Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 06 September 2023

Gender equality: the route to a better world

You have full access to this article via your institution.

The Mosuo people of China include sub-communities in which inheritance passes down either the male or the female line. Credit: TPG/Getty

The fight for global gender equality is nowhere close to being won. Take education: in 87 countries, less than half of women and girls complete secondary schooling, according to 2023 data. Afghanistan’s Taliban continues to ban women and girls from secondary schools and universities . Or take reproductive health: abortion rights have been curtailed in 22 US states since the Supreme Court struck down federal protections, depriving women and girls of autonomy and restricting access to sexual and reproductive health care .

SDG 5, whose stated aim is to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”, is the fifth of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, all of which Nature is examining in a series of editorials. SDG 5 includes targets for ending discrimination and violence against women and girls in both public and private spheres, eradicating child marriage and female genital mutilation, ensuring sexual and reproductive rights, achieving equal representation of women in leadership positions and granting equal rights to economic resources. Globally, the goal is not on track to being achieved, and just a handful of countries have hit all the targets.

How the world should oppose the Taliban’s war on women and girls

In July, the UN introduced two new indices (see go.nature.com/3eus9ue ), the Women’s Empowerment Index (WEI) and the Global Gender Parity Index (GGPI). The WEI measures women’s ability and freedoms to make their own choices; the GGPI describes the gap between women and men in areas such as health, education, inclusion and decision making. The indices reveal, depressingly, that even achieving a small gender gap does not automatically translate to high levels of women’s empowerment: 114 countries feature in both indices, but countries that do well on both scores cover fewer than 1% of all girls and women.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made things worse, with women bearing the highest burden of extra unpaid childcare when schools needed to close, and subjected to intensified domestic violence. Although child marriages declined from 21% of all marriages in 2016 to 19% in 2022, the pandemic threatened even this incremental progress, pushing up to 10 million more girls into risk of child marriage over the next decade, in addition to the 100 million girls who were at risk before the pandemic.

Of the 14 indicators for SDG 5, only one or two are close to being met by the 2030 deadline. As of 1 January 2023, women occupied 35.4% of seats in local-government assemblies, an increase from 33.9% in 2020 (the target is gender parity by 2030). In 115 countries for which data were available, around three-quarters, on average, of the necessary laws guaranteeing full and equal access to sexual and reproductive health and rights had been enacted. But the UN estimates that worldwide, only 57% of women who are married or in a union make their own decisions regarding sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Systemic discrimination against girls and women by men, in many contexts, remains a colossal barrier to achieving gender equality. But patriarchy is not some “natural order of things” , argues Ruth Mace, an anthropologist at University College London. Hundreds of women-centred societies exist around the world. As the science writer Angela Saini describes in her latest book, The Patriarchs , these are often not the polar opposite of male-dominated systems, but societies in which men and women share decision making .

After Roe v. Wade: dwindling US abortion access is harming health a year later

One example comes from the Mosuo people in China, who have both ‘matrilineal’ and ‘patrilineal’ communities, with rights such as inheritance passing down either the male or female line. Researchers compared outcomes for inflammation and hypertension in men and women in these communities, and found that women in matrilineal societies, in which they have greater autonomy and control over resources, experienced better health outcomes. The researchers found no significant negative effect of matriliny on health outcomes for men ( A. Z. Reynolds et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 30324–30327; 2020 ).

When it comes to the SDGs, evidence is emerging that a more gender-equal approach to politics and power benefits many goals. In a study published in May, Nobue Amanuma, deputy director of the Integrated Sustainability Centre at the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies in Hayama, Japan, and two of her colleagues tested whether countries with more women legislators, and more younger legislators, are performing better in the SDGs ( N. Amanuma et al. Environ. Res. Lett. 18 , 054018; 2023 ). They found it was so, with the effect more marked for socio-economic goals such as ending poverty and hunger, than for environmental ones such as climate action or preserving life on land. The researchers recommend further qualitative and quantitative studies to better understand the reasons.

The reality that gender equality leads to better outcomes across other SDGs is not factored, however, into most of the goals themselves. Of the 230 unique indicators of the SDGs, 51 explicitly reference women, girls, gender or sex, including the 14 indicators in SDG 5. But there is not enough collaboration between organizations responsible for the different SDGs to ensure that sex and gender are taken into account. The indicator for the sanitation target (SDG 6) does not include data disaggregated by sex or gender ( Nature 620 , 7; 2023 ). Unless we have this knowledge, it will be hard to track improvements in this and other SDGs.

The road to a gender-equal world is long, and women’s power and freedom to make choices is still very constrained. But the evidence from science is getting stronger: distributing power between genders creates the kind of world we all need and want to be living in.

Nature 621 , 8 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02745-9

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Sustainability

- Public health

The world needs a COP for water like the one for climate change

Correspondence 16 APR 24

Don’t dismiss carbon credits that aim to avoid future emissions

Correspondence 02 APR 24

Don’t underestimate the rising threat of groundwater to coastal cities

Correspondence 26 MAR 24

What toilets can reveal about COVID, cancer and other health threats

News Feature 17 APR 24

Smoking bans are coming: what does the evidence say?

News 17 APR 24

It’s time to talk about the hidden human cost of the green transition

Do climate lawsuits lead to action? Researchers assess their impact

News Explainer 16 APR 24

Exclusive: official investigation reveals how superconductivity physicist faked blockbuster results

News 06 APR 24

Is IVF at risk in the US? Scientists fear for the fertility treatment’s future

News 02 APR 24

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Publications

Key Findings

- Infographics

- Full report

Global Gender Gap Report 2021

The Global Gender Gap Index benchmarks the evolution of gender-based gaps among four key dimensions (Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment) and tracks progress towards closing these gaps over time.

This year, the Global Gender Gap index benchmarks 156 countries, providing a tool for cross-country comparison and to prioritize the most effective policies needed to close gender gaps. The methodology of the index has remained stable since its original conception in 2006, providing a basis for robust cross-country and time-series analysis. The Global Gender Gap Index measures scores on a 0 to 100 scale and scores can be interpreted as the distance to parity (i.e. the percentage of the gender gap that has been closed).

The 14th edition of the report, the Global Gender Gap Report 2020 , was launched in December 2019, using the latest available data at the time. The 15th edition, the Global Gender Gap Report 2021 , comes out a little over one year after COVID-19 was officially declared a pandemic. Preliminary evidence suggests that the health emergency and the related economic downturn have impacted women more severely than men, partially re-opening gaps that had already been closed.

The 2021 report’s findings are listed below.

Global Trends and Outcomes

- Globally, the average distance completed to parity is at 68%, a step back compared to 2020 (-0.6 percentage points). These figures are mainly driven by a decline in the performance of large countries. On its current trajectory, it will now take 135.6 years to close the gender gap worldwide.

- The gender gap in Political Empowerment remains the largest of the four gaps tracked, with only 22% closed to date, having further widened since the 2020 edition of the report by 2.4 percentage points. Across the 156 countries covered by the index, women represent only 26.1% of some 35,500 parliament seats and just 22.6% of over 3,400 ministers worldwide. In 81 countries, there has never been a woman head of state, as of 15th January 2021. At the current rate of progress, the World Economic Forum estimates that it will take 145.5 years to attain gender parity in politics.

- Widening gender gaps in Political Participation have been driven by negative trends in some large countries which have counterbalanced progress in another 98 smaller countries. Globally, since the previous edition of the report, there are more women in parliaments, and two countries have elected their first female prime minister (Togo in 2020 and Belgium in 2019).

