Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets

Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 5, 2020 • ( 1 )

There are a handful of indisputable influences on Eliot’s early and most formative period as a poet, influences that are corroborated by the poet’s own testimony in contemporaneous letters and subsequent essays on literature and literary works. Foremost among those influences was French symbolist poet Jules Laforgue, from whom Eliot had learned that poetry could be produced out of common emotions and yet uncommon uses of language and tone. A close second would undoubtedly be the worldrenowned Italian Renaissance poet Dante Alighieri, whose influences on Eliot’s work and poetic vision would grow greater with each passing year.

A third influence would necessarily come from among poets writing in Eliot’s own native tongue, English. There, however, he chose not from among his own most immediate precursors, such as Tennyson or Browning, or even his own near contemporaries, such as W. B. Yeats or Arthur Symons, and certainly not from among American poets, but rather from among poets and minor dramatists of the early 17th century, the group of English writers working in a style and tradition that has subsequently been identified as metaphysical poetry.

The word metaphysical is far more likely to be found in philosophical than literary contexts. Metaphysics is the branch of philosophical inquiry and discourse that deals with issues that are, quite literally, beyond the physical (meta- being a Greek prefix for “beyond”). Those issues are, by and large, focused on philosophical questions that are speculative in nature—discussions of things that cannot be weighed or measured or even proved to exist yet that have acquired great importance among human cultures. Metaphysics, then, concerns itself with the idea of the divine, of divinity, and of the makeup of what is called reality.

That said, it may be fair to suspect that poetry that is metaphysical concerns itself with those kinds of issues and concerns as well. The difficulty is that it both does and does not do that. Thus, the question of what metaphysical poetry does in fact do is what occupies Eliot’s attention in his essay to the point that he formulates out of his considerations a key critical concept that he calls the dissociation of sensibilities.

Eliot’s essay on the English metaphysical poets was originally published in the Times Literary Supplement as a review of a just-published selection of their poetry by the scholar Herbert J. C. Grierson titled Metaphysical Lyrics and Poems of the Seventeenth Century: Donne to Butler . In a fashion similar to the way in which Eliot launched into his famous criticism of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in “Hamlet and His Problems” by using an opportunity to review several new works of criticism on the play as a springboard to impart his own ideas, Eliot commends Grierson’s efforts but devotes the majority of his commentary otherwise to expressing his views on the unique contribution that metaphysical poetry makes to English poetry writing in general and on its continuing value as a literary movement or school. Indeed, as if to underscore his opposition to his own observation that metaphysical poetry has long been a term of either abuse or dismissive derision, Eliot begins by asserting that it is both “extremely difficult” to define the exact sort of poetry that the term denominates and equally hard to identify its practitioners.

After pointing out how such matters could as well be categorized under other schools and movements, he quickly settles on a group of poets that he regards as metaphysical poets. These include John Donne, George Herbert, Henry Vaughan, Abraham Henry Cowley, Richard Crashaw, Andrew Marvell, and Bishop King, all of them poets, as well as the dramatists Thomas Middleton, John Webster, and Cyril Tourneur.

As to their most characteristic stylistic trait, one that makes them all worthy of the title metaphysical, Eliot singles out what is generally termed the metaphysical conceit or concept, which he defines as “the elaboration (contrasted with the condensation) of a figure of speech to the farthest stage to which ingenuity can carry it.”

Eliot knows whereof he speaks. He himself was a poet who could famously compare the evening sky to a patient lying etherized upon an operating room table without skipping a beat, so Eliot’s admiration for this capacity of the mind—or wit, as the metaphysicals themselves would have termed it—to discover the unlikeliest of comparisons and then make them poetically viable should come as no surprise to the reader.

Eliot would never deny that, while it is this feature of metaphysical poetry, the far-fetched conceit, that had enabled its practitioners to keep one foot in the world of the pursuits of the flesh, the other in the trials of the spirit, such a poetic technique is not everyone’s cup of tea. The 18th-century English critic Samuel Johnson, for example, found their excesses deplorable and later famously disparaged metaphysical poetic practices in his accusation that in this sort of poetry “the most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together.” Eliot will not attempt to dispute Johnson’s judgment, though it is clear that he does not agree with it. (Nor should that be any surprise either. Eliot’s own poetic tastes and techniques had already found fertile ground in the vagaries of the French symbolists, who would let no mere disparity bar an otherwise apt poetic comparison.)

Rather, Eliot finds that this kind of “telescoping of images and multiplied associations” is “one of the sources of the vitality” of the language to be found in metaphysical poetry, and then he goes as far as to propose that “a degree of heterogeneity of material compelled into unity by the operation of the poet’s mind is omnipresent in poetry.” What that means, by and large, is that these poets make combining the disparate the heart of their writing. It is on that count that Eliot makes his own compelling case for the felicities of metaphysical poetry, so much so that he will eventually conclude by mourning its subsequent exile from the mainstream of English poetic practice. It is this matter of the vitality of language that the metaphysical poets achieved that most concerns Eliot, and it is that concern that will lead him, in the remainder of this short essay, not only to lament the loss of that vitality from subsequent English poetry but to formulate one of his own key critical concepts, the dissociation of sensibility.

The “Dissociation of Sensibility”

Eliot argues that these poets used a language that was “as a rule pure and simple,” even if they then structured it into sentences that were “sometimes far from simple.” Nevertheless, for Eliot, this is “not a vice; it is a fidelity to thought and feeling,” one that brings about a variety of thought and feeling as well as of the music of language. On that score—that metaphysical poetry harmonized these two extremes of poetic expression, thought and feeling, grammar and musicality —Eliot then goes on to ponder whether, rather than something quaint, such poetry did not provide “something permanently valuable, which . . . ought not to have disappeared.”

For disappear it did, in Eliot’s view, as the influence of John Milton and John Dryden gained ascendancy, for in their separate hands, “while the language became more refined, the feeling became more crude.” By way of a sharp contrast, Eliot saw the metaphysical poets, who balanced thought and feeling, as “men who incorporated their erudition into their sensibility,” becoming thereby poets who can “feel their thought as immediately as the odour of a rose.” Subsequent English poetry has lost that immediacy, Eliot contends, so that by the time of Tennyson and Browning, Eliot’s Victorian precursors, a sentimental age had set in, in which feeling had been given primacy over, rather than balance with, thought. Rather than, like these “metaphysical” poets, trying to find “the verbal equivalents for states of mind and feeling” and then turning them into poetry, these more recent poets address their interests and, in Eliot’s view, then “merely meditate on them poetically.” That is not at all the same thing, nor is the result anywhere near as powerful and moving as poetic statement.

While, then, the metaphysical poets of the 17th century “possessed a mechanism of sensibility which could devour any kind of experience,” Eliot imagines that subsequently a “dissociation of sensibility set in, from which we have never recovered.” Nor will the common injunction, and typical anodyne for poor poetry, to “look into our hearts and write,” alone provide the necessary corrective. Instead, Eliot offers examples from the near-contemporary French symbolists as poets who have, like Donne and other earlier English poets of his ilk, “the same essential quality of transmuting ideas into sensations, of transforming an observation into a state of mind.” To achieve as much, Eliot concludes, a poet must look “into a good deal more than the heart.” He continues: “One must look into the cerebral cortex, the nervous system, and the digestive tracts.”

CRITICAL COMMENTARY

The point of this essay is not a matter of whether Eliot’s assessment of the comparative value of the techniques of the English metaphysical poets and the state of contemporary English versification was right or wrong. By and large, Eliot is using these earlier poets, whom the Grierson book is more or less resurrecting, to stake out his own claim in an ageless literary debate regarding representation versus commentary. Should poets show, or should they tell? Clearly, there can be no easy resolution to such a debate.

Eliot would be the first to admit, as he would in subsequent essays, that a young poet, such as he was at the time he wrote the review at hand, will most likely condemn those literary practices that he regards to be detrimental to his own development as a poet. Whatever Eliot’s judgments in his review of Grierson’s book on the English metaphysical poets may ultimately reveal, they are reflections more of Eliot’s standards for poetry writing than of standards for poetry writing in general. That said, they should serve as a caution to any reader approaching an Eliot poem, particularly from this period, since he makes it clear that he falls on the side of representation as opposed to commentary and reflection in poetry writing.

