, and behavioral risk factors in a sample of university students. Games and Culture. 2020; 16 (4):434–456. doi: 10.1177/1555412019897524. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Black D. Clinical characteristics. In: Grant J, Potenza MN, editors. Gambling disorder: A clinical guide to treatment. 2. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2022. [ Google Scholar ]

- Black D, Grant J. DSM-5 guidebook: The essential companion to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Black DW, Allen J. An exploratory analysis of predictors of course in older and younger adults with pathological gambling: A non-treatment sample. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2021; 37 (4):1231–1243. doi: 10.1007/s10899-021-10003-8. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Black D, Coryell W, McCormick B, Shaw M, Allen J. A prospective follow-up study of younger and older subjects with pathological gambling. Psychiatry Research. 2017; 256 :162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.043. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brodeur M, Audette-Chapdelaine S, Savard A, Kairouz S. Gambling and the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2021; 111 :110389. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110389. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Browne M, Hing N, Rockloff M, Russell AMT, Greer N, Nicoll F, Smith G. A multivariate evaluation of 25 proximal and distal risk-factors for gambling-related harm. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8 (4):509. doi: 10.3390/jcm8040509. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buth S, Wurst FM, Thon N, Lahusen H, Kalke J. Comparative analysis of potential risk factors for at-risk gambling, problem gambling and gambling disorder among current gamblers—results of the Austrian representative survey 2015. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02188. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Butler N, Quigg Z, Bates R, Sayle M, Ewart H. Gambling with your health: Associations between gambling problem severity and health risk behaviours, health and wellbeing. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2019; 36 (2):527–538. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09902-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Çakıcı M, Çakıcı E, Babayiğit A, Karaaziz M. Gambling behaviour: Prevalence, risk factors and relation with acculturation in 2007–2018 North Cyprus adult household surveys. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2021; 37 (4):1099–1111. doi: 10.1007/s10899-021-10008-3. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Çakıcı M, Çakıcı E, Karaaziz M. Lifetime of prevalence and risk factors of problem and pathologic gambling in North Cyprus. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2015; 32 (1):11–23. doi: 10.1007/s10899-015-9530-5. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Calado F, Griffiths M. Problem gambling worldwide: An update and systematic review of empirical research (2000–2015) Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2016; 5 (4):592–613. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.073. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cavalera C, Bastiani L, Gusmeroli P, Fiocchi A, Pagnini F, Molinari E, Castelnuovo G, Molinaro S. Italian adult gambling behavior: At risk and problem Gambler Profiles. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2017; 34 (3):647–657. doi: 10.1007/s10899-017-9729-8. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ciarrocchi J. Counseling problem gamblers: A self-regulation manual for individual and family therapy. Academic Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cowan P, Cowan C, Schulz M. Thinking about risk and resilience in families. In: Hetherington EM, Blechman EA, editors. Stress, coping and resiliency in children and families. UK: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 1–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cowlishaw S, Hakes JK, Dowling NA. Gambling problems in treatment for affective disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions (NESARC) Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016; 202 :110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.023. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cunha D, De Sousa B, Relvas AP. Risk factors for pathological gambling along a continuum of severity: Individual and relational variables. Journal of Gambling Issues. 2017 doi: 10.4309/jgi.2017.35.3. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Custer, R. (1985). When luck runs out . Facts on File.

- De Pasquale C, Dinaro C, Sciacca F. Relationship of Internet gaming disorder with dissociative experience in Italian university students. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2018 doi: 10.1186/s12991-018-0198-y. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Delfabbro, P. (2012). Australasian gambling review (5th Ed.). Independent Gambling Authority.

