- Open access

- Published: 03 May 2023

The management of healthcare employees’ job satisfaction: optimization analyses from a series of large-scale surveys

- Paola Cantarelli 1 ,

- Milena Vainieri 1 &

- Chiara Seghieri 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 23 , Article number: 428 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

4667 Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

Measuring employees’ satisfaction with their jobs and working environment have become increasingly common worldwide. Healthcare organizations are not extraneous to the irreversible trend of measuring employee perceptions to boost performance and improve service provision. Considering the multiplicity of aspects associated with job satisfaction, it is important to provide managers with a method for assessing which elements may carry key relevance. Our study identifies the mix of factors that are associated with an improvement of public healthcare professionals’ job satisfaction related to unit, organization, and regional government. Investigating employees’ satisfaction and perception about organizational climate with different governance level seems essential in light of extant evidence showing the interconnection as well as the uniqueness of each governance layer in enhancing or threatening motivation and satisfaction.

This study investigates the correlates of job satisfaction among 73,441 employees in healthcare regional governments in Italy. Across four cross sectional surveys in different healthcare systems, we use an optimization model to identify the most efficient combination of factors that is associated with an increase in employees’ satisfaction at three levels, namely one’s unit, organization, and regional healthcare system.

Findings show that environmental characteristics, organizational management practices, and team coordination mechanisms correlates with professionals’ satisfaction. Optimization analyses reveal that improving the planning of activities and tasks in the unit, a sense of being part of a team, and supervisor’s managerial competences correlate with a higher satisfaction to work for one’s unit. Improving how managers do their job tend to be associated with more satisfaction to work for the organization.

Conclusions

The study unveils commonalities and differences of personnel administration and management across public healthcare systems and provides insights on the role that several layers of governance have in depicting human resource management strategies.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Measuring employees’ satisfaction with their jobs and working environment have become increasingly common worldwide among government and public organizations across fields, including healthcare [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Designing personnel policies that fit workers’ perceptions turned out to be uncontroversially relevant. Even more so during challenging times such as those generated by budget cuts and increased demands for public service provision [ 1 ] or caused by health and economic emergencies such as the COVID-19 outbreak [ 5 ]. The Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey administered by the United States Office of Personnel Management to federal civil servants is just the most famous example of how organizations can monitor workers’ attitudes and perceptions to manage human capital effectively [ 6 , 7 ]. Among the OECD governments administering surveys to their employees, the most common focus is on job satisfaction. Indeed, the number of countries that center the items of questionnaires on employees’ satisfaction is larger than those centering on work-life balance, employee motivation, or management effectiveness [ 1 ].

Public healthcare organizations are not extraneous to the irreversible trend of measuring employee perceptions to boost performance and improve service provision [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Indeed, asking employees to express their opinion on the work environment in which they operate daily to provide social and health services to citizens make them involved in the management and planning of activities. At the same time, employees’ feedback become a valuable resource for organizational management and an important tool to initiate targeted, efficient and effective improvement processes based on staff needs and expectations. Considering the multiplicity of aspects associated with job satisfaction, it is important to provide management with a method for assessing which elements it may be useful to focus on.

Our study is dedicated to identifying the mix of factors that are associated with an improvement of health professionals’ job satisfaction related to unit, organization, and regional government in the context of a series of large-scale surveys. Investigating employees’ satisfaction and perception about organizational climate with different governance levels seems essential in light of extant evidence showing the interconnection as well as the uniqueness of each governance layer in enhancing or threatening motivation and satisfaction across public administration fields, including government [ 12 , 13 ] and healthcare [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Our work provides several contributions to existing knowledge on the correlates of job satisfaction among civil servants in health organizations. Our findings may prove useful to scholars and practitioners alike. Firstly, to the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first that employs optimization models for this purpose. In doing so, we espouse recent invitations to develop research projects that are context-sensitive and practical so to be able to develop middle range theories because optimization analyses is primarily meant to speak to managers and healthcare professionals [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Indeed, the main objective of the calculation of the optimization function is to provide some indications with a managerial value on the most efficient group of predictors – organizational variables – that can drive a preset level of improvement in job satisfaction so to close the science-practice gap in healthcare management work. In other words, the calculation provides a numerical information that shows how much organizational aspects weigh on the level of satisfaction. It was introduced for the first time in the field of health performance analysis by a group of researchers from the Ontario Ministry of Health in Canada [ 20 , 21 ] and subsequently used in the Italian context to analyze patient satisfaction emergency departments and nursing homes [ 22 , 23 ]. The use of optimization techniques in public administration is largely unexplored at the moment. Secondly, although unable to collect data across healthcare systems in the world, we account for common critiques about the external validity of findings in public administration research by combining large samples and survey replications in our research design [ 24 , 25 ]. Even in the country where the study is set, the number of respondents in our work is rather unique.

Job satisfaction in mission-driven organizations: a literature overview

Job satisfaction is one of the most investigated constructs by practitioners and scholars alike across disciplines such as health services [ 2 , 26 ], public administration [ 27 ] and applied psychology [ 28 , 29 ]. In the words of Hal Rainey [ 30 ], “thousands of studies and dozens of different questionnaire measures have made job satisfaction one of the most intensively studied variables in organizational research, if not the most studied” (p. 298).

Scholars across fields such as public administration, mainstream management, and psychology agree that work satisfaction construct includes facets related to the fulfillment of various and evolving individual needs and to the fit with numerous and changing organizational level variables [ 28 ]. Recent definitions by public administration and management scholars portray job satisfaction as an “affective or emotional response toward various components of one’s job” [ 31 ] (p. 246) or as “how an individual feels about his or her job and various aspects of it usually in the sense of how favorable – how positive or negative – those feelings are” [ 30 ] (p. 298). Previous definitions in mainstream management and applied psychology describe job satisfaction as “the feelings a worker has about his job” [ 32 ] (p. 100) or as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state, resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” [ 33 ] (p. 1304).

The breadth and depth of scholarship onto job satisfactions has nurtured efforts to synthesize and systematize available knowledge through meta-analyses and systematic literature reviews in recent years. For instance, Cantarelli and colleagues [ 27 ], collected quantitative information from primary studies published in 42 public administration and management journals since 1969 and performed a meta-analysis of the relationships between job satisfaction and 43 correlates, which span from mission valence, job design features, work motivation, person job-fit, and demographic characteristics. Furthermore, Vigan and Giauque [ 34 ] present results from a systematic review of the association between work environment attributes, personal characteristics, and work features on the job satisfaction of public employees in African countries. Then, meta-analytic findings show a positive correlation between job satisfaction and public service motivation [ 35 ] and pay satisfaction [ 36 ].

At the same time, novel studies on work satisfaction among employees across typologies of organizations do not seem to have come to an end. To the contrary, for example, observational work still investigate the individual and organizational correlates of employees’ satisfaction in public healthcare organizations [ 3 , 16 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ] and government institutions more in general [ 7 , 43 , 44 ]. A similar interest pertains to employees’ preferences in experimental scholarship in public hospital [ 45 ] and public organizations [ 46 ].

Based on the evidence summarized above, we investigate the association between public employees’ job satisfaction to work for their unit, organization, and government system and variables that pertains to the following broad domains: workplace safety, human resource management practices at the team level, supervisors’ managerial capabilities, management practices at the organizational level, and training opportunities.

Building on such experiences as the Federal Employees Viewpoint Survey [ 47 ] and the NHS staff survey, several healthcare systems in Italian Regions administer organizational climate questionnaires to all employees on a routine basis thanks to their collaboration with the Management and Healthcare Laboratory (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy). Italy currently features a national health service with three main hierarchical levels. The first layer is that of the national health departments that define general strategies, laws, and regulations and set general targets. Regional governments, then, are the second hierarchical level. They are in charge of implementing such strategies and meeting such targets. The 21 Italian Regions are autonomous in this implementation phase. As a result, the variation in the governance structures and healthcare services is large among regional health systems. The third layer includes all organizations (i.e., local health authorities, hospitals, and teaching hospitals) that are at the front-line of health services provision to the population.

