Advanced search

Saved to my library.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 04 March 2024

- Clarification 05 March 2024

Millions of research papers at risk of disappearing from the Internet

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

More than one-quarter of scholarly articles are not being properly archived and preserved, a study of more than seven million digital publications suggests. The findings, published in the Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication on 24 January 1 , indicate that systems to preserve papers online have failed to keep pace with the growth of research output.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 627 , 256 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00616-5

Updates & Corrections

Clarification 05 March 2024 : The headline of this story has been edited to reflect the fact that some of these papers have not entirely disappeared from the Internet. Rather, many papers are still accessible but have not been properly archived.

Eve, M. P. J. Libr. Sch. Commun. 12 , eP16288 (2024).

Article Google Scholar

Laakso, M., Matthias, L. & Jahn, N. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 72 , 1099–1112 (2021).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

- Information technology

- Scientific community

The dream of electronic newspapers becomes a reality — in 1974

News & Views 07 MAY 24

How scientists are making the most of Reddit

Career Feature 01 APR 24

A global timekeeping problem postponed by global warming

Article 27 MAR 24

US halts funding to controversial virus-hunting group: what researchers think

News 16 MAY 24

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Career Feature 15 MAY 24

Standardized metadata for biological samples could unlock the potential of collections

Correspondence 14 MAY 24

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

Mount Etna’s spectacular smoke rings and more — April’s best science images

News 03 MAY 24

Research Associate - Metabolism

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoc Fellowships

Train with world-renowned cancer researchers at NIH? Consider joining the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) at the National Cancer Institute

Bethesda, Maryland

NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Faculty Recruitment, Westlake University School of Medicine

Faculty positions are open at four distinct ranks: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Full Professor, and Chair Professor.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

PhD/master's Candidate

PhD/master's Candidate Graduate School of Frontier Science Initiative, Kanazawa University is seeking candidates for PhD and master's students i...

Kanazawa University

Senior Research Assistant in Human Immunology (wet lab)

Senior Research Scientist in Human Immunology, high-dimensional (40+) cytometry, ICS and automated robotic platforms.

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston University Atomic Lab

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 13 May 2024

- Research & Ideas

Picture This: Why Online Image Searches Drive Purchases

Smaller sellers' products often get lost on large online marketplaces. However, harnessing images in search can help consumers find these products faster, increasing sales and customer satisfaction, finds research by Chiara Farronato and colleagues.

- 07 Nov 2023

- Cold Call Podcast

How Should Meta Be Governed for the Good of Society?

Julie Owono is executive director of Internet Sans Frontières and a member of the Oversight Board, an outside entity with the authority to make binding decisions on tricky moderation questions for Meta’s companies, including Facebook and Instagram. Harvard Business School visiting professor Jesse Shapiro and Owono break down how the Board governs Meta’s social and political power to ensure that it’s used responsibly, and discuss the Board’s impact, as an alternative to government regulation, in the case, “Independent Governance of Meta’s Social Spaces: The Oversight Board.”

- 29 Aug 2023

As Social Networks Get More Competitive, Which Ones Will Survive?

In early 2023, TikTok reached close to 1 billion users globally, placing it fourth behind the leading social networks: Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram. Meanwhile, competition in the market for videos had intensified. Can all four networks continue to attract audiences and creators? Felix Oberholzer-Gee discusses competition and imitation among social networks in his case “Hey, Insta & YouTube, Are You Watching TikTok?”

- 15 Aug 2023

(Virtual) Reality Check: How Long Before We Live in the 'Metaverse'?

Generative AI has captured the collective imagination for the moment, eclipsing the once-hyped metaverse. However, it's not the end of virtual reality. A case study by Andy Wu and David Yoffie lays out the key challenges immersive 3D technology must overcome to be truly transformative.

- 15 Nov 2022

Why TikTok Is Beating YouTube for Eyeball Time (It’s Not Just the Dance Videos)

Quirky amateur video clips might draw people to TikTok, but its algorithm keeps them watching. John Deighton and Leora Kornfeld explore the factors that helped propel TikTok ahead of established social platforms, and where it might go next.

- 22 Aug 2022

Can Amazon Remake Health Care?

Amazon has disrupted everything from grocery shopping to cloud computing, but can it transform health care with its One Medical acquisition? Amitabh Chandra discusses company's track record in health care and the challenges it might face.

- 06 Jan 2021

- Working Paper Summaries

Aggregate Advertising Expenditure in the US Economy: What's Up? Is It Real?

We analyze total United States advertising spending from 1960 to 2018. In nominal terms, the elasticity of annual advertising outlays with respect to gross domestic product appears to have increased substantially beginning in the late 1990s, roughly coinciding with the dramatic growth of internet-based advertising.

- 21 Jan 2020

The Impact of the General Data Protection Regulation on Internet Interconnection

While many countries consider implementing their own versions of privacy and data protection regulations, there are concerns about whether such regulations may negatively impact the growth of the internet and reduce technology firms’ incentives in operating and innovating. Results of this study suggest limited effects of such regulations on the internet layer.

- 18 Jul 2019

- Lessons from the Classroom

The Internet of Things Needs a Business Model. Here It Is

Companies have struggled to find the right opportunities for selling the Internet of Things. Rajiv Lal says that’s all about to change. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 04 Mar 2019

- What Do You Think?

What’s the Antidote to Surveillance Capitalism?

SUMMING UP: As companies increasingly build business models around our personal data, what can be done to fight back? James Heskett's readers suggest there are no easy answers. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 30 May 2018

Should Retailers Match Their Own Prices Online and in Stores?

For multichannel retailers, pricing strategy can be difficult to execute and confusing to shoppers. Research by Elie Ofek and colleagues offers alternative approaches to getting the price right. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 24 May 2018

Distance Still Matters in Business, Despite the Internet

The internet makes distance less a problem for conducting business, but geography still matters in the digital age. Shane Greenstein explains why. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 12 Mar 2018

Using Online Prices for Measuring Real Consumption Across Countries

The increasing availability of big data can improve measurement of real consumption in closer to real time. This study shows that online prices may enhance data of the International Comparisons Program, dramatically improving the frequency and transparency of purchasing power parities compared with traditional data collection methods.

- 02 Mar 2018

Evidence of Decreasing Internet Entropy: The Lack of Redundancy in DNS Resolution by Major Websites and Services

Stabilizing the domain name resolution (DNS) infrastructure is critical to the operation of the internet. Single points of failure become more consequential as a larger proportion of the internet's biggest sites are managed by a small number of externally hosted DNS providers. Providers could encourage diversification by requiring domain owners to select a secondary DNS provider.

- 16 Nov 2016

Turning One Thousand Customers into One Million

In the second part of a series on growing startups, Thales S. Teixeira explains how Uber, Etsy, and Airbnb climbed from one thousand customers to one million. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 19 Oct 2016

Three Critical Mistakes Digital Businesses Make With Content

Do companies really understand the nature of today's digital transformation? Bharat Anand's book The Content Trap offers a new view of digital strategy that shifts the focus from "produce the best content" to "create the best connections." Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 14 Sep 2016

Web Surfers Have a Schedule and Stick to It

Note to web marketers: Consumers won't carve out more time to visit your site. So how do you attract them? Start by understanding their online habits, reports new research by Shane Greenstein and colleagues. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Aug 2016

The Empirical Economics of Online Attention

This study uses extensive data on user online activity between 2008 and 2013 to examine the links between user allocation of attention and characteristics of user. Findings show remarkable stability in how households allocated their scarce attention over the five years. Results imply that suppliers are competing for a finite supply of user time while generally lacking the ability to use price discounts to attract user attention.

