- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Public Health

- About the Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, methodology.

- < Previous

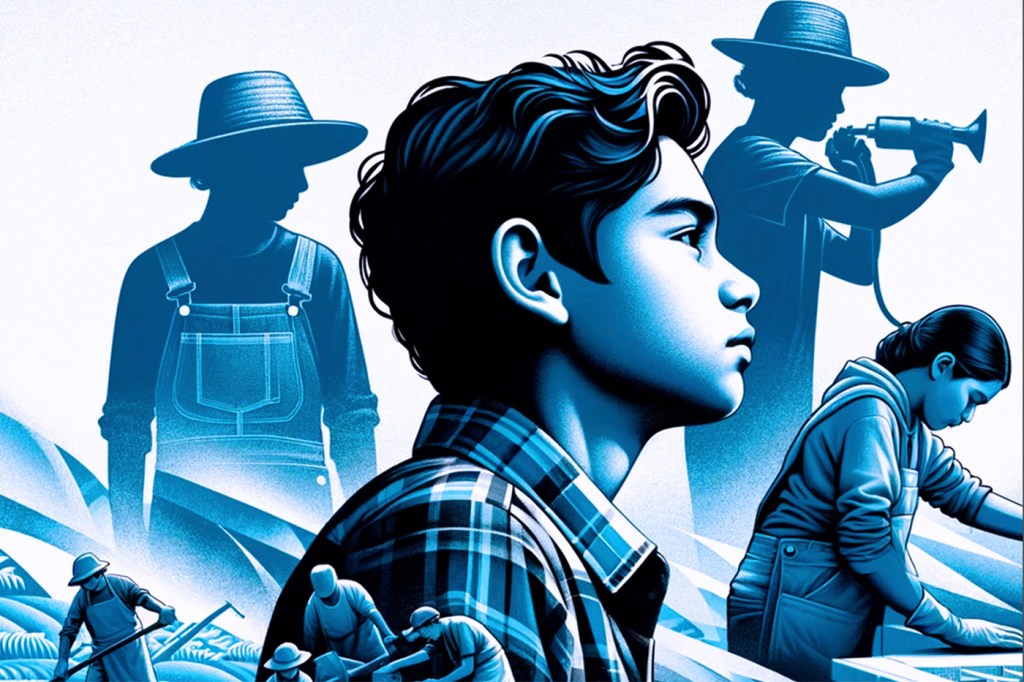

Child labor and health: a systematic literature review of the impacts of child labor on child’s health in low- and middle-income countries

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Abdalla Ibrahim, Salma M Abdalla, Mohammed Jafer, Jihad Abdelgadir, Nanne de Vries, Child labor and health: a systematic literature review of the impacts of child labor on child’s health in low- and middle-income countries, Journal of Public Health , Volume 41, Issue 1, March 2019, Pages 18–26, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdy018

- Permissions Icon Permissions

To summarize current evidence on the impacts of child labor on physical and mental health.

We searched PubMed and ScienceDirect for studies that included participants aged 18 years or less, conducted in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and reported quantitative data. Two independent reviewers conducted data extraction and assessment of study quality.

A total of 25 studies were identified, the majority of which were cross-sectional. Child labor was found to be associated with a number of adverse health outcomes, including but not limited to poor growth, malnutrition, higher incidence of infectious and system-specific diseases, behavioral and emotional disorders, and decreased coping efficacy. Quality of included studies was rated as fair to good.

Child labor remains a major public health concern in LMICs, being associated with adverse physical and mental health outcomes. Current efforts against child labor need to be revisited, at least in LMICs. Further studies following a longitudinal design, and using common methods to assess the health impact of child labor in different country contexts would inform policy making.

For decades, child labor has been an important global issue associated with inadequate educational opportunities, poverty and gender inequality. 1 Not all types of work carried out by children are considered child labor. Engagement of children or adolescents in work with no influence on their health and schooling is usually regarded positive. The International Labor Organization (ILO) describes child labor as ‘work that deprives children of their childhood, potential and dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development’. 2 This definition includes types of work that are mentally, physically, socially or morally harmful to children; or disrupts schooling.

The topic gained scientific attention with the industrial revolution. Research conducted in the UK, because of adverse outcomes in children, resulted in acts for child labor in 18 02. 3 Many countries followed the UK, in recognition of the associated health risks. The ILO took its first stance in 1973 by setting the minimum age for work. 4 Nevertheless, the ILO and other international organizations that target the issue failed to achieve goals. Child labor was part of the Millennium Development Goals, adopted by 191 nations in 20 00 5 to be achieved by 2015. Subsequently, child labor was included in the Sustainable Development Goals, 6 which explicitly calls for eradication of child labor by 2030.

Despite the reported decline in child labor from 1995 to 2000, it remains a major concern. In 2016, it was estimated that ~150 million children under the age of 14 are engaged in labor worldwide, with most of them working under circumstances that denies them a playful childhood and jeopardize their health. 7 Most working children are 11–14 years, but around 60 million are 5–11 years old. 7 There are no exact numbers of the distribution of child labor globally; however, available statistics show that 96% of child workers are in Africa, Asia and Latin America. 1

Research into the impacts of child labor suggests several associations between child labor and adverse health outcomes. Parker 1 reported that child labor is associated with certain exposures like silica in industries, and HIV infection in prostitution. Additionally, as child labor is associated with maternal illiteracy and poverty, children who work are more susceptible to malnutrition, 1 which predisposes them to various diseases.

A meta-analysis on the topic was published in 20 07. 8 However, authors reported only an association of child labor with higher mortality and morbidity than in the general population, without reporting individual outcome specific effects. 8 Another meta-analysis investigated the effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including child labor, on health. They reported that ACEs are risk factors for many adverse health outcomes. 9

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that attempts to summarize current evidence on the impacts of child labor on both physical and mental health, based on specific outcomes. We review the most recent evidence on the health impacts of child labor in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) according to the World Bank classification. We provide an informative summary of current studies of the impacts of child labor, and reflect upon the progress of anti-child labor policies and laws.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed and ScienceDirect databases. Search was restricted to publications from year 1997 onwards. Only studies written in English were considered. Our search algorithm was [(‘child labor’ OR ‘child labor’ OR ‘working children’ OR ‘occupational health’ OR ‘Adolescent work’ OR ‘working adolescents’) AND (Health OR medical)]. The first third of the algorithm was assigned to titles/abstracts to ensure relevance of the studies retrieved, while the rest of the terms were not. On PubMed, we added […AND (poverty OR ‘low income’ OR ‘developing countries’)] to increase the specificity of results; otherwise, the search results were ~60 times more, with the majority of studies being irrelevant.

Study selection

Studies that met the following criteria were considered eligible: sample age 18 years or less; study was conducted in LMICs; and quantitative data was reported.

Two authors reviewed the titles obtained, a.o. to exclude studies related to ‘medical child labor’ as in childbirth. Abstracts of papers retained were reviewed, and subsequently full studies were assessed for inclusion criteria. Two authors assessed the quality of studies using Downs and Black tool for quality assessment. 10 The tool includes 27 items, yet not all items fit every study. In such cases, we used only relevant items. Total score was the number of items positively evaluated. Studies were ranked accordingly (poor, fair, good) (Table 1 ).

Characteristics of studies included

* The quality is based on the percentage of Downs and Black 10 tool, < 50% = poor, 50–75% = fair, > 75% = good.

** BMI, body mass index.

*** HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Data extraction and management

Two authors extracted the data using a standardized data extraction form. It included focus of study (i.e. physical and/or mental health), exposure (type of child labor), country of study, age group, gender, study design, reported measures (independent variables) and outcome measures (Table 1 ). The extraction form was piloted to ensure standardization of data collection. A third author then reviewed extracted data. Disagreements were solved by discussion.

