An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A Literature Review: Website Design and User Engagement

Renee garett.

1 ElevateU, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Sean D. Young

2 University of California Institute for Prediction Technology, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

3 UCLA Center for Digital Behavior, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Proper design has become a critical element needed to engage website and mobile application users. However, little research has been conducted to define the specific elements used in effective website and mobile application design. We attempt to review and consolidate research on effective design and to define a short list of elements frequently used in research. The design elements mentioned most frequently in the reviewed literature were navigation, graphical representation, organization, content utility, purpose, simplicity, and readability. We discuss how previous studies define and evaluate these seven elements. This review and the resulting short list of design elements may be used to help designers and researchers to operationalize best practices for facilitating and predicting user engagement.

1. INTRODUCTION

Internet usage has increased tremendously and rapidly in the past decade ( “Internet Use Over Time,” 2014 ). Websites have become the most important public communication portal for most, if not all, businesses and organizations. As of 2014, 87% of American adults aged 18 or older are Internet users ( “Internet User Demographics,” 2013 ). Because business-to-consumer interactions mainly occur online, website design is critical in engaging users ( Flavián, Guinalíu, & Gurrea, 2006 ; Lee & Kozar, 2012 ; Petre, Minocha, & Roberts, 2006 ). Poorly designed websites may frustrate users and result in a high “bounce rate”, or people visiting the entrance page without exploring other pages within the site ( Google.com, 2015 ). On the other hand, a well-designed website with high usability has been found to positively influence visitor retention (revisit rates) and purchasing behavior ( Avouris, Tselios, Fidas, & Papachristos, 2003 ; Flavián et al., 2006 ; Lee & Kozar, 2012 ).

Little research, however, has been conducted to define the specific elements that constitute effective website design. One of the key design measures is usability ( International Standardization Organization, 1998 ). The International Standardized Organization (ISO) defines usability as the extent to which users can achieve desired tasks (e.g., access desired information or place a purchase) with effectiveness (completeness and accuracy of the task), efficiency (time spent on the task), and satisfaction (user experience) within a system. However, there is currently no consensus on how to properly operationalize and assess website usability ( Lee & Kozar, 2012 ). For example, Nielson associates usability with learnability, efficiency, memorability, errors, and satisfaction ( Nielsen, 2012 ). Yet, Palmer (2002) postulates that usability is determined by download time, navigation, content, interactivity, and responsiveness. Similar to usability, many other key design elements, such as scannability, readability, and visual aesthetics, have not yet been clearly defined ( Bevan, 1997 ; Brady & Phillips, 2003 ; Kim, Lee, Han, & Lee, 2002 ), and there are no clear guidelines that individuals can follow when designing websites to increase engagement.

This review sought to address that question by identifying and consolidating the key website design elements that influence user engagement according to prior research studies. This review aimed to determine the website design elements that are most commonly shown or suggested to increase user engagement. Based on these findings, we listed and defined a short list of website design elements that best facilitate and predict user engagement. The work is thus an exploratory research providing definitions for these elements of website design and a starting point for future research to reference.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. selection criteria and data extraction.

We searched for articles relating to website design on Google Scholar (scholar.google.com) because Google Scholar consolidates papers across research databases (e.g., Pubmed) and research on design is listed in multiple databases. We used the following combination of keywords: design, usability, and websites. Google Scholar yielded 115,000 total hits. However, due to the large list of studies generated, we decided to only review the top 100 listed research studies for this exploratory study. Our inclusion criteria for the studies was: (1) publication in a peer-reviewed academic journal, (2) publication in English, and (3) publication in or after 2000. Year of publication was chosen as a limiting factor so that we would have enough years of research to identify relevant studies but also have results that relate to similar styles of websites after the year 2000. We included studies that were experimental or theoretical (review papers and commentaries) in nature. Resulting studies represented a diverse range of disciplines, including human-computer interaction, marketing, e-commerce, interface design, cognitive science, and library science. Based on these selection criteria, thirty-five unique studies remained and were included in this review.

2.2. Final Search Term

(design) and (usability) and (websites).

The search terms were kept simple to capture the higher level design/usability papers and allow Google scholar’s ranking method to filter out the most popular studies. This method also allowed studies from a large range of fields to be searched.

2.3. Analysis

The literature review uncovered 20 distinct design elements commonly discussed in research that affect user engagement. They were (1) organization – is the website logically organized, (2) content utility – is the information provided useful or interesting, (3) navigation – is the website easy to navigate, (4) graphical representation – does the website utilize icons, contrasting colors, and multimedia content, (5) purpose – does the website clearly state its purpose (i.e. personal, commercial, or educational), (6) memorable elements – does the website facilitate returning users to navigate the site effectively (e.g., through layout or graphics), (7) valid links – does the website provide valid links, (8) simplicity – is the design of the website simple, (9) impartiality – is the information provided fair and objective, (10) credibility – is the information provided credible, (11) consistency/reliability – is the website consistently designed (i.e., no changes in page layout throughout the site), (12) accuracy – is the information accurate, (13) loading speed – does the website take a long time to load, (14) security/privacy – does the website securely transmit, store, and display personal information/data, (15) interactive – can the user interact with the website (e.g., post comments or receive recommendations for similar purchases), (16) strong user control capabilities– does the website allow individuals to customize their experiences (such as the order of information they access and speed at which they browse the website), (17) readability – is the website easy to read and understand (e.g., no grammatical/spelling errors), (18) efficiency – is the information presented in a way that users can find the information they need quickly, (19) scannability – can users pick out relevant information quickly, and (20) learnability – how steep is the learning curve for using the website. For each of the above, we calculated the proportion of studies mentioning the element. In this review, we provide a threshold value of 30%. We identified elements that were used in at least 30% of the studies and include these elements that are above the threshold on a short list of elements used in research on proper website design. The 30% value was an arbitrary threshold picked that would provide researchers and designers with a guideline list of elements described in research on effective web design. To provide further information on how to apply this list, we present specific details on how each of these elements was discussed in research so that it can be defined and operationalized.

3.1. Popular website design elements ( Table 1 )

Frequency of website design elements used in research (2000–2014)

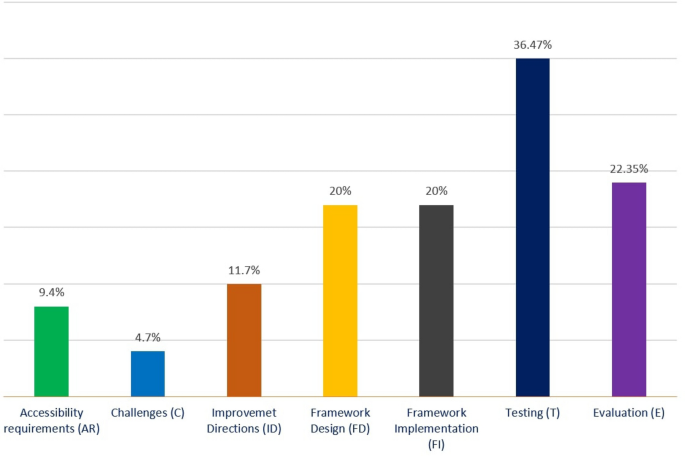

Seven of the website design elements met our threshold requirement for review. Navigation was the most frequently discussed element, mentioned in 22 articles (62.86%). Twenty-one studies (60%) highlighted the importance of graphics. Fifteen studies (42.86%) emphasized good organization. Four other elements also exceeded the threshold level, and they were content utility (n=13, 37.14%), purpose (n=11, 31.43%), simplicity (n=11, 31.43%), and readability (n=11, 31.43%).

Elements below our minimum requirement for review include memorable features (n=5, 14.29%), links (n=10, 28.57%), impartiality (n=1, 2.86%), credibility (n=7, 20%), consistency/reliability (n=8. 22.86%), accuracy (n=5, 14.29%), loading speed (n=10, 28.57%), security/privacy (n=2, 5.71%), interactive features (n=9, 25.71%), strong user control capabilities (n=8, 22.86%), efficiency (n=6, 17.14%), scannability (n=1, 2.86%), and learnability (n=2, 5.71%).

