Affirmative Action: Foundations and Key Concepts

This non-exhaustive reading list discusses the origins of affirmative action, the question of race vs. class, and the effects of meritocracy.

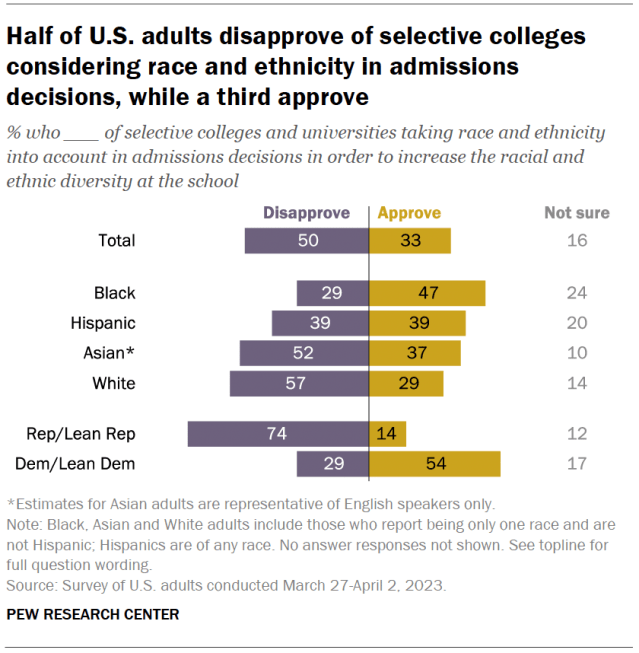

Affirmative action seeks to increase the representation of women and minorities in employment and education, spaces where they have been historically excluded. However, the discussion of preferential treatment based on racial or socioeconomic status has ignited intense public controversy, as highlighted through the college admissions scandal. The scandal exposed the underlying tensions between class and race in the United States, exhibiting the ways in which privilege is opposed to fairness.

The following non-exhaustive reading list discusses the origins of affirmative action, the question of race- versus class-based affirmative action, and the effects of meritocracy in admissions.

The Origins of Affirmative Action

Tierney, William G. “The Parameters of Affirmative Action: Equity and Excellence in the Academy.” Review of Educational Research , 1997

Tierney provides a historical analysis of affirmative action in higher education. Why was it needed as a policy? He then outlines the philosophical and legal ramifications of affirmative action before evaluating criticism and alternatives. He concludes that affirmative action should not be about rewriting past wrongs. Rather, the goal is to develop policies that serve the public good by advancing diversity and facilitating a culture of public participation.

Stulberg, L., & Chen, A. “The Origins of Race-conscious Affirmative Action in Undergraduate Admissions: A Comparative Analysis of Institutional Change in Higher Education.” Sociology of Education , 2014

This comparative and institutional analysis of race-conscious affirmative action policies found that affirmative action arose in two waves during the 1960s. The first wave of adoption occurred in the early 1960s, by colleges in the North that were inspired by the nonviolent civil rights protests occurring in the South. The second wave of adoption emerged in the late 1960s as a response to student protests on campus.

Once a Week

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Race- vs. Class-Based Affirmative Action

Bok, Derek. “Assessing the Results of Race-Sensitive College Admissions.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education , 2000

Derek Bok, the former president of Harvard University, discusses race-based affirmative action in college admissions. After studying more than 60,000 students, the author learned that most minority students attending selective colleges would have been rejected under a “race-neutral” admissions process. Bok assesses the different policy alternatives, like class-based affirmative action and top 10 percent plans. However, he concludes that these policies likely would not lead to the creation of racially diverse classes. He concludes that race-conscious admissions are the only solution that achieves diversity by admitting the best qualified minority students.

Cancian, Maria. “Race-Based versus Class-Based Affirmative Action in College Admissions.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management , 1998

Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Cancian tries to simulate the impact of moving away from a race-based admissions process to class-based affirmative action by examining whether racial and ethnic minorities would be eligible for a class-based program. A class-based college admissions process likely would bound the eligibility of racial and ethnic minorities and would not have similar results to race-based affirmative action.

Holzer, H., & Neumark, D. “ Affirmative Action: What Do We Know?” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management , 2006

This research report evaluates the effects of affirmative action on employment, college admissions, and government contracting. The empirical evidence shows that affirmative action programs shift employment, admissions, and government contracting away from white men and toward women and other minorities. However, these shifts in employment and college admissions do not have significant or large effects on the representation of minorities in colleges and university programs. Holzer and Neumark note that replacing race-based affirmative action with a different set of policies based on income or class rank likely would reduce the number of minorities enrolled at selective colleges.

Malamud, Deborah. “Assessing Class-Based Affirmative Action.” Journal of Legal Education , 1997

Malamud discusses why class-based affirmative action will likely not achieve economic equity in higher education. She also discusses why a class-based admission process is less likely to achieve racial equality.

Sander, Richard. “Experimenting with Class-Based Affirmative Action.” Journal of Legal Education , 1997

Sander discusses how UCLA School of Law incorporated class-based preferences into its admissions system and then evaluates the results. He discusses how the class preference system increased the socioeconomic diversity of the student body but had mixed results in preserving racial diversity.

The Challenges of Meritocracy

Liu, Amy. “Unraveling the myth of meritocracy within the context of US higher education.” Higher Education , 2011

Liu argues that in meritocracy, social status becomes intertwined with level of education. Colleges and universities are now the gatekeepers of class positions and access to them will determine future class status. Liu discusses how higher education should serve as an instrument to expand opportunity and not be reduced to a “defensive necessity.” She signals that it is important for researchers to examine the theoretical basis of meritocracy and its consequences in higher education.

Espenshade, T., Chung, C., & Walling, J. “Admission Preferences for Minority Students, Athletes, and Legacies at Elite Universities.” Social Science Quarterly , 2004

Espenshade, Chung, and Walling examine the college admissions process and the preferences for athletes, children of alumni, and minority applicants. The authors note how elite universities give additional weight to different characteristics in which academic preferences for athletes and legacies often compete with the preference for minority applicants.

Critical Race Theory

Yosso, T., Parker, L., Solórzano, D., & Lynn, M. “From Jim Crow to Affirmative Action and Back Again: A Critical Race Discussion of Racialized Rationales and Access to Higher Education.” Review of Research in Education , 2004

Using the framework of critical race theory, the authors discuss the role of race and racism in shaping educational institutions. They also discuss how color-blind, diversity, and remedial legal rationales are shaped by race and racism, underlining how conservatives challenge affirmative action based on a “colorblind” rationale, where race-blind admissions ensure meritocracy. Liberals, on the other hand, defend affirmative action based on a diversity rationale, where minority students enrich the learning environment for white students. The remedial rationale wishes to grant minority groups access as a partial remedy for past and current discrimination.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

A Bodhisattva for Japanese Women

Asking Scholarly Questions with JSTOR Daily

Confucius in the European Enlightenment

Watching an Eclipse from Prison

Recent posts.

- When All the English Had Tails

- Shakespeare and Fanfiction

- Sheet Music: the Original Problematic Pop?

- Ostrich Bubbles

- Smells, Sounds, and the WNBA

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

The Case for Affirmative Action

- Posted July 11, 2018

- By Leah Shafer

For decades, affirmative action has been a deeply integral — and deeply debated — aspect of college admissions in the United States. The idea that colleges can (and in some cases, should) consider race as a factor in whom they decide to admit has been welcomed by many as a solution to racial inequities and divides. But others have dismissed the policy as outdated in our current climate, and at times scorned it as a form of reverse racial discrimination.

That latter stance gained a much stronger footing last week when the Departments of Education and Justice officially withdrew Obama-era guidance on affirmative action, signaling that the Trump administration stands behind race-blind admissions practices.