- The gender gap in Economic Participation and Opportunity remains the second-largest of the four key gaps tracked by the index. According to this year’s index results 58% of this gap has been closed so far. The gap has seen marginal improvement since the 2020 edition of the report and as a result we estimate that it will take another 267.6 years to close.

- The slow progress seen in closing the Economic Participation and Opportunity gap is the result of two opposing trends. On one hand, the proportion of women among skilled professionals continues to increase, as does progress towards wage equality, albeit at a slower pace. On the other hand, overall income disparities are still only part-way towards being bridged and there is a persistent lack of women in leadership positions, with women representing just 27% of all manager positions. Additionally, the data available for the 2021 edition of the report does not yet fully reflect the impact of the pandemic. Projections for a select number of countries show that gender gaps in labour force participation are wider since the outbreak of the pandemic. Globally, the economic gender gap may thus be between 1% and 4% wider than reported.

- Gender gaps in Educational Attainment and Health and Survival are nearly closed. In Educational Attainment, 95% of this gender gap has been closed globally, with 37 countries already at parity. However, the ‘last mile’ of progress is proceeding slowly. The index estimates that on its current trajectory, it will take another 14.2 years to completely close this gap. In Health and Survival, 96% of this gender gap has been closed, registering a marginal decline since last year (not due to COVID-19), and the time to close this gap remains undefined. For both education and health, while progress is higher than for economy and politics in the global data, there are important future implications of disruptions due to the pandemic, as well as continued variations in quality across income, geography, race, and ethnicity.

Gender Gaps, COVID-19 and the Future of Work

- High-frequency data for selected economies from ILO, LinkedIn and Ipsos offer a timely analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender gaps in economic participation. Early projections from ILO suggest 5% of all employed women lost their jobs, compared with 3.9% of employed men. LinkedIn data further shows a marked decline of women’s hiring into leadership roles, creating a reversal of 1 to 2 years of progress across multiple industries. While industries such as Software and IT Services, Financial Services, Health and Healthcare, and Manufacturing are countering this trend, there is a more severe destruction of overall roles in industries with higher participation of women, such as the Consumer sector, Non-profits, and Media and Communication. Additionally, Ipsos data from January 2021 shows that a longer “double-shift” of paid and unpaid work in a context of school closures and limited availability of care services have contributed to an overall increase of stress, anxiety around job insecurity and difficulty in maintaining work-life balance among women with children.

- The COVID-19 crisis has also accelerated automation and digitalization, speeding up labour market disruption. Data points to significant challenges for gender parity in the future of jobs due to increasing occupational gender-segregation. Only two of the eight tracked “jobs of tomorrow” clusters (People & Culture and Content Production) have reached gender parity, while most show a severe underrepresentation of women.

- Gender gaps are more likely in sectors that require disruptive technical skills. For example, in Cloud Computing, women make up 14% of the workforce; in Engineering, 20%; and in Data and AI, 32%. While the eight job clusters typically experience a high influx of new talent, at current rates those inflows do not re-balance occupational segregation and transitioning to fields where women are currently underrepresented appears to remain difficult. For example, the current share of women in Cloud Computing is 14.2% and that figure has only improved by 0.2 percentage points, while the share of women in Data and AI roles is 32.4% and that figure has seen a mild decline of 0.1 percentage points since February 2018.

- This report also premiers a new measure created in collaboration with the LinkedIn Economic Graph team which captures the difference between men and women’s likelihood to make an ambitious job switch. The indicator shows that women experience a bigger gender gap in potential-based job transitions in fields where they are currently under-represented, such as Cloud Computing, where the job-switching gap is 58%; Engineering, where the gap is 42%; and Product Development, where the gap is 19%.

- Through the combined effect of accelerated automation, the growing “double shift”, and other labour market dynamics such as occupational segregation, the pandemic is likely to have a scarring effect on future economic opportunities for women, risking inferior reemployment prospects and a persistent drop in income. Gender-positive recovery policies and practices can tackle those potential challenges. First, the report recommends further investments into the care sector and into equitable access to care leave for men and women. Second, policies and practices need to proactively focus on overcoming occupational segregation by gender. Third, effective mid-career reskilling policies, combined with managerial practices, which embed sound, unbiased hiring and promotion practices, will pave the way for a more gender-equal future of work.

Gender Gaps by Economy and Region

- Iceland is the most gender-equal country in the world for the 12th time. The top 10 includes:

- The five most-improved countries in the overall index this year are Lithuania, Serbia, Timor-Leste, Togo and United Arab Emirates, having narrowed their gender gaps by at least 4.4 percentage points or more. Timor-Leste and Togo are also among the four countries (including Cote d’Ivoire and Jordan) that have managed to close their Economic Participation and Opportunity gap by at least 10 full percentage points in one year. Three new countries have been assessed this year for the first time: Afghanistan (44.4% of the gender gap closed so far, 156th), Guyana (72.8%, 53rd) and Niger (62.9%, 138th).

- There are significant disparities across and within various geographies. Western Europe remains the region that has progressed the most towards gender parity (77.6%) and is further progressing this year. North America is the second-most advanced (76.4%), also improving this year, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (72.1%) and Eastern Europe and Central Asia (71.2%). A few decimal points below is the East Asia and the Pacific region (68.9%), one of the most-improved regions, just ahead of Sub- Saharan Africa (67.2%) and surpassing South Asia (62.7%). The Middle East and North Africa region remains the area with the largest gap (60.9%).

- At the current relative pace, gender gaps can potentially be closed in 52.1 years in Western Europe, 61.5 years in North America, and 68.9 years in Latin America and the Caribbean. In all other regions it will take over 100 years to close the gender gap: 121.7 years in Sub-Saharan Africa, 134.7 years in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, 165.1 years in East Asia and the Pacific, 142.4 years in Middle East and North Africa, and 195.4 years in South Asia.

Gender equality in research: papers and projects by Highly Cited Researchers

Strategic Alliances and Engagement Manager

Empowering women and girls is a critical target of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this installment of our blog series about Highly Cited Researchers contributing to the UN SDGs, we focus on SDG 5: Gender Equality. We discuss the research that Highly Cited Researchers have published and the trends we’re seeing emerge.

Gender equality is a fundamental human right and yet women have just three quarters of the legal rights of men today. While the speed of progress differs across regions, laws, policies, budgets and institutions must all be strengthened on an international scale to grant women equal rights as men.

The socioeconomic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and high-profile policy changes like the overturning of Roe v. Wade have shown how much work needs to be done. The COVID-19 pandemic caused many women to leave the workforce and amplified challenges related to child and elder care, with women shouldering much of the burden. This can disproportionately affect girls’ educational prospects and, as is often the case in stressful environments and during times of crisis, puts women at increased risk of domestic violence .

While some high-profile issues related to women’s rights and safety make the news cycle, gender inequalities are firmly entrenched in every society, impacting the daily lives of women and girls in ways that are rarely reported on. As Kamala Harris, Vice President of the United States, once said , “from the economy to climate change to criminal justice reform to national security, all issues are women’s issues.”

Women’s issues are interconnected with all the SDGs, as we touched on in our recent post in this series, which explored the research centered around SDG 16: Peaceful, just and strong institutions . In that post we found that sexual, domestic and intimate partner abuse and violence against women are the most published topics related to SDG 16.

