How To Make Recommendation in Case Study (With Examples)

After analyzing your case study’s problem and suggesting possible courses of action , you’re now ready to conclude it on a high note.

But first, you need to write your recommendation to address the problem. In this article, we will guide you on how to make a recommendation in a case study.

Table of Contents

What is recommendation in case study, what is the purpose of recommendation in the case study, 1. review your case study’s problem, 2. assess your case study’s alternative courses of action, 3. pick your case study’s best alternative course of action, 4. explain in detail why you recommend your preferred course of action, examples of recommendations in case study, tips and warnings.

The Recommendation details your most preferred solution for your case study’s problem.

After identifying and analyzing the problem, your next step is to suggest potential solutions. You did this in the Alternative Courses of Action (ACA) section. Once you’re done writing your ACAs, you need to pick which among these ACAs is the best. The chosen course of action will be the one you’re writing in the recommendation section.

The Recommendation portion also provides a thorough justification for selecting your most preferred solution.

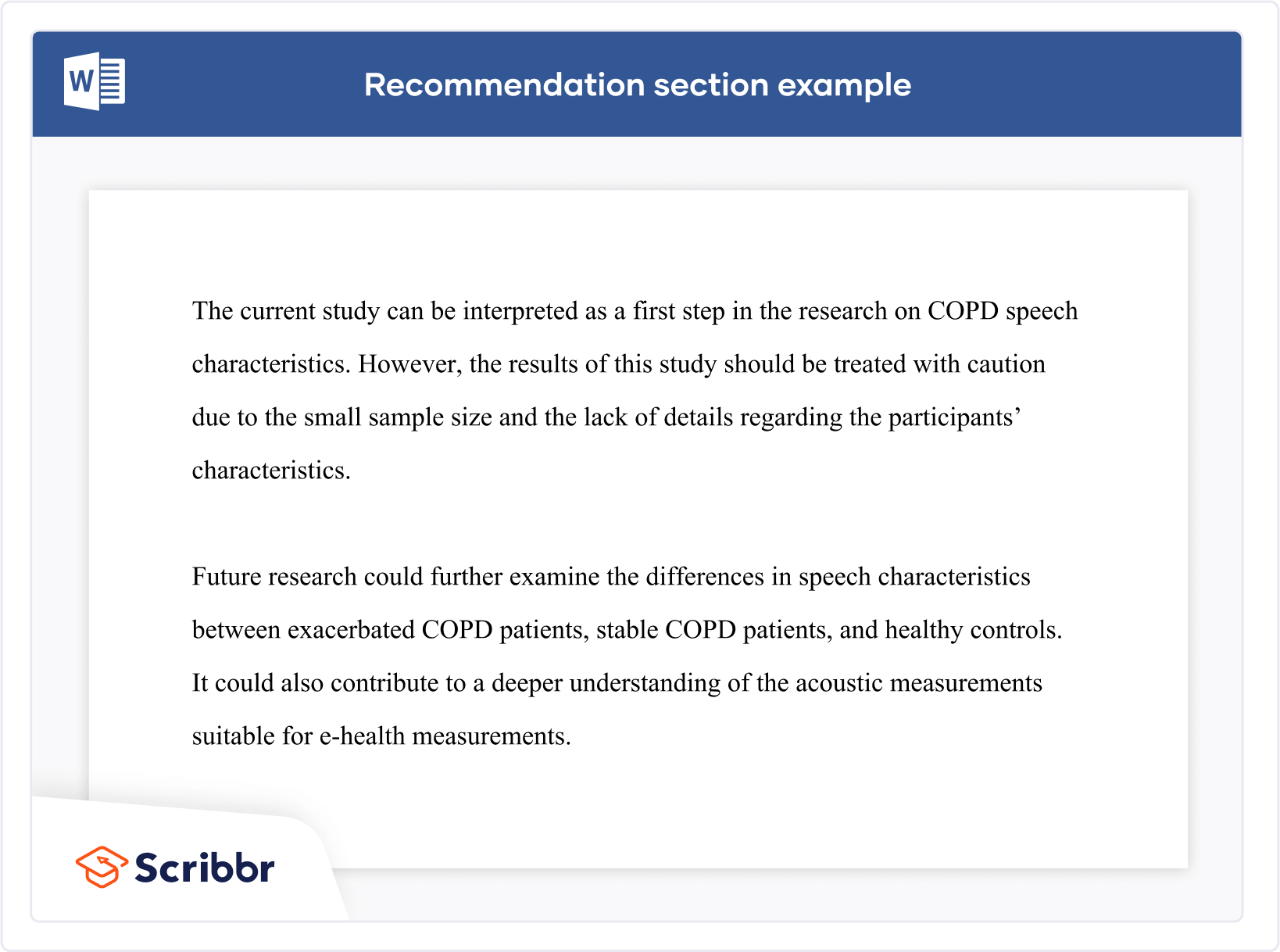

Notice how a recommendation in a case study differs from a recommendation in a research paper . In the latter, the recommendation tells your reader some potential studies that can be performed in the future to support your findings or to explore factors that you’re unable to cover.

Your main goal in writing a case study is not only to understand the case at hand but also to think of a feasible solution. However, there are multiple ways to approach an issue. Since it’s impossible to implement all these solutions at once, you only need to pick the best one.