- 15 Aug 2016

Black Swans and Big Trends Can Ruin Anyone's Internet Prediction

Coming off the dot-com bust, Thomas R. Eisenmann was confident enough in his internet vision that he wrote a book about what would happen next. For the most part, he was wrong. He offers lessons learned for navigating the boom-bust cycle. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 04 May 2016

What Does Boaty McBoatface Tell Us About Brand Control on the Internet?

SUMMING UP. Boaty McBoatface may have been shot down as the social-media sourced name of a research vessel, but James Heskett's readers are up to their hip-boots in opinions on the matter. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research

Current Issue

Selected Papers in Internet Research 2023. Research from the Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers

IF NOT, ELSE: STANDARDS, PROTOCOLS, NETWORKS AND HOW THEY MAKE A DIFFERENCE

Reparative media: revolutionary storytelling and its enemies in a streaming era, infrastructures of manipulation, dispatches from the early internet: histories, imaginaries, and archaeologies, web histories in the making: web archives & the logics of practice, ideology and affect in political polarization and fandom online, gender and misinformation: digital hate and harassment (part ii), toward a revolution in australian children’s data and privacy, revisiting key concepts in digital media research: influence, populism, partisanship, polarisation, digital technologies and revolution in africa: complexities, ambivalences, and contextual realities, digital infrastructures and environmental justice: policies, practices, and visions, after deplatforming: retracing content moderation effects across platforms and a post-american web, digital memory, pandemic temporalities: reflections on studying and storing crisis media, exploring the contextual complexities of violence on digital platforms: intersections, impacts, and solutions, wartok: networked soundscapes of memetic warfare, stitching politics and identity on tiktok, misogyny, survivorship, and believability on digital platforms: emerging techniques of abuse, radicalization, and resistance, researching under platforms’ gaze: rethinking the challenges of platform governance research, gaming platforms as chaotic neutral: toxic performance, community resistance, and agonistic potential, exploring facebook’s “why am i seeing this ad” feature: meaningful transparency or further obfuscation, proactive memefication and political catharsis: how online humor prompts political expression among sudanese social media users, the high-tech elite assessing value priorities of techies using the european social survey 2012-2020, data representation as epistemological resistance, the insurrectionist playbook: jair bolsonaro and the national congress of brazil, trending resistance: a study of the tiktok #deinfluencing phenomenon., groups are easy, federating is hard, views of the world and looking into the future of news: researching youth, news, and citizenship in portugal, hack your age: older adults as provocative and speculative iot co-designers, algorithms, aesthetics and the changing nature of cultural consumption online, exploring parents’ knowledge of dark design and its impact on children’s digital well-being, antecedents of privacy protection behaviors at the vertical and horizontal levels, everyday hate on facebook: visual misogyny and the anti-feminist movement in india, a river of data runs through it: examining urban circulations in the digital age, theorizing environmental mediation through ireland's peatlands, vicarious nostalgia playing retrogames fosters an appreciation for gaming history, practices and participation of marginalised youth in non-formal and digitalised educational arrangements, pushing back: digital resistance as a sensitizing concept, magic in the air: memes, magic, and the internet, _even more_ complicated: the networked lives of teenagers in a context of exclusion in brazil, fever dreams and the future of nostalgia on tiktok, “are we dating the same guy”: collective sensemaking as a moral responsibility in facebook groups, the infrastructural power of programmatic advertising networks: analyzing disinformation industries in brazil, stable science and fickle bodies: an examination of trust and the construction of expertise on r/skincareaddiction, “this tweet is unavailable”: #blacklivesmatter tweets decay, #vladdydaddy on tiktok: imagined intimacy and memetic participation in times of war, using “small data” to map how men’s rights came online (work-in-progress), dear baby gays: investigating the sociotechnical practices of older lgbtq+ tiktok users, conspirituality capitalism: yoga, authenticity, and whiteness on a streaming video platform, these girls (strip) for the clout: exploring aspirational, emotional and erotic labor of black women hip-hop artists on onlyfans, revolutionary discourses in a time capsule: a historiographical analysis of canonical, intellectual literature concerning the social impact and significance of the internet., invitation to listen: mapping clubhouse’s early invite-only social capital network, is it (micro)cheating how social media confound assumptions in romantic relationships, the hashtag syllabus as class assignment: from critical information literacy to cultural critique, platform power, xr, and the metaverse: new challenges or old structures, the intimacy triple bind: structural inequalities and relational labour in the influencer industry, #stopmenstrualshaming: xiaohongshu users’ online advocacy for women’s issues in china, alternative visions for the dns: core, iahc, and the possibility for expanded gtlds in early governance policy, discussing health without adults – youth voices in peer-led discussions on teenagers’ subreddits, an intimate revolution: digital practices of intimacy during covid-19 and beyond, exploring the current landscape of trans technology design, equality through exclusion towards a new conceptualization of democratic exclusion in the context of digital public venues, dark patterns and pedagogy: expanding scholarship and curriculum on manipulative marketing practices, lifestyle governmentality in china: governing the entrepreneurial citizen subjects through lifestyle practices on xiaohongshu (red), assessing the impact of global attention on subreddit community practices: the case of /r/hongkong, epistemologies of missing data: covid data builders and the production and maintenance of marginalized covid datasets, collective sensemaking and intersemiotic dissonance: a study of crisis discourse on tiktok, “would you date a maid”, exploring how u.s. k-12 education addresses privacy literacy, real but fake, real because fake: technologically augmented k-pop idols and meta-authenticity, the world according to tiktok: an observatory on cross-national content prioritization and platform-mediated proximities, digital labor and rentier platform capitalism: reform or revolution, revolutionary tactics: abolish privacy, unfree; indentured; influencer, artificial love: revolutions in how ai and ar embodied romantic chatbots can move through relationship stages, women revolutionising money: investigating meaning-making and gender messaging in female-to-female finfluencing on instagram, care-less data pop cultures: an investigation of the data imaginaries and data cultures of the pandemic, “getting paid to take care for the ones you love”: social media influencing as a means for paid social reproduction labor, climate anxiety as a lens into young people's political expression on youtube, commemorating as criticizing: how li wenliang’s weibo homepage becomes a place for questioning china’s covid-19 policies and a “wailing wall”, manufacturing influencers: the revolutionary roles of mcns (multi-channel networks) in the platform economy, identifying with privacy: references to privacy in developers’ github profiles, algorithmic folk theories of online harassment: how social media algorithms enable online harassment and prevent intervention, ‘not like other social networks’ bereal and the remediation of liveness in the platform environment, behold the metaverse: facebook’s meta revolution and the circulation of elite discourse, civic participation in china: a comparative study between wechat and douyin as a democratic arena, mental health and the digital care assemblage: moderation practices & user experiences, technological practices of refusal: radical reimagination in m eifler’s computational prosthetics, feminist queen or conspiracy theorist female spreaders of women's health disinformation, techno-political promises of pandemic management: a situation of apps and excel in public health, the algorithmic moderation of sexual expression: pornhub, payment processors and csam, cruising tiktok: using algorithmic folk knowledge to evade cisheteronormative content moderation, #averageyetconfidentmen: chinese stand-up comedy and feminist discourse on douyin, internet governance and moral entrepreneurs, vernacular pedagogies for the synthetic media age, constructing and marketing sexual fantasy: analyzing the social media of sex robots, care, inc.: how big tech responded to the end of roe, the politics and evolution of tiktok as platform tool, 'if we look at it from an lgbt point of view…’ mobilizing lgbtq+ stakeholders to queer algorithmic imaginaries, "i worked so hard, and i still didn't succeed”: coding bootcamp experiences of people with disabilities, beliefs, values and emotions in practitioners’ engagements with learning analytics in higher education, where in society will ai agents fit a proposed framework for understanding attitudes toward ai occupational roles from theoretical perspectives of status, identity, and ontology, perils of place: geofences and predatory platform intimacies, platforms, power & advertising: analysing relations of dependency in the digital advertising ecosystem, everyday misogyny: discourses about depp v heard on twitter, defending human rights in the era of datafication, with or without the crowd the influence of coder characteristics on coding decisions comparing crowdworkers and traditional coders., unraveling disinformation: examining the human infrastructure of misinformation in brazil through the lens of heteromation, dimensions of data quality for values in smart cities datafication practices, dark design patterns and gamification as the heart of dating applications’ business models, rethinking the social in social media, who watches the birdwatchers creating a rogue archive of twitter’s ongoing collapse, algospeak and algo-design in platformed book publishing: revolutionary creative tactics in digital paratext to circumvent content moderation, tracing media solidarities with muslims: contesting islamophobia on twitter, demographic, occupational and professional predictors of tweet deletion among u.s. journalists, mapping tumblr through fannish homophilies, the impact of tiktok policies on information flows during times of war: evidence of ‘splinternet’ and ‘shadow-promotion’ in russia, the politics of platform imaginaries, exploring authenticity on the social media app bereal, “here to have fun and fight ableism”: #autisktok user bios as neuroqueer micro-activist platform affordances, theorizing and analyzing the contingent casino, social media governance via an “anemic” policy regime how boundary spanning, competing issue definitions, lack of cohesion, and administrative fragmentation impede regulatory reform, "youtube doesn't care about creators": how youtubers use the platform to promote accountability, hook-up apps complicate visibility for rural queer people: results of a qualitative scoping study in the united kingdom, the great reset: “counterpower” in the context of media concentration and platform dependence, the value affordances of social media engagement features, evolving spatialities of digital life: troubling the boundaries of the smart city/home divides, get with the program: programmatic advertising and the datafication of podcast audiences, the convenience store revolution: computer networks, logistics, and the reinvention of retail in japan, deplatforming the smart city: giving residents control over their personal data, communicating care - healing, therapy and influencer practices on social media, platform pr – the public moderation of platform values through tiktok for good, digital labor under the state/capitalist duopoly: state labor and playful workaholics in chinese digital space, the emergent r/antiwork revolution and managerial allies, strategic (in)visibility: how marginalised creators navigate the risks and constraints of online visibility, potholes and power: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of ‘look at this f*ckin’ street’ on instagram, bleeding purple, seeing pink: domestic visibility, gender & social reproduction in the home studios of twitch.tv, infrastructural insecurity: geopolitics in the standardization of telecommunications networks, reproductive health apps and empowerment – a contradiction, testing the role of categorical and resource inequalities in indirect internet uses of older adults: a path analysis, exploring the dark side of cryptocurrencies on facebook and telegram: uncovering media manipulation and “get-rich-quick” deceptive schemes, toxicity against brazilian women deputies on twitter: a categorization of discursive violence, *exploring nigeria`s endsars movement through the nexus of memory*, big ai: the cloud as marketplace and infrastructure, the weird governance of fact-checking: from watchdogs to content moderators, one hundred nazi screens: interfaces and the structure of u.s. white nationalist digital networks on telegram, super-appification: conglomeration in the mobile ecosystem, mineral exploration in indigenous lands: the discursive normalization of illegal mining in brazil, designing ethical artificial intelligence (ai) systems with meaningful youth participation: implications and considerations, perceived entitlement and obligation between tiktok creators and audiences, the imperial haiku commission approves this message’: an examination of automated play and culture as (re)designed by bots. , towards anticaste internet: the operation, challenges and aspirations of bahujan publishers., weizenbaum's performance and theory modes: lessons for critical engagement with large language model chatbots, why do arab-palestinian journalists delete tweets, data refusal from below: a framework for understanding, evaluating, and envisioning refusal strategies, revealing coordinated image-sharing in social media: a case study of pro-russian influence campaigns, memes, multimodalities, and machines: assembling multimodal patterns in meme classification study.