The decision to administer an organizational climate survey pertains to the regional government. Members of the Management and Healthcare Laboratory (authors included) design organizational climate surveys together with regional healthcare systems, which, at its core, are interested in using results for sustaining managerial change across the healthcare system. The rationale behind the analysis of region-wide data is multifaceted. First of all, the measurement instrument used in our study has been validated [ 48 , 49 ] and used in previous work [ 9 ] for data analysis at the regional and subsequently organizational level. Secondly, our presentation of results tends to score high on ecological validity because of the mechanisms that govern the provision of healthcare services in Italy where decisions taken at the regional level are binding for organizations within the region. Thirdly, the presentation of results by region resonates with well-established practices on the international stage. Just as an example, NHS staff results are presented at the national level also. As a consequence, our survey includes management variables—such as communication, information sharing, training, budget procedures – that tend to cross the borders of professions. The participation of healthcare employees to the questionnaire is voluntary and anonymous. The survey is composed of statements to which respondents indicate their level of agreement on a 1 to 5 Likert-type sale (1 means full disagreement and 5 full agreement). The questionnaire measures employees’ perceptions about their job, organization, management practices, communication and information sharing processes, training opportunities, budget system, and working conditions [ 9 , 50 ].

The outcome variables in this study relate to employees’ job satisfaction for three hierarchical levels, namely satisfaction with one’ unit, organization, and regional health service. These layers are key in the Italian healthcare system. In fact, all three levels hold levers that can be pulled to affect job satisfaction. In particular, we used the following statements:

I am satisfied to work in my unit.

I am proud to tell others that I work in this organization.

I am proud to work for the health service of my Region.

We regress each of these three outcome variables on the following list of correlates, which are survey items that tap into different theoretical domains and represent dimensions that can be modified through organizational change initiatives:

The equipment in my unit is adequate.

My workplace is safe (electrical systems, fire and emergency measures, etc.).

My workload is manageable.

Meetings are organized regularly in my unit.

Work is well planned in my unit and this allows us to achieve goals.

Periodically I am given feedback from my supervisor on the quality of my work and the results achieved.

My suggestions for improvement are considered by my supervisor.

I feel like I'm part of a team that works together to achieve common goals.

My supervisor knows how to handle conflict.

I agree with the criteria adopted by my supervisor to evaluate my work.

My supervisor is fair in managing subordinates.

I believe that my supervisor carries out his job well.

My organization encourages change and innovation.

The organization encourages information sharing.

My supervisor encourages information sharing.

I know annual organizational goals.

I know annual organizational accomplishments.

The training activities offered by my organizations are useful in enhancing my competences.

The training activities offered by my organizations are useful in improving my communication skills with colleagues.

I appreciate how managers manage the organization.

My organization stimulates me to give my best in my work.

I am motivated to achieve organizational goals.

In my organization, merit is a fundamental value.

In my organization, the professional contribution of everyone is adequately recognized.

Following the methodology of Brown and colleagues [ 20 ], the first phase for the calculation of the optimization function consists of an ordinal logistic regression in which satisfaction is predicted by the organizational variables of interest listed above. The second phase, then, combines the regression coefficients with the average values of the items of interest to identify, under certain pre-established mathematical constraints, the set of organizational variables that, with a certain improvement (always less than 15% for constraints required by the type of analysis) allows to reach a fixed level of overall satisfaction. Thus, optimization techniques allow the identification of the most efficient mix of predictors of employees’ satisfaction to help guide improvement efforts. An important information to consider when reading the results of these types of surveys is that improving the score of a variable that is very close to its benchmark is more difficult than that of a variable that is far from it. It is important to underline that the model is built on the average of the answers, so it does not refer to the strategies to be adopted in cases of falling perceptions related to the organizational climate. In other words, the model does not focus on ways to recover the satisfaction of particularly unsatisfied staff. As for the second phase of the statistical analysis, we used a 5 percent improvement of the job satisfaction outcome variables.

The two phases of analysis listed above have been repeated for each of the four Regions that are included in this study. Region A administered the organizational survey in April and May 2018, Region B in December 2018 and January 2019, Region C in March and April 2019, and Region D between mid-October and mid-December 2019. Respondents are 73,441 healthcare employees, of which 24,869 work in Region A; 5,078 in Region B; 21,272 in Region C; and 22,222 in Region D. The response rates are as follows: 28 percent for Region A, 27 percent for Region B, 39 percent for Region C, and 45 percent for Region D.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of respondents for each of the four healthcare systems included in our study. In all four cases separately, the average age of participants is not significantly different from the corresponding regional average of all healthcare professionals. Female professionals are slightly overrepresented in all regions compared to the national average of female healthcare professionals. The distribution of respondents across job families in each of the four samples is comparable to the national distribution of healthcare employees [ 51 ].

Table 2 displays the average job satisfaction, by regional healthcare system and by governance level – namely unit, organization, and Region – along with average standard deviation in parenthesis. Overall, the satisfaction to serve one’s organization is lower than the satisfaction to work for the unit and the regional healthcare system.

Table 3 presents the results of the logistic regression on the satisfaction to work for one’s unit across regional healthcare systems. In all regions, keeping everything else constant, professionals’ satisfaction to serve their unit is strongly and positively associated with the following constructs: adequate equipment, work safety, manageable workload, well-planned work, consideration of one’s improvement proposals, sense of being part of a team, agreement with the criteria for individual performance assessment, appreciation for the competences of one’s supervisor, organizational stimulation to give one’s best, and motivation to achieve organizational goals. All relationships are statistically significant at the 0.01 level. In Region A, coeteris paribus, training activities to enhance one’s competences and appreciation for how managers manage the organization are also positively related to job satisfaction at the unit level ( p < 0.001 and p = 0.001 , respectively). As for Region B, keeping everything else the same, supervisor’s fairness in managing subordinates and training opportunities are additional positive correlates ( p = 0.003 and p = 0.004 , respectively). In Region C, everything else equal, the following items also correlates positively with the outcome: supervisor’s fairness in managing subordinates ( p < 0.001 ), supervisors’ encouragement of information sharing ( p = 0.018 ), training opportunities to improve one’s skills ( p < 0.001 ), and appreciation for how managers manage the organization ( p = 0.033 ). Lastly, in Region D, everything else equal, the additional positive correlates of job satisfaction are the following: supervisor’s ability to fairly treat subordinates ( p < 0.001 ), training opportunity to improve professional competences ( p < 0.001 ), and appreciations for managers ( p < 0.001 ).

Table 4 sows the results of the optimization function, set for a 5 percent improvement in average value of the item “I am satisfied to work in my unit.” Predictions tend to be consistent across regional healthcare systems. In all regions, in fact, keeping everything else the same, the job satisfaction improvement at the unit level is associated with an improvement in the mean value of the following constructs: well-planned work in the team, perception of being part of a team that work towards shared goals, and perception that the supervisor can carry out the job well. More precisely, the percentages of improvement for these three correlates are as follows, respectively: 1, 15, and 12 for Region A, 1, 15, and 14 for Region B; 7, 15, and 13 for Region C; and 2, 15, and 13 for Region D.

Table 5 displays the logistic regression results for professionals’ satisfaction to work for their organization. In all regions, everything else equal, the positive correlates at the 0.05 or smaller significance level are the following: adequate equipment, workplace safety, sense of being part of a team, supervisor’ abilities to do a good job, training opportunities to enhance competences, appreciation for how managers manage the organization, organizational stimuli to give one’s best on the job, and motivation to achieve organizational goals. The relationship between the satisfaction to work for one’s organization and the degree to which one’s work is manageable is positive at the 0.05 significance level for all regions except Region A, everything else constant. Having a well-planned work is a significant correlate in Region D only ( p = 0.020 ), ceteris paribus. Participants’ perceptions that their suggestions for improvement are taken into consideration are significantly related to satisfaction in Regions A and B only, keeping everything else constant ( p = 0.001 and p = 0.043 respectively). Region C is the only that displays an association between the outcome of interest and respondents’ agreement with the criteria adopted to evaluate individual performance, ceteris paribus ( p = 0.025 ). Further, everything else equal, job satisfaction to work for one’s organization is positively associated with the degree to which the organization encourages change and innovation in Region A ( p < 0.001 ), in Region C ( p = 0.003 ), and Region D ( p < 0.001 ). Lastly, respondents in Region A and D show a significant association between the outcome and what supervisors do to encourage information sharing, everything else kept constant ( p = 0.041 , p = 0.038 , and p = 0.038 , respectively).

Table 6 presents the results of the optimization analysis for a 5 percent increase in the average value of the item “I am proud to tell others that I work in this organization.” Maintaining everything else constant, improving the mean of employees’ appreciation for how managers manage the organization is correlated to an enhanced job satisfaction at the organization level in all regions. In particular, the percentage improvement for the former statement are 12 percent for Region A, 9 percent for Region B, and 13 percent for all of the remaining regions. Furthermore, in Region B, ceteris paribus, a 9 percent percent improvement in the level of agreement with the statement that the organization stimulates employees to give their best on the job is related to the betterment of the outcome.