3.2. Defining key design elements for user engagement ( Table 2 )

Definitions of Key Design Elements

In defining and operationalizing each of these elements, the research studies suggested that effective navigation is the presence of salient and consistent menu/navigation bars, aids for navigation (e.g., visible links), search features, and easy access to pages (multiple pathways and limited clicks/backtracking). Engaging graphical presentation entails 1) inclusion of images, 2) proper size and resolution of images, 3) multimedia content, 4) proper color, font, and size of text, 5) use of logos and icons, 6) attractive visual layout, 7) color schemes, and 8) effective use of white space. Optimal organization includes 1) cognitive architecture, 2) logical, understandable, and hierarchical structure, 3) information arrangement and categorization, 4) meaningful labels/headings/titles, and 5) use of keywords. Content utility is determined by 1) sufficient amount of information to attract repeat visitors, 2) arousal/motivation (keeps visitors interested and motivates users to continue exploring the site), 3) content quality, 4) information relevant to the purpose of the site, and 5) perceived utility based on user needs/requirements. The purpose of a website is clear when it 1) establishes a unique and visible brand/identity, 2) addresses visitors’ intended purpose and expectations for visiting the site, and 3) provides information about the organization and/or services. Simplicity is achieved by using 1) simple subject headings, 2) transparency of information (reduce search time), 3) website design optimized for computer screens, 4) uncluttered layout, 5) consistency in design throughout website, 6) ease of using (including first-time users), 7) minimize redundant features, and 8) easily understandable functions. Readability is optimized by content that is 1) easy to read, 2) well-written, 3) grammatically correct, 4) understandable, 5) presented in readable blocks, and 6) reading level appropriate.

4. DISCUSSION

The seven website design elements most often discussed in relation to user engagement in the reviewed studies were navigation (62.86%), graphical representation (60%), organization (42.86%), content utility (37.14%), purpose (31.43%), simplicity (31.43%), and readability (31.43%). These seven elements exceeded our threshold level of 30% representation in the literature and were included into a short list of website design elements to operationalize effective website design. For further analysis, we reviewed how studies defined and evaluated these seven elements. This may allow designers and researchers to determine and follow best practices for facilitating or predicting user engagement.

A remaining challenge is that the definitions of website design elements often overlap. For example, several studies evaluated organization by how well a website incorporates cognitive architecture, logical and hierarchical structure, systematic information arrangement and categorization, meaningful headings and labels, and keywords. However, these features are also crucial in navigation design. Also, the implications of using distinct logos and icons go beyond graphical representation. Logos and icons also establish unique brand/identity for the organization (purpose) and can serve as visual aids for navigation. Future studies are needed to develop distinct and objective measures to assess these elements and how they affect user engagement ( Lee & Kozar, 2012 ).

Given the rapid increase in both mobile technology and social media use, it is surprising that no studies mentioned cross-platform compatibility and social media integration. In 2013, 34% of cellphone owners primarily use their cellphones to access the Internet, and this number continues to grow ( “Mobile Technology Factsheet,” 2013 ). With the rise of different mobile devices, users are also diversifying their web browser use. Internet Explorer (IE) was once the leading web browser. However, in recent years, FireFox, Safari, and Chrome have gained significant traction ( W3schools.com, 2015 ). Website designers and researchers must be mindful of different platforms and browsers to minimize the risk of losing users due to compatibility issues. In addition, roughly 74% of American Internet users use some form of social media ( Duggan, Ellison, Lampe, Lenhart, & Smith, 2015 ), and social media has emerged as an effective platform for organizations to target and interact with users. Integrating social media into website design may increase user engagement by facilitating participation and interactivity.

There are several limitations to the current review. First, due to the large number of studies published in this area and due to this study being exploratory, we selected from the first 100 research publications on Google Scholar search results. Future studies may benefit from defining design to a specific topic, set of years, or other area to limit the number of search results. Second, we did not quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of these website design elements. Additional research can help to better quantify these elements.

It should also be noted that different disciplines and industries have different objectives in designing websites and should thus prioritize different website design elements. For example, online businesses and marketers seek to design websites that optimize brand loyalty, purchase, and profit ( Petre et al., 2006 ). Others, such as academic researchers or healthcare providers, are more likely to prioritize privacy/confidentiality, and content accuracy in building websites ( Horvath, Ecklund, Hunt, Nelson, & Toomey, 2015 ). Ultimately, we advise website designers and researchers to consider the design elements delineated in this review, along with their unique needs, when developing user engagement strategies.

- Arroyo Ernesto, Selker Ted, Wei Willy. Usability tool for analysis of web designs using mouse tracks. Paper presented at the CHI’06 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems.2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Atterer Richard, Wnuk Monika, Schmidt Albrecht. Knowing the user’s every move: user activity tracking for website usability evaluation and implicit interaction. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 15th international conference on World Wide Web.2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Auger Pat. The impact of interactivity and design sophistication on the performance of commercial websites for small businesses. Journal of Small Business Management. 2005; 43 (2):119–137. [ Google Scholar ]

- Avouris Nikolaos, Tselios Nikolaos, Fidas Christos, Papachristos Eleftherios. Advances in Informatics. Springer; 2003. Website evaluation: A usability-based perspective; pp. 217–231. [ Google Scholar ]

- Banati Hema, Bedi Punam, Grover PS. Evaluating web usability from the user’s perspective. Journal of Computer Science. 2006; 2 (4):314. [ Google Scholar ]

- Belanche Daniel, Casaló Luis V, Guinalíu Miguel. Website usability, consumer satisfaction and the intention to use a website: The moderating effect of perceived risk. Journal of retailing and consumer services. 2012; 19 (1):124–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bevan Nigel. Usability issues in web site design. Paper presented at the HCI; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blackmon Marilyn Hughes, Kitajima Muneo, Polson Peter G. Repairing usability problems identified by the cognitive walkthrough for the web. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems.2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blackmon Marilyn Hughes, Polson Peter G, Kitajima Muneo, Lewis Clayton. Cognitive walkthrough for the web. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems.2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Braddy Phillip W, Meade Adam W, Kroustalis Christina M. Online recruiting: The effects of organizational familiarity, website usability, and website attractiveness on viewers’ impressions of organizations. Computers in Human Behavior. 2008; 24 (6):2992–3001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brady Laurie, Phillips Christine. Aesthetics and usability: A look at color and balance. Usability News. 2003; 5 (1) [ Google Scholar ]

- Cyr Dianne, Head Milena, Larios Hector. Colour appeal in website design within and across cultures: A multi-method evaluation. International journal of human-computer studies. 2010; 68 (1):1–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cyr Dianne, Ilsever Joe, Bonanni Carole, Bowes John. Website Design and Culture: An Empirical Investigation. Paper presented at the IWIPS.2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dastidar Surajit Ghosh. Impact of the factors influencing website usability on user satisfaction. 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Angeli Antonella, Sutcliffe Alistair, Hartmann Jan. Interaction, usability and aesthetics: what influences users’ preferences?. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 6th conference on Designing Interactive systems.2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Djamasbi Soussan, Siegel Marisa, Tullis Tom. Generation Y, web design, and eye tracking. International journal of human-computer studies. 2010; 68 (5):307–323. [ Google Scholar ]

- Djonov Emilia. Website hierarchy and the interaction between content organization, webpage and navigation design: A systemic functional hypermedia discourse analysis perspective. Information Design Journal. 2007; 15 (2):144–162. [ Google Scholar ]

- Duggan M, Ellison N, Lampe C, Lenhart A, Smith A. Social Media update 2014. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flavián Carlos, Guinalíu Miguel, Gurrea Raquel. The role played by perceived usability, satisfaction and consumer trust on website loyalty. Information & Management. 2006; 43 (1):1–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- George Carole A. Usability testing and design of a library website: an iterative approach. OCLC Systems & Services: International digital library perspectives. 2005; 21 (3):167–180. [ Google Scholar ]

- Google.com. Bounce Rate. Analyrics Help. 2015 Retrieved 2/11, 2015, from https://support.google.com/analytics/answer/1009409?hl=en .