- Español (España)

Developed By

ISSN: 2162-3317

From Science to Arts, an Inevitable Decision?

The wonderful world of fungi, openmind books, scientific anniversaries, simultaneous translation technology – ever closer to reality, featured author, latest book, the impact of the internet on society: a global perspective, introduction.

The Internet is the decisive technology of the Information Age, as the electrical engine was the vector of technological transformation of the Industrial Age. This global network of computer networks, largely based nowadays on platforms of wireless communication, provides ubiquitous capacity of multimodal, interactive communication in chosen time, transcending space. The Internet is not really a new technology: its ancestor, the Arpanet, was first deployed in 1969 (Abbate 1999). But it was in the 1990s when it was privatized and released from the control of the U.S. Department of Commerce that it diffused around the world at extraordinary speed: in 1996 the first survey of Internet users counted about 40 million; in 2013 they are over 2.5 billion, with China accounting for the largest number of Internet users. Furthermore, for some time the spread of the Internet was limited by the difficulty to lay out land-based telecommunications infrastructure in the emerging countries. This has changed with the explosion of wireless communication in the early twenty-first century. Indeed, in 1991, there were about 16 million subscribers of wireless devices in the world, in 2013 they are close to 7 billion (in a planet of 7.7 billion human beings). Counting on the family and village uses of mobile phones, and taking into consideration the limited use of these devices among children under five years of age, we can say that humankind is now almost entirely connected, albeit with great levels of inequality in the bandwidth as well as in the efficiency and price of the service.

At the heart of these communication networks the Internet ensures the production, distribution, and use of digitized information in all formats. According to the study published by Martin Hilbert in Science (Hilbert and López 2011), 95 percent of all information existing in the planet is digitized and most of it is accessible on the Internet and other computer networks.

The speed and scope of the transformation of our communication environment by Internet and wireless communication has triggered all kind of utopian and dystopian perceptions around the world.

As in all moments of major technological change, people, companies, and institutions feel the depth of the change, but they are often overwhelmed by it, out of sheer ignorance of its effects.

The media aggravate the distorted perception by dwelling into scary reports on the basis of anecdotal observation and biased commentary. If there is a topic in which social sciences, in their diversity, should contribute to the full understanding of the world in which we live, it is precisely the area that has come to be named in academia as Internet Studies. Because, in fact, academic research knows a great deal on the interaction between Internet and society, on the basis of methodologically rigorous empirical research conducted in a plurality of cultural and institutional contexts. Any process of major technological change generates its own mythology. In part because it comes into practice before scientists can assess its effects and implications, so there is always a gap between social change and its understanding. For instance, media often report that intense use of the Internet increases the risk of alienation, isolation, depression, and withdrawal from society. In fact, available evidence shows that there is either no relationship or a positive cumulative relationship between the Internet use and the intensity of sociability. We observe that, overall, the more sociable people are, the more they use the Internet. And the more they use the Internet, the more they increase their sociability online and offline, their civic engagement, and the intensity of family and friendship relationships, in all cultures—with the exception of a couple of early studies of the Internet in the 1990s, corrected by their authors later (Castells 2001; Castells et al. 2007; Rainie and Wellman 2012; Center for the Digital Future 2012 et al.).

Thus, the purpose of this chapter will be to summarize some of the key research findings on the social effects of the Internet relying on the evidence provided by some of the major institutions specialized in the social study of the Internet. More specifically, I will be using the data from the world at large: the World Internet Survey conducted by the Center for the Digital Future, University of Southern California; the reports of the British Computer Society (BCS), using data from the World Values Survey of the University of Michigan; the Nielsen reports for a variety of countries; and the annual reports from the International Telecommunications Union. For data on the United States, I have used the Pew American Life and Internet Project of the Pew Institute. For the United Kingdom, the Oxford Internet Survey from the Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, as well as the Virtual Society Project from the Economic and Social Science Research Council. For Spain, the Project Internet Catalonia of the Internet Interdisciplinary Institute (IN3) of the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC); the various reports on the information society from Telefónica; and from the Orange Foundation. For Portugal, the Observatório de Sociedade da Informação e do Conhecimento (OSIC) in Lisbon. I would like to emphasize that most of the data in these reports converge toward similar trends. Thus I have selected for my analysis the findings that complement and reinforce each other, offering a consistent picture of the human experience on the Internet in spite of the human diversity.

Given the aim of this publication to reach a broad audience, I will not present in this text the data supporting the analysis presented here. Instead, I am referring the interested reader to the web sources of the research organizations mentioned above, as well as to selected bibliographic references discussing the empirical foundation of the social trends reported here.

Technologies of Freedom, the Network Society, and the Culture of Autonomy

In order to fully understand the effects of the Internet on society, we should remember that technology is material culture. It is produced in a social process in a given institutional environment on the basis of the ideas, values, interests, and knowledge of their producers, both their early producers and their subsequent producers. In this process we must include the users of the technology, who appropriate and adapt the technology rather than adopting it, and by so doing they modify it and produce it in an endless process of interaction between technological production and social use. So, to assess the relevance of Internet in society we must recall the specific characteristics of Internet as a technology. Then we must place it in the context of the transformation of the overall social structure, as well as in relationship to the culture characteristic of this social structure. Indeed, we live in a new social structure, the global network society, characterized by the rise of a new culture, the culture of autonomy.

Internet is a technology of freedom, in the terms coined by Ithiel de Sola Pool in 1973, coming from a libertarian culture, paradoxically financed by the Pentagon for the benefit of scientists, engineers, and their students, with no direct military application in mind (Castells 2001). The expansion of the Internet from the mid-1990s onward resulted from the combination of three main factors:

- The technological discovery of the World Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee and his willingness to distribute the source code to improve it by the open-source contribution of a global community of users, in continuity with the openness of the TCP/IP Internet protocols. The web keeps running under the same principle of open source. And two-thirds of web servers are operated by Apache, an open-source server program.

- Institutional change in the management of the Internet, keeping it under the loose management of the global Internet community, privatizing it, and allowing both commercial uses and cooperative uses.

- Major changes in social structure, culture, and social behavior: networking as a prevalent organizational form; individuation as the main orientation of social behavior; and the culture of autonomy as the culture of the network society.

I will elaborate on these major trends.

Our society is a network society; that is, a society constructed around personal and organizational networks powered by digital networks and communicated by the Internet. And because networks are global and know no boundaries, the network society is a global network society. This historically specific social structure resulted from the interaction between the emerging technological paradigm based on the digital revolution and some major sociocultural changes. A primary dimension of these changes is what has been labeled the rise of the Me-centered society, or, in sociological terms, the process of individuation, the decline of community understood in terms of space, work, family, and ascription in general. This is not the end of community, and not the end of place-based interaction, but there is a shift toward the reconstruction of social relationships, including strong cultural and personal ties that could be considered a form of community, on the basis of individual interests, values, and projects.

The process of individuation is not just a matter of cultural evolution, it is materially produced by the new forms of organizing economic activities, and social and political life, as I analyzed in my trilogy on the Information Age (Castells 1996–2003). It is based on the transformation of space (metropolitan life), work and economic activity (rise of the networked enterprise and networked work processes), culture and communication (shift from mass communication based on mass media to mass self-communication based on the Internet); on the crisis of the patriarchal family, with increasing autonomy of its individual members; the substitution of media politics for mass party politics; and globalization as the selective networking of places and processes throughout the planet.

But individuation does not mean isolation, or even less the end of community. Sociability is reconstructed as networked individualism and community through a quest for like-minded individuals in a process that combines online interaction with offline interaction, cyberspace and the local space. Individuation is the key process in constituting subjects (individual or collective), networking is the organizational form constructed by these subjects; this is the network society, and the form of sociability is what Rainie and Wellman (2012) conceptualized as networked individualism. Network technologies are of course the medium for this new social structure and this new culture (Papacharissi 2010).

As stated above, academic research has established that the Internet does not isolate people, nor does it reduce their sociability; it actually increases sociability, as shown by myself in my studies in Catalonia (Castells 2007), Rainie and Wellman in the United States (2012), Cardoso in Portugal (2010), and the World Internet Survey for the world at large (Center for the Digital Future 2012 et al.). Furthermore, a major study by Michael Willmott for the British Computer Society (Trajectory Partnership 2010) has shown a positive correlation, for individuals and for countries, between the frequency and intensity of the use of the Internet and the psychological indicators of personal happiness. He used global data for 35,000 people obtained from the World Wide Survey of the University of Michigan from 2005 to 2007. Controlling for other factors, the study showed that Internet use empowers people by increasing their feelings of security, personal freedom, and influence, all feelings that have a positive effect on happiness and personal well-being. The effect is particularly positive for people with lower income and who are less qualified, for people in the developing world, and for women. Age does not affect the positive relationship; it is significant for all ages. Why women? Because they are at the center of the network of their families, Internet helps them to organize their lives. Also, it helps them to overcome their isolation, particularly in patriarchal societies. The Internet also contributes to the rise of the culture of autonomy.

The key for the process of individuation is the construction of autonomy by social actors, who become subjects in the process. They do so by defining their specific projects in interaction with, but not submission to, the institutions of society. This is the case for a minority of individuals, but because of their capacity to lead and mobilize they introduce a new culture in every domain of social life: in work (entrepreneurship), in the media (the active audience), in the Internet (the creative user), in the market (the informed and proactive consumer), in education (students as informed critical thinkers, making possible the new frontier of e-learning and m-learning pedagogy), in health (the patient-centered health management system) in e-government (the informed, participatory citizen), in social movements (cultural change from the grassroots, as in feminism or environmentalism), and in politics (the independent-minded citizen able to participate in self-generated political networks).