We spoke with Natasha Warikoo , an expert on the connection between college admissions and racial diversity, about what affirmative action has accomplished in the past 50 years, and whether this shift in guidance will severely affect admissions policies in the years to come. We share her perspectives here.

The purpose of affirmative action:

Affirmative action was developed in the 1960s to address racial inequality and racial exclusion in American society. Colleges and universities wanted to be seen as forward-thinking on issues of race.

Then, in the late 1970s, affirmative action went to the United States Supreme Court. There, the only justification accepted, by Justice Powell, was the compelling state interest in a diverse student body in which everyone benefits from a range of perspectives in the classroom.

Today, when colleges talk about affirmative action, they rarely mention the issue of inequality, or even of a diverse leadership. Instead, they focus on the need for a diverse student body in which everyone benefits from a range of perspectives in the classroom.

Colleges have fully taken on this justification — to the point that, today, they rarely mention the issue of inequality, or even of a diverse leadership, perhaps because they’re worried about getting sued. But this justification leads to what I call in my book a “ diversity bargain ,” in that many white students see the purpose of affirmative action as to benefit them , through a diverse learning environment. This justification, which ignored equity, leads to some unexpected, troubling expectations on the part of white students.

What affirmative action has accomplished in terms of diversity on college campuses:

William Bowen and Derek Bok’s classic book The Shape of the River systematically looks at the impact of affirmative action by exploring decades of data from a group of selective colleges. They find that black students who probably benefited from affirmative action — because their achievement data is lower than the average student at their colleges — do better in the long-run than their peers who went to lower-status universities and probably did not benefit from affirmative action. The ones who benefited are more likely to graduate college and to earn professional degrees, and they have higher incomes.

So affirmative action acts as an engine for social mobility for its direct beneficiaries. This in turn leads to a more diverse leadership, which you can see steadily growing in the United States.

But what about other students — whites and those from a higher economic background? Decades of research in higher education show that classmates of the direct beneficiaries also benefit. These students have more positive racial attitudes toward racial minorities, they report greater cognitive capacities, they even seem to participate more civically when they leave college.

None of these changes would have happened without affirmative action. States that have banned affirmative action can show us that. California, for example, banned affirmative action in the late 1990s, and at the University of California, Berkeley, the percentage of black undergraduates has fallen from 6 percent in 1980 to only 3 percent in 2017 .

Decades of research in higher education show that classmates of the direct beneficiaries of affirmative also benefit. They have more positive racial attitudes toward racial minorities, they report greater cognitive capacities, they even seem to participate more civically when they leave college.

What the Trump administration's reversal of guidance on affirmative action means for admissions practices:

The guidance is simply guidance — it’s not legally binding. It indicates what the administration thinks, and how it might act. In that sense, this guidance is not surprising — many would have guessed that Trump and his team believe universities should avoid taking race into consideration in admissions. Indeed, the Department of Justice under Trump last summer already reopened a case filed under the Obama administration claiming racial discrimination in college admissions.

I hope that colleges and universities will stand behind affirmative action, given its many benefits. The U.S. Supreme Court has decided in favor of affirmative action multiple times — it is settled law.

However — the decision in Fisher v. Texas made clear that colleges would no longer be afforded good faith understanding that they have tried all other race-neutral alternatives before turning to affirmative action. In other words, if asked in court, colleges need to be able to show that they tried all other race-neutral alternatives to creating a diverse student body, and those alternatives failed. This means that affirmative action has already been “narrowly tailored” to the “compelling state interest” of a diverse student body — required by anti-discrimination laws. Ironically, race-based decisions come under scrutiny because of anti-discrimination laws designed to protect racial minorities; these laws are now being used to make claims about supposed anti-white discrimination when policies attempt to address racial inequality.

Additional Resources

- Read our 2016 Q+A with Warikoo following the Fisher v. Texas decision

- Listen to Warikoo discuss the Trump administration's reversal on a recent WBUR interview

- More background on the Trump administration's policy shift on affirmative action.

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Exploring Affirmative Action

Doctoral Students Brief Supreme Court

Putting Merit into Context

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

- PMC10798812

The impact of racial identity and school composition on affirmative action attitudes of African American college students

Germine h. awad.

a Department of Psychology, The University of Michigan, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Kimberly Tran

b Department of Psychology, Fayetteville State University, Fayetteville, NC, USA

Brittany Hall-Clark

c The University of Texas Health Science Center, Psychiatry, San Antonio TX, USA

Collette Chapman-Hilliard

d Counseling and Human Development, The University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA

Jendayi Dillard

e Department of Educational Psychology, University of Texas-Austin, Austin, TX, USA

Taylor Payne

Elaine hess, karen jackson.

f Educational Psychology and Assessment, Soka University, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA

Affirmative Action remains a controversial policy that incites a variety of reactions. Some believe it’s an unjust policy that discriminates against applicants, while others view it as a policy aimed at fighting against past inequalities and discrimination. Little is known about African American endorsement of the policy. Two hundred and seven Black students from a predominantly White institution (PWI) and a historically Black university (HBCU) participated in the current study to examine the impact of racial identity on affirmative action attitudes (AA). Results indicated that school type and race centrality significantly predicted AA attitudes. Students who attended a HBCU were less likely to endorse AA compared to students at the PWI and those higher in race centrality were more likely to endorse AA. This study is one of the first to investigate the impact of the educational environment on the affirmative action attitudes of African Americans.

Affirmative action is a controversial and complicated issue, often evoking a range of emotions and opinions. Opponents of affirmative action often view it as an unjust policy that discriminates against applicants (mainly White men), while proponents view affirmative action a a policy aimed at remedying historical discriminatory practices and increasing the numbers of underrrperesented applicants (e.g. ethnically minoritized individuals, women, and veterans) in the workforce and higher education. Although affirmative action policies are utilized in both industry and education, its use in higher education has elicited stronger debate and reaction about merit and equality than in employment settings ( Crosby et al., 2006 ). This is evidenced by a number of high-profile lawsuits against a number of universities in the United States, including the University of Michigan, University of Texas, and Harvard University (e.g. Hartocollis, 2020 ; Peralta, 2016 ; Peterson, 2003 ). Despite the controversial nature of the policy, its complexities are often ambiguous and not well understood. Affirmative action programs are designed to help increase diversity in higher education by implementing proactive recruitment and retention programs targeting underrepresented groups. Many institutions of higher education have asserted that diversity leads to positive educational outcomes and therefore measures to increase diversity are necessary ( Gurin et al., 2007 ).

Postsecondary enrollment among ethnic minority college students has slowly increased over the past several decades. Specifically, African American student enrollment has increased from 9% in the mid-1970s to 13% by 2018 ( National Center for Education Statistics, 2019 ). However, this enrollment increase among African Americans has not been a steady increase, particularly with the elimination of affirmative action policies. For example, following the 1996 Hopwood decision, a court case that upheld the decision that race could not be considered in admissions or financial aid decisions, the flagship universities in Texas experienced a significant decline in the number of African American and Hispanic applicants ( Tienda et al., 2003 ). Dickson (2006) suggests affirmative action bans decreased the percentage of African American and Hispanic students applying to college in Texas by 2.1% and 1.6% respectively. The ban of racial preference in college admissions in Texas also reflected a decrease in retention and graduation rates among ethnically minoritized students by 2%-5%, depending on the cohort examined ( Cortes, 2010 ). Similarly, other states experienced declines in ethnically minoritized student enrollment after the elimination of affirmative action policies. According to the University of California Office of Student Research (1998) , ethnically minoritized student enrollment declined nearly 21% after the ban on the consideration of race in admissions was implemented.