- Green D, Pearson JM. Development of a web site usability instrument based on ISO 9241-11. Journal of Computer Information Systems. 2006 Fall [ Google Scholar ]

- Horvath Keith J, Ecklund Alexandra M, Hunt Shanda L, Nelson Toben F, Toomey Traci L. Developing Internet-Based Health Interventions: A Guide for Public Health Researchers and Practitioners. J Med Internet Res. 2015; 17 (1):e28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3770. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- International Standardization Organization. ISO 2941-11:1998 Ergonomic requirements for office work with visual display terminals (VDTs) -- Part 11: Guidance on usability: International Standardization Organization (ISO) 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Internet Use Over Time. 2014 Jan 2; Retrieved February 15, 2015, from http://www.pewinternet.org/data-trend/internet-use/internet-use-over-time/

- Internet User Demographics. 2013 Nov 14; Retrieved February 11, 2015, from http://www.pewinternet.org/data-trend/internet-use/latest-stats/

- Kim Jinwoo, Lee Jungwon, Han Kwanghee, Lee Moonkyu. Businesses as Buildings: Metrics for the Architectural Quality of Internet Businesses. Information Systems Research. 2002; 13 (3):239–254. doi: 10.1287/isre.13.3.239.79. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee Younghwa, Kozar Kenneth A. Understanding of website usability: Specifying and measuring constructs and their relationships. Decision Support Systems. 2012; 52 (2):450–463. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lim Sun. The Self-Confrontation Interview: Towards an Enhanced Understanding of Human Factors in Web-based Interaction for Improved Website Usability. J Electron Commerce Res. 2002; 3 (3):162–173. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lowry Paul Benjamin, Spaulding Trent, Wells Taylor, Moody Greg, Moffit Kevin, Madariaga Sebastian. A theoretical model and empirical results linking website interactivity and usability satisfaction. Paper presented at the System Sciences, 2006. HICSS’06. Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on.2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maurer Steven D, Liu Yuping. Developing effective e-recruiting websites: Insights for managers from marketers. Business Horizons. 2007; 50 (4):305–314. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mobile Technology Fact Sheet. 2013 Dec 27; Retrieved August 5, 2015, from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/mobile-technology-fact-sheet/

- Nielsen Jakob. Usability 101: introduction to Usability. 2012 Retrieved 2/11, 2015, from http://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/

- Palmer Jonathan W. Web Site Usability, Design, and Performance Metrics. Information Systems Research. 2002; 13 (2):151–167. doi: 10.1287/isre.13.2.151.88. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Petre Marian, Minocha Shailey, Roberts Dave. Usability beyond the website: an empirically-grounded e-commerce evaluation instrument for the total customer experience. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2006; 25 (2):189–203. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petrie Helen, Hamilton Fraser, King Neil. Tension, what tension?: Website accessibility and visual design. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2004 international cross-disciplinary workshop on Web accessibility (W4A).2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Raward Roslyn. Academic library website design principles: development of a checklist. Australian Academic & Research Libraries. 2001; 32 (2):123–136. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosen Deborah E, Purinton Elizabeth. Website design: Viewing the web as a cognitive landscape. Journal of Business Research. 2004; 57 (7):787–794. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shneiderman Ben, Hochheiser Harry. Universal usability as a stimulus to advanced interface design. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2001; 20 (5):367–376. [ Google Scholar ]

- Song Jaeki, Zahedi Fatemeh “Mariam”. A theoretical approach to web design in e-commerce: a belief reinforcement model. Management Science. 2005; 51 (8):1219–1235. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sutcliffe Alistair. Interactive systems: design, specification, and verification. Springer; 2001. Heuristic evaluation of website attractiveness and usability; pp. 183–198. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tan Gek Woo, Wei Kwok Kee. An empirical study of Web browsing behaviour: Towards an effective Website design. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 2007; 5 (4):261–271. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarafdar Monideepa, Zhang Jie. Determinants of reach and loyalty-a study of Website performance and implications for Website design. Journal of Computer Information Systems. 2008; 48 (2):16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson Lori Foster, Braddy Phillip W, Wuensch Karl L. E-recruitment and the benefits of organizational web appeal. Computers in Human Behavior. 2008; 24 (5):2384–2398. [ Google Scholar ]

- W3schools.com. Browser Statistics and Trends. Retrieved 1/15, 2015, from http://www.w3schools.com/browsers/browsers_stats.asp .

- Williamson Ian O, Lepak David P, King James. The effect of company recruitment web site orientation on individuals’ perceptions of organizational attractiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2003; 63 (2):242–263. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Ping, Small Ruth V, Von Dran Gisela M, Barcellos Silvia. A two factor theory for website design. Paper presented at the System Sciences, 2000. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Hawaii International Conference on.2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Ping, Von Dran Gisela M. Satisfiers and dissatisfiers: A two-factor model for website design and evaluation. Journal of the American society for information science. 2000; 51 (14):1253–1268. [ Google Scholar ]

Web design — Past, present and future

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

What is Web Design?

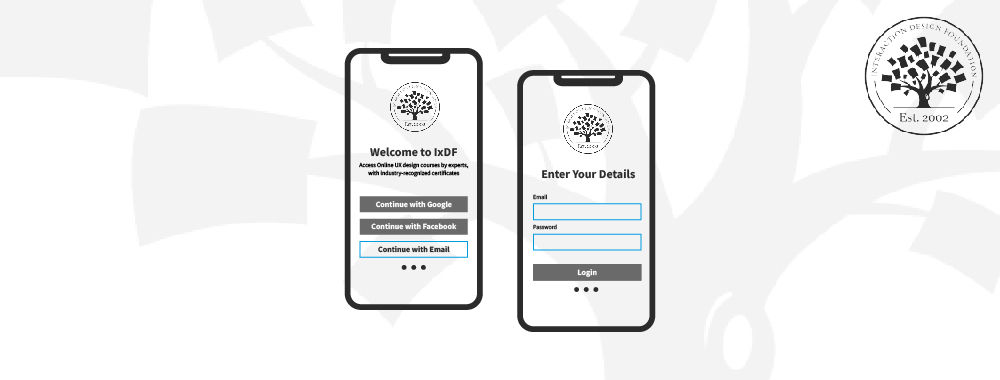

Web design refers to the design of websites. It usually refers to the user experience aspects of website development rather than software development. Web design used to be focused on designing websites for desktop browsers; however, since the mid-2010s, design for mobile and tablet browsers has become ever-increasingly important.

- Transcript loading…

A web designer works on a website's appearance, layout, and, in some cases, content .

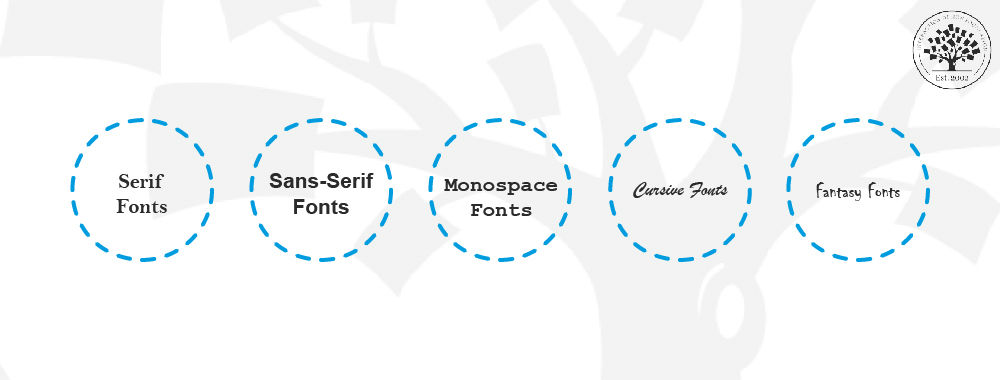

Appearance relates to the colors, typography, and images used.

Layout refers to how information is structured and categorized. A good web design is easy to use, aesthetically pleasing, and suits the user group and brand of the website.