The Recommendation portion tells the readers which among the potential solutions is best to implement given the constraints of an organization or business. This section allows you to introduce, defend, and explain this optimal solution.

How To Write Recommendation in Case Study

You cannot recommend a solution if you are unable to grasp your case study’s issue. Make sure that you’re aware of the problem as well as the viewpoint from which you want to analyze it .

Once you’ve fully grasped your case study’s problem, it’s time to suggest some feasible solutions to address it. A separate section of your manuscript called the Alternative Courses of Action (ACA) is dedicated to discussing these potential solutions.

Afterward, you need to evaluate each ACA by identifying its respective advantages and disadvantages.

After evaluating each proposed ACA, pick the one you’ll recommend to address the problem. All alternatives have their pros and cons so you must use your discretion in picking the best among these ACAs.

To help you decide which ACA to pick, here are some factors to consider:

- Realistic : The organization must have sufficient knowledge, expertise, resources, and manpower to execute the recommended solution.

- Economical: The recommended solution must be cost-effective.

- Legal: The recommended solution must adhere to applicable laws.

- Ethical: The recommended solution must not have moral repercussions.

- Timely: The recommended solution can be executed within the expected timeframe.

You may also use a decision matrix to assist you in picking the best ACA 1 . This matrix allows you to rank the ACAs based on your criteria. Please refer to our examples in the next section for an example of a Recommendation formed using a decision matrix.

Provide your justifications for why you recommend your preferred solution. You can also explain why other alternatives are not chosen 2 .

To help you understand how to make recommendations in a case study, let’s take a look at some examples below.

Case Study Problem : Lemongate Hotel is facing an overwhelming increase in the number of reservations due to a sudden implementation of a Local Government policy that boosts the city’s tourism. Although Lemongate Hotel has a sufficient area to accommodate the influx of tourists, the management is wary of the potential decline in the hotel’s quality of service while striving to meet the sudden increase in reservations.

Alternative Courses of Action:

- ACA 1: Relax hiring qualifications to employ more hotel employees to ensure that sufficient human resources can provide quality hotel service

- ACA 2: Increase hotel reservation fees and other costs as a response to the influx of tourists demanding hotel accommodation

- ACA 3: Reduce privileges and hotel services enjoyed by each customer so that hotel employees will not be overwhelmed by the increase in accommodations.

Recommendation:

Upon analysis of the problem, it is recommended to implement ACA 1. Among all suggested ACAs, this option is the easiest to execute with the minimal cost required. It will not also impact potential profits and customers’ satisfaction with hotel service.

Meanwhile, implementing ACA 2 might discourage customers from making reservations due to higher fees and look for other hotels as substitutes. It is also not recommended to do ACA 3 because reducing hotel services and privileges offered to customers might harm the hotel’s public reputation in the long run.

The first paragraph of our sample recommendation specifies what ACA is best to implement and why.

Meanwhile, the succeeding paragraphs explain that ACA 2 and ACA 3 are not optimal solutions due to some of their limitations and potential negative impacts on the organization.

Example 2 (with Decision Matrix)

Case Study: Last week, Pristine Footwear released its newest sneakers model for women – “Flightless.” However, the management noticed that “Flightless” had a mediocre sales performance in the previous week. For this reason, “Flightless” might be pulled out in the next few months. The management must decide on the fate of “Flightless” with Pristine Footwear’s financial performance in mind.

- ACA 1: Revamp “Flightless” marketing by hiring celebrities/social media influencers to promote the product

- ACA 2: Improve the “Flightless” current model by tweaking some features to fit current style trends

- ACA 3: Sell “Flightless” at a lower price to encourage more customers

- ACA 4: Stop production of “Flightless” after a couple of weeks to cut losses

Decision Matrix

Recommendation

Based on the decision matrix above 3 , the best course of action that Pristine Wear, Inc. must employ is ACA 3 or selling “Flightless” shoes at lower prices to encourage more customers. This solution can be implemented immediately without the need for an excessive amount of financial resources. Since lower prices entice customers to purchase more, “Flightless” sales might perform better given a reduction in its price.

In this example, the recommendation was formed with the help of a decision matrix. Each ACA was given a score of between 1 – 4 for each criterion. Note that the criterion used depends on the priorities of an organization, so there’s no standardized way to make this matrix.

Meanwhile, the recommendation we’ve made here consists of only one paragraph. Although the matrix already revealed that ACA 3 tops the selection, we still provided a clear explanation of why it is the best.

- Recommend with persuasion 4 . You may use data and statistics to back up your claim. Another option is to show that your preferred solution fits your theoretical knowledge about the case. For instance, if your recommendation involves reducing prices to entice customers to buy higher quantities of your products, you may invoke the “law of demand” 5 as a theoretical foundation of your recommendation.

- Be prepared to make an implementation plan. Some case study formats require an implementation plan integrated with your recommendation. Basically, the implementation plan provides a thorough guide on how to execute your chosen solution (e.g., a step-by-step plan with a schedule).

- Manalili, K. (2021 – 2022). Selection of Best Applicant (Unpublished master’s thesis). Bulacan Agricultural State College. Retrieved September 23, 2022, from https://www.studocu.com/ph/document/bulacan-agricultural-state-college/business-administration/case-study-human-rights/19062233.