- Delfabbro P, Thomas A, Armstrong A. Gender differences in the presentation of observable risk indicators of problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2017; 34 (1):119–132. doi: 10.1007/s10899-017-9691-5. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dennis CB, Davis TD, Chang J, McAllister C. Psychological vulnerability and gambling in later life. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2017; 60 (6–7):471–486. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2017.1329764. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dufour M, Morvannou A, Brunelle N, Kairouz S, Laverdière É, Nadeau L, Berbiche D, Roy É. Gambling problem trajectories and associated individuals risk factors: A three-year follow-up study among poker players. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2019; 36 (1):355–371. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09831-6. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Economou M, Souliotis K, Malliori M, Peppou L, Kontoangelos K, Lazaratou H, Anagnostopoulos D, Golna C, Dimitriadis G, Papadimitriou G, Papageorgiou C. Problem gambling in Greece: Prevalence and risk factors during the financial crisis. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2019; 35 (4):1193–1210. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09843-2. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Engwall D, Hunter R, Steinberg M. Gambling and other risk behaviors on university campuses. Journal of American College Health. 2004; 52 (6):245–255. doi: 10.3200/JACH.52.6.245-256. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Flórez G, Saiz PA, Santamaría EM, Álvarez S, Nogueiras L, Arrojo M. Impulsivity, implicit attitudes and explicit cognitions, and alcohol dependence as predictors of pathological gambling. Psychiatry Research. 2016; 245 :392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.039. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fluharty M, Paul E, Fancourt D. Predictors and patterns of gambling behaviour across the COVID-19 lockdown: Findings from a UK cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022; 298 (Pt A):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.117. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gori A, Topino E, Craparo G, Bagnoli I, Caretti V, Schimmenti A. A comprehensive model for gambling behaviors: Assessment of the factors that can contribute to the vulnerability and maintenance of gambling disorder. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2021; 38 (1):235–251. doi: 10.1007/s10899-021-10024-3. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goudriaan A, Oosterlaan J, de Beurs E, van den Brink W. The role of self-reported impulsivity and reward sensitivity versus neurocognitive measures of disinhibition and decision-making in the prediction of relapse in pathological gamblers. Psychological Medicine. 2008; 38 (1):41–50. doi: 10.1017/s0033291707000694. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goudriaan A, Slutske W, Krull J, Sher K. Longitudinal patterns of gambling activities and associated risk factors in college students. Addiction. 2009; 104 (7):1219–1232. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02573.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Håkansson A, Fernández-Aranda F, Menchón J, Potenza M, Jiménez-Murcia S. Gambling during the COVID-19 crisis—cause for concern? Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2020; 14 (4):e10–e12. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000690. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hing N, Russell AMT. Proximal and distal risk factors for gambling problems specifically associated with electronic gaming machines. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2020; 36 (1):277–295. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09867-8. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hing N, Russell AM, Browne M. Risk factors for gambling problems on online electronic gaming machines, race betting and sports betting. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00779. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hing N, Russell A, Gainsbury S, Nuske E. The public stigma of problem gambling: Its nature and relative intensity compared to other health conditions. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2015; 32 (3):847–864. doi: 10.1007/s10899-015-9580-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hing N, Russell A, Tolchard B, Nower L. Risk factors for gambling problems: An analysis by gender. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2016; 32 (2):511–534. doi: 10.1007/s10899-015-9548-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hing N, Russell AMT, Vitartas P, Lamont M. Demographic, behavioural and normative risk factors for gambling problems amongst sports bettors. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2016; 32 (2):625–641. doi: 10.1007/s10899-015-9571-9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hodgins D, Peden N. Natural course of gambling disorders: Forty-month follow-up. Journal of Gambling Issues. 2005 doi: 10.4309/jgi.2005.14.5. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holmes E, O’Connor R, Perry V, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Ballard C, Christensen H, Silver R, Everall I, Ford T, John A, Kabir T, King K, Madan I, Michie S, Przybylski A, Shafran R, Sweeney A, Worthman C, Yardley L, Cowan K, Cope C, Hotopf M, Bullmore E. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7 (6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30168-1. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang J, Jacobs D, Derevensky J. DSM-based problem gambling: Increasing the odds of heavy drinking in a national sample of U.S. college athletes? Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011; 45 (3):302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.07.001. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jiménez-Murcia S, Fernández-Aranda F, Granero R, Menchón J. Gambling in Spain: Update on experience, research and policy. Addiction. 2014; 109 (10):1595–1601. doi: 10.1111/add.12232. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jiménez-Murcia S, Granero R, Giménez M, del Pino-Gutiérrez A, Mestre-Bach G, Mena-Moreno T, Moragas L, Baño M, Sánchez-González J, Gracia M, Baenas-Soto I, Contaldo F, Valenciano-Mendoza E, Mora-Maltas B, López-González H, Menchón J, Fernández-Aranda F. Moderator effect of sex in the clustering of treatment-seeking patients with gambling problems. Neuropsychiatrie. 2020; 34 (3):116–129. doi: 10.1007/s40211-020-00341-1. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johansson A, Grant J, Kim S, Odlaug B, Gotestam K. Risk factors for problematic gambling: A critical literature review. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2009; 25 (1):67–92. doi: 10.1007/s10899-008-9088-6. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johansson A, Grant J, Kim S, Odlaug B, Götestam K. Risk factors for problematic gambling: A critical literature review. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2009; 25 (1):67–92. doi: 10.1007/s10899-008-9088-6. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kessler R, Hwang I, La Brie R, Petukhova M, Sampson N, Winters K. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2008; 38 (9):1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim H, Hodgins D, Bellringer M, Abbott M. Gender differences among helpline callers: Prospective study of gambling and psychosocial outcomes. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2016; 32 :605–623. doi: 10.1007/s10899-015-9572-8. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LaBrie R, Shaffer H, LaPlante D, Wechsler H. Correlates of college student gambling in the United States. Journal of American College Health. 2003; 52 (2):53–62. doi: 10.1080/07448480309595725. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Landis J, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977; 33 (1):159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Landreat G, Chereau Boudet I, Perrot B, Romo L, Codina I, Magalon D, Fatseas M, Luquiens A, Brousse G, Challet-Bouju G, Grall-Bronnec M. Problem and non-problem gamblers: a cross-sectional clustering study by gambling characteristics. British Medical Journal Open. 2020; 10 (2):e030424. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030424. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LaPlante D, Nelson S, LaBrie R, Shafer H. Stability and progression of disordered gambling: Lessons from longitudinal studies. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2008; 53 (1):52–60. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300108. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lindner P, Forsström D, Jonsson J, Berman A, Carlbring P. Transitioning between online gambling modalities and decrease in total gambling activity, but no indication of increase in problematic online gambling intensity during the first phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Sweden: A time series forecast study. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020; 8 :554542. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.554542. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lupton D. Risk. Routledge; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lynch W, Maciejewski P, Potenza M. Psychiatric correlates of gambling in adolescents and young adults grouped by age at gambling onset. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004; 61 (11):1116–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1116. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marsden J, Darke S, Hall W, Hickman M, Holmes J, Humphreys K, Neale J, Tucker J, West R. Mitigating and learning from the impact of COVID-19 infection on addictive disorders. Addiction. 2020; 115 (6):1007–1010. doi: 10.1111/add.15080. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martens M, Rocha T, Cimini M, Diaz-Myers A, Rivero E, Wulfert E. The co-occurrence of alcohol use and gambling activities in first-year college students. Journal of American College Health. 2009; 57 (6):597–602. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.6.597-602. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martin R, Usdan S, Cremeens J, Vail-Smith K. Disordered gambling and co-morbidity of psychiatric disorders among college students: An examination of problem drinking, anxiety and depression. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2014; 30 (2):321–333. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9367-8. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mazza M, Marano G, Lai C, Janiri L, Sani G. Danger in danger: Interpersonal violence during COVID-19 quarantine. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 289 :113046. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113046. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Medeiros GC, Sampaio DG, Leppink EW, Chamberlain SR, Grant JE. Anxiety, gambling activity, and neurocognition: A dimensional approach to a non-treatment-seeking sample. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2016; 5 (2):261–270. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.044. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009; 6 (7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.100009. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oei T, Gordon L. Psychosocial factors related to gambling abstinence and relapse in members of gamblers anonymous. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2008; 24 (1):91–105. doi: 10.1007/s10899-007-9071-7. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Olason D, Hayer T, Meyer G, Brosowski T. Economic recession affects gambling participation but not problematic gambling: Results from a population-based follow-up study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017; 8 :1247. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01247. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Petry N, Blanco C. National gambling experiences in the United States: Will history repeat itself? Addiction. 2013; 108 (6):1032–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03894.x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pietrzak R, Petry N. Antisocial personality disorder is associated with increased severity of gambling, medical, drug and psychiatric problems among treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Addiction. 2005; 100 (8):1183–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01151.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Price A, Tabri N, Stark S, Balodis IM, Wohl MJA. Mental health over time and financial concerns predict change in online gambling during COVID-19. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2022; 20 :1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00750-5. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodriguez-Monguio R, Errea M, Volberg R. Comorbid pathological gambling, mental health, and substance use disorders: Health-care services provision by clinician specialty. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2017; 6 (3):406–415. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.054. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shakil M, Ashraf F, Muazzam A, Amjad M, Javed S. Work status, death anxiety and psychological distress during COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for the terror management theory. Death Studies. 2021; 46 (5):1100–1005. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1865479. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Slutske W, Eisen S, Xian H, True W, Lyons M, Goldberg J, Tsuang M. A twin study of the association between pathological gambling and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001; 110 (2):297–308. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.110.2.297. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steel Z, Blaszczynski A. Impulsivity, personality disorders and pathological gambling severity. Addiction. 1998; 93 (6):895–905. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93689511.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- St-Pierre R, Walker D, Derevensky J, Gupta R. How availability and accessibility of gambling venues influence problem gambling: A review of the literature. Gaming Law Review & Economics. 2014; 18 (2):150–172. doi: 10.1089/glre.2014.1824. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stuhldreher W, Stuhldreher T, Forrest K. Gambling as an emerging health problem on campus. Journal of American College Health. 2007; 56 (1):75–88. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.1.75-88. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Subramaniam M, Wang P, Soh P, Vaingankar J, Chong S, Browning C, Thomas S. Prevalence and determinants of gambling disorder among older adults: A systematic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2015; 41 :199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.007. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Swanton T, Burgess M, Blaszczynski A, Gainsbury S. An exploratory study of the relationship between financial well-being and changes in reported gambling behaviour during the COVID-19 shutdown in Australia. Journal of Gambling Issues. 2021 doi: 10.4309/jgi.2021.48.7. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tejedor S, Cervi L, Pérez-Escoda A, Tusa F, Parola A. Higher education response in the times of coronavirus: Perceptions of teachers and students, and open innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2021; 7 (1):43. doi: 10.3390/joitmc7010043. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thorell L, Skoglund C, Giménez de la Peña A, Baeyens D, Fuermaier A, Groom M, Mammarella I, van der Oord S, van den Hoofdakker B, Luman M, Miranda D, Siu A, Steinmayr R, Idrees I, Soares L, Sörlin M, Luque J, Moscardino U, Roch M, Crisci G, Christiansen H. Parental experiences of homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: Differences between seven European countries and between children with and without mental health conditions. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2021; 31 (4):649–661. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01706-1. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vachon J, Vitaro F, Wanner B, Tremblay R. Adolescent gambling: Relationships with parent gambling and parenting practices. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004; 18 (4):398–401. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.398. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Ladouceur R, Tremblay R. Gambling, delinquency, and drug use during adolescence: Mutual influences and common risk factors. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2001; 17 (3):171–190. doi: 10.1023/a:1012201221601. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Volberg RA, McNamara LM, Carris KL. Risk factors for problem gambling in california: Demographics, comorbidities and gambling participation. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2017; 34 (2):361–377. doi: 10.1007/s10899-017-9703-5. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Werner E. Risk, resilience, and recover: Perspectives from the Kauai longitudinal study. Development and Psychopathology. 1993; 5 (4):503–515. doi: 10.1017/S095457940000612X. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams, R., Hann, R., Shopfocher, D., West, B., McLaughlin, P., White, N., King, K., & Flexhaug, T. (2015). Quinte longitudinal study of gambling and problem gambling . Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Center.