A well-designed website is simple and communicates clearly to avoid confusing users. It wins and fosters the target audience's trust, removing as many potential points of user frustration as possible.

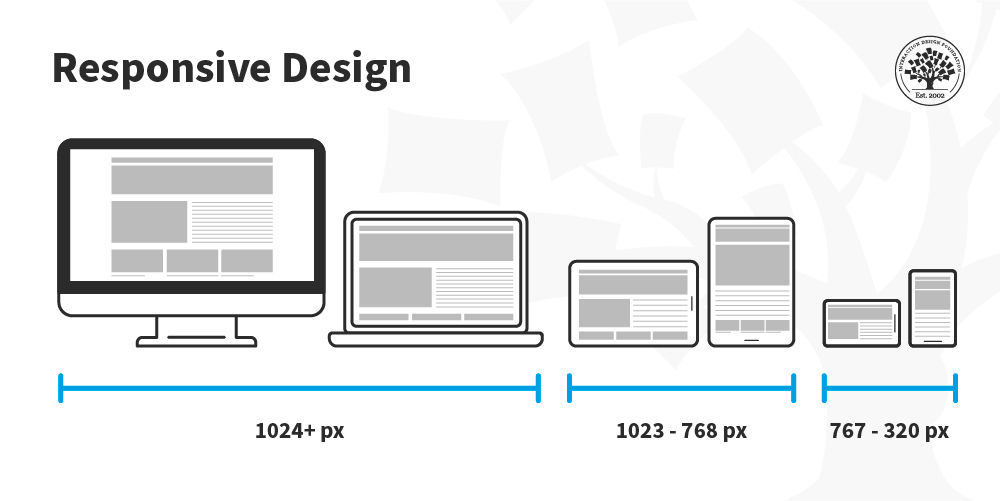

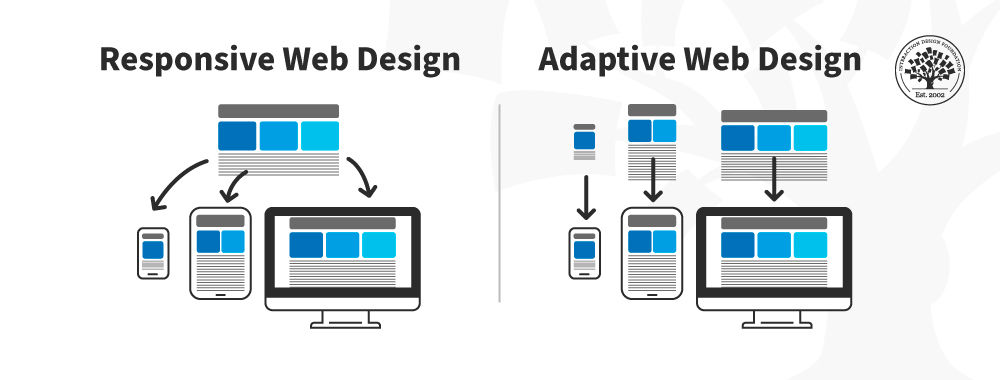

Responsive and adaptive design are two common ways to design websites that work well on both desktop and mobile.

What is Responsive Web Design?

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

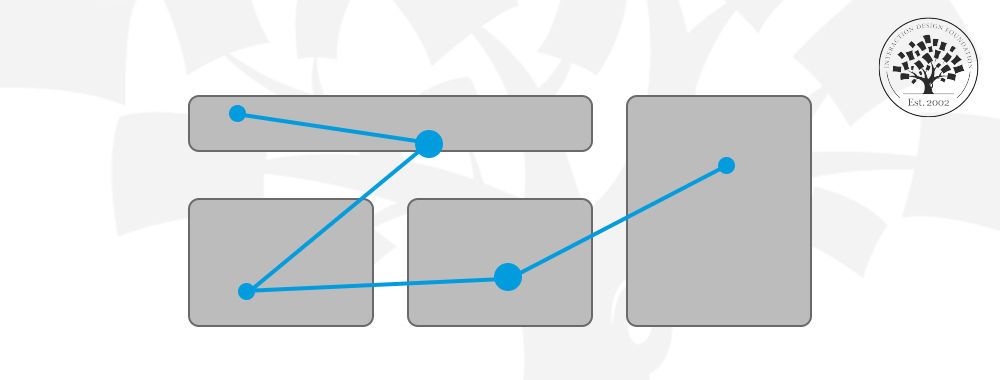

Responsive Web Design (a.k.a. "Responsive" or "Responsive Design") is an approach to designing web content that appears regardless of the resolution governed by the device. It’s typically accomplished with viewport breakpoints (resolution cut-offs for when content scales to that view). The viewports should adjust logically on tablets, phones, and desktops of any resolution.

In responsive design, you can define rules for how the content flows and how the layout changes based on the size range of the screen.

Responsive designs respond to changes in browser width by adjusting the placement of design elements to fit in the available space. If you open a responsive site on the desktop and change the browser window's size, the content will dynamically rearrange itself to fit the browser window. The site checks for the available space on mobile phones and then presents itself in the ideal arrangement.

Best Practices and Considerations for Responsive Design

With responsive design, you design for flexibility in every aspect—images, text and layouts. So, you should:

Take the mobile-first approach —start the product design process for mobile devices first instead of desktop devices.

Create fluid grids and images .

Prioritize the use of Scalable Vector Graphics (SVGs). These are an XML-based file format for 2D graphics, which supports interactivity and animations.

Include three or more breakpoints (layouts for three or more devices).

Prioritize and hide content to suit users’ contexts . Check your visual hierarchy and use progressive disclosure and navigation drawers to give users needed items first. Keep nonessential items (nice-to-haves) secondary.

Aim for minimalism .

Apply design patterns to maximize ease of use for users in their contexts and quicken their familiarity: e.g., the column drop pattern fits content to many screen types.

Aim for accessibility .

What is Adaptive Web Design?

Adaptive design is similar to responsive design—both are approaches for designing across a diverse range of devices; the difference lies in how the tailoring of the content takes place.

In the case of responsive design, all content and functionality are the same for every device. Therefore, a large-screen desktop and smartphone browser displays the same content. The only difference is in the layout of the content.

In this video, CEO of Experience Dynamics, Frank Spillers, explains the advantages of adaptive design through a real-life scenario.

Adaptive design takes responsiveness up a notch. While responsive design focuses on just the device, adaptive design considers both the device and the user’s context. This means that you can design context-aware experiences —a web application's content and functionality can look and behave very differently from the version served on the desktop.

For example, if an adaptive design detects low bandwidth or the user is on a mobile device instead of a desktop device, it might not load a large image (e.g., an infographic). Instead, it might show a smaller summary version of the infographic.

Another example could be to detect if the device is an older phone with a smaller screen. The website can show larger call-to-action buttons than usual.

Accessibility for Web Design

“The power of the Web is in its universality. Access by everyone regardless of disability is an essential aspect.” —Tim Berners-Lee, W3C Director and inventor of the World Wide Web

Web accessibility means making websites and technology usable for people with varying abilities and disabilities. An accessible website ensures that all users, regardless of their abilities, can perceive, understand, navigate, and interact with the web.

In this video, William Hudson, CEO of Syntagm, discusses the importance of accessibility and provides tips on how to make websites more accessible.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) lists a few basic considerations for web accessibility:

Provide sufficient contrast between foreground and background . For example, black or dark gray text on white is easier to read than gray text on a lighter shade of gray. Use color contrast checkers to test the contrast ratio between your text and background colors to ensure people can easily see your content.

Don’t use color alone to convey information . For example, use underlines for hyperlinked text in addition to color so that people with colorblindness can still recognize a link, even if they can’t differentiate between the hyperlink and regular text.

Ensure that interactive elements are easy to identify . For example, show different styles for links when the user hovers over them or focuses using the keyboard.

Provide clear and consistent navigation options . Use consistent layouts and naming conventions for menu items to prevent confusion. For example, if you use breadcrumbs, ensure they are consistently in the same position across different web pages.