- How to Analyze a Case Study. (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2022, from https://wps.prenhall.com/bp_laudon_essbus_7/48/12303/3149605.cw/content/index.html

- Nguyen, C. (2022, April 13). How to Use a Decision Matrix to Assist Business Decision Making. Retrieved September 23, 2022, from https://venngage.com/blog/decision-matrix/

- Case Study Analysis: Examples + How-to Guide & Writing Tips. (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2022, from https://custom-writing.org/blog/great-case-study-analysis

- Hayes, A. (2022, January O8). Law of demand. Retrieved September 23, 2022, from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/lawofdemand.asp

Written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

in Career and Education , Juander How

Last Updated September 23, 2022 07:23 PM

Jewel Kyle Fabula

Jewel Kyle Fabula is a Bachelor of Science in Economics student at the University of the Philippines Diliman. His passion for learning mathematics developed as he competed in some mathematics competitions during his Junior High School years. He loves cats, playing video games, and listening to music.

Browse all articles written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

Published on September 15, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on July 18, 2023.

Recommendations in research are a crucial component of your discussion section and the conclusion of your thesis , dissertation , or research paper .

As you conduct your research and analyze the data you collected , perhaps there are ideas or results that don’t quite fit the scope of your research topic. Or, maybe your results suggest that there are further implications of your results or the causal relationships between previously-studied variables than covered in extant research.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What should recommendations look like, building your research recommendation, how should your recommendations be written, recommendation in research example, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about recommendations.

Recommendations for future research should be:

- Concrete and specific

- Supported with a clear rationale

- Directly connected to your research

Overall, strive to highlight ways other researchers can reproduce or replicate your results to draw further conclusions, and suggest different directions that future research can take, if applicable.

Relatedly, when making these recommendations, avoid:

- Undermining your own work, but rather offer suggestions on how future studies can build upon it

- Suggesting recommendations actually needed to complete your argument, but rather ensure that your research stands alone on its own merits

- Using recommendations as a place for self-criticism, but rather as a natural extension point for your work

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

There are many different ways to frame recommendations, but the easiest is perhaps to follow the formula of research question conclusion recommendation. Here’s an example.

Conclusion An important condition for controlling many social skills is mastering language. If children have a better command of language, they can express themselves better and are better able to understand their peers. Opportunities to practice social skills are thus dependent on the development of language skills.

As a rule of thumb, try to limit yourself to only the most relevant future recommendations: ones that stem directly from your work. While you can have multiple recommendations for each research conclusion, it is also acceptable to have one recommendation that is connected to more than one conclusion.

These recommendations should be targeted at your audience, specifically toward peers or colleagues in your field that work on similar subjects to your paper or dissertation topic . They can flow directly from any limitations you found while conducting your work, offering concrete and actionable possibilities for how future research can build on anything that your own work was unable to address at the time of your writing.

See below for a full research recommendation example that you can use as a template to write your own.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

While it may be tempting to present new arguments or evidence in your thesis or disseration conclusion , especially if you have a particularly striking argument you’d like to finish your analysis with, you shouldn’t. Theses and dissertations follow a more formal structure than this.

All your findings and arguments should be presented in the body of the text (more specifically in the discussion section and results section .) The conclusion is meant to summarize and reflect on the evidence and arguments you have already presented, not introduce new ones.

The conclusion of your thesis or dissertation should include the following:

- A restatement of your research question

- A summary of your key arguments and/or results

- A short discussion of the implications of your research

For a stronger dissertation conclusion , avoid including:

- Important evidence or analysis that wasn’t mentioned in the discussion section and results section

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion …”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g., “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

In a thesis or dissertation, the discussion is an in-depth exploration of the results, going into detail about the meaning of your findings and citing relevant sources to put them in context.

The conclusion is more shorter and more general: it concisely answers your main research question and makes recommendations based on your overall findings.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, July 18). How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/recommendations-in-research/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion, how to write a results section | tips & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

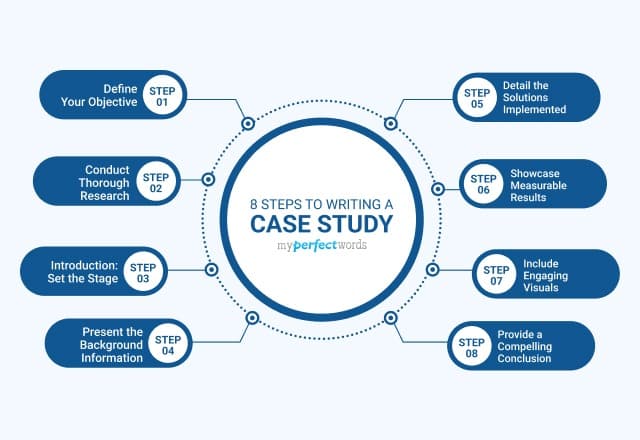

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut off? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should clearly support investigation of the research problem and linked to key findings from your literature review. Be sure to cite any studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for examining the problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your analysis of the case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is common to combine a description of the results with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings Remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations revealed by the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research if that is how the findings can be interpreted from your case.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion

As with any research paper, you should summarize your conclusion in clear, simple language; emphasize how the findings from your case study differs from or supports prior research and why. Do not simply reiterate the discussion section. Provide a synthesis of key findings presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem. If you haven't already done so in the discussion section, be sure to document the limitations of your case study and any need for further research.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to: 1) reiterate the main argument supported by the findings from your case study; 2) state clearly the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem using a case study design in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found from reviewing the literature; and, 3) provide a place to persuasively and succinctly restate the significance of your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with in-depth information about the topic.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize these points for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the conclusion of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration of the case study's findings that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from your case study findings.