Race, racism and affirmative action

Although significant strides have been made, proponents of affirmative action assert that goals of equality have not yet been met ( Clayton & Crosby, 2000 ) and that discrimination and prejudice are still pervasive ( Bergmann, 1996 ; Swim et al., 2001 ). Racial/ethnic differences in affirmative action attitudes have consistently been found in the literature. One theory proposes that these differences are related to self-interest ( Bobo, 1998 ; Oh et al., 2010 ). Beneficiaries of affirmative action, including people of color and women, typically endorse more favorable attitudes towards the policy ( Awad et al., 2005 ; Bobo, 1998 ; Oh et al., 2010 ). However, Oh et al. (2010) compared both the group-interest and racism beliefs model, and found that racism beliefs are more strongly related to affirmative action attitudes than are self-interests.

While Americans’ attitudes towards affirmative action have grown steadily more positive over the years ( Pew Research Center, 2017 ), a strong and vocal opposition persists. Although affirmative action was designed to correct a long history of unequal resources and opportunities, opponents of the policy protest the alleged preferential treatment of ethnically minoritized groups. Awad et al. (2005) note that opponents of affirmative action often mischaracterize it as a means to give people of color an unfair advantage over Whites. Federico and Sidanius (2002) have described such arguments as ‘principled objection’ to affirmation action, due to the fact that they may appear to be race-neutral and instead rooted in concerns about fairness, justice, and merit. Several researchers ( Awad et al., 2005 ; Matsueda & Drakulich, 2009 ; Oh et al., 2010 ) have noted that racism has taken more subtle, covert forms that have become embedded within the ethos of American values, such as work ethic and individualism. Yet such beliefs can reflect covert racism by asserting that people of color would advance if they only worked harder. Individuals who hold attitudes such as these believe that discrimination is no longer a problem in the United States and that Blacks often deserve the poorer treatment they receive.

In response to the call for increased research focused primarily on beneficiaries of affirmative action, several studies have investigated African Americans’ reactions to related policies and plans ( Antwi-Boasiako & Asagba, 2005 ; Slaughter et al., 2002 ), generally indicating endorsement of the policy. There have been few studies, however, that investigate factors that may influence differing attitudes of affirmative action among African Americans. Given the dissention to affirmative action by prominent African American scholars such as Ward Connerly and with the American Civil Rights Institute’s crusade to ban Affirmative Action across the country ( Carter, 1991 ; Steele, 1990 ), it would be erroneous to assume attitude homogeneity. Therefore, examination of institutional factors such as school environment may help explain the differences in endorsement of affirmative action for African Americans.

School racial composition

For many years, researchers have explored the experiences of African Americans at predominately White institutions (PWIs) ( Allen, 1992 ; Lewis et al., 2004 ; Pillay, 2005 ). Fewer studies have examined the experiences of students at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). The majority of African Americans, around 68–82%, choose to attend PWIs ( Keller, 1988 ; Smith, 1991 ), which likely explains why research on these campuses is more prevalent. However, it is important to study African Americans in both of these environments as it may reveal how school racial composition may affect student attitudes on affirmative action.

There exists a longstanding debate in the literature about how college racial composition affects African American students. Although several studies have compared Black students at PWIs and HBCUs, the findings have been mixed. Some researchers report that Black students at HBCUs are better adjusted than their PWI counterparts ( Brown et al., 2001 ; Cheatham et al., 1990 ; Fleming, 1984 ; Greer & Brown, 2011 ), while other studies have failed to find evidence that HBCUs are more beneficial for African American students and have found no differences by school type ( Bohr et al., 1995 ; Cheatham et al., 1990 ; Kimbrough et al., 1996 ).

HBCUs were established to allow African Americans to educate themselves when they could not attend colleges that were reserved for members of the White, upper class ( Brown et al., 2001 ). Therefore, HBCUs were designed specifically with the well-being of African American students in mind, with the goals of preparation and empowerment for success in society ( Brown et al., 2001 ). Although fewer Black students attend HBCUs than PWIs, a disproportionate amount of degrees awarded to Black people are from HBCUs, suggesting that HBCUs tend to have better retention rates ( Gordon et al., 2020 ; Rodgers & Summers, 2008 ). Many researchers argue that HBCUs provide an environment of social support that helps students to flourish. Black students at HBCUs tend to have higher levels of academic engagement than their PWI counterparts ( Allen, 1992 ; Nelson Laird et al., 2007 ; Reeder & Schmitt, 2013 ), more positive student–faculty relationships ( Cokley, 2002 ), and more opportunities to be integrated into the campus community than Black students at PWIs ( Davis, 1991 ). While African-American students at HBCUs are less likely to experience racial discrimination on campus, students still must navigate prejudicial colorist attitudes ( Gasman & Abiola, 2016 ) and elitism borne from from the black bourgeoisie ‘respectability’ values and politics ( Cooper, 2017 ; Spencer, 2018 ; Young & Tsemo, 2011 ).

At PWIs, African Americans may be subjected to discrimination and racism. Many researchers have found that PWIs are less sensitive to the needs of Black students ( Brown et al., 2001 ; Keller, 1988 ). Some authors have argued that PWIs cannot provide the same levels of social support as HBCUs, which has been found to be an important variable for successful college adjustment. Black students at PWIs experience more alienation ( Steward et al., 1990 ; Winkle-Wagner & McCoy, 2018 ) and report lower social support than their HBCU counterparts ( Davis, 1991 ; Negga et al., 2007 ). Black students at PWIs have also been found to endorse higher levels of acculturative stress ( Joiner & Walker, 2002 ), discrimination and racism ( Brown et al., 2001 ), stereotyped treatment ( Allen, 1992 ) and race-related stress ( Neville et al., 2004 ).

To the authors’ knowledge, there are currently no studies that have investigated affirmative action attitudes at a HBCU, and only a handful of studies have focused on affirmative action attitudes of African American students at PWIs ( Aberson, 2007 ; Antwi-Boasiako & Asagba, 2005 ). Therefore, this study will contribute to the literature by addressing this gap in research. Antwi-Boasiako and Asagba (2005) found that the majority of African Americans at a PWI believed that race should be considered as a factor in college admission, although many felt that affirmative action discriminates against White students. Therefore, Black students at PWIs may be more likely to endorse more favorable attitudes towards affirmative action because they likely experience discrimination more frequently in the university context than Black students at HBCUs. On the other hand, one might expect HBCU students to endorse favorable attitudes towards affirmative action. If Black students receive an education that focuses on empowering them to succeed in a racist society, then societal inequities may be more salient, which could lead to stronger endorsement of affirmative action.

African American racial identity

In addition to the school environment, individual level factors related to identity may also impact attitudes toward affirmative action policies. Racial identity for African Americans serves as a lens through which meaning and significance are attached to racial experiences and being Black ( Cross, 1995 ; Sellers et al., 1998 ). One conceptualization of racial identity is the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI) by Sellers and colleagues (1997) . It posits an integrated framework of four dimensions that describe the meaning and significance of race with respect to the African American self-concept ( Sellers et al., 1998 ). There is not any endorsement of any particular definition of what it means to be Black, rather the emphasis is placed on the individual’s self-perception ( Sellers et al., 1998 ). The four dimensions include identity salience, race centrality, racial ideology, and the regard in which the individual holds about their own group. Racial salience refers to the extent that an individual’s race is an important part of their African American identity for the duration of a specific situation or event. The level of analysis is the particular situation or event. Race centrality refers to the extent to which an individual views race as a core part of his or her self-concept. This dimension is believed to be stable and non-situational. The third dimension, racial ideology, refers to the meaning that an individual attributes to being Black. Ideology includes values, characteristics, and attributes that the particular individual associates with Blackness. Four racial ideologies were hypothesized, which include the following: nationalist, oppressed minority, assimilation, and humanist. The nationalist ideology focuses on the distinctiveness of being Black. An individual with this ideology views the African American experience as being highly unique and different from any other social group. Nationalists believe that African Americans should be in control of their own fate and not seek input from non-Blacks. The oppressed minority ideology concentrates on the similarities of experiences between Blacks and other oppressed groups. A person who adopts an assimilationist ideology stresses the similarities between African Americans and the remainder of American society. This individual thinks of him or herself as an American and as a result attempts to be a part of mainstream society. A person espousing a humanist ideology emphasizes the similarities among all humans. The issues these individuals are concerned with center around broader concerns that face all humans (e.g. poverty, the environment, global politics). Lastly, racial regard signifies an individual’s affective and evaluative judgment of his or her racial group ( Sellers, Smith, et al., 1998 ). Sellers and colleagues delineate two types of regard – private and public. Private regard refers to how Blacks feel about other Blacks and being Black. Finally, public regard refers to the individual’s perception of what society thinks and feels about their group.