In addition to its having enabled Eliot to stake out his own literary ground by offering, as it were, a literary manifesto for the times, replete with a memorable critical byword in the coinage dissociation of sensibility, as Eliot’s own prominence as a man of letters increased, this review should finally be credited with having done far more, over time, than Grierson’s scholarly effort could ever have achieved in bringing English metaphysical poetry and its 17th-century practitioners back to some measure of respectability and prominence. For that reason alone, this short essay, along with Tradition and the Individual Talent and Hamlet and His Problems , has found an enduring place not only in the Eliot canon but among the major critical documents in English of the 20th century.

Share this:

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: American Literature , Analysis of Metaphysical Poets , Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , Bibliography of Metaphysical Poets , Bibliography of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , Character Study of Metaphysical Poets , Character Study of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , Criticism of Metaphysical Poets , Criticism of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , Describe dissociation of sensibility , dissociation of sensibility , dissociation of sensibility eliot , dissociation of sensibility explain , dissociation of sensibility metaphysical poetry , dissociation of sensibility simple language , dissociation of sensibility summary , dissociation of sensibility term , eliot , Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , Essays of Metaphysical Poets , Essays of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , explain dissociation of sensibility , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Metaphysical Poets , Modernism , Notes of Metaphysical Poets , Notes of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , Plot of Metaphysical Poets , Plot of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , Poetry , Simple Analysis of Metaphysical Poets , Simple Analysis of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , Study Guides of Metaphysical Poets , Study Guides of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , Summary of Metaphysical Poets , Summary of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , Synopsis of Metaphysical Poets , Synopsis of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , T. S. Eliot , Themes of Metaphysical Poets , Themes of T.S. Eliot’s Metaphysical Poets , What is dissociation of sensibility

Related Articles

- Anglican Notables – Thomas Traherne (Musicians, Authors, & Poets) – 27 September – St. Benet Biscop Chapter of St. John's Oblates

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

A Brief Guide to Metaphysical Poets

Page submenu block.

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

The term “metaphysical,” as applied to English and continental European poets of the seventeenth century, was used by Augustan poets John Dryden and Samuel Johnson to reprove those poets for their “unnaturalness.” As Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote, however, “The unnatural, that too is natural,” and the Metaphysical poets continue to be studied and revered for their intricacy and originality.

John Donne , along with similar but distinct poets such as George Herbert , Andrew Marvell , and Henry Vaughn , developed a poetic style in which philosophical and spiritual subjects were approached with reason and often concluded in paradox. This group of writers established meditation—based on the union of thought and feeling sought after in Jesuit Ignatian meditation—as a poetic mode.

The Metaphysical poets were eclipsed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by R omantic and Victorian poets, but twentieth-century readers and scholars, seeing in the Metaphysicals an attempt to understand pressing political and scientific upheavals, engaged them with renewed interest. In his essay “ The Metaphysical Poets ,” T. S. Eliot , in particular, saw in this group of poets a capacity for “devouring all kinds of experience.”

Donne (1572–1631) was the most influential Metaphysical poet. His personal relationship with spirituality is at the center of most of his work, and the psychological analysis and sexual realism of his work marked a dramatic departure from traditional, genteel verse. His early work, collected in Satires and in Songs and Sonnets , was released in an era of religious oppression. His Holy Sonnets , which contains many of Donne’s most enduring poems, was released shortly after his wife died in childbirth. The intensity with which Donne grapples with concepts of divinity and mortality in the Holy Sonnets is exemplified in “ Sonnet X [Death, be not proud] ,” “ Sonnet XIV [Batter my heart, three person’d God] ,” and “Sonnet XVII [Since she whom I loved hath paid her last debt].”

Herbert (1593–1633) and Marvell (1621–1678) were remarkable poets who did not live to see a collection of their poems published. Herbert, the son of a prominent literary patron to whom Donne dedicated his Holy Sonnets , spent the last years of his short life as a rector in a small town. On his deathbed, he handed his poems to a friend with the request that they be published only if they might aid “any dejected poor soul.” Marvell wrote politically charged poems that would have cost him his freedom or his life had they been made public. He was a secretary to John Milton , and once Milton was imprisoned during the Restoration, Marvell successfully petitioned to have the elder poet freed. His complex lyric and satirical poems were collected after his death amid an air of secrecy.

browse poets from this movement

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

Metaphysical Poetry and Poets

- Favorite Poems & Poets

- Poetic Forms

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., English, Western Connecticut State University

- B.S., Education, Southern Connecticut State University

Metaphysical poets write on weighty topics such as love and religion using complex metaphors . The word metaphysical is a combination of the prefix of "meta" meaning "after" with the word "physical." The phrase “after physical” refers to something that cannot be explained by science. The term "metaphysical poets" was first coined by the writer Samuel Johnson in a chapter from his "Lives of the Poets" titled “Metaphysical Wit” (1779):

"The metaphysical poets were men of learning, and to show their learning was their whole endeavour; but, unluckily resolving to show it in rhyme, instead of writing poetry they only wrote verses, and very often such verses as stood the trial of the finger better than of the ear; for the modulation was so imperfect that they were only found to be verses by counting the syllables."

Johnson identified the metaphysical poets of his time through their use of extended metaphors called conceits in order to express complex thought. Commenting on this technique, Johnson admitted, "if their conceits were far-fetched, they were often worth the carriage."

Metaphysical poetry can take different forms such as sonnets , quatrains, or visual poetry, and metaphysical poets are found from the 16th century through the modern era.

John Donne (1572 to 1631) is synonymous with metaphysical poetry. Born in 1572 in London to a Roman Catholic family during a time when England was largely anti-Catholic, Donne eventually converted to the Anglican faith. In his youth, Donne relied on wealthy friends, spending his inheritance on literature, pastimes, and travel.

Donne was ordained an Anglican priest on the orders of King James I. He secretly married Anne More in 1601, and served time in jail as a result of a dispute over her dowry. He and Anne had 12 children before she died in childbirth.

Donne is known for his Holy Sonnets, many of which were written after the death of Anne and three of his children. In the Sonnet " Death, Be Not Proud ", Donne uses personification to speak to Death, and claims, “Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men”. The paradox Donne uses to challenge Death is:

"One short sleep past, we wake eternally And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.”

One of the more powerful poetic conceits that Donne employed is in the poem " A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning ". In this poem, Donne compared a compass used for drawing circles to the relationship he shared with his wife.

"If they be two, they are two so As stiff twin compasses are two: Thy soul, the fixed foot, makes no show To move, but doth, if the other do;"

The use of a mathematical tool to describe a spiritual bond is an example of the strange imagery which is a hallmark of metaphysical poetry.

George Herbert

George Herbert (1593 to 1633) studied at Trinity College, Cambridge. At King James I's request, he served in Parliament before becoming a rector of a small English parish. He was noted for the care and compassion he gave to his parishioners, by bringing food, the sacraments, and tending to them when they were ill.

According to Poetry Foundation, "on his deathbed, he handed his poems to a friend with the request that they are published only if they might aid 'any dejected poor soul.'" Herbert died of consumption at the young age of 39.