Search results

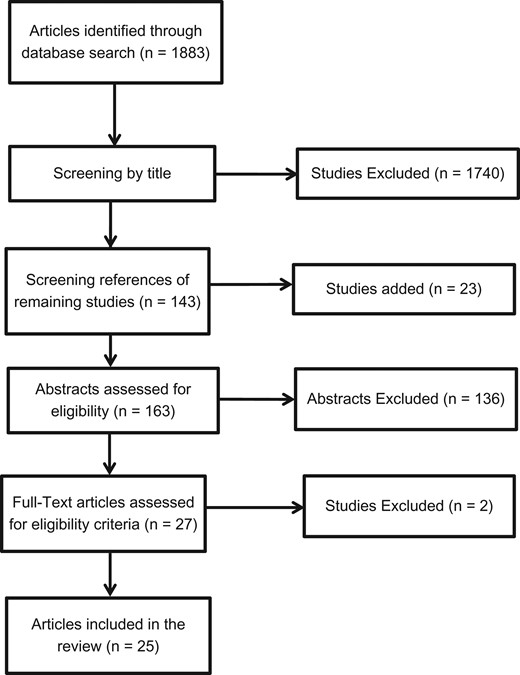

A flow diagram (Fig. 1 ) shows the studies selection process. We retrieved 1050 studies on PubMed and 833 studies on Science Direct, with no duplicates in the search results. We also retrieved 23 studies through screening of the references, following the screening by title of retrieved studies. By reviewing title and abstract, 1879 studies were excluded. After full assessment of the remaining studies, 25 were included.

Study selection process.

Characteristics of included studies

Among the included studies ten documented only prevalence estimates of physical diseases, six documented mental and psychosocial health including abuse, and nine reported the prevalence of both mental and physical health impacts (Table 1 ). In total, 24 studies were conducted in one country; one study included data from the Living Standard Measurement Study of 83 LMIC. 8

In total, 12 studies compared outcomes between working children and a control group (Table 1 ). Concerning physical health, many studies reported the prevalence of general symptoms (fever, cough and stunting) or diseases (malnutrition, anemia and infectious diseases). Alternatively, some studies documented prevalence of illnesses or symptoms hypothesized to be associated with child labor (Table 1 ). The majority of studies focusing on physical health conducted clinical examination or collected blood samples.

Concerning mental and psychosocial health, the outcomes documented included abuse with its different forms, coping efficacy, emotional disturbances, mood and anxiety disorders. The outcomes were measured based on self-reporting and using validated measures, for example, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), in local languages.

The majority of studies were ranked as of ‘good quality’, with seven ranked ‘fair’ and one ranked ‘poor’ (Table 1 ). The majority of them also had mixed-gender samples, with only one study restricted to females. 24 In addition, valid measures were used in most studies (Table 1 ). Most studies did not examine the differences between genders.

Child labor and physical health

Fifteen studies examined physical health effects of child labor, including nutritional status, physical growth, work-related illnesses/symptoms, musculoskeletal pain, HIV infection, systematic symptoms, infectious diseases, tuberculosis and eyestrain. Eight studies measured physical health effects through clinical examination or blood samples, in addition to self-reported questionnaires. All studies in which a comparison group was used reported higher prevalence of physical diseases in the working children group.

Two studies were concerned with physical growth and development. A study conducted in Pakistan, 11 reported that child labor is associated with wasting, stunting and chronic malnutrition. A similar study conducted in India compared physical growth and genital development between working and non-working children and reported that child labor is associated with lower BMI, shorter stature and delayed genital development in working boys, while no significant differences were found among females. 12

Concerning work-related illnesses and injuries, a study conducted in Bangladesh reported that there is a statistically significant positive association between child labor and the probability to report any injury or illness, tiredness/exhaustion, body injury and other health problems. Number of hours worked and the probability of reporting injury and illness were positively correlated. Younger children were more likely to suffer from backaches and other health problems (infection, burns and lung diseases), while probability of reporting tiredness/exhaustion was greater in the oldest age group. Furthermore, the frequency of reporting any injury or illness increases with the number of hours worked, with significant variation across employment sectors. 13 A study in Iran reported that industrial workrooms were the most common place for injury (58.2%). Falling from heights or in horizontal surface was the most common mechanism of injury (44%). None of the patients was using a preventive device at the time of injury. Cuts (49.6%) were the most commonly reported injuries. 14

Other studies that investigated the prevalence of general symptoms in working children in Pakistan, Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan and Indonesia reported that child labor is negatively associated with health. 15 – 19 Watery eyes, chronic cough and diarrhea were common findings, in addition to history of a major injury (permanent loss of an organ, hearing loss, bone fractures, permanent disability). 20 One study, conducted in India reported that working children suffered from anemia, gastrointestinal tract infections, vitamin deficiencies, respiratory tract infections, skin diseases and high prevalence of malnutrition. 21 Another study—of poor quality—in India reported that child labor was associated with higher incidence of infectious diseases compared to non-working children. 22

Only a few studies focused on specific diseases. A study in Brazil compared the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain between working and non-working children. Authors reported that the prevalence of pain in the neck, knee, wrist or hands, and upper back exceeded 15%. Workers in manufacturing had a significantly increased risk for musculoskeletal pain and back pain, while child workers in domestic services had 17% more musculoskeletal pain and 23% more back pain than non-workers. Awkward posture and heavy physical work were associated with musculoskeletal pain, while monotonous work, awkward posture and noise were associated with back pain. 23 A study in Nicaragua, which focused on children working in agriculture, reported that child labor in agriculture poses a serious threat to children’s health; specifically, acute pesticides poisoning. 24

A study conducted in India reported that the prevalence of eyestrain in child laborers was 25.9%, which was significantly more than the 12.4% prevalence in a comparison group. Prevalence was higher in boys and those who work more than 4 h daily. 25 Another study conducted in India documented that the difference between working and non-working children in the same area in respiratory morbidities (TB, hilar gland enlargement/calcification) was statistically significant. 26

A study in Iran explored the prevalence of viral infections (HIV, HCV and HBV) in working children. 27 The study reported that the prevalence among working street children was much higher than in general population. The 4.5% of children were HIV positive, 1.7% were hepatitis B positive and 2.6% hepatitis C positive. The likelihood of being HIV positive among working children of Tehran was increased by factors like having experience in trading sex, having parents who used drugs or parents infected with HCV.

Lastly, one study was a meta-analysis conducted on data of working children in 83 LMIC documented that child labor is significantly and positively related to adolescent mortality, to a population’s nutrition level, and to the presence of infectious diseases. 8

Child labor and mental health

Overall, all studies included, except one, 28 reported that child labor is associated with higher prevalence of mental and/or behavioral disorders. In addition, all studies concluded that child labor is associated with one or more forms of abuse.

A study conducted in Jordan reported a significant difference in the level of coping efficacy and psychosocial health between working non-schooled children, working school children and non-working school children. Non-working school children had a better performance on the SDQ scale. Coping efficacy of working non-schooled children was lower than that of the other groups. 29

A study conducted in Pakistan reported that the prevalence of behavioral problems among working children was 9.8%. Peer problems were most prevalent, followed by problems of conduct. 30 A study from Ethiopia 31 reported that emotional and behavioral disorders are more common among working children. However, another study in Ethiopia 28 reported a lower prevalence of mental/behavioral disorders in child laborers compared to non-working children. The stark difference between these two studies could be due to the explanation provided by Alem et al. , i.e. that their findings could have been tampered by selection bias or healthy worker effect.

A study concerned with child abuse in Bangladesh reported that the prevalence of abuse and child exploitation was widespread. Boys were more exposed. Physical assault was higher towards younger children while other types were higher towards older ones. 32 A similar study conducted in Turkey documented that 62.5% of the child laborers were subjected to abuse at their workplaces; 21.8% physical, 53.6% emotional and 25.2% sexual, 100% were subjected to physical neglect and 28.7% were subjected to emotional neglect. 33

One study focused on sexual assault among working females in Nigeria. They reported that the sexual assault rate was 77.7%. In 38.6% of assault cases, the assailant was a customer. Girls who were younger than 12 years, had no formal education, worked for more than 8 h/day, or had two or more jobs were more likely to experience sexual assault. 34

Main findings of this study

Through a comprehensive systematic review, we conclude that child labor continues to be a major public health challenge. Child labor continues to be negatively associated with the physical and psychological health of children involved. Although no cause–effect relation can be established, as all studies included are cross-sectional, studies documented higher prevalence of different health issues in working children compared to control groups or general population.

This reflects a failure of policies not only to eliminate child labor, but also to make it safer. Although there is a decline in the number of working children, the quality of life of those still engaged in child labor seems to remain low.

Children engaged in labor have poor health status, which could be precipitated or aggravated by labor. Malnutrition and poor growth were reported to be highly prevalent among working children. On top of malnutrition, the nature of labor has its effects on child’s health. Most of the studies adjusted for the daily working hours. Long working hours have been associated with poorer physical outcomes. 18 , 19 , 25 , 26 , 35 It was also reported that the likelihood of being sexually abused increased with increasing working hours. 34 The different types and sectors of labor were found to be associated with different health outcomes as well. 13 , 18 , 24 However, comparing between the different types of labor was not possible due to lack of data.