Racial identity and school type

The impact of racial identity has been examined alongside a number of different psychological variables ranging from drug attitudes ( Townsend & Belgrave, 2000 ), to academic achievement ( Awad, 2007 ). Researchers have also examined differences in racial identity at PWIs and HBCUs. Despite the common assumption that HBCUs offer more opportunities for cultural awareness and development, Cheatham et al. (1990) found that Black students at HBCUs did not report more developed levels of racial identity than Black students at PWIs. Their findings were corroborated by Cokley (1999) , who also found no differences in the importance of racial identity in his comparison of HBCUs and PWIs. However, institutional differences in racial identity attitudes were found where students from PWCUs endorsed higher assimilationist and humanist attitudes while HBCU students endorsed higher nationalist attitudes. Gilbert et al. (2006) also found that their HBCU sample endorsed high levels of racial pride. Anglin and Wade (2007) did not find any differences related to school racial composition. However, for both Black students at a PWI and Black students attending a racially diverse college, an internalized multicultural racial identity was associated with better college adjustment.

Affirmative action and college students

Research suggests that the formation of strong political attitudes remains somewhat fluid during young adulthood ( Alwin et al., 1991 ), particularly for racially and ethnically minoritized students ( Sidanius et al., 2008 ). However, once these political attitudes solidify, they are quite enduring into adulthood ( Alwin et al., 1991 ; Sears & Funk, 1999 ). Specifically, research has shown that affirmative action attitudes can evolve over the course of one’s college experience ( Park, 2009 ; Sidanius et al., 2008 ), suggesting that, among other factors, exposure to the liberal norms of one’s institution has the potential to influence attitudes toward policies that champion initiatives such as affirmative action. These findings suggest that the college years can be an impressionable time period for students, leading to the formation and crystallization of a new belief system and set of attitudes. Furthermore, it would behoove policymakers to analyze the attitudes towards affirmative action by college students as the majority represent the next generation of voters ( Park, 2009 ). Further, as previous research has demonstrated, college students’ political orientations and attitudes not only vary by ethnicity, but also as a function of time ( Park, 2009 ; Sidanius et al., 2008 ) and peer group exposure ( Astin, 1991 ). Therefore, it appears that stakeholders crafting policies on issues such as affirmative action would benefit from an understanding of the potential effect of the formative years of college on citizens as it is often a time for identity exploration and attitudes are the most pliable ( Gurin et al., 2002 ).

The purpose of the present study was to investigate variables that predict affirmative action attitudes in African Americans, specifically racial identity and school type. To the authors’ knowledge, no studies have compared affirmative action attitudes of Black students at PWIs and HBCUs in the United States. Another major aim of the study is to examine whether racial identity will interact with school racial composition to predict affirmative action attitudes. To gain a deeper understanding of African American college student’s attitudes towards affirmative action, research needs to move beyond demographic indicators and explore specific identity attributes and educational contexts.

Survey instruments

Participants were recruited from introductory psychology classes at either a predominately White, Midwestern state university (n = 58) or at a historically Black, Southern state university (n = 119). After obtaining informed consent for their participation, students anonymously completed questionnaire packets. Three survey instruments were used—one to assess racial identity, one to assess attitudes toward affirmative action, and a demographic questionnaire. Only those who self-identified as African-American on the demographic questionnaire were included in this study. This study was approved by the institutional review board for human subjects at both universities.

Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI; Sellers et al., 1997 ) was originally developed to measure racial identity according to the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI), which assumes race to be one of several relevant identities with varied significance and meaning. The model proposes that four dimensions characterize racial identity—centrality, ideology, regard, and salience. The MIBI attempts to measure only the three situation-stable dimensions of centrality, ideology, and regard. The original measure contains 56 questions divided into seven subscales: Centrality, Nationalistic Ideology, Oppressed Minority Ideology, Assimilationist Ideology, Humanist Ideology, Private Regard, and Public Regard. Sample items include ‘Being Black is an important reflection of who I am,’ ‘Blacks should strive to be full members of the American political system,’ and ‘Blacks and Whites can never live in true harmony because of racial differences.’ Responses are on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. Sellers et al. (1997) found coefficient alphas of .77 for Centrality, .60 for Private Regard, .79 for Nationalist Ideology, .76 for Oppressed Minority, .73 for Assimilationist Ideology, and .70 for Humanist Ideology subscales. However, the Public Regard subscale was not found to be internally consistent and was dropped, creating the 51-item, six subscale measure that was used in this study. Sellers et al. (1997) also found construct and predictive validity for the measure with predicted correlations between the subscales as well as with self-reported race-related behaviors. Further support for the reliability and validity of the MIBI was found by Cokley and Helm (2001) .

Attitudes Toward Affirmative Action Scale (ATAAS; Kravitz & Platania, 1993 ) is a six-question attitude scale designed to measure general affirmative action attitudes toward a specific group. Sample items include ‘Affirmative action is a good policy’ and ‘I would be willing to work at an organization with an affirmative action plan.’ The 5-point Likert-type answers range from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. The initial Cronbach’s alpha was reported to be .86 ( Kravitz & Platania, 1993 ) based on participation from Black college students while a more racially diverse college-age sample reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .92 ( Kravitz et al., 2000 ).

Demographic Questionnaire.

In the demographic questionnaire, participants indicated their age, year in school, sex, race, and socio-economic status.

Participants and procedures

A total of 32 freshmen, 70 sophomores, 50 juniors, and 25 seniors completed questionnaire packets with females comprising 68% of the total respondents. The mean age was 20.8 years old with an age range from 17 to 51 years old. The majority of the sample, 52.5%, self-reported their family’s socioeconomic status as middle class, with 30.5% as working class and the remainder upper middle and upper class. In terms of institutional characteristics, the racial composition of the student body at the PWI consisted of participants that identified as 73% White, 15% African American, 3% Latinx and 2% Asian American ( Campus Explorer, 2010 ). The average undergraduate enrollment at the PWI was approximately 16,700 ( Campus Explorer, 2010 ). For the HBU the racial composition consisted of 95% African American, 4% White, and 1% listed ‘other.’ The average enrollment for this university was 6,700 undergraduates ( Campus Explorer, 2010 ).

After generating sample demographics, we found correlations between school composition, self-identified sex, racial identity, and affirmative action attitudes. We found no significant differences between the samples on level of SES therefore it was not included in the analyses. We followed correlations with one-way ANOVAs to test for main effects and then a series of 2×2 ANOVAs to test for interactions. Finally, we used hierarchical regressions, also known as sequential regressions, to test which of our variables are important influences on attitudes toward affirmative action.