In this post, we look at Highly Cited Researchers who focus specifically on SDG 5 and issues of equality and gender .

What is SDG 5: Gender equality?

SDG 5: Gender Equality is intended to address the serious inequalities and threats faced by women around the globe. The targets related to this goal include:

- End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere.

- Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation.

- Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life.

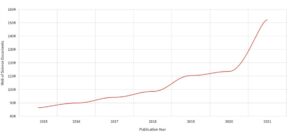

There has been an increase in articles and reviews related to this SDG since the establishment of the SDGs in 2015. This trend graph from InCites Benchmarking & Analytics ™, using Web of Science Core Collection ™ data, shows growth from 86,000 papers in 2015 to 152,000 in 2021. That’s a 77% increase in six years.

Growth in academic papers related to SDG 5: Gender Equality

Source: Incites Benchmarking & Analytics. Dataset: articles and reviews related to SDG 5: Gender Equality published between 2015-2021.

The top ten countries publishing on SDG 5: Gender Equality during this period are shown below, with the U.S. producing roughly one third of all papers.

Countries producing the most papers related to SDG 5: Gender Equality

We explore these angles from research published between 2010 and 2020 in more detail, below.

Inequalities in the treatment of women during childbirth

Özge Tunçalp , a Highly Cited Researcher from the World Health Organization (WHO), wrote a systematic review in 2015 about the mistreatment of women globally during childbirth. This paper, coauthored with Johns Hopkins University, McGill University, University of Sao Paulo and PSI (a global nonprofit working in healthcare), has been cited more than 590 times to date in the Web of Science Core Collection. Tunçalp’s paper provides further information about the type and degree of mistreatment in childbirth, which supports the development of measurement tools, programs and interventions in this area.

Tunçalp authored another open access paper on this topic in 2019 , which followed women in four low-income and middle-income countries to study their experiences during childbirth. Unfortunately, more than one third of the women in the study experienced mistreatment during childbirth, a critical time in their lives, with younger and less educated women found to be most at risk. Beyond showing that mistreatment during childbirth exists, this study demonstrates the inequalities in how some women are treated in comparison to others, which informs the interventions needed.

“Our research showed that mistreatment during childbirth occurs across low-, middle- and high-income countries and good quality of care needs to be respectful as well as safe, no matter where you are in the world.” Dr Özge Tunçalp, World Health Organization

According to Dr. Tunçalp, “Women and families have a right to positive pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal experiences, supported by empowered health workers, majority of whom are women. Improving the experience of care throughout pregnancy and childbirth is essential to help increase the trust in facility-based care – as well as ensuring access to quality postnatal care following birth. Our research showed that mistreatment during childbirth occurs across low-, middle- and high-income countries and good quality of care needs to be respectful as well as safe, no matter where you are in the world. It was critical to ensure that these findings were translated into WHO global recommendations to inform country policy and programmes .”

Autism spectrum disorder and the gender bias in diagnosis

William Mandy, a Highly Cited Researcher in Psychiatry and Psychology, looks at gender differences related to autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Mandy, from University College London, and his co-authors found that the male-to-female ratio of children with ASD is closer to 3:1, not the often assumed 4:1 . With an apparent gender bias in diagnosis, girls who meet the criteria for ASD are at risk of being misdiagnosed or not diagnosed at all. This can cause confusion and challenges with social interactions growing up, and can put women and girls at greater risk of traumatic experiences. Mandy et al’s paper has been cited more than 830 times to date.

“The reason for this diagnostic bias is that sex and gender influence how autism presents, such that the presentations of autistic girls and women often do not fit well with current conceptualisations of the condition, which were largely based on mainly male samples.” Dr William Mandy, University College London

When asked about the relevance of his research to the clinical community, Dr. Mandy said: “Clinicians have long held the suspicion that there is a diagnostic bias against autistic girls and women – that they are more likely to fly under the diagnostic radar. Our work (Loomes et al., 2017) has helped to provide systematic, empirical evidence that this bias does indeed exist, and to quantify its impact, in terms of how many autistic girls go undiagnosed.

The reason for this diagnostic bias is that sex and gender influence how autism presents, such that the presentations of autistic girls and women often do not fit well with current conceptualisations of the condition, which were largely based on mainly male samples. Therefore, to address the gender bias in autism diagnosis, we need an evidence-based understanding of the characteristics of autistic girls and women. Our study (Bargiela et al, 2016), in which we interviewed late-diagnosed autistic women about their lives, helps do this, revealing distinctive features of autistic women and of their experiences. This knowledge is shaping research and clinical practice.”

Going forward

The above papers are just a few examples of Highly Cited Researchers contributing to SDG 5-Gender Equality. Others focus on depression, Alzheimer’s Disease, cardiovascular disease and ovarian cancer. The fact that biomedical research featured so prominently in these results should not be a surprise. Gender bias has been identified in many areas of healthcare, including patient diagnosis , discrimination against health care workers , and low rates of women in clinical studies to name a few.

The Highly Cited Researchers working on gender equality within their respective fields, which also include social sciences, economics and other areas in addition to medicine, are helping to address the complex issues related to SDG 5. And what’s worthy of note is that many of the researchers mentioned here were named as Highly Cited Researchers in the cross-field category, which identifies researchers who have contributed to Highly Cited Papers across several different fields. This shows that a multifaceted and integrated approach to gender equality research may be playing a significant role in addressing this global issue.

Stay up to date

We discussed the SDG Publishers Compact in the first post in our series and then celebrated the Highly Cited Researchers in SDG 1: No Poverty and SDG 2: Zero Hunger. We then covered SDG 3: Good Health and Well-Being and SDG 4: Quality Education , and then jumped ahead to cover SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions . Alongside this, we also looked at Ukrainian research contributions to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, here , and published an Institute for Scientific Information (ISI)™Insights paper called, Climate change collaboration: Why we need an international approach to research .

In our next post, we will identify Highly Cited Researchers who are working to address SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation.

At Clarivate, sustainability is at the heart of everything we do, and this includes support of human rights, diversity and inclusion, and social justice. Read more about our commitment to driving sustainability worldwide, and see highlights from our 2021 Clarivate Sustainability Report .

Related posts

Demonstrating socioeconomic impact – a historical perspective of ancient wisdom and modern challenges.

Unlocking U.K. research excellence: Key insights from the Research Professional News Live summit

For better insights, assess research performance at the department level

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Closing the gender...

Closing the gender health gap: a £39bn boost to the economy, as well as lives

- Related content

- Peer review

- Sarah Graham , freelance health journalist

- Hertfordshire, UK

- contact{at}sarah-graham.co.uk

The UK has the 12th largest gender health gap in the world. Closing it will require investment, but would also reap rewards for women and the country, reports Sarah Graham

Closing the gender health gap by 2040 could add almost £39bn to the UK economy and give each British woman around 9.5 more days of good health a year. That’s according to data shared with The BMJ by the McKinsey Health Institute, whose recent report with the World Economic Forum describes investing in women’s health as a $1tn global opportunity, with a $3 return on investment for every $1 spent. 1

The report quantifies the personal and economic cost of years lost to disability, ill health, and early death, and highlights that women globally spend on average 25% more of their lives in poor health than men. The economic case is compelling—by investing in research, innovation, and data collection and improving access to healthcare services, economies around the world could see a $400bn boost to productivity, as well as improving the health and lives of 3.9 billion women. 1 In March US president Joe Biden signed an executive order expanding the government’s research on women’s health, with $200m pledged for the following year.