Table 7 displays estimates from a logistic regression model for public employees’ satisfaction to work for the health service of their regional government. Keeping everything else equal, across regions, the positive correlates at the 0.05 significance level are the following: workplace safety, supervisor’ adequate competences to carry out the job, effective training in improving one’s skills, appreciation for how managers run the organization, organizational stimuli to give one’s best on the job, and motivation to achieve organizational mission. Having an adequate equipment is positively associated with the satisfaction to work for the health care system at the standard statistical levels in all regions but C and D. The relationship between the satisfaction to work for one’s organization and the degree to which one’s work is manageable is positive at the 0.05 significance level for all regions except Region B, where the relationship is marginally significant ( p = 0.054 ). Employees’ perceptions that their suggestions for improvement are taken into consideration by their supervisors are significantly related to satisfaction in regions B, C, and D ( p = 0.009 , p = 0.008 , and p = 0.024 respectively). Region C is the only that displays a positive correlation between the satisfaction to serve the health systems and an agreement with the criteria adopted to evaluate individual performance, ceteris paribus ( p = 0.001 ). Regions C shows a positive correlation between information sharing at the organizational level and work satisfaction ( p = 0.003 ), whereas team-level information sharing is relevant in Region D ( p = 0.006 ). Then, awareness of the organizational goals is a relevant predictor of the satisfaction to work for the health service on one’s regional government in Region D ( p = 0.006 ).

Similarly, to Tables 3 and 6 , Table 8 displays the findings from an optimization algorithm aimed at improving the mean value of the satisfaction to work for the health service of one’s regional government by 5 percent. Improving positive perceptions about how managers run the organization and the motivation to achieve the organizational mission are correlated to an enhanced job satisfaction. In particular, the percentage improvement for the former statement are 11 percent for Region A, 7 percent for Region B, 13 percent for Region C, and 7 percent for Region D. As to the latter, the percentages are, respectively; 12, 15, 12, and 15. In Regions A and D, improving by 1 percent and 2 percent the mean value associated with the usefulness of training for competence enhancement are linked to a higher satisfaction. In Region B, instead, an improvement of the 6 percent of the organizational stimuli to give the best in one’s work correlated with an increased satisfaction. Lastly, improving personnel’s perceptions about workplace settings by 1 percent is associated with a higher satisfaction in Region B.

Overall, our analyses present three main key findings. First, within dependent variables, the correlates of job satisfaction tend to be the same across the health services of four regional governments. Second, the correlates of job satisfaction seem to differ among outcomes, namely hierarchical level at which employees’ satisfaction is measured. Third, context-specific associations emerge from our models.

Our work aimed at (i) investigating the correlates of health professionals’ job satisfaction at three hierarchical levels, namely satisfaction to work for one’s unit, organization, and health system of the regional government, and (ii) predicting how the improvement of the average value of correlates may relate with the improvement in the outcome variables. We employed large-scales observational surveys across healthcare systems in Italy. A series of logistic regressions reveal that environmental characteristics, management practices at the organizational level, and management practices at the team level correlates with work satisfaction. The pattern of results seems to replicate across outcome variables and healthcare systems. A series of optimization algorithms show that improving how the work is organized at the unit level, the degree to which employees perceive a sense of being part of a team with shared goals, and the supervisor’s abilities in carrying out the job may correlate with a better satisfaction to work for one’s unit. To the contrary, improving how managers perform their job tend to be associated with more satisfaction to work for one’s organization. As to the satisfaction to serve one’s regional health system, then, an improved work satisfaction correlates with an improved appreciation for the top management and the motivation to achieve the organizational mission.

The correlates that may relate to a higher job satisfaction are, therefore, in part different among hierarchical levels [ 2 , 18 , 52 ]. Within outcome variables, the largest variation in the correlates of job satisfaction is to the regional government level. Taken together, these findings align with two well established literature streams. On the one hand, attitudes and needs are so deeply seated in the human nature that they tend to be invariant for work satisfaction at the micro-level [ 8 , 43 ]. On the other hand, then, characteristics contingent to the macro-level may be relevant in prioritizing some attitudes and needs over others [ 6 , 9 , 16 ].

Further on the previous point, our work seems to suggest that all governance levels can play a role in employees’ job satisfaction, which continues to be a topic of interest for research syntheses attempts at the international level [ 53 , 54 , 55 ]. Some of the levers may overlap whereas other are different. As to the former, for instance, the quality and competence of managers at the unit and organizational level both correlated with work satisfaction. Thus, the mix of levers and the extent to which they are used may vary across regional healthcare system, which ultimately represent the highest governance level. Research on this consideration seems to have become even more prominent in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic [ 56 ].

Our study may provide a few contributions to extant scholarship and practice on job satisfaction in public service. Firstly, we investigate the correlates of satisfaction at three hierarchical levels. To the best of our knowledge, while most research analyzed satisfaction using hierarchical models [ 9 ], they tend to focus on one level only. Secondly, our analyses tap into many correlates of job satisfaction. This has the potential to uncover unexpected associations. Routine and large-scale survey on public employees’ perceptions provide a natural opportunity to engage in broad and deep understanding of organizational phenomena in the management of human resources. Thirdly, we introduce optimization models as a way to provide practitioners-friendly predictions on combinations of job satisfaction constructs that may be worth considering together to improve well-being. We are not aware of any such approach as far as managing public personnel is concerned. Fourthly, unlike most scholarship, our work is based on large-sample surveys and replication efforts aimed at the testing the generalizability of the findings.

Limitations

From a practitioner standpoint, the main limitation of our study is that it provides valuable insights targeted to decision makers at the regional level. In other words, it is beyond the scope of this investigation providing analyses at the organizational level. The degree to which findings aggregated by region generalize to results aggregated by organization within regions remains to be tested. Similarly, providing analysis across typologies of health professionals – also through customized survey instruments – is outside the scope of our work, though an avenue of future work that might be worth pursuing.

Then, we must acknowledge that our work suffers from the same limitations that affect observational studies and combine logistic regression analyses with optimization techniques. Most notably, we are unable to establish cause-effect relationships between job satisfaction and its determinants or consequences. As to the representativeness of the sample, the inability to compare demographic statistics between the sample and the exact population of reference is due to the general data protection regulation—defined at the European Union level and detailed in national states—that is fully binding when doing research with real organizations. The regulation prohibits analyzing variables before the data collection is closed and storing any information of non-respondents. Although, a response rate of 80% or more is desired to establish scientific validity in epidemiology, researchers demonstrated that reaching that response rate is not always possible and can lead to other problems [ 57 ]. In addition, the response rates in our samples appear to be in line with those of established surveys, such as the NHS survey – where the lates response rate reached 46% or the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey – which registered a 34% participation in the latest edition. Of course, readers are encouraged to always keep in mind this feature when considering our work. Furthermore, concerns about the generalizability of results across operations (importantly of the job satisfaction variables), settings, and samples are legitimate. Similarly, the generalizability of our findings from the optimization analyses to other healthcare systems around the world is unknown because, to the best of our knowledge, this has no prior in the literature. Unfortunately, we are unable, at the moment, to expand our work by adding data collected in other countries around the globe. We very much encourage replication studies, which would serve as rigorous and challenging external validity tests of the current work. In fact, replication efforts are common practice for other topics in the healthcare management domains. As to regression analyses, omitted variable biases may impinge on the validity of the findings. Moreover, our analyses are nested within regions and comparisons across regions must be done with caution. In fact, our logistic regressions do not account for variables such as socio-demographic items that may be distributed differently in different regional healthcare systems.

As to the optimization techniques, we acknowledge that its sensitivity to changes in the magnitude of regression coefficients and the lack of cost structure impose a warning in deriving implications for practice. Indeed, the optimization model selects the best combination of correlates that might associate with an improved outcome based on their mean value and relative strength. This influences the stability of the optimization results. Also, the algorithm identifies a set of factors that together generate a preset level of increase in the overall satisfaction measures. Although these results are optimal within the context in which they were presented, they may not be the best possible from a cost perspective. Lacking cost information, the algorithm assumes that the cost to improve each of the predictors is equivalent. Form a practical perspective, however, implementing changes suggested by our findings may not translate into the most cost-effective reforms. To the contrary, there might be other interventions that improve job satisfaction and are less costly.

Our work on the job satisfaction correlates of about 73,000 public health employees paves the way for a more extensive use of work satisfaction and organizational climate survey among typologies of mission-driven organizations. Whereas questionnaires measuring the attitudes and the perceptions of government personnel such as the Federal Employee Viewpoint in the United States or of health professionals such as the survey of National Health System in the United Kingdom are now spread around the globe, similar inquiry are not yet common practice in other public institutions. Our study may be a systematic attempt to fill this gap. Furthermore, we emphasize the need to use any such survey for managerial efforts aimed at improving the quality of the organization and the well-being of their employees. In this regard, the optimization model seems helpful in deriving implications for practice.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available to maintain employers' and employees' confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Engaging Public Employees for a High-Performing Civil Service. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2016.

Ommen O, Driller E, Köhler T, Kowalski C, Ernstmann N, Neumann M, ..., Pfaff H. The relationship between social capital in hospitals and physician job satisfaction. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9(1):1–9.

Tyssen R, Palmer KS, Solberg IB, Voltmer E, Frank E. Physicians’ perceptions of quality of care, professional autonomy, and job satisfaction in Canada, Norway, and the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1–10.

Article Google Scholar

Tsai Y. Relationship between organizational culture, leadership behavior and job satisfaction. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):1–9.

Schuster C, Weitzman L, Sass Mikkelsen K, Meyer‐Sahling J, Bersch K, et al. Responding to COVID‐19 Through Surveys of Public Servants. Public Adm Rev. 2020;80(5):792-6.

Batura N, Skordis-Worrall J, Thapa R, Basnyat R, Morrison J. Is the Job Satisfaction Survey a good tool to measure job satisfaction amongst health workers in Nepal? Results of a validation analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):1–13.

Fernandez S, Resh WG, Moldogaziev T, Oberfield ZW. Assessing the past and promise of the Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey for public management research: a research synthesis. Public Adm Rev. 2015;75(3):382–94.

Battaglio RP, Belle N, Cantarelli P. Self-determination theory goes public: experimental evidence on the causal relationship between psychological needs and job satisfaction. Public Manag Rev 2021:1–18.

Vainieri M, Ferre F, Giacomelli G, Nuti S. Explaining performance in health care: How and when top management competencies make the difference. Health Care Manage Rev. 2019;44(4):306.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Vainieri M, Seghieri C, Barchielli C. Influences over Italian nurses’ job satisfaction and willingness to recommend their workplace. Health Serv Manage Res. 2021;34(2):62–9.

Angelis J, Glenngård AH, Jordahl H. Management practices and the quality of primary care. Public Money Manag. 2021;41(3):264–71.

Moynihan DP, Fernandez S, Kim S, LeRoux KM, Piotrowski SJ, Wright BE, Yang K. Performance regimes amidst governance complexity. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2011;21(suppl_1):i141–55.

Thomann E, Trein P, Maggetti M. What’s the problem? Multilevel governance and problem-solving. Eur Policy Anal. 2019;5(1):37–57.

Bevan G, Evans A, Nuti S. Reputations count: why benchmarking performance is improving health care across the world. Health Econ Policy Law. 2019;14(2):141–61.

Giacomelli G, Vainieri M, Garzi R, Zamaro N. Organizational commitment across different institutional settings: how perceived procedural constraints frustrate self-sacrifice. Int Rev Adm Sci. 2020:0020852320949629.

Glenngård AH, Anell A. The impact of audit and feedback to support change behaviour in healthcare organisations-a cross-sectional qualitative study of primary care centre managers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–12.

Abner GB, Kim SY, Perry JL. Building evidence for public human resource management: Using middle range theory to link theory and data. Review of Public Personnel Administration. 2017;37(2):139–59.

Krueger P, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, Edward HG, Lewis D, Tjam E. Organization specific predictors of job satisfaction: findings from a Canadian multi-site quality of work life cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2002;2(1):1–8.

Raimondo E, Newcomer K. Mixed-methods inquiry in public administration: The interaction of theory, methodology, and praxis. Rev Public Pers Adm. 2017;37(2):183–201.

Brown AD, Sandoval GA, Levinton C, Blackstien-Hirsch P. Developing an efficient model to select emergency department patient satisfaction improvement strategies. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(1):3–10.

Sandoval GA, Levinton C, Blackstien-Hirsch P, Brown AD. Selecting predictors of cancer patients’ overall perceptions of the quality of care received. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(1):151–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Seghieri C, Sandoval GA, Brown AD, Nuti S. Where to focus efforts to improve overall ratings of care and willingness to return: the case of Tuscan emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(2):136–44.

Barsanti S, Walker K, Seghieri C, Rosa A, Wodchis WP. Consistency of priorities for quality improvement for nursing homes in Italy and Canada: A comparison of optimization models of resident satisfaction. Health Policy. 2017;121(8):862–9.

Walker RM, Brewer GA, Lee MJ, Petrovsky N, Van Witteloostuijn A. Best practice recommendations for replicating experiments in public administration. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2019;29(4):609–26.

Zhu L, Witko C, Meier KJ. The public administration manifesto II: Matching methods to theory and substance. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2019;29(2):287–98.

Chamberlain SA, Hoben M, Squires JE, Estabrooks CA. Individual and organizational predictors of health care aide job satisfaction in long term care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):1–9.

Cantarelli P, Belardinelli P, Belle N. A meta-analysis of job satisfaction correlates in the public administration literature. Rev Public Pers Adm. 2016;36(2):115–44.

Judge TA, Heller D, Mount MK. Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(3):530.

Judge TA, Thoresen CJ, Bono JE, Patton GK. The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(3):376.

Rainey HG. Understanding and managing public organizations. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley; 2009.

Google Scholar

Kim S. Individual-level factors and organizational performance in government organizations. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2005;15:245–61.

Smith PC, Kendall LM, Hulin CL. The measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally; 1969.

Locke EA. The nature and cause of job satisfaction. In: Dunnette MD, editor. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally; 1976. p. 1297–343.

Vigan FA, Giauque D. Job satisfaction in African public administrations: a systematic review. Int Rev Adm Sci. 2018;84(3):596–610.

Homberg F, McCarthy D, Tabvuma V. A meta-analysis of the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction. Public Adm Rev. 2015;75(5):711–22.

Judge TA, Piccolo RF, Podsakoff NP, Shaw JC, Rich BL. The relationship between pay and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the literature. J Vocat Behav. 2010;77(2):157–67.

Djukic M, Jun J, Kovner C, Brewer C, Fletcher J. Determinants of job satisfaction for novice nurse managers employed in hospitals. Health Care Manage Rev. 2017;42(2):172–83.

Kalisch B, Lee KH. Staffing and job satisfaction: nurses and nursing assistants. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22:465Y471.

Noblet AJ, Allisey AF, Nielsen IL, Cotton S, LaMontagne AD, Page KM. The work-based predictors of job engagement and job satisfaction experienced by community health professionals. Health Care Manage Rev. 2017;42(3):237–46.

Poikkeus T, Suhonen R, Katajisto J, Leino-Kilpi H. Relationships between organizational and individual support, nurses’ ethical competence, ethical safety, and work satisfaction. Health Care Manage Rev. 2020;45(1):83–93.

Vainieri M, Smaldone P, Rosa A, Carroll K. The role of collective labor contracts and individual characteristics on job satisfaction in Tuscan nursing homes. Health Care Manage Rev. 2019;44(3):224.

Zhang M, Yang R, Wang W, Gillespie J, Clarke S, Yan F. Job satisfaction of urban community health workers after the 2009 healthcare reform in China: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(1):14–21.

Chordiya R, Sabharwal M, Battaglio RP. Dispositional and organizational sources of job satisfaction: a cross-national study. Public Manag Rev. 2019;21(8):1101–24.

Esteve M, Schuster C, Albareda A, Losada C. The effects of doing more with less in the public sector: evidence from a large-scale survey. Public Adm Rev. 2017;77(4):544–53.

Cantarelli P, Belle N, Longo F. Exploring the motivational bases of public mission-driven professions using a sequential-explanatory design. Public Manag Rev. 2019;22(10):1535-59.

Belle N, Cantarelli P. The role of motivation and leadership in public employees’ job preferences: evidence from two discrete choice experiments. Int Public Manag J. 2018;21(2):191–212.

Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. https://www.opm.gov/fevs/ [Last accessed March 2023].

Nuti S. La valutazione della performance in Sanità, Edizione Il Mulino. 2008.

Pizzini S, Furlan M. L’esercizio delle competenze manageriali e il clima interno. Il caso del Servizio Sanitario della Toscana. Psicologia Sociale. 2012;3(1):429–46.

Giacomelli G, Ferré F, Furlan M, Nuti S. Involving hybrid professionals in top management decision-making: How managerial training can make the difference. Health Serv Manage Res. 2019;32(4):168–79.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Vardè AM, Mennini FS. Analysis evolution of personnel in the Italian National Healthcare Service with a view to health planning. MECOSAN. 2019;110:9–43. https://doi.org/10.3280/MESA2019-110002 .

Aloisio LD, Gifford WA, McGilton KS, Lalonde M, Estabrooks CA, Squires JE. Individual and organizational predictors of allied healthcare providers’ job satisfaction in residential long-term care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–18.

van Diepen C, Fors A, Ekman I, Hensing G. Association between person-centred care and healthcare providers’ job satisfaction and work-related health: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e042658.

Cunningham R, Westover J, Harvey J. Drivers of job satisfaction among healthcare professionals: a quantitative review. Int J Healthcare Manag. 2022:1–9.

Rowan BL, Anjara S, De Brún A, MacDonald S, Kearns EC, Marnane M, McAuliffe E. The impact of huddles on a multidisciplinary healthcare teams’ work engagement, teamwork and job satisfaction: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2022;28(3):382–93.

Sharma A, Borah SB, Moses AC. Responses to COVID-19: the role of governance, healthcare infrastructure, and learning from past pandemics. J Bus Res. 2021;122:597–607.

Hendra R, Hill A. Rethinking response rates: new evidence of little relationship between survey response rates and nonresponse bias. Eval Rev. 2019;43(5):307–30.

Download references

Acknowledgements

All authors are grateful to the Management and Healthcare Laboratory (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna) and its Network delle Regioni .

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Management and Healthcare Laboratory, Institute of Management and L’EMbeDS, Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, Piazza Martiri Della Libertà 33, Pisa, 56127, Italy

Paola Cantarelli, Milena Vainieri & Chiara Seghieri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All Authors contributed equally. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paola Cantarelli .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval is unnecessary according to national legislation D. Lgs. 150/2009, art. 14.

The Italian Legislative Decree 196/2003 Code of Privacy requires public institutions to conduct employee viewpoint surveys and authorizes the use of employees’ data to evaluate the quality of service and identify organizational improvement actions. This legislative act does not ask for permission from an Ethical Committee when interviewing workers with regard to job satisfaction and related perceptions. This survey is considered as a service quality measurement activity and does not require an Ethics committee involvement. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, in written form. In other words, as human data are used, we confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Cantarelli, P., Vainieri, M. & Seghieri, C. The management of healthcare employees’ job satisfaction: optimization analyses from a series of large-scale surveys. BMC Health Serv Res 23 , 428 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09426-3

Download citation

Received : 18 January 2023

Accepted : 19 April 2023

Published : 03 May 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09426-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Job satisfaction

- Healthcare employees

- Healthcare governance

- Large-scale viewpoint surveys

- Optimization analysis

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job involvement: the mediating role of job involvement.

- Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia

We conducted an empirical study aimed at identifying and quantifying the relationship between work characteristics, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, job involvement and organizational policies and procedures in the transition economy of Serbia, South Eastern Europe. The study, which included 566 persons, employed by 8 companies, revealed that existing models of work motivation need to be adapted to fit the empirical data, resulting in a revised research model elaborated in the paper. In the proposed model, job involvement partially mediates the effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment. Job satisfaction in Serbia is affected by work characteristics but, contrary to many studies conducted in developed economies, organizational policies and procedures do not seem significantly affect employee satisfaction.

1. Introduction

In the current climate of turbulent changes, companies have begun to realize that the employees represent their most valuable asset ( Glen, 2006 ; Govaerts et al., 2011 ; Fulmer and Ployhart, 2014 ; Vomberg et al., 2015 ; Millar et al., 2017 ). Satisfied and motivated employees are imperative for contemporary business and a key factor that separates successful companies from the alternative. When considering job satisfaction and work motivation in general, of particular interest are the distinctive traits of these concepts in transition economies.

Serbia is a country that finds itself at the center of the South East region of Europe (SEE), which is still in the state of transition. Here transition refers to the generally accepted concept, which implies economic and political changes introduced by former socialist countries in Europe and beyond (e.g., China) after the years of economic stagnation and recession in the 1980's, in the attempt to move their economy from centralized to market-oriented principles ( Ratkovic-Njegovan and Grubic-Nesic, 2015 ). Serbia exemplifies many of the problems faced by the SEE region as a whole, but also faces a number of problems uniquely related to the legacy of its past. Due to international economic sanctions, the country was isolated for most of the 1990s, and NATO air strikes, related to the Kosovo conflict and carried out in 1999, caused significant damage to the industry and economy. Transitioning to democracy in October 2000, Serbia embarked on a period of economic recovery, helped by the introduction of long overdue reforms, major inflows of foreign investment and substantial assistance from international funding institutions and others in the international community. However, the growth model on which Serbia and other SEE countries relied between 2001 and 2008, being based mainly on rapid capital inflows, a credit-fueled domestic demand boom and high current account deficit (above 20% of GDP in 2008), was not accompanied by the necessary progress in structural and institutional reforms to make this model sustainable ( Uvalic, 2013 ). The central issue of the transition process in Serbia and other such countries is privatization of public enterprises, which in Serbia ran slowly and with a number of interruptions, failures and restarts ( Radun et al., 2015 ). The process led the Serbian industry into a state of industrial collapse, i.e., deindustrialization. Today there are less than 400,000 employees working in the industry in Serbia and the overall unemployment rate exceeds 26% ( Milisavljevic et al., 2013 ). The average growth of Serbia's GDP in the last 5 years was very low, at 0.6% per year, but has reached 2.7% in 2016 ( GDP, 2017 ). The structure of the GDP by sector in 2015 was: services 60.5%, industry 31.4%, and agriculture 8.2% ( Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2017 ).

Taking into account the specific adversities faced by businesses in Serbia, we formulated two main research questions as a starting point for the analysis of the problem of work motivation in Serbia:

1. To what extent are the previously developed models of work motivation (such as the model of Locke and Latham, 2004 ) applicable to the transition economy and business practices in Serbia?

2. What is the nature of the relationships between different segments of work motivation (job satisfaction, organizational commitment, job involvement and work characteristics)?

The Hawthorn experiment, conducted in early 1930s ( Mayo, 1933 ), spurred the interest of organizational behavior researchers into the problem of work motivation. Although Hawthorn focused mainly on the problems of increasing the productivity and the effects of supervision, incentives and the changing work conditions, his study had significant repercussions on the research of work motivation. All modern theories of work motivation stem from his study.

Building on his work, Maslow (1943) published his Hierarchy of Needs theory, which remains to this day the most cited and well known of all work motivation theories according to Denhardt et al. (2012) . Maslow's theory is a content-based theory , belonging to a group of approaches which also includes the ERG Theory by Alderfer (1969) , the Achievement Motivation Theory, Motivation-Hygiene Theory and the Role Motivation Theory.

These theories focus on attempting to uncover what the needs and motives that cause people to act in a certain way, within the organization, are. They do not concern themselves with the process humans use to fulfill their needs, but attempt to identify variables which influence this fulfillment. Thus, these theories are often referred to as individual theories , as they ignore the organizational aspects of work motivation, such as job characteristics or working environment, but concentrate on the individual and the influence of an individual's needs on work motivation.

The approach is contrasted by the process theories of work motivation, which take the view that the concept of needs is not enough to explain the studied phenomenon and include expectations, values, perception, as important aspects needed to explain why people behave in certain ways and why they are willing to invest effort to achieve their goals. The process theories include: Theory of Work and Motivation ( Vroom, 1964 ), Goal Setting Theory ( Locke, 1968 ), Equity Theory ( Adams, 1963 ), as well as the The Porter-Lawler Model ( Porter and Lawler, 1968 ).

Each of these theories has its limitations and, while they do not contradict each other, they focus on different aspects of the motivation process. This is the reason why lately they have been several attempts to create an integrated theory of work motivation, which would encompass all the relevant elements of different basic theories and explain most processes taking place within the domain of work motivation, the process of motivation, as well as employee expectations ( Donovan, 2001 ; Mitchell and Daniels, 2002 ; Locke and Latham, 2004 ). One of the most influential integrated theories is the theory proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) , which represents the basis for the study presented in this paper.

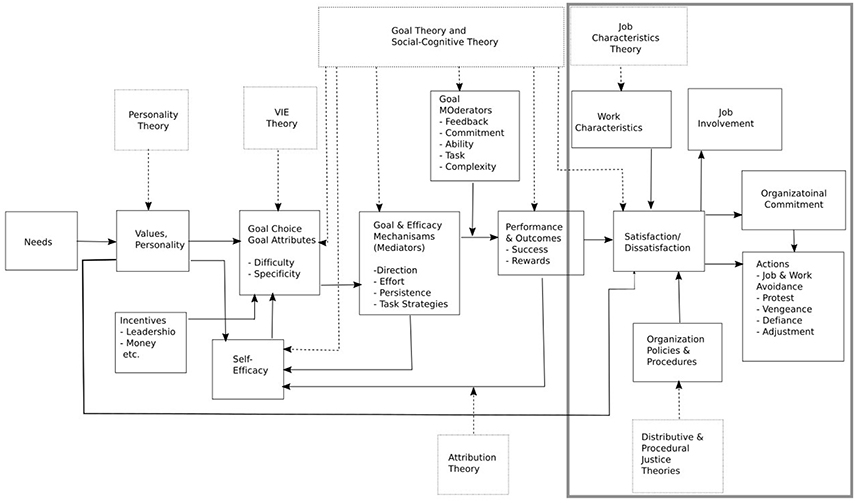

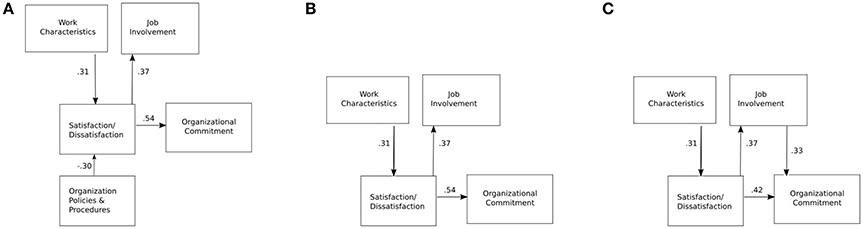

The model of Locke and Latham is show in Figure 1 . As the figure shows, it includes individual needs, values and motive, as well as personality. Incorporating the theory of expectations, the goal-setting theory and the social-cognitive theory, it focuses on goal setting, goals themselves and self-efficiency. Performance, by way of achievements and rewards, affects job satisfaction. The model defines relations between different constructs and, in particular, that job satisfaction is affected by the job characteristics and organizational policy and procedures and that it, in turn, affects organizational commitment and job involvement. Locke and Latham suggested that the theory they proposed needs more stringent empirical validation. In the study presented here, we take a closer look at the part of their theory which addresses the relationship between job satisfaction, involvement and organizational commitment. The results of the empirical study conducted in industrial systems suggest that this part of the model needs to be improved to reflect the mediating role of job involvement in the process through which job satisfaction influences organizational commitment.

Figure 1 . Diagram of the Latham and Locke model. The frame on the right indicates the part of the model the current study focuses on.

Job satisfaction is one of the most researched phenomena in the domain of human resource management and organizational behavior. It is commonly defined as a “pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of oneś job or job experiences” ( Schneider and Snyder, 1975 ; Locke, 1976 ). Job satisfaction is a key element of work motivation, which is a fundamental determinant of one's behavior in an organization.

Organizational commitment, on the other hand, represents the degree to which the employees identify with the organization in which they work, how engaged they are in the organization and whether they are ready leave it ( Greenberg and Baron, 2008 ). Several studies have demonstrated that there is a strong connection between organizational commitment, job satisfaction and fluctuation ( Porter et al., 1974 ), as well as that people who are more committed to an organization are less likely to leave their job. Organizational commitment can be thought of as an extension of job satisfaction, as it deals with the positive attitude that an employee has, not toward her own job, but toward the organization. The emotions, however, are much stronger in the case of organizational commitment and it is characterized by the attachment of the employee to the organization and readiness to make sacrifices for the organization.

The link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment has been researched relatively frequently ( Mathieu and Zajac, 1990 ; Martin and Bennett, 1996 ; Meyer et al., 2002 ; Falkenburg and Schyns, 2007 ; Moynihan and Pandey, 2007 ; Morrow, 2011 ). The research consensus is that the link exists, but there is controversy about the direction of the relationship. Some research supports the hypothesis that job satisfaction predicts organizational commitment ( Stevens et al., 1978 ; Angle and Perry, 1983 ; Williams and Hazer, 1986 ; Tsai and Huang, 2008 ; Yang and Chang, 2008 ; Yücel, 2012 ; Valaei et al., 2016 ), as is the case in the study presented in this paper. Other studies suggest that the organizational commitment is an antecedent to job satisfaction ( Price and Mueller, 1981 ; Bateman and Strasser, 1984 ; Curry et al., 1986 ; Vandenberg and Lance, 1992 ).

In our study, job involvement represents a type of attitude toward work and is usually defined as the degree to which one identifies psychologically with one's work, i.e., how much importance one places on their work. A distinction should be made between work involvement and job involvement. Work involvement is conditioned by the process of early socialization and relates to the values one has wrt. work and its benefits, while job involvement relates to the current job and is conditioned with the one's current employment situation and to what extent it meets one's needs ( Brown, 1996 ).

2.1. Research Method

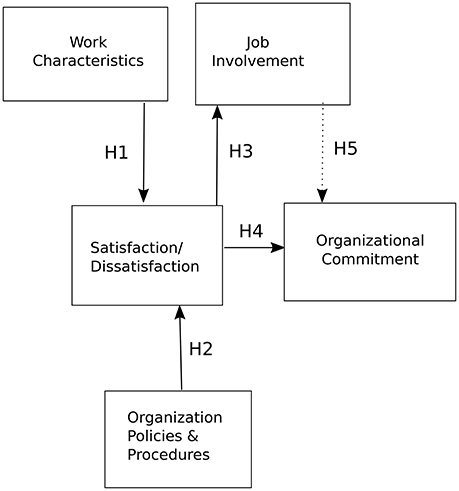

Based on the relevant literature, the results of recent studies and the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) , we designed a conceptual model shown in Figure 2 . The model was then used to formulate the following hypotheses:

H0 - Work motivation factors, such as organizational commitment, job involvement, job satisfaction and work characteristics, represent interlinked significant indicators of work motivation in the organizations examined.

H1 - Work characteristics will have a positive relationship with job satisfaction.

H2 - Organizational policies and procedures will have a positive relationship with job satisfaction.

H3 - Job satisfaction will have a positive relationship with job involvement.

H4 - Job satisfaction will have a positive relationship with organizational commitment.

H5 - Job involvement will have a mediating role between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Figure 2 . The research model.

2.2. Participants

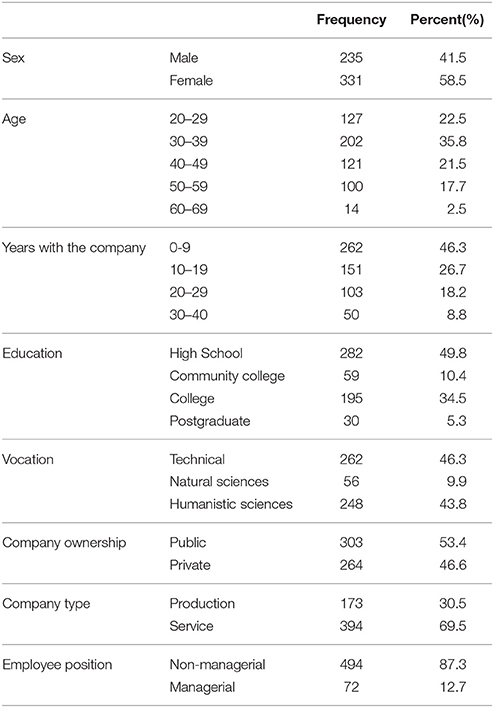

For the purpose of this study, 125 organizations from the Serbian Chamber of Commerce database ( www.stat.gov.rs ) were randomly selected to take part in this study. Each organization was contacted and an invitation letter was sent. Eight companies expressed a desire to take part and provided contact details for 700 of their employees. The questionnaire distribution process was conducted according to Dillman's approach ( Dillman, 2011 ). Thus, the initial questionnaire dissemination process was followed by a series of follow-up email reminders, if required. After a 2-month period, out of 625 received, 566 responses were valid. Therefore, the study included 566 persons, 235 males (42%) and 331 women (58%) employed by 8 companies located in Serbia, Eastern Europe.

The sample encompassed staff from both public (53%) and private (47%) companies in manufacturing (31%) and service (69%) industries. The companies were of varied size and had between 150 and 6,500 employees, 3 of them (37.5%) medium-sized (<250 employees) and 5 (62.5%) large enterprises.

For the sake of representativeness, the sample consisted of respondents across different categories of: age, years of work service and education. The age of the individuals was between 20 and 62 years of age and we divided them into 5 categories as shown in Table 1 . The table provides the number of persons per category and the relative size of the category wrt. to the whole sample. In the same table, a similar breakdown is shown in terms of years a person spent with the company, their education and the type of the position they occupy within the company (managerial or not).

Table 1 . Data sample characteristics.

2.3. Ethics Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the Law on Personal Data Protection of the Republic of Serbia and the Codex of Professional Ethics of the University of Novi Sad. The relevant ethics committee is the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Technical Sciences of the University of Novi Sad.

All participants took part voluntarily and were free to fill in the questionnaire or not.

The questionnaire included a cover sheet explaining the aim of the research, ways in which the data will be used and the anonymous nature of the survey.

2.4. Measures

This study is based on a self reported questionnaire as a research instrument.

The questionnaire was developed in line with previous empirical findings, theoretical foundations and relevant literature recommendations ( Brayfield and Rothe, 1951 ; Weiss et al., 1967 ; Mowday et al., 1979 ; Kanungo, 1982 ; Fields, 2002 ). We then conducted a face validity check. Based on the results, some minor corrections were made, in accordance with the recommendations provided by university professors. After that, the pilot test was conducted with 2 companies. Managers from each of these companies were asked to assess the questionnaire. Generally, there were not any major complaints. Most of the questions were meaningful, clearly written and understandable. The final research instrument contained 86 items. For acquiring respondents' subjective estimates, a five-point Likert scale was used.

The questionnaire took about 30 min to fill in. It consisted of: 10 general demographic questions, 20 questions from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ), 15 questions from the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ), 10 questions from the Job Involvement Questionnaire (JIQ), 18 questions of the Brayfield-Rothe Job Satisfaction Scale (JSS), 6 questions of the Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS) and 7 additional original questions related to the rules and procedures within the organization.

The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ), 20 items short form ( Weiss et al., 1967 ), was used to gather data about job satisfaction of participants. The MSQ – short version items, are rated on 5-points Likert scale (1 very dissatisfied with this aspect of my job, and 5 – very satisfied with this aspect of my job) with two subscales measuring intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction.

Organizational commitment was measured using The Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ). It is a 15-item scale developed by Mowday, Steers and Porter ( Mowday et al., 1979 ) and uses a 5-point Likert type response format, with 3 factors that can describe this commitment: willingness to exert effort, desire to maintain membership in the organization, and acceptance of organizational values.

The most commonly used measure of job involvement has been the Job Involvement Questionnaire (JIQ, Kanungo, 1982 ), 10-items scale designed to assess how participants feel toward their present job. The response scale on a 5-point scale varied between “strongly disagree/not applicable to me” to “strongly agree/fully applicable”.

The Brayfield and Rothe's 18-item Job Satisfaction Index (JSI, Brayfield and Rothe, 1951 ) was used to measure overall job satisfaction, operationalized on five-point Likert scale.

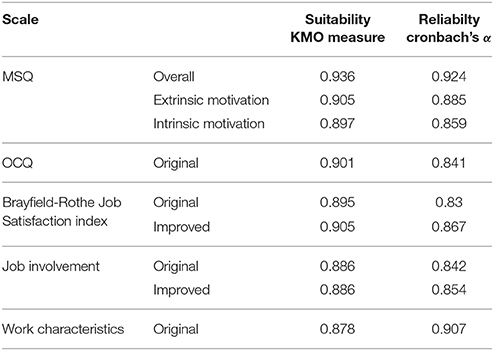

Psychometric analysis conducted showed that all the questionnaires were adequately reliable (Cronbach alpha > 0.7). The suitability of the data for factor analysis has been confirmed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Test (see Table 2 ).

Table 2 . Basic psychometric characteristics of the instruments.

For further analysis we used summary scores for the different scales. Job satisfaction was represented with the overall score of MSQ, as the data analysis revealed a strong connection between the extrinsic and intrinsic motivators. The overall score on the OCQ was used as a measure of organizational commitment, while the score on JDS was used to reflect job characteristics. The JSS and JIQ scales have been modified, by eliminating a few questions, in order to improve reliability and suitability for factor analysis.

Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS software. The SPSS Amos structural equation modeling software was used to create the Structural Equation Models (SEMs).

The data was first checked for outliers using box-plot analysis. The only outliers identified were related to the years of employment, but these seem to be consistent to what is expected in practice in Serbia, so no observations needed to be removed from the dataset.

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Although research dimensions were empirically validated and confirmed in several prior studies, to the best of our knowledge, the empirical confirmation of the research instrument (i.e., questionnaire) and its constituents in the case of Serbia and South-Eastern Europe is quite scarce. Furthermore, the conditions in which previous studies were conducted could vary between research populations. Also, such differences could affect the structure of the research concepts. Thus, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted in order to empirically validate the structure of research dimensions and to test the research instrument, within the context of the research population of South-Eastern Europe and Serbia.

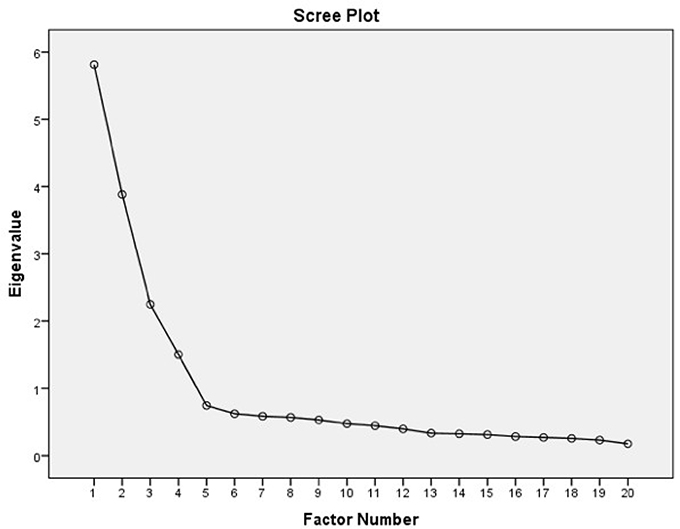

Using the maximum likelihood method we identified four factors, which account for 67% of the variance present in the data. The scree plot of the results of the analysis is shown in Figure 3 . As the figure shows, we retained the factors above the inflection point.

Figure 3 . Scree plot of the EFA results.

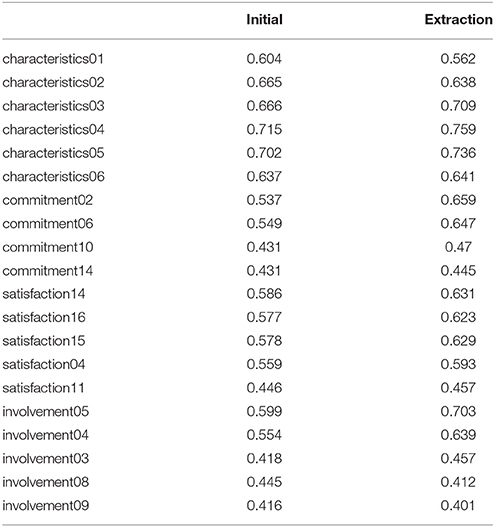

The communalities for the variables loading into the factors are shown in Table 3 and the questions corresponding to our variables are listed in Table 4 . Initial communalities are estimates of the proportion of variance in each variable accounted for by all components (factors) identified, while the extraction communalities refer to the part of the variance explained by the four factors extracted. The model explains more of the variance then the initial factors, for all but the last variable.

Table 3 . Communalities.

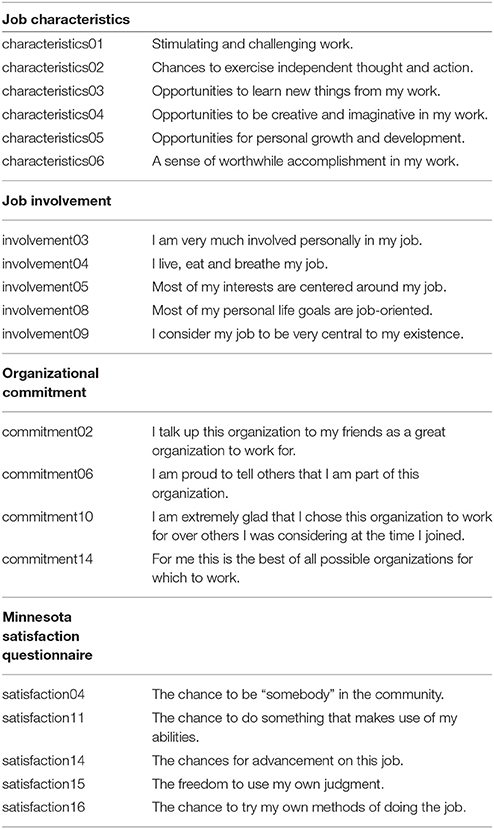

Table 4 . Questions that build our constructs.

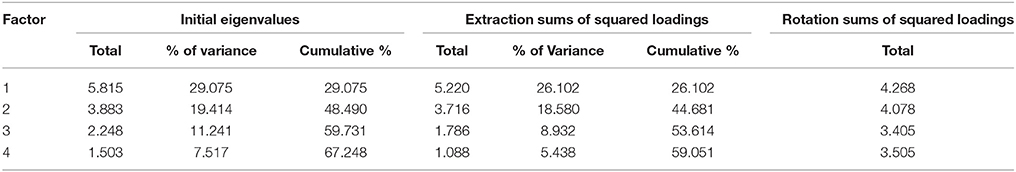

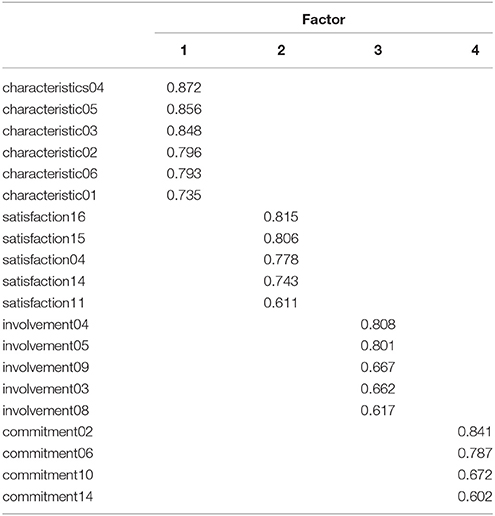

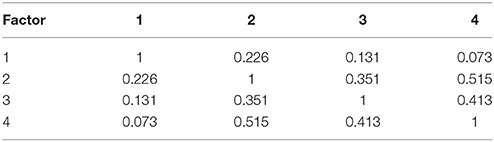

More detailed results of the EFA for the four factors, are shown in Table 5 . The unique loadings of specific items measured with the different questions in the questionnaire on the factors identified are shown in the pattern matrix (Table 6 ). As the table shows, each factor is loaded into by items that were designed to measure a specific construct and there are no cross-loadings. The first factor corresponds to job characteristics, second to job satisfaction, third to job involvement and the final to organizational commitment. The correlation between the factors is relatively low and shown in Table 7 .

Table 5 . Total variance explained by the dominant factors.

Table 6 . Pattern matrix for the factors identified.

Table 7 . Factor correlation matrix.

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In the next part of our analysis we used Structural Equation Modeling to validate and improve a part of the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) that focuses on work characteristics, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job involvement.

Although the EFA suggest the existence of four, not five, dominant factors in the model, diverging from the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) , in our initial experiments we used their original model, shown in Figure 4A , taking into account also organizational policies and procedures.

Figure 4 . The evolution of our model (the path coefficients are standardized): (A) the initial model based on Locke and Latham (2004) , (B) no partial mediation, and (C) partial mediation introduced.

In this (default) model, the only independent variable are the job characteristics. The standardized regression coefficients shown in Figure 4A (we show standardized coefficients throughout Figure 4 ) indicate that the relationship between the satisfaction and organizational commitment seems to be stronger (standard coefficient value of 0.54) than the one between satisfaction and involvement (standard coefficient value of 0.37). The effect of job characteristics and policies and procedures on the employee satisfaction seems to be balanced (standard coefficient values of 0.31 and 0.30, respectively).

The default model does not fit our data well. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) for this model is 0.759, the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) is 0.598, while the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is 0.192.

A more detailed analysis of the model revealed that it could indeed (as the EFA suggests) be improved by eliminating the organizational policies and procedures variable, as it has a high residual covariance with job involvement (−3.071) and organizational commitment (−4.934).

We therefore propose to eliminate the “Organizational policies and procedures” variable from the model. Dropping the variable resulted in an improved model shown in Figure 4B . The improved model fits the data better, but the fit is still not good ( RMSEA = 0.125, CFI = 0.915 and TLI = 0.830).

We then hypothesized that job involvement influences organizational commitment, yielding the final model tested in this study (Figure 4C ). This model turned out to be the one that fits our data very well ( RMSEA = 0.000, CFI = 1 and TLI = 1.015).

4. Mediation Analysis

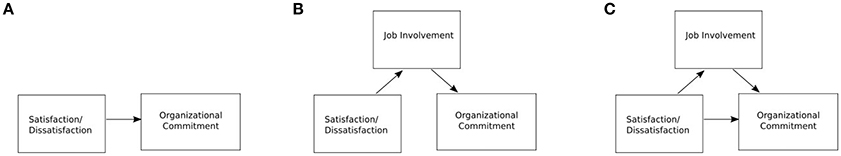

In the final part of the study we conducted the mediation analysis, to understand the relationship between job satisfaction, job involvement and organizational commitment. We used bootstrapping, based on 5000 samples and the confidence interval of 95%.

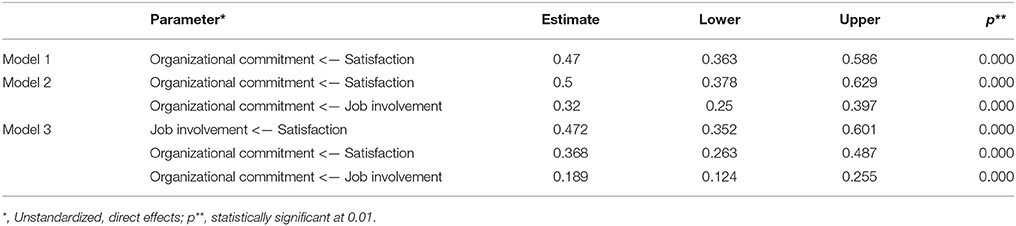

We started with a model that contains just one relation between satisfaction and commitment (Figure 5A ), then tested for full mediation (Figure 5B ) and finally partial mediation as indicated in out proposed model (Figure 5C ). The unstandardized, direct effect regression weights and the p -values obtained in these experiments are shown in Table 8 . As the p -values show, all the connections in our three models are significant and that they remain so throughout the evolution of the model. Therefore, job involvement mediates the influence of satisfaction on organizational commitment, but this is a partial mediation and a major part of the effect of satisfaction on the organizational commitment is achieved directly.

Figure 5 . Mediation analysis models. (A) , Model 1; (B) , Model 2; (C) , Model 3.

Table 8 . Mediation analysis regression weights.

5. Discussion

We conducted an empirical study aimed at exploring the relationship between employee satisfaction, job involvement, organizational commitment, work characteristics and organizational policies and procedures.

Based on the relevant scientific literature, recent studies in the area and the integrative model of work motivation of Locke and Latham (2004) , we have formulated an initial conceptual model for our research and hypothesized the connections between the relevant variables. The initial model has been improved iteratively, with the goal of increasing its fit to the empirical data collected in the study.

Starting from the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) we determined that their model does not fit our experimental data well and that we observe a connection between job involvement that is not present in their model. In addition, our data does not support the hypothesis that organizational procedures and policies affect employee satisfaction in the organizations considered. As a result we propose a 4 factor model shown in Figure 4C for the relationship between the concepts of work characteristics, employee satisfaction, job involvement and organizational commitment.

We analyzed the results of the study based on 1 general and 5 specific hypotheses. The research confirms that there is a link between work characteristics and job satisfaction (H1), but that it is weak, suggesting that a dominant effect of the material factors of motivation exists.

We have also determined that there is a connection between the rules and procedures variable (H2) and the rest of the variables, indicating that it should be considered in future studies, but that the constructs need to be operationalized better.

The third specific hypothesis (H3) that job satisfaction has a positive relationship with job involvement has been confirmed and we have observed that extrinsic work motivation has a stronger effect than intrinsic, which can be explained by low wages and insufficient funds for everyday life. Other research has confirmed this link ( Govender and Parumasur, 2010 ) and showed that most of the employee motivation dimensions have significant links with the dimensions of job involvement (9 out of 10 pairs).

The fourth specific hypothesis (H4 - Job satisfaction will have a positive relationship with organizational commitment) has also been confirmed and we can conclude that a positive relationship exists, which is in line with recent research in this area. The subscale focused on identification with the organization is strongly connected with both intrinsic and extrinsic factors of job satisfaction, but this cannot be said for the subscale focused on organizational attachment. Our research supports the existence of a weak connection between job satisfaction and organizational attachment, both when intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction is considered as a motivator. A study of work motivation and organizational commitment conducted in Bulgaria (Serbia's neighbor) showed that extrinsic factors are key sources of organizational commitment ( Roe et al., 2000 ), as well as that job involvement and the chances for the fulfillment o higher-order needs pay a very important part in the motivation of the employees.