There is increasing evidence of the direct relationship between the Internet and the rise of social autonomy. From 2002 to 2007 I directed in Catalonia one of the largest studies ever conducted in Europe on the Internet and society, based on 55,000 interviews, one-third of them face to face (IN3 2002–07). As part of this study, my collaborators and I compared the behavior of Internet users to non-Internet users in a sample of 3,000 people, representative of the population of Catalonia. Because in 2003 only about 40 percent of people were Internet users we could really compare the differences in social behavior for users and non-users, something that nowadays would be more difficult given the 79 percent penetration rate of the Internet in Catalonia. Although the data are relatively old, the findings are not, as more recent studies in other countries (particularly in Portugal) appear to confirm the observed trends. We constructed scales of autonomy in different dimensions. Only between 10 and 20 percent of the population, depending on dimensions, were in the high level of autonomy. But we focused on this active segment of the population to explore the role of the Internet in the construction of autonomy. Using factor analysis we identified six major types of autonomy based on projects of individuals according to their practices:

a) professional development b) communicative autonomy c) entrepreneurship d) autonomy of the body e) sociopolitical participation f) personal, individual autonomy

These six types of autonomous practices were statistically independent among themselves. But each one of them correlated positively with Internet use in statistically significant terms, in a self-reinforcing loop (time sequence): the more one person was autonomous, the more she/he used the web, and the more she/he used the web, the more autonomous she/he became (Castells et al. 2007). This is a major empirical finding. Because if the dominant cultural trend in our society is the search for autonomy, and if the Internet powers this search, then we are moving toward a society of assertive individuals and cultural freedom, regardless of the barriers of rigid social organizations inherited from the Industrial Age. From this Internet-based culture of autonomy have emerged a new kind of sociability, networked sociability, and a new kind of sociopolitical practice, networked social movements and networked democracy. I will now turn to the analysis of these two fundamental trends at the source of current processes of social change worldwide.

The Rise of Social Network Sites on the Internet

Since 2002 (creation of Friendster, prior to Facebook) a new socio-technical revolution has taken place on the Internet: the rise of social network sites where now all human activities are present, from personal interaction to business, to work, to culture, to communication, to social movements, and to politics.

Social Network Sites are web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system.

(Boyd and Ellison 2007, 2)

Social networking uses, in time globally spent, surpassed e-mail in November 2007. It surpassed e-mail in number of users in July 2009. In terms of users it reached 1 billion by September 2010, with Facebook accounting for about half of it. In 2013 it has almost doubled, particularly because of increasing use in China, India, and Latin America. There is indeed a great diversity of social networking sites (SNS) by countries and cultures. Facebook, started for Harvard-only members in 2004, is present in most of the world, but QQ, Cyworld, and Baidu dominate in China; Orkut in Brazil; Mixi in Japan; etc. In terms of demographics, age is the main differential factor in the use of SNS, with a drop of frequency of use after 50 years of age, and particularly 65. But this is not just a teenager’s activity. The main Facebook U.S. category is in the age group 35–44, whose frequency of use of the site is higher than for younger people. Nearly 60 percent of adults in the U.S. have at least one SNS profile, 30 percent two, and 15 percent three or more. Females are as present as males, except when in a society there is a general gender gap. We observe no differences in education and class, but there is some class specialization of SNS, such as Myspace being lower than FB; LinkedIn is for professionals.

Thus, the most important activity on the Internet at this point in time goes through social networking, and SNS have become the chosen platforms for all kind of activities, not just personal friendships or chatting, but for marketing, e-commerce, education, cultural creativity, media and entertainment distribution, health applications, and sociopolitical activism. This is a significant trend for society at large. Let me explore the meaning of this trend on the basis of the still scant evidence.

Social networking sites are constructed by users themselves building on specific criteria of grouping. There is entrepreneurship in the process of creating sites, then people choose according to their interests and projects. Networks are tailored by people themselves with different levels of profiling and privacy. The key to success is not anonymity, but on the contrary, self-presentation of a real person connecting to real people (in some cases people are excluded from the SNS when they fake their identity). So, it is a self-constructed society by networking connecting to other networks. But this is not a virtual society. There is a close connection between virtual networks and networks in life at large. This is a hybrid world, a real world, not a virtual world or a segregated world.

People build networks to be with others, and to be with others they want to be with on the basis of criteria that include those people who they already know (a selected sub-segment). Most users go on the site every day. It is permanent connectivity. If we needed an answer to what happened to sociability in the Internet world, here it is:

There is a dramatic increase in sociability, but a different kind of sociability, facilitated and dynamized by permanent connectivity and social networking on the web.

Based on the time when Facebook was still releasing data (this time is now gone) we know that in 2009 users spent 500 billion minutes per month. This is not just about friendship or interpersonal communication. People do things together, share, act, exactly as in society, although the personal dimension is always there. Thus, in the U.S. 38 percent of adults share content, 21 percent remix, 14 percent blog, and this is growing exponentially, with development of technology, software, and SNS entrepreneurial initiatives. On Facebook, in 2009 the average user was connected to 60 pages, groups, and events, people interacted per month to 160 million objects (pages, groups, events), the average user created 70 pieces of content per month, and there were 25 billion pieces of content shared per month (web links, news stories, blogs posts, notes, photos). SNS are living spaces connecting all dimensions of people’s experience. This transforms culture because people share experience with a low emotional cost, while saving energy and effort. They transcend time and space, yet they produce content, set up links, and connect practices. It is a constantly networked world in every dimension of human experience. They co-evolve in permanent, multiple interaction. But they choose the terms of their co-evolution.

Thus, people live their physical lives but increasingly connect on multiple dimensions in SNS.

Paradoxically, the virtual life is more social than the physical life, now individualized by the organization of work and urban living.

But people do not live a virtual reality, indeed it is a real virtuality, since social practices, sharing, mixing, and living in society is facilitated in the virtuality, in what I called time ago the “space of flows” (Castells 1996).

Because people are increasingly at ease in the multi-textuality and multidimensionality of the web, marketers, work organizations, service agencies, government, and civil society are migrating massively to the Internet, less and less setting up alternative sites, more and more being present in the networks that people construct by themselves and for themselves, with the help of Internet social networking entrepreneurs, some of whom become billionaires in the process, actually selling freedom and the possibility of the autonomous construction of lives. This is the liberating potential of the Internet made material practice by these social networking sites. The largest of these social networking sites are usually bounded social spaces managed by a company. However, if the company tries to impede free communication it may lose many of its users, because the entry barriers in this industry are very low. A couple of technologically savvy youngsters with little capital can set up a site on the Internet and attract escapees from a more restricted Internet space, as happened to AOL and other networking sites of the first generation, and as could happen to Facebook or any other SNS if they are tempted to tinker with the rules of openness (Facebook tried to make users pay and retracted within days). So, SNS are often a business, but they are in the business of selling freedom, free expression, chosen sociability. When they tinker with this promise they risk their hollowing by net citizens migrating with their friends to more friendly virtual lands.

Perhaps the most telling expression of this new freedom is the transformation of sociopolitical practices on the Internet.

