Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Teaching and Learning English Grammar: Research Findings and Future Directions - 2015 - Front matter and Table of Contents

Christison, M.A., Christian, D., Duff, P., & Spada, N. (Eds.). (2015). Teaching and learning English grammar: Research findings and future directions. New York: Routledge. ABSTRACT An important contribution to the emerging body of research-based knowledge about English grammar, this volume presents empirical studies along with syntheses and overviews of previous and ongoing work on the teaching and learning of grammar for learners of English as a second/foreign language. A variety of approaches are explored, including form-focused instruction, content and language integration, corpus-based lexicogrammatical approaches, and social perspectives on grammar instruction.... You'll find the (draft) chapter by Duff, Ferreira & Zappa-Hollman under 'Articles' on this site. TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword --Joanne Dresner Preface --MaryAnn Christison, Donna Christian, Patricia A. Duff, and Nina Spada Part I. Overview of English grammar instruction Chapter 1. An overview of teaching grammar in ELT --Marianne Celce-Murcia Part II. Focus on form in second language acquisition Chapter 2. Focus on form: Addressing grammatical accuracy in an occupation-specific language program --Antonella Valeo Chapter 3. Teaching English grammar in context: The timing of form-focused intervention --Junko Hondo Chapter 4. Form-focused instruction and learner investment: Case study of a high school student in Japan ---Yasuyo Tomita Chapter 5: The influence of pretask instructions and pretask planning on focus on form during Korean EFL task-based interaction --Sujung Park Part III. The use of technology in teaching grammar Chapter 6. The role of corpus research in the design of advanced level grammar instruction --Michael J. McCarthy Chapter 7. Corpus-based lexicogrammatical approach to grammar instruction: Its use and effects in EFL and ESL contexts --Dilin Liu and Ping Jiang Chapter 8. Creating corpus-based vocabulary lists for two verb tenses: A lexicogrammar approach --Keith S. Folse Part IV. Instructional design and grammar Chapter 9. Putting (functional) grammar to work in content-based English for academic purposes instruction --Patricia A. Duff, Alfredo A. Ferreira, and Sandra Zappa-Hollman Chapter 10. Integrating grammar in adult TESOL classrooms --Anne Burns and Simon Borg Chapter 11. Teacher and learner preferences for integrated and isolated form-focused instruction --Nina Spada and Marília dos Santos Lima Chapter 12. Form-focused approaches to learning, teaching, and researching grammar --Rod Ellis Epilogue --Kathleen M. Bailey

Related Papers

The Canadian Modern Language Review / La revue canadienne des langues vivantes

Patricia (Patsy) Duff

Duff, P., Ferreira, A., & Zappa-Hollman, S. (2015). In M. Christison, D. Christian, P. Duff & N. Spada (Eds.), Teaching and learning English grammar: Research findings and future directions (pp.139-158). New York: Routledge. ABSTRACT A growing body of curriculum development, instruction, and research focuses on ways of attending to grammar systematically in content-based academic English programs (Coffin, 2010). This work examines the functions of the grammatical structures to be learned to express particular meanings in oral and written texts within and beyond sentences in authentic discourse contexts (Derewianka & Jones, 2012). Content areas in which explicit grammatical instruction has been integrated successfully include social studies, history, geography, English, and mathematics in K-12 and higher education programs (e.g., Christie, 2004; Mohan, 1986; Schleppegrell, Achugar & Oteíza, 2004). In this chapter, we first discuss the changing contexts for the teaching of English grammar across educational programs and curriculum worldwide, particularly with relatively advanced learners engaged in English-medium instruction (i.e., content and language integrated learning). Next, we discuss traditional approaches to grammar instruction and research and then review some promising functional approaches being taken up by language educators and content specialists in the US, Australia, and other countries, and at our own institution in Canada. We provide theoretical and research foundations and examples of the implementation and effectiveness of such approaches to the teaching and learning of (discourse) grammar by examining nominalization and grammatical metaphor, for example. We conclude by discussing some implications of developments in this area for teacher education--for language instructors, teacher educators, and content specialists--as well as for program development and future research on grammar instruction.

Ali Umar Fagge

Tesol Quarterly

TESL Canada Journal

Ayşe S Akyel

This article examines a number of adult ESL grammar textbooks via an author designed checklist to analyze how well they incorporate the findings from research in communicative language teaching (CLT) and in form1ocused instruction (FFI). It concludes that although a few textbooks incorporate some of the research findings in CLT and FFI, they are not necessarily those chosen by the teaching institutions.

LiBRI. Linguistic and Literary Broad Research and Innovation

Academia EduSoft

The present paper reports on a study that was carried out to compare the effectiveness of three instructional techniques, namely dialogues, focused tasks, and games on teaching grammar. The participants were 48 pre-intermediate EFL students that formed three experimental groups. A posttest consisting of 20 productive items was administered at the end of the treatment period which lasted for four sessions. The results revealed no statistically significant difference between the three groups. This suggests that the three instructional techniques had relatively the same effect on the accurate grammatical production of the learners.

Annual Review of Applied Linguistics

Hossein Nassaji

Andrew Schenck

Schenck, Andrew. An Investigation of the Relationship Between Grammar Type and Efficacy of Form-Focused Instruction. The New Studies of English Language & Literature 69 (2018): 223-248. Because phonological, semantic, and morphosyntactic characteristics of grammatical features can have a significant impact on form-focused instruction, utilization of different grammatical features to test new language teaching techniques may conflate determinations of efficacy or inefficacy. The purpose of this study was to holistically examine different types of instruction, comparing them with grammatical features to evaluate effectiveness. Forty-six experimental studies of form-focused instruction were selected for study. Comparison of effect sizes suggests that the efficacy of form-focused instruction differs considerably based upon the type of grammatical feature targeted. Input-based instruction (e.g.,input enhancement or explicit rule presentation) appears more useful for features like the plural -s, past -ed, and third person singular -s, which are phonologically insalient, yet morphologically regular. Output-based instruction (e.g., corrective feedback or recasts), in contrast, appears more effective with grammatical features such as questions, phrasal verbs, conditionals, and articles, which are syntactically or semantically complex. Overall, the results suggest that differences in grammar be considered before curricula or pedagogical interventions are designed. (State University of New York, Korea)

International Journal of English Language Teaching

This paper unravels aspects of English grammar to be reinforced in the teaching of English as a second or foreign language. The data sources for the study are the following: the broad corpus which consists of 392 BEPC exam essays (2014 and 2015), 46 class test essays (15 in 2016, 15 in 2017 and 16 in 2018) and the narrow corpus which consists of a series of ten (10) designed tests altogether intended for 100 Troisieme class pupils (administered in 2019). The framework used for this study is the Communicative Effect Taxonomy in error analysis as developed by Hendrickson (1976). Findings revealed that Troisieme pupils' English is strewn with global errors, local errors and ambiguous errors. Actually, 20 global error types (including the choice of the wrong auxiliary), 14 local error types (including the V-ed form attached to irregular verbs) and 9 types of ambiguous errors (including the use of the preposition 'at' in place of 'about') were identified in the broad corpus and highlighted in the narrow corpus. By doing so, Troisieme pupils' communicative proficiency as well as their linguistic proficiency was found to be low, and their communicative proficiency was found to be lower than their linguistic proficiency. From the above aspects of English grammar to be reinforced in the teaching of English as a second or foreign language were unveiled. The essence of it all is to improve communicative and linguistic proficiency in English.

Hilal Peker

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- CAL Solutions

- Annual Reports

- Professional Development

Adult Literacy and Language Education

Dual Language and Multilingual Education

Immigrants and Newcomers

International Language Education

PreK-12 EL Education

Testing and Assessment

World Languages

- Resource Archive

Publications & Products

Teaching and learning english grammar: research findings and future directions.

Edited by MaryAnn Christison, Donna Christian, Patricia A. Duff, and Nina Spada Published by Routledge and the International Research Foundation for English Language Education ( TIRF )

An important contribution to the emerging body of research-based knowledge about English grammar, this volume presents empirical studies along with syntheses and overviews of previous and ongoing work on the teaching and learning of grammar for learners of English as a second/foreign language. It explores a variety of approaches, including form-focused instruction, content and language integration, corpus-based lexicogrammatical approaches, and social perspectives on grammar instruction.

Nine chapter authors are Priority Research Grant or Doctoral Dissertation Grant awardees from The International Research Foundation for English Language Education (TIRF), and four overview chapters are written by well-known experts in English language education. Each research chapter addresses issues that motivated the research, the context of the research, data collection and analysis, findings and discussion, and implications for practice, policy, and future research. The TIRF-sponsored research was made possible by a generous gift from Betty Azar. This book honors her contributions to the field and recognizes her generosity in collaborating with TIRF to support research on English grammar.

Teaching and Learning English Grammar is the second volume in the Global Research on Teaching and Learning English Series, co-published by Routledge and TIRF. 2015 236 pages

Order online from the publisher website . Enter code AF001 at checkout to receive a 20% discount.

- Employee Resources

- Permissions

- Privacy Policy

Powered by World Data Inc.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Key Concepts

- The View From Here

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About ELT Journal

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Graham Burton, Grammar, ELT Journal , Volume 74, Issue 2, April 2020, Pages 198–201, https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccaa004

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Most English language teachers are probably comfortable using the word ‘grammar’. There is an established grammatical tradition within ELT, and terms such as ‘tense’, ‘conditional form’, or ‘defining relative clause’ are likely to be familiar even to relatively inexperienced teachers. Grammar is often thought of as something reliable and predictable, but although the term is a keyword in the ELT profession, it is somewhat under-examined. A look at the word’s history reveals a perhaps surprising amount of variation and inconsistency.

The word ‘grammar’ comes originally from Ancient Greek grammatike (‘pertaining to letters/written language’). Grammar was one of the ‘liberal arts’ taught in Ancient Greece, and in Rome from around the fifth century BC, although at this time it was a wider area of study than today, including textual and aesthetic criticism and literary history. Its study continued in Europe in medieval times and beyond, with grammar being taught at schools alongside logic and rhetoric in what was known as the ‘trivium’. The tradition of studying the grammar of English in British schools did not emerge until the 16th century ( Howatt with Widdowson 2004 : 77)—until then, studying grammar at school meant studying Latin or Ancient Greek, not vernacular languages. Indeed, the first grammar of English, Bullokar’s Pamphlet for Grammar (1586), is said to have been written to demonstrate that the English language was in fact rule-based and could be analysed in the same way as Latin ( Linn 2006 : 74). Grammar has lost its status as a distinct subject in the school curriculum but the word has continued (since 1530 according to the Oxford English Dictionary ) to be used as a countable noun meaning ‘a book describing the grammar of a language’.

‘Grammar’ has, of course, also come to refer to the actual ‘structure of a language and the way in which linguistic units such as words and phrases are combined to produce sentences in the language’ ( Richards and Schmidt 2002 : 230), not just to a description of these properties. Yet, even today, the word means different things to different people. One common division is that made between descriptive and prescriptive grammar, with the former describing usage, and the latter attempting to influence it. Within linguistics, there are many approaches to the analysis of the grammar of a language, including Noam Chomsky’s transformational grammar and Michael Halliday’s systemic functional grammar. Mentalists in the Chomskyan tradition strive to explain the internal rule-based system by means of which speakers produce grammatical sentences, whereas Hallidayans, by contrast, look to external, social factors and explore how these shape the choices speakers make. Nevertheless, within ELT, there tends to be quite a strong agreement on what the grammar of English consists of; a brief examination of the contents pages of coursebooks and well-known learner grammars (e.g. Murphy 2012 ; Azar and Hagen 2016 ; Swan 2016 ) reveals coverage of the same familiar areas, such as tenses, articles, relative clauses, and modal verbs.