- Wong DFK, Zhuang XY, Jackson A, Dowling N, Lo H. Negative mood states or dysfunctional cognitions: Their independent and interactional effects in influencing severity of gambling among Chinese problem gamblers in Hong Kong. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2017; 34 (3):631–645. doi: 10.1007/s10899-017-9714-2. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wood R, Griffiths M. Understanding positive play: An exploration of playing experiences and responsible gambling practices. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2015; 31 (4):1715–1734. doi: 10.1007/s10899-014-9489-7. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yayha A, Khawaja S. Problem gambling during the COVID-19 pandemic. Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 2020 doi: 10.4088/pcc.20com02690. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zheng J, Morstead T, Sin N, Klaiber P, Umberson D, Kamble S, DeLongis A. Psychological distress in North America during COVID-19: The role of pandemic-related stressors. Social Science & Medicine. 2021; 270 :113687. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113687. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Open access

- Published: 27 August 2020

Risk factors for gambling and problem gambling: a protocol for a rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Caryl Beynon 1 ,

- Nicola Pearce-Smith 1 &

- Rachel Clark ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2800-2713 1

Systematic Reviews volume 9 , Article number: 198 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

4780 Accesses

3 Citations

84 Altmetric

Metrics details

Gambling and problem gambling are increasingly being viewed as a public health issue. European surveys have reported a high prevalence of gambling, and according to the Gambling Commission, in 2018, almost half of the general population aged 16 and over in England had participated in gambling in the 4 weeks prior to being surveyed. The potential harms associated with gambling and problem are broad, including harms to individuals, their friends and family, and society. There is a need to better understand the nature of this issue, including its risk factors. The purpose of this study is to identify and examine the risk factors associated with gambling and problem gambling.

An umbrella review will be conducted, where systematic approaches will be used to identify, appraise and synthesise systematic reviews and meta-analyses of risk factors for gambling and problem gambling. The review will include systematic reviews and meta-analyses published between 2005 and 2019, in English language, focused on any population and any risk factor, and of quantitative or qualitative studies. Electronic searches will be conducted in Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycInfo, NICE Evidence and SocIndex via EBSCO, and a range of websites will be searched for grey literature. Reference lists will be scanned for additional papers and experts will be contacted. Screening, quality assessment and data extraction will be conducted in duplicate, and quality assessment will be conducted using AMSTAR-2. A narrative synthesis will be used to summarise the results.

The results of this review will provide a comprehensive and up-to-date understanding of the risk factors associated with gambling and problem gambling. It will be used by Public Health England as part of a broader evidence review of gambling-related harms.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019151520

Peer Review reports

Gambling is increasingly being identified as a public health problem [ 1 , 2 ]. Harms associated with gambling are wide-ranging and include harms not only to the individual gambler but to their families and close associates as well as wider society [ 3 , 4 ]. The global prevalence of problem gambling has been reported to range from 0.7 to 6.5%, and studies from across Europe have reported a high participation in gambling [ 5 ]. In 2018, a survey conducted in England by the Gambling Commission reported that almost half of the respondents had participated in gambling in the 4 weeks prior to being surveyed [ 6 ]. In addition, 0.7% of respondents were classified as ‘problem gamblers’ and an additional 1.1% of respondents were classified as ‘moderate risk’ gamblers, defined as ‘those who experience a moderate level of problems leading to some negative consequences’ [ 6 ]. The threshold for being considered a ‘problem gambler’ within this particular survey is high—a person has to score 8 or more on the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) or 3 or more according to the Diagnostic or Statistical Manual-IV [ 7 ]. So the number of people experiencing problem gambling could well be higher.