Communication Power: Mass-Self Communication and the Transformation of Politics

Power and counterpower, the foundational relationships of society, are constructed in the human mind, through the construction of meaning and the processing of information according to certain sets of values and interests (Castells 2009).

Ideological apparatuses and the mass media have been key tools of mediating communication and asserting power, and still are. But the rise of a new culture, the culture of autonomy, has found in Internet and mobile communication networks a major medium of mass self-communication and self-organization.

The key source for the social production of meaning is the process of socialized communication. I define communication as the process of sharing meaning through the exchange of information. Socialized communication is the one that exists in the public realm, that has the potential of reaching society at large. Therefore, the battle over the human mind is largely played out in the process of socialized communication. And this is particularly so in the network society, the social structure of the Information Age, which is characterized by the pervasiveness of communication networks in a multimodal hypertext.

The ongoing transformation of communication technology in the digital age extends the reach of communication media to all domains of social life in a network that is at the same time global and local, generic and customized, in an ever-changing pattern.

As a result, power relations, that is the relations that constitute the foundation of all societies, as well as the processes challenging institutionalized power relations, are increasingly shaped and decided in the communication field. Meaningful, conscious communication is what makes humans human. Thus, any major transformation in the technology and organization of communication is of utmost relevance for social change. Over the last four decades the advent of the Internet and of wireless communication has shifted the communication process in society at large from mass communication to mass self-communication. This is from a message sent from one to many with little interactivity to a system based on messages from many to many, multimodal, in chosen time, and with interactivity, so that senders are receivers and receivers are senders. And both have access to a multimodal hypertext in the web that constitutes the endlessly changing backbone of communication processes.

The transformation of communication from mass communication to mass self-communication has contributed decisively to alter the process of social change. As power relationships have always been based on the control of communication and information that feed the neural networks constitutive of the human mind, the rise of horizontal networks of communication has created a new landscape of social and political change by the process of disintermediation of the government and corporate controls over communication. This is the power of the network, as social actors build their own networks on the basis of their projects, values, and interests. The outcome of these processes is open ended and dependent on specific contexts. Freedom, in this case freedom of communicate, does not say anything on the uses of freedom in society. This is to be established by scholarly research. But we need to start from this major historical phenomenon: the building of a global communication network based on the Internet, a technology that embodies the culture of freedom that was at its source.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century there have been multiple social movements around the world that have used the Internet as their space of formation and permanent connectivity, among the movements and with society at large. These networked social movements, formed in the social networking sites on the Internet, have mobilized in the urban space and in the institutional space, inducing new forms of social movements that are the main actors of social change in the network society. Networked social movements have been particularly active since 2010, and especially in the Arab revolutions against dictatorships; in Europe and the U.S. as forms of protest against the management of the financial crisis; in Brazil; in Turkey; in Mexico; and in highly diverse institutional contexts and economic conditions. It is precisely the similarity of the movements in extremely different contexts that allows the formulation of the hypothesis that this is the pattern of social movements characteristic of the global network society. In all cases we observe the capacity of these movements for self-organization, without a central leadership, on the basis of a spontaneous emotional movement. In all cases there is a connection between Internet-based communication, mobile networks, and the mass media in different forms, feeding into each other and amplifying the movement locally and globally.

These movements take place in the context of exploitation and oppression, social tensions and social struggles; but struggles that were not able to successfully challenge the state in other instances of revolt are now powered by the tools of mass self-communication. It is not the technology that induces the movements, but without the technology (Internet and wireless communication) social movements would not take the present form of being a challenge to state power. The fact is that technology is material culture (ideas brought into the design) and the Internet materialized the culture of freedom that, as it has been documented, emerged on American campuses in the 1960s. This culture-made technology is at the source of the new wave of social movements that exemplify the depth of the global impact of the Internet in all spheres of social organization, affecting particularly power relationships, the foundation of the institutions of society. (See case studies and an analytical perspective on the interaction between Internet and networked social movements in Castells 2012.)

The Internet, as all technologies, does not produce effects by itself. Yet, it has specific effects in altering the capacity of the communication system to be organized around flows that are interactive, multimodal, asynchronous or synchronous, global or local, and from many to many, from people to people, from people to objects, and from objects to objects, increasingly relying on the semantic web. How these characteristics affect specific systems of social relationships has to be established by research, and this is what I tried to present in this text. What is clear is that without the Internet we would not have seen the large-scale development of networking as the fundamental mechanism of social structuring and social change in every domain of social life. The Internet, the World Wide Web, and a variety of networks increasingly based on wireless platforms constitute the technological infrastructure of the network society, as the electrical grid and the electrical engine were the support system for the form of social organization that we conceptualized as the industrial society. Thus, as a social construction, this technological system is open ended, as the network society is an open-ended form of social organization that conveys the best and the worse in humankind. Yet, the global network society is our society, and the understanding of its logic on the basis of the interaction between culture, organization, and technology in the formation and development of social and technological networks is a key field of research in the twenty-first century.

We can only make progress in our understanding through the cumulative effort of scholarly research. Only then we will be able to cut through the myths surrounding the key technology of our time. A digital communication technology that is already a second skin for young people, yet it continues to feed the fears and the fantasies of those who are still in charge of a society that they barely understand.

These references are in fact sources of more detailed references specific to each one of the topics analyzed in this text.

Abbate, Janet. A Social History of the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.

Boyd, Danah M., and Nicole B. Ellison. “Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13, no. 1 (2007).

Cardoso, Gustavo, Angus Cheong, and Jeffrey Cole (eds). World Wide Internet: Changing Societies, Economies and Cultures. Macau: University of Macau Press, 2009.

Castells, Manuel. The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture. 3 vols. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996–2003.

———. The Internet Galaxy: Reflections on the Internet, Business, and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

———. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

———. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2012.

Castells, Manuel, Imma Tubella, Teresa Sancho, and Meritxell Roca.

La transición a la sociedad red. Barcelona: Ariel, 2007.

Hilbert, Martin, and Priscilla López. “The World’s Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information.” Science 332, no. 6025 (April 1, 2011): pp. 60–65.

Papacharissi, Zizi, ed. The Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Networking Sites. Routledge, 2010.

Rainie. Lee, and Barry Wellman. Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.