The majority of studies concluded that child labor is associated with higher prevalence of mental and behavioral disorders, as shown in the results. School attendance, family income and status, daily working hours and likelihood of abuse, in its different forms, were found to be associated with the mental health outcomes in working children. These findings are consistent with previous studies and research frameworks. 36

Child labor subjects children to abuse, whether verbally, physically or sexually which ultimately results in psychological disturbances and behavioral disorders. Moreover, peers and colleagues at work can affect the behavior of children, for example, smoking or drugs. The effects of child labor on psychological health can be long lasting and devastating to the future of children involved.

What is already known on this topic

Previous reviews have described different adverse health impacts of child labor. However, there were no previous attempts to review the collective health impacts of child labor. Working children are subjected to different risk factors, and the impacts of child labor are usually not limited to one illness. Initial evidence of these impacts was published in the 1920s. Since then, an increasing number of studies have used similar methods to assess the health impacts of child labor. Additionally, most of the studies are confined to a single country.

What this study adds

To our knowledge, this is the first review that provides a comprehensive summary of both the physical and mental health impacts of child labor. Working children are subjected to higher levels of physical and mental stress compared to non-working children and adults performing the same type of work. Unfortunately, the results show that these children are at risk of developing short and long-term health complications, physically or mentally.

Though previous systematic reviews conducted on the topic in 19 97 1 and 20 07 8 reported outcomes in different measures, our findings reflect similar severity of the health impacts of child labor. This should be alarming to organizations that set child labor as a target. We have not reviewed the policies targeting child labor here, yet our findings show that regardless of policies in place, further action is needed.

Most of the current literature about child labor follow a cross-sectional design, which although can reflect the health status of working children, it cannot establish cause–effect associations. This in turn affects strategies and policies that target child labor.

In addition, comparing the impacts of different labor types in different countries will provide useful information on how to proceed. Further research following a common approach in assessing child labor impacts in different countries is needed.

Limitations of this study

First, we acknowledge that all systematic reviews are subject to publication bias. Moreover, the databases used might introduce bias as most of the studies indexed by them are from industrialized countries. However, these databases were used for their known quality and to allow reproduction of the data. Finally, despite our recognition of the added value of meta-analytic methods, it was not possible to conduct one due to lack of a common definition for child labor, differences in inclusion and exclusion criteria, different measurements and different outcome measures. Nevertheless, to minimize bias, we employed rigorous search methods including an extensive and comprehensive search, and data extraction by two independent reviewers.

Compliance with ethical standards

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Parker DL . Child labor. The impact of economic exploitation on the health and welfare of children . Minn Med 1997 ; 80 : 10 – 2 .

Google Scholar

Hilowitz J . Child Labour: A Textbook for University Students . International Labour Office , 2004 .

Google Preview

Humphries J . Childhood and child labour in the British industrial revolution . Econ Hist Rev 2013 ; 66 ( 2 ): 395 – 418 .

Dahlén M . The negotiable child: the ILO child labour campaign 1919–1973. Diss . 2007 .

Sachs JD , McArthur JW . The millennium project: a plan for meeting the millennium development goals . Lancet 2005 ; 365 ( 9456 ): 347 – 53 .

Griggs D et al. Policy: sustainable development goals for people and planet . Nature 2013 ; 495 ( 7441 ): 305 – 7 .

UNICEF . The state of the world’s children 2016: a fair chance for every child. Technical Report, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2016 .

Roggero P , Mangiaterra V , Bustreo F et al. The health impact of child labor in developing countries: evidence from cross-country data . Am J Public Health 2007 ; 97 ( 2 ): 271 – 5 .

Hughes K , Bellis MA , Hardcastle KA et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Lancet Public Health 2017 ; 2 ( 8 ): e356 – 66 .

Downs SH , Black N . The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions . J Epidemiol Community Health 1998 ; 52 ( 6 ): 377 – 84 .

Ali M , Shahab S , Ushijima H et al. Street children in Pakistan: a situational analysis of social conditions and nutritional status . Soc Sci Med 2004 ; 59 ( 8 ): 1707 – 17 .

Ambadekar NN , Wahab SN , Zodpey SP et al. Effect of child labour on growth of children . Public Health 1999 ; 113 ( 6 ): 303 – 6 .

Ahmed S , Ray R . Health consequences of child labour in Bangladesh . Demogr Res 2014 ; 30 : 111 – 50 .

Hosseinpour M , Mohammadzadeh M , Atoofi M . Work-related injuries with child labor in Iran . Eur J Pediatr Surg 2014 ; 24 ( 01 ): 117 – 20 .

Mohammed ES , Ewis AA , Mahfouz EM . Child labor in a rural Egyptian community: an epidemiological study . Int J Public Health 2014 ; 59 ( 4 ): 637 – 44 .

Nuwayhid IA , Usta J , Makarem M et al. Health of children working in small urban industrial shops . Occup Environ Med 2005 ; 62 ( 2 ): 86 – 94 .

Wolff FC . Evidence on the impact of child labor on child health in Indonesia, 1993–2000 . Econ Hum Biol 2008 ; 6 ( 1 ): 143 – 69 .

Hamdan-Mansour AM , Al-Gamal E , Sultan MK et al. Health status of working children in Jordan: comparison between working and nonworking children at schools and industrial sites . Open J Nurs 2013 ; 3 ( 01 ): 55 .

Tiwari RR , Saha A . Morbidity profile of child labor at gem polishing units of Jaipur, India . Int J Occup Environ Med 2014 ; 5 ( 3 ): 125 – 9 .

Khan H , Hameed A , Afridi AK . Study on child labour in automobile workshops of Peshawar, Pakistan, 2007 .

Banerjee SR , Bharati P , Vasulu TS et al. Whole time domestic child labor in metropolitan city of Kolkata, 2008 .

Daga AS , Working IN . Relative risk and prevalence of illness related to child labor in a rural block . Indian Pediatr 2000 ; 37 ( 12 ): 1359 – 60 .

Fassa AG , Facchini LA , Dall’Agnol MM et al. Child labor and musculoskeletal disorders: the Pelotas (Brazil) epidemiological survey . Public Health Rep 2005 ; 120 ( 6 ): 665 – 73 .

Corriols M , Aragón A . Child labor and acute pesticide poisoning in Nicaragua: failure to comply with children’s rights . Int J Occup Environ Health 2010 ; 16 ( 2 ): 175 – 82 .

Tiwari RR . Eyestrain in working children of footwear making units of Agra, India . Indian Pediatr 2013 ; 50 ( 4 ): 411 – 3 .

Tiwari RR , Saha A , Parikh JR . Respiratory morbidities among working children of gem polishing industries, India . Toxicol Ind Health 2009 ; 25 ( 1 ): 81 – 4 .

Foroughi M , Moayedi-Nia S , Shoghli A et al. Prevalence of HIV, HBV and HCV among street and labour children in Tehran, Iran . Sex Transm Infect 2016 ; 93 ( 6 ): 421 – 23 .

Alem AA , Zergaw A , Kebede D et al. Child labor and childhood behavioral and mental health problems in Ethiopia . Ethiopian J Health Dev 2006 ; 20 ( 2 ): 119 – 26 .

Al-Gamal E , Hamdan-Mansour AM , Matrouk R et al. The psychosocial impact of child labour in Jordan: a national study . Int J Psychol 2013 ; 48 ( 6 ): 1156 – 64 .

Bandeali S , Jawad A , Azmatullah A et al. Prevalence of behavioural and psychological problems in working children . J Pak Med Assoc 2008 ; 58 ( 6 ): 345 .

Fekadu D , Alem A , Hägglöf B . The prevalence of mental health problems in Ethiopian child laborers . J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006 Sep 1; 47 ( 9 ): 954 – 9 .

Hadi A . Child abuse among working children in rural Bangladesh: prevalence and determinants . Public Health 2000 ; 114 ( 5 ): 380 – 4 .

Öncü E , Kurt AÖ , Esenay FI et al. Abuse of working children and influencing factors, Turkey . Child Abuse Negl 2013 ; 37 ( 5 ): 283 – 91 .

Audu B , Geidam A , Jarma H . Child labor and sexual assault among girls in Maiduguri, Nigeria . Int J Gynecol Obstet 2009 Jan 31; 104 ( 1 ): 64 – 7 .

Gross R , Landfried B , Herman S . Height and weight as a reflection of the nutritional situation of school-aged children working and living in the streets of Jakarta . Soc Sci Med 1996 Aug 1; 43 ( 4 ): 453 – 8 .

Woodhead M . Psychosocial impacts of child work: a framework for research, monitoring and intervention . Int J Child Rts 2004 ; 12 : 321 .

- developing countries

- mental health

- child labor

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1741-3850

- Print ISSN 1741-3842

- Copyright © 2024 Faculty of Public Health

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Working Children and Child Labor Situation

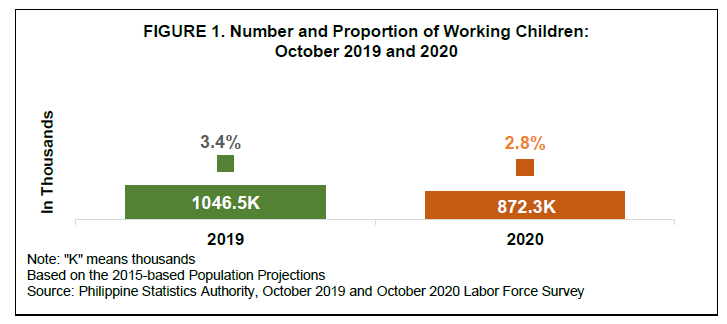

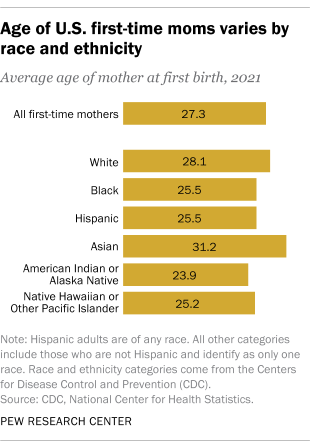

Proportion of working children 5 to 17 years old was estimated at 2.8 percent.

The total population of children 5 to 17 years old was estimated at 31.17 million in 2020. This was higher than the total number of Filipino children 5 to 17 years of age registered in 2019 at 30.50 million.

Of the estimated 31.17 million children 5 to 17 years old in 2020, 872 thousand or 2.8 percent were working. This was lower than the proportion of working children 5 to 17 years old in 2019 estimated at 3.4 percent. (Figure 1 and Table A)

Working children was higher among boys compared to the girls. Of the 872 thousand working children in 2020, 582 thousand or 66.7 percent were boys while 291 thousand or 33.3 percent were girls. In 2019, 65.6 percent of the working children were boys while 34.4 percent were girls.

Children belonging to the older age groups (15 to 17 years) were more likely to work than the younger ones. Majority of the working children belonged to age group 15 to 17 years of age accounting for 68.9 percent of the total working children in 2020 and 67.4 percent in 2019. (Table B)

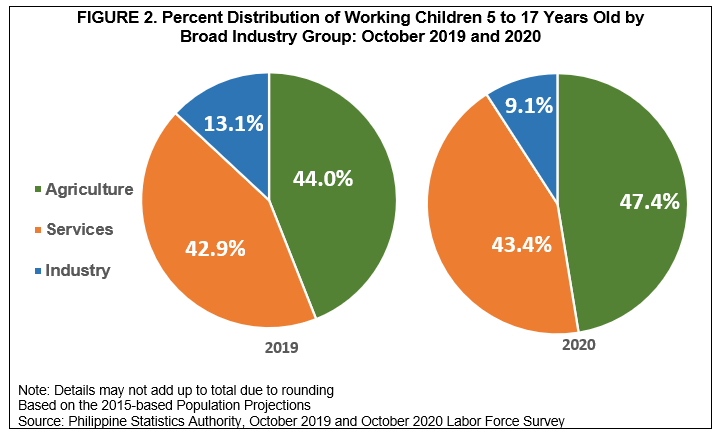

Majority of working children were in agriculture sector

By broad industry group, agriculture sector registered the highest proportion of working children in 2020 at 47.4 percent. The same sector had working children accounted for 44.0 percent of the total working children in 2019. In addition, working children in the services sector was the second largest group accounted for 43.4 percent of the total working children in 2020. Working children in the industry sector consistently accounted for the smallest contributing sector at 9.1 percent. (Figure 2 and Table B)

Majority of the working children worked 20 hours or less per week

Working children were asked on the actual number of hours worked during the reference week. Of the total working children, majority (53.0%) reported to have worked 20 hours or less per week in 2020. This was lower than the proportion of children who worked 20 hours or less per week in 2019 at 69.6 percent. Meanwhile, children who worked for 21 to 40 hours increased to 26.7 percent in 2020 from the 14.8 percent in 2019. (Table B)

Working Children was highest in the Northern Mindanao

Across the regions, CALABARZON with about 4.22 million, National Capital Region (NCR) with nearly 3.35 million, and Central Luzon with around 3.26 million had the largest population of children 5 to 17 years old in 2020. In terms of proportion of working children, Northern Mindanao posted the highest at 7.2 percent in 2020 and 10.0 percent in 2019. (Table A)

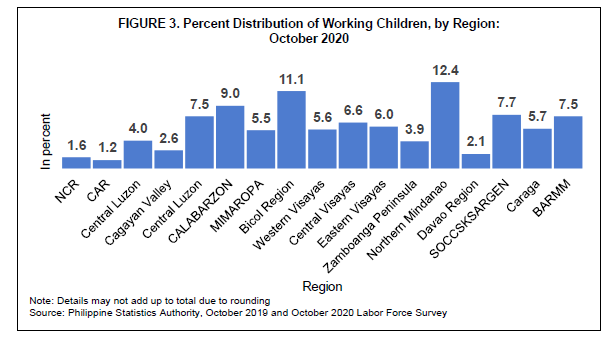

In terms of the share of the working children, for every 100 working children in the country in 2020, around 12 (12.4%) resided in Northern Mindanao, 11 (11.1%) resided in Bicol Region, and 9 resided in CALABARZON. On the other hand, Cordillera Autonomous Region (1.2%), NCR (1.6%), Davao Region (2.1%), and Cagayan Valley (2.6%) each had less than 3 working children for every 100 working children in the country. (Figure 3 and Table B)

Child laborers in the country continued to drop in 2020

Child labor referred to in this report were those children 5 to 17 years of age engaged in hazardous work identified in the DOLE Administrative Order No. 149 or long working hours only.

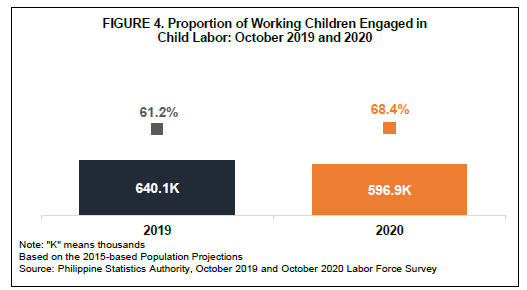

The total number of working children considered engaged in child labor was estimated at 597 thousand in 2020. This magnitude of working children considered engaged in child labor was lower than the 640 thousand child laborers in 2019. (Table C)

In terms of proportion, 68.4 percent of the working children were engaged in child labor in 2020. This was higher than the estimate of 61.2 percent in 2019. (Figure 4 and Table C)

Of the estimated 597 thousand working children engaged in child labor in 2020, 435 thousand or 72.8 percent of them were boys while 162 thousand or 27.2 percent were girls. (Figure 5 and Table D)

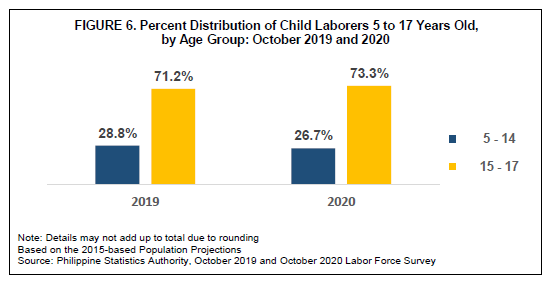

Across age groups, the largest proportion of working children considered engaged in child labor were in the ages 15 to 17 years at 73.3 percent in 2020. In the same manner, child laborers aged 15 to 17 years old comprised the largest share in 2019 at 71.2 percent. (Figure 6 and Table D)

Classified by broad industry group in 2020, about 63.6 percent of child laborers were in the agriculture sector, 28.6 percent were in the services sector, and 7.9 percent were in the industry sector. (Figure 7 and Table D)

Thirteen in every 100 child laborers were in Northern Mindanao

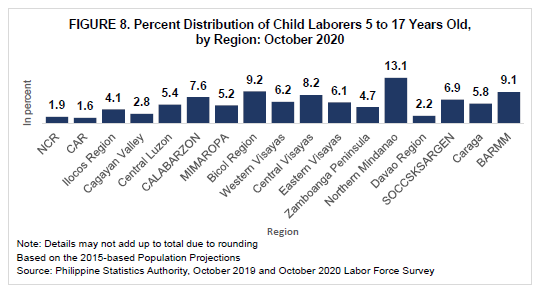

Among the 17 regions, Northern Mindanao had the largest share of the country’s child laborers. For every 100 child laborers in the country in 2020, 13 (13.1%) were from Northern Mindanao, followed by Bicol Region with around 9 (9.2%) child laborers. Cordillera Administrative Region had the lowest share of child laborers at 1.6 percent followed by NCR at 1.9 percent and Davao Region at 2.2 percent in 2020. (Figure 8 and Table D)

The population of children aged 5 to 17 years old in 2020 was estimated at 31.17 million. This was higher than the total number of Filipino children 5 to 17 years of age in 2019 at 30.50 million.

Working children in 2020 were estimated at 2.8 percent of the 31.17 million children 5 to 17 years old. This was lower than the registered working children in 2019 at 3.4 percent.

In terms of the distribution of working children by broad industry group, agriculture sector remained dominant in 2020, followed by services sector, while industry sector remained the lowest contributor to the total working children.

Of the 872 thousand working children in 2020, 597 thousand or 68.4 percent were child laborers. Of these estimated child laborers, 73.3 percent were in age group 15 to 17 years. Moreover, 63.6 percent of the 597 thousand child laborers were found in the agriculture sector.

DENNIS S. MAPA, Ph.D. Undersecretary National Statistician and Civil Registrar General

Related Contents

Employment rate in january 2024 was estimated at 95.5 percent, press conference on the january 2024 labor force survey (preliminary) results, unemployment rate in december 2023 was estimated at 3.1 percent.

Child Labor in the Philippines

PHILIPPINES – A child miner pulls an improvised cart made from a gasoline container carrying heavy rocks. Child laborers in mines are at risk of severe injury and death, and face long-term health problems caused by back-breaking labor, constant exposure to dust and chemicals, and most of all mercury poisoning.

Child labor persists side by side with chronic poverty in the Philippines. While programs to address child labor by the government, international agencies and civil society groups are in place, child labor is still worsening. Based on the latest official count as of 2011, there are 3.2 million child laborers who are mostly in hazardous work, out of the 5.5 million children at work.[1]

The problem of child labor lies deeply in the structural problems of the society, heavily connected to deeply rooted poverty and continuous non-inclusive growth in the economy. Other push factors of child labor include land-grabbing, low family income, lack of regular and decent jobs with living wages for parents, and low awareness on rights of children among poor families. This is aggravated as businesses and companies continue to exploit child laborers through lower wages, lack of benefits and protection, and weak government mechanisms and instruments to combat the employment of children. Child laborers are forced to leave their formal education and focus on their work, leaving them more vulnerable to abuses, violations and little chance and opportunity to have a better future.

BUKIDNON – People in Don Carlos, Bukidnon depend mainly on agriculture and plantation work. Child laborers in sugarcane estates work in weeding, harvesting and fetching of water.

The number of children working in hazardous industries stands at 2.99 million (2011), an increase from 2.2 million in 1995. Child labor is prevalent in rural areas, particularly in mining sites and in agricultural plantations (sugarcane, banana, palm oil). A study conducted by EILER indicates that child labor in the country has worsened as reflected in:

Longer working hours of children, multiple jobs juggled by child laborers, and exposure to social hazards (such as use of illegal drugs) and occupational health and safety hazards.

One out of five households surveyed for the study showed incidence of child labor.

High tendency for child laborers to stop schooling. Child laborers normally work for an average of ten hours daily for a tiny fraction of the prevailing minimum wage and extreme cases of 24-hour shift in mining, even as the magnitude of their work is comparable to those of adults.

Ninety-six percent (96%) of households surveyed were living below the poverty thresholds of their region and have an average monthly family income of P1,000 – P3,000 (highest incidence of child labor at 40%).

Seventy-seven percent (77%) of households surveyed do not own land and has no accessibility to land.

The children and their families have no means to escape the vicious cycle of generational poverty as child laborers work the same kind of low-income, labor-intensive jobs and generate just enough income to eat and work the next day. Unable to finish basic education, they are unable to apply to stable work which demands technical skills they do not have.

Children working in hazardous industries are exposed to the dangers and perils of heavy physical work, exposure to chemicals and unsafe working conditions. At their tender age, these children are deprived of their right to education, right against economic exploitation and right to have everything they need to have a better future.

DAVAO DEL NORTE – Child laborers in banana plantations often serve as fruiters, harvesters, haulers, loaders, and uprooters. Over time, the children have sustained injuries from weeding, harvesting, bagging and de-leafing work.

End poverty. End child labor.

November 20, 2014 marked the 25th year since the U.N. General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Rights of Child (CRC). Throughout the years, there have been significant achievements on upholding the rights of children worldwide, but much has to be done to address the root causes of child labour and build actions to end its worst forms.

The Ecumenical Institute for Labor Education and Research (EILER) with support from the European Union under the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR) implemented “Bata Balik-Eskwela: Community-based Approach in Combating Child Labor in Hazardous Industries in Mining and Plantations” from 2013 to 2016 to help curb child labor in Caraga Region, Bukidnon, Camarines Norte, Davao Del Norte, Compostela Valley and Negros Occidental through education and building community-based support network for child laborers and their families.

Read Bittersweet: Combatting Child Labour on the Sugarcane Plantations in the Philippines from the European Commission website.

Watch “Dula-anan” (2016) video documentary on the campaign to end child labor and the Bata Balik-Eskwela Program.

COMPOSTELA VALLEY – Beneficiaries of Bata Balik-Eskwela Program in Southeastern region of the Philippines start their graduation ceremony at the open court of their rural community (on top of Mt. Diwalwal) with a prayer.

The project aimed to reintegrate child laborers to formal education through the establishment of Learning Centers, creation of a community-based support system and advocating children’s rights. It had three (3) components namely Bata Balik-Eskwela Program (BBEP), Community-based Support Network Program (CBSP) and Public Awareness and Advocacy Program (PAAP).

Through the project and in cooperation with the Center for Trade Union and Human Rights , Institute for Occupational Health and Safety Development , Rural Missionaries of the Philippines Northern Mindanao Sub-region , and community organizations, six (6) Learning Centers were established to provide appropriate curriculum and school materials to the beneficiaries. At the end of the project, a total of 618 children enrolled in five (5) batches at each learning center and 518 of them completed the program.

[1] 2011 Survey on Children, National Statistics Office. http://web0.psa.gov.ph/content/number-working-children-5-17-years-old-estimated-55-million-preliminary-results-2011-survey

Our Story & Mission

Our Strategy

Annual Reports & Finances

Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

Code of Conduct & Policies

Legal Disclosures

Explore Research

Public Data

Evidence Generation

Sectoral Expertise

Agriculture

Consumer Protection

Entrepreneurship & Private Sector Development

Financial Inclusion

Health & Nutrition

Human Trafficking

Intimate Partner Violence

Peace & Recovery

Social Protection

Research Funding

Open Opportunities

Closed Opportunities

Rigorous Research

High-Quality Data

Ethics & IPA IRB

Research Methods

Research Support

Evidence Use

COVID-19 Response

Embedded Evidence Labs

Policy Influence

Scaling What Works

Advisory Services

Poverty Measurement

Right-Fit Evidence

IPA has 20 country offices, listed here, as well as projects in 30+ more countries across the globe.

View Full Map

East Africa

West Africa

Burkina Faso

Côte d’Ivoire

Sierra Leone

Philippines

Latin America & the Caribbean

Dominican Republic

Equipping Decision-Makers

Influencing Policy & Programming

What Do We Mean by Impact?

Theory of Action

For Practitioners

For Policymakers

For Researchers

See funding opportunities»

The Impact of Productive Assets and Training on Child Labor in the Philippines

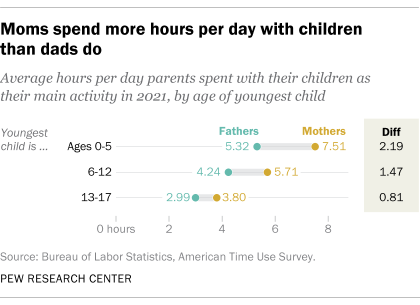

Around the world, 152 million children are engaged in child labor, and in the Philippines many of the children working illegally are in occupations that pose a threat to their health and safety. Because poverty is considered to be the root cause of child labor, policymakers have aimed to reduce child labor by improving the economic welfare of poor households that are using or vulnerable to using child labor. In the Philippines, an IPA research team worked with the government to test whether providing poor households with a one-time productive asset transfer equivalent to US$518, along with a short business training, improved economic well-being and reduced in child labor. Preliminary results indicate that the program increased household business activity, food security, and some measures of child welfare, but it also led to a modest increase in child labor from family-based economic activities, specifically for children who had not worked before.

Policy Issue

The elimination of child labor in all its forms is one of the measurable targets for the UN Sustainable Development Goal 8: “Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all.” Widespread child labor in low-income countries is thought to damper future economic growth through its negative impact on child development. Child labor also depresses economic growth by discouraging the adoption of skill-intensive technologies, while lowering wages in low-skill sectors. Because poverty is considered the root cause of child labor, policymakers have aimed to reduce child labor by improving the economic welfare of poor households. This study aimed to shed light on whether sustainable livelihoods promotion can stop child labor where it already exists, which many other interventions have failed to do, and prevent it from occurring in households that are vulnerable to using child labor.

Context of the Evaluation

Despite strong economic progress over the last several decades, one in five Filipino families remain below the poverty line, and a 2011 study found 2.1 million Filipino children were engaged in unlawful child labor. Sixty-two percent worked in hazardous labor activities where chemical, physical, and biological hazards exist. 1

The Philippine government is a global leader in the discussion of anti-child labor policies through the Philippine Department of Labor and Employment’s (DOLE) Kabuhayan Para sa Magulang ng Batang Manggagawa (KASAMA) Program. This program provides in-kind transfers of equipment, tools, and/or raw materials and trainings to parents of child laborers in an effort to promote sustainable, alternative forms of income that replace the family’s use of child labor.

This study was conducted in five regions of the Philippine island of Luzon. Two of these regions, Bicol and Central Luzon, account for more than 1 in 5 of all child laborers in the Philippines. 2 Among the families in the study, 73 percent of children living in treated households were child laborers, and these families lived on less than $1.30 per person per day on average.

Details of the Intervention

Innovations for Poverty Action worked with researchers to test the impact of the KASAMA program on child labor, economic activity, household income, and consumption.

The program offered households a productive asset along with a short business training and was designed to support families in moving to more entrepreneurial activities and sustainable livelihoods. Potential beneficiaries were drawn from existing government lists of vulnerable families with children and families with child laborers.

One-hundred and sixty-four communities (barangays) across five regions of Luzon were randomly assigned to one of two groups:

- Program group: Households in 82 communities could access an asset such as livestock, farming tools, inventory for vending snacks, or materials for producing home goods (such as candles or curtains) worth PHP10,000 (USD$518 Purchasing Power Parity). The program also included three one-day trainings designed to provide assistance on developing a business plan, bookkeeping, marketing and financial literacy. The training also included a brief orientation on child labor: how it is defined legally in the Philippines and how the government is engaging communities to reduce child labor. Households were not told the program was designed to reduce child labor, however. (1,148 households)

- Comparison group: This group was comprised of 82 communities who did not receive the intervention. (1,148 households)

Researchers measured impacts of the program approximately 18 months after it started.

Results and Policy Lessons

Overall, households offered the program had better food security and improvements in some measures of child welfare (e.g., life satisfaction), but it also led to a modest increase in the number of children who worked. The increase in child labor appears to be driven by the increase in work opportunities brought on by the family businesses.

Livelihoods : Households assigned to receive the program were more likely to start new businesses and preserve existing businesses.

- Households offered the program were 9 percentage points more likely to report the presence of either an agricultural or non-agricultural family firm, an 11 percent increase over comparison households.

- These households reported 0.26 new non-farm enterprises over the study period (a 61 percent increase over the comparison group). Overall, households offered the program have 0.36 more non-farm enterprises at follow-up compared to the comparison group. Because this 0.36 is bigger than the number of new non-farm enterprises, we can infer that the program helped some existing enterprises survive.

- The most common assets transferred were for the creation or expansion of small convenience stores (“sari-sari ” stores ) .

- Flexibility in asset choice appeared important to beneficiaries according to qualitative interviews with frequent reports of experimentation in different enterprises to find what worked best for the household and some suggestion that the best asset for one household was not necessarily the best asset for another household, even in the same community.

Economic well-being: Household food security improves:

- Adults and children less than age 14 report not having to cut meals, being able to eat preferred food options, and not needing to borrow food or purchase food on credit.

Child labor: There was no overall effect on primary or secondary measures of child labor.

- For children not involved in child labor at baseline, employment in family based economic activities increases by 10 percentage points, a 16 percent increase over the comparison group. Economic activity rates increased for this group overall by 8.4 percentage points or 13 percent.

- For children already involved in child labor at baseline, the program seemed to have little effect on their time allocation.

- There is no evidence to suggest that increasing the value of the productive asset transfer would change the child labor findings, although that could be subject to further study.

Child welfare: Child welfare increased on average. 3 This appears to be driven largely by changes in life satisfaction and is concentrated among children already in child labor before the program started. These improvements in welfare for children who were laborers before the program began seems to again be due to improvements in life satisfaction. Children were more likely to report that they were thriving and had higher scores on the Student’s Life Satisfaction Survey. For children not in child labor before the program, the main outcome in which they show improvements in welfare is that they were less likely to report they were suffering. It is worth noting that children in homes that already had businesses before the program was offered did not experience these gains in child welfare and life satisfaction, which could be due to the increase in work in this group.

Policy Lessons

Overall, these findings raise questions about the value of providing a productive asset transfer to families in order to reduce child labor. Yet they also highlight the value of KASAMA in ameliorating poverty, increasing food security, and improving very poor children’s life satisfaction.

This highlights one of the important––and previously unknown–– tensions in using a sustainable livelihood program to combat child labor. Families with child labor present are amongst the poorest and most disadvantaged, and livelihood support can make them less impoverished (as KASAMA has done). However, when introducing a new enterprise into a household, available laborers are needed to work in the new enterprise. In this context, there was not a large surplus of prime-age adult labor. Poor families were working hard to make ends meet, so the addition of a new economic activity or expanding an existing activity brought in more marginal workers, which were often children and the aged (unreported above, elder women increased their economic activity by 48 percent from being offered the program). Thus, it is critical to be clear on the goals of a sustainable livelihood program. If the goal is to improve the lives of families with child labor, then KASAMA was an impressive success. However, if the goal was to eliminate child labor in beneficiary families, then the program was not successful in reaching that goal and other approaches should be considered and tested.

Funding for this project was provided by the United States Department of Labor.

This material does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Department of Labor, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government.

[1] “Philippines - 2011 Survey on Children 5 to 17 Years Old - Final Report,” Report, February 1, 2014. p. 8 http://www.ilo.org/ipec/Informationresources/WCMS_IPEC_PUB_26815/lang--en/index.htm.

[2] “Philippines - 2011 Survey on Children 5 to 17 Years Old - Final Report,” p. 56.

[3] The primary life satisfaction metric is Cantril’s (1965) Ladder which researchers collected for each child 10-17 in the household. The respondent provided a scaled response of their life quality ranging between 0 to 10, and researchers examine the impact of KASAMA on the child’s raw score and on indicators consistent with how the Gallop Organization uses Cantril’s Ladder, creating indicators by splitting the responses into thriving (7+) and suffering (4-).

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Child Labour in the Philippines: Determinants and Effects

2000, Asian Economic Journal

Related Papers

Fernando Aldaba , Leonardo Lanzona

Aniceto Orbeta

Philippine Journal of …

Leonardo Lanzona

Cesar C Rufino

This study utilized the recently available public use raw data file of the 2011 round of the Annual Poverty Indicator Survey (APIS) to establish the latest stylized facts on the Philippine child labor situation. Public use file of the 2008 APIS was also used to generate comparative descriptives. It is also an attempt to jointly estimate the schooling and employment choices of Filipino children via the multinomial logistic model that used the four different permutations of schooling and employment as the mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories of choice. A value added feature of the study is the use of survey design consistent procedures in establishing the descriptives as well as the estimates of the main empirical model. Tabulated summaries of the results reveal some alarming developments in the child labor situation of the country. The outcome of the econometric modeling confirms the empirical relevance of certain covariates discussed in the literature concerning schooling/wo...

Ivory Myka Galang

The measured impact on child labor varies among the conditional cash transfer (CCT) programs with observed significant impact on children’s schooling. In the Philippines, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) was regarded by World Bank as one of the best targeted social protection programs in the world. This research investigated whether or not 4Ps has reduced the incidence of child laborers, particularly those aged 12 to 14 years. Using the Annual Poverty Indicator Surveys of 2011, propensity score matching method was implemented to estimate the treatment effects on the treated (ATT). The results indicated positive and significant impact on schooling outcomes, which ranged from 5.7 to 7.5 percentage points. The 4Ps helped in narrowing the gap between male and female in terms of school attendance. Moreover, greater impact was observed among older children. However, despite the significant school attendance increase caused by the program, the results showed no significant imp...

Dlsu Business & Economics Review

This study utilized the recently available public use raw data file of the 2011 round of the Annual Poverty Indicator Survey (APIS) to establish the latest stylized facts on the Philippine child labor situation. Public use file of the 2008 APIS was also used to generate comparative descriptives. It is also an attempt to jointly estimate the schooling and employment choices of Filipino children via the multinomial logit model that used the four different permutations of schooling and employment as the mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories of choice. A value added feature of the study is the use of survey design consistent procedures in establishing the descriptives as well as the estimates of the main empirical model. Tabulated summaries of the results reveal some alarming developments in the child labor situation of the country. The outcome of the econometric modeling confirms the empirical relevance of certain covariates discussed in the literature concerning schooling/work ...

This study uses the recently available public use raw data file of the 2011 round of the Annual Poverty Indicator Survey (APIS) to establish the latest stylized facts on the Philippine child labor situation. It is also an attempt to jointly estimate the schooling and employment choices of the Filipino child via the multinomial logistic model that used the four different permutations of schooling and employment as the mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories of choice. A value added feature of the study is the use of survey design consistent procedures in establishing the descriptives as well as the estimates of the main empirical model. Tabulated summaries of the results reveal some alarming developments in the child labor situation of the country. The outcome of the econometric modeling confirms the empirical relevance certain covariates discussed in the literature concerning schooling/work choice formation of children.

BULLETIN OF GEOGRAPHY. SOCIO–ECONOMIC SERIES

BAYU KHARISMA

The existence of child labor is a complex phenomenon and is often considered a logical consequence, in a household, of the economic needs of poverty-stricken families. This is due to several factors such as the condition of the child himself, the family background, and the influences of parents, culture and environment. This paper aims to determine the effect of household structure on child labor by comparing households headed by divorced single mothers and nuclear households that include a mother and father in Indonesia. This study uses cross-sectional data from the 2014 Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS) with the instrumental variable (IV) method. The results showed that, for the nuclear households that include a mother and father, the probability of child labor decreased, or that when a divorced single mother heads the household, the likelihood of child labor increases, including in rural areas. The same thing happens when households headed by divorced single mothers tend to increase the likelihood of sons being sent into the labor market. Thus, household structure has a vital role in determining the decisions of parents to engage their children in paid employment.

Annals of biomedical engineering

Pankaj Pankaj

Trabecular bone is a cellular composite material comprising primarily of mineral and organic phases with their content ratio known to change with age. Therefore, the contribution of bone constituents on bone's mechanical behaviour, in tension and compression, at varying load levels and with changing porosity (which increases with age) is of great interest, but remains unknown. We investigated the mechanical response of demineralised bone by subjecting a set of bone samples to fully reversed cyclic tension-compression loads with varying magnitudes. We show that the tension to compression response of the organic phase of trabecular bone is asymmetric; it stiffens in tension and undergoes stiffness reduction in compression. Our results indicate that demineralised trabecular bone struts experience inelastic buckling under compression which causes irreversible damage, while irreversible strains due to microcracking are less visible in tension. We also identified that the values of th...

Journal of the American College of Cardiology

Sanjiv Sharma

RELATED PAPERS

Acta chirurgica Iugoslavica

goran devedzic

e-Journal of Surface Science and Nanotechnology

Early Childhood Education

Colette Murphy

Der Urologe

Jörg Hennenlotter

Rudolph Serbet

Aesthetic Plastic Surgery

Carlos Mavioso

Neurosurgery

Paul Nyquist

International journal of scientific research

Sanjeev Raj

Advanced Chemistry Letters

alexandre melo

The Journal of Infectious Diseases

Cristian Apetrei

Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery

Monica Richardson

Elenice Fritzsons

Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research

Nágila M.p.s. Ricardo

Richard Majeski

Urological Science

Quantitative Finance

Gareth Peters

Isij International

Rolf Ljunggren

Ignasi Alemany

AGROMAX - Aries Agro Limited

Journal of Medical Ethics

Anthony Wrigley

Dr. CPA Sammy Kimunguyi

Gladys Mugadza

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government.

Here’s how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Enforcing Trade Commitments

- Strengthening Labor Standards

- Combating Child Labor, Forced Labor, and Human Trafficking

- Technical Assistance

- Monitoring, Evaluation, Research and Learning

- East Asia and Pacific

- Europe and Eurasia

- Middle East and Northern Africa

- South and Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor

- List of Goods Produced By Child Labor or Forced Labor

- List of Products Produced by Forced or Indentured Child Labor

- Supply Chains Research

- Reports and Publications

- Grants and Contracts

- Sweat & Toil app

- Comply Chain

- Better Trade Tool

- ILAB Knowledge Portal

- Responsible Business Conduct and Labor Rights Info Hub

- Organizational Chart

- Laws and Regulations

- News Releases

- Success Stories

- Data and Statistics

- What Are Workers' Rights?

- Mission & Offices

- Careers at ILAB

- ILAB Diversity and Inclusion Statement

Child Labor and Forced Labor Reports

Philippines.

Moderate Advancement

In 2022, the Philippines made moderate advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. The government enacted the Expanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act to hold private sector entities responsible for addressing human trafficking. It also enacted the Anti-Online Sexual Abuse or Exploitation of Children and Anti-Child Sexual Abuse or Exploitation Materials Act, which, among other things, punishes perpetrators of online sexual abuse of children and provides penalties for the production, distribution, possession, and provision of access to child sexual abuse or exploitation materials. In addition, the government launched a plan to improve the quality and delivery of education, address access gaps, and build resilience of learners. However, children in the Philippines are subjected to the worst forms of child labor, including commercial sexual exploitation, sometimes as a result of human trafficking. Children also perform dangerous tasks in agriculture and gold mining. The minimum age for work of 15 is lower than the compulsory education age of 18, making children ages 15 through 17 vulnerable to child labor. Social programs also do not sufficiently support child victims of online sexual exploitation, and enforcement of child labor laws remains a challenge throughout the country due to limited personnel and financial resources.

Table 1 provides key indicators on children’s work and education in the Philippines.

Source for primary completion rate: Data from 2021, published by UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2023. (1) Source for all other data: International Labor Organization's analysis of statistics from Labour Force Survey (LFS), 2021. (2)

Based on a review of available information, Table 2 provides an overview of children’s work by sector and activity.

† Determined by national law or regulation as hazardous and, as such, relevant to Article 3(d) of ILO C. 182. ‡ Child labor understood as the worst forms of child labor per se under Article 3(a)–(c) of ILO C. 182.

Philippine children are victims of online sexual abuse and exploitation of children (OSAEC), in which children perform sex acts at the direction of paying foreigners and local Filipinos for live internet broadcasts that take place in small internet cafes, private homes, or windowless buildings sometimes referred to as “cybersex dens.” (3,12,17,18,21-26) The sector is highly profitable and growing due to increasing internet connectivity, widespread English language literacy, gaps in existing legislation and financial systems, and high international demand. (26) According to the latest available information published in 2021, 20 percent of internet-using children between the ages of 12 and 17 in the Philippines have been subjected to OSAEC. (14,18,25-27) Children from rural communities, primarily girls, are also subjected to trafficking domestically in urban centers and tourist destinations for the purposes of domestic work and commercial sexual exploitation. (4,18,21) Children in disaster-affected areas are targeted for sex trafficking, domestic servitude, and other forms of forced labor. As the Philippines is vulnerable to natural disasters including typhoons, tsunamis, volcanic activity, droughts, and erosion—and models indicate that the frequency and scale of these disasters will escalate in the coming years—an increasing number of children may be exposed to child labor. (26,28,29) In addition, perpetrators of child trafficking use student and intern exchange programs, use fake childcare positions, and take advantage of porous maritime borders to facilitate the exploitation of children. (21)

The recruitment and use of children by non-state armed groups, primarily the New People's Army and Dawla Islamiyah, remains a concern in the country. These children are used in both combat and non-combat roles, including as supply officers, medics, and cooks, and for running errands. (14,30,31) In addition, the Islamic State's affiliated groups reportedly have subjected women and girls to sexual slavery. (21) Despite the new administration's commitment to rehabilitate drug users and address the root causes of drug abuse in the country, lethal clashes between civilians and law enforcement officials continue, which resulted in the death of 14 children during the last 6 months of the reporting period. (14,32) Children are used in drug trafficking as pushers, possessors, employees at "drug dens," and cultivators. (14)

Although the Constitution establishes free, compulsory education through age 18, unofficial school-related fees, such as for school uniforms, are prohibitive for some families. Other barriers to education include substandard infrastructure, which makes traveling and access to schools challenging, especially for children in rural areas, and architectural barriers that pose challenges for children with disabilities. (24)

The Philippines has ratified all key international conventions concerning child labor (Table 3).

The government has established laws and regulations related to child labor (Table 4). However, gaps exist in the Philippines' legal framework to adequately protect children from the worst forms of child labor, including a minimum age for work that is below the compulsory education age.

* Country has no conscription (45) ‡ Age calculated based on available information (46,48)

In 2022, the government enacted the Expanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2022, which imposes requirements and responsibilities on a multitude of private sector entities—including internet intermediaries, tourism enterprises, and financial intermediaries—to address and prevent trafficking in persons, including children. The act also identifies penalties for private sector entities if they are found in violation of the requirements. (14,40) Additionally, the Anti-Online Sexual Abuse or Exploitation of Children and Anti-Child Sexual Abuse or Exploitation Materials Act became law during the reporting period. This act provides additional protection for children against digital sexual abuse and exploitation. (14,43,49,50) As the minimum age for work is lower than the compulsory education age in the Philippines, children may be encouraged to leave school before the completion of compulsory education. (24,33-35,46)

The government has established institutional mechanisms for the enforcement of laws and regulations on child labor (Table 5). However, gaps exist within the authority of enforcement agencies that may hinder adequate enforcement of their child labor laws.

Labor Law Enforcement

In 2022, labor law enforcement agencies in the Philippines took actions to address child labor (Table 6). However, gaps exist within the operations of the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) that may hinder adequate labor law enforcement, including insufficient financial and human resource allocation to the labor law inspectorate.

Research indicates that the Philippines does not have an adequate number of labor inspectors to carry out their mandated duties. (14,66,67) A lack of funding, equipment, and data further prevents the labor inspectorate from conducting inspections in all provinces and in the informal sector. (14) The Bureau of Working Conditions acknowledged that more specialized training on child labor is needed to enhance labor inspectors' ability to readily identify and act on child labor situations. (3,13)

Enforcement of child labor protections for children employed in the informal sector and in small and medium-sized enterprises, particularly in agriculture and fishing, falls to DOLE, which has in the past lacked financial and human resources. (3,9,13,18,24) The Rescue the Child Laborers Quick Action Teams are permitted to conduct unannounced compliance visits to video karaoke bars, massage parlors, saunas and bathhouses, and farms, but they are not authorized to conduct visits to private homes to search for underage child domestic workers. However, there are mechanisms available to barangay (neighborhood level) officials to permit them to investigate domestic work-related complaints. (3,9,13,14,64)

Criminal Law Enforcement

In 2022, criminal law enforcement agencies in the Philippines took actions to address child labor (Table 7). However, gaps exist within the Philippine judicial system that may hinder adequate criminal law enforcement, including inefficiencies in court proceedings, which prevent victims from obtaining justice and restitution.

The Philippine National Police continued to refer children involved in drug trafficking to the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), after which they were placed in either juvenile detention centers or Houses of Hope, which, in practice, closely resemble detention centers. (9,24,68) In 2022, police killed a 17-year old suspect after he allegedly drew a weapon during a buy-bust police operation. (69,70) The Department of Justice claimed that it would review over 6,000 killings committed during drug war-related police operations, but the process has been slow and ineffective, with only 52 cases filed in the courts and only 5 convictions of offending police officers. (64)

During the reporting period, officials from law enforcement, courts, and other parts of the government participated in trainings related to OSAEC and trafficking in persons. (14) Philippine law allows judges to award civil compensation to human trafficking survivors based on damages arising from being trafficked, but survivors rarely receive this restitution since perpetrators often lack sufficient assets to pay. However, in cases for which perpetrators are financially able to pay this penalty, many are able to evade doing so due to ineffective, slow court procedures. (18,28,64) Due to the high volume of cybercrime tips related to child sexual exploitation received by the Office of Cybercrime each month, there is the need for additional law enforcement personnel, funds for operations, and equipment for forensic analysis of digital evidence. (24,28) Slow-moving courts, the need for additional training on handling digital evidence, a lack of understanding regarding application of the legal framework to cases, and too few prosecutors also hindered the effective and timely prosecution of human trafficking crimes. (12,18,22,28) Law enforcement agencies raised concerns about a lack of resources, including staff and a centralized database for tracking illegal recruitment and human trafficking. This lack of resources impedes their ability to act quickly on complaints of child labor, including those involving OSAEC, through conducting investigations and initiating prosecutions. (17,28,64)

The government has established a key mechanism to coordinate its efforts to address child labor (Table 8).

During the reporting period, the Inter-Agency Council Against Trafficking established the National Coordination Center Against OSAEC under the DSWD. The center will develop and implement programs to prevent children from being victimized by online and commercial sexual exploitation, and to provide protective services to and reintegrate into society survivors of the crime. (14,50)

The government has established policies that are consistent with relevant international standards on child labor (Table 9).

† Policy was approved during the reporting period. ‡ The government had other policies that may have addressed child labor issues or had an impact on child labor. (38,92,93)

During the reporting period, the Inter-Agency Council Against Trafficking completed an assessment of the Third National Strategic Action Plan Against Trafficking, which the council utilized to finalize the fourth strategic action plan. (14)

In 2022, the government funded and participated in programs that include the goal of eliminating or preventing child labor (Table 10). However, gaps exist in these social programs, including a lack of adequate services for survivors of OSAEC.

For information about USDOL’s projects to address child labor around the world, visit https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/ilab-project-page-search

† Program is funded by the Government of the Philippines. ‡ The government had other social programs that may have included the goal of eliminating or preventing child labor. (106,107)

The Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) continued to coordinate with DSWD when dealing with children allegedly involved in drug trafficking. From July 2016 to October 2022, Philippine law enforcement arrested 4,679 minors. (4,14) PDEA policy is to turn children over within 8 hours of their arrest to "Houses of Hope" ( Bahay ng Pag-asa ), which are rehabilitation and skills training centers for children in trouble with the law. (4,14,108) Previous reports indicate that although there is an accreditation process for these facilities administered by the federal Juvenile Justice and Welfare Council, only a small number of Houses of Hope have met the qualifications, which allows for corruption, maltreatment of residents, and failure to provide quality rehabilitative services. Research from previous years showed that many Houses of Hope essentially operated as youth detention centers, in which some children were subjected to physical and emotional abuse, deprived of liberty, and forced into overcrowded and unhygienic cells. (24,51,108,109) According to the Juvenile Justice Welfare Council, council employees regularly visited the centers during the reporting period to ensure compliance with set standards. Their reports note inadequate food and clothing, inadequate staffing, limited programs and services, prolonged stays in the center, typhoon damage, and absence of psychologists in the centers. (14)

DSWD works in consultation with parents and community leaders to determine how best to assist children suspected of being involved in the drug trade; however, DSWD does not have programs specifically designed to increase protections for or assistance to children engaged in drug trafficking. DSWD also lacks programming to address the heightened vulnerability of children impacted by the death of familial breadwinners in the drug war. (9,110) In addition, although some specialized resources exist to assist victims of human trafficking, the Philippines lacked sufficient programs to care for and rehabilitate children who have been victims of OSAEC. (25)

Based on the reporting above, suggested actions are identified that would advance the elimination of child labor in the Philippines (Table 11).

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Gross intake ratio to the last grade of primary education, both sexes (%). Accessed March 15, 2023. For more information, please see "Children's Work and Education Statistics: Sources and Definitions" in the Reference Materials section of this report. http://data.uis.unesco.org/

- ILO. Analysis of Child Economic Activity and School Attendance Statistics from National Household or Child Labor Surveys. Original data from Labour Force Survey (LFS), 2021. Analysis received March 2023. For more information, please see "Children's Work and Education Statistics: Sources and Definitions" in the Reference Materials section of this report.

- U.S. Embassy- Manila. Reporting. January 15, 2020.

- U.S. Embassy- Manila. Reporting. February 7, 2022.