Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

The Etiology of Dyslexia

The dyslexia paradox and the risks of delayed diagnosis, the role of pediatricians and their professional organizations in dyslexia risk screening, a more proactive approach: screening and advocacy, conclusions, reintroducing dyslexia: early identification and implications for pediatric practice.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Joseph Sanfilippo , Molly Ness , Yaacov Petscher , Leonard Rappaport , Barry Zuckerman , Nadine Gaab; Reintroducing Dyslexia: Early Identification and Implications for Pediatric Practice. Pediatrics July 2020; 146 (1): e20193046. 10.1542/peds.2019-3046

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Dyslexia is a common learning disorder that renders children susceptible to poor health outcomes and many elements of socioeconomic difficulty. It is commonly undiagnosed until a child has repeatedly failed to learn to read in elementary school; this late diagnosis not only places the child at an academic disadvantage but also can be a precursor to psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression. Genetic and neuroimaging research have revealed that dyslexia is heritable and that it is undergirded by brain differences that are present even before reading instruction begins. Cognitive-behavioral research has revealed that there are early literacy skill deficits that represent red flags for dyslexia risk and can be measured at a preschool age. Altogether, this evidence points to dyslexia as a disorder that can be flagged by a pediatrician before school entry, during a period of heightened brain plasticity when interventions are more likely to be effective. In this review, we discuss the clinical implications of the most recent advances in dyslexia research, which converge to indicate that early identification and screening are crucial to the prevention or mitigation of adverse secondary consequences of dyslexia. We further highlight evidence-based and practical strategies for the implementation of early risk identification in pediatric practice so that physicians can be empowered in their ability to treat, educate, and advocate for their patients and families with dyslexia.

The development of reading proficiency in childhood is a public health issue: literacy is a widely recognized determinant of health outcomes and is associated with many indices of academic, social, vocational, and economic success. 1 In a recent National Academy of Medicine summary, the author highlights that duration of education, which is highly dependent on reading proficiency, is a better predictor of health and long life than cigarette smoking or obesity. 2 Children skilled in reading perform better in school, attain higher levels of education, experience lower rates of disease, are less likely to be incarcerated or experience poverty, are more likely to find employment, and achieve higher average incomes as adults compared with children who fail to achieve reading proficiency. 3 For many children with reading impairments, however, the process of learning to read is rife with struggle and frustration, and these children are left susceptible to adverse secondary outcomes, including anxiety and depression. A neurobiologically based specific learning disorder, dyslexia, affects 5% to 10% of children 4 , 5 and is a persistent barrier to reading acquisition.

Dyslexia (or word-level reading difficulty 6 ) is predominantly characterized by a core deficit in phonological processing (the ability to recognize and manipulate speech sounds), which results in impairments in decoding (“sounding out” words), spelling, and word recognition. 7 These impairments almost always lead to difficulties in reading fluency and comprehension, reduced vocabulary, lower content knowledge, 8 and a decline in overall school performance. 9 Dyslexia cannot be explained by poor hearing or vision, low language enrichment, or lack of motivation or opportunity. 10 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition , dyslexia falls under the umbrella of a “specific learning disorder” that “impedes the ability to learn or use specific academic skills (eg, reading, writing, or arithmetic).” 11

Although there are many negative outcomes associated with dyslexia, particularly salient to the pediatrician is the association between dyslexia and poor mental health. 12 , 13 Children with dyslexia are more likely to suffer from generalized anxiety 14 , 15 and also exhibit higher rates of depression. 14 , 16 Because screening for dyslexia is not routinely performed, the direction of causation between dyslexia and comorbid mood disorders in each case is unclear, and this uncertainty can preclude effective early treatment. A mood disorder may be identified in a child with unidentified comorbid dyslexia when it is the dyslexia that is antecedent and causative, obscuring the primary target for intervention.

In addition to mood disorders, speech and language problems are frequently comorbid with dyslexia because both dyslexia and developmental language disorders can be characterized by poor phonological awareness 17 – 19 and other language deficits (eg, oral language comprehension). 20 Approximately one-half of children identified with dyslexia have language disorders, and approximately one-half of children with language disorders have dyslexia. 20 Dyslexia typically results from a core deficit in phonological processing; however, it is important to note that language deficits (eg, low vocabulary or low oral listening comprehension) can also lead to reading problems, especially problems with reading comprehension. Importantly, speech and language problems commonly precede problems in learning to read, so children with speech and language problems should be flagged as being at increased risk for dyslexia. 21

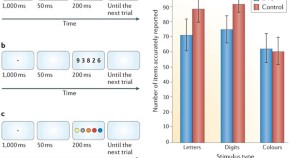

There are many other developmental and psychiatric conditions that are frequently comorbid with dyslexia, further jeopardizing these children’s health and academic outcomes. In total, 20% to 40% of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder have dyslexia, 22 and children with autism spectrum disorder are also at increased risk of having dyslexia. 23 Other behavioral disorders, such as conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder, are also associated with dyslexia. 24 As many as 85% of children with dyspraxia (developmental coordination disorder) have dyslexia, 25 and children with dyscalculia (math learning disorder) 26 and dysgraphia (writing learning disorder) 27 are more likely to have dyslexia than those without. Knowledge of dyslexia within pediatric practice is paramount in considering the most appropriate treatments for these many coexisting disorders.

Despite increasing collaboration among educators, physicians, neuroscientists, speech and language pathologists (SLPs), and psychologists, dyslexia is often overlooked in the field of general pediatrics, perhaps because the diagnostic label of dyslexia is not often used in practice, having been replaced largely by education language of strengths and weaknesses. The clinical implications of a reluctance to use dyslexia as a diagnostic label include children failing to receive an adequate response to early risk signs, appropriate interventions in school, and mental health support.

In this article, we provide an up-to-date overview of dyslexia, specifically addressing common knowledge gaps, neurobiological underpinnings of the disorder, and ways in which pediatricians can play an active role in the early identification of dyslexia risk.

The etiology of dyslexia is multifaceted, including genetic, perceptual and cognitive, neurobiological, and environmental factors. 9 Dyslexia is strongly heritable, occurring in up to 68% of identical twins of individuals with dyslexia and up to 50% of individuals who have a first-degree relative with dyslexia. 19 , 28 – 30 Several genes 31 – 34 have been reported to be candidates for dyslexia susceptibility; it is thought that most of these genes play a role in early brain development. 31 , 34 – 38

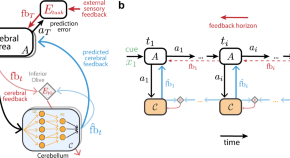

Furthermore, various studies have revealed atypical brain characteristics in individuals with dyslexia compared with their peers. 39 In functional MRI studies, researchers have indicated that reading for typical readers takes place predominantly in left-hemispheric sites of the brain, including the inferior frontal, superior temporal, temporoparietal, and occipitotemporal cortices. 40 As a group, individuals with dyslexia show hypoactivation in the left-hemisphere reading systems. 41 The structural and functional atypicalities in these brain regions include reduced gray matter volume, 42 hypoactivation in response to reading-related functional MRI tasks, 43 and weaker functional connectivity between key areas of the reading network. 44 Importantly, differences in brain structure and function characteristic of dyslexia can be observed before the start of formal reading instruction, indicating that dyslexia does not result from a struggle to learn to read but, rather, represents a biological disposition present at the preschool age or perhaps as early as infancy. 45 – 47 Altogether, these neuroimaging findings suggest that children predisposed to dyslexia enter their first day of school with a brain that is less equipped to learn to read.

It is worth noting that reading proficiency is strongly associated with socioeconomic status 48 – 50 : 80% of fourth grade students from low socioeconomic backgrounds read below grade-level proficiency. 51 In particular, children with inadequate exposure to language are more likely to struggle with reading. 52 However, the diagnosis of dyslexia does not include socioeconomic disadvantage as a potential cause. Although these children do not necessarily meet a diagnosis of dyslexia, children who struggle with reading, regardless of etiology, have been shown to suffer the same adverse health and psychosocial consequences and benefit from interventions that have been primarily developed to address deficits associated with dyslexia. 53 – 55

Although neuroimaging research has been invaluable in establishing the biological basis of dyslexia and reading impairments, neuroimaging technology (eg, brain MRI) does not have the ability to screen or diagnose dyslexia on an individual level, nor is it likely that this will be the case in the future. At this point, neuroimaging is not able to clearly disentangle differential neurobiological effects of dyslexia versus other reading impairments. 39 , 56 For these reasons and many others, cognitive-behavioral strategies are much more useful in screening.

The classic simple view of reading posits that skilled reading involves ≥2 major cognitive components: word recognition (including decoding and phonological awareness) and language comprehension (eg, knowledge of vocabulary and language structures); together, these strands coalesce to form what is classically known as the “reading rope.” 57 Although the simple view of reading has been borne out by evidence, 58 its components are not single entities but are multifactorial, malleable, and context dependent (especially language comprehension) and cannot be captured in a single assessment. 59 Furthermore, recent research has revealed that skilled reading, especially in older children, is contingent on knowledge of academic language and the additional cognitive skills of perspective-taking and reasoning. 60

In the past, dyslexia was diagnosed in the context of a discrepancy between reading ability and IQ, such that reading ability had to be 1 SD below cognitive abilities (IQ) for dyslexia to be diagnosed. However, this discrepancy model has been disproven, and dyslexia is no longer considered to be associated with IQ. 61

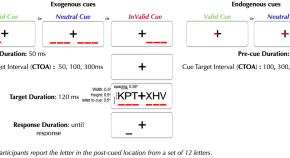

Dyslexia is related to deficits in ≥1 strands of the reading rope and particularly to early struggles in phonological and/or phonemic awareness. 62 Other predictors include struggles in letter-sound correspondence, pseudoword repetition (the ability to pronounce spoken nonsense words), identifying rhyming sounds, rapid automatized naming (the ability to automatically retrieve the names of objects, letters, or colors), and deficits in oral language comprehension and receptive and expressive vocabulary. 63 These measures have been shown to be strong predictors of reading ability in the English language; in other languages, the precursors vary, and screening approaches should be tailored to a child’s language environment. In this review, we focus on monolingual English speakers, however, and, among these children, these key linguistic and preliteracy measures can be assessed in children as young as 4 years old, and they can serve as crucial markers in identifying children at risk for dyslexia or other reading impairments. 64 – 66 Some of these literacy precursors measured in kindergarten have been shown to predict reading comprehension in the 10th grade. 67

As children progress through the school system, reading becomes the expected vehicle for content learning; thus, it is imperative that children with dyslexia are identified early and receive intervention without delay. When at-risk beginning readers receive intensive early reading intervention, 56% to 92% of these children achieve average reading ability. 68 However, many children are diagnosed with dyslexia long after they first demonstrate recognizable struggles with preliteracy milestones. 69 Currently, children are typically diagnosed with dyslexia at the end of the second or beginning of third grade (and many much later), after they have already failed to learn to read over a long period of time and have fallen behind their peers academically. 70 This wait-to-fail approach fails to capitalize on the most effective window for intervention, which is during an earlier period of heightened brain plasticity in kindergarten and first grade. 70 , 71 Referred to as the “dyslexia paradox,” 63 the gap between the earliest time at which identification is possible and the time at which identification and treatment typically occur can preclude effective intervention and has profound academic and socioemotional implications for the developing child. Children at the 10th percentile of reading ability may read as many words in 1 year as a child at the 90th percentile reads in a few days. 72

In addition to the poor academic outcomes associated with untreated dyslexia, diagnosing children after a prolonged period of failure can have severe implications for children’s mental health. Often perceived as lazy or labeled as “stupid,” children with dyslexia may develop decreased self-esteem, which can progress to anxiety and depression. 16 Furthermore, children with learning disorders are less likely to complete high school, 73 less likely to attend programs of higher education, 74 and at increased risk of entering the juvenile justice system: 28% to 45% of incarcerated youth 75 and 20% to 30% of incarcerated adults 76 have a learning disorder. Additionally, adults with learning disorders are more likely to be unemployed and, on average, earn annual incomes well below the national average. 5 Given the prognostic benefit of early diagnosis and intervention and the many adverse consequences that can be avoided or mitigated, there is great value in identifying early risk for dyslexia in the pediatric clinic.

It is important to distinguish between screening for dyslexia risk and diagnosing dyslexia. Screening refers to a brief assessment that determines the risk of having or developing dyslexia, which can be undertaken at an early age before school entry. 75 , 77 Conversely, a formal diagnosis can only occur after reading instruction has begun and requires a more comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation, which can be motivated by a previous screening result. 76 Although attention to both screening and diagnosis is vital in ensuring that the appropriate interventions are implemented for the child, screening for risk of dyslexia is possible earlier in the developmental time course than is diagnosis; thus, it represents an opportunity for expeditious early intervention.

The consideration of any screening regimen requires that a valid and acceptable test be available, an effective and accessible means of treatment be available, and the potential benefits of screening outweigh the risks 78 without an undue burden to the practitioner or patient. In the case of dyslexia, screening children individually for risk can be accomplished quickly and inexpensively through a consideration of family history and through short behavioral assessments of early literacy abilities. Extensive evidence has revealed the benefit of an early evidence-based response to screening, 70 , 79 , 80 and the risks of implementing a screening process are minimal to negligible. A review of a child’s family history of dyslexia is a worthwhile start to the process of early identification: a family history with positive results necessitates close monitoring, whereas a family history with negative results still requires a level of ongoing observation.

The risk of a false-positive result is present with any screening program, and, in the case of dyslexia screening, the risk is tantamount to further evaluation, monitoring, and educational supports. Although through these processes, demands are placed on the child and represent cost and effort on the part of practitioners, the burden of failing to identify these children early is ultimately greater than the burden of providing supplemental resources to a child needlessly. As discussed, although not all children who struggle with reading will meet the criteria for a dyslexia diagnosis, most children who struggle with reading will benefit from interventions designed to address dyslexia.

With the recognition that early literacy predictors of dyslexia can be identified before the start of kindergarten, 63 , 65 we can no longer afford to wait for screenings in children’s first formal schooling experiences. In a 2009 position article negating visual deficiencies as the origin of dyslexia, the American Academy of Pediatrics stated that pediatricians should “be vigilant in looking for early signs of evolving learning disabilities.” 81 The pediatrician's existing role in monitoring early child development and our understanding of the importance of early support for language and literacy development present pediatricians with the opportunity to implement dyslexia screening in well-child visits even before children are school-aged.

Pediatricians can contribute to a collaborative effort to screen for children at risk by capitalizing on their unique role in a child’s early developmental trajectory and by taking advantage of their network of health and educational resources. It is important to note that many parents desire this proactive stance from their child’s health care provider: more than one-third of surveyed parents indicated that they have not discussed reading with their pediatrician; nearly one-half of that group believed such conversations would be useful. 82 Pediatricians can also provide referrals to outside experts, such as neuropsychologists and SLPs, and communicate with patients’ schools. 83

Pediatricians typically rely on a developmental milestone checklist in evaluating a child’s development in various domains; however, recent research reveals that there is great variability between the many available checklists, both in content and milestone age ranges. 84 Furthermore, although receptive and expressive language is accounted for in these checklists, a comprehensive inventory of key early literacy measures that are crucial for assessing dyslexia risk is not included.

Early warning signs of dyslexia are visible before school entry 63 , 65 ; thus, the pediatrician may be a child’s first health or educational professional capable of identifying these signs and implementing a management plan. For example, pediatricians can document the extent to which a child can recognize rhyming sounds, repeat nonsense words, or report the sound that a letter makes. It is important to note that phonological deficits can present differently in different children, and children with dyslexia will vary in the specific tasks with which they show difficulty. Thus, screenings are used to pinpoint particular early literacy skills that may require remedial attention and also identify children who may eventually require a more detailed evaluation to come to a definitive diagnosis of dyslexia.

There are many methods by which pediatricians can work toward systematic early screening of dyslexia in their practices. Pediatricians should elicit a family history of dyslexia, recognize assessments done by schools that indicate a risk and/or diagnosis, and include dyslexia in the differential diagnosis for low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, or disruptive behaviors. The governing bodies of associations of pediatricians should provide training on dyslexia assessments and interventions as a part of ongoing continuing education so that pediatricians can become adept at implementing screening processes and at interpreting, monitoring, and responding efficiently to evaluations and interventions performed outside the clinic. The appropriate referral to outside consultants and interventionists should also be involved in this training when needed. Given the high overlap between dyslexia and deficits in speech and language, physicians should consider referring children who are at risk for dyslexia to an SLP who is trained in early literacy. 21 Furthermore, pediatric associations can partner with dyslexia researchers and education specialists to create educational resources and trainings that can assist pediatricians in providing education and support to their patients and families with or at risk for dyslexia.

Checklists, questionnaires, and interviews can be completed in conjunction with a child’s parent to assess a child’s key risk factors. Although these methods provide a quick account of a child’s risk, they are often tools that are not scientifically validated or reliable 85 and are thus intended for a preliminary formative assessment only. Commonly used questionnaires like the Ages & Stages Questionnaires, for example, can be helpful as a starting point but do not provide a detailed assessment. Rigorously validated screeners composed of child-centered behavioral assessments (see ref 86 for a nonexhaustive evaluation of screening tools) are used to provide a reliable and unbiased testament of a child’s risk status.

Pediatric clinics could consider hosting “screening days” with a literacy focus that can aim to simultaneously screen for early predictors of dyslexia while also facilitating a literacy-rich environment by making literacy materials available to families. Many pediatricians have already made great strides in promoting literacy within their clinics. The Reach Out and Read program has been effective in facilitating language and preliteracy skills in children through the distribution of books through primary care clinics. 87 A similar program with an additional screening component could be even more beneficial in supporting emerging literacy while also identifying children at risk for dyslexia.

A further possibility is the use of a standardized, brief 2- or 3-question first-step questionnaire, the likes of which have already been demonstrated to be successful in prescreening other conditions like depression 88 and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. 89 Although no such standardized questionnaire yet exists, pediatricians can pose questions to a preschool-aged child’s caregiver(s) pertaining to key risk factors for dyslexia. Affirmative answers to these first-step questions can be used to lead to a more detailed, validated screening tool that can be used to identify specific deficits present. There are storybooks and tablet- and smartphone-based gamified and self-administered screening tools currently being developed for the use in schools, clinics, or a child’s home. These tools are being designed to be entertaining for the child and will be informative to the clinician in determining the appropriate next steps and referrals for further evaluation and intervention.

As new screening tools continue to become available in the coming years, it will be important for practitioners to be knowledgeable about the characteristics of an appropriate dyslexia screener and discerning in their selection. The ideal screener has been validated in a representative sample; has strong evidence for reliability, validity, and classification accuracy; has developmentally appropriate content given the age or grade level of the child; and has the capacity to measure both word recognition and linguistic comprehension. 77 A list of available dyslexia screening tools, along with an indication of their fulfillment of characteristics like those listed above, is presently available for practitioners to consult (see ref 86 ). An additional resource for practitioners is the What Works Clearinghouse, which is used to provide evidence-based evaluations on literacy screening products as they become available. 90

In addition to child-directed assessments, given the strong heritability of dyslexia, a crucial component of early identification is an assessment of the reading history of the child’s parent(s) to determine the child’s familial risk of dyslexia. Family history is both quick to elicit and informative in the global assessment of a child’s risk. The Adult Reading History Questionnaire is an inventory 91 of an adult’s literacy abilities and habits and can be used to indicate a reading impairment (see ref 92 for a digital version). Follow-up questions should be presented to a parent with a high-risk score to rule out an environmental explanation for reading impairment (eg, lack of formal reading instruction). This distinction is particularly important to consider in communities with considerable immigrant populations, who may be flagged by the Adult Reading History Questionnaire as “at risk” simply because they are adult learners of the dominant language. Regardless of a parent’s dyslexia status, the quality of the home literacy environment is a strong predictor of reading outcome. 52 , 93 , 94 Thus, this parent inventory is useful not only because it can be used to indicate a child’s possible familial risk but also because it can reveal less literacy-rich home environments that leave children with insufficient literacy materials and support, illuminating additional targets for intervention.

Beyond the clinic, the medical community can be vocal advocates in national conversations about dyslexia, many of which are currently happening in state legislatures; as of now, only a few US states lack state-level legislation focusing on early screening, teacher training, and/or instructional support (for an overview of state legislation, see ref 95 ). Despite such recent attention, there is much room for growth in pediatric neurocognitive research funding, which has lagged compared to adult neurocognitive disorders. Increased funding and research must be used to explore etiologic models, examine comorbid relationships, refine tools for the early identification of children at risk for dyslexia and other reading impairments, investigate additional tools for use in children for whom English is not their first language, and develop and evaluate intervention strategies and their effectiveness. A first-order goal should be the development of screening guidelines and tools for use during pediatric visits for 4- and 5-year-old children that can be used to identify children at risk before the optimal window for early interventions closes, while also refining guidelines to identify older children who were not screened earlier. Finally, with the help of policy makers, the current “failure” model of dyslexia must be replaced with a “support” model that enables school-, clinic-, and community-based early screenings and subsequent evidence-based response to screening through empowered and well-trained teachers within the general education framework. Physicians can be powerful agents of these positive changes, both at the level of their clinical practices and as advocates in their communities and beyond.

Our current knowledge of the neurobiological basis for dyslexia, its reliable developmental-behavioral predictors, the effectiveness of early intervention, and the myriad adverse effects of reading failure reveal a demand for a proactive, preventive approach (instead of a deficit-driven approach) to identify and treat children at risk. Early identification should start with an assessment of family history and should be followed with validated behavioral screening tools. After a positive screen, referrals to diagnosticians such as SLPs or neuropsychologists should be made. Diagnoses, when they occur, should be followed with letters to schools requesting the implementation of literacy intervention.

With time, new and innovative formats for screening will emerge. In acknowledging the significant effort devoted by pediatricians to screening various conditions, the future will require a consideration of novel approaches to office visits or increased community-based collaboration with preschools to accomplish screening for disorders that, like dyslexia, are of nontrivial prevalence and are associated with available and effective interventions. Pediatricians occupy a unique role in the lives of children such that they are well positioned to recognize and respond to risk factors for dyslexia even before children enter the education system; however, the delivery of dyslexia interventions is and will largely continue to be implemented outside the scope of the pediatrician’s practice. Thus, the contributions of both pediatricians and other health and educational professionals are crucial to optimizing the process of identifying and treating dyslexia. Although the response to dyslexia screening and intervention is multifaceted and longitudinal, the trajectory of children’s literacy outcomes has the potential to be improved through the implementation of early identification in pediatric practice.

Drs Gaab, Rappaport, and Zuckerman conceptualized the review, participated in the drafting of the initial manuscript, and continuously reviewed and revised the manuscript; Mr Sanfilippo conducted the literature review, led in the writing and design of the final manuscript, consolidated coauthor feedback, and continuously revised the manuscript; Drs Ness and Petscher contributed their respective expertise in writing significant components of the manuscript and reviewed and revised the manuscript throughout; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: Funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant R01 HD065762). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

speech and language pathologist

Competing Interests

Re: a pediatrician’s role in dyslexia: where theory meets practice.

I want to applaud the article by J Sanfilippo and colleagues titled ‘Reintroducing Dyslexia: Early Identification and Implications for Pediatric Practice.” This article joins other recent articles and position statements that call for pediatricians to view literacy as a developmental domain and to participate in screening for future literacy concerns as early as preschool age.1-3 As a pediatrician, I agree wholeheartedly with their statement that “The development of reading proficiency in childhood is a public health issue.” The evidence linking lack of reading proficiency with school failure, lack of meaningful employment, and involvement in the criminal justice and welfare systems is robust, as is the mental health consequences of reduced self esteem, anxiety and depression. As pediatricians we should be aware of and attempt to modify all of these negative outcomes by helping to identify risk factors for future reading disabilities and referring our struggling readers for further evaluation and remediation if available.

Yet, is it really that simple? To answer this question I would like to point out the current barriers out there that make executing the article’s recommendations difficult if not near impossible. My perspective is based on my experiences as a community pediatrician who currently cares for mostly low income Medicaid patients, many of whom come from non-English speaking households, as well as from my experience being the parent of a now 10 year old daughter with dyslexia. As a disclaimer, this perspective is based on the educational landscape of my State of Colorado where I live and may not be representative of other educational and healthcare systems.

Our oldest child was first pulled out for reading intervention in the first grade. Despite my pediatric training, I was ill prepared to interpret what screening and interventions the school was providing her and I trusted that the school would know to teach her how to read. By middle of 2nd grade, after 18 months of intervention without improvement, my pediatrician spidy-sense told me it was time to get her privately tested. She seemed to be on the wait to fail trajectory which statistically occurs in 4th or 5th grade when the child has entered into the reading to learn stage. The results of her private testing revealed what I knew in my gut all along, she has dyslexia. We brought the 13 page evaluation to our school with lists of accommodations and recommended intervention expecting that all would now be fine. It wasn’t. The intervention provided her was ineffective (as it had been prior) and her teachers could not seem to accept that she had dyslexia. Not even an IEP could grant us recommended modifications for her.

It was not until I listened to the eye-opening documentaries of Emily Hanford from American Public Media4-7 that the light bulb went on as to why the school was reacting this way. Many years ago education abandoned the teaching of phonics for whole language and balanced literacy which teaches our children to guess at words rather than decode them. What all children need, especially struggling readers, is systematic and explicit phonics that is based on the science of reading. Yet to my dismay, many teacher preparation programs still do not teach the science of reading. In fact, in Colorado, the largest teacher prep program was cited again by the State Board of Education for “failure to adequately prepare students to teach children how to read.”8 Perhaps this is why in 2018 State testing showed that only 40% of Colorado third graders were reading at grade level. Another likely reason for this is many Colorado schools are not using reading curriculum approved by the Colorado Department of Education (CDE).9,10

What my dyslexic daughter needed was Structured Literacy which can be found in the explicit multi-sensory scope and sequence approach of programs such as the Orton-Gillingham (OG) method. This was not available in her classroom so we paid privately for twice weekly OG tutoring and moved her to a public charter school who used an approved CDE reading curriculum and required all K-3 teachers to be trained in Structured Literacy. The result has been life changing for my daughter’s mental health and reading proficiency.

However, I wish I can say that my low income pediatric patients who are struggling readers and who are experiencing the behavioral and mental health consequences of school failure have had the same experience. Their school may proceed slowly with Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS)11 that relies on response to intervention as well as literacy assessment tools such as iReady12 and Istation13 that do not always provide important data on word level reading and oral reading fluency. The article mentions that pediatricians should become adept at interpreting and responding to these educational assessments and interventions which I believe are out of the scope of pediatric practice and to circumvent this I have relied on professional courtesy of qualified educational neuropsychologists and speech-language pathologists to interpret these for me.

For my patients who have IEPs, their parents are typically not aware of the type of intervention the child receives or whether the school’s reading curriculum is supported by the science of reading. Even in the rare case I have been able to secure grant funding for a private evaluation that confirms dyslexia, the child’s school usually does not have qualified staff trained in Structured Literacy to remediate it. As the child’s pediatrician, there are few if any outside referral options for Structured Literacy reading intervention as not all speech language pathologists have the additional training in literacy nor do insurance payers typically cover reading intervention.

It is heart breaking for me to see my patients year after year for their well child exam and not know how to help them overcome all of these systemic barriers that prevent them from obtaining grade-level reading proficiency. Understanding the glacial speed that my local school systems are moving toward structured literacy and science-based reading curriculum, all that we pediatricians and parents of dyslexic children have left is advocacy to create more immediate resources for our struggling readers that are external to the child’s school yet work symbiotically with it. What we need are programs like the Promise Project14 that can be grant funded and implemented to provide identification and remediation for all children with significant reading deficiencies while continuing to advocate at the State level for continued educational reforms in teacher preparation programs and science-based reading curricula. Pediatricians also need to advocate for State legislation that requires insurance payers to cover evaluations as well as remediation for children with dyslexia given the preponderance of medical evidence of its neurobiological origin. Insurance coverage that provides access to early identification and remediation of dyslexia could mitigate commonly associated physical and mental health ramifications of stress, anxiety, depression, and suicide that result in great personal and economic costs later on.

References: Literacy as a Distinct Developmental Domain in Children. JAMA Pediatrics March 30, 2020 Pediatricians Have a Role in Early Screening of Dyslexia. Examiner, Volume 8, Issue 3. October 2018. Available at https://dyslexiaida.org/an-invitation-to-pediatricians-for-early-dyslexi... School-aged Children Who Are Not Progressing Academically: Considerations for Pediatricians. Pediatrics 2019;144. Hard Words Why aren’t kids being taught to read. Available at https://www.apmreports.org/episode/2018/09/10/hard-words-why-american-ki... At a Loss for Words How a flawed idea is teaching millions of kids to be poor readers. Available at https://www.apmreports.org/episode/2019/08/22/whats-wrong-how-schools-te... Hard to Read. How American schools fail kids with dyslexia. Available at https://www.apmreports.org/episode/2017/09/11/hard-to-read New salvos in the battles over reading instruction. Available at https://www.apmreports.org/episode/2019/12/20/new-people-organizations-r... Colorado’s largest teacher preparation program dinged over reading instruction — again https://co.chalkbeat.org/2020/6/9/21285846/colorados-largest-teacher-pre... Colorado wants schools to use reading curriculum supported by science. Here are the ones that made the cut. https://co.chalkbeat.org/2020/4/23/21233583/colorado-wants-schools-to-us... Why do so many Colorado students struggle to read? Flawed curriculum is part of the problem. https://co.chalkbeat.org/2020/3/27/21231320/why-do-so-many-colorado-stud... Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS). Available at https://www.cde.state.co.us/mtss/handouts-mtss-overviewshpgbreakoutsept-... iReady. Available at https://www.curriculumassociates.com/products/i-ready/i-ready-tour-seein... ISTATION READING. Available at https://www.istation.com/Reading Promise Project. Available at https://www.promise-project.org/promise2/ ?

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Evolving concepts of dyslexia and their implications for research and remediation.

- Department of Special Needs Education, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Aspects of dyslexia definitions are framed as a contrast between the past and the future, focusing on implications for research and remedial education, highlighting assumptions that bias or limit research or clinical practice. A crucial development is evident in understanding dyslexia, moving from its conceptualization as a discrete identifiable condition toward the realization of continuity with the general population with no clear boundaries and no qualitative differences. This conceptual evolution amounts to a transition from considering dyslexia to be some entity that causes poor reading toward considering the term dyslexia to simply label poor reading performance. This renders obsolete any searches for abnormalities and directs efforts toward understanding reading skill as a multifaceted domain following a complex multifactorial developmental course.

Introduction

In this paper, I discuss aspects of definitions of dyslexia framed as a contrast between the recent past – a few decades – and the near future – the next decade or so. I only consider what I judge to be “primary” definitions, aimed at providing a conceptual understanding, rather than diagnostic criteria or guidelines aimed at practical clinical application (e.g., DSM-V: American Psychiatric Association [Apa], 2013 and ICD-11: World Health Organization, 2018 ). 1 Such clinical guidelines are secondary to conceptual definitions in the sense that they can only express attempts to operationalize concepts as understood by a community of researchers and/or practitioners. I then focus on implications, because that is where it matters most, and also because definitions reflect assumptions that may bias or limit our research or clinical practice without our noticing. One valid approach to this topic might be to discuss specific definitions at some length, pointing out advantages and disadvantages, what they imply and how they can be applied. Instead of that, I take a more general look, abstracting away from specific definitions, and focusing on common themes that distinguish the past from the future.

First of all, why define dyslexia? What is the point of even having definitions? One reason might be to express our understanding. That is, once we know exactly what something is and is not, we can construct a definition that distils our understanding into a clear, concise statement of who belongs to the category and who does not. Applying such a definition would be straightforward and would indicate unambiguously whether an individual falls under the domain of the definition or not. An alternative reason might be seen in very different situations, when it is not clear at all how to distinguish members from non-members; when, despite our efforts, the situation remains complex, with obvious disadvantages to any proposals, and an impasse is reached. Then, we may try to impose a definition, in essence to command a somewhat arbitrary set of choices, just to be able to move forward. We would not normally do that, instead of trying harder to understand, but there are situations when practical needs of classification prevail, as in dyslexia: we need to be able to decide whether we should treat any particular individual child one way or another.

In the case of dyslexia, this issue has been extensively discussed. In a recent book that has attracted much attention, Elliott and Grigorenko (2014) listed a number of different “understandings of who may be considered to have dyslexia” (p. 39). For example, the term may refer simply to anyone who struggles with accurate single-word decoding; or to those with a more pervasive condition marked by various comorbid features and symptoms; or to those with a significant discrepancy between decoding and another measure such as IQ or listening comprehension; or to those with a certain cognitive profile associated with their reading difficulty; and there are several more possibilities. In other words, there is a very wide range of different uses of the term dyslexia, and associated definitions. So, as far as understanding goes, it seems fair to conclude, as Elliot and Grigorenko did, that although “it is incontrovertible that there is a significant number of individuals who struggle to learn to read, … achieving a clear, scientific, and consensual understanding of [the term dyslexia] has proven elusive” (p. 38). In other words, there is no clear understanding. So, our definitions of dyslexia are not meant to express understanding but, rather, to serve pressing practical needs.

What are these practical needs that require a definition of dyslexia? For research, we need to know how to form our research groups. That is, whom to study, in order to understand dyslexia, and whom to exclude. A definition also dictates what we should measure to document the group inclusion and to examine the features of the classification. Similarly, in education, we need to know which children are selected for remedial services, a decision of the utmost importance given that poor literacy is associated with poor academic, social, behavioral, emotional, professional, financial, and health outcomes (e.g., Goldston et al., 2007 ; Gross et al., 2009 ; Undheim et al., 2011 ; McLaughlin et al., 2014 ). The definition also directs our assessment and educational programs, by highlighting what needs to be assessed to justify the selection, to document the relevant educational needs, and also to guide the setting of specific objectives to be achieved by remedial education.

Elements of Dyslexia Definitions

Table 1 lists a few selected definitions proposed over the past several decades up to the present time. Before considering the differences between past and future, let us begin with a common element weaving through our understanding of dyslexia across time, taking various specific forms in different approaches, but expressing an underlying unifying theme. This is the element of unexpectedness of the reading difficulty. That is, dyslexia is seen as a difficulty or inability to learn to read in a situation where we would have expected success. This is an important element because it reflects the notion that, in contrast to oral language, reading doesn’t just come naturally and universally (cf., Liberman, 1995 ). The idea is that there is some set of conditions under which we would expect children to learn to read, and for some children that does not happen.

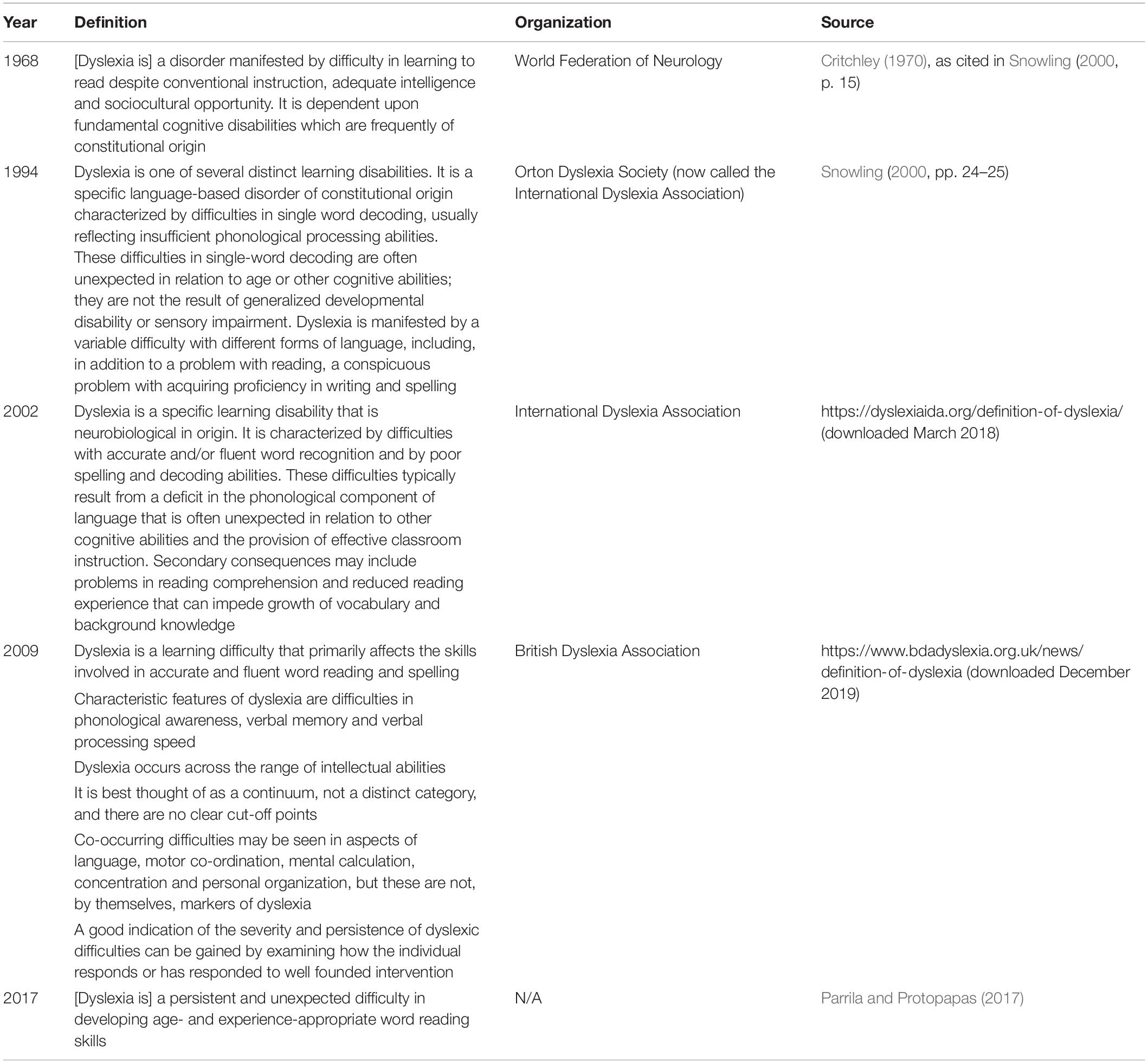

Table 1. Selected definitions of dyslexia.

Stated this way, the notion of unexpectedness is very vague. What is the basis for the expectations? This is a domain in which we see some evolution in our thinking, both in the kinds of conditions we consider conducive to reading, or necessary for reading, as well as in how the conditions are operationalized, sometimes forming exclusion criteria in a definition.

The first element contributing to expectation is age and experience. Clearly, a 4-year-old cannot have dyslexia, by definition. This is because at this age most children are not yet mature enough in their metalinguistic skills to be able to acquire reading. So, being unable to read at 4 years of age is normal, and expected. We also will not think that a child who cannot read has dyslexia if the child has not been sufficiently exposed to print or has not practiced reading. This is because reading skill does not develop spontaneously but requires substantial experience with print. So, a child who has not practiced reading is not expected to be able to read.

A second element concerns limitations arising from sensory perception. This expresses the intuitive notion that a child who cannot see well is not expected be able to read, because seeing the letters is obviously necessary for reading them. Similarly, though indirectly, a child who cannot hear well is not expected to have formed adequate representations of the speech sounds, that is, the phonemes, to which the letters map. Therefore, a hearing-impaired child is not expected to be able to learn to read well, at least not without extraordinary effort.

A third element concerns educational opportunity. This is not as straightforward to apply, but it is also based on the concept that reading does not develop spontaneously. So, we do not expect children to read unless they have been taught to read. This may mean that the child must at least attend school regularly, or have alternative instructional interactions to fulfill this role. In other approaches this element involves not only the existence of teaching but also the teaching method applied. Under this view, if children are not taught properly then we do not expect them to learn to read. So, a child who fails to make progress with one teaching approach, but then learns to read successfully using a different teaching approach, was not reading disabled in the first instance but, rather, “teaching-disabled” ( Tunmer and Greaney, 2010 ).

Finally, general cognitive ability is an element commonly seen as related to the expectation of reading competence. This has taken various specific forms, some of which have led to great controversy. In the past, it was thought that at least average cognitive ability is necessary for learning to read, so we should not expect a developmentally disabled child to be able to read. This idea has not survived, because it has been shown that children with general intellectual disabilities, such as Down’s syndrome, can learn to read ( Snowling et al., 2008 ; see also Næss, 2016 ), even though their understanding of what they read can only be commensurate with their general intellectual functioning. Nevertheless, some element of general cognitive ability is still included, in some form or other, in most approaches to dyslexia, even though the original notion of unexpectedness can no longer be sustained, perhaps for more practical reasons. For example, in education, cognitive ability can help distinguish children with dyslexia from children who cannot read successfully in the sense of not understanding what they read, which is a very different sort of reading failure ( Catts et al., 2006 ; Nation and Angell, 2006 ). That is, the notion of dyslexia concerns the “mechanics” of reading, and not the comprehension of the written text, which is largely independent from word-level skills past the beginner stage ( Bishop and Snowling, 2004 ; Nation, 2005 ). In research, an element of cognitive ability is included to ensure that participants in studies can respond similarly to the requirements of the tasks.

Beyond the common elements, which are seen in one form or another in most definitions, there are various additional components that are found in some approaches, but not all. For example, a 1994 definition from the Orton Dyslexia Society (today known as International Dyslexia Association) also included these terms: distinct, specific, constitutional, language-based, insufficient phonological processing, affecting single-word decoding, and difficulty with different forms of language, writing and spelling ( Snowling, 2000 , pp. 24–25; see Table 1 ). This approach was typical for its period. We can see that very different kinds of components were involved, ranging from assumptions about the nature of dyslexia to correlates and domains of symptoms. These are the kinds of things that have evolved over the decades. So, now we can turn to the discussion of such elements in a contrast between the past and the future.

Progress in Understanding Dyslexia

As I mentioned earlier, we will not consider specific entire definitions. Rather, I will discuss elements found in definitions, as they express our attempts to understand what dyslexia is and to delineate what dyslexia is not. Let me start with the easier ones, in the sense that they seem to be mostly resolved already, having made much progress from the recent past, so that the future is likely going to be like the present in regard to them.

As already noted, the level of cognitive ability has played an important role in the concept of dyslexia. For a long time, and to some extent still seen in some places, an IQ discrepancy criterion has been applied, so that a child cannot be called dyslexic unless there is a substantial difference between general cognitive ability and reading skill. This was based on an expectation that intelligence determines word reading ability, which it does not; and on the assumption that intelligence makes a difference in how word-level reading difficulties should be remediated, which it does not ( Elliott and Grigorenko, 2014 ). So the present approach, to a large extent, and the future approach, is that the concept of dyslexia is not defined against some IQ reference, and instead it is applied across ability ranges ( Vellutino et al., 2004 ).

Another feature of the past is the list of various types of symptoms supposedly associated with dyslexia. This includes assortments of observations such as clumsiness, poor balance or poor sense of rhythm, left-handedness, ability to distinguish right from left, and so on. It also includes difficulties with other kinds of skills not directly related to reading, such as arithmetic, language, attention, visual and auditory perception, and others. For some of these there is evidence that they are found more frequently in poor readers than in typical readers; for others there is little empirical support ( Ramus and Ahissar, 2012 ; Protopapas, 2014 ). But in any case these symptom lists cannot be part of the concept of dyslexia and have been, or are being, abandoned. The only skills that are relevant to the concept – and therefore the definition – of dyslexia are reading skills, at the word level ( de Jong and van Bergen, 2017 ; although an argument can be made for a confirmatory role of testing specific well-attested reading-related skills; Pennington et al., 2012 ).

Speaking of reading skills, many definitions refer specifically to “decoding” skills, which concern processing of single words, and can be said to be sufficient when single words are pronounced correctly. This has proven to be insufficient in that word-level skills are not exhausted with accurate singe-word decoding, but also encompass reading fluency, which refers to the speed, or efficiency, of processing ( Fuchs et al., 2001 ; Wolf and Katzir-Cohen, 2001 ) and, crucially, involves word sequences rather than isolated words ( Protopapas et al., 2018 ; Altani et al., 2019 ). We must retain a distinction from comprehension, because comprehension concerns an altogether different set of skills and associated difficulties ( Catts et al., 2006 ; Nation and Angell, 2006 ; Oakhill et al., 2014 ). But focusing on decoding alone is not the right point at which to draw the line, because it leaves out the efficient processing of word sequences, which precedes and facilitates comprehension. Rather, the line is to be drawn between reading comprehension, on the one hand, and both decoding of individual words and fluency in reading word sequences, on the other.

Turning to more abstract notions, a crucial development is evident in the concept of dyslexia as a discrete identifiable condition, most evident in educational and clinical settings ( Elliott and Gibbs, 2008 ), moving toward the realization that there is no discrete condition but, rather, continuity with the rest of the population, with no clear boundaries and no qualitative differences. This is not a novel idea. The question of whether dyslexia makes up some special population, outside of the general distribution of reading skill, has been investigated for some time now. Over the past decades, it seems increasingly accepted that there is no distinct group and that dyslexia concerns the low end of the distribution of reading skill ( Ahmed et al., 2012 ; Snowling, 2013 ; see Protopapas and Parrila, 2018 , for more references).

Closely related to the notion of a discrete condition is the conceptualization of causal factors. The recent past, and indeed the present to a large extent, is dominated by views of dyslexia as caused by some specific factor. This makes sense if dyslexia is a specific condition. But once the notion of a qualitative distinction is discredited, the single-cause approach loses much of its appeal. And the same holds for theoretical attempts building on two – or even three – specific factors. Instead, recent evidence from genetic and behavioral analyses, and a reconceptualization of developmental courses, suggest that the roots of dyslexia are traced to many interacting factors at different levels of description, and that different routes can lead to similar outcomes, so that even a common difficulty is not necessarily attributable to a common history ( Pennington, 2006 ; Snowling, 2011 ; van Bergen et al., 2014 ; see Parrila and Protopapas, 2017 , for discussion).

In this context, it is instructive to consider another common element in definitions, namely the “constitutional” (or “neurobiological”) origin. This reflects the belief that one is born dyslexic, often taken to imply that one’s genes alone determine whether one will learn to read easily or not. If that were true, then pairs of identical twins, who have exactly the same genes, would always either both have dyslexia or both not have trouble learning to read. This is in fact not the case; more recent estimates of the concordance of monozygotic twin pairs in dyslexia seem to hover around 70%, as do estimates of heritability for reading skill measures ( Grigorenko, 2004 ; Scerri and Schulte-Körne, 2010 ; Christopher et al., 2013 ; Bishop, 2015 ). This means that there is indeed a strong genetic component in propensity to acquire reading skills and in family risk for reading difficulties ( Swagerman et al., 2017 ), at least within the fairly homogeneous environments in which such studies are typically conducted. But this should not be interpreted as implying that one is doomed by their genes. That is because, first, estimates of heritability in less homogeneously supportive environments are lower ( Bishop, 2015 ). And second, because it is increasingly understood that the final behavioral outcomes, as noted above, depend on a multitude of interacting factors, only some of which concern genetics ( Mitchell, 2018 ). Moreover, the way genetic factors are ultimately expressed involves environmental – hence pliable – circumstances, not limited to instruction but also potentially involving motivation, expectations, language, the creation of opportunities, the availability of resources, and more ( van Bergen et al., 2014 ). In short, our understanding of what heritability means and how it should be interpreted is under major revision.

A related point is the characterization of dyslexia as a neurodevelopmental disorder, which is still seen often today (indeed in both main diagnostic manuals, DSM-V and ICD-11). Although it seems that some use this term to simply mean that many children have difficulties in learning to read because of how their brain is set up (rather than because of poor teaching, or poor character, for example), which is likely true, this is not an appropriate use of the term. According to the dictionaries, “disorder” in this sense is a medical term which means “a physical or mental condition that is not normal or healthy,” 2 “a derangement or abnormality of function; a morbid physical or mental state,” 3 “an illness that disrupts normal physical or mental functions,” 4 “a disturbance of physical or mental health or functions.” 5 In other words, it means “disease.” More specifically the term “neurodevelopmental disorder” is specifically associated with disrupted and impaired brain development ( Bishop and Rutter, 2008 ; Thapar and Rutter, 2015 ), that is, a brain fault. This is unfortunate and inappropriate, turning a social and educational issue into a medical one. It is a view that will not prevail, in my opinion, because despite many efforts there are no indications of abnormality at any level of description, either genetic or neurological or cognitive or linguistic. There is much evidence confirming the existence of differences between groups of people with and without reading problems across some of these domains, but this kind of evidence is nowhere near establishing neurodevelopmental failure (see Protopapas and Parrila, 2018 , for extensive discussion). Unfortunately, this issue is muddled by some researchers, who inappropriately use terms such as “neurological disorder” based on average differences between groups with and without dyslexia, with no evidence of disturbance or malfunction of the nervous system.

Importantly, documentation of group differences does not amount to evidence for abnormality. Consider a hypothetical comparison between top world-class violinists or gymnasts to “typical individuals”: it should be clear that some differences must exist in the structure and function of their central nervous systems, compared to the non-athletic or non-musical group, because it is only such neural differences that can account for the observed differences in athletic or musical performance. If the differences cannot be fully documented it is because our methods are still inadequate. So, in this sense it is trivial to document group differences in nervous system structure and function when differences in performance have been observed. This would not lead us to characterize the individuals with deviations from average performance as neurologically disordered. Likewise, group deviations – even extreme ones – from the average reading performance should hardly be characterized as “neurological disorders” but, rather, as expected occurrences in the context of individual variability ( Protopapas and Parrila, 2018 ).

In other words, children with dyslexia are just a part of the general distribution, normal in all respects (except in response to literacy instruction), and their brains are within normal variability. The only domain in which a clear discrepancy is found is learning to read. However, reading is a cultural invention and a recent social development, which has led to educational systems and to the pressure for universal literacy. Of course these are all very positive developments, but this has nothing to do with the characterization of poor response to the cognitive demands of learning to read. Consider this analogy: If an otherwise perfectly normal child cannot learn to sing, or to compete in sports, despite substantial practice and efforts from teachers and coaches, would we consider that to be a neurodevelopmental disorder? I think not, and I think that this is where our understanding of dyslexia will take us – and should take us – in the near future. Of course the critical difference is that being clumsy or tone deaf has few, if any, consequences for life success, whereas poor reading is severely handicapping in the modern literate society, as noted above. Thus it is of crucial importance for every state to provide adequate means toward assessment and remediation of reading problems, not because of purported brain faults but because of the poor reading itself ( Protopapas and Parrila, 2018 , 2019 ).

To sum up, our concept of dyslexia, reflected in the evolution of definitions and discussions of the topic over the past decades, seems to be moving from a kind of natural category, to that of an educational label. That is, dyslexia is not some objective physical condition that occurs naturally and inherently characterizes some children, regardless of their linguistic and educational context and of whether or not they ever try to learn to read. Rather, it is a label applied in the context of specific social circumstances, demands, and pressures. This does not change the fact that certain children have great difficulty learning to read; that this is because of how their brains are set up; 6 that they need special support to be able to function adequately in a literate society; or that society must provide that support. But it does change how they are viewed and what is to be done.

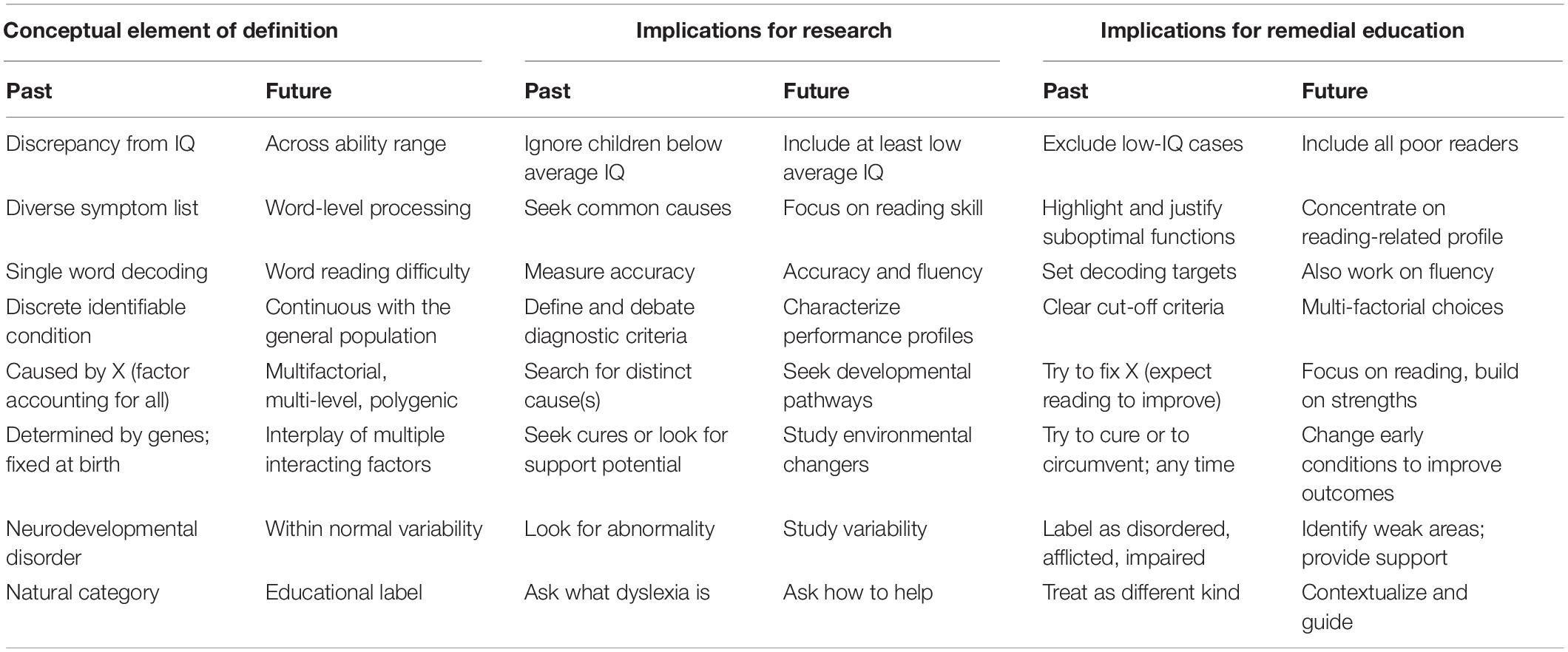

So, in what follows I will consider the implications of these elements, in the same order, focusing on how they have changed or are changing, from the past to the future. Let us start with implications for research.

Implications for Research

When dyslexia is defined by discrepancy from IQ, this effectively increases the average IQ of study participants and ignores poor readers with low IQ, resulting in unrepresentative samples for research, and possibly unrepresentative findings in domains other than reading. Current research practice has escaped from discrepancy criteria but has retained a criterion of at least average intelligence. This is aimed to increase the homogeneity of research samples and mainly to avoid criticism that some findings, beyond reading performance, might be attributed to low cognitive ability.

When dyslexia is characterized by diverse symptom lists, it is tempting to try to find unifying explanations, that is, common causes for all observed symptoms. But if the symptoms aren’t reliably associated with dyslexia then this search is counterproductive. By focusing on the only common element across children with dyslexia, that is, the difficulty in learning to read, research can concentrate on identifying the necessary set of underlying skills and development routes, rather than trying to account for assorted, anecdotal, or simply unreliable elements.

When dyslexia is thought to specifically affect decoding, research will naturally focus on reading accuracy and on the cognitive and linguistic skills underlying accurate decoding. This is largely an artifact of English being spoken in the countries in which research was better funded, because English is an outlier orthography in which learning to read accurately is difficult, in contrast to other European orthographies ( Share, 2008 ). Fortunately, with the progress of cross-linguistic research, and with data now available on many languages and orthographies, it has become clear that development of fluency is also very important, and must be studied on its own in addition to accuracy ( Wolf and Katzir-Cohen, 2001 ; Kuhn et al., 2010 ).

If dyslexia is thought to be a specific identifiable condition then it is natural to search for clear criteria to demarcate it, and to debate definitions including or excluding these criteria. This direction loses its force if dyslexia is considered continuous with the general population, because the research focus shifts to the characterization of performance profiles, to the establishment of reliable and unreliable features, and to the quantification of different effects and contributions. In other words, this is a shift from qualities to quantities.

Similarly, if we expect that dyslexia is caused by a specific factor, or set of factors, then we will naturally put our efforts into identifying this factor and its effects. This has occupied several productive groups for decades, and there is no end to the proliferation of theories about what the distinct causes of dyslexia are (see Elliott and Grigorenko, 2014 , for discussion of some of them). However, if we view the unsuitability of a brain for learning to read not as a product of some specific factor but, rather, as the product of a complex developmental pathway, in which genetics and environment act and interact to produce a complex phenotype, then attention is shifted to understanding these developmental pathways, the ways in which they differ, and their sensitivity to different manipulations. This is a very different kind of research program, eschewing simplistic dichotomies between “dyslexic” and “non-dyslexic” groups and their – often uninformative and potentially misleading – average differences, in favor of studying the graded effects of a multitude of risk and protective factors over multiple levels (genetic, neural, cognitive, behavioral) and their associations and interactions across levels of reading skill, ages, environments, and generations ( van Bergen et al., 2014 ).

As noted by Bishop (2015) , “a genetic aetiology does not mean a condition is untreatable.” Even though it is important to recognize limitations set by genetics, a better understanding of how genes work can help us focus on addressing specific difficulties of specific persons in specific ways rather than applying blanket measures, and possibly in the future to be able to further customize and individualize our approach beyond what is behaviorally observable. Having a better view of the scope and extent of environmental influence, we can focus on maximizing the efficiency of interventions. Two important avenues in this regard involve (a) identification of reliable precursors (i.e., risk factors) that can support valid early screening, well before literacy instruction, and (b) the development of interventions with validated long-lasting effects. Both of these are exemplified in the Jyväskylä Longitudinal Study of Dyslexia, which has produced both leads related to precursors as well as an applied framework for early intervention addressing crucial skill domains ( Lyytinen et al., 2008 , 2015 ; Solheim et al., 2018 ). The importance of early screening and intervention is highlighted by empirical confirmation of the longstanding assumptions that (a) when it comes to intervention, earlier is better ( Lovett et al., 2017 ), and (b) kindergarten training in the foundational domain of phonological awareness has clinically significant effects lasting through secondary education ( Kjeldsen et al., 2019 ). In this context, further research can transcend monolithic – and possibly misguided – approaches to the causes and outcomes of reading failure and address the efficiency of behavioral assays and environmental changers down to the level of the individual.

In other words, research should stop trying to answer the question “what causes dyslexia?” and instead put more effort into understanding the observed range of reading development trajectories and the extent to which different factors affect learning to read in different ages, genetic and environmental contexts, and instructional situations. This presupposes a major shift in underlying assumptions in that reading failure shall not be conceived of as the result of some critical early failure but, rather, as the cumulative outcome of multiple, potentially interacting, risk and protective factors, which may affect the developmental and instructional “initial conditions” as well as growth rates and environmental interactions along multiply determined individual paths.

Along these lines, if dyslexia is seen as a disorder, then by definition something is abnormal, and our job as researchers is to find it, characterize it, and try to cure it. However, if difficulty in learning to read is seen as part of cognitive variability, just individual differences as usual, then our job is to study and to understand this variability, the dimensions of variability, its causes and correlates, without being on the look for something abnormal.

Finally, if dyslexia is thought to be a condition, inherent in some children, then it is some kind of natural distinct entity and it makes sense to ask what exactly it is. In contrast, if we think of dyslexia as an educational label, then there is no reason to study its essence. Rather, we can concentrate on the features and contexts associated with this label and focus our research on the effects of interventions.

Now let us turn to implications for remedial education.

Implications for Remedial Education

If you define dyslexia as a discrepancy from IQ, then you exclude low-IQ children from receiving remedial services to ameliorate their poor reading. This is not only unethical, as you deprive children of the help they need; it is also incorrect, because, as noted above, there is no difference in reading intervention or in prognosis based on IQ. In contrast, if cognitive ability does not factor into your definition, then children can be eligible for remedial services on the basis of their reading performance, which is the only relevant factor.

If you define dyslexia as a constellation of assorted symptoms, then you may waste time, efforts, and resources, in assessing – and perhaps addressing – various irrelevant domains, for example, fine motor coordination, balance, auditory skills, or general visual or oculomotor skills. In contrast, if your concept of dyslexia focuses on reading skill, then your assessment and intervention will also focus on reading skill. Let me clarify here that I do not imply that only reading should ever be assessed, or that only reading skills should be practiced, for two reasons. Although only reading is relevant for diagnosing dyslexia ( de Jong and van Bergen, 2017 ), much more is needed when it comes to intervention . First, a wider cognitive and learning profile may be necessary for the special educator or educational psychologist, to identify the weak and strong areas for any given child, because the individualized educational plan will have to be based on the strengths and build from them to address the weaknesses, including weaknesses in reading and possibly others, thereby comprehensively addressing the needs of the child. And second, reading is itself dependent on certain linguistic and meta-linguistic skills and prerequisite knowledge ( Vellutino et al., 2004 ; Melby-Lervåg et al., 2012 ). So, the specialist will consider and may have to support the development of phonological processing, phonological memory, phonological awareness, knowledge of the alphabet, and conventions of print, before reading itself can be addressed. This is not because dyslexia is thought to be an assortment of disconnected clumsiness, but because reading skills are documented by research to build on prerequisite skills and, in turn, to form the basis for additional skills to build on them later.

If you define dyslexia as an impairment in decoding, then you will focus intervention on decoding, and you will consider your job done when the child reads accurately. But your job is not done, because the child may read so slowly as to be functionally illiterate (cf., Torgesen, 2005 ). Word reading speed can only begin to develop after high accuracy has been achieved, while attainment of reading fluency requires additional skills beyond isolated word reading speed ( Juul et al., 2014 ; Altani et al., 2019 ). Thus, word-level skills must build to an efficiency level that can sustain reading to learn. By acknowledging this wider concept of word-level reading, and consequently by allowing low fluency to factor in the concept of dyslexia, your assessment and intervention efforts will naturally include fluency as an assessment domain and remedial target, leading to better functional outcomes.

If you think of dyslexia as a discrete identifiable condition then you will seek to apply clear criteria to determine who should receive remedial services, and you will expect unambiguous classification from your criteria. You will think your criteria are incomplete or incorrect when they fail to meet this standard. However, if you admit that dyslexia is continuous with the general population then gray areas and ambiguities are inherently expected. Therefore your assessment and your remedial goals will be accepted for what they are, namely multi-factorial choices, where some things may not be very clear or may be treated differently in different contexts. This requires the exercise of more judgment on behalf of the clinician; but this is why we need expert, well-trained clinicians, so they can exercise their judgment wisely and toward the benefit of the children under diverse circumstances and resource pressures.

If you think dyslexia is caused by some factor X, and if you think you know what X is, then you will probably try to fix X, expecting reading to improve as a result, instead of addressing the reading difficulties directly. This kind of thinking is still very much alive. However, if the trend is away from single causes and toward the recognition that reading skill, and reading failure, is multi-factorial, multi-level, and polygenic, then you are more likely to recognize that assessment and remedial efforts are best focused directly on reading skill and the well-known prerequisites for its development.