The sum of these areas can be said to constitute a pedagogical grammar for English, that is to say, a description of language devised specifically for those learning English as a second or foreign language. Pedagogical grammar does not attempt to offer a comprehensive account of the structure of a language; instead it focuses specifically on areas of language deemed likely to be most useful to learners. Here it is worth highlighting Williams’s (1994) distinction between ‘constitutive’ and ‘communicative’ grammar rules. For example, word order in affirmative and interrogative sentences or the - s present simple third-person verb endings are examples of ‘constitutive grammar’; these are structures or forms that learners must simply learn as such. By contrast, an example of a ‘communicative’ grammar rule is the choice between ‘I went to’ and ‘I’ve been to’: these are both formally correct, and a learner needs to know when to use one rather than the other. Both types of rule are important for foreign language learners, but older grammars tended to favour the former and neglect the latter.

Our contemporary pedagogical grammar of English is therefore one of many possible ‘grammars’ of English, reflecting a consensus that started to evolve in the 20th century, driven by a burst of activity in the first half of the century, with individual, often non-native speaker teacher-authors 1 around the world deciding which areas of grammar should be prioritized. What seems now an obvious point—that learners of English need grammatical explanations written specifically for them—was once an innovation; thus, W. Stannard Allen, in the introduction to the seminal Living English Structure , laments that ‘a large number of [grammar books] that are intended for foreigners have not managed to free themselves entirely from the purely analytical point of view’ of traditional school grammars ( Allen 1947/1959 : vii). In this period, many well-known content points in ELT grammar emerged, e.g. much-expanded coverage of future forms (giving going to and present continuous equal importance to will and shall ), and the three-way conditional system (first found in Allen’s grammar). The consensus on ELT grammar content that emerged, especially in materials produced by UK publishers, was added to as the century progressed, under the influence, in particular, of functional and notional descriptions (e.g. Wilkins 1976 ), discourse analysis (e.g. Halliday and Hasan 1976 ), and, to a more limited extent, spoken grammar (e.g. Carter and McCarthy 1995 ). Arguably, however, the foundations established in the first half of the century remained unshaken, and publishers and teachers appear reluctant to deviate from the well-established consensus ( O’Keeffe and Mark 2017 ; Burton 2019 ).

While ELT pedagogical grammar might be argued to be robust in the sense that it is tried and tested, its contents do not appear to have been arrived at in a systematic way. The current consensus is strong and thus difficult to challenge; however, recent research, including that using learner corpora, has begun to call into question both the choice and treatment of grammar points (see, for example, Barbieri and Eckhardt 2007 ; Jones and Waller 2011 ; McCarthy 2015 ), and the levels (beginner, intermediate, advanced, etc.) to which they are assigned ( Mark and O’Keeffe 2016 ; Burton 2019 ). Can we be sure that the tradition we have inherited truly reflects what learners need to know? Will, or indeed should, the consensus be updated to take account of different features that have been identified in grammars of World Englishes ( Davis 2006 ) and English as a lingua franca ( Ranta 2017 )? And, finally, to what extent and how—if at all—will emerging notions of grammar as a complex, ‘perpetually dynamic’ system ( Larsen-Freeman 2012 : 76) characterized by temporal as well as spatial variation come to challenge the received notions that have, so far, stood the test of time in ELT? Final version received January 2020

Including, in the first half of the 20th century, Otto Jespersen (1860–1943), Etsko Kruisinga (1875–1924), Harold E. Palmer (1877–1949), A. S. Hornby (1898–1978) and W. Stannard Allen (1913–1996?).

Allen , W. S . 1947/1959 . Living English Structure . London : Longman .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Azar , B. S. and Hagen , S. A . 2016 . Understanding and Using English Grammar (Fifth edition). New York : Pearson Education .

Barbieri , F. and Eckhardt , S. E. B . 2007 . ‘Applying corpus-based findings to form-focused instruction: the case of reported speech’ . Language Teaching Research 11 / 3 : 319 – 46 .

Burton , G . 2019 . The Canon of Pedagogical Grammar for ELT: A Mixed Methods Study of its Evolution, Development and Comparison with Evidence on Learner Output . Unpublished PhD thesis. Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick . Available at https://dspace.mic.ul.ie/handle/10395/2891 .

Carter , R. and McCarthy , M . 1995 . ‘Grammar and the spoken language’ . Applied Linguistics 16 ( 2 ): 141 – 58 .

Davis , D. R . 2006 . ‘World Englishes and descriptive grammars’ in B. Kachru , Y. Kachru and C. Nelson (eds.). The Handbook of World Englishes , 509 – 25 . Oxford : Blackwell .

Halliday , M. A. K. and Hasan , R . 1976 . Cohesion in English . London : Routledge .

Howatt , A. P. R. with Widdowson , H. G . 2004 . A History of English Language Teaching (Second edition). Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Jones , C. and Waller , D . 2011 . ‘If only it were true: the problem with the four conditionals’ . ELT Journal 65 / 1 : 24 – 32 .

Larsen-Freeman , D . 2012 . ‘Complexity Theory’ in S. M. Gass and A. Mackey (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition, 73 – 87 . Oxford : Routledge .

Linn , A . 2006 . ‘English grammar writing’ in B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.). The Handbook of English Linguistics , 72 – 92 . Oxford : Blackwell .

Mark , G. and O’Keeffe , A . 2016 . ‘Using English Grammar Profile to improve curriculum design’ in Proceedings of the 50th Annual IATEFL Conference , Birmingham, UK , 14 April, 2016 .

McCarthy , M . 2015 . ‘The role of corpus research in the design of advanced level grammar instruction’ in M. Christison et al. . (eds.). Teaching and Learning English Grammar: Research Findings and Future Directions , 87 – 102 . New York : Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group .

Murphy , R . 2012 . English Grammar in Use: A Reference and Practice Book for Intermediate Learners of English Without Answers (Fourth edition). Cambridge : Cambridge University Press .

O’Keeffe , A. and Mark , G . 2017 . ‘The English Grammar Profile of learner competence’, International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 22 / 4 : 457 – 89 .

Ranta , E . 2017 . ‘Grammar in ELF’ in J. Jenkins , W. Baker and M. Dewey (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of English as a Lingua Franca , 244 – 54 . Oxford : Routledge .

Richards , J. C. and Schmidt , R. W . 2002 . Longman Dictionary of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics (Third edition). London : Longman .

Swan , M . 2016 . Practical English Usage (Fourth edition). Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Wilkins , D. A . 1976 . Notional Syllabuses: A Taxonomy and its Relevance to Foreign Language Curriculum Development . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Williams , E . 1994 . ‘English grammar and the views of English teachers’ in M. Bygate , A. Tonkyn and E. Williams (eds.). Grammar and the Language Teacher , 105 – 18 . New York : Prentice Hall .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-4526

- Print ISSN 0951-0893

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

English for Academic Research: Grammar, Usage and Style

- © 2023

- Latest edition

- Adrian Wallwork 0

Pisa, Italy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Ideal study-guide for universities and research institutes

- Acts as a tool for improving English language skills

- Provides supplementary material

Part of the book series: English for Academic Research (EAR)

9731 Accesses

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (18 chapters)

Front matter, abbreviations, acronyms, and punctuation.

Adrian Wallwork

Adverbs and prepositions

Articles: a / an / the / zero article, genitive: the possessive form of nouns, infinitive versus gerund ( -ing form), measurements and numbers, abbreviations, symbols, comparisons, use of articles, modal verbs: can, may, could, should, must etc., nouns: countable vs uncountable, plurals, personal pronouns, names, titles, proofreading tools: checking the correctness of your english, quantifiers: any, some, much, many, much, each, every etc., readability, tenses: present and past, tenses: future, conditional, passive, translation, chatgpt and generative ai, back matter.

- English Grammar

- English Language Learners

- English for Research

About this book

This guide draws on English-related errors from around 6000 papers written by non-native authors, 500 abstracts written by PhD students, and over 2000 hours of teaching researchers how to write and present research papers.

This new edition has chapters on exploiting AI tools such as ChatGPT, Google Translate, and Reverso, for generating, paraphrasing, translating and correcting texts written in English. It also deals with contemporary issues such as the use of gender pronouns.

Due to its focus on the specific errors that repeatedly appear in papers written by non-native authors, this manual is an ideal study guide for use in universities and research institutes. Such errors are related to the usage of articles, countable vs. uncountable nouns, tenses, modal verbs, active vs. passive form, relative clauses, infinitive vs. -ing form, the genitive, link words, quantifiers, word order, prepositions, acronyms, abbreviations, numbers and measurements, punctuation, and spelling.

Grammar, Vocabulary, and Writing Exercises (three volumes)

100 Tips to Avoid Mistakes in Academic Writing and Presenting

English for Writing Research Papers

English for Presentations at International Conferences

English for Academic Correspondence

English for Interacting on Campus

English for Academic CVs, Resumes, and Online Profiles

English for Academic Research: A Guide for Teachers

Adrian Wallwork is the author of more than 40 English Language Teaching (ELT) and English for Academic Purposes (EAP) textbooks. He has trained several thousand PhD students and researchers from 50 countries to write papers and give presentations. He edits research manuscripts through his own proofreading and editing service.

Authors and Affiliations

About the author, bibliographic information.

Book Title : English for Academic Research: Grammar, Usage and Style

Authors : Adrian Wallwork

Series Title : English for Academic Research

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31517-6

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Education , Education (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2023

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-031-31516-9 Published: 23 September 2023

eBook ISBN : 978-3-031-31517-6 Published: 22 September 2023

Series ISSN : 2625-3445

Series E-ISSN : 2625-3453

Edition Number : 2

Number of Pages : XIII, 232

Number of Illustrations : 49 illustrations in colour

Topics : Language Education , Grammar , Professional & Vocational Education , Syntax

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Research on Grammar

Main navigation.

The late Robert J. Connors once called it "the various bodies of knowledge and prejudice called 'grammar.'" For more on the knowledge part, see below:

Selected Research

Connors, robert j. "grammar in american college composition: an historical overview." the territory of language: linguistics, stylistics, and the teaching of composition. ed. donald a.mcquade. carbondale: southern illinois up, 1986. 3-22..

Robert J. Connors, who co-authored Andrea Lunsford's early research on the frequency of error, also studied the history of English grammar instruction in the United States. When did American schools switch from teaching Latin grammar to teaching English grammar? Who invented and popularized sentence-diagramming? How did the rise of structural linguistics in the 1950s affect ideas about grammar? In his inimitable style, Connors treated these questions and more.

Connors, Robert J., and Andrea A. Lunsford. "Frequency of Formal Errors in Current College Writing, or Ma and Pa Kettle Do Research." College Composition and Communication 39.4 (Dec. 1988): 395-409.

Hartwell, patrick. "grammar, grammars, and the teaching of grammar." college english 47.2 (1985): 105-127..

In this classic essay, Patrick Hartwell offers five definitions of grammar that elucidate the many ways the term gets used: from an internalized set of linguistic rules to a meta-awareness and stylistic choice. His varied definitions suggest the co-existence of multiple literacies that undermine an approach to teaching grammar focused exclusively on correctness.

Lunsford, Andrea A. and Karen J. Lunsford. "'Mistakes Are a Fact of Life': A National Comparative Study." College Composition and Communication 59.4 (Jun. 2008): 781-806.