Trajectory Partnership (Michael Willmott and Paul Flatters). The Information Dividend: Why IT Makes You “Happier.” Swindon: British Informatics Society Limited, 2010. http://www.bcs.org/upload/pdf/info-dividend-full-report.pdf

Selected Web References. Used as sources for analysis in the chapter

Agência para a Sociedade do Conhecimento. “Observatório de Sociedade da Informação e do Conhecimento (OSIC).” http://www.umic.pt/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=3026&Itemid=167

BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT. “Features, Press and Policy.” http://www.bcs.org/category/7307

Center for the Digital Future. The World Internet Project International Report. 4th ed. Los Angeles: USC Annenberg School, Center for the Digital Future, 2012. http://www.worldinternetproject.net/_files/_Published/_oldis/770_2012wip_report4th_ed.pdf

ESRC (Economic & Social Research Council). “Papers and Reports.” Virtual Society. http://virtualsociety.sbs.ox.ac.uk/reports.htm

Fundación Orange. “Análisis y Prospectiva: Informe eEspaña.” Fundación Orange. http://fundacionorange.es/fundacionorange/analisisprospectiva.html

Fundación Telefónica. “Informes SI.” Fundación Telefónica. http://sociedadinformacion.fundacion.telefonica.com/DYC/SHI/InformesSI/seccion=1190&idioma=es_ES.do

IN3 (Internet Interdisciplinary Institute). UOC. “Project Internet Catalonia (PIC): An Overview.” Internet Interdisciplinary Institute, 2002–07. http://www.uoc.edu/in3/pic/eng/

International Telecommunication Union. “Annual Reports.” http://www.itu.int/osg/spu/sfo/annual_reports/index.html

Nielsen Company. “Reports.” 2013. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/reports/2013.html?tag=Category:Media+ and+Entertainment

Oxford Internet Surveys. “Publications.” http://microsites.oii.ox.ac.uk/oxis/publications

Pew Internet & American Life Project. “Social Networking.” Pew Internet. http://www.pewinternet.org/Topics/Activities-and-Pursuits/Social-Networking.aspx?typeFilter=5

Related publications

- How the Internet Has Changed Everyday Life

- How Is the Internet Changing the Way We Work?

- Hyperhistory, the Emergence of the MASs, and the Design of Infraethics

Download Kindle

Download epub, download pdf, more publications related to this article, more about technology, artificial intelligence, digital world, visionaries, comments on this publication.

Morbi facilisis elit non mi lacinia lacinia. Nunc eleifend aliquet ipsum, nec blandit augue tincidunt nec. Donec scelerisque feugiat lectus nec congue. Quisque tristique tortor vitae turpis euismod, vitae aliquam dolor pretium. Donec luctus posuere ex sit amet scelerisque. Etiam sed neque magna. Mauris non scelerisque lectus. Ut rutrum ex porta, tristique mi vitae, volutpat urna.

Sed in semper tellus, eu efficitur ante. Quisque felis orci, fermentum quis arcu nec, elementum malesuada magna. Nulla vitae finibus ipsum. Aenean vel sapien a magna faucibus tristique ac et ligula. Sed auctor orci metus, vitae egestas libero lacinia quis. Nulla lacus sapien, efficitur mollis nisi tempor, gravida tincidunt sapien. In massa dui, varius vitae iaculis a, dignissim non felis. Ut sagittis pulvinar nisi, at tincidunt metus venenatis a. Ut aliquam scelerisque interdum. Mauris iaculis purus in nulla consequat, sed fermentum sapien condimentum. Aliquam rutrum erat lectus, nec placerat nisl mollis id. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Nam nisl nisi, efficitur et sem in, molestie vulputate libero. Quisque quis mattis lorem. Nunc quis convallis diam, id tincidunt risus. Donec nisl odio, convallis vel porttitor sit amet, lobortis a ante. Cras dapibus porta nulla, at laoreet quam euismod vitae. Fusce sollicitudin massa magna, eu dignissim magna cursus id. Quisque vel nisl tempus, lobortis nisl a, ornare lacus. Donec ac interdum massa. Curabitur id diam luctus, mollis augue vel, interdum risus. Nam vitae tortor erat. Proin quis tincidunt lorem.

The Internet, Politics and the Politics of Internet Debate

Do you want to stay up to date with our new publications.

Receive the OpenMind newsletter with all the latest contents published on our website

OpenMind Books

- The Search for Alternatives to Fossil Fuels

- View all books

About OpenMind

Connect with us.

- Keep up to date with our newsletter

Quote this content

Internet use statistically associated with higher wellbeing, finds new global Oxford study

Links between internet adoption and wellbeing are likely to be positive, despite popular concerns to the contrary, according to a major new international study from researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute, part of the University of Oxford.

The study encompassed more than two million participants psychological wellbeing from 2006-2021 across 168 countries, in relation to internet use and psychological well-being across 33,792 different statistical models and subsets of data, 84.9% of associations between internet connectivity and wellbeing were positive and statistically significant.

The study analysed data from two million individuals aged 15 to 99 in 168 countries, including Latin America, Asia, and Africa and found internet access and use was consistently associated with positive wellbeing.

Assistant Professor Matti Vuorre, Tilburg University and Research Associate, Oxford Internet Institute and Professor Andrew Przybylski, Oxford Internet Institute carried out the study to assess how technology relates to wellbeing in parts of the world that are rarely studied.

Professor Przybylski said: 'Whilst internet technologies and platforms and their potential psychological consequences remain debated, research to date has been inconclusive and of limited geographic and demographic scope. The overwhelming majority of studies have focused on the Global North and younger people thereby ignoring the fact that the penetration of the internet has been, and continues to be, a global phenomenon'.

'We set out to address this gap by analysing how internet access, mobile internet access and active internet use might predict psychological wellbeing on a global level across the life stages. To our knowledge, no other research has directly grappled with these issues and addressed the worldwide scope of the debate.'

The researchers studied eight indicators of well-being: life satisfaction, daily negative and positive experiences, two indices of social well-being, physical wellbeing, community wellbeing and experiences of purpose.

Commenting on the findings, Professor Vuorre said, “We were surprised to find a positive correlation between well-being and internet use across the majority of the thousands of models we used for our analysis.”

Whilst the associations between internet access and use for the average country was very consistently positive, the researchers did find some variation by gender and wellbeing indicators: The researchers found that 4.9% of associations linking internet use and community well-being were negative, with most of those observed among young women aged 15-24yrs.

Whilst not identified by the researchers as a causal relation, the paper notes that this specific finding is consistent with previous reports of increased cyberbullying and more negative associations between social media use and depressive symptoms among young women.

Adds Przybylski, 'Overall we found that average associations were consistent across internet adoption predictors and wellbeing outcomes, with those who had access to or actively used the internet reporting meaningfully greater wellbeing than those who did not'.

'We hope our findings bring some greater context to the screentime debate however further work is still needed in this important area. We urge platform providers to share their detailed data on user behaviour with social scientists working in this field for transparent and independent scientific enquiry, to enable a more comprehensive understanding of internet technologies in our daily lives.'

In the study, the researchers examined data from the Gallup World Poll, from 2,414,294 individuals from 168 countries, from 2006-2021. The poll assessed well-being with face-to-face and phone surveys by local interviewers in the respondents’ native languages. The researchers applied statistical modelling techniques to the data using wellbeing indicators to test the association between internet adoption and wellbeing outcomes.

Watch the American Psychological Association (APA) video highlighting the key findings from the research.

Download the paper ‘ A multiverse analysis of the associations between internet use and well-being ’ published in the journal Technology, Mind and Behaviour, American Psychological Association.

DISCOVER MORE

- Support Oxford's research

- Partner with Oxford on research

- Study at Oxford

- Research jobs at Oxford

You can view all news or browse by category

Internet Research: Volume 32 Issue 7

Table of contents, how to explain ai systems to end users: a systematic literature review and research agenda.

Inscrutable machine learning (ML) models are part of increasingly many information systems. Understanding how these models behave, and what their output is based on, is a…

Exploring the interplay between question-answering systems and communication with instructors in facilitating learning

Question-answering (QA) systems are being increasingly applied in learning contexts. However, the authors’ understanding of the relationship between such tools and traditional QA…

Antecedents and consequences of the perceived usefulness of smoking cessation online health communities

An empirical study investigated the antecedents to perceived usefulness (PU) and its consequences in the context of smoking cessation online health communities (OHCs).