Note that, depending on the discipline you are writing in or the preferences of your professor, the concluding paragraph may contain your final reflections on the evidence presented as it applies to practice or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the subject of analysis you have investigated will depend on whether you are explicitly asked to express your observations in this way.

Problems to Avoid

Overgeneralization One of the goals of a case study is to lay a foundation for understanding broader trends and issues applied to similar circumstances. However, be careful when drawing conclusions from your case study. They must be evidence-based and grounded in the results of the study; otherwise, it is merely speculation. Looking at a prior example, it would be incorrect to state that a factor in improving girls access to education in Azerbaijan and the policy implications this may have for improving access in other Muslim nations is due to girls access to social media if there is no documentary evidence from your case study to indicate this. There may be anecdotal evidence that retention rates were better for girls who were engaged with social media, but this observation would only point to the need for further research and would not be a definitive finding if this was not a part of your original research agenda.

Failure to Document Limitations No case is going to reveal all that needs to be understood about a research problem. Therefore, just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study , you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis. For example, the case of studying how women conceptualize the need for water conservation in a village in Uganda could have limited application in other cultural contexts or in areas where fresh water from rivers or lakes is plentiful and, therefore, conservation is understood more in terms of managing access rather than preserving access to a scarce resource.

Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings. If you do not, your reader may question the validity of your analysis, particularly if you failed to document an obvious outcome from your case study research. For example, in the case of studying the accident at the railroad crossing to evaluate where and what types of warning signals should be located, you failed to take into consideration speed limit signage as well as warning signals. When designing your case study, be sure you have thoroughly addressed all aspects of the problem and do not leave gaps in your analysis that leave the reader questioning the results.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education . Rev. ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998; Miller, Lisa L. “The Use of Case Studies in Law and Social Science Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (2018): TBD; Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Putney, LeAnn Grogan. "Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010), pp. 116-120; Simons, Helen. Case Study Research in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2009; Kratochwill, Thomas R. and Joel R. Levin, editors. Single-Case Research Design and Analysis: New Development for Psychology and Education . Hilldsale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992; Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London : SAGE, 2010; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA, SAGE Publications, 2014; Walo, Maree, Adrian Bull, and Helen Breen. “Achieving Economic Benefits at Local Events: A Case Study of a Local Sports Event.” Festival Management and Event Tourism 4 (1996): 95-106.

Writing Tip

At Least Five Misconceptions about Case Study Research

Social science case studies are often perceived as limited in their ability to create new knowledge because they are not randomly selected and findings cannot be generalized to larger populations. Flyvbjerg examines five misunderstandings about case study research and systematically "corrects" each one. To quote, these are:

Misunderstanding 1 : General, theoretical [context-independent] knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical [context-dependent] knowledge. Misunderstanding 2 : One cannot generalize on the basis of an individual case; therefore, the case study cannot contribute to scientific development. Misunderstanding 3 : The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses; that is, in the first stage of a total research process, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building. Misunderstanding 4 : The case study contains a bias toward verification, that is, a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions. Misunderstanding 5 : It is often difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories on the basis of specific case studies [p. 221].

While writing your paper, think introspectively about how you addressed these misconceptions because to do so can help you strengthen the validity and reliability of your research by clarifying issues of case selection, the testing and challenging of existing assumptions, the interpretation of key findings, and the summation of case outcomes. Think of a case study research paper as a complete, in-depth narrative about the specific properties and key characteristics of your subject of analysis applied to the research problem.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (April 2006): 219-245.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Next: Writing a Field Report >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Writing A Case Study

Case Study Examples

Brilliant Case Study Examples and Templates For Your Help

15 min read

People also read

A Complete Case Study Writing Guide With Examples

Simple Case Study Format for Students to Follow

Understand the Types of Case Study Here

It’s no surprise that writing a case study is one of the most challenging academic tasks for students. You’re definitely not alone here!

Most people don't realize that there are specific guidelines to follow when writing a case study. If you don't know where to start, it's easy to get overwhelmed and give up before you even begin.

Don't worry! Let us help you out!

We've collected over 25 free case study examples with solutions just for you. These samples with solutions will help you win over your panel and score high marks on your case studies.

So, what are you waiting for? Let's dive in and learn the secrets to writing a successful case study.

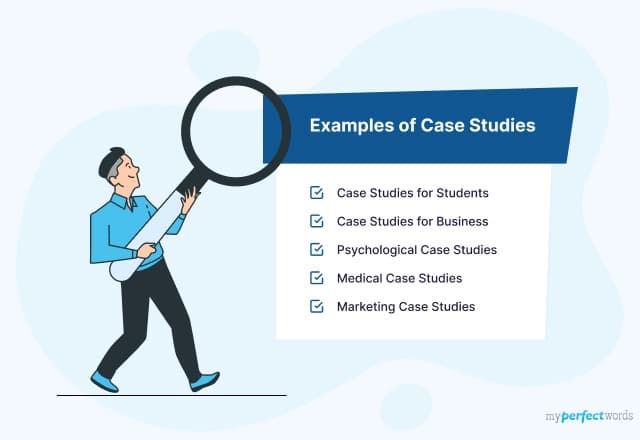

- 1. An Overview of Case Studies

- 2. Case Study Examples for Students

- 3. Business Case Study Examples

- 4. Medical Case Study Examples

- 5. Psychology Case Study Examples

- 6. Sales Case Study Examples

- 7. Interview Case Study Examples

- 8. Marketing Case Study Examples

- 9. Tips to Write a Good Case Study

An Overview of Case Studies

A case study is a research method used to study a particular individual, group, or situation in depth. It involves analyzing and interpreting data from a variety of sources to gain insight into the subject being studied.

Case studies are often used in psychology, business, and education to explore complicated problems and find solutions. They usually have detailed descriptions of the subject, background info, and an analysis of the main issues.

The goal of a case study is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject. Typically, case studies can be divided into three parts, challenges, solutions, and results.

Here is a case study sample PDF so you can have a clearer understanding of what a case study actually is:

Case Study Sample PDF

How to Write a Case Study Examples

Learn how to write a case study with the help of our comprehensive case study guide.

Case Study Examples for Students

Quite often, students are asked to present case studies in their academic journeys. The reason instructors assign case studies is for students to sharpen their critical analysis skills, understand how companies make profits, etc.

Below are some case study examples in research, suitable for students:

Case Study Example in Software Engineering

Qualitative Research Case Study Sample

Software Quality Assurance Case Study

Social Work Case Study Example

Ethical Case Study

Case Study Example PDF

These examples can guide you on how to structure and format your own case studies.

Struggling with formatting your case study? Check this case study format guide and perfect your document’s structure today.

Business Case Study Examples

A business case study examines a business’s specific challenge or goal and how it should be solved. Business case studies usually focus on several details related to the initial challenge and proposed solution.

To help you out, here are some samples so you can create case studies that are related to businesses:

Here are some more business case study examples:

Business Case Studies PDF

Business Case Studies Example

Typically, a business case study discovers one of your customer's stories and how you solved a problem for them. It allows your prospects to see how your solutions address their needs.

Medical Case Study Examples

Medical case studies are an essential part of medical education. They help students to understand how to diagnose and treat patients.

Here are some medical case study examples to help you.

Medical Case Study Example

Nursing Case Study Example

Want to understand the various types of case studies? Check out our types of case study blog to select the perfect type.

Psychology Case Study Examples

Case studies are a great way of investigating individuals with psychological abnormalities. This is why it is a very common assignment in psychology courses.

By examining all the aspects of your subject’s life, you discover the possible causes of exhibiting such behavior.

For your help, here are some interesting psychology case study examples:

Psychology Case Study Example

Mental Health Case Study Example

Sales Case Study Examples

Case studies are important tools for sales teams’ performance improvement. By examining sales successes, teams can gain insights into effective strategies and create action plans to employ similar tactics.

By researching case studies of successful sales campaigns, sales teams can more accurately identify challenges and develop solutions.

Sales Case Study Example

Interview Case Study Examples

Interview case studies provide businesses with invaluable information. This data allows them to make informed decisions related to certain markets or subjects.

Interview Case Study Example

Marketing Case Study Examples

Marketing case studies are real-life stories that showcase how a business solves a problem. They typically discuss how a business achieves a goal using a specific marketing strategy or tactic.

They typically describe a challenge faced by a business, the solution implemented, and the results achieved.

This is a short sample marketing case study for you to get an idea of what an actual marketing case study looks like.

Here are some more popular marketing studies that show how companies use case studies as a means of marketing and promotion:

“Chevrolet Discover the Unexpected” by Carol H. Williams

This case study explores Chevrolet's “ DTU Journalism Fellows ” program. The case study uses the initials “DTU” to generate interest and encourage readers to learn more.

Multiple types of media, such as images and videos, are used to explain the challenges faced. The case study concludes with an overview of the achievements that were met.

Key points from the case study include:

- Using a well-known brand name in the title can create interest.

- Combining different media types, such as headings, images, and videos, can help engage readers and make the content more memorable.

- Providing a summary of the key achievements at the end of the case study can help readers better understand the project's impact.

“The Met” by Fantasy

“ The Met ” by Fantasy is a fictional redesign of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, created by the design studio Fantasy. The case study clearly and simply showcases the museum's website redesign.

The Met emphasizes the website’s features and interface by showcasing each section of the interface individually, allowing the readers to concentrate on the significant elements.

For those who prefer text, each feature includes an objective description. The case study also includes a “Contact Us” call-to-action at the bottom of the page, inviting visitors to contact the company.

Key points from this “The Met” include:

- Keeping the case study simple and clean can help readers focus on the most important aspects.

- Presenting the features and solutions with a visual showcase can be more effective than writing a lot of text.

- Including a clear call-to-action at the end of the case study can encourage visitors to contact the company for more information.

“Better Experiences for All” by Herman Miller

Herman Miller's minimalist approach to furniture design translates to their case study, “ Better Experiences for All ”, for a Dubai hospital. The page features a captivating video with closed-captioning and expandable text for accessibility.

The case study presents a wealth of information in a concise format, enabling users to grasp the complexities of the strategy with ease. It concludes with a client testimonial and a list of furniture items purchased from the brand.

Key points from the “Better Experiences” include:

- Make sure your case study is user-friendly by including accessibility features like closed captioning and expandable text.

- Include a list of products that were used in the project to guide potential customers.

“NetApp” by Evisort

Evisort's case study on “ NetApp ” stands out for its informative and compelling approach. The study begins with a client-centric overview of NetApp, strategically directing attention to the client rather than the company or team involved.

The case study incorporates client quotes and explores NetApp’s challenges during COVID-19. Evisort showcases its value as a client partner by showing how its services supported NetApp through difficult times.

- Provide an overview of the company in the client’s words, and put focus on the customer.

- Highlight how your services can help clients during challenging times.

- Make your case study accessible by providing it in various formats.

“Red Sox Season Campaign,” by CTP Boston

The “ Red Sox Season Campaign ” showcases a perfect blend of different media, such as video, text, and images. Upon visiting the page, the video plays automatically, there are videos of Red Sox players, their images, and print ads that can be enlarged with a click.

The page features an intuitive design and invites viewers to appreciate CTP's well-rounded campaign for Boston's beloved baseball team. There’s also a CTA that prompts viewers to learn how CTP can create a similar campaign for their brand.

Some key points to take away from the “Red Sox Season Campaign”:

- Including a variety of media such as video, images, and text can make your case study more engaging and compelling.

- Include a call-to-action at the end of your study that encourages viewers to take the next step towards becoming a customer or prospect.

“Airbnb + Zendesk” by Zendesk

The case study by Zendesk, titled “ Airbnb + Zendesk : Building a powerful solution together,” showcases a true partnership between Airbnb and Zendesk.

The article begins with an intriguing opening statement, “Halfway around the globe is a place to stay with your name on it. At least for a weekend,” and uses stunning images of beautiful Airbnb locations to captivate readers.

Instead of solely highlighting Zendesk's product, the case study is crafted to tell a good story and highlight Airbnb's service in detail. This strategy makes the case study more authentic and relatable.

Some key points to take away from this case study are:

- Use client's offerings' images rather than just screenshots of your own product or service.

- To begin the case study, it is recommended to include a distinct CTA. For instance, Zendesk presents two alternatives, namely to initiate a trial or seek a solution.

“Influencer Marketing” by Trend and WarbyParker

The case study "Influencer Marketing" by Trend and Warby Parker highlights the potential of influencer content marketing, even when working with a limited budget.

The “Wearing Warby” campaign involved influencers wearing Warby Parker glasses during their daily activities, providing a glimpse of the brand's products in use.

This strategy enhanced the brand's relatability with influencers' followers. While not detailing specific tactics, the case study effectively illustrates the impact of third-person case studies in showcasing campaign results.

Key points to take away from this case study are:

- Influencer marketing can be effective even with a limited budget.

- Showcasing products being used in everyday life can make a brand more approachable and relatable.

- Third-person case studies can be useful in highlighting the success of a campaign.

Marketing Case Study Example

Marketing Case Study Template

Now that you have read multiple case study examples, hop on to our tips.

Tips to Write a Good Case Study

Here are some note-worthy tips to craft a winning case study

- Define the purpose of the case study This will help you to focus on the most important aspects of the case. The case study objective helps to ensure that your finished product is concise and to the point.

- Choose a real-life example. One of the best ways to write a successful case study is to choose a real-life example. This will give your readers a chance to see how the concepts apply in a real-world setting.

- Keep it brief. This means that you should only include information that is directly relevant to your topic and avoid adding unnecessary details.

- Use strong evidence. To make your case study convincing, you will need to use strong evidence. This can include statistics, data from research studies, or quotes from experts in the field.

- Edit and proofread your work. Before you submit your case study, be sure to edit and proofread your work carefully. This will help to ensure that there are no errors and that your paper is clear and concise.

There you go!

We’re sure that now you have secrets to writing a great case study at your fingertips! This blog teaches the key guidelines of various case studies with samples. So grab your pen and start crafting a winning case study right away!

Having said that, we do understand that some of you might be having a hard time writing compelling case studies.

But worry not! Our expert case study writing service is here to take all your case-writing blues away!

With 100% thorough research guaranteed, our professional essay writing service can craft an amazing case study within 6 hours!

So why delay? Let us help you shine in the eyes of your instructor!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Dr. Barbara is a highly experienced writer and author who holds a Ph.D. degree in public health from an Ivy League school. She has worked in the medical field for many years, conducting extensive research on various health topics. Her writing has been featured in several top-tier publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Resource Sharing in Biomedical Research (1996)

Chapter: 8: conclusions and recommendations, 8 conclusions and recommendations.

The foregoing case studies by no means exhaust the list of successful efforts to share biomedical data, materials and facilities with the scientific community as a whole, but the common themes that emerged in discussion of this diverse group of cases encourage the committee to believe that they are representative of the equally successful ventures not considered because of constraints on the committee's time, energy, and funding. These common themes demonstrate some of the necessary ingredients for successful resource sharing, but also surface issues or problems that require further study.

Features of Successful Resource Sharing

Strong scientific leadership in agencies and the research community.

Essential ingredients in successful resource sharing are the leadership of program managers in government agencies who identify opportunities and support them; the leadership of senior scientists who establish the norm for the scientific community by example and commitment to sharing resources; the leadership of scientists who direct existing shared resources to provide quality services at moderate costs; and the commitment of scientific institutions such as universities and professional societies that develop policies to facilitate and enforce resource sharing. The Arabidopsis thaliana genome project's remarkable communal spirit and international character have made it a successful model for scientific cooperation and sharing of research resources.

This project began when program managers in government agencies, recognizing that work on mapping and sequencing the genome of Arabidopsis was accelerating, convened an international series of workshops of leading scientists to devise a long-range plan. The continued commitment of these senior scientists to widespread sharing of information and materials, and the peer pressure and aggressive solicitation of stocks of mutant strains to be made available through distribution centers, have contributed to the almost universal sharing of materials in this community. Similarly the strong leadership of the 22 societies that provide oversight for the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and the strong scientific leadership and management of The Jackson Laboratories (TJL) are strengths of these successful repositories and distributors of resources. A most remarkable example is presented by the Human Genome Center of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), which, by default, has become a major supplier of material resources to the scientific community, without being supported for this function. The extent to which it has provided the leadership and the actual materials that have permitted widespread sharing of genetic materials and information and the forging of important collaborations is remarkable. LLNL has protected the use of this important resource for the research community.

Many of the important institutions in science have an ongoing responsibility to foster a culture of sharing and to continue to advocate for policies that assist the process. Professional societies and journal editors can support sharing of resources by developing appropriate policies guiding publications and responsibilities for making data available after publication. The Journal of Biological Chemistry , for example, has such a policy: ''Authors of papers published in the journal are obligated to honor any reasonable request by qualified investigators for unique propagative materials such as cell lines, hybridomas, and DNA clones that are described in the paper.'' Plans are under way to modify the phraseology to restrict the obligation to investigators who want to use the strain for noncommercial purposes and to include computer programs in the materials that have to be shared. In addition, after considerable debate, the policy was established that authors publishing crystallographic data must submit the details, coordinates, and related data to the Protein Data Bank at Brookhaven before publication. The appropriate accession number must be inserted into the manuscript; in a similar way, nucleotide sequences must be submitted to Genbank or a similar database, and the accession number must be inserted into the manuscript.

Adequate Core Funding

The committee observed that an essential ingredient for successful shared facilities or repositories was adequate funding of the core functions. In many cases there is a patchwork of funding from a number of different funding agencies, industry, and grants to support research or further development of the resource, as well as user fees. Sometimes the different streams of dollars may not be available to support the core administration and quality control necessary for resource sharing. This is inefficient and requires much effort on the part of the staff to write numerous proposals to different agencies. For example, at ATCC, decreasing core support is a cause for concern that has forced management to raise costs to purchasers to undesirable levels. The MacCHESS (Macromolecular Crystallography Resource at the Cornell High-Energy Synchrotron Source) case story is an excellent example of coordinated agency and industry support. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is able to piggyback on the support provided by Department of Energy (DOE) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) to open these facilities for use by the biomedical community. The DOE scientific facilities initiative of FY 1996 provided these facilities with increased operational funding to ensure full-time operations and effective running. The seven regional primate research centers established by specific legislation during the 1960s and funded through the National Center for Research Resources are additional excellent examples of shared resources that have stable core funding.

Marketing and Advertising

Advertising, marketing, and general knowledge of the availability of a resource are essential to widespread access; many resources are not shared simply because their existence is not known to scientists who require them. All of the case examples studied in this workshop have a variety of mechanisms for alerting the research community about the availability and costs of their resources. From a marketing point of view, for example, ATCC has a very heterogeneous user group, supplying materials to the clinical, industrial research, university, and government markets, and it reaches these groups through a variety of printed media, electronic media, and workshops. The Jackson Laboratory provides a variety of price lists, lists of stocks with genetic information, data sheets on individual strains, newsletters, and a handbook on doing research in mice. Most of these are also available electronically. A unique resource is the Primate Information Clearinghouse set up by the Washington Regional Primate Research Center (WRPRC) in 1977. This is an international effort to list available primates and researchers desiring primates, as well as to provide literature reviews and other information such as annual

reports, and regulations. The goal of this very extensive effort is to ensure that every animal is utilized to its fullest extent in research to minimize waste or needless use of animals.

Clear Guidelines about Ownership and Access

The cases reviewed at the workshop demonstrated the value of clear guidelines concerning access and ownership, although these differ depending on the resource. No single approach can accommodate the different uses or needs. Project planning should include guidelines for sharing—under what circumstances and with whom data and materials will be shared. This is an essential ingredient in preventing later misunderstandings and problems. There is increasing desire to commercialize and realize the economic benefits of biomedical research, which makes this an especially important and changing feature of shared resources. At ATCC, special collections are being developed with restricted access, and new policies have been formulated to clarify ownership at the time of deposit, with a heavy emphasis on donation to ATCC with no restrictions. In the case of Arabidopsis , the stock centers and databases do not permit restrictions on materials, and strong scientific leadership and peer pressure serve to make these materials and the data freely available to the research community. The Jackson Laboratory provides another example of a resource that has developed explicit policies on ownership and access, and is resisting licensing agreements or agreements that give reach-through rights to commercial entities. The Human Genome Center at LLNL similarly has developed policies to address access to information and materials it distributes in order to protect access for the rest of the research community. For example, LLNL has no bar to commercial use of individual clones but does bar commercial use of whole chromosome-specific libraries.

One important source of funding for shared resources can be user fees. These charges help to subsidize the core operations and maintenance of those research resources that are not currently commercially viable. In addition, at both TJL and ATCC, fees from sales (mice at The Jackson Laboratory and cultures and cell lines at ATCC) help defray the costs of functions such as authentication and quality control, which are essential, if invisible, elements of first-class science.

Clear Policies for Retaining and Discarding Data and Material

There are substantial costs associated with sharing of materials and data. Policies for the disposition of materials and information that are no longer of value will be increasingly important as the body of resources that need to be shared continues to increase more rapidly than the funding available to support them. At The Jackson Laboratory, for example, if a mouse strain is not requested for six months, the strain is stored through cryopreservation, but live colonies are no longer maintained. Prioritizing which resources to support and which not to support will be increasingly important. When the growth of different induced genetic mouse strains recently outpaced the capacity of TJL to produce these for the larger research community, the laboratory established an advisory committee to decide priorities as well as seek additional funding from government agencies.

Quality Control

A critical attribute of a shared resource is that the distributed resource be what it is purported to be. Similarly, mechanisms to ensure the highest-quality research at limited-access resources such as a synchrotron are essential to their ongoing success. The Jackson Laboratory is an excellent example of intensive quality control. First, all mice obtained from the facility are of known health status and genetic quality. Any mouse released by TJL is genetically defined so that individuals who obtain mice will continue to receive genetically identical animals. Strict distribution rules protect and ensure the quality of TJL animals. Scientists are asked to return for new breeders after 10 generations and to limit distribution to their own institution. ATCC also has a long history of providing well-defined and reliable cultures to the research community.

MacCHESS, which represents a saturable resource and thus a different dimension of quality issues, has developed an excellent proposal process and peer review system to facilitate access to the synchrotron and to ensure that only the highest-quality research is conducted at the facility.

Well-Defined Policies for Function of Research and Service at the Facility

The balance between service and research by staff is a fundamental question to be considered by all centralized facilities designed to be resource centers for the scientific community. A shared resource is greatly enhanced by the presence of an excellent scientific staff that is conducting research to

improve the resource and can ensure the quality of the materials. Strong scientists at the resource can also collaborate with and expand the ability of outside scientists to contribute to new knowledge. All of the case studies have strong scientific staff that conduct research to develop the resources, are critical to quality control, and also collaborate widely with outside scientists.

Sophisticated Information Retrieval and Transfer Systems

Rapid exchange of information and widespread access to data are greatly facilitated by sophisticated information retrieval and transfer systems. Rapidly evolving information systems are transforming the way research is conducted and disseminated. A decade ago, a paper that reported an extensive body of DNA sequence data was a landmark. Now such data cannot be published in scientific journals at all but are deposited in data banks. In the case of the Arabidopsis community, a sophisticated set of databases and links among them facilitates reaching the entire research community on an ongoing and almost instantaneous fashion. As soon as genes are sequenced in Chris Somerville's laboratory, for example, the data are sent directly to the University of Minnesota, where the initial analysis takes place. Similarly, information generated by LLNL staff and collaborators goes into the genome database funded by DOE, where the rest of the scientific community has ready access to the information.

Issues and Problems

No meaningful argument can be made against the sharing of scientific resources. No convincing example exists where sharing has had preponderantly damaging or deleterious effects. Sharing almost always results in a total cost reduction, allowing existing research dollars to support a larger total research effort. Sharing has other side benefits including the rapid diffusion of new techniques or methods throughout the scientific user community and, quite often, the catalysis of scientific collaborations based directly or inadvertently on the sharing experience. The issue is, then, not whether there should be sharing, but how to optimize it. The case studies, although providing many good examples of "best practices," also provided the committee with a wealth of unresolved issues and emerging problems that any future sharing effort will have to address.

One Uniform Policy on Resource Sharing is Not Possible

The problems of sharing resources are diverse. Solutions therefore will be similarly diverse. There are differences in the resources to be shared, the needs of stakeholders, and the distribution of resources that stakeholders command. In gathering the material for this report, the committee has dealt with the sharing of data, materials (including experimental subjects), and equipment. It is clear that the optimal procedures for sharing these three classes will differ in most cases. With data, the incremental cost of sharing or wide distribution may be negligible. Thus, sharing as broadly as possible should be the community norm. The amount of regulation or review needed to ensure standards and effectiveness in such sharing can be minimal. Successful examples of such sharing include the nucleic acid, protein sequence, and similar databases (e.g., Genbank, DNA Database of Japan, Genome Science Data Base, SwissProt, Protein Data Base, Genome Data Base), which operate as worldwide consortia with free access to all users.