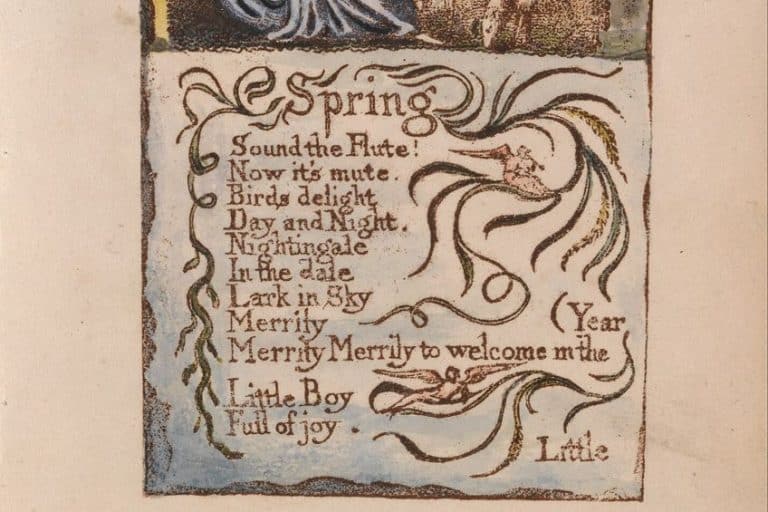

Many of Herbert’s poems are visual, with space used to create shapes that further enhance the poem's meaning. In the poem " Easter Wings ", he used rhyme schemes with the short and long lines arranged on the page. When published, the words were printed sideways on two facing pages so that the lines suggest the outspread wings of an angel. The first stanza looks like this:

"Lord, who createdst man in wealth and store, Though foolishly he lost the same, Decaying more and more, Till he became Most poore: With thee O let me rise As larks, harmoniously, And sing this day thy victories: Then shall the fall further the flight in me."

In one of his more memorable conceits in the poem titled "The Pulley ", Herbert uses a secular, scientific tool (a pulley) to convey a religious notion of leverage that will hoist or draw mankind towards God.

"When God at first made man, Having a glass of blessings standing by, 'Let us,' said he, 'pour on him all we can. Let the world’s riches, which dispersèd lie, Contract into a span.'"

Andrew Marvell

Writer and politician Andrew Marvell's (1621 to 1678) poetry ranges from the dramatic monologue "To His Coy Mistress" to the praise-filled On Mr. Milton's “Paradise Lost”

Marvell was a secretary to John Milton who sided with Cromwell in the conflict between Parliamentarians and the Royalists that resulted in the execution of Charles I. Marvell served in the Parliament when Charles II was returned to power during the Restoration. When Milton was imprisoned, Marvell petitioned to have Milton freed.

Probably the most discussed conceit in any high school is in Marvell's poem "To His Coy Mistress." In this poem, the speaker expresses his love and uses the conceit of a “vegetable love” that suggests slow growth and, according to some literary critics, phallic or sexual growth.

"I would Love you ten years before the flood, And you should, if you please, refuse Till the conversion of the Jews. My vegetable love should grow Vaster than empires and more slow;"

In another poem, " The Definition of Love ", Marvell imagines that fate has placed two lovers as North Pole and the South Pole. Their love may be achieved if only two conditions are fulfilled, the fall of heaven and the folding of the Earth.

"Unless the giddy heaven fall, And earth some new convulsion tear; And, us to join, the world should all Be cramped into a planisphere."

The collapse of the Earth to join lovers at the poles is a powerful example of hyperbole (deliberate exaggeration).

Wallace Stevens

Wallace Stevens (1879 to 1975 ) attended Harvard University and received a law degree from New York Law School. He practiced law in New York City until 1916.

Stevens wrote his poems under a pseudonym and focused on the transformative power of the imagination. He published his first book of poems in 1923 but did not receive widespread recognition until later in his life. Today he is considered one of the major American poets of the century.

The strange imagery in his poem " Anecdote of the Jar " marks it as a metaphysical poem. In the poem, the transparent jar contains both wilderness and civilization; paradoxically the jar has its own nature, but the jar is not natural.

"I placed a jar in Tennessee, And round it was, upon a hill. It made the slovenly wilderness Surround that hill. The wilderness rose up to it, And sprawled around, no longer wild. The jar was round upon the ground And tall and of a port in air."

William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams (1883 to 1963) began writing poetry as a high school student. He received his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania, where he became friends with the poet Ezra Pound.

Williams sought to establish American poetry that centered on common items and everyday experiences as evidenced in “The Red Wheelbarrow.” Here Williams uses an ordinary tool such as a wheelbarrow to describe the significance of time and place.

"so much depends upon a red wheel barrow"

Williams also called attention to the paradox of the insignificance of a single death against a large expanse of life. In the poem Landscape with the Fall of Icarus , he contrasts a busy landscape—noting the sea, the sun, springtime, a farmer plowing his field—with the death of Icarus:

"unsignificantly off the coast there was a splash quite unnoticed this was Icarus drowning"

- 10 Classic Poems for Halloween

- Overview of Imagism in Poetry

- A Classic Collection of Bird Poems

- What Is Enjambment? Definition and Examples

- What is Conceit?

- Biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Poet and Activist

- An Introduction to Free Verse Poetry

- My Candle Burns at Both Ends: The Poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Biography of Allen Ginsberg, American Poet, Beat Generation Icon

- Writing About Literature: Ten Sample Topics for Comparison & Contrast Essays

- Patriotic Poems for Independence Day

- 10 Classic Poems on Gardens and Gardening

- What Is Ekphrastic Poetry?

- Character Analysis: Dr. Vivian Bearing in 'Wit'

Metaphysical Poetry – Capturing the Otherworldly in Verse

Sometimes a type of poetry is “of a certain time”, and that is the case with today’s point of focus: metaphysical poetry. So, what is metaphysical poetry then? This will be our question of focus today. We will have a look at the history of this form of poetry, some of the characteristics for which it has become known, some of the goals that it attempted to achieve, and a few examples of metaphysical poetry to help explain and explore the concept in greater depth. This article should be of help to those who want to know about metaphysical poetry but have not yet had the time to do so. If this describes your interest in metaphysical poetry, you have some learning to do!

Table of Contents

- 1 A Look at Metaphysical Poetry

- 2 A Summary of Metaphysical Poetry

- 3 The History of Metaphysical Poetry

- 4 The Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry

- 5 The Goals of Metaphysical Poetry

- 6.1 The Collar (1633) by George Herbert

- 6.2 The Flea (1633) by John Donne

- 6.3 To His Coy Mistress (1681) by Andrew Marvell

- 7.1 What Is Metaphysical Poetry?

- 7.2 Where Did Metaphysical Poetry Originate?

- 7.3 What Are the Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry?

- 7.4 Does Metaphysical Poetry Still Exist?

- 7.5 What Are Some Famous Examples of Metaphysical Poetry?

A Look at Metaphysical Poetry

Back when I used to teach high school, and even when I provided educational material to university students, I would sometimes need to explain that certain forms of literature and theory come from a very specific time and place. That is the case with metaphysical poetry. Sometimes, something can only really be understood based on its particular goals during a particular period. That isn’t to say that metaphysical poetry cannot be enjoyed without also knowing your history, but it can perhaps be better enjoyed when we understand where it comes from. This will be part of our focus today.

A Summary of Metaphysical Poetry

There are many different types of poetry out there, and some of them are marked by very specific definitions. This is generally the case with metaphysical poetry. So, what is metaphysical poetry? We’ll be answering that in-depth throughout this article, but here’s a quick look for those who may need it:

- Metaphysical poetry is an intellectually complex form of poetry. Some of the principal characteristics of metaphysical poetry lie in its use of more intellectually complex ideas that are portrayed through elaborate forms. This form of poetry is known for tackling tough and interesting issues.

- Metaphysical poetry originated in 17 th century England. This form of poetry attained its name retrospectively. The metaphysical poets did not call themselves this, and it was instead applied by later thinkers to help describe this particular trend in 17 th -century poetry.

- Metaphysical poetry still exists in some form. While the actual movement that came to be known as metaphysical poetry has come to an end, the influence of this form would have an effect on later writers. While we could argue that later writers who used a similar style to the metaphysical poets are not writing true metaphysical poetry, we could also argue in the other direction.

This has been a summary of metaphysical poetry, which, in my experience as a literature teacher, is something that can be a very useful thing. Many students can easily forget certain aspects of a topic.

A brief and bullet-pointed list can be of great help to those who need a quick leg up.

The History of Metaphysical Poetry

The beginnings of metaphysical poetry emerged in the 17 th century in England. However, these writers did not self-identify as metaphysical poets. Instead, this label came several decades later while other writers were attempting to define this earlier period in time. Many trends in literature, and other areas, can only truly be seen in retrospect.

Some of the poets who were identified as the primary metaphysical poets included figures such as John Donne, Andrew Marvell, and George Herbert. There were several others, but the list of writers who have been labeled as metaphysical poets is a relatively short one. However, this does present us with a question: Does metaphysical poetry still exist today?

The answer is both a yes and a no. You see, these poets were labeled as a historical group, but they would go on to influence many others who made use of ideas and techniques that the metaphysical poets developed. However, this does not necessarily make those people metaphysical poets but rather those who were simply influenced by them. This can become a difficult thing to determine for certain, but it definitely is an interesting question to ponder.

The Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry

The principal characteristics of metaphysical poetry have to do with its examination of philosophical ideas and concepts. However, while this is one of the central ideas, it is far from the only idea that is often explored in this type of poetry. In addition to the use of philosophical ponderings, metaphysical poetry also made use of more elaborated forms of figurative language, paradoxical structures, strange imagery, and a more intellectual overall focus. Interestingly, many examples of metaphysical poetry also made use of more colloquial language and expression, including the use of more relaxed forms of meter. This means that while metaphysical poetry was noted for its use of philosophical ideas, it also wrapped those ideas in more understandable language.

This is an interesting choice as many other intellectual writers, such as T.S. Eliot, would entirely ignore the idea of ease of understanding in favor of immense complexity.

The Goals of Metaphysical Poetry

What was the point of metaphysical poetry in the first place? Well, it must be remembered that this form of poetry was not defined during its major period. Instead, it would only come to be defined by those who lived decades later. However, the poets who came to be seen as the metaphysical poets did have a number of goals that they explored in their poetry.

Some of the more common of these goals was the exploration of philosophical ideas. They would often try to understand aspects of the world, to focus on spirituality, science, and morality. They explored concepts such as free will and the very nature of the world as a whole. This is also why they came to be known as the metaphysical poets. Metaphysics is a branch of philosophy that focuses on understanding reality itself and is often some of the earliest philosophy that is taught because it serves as a backbone against which other concepts can be later explored.

During my days as an English and literature teacher, I would often inject these kinds of philosophical inquiries into my teaching. We may think that younger people do not consider philosophical questions, but this is not the case. Many people want to explore and discuss these kinds of ideas, but there is seldom an avenue through which they can be allowed to do so. Poetry provides such an avenue. We cannot simply look at poetry from a formal perspective and see how it uses words, symbols, and structure, we also need to look at the ideas that it is presenting to us.

This is what metaphysical poetry allows us to do. Well, that and the use of certain formal elements. While metaphysical poetry was used to explore these kinds of philosophical ideas, it was also there to use figurative language in innovative ways, to alter the way poetic structure was used, and so on.

Many different aspects of metaphysical poetry are worth discussing.

Examples of Metaphysical Poetry

There are quite a number of examples of metaphysical poetry in the world, but we’ll only be having a look at three of them. These poems represent some of the most famous examples of metaphysical poetry from three of the figures who are seen as integral to the movement as a whole. Hopefully, this should serve as a way to aid in answering the question: “What is metaphysical poetry?” If you’d like an answer to that, let’s have a look at some of these particular instances.

The Collar (1633) by George Herbert

The Collar is a famous instance of metaphysical poetry because it examines ideas to do with spirituality, freedom, and pleasure. It explores the constraints that are placed upon those in religious positions and the desires that come with wishing for a guilt-free life in which pleasure is celebrated rather than rejected. This is a good instance of metaphysical poetry because it makes use of an extended metaphor, uses more abstract themes, and is written in a more dramatic monologue style.

This poem has come to be seen as one of the best-known instances of metaphysical poetry, and the ideas that it explores are indicative of the poetic variety as a whole.

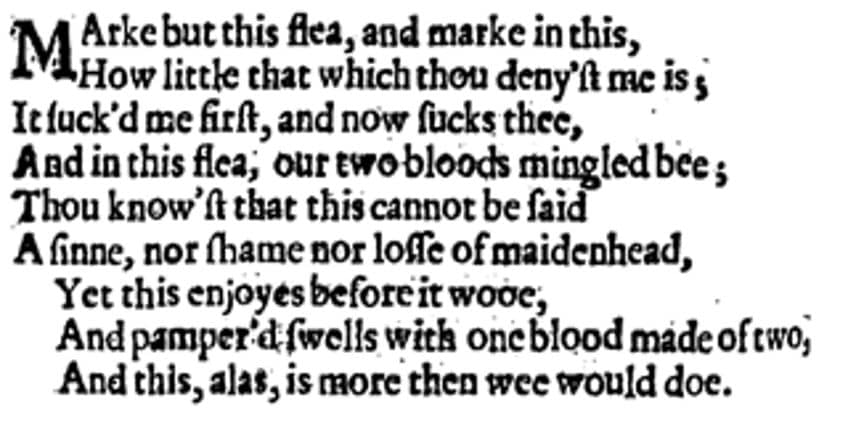

The Flea (1633) by John Donne

The Flea is a poem about sex. This is one of the more common areas that metaphysical poetry would often explore, and the last poem on this list is also an instance of this particular topic. In this poem, the poet uses the metaphor of a flea to show that the drinking of blood is something natural to the flea just as sex is something natural to the human. The use of an extended metaphor, candid explorations of sexual themes, and a wittier delivery are indicative of the kinds of work for which the metaphysical poets became so well known.

This is another of the metaphysical poems that has become a standout example of the form.

To His Coy Mistress (1681) by Andrew Marvell

To His Coy Mistress is not only one of the best-known metaphysical poems, but also a famous carpe diem poem. This means that the poem is all about seizing the day and living as if every day is potentially your last. In this particular case, like with many metaphysical poems, the act of seizing the day comes in the form of sexual pleasure. The speaker tries to convince someone to have sex because we’re all going to die eventually anyway, and wouldn’t it have been a waste to maintain chastity when there was so much pleasure to be had? This is a common theme explored in many examples of metaphysical poetry.

In this article on metaphysical poetry, we have looked at the definition of this concept as well as the history of the form, some of its characteristics and goals, and a handful of examples of metaphysical poetry. This should be beneficial to anyone who wants to learn more about the time of the metaphysical poets and the kinds of work that they produced. Hopefully, this has managed to help those with these very same desires. However, to truly experience metaphysical poetry, you should read more examples of this form.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is metaphysical poetry.

When it comes to an understanding of metaphysical poetry, we can somewhat see the idea reflected in the name itself. This is a form of poetry that focuses on intellectual content that uses elaborate language, complex structures, and often strange imagery. The label was applied more retrospectively to several writers.

Where Did Metaphysical Poetry Originate?

The origins of metaphysical poetry can be traced to England in the 17 th century. This term was used later to describe several poets who were not connected to one another yet had similar goals in their poetry. The poets labeled as metaphysical poets did not use this term to describe themselves.

What Are the Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry?

Some of the standard features of metaphysical poetry lay in the use of more intellectual topics, elaborate forms of figurative language, highly complex forms and ideas, and so on. The name of this poetic form reflects the more philosophical inclinations of the poets who have come to be seen as metaphysical poets.

Does Metaphysical Poetry Still Exist?

This poetic form still exists, but not in the way that it did in the 17 th century in England. Instead, modern writers have taken inspiration from traditional metaphysical poetry and made use of similar ideas and formal arrangements. So, one could also argue that modern writers who use these ideas are not actually true metaphysical poets.

What Are Some Famous Examples of Metaphysical Poetry?

There are several writers who came to be known as the metaphysical poets. Some of their best-known works include The Collar (1633) by George Herbert, The Flea (1633) by John Donne, and To His Coy Mistress (1681) by Andrew Marvell. However, there are more than only these that have been shown.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Metaphysical Poetry – Capturing the Otherworldly in Verse.” Art in Context. January 18, 2024. URL: https://artincontext.org/metaphysical-poetry/

van Huyssteen, J. (2024, 18 January). Metaphysical Poetry – Capturing the Otherworldly in Verse. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/metaphysical-poetry/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Metaphysical Poetry – Capturing the Otherworldly in Verse.” Art in Context , January 18, 2024. https://artincontext.org/metaphysical-poetry/ .

Similar Posts

How to Write a Free Verse Poem – A Beginner’s Guide

Connotation in Poetry – The Art of Suggestion Through Words

Prose Poetry – Explore This Strange and Unique Poem Form

Spring Poems – Celebrating the Birth of New Life With Poetry

Metaphor Poems – The Top 15 Famous Examples

Protest Poetry – The Characteristics of Social Activism Prose

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- _G.C.E.(A/L) Past Papers

- _G.C.E. (O/L) Past Papers

- _Presentations

- _Worksheets

- E-book Store

- _Litspring Community

Understanding Metaphysical Poetry

Students who learn literature sometimes find it difficult to unwrap the meaning of metaphysical poems. Therefore, it is necessary to know a bit of background related to metaphysical poetry. In this post you will be able to understand what is metaphysical poetry, how it came to the practice and what are the characteristics of it.

What is Metaphysics?

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that deals with the first principles of things, including abstract concepts such as being, knowing, identity, time and space. (Definitions from Oxford Languages)

Metaphysical poetry

The term ‘metaphysical poetry’ came into being after the poets, including John Donne (1572-1631), to whom the term is applied is dead. At first the term metaphysical poem was used to refer to Donne and others not as commendable or favourable term but as a sort of literary nick name. John Dryden writing about John Donne in 1693 had said John Donne affects the metaphysics not only in his satire, but also in his amorous verses. Later on Samuel Johnson (1709 – 1784) writing about John Donne and other poets of similar style says: “About the beginning of the seventeenth century there appeared a race of writers who may be termed the metaphysical poets. In fact, when Johnson said that he meant that he did not consider these poets truly metaphysical.

So the question is who were the metaphysical writers whom according to John Dryden and Samuel Johnson, Donne and others tried to imitate?

Latin writers Seneca (45 B.C. to 65 B.C.) Roman philosopher and writer of tragedies and Tacitus (C 55 – 120), the Roman Historian were at the time of Dryden and Johnson, held as the models of good writing. The writing was full of matter with less words, but hard to read. Poets like John Donne had tried to imitate the writing of these men in their poetry. They thought that good poetry should be close packed and dense with meaning, something to be chewed and digested.

The metaphysical approach to poetry

The new attitude to poetry should be understandable when we think of this period, this was Renaissance period (14 th , 15 th and 16 th centuries) when everything was questioned and new meanings were forged in every sphere of knowledge. So in poetry traditional courtly love style was questioned. In place of its simplicity and musicality with no much meaning. The poet tried to infuse their poetry with meaning with “more matter and less words”. This attitude of giving more meaning and less words should be still clearer to us when we know that Renaissance was a revival of Greek and Roman literature. So, naturally the Renaissance poets like John Donne were influenced by classical Roman authors as Seneca and Tacitus and new meaning were forged in every sphere of knowledge.

Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry

There are in fact a few notable ones in the characteristic qualities of metaphysical poetry. First: T.S. Eliot in his essay on metaphysical poets said “A thought to Donne was an experience. It modified his sensibility.” This means that one of the most important characteristics of metaphysical poetry is its thought content. Unlike in Courtly Love poetry, in metaphysical poetry the poems are full of rich ideas. The reader is held to an idea or a line of argument. The reader has to pay attention to the thought or the argument and read on. This cohesive character of metaphysical poetry with a binding argument or an idea in fact made contemporaries of Donne and others call this poetry not metaphysical but ‘strong – lines.’

The second characteristic of metaphysical poetry is the presence of conceits. Here the word conceit is not to be taken in its modern sense as excessive pride in one’s position or abilities. Rather in metaphysical poetry it means a comparison and that too, a comparison of apparently unlike things. We have a typical conceit in Donne’s poem Valediction Forbidding Mourning when he compares the two lovers to a pair of compasses. in the poem Song: Sweetest Love I do not goe also there is a similar conceit when Donne compares himself as the husband to the sun.

Conceits were very common in Courtly Love poetry, but they were different from conceits in Donne’s poems in that they were conventional comparisons like comparing the face of the lady to a garden, the hair to threads of gold, eyes to brightest stars and cheeks to red roses. When Donne deviated from Courtly Love tradition he gave up conventional imagery and introduced new ones – unconventional imagery. The images Donne used had not been used before because no one had seen a comparison between them and their referents. So there is a certain freshness in Donne’s conceits.

The third characteristic of metaphysical poetry is that a poem arises from a moment of experience or situation. In other words, the subject of metaphysical poetry is always a real situation and not an artificial situation as in Courtly Love poetry. So all Donne’s poems are about moments or situations of real life like bidding farewell, experiencing real love, facing death or knowing God. It is therefore from moments or situations of real life that the need to argue or compare arises.

Reference: Rev. Fr. Herman Fernando (Critical Notes on A/L Poems)

If you have more points to add to the post, please be kind enough to add them in the comment section. By doing so, you help the readers to widen the scope of the reader and us to improve the quality of our blog.

You may like these posts

Post a comment, get new posts by email:.

- B.A. Ja'pura 10

- Drama Scripts 4

- G.C.E (A/L) Literature 56

- G.C.E (O/L) Literature 75

- Students' Corner 7

Visit Us on Social Media

Featured post.

Lesson of Caring Elders in Leave Taking by Cicil Rajendra

Cicil Rajendra is a Malaysian poet, lawyer in profession says that his poems tend …

Total Pageviews

- Watch us on YouTube

Weekly Popular

Analysis of Farewell to Barn and Stack and Tree by A.E. Housman

Summary of the Play Twilight of a Crane by Junji Kinoshita

Analysis of War is Kind by Stephen Crane

Big Match by Yasmine Gooneratne Explained

Menu footer widget.

- Privacy Policy

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About The Review of English Studies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Books for Review

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Metaphysics.

- < Previous

Shakespeare’s Metaphysical Poem: Allegory, Metaphysics, and Aesthetics in ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ted Tregear, Shakespeare’s Metaphysical Poem: Allegory, Metaphysics, and Aesthetics in ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, The Review of English Studies , Volume 74, Issue 316, October 2023, Pages 635–651, https://doi.org/10.1093/res/hgad055

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Long treated as a poetic curio or a biographical riddle, Shakespeare’s poetic contribution to the 1601 Loves Martyr —usually known as ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’—has recently been reclaimed as an experiment in metaphysical poetry. This essay sets out to ask what that means: for the poem, for metaphysical poetry, and for metaphysics itself. It argues that Shakespeare draws on the language of metaphysics, and its canonical problems, to test the relationship between poetic and philosophical thinking. It follows the poem as it charts the efforts, and failures, of both allegory and metaphysics to apprehend the thought-defying love between phoenix and turtle. It shows how that love engages the dilemma of the particular and the universal, a dilemma native to metaphysics since Aristotle, but felt most acutely in the realm of aesthetic experience. And it suggests that, in sounding out the limits of metaphysical reason, Shakespeare’s poem allows for poetry to think in a way that metaphysics cannot. ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ ends in mourning: for the death of phoenix and turtle, and for the demise of the metaphysical transcendentals they seemed in hindsight to uphold. That mourning might nonetheless offer poetry its vocation, as the space where reason might remember and reflect on the object of its loss.

When, in 1601, John Marston read through Shakespeare’s latest poem, the word that came to his mind was metaphysical . ‘O Twas a mouing Epicedium ’, he enthused, in the contribution to the 1601 Loves Martyr placed immediately after Shakespeare’s own. 1 His praise is shared between that epicedium and its subjects, the phoenix and turtle-dove that he, like Shakespeare, sets out to memorialize. Marston soon warms to his theme: Lo now; th’xtracture of deuinest Essence , The Soule of heauens labour’d Quintessence , ( Peans to Phoebus ) from deare Louer’s death, Takes sweete creation and all blessing breath. ( LM , 2A1 r )

Whatever issues from these lovers’ death is more refined than essence, more ensouled than quintessence, against whose creation the heavens’ own alchemy looks laboured. That labour, the sheer effort of working out what has just happened, becomes the subject of Marston’s poem, and draws him towards the rich but recondite domain of metaphysics: Raise my inuention on swift Phantasie, That whilst of this same Metaphisicall God, Man, nor Woman, but elix’d of all My labouring thoughts, with strained ardor sing, My Muse may mount with an vncommon wing. (2A1 r )

Squeezed out in italics like the poem’s other terms of art, ‘ Metaphisicall ’ hangs at the end of the line, as though sucking the air out of Marston’s lungs. As the poet recovers, he finds it hard to work out what, exactly, might be metaphysical here: ‘God’, ‘Man’, and ‘Woman’ are all possibilities, but with nor , all are revoked as inadequate to the task. The result is a word left somewhere between an adjective and a noun, so transcending all substantives that it becomes almost substantial in itself. Marston follows Shakespeare to the heights of metaphysics; but what is metaphysical about Shakespeare’s poem, it seems, is all but unspeakable.

Marston enjoyed ramping up his diction like this. By 1601, it had become a hallmark of his style, which grazes along the knife-edge of grandiloquence and pretension: polysyllabic, neologistic, and conspicuously philosophical. ‘No speech is Hyperbolicall, | To this perfection blessed’, he claims, and he puts that claim to the test. Compared to that perfection, ‘that boundlesse Ens ’, ‘all Beings’ are ‘deck’d and stained’; ‘ Ideas that are idly fained | Onely here subsist inuested’ ( LM , 2A1 v ). Lines like these made Marston a pioneer in what Patrick Cheney has recently christened the ‘metaphysical sublime’, a poetry that propels itself into raptures beyond thinking’s customary bounds. 2 Indeed, his contribution to Loves Martyr is the first time a seventeenth-century poem identifies itself, albeit by association, as metaphysical. The word’s application to a certain style of poetry—smart, witty, metaphorically and conceptually audacious—predates its usage by Samuel Johnson, and earlier by John Dryden, both of them usually credited with bequeathing the idea of ‘metaphysical poetry’ to literary criticism. As early as the 1640s, William Drummond was already defending poetry against those who ‘endevured to abstracte her to Metaphysicall Ideas, and Scholasticall Quiddityes’. 3 Drummond was most likely thinking of John Donne, whose Poems had recently appeared in print; but he may equally have been thinking of Loves Martyr , which appears on his reading list from 1606. 4 If Marston can be read as a metaphysical poet avant la lettre , so too can the poet he celebrates in such glowing terms. Shakespeare’s poem in Loves Martyr is untitled; it merely begins, with disorienting simplicity, ‘Let the bird of lowdest lay’. Since the nineteenth century, it has been known as ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’—a title which, however convenient, risks begging the question, in distinguishing from the outset two lovers whose divisions are rendered so massively vexing. Mired for much of its existence in historical and biographical speculation regarding its cast of characters, the poem has more recently been reclaimed as a vital document in literary history. ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, James Bednarz argues, is ‘the first great published “metaphysical” poem in English’. 5

Following Marston’s cue, this essay sets out to read Shakespeare’s poem as an experiment in metaphysical poetry, and to understand what that might mean: for the poem, for metaphysical poetry, and for metaphysics itself. These terms are on the move in literary scholarship. Long regarded with some suspicion, and retained, if at all, with caution, the idea of metaphysical poetry has been taken up by recent scholars as an invitation to reconsider the affinity between poetry and metaphysics in seventeenth-century writing. Work by Gordon Teskey, Wendy Beth Hyman, James Kuzner, and others, has shown how lyrics like Shakespeare’s might be metaphysical, not by rehearsing metaphysical arguments, or reciting their terms of art, but by pursuing a kind of thinking in excess of philosophy. 6 ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ itself should dispel any lingering assumptions that a poem’s philosophical content must be extracted and formalized before it can count as truly philosophical. Such a position would accept that whatever knowledge poetry offered must be revoiced in the language of reason; whereas, as we will see, it is Reason that must borrow poetry’s voice for its ‘ Threne ’. Meanwhile, elsewhere in early modern scholarship, metaphysics has been reconceived as a much broader enterprise than previously thought, encompassing a greater variety of writers, forms, and styles. 7 Yet the problem of its definition—of what counts as metaphysics—has only grown starker as a result. In a sense, the history of metaphysics is the history of its attempts to define itself. 8 As the pursuit of the most extreme or original principles of knowledge, it is continually running up against the challenge that these are things it cannot, or should not, know. From the outset, its claims to primacy are hedged by doubts, not only over whether it has the right to make those claims—the first of the puzzles ( aporiai ) Aristotle poses in his Metaphysics , whether there can be a single science of first causes—but over what is lost from view when it does. 9 In reading ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ as a metaphysical poem, then, this essay does not look to establish a substantive metaphysics beneath it, nor to splice metaphysics and poetry together without distinction or division. Instead, it looks to this poem to uncover the catachrestic energy latent within the category of ‘metaphysical poetry’—a category that might best be thought of as an instance of its own best-known operation, by which, in Samuel Johnson’s words, ‘[t]he most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together’. 10 Recognizing the tension coiled within this critical term, the resistance revealed and released by such synthetic force, might thus shed new light on poetry, and on metaphysics too.

In Shakespeare’s case, this turns on the question of what, if anything, can be known about the strange union between a phoenix and a turtle-dove. Like Marston, Shakespeare is grappling with what to call the compound at his poem’s heart, and what it might mean for its beholders and survivors. To do this, the poem tests out various strategies of poetic apprehension, trying first allegory, then metaphysics, before admitting defeat. From that defeat emerges a fresh sense of the matter on which this poem sets to work, and the matter of the poem itself; and with that, the poem reaches the juncture between metaphysics and poetry, where the failure of even the subtlest concepts gives onto the puzzlement of aesthetic experience. The following three parts of this essay thus follow the three moments in Shakespeare’s poem, passing through allegory to metaphysics into aesthetics. As the contours of an early modern aesthetics become sharper, thanks to Rachel Eisendrath and others, so it becomes more plausible to read Shakespeare’s poem as an enquiry into the problem on which metaphysics and aesthetics converge: the dialectic of the universal and particular. 11 Of all the puzzles treated in the Metaphysics , Aristotle judged, this was ‘the hardest of all, and most necessary to theorize’ ( Met , 999a24–5). The waning force of Aristotle’s hylomorphic explanation throughout the seventeenth century, under the pressure of corpuscularian thought, brought the problem’s difficulties into sharper focus. 12 Yet although it falls within the sphere of metaphysics, the disturbances it causes are most keenly felt in aesthetic experience. For the philosophy of aesthetics from Kant onwards, finding something beautiful means encountering a particular that will not be subsumed under a universal concept, but will not renounce its right to some sort of universality. As an obstacle to the reconciliation of particulars and universals, beauty is a scandal for reason, not only because it resists the knowing of the universal, but because it refuses to accept the contrary status of sheer material irrationality. Instead, it holds onto the prospect that the particular, sensuous and fragile, might hold a claim to truth—and that, by stopping its ears to that claim, reason makes itself irrational. This does not mean advocating particular against universal, object against concept. It means, instead, attempting to retrieve a new and better universal, one that is able to reflect on reason’s unacknowledged investments.