Hierarchical regressions allow us to determine if new variables, such as racial identity, helps improve the prediction of outcome variables, such as affirmative action attitudes, over and above an existing set of variables ( Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007 ). Hierarchical regression allows variables to be entered in blocks or steps based on an underlying causal model ( Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007 ). Our independent variables were school type (HBCU and PWI), self-identified sex (female & male), and the six racial identity subscales (race centrality, private regard, nationalist, oppressed minority, assimilationist, and humanistic). School type and self-identified sex were entered in the first step of the regression as these factors were hypothesized based on the literature review to influence the racial identity dimensions as well as the outcome variable, attitudes toward affirmative action. Entering these variables in a first step also allows for an estimate of the total effects of these variables on the outcome, including through indirect effects on variables entered in later steps ( Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007 ). By entering the racial identity subscales in the second step of the analysis, we are then also able to determine if these variables are able to explain a statistically significant amount of variance above and beyond the variance accounted for by school type and gender.

The purpose of this research was to determine whether self-identified sex, school composition, and racial identity dimensions impact college students’ affirmative action attitudes. Correlations among the study variables are displayed in Table 1 . Most notably, there was a significant negative correlation between affirmative action attitudes and school type ( r = −.245, p < .01), where those attending the HBCU were less likely to endorse affirmative action than those attending the PWI. In addition, there was a significant positive correlation between affirmative action attitudes and assimilation ( r = .151, p < .05), a significant positive correlation between affirmative action attitudes and oppressed minority ( r = .136, p < .05), and a significant positive correlation between affirmative action attitudes and centrality ( r = .192, p < .01). Specifically, students who endorsed assimilationist attitudes, oppressed minority attitudes, and felt that race was more central to their self-concept were more likely to endorse affirmative action than others.

Intercorrelations between the ATAAS, School Type, Sex, and MIBI Scales.

A one-way between subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated a significant main effect for school type, F (1,172) = 10.46, p < .01, and for racial centrality, F (1,172) = 5.95, p < .05. However, in the 2×2 ANOVAs to test for interaction, no significant interactions emerged between school type and self-identified sex or between school type and any of the racial identity dimensions, including centrality. This finding of a main effect but lack of interaction effects indicates that school type has the same effect on affirmative action attitudes for both males and females. Students of both sexes attending HBCUs were less likely to endorse affirmative action attitudes than students at PWIs. Also, those students who scored high on racial centrality, regardless of school type, were more likely to endorse affirmative action attitudes.

A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to determine the extent that racial identity dimensions predicts affirmative action attitudes. Students’ affirmative action attitudes were regressed on self-identified sex, school composition (HBU or PWI), and racial identity dimensions including centrality, private regard, assimilation, humanist, oppressed minority, and nationalist. Table 2 provides a summary of the hierarchical regression analysis. The first predictors entered in the regression, self-identified sex and school type, resulted in a statistically significant model, F (2,174) = 5.54, p < .01. A statistically significant increase in affirmative action attitudes emerged. Self-identified sex and school type accounted for 6% of the variance in affirmative action attitudes. Further examination of standardized coefficients indicates that school type is a powerful influence on affirmative action attitudes ( b = −.242, t [174] = −3.312, p = .001). According to this finding, students attending HBCUs are less likely to endorse affirmative action attitudes than students attending PWCUs. This analysis is in agreement with the earlier ANOVAs.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis of Predictors of Affirmative Action Attitudes

The second model, in which racial identity dimensions were entered into the second step in the regression equation, also resulted in a statistically significant model, F (8, 168) = 3.15, p < .01. A statistically significant increase in students’ affirmative action attitudes emerged. The racial identity dimensions accounted for an additional 7.1% of the variance in affirmative action attitudes. The entire model, accounting for 13% of the variance in attitudes, is a moderate effect size ( Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007 ). An examination of racial identity dimension coefficients indicates that after controlling for school type and sex, race centrality was the only racial identity domain that had a statistically significant impact on affirmative action attitudes (β = .190, t [168] = 2.227, p = .027). This finding indicates that when race is a central part of students’ identity, students are more likely to endorse affirmative action. However, other aspects of racial identity, such as ideology or private regard, had no such effect.

In the current study, the only significant predictors of affirmative action attitudes were school racial composition and the racial identity status of centrality. Black students at the PWI were more likely to endorse favorable attitudes towards affirmative action than their HBCU counterparts. This may be attributed to the increased salience of being a racially or ethnically minoritized student at a PWI. In the relative homogeneity of HBCUs, Black students may feel less of a need for affirmative action. As mentioned previously, Black students at HBCUs have reported feeling a stronger sense of belonging and connection ( Allen, 1992 ; Chavous, Harris, Rivas, Helaire, & Green, 2004 ), that their needs are reflected in extracurricular activities, and that they are supported by faculty ( Allen, 1992 ; Brown et al., 2001 ; Cokley, 2002 ). This supportive environment may decrease the perception that affirmative action is necessary. Black students at HBCUs may have fewer opportunities to experience discrimination and racial stereotypes and the social support systems available at HBCUs may help students cope with racism when it is experienced ( Gilbert et al., 2006 ).

In contrast, Black students at PWIs tend to encounter discrimination, stereotypes, and racism on a more regular basis ( Brown et al., 2001 ), which can make students feel that affirmative action policies or programs are necessary to ensure fair treatment. In addition, in the more racially homogenous environment of an HBCU, interracial competition may be less pronounced than in a PWI. In a PWI, both Black and White students may apply for the same positions in student organizations, internships, and scholarships, which may further increase the salience of affirmative action policies.

HBCU students may also be less likely to endorse affirmative action as they are focused on uplifting and supporting the Black community rather than finding ways to integrate into the White mainstream culture. That is, instead of ensuring fair treatment in White-dominated workplaces, more energy may be devoted to establishing successful Black organizations and businesses. While the results of the present study found no significant differences in nationalist racial ideology scores between the two institutions, other researchers have found that HBCU students are more likely to endorse nationalist attitudes compared to students in PWIs ( Cokley, 1999 ).

There were no institutional differences between students at PWIs and students at HBCUs in terms of importance of racial identity or centrality. These findings are consistent with those of Cokley (1999) who found no institutional differences in levels of centrality between HBCUs and PWIs. These findings also corroborate those of Schmermund et al. (2001) , who found that centrality was the most important predictor for affirmative action attitudes, though Schmermund et al. (2001) did not specify the racial compositions of the five schools that they examined. This study therefore extends those findings by finding similar relationships between centrality and affirmative action attitudes in both a PWI and HBCU. Although it may seem intuitive that African American students who have high centrality scores may be more likely to choose to attend an HBCU, the results of the current study suggest otherwise. Specifically, race centrality scores were equally variable at both the HBCU and PWI. Therefore, the reasons students may have for choosing to attend PWIs and HBCUs are more complex than racial identity alone. Accordingly, it is logical that there was a main effect of racial centrality on affirmative action attitudes found in the current study. Regardless of school type, students who endorse centrality attitudes are more likely to endorse positive attitudes towards affirmative action. Schmermund and colleagues (2001) argue that the more identified one is with one’s group, the more one will endorse policies that promote the group’s interest. Individuals who define themselves by their race may be more likely to believe there is a need for affirmative action.

Limitations of study and future research directions

There are limitations in this study to be considered. As the current sample consists of mostly university psychology students recruited from a Midwestern predominantly White institution (PWI) and a Southern historically Black college and university (HBCU), it limits the generalizability of these findings only to these specific regional areas and possibly these schools. Additionally, while affirmative action remains federal law the nature and implementation of affirmative action programs in education may vary from state to state, based upon legislative precedent.