Ensure that form elements include clearly associated labels . For example, place form labels to the left of a form field (for left-to-right languages) instead of above or inside the input field to reduce errors.

Provide easily identifiable feedback . If feedback (such as error messages) is in fine print or a specific color, people with lower vision or colorblindness will find it harder to use the website. Make sure such feedback is clear and easy to identify. For example, you can offer options to navigate to different errors.

Use headings and spacing to group related content. Good visual hierarchy (through typography, whitespace and grid layouts) makes it easy to scan content.

Create designs for different viewport sizes . Ensure your content scales up (to larger devices) and down (to fit smaller screens). Design responsive websites and test them thoroughly.

Include image and media alternatives in your design . Provide transcripts for audio and video content and text alternatives for images. Ensure the alternative text on images conveys meaning and doesn’t simply describe the image. If you use PDFs, make sure they, too, are accessible.

Provide controls for content that starts automatically . Allow users to pause animations or video content that plays automatically.

These practices not only make a website easier to access for people with disabilities but also for usability in general for everyone.

Learn More about Web Design

Learn how to apply the principles of user-centered design in the course Web Design for Usability .

For more on adaptive and responsive design, take the Mobile UX Design: The Beginner's Guide course.

See W3C’s Designing for Web Accessibility for practical tips on implementing accessibility.

Questions related to Web Design

Designing a web page involves creating a visual layout and aesthetic.

Start by defining the purpose and target audience of your page.

Understand the type of content and what actions the user will perform on the web page.

Sketch ideas and create wireframes or mockups of the layout.

Select a color scheme, typography, and imagery that align with your brand identity.

Use design software like Figma or Sketch to create the design.

Finally, gather feedback and make necessary revisions before handing off the development design.

In each step, remember to keep the user experience and accessibility considerations foremost. Here’s why Accessibility Matters:

The salary of web designers varies widely based on experience, location, and skill set. As of our last update, the average salary for a Web Designer in the United States is reported to be approximately $52,691 per year, according to Glassdoor. However, this figure can range from around $37,000 for entry-level positions to over $73,000 for experienced designers. It is crucial to mention that salaries may differ significantly by region, company size, and individual qualifications. For the most up-to-date and region-specific salary information, visit Glassdoor .

To become a web designer, you should start by understanding design principles, usability best practices, color theory, and typography. Next, learn the essential tools like Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator, and Sketch. Familiarize yourself with web design languages such as HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. It's important to create a portfolio of your top work to impress potential employers. Additionally, consider taking online courses to enhance your knowledge and skills.

Interaction Design Foundation offers a comprehensive UI Designer Learning Path that can help you become proficient in user interface design, a key component of web design. Lastly, continuously practice web design, seek feedback, and stay up-to-date with the latest trends and technologies.

The role of a web designer entails the task of designing a website's visual design and layout of a website, which includes the site's appearance, structure, navigation, and accessibility. They select color palettes, create graphics, choose fonts, and layout content to create an aesthetically pleasing, user-friendly, and accessible design. Web designers also work closely with web developers to verify that the design is technically feasible and implemented correctly. They may be involved in user experience design, ensuring the website is intuitive, accessible, and easy to use. Additionally, web designers must be aware of designer bias, as discussed in this video.

Ultimately, a web designer's goal is to create a visually appealing, functional, accessible, and positive user experience.

Web design and coding are closely related, but they are not the same. Web design involves creating the visual elements and layout of a website, while coding involves translating these designs into a functional website using programming languages like HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. Typically, dedicated web developers translate the designs to code. Several design tools can also export code directly.

Although some web designers also have coding skills, it is not a requirement for all web design roles. However, having a basic understanding of coding can be beneficial for a web designer as it helps in creating designs that are both aesthetically pleasing and technically feasible.

Responsive web design guarantees that a website adapts its format to fit any screen size across different devices and screen sizes, from desktops to tablets to mobile phones. It includes the site to the device's resolution, supports device switching and increases accessibility and SEO-friendliness.

As Frank Spillers, CEO of Experience Dynamics mentions in this video, responsive design is a default, and not an optional feature because everyone expects mobile optimization. This approach is vital for Google's algorithm, which prioritizes responsive sites.

To learn web design, start by understanding its fundamental principles, such as color theory, typography, and layout. Practice designing websites, get feedback, and iterate on your designs. Enhance your skills by taking online courses, attending workshops, and reading articles.

Consider the Interaction Design Foundation's comprehensive UI Designer learning path for essential skills and knowledge. If you're interested in expanding your skill set, consider exploring UX design as an alternative. The article " How to Change Your Career from Web Design to UX Design " on the IxDF Blog offers insightful guidance. Start your journey today!

Absolutely, web design is a rewarding career choice. It offers creative freedom, a chance to solve real-world problems, and a growing demand for skilled professionals. With the digital world expanding, businesses seek qualified web designers to create user-friendly and visually appealing websites. Additionally, web design offers diverse job opportunities, competitive salaries, and the option to work freelance or in-house. Continuously evolving technology ensures that web design remains a dynamic and future-proof career.

Web design and front-end development are related but distinct disciplines. Web design involves creating the visual layout and aesthetics of a website, focusing on user experience, graphics, and overall look. Front-end development, on the other hand, involves implementing the design into a functional website using coding languages like HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. While there is overlap, and many professionals have skills in both areas, web design is more creative, and front-end development is more technical.

In this Master Class webinar, Szymon Adamiak of Hype4 shares his top tips for smooth designer-developer relationships, based on years of working as a front-end developer with teams of designers on various projects.

Yes and no! A web page is a type of user interface—it is the touchpoint between a business and the user. People interact with web pages. They may fill out a form, or simply navigate from one page to another. A web designer must also be familiar with UI design best practices to ensure the website is usable.

That said, in practice, the term UI is most often associated with applications. Unlike web pages, which tend to be more static and are closely related to branding and communication, applications (on both web and mobile) allow users to manipulate data and perform tasks..

UI design, as explained in this video above, involves visualizing and creating the interface of an application, focusing on aesthetics, user experience, and overall look. To learn more, check our UI Design Learning Path .

A modal in web design is a secondary window that appears above the primary webpage, focusing on specific content and pausing interaction with the main page. It's a common user interface design pattern used to solve interface problems by showing contextual information when they matter.

The video above explains the importance of designing good UI patterns to enhance user experience and reduce usability issues. Modals are crucial for successful user-centered design and product development like other UI patterns.

In web design, CMS refers to a Content Management System. It is software used to create and manage digital content.

The video above implies that the content, including those managed by a CMS, is crucial in every stage of the user experience, from setup to engagement. The top 10 CMS in 2023 are the following:

Magento (more focused on e-commerce)

Squarespace

Shopify (more focused on e-commerce)

The popularity and usage of CMS platforms can vary over time, and there may be new players in the market since our last update.

Literature on Web Design

Here’s the entire UX literature on Web Design by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Web Design

Take a deep dive into Web Design with our course Mobile UX Design: The Beginner's Guide .

In the “ Build Your Portfolio” project, you’ll find a series of practical exercises that will give you first-hand experience with the methods we cover. You will build on your project in each lesson so once you have completed the course you will have a thorough case study for your portfolio.

Mobile User Experience Design: Introduction , has been built on evidence-based research and practice. It is taught by the CEO of ExperienceDynamics.com, Frank Spillers, author, speaker and internationally respected Senior Usability practitioner.

All open-source articles on Web Design

Repetition, pattern, and rhythm.