Demographic factors have little effect on aesthetic perceptions of icons: a study of mobile game icons

Customization by segmenting within human–computer interaction is an emerging phenomenon. Appealing graphical elements that cater to user needs are considered progressively…

Knowledge sharing in online smoking cessation communities: a social capital perspective

Although knowledge sharing in online communities has been studied for many years, little is known about the determinants for individuals' knowledge sharing in online health…

Proximal and distal antecedents of problematic information technology use in organizations

Excessive use of work-related information technology (IT) devices can lead to major performance and well-being concerns for organizations. Extant research has provided evidence of…

Investigating the impact of home-sharing on the traditional rental market

The sharing economy has enjoyed rapid growth in recent years, and entered many traditional industries such as accommodation, transportation and lending. Although researchers in…

Ethical framework for IoT deployment in SMEs: individual perspective

This study aims to investigate the ethical issues related to the internet of Things (IoT) deployment in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) from an individual employee's…

Quantifying the effects of online review content structures on hotel review helpfulness

Drawing on attribution theory, the current paper aims to examine the effects of review content structures on online review helpfulness, focusing on three pertinent variables…

Storytelling in online shops: the impacts on explicit and implicit user experience, brand perceptions and behavioral intention

This paper examines in detail how the use of storytelling with parallax technology can influence the user experience (UX) in online shops as well as brand- and behavior-relevant…

To track or not to track: examining perceptions of online tracking for information behavior research

This study investigates perceptions of the use of online tracking, a passive data collection method relying on the automated recording of participant actions on desktop and mobile…

How technostress and self-control of social networking sites affect academic achievement and wellbeing

Social networking sites (SNS) are heavily used by university students for personal and academic purposes. Despite their benefits, using SNS can generate stress for many people…

Fostering consumer engagement with marketer-generated content: the role of content-generating devices and content features

This research explores the impacts of content-generating devices (mobile phones versus personal computers) and content features (social content and achievement content) on…

Territorial or nomadic? Geo-social determinants of location-based IT use: a study in Pokémon GO

Location-based games (LBGs) have afforded novel information technology (IT) developments in how people interact with the physical world. Namely, LBGs have spurred a wave of…

An analysis of fear factors predicting enterprise social media use in an era of communication visibility

The benefits associated with visibility in organizations depend on employees' willingness to engage with technologies that utilize visible communication and make communication…

Design elements in immersive virtual reality: the impact of object presence on health-related outcomes

Immersive virtual reality (IVR) has been frequently proposed as a promising tool for learning. However, researchers have commonly implemented a plethora of design elements in…

Is voice really persuasive? The influence of modality in virtual assistant interactions and two alternative explanations

Virtual assistants are increasingly used for persuasive purposes, employing the different modalities of voice and text (or a combination of the two). In this study, the authors…

Online date, start – end:

Copyright holder:, open access:.

- Dr Christy Cheung

Further Information

- About the journal (opens new window)

- Purchase information (opens new window)

- Editorial team (opens new window)

- Write for this journal (opens new window)

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Internet & Technology

6 facts about Americans and TikTok

62% of U.S. adults under 30 say they use TikTok, compared with 39% of those ages 30 to 49, 24% of those 50 to 64, and 10% of those 65 and older.

Many Americans think generative AI programs should credit the sources they rely on

Americans’ use of chatgpt is ticking up, but few trust its election information, whatsapp and facebook dominate the social media landscape in middle-income nations, sign up for our internet, science, and tech newsletter.

New findings, delivered monthly

A quarter of U.S. teachers say AI tools do more harm than good in K-12 education

High school teachers are more likely than elementary and middle school teachers to hold negative views about AI tools in education.

Teens and Video Games Today

85% of U.S. teens say they play video games. They see both positive and negative sides, from making friends to harassment and sleep loss.

Americans’ Views of Technology Companies

Most Americans are wary of social media’s role in politics and its overall impact on the country, and these concerns are ticking up among Democrats. Still, Republicans stand out on several measures, with a majority believing major technology companies are biased toward liberals.

22% of Americans say they interact with artificial intelligence almost constantly or several times a day. 27% say they do this about once a day or several times a week.

About one-in-five U.S. adults have used ChatGPT to learn something new (17%) or for entertainment (17%).

Across eight countries surveyed in Latin America, Africa and South Asia, a median of 73% of adults say they use WhatsApp and 62% say they use Facebook.

5 facts about Americans and sports

About half of Americans (48%) say they took part in organized, competitive sports in high school or college.

How Teens and Parents Approach Screen Time

Most teens at least sometimes feel happy and peaceful when they don’t have their phone, but 44% say this makes them anxious. Half of parents say they have looked through their teen’s phone.

Germans stand out for their comparatively light use of social media

Internet use is nearly ubiquitous in Germany, but social media use is not. In fact, Germans stand out internationally for their relatively light use of social media.

REFINE YOUR SELECTION

Research teams, signature reports.

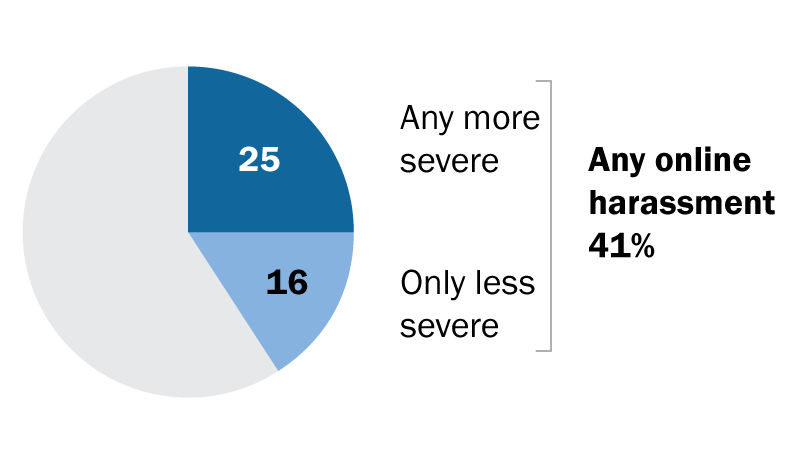

The State of Online Harassment

Roughly four-in-ten Americans have experienced online harassment, with half of this group citing politics as the reason they think they were targeted. Growing shares face more severe online abuse such as sexual harassment or stalking

Parenting Children in the Age of Screens

Two-thirds of parents in the U.S. say parenting is harder today than it was 20 years ago, with many citing technologies – like social media or smartphones – as a reason.

Dating and Relationships in the Digital Age

From distractions to jealousy, how Americans navigate cellphones and social media in their romantic relationships.

Americans and Privacy: Concerned, Confused and Feeling Lack of Control Over Their Personal Information

Majorities of U.S. adults believe their personal data is less secure now, that data collection poses more risks than benefits, and that it is not possible to go through daily life without being tracked.

Americans and ‘Cancel Culture’: Where Some See Calls for Accountability, Others See Censorship, Punishment

Social media fact sheet, digital knowledge quiz, video: how do americans define online harassment.