A 2020 analysis of health data across 158 countries, carried out by men’s wellbeing platform Manual, 2 found the UK had the largest women’s health gap (where a country’s ranking for women’s health is lower than their rank for men’s health) in the world.

The UK government published its women’s health strategy for England 3 in summer 2022. This 10 year plan, informed by consultation with women’s health organisations and more than 100 000 individuals, includes commitments on research, training, and service provision (see box 1 ). Lesley Regan—former president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)—was appointed to support the strategy in the role of women’s health ambassador in June 2022, and reappointed in January 2024 for a further two years.

UK government spending pledges for women’s health in England

April 2022 - July 2023 £53m, through the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), for research with a focus on conditions specific to women’s health—including endometriosis, menopause, and cervical cancer

April 2023 - March 2025 £25m over two years—or £595 000 for each integrated care board—to establish at least one women’s health hub in each area

August 2023 New policy research unit dedicated to reproductive health commissioned, with an initial investment of £3m over three years

January 2024 £50m for an NIHR challenge for research tackling maternal health disparities

March 2024 £35m to tackle maternity safety, including £9m for tools training to reduce brain injuries in childbirth

Total = £166m

Earlier this month, the NHS also appointed Sue Mann, a consultant and lead for women’s health in City and Hackney, NHS North East London, as its first national clinical director for women’s health—to “help implement the women’s health strategy.”

The strategy was welcomed by women’s health groups, but questions were asked about how the plans would be funded. Edward Morris, then-president of RCOG, expressed concern about “the lack of dedicated funding to make these ambitions a reality.”

More recently, women’s health campaigner and author Kate Muir told Femtech World , “Until the women’s health strategy is properly funded, it will just be a PR sticking plaster covering up ongoing chaos, misery, and year long waiting lists.” 4

Ringfencing research funding and upskilling researchers

Research investment will be vital to improvements in women’s healthcare. Women have historically been excluded from, or underrepresented in, medical research, while conditions that predominantly affect women have been neglected and underfunded, 5 leaving large gaps in medical knowledge and understanding about female bodies.

Data from the McKinsey Health Institute show the UK’s top 10 women’s health conditions contribute to half of the health impact on gross domestic product. These conditions include premenstrual syndrome, ovarian and uterine cancers, and other gynaecological diseases, 6 but also depressive and anxiety disorders, migraine, asthma, ischaemic heart disease, and osteoarthritis.

In 2022, just 2.4% of public and charitably funded research in the UK went to reproductive health and childbirth—a total of £68.4m. 7 Fewer than 6% of grants between 2009 and 2020 in the UK looked at female specific outcomes or women’s health. 1 (It is not possible to differentiate male specific funding, McKinsey says.) And—unlike Canada, the US, and the EU’s Horizon Europe funding scheme—the UK currently has no standardised policy to ensure researchers account for sex and gender in their work.

Filling these research gaps is one of the six key priorities laid out in the women’s health strategy, with just over £100m of research investment announced so far, and a new policy research unit dedicated to reproductive health (see box 1 ).

“This is a good start, but more money will be needed,” says Kate Womersley, an NHS psychiatry doctor and research fellow at the George Institute for Global Health and Imperial College London. Researchers and policy makers also need to take a much wider view of what constitutes women’s health, she adds. 8

“The commitments on research are quite vague in the women’s health strategy. Women’s health is any condition that affects girls and women at any point in their life. You’re only going to get good care if you invest in high quality research—research that focuses on gynaecological and obstetric problems, but also research that looks at women’s health in all specialties and takes seriously the intersectional factors of race and age.”

Enter Medical Science Sex and Gender Equity (Message), a research project at the George Institute of which Womersley is co-principal investigator. 9 Message aims to improve sex and gender equality across the UK’s research sector by co-creating a policy framework for research funders. This is to be released in the spring, Womersley says, and 29 organisations across the UK medical research community—including funders such as NIHR and journal publishers including The BMJ —have already signed a statement indicating their support.

“Researchers who apply for funding will need to follow these policies to meet funders’ standards,” says Womersley. “This will require upskilling a whole generation or more of researchers who haven’t done this until now. There are time and training implications, and cost implications around increasing sample sizes to give meaningful findings for people of different sexes and genders.”

Sustainable funding for care?

Investment in research must sit alongside investment in care. Rolling out a nationwide network of women’s health hubs (WHHs) is a central part of the women’s health strategy, promising a one stop shop for reproductive health in every integrated care board (ICB), which should help to bridge some of the gaps between primary and secondary care. The government’s own economic modelling shows a £5 return on investment for every £1 spent on WHHs, but concerns have again been expressed about the sustainability of funding.

In March 2023, the government announced a one-off £25m investment in the scheme, with each of England’s 42 ICBs to receive £595 000 over the following two years. 10 ICBs were encouraged to use their full funding allocation to establish at least one hub in their area. But ministers noted they were only expected to do so if running the hub would still be affordable once this initial investment runs out.

For health economics policy adviser Bridget Gorham at the NHS Confederation, this raised some questions. “Given it’s intended to serve half the population £25m is not a lot of money. I started to look into arguments for more robust and sustained funding for an area that has historically been neglected,” she says.

The NHS Confederation is now running its own economic modelling project, led by Gorham, to make that case. With their findings to be published this summer, Gorham’s hope is that it will support further funding for the goals the strategy sets out. “It’s a 10 year strategy with only two years of funding,” she says. “We’re trying to demonstrate the return on investment of having a healthy and productive 51% of the population, but with the caveat that this won’t be an immediate return on investment because the inequalities in the system will take time to untangle.”

Another problem, Gorham adds, is that when NHS England wrote to all ICBs in November, advising on immediate action to “achieve financial balance,” women’s health was not a protected budget. As a result, she explains, “we heard from several integrated care systems that their WHH funding ended up being thrown into the black hole to break even for the financial year. Because the funding isn’t recurrent, the obvious question is how integrated care systems can continue the service after those initial two years of funding.”

Similar misgivings are shared by RCOG. “Historically, investment in women’s health services has been insufficient, short term, and siloed. We therefore welcomed the ambitious vision set out in the women’s health strategy for England. WHHs are a very positive first step,” says Ranee Thakar, president of RCOG.

She adds, however, “To deliver on the promise of the strategy and truly transform care to meet the holistic needs of women across their lives, a long term and sustainable approach to funding is needed. We urge the government to commit to this.”

Robbing Patricia to pay Paula?

Another concern is that WHHs could come at the expense of improving women’s health provision across the whole of primary care. A joint statement published by the Royal College of GPs, RCOG, the Faculty for Sexual and Reproductive Health, and the British Menopause Society 11 highlights existing workforce pressures across the health service and states that, “In order to make sustainable improvements to women’s health and harness the benefits of the WHH model, there must be a focus on equipping primary care with funding, staffing capacity, and skills and knowledge to consistently deliver high quality women’s healthcare.”

Challenges also remain in secondary care, such as gynaecology waiting lists 12 and a shortage of 2500 midwives across England. 13 14 In March, as part of the spring budget, the government announced an additional £35m in funding to tackle maternity safety, including investment in training, as well as funding for 160 new midwives over the next three years.

“Any money for maternity services is welcome, but this new funding is still woefully inadequate. The promise of 160 midwives over three years is a drop in the ocean of the staffing crisis, and is unlikely even to replace the midwives who leave the register or retire during that time,” says midwife Leah Hazard, author of Womb and Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Tale. “How can staff have protected time to complete the training that’s been announced when there aren’t enough midwives to cover clinical care? Once again, the Tories are tossing crumbs to a system on its knees.”