- 1.2k shares

Adaptive vs. Responsive Design

- 3 years ago

How to Change Your Career from Web Design to UX Design

- 1.1k shares

Emphasis: Setting up the focal point of your design

- 8 years ago

Accessibility: Usability for all

- 2 years ago

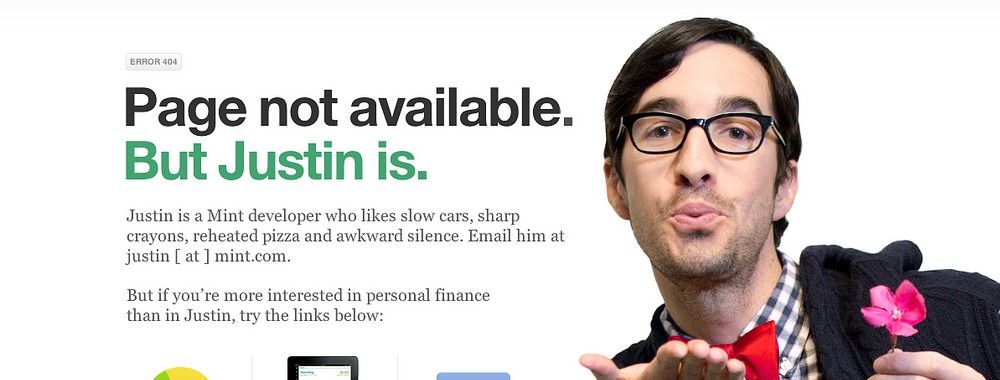

How to Design Great 404 Error Pages

- 4 years ago

Emotion and website design

Parallax Web Design - The Earth May Not Move for Us But the Web Can

Fitts’ Law: Tracking users’ clicks

Video and Web Design

- 7 years ago

The Best UX Portfolio Website Builders in 2024

10 of Our Favorite Login Screen Examples

Web Fonts: Definition and 10 Recommendations

What is Eye Tracking in UX?

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

web development Recently Published Documents

Total documents.

- Latest Documents

- Most Cited Documents

- Contributed Authors

- Related Sources

- Related Keywords

Website Developmemt Technologies: A Review

Abstract: Service Science is that the basis of knowledge system and net services that judge to the provider/client model. This paper developments a technique which will be utilized in the event of net services like websites, net applications and eCommerce. The goal is to development a technique that may add structure to a extremely unstructured drawback to help within the development and success of net services. The new methodology projected are going to be referred to as {the net|the online|the net} Development Life Cycle (WDLC) and tailored from existing methodologies and applied to the context of web development. This paper can define well the projected phases of the WDLC. Keywords: Web Development, Application Development, Technologies, eCommerce.

Analysis of Russian Segment of the Web Development Market Operating Online on Upwork

The Russian segment of the web services market in the online environment, on the platform of the Upwork freelance exchange, is considered, its key characteristics, the composition of participants, development trends are highlighted, and the market structure is identified. It is found that despite the low barriers to entry, the web development market is very stable, since the composition of entrenched firms that have been operating for more than six years remains. The pricing policy of most Russian companies indicates that they work in the middle price segment and have low budgets, which is due to the specifics of the foreign market and high competition.

Farming Assistant Web Services: Agricultor

Abstract: Our farming assistant web services provides assistance to new as well as establish farmers to get the solutions to dayto-day problems faced in the field. A farmer gets to connect with other farmers throughout India to get more information about a particular crop which is popular in other states. Keywords: Farmers, Assistance, Web Development

Tradução de ementas e histórico escolar para o inglês: contribuição para participação de discentes do curso técnico em informática para internet integrado ao ensino médio em programas de mobilidade acadêmica / Translation of summary and school records into english: contribution to the participation of high school with associate technical degree on web development students in academic mobility programs

Coded websites vs wordpress websites.

This document gives multiple instructions related to web developers using older as well as newer technology. Websites are being created using newer technologies like wordpress whereas on the other hand many people prefer making websites using the traditional way. This document will clear the doubt whether an individual should use wordpress websites or coded websites according to the users convenience. The Responsiveness of the websites, the use of CMS nowadays, more and more up gradation of technologies with SEO, themes, templates, etc. make things like web development much much easier. The aesthetics, the culture, the expressions, the features all together add up in order make the designing and development a lot more efficient and effective. Digital Marketing has a tremendous growth over the last two years and yet shows no signs of stopping, is closely related with the web development environment. Nowadays all businesses are going online due to which the impact of web development has become such that it has become an integral part of any online business.

Cognitive disabilities and web accessibility: a survey into the Brazilian web development community

Cognitive disabilities include a diversity of conditions related to cognitive functions, such as reading, understanding, learning, solving problems, memorization and speaking. They differ largely from each other, making them a heterogeneous complex set of disabilities. Although the awareness about cognitive disabilities has been increasing in the last few years, it is still less than necessary compared to other disabilities. The need for an investigation about this issue is part of the agenda of the Challenge 2 (Accessibility and Digital Inclusion) from GranDIHC-Br. This paper describes the results of an online exploratory survey conducted with 105 web development professionals from different sectors to understand their knowledge and barriers regarding accessibility for people with cognitive disabilities. The results evidenced three biases that potentially prevent those professionals from approaching cogni-tive disabilities: strong organizational barriers; difficulty to understand user needs related to cognitive disabilities; a knowledge gap about web accessibility principles and guidelines. Our results confirmed that web development professionals are unaware about cognitive disabilities mostly by a lack of knowledge about them, even if they understand web accessibility in a technical level. Therefore, we suggest that applied research studies focus on how to fill this knowledge gap before providing tools, artifacts or frameworks.

PERANCANGAN WEB RESPONSIVE UNTUK SISTEM INFORMASI OBAT-OBATAN

A good information system must not only be neat, effective, and resilient, but also must be user friendly and up to date. In a sense, it is able to be applied to various types of electronic devices, easily accessible at any whereand time (real time), and can be modified according to user needs in a relatively easy and simple way. Information systems are now needed by various parties, especially in the field of administration and sale of medicines for Cut Nyak Dhien Hospital. During this time, recording in books has been very ineffective and caused many problems, such as difficulty in accessing old data, asa well as the information obtained was not real time. To solve it, this research raises the theme of the appropriate information system design for the hospital concerned, by utilizing CSS Bootstrap framework and research methodology for web development, namely Web Development Life Cycle. This research resulted in a responsive system by providing easy access through desktop computers, tablets, and smartphones so that it would help the hospital in the data processing process in real time.

Web Development and performance comparison of Web Development Technologies in Node.js and Python

“tom had us all doing front-end web development”: a nostalgic (re)imagining of myspace, assessment of site classifications according to layout type in web development, export citation format, share document.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Writing Survey Questions

Perhaps the most important part of the survey process is the creation of questions that accurately measure the opinions, experiences and behaviors of the public. Accurate random sampling will be wasted if the information gathered is built on a shaky foundation of ambiguous or biased questions. Creating good measures involves both writing good questions and organizing them to form the questionnaire.

Questionnaire design is a multistage process that requires attention to many details at once. Designing the questionnaire is complicated because surveys can ask about topics in varying degrees of detail, questions can be asked in different ways, and questions asked earlier in a survey may influence how people respond to later questions. Researchers are also often interested in measuring change over time and therefore must be attentive to how opinions or behaviors have been measured in prior surveys.

Surveyors may conduct pilot tests or focus groups in the early stages of questionnaire development in order to better understand how people think about an issue or comprehend a question. Pretesting a survey is an essential step in the questionnaire design process to evaluate how people respond to the overall questionnaire and specific questions, especially when questions are being introduced for the first time.

For many years, surveyors approached questionnaire design as an art, but substantial research over the past forty years has demonstrated that there is a lot of science involved in crafting a good survey questionnaire. Here, we discuss the pitfalls and best practices of designing questionnaires.

Question development

There are several steps involved in developing a survey questionnaire. The first is identifying what topics will be covered in the survey. For Pew Research Center surveys, this involves thinking about what is happening in our nation and the world and what will be relevant to the public, policymakers and the media. We also track opinion on a variety of issues over time so we often ensure that we update these trends on a regular basis to better understand whether people’s opinions are changing.

At Pew Research Center, questionnaire development is a collaborative and iterative process where staff meet to discuss drafts of the questionnaire several times over the course of its development. We frequently test new survey questions ahead of time through qualitative research methods such as focus groups , cognitive interviews, pretesting (often using an online, opt-in sample ), or a combination of these approaches. Researchers use insights from this testing to refine questions before they are asked in a production survey, such as on the ATP.