Stanford's own Andrea Lunsford, Louise Hewett Nixon Professor of English, is a leader in the study of error in writing. Her long-term quantitative research has revealed shifting patterns of error as technologies and rhetorical situations change. Among Professor Lunsford's findings ( summarized in Top 20 form here ):

- Student papers today are longer and more complex than they were 20 years ago, yet there has been no significant increase in the overall rate of error.

- Although word-processing tools have advanced substantially, they are responsible for the most common error in student writing today: using the wrong word, spelled correctly.

Micciche, Laura. "Making a Case for Rhetorical Grammar." College Composition and Communication 55.4 (Jun. 2004): 716-737.

What do you think of when you think of the word "grammar"? Laura Micciche argues most people think of formal grammar: "Usually, our minds go to those unending rules and exceptions, those repetitive drills and worksheets..." (720). This formal grammar is "the deadly kind of grammar," the one that makes us anxious. Drawing on Martha Kolln's idea of "rhetorical grammar," Micciche argues that grammar doesn't have to be deadly: it can give a writer more powerful choices, and thus make writing and communicating more satisfying and more pleasurable.

Williams, Joseph M. "The Phenomenology of Error." College Composition and Communication 32.2 (May 1981): 152-168.

Why do some grammatical errors seem to cause so much venom and rage? Why is a misuse of the word "hopefully" considered an "atrocity"? Joseph M. Williams examined this question in this still-relevant 1981 article. Williams is also the author of Style: Ten Lessons in Clarity and Grace (Longman).

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Grammar: Articles

Articles video.

Note that this video was created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

- Mastering the Mechanics: Articles (video transcript)

Article Basics

What is an article.

- Articles ("a," "an," and "the") are determiners or noun markers that function to specify if the noun is general or specific in its reference. Often the article chosen depends on if the writer and the reader understand the reference of the noun.

- The articles "a" and "an" are indefinite articles. They are used with a singular countable noun when the noun referred to is nonspecific or generic.

- The article "the" is a definite article. It is used to show specific reference and can be used with both singular and plural nouns and with both countable and uncountable nouns.

Many languages do not use articles ("a," "an," and "the"), or if they do exist, the way they are used may be different than in English. Multilingual writers often find article usage to be one of the most difficult concepts to learn. Although there are some rules about article usage to help, there are also quite a few exceptions. Therefore, learning to use articles accurately takes a long time. To master article usage, it is necessary to do a great deal of reading, notice how articles are used in published texts, and take notes that can apply back to your own writing.

To get started, please read this blog post on The Argument for Articles .

A few important definitions to keep in mind:

- one horse, two horses

- one chair, two chairs

- one match, two matches

- one child, two children

- one mouse, two mice

- Information

Please see this webpage for more about countable and uncountable nouns .

"A" or "An"

When to use "a" or "an".

"A" and "an" are used with singular countable nouns when the noun is nonspecific or generic.

- In this sentence, "car " is a singular countable noun that is not specific. It could be any car.

- "University" is a singular countable noun. Although it begins with a vowel, the first sound of the word is /j/ or “y.” Thus, "a" instead of "an" is used. In this sentence, it is also generic (it could be any university with this specialization, not a specific one).

- In this sentence, "apple" is a singular countable noun that is not specific. It could be any apple.

"A" is used when the noun that follows begins with a consonant sound.

- a uniform (Note that "uniform" starts with a vowel, but the first sound is /j/ or a “y” sound. Therefore "a" instead of "an" is used here.)

"An" is used when the noun that follows begins with a vowel sound.

- an elephant

- an American

- an MBA (Note that "MBA" starts with a consonant, but the first sound is /Ɛ/ or a short “e” sound. Therefore, "an" instead of "a" is used here.)

Sometimes "a" or "an" can be used for first mention (the first time the noun is mentioned). Then, in subsequent sentences, the article "the" is used instead.

- In the first sentence (first mention), "a" is used because it is referring to a nonspecified house. In the second sentence, "the" is used because now the house has been specified.

When to Use "The"

"The" is used with both singular and plural nouns and with both countable and uncountable nouns when the noun is specific.

- In this sentence, "book" is a singular, countable noun. It is also specific because of the phrase “that I read last night.” The writer and reader (or speaker and listener) know which book is being referred to.

- In this sentence, "books" is a plural, countable noun. It is also specific because of the phrase “for this class.” The writer and reader (or speaker and listener) know which books are being referred to.

- In this sentence, "advice" is an uncountable noun. However, it is specific because of the phrase “you gave me.” It is clear which piece of advice was helpful.

Here are some more specific rules:

"The" is used in the following categories of proper nouns:

- Museums and art galleries : the Walker Art Center, the Minneapolis Institute of Art

- Buildings : the Empire State Building, the Willis Tower

- Seas and oceans : the Mediterranean Sea, the Atlantic Ocean

- Rivers : the Mississippi, the Nile

- Deserts : the Sahara Desert, the Sonora Desert

- Periods and events in history: the Dark Ages, the Civil War

- Bridges: the London Bridge, the Mackinac Bridge

- Parts of a country : the South, the Upper Midwest

In general, use "the" with plural proper nouns.

- the Great Lakes

- the Rockies (as in the Rocky Mountains)

"The" is often used with proper nouns that include an “of” phrase.

- the United States of America

- the University of Minnesota

- the International Swimming Hall of Fame

Use "the" when the noun being referred to is unique because of our understanding of the world.

- The Earth moves around the sun.

- Wolves howl at the moon.

Use "the" when a noun can be made specific from a previous mention in the text. This is also known as second or subsequent mention.

- My son bought a cat. I am looking after the cat while he is on vacation.

- I read a good book. The book was about how to use articles correctly in English.

"The" is used with superlative adjectives, which are necessarily unique (the first, the second, the biggest, the smallest, the next, the only, etc.).

- It was the first study to address the issue.

- She was the weakest participant.

- He was the only person to drop out of the study.

Biber et al. (1999) found that "the" is about twice as common as "a" or "an" in academic writing. This may be because writers at this level often focus on overall ideas and categories ( generic reference , usually no article) and on specific references (definite reference, the article "the").

- Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., & Finegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of written and spoken English . Pearson.

No Article (Generic Reference)

Writers sometimes struggle with the choice to include an article or to leave it out altogether. Keep in mind that if the noun is singular, countable, and nonspecific or generic (e.g., book, author), the articles "a" and "an" may be used. However, if the noun is countable and plural (e.g.., "research studies") or uncountable (e.g., "information") and it is being used in a nonspecific or generic way, no article is used.

Here are some more specifics:

- I bought new pens and pencils at the store. (general, not specific ones)

- Cats have big eyes that can see in the dark. (cats in general, all of them)

- Babies cry a lot. (babies in general, all of them)

- I bought milk and rice at the store. (generic reference)

- We were assigned homework in this class. (generic reference)

- There has been previous research on the topic. (generic reference)

Articles in Phrases and Idiomatic Expressions

Sometimes article usage in English does not follow a specific rule. These expressions must be memorized instead.

Here are some examples of phrases where article usage is not predictable:

- Destinations: go to the store, go to the bank , but go to school, go to church, go to bed, go home

- Locations: in school, at home, in bed, but in the hospital (in American English)

- Parts of the day: in the morning, in the evening, but at night

- Chores: mow the lawn, do the dishes, do the cleaning

There are also numerous idiomatic expressions in English that contain nouns. Some of these also contain articles while others do not.

Here are just a few examples:

- To give someone a hand

- To be on time

Related Resources

Knowledge Check: Articles

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Noun–Pronoun Agreement

- Next Page: Count and Noncount Nouns

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Incorporating Flipped Model in Learning English Grammar: Exploring EFL Students’ Intrinsic Motivation and Attainment

- Ashwaq A. Aldaghri Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU)

Flipped Classroom (FC) is an educational approach that has gained considerable attention. It incorporates technology to deliver direct instruction outside of class, while in-class time is limited to contextualized collaborative activities. On the other hand, intrinsic motivation (IM) is a fundamental objective for educators, as it helps learners pursue learning throughout the year. It is the internal drive to engage in learning activities for the sake of personal fulfillment and satisfaction. Recognizing the vital role of IM, the paper investigates the efficacy of flipped learning (FL) in raising students’ IM in grammar courses within the framework of Self-Determination Theory (SDT). A total of forty-one (n= 41) Saudi EFL university students were normally distributed into two groups. The experimental group receives FC instruction, while the control group is taught using traditional explicit instruction. A pretest and a posttest were administered to both groups. Furthermore, a questionnaire was further distributed to the experimental group. The findings of the present quasi-experimental study demonstrate that FC enhances students' IM by providing a student-centered, supportive, positive, and collaborative technology-based environment that promotes their language attainment and satisfies their basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Finally, to ensure its successful implementation, it is recommended that teacher training and thorough content planning are vital before implementing FC.

Author Biography

Ashwaq a. aldaghri, imam mohammad ibn saud islamic university (imsiu).

Department of English Language and Literature, College of Languages and Translation

Afzali, Z., & Izadpanah, S. (2021). The effect of the flipped classroom model on Iranian English foreign language learners: Engagement and motivation in English language grammar. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1-37.

Aldaghri, A. A. (2023). Flipped Instruction in Teaching Grammar: Is it Worth Trying? IMSIU Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 1445(69).

Alharbi, S. & Alshumaimeri, Y. (2016). The Flipped Classroom Impact in Grammar Class on EFL Saudi Secondary School Students’ Performances and Attitudes. English Language Teaching, 9(10), 60-80.

Al-Naabi, I. S. (2020). Is It Worth Flipping? The Impact of Flipped Classroom on EFL Students' Grammar. English Language Teaching, 13(6), 64-75.

Al-Osaimi, D. N., & Fawaz, M. (2022). Nursing students' perceptions on motivation strategies to enhance academic achievement through blended learning: A qualitative study. Heliyon, 8(7), 1-7.

Alotebi, H. (2016). Enhancing the motivation of foreign language learners through blended learning. International journal of advanced research in education & technology, 3(2), 51-55.

Bezzazi, R. (2019). Learning English grammar through FL. The Asian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 6(2), 170-184.

Busse, V., & Walter, C. (2013). Foreign language learning motivation in higher education: A longitudinal study of motivational changes and their causes. The modern language journal, 97(2), 435-456.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., (1985). Conceptualizations of intrinsic motivation and self-determination. Perspectives in Social Psychology. Springer, 11-40.

Ebata, M. (2008). Motivation Factors in Language Learning, The Internet TESL Journal. XIV(4).

Ibrahim, A. A., Ahmed Ali, A., Al-mehsin, S. A., & Alipour, P. (2022). Psychological Factors Affecting Language-Learning Process in Saudi Arabia: The Effect of Technology-Based Education on High School Students’ Motivation, Anxiety, and Attitude through FL. Education Research International, 2022(2022), 1-14.

Ivanytska, N., Dovhan, l., Tymoshchuk, N., Osaulchyk, O.,& Havryliuk, N. (2021). Assessment of Flipped Learning as an Innovative Method of Teaching English: A Case Study. Arab World English Journal, 12(4) 476-486.

Khazaie, Z. M., & Mesbah, Z. (2014). The relationship between extrinsic vs. intrinsic motivation and strategic use of language of Iranian intermediate EFL learners. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4(1), 99-109.

Maherzi, S. (2011). Perceptions of classroom climate and motivation to study English in Saudi Arabia: Developing a questionnaire to measure perceptions and motivation. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology, 9(24), 765-798.