The Royal College of Midwives cautiously welcomed the announced investment and, at the time of writing, was seeking clarification from the government on the role the new midwives (which equates to roughly one for each NHS trust) will play in the recruitment and retention of the wider midwifery workforce.

Womersley notes that there are also large gaps across women’s wider health—in areas such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, dementia, and autoimmune disease—that aren’t currently prioritised by the women’s health strategy.

“We’re going in the right direction, but I have worries about the longer term investment plan,” says Hannah Wrathall, founder of women’s health communications firm Wrapp Consultancy. “It would be good to have some reassurance, particularly in an election year, that this is a sustained, ongoing effort that’s going to be ingrained in our health system regardless of political party.”

Perhaps the real question then is not how much investment is needed to close the gender health gap but if stakeholders can count on consistent funding—and continued political will—to see it through. With significant potential returns on even relatively small investments (see box 2 ), not all changes will require large funding pots, as Regan has noted. But what will be key is effective implementation, strong leadership, and sustainable, long term planning.

The economic case for action—a lesson from the US

In the US—where the 1993 NIH Revitalization Act established guidelines for sex and gender inclusion in clinical research—non-profit organisation Women’s Health Access Matters (WHAM) worked with research institution RAND to model the health and economic impacts of doubling funding for women specific research in four areas: autoimmune disease, brain health, cancer, and cardiovascular disease.

“We were conservative in our modelling, so we assumed small health improvements of 0.1% or less,” explains Lori Frank, president of WHAM, who previously worked on the research as a RAND scientist. “Then we looked at how much is invested in women focused research, and across all the therapeutic areas we’d chosen it was 15% or less. We thought it was politically feasible to think about what might happen if we doubled that funding.”

Take rheumatoid arthritis: women make up 60% of patients in the US, yet when WHAM looked at NIH funding for the disease they found that just 7% of the budget went to women focused research. By doubling that funding, even assuming just a 0.1% health improvement, WHAM’s economic model showed a staggering 174 000% return on investment. 15

“When you apply funding correctly, even under a budget constraint, you improve outcomes and so reduce your costs in the long run. It becomes a virtuous circle,” says Valentina Sartori, a partner at McKinsey and one of the lead authors on the gender health gap report.

More women in decision making positions will help, she adds, but so too will stretch goals and incentives—for public and private funders—to help “force the system” and drive funding to areas of unmet need. As Sartori and her colleagues state in the report, “When tackling women’s health, the solution is not to divide more slices of one pie: it’s to make more pies.”

SG is author of Rebel Bodies: A guide to the gender health gap revolution .

I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Commissioned; not peer reviewed.

- ↵ World Economic Forum, McKinsey Health Institute. Closing the women’s health gap: a $1 trillion opportunity to improve lives and economies. January 2024. www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/mckinsey%20health%20institute/our%20insights/closing%20the%20womens%20health%20gap%20a%201%20trillion%20dollar%20opportunity%20to%20improve%20lives%20and%20economies/closing-the-womens-health-gap-report.pdf

- ↵ Manual. The men’s health gap. www.manual.co/mens-health-gap

- ↵ Department of Health and Social Care. Women’s health strategy for England. 30 August 2022. www.gov.uk/government/publications/womens-health-strategy-for-england/womens-health-strategy-for-england

- ↵ Mihalia S. Women’s health strategy risks becoming “PR sticking plaster,” warn campaigners. Femtech World . 2 February 2024. www.femtechworld.co.uk/news/womens-health-strategy-risks-becoming-pr-sticking-plaster-warn-campaigners

- ↵ Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global health metrics: other gynecological diseases—level 4 cause. www.healthdata.org/results/gbd_summaries/2019/other-gynecological-diseases-level-4-cause

- ↵ UK Clinical Research Collaboration. UK health research analysis 2022. https://hrcsonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/UK_Health_Research_Analysis_Report_2022_web_v1-0.pdf

- Womersley K ,

- Strachan S ,

- Medical Science Sex and Gender Equity

- ↵ Department of Health and Social Care, NHS England, Caulfield M, Barclay S. £25 million for women’s health hub expansion. 8 March 2023. www.gov.uk/government/news/25-million-for-womens-health-hub-expansion

- ↵ RCGP. Achieving success with the women’s health hub (WHH) model. www.rcgp.org.uk/representing-you/policy-areas/womens-health-hub-model

- ↵ RCOG. Left for too long. www.rcog.org.uk/about-us/campaigning-and-opinions/left-for-too-long-understanding-the-scale-and-impact-of-gynaecology-waiting-lists

- ↵ Royal College of Midwives. Midwives on the register doesn’t mean midwives in post, says RCM. 2023. www.rcm.org.uk/media-releases/2023/november/midwives-on-the-register-doesn-t-mean-midwives-in-post-says-rcm

- ↵ RCM. RCM tells politicians how to fix the midwifery staffing crisis with new pre-election guide. 2024. www.rcm.org.uk/media-releases/2024/february/rcm-tells-politicians-how-to-fix-the-midwifery-staffing-crisis-with-new-pre-election-guide

- ↵ Women’s Health Access Matters. The WHAM report. https://thewhamreport.org

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Twenty years of gender equality research: A scoping review based on a new semantic indicator

Contributed equally to this work with: Paola Belingheri, Filippo Chiarello, Andrea Fronzetti Colladon, Paola Rovelli

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Energia, dei Sistemi, del Territorio e delle Costruzioni, Università degli Studi di Pisa, Largo L. Lazzarino, Pisa, Italy

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Engineering, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy, Department of Management, Kozminski University, Warsaw, Poland

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Faculty of Economics and Management, Centre for Family Business Management, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Bozen-Bolzano, Italy

- Paola Belingheri,

- Filippo Chiarello,

- Andrea Fronzetti Colladon,

- Paola Rovelli

- Published: September 21, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474

- Reader Comments

9 Nov 2021: The PLOS ONE Staff (2021) Correction: Twenty years of gender equality research: A scoping review based on a new semantic indicator. PLOS ONE 16(11): e0259930. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259930 View correction

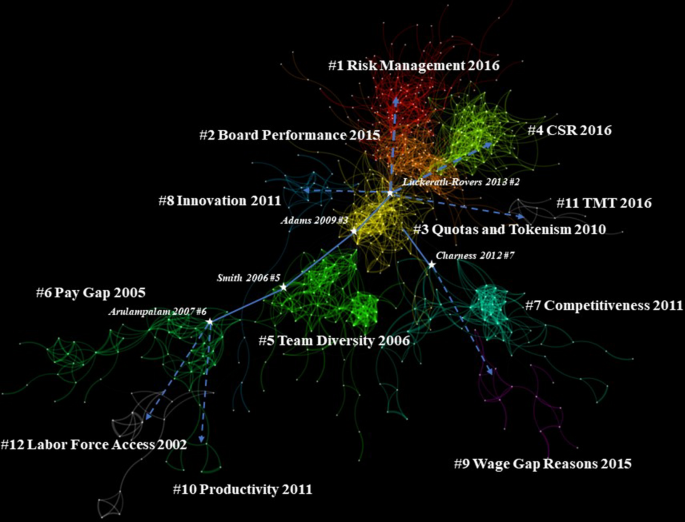

Gender equality is a major problem that places women at a disadvantage thereby stymieing economic growth and societal advancement. In the last two decades, extensive research has been conducted on gender related issues, studying both their antecedents and consequences. However, existing literature reviews fail to provide a comprehensive and clear picture of what has been studied so far, which could guide scholars in their future research. Our paper offers a scoping review of a large portion of the research that has been published over the last 22 years, on gender equality and related issues, with a specific focus on business and economics studies. Combining innovative methods drawn from both network analysis and text mining, we provide a synthesis of 15,465 scientific articles. We identify 27 main research topics, we measure their relevance from a semantic point of view and the relationships among them, highlighting the importance of each topic in the overall gender discourse. We find that prominent research topics mostly relate to women in the workforce–e.g., concerning compensation, role, education, decision-making and career progression. However, some of them are losing momentum, and some other research trends–for example related to female entrepreneurship, leadership and participation in the board of directors–are on the rise. Besides introducing a novel methodology to review broad literature streams, our paper offers a map of the main gender-research trends and presents the most popular and the emerging themes, as well as their intersections, outlining important avenues for future research.