It is also interesting to note that none of the ideology scales significantly predicted affirmative action attitudes, although it has been found that these racial identity attitudes vary by school racial composition ( Cokley, 1999 ; Gilbert et al., 2006 ). It is possible that differences in racial identity across school type depend on the construct being examined. One must exercise caution when generalizing research findings and making assumptions on the basis of school type alone, as school environments may interact with different variables in unique ways. However, we offer some possible explanations for the lack of significant findings in our study.

One reason for centrality being the only dimension of racial identity that emerged as significant may be that the subcategories of ideology are not mutually exclusive. That is, a given individual may partially endorse aspects of each ideology, rather than cleanly falling into one category or the other. Schmermund et al. (2001) note that people may hold different philosophies regarding racial identity that varies with situational or contextual factors. For example, a person may endorse humanist attitudes socially and date interracially while at the same time is an active member of an ethnic specific organization or club. While the focus of our study was on affirmative action, the MIBI ideology subscales consist of items that range widely in domain, such as social relationships, politics, morals, and spirituality. Therefore, a racial identity measure that focuses more narrowly on political attitudes would likely significantly predict affirmative action attitudes.

Despite the limitations, the current study significantly contributes to the understanding of African American’s endorsement of Affirmative Action attitudes. Given that African Americans are one of the groups that benefit from Affirmative Action, it is important to determine the factors that contribute to their endorsement of the policy. Policymakers should understand the attitudes towards affirmative action by college students as the majority represent the next generation of voters ( Park, 2009 ). Educational workshops about Affirmative Action may be tailored to African American students based on whether they are at an HBCU or PWI. Administrators at HBCUs may want to concentrate on the discrimination that is still present in the workforce and help HBCU students understand the importance and continued necessity of the policy. Further, higher education administrators, scholars, and others may be able to increase their understanding of the variability in African Americans’ Affirmative Action attitudes. Until equality among all groups is reached, Affirmative action programs will continue to be necessary. It is important to educate all groups about the benefits of diversity including those who are among the beneficiaries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

- Aberson CL (2007). Diversity experiences predict changes in attitudes toward affirmative action . Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology , 13 ( 4 ), 285–294. 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.285 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen W. (1992). The color of success: African-American college student outcomes at predominantly White and historically Black public colleges and universities . Harvard Education Review , 62 ( 1 ), 26–45. 10.17763/haer.62.1.wv5627665007v701 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alwin D, Cohen R, & Newcomb T (1991). Political attitudes over the life span: The bennington women after fifty years . University of Wisconsin Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anglin DM, & Wade JC (2007). Racial socialization, racial identity, and black students’ adjustment to college . Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology , 13 ( 3 ), 207–215. 10.1037/1099-9809.13.3.207 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antwi-Boasiako KB, & Asagba JO (2005). A preliminary analysis of African American college students’ perceptions of racial preferences and affirmative action in making admissions decisions at a predominantly White university . College Student Journal , 39 ( 4 ), 734–748. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A141167420/AONE?u=anon~eff92e74&sid=googleScholar&xid=4a821eef .. [ Google Scholar ]

- Astin AW (1991). Assessment for excellence: The philosophy and practice of assessment and evaluation in higher education . Macmillian. [ Google Scholar ]

- Awad GH (2007). The role of racial identity, academic self-concept, and self-esteem in the prediction of academic outcomes for African American students . Journal of Black Psychology , 33 ( 2 ), 188–207. 10.1177/0095798407299513 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Awad GH, Cokley KO, & Ravitch J (2005). Attitudes toward affirmative action: A comparison of color-blind versus modern racist attitudes . Journal of Applied Social Psychology , 35 ( 7 ), 1384–1399. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02175.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bergmann B. (1996). In defense of affirmative action . Basic Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bobo L. (1998). Race, interest, and beliefs about affirmative action: Unanswered questions and new directions . American Behavioral Scientist , 41 ( 7 ), 985–1003. 10.1177/0002764298041007009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bohr L, Pascarella E, Nora A, & Terenzini P (1995). Do Black students learn more at historically black or predominantly White colleges? Journal of College Student Development , 36 ( 1 ), 75–85. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown IIMC, Donahoo S, & Bertrand RD (2001). The Black college and the quest for educational opportunity . Urban Education , 36 ( 5 ), 553–571. 10.1177/0042085901365002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Campus Explorer. (2010). Campus Characteristics . https://www.campusexplorer.com

- Carter C. (1991). Reflections of an affirmative action baby . Basic Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chavous TM, Harris A, Rivas D, Helaire L, & Green L (2004). Racial stereotypes and gender in context: African Americans at predominantly Black and predominantly White Colleges . Sex Roles: A Journal of Research , 57 ( 1-2 ), 1–16. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.umich.edu/10.1023/B:SERS.0000032305.48347.6d . [ Google Scholar ]

- Cheatham HE, Slaney RB, & Coleman NC (1990). Institutional effects on the psychosocial development of African-American . Journal of Counseling Psychology , 37 ( 4 ), 453–458. 10.1037/0022-0167.37.4.453 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clayton SD, & Crosby FJ (2000). Justice, gender and affirmative action. In Crosby FJ & VanDeVeer C (Eds.), Sex, race & merit: Debating affirmative action in education and employment (pp. 1–10). The University of Michigan Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cokley K. (1999). Reconceptualizing the impact of college racial composition on African American students’ racial identity . Journal of College Student Development , 40 ( 3 ), 235–246. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cokley K. (2002). The impact of college racial composition on African American students’ academic self-concept: A replication and extension . The Journal of Negro Education , 71 ( 4 ), 288–296. 10.2307/3211181 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cokley KO, & Helm K (2001). Testing the construct validity of scores on the multidimensional inventory of black identity . Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development , 34 ( 2 ), 80–95. 10.1080/07481756.2001.12069025 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper BC (2017). Beyond respectability: The intellectual thought of race women . University of Illinois Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cortes KE (2010). Do bans on affirmative action hurt minority students? Evidence from the Texas top 10% plan . Economics of Education Review , 29 ( 6 ), 1110–1124. 10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.06.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crosby FJ, Iyer A, & Sincharoean S (2006). Understanding affirmative action . Annual Review of Psychology , 57 ( 1 ), 585–611. 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190029 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cross WE Jr. (1995). The psychology of nigrescence: Revising the cross model. In Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, Suzuki LA, & Alexander CM (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 93–122). Sage Publications, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis RB (1991). Social support networks and undergraduate student academic-success-related outcomes: A comparison of Black students on Black and White campuses. In Allen WR, Epps EG, & Haniff NZ (Eds.), College in Black and White: African American students in predominantly White and in PBI Black public universities (pp. 143–157). State University of New York Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dickson LM (2006). Does ending affirmative action in college admissions lower the percent of minority students applying to college? Economics of Education Review , 25 ( 1 ), 109–119. 10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.11.005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Federico CM, & Sidanius J (2002). Racism, ideology, and affirmative action revisited: The antecedents and consequences of “principled objections” to affirmative action . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 82 ( 4 ), 488–502. 10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.488 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fleming J. (1984). Blacks in college: A comparative study of students’ success in Black and in White institutions . Jossey-Bass. 47–63. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gasman M, & Abiola U (2016). Colorism within the historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) . Theory Into Practice , 55 ( 1 ), 39–45. 10.1080/00405841.2016.1119018 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilbert S, So D, Russell T, & Wessel T (2006). Racial identity and psychological symptoms among African Americans attending a historically Black university . Journal of College Counseling , 9 ( 2 ), 111–122. 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2006.tb00098.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gordon EK, Hawley ZB, Kobler RC, & Rork JC (2020). The paradox of HBCU graduation rates . Research in Higher Education , 62 , 332–358. 10.1007/s11162-020-09598-5 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greer TM, & Brown P (2011). Minority status stress and coping processes among African American college students . Journal of Diversity in Higher Education , 4 ( 1 ), 26. 10.1037/a0021267 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gurin P, Lehman JS, & Lewis E (2007). Defending diversity: Affirmative action at the university of Michigan . University of Michigan Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gurin PY, Dey EL, Hurtado S, & Gurin G (2002). Diversity and higher education: Theory and impact on educational outcomes . Harvard Educational Review , 72 ( 3 ), 330–367. 10.17763/haer.72.3.01151786u134n051 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartocollis A. (2020, February 18). The affirmative action battle at Harvard is not over . The New York Times . https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/18/us/affirmative-action-harvard.html [ Google Scholar ]