Measuring change over time

Many surveyors want to track changes over time in people’s attitudes, opinions and behaviors. To measure change, questions are asked at two or more points in time. A cross-sectional design surveys different people in the same population at multiple points in time. A panel, such as the ATP, surveys the same people over time. However, it is common for the set of people in survey panels to change over time as new panelists are added and some prior panelists drop out. Many of the questions in Pew Research Center surveys have been asked in prior polls. Asking the same questions at different points in time allows us to report on changes in the overall views of the general public (or a subset of the public, such as registered voters, men or Black Americans), or what we call “trending the data”.

When measuring change over time, it is important to use the same question wording and to be sensitive to where the question is asked in the questionnaire to maintain a similar context as when the question was asked previously (see question wording and question order for further information). All of our survey reports include a topline questionnaire that provides the exact question wording and sequencing, along with results from the current survey and previous surveys in which we asked the question.

The Center’s transition from conducting U.S. surveys by live telephone interviewing to an online panel (around 2014 to 2020) complicated some opinion trends, but not others. Opinion trends that ask about sensitive topics (e.g., personal finances or attending religious services ) or that elicited volunteered answers (e.g., “neither” or “don’t know”) over the phone tended to show larger differences than other trends when shifting from phone polls to the online ATP. The Center adopted several strategies for coping with changes to data trends that may be related to this change in methodology. If there is evidence suggesting that a change in a trend stems from switching from phone to online measurement, Center reports flag that possibility for readers to try to head off confusion or erroneous conclusions.

Open- and closed-ended questions

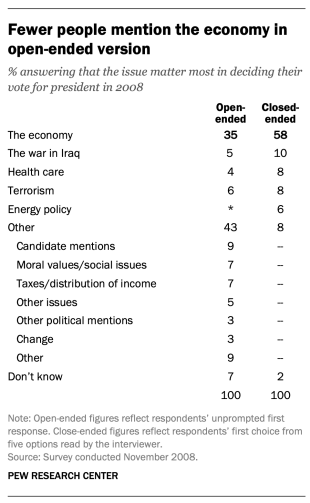

One of the most significant decisions that can affect how people answer questions is whether the question is posed as an open-ended question, where respondents provide a response in their own words, or a closed-ended question, where they are asked to choose from a list of answer choices.

For example, in a poll conducted after the 2008 presidential election, people responded very differently to two versions of the question: “What one issue mattered most to you in deciding how you voted for president?” One was closed-ended and the other open-ended. In the closed-ended version, respondents were provided five options and could volunteer an option not on the list.

When explicitly offered the economy as a response, more than half of respondents (58%) chose this answer; only 35% of those who responded to the open-ended version volunteered the economy. Moreover, among those asked the closed-ended version, fewer than one-in-ten (8%) provided a response other than the five they were read. By contrast, fully 43% of those asked the open-ended version provided a response not listed in the closed-ended version of the question. All of the other issues were chosen at least slightly more often when explicitly offered in the closed-ended version than in the open-ended version. (Also see “High Marks for the Campaign, a High Bar for Obama” for more information.)

Researchers will sometimes conduct a pilot study using open-ended questions to discover which answers are most common. They will then develop closed-ended questions based off that pilot study that include the most common responses as answer choices. In this way, the questions may better reflect what the public is thinking, how they view a particular issue, or bring certain issues to light that the researchers may not have been aware of.

When asking closed-ended questions, the choice of options provided, how each option is described, the number of response options offered, and the order in which options are read can all influence how people respond. One example of the impact of how categories are defined can be found in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in January 2002. When half of the sample was asked whether it was “more important for President Bush to focus on domestic policy or foreign policy,” 52% chose domestic policy while only 34% said foreign policy. When the category “foreign policy” was narrowed to a specific aspect – “the war on terrorism” – far more people chose it; only 33% chose domestic policy while 52% chose the war on terrorism.

In most circumstances, the number of answer choices should be kept to a relatively small number – just four or perhaps five at most – especially in telephone surveys. Psychological research indicates that people have a hard time keeping more than this number of choices in mind at one time. When the question is asking about an objective fact and/or demographics, such as the religious affiliation of the respondent, more categories can be used. In fact, they are encouraged to ensure inclusivity. For example, Pew Research Center’s standard religion questions include more than 12 different categories, beginning with the most common affiliations (Protestant and Catholic). Most respondents have no trouble with this question because they can expect to see their religious group within that list in a self-administered survey.

In addition to the number and choice of response options offered, the order of answer categories can influence how people respond to closed-ended questions. Research suggests that in telephone surveys respondents more frequently choose items heard later in a list (a “recency effect”), and in self-administered surveys, they tend to choose items at the top of the list (a “primacy” effect).

Because of concerns about the effects of category order on responses to closed-ended questions, many sets of response options in Pew Research Center’s surveys are programmed to be randomized to ensure that the options are not asked in the same order for each respondent. Rotating or randomizing means that questions or items in a list are not asked in the same order to each respondent. Answers to questions are sometimes affected by questions that precede them. By presenting questions in a different order to each respondent, we ensure that each question gets asked in the same context as every other question the same number of times (e.g., first, last or any position in between). This does not eliminate the potential impact of previous questions on the current question, but it does ensure that this bias is spread randomly across all of the questions or items in the list. For instance, in the example discussed above about what issue mattered most in people’s vote, the order of the five issues in the closed-ended version of the question was randomized so that no one issue appeared early or late in the list for all respondents. Randomization of response items does not eliminate order effects, but it does ensure that this type of bias is spread randomly.

Questions with ordinal response categories – those with an underlying order (e.g., excellent, good, only fair, poor OR very favorable, mostly favorable, mostly unfavorable, very unfavorable) – are generally not randomized because the order of the categories conveys important information to help respondents answer the question. Generally, these types of scales should be presented in order so respondents can easily place their responses along the continuum, but the order can be reversed for some respondents. For example, in one of Pew Research Center’s questions about abortion, half of the sample is asked whether abortion should be “legal in all cases, legal in most cases, illegal in most cases, illegal in all cases,” while the other half of the sample is asked the same question with the response categories read in reverse order, starting with “illegal in all cases.” Again, reversing the order does not eliminate the recency effect but distributes it randomly across the population.

Question wording

The choice of words and phrases in a question is critical in expressing the meaning and intent of the question to the respondent and ensuring that all respondents interpret the question the same way. Even small wording differences can substantially affect the answers people provide.

[View more Methods 101 Videos ]

An example of a wording difference that had a significant impact on responses comes from a January 2003 Pew Research Center survey. When people were asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule,” 68% said they favored military action while 25% said they opposed military action. However, when asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule even if it meant that U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties, ” responses were dramatically different; only 43% said they favored military action, while 48% said they opposed it. The introduction of U.S. casualties altered the context of the question and influenced whether people favored or opposed military action in Iraq.

There has been a substantial amount of research to gauge the impact of different ways of asking questions and how to minimize differences in the way respondents interpret what is being asked. The issues related to question wording are more numerous than can be treated adequately in this short space, but below are a few of the important things to consider:

First, it is important to ask questions that are clear and specific and that each respondent will be able to answer. If a question is open-ended, it should be evident to respondents that they can answer in their own words and what type of response they should provide (an issue or problem, a month, number of days, etc.). Closed-ended questions should include all reasonable responses (i.e., the list of options is exhaustive) and the response categories should not overlap (i.e., response options should be mutually exclusive). Further, it is important to discern when it is best to use forced-choice close-ended questions (often denoted with a radio button in online surveys) versus “select-all-that-apply” lists (or check-all boxes). A 2019 Center study found that forced-choice questions tend to yield more accurate responses, especially for sensitive questions. Based on that research, the Center generally avoids using select-all-that-apply questions.

It is also important to ask only one question at a time. Questions that ask respondents to evaluate more than one concept (known as double-barreled questions) – such as “How much confidence do you have in President Obama to handle domestic and foreign policy?” – are difficult for respondents to answer and often lead to responses that are difficult to interpret. In this example, it would be more effective to ask two separate questions, one about domestic policy and another about foreign policy.