Mai, X. P., & Liu, L. H. (2021). Obstacles and Improvement Strategies in Implementing Flipped Classroom in Colleges: From the Perspective of Self-Determination Theory. Advances in Applied Sociology, 11, 513-521.

Mandasari, B., & Wahyudin, A. Y. (2021). Flipped classroom learning model: implementation and its impact on EFL learners’ satisfaction on grammar class. Ethical Lingua: Journal of Language Teaching and Literature, 8(1), 150-158.

Noels, K. A., Pelletier, L. G., Clément, R., & Vallerand, R. J. (2000). Why are you learning a second language? Motivational orientations and self‐determination theory. Language learning, 50(1), 57-85.

Oraif, I. M. K. (2018). An investigation into the impact of the flipped classroom on intrinsic motivation (IM) and learning outcomes on an EFL writing course at a university in Saudi Arabia based on self-determination theory (SDT) (Doctoral dissertation, University of Leicester).

Oxford, R., & Shearin, J. (1994). Language Learning Motivation: Expanding the Theoretical Framework. Modern Language Journal, 78, 12-28.

Pae, T. I. (2008). Second language orientation and self-determination theory: A structural analysis of the factors affecting second language achievement. Journal of language and social psychology, 27(1), 5-27.

Pudin, C. S. J. (2017). Exploring a Flipped Learning approach in teaching grammar for ESL students. Indonesian Journal of English Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics, 2(1), 51-64.

Shabani, S., & Alipoor, I. (2017). The relationship between cultural identity, intrinsic motivation and pronunciation knowledge of Iranian EFL learners. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 5(2), 61-66.

Sucaromana, U. (2013). The effects of blended learning on the intrinsic motivation of Thai EFL students. English Language Teaching, 6(5), 141-147.

Vaezi, R., Afghari, A., & Lotfi, A. (2019). Flipped teaching: Iranian students’ and teachers’ perceptions. Applied Research on English Language, 8(1), 139-164.

Vallerand, R. J., Fortier, M. S., & Guay, F. (1997). Self-determination and persistence in a real-life setting: Toward a motivational model of high school dropout. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1161-76.

Vuong, N. H. A., Keong, T. C., & Wah, L. K. (2019). The affordances of the flipped classroom approach in English grammar instruction. International Journal of Education, 4(33), 95-106.

Williams, M., & Burden, R. L. (1997). Psychology for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yousofi, N., & Naderifarjad, Z. (2015). The Relationship between Motivation and Pronunciation: A case of Iranian EFL learners. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 2(4), 249-262.

Zhou, H. (2012). Enhancing non-English majors’ EFL motivation through cooperative learning. Procedia environmental sciences, 12, 1317-1323.

Copyright © 2015-2024 ACADEMY PUBLICATION — All Rights Reserved

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue Online Writing Lab

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Online Writing Lab at Purdue University houses writing resources and instructional material, and we provide these as a free service of the Writing Lab at Purdue. Students, members of the community, and users worldwide will find information to assist with many writing projects. Teachers and trainers may use this material for in-class and out-of-class instruction.

The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives. The Purdue OWL offers global support through online reference materials and services.

A Message From the Assistant Director of Content Development

The Purdue OWL® is committed to supporting students, instructors, and writers by offering a wide range of resources that are developed and revised with them in mind. To do this, the OWL team is always exploring possibilties for a better design, allowing accessibility and user experience to guide our process. As the OWL undergoes some changes, we welcome your feedback and suggestions by email at any time.

Please don't hesitate to contact us via our contact page if you have any questions or comments.

All the best,

Social Media

Facebook twitter.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Guardian view on English lessons: make classrooms more creative again

The pleasures of reading and books have been swapped for phonics and grammar. It’s time for change

T oo much of what is valuable about studying English was lost in the educational reforms of the past 14 years. A sharp drop-off in the number of students in England taking the subject at A-level means fewer are taking English degrees . Teaching used to be a popular career choice for literature graduates, as Carol Atherton warmly describes in her new book, Reading Lessons . In it, Ms Atherton, a teacher in Lincolnshire, explains the pleasure she takes in teaching novels such as Jane Eyre that she first encountered herself as a teenage bookworm.

But lower numbers of English graduates mean teacher training courses are struggling to fill places for specialist secondary teaching jobs like hers, making entry less competitive. While trainee English teachers used to be plentiful, compared with subjects such as physics, now recruitment targets are routinely missed .

Changes to the curriculum made under the Conservatives are not the only reason. Chronic workforce shortages afflict much of the public sector, and figures show that schools are following hospitals and care homes in turning to recruitment abroad . A recent report from the National Foundation for Educational Research argued that to boost domestic applications and retention, teachers should be paid bonuses. This would compensate them for not being able to work from home.

But the fall in the popularity of English among over-16s is seen by many as a consequence of ill-thought-through changes, which imposed a model more suited to science and maths learning on to the quite different disciplines of language and literature. A highly prescriptive set of objectives pushes pupils to use ambitious vocabulary and punctuation. But this leaves limited room to encourage imagination, storytelling and interpretation – and the enjoyment in books that is crucial to stimulate a love of books. For Ms Atherton, it was the discovery of ambiguity in literature – the fact that the same texts can mean different things, depending who is reading them – that drew her in.

The researchers behind another book, Dominic Wyse and Charlotte Hacking, share her belief in the power of reading. In The Balancing Act , these authors set out a case that the version of phonics currently taught in primary schools all over the world is overly narrow. While many blame smartphones for the declining popularity of reading among young people, these experts say evidence shows that English lessons themselves bear a share of the blame. They believe a more flexible approach in classrooms, making more use of literature (initially children’s stories and novels) and less focused on grammar, would ultimately produce stronger talkers, readers and writers. The erosion of teachers’ autonomy should also be reversed, if enjoyment in language and ideas is to be strengthened.

There are many other challenges facing schools, which have not received enough support to recover fully from the pandemic. Problems around attendance and the system for pupils with special educational needs and disabilities will be pressing issues for the next government as they are for the current one. But education policy is not all about problem-solving. Schools remain lively places and innovation is essential if institutions and the people in them are to keep abreast of changes in the world. It is time to review the curriculum. When that happens, a fresh look at English, along with the arts subjects wrongly downgraded by the Conservatives , should be top of the list.

- English and creative writing

- Higher education

- Conservatives

- Teacher shortages

Most viewed

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Language transfer in l2 academic writings: a dependency grammar approach.

- 1 Fudan University, Shanghai, China

- 2 Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China

Dependency distance (DD) is an important factor in language processing and can affect the ease with which a sentence is understood. Previous studies have investigated the role of DD in L2 writing, but little is known about how the native language influences DD in L2 academic writing. This study is probably the first one that investigates, though a large dataset of over 400 million words, whether the native language of L2 writers influences the DD in their academic writings. Using a dataset of over 2.2 million abstracts of articles downloaded from Scopus in the fields of Arts & Humanities and Social Sciences, the study analyzes the DD patterns, parsed by the latest version of the syntactic parser Stanford Corenlp 4.5.5, in the academic writing of L2 learners from different language backgrounds. It is found that native languages influence the DD of English L2 academic writings. When the mean dependency distance (MDD) of native languages is much longer than that of native English, the MDD of their English L2 academic writings will be much longer than that of English native academic writings. The findings of this study will deepen our insights into the influence of native language transfer on L2 academic writing, potentially shaping pedagogical strategies in L2 academic writing education.

1 Introduction

Academic writing in a second language (L2) poses many challenges for L2 learners. One important aspect of academic writing quality is syntactic complexity ( Lu, 2011 ), which can be measured by dependency distance (DD)—the linear distance between syntactically related words in a sentence ( Tesnière, 1959 ; Liu, 2007 , 2008 ; Hudson, 2010 ; Liu et al., 2017 , 2022 ). In their exploration of DD, researchers have also examined dependency direction ( Liu et al., 2009 ; Liu, 2010 ; Jiang and Liu, 2015 ; Wang and Liu, 2017 ; Fan and Jiang, 2019 )—a concept that delineates the positional relationship between a governor and its dependent within syntactically connected word pairs, specifically whether the governor appears after or before its dependent. DD has been recognized as a valid measure of syntactic complexity and language comprehension difficulty ( Liu, 2008 ; Oya, 2011 ). Research has found that writers tend to minimize DD in the writings with their native languages ( Temperley, 2007 , 2008 ; Futrell et al., 2015 ; Temperley and Gildea, 2018 ; Lei and Wen, 2019 ; Lu and Liu, 2020 ), resulting in more locally coherent sentences. However, less is known about the DDs of English L2 academic writings and whether the writers’ native languages influence the DD of their L2 academic writings.

This study intends to investigate whether the DDs of English L2 academic writing are affected by the writers’ native languages. Specifically, it compares the DDs of the abstracts of journal articles written by English L2 users and English native speakers. English is found to be different from other languages, like French, Spanish, Korean, and Arabic, in thought patterns and rhetorical structures ( Kaplan, 1966 ), which may impact the DDs in L2 writing. However, L2 writing may also be shaped by universal pressures for efficient processing, driving DDs toward a common optimal range ( Liu et al., 2017 ) (See section 2 for further explanation).

To test these accounts, we analyzed the DDs of English academic writings by English L2 users and native speakers. We extracted the DDs from each text using syntactic parsing and compared the distributions statistically. This allows us to determine if native language background influences DD in English L2 academic writing, shedding light on how linguistic backgrounds impact L2 syntactic structures in academic writing. Such insights could contribute significantly to our understanding of language acquisition and the challenges faced by individuals writing in an L2 academic context. The findings will have implications for understanding the role of native language transfer in English L2 writing.

1.1 Previous research

Syntactic complexity, which involves the range and sophistication of syntactic structures, is considered a key dimension of academic writing development and quality ( Ortega, 2003 ; Lu, 2011 ). A quantitative metric that has garnered heightened attention in syntactic complexity research is DD. DD offers an index for evaluating the density or dispersion of grammatical connections throughout a text. Research suggests that dependency distance minimization (DDM) reflects a universal cognitive pressure for efficient human information processing and linguistic production ( Futrell et al., 2015 ). English writers have been found to prefer syntactic structures with shorter dependencies to reduce integration difficulty and yield more locally coherent sentences ( Temperley, 2007 ). However, cross-linguistic differences have also been observed, with head-final languages like Japanese, Korean, and Turkish showing greater distances attributable to word order variation ( Futrell et al., 2015 ). Chinese and English show different dynamic valency of words and syntactic dependency structures ( Lu et al., 2018 ). Liu et al. (2009) also found that Chinese shows quite different features in dependency relations, with its dependencies tending to be governor-final and mean dependency distance (MDD) being much higher than languages like English, German, and Japanese. While research has examined DDs in native language writing, fewer studies have investigated DDs in L2 academic writing.

1.2 DD optimization in L1 academic writing

Research consistently shows a strong tendency for compact, local syntactic structures in academic writing by L1 writers, which is argued to reflect pressures for efficient linguistic processing and production ( Liu et al., 2017 ). An early study by Temperley (2007) analyzed DDs in the Wall Street Journal portion of the Penn Treebank. It is found that writers favor structures with shorter dependencies, which is evidenced by their preference for short left-branching constituents. Temperley argued that writers optimize and minimize dependency lengths to yield more incrementally interpretable sentences to facilitate comprehension. Futrell et al. (2015) also concluded that DDM is a universal characteristic across human languages, suggesting that variation in language can be explained by the general properties of human information processing. The authors argue that minimizing DDs enhances the efficiency of parsing and producing natural language, reducing integration costs and enabling more efficient packing of information into sentences. Lu and Liu (2020) also discovered a tendency of DDM within noun phrases, potentially due to limitations in human working memory capacity.

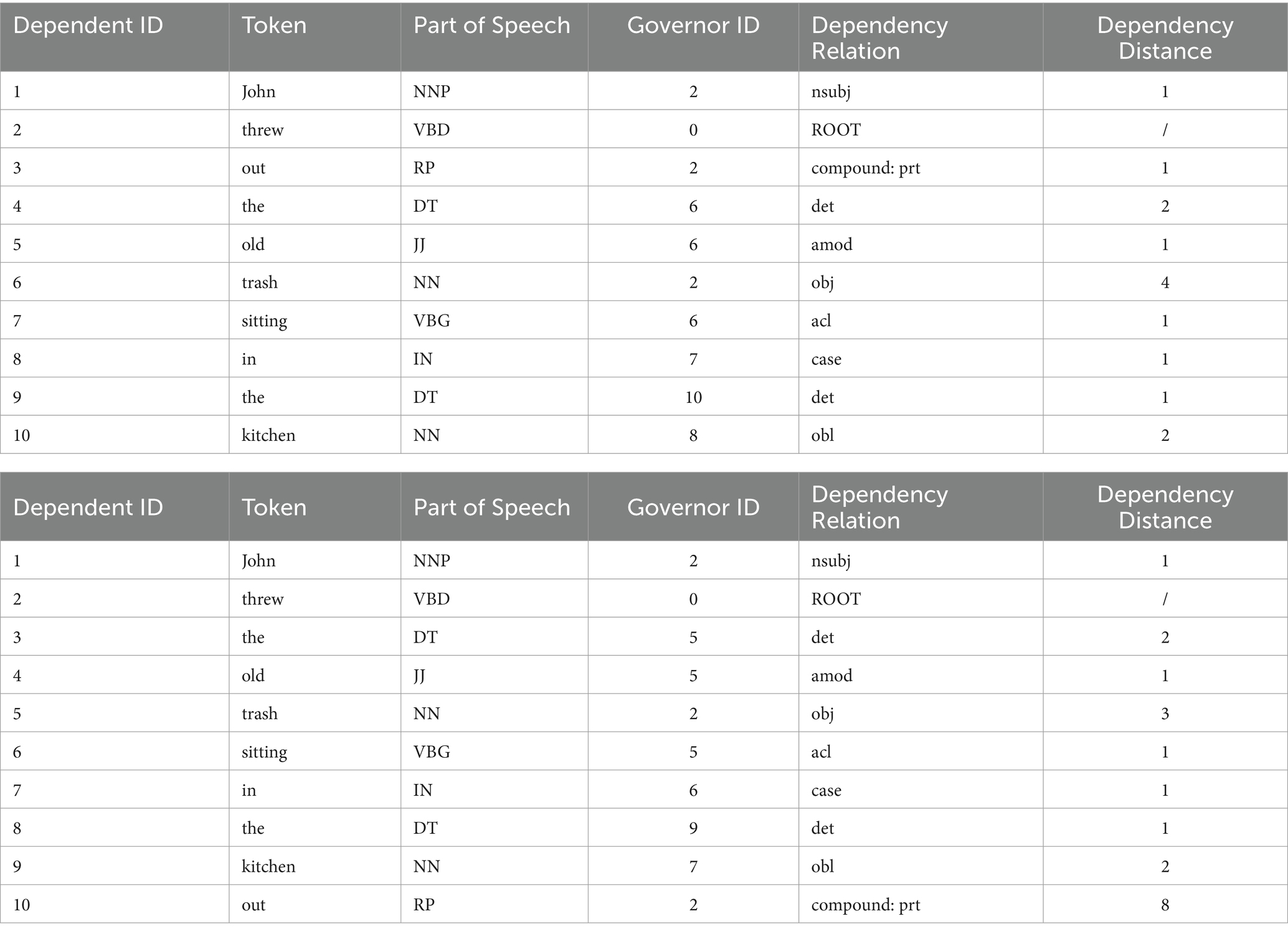

However, cross-linguistic differences have also been observed, attributable to syntactic variations across languages. Futrell et al. (2015) found that head-final languages like Japanese, Turkish, and Korean show much less DDM than head-initial languages like English, Italian, and Indonesian. Temperley and Gildea also found great differences across languages in DD. Their study confirms that DDM serves as an important factor in language structure and cognition, which is evidenced by the fact that writers and speakers tend to prefer structures that reduce dependency length when a language allows for different orderings of constituents ( Temperley and Gildea, 2018 ). Nonetheless, Futrell et al. (2015) argue that DDM remains a universal quantitative property, as overall DDs were substantially shorter than random baselines (benchmarks created by randomly reorganizing the head word and its dependents in dependency trees, without following any specific linguistic word order rules), across all 37 diverse languages in their study. They contend that despite the structural variations among languages influencing their DDs, there is a universal aim in all languages to minimize DDs for the sake of efficiency, within the bounds of their structural limitations. The following example demonstrates the impact of syntactic variations on DD, with the specifics of the dependency relations delineated in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Dependency relations of Examples 1a and b.

Example 1. a: John threw out the old trash sitting in the kitchen. b: John threw the old trash sitting in the kitchen out ( Futrell et al., 2015 : 10337).

The two sentences above convey the same concept and have identical structures, except for the positioning of the word “out.” However, their total and mean DDs significantly differ, at 14 vs. 20 and 1.55 vs. 2.22, respectively. The varying DDs require distinct cognitive effort and working memory capacity. Example 1b where “out” is moved to the end demands more cognitive effort and working memory. For lower cognitive effort and working memory load, Example 1a, which is free from particle movement and exemplifies DDM, is preferred.

In sum, research shows syntax is optimized for brevity both within and across languages to aid production and comprehension, but differences exist due to language-specific conventions.

1.3 DDs in L2 academic writing

While numerous studies have examined L1 DDs, few studies have investigated DDs in L2 academic writing. Ouyang et al. (2022) investigated the writing proficiency of beginner, intermediate, and advanced learners by DD measures. They discovered that the MDD overall is significantly effective at distinguishing between each pair of consecutive proficiency levels. Hao et al. (2022) verified the application of DD and its probability distribution as syntactic indicators of English as interlanguage from the perspective of language typology. They found that the MDDs of L2 learners with different backgrounds of native language gradually approach that of the target language with the improvement of their L2 proficiency. Li and Yan (2021) similarly found that MDD can serve as an effective indicator to measure the syntactic complexity of Japanese EFL learners’ interlanguage. Similarly, Hao et al. (2023) found in their study that dependency parameters have universal applicability in reflecting interlanguage proficiency.

To date, very few studies have directly compared the DD profiles of L2 writers from different L1 backgrounds composing in the L2. Gao and He (2023) examined the MDD of Ph.D. dissertation abstracts written by L1 (native English) and L2 (English as a foreign language) academic writers across language backgrounds and disciplines, finding that MDD successfully distinguishes between academic texts from various linguistic backgrounds and disciplines. They argued that the authors’ efforts to make comprehension easier for readers result in the shorter MDD observed in physics and chemistry abstracts.

Overall, research on L2 DDs remains limited, with very few studies comparing profiles of different L1 groups in natural academic writing tasks. In particular, few studies examined whether L2 DDs and dependency directions are influenced by L2 writers’ native language. This represents a significant gap, as investigating cross-linguistic differences can elucidate the role of L1 transfer versus universality in L2 syntactic development, with key theoretical and pedagogical implications ( Ortega, 2003 ).

1.4 Transfer of syntactic features in L2 acquisition

In examining the impact of native language transfer in L2 acquisition, scholars have extensively investigated how syntactic features influence L2 language production. Whong-Barr and Schwartz (2002) reveal that in the L2 acquisition process, children’s mastery of English dative constructions is significantly shaped by their native linguistic backgrounds, underscoring the influence of L1 syntactic frameworks and prevalent overgeneralization patterns on their learning trajectory. Chan (2004) demonstrates evidence of syntactic transfer from Chinese to English among Hong Kong Chinese ESL learners, revealing that learners often think in Chinese before writing in English, leading to interlanguage structures that closely resemble or mirror the syntactic patterns of their first language, particularly in complex target structures and among learners of lower proficiency levels. Recent advancements in second language acquisition research have introduced theories such as the Interpretability Hypothesis by Tsimpli and Dimitrakopoulou (2007) , which argues that learners can acquire L2 features interpretable across syntax and other cognitive systems like semantics or pragmatics, regardless of their presence in L1; the Interface Hypothesis by Sorace and Filiaci (2006) , highlighting the particular difficulties learners face with language elements that integrate syntax with semantics or discourse; and the Feature Reassembly Hypothesis by Lardiere (2009) , emphasizing the primary challenge of reconfiguring L1 features to conform to the target language’s system, often leading to substantial learning challenges, especially where the languages’ feature systems notably diverge.

Though these new theories have been much discussed in recent years, language transfer theory remains relevant due to its powerful explanatory capabilities, able to account for many phenomena in L2 acquisition. This study aims to explore syntactic transfer through the lens of DG. We contend that the dependency patterns of an individual’s native language can influence those in their L2 writings. For instance, consider Chinese, which is predominantly a head-final language, and English, primarily a head-initial language. The MDD of Chinese stands at 3.662, markedly higher than English’s MDD of 2.543. We hypothesize that this significantly larger MDD in Chinese will lead to extended MDDs in L2 English writings by Chinese learners, as a consequence of language transfer. This study will verify our hypothesis.

2 Objectives and significance

This study delves into how L1 backgrounds influence L2 writing, particularly focusing on DDs in academic writing. It examines whether different L1 backgrounds result in distinct DD patterns in English L2 writing, potentially due to L1 transfer, or if universal linguistic principles lead to uniform patterns across L1 groups. This inquiry aims to illuminate key debates within second language acquisition (SLA) regarding the influence of native language versus universal syntax principles. It seeks to fill significant gaps in existing research and enhance writing instruction practices by clarifying the extent of cross-linguistic influence versus universal principles in L2 writing development.

The outcomes of this research could provide significant implications for both SLA theory and academic writing instruction. By identifying whether L2 writers’ dependency profiles are shaped more by their L1 syntax or universal syntax norms, this study inform educational strategies—determining if writing instruction should be tailored to specific L1 backgrounds or aligned with broader, universal writing strategies. These insights will guide educators on whether to prioritize language-specific strategies or general methods to help L2 writers reach native-like proficiency.

3 Theoretical framework

This study investigates the effect of native language on English L2 academic writing, employing quantitative analysis of dependency grammar (DG). DG, serving as a theoretical linguistic framework, delineates language structure by scrutinizing the relationships among its components. These relationships, known as dependencies, are asymmetrical connections between two constituents of a sentence, typically words, where one assumes the role of the governor or head, and the other, the dependent or modifier ( Fraser, 1994 ). In DG, DD and dependency direction, often utilized as variables in linguistic studies, serve as two critical indices for quantitative analysis. DD ( Liu, 2007 , 2008 ; Liu et al., 2017 ), also known as dependency length ( Temperley, 2007 , 2008 ; Gildea and Temperley, 2010 ; Futrell et al., 2015 ; Temperley and Gildea, 2018 ), refers to the linear positional difference between two words within a sentence serving as governor and dependent ( Hudson, 1995 , 2010 ; Liu et al., 2009 ). It is measured by the number of intervening words between dependents and their governors ( Hudson, 1995 ). For any dependency relation between two words Wx and Wy , if x is the governor and y is its dependent, their DD equals the difference x − y ; thus, adjacent words have a DD of 1. A positive distance signifies that the governor follows the dependent, whereas a negative distance indicates the governor precedes the dependent. Nevertheless, for the calculation of MDD, the absolute value of DD is used. The MDD for a sentence can be determined using the equation below:

where n represents the total number of words in a sentence and DD i indicates the DD of the i -th syntactic relation within the sentence (see Liu et al., 2009 : 166). Typically, there exists one word in each sentence that does not have a governor. This word is termed the root verb, and its DD is considered zero.

where n represents the total number of words in a sample and s indicates the number of sentences in the sample (see Liu et al., 2009 : 166). DD i refers to the DD of the i -th syntactic relation within the sample.

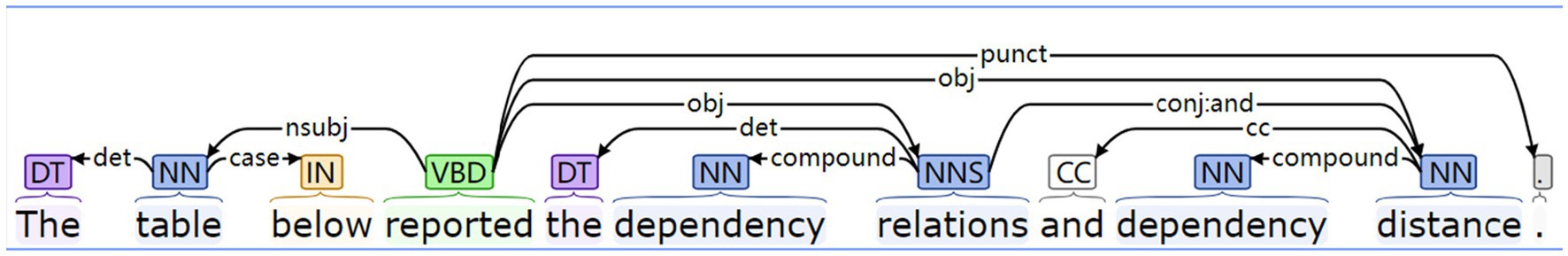

The example below illustrates a dependency analysis. Figure 1 lists the dependency structure of Example 2, while Table 2 details the dependency relations and distances associated with it.

Figure 1 . Dependency structure of Example 2.

Table 2 . Dependency relations of Example 2.

Example 2. The table below reported the dependency relations and dependency distance.

Figure 1 depicts the dependency relations between governors and their dependents in the example sentence. Syntactically related word pairs are connected by labeled lines with arrows pointing from the governor to the dependent. These labels, including nsubj , det , obj , conj , and punct , denote the specific dependency relations between the connected words.

Based on Eq. 1 , the MDD of the example is:

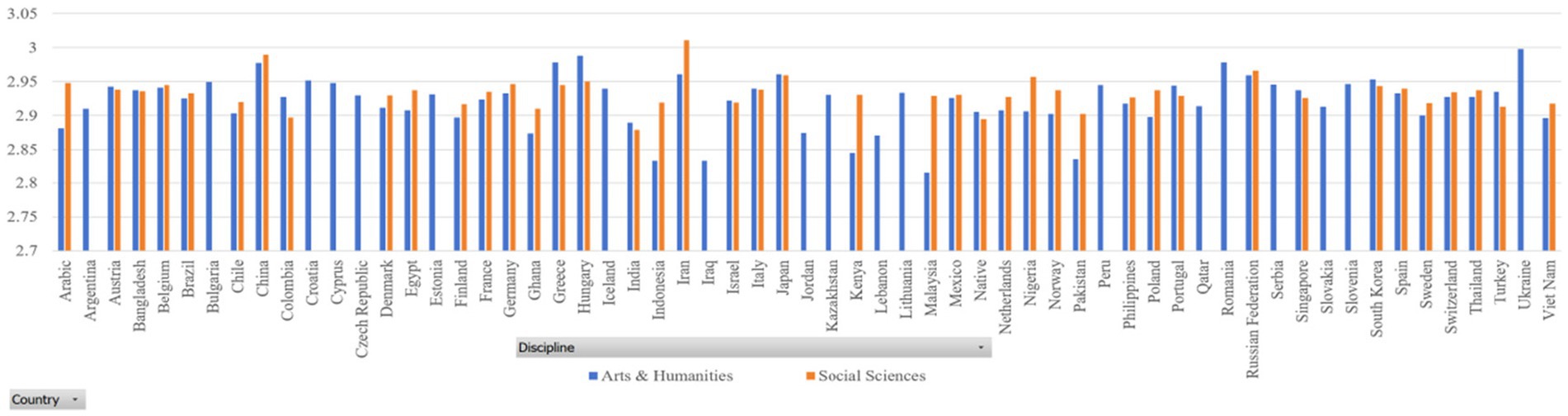

As mentioned before, DD can manifest as positive or negative contingent on whether the governor precedes or succeeds its dependent, thereby indicating the direction of dependency. When the governor precedes its dependent, DD is negative, indicating a governor-initial dependency relation, otherwise positive, denoting a governor-final dependency relation. The dependency direction within a sample can be quantified by calculating the percentages of governor-initial (or head-initial) and governor-final (or head-final) relations, using the following equations:

(see Liu, 2010 : 1570)

Applying the aforementioned Eqs. 3 and 4 , the dependency direction of Example 2 is:

Evidently, the example sentence contains substantially more head-final dependencies compared to head-initial ones, indicating that most dependents precede their governors.

This study primarily focuses on the overall differences or similarities in DD between L1 and L2 English, without delving into the specific types of dependencies in each language. Our aim is to investigate the broad impact of native language on L2 writing, rather than examining the nuanced differences in dependency types and their respective DDs. These finer details of dependency types and corresponding DDs will be the subject of our future research.

This study’s DG analysis benefits from recent advances in natural language processing (NLP) technology, particularly in automating part-of-speech tagging and syntactic parsing. Previously, the slow and costly manual processes hindered the development of treebanks—key resources containing tagged and parsed sentences. However, modern NLP has overcome these challenges by enabling automatic tagging and parsing via machine learning, leveraging existing treebanks. These developments have expanded the application of NLP across the humanities, situating this research within the broader trend of integrating NLP into linguistic studies.

4 Methodology

4.1 research questions.

In the present study, we intend to answer the following three questions:

(1) Is there a significant difference in DD between English L2 academic writings and native academic writings?

(2) Is there a significant difference in dependency direction between English L2 academic writings and native academic writings?

(3) Is the DD of L2 academic writings influenced by native languages?

4.2 Data collection

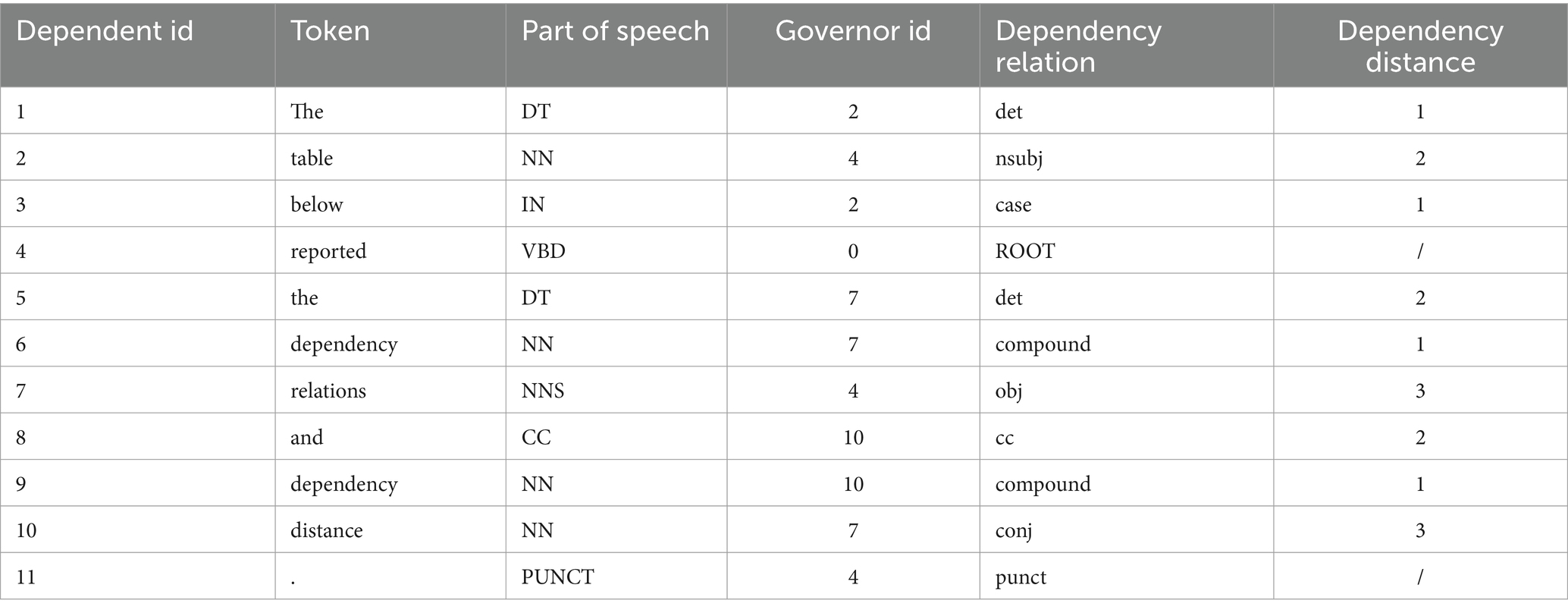

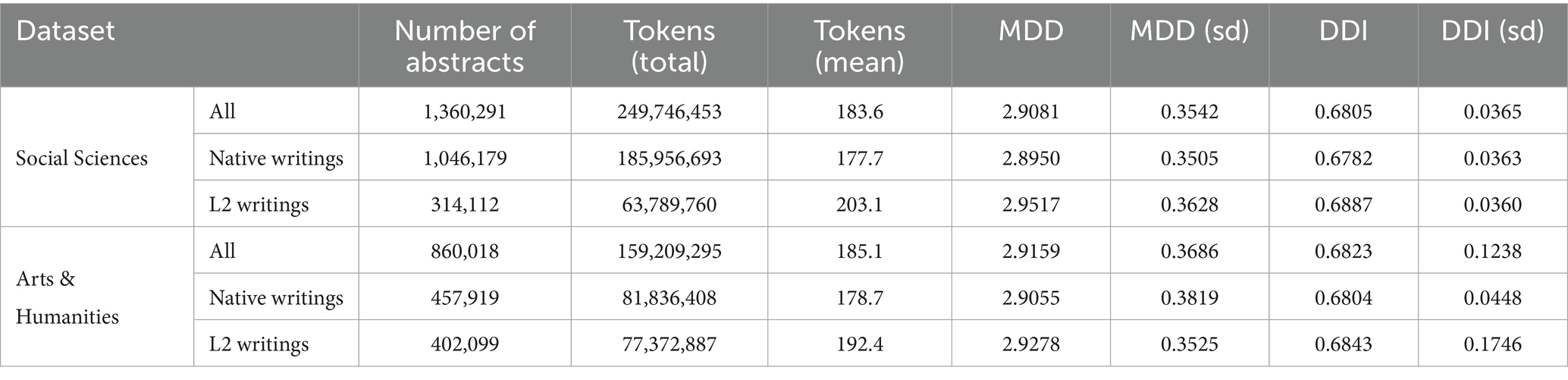

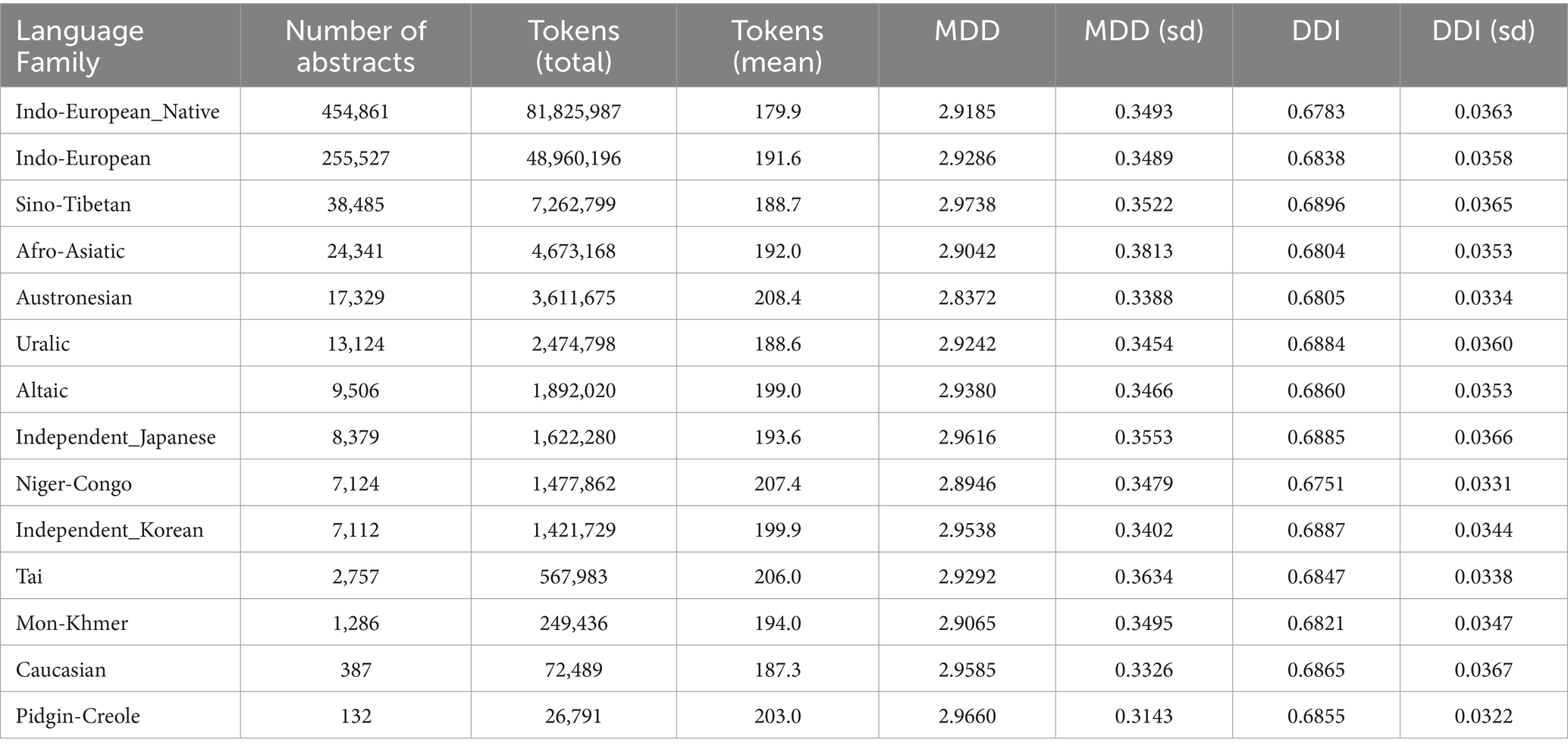

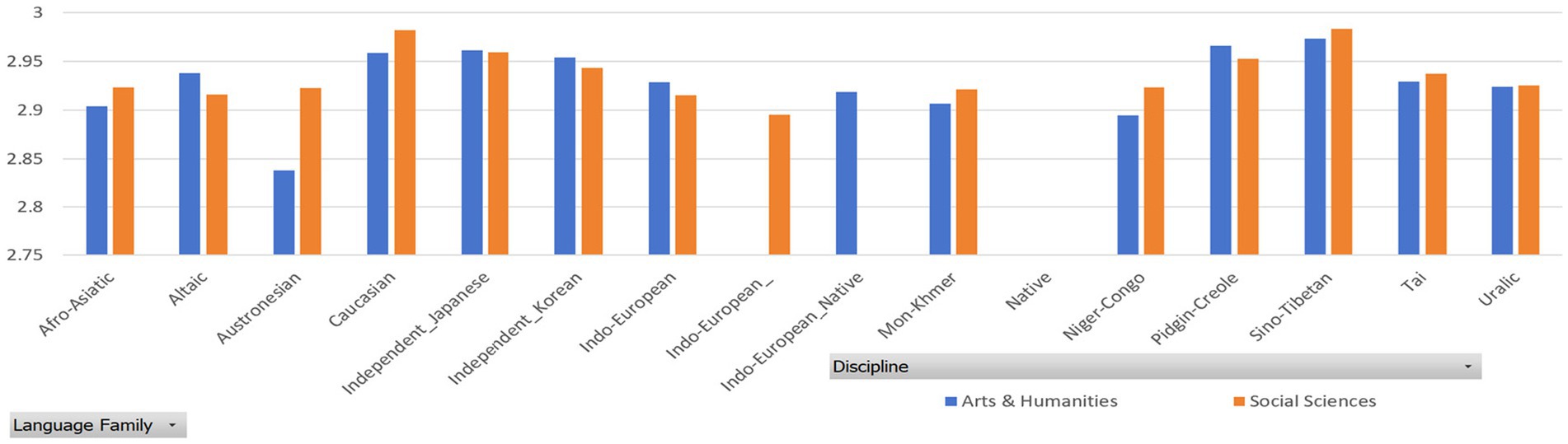

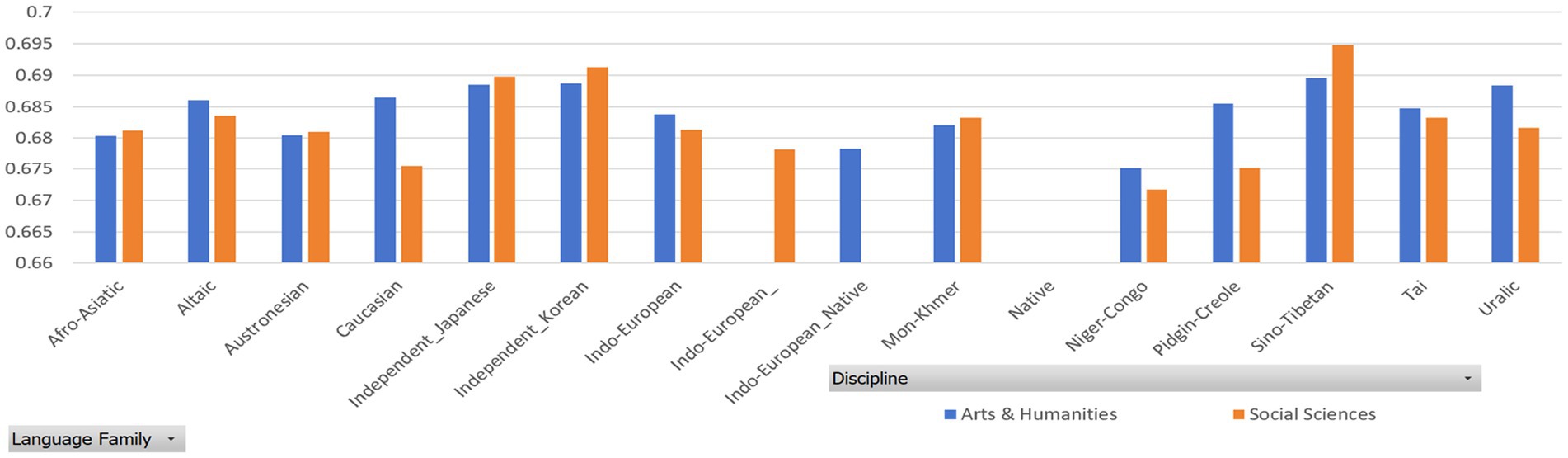

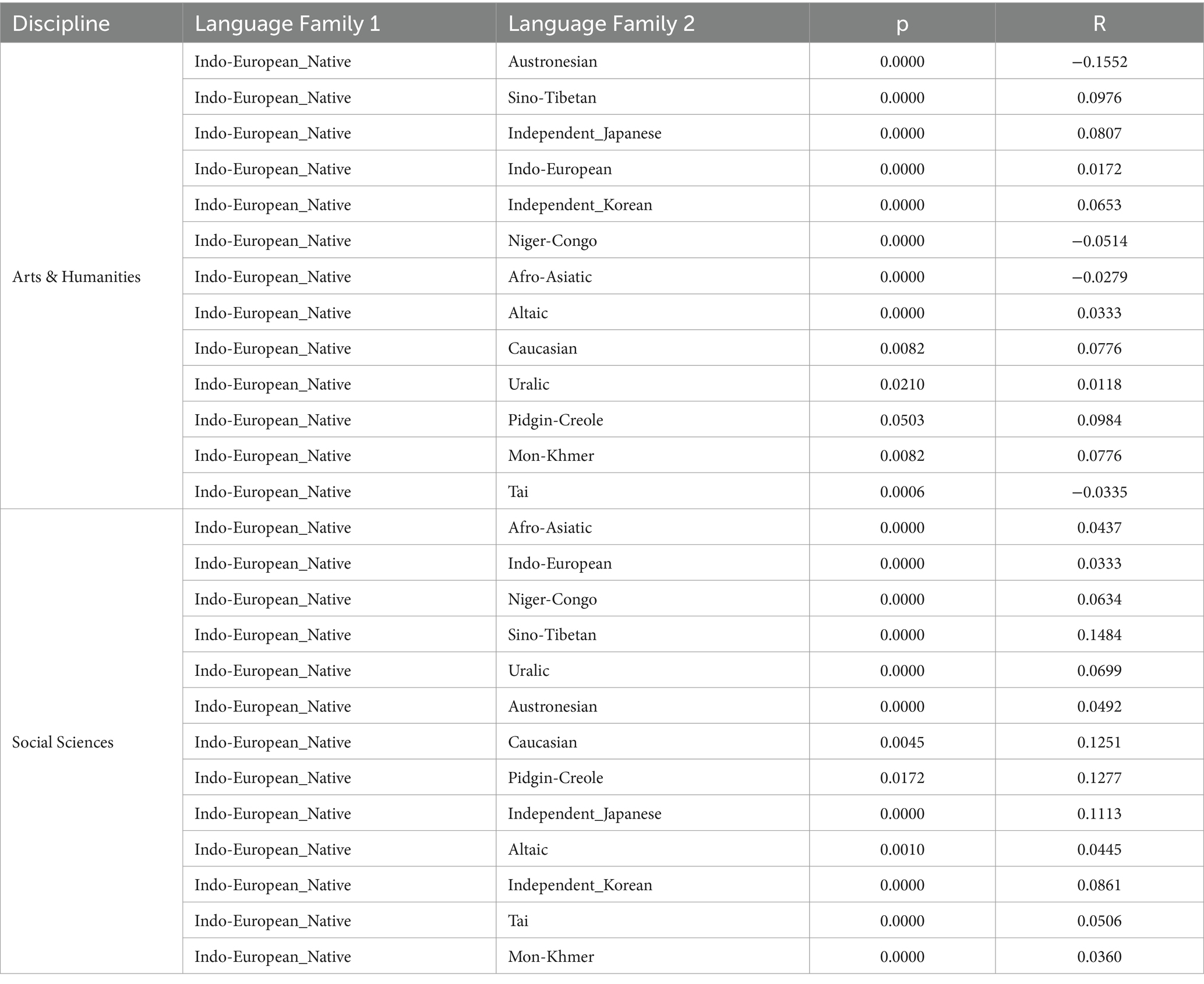

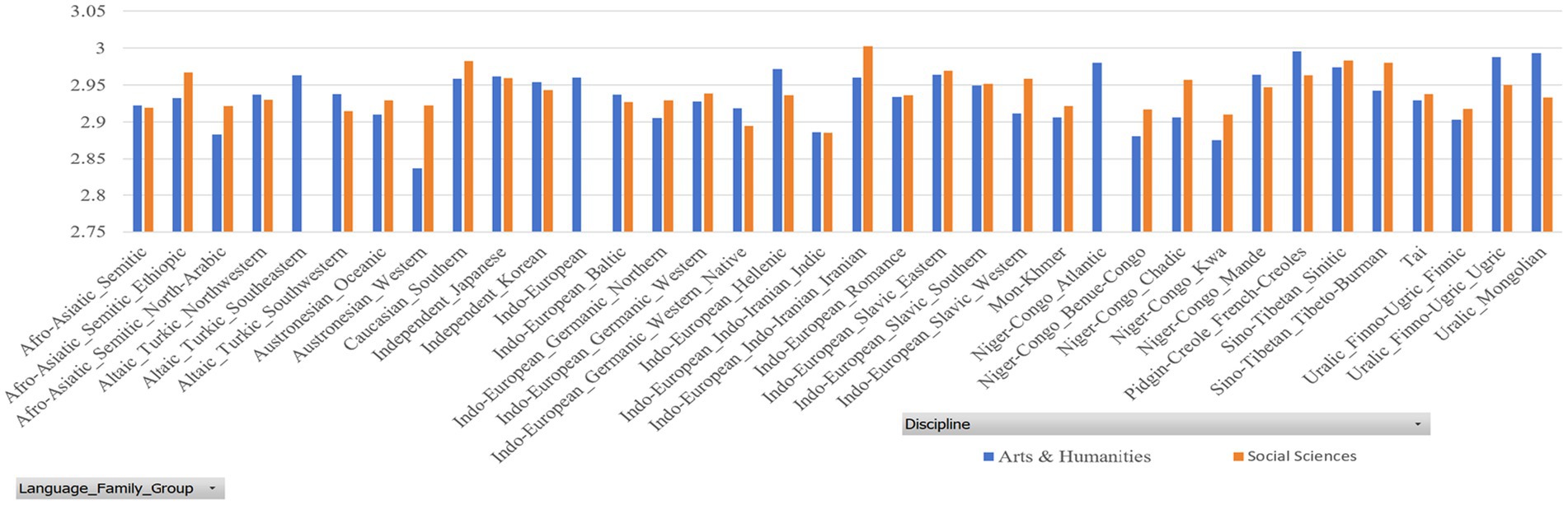

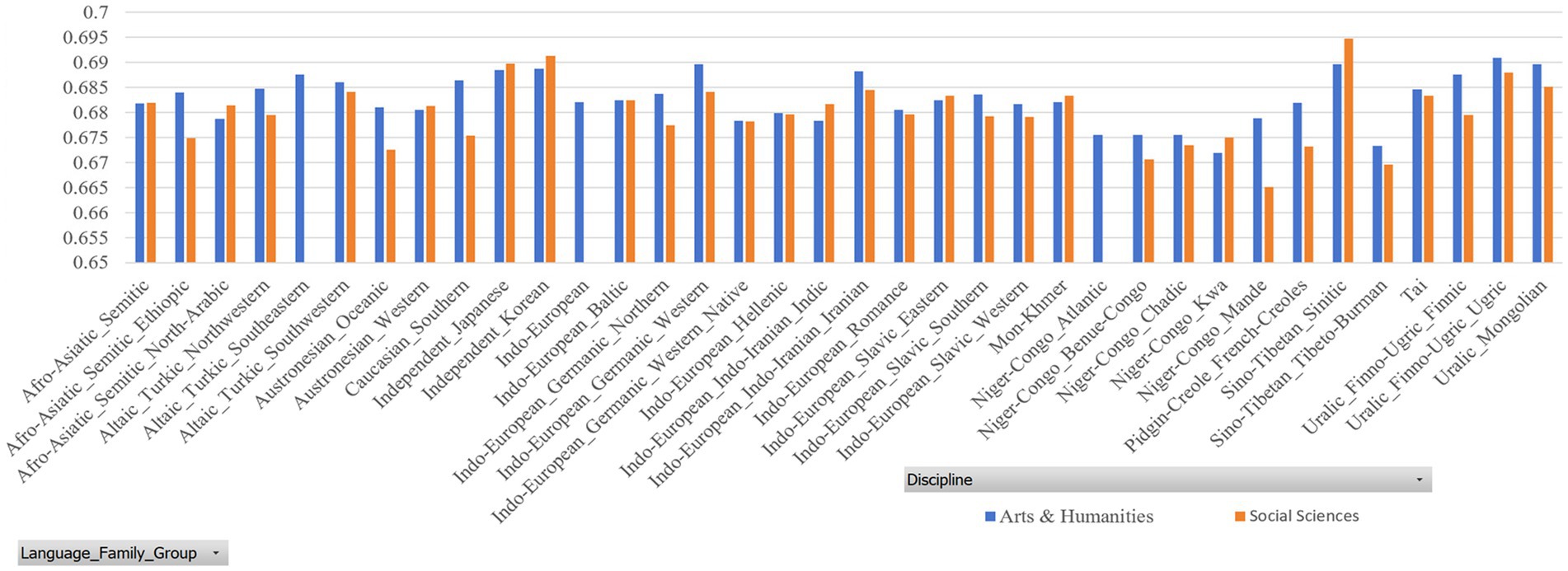

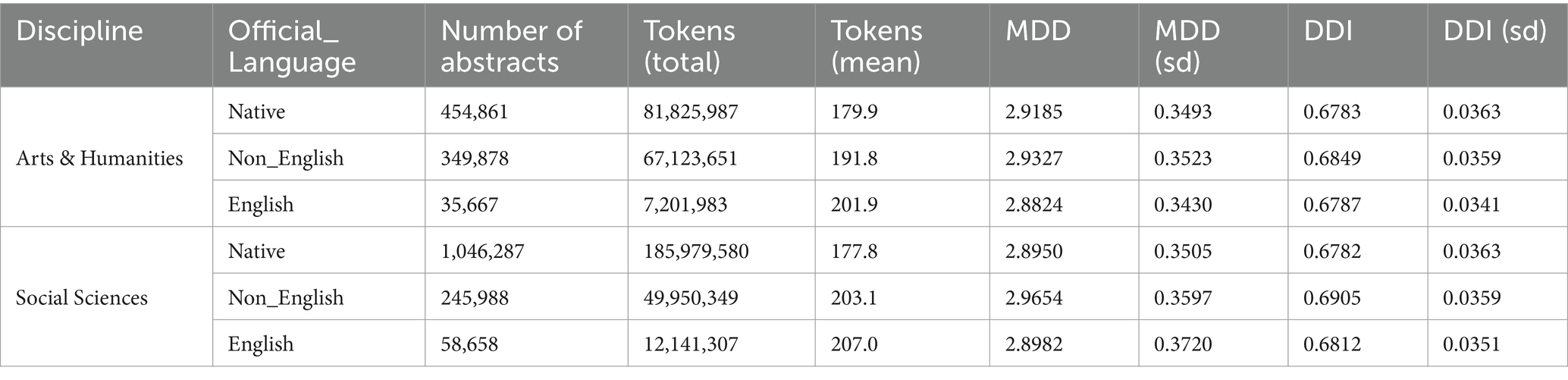

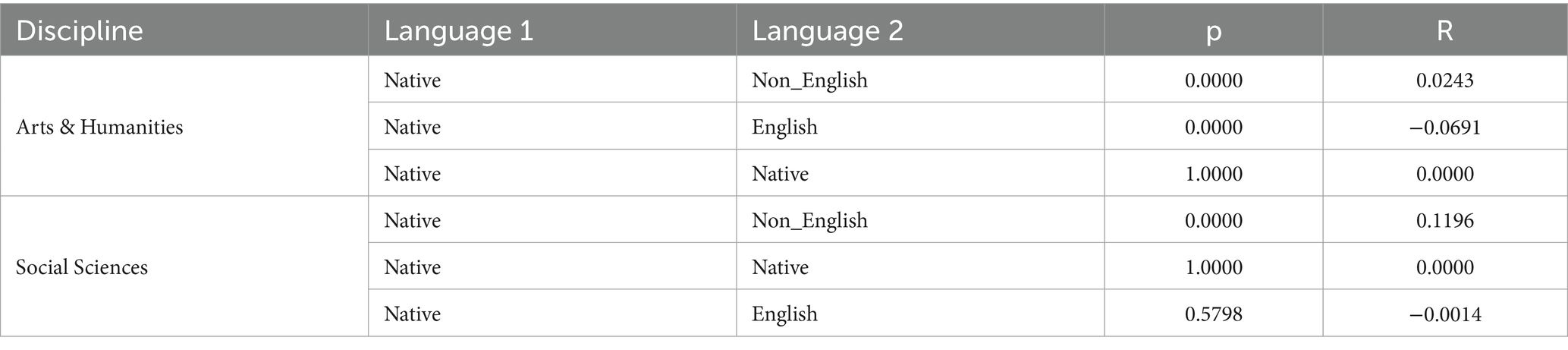

The data for the present study was sourced from Scopus, selected for its status as the most extensive academic database and its established reliability as a data collection source across numerous studies ( Crosthwaite et al., 2022 , 2023 ; Zakaria and Aryadoust, 2023 ). Articles were chosen from the disciplines of Arts and Humanities and Social Sciences, limiting the selection to the “article” type while excluding “book review” and “book chapter” types, with an additional restriction for language to English only. In exporting the articles, we included the complete metadata for each article. Altogether over 2.65 million articles were extracted and stored in CSV files, with each metadata item allocated to a distinct column. Articles originating from various countries were segregated into separate CSV files, amounting to 178 files in total. The methodology for cleaning and processing the raw data is outlined in the following section.

4.3 Data cleaning and processing

We cleaned and processed the raw data using the following procedures. First, we wrote an R script to extract the “abstract” and “affiliation” columns. Second, we extracted the country names from the affiliation column, removed rows in the abstract column where no abstract was available using an R script, and manually checked the rows in the affiliation column where the country names were not available. Following the cleaning process, we obtained more than 2.22 million abstracts, totaling over 408.9 million tokens. Next, we calculated the dependency distance and direction for each abstract in each CSV file based on Eq. 2 . This calculation was performed in Python, utilizing the Stanford CoreNLP package version 4.5.5. This package was selected due to its strong performance and established reliability as an NLP tool, as evidenced by various studies ( Manning et al., 2014 ; Blšták and Rozinajová, 2022 ; Hashemi-Namin et al., 2023 ; He and Ang, 2023 ).