Risk factors are traits or exposures that increase the possibility that an individual will develop a condition and can be fixed or variable [ 8 ]. The risk factors for gambling and problem gambling are broad and have been reported in numerous systematic reviews and primary studies. At an individual level, risk factors include (but are not limited to) fixed biological factors, such as gender and impulsivity, and behavioural factors such as levels of participation in gambling, excessive use of alcohol and use of illicit drugs and propensity towards violent behaviour [ 9 ]. Broader factors related to the family environment [ 10 ] and gambling availability have also been identified [ 11 ]. A scoping search identified a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of risk factors for problem gambling, largely focused on specific risk factors or types of risk [ 9 , 10 , 11 ] although one focused on specific populations [ 12 ]. No systematic reviews, meta-analyses or umbrella reviews were identified examining all risk factors for all populations. In order to understand the breadth of possible risk factors driving gambling and problem gambling behaviours, there is a need to collate this review-level evidence. This work is part of a broader review examining gambling-related harms [ 13 , 14 ].

The overall aim of this umbrella review is to identify the risk factors associated with gambling and problem gambling. The research questions are as follows:

What risk factors are associated with gambling?

What risk factors are associated with different levels of gambling intensity?

This review adopted a rapid review methodology [ 15 ] to identify, appraise and synthesise systematic reviews and meta-analyses, defined here as an ‘umbrella’ review [ 16 ]. The use of existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses enables a broad examination of best available evidence in a timely way and is useful for addressing the high-level questions set out for this review, where multiple risk factors are expected to be identified. This review protocol is being reported in accordance with reporting guidance provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement [ 17 ] (see checklist in Additional file 1 ). The protocol is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42019151520). The review will be conducted using EPPI-Reviewer 4.

Definitions of terms

There are multiple definitions of the term ‘gambling’, but for the purpose of this review, gambling is defined (as set out by the Gambling Act 2005) as ‘… any kind of betting, gaming or playing lotteries. Gaming means taking part in games of chance for a prize (where the prize is money or money’s worth), betting involves making a bet on the outcome of sports, races, events or whether or not something is true, whose outcomes may or may not involve elements of skill but whose outcomes are uncertain and lotteries (typically) involve a payment to participate in an event in which prizes are allocated on the basis of chance.’ [ 4 ].

There is no single definition for ‘harmful’ or ‘problem’ gambling, and this can be measured in several ways. For example, reports prepared for the Gambling Commission estimate problem gambling according to scores derived from 2 different instruments: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV) and the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI). The DSM-IV contains 10 diagnostic criteria and possible scores are between 0 and 10; a score of 3 or over indicates problem gambling. The PGSI contains 9 diagnostic criteria and a score of between 0 and 27 is possible; a score of 1–2 is ‘low risk’, 3–7 is ‘moderate risk’ and 8 and over is ‘problem gambling’ [ 7 ]. In the USA, the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) is commonly used, where positive answers to three out of twenty gambling-related questions are considered indicative of problem gambling [ 18 ]. In order to capture the breadth of literature available, no one definition will be adopted and this review will include papers which define ‘harmful’ or ‘problem’ gambling in different ways.

In the context of this review, a risk factor is defined as any factor investigated as being associated with gambling (including initiation, escalation, urge or intensity), either causally or otherwise. Where the evidence shows the link to be causal (rather than an association), this will be reported.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria have been developed using an adapted version of the PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) framework, as set out in Table 1 .

It is expected that two types of study will be identified for inclusion: (i) those that focus on the gambling population and explore all risk factors and (ii) those that focus on a specific risk factor.

Additional inclusion criteria:

Language: English (other languages will not be included, due to the team’s inability to translate)

Publication date: 1 January 2005–4 September 2019. 2005 was selected as a cut-off as in this year the Government issued proposals to reform the law on gambling [i.e. the Gambling Act] and the Economic and Social Research Council/Responsibility in Gambling Trust provided £1 million of funding for research on problem gambling—significantly increasing capacity for research on this topic in England [ 19 ].

Publication type: peer reviewed and grey literature

Setting: reviews of studies which are based within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Where studies set in non-OECD countries are also included, more than half of included studies must be from OECD countries and inclusion/exclusion will be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search will be undertaken using multiple methods to identify both published and grey literature. The search strategy was developed by a Senior Information Scientist in PHE and quality assured by a second Information Scientist.

Electronic searches

The following databases will be searched: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycINFO, Social Policy and Practice, Social Care Online, NICE Evidence and SocIndex via EBSCO. The number of papers retrieved from each database will be recorded. The full MEDLINE search is presented in Additional file 2 ; this will be adjusted for use in other databases. The search will look for terms in the title, abstract, author key words and thesaurus terms (such as MeSH Medical Subject Headings in MEDLINE) where available. The review filter will be used for all databases except for SocIndex (which does not have a validated one). For SocIndex, a set of search terms will be created in order to restrict the search to systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Grey literature

Reports and other relevant literature that may not be published in databases will be sought by searching Google and websites such as those listed here (years 2005 to 2019). If a website provides a review summary, effort will be made to find the full study report.

Gamble Aware InfoHub

Gambling Commission

GambLib (Gambling Research Library)

National Problem Gambling Clinic

Gordon Moody Association

Gamblers Anonymous

Gambling Information Resource Office Research Library

Advisory Board for Safer Gambling

Gambling Watch UK

Australian Gambling Research Centre

Gambling Research Exchange Ontario

Citizens Advice Bureau

Be Gamble Aware

Problem Gambling, Wigan Council

Gambling Compliance

Child Family Community Australia

International Centre for Youth Gambling Problems and High-Risk Behaviours

Gambling and Addictions Research Centre

Alberta Gambling Research Institute

Responsible Gambling Council

Problem Gambling Foundation of New Zealand

Gambling Commission New Zealand

Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation

Handsearching

Reference lists of retrieved papers will be searched for additional relevant papers which fulfil the inclusion/exclusion criteria. In addition, if any umbrella reviews are identified, the reference lists will be scanned for inclusion.

Consultation with experts

Once a list of included studies is available, this will be shared with the project Expert Reference Group to check for additional studies. This group includes national and international topic experts.

Screening and selection procedure

A pilot screen will be undertaken whereby each reviewer will independently screen the same 100 randomly selected references/papers and indicate which should be included/excluded. Reviewers will obtain the full paper if this is needed for them to make their assessment. Any discrepancies indicate inconsistencies in understanding of the inclusion/exclusion criteria between reviewers, and this stage will allow these to be identified, discussed and resolved. If necessary, the inclusion/exclusion criteria will be modified, and the changes will be recorded in a decision log.

References will be divided between four reviewers. The title/abstract of every reference will be screened independently by two reviewers (‘review pairs’) according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and each reference will be coded as either ‘included’ or ‘excluded’. EPPI-Reviewer will be used to measure inter-rater agreement for all reviewer pairs; agreement of 90% or over will be considered acceptable. If the agreement is less than 90%, the reason will be explored and rectified and screening will be repeated, in line with the guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on title/abstract screening [ 20 ].

The full articles of the remaining references will be obtained. Full articles will be divided between reviewers and screened using inclusion/exclusion codes set up in advance by the Project Team. Ten percent of the papers screened by each reviewer will be reviewed independently by a second reviewer using the ‘parent’ codes: include and exclude (i.e. rather than specific exclusion codes such as ‘date’, ‘geography’, ‘study type’). A threshold of 80% agreement will be considered acceptable in line with criteria outlined in the AMSTAR 2 (Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews) tool [ 21 ]. A decision on what steps should be taken if the agreement is less than 80% will be made by the Project Team should this situation arise.

Data extraction

Data extraction tables will be used to extract the relevant information from each study. These will include the following information: authors, date, country, the PICO-S elements and the relevant results. Authors will be contacted by the reviewers to ask for missing information or clarification where necessary, and where information is considered essential. Data extraction tables will be pilot tested before being used and signed off by the Expert Reference Group. All reviewers will extract the data from a set of eligible studies; 10% of all papers will be randomly selected and the data from these will be extracted independently by a second reviewer. Agreement between reviewers for data extraction will be checked to ensure this is acceptable (at least 80%). A decision on what steps should be taken if the agreement is less than 80% will be made by the Project Team should this situation arise. The Cochrane PROGRESS-Plus tool [ 22 ] will be used to extract data on the broad dimensions of inequality.

Quality assessment (risk of bias)

The quality of systematic reviews will be assessed using the AMSTAR2 checklist [ 21 ]. Each paper will be independently assessed by two reviewers, and disagreements will be resolved through discussion. If required, a third person will be brought in to resolve ongoing disagreements.

Method of synthesis

Given the broad scope of this review, included studies are likely to be heterogeneous, and therefore, a narrative analysis will be conducted with text used to summarise and explain findings [ 23 ]. Studies will be summarised according to themes. An appraisal of the quality of the literature will be included. Differences by sub-group will be examined where this is reported in the literature to integrate a focus on equity, using the Cochrane PROGRESS-Plus tool [ 22 ]. The body of evidence will be assessed according to the four principles laid out in the CERQual approach which are (1) the methodological limitations of the studies which make up the evidence, (2) the relevance of findings to the review question, (3) the coherence of the findings and (4) the adequacy of data supporting the findings [ 24 ].

This rapid umbrella review will identify and examine the breadth of risk factors associated with gambling and problem gambling. The findings of this review will be utilised as part of a broader review of evidence conducted by Public Health England on gambling-related harms. A full report of this work will be shared and discussed with government departments and published on our government website GOV.UK. The results of this review will also be submitted for publication in a peer review journal.

Any deviations to the protocol considered necessary will be discussed by the Project Team prior to being implemented and documented in a decision log (stored in Excel) for later reporting.

A number of limitations are anticipated. The reliance on existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses is impacted by the quality of their methods and reporting—whilst we are assessing this, if the quality is poor, our ability to fully utilise their results will be limited. In addition, there may be a large number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and if they are focused on different risk factors, the results may be difficult to synthesise.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews

Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Problem Gambling Severity Index

Public Health England

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols

South Oaks Gambling Screen

Gambling Commission. Young People & Gambling 2018. Gambling Commission: Birmingham; 2018.

Google Scholar

Wardle H, Reith G, Langham E, Rogers RD. Gambling and public health: we need policy action to prevent harm. BMJ. 2019;365:l1807.

Article Google Scholar

Langham E, Thorne H, Browne M, Donaldson P, Rose J, Rockloff M. Understanding gambling related harm: a proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:80.

Wardle H, Reith G, Best D, McDaid D, Platt A. Measuring gambling-related harms: a framework for action. London: The London School of Economics and Political Science; 2018.

Calado F, Griffiths MD. Problem gambling worldwide: an update and systematic review of empirical research (2000-2015). J Behav Addict. 2016;5(4):592–613.

Gambling Commission. Gambling participation in 2018: behaviour, awareness and attitudes. Birmingham: Gambling Commission; 2019.

Conolly A, Davies B, Fuller E, Heinze N, Wardel H. Gambling behaviour in Great Britain in 2016. Evidence from England, Scotland and Wales. London: NatCen Social Research; 2018.

Offord DR, Kraemer HC. Risk factors and prevention. Evid Based Ment Health. 2000;3(3):70–71.

Dowling N, Suomi A, Jackson A, Lavis T, Patford J, Cockman S, et al. Problem gambling and intimate partner volence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016;17(1):43–61.

McComb JL, Sabiston CM. Family influences on adolescent gambling behavior: a review of the literature. J Gambling Stud. 2010;26(4):503–20.

Johansson A, Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL, Götestam KG. Risk factors for problematic gambling: a critical literature review. J Gambling Stud. 2009;25(1):67–92.

Dowling NA, Merkouris SS, Greenwood CJ, Oldenhof E, Toumbourou JW, Youssef GJ. Early risk and protective factors for problem gambling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clinical psychology review. 2017;51:109–24.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Public Health England. Gambling-related harms evidence review: scope 2020. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/publications/gambling-related-harms-evidence-review/gambling-related-harms-evidence-review-scope .