Something like this drama unfolds over the course of ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’. Grappling with the love and death of the phoenix and turtle drives the poem to try out new-found capacities of scholastic thinking, only to end up exposing the need that thinking serves. At its centre is a critique of reason as Reason, suddenly rendered visible as an all-too-particular personification, and forced to voice its own shortcomings. Reason is thus returned to the world it seemingly rises above, as a material force in the regime of property and property’s rationalization. Yet if the union of the phoenix and turtle provokes this critique, it does not succeed it with a regime of its own. The truth of love is visible on departure; far from championing its cause, the poem marks its passing. ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ ends in an elegy for the lovers who only in hindsight outstrip rationalization—an elegy that is, moreover, itself an attempt to rationalize. After all, the fact that its closing ‘ Threnos ’ is spoken by Reason itself, ‘As Chorus to their Tragique Scene’ (l.52), reveals the extent, both to which reason has been unsettled, and to which poetry remains invested in reason. 13 In this sense, Shakespeare’s poem cannot escape the critique of metaphysics it ventures. Both metaphysics and poetry are ways of thinking whose vaunted powers are stalked by suspicions of redundancy. Both prove incapable of doing justice to the lovers they remember. And both are reduced, at last, to mourning: metaphysics, by the confounding of its desire for knowledge; poetry, by the recognition that it cannot deduce some posterity from these vanished lovers, let alone be that posterity itself. In that conjunction, however, both metaphysics and poetry afford a better sense of what they have lost. The shortcomings of the poem’s metaphysical concepts are determinate: they are what allow the departed particulars to be represented without being traduced. Poetry, likewise, makes those particulars mournable. In a poem that leads from the failure of the concept to the tomb of its objects, Shakespeare presses the metaphysical dialectic of particular and universal towards its terminus in the aesthetic. By its ending, metaphysics has passed into the material, while that material is redeemed only in memory, through the impassioned but impotent sighing of a prayer. ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ closes in the affinity between art and mourning, where the condition for poetry’s autonomy is also its loss, and where its right to exist is a right to memorialize that loss, mournfully.

‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ begins with a fiat which may not make anything happen. The opening stanza issues a summons that falls somewhere between demand, concession, and invitation: Let the bird of lowdest lay, On the sole Arabian tree, Herauld sad and trumpet be: To whose sound chaste wings obay. (ll.1–4)

By the sound of it, these lines should be louder than they are. The bird is identified only by the loudness of its lay, so forceful that it becomes not just the herald but the trumpet too. It joins a raucous choir of birds announced over subsequent stanzas, from the ‘shriking harbinger’ of the owl (l.5) to the ‘death-deuining Swan’ and his ‘defunctiue Musicke’ (ll.14–15). Yet Barbara Everett is surely right that the tenor of these opening lines ‘unmakes imperatives, the mood of power’. 14 Their speaker is not the bird itself, after all, but some other voice, the one that brings this poem into being. However loud the bird may be, if and when it sounds, its voice is invoked with an uncanny sense of calm. It is only muffled further by the poem’s form. The four-line structure of its first 13 stanzas often tends to fall into a three-line unit from which the fourth line stands enigmatically apart. That can give those final lines an epigrammatic feel: ‘Keepe the obsequie so strict’ (l.12), ‘But in them it were a wonder’ (l.32), ‘Either was the others mine’ (l.36), ‘Simple were so well compounded’ (l.44). Here, the three-line arc of the stanza’s first phrase, and the expectant colon at its end, seemingly anticipate some of some rationale for this summons. Instead, the fourth line preserves the pointed abstraction of the scene: through the metonymy that dissolves a flock of birds in a flurry of wings, before attaching the peculiar epithet of ‘chaste’; but above all, through the verb. ‘Obay’ (l.4) could be indicative or imperative: these wings might naturally obey the herald’s sound, or they might need some additional encouragement to do so. It may alternatively remain as a kind of conditional: let this bird be the herald, and only then will these wings obey. If it is hard to conceive how chaste wings might obey that sound, it is harder still to conceive how they might obey to it. The little glitch in the stanza’s grammar slackens a transitive obedience into an indistinct and intransitive response, further unmaking its imperative, and in doing so, placing an awkward weight on an especially vulnerable moment in the poem’s metre. The four-beat, seven-syllable pattern opens a pause between the last stress of one line and the first of the next. As a result, each line seems marked by an implicit diminuendo, each time growing quieter and slower before restarting in the following line. Rather than smoothing over that technical vulnerability, Shakespeare seems intent on exacerbating it, by routinely beginning his lines with the most unprepossessing of words. ‘To whose sound’ (l.4); ‘To this troupe’ (l.8); ‘From this Session’ (l.9): these monosyllables carry a prosodic charge they cannot bear, and are somehow thickened as a result. Even before its philosophical meditations on distance and space, then, the poem troubles the question of where it takes place. The prepositions, under the weight of the metre, seem to enfold within them some opaque relations of thought.

Meanwhile, the ebbing urgency of this stanza’s verbs brings a new grammatical shape into view. So wide is the space between ‘Let’ and ‘be’, the two terms of this fiat , that another construction emerges: not the giving of orders, but the positing of a hypothesis: let x be y . The stanza has the ring of a geometrical theorem, defining and constructing terms of interpretation that have not yet been set. 15 This is what makes it hard to know what, if anything, is taking place. Over its opening movement, ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ introduces a catafalque of birds, and matches them with a corresponding set of ritual functions. But the form of that ritual wavers. The ‘Session’ (l.9) announced at the beginning of one stanza morphs, by its end, into an ‘obsequie’ (l.12), until the ‘ Requiem ’ (l.16) reframes it finally as a funeral. Yet unless the invitations of Let are accepted, none of these birds arrives, and none of their functions are performed. If one reading sees a procession of birds acting out a funeral, another would emphasize the birds on the one hand, and the funeral on the other, with only the direction of the poem’s mysterious voice to read them together. That direction is more suggestive than instructive: not x is y , but let x be y . By the time that same grammar returns in the fourth stanza, what is standing for what is harder to say: Let the Priest in Surples white, That defunctiue Musicke can, Be the death-deuining Swan, Lest the Requiem lacke his right. (ll.13–16)

Instead of appointing the swan as priest, the poem posits priest as swan; instead of casting birds in a familiar ritual, a familiar ritual is wrenched out of shape, with only the whiteness of the surplice to establish a correspondence between bird and priest so heterogeneous it is positively surreal. Even the ‘ Requiem ’ momentarily comes alive, not as a ceremony with its rite, but a claimant with his right . Elsewhere in the poem, reversing predications has a similar shock-effect, most startlingly in the Threnos , in a line where the deadness of the birds is promoted, abstracted, and vivified: ‘Death is now the Phoenix nest’ (l.56). For all the interpreting the poem’s nouns have provoked, its verbs are just as strange: whether in the archaism of ‘can’, the aetiolated imperatives like ‘obay’, or simply the kind of hypothetical positing involved in letting one thing be another.

This is the speculative grammar in which the poem’s opening section unfolds. Rather than soldering two terms into identity, it sets them in motion, each defining and destabilizing the other. Shakespeare imports this mode of double speaking from allegory. In his landmark argument for reading ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ as metaphysical poetry, James Bednarz situates it at the transition between two phases of literary production: on the one side, a tradition of allegory, stretching back through Edmund Spenser to medieval writing; on the other, the cool, tricky lyrics of John Donne. ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, Bednarz writes, is ‘an explicitly self-conscious literary work that reconfigures as metaphysical verse the kind of Spenserian allegory Chester employs’. 16 Yet sliding from allegorical to metaphysical poetry along the literary-historical timeline risks foreclosing allegory’s claim to be the most metaphysical poetry of all. If ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ is Shakespeare’s metaphysical poem, it is one he constructed out of allegory’s resources; and appreciating its metaphysics means appreciating the Spenserian elements of his practice. As Bednarz notes, that in turn means attending to the poem that takes up most of Loves Martyr , by which Shakespeare’s experiment with allegory was mediated: ‘Rosalins Complaint’, by the Welsh poet Robert Chester. ‘Rosalins Complaint’ describes itself on the title-page as ‘ Allegorically shadowing the truth of Loue , in the constant Fate of the Phoenix and Turtle ’ ( LM , A2 r ). Spenser’s example looms large throughout: in its inset history of King Arthur, which picks up where Spenser left off in Book II of The Faerie Queene ; but also in the way that episode of British history is enclosed in allegorical shadows. The love and death of the phoenix and turtle-dove is the overarching narrative of Chester’s poem; but around it play a delirious medley of episodes, from an aerial tour of the wonders of the world, to catalogues of flora and fauna, to alphabetical and acrostic celebrations of phoenix and turtle. That eclecticism is perhaps part of allegory’s strategy, a way of signalling the subordination of poetic narrative to some external locus of meaning. 17 In Chester’s hands, though, allegorical polysemy may be just too multiple to form a unified hermeneutic vision. Characters are sporadically identified with abstractions, but seem unable to sustain them. One moment the turtle-dove is constancy, the next, liberal honour. The phoenix may not even be a phoenix at all: ‘O stay me not, I am no Phoenix I’, it insists, ‘And if Ibe that bird, I am defaced’ (C4 v ). Both change meaning as regularly as they change gender. Yet the poem remains insistent that its materials are there to be interpreted.

This paradox is restated insistently in a self-standing poem, ‘To those of light beleefe’, where Chester instructs his poem’s readers: You gentle fauourers of excelling Muses , And gracers of all Learning and Desart, You whose Conceit the deepest worke peruses, Whose Iudgements still are gouerned by Art: Reade gently what you reade, this next conceit Fram’d of pure loue, abandoning deceit. And you whose dull Imagination, And blind conceited Error hath not knowne, Of Herbes and Trees true nomination, But thinke them fabulous that shall be showne: Learne more, search much, and surely you shall find, Plaine honest Truth and Knowledge comes behind. ( LM , C4 r )

Playing on that keyword of allegory, ‘conceit’—perhaps borrowed from Spenser’s letter to Ralegh—Chester praises readers who identify his poem as a ‘conceit | Fram’d of pure loue’, and muster the corresponding ‘Conceit’ while perusing it. By contrast, he censures those whose ‘blind conceited Error’ blocks them from the ‘Plaine honest Truth and Knowledge’ behind the poem’s surface. As the reception of Loves Martyr , and its fervid biographical overinterpretation, have proved, distinguishing between one kind of ‘conceit’ and another is far from self-evident. Rather than signalling Chester’s incompetence, however, this might reveal something about writing allegory after Spenser. Allegory seems to invest a poem with the hope of perfect comprehensibility, through which it might be conceived as true or good and not just as beautiful. Yet the darkness of its conceit suggests this comprehensibility is, if not absent, then certainly hidden. In the absence of some conceptual schema by which the poem’s details could be ordered, but without permission to enjoy those details free from the concept’s demands, allegory is legible only through the piecemeal work of speculation. Only by searching much and learning more can the poem’s readers hope to light on its allegorical moments: the mediations of universal and particular, local and provisional, rather than either’s predominance. 18

If Shakespeare took anything from Chester, it was allegory’s capacity to provoke this kind of thinking. The result, in ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’, is a puzzle: a scene that unfolds according to some cryptic set of norms; a voice that relates those norms, without explaining or performing them; a cast of characters whose significance is uncertain; and a letting-be which holds those characters in a sort of double vision. ‘As a communal ritual of consolation full of shared meanings’, writes Anita Gilman Sherman, ‘the poem seems to instantiate the reverse of a private language and to undo its possibility. Yet, it verges on the unintelligible by offering us the conundrum of a private language on a social scale’. 19 In simultaneously urging collective sense-making and singular incomprehensibility like this, this poem situates itself at the juncture between the universal and particular. That is the site of allegory, and its traffic between its materials and their meaning. But it is also the site of judgement, which from Aristotle onwards had been tasked with relating sensible particulars to intelligible universals. 20 It is this tradition Kant continues, in his third Critique , in defining judgement as ‘the ability to think the particular as contained under the universal’: the rule, the principle, the law. 21 Whether moving from universal to particular, or vice versa, judgement involves a process Kant calls Beurteilung , or ‘estimating’. That process is most energetic in the experience of beauty, where judgement tries and fails to file the stuff of appearance under conceptual headings: lingering over the sensuous particular at hand, without giving up the search for some concept, some universal by which it might be known. In a sense, then, allegory might be seen as an allegory for aesthetic judgement itself. The feverish interpretation required of its readers is a model for the cognitive whirring Kant describes: learning more, searching more, scanning the world in hope of finding recognition. The artwork encourages us to look for its presiding norms, the standards by which we might call it beautiful and know what we mean; yet it escapes subsumption under the universals of understanding (the true) or reason (the good). Although the interpretations it elicits take the form of statements about the work itself, they prove unable to substantiate their claim to cognition, but equally unable to exchange that claim for the comfort of indifferent liking.

The tension between universal and particular ran through aesthetics long before Kant. For Aquinas, Maura Nolan has shown, beauty held a universal scope as a metaphysical transcendental while retaining an irreducibly particular moment in its relation to subjective cognition. 22 That medieval legacy only clarifies the closeness of aesthetics to metaphysics. The dilemma of particular and universal, we have seen, is one they share. Not just a problem, perhaps the problem, on which metaphysics works since Aristotle, it is a problem for metaphysics itself, because it throws into doubt the spectrum of thinking that is its condition of possibility. Aristotle establishes that spectrum at the opening of the Metaphysics , which begins in the love of knowledge: ‘all people by nature desire to know’ ( Met , 980a1). That desire moves upwards from experience ( empeira ) to art ( technē ) to knowledge ( epistēmē ), and from particulars to universals, until, with the first philosophy known afterwards as metaphysics, thinking reaches the first causes of everything that exists. Metaphysical enquiry thus involves an ascent from the particulars, even if Aristotle resists the hypostasis of otherworldly principles he attributes to Plato. It is premised on human cognition as allowing that ascent by progressing through a series of homogeneous moments, from experience to knowledge, whose continuity and hierarchy can make things cohere. Crucially, there is an affinity here with allegory. The fourfold allegorical method developed by Origen and later Christian thinkers, Angus Fletcher has argued, corresponds to an Aristotelian search for the four causes; with this method, readers of allegory follow the path of metaphysics, asking after the essence and meaning of what they read, and stopping only at the universal in which the conceit is illuminated. 23 For Fletcher, as for many theorists of allegory, this spiriting of particulars into universals taints metaphysics and allegory alike with an ideological guilt. Yet what Shakespeare presents in ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ is an alternative possibility latent in allegorical technique. As the following part will argue, the poem shows the recursions of thought from universality as it is driven back to its bodies. But these recursions release an energy that rises above particulars even as it immerses itself in them, to find what, speaking of allegory, Namratha Rao has called ‘a moving concept, one that is both critical and speculative’. 24 The charting of that dialectic, in both its moments, is what makes Shakespeare’s poem metaphysical. Metaphysics’ desire to know may be nothing but wishful thinking, or, worse, the impulse towards domination. But it also makes metaphysics a thinking which can divulge its own innermost wishes.

‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ stages a ‘Session’ that might pass judgement on the phoenix and turtle, and a ‘ Requiem ’ that might set them to rest. But even assuming the ritual can begin—as it seems, in the poem’s second movement, to do—it cannot reconcile the particular and universal dimensions of its central figures. Here the Antheme doth commence, Love and Constancie is dead, Phoenix and the Turtle fled, In a mutuall flame from hence. (ll.21–4)

As this new voice enters, it sounds as though the allegory’s conceit is spoken out loud. ‘Love’ and ‘Constancie’ reveal themselves as the proper essences of phoenix and turtle; with their demise, the concepts they signified and instantiated are dead. Nonetheless, mapping one pair onto another already oversimplifies the internal fusion of love and constancy, for which only a singular verb, ‘is’, is required. Meanwhile, the distinction of the stanza’s internal rhyme is as important as its identification: if love and constancy are ‘dead’, here, in this anthem, the phoenix and turtle may have ‘fled’, still living somewhere ‘hence’. This is the story of the philosophical concepts that characterize the second part of Shakespeare’s poem. Those concepts are brought in to determine what this love between phoenix and turtle might mean; but no sooner do they enter than they are denatured by that love’s resistance to determination. Introduced as the poem’s metaphysical causes, they end up as its materials. So, by the following stanza, ‘Love and Constancie’ has been further reduced, such that now, love alone is the presiding conceit: So they loued as loue in twaine, Had the essence but in one, Two distincts, Diuision none, Number there in loue was slaine. Hearts remote, yet not asunder; Distance and no space was seene, Twixt this Turtle and his Queene; But in them it were a wonder. (ll.25–32)