- Jackson State University. (2010). Campus Explorer . Retrieved June 15, 2001 from http://www.campusexplorer.com/colleges/0CA62D95/Mississippi/Jackson/Jackson-State-University/

- Joiner TE, & Walker RL (2002). Construct validity of a measure of acculturative stress in African Americans . Psychological Assessment , 14 ( 4 ), 462–466. 10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.462 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keller G. (1988). Review essay: Black students in higher education: Why so few? Planning for Higher Education , 17 ( 3 ), 43–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kimbrough R, Molock S, & Walton K (1996). Perception of social support, acculturation, depression and suicidal ideation among African American college students at predominantly Black and predominantly White universities . Journal of Negro Education , 65 ( 3 ), 295–307. 10.2307/2967346 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kravitz DA, Klineberg SL, Avery DR, Nguyen AK, Lund C, & Fu EJ (2000). Attitudes toward affirmative action: Correlations with demographic variables and with beliefs about targets, actions, and economic effects . Journal of Applied Social Psychology , 30 ( 6 ), 1109–1136. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02513.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kravitz DA, & Platania J (1993). Attitudes and beliefs about affirmative action: Effects of target and of respondent sex and ethnicity . Journal of Applied Psychology , 78 ( 6 ), 928–938. 10.1037/0021-9010.78.6.928 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis CW, Ginsberg R, Davis T, & Smith K (2004). The experiences of African American PhD students at a predominately white Carnegie I - research institution . College Student Journal , 38 ( 2 ), 231–245. [ Google Scholar ]

- Matsueda RL, & Drakulich K (2009). Perceptions of criminal injustice, symbolic racism, and racial politics . Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 623 ( 1 ), 163–178. 10.1177/0002716208330500 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). Digest of education statistics: 2018 (No. NCES 2020-009). https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/

- Negga F, Applewhite S, & Livingston I (2007). African American college students and stress: School racial composition, self-esteem and social support . College of Student Journal , 41 ( 4 ), 823–830. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson Laird T, Bridges BK, Morelon-Quainoo CL, Williams JM, & Holmes MS (2007). African American and Hispanic student engagement at minority serving and predominantly white institutions . Journal of College Student Development , 48 ( 1 ), 39–56. 10.1353/csd.2007.0005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Neville H, Heppner P, Ji P, & Thye R (2004). The relations among general and race-related stressors and psychoeducational adjustment in black students attending predominantly white institutions . Journal of Black Studies , 34 ( 4 ), 599–618. 10.1177/0021934703259168 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oh E, Choi C, Neville HA, Anderson CJ, & Landrum-Brow J (2010). Beliefs about affirmative action: A test of the group self-interest and racism beliefs models . Journal of Diversity in Higher Education , 3 ( 3 ), 167–176. 10.1037/a0019799 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Park JJ (2009). Taking race into account: Charting student attitudes towards affirmative action . Research in Higher Education , 50 ( 7 ), 670–690. 10.1007/s11162-009-9138-7 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peralta E. (2016, June 23). Supreme Court upholds University of Texas’ affirmative action program . NPR . https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/06/23/483228011/supreme-court-upholds-university-of-texas-affirmative-action-program [ Google Scholar ]

- Peterson J. (2003, June 23). U.S. Supreme Court rules on University of Michigan cases . University of Michigan News. https://news.umich.edu/us-supreme-court-rules-on-university-of-michigan-cases/ [ Google Scholar ]

- Pew Research Center. (2017). The partisan divide on political values grows even wider . https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2017/10/10-05-2017-Political-landscape-release-updt..pdf

- Pillay Y. (2005). Racial identity as a predictor of the psychological health of African American students at a predominantly white university . Journal of Black Psychology , 31 ( 1 ), 46–66. 10.1177/0095798404268282 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reeder MC, & Schmitt N (2013). Motivational and judgment predictors of African American academic achievement at PWIs and HBCUs . Journal of College Student Development , 54 ( 1 ), 29–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodgers KA, & Summers JJ (2008). African American students at predominantly White institutions: A motivational and self-systems approach to understanding retention . Educational Psychology Review , 20 ( 2 ), 171–190. 10.1007/s10648-008-9072-9 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schmerund A, Sellers R, Mueller B, & Crosby F (2001). Attitudes toward affirmative action as a function of racial identity among African American college students . Political Psychology , 22 ( 4 ), 759–774. 10.1111/0162-895X.00261 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sears D, & Funk C (1999). Evidence of the long-term persistence of adults’ political predispositions . Journal of Politics , 61 ( 1 ), 1–28. 10.2307/2647773 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sellers RM, Chavous TM, & Cooke DY (1998). Racial ideology and racial centrality as predictors of African American college students’ academic performance . Journal of Black Psychology , 24 ( 1 ), 8–27. 10.1177/00957984980241002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, & Smith MA (1997). Multidimensional inventory of black identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 73 ( 4 ), 805–815. 10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.805 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, & Chavous TM (1998). Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity . Personality and Social Psychology Review , 2 ( 1 ), 18–39. 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sidanius J, Levin S, van Laar C, & Sears DO (2008). The diversity challenge: Social identity and intergroup relations on the college campus . Russell Sage Foundation. [ Google Scholar ]

- Slaughter JE, Sinar EF, & Bachiochi PD (2002). Black applicants’ reactions to affirmative action plans: Effects of plan content and previous experience with discrimination . Journal of Applied Psychology , 87 ( 2 ), 333–344. 10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.333 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith AW (1991). Personal traits, institutional prestige, racial attitudes, and Black student academic performance in college. In Allen WR, Epps EG, & Haniff NZ (Eds.), College in Black and White: African American students in predominantly White and in PBI Black public universities (pp. 111–126). State University of New York Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Southern Illinois University. (2010). Retrieved June 15, 2010 from http://www.campusexplorer.com/colleges/0EC95205/Illinois/Carbondale/Southern-Illinois-University-Carbondale/

- Spencer Z. (2018). Black skin, white masks: Negotiating institutional resistance to revolutionary pedagogy and praxis in the HBCU. In Black women’s liberatory pedagogies (pp. 45–63). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steele S. (1990). The content of our character: A new vision of race in America . St. Martin’s Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steward R, Jackson MR, & Jackson JD (1990). Alienation and interactional styles in a predominantly white environment: A study of successful black students . Journal of College Student Development , 31 ( 6 ), 509–515. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swim JK, Hyers LL, Cohen L, & Ferguson MJ (2001). Everyday sexism: Evidence for its incidence, nature, and psychological impact from three daily diary studies . Journal of Social Issues , 57 ( 1 ), 31–53. 10.1111/0022-4537.00200 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn and Bacon. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tienda M, Leicht K, Sullivan T, Maltese M, & Lloyd K (2003). Closing the gap: Admissions and enrollments at Texas public flagships before and after affirmative action. Office of population research . Princeton University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Townsend TG, & Belgrave FZ (2000). The impact of personal identity and racial identity on drug attitudes and use among african American children . Journal of Black Psychology , 26 ( 4 ), 421–436. 10.1177/0095798400026004005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- University of California Office of Student Research. (1998). The admissions environment: Demographic trends , 1984–1997.

- Winkle-Wagner R, & McCoy DL (2018). Feeling like an “Alien” or “Family”? Comparing students and faculty experiences of diversity in STEM disciplines at a PWI and an HBCU . Race Ethnicity and Education , 21 ( 5 ), 593–606. 10.1080/13613324.2016.1248835 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Young VA, & Tsemo BH (eds.). (2011). From bourgeois to boojie: Black middle-class performances . Wayne State University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

Affirmative Action and University Fit: Evidence from Proposition 209

Proposition 209 banned the use of racial preferences in admissions at public colleges in California. We analyze unique data for all applicants and enrollees within the University of California (UC) system before and after Prop 209. After Prop 209, graduation rates increased by 4.4%. We present evidence that certain institutions are better at graduating more-prepared students while other institutions are better at graduating less-prepared students and that these matching effects are particularly important for the bottom tail of the qualification distribution. We find that Prop 209 led to a more efficient sorting of minority students, explaining 18% of the graduation rate increase in our preferred specification. Further, universities appear to have responded to Prop 209 by investing more in their students, explaining between 23-64% of the graduation rate increase.

The individual-level data on applicants to University of California campuses used in this paper was provided by the University of California Office of the President (UCOP) in response to a data request submitted by Professors Richard Sander (UCLA) and V. Joseph Hotz, while Hotz was a member of the UCLA faculty. We thank Samuel Agronow, Deputy Director of Institutional Research, UCOP, for his assistance in fulfilling this request and to Jane Yakowitz for her assistance in overseeing this process. Peter Arcidiacono and Esteban Aucejo acknowledge financial support from Project SEAPHE. We thank Kate Antonovics, Chun-Hui Miao, Kaivan Munshi, Justine Hastings, Peter Kuhn, Jesse Rothstein, David Card, Enrico Moretti, David Lam and seminar participants at Brown, IZA and UC Berkeley for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

- November 7, 2012

Published Versions

Affirmative action and university fit: evidence from Proposition 209 Peter Arcidiacono12*, Esteban Aucejo3, Patrick Coate4 and V Joseph Hotz125 * Corresponding author: Peter Arcidiacono [email protected] Author Affiliations For all author emails, please log on. IZA Journal of Labor Economics 2014, 3:7 doi:10.1186/2193-8997-3-7 Published: 15 September 2014

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Are Minority Students Harmed by Affirmative Action?

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, matthew m. chingos matthew m. chingos former brookings expert, senior fellow, director of education policy program - urban institute.

March 7, 2013

Affirmative action is back in the news this year with a major Supreme Court case, Fisher v. Texas. The question before the Court is whether the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause permits the University of Texas at Austin’s use of race in its undergraduate admissions process. The Court may declare the use of racial preferences in university admissions unconstitutional when it decides the case in the coming months, potentially overturning its decision in the landmark Grutter case decided a decade ago.

Accompanying the general subject of affirmative action in the spotlight is the “mismatch” hypothesis, which posits that minority students are harmed by the very policies designed to help them. Justice Clarence Thomas made this argument in his dissent in the Grutter case: “The Law School tantalizes unprepared students with the promise of a University of Michigan degree and all of the opportunities that it offers. These overmatched students take the bait, only to find that they cannot succeed in the cauldron of competition. And this mismatch crisis is not restricted to elite institutions.”

The mismatch idea is certainly plausible in theory. One would not expect a barely literate high-school dropout to be successful at a selective college; admitting that student to such an institution could cause them to end up deep in debt with no degree. But admissions officers at selective colleges obviously do not use affirmative action to admit just anyone, but rather candidates they think can succeed at their institution.

The mismatch hypothesis is thus an empirical question: have admissions offices systematically overstepped in their zeal to recruit a diverse student body? In other words, are they admitting students who would be better off if they had gone to college elsewhere, or not at all? There is very little high-quality evidence supporting the mismatch hypothesis, especially as it relates to undergraduate admissions—the subject of the current Supreme Court case.

In fact, most of the research on the mismatch question points in the opposite direction. In our 2009 book , William Bowen, Michael McPherson, and I found that students were most likely to graduate by attending the most selective institution that would admit them. This finding held regardless of student characteristics—better or worse prepared, black or white, rich or poor. Most troubling was the fact that many well-prepared students “undermatch” by going to a school that is not demanding enough, and are less likely to graduate as a result. Other prior research has found that disadvantaged students benefit more from attending a higher quality college than their more advantaged peers.

A November 2012 NBER working paper by a team of economists from Duke University comes to the opposite conclusion in finding that California’s Proposition 209, a voter-initiated ban on affirmative action passed in 1996, led to improved “fit” between minority students and colleges in the University of California system, which resulted in improved graduation rates. The authors report a 4.4-percentage-point increase in the graduation rates of minority students after Proposition 209, 20 percent of which they attribute to better matching.

At first glance, these results appear to contradict earlier work on the relationship between institutional selectivity and student outcomes. But the paper’s findings rest on a questionable set of assumptions, and a more straightforward reanalysis of the data used in the paper, which were provided to me by the University of California President’s Office (UCOP), yields findings that are not consistent with the mismatch hypothesis.

First, the NBER paper uses data on the change in outcomes between the three years prior to Prop 209’s passage (1995-1997) and the three years afterward (1998-2000) to estimate the effect of the affirmative action ban on student outcomes. Such an analysis is inappropriate because it cannot account for other changes occurring in California over this time period (other than simple adjustments for changes in student characteristics).

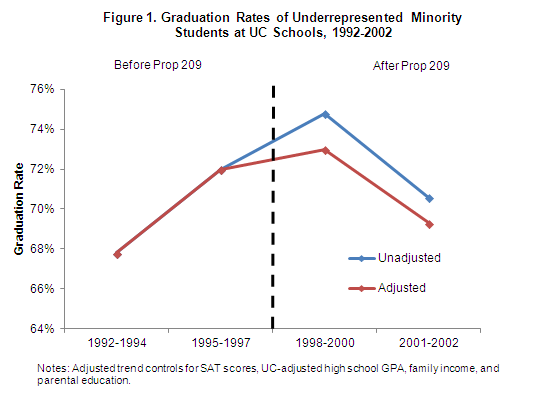

A key problem with the before-and-after method is that it does not take into account pre-existing trends in student outcomes. This is readily apparent in Figure 1, which shows that the graduation rates of underrepresented minority (URM) students increased by about four percentage points between 1992-1994 and 1995-1997, before the affirmative action ban. The change from 1995-1997 to 1998-2000 was smaller, at about three percentage points. The NBER paper interprets this latter change as the causal impact of Prop 209, but this analysis assumes that there would have been no change in the absence of Prop 209. If the prior trend had continued, then graduation rates would have increased another four points—in which case, the effect of Prop 209 was to decrease URM graduation rates by one percentage point.

Adjusting for student characteristics does not change this general pattern. The adjustment makes no difference in the pre-Prop 209 period, but explains about 36 percent of the increase in the immediate post-Prop 209 period (which is consistent with the NBER paper’s finding that changes in student characteristics explain 34-50 percent of the change). But if the 1992-1994 to 1995-1997 adjusted change was four points, and the 1995-1997 to 1998-2000 adjusted change was one point, then Prop 209 might be said to have a negative effect of three percentage points.

None of these alternative analyses of the effect of Prop 209 should be taken too seriously, because it is difficult to accurately estimate a pre-policy trend from only two data points. The bottom line is that there probably isn’t any way to persuasively estimate the effect of Prop 209 using these data. But this analysis shows how misleading it is in this case to only examine the 1995-1997 to 1998-2000 change, while ignoring the prior trend.