Citation: Belingheri P, Chiarello F, Fronzetti Colladon A, Rovelli P (2021) Twenty years of gender equality research: A scoping review based on a new semantic indicator. PLoS ONE 16(9): e0256474. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474

Editor: Elisa Ughetto, Politecnico di Torino, ITALY

Received: June 25, 2021; Accepted: August 6, 2021; Published: September 21, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Belingheri et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting information files. The only exception is the text of the abstracts (over 15,000) that we have downloaded from Scopus. These abstracts can be retrieved from Scopus, but we do not have permission to redistribute them.

Funding: P.B and F.C.: Grant of the Department of Energy, Systems, Territory and Construction of the University of Pisa (DESTEC) for the project “Measuring Gender Bias with Semantic Analysis: The Development of an Assessment Tool and its Application in the European Space Industry. P.B., F.C., A.F.C., P.R.: Grant of the Italian Association of Management Engineering (AiIG), “Misure di sostegno ai soci giovani AiIG” 2020, for the project “Gender Equality Through Data Intelligence (GEDI)”. F.C.: EU project ASSETs+ Project (Alliance for Strategic Skills addressing Emerging Technologies in Defence) EAC/A03/2018 - Erasmus+ programme, Sector Skills Alliances, Lot 3: Sector Skills Alliance for implementing a new strategic approach (Blueprint) to sectoral cooperation on skills G.A. NUMBER: 612678-EPP-1-2019-1-IT-EPPKA2-SSA-B.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The persistent gender inequalities that currently exist across the developed and developing world are receiving increasing attention from economists, policymakers, and the general public [e.g., 1 – 3 ]. Economic studies have indicated that women’s education and entry into the workforce contributes to social and economic well-being [e.g., 4 , 5 ], while their exclusion from the labor market and from managerial positions has an impact on overall labor productivity and income per capita [ 6 , 7 ]. The United Nations selected gender equality, with an emphasis on female education, as part of the Millennium Development Goals [ 8 ], and gender equality at-large as one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030 [ 9 ]. These latter objectives involve not only developing nations, but rather all countries, to achieve economic, social and environmental well-being.

As is the case with many SDGs, gender equality is still far from being achieved and persists across education, access to opportunities, or presence in decision-making positions [ 7 , 10 , 11 ]. As we enter the last decade for the SDGs’ implementation, and while we are battling a global health pandemic, effective and efficient action becomes paramount to reach this ambitious goal.

Scholars have dedicated a massive effort towards understanding gender equality, its determinants, its consequences for women and society, and the appropriate actions and policies to advance women’s equality. Many topics have been covered, ranging from women’s education and human capital [ 12 , 13 ] and their role in society [e.g., 14 , 15 ], to their appointment in firms’ top ranked positions [e.g., 16 , 17 ] and performance implications [e.g., 18 , 19 ]. Despite some attempts, extant literature reviews provide a narrow view on these issues, restricted to specific topics–e.g., female students’ presence in STEM fields [ 20 ], educational gender inequality [ 5 ], the gender pay gap [ 21 ], the glass ceiling effect [ 22 ], leadership [ 23 ], entrepreneurship [ 24 ], women’s presence on the board of directors [ 25 , 26 ], diversity management [ 27 ], gender stereotypes in advertisement [ 28 ], or specific professions [ 29 ]. A comprehensive view on gender-related research, taking stock of key findings and under-studied topics is thus lacking.

Extant literature has also highlighted that gender issues, and their economic and social ramifications, are complex topics that involve a large number of possible antecedents and outcomes [ 7 ]. Indeed, gender equality actions are most effective when implemented in unison with other SDGs (e.g., with SDG 8, see [ 30 ]) in a synergetic perspective [ 10 ]. Many bodies of literature (e.g., business, economics, development studies, sociology and psychology) approach the problem of achieving gender equality from different perspectives–often addressing specific and narrow aspects. This sometimes leads to a lack of clarity about how different issues, circumstances, and solutions may be related in precipitating or mitigating gender inequality or its effects. As the number of papers grows at an increasing pace, this issue is exacerbated and there is a need to step back and survey the body of gender equality literature as a whole. There is also a need to examine synergies between different topics and approaches, as well as gaps in our understanding of how different problems and solutions work together. Considering the important topic of women’s economic and social empowerment, this paper aims to fill this gap by answering the following research question: what are the most relevant findings in the literature on gender equality and how do they relate to each other ?

To do so, we conduct a scoping review [ 31 ], providing a synthesis of 15,465 articles dealing with gender equity related issues published in the last twenty-two years, covering both the periods of the MDGs and the SDGs (i.e., 2000 to mid 2021) in all the journals indexed in the Academic Journal Guide’s 2018 ranking of business and economics journals. Given the huge amount of research conducted on the topic, we adopt an innovative methodology, which relies on social network analysis and text mining. These techniques are increasingly adopted when surveying large bodies of text. Recently, they were applied to perform analysis of online gender communication differences [ 32 ] and gender behaviors in online technology communities [ 33 ], to identify and classify sexual harassment instances in academia [ 34 ], and to evaluate the gender inclusivity of disaster management policies [ 35 ].

Applied to the title, abstracts and keywords of the articles in our sample, this methodology allows us to identify a set of 27 recurrent topics within which we automatically classify the papers. Introducing additional novelty, by means of the Semantic Brand Score (SBS) indicator [ 36 ] and the SBS BI app [ 37 ], we assess the importance of each topic in the overall gender equality discourse and its relationships with the other topics, as well as trends over time, with a more accurate description than that offered by traditional literature reviews relying solely on the number of papers presented in each topic.

This methodology, applied to gender equality research spanning the past twenty-two years, enables two key contributions. First, we extract the main message that each document is conveying and how this is connected to other themes in literature, providing a rich picture of the topics that are at the center of the discourse, as well as of the emerging topics. Second, by examining the semantic relationship between topics and how tightly their discourses are linked, we can identify the key relationships and connections between different topics. This semi-automatic methodology is also highly reproducible with minimum effort.

This literature review is organized as follows. In the next section, we present how we selected relevant papers and how we analyzed them through text mining and social network analysis. We then illustrate the importance of 27 selected research topics, measured by means of the SBS indicator. In the results section, we present an overview of the literature based on the SBS results–followed by an in-depth narrative analysis of the top 10 topics (i.e., those with the highest SBS) and their connections. Subsequently, we highlight a series of under-studied connections between the topics where there is potential for future research. Through this analysis, we build a map of the main gender-research trends in the last twenty-two years–presenting the most popular themes. We conclude by highlighting key areas on which research should focused in the future.

Our aim is to map a broad topic, gender equality research, that has been approached through a host of different angles and through different disciplines. Scoping reviews are the most appropriate as they provide the freedom to map different themes and identify literature gaps, thereby guiding the recommendation of new research agendas [ 38 ].

Several practical approaches have been proposed to identify and assess the underlying topics of a specific field using big data [ 39 – 41 ], but many of them fail without proper paper retrieval and text preprocessing. This is specifically true for a research field such as the gender-related one, which comprises the work of scholars from different backgrounds. In this section, we illustrate a novel approach for the analysis of scientific (gender-related) papers that relies on methods and tools of social network analysis and text mining. Our procedure has four main steps: (1) data collection, (2) text preprocessing, (3) keywords extraction and classification, and (4) evaluation of semantic importance and image.

Data collection

In this study, we analyze 22 years of literature on gender-related research. Following established practice for scoping reviews [ 42 ], our data collection consisted of two main steps, which we summarize here below.

Firstly, we retrieved from the Scopus database all the articles written in English that contained the term “gender” in their title, abstract or keywords and were published in a journal listed in the Academic Journal Guide 2018 ranking of the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) ( https://charteredabs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/AJG2018-Methodology.pdf ), considering the time period from Jan 2000 to May 2021. We used this information considering that abstracts, titles and keywords represent the most informative part of a paper, while using the full-text would increase the signal-to-noise ratio for information extraction. Indeed, these textual elements already demonstrated to be reliable sources of information for the task of domain lexicon extraction [ 43 , 44 ]. We chose Scopus as source of literature because of its popularity, its update rate, and because it offers an API to ease the querying process. Indeed, while it does not allow to retrieve the full text of scientific articles, the Scopus API offers access to titles, abstracts, citation information and metadata for all its indexed scholarly journals. Moreover, we decided to focus on the journals listed in the AJG 2018 ranking because we were interested in reviewing business and economics related gender studies only. The AJG is indeed widely used by universities and business schools as a reference point for journal and research rigor and quality. This first step, executed in June 2021, returned more than 55,000 papers.

In the second step–because a look at the papers showed very sparse results, many of which were not in line with the topic of this literature review (e.g., papers dealing with health care or medical issues, where the word gender indicates the gender of the patients)–we applied further inclusion criteria to make the sample more focused on the topic of this literature review (i.e., women’s gender equality issues). Specifically, we only retained those papers mentioning, in their title and/or abstract, both gender-related keywords (e.g., daughter, female, mother) and keywords referring to bias and equality issues (e.g., equality, bias, diversity, inclusion). After text pre-processing (see next section), keywords were first identified from a frequency-weighted list of words found in the titles, abstracts and keywords in the initial list of papers, extracted through text mining (following the same approach as [ 43 ]). They were selected by two of the co-authors independently, following respectively a bottom up and a top-down approach. The bottom-up approach consisted of examining the words found in the frequency-weighted list and classifying those related to gender and equality. The top-down approach consisted in searching in the word list for notable gender and equality-related words. Table 1 reports the sets of keywords we considered, together with some examples of words that were used to search for their presence in the dataset (a full list is provided in the S1 Text ). At end of this second step, we obtained a final sample of 15,465 relevant papers.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474.t001

Text processing and keyword extraction

Text preprocessing aims at structuring text into a form that can be analyzed by statistical models. In the present section, we describe the preprocessing steps we applied to paper titles and abstracts, which, as explained below, partially follow a standard text preprocessing pipeline [ 45 ]. These activities have been performed using the R package udpipe [ 46 ].

The first step is n-gram extraction (i.e., a sequence of words from a given text sample) to identify which n-grams are important in the analysis, since domain-specific lexicons are often composed by bi-grams and tri-grams [ 47 ]. Multi-word extraction is usually implemented with statistics and linguistic rules, thus using the statistical properties of n-grams or machine learning approaches [ 48 ]. However, for the present paper, we used Scopus metadata in order to have a more effective and efficient n-grams collection approach [ 49 ]. We used the keywords of each paper in order to tag n-grams with their associated keywords automatically. Using this greedy approach, it was possible to collect all the keywords listed by the authors of the papers. From this list, we extracted only keywords composed by two, three and four words, we removed all the acronyms and rare keywords (i.e., appearing in less than 1% of papers), and we clustered keywords showing a high orthographic similarity–measured using a Levenshtein distance [ 50 ] lower than 2, considering these groups of keywords as representing same concepts, but expressed with different spelling. After tagging the n-grams in the abstracts, we followed a common data preparation pipeline that consists of the following steps: (i) tokenization, that splits the text into tokens (i.e., single words and previously tagged multi-words); (ii) removal of stop-words (i.e. those words that add little meaning to the text, usually being very common and short functional words–such as “and”, “or”, or “of”); (iii) parts-of-speech tagging, that is providing information concerning the morphological role of a word and its morphosyntactic context (e.g., if the token is a determiner, the next token is a noun or an adjective with very high confidence, [ 51 ]); and (iv) lemmatization, which consists in substituting each word with its dictionary form (or lemma). The output of the latter step allows grouping together the inflected forms of a word. For example, the verbs “am”, “are”, and “is” have the shared lemma “be”, or the nouns “cat” and “cats” both share the lemma “cat”. We preferred lemmatization over stemming [ 52 ] in order to obtain more interpretable results.

In addition, we identified a further set of keywords (with respect to those listed in the “keywords” field) by applying a series of automatic words unification and removal steps, as suggested in past research [ 53 , 54 ]. We removed: sparse terms (i.e., occurring in less than 0.1% of all documents), common terms (i.e., occurring in more than 10% of all documents) and retained only nouns and adjectives. It is relevant to notice that no document was lost due to these steps. We then used the TF-IDF function [ 55 ] to produce a new list of keywords. We additionally tested other approaches for the identification and clustering of keywords–such as TextRank [ 56 ] or Latent Dirichlet Allocation [ 57 ]–without obtaining more informative results.

Classification of research topics

To guide the literature analysis, two experts met regularly to examine the sample of collected papers and to identify the main topics and trends in gender research. Initially, they conducted brainstorming sessions on the topics they expected to find, due to their knowledge of the literature. This led to an initial list of topics. Subsequently, the experts worked independently, also supported by the keywords in paper titles and abstracts extracted with the procedure described above.

Considering all this information, each expert identified and clustered relevant keywords into topics. At the end of the process, the two assignments were compared and exhibited a 92% agreement. Another meeting was held to discuss discordant cases and reach a consensus. This resulted in a list of 27 topics, briefly introduced in Table 2 and subsequently detailed in the following sections.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474.t002

Evaluation of semantic importance

Working on the lemmatized corpus of the 15,465 papers included in our sample, we proceeded with the evaluation of semantic importance trends for each topic and with the analysis of their connections and prevalent textual associations. To this aim, we used the Semantic Brand Score indicator [ 36 ], calculated through the SBS BI webapp [ 37 ] that also produced a brand image report for each topic. For this study we relied on the computing resources of the ENEA/CRESCO infrastructure [ 58 ].

The Semantic Brand Score (SBS) is a measure of semantic importance that combines methods of social network analysis and text mining. It is usually applied for the analysis of (big) textual data to evaluate the importance of one or more brands, names, words, or sets of keywords [ 36 ]. Indeed, the concept of “brand” is intended in a flexible way and goes beyond products or commercial brands. In this study, we evaluate the SBS time-trends of the keywords defining the research topics discussed in the previous section. Semantic importance comprises the three dimensions of topic prevalence, diversity and connectivity. Prevalence measures how frequently a research topic is used in the discourse. The more a topic is mentioned by scientific articles, the more the research community will be aware of it, with possible increase of future studies; this construct is partly related to that of brand awareness [ 59 ]. This effect is even stronger, considering that we are analyzing the title, abstract and keywords of the papers, i.e. the parts that have the highest visibility. A very important characteristic of the SBS is that it considers the relationships among words in a text. Topic importance is not just a matter of how frequently a topic is mentioned, but also of the associations a topic has in the text. Specifically, texts are transformed into networks of co-occurring words, and relationships are studied through social network analysis [ 60 ]. This step is necessary to calculate the other two dimensions of our semantic importance indicator. Accordingly, a social network of words is generated for each time period considered in the analysis–i.e., a graph made of n nodes (words) and E edges weighted by co-occurrence frequency, with W being the set of edge weights. The keywords representing each topic were clustered into single nodes.

The construct of diversity relates to that of brand image [ 59 ], in the sense that it considers the richness and distinctiveness of textual (topic) associations. Considering the above-mentioned networks, we calculated diversity using the distinctiveness centrality metric–as in the formula presented by Fronzetti Colladon and Naldi [ 61 ].

Lastly, connectivity was measured as the weighted betweenness centrality [ 62 , 63 ] of each research topic node. We used the formula presented by Wasserman and Faust [ 60 ]. The dimension of connectivity represents the “brokerage power” of each research topic–i.e., how much it can serve as a bridge to connect other terms (and ultimately topics) in the discourse [ 36 ].

The SBS is the final composite indicator obtained by summing the standardized scores of prevalence, diversity and connectivity. Standardization was carried out considering all the words in the corpus, for each specific timeframe.

This methodology, applied to a large and heterogeneous body of text, enables to automatically identify two important sets of information that add value to the literature review. Firstly, the relevance of each topic in literature is measured through a composite indicator of semantic importance, rather than simply looking at word frequencies. This provides a much richer picture of the topics that are at the center of the discourse, as well as of the topics that are emerging in the literature. Secondly, it enables to examine the extent of the semantic relationship between topics, looking at how tightly their discourses are linked. In a field such as gender equality, where many topics are closely linked to each other and present overlaps in issues and solutions, this methodology offers a novel perspective with respect to traditional literature reviews. In addition, it ensures reproducibility over time and the possibility to semi-automatically update the analysis, as new papers become available.

Overview of main topics

In terms of descriptive textual statistics, our corpus is made of 15,465 text documents, consisting of a total of 2,685,893 lemmatized tokens (words) and 32,279 types. As a result, the type-token ratio is 1.2%. The number of hapaxes is 12,141, with a hapax-token ratio of 37.61%.

Fig 1 shows the list of 27 topics by decreasing SBS. The most researched topic is compensation , exceeding all others in prevalence, diversity, and connectivity. This means it is not only mentioned more often than other topics, but it is also connected to a greater number of other topics and is central to the discourse on gender equality. The next four topics are, in order of SBS, role , education , decision-making , and career progression . These topics, except for education , all concern women in the workforce. Between these first five topics and the following ones there is a clear drop in SBS scores. In particular, the topics that follow have a lower connectivity than the first five. They are hiring , performance , behavior , organization , and human capital . Again, except for behavior and human capital , the other three topics are purely related to women in the workforce. After another drop-off, the following topics deal prevalently with women in society. This trend highlights that research on gender in business journals has so far mainly paid attention to the conditions that women experience in business contexts, while also devoting some attention to women in society.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474.g001

Fig 2 shows the SBS time series of the top 10 topics. While there has been a general increase in the number of Scopus-indexed publications in the last decade, we notice that some SBS trends remain steady, or even decrease. In particular, we observe that the main topic of the last twenty-two years, compensation , is losing momentum. Since 2016, it has been surpassed by decision-making , education and role , which may indicate that literature is increasingly attempting to identify root causes of compensation inequalities. Moreover, in the last two years, the topics of hiring , performance , and organization are experiencing the largest importance increase.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474.g002

Fig 3 shows the SBS time trends of the remaining 17 topics (i.e., those not in the top 10). As we can see from the graph, there are some that maintain a steady trend–such as reputation , management , networks and governance , which also seem to have little importance. More relevant topics with average stationary trends (except for the last two years) are culture , family , and parenting . The feminine topic is among the most important here, and one of those that exhibit the larger variations over time (similarly to leadership ). On the other hand, the are some topics that, even if not among the most important, show increasing SBS trends; therefore, they could be considered as emerging topics and could become popular in the near future. These are entrepreneurship , leadership , board of directors , and sustainability . These emerging topics are also interesting to anticipate future trends in gender equality research that are conducive to overall equality in society.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474.g003

In addition to the SBS score of the different topics, the network of terms they are associated to enables to gauge the extent to which their images (textual associations) overlap or differ ( Fig 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474.g004

There is a central cluster of topics with high similarity, which are all connected with women in the workforce. The cluster includes topics such as organization , decision-making , performance , hiring , human capital , education and compensation . In addition, the topic of well-being is found within this cluster, suggesting that women’s equality in the workforce is associated to well-being considerations. The emerging topics of entrepreneurship and leadership are also closely connected with each other, possibly implying that leadership is a much-researched quality in female entrepreneurship. Topics that are relatively more distant include personality , politics , feminine , empowerment , management , board of directors , reputation , governance , parenting , masculine and network .

The following sections describe the top 10 topics and their main associations in literature (see Table 3 ), while providing a brief overview of the emerging topics.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474.t003

Compensation.

The topic of compensation is related to the topics of role , hiring , education and career progression , however, also sees a very high association with the words gap and inequality . Indeed, a well-known debate in degrowth economics centers around whether and how to adequately compensate women for their childbearing, childrearing, caregiver and household work [e.g., 30 ].

Even in paid work, women continue being offered lower compensations than their male counterparts who have the same job or cover the same role [ 64 – 67 ]. This severe inequality has been widely studied by scholars over the last twenty-two years. Dealing with this topic, some specific roles have been addressed. Specifically, research highlighted differences in compensation between female and male CEOs [e.g., 68 ], top executives [e.g., 69 ], and boards’ directors [e.g., 70 ]. Scholars investigated the determinants of these gaps, such as the gender composition of the board [e.g., 71 – 73 ] or women’s individual characteristics [e.g., 71 , 74 ].

Among these individual characteristics, education plays a relevant role [ 75 ]. Education is indeed presented as the solution for women, not only to achieve top executive roles, but also to reduce wage inequality [e.g., 76 , 77 ]. Past research has highlighted education influences on gender wage gaps, specifically referring to gender differences in skills [e.g., 78 ], college majors [e.g., 79 ], and college selectivity [e.g., 80 ].

Finally, the wage gap issue is strictly interrelated with hiring –e.g., looking at whether being a mother affects hiring and compensation [e.g., 65 , 81 ] or relating compensation to unemployment [e.g., 82 ]–and career progression –for instance looking at meritocracy [ 83 , 84 ] or the characteristics of the boss for whom women work [e.g., 85 ].