In general, questions that use simple and concrete language are more easily understood by respondents. It is especially important to consider the education level of the survey population when thinking about how easy it will be for respondents to interpret and answer a question. Double negatives (e.g., do you favor or oppose not allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry) or unfamiliar abbreviations or jargon (e.g., ANWR instead of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) can result in respondent confusion and should be avoided.

Similarly, it is important to consider whether certain words may be viewed as biased or potentially offensive to some respondents, as well as the emotional reaction that some words may provoke. For example, in a 2005 Pew Research Center survey, 51% of respondents said they favored “making it legal for doctors to give terminally ill patients the means to end their lives,” but only 44% said they favored “making it legal for doctors to assist terminally ill patients in committing suicide.” Although both versions of the question are asking about the same thing, the reaction of respondents was different. In another example, respondents have reacted differently to questions using the word “welfare” as opposed to the more generic “assistance to the poor.” Several experiments have shown that there is much greater public support for expanding “assistance to the poor” than for expanding “welfare.”

We often write two versions of a question and ask half of the survey sample one version of the question and the other half the second version. Thus, we say we have two forms of the questionnaire. Respondents are assigned randomly to receive either form, so we can assume that the two groups of respondents are essentially identical. On questions where two versions are used, significant differences in the answers between the two forms tell us that the difference is a result of the way we worded the two versions.

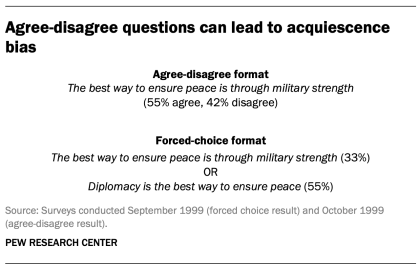

One of the most common formats used in survey questions is the “agree-disagree” format. In this type of question, respondents are asked whether they agree or disagree with a particular statement. Research has shown that, compared with the better educated and better informed, less educated and less informed respondents have a greater tendency to agree with such statements. This is sometimes called an “acquiescence bias” (since some kinds of respondents are more likely to acquiesce to the assertion than are others). This behavior is even more pronounced when there’s an interviewer present, rather than when the survey is self-administered. A better practice is to offer respondents a choice between alternative statements. A Pew Research Center experiment with one of its routinely asked values questions illustrates the difference that question format can make. Not only does the forced choice format yield a very different result overall from the agree-disagree format, but the pattern of answers between respondents with more or less formal education also tends to be very different.

One other challenge in developing questionnaires is what is called “social desirability bias.” People have a natural tendency to want to be accepted and liked, and this may lead people to provide inaccurate answers to questions that deal with sensitive subjects. Research has shown that respondents understate alcohol and drug use, tax evasion and racial bias. They also may overstate church attendance, charitable contributions and the likelihood that they will vote in an election. Researchers attempt to account for this potential bias in crafting questions about these topics. For instance, when Pew Research Center surveys ask about past voting behavior, it is important to note that circumstances may have prevented the respondent from voting: “In the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, did things come up that kept you from voting, or did you happen to vote?” The choice of response options can also make it easier for people to be honest. For example, a question about church attendance might include three of six response options that indicate infrequent attendance. Research has also shown that social desirability bias can be greater when an interviewer is present (e.g., telephone and face-to-face surveys) than when respondents complete the survey themselves (e.g., paper and web surveys).

Lastly, because slight modifications in question wording can affect responses, identical question wording should be used when the intention is to compare results to those from earlier surveys. Similarly, because question wording and responses can vary based on the mode used to survey respondents, researchers should carefully evaluate the likely effects on trend measurements if a different survey mode will be used to assess change in opinion over time.

Question order

Once the survey questions are developed, particular attention should be paid to how they are ordered in the questionnaire. Surveyors must be attentive to how questions early in a questionnaire may have unintended effects on how respondents answer subsequent questions. Researchers have demonstrated that the order in which questions are asked can influence how people respond; earlier questions can unintentionally provide context for the questions that follow (these effects are called “order effects”).

One kind of order effect can be seen in responses to open-ended questions. Pew Research Center surveys generally ask open-ended questions about national problems, opinions about leaders and similar topics near the beginning of the questionnaire. If closed-ended questions that relate to the topic are placed before the open-ended question, respondents are much more likely to mention concepts or considerations raised in those earlier questions when responding to the open-ended question.

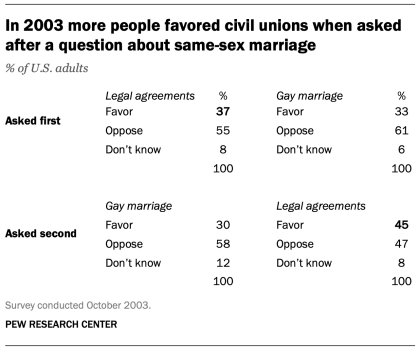

For closed-ended opinion questions, there are two main types of order effects: contrast effects ( where the order results in greater differences in responses), and assimilation effects (where responses are more similar as a result of their order).

An example of a contrast effect can be seen in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in October 2003, a dozen years before same-sex marriage was legalized in the U.S. That poll found that people were more likely to favor allowing gays and lesbians to enter into legal agreements that give them the same rights as married couples when this question was asked after one about whether they favored or opposed allowing gays and lesbians to marry (45% favored legal agreements when asked after the marriage question, but 37% favored legal agreements without the immediate preceding context of a question about same-sex marriage). Responses to the question about same-sex marriage, meanwhile, were not significantly affected by its placement before or after the legal agreements question.

Another experiment embedded in a December 2008 Pew Research Center poll also resulted in a contrast effect. When people were asked “All in all, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the way things are going in this country today?” immediately after having been asked “Do you approve or disapprove of the way George W. Bush is handling his job as president?”; 88% said they were dissatisfied, compared with only 78% without the context of the prior question.

Responses to presidential approval remained relatively unchanged whether national satisfaction was asked before or after it. A similar finding occurred in December 2004 when both satisfaction and presidential approval were much higher (57% were dissatisfied when Bush approval was asked first vs. 51% when general satisfaction was asked first).

Several studies also have shown that asking a more specific question before a more general question (e.g., asking about happiness with one’s marriage before asking about one’s overall happiness) can result in a contrast effect. Although some exceptions have been found, people tend to avoid redundancy by excluding the more specific question from the general rating.

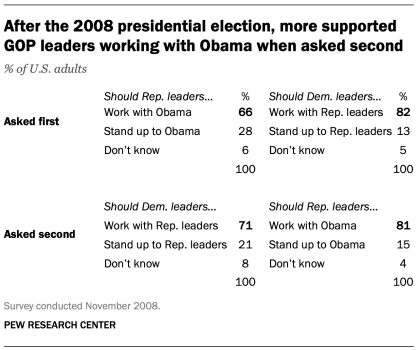

Assimilation effects occur when responses to two questions are more consistent or closer together because of their placement in the questionnaire. We found an example of an assimilation effect in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in November 2008 when we asked whether Republican leaders should work with Obama or stand up to him on important issues and whether Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders or stand up to them on important issues. People were more likely to say that Republican leaders should work with Obama when the question was preceded by the one asking what Democratic leaders should do in working with Republican leaders (81% vs. 66%). However, when people were first asked about Republican leaders working with Obama, fewer said that Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders (71% vs. 82%).

The order questions are asked is of particular importance when tracking trends over time. As a result, care should be taken to ensure that the context is similar each time a question is asked. Modifying the context of the question could call into question any observed changes over time (see measuring change over time for more information).

A questionnaire, like a conversation, should be grouped by topic and unfold in a logical order. It is often helpful to begin the survey with simple questions that respondents will find interesting and engaging. Throughout the survey, an effort should be made to keep the survey interesting and not overburden respondents with several difficult questions right after one another. Demographic questions such as income, education or age should not be asked near the beginning of a survey unless they are needed to determine eligibility for the survey or for routing respondents through particular sections of the questionnaire. Even then, it is best to precede such items with more interesting and engaging questions. One virtue of survey panels like the ATP is that demographic questions usually only need to be asked once a year, not in each survey.

U.S. Surveys

Other research methods, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology