Our content is reader-supported. Things you buy through links on our site may earn us a commission

Join our newsletter

Never miss out on well-researched articles in your field of interest with our weekly newsletter.

- Project Management

- Starting a business

Get the latest Business News

The history of project management: planning the 20th century.

In some ways, the history of project management is the history of the 20th century. It begins with Henry Gantt inventing his handy chart and continues through many of the most significant events in modern history. World wars, space shots, and the Internet all depended in some way on the development of project management.

Today, project managers may be more likely to be building a photo app than calculating ballistics. However, that may just be a testament to the ubiquitous usefulness of the techniques developed by past managers.

Try some of the best project management software for small businesses.

Key Takeaways: The History of Project Management

- There are four periods in project management history: Before 1958, 1958 to 1979, 1980 to 1994, 1995 to the present.

- Modern project management is considered to start in 1958, characterized by the development of CPM and PERT methods.

- Earlier project management innovations include the Gantt chart around 1910 and administrative work on the Manhattan Project.

- NASA and the Apollo programs contributed to the advancement of project management, mandating use of work breakdown structure, CPM, PERT, and other tools.

- Computer analysis was used in the 1970s, but became much more common in the 1980s and after.

- The first lightweight methodologies were developed in the 1980s in response to the growing needs of software developers.

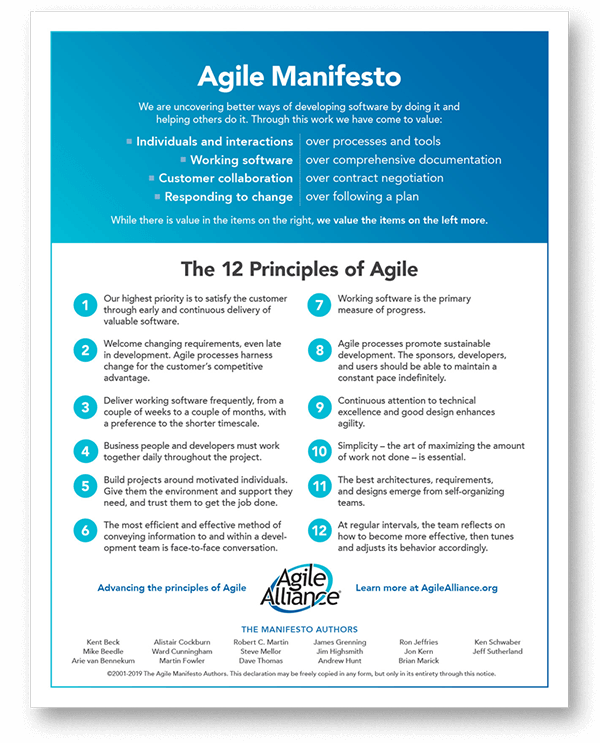

- Agile Manifesto defined the values and principles underlying modern Agile methodologies .

The Four Historical Stages of Modern Project Management

The history of project management is broken into four stages of advancement. A quick look reveals that it’s a fairly brief history, with the first stage including all of human history prior to 1958. It’s around that year that the term ‘project manager’ was first used as we now do.

Before that, project managers couldn’t benefit from project management methodologies . Instead, it’s assumed the project’s success depended on random factors like the talent of individual project members or a particular project management style. Additionally, even large projects usually had one goal everyone focused on, making organization straightforward.

It’s safe to assume the areas project management focuses on have always been of interest, wherever or whenever you happen to be managing projects. However, it was the huge, multi-faceted projects of the cold war that first required modern methods.

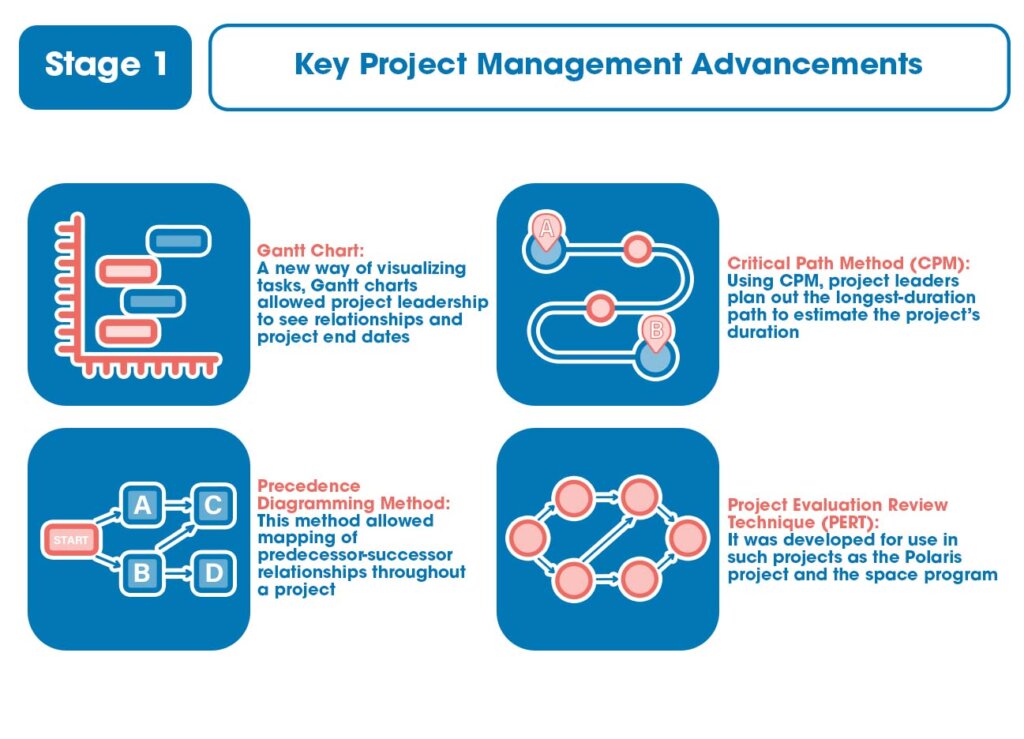

Stage 1 (Prior to 1958)

While we could reach back to the projects which produced the Great Wall or the Pyramids, most histories look to the period around the two world wars for the first true project management techniques.

Henry Gantt popularized the Gantt chart only a few decades earlier in about 1910, allowing a new way to visualize projects. Modern mass production and construction, particularly combined with war efforts, led to more ambitious projects.

Throughout history, project management was considered just another skill, rather than its own discipline. However, historical projects like the Manhattan Project required a more organized approach for effective project management. Moreover, in many cases there was more depending on project success than a profit or deadline.

While there wasn’t anything we would consider a proper project management methodology, many tools we use were developed in this period. Innovators, both in government roles and private industry, created project management tools for their own use. They were then further tested and popularized in other projects.

Selected Key Advancements:

- Gantt Chart : A new way of visualizing tasks is by using Gantt charts which allowed project leadership to see relationships and project end dates. Introduced in the beginning of the 1900s, Gantt charts became popularized after use in the Hoover Dam and Interstate Highway projects.

- Precedence Diagramming Method : A visual way to outline the connections between tasks. The term used today is more often ‘action-on-node’ (AON) network. This method allowed mapping of predecessor-successor relationships throughout a project.

- Critical Path Method (CPM) : One of several network analysis techniques, CPM is a ubiquitous project management tool. Using CPM, project leaders plan out the longest-duration path to estimate the project’s duration.

- Project Evaluation Review Technique (PERT) : Another tool often used to manage projects, it was developed for use in such projects as the Polaris project and the space program.

Defining Projects:

- Manhattan Project: An iconic and successful project, it required a sprawling, multifaceted approach but was nevertheless vital. Project leadership had a purely administrative role, separate from any engineering or research duties.

- Polaris Project : The first submarine-launched nuclear missiles were developed by the Navy Special Projects Office early in the Cold War. On this project, tools like PERT analysis were developed by project managers to help manage schedules.

- Interstate Highway System : Construction of the highway system was one of many capital projects, in the USA and elsewhere, that were begun around this time. Adequate project progress required work to happen in many places at once, requiring tight organization.

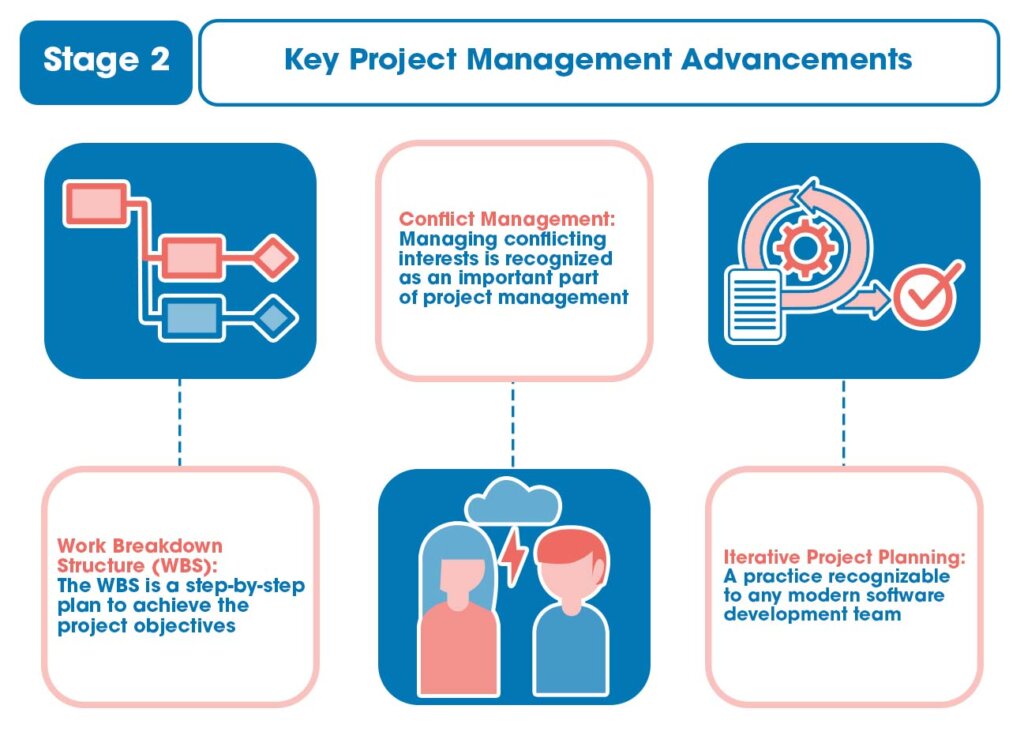

Stage 2 (1958 to 1979)

Most historians agree the modern project management era began around this time. In 1965, Europe’s overarching project management body, the International Project Management Association (IPMA), was founded. Shortly afterwards, in 1969, the Project Management Institute was founded in North America.

The role of project manager was becoming more important in itself, rather than as part of the chief engineer’s job. The space program, including the Apollo moon-shot, was at its peak activity. Due to those projects and others, techniques like CPM and PERT continued to be developed.

Until the early 70s, project management was still applied primarily in defense, construction, and aerospace industries. It wasn’t yet seen as vital to managing successful projects. However, throughout the 70s it began to be applied more widely in other areas. The heavy use of tools like CPM formed an association between project management and systems analysis.

The 70s also saw the development of some tools we now considered essential, such as the work breakdown structure (WBS). Some early inkling of Agile concepts, such as working iteratively, could also be seen.

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) : Another indispensable tool, the WBS is a step-by-step plan to achieving the project objectives. Its use was mandated for government projects over a certain size, which likely led to its popularization.

- Conflict Management : Managing conflicting interests is recognized as an important part of project management. The adoption of matrix organizational techniques, among other things, made conflict management essential for good project outcomes.

- Iterative Project Planning: A practice recognizable to any modern software development team, iterative planning and development was used in some projects, for example, in the space program’s Project Mercury.

- Space Program and Apollo: Including some of the most significant projects in history, the space program relied heavily on project scheduling models and other project planning tools. Refinements on CPM, PERT, and the WBS were all used.

- ARPANET : First coming online in 1971, this network linking various learning and research institutions would form the basis of the modern Internet. Without specific project leaders, it was a collaborative effort.

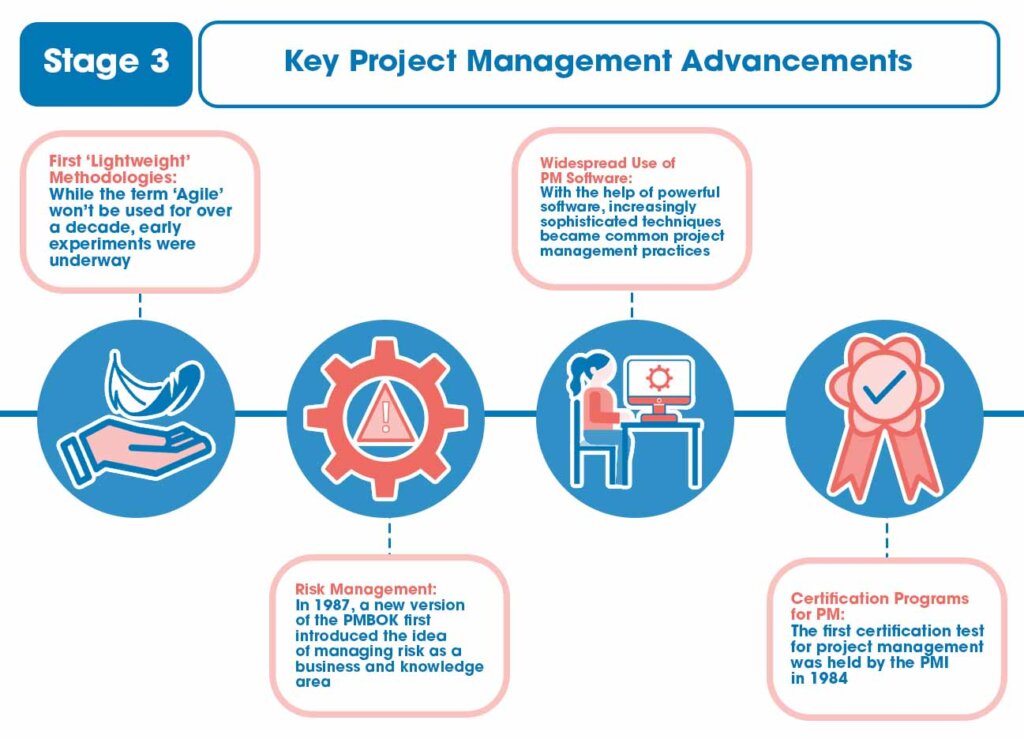

Stage 3 (1980 to 1994)

In the 1980s, project managers began to develop new attitudes to project risk management. The methods used at that point usually referred to now as Waterfall methods often focused on resolving problems as they arose. That had led to project failures and increased cost, if not worse.

Instead, more time was spent planning complex projects from the start, using new methods to anticipate and avoid risks. At the same time, software engineering was becoming useful in every field. Software development projects might be very complex, but not have large administrative teams. Leaner methodologies started to be developed.

In 1981, the Project Management Institute released the Ethics, Standards, and Accreditation project report. It offered the first few project management process groups. In 1986, PMI would go on to issue an expanded version in the first edition of the PMBOK in an international journal, the Project Management Journal.

- First ‘Lightweight’ Methodologies: While the term ‘Agile’ won’t be used for over a decade, early experiments were underway. For example, Scrum was introduced in 1986. Rapid Application Development was developed by 1991 and development of Crystal Methods began the same year.

- Risk Management: In 1987, a new version of the PMBOK first introduced the idea of managing risk as a business process and knowledge area. Focus on this area was prompted by the Challenger disaster and its design project failure.

- Widespread Use of PM Software: Large, mainframe computers were replaced by smaller personal models. With the help of powerful software, increasingly sophisticated techniques became common project management practices.

- Certification Programs for PM: The first certification test for project management was held by the PMI in 1984. Soon after, more stringent certifications were introduced internationally. Management science is formally recognized as a separate discipline, including sub-disciplines like program management.

- English-France Channel Tunnel: The Channel project was complex not only because of its international nature, requiring coordination of governments, financial institutions, and more. It also was complicated by multiple measuring systems, as well as the need to have two groups digging from opposite sides meet in the middle.

- Challenger Investigation: A project in itself, the aftermath of the Challenger disaster was primarily an investigation of another project’s failure. A focus on managing risk and quality assurance followed.

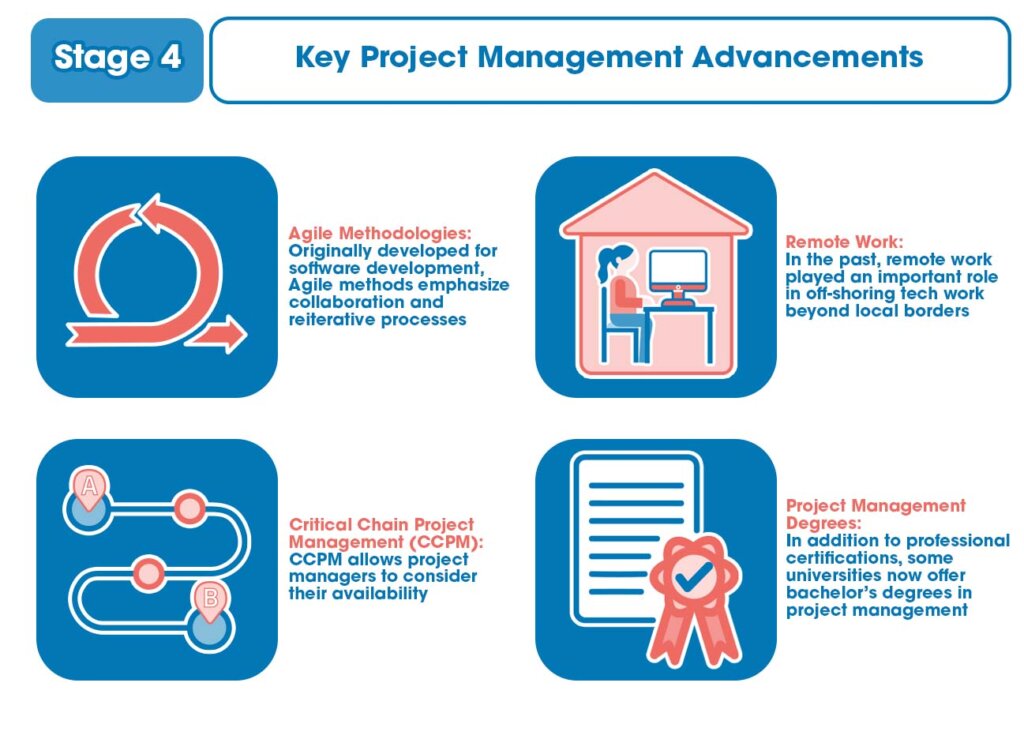

Stage 4 (1995 to Present)

The modern age is defined by the Internet, as true in project management as anywhere. The access and connectivity it allows have transformed methods for organizing and performing work. The project manager role is filled by a project management professional, a career specialist.

The demands of software development prompted the development of new ideas. As a result, in 2001 the Agile Manifesto was published, outlining a new philosophical approach. It brought earlier techniques together as the Agile project management method.

On a wider scale, project management ideas are now applied in corporate management. As a result, concepts from project management have begun to shape business strategy overall, benefiting strategic management. Additionally, a globalized economy means projects have to take multi-cultural considerations into account.

- Agile Methodologies: Originally developed for software development, Agile methods emphasize collaboration and reiterative processes. Projects run using Agile methods are self-directed and deliver working products quickly.

- Remote Work: Recently, remote work allowed a significant increase in the work-from-home rate. Before that, it played an important role in off-shoring tech work beyond local borders. In many ways, team location is no longer a constraint.

- Critical Chain Project Management (CCPM): CCPM is a refinement of the ubiquitous CPM. Where CPM did not take resources into account, CCPM allows project managers to consider their availability.

- Project Management Degrees: In addition to professional certifications, some universities now offer bachelor’s degrees in project management.

- Y2K: As the year 2000 approached, it was realized fundamental software architecture wouldn’t be able to process dates starting with a two. Rather than a single project, Y2K was a tremendous number of parallel software projects around the world that often required coordination, sharing talent and resources.

- Panama Canal Expansion: As global trade increased, the Panama went from a vital passage to a chokepoint causing innumerable delays. The series of complex projects to widen and expand the canal, while simultaneously keeping it open to traffic, experienced delays and hiccups. Eventually costing over 5 billion dollars, it was finished over a year late.

- Large Hadron Collider: With a project lifecycle extending over half a century, LHC construction faced a number of challenges. Funding came from multiple governments. Gathering project requirements involved ongoing research.

The Future of PM

The role of the project manager will continue to be redefined in future projects. Some predict that three trends will support more sophisticated use of PM methods in every aspect of life. Those trends are:

- Digitization.

- Employment.

- Better data analysis.

While the role of project manager tended toward increased specialization in the past, modern project management tools have become widely available. As a result, project management may become a universally integrated process once more, to some extent part of everyone’s job.

Digitization

The transition from a paper-based society to a digital one is going to continue. While that makes tremendous amounts of potentially useful information available, picking out only the useful bits can be very difficult. Storing and accessing all that information also becomes a challenge a successful project must address.

Cloud storage allows for easily scalable IT infrastructure. Machine learning tools help manage that information, while modeling by artificial intelligence may aid in decision making.

Not only is the project manager’s role evolving, but the job of the project team is changing as well. AI, robotics, 3D printing, and other technological advances could perform a lot of repetitive, low-level tasks. Ideally, that would free people up to focus on the more creative aspects.

Additionally, work will become increasingly transnational. People in geographically distant locations can collaborate meaningfully in real-time. Management practices will have to take those changes into account. At the same time, local issues will always have an influence.

Better Data Analysis

Digitizing information means it can be analyzed and assessed easily using powerful computer tools. Study and statistics will reveal in more detail the factors that lead to projects failing and those that ensure project success.

Data analysis may also reveal ways to reduce project costs and more efficiently manage project activities. Doing so in earlier project management phases can help avoid problems later.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for The History of Project Management

The modern era of project management begins in the middle of the 20th century. To manage aspects of war, scientific research, and space travel that took place in that period, basic project management aids were developed. The Critical Path Method was developed by a team at DuPont Chemicals, while PERT was used by a US Navy project. These tools were used by early project managers to estimate when they could deliver projects.

The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) defines five stages or process groups in the management of a project. They are: 1. Initiating. 2. Planning. 3. Executing. 4. Monitoring and Controlling. 5. Closing.

There are many different project management methodologies, some of them for specialized uses. However, they are generally divided into two types: 1. Traditional or Waterfall methods. 2. Agile Methods. Waterfall methods follow an intuitive process, with a complete plan to follow to the end. Agile uses reiterative processes, self-directing, and other principles in a more complex flow.

Final Thoughts on The History of Project Management

With its roots in the great events of the recent past, it seems likely project management will have a profound effect on how we live in the future. It turns out some of the same management tools used in building missiles can also help you write your next paper.

How Much Does it Cost to Form an LLC in Pennsylvania in 2024?

Setting up an LLC in Pennsylvania takes you down a road filled with financial hurdles and paperwork. It seems overwhelming when you first peek at it. Yet, diving deeper into the process opens up savvy ways to manage costs effectively. We’re here to provide you with nifty insights into the nuts and bolts of the …

Cost of Forming an LLC in Texas in 2024

Starting a Limited Liability Company (LLC) in Texas involves more than just completing forms and following rules. It’s also about entering the complex world of finance that comes with starting a business. The process includes various costs, from the initial setup fees to ongoing expenses, which all shape your LLC’s financial situation. This article explores …

New Mexico LLC Cost Guide for 2024

Setting out on the entrepreneur’s trail and starting a Limited Liability Company (LLC) in New Mexico involves several factors, with cost standing out as a pivotal one. Forming an LLC comes with upfront costs, but diving into business ownership in the Land of Enchantment needn’t empty your wallet. This article will detail the expenses linked …

What’s the Cost of Forming an LLC in Maryland in 2024?

Setting up your Limited Liability Company (LLC) in Maryland opens a road filled not just with forms but monetary decisions too. Yet, launching an LLC can feel more financially manageable initially. Armed with the proper insights and aid from trusted LLC service providers like Tailor Brands, you can tackle the complex aspects of this process …

How Much It Cost to Form an LLC in North Dakota: 2024 Guide

Starting an LLC in North Dakota involves more than just submitting the first set of papers. Despite what some might think, it doesn’t cost a lot. This article explains all the costs of creating an LLC in North Dakota. It also looks at budget-friendly options like Tailor Brands, which help keep costs down without cutting …

How Much Would It Cost to Form an LLC in Maine in 2024

Thinking about the money involved in setting up an LLC in Maine? Besides the forms, you also need to think about the costs. The good news is that it might not be as expensive as you think. We specialize in making the different starting and continuing costs of a Maine LLC clear. We can also …

How Much It Cost to Form an LLC in Kansas: 2024 Guide

Entering the business scene in Kansas by starting an LLC comes with its costs. These costs consist of application charges and continuous fees needed to maintain your Limited Liability Company. This guide aims to cover every expense you might face while setting up an LLC in Kansas. For those looking for help with documentation, LLC …

How to Start Your Ecommerce Business in 8 Simple Steps

Starting an Ecommerce business is a common dream, but creating an online store can seem overwhelming. To succeed in Ecommerce entrepreneurship, you need a clear understanding of the steps involved and when you’ll start making a profit. >> Start an Ecommerce Business With Tailor Brands >> What Is an Ecommerce Business? An Ecommerce business functions …

How to Start a Home Healthcare Business: 8 Simple Steps

Do you love to help people and want to have a positive effect on their lives? Starting a home care business might be a rewarding and profitable way to do that. This guide will show you how to begin your own home care business and give you important tips for success. It covers everything you …

How to Start a Delivery Business in 2024: 12 Simple Steps

The delivery services industry is experiencing a surge in demand due to increased orders for instant doorstep delivery. Consumers now enjoy simplified convenience through technology thanks to digitalization. Businesses, both global and local, are restructuring to improve. From 2017 to 2022, the US couriers and local delivery services market experienced an annual growth rate of …

10 Steps on How to Start a Consulting Business in 2024

The strategy consulting market is projected to expand by $70.08 billion from 2022 to 2027, presenting an excellent opportunity for launching a consulting business. A consulting career could suit you well if you excel in your field and are passionate about aiding others to succeed. This guide explores the consulting industry and provides insights on …

How to Start a Cleaning Business in 8 Simple Steps

Starting a cleaning business offers a pathway to entrepreneurship with minimal initial expenses and steady demand. Unlike many other ventures, cleaning services entail relatively low upfront costs and can be launched swiftly with limited funds, provided you’re ready to put in hard work for modest returns and gradual growth. Apart from specialized cleaning supplies and …

How to Start a Vending Machine Business: Pros, Cons & Costs

Vending machines are common, but they offer appealing opportunities for business ventures. The vending industry in the U.S. alone boasts millions of machines and generated more than $8.6 billion in revenue in 2023. This industry attracts both newcomers and seasoned entrepreneurs due to its flexibility. Whether as a weekend endeavor, a low-cost startup, or a …

How to Start a Blogging Business in 2024 to Make Money

If you’re looking to start a blog, you’ve found the right resource. Blogging is a great way to improve your writing, explore new ideas, and establish an online presence based on your interests and expertise. As your blog grows, you can even monetize it or use it to launch a business. Starting a blog is …

How to Start an Event Planning Business in 8 Simple Steps

Event planning focuses on making clients’ ideal events come to life, combining creativity and personalization. It includes a range of businesses, from full-service event coordinators to solo entrepreneurs operating from home. Learning the steps to enter the event planning industry and start your own business is crucial in deciding if this career suits you. This …

Privacy Overview

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

1 A Brief History of Project Management

Peter W.G. Morris is Professor and Head of the School of Construction and Project Management at University College London (UCL). He is the author of over 110 papers and several books on the management of projects. A previous Chairman of the Association for Project Management, he was awarded the Project Management Institute's 2005 Research Achievement Award, IPMA's 2009 Research Award, and APM's 2008 Sir Monty Finniston Life-Time Achievement Award.

- Published: 02 May 2011

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Project Management is a social construct. Our understanding of what it entails has evolved over the years, and is continuing to do so. This article traces the history of this evolution. It does so from the perspective of the professional project management community. It argues that although there are several hundred thousand members of project management professional associations around the world, and many more who deploy tools, techniques, and concepts which they, and others, perceive to be “project management,” there are differing views of the scope of the subject, of its ontology and epistemologies. Maybe this is true of many subjects which are socially constructed, but in the real world of projects, where people are charged with spending significant resources, misapprehension can be serious.

Introduction

Project Management is a social construct. Our understanding of what it entails has evolved over the years, and is continuing to do so. This chapter traces the history of this evolution. It does so from the perspective of the professional project management community. It argues that although there are several hundred thousand members of project management professional associations around the world, and many more who deploy tools, techniques, and concepts which they, and others, perceive to be “project management,” there are differing views of the scope of the subject, of its ontology and epistemologies. Maybe this is true of many subjects which are socially constructed, but in the real world of projects, where people are charged with spending significant resources, misapprehension can be serious.

Later chapters in this book reflect aspects of this uncertainty and some indeed question whether project management is or should be a distinct domain or a profession—having a body of knowledge of its own—at all. Many certainly note the strains between its normative character as a professional discipline and the importance of understanding context when applying it. Nevertheless, despite this uncertainty the fact remains that many thousand people around the world see themselves as competent project professionals having shared “mental models” of what is meant by the discipline. But are these models fit-for-purpose? The chapter argues that in part at least some are, or were, too limited in scope to address the task of delivering projects successfully.

The account unavoidably draws on my personal engagement with, and reflection on, the field. (History is always seen through the eye of the historian.) It is an account of a “reflective practitioner.” Some commentators would doubtless tell the story differently, with different emphases. Hence, referring to the models again, a major theme running through the chapter is the danger of positioning project management with too narrow a focus—as an execution-only oriented discipline: “the application of knowledge, skills, tools and techniques…to meet project requirements” (PMI 2008: 8). (So, who sets the requirements? Isn't that part of the project?) Instead, the chapter argues the benefits of focusing on the management of the project as a whole, from its early stages of conception—to include the elicitation and definition of requirements—to its post-commissioning phases, emphasizing context, the front-end, stakeholders, the various measures of project success, technology and commercial issues, people, and the importance of value and of delivering benefit: what I have termed elsewhere “the management of projects” (Morris and Hough 1987 ; Morris 1994 ; Morris and Pinto 2004 )—as well of course as being master of the traditional core execution skills.

Early history

The word “project” means something thrown forth or out; an idea or conception ( Oxford English Dictionary ); “management” is “the art of arranging physical and human resources towards purposeful ends” (Wren 2005 : 12). “Project Management” means…? The term as such appears not to have been in much if any use before the early 1950s, though of course projects had been managed since the dawn of civilization: the ancient cities of Mesopotamia, the pyramids of Egypt, Stonehenge; history is full of examples of outstanding engineering feats, military campaigns, and other singular undertakings, all attesting to man's ability to accomplish complex, demanding projects. But, barring a few exceptions, it is not until the early 1950s that the language of contemporary project management begins to be invented.

There are several important precursors to this emergence, however. Adamiecki published his harmonogram (effectively a vertical bar chart) in 1903 (Marsh 1975 ). (Following Priestley's idea of putting lines to a horizontal timescale published in 1765 in his Chart of Biography. ) Gantt's bar chart followed in 1917. Formal project coordinator roles appear in the US Army Air Corps in the 1920s (Morris 1994 ), project engineers and project officers (Johnson 2002 ), and project engineers in Exxon and other process engineering companies in the 1930s. And in 1936 Gulick, in a theoretical paper, proposed the idea of the matrix organization (Gulick 1937 ).

There is surprisingly little evidence of the contemporary language and tools of project management to be seen in the Second World War, despite the emergence of Operations Research (OR). The Manhattan Project—the US program to develop the Atom Bomb—is often quoted as one of the earliest examples of modern project management. This may be over-cooking the case: we see in the project—the program—none of the tools or language of today's world of project management.

The 1950s and 1960s: systems development

Project management as a term seems to first appear in 1953, arising in the US defense-aerospace sector (Johnson 2002 ). The emerging advent of thermonuclear-armed ICBMs (InterContinental Ballistic Missiles), and in particular the threat from Russian ICBMs, became an increasingly severe US preoccupation from the early 1950s prompting the US Air Force (and Navy and Army) to look very seriously at how the development of their missiles could be accelerated. Under procurement processes developed by Brigadier Bernard Schriever for the US Air Force (USAF) in 1951, the USAF Air Research and Development and Air Material Commands were required to work together in “special project offices” under a “project manager” who would have full responsibility for the project, and contractors were required to consider the entire “weapons system” on a project basis (Johnson 2002 : 29–31). The Martin (Marietta) company is credited with having created “the first recognizable project management organization” in 1953—in effect a matrix (Johnson 1997 ).

The management of major systems programs

In 1954 Schriever was appointed to head the Atlas ICBM development where he continued his push for integration and urgency, proposing a more holistic approach involving greater use of contractors as system integrators to create the system's specifications and to oversee its development (Hughes 1998 ; Johnson 2002 ). As with Manhattan, Schriever concentrated on building an excellent team. To shorten development times, Schriever also aggressively promoted the practice of concurrency—the parallel planning of all system elements with many normally serial activities being run concurrently (lampooned as “design-as-you-go!”). Unfortunately, concurrency amplified technical problems, as was discovered when missile testing began in late 1956. As a result, Schriever developed rigorous “systems engineering” testing, tracking, and configuration management techniques on the next missile program, Minuteman, which were soon to be applied on the Apollo moon program.

Meanwhile the US Navy was developing its own project and program management practices. Following Teller's 1956 insight that the rate of missile technology development would enable ICBMs to fit in submarines by the early to mid 1960s, when the submarines would be ready (Sapolsky 1972 : 30), the Navy began work on Polaris. Admiral Raborn was appointed as head of the Polaris SPO (Special Projects Office) in 1955. Like Schriever, Raborn emphasized quality of people and team morale. Polaris's SPO exerted more hands-on management than the Air Force, one result of which was the development in 1957 of PERT as a planning and monitoring tool. PERT, the Planning and Evaluation Review Technique, never quite fulfilled its promise but, like Critical Path Method (CPM), invented by DuPont in 1957–9, became iconic as a symbol of the new discipline of project management. Raborn, cleverly and presciently, used PERT as a tool in stakeholder management (though the term was not used), publicizing it to Congress and the Press as the first management tool of the nuclear and computer age.

In 1960 the Air Force implemented Schriever's methods throughout its R&D organizations, documenting them as the “375-series” regulations: a phased life-cycle approach; planning for the entire system up front; project offices with the authority to manage the full development, assisted by systems support contractors (Morrison 1967 ). Essentially project and program management had become the fundamental means to organize complex systems development, and system engineering the engineering mechanism to coordinate them (Johnson 1997 ).

These principles were then given added weight, and thrust, first by the arrival of Robert McNamara as US Secretary of Defense in 1960 and second by NASA (specifically Apollo); from there they spread throughout the USA, and then NATO's, aerospace and electronics industries.

McNamara was an OR enthusiast and a great centralizer. The Program Planning and Budgeting System (PPBS) was his main centralizing tool but he introduced in addition several OR-based practices such as Life-Cycle Costing, Integrated Logistics Support, Quality Assurance, Value Engineering, Configuration Management, and the Work Breakdown Structure, the latter being promoted in 1962 in a joint Department of Defense (DoD)/NASA guide: “PERT/Cost Systems Design.” This “guide” generated a proliferation of systems and much attendant complaining from industry, so instead Earned Value (as an element of DoD's C/SCSC—Cost/Schedule Control Systems Criteria—requirements) was introduced in 1964 as a performance management approach (Morris 1994 ).

Meanwhile Sam Philips, recently a USAF brigadier managing Minuteman, was heading NASA's Apollo program “of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth,” in President Kennedy's historic words of 1961. Apollo brought systems (project) management squarely into the public gaze. Philips imposed configuration management as his core control discipline with rigorous design reviews and work package management—“the devil is in the interface” (Johnson 2002 ). Matrix structures were deployed to harness specialist resources while task forces addressed specific problems. Quality, reliability, and (“all-up”) testing became hugely important as phased testing became too time consuming and costly.

Back on earth, Precedence scheduling had been invented in 1962, by IBM; and in the late 1960s resource allocation scheduling techniques were developed (Morris 1994 ).

Organization and people management

Project management came to be seen, for many years, as epitomized by tools such as PERT and CPM, Work Breakdown Structures, and Earned Value. In reality, however, a more fundamental feature is integration around a clear objective: whether as “single point of integrative responsibility,” in Archibald's pithy phrase (Archibald 1976 ), project “task forces,” or the matrix. This integration should ideally, as per Schriever, be across the whole project life cycle. (Regarding which, it is salutary to note that in the “execution” delivery view of project (see below pp. 20–2), the project manager is generally not the single point of integrative responsibility for the overall project but only for the execution phase.) People skills are also important. As we have seen, Schriever, Raborn, and Philips all emphasized high-level leadership, teamwork, and task performance. Apollo sponsored several studies on team and individual skills (Baker and Wilemon 1974 ; Wilemon and Thamhain 1977 ).

In 1959 the Harvard Business Review published an article on the new integrator role, “the project manager” (Gaddis 1959 ), and by the late 1960s and early 1970s these ideas on organizational integration had begun to attract serious academic attention, for example Lawrence and Lorsch's 1967 study on integration and differentiation, Galbraith's on forms of integration ( 1973 ), and Davis and Lawrence's work on the matrix ( 1977 ). The intellectual environment meanwhile became increasingly attuned to “the systems approach” (Cleland and King 1968 ; Johnson, Kast, and Rosenzweig 1973 ).

As NASA reached (metaphorically and literally) its apogee, project management began now to be seen as a management approach which had potentially very widespread application and benefit. Society could address its major social challenges, NASA claimed, using the same systems approaches that had got man to the moon—employing “adaptive, problem-solving, temporary systems of diverse specialists, linked together by coordinating executives” (Webb 1969 : 23). But it was not going to be so easy, either in NASA, DoD, or the wider world. For, as Sayles and Chandler, two leading academics, pointed out in 1971, “NASA was a closed loop—it set its own schedule, designed its own hardware… As one moves into the (more political) socio-technical area, this luxury disappears” (Sayles and Chandler 1971 : 160).

The birth of the professional project management associations

Simultaneously, with the spread of the matrix and DoD project management techniques, many executives suddenly found themselves pitched into managing projects for the first time. Conferences and seminars on how to do so proliferated. The US Project Management Institute (PMI) was founded in 1969; the International Management Systems Association (also called INTERNET, now the International Project Management Association—IPMA) in 1972, with various European project management associations being formed contemporaneously. Crucially, however, the perspective was essentially a middle management, project execution one centered around the challenges of accomplishing the project goals that had been given, and on the tools and techniques for doing this; it was rarely the successful accomplishment of the project per se , which is after all what really matters. Worse, the performance of projects, already too often bad, was now beginning to deteriorate sharply.

The 1970s to the 1990s: wider application, new strands, and ontological divergence

In some cases, projects were failing precisely because they lacked project management—Concorde for example: an immense concatenation of technological challenges with no effective project management (Morris and Hough 1987 ). But in others, although “best practice” was being earnestly applied, the paradigm was wrong. Concorde's American rival for example was managed by two ex-USAF senior officers according to DoD principles but with no effective program for addressing stakeholder opposition (remember Raborn!)—which in fact led in 1970 to Congress refusing to fund the program and its cancellation (Horwitch 1982 ). The whole nuclear power industry throughout the 1970s and 1980s exhibited similar problems of massive stakeholder (environmentalist) opposition coupled with the challenges of introducing major technological developments during construction (concurrency again, with the concomitant challenge of “regulatory ratcheting” as authorities sought to codify and apply changing technical requirements on power plants already well under construction.) Exceptionally high cost inflation worldwide blew project estimates. The oil and gas industry faced additional costs as it moved into difficult new environments such as Alaska and the North Sea. Even the US weapons programs were not performing well, with problems of technology selection and proving, project definition, supplier selection, and above all concurrency, which DoD at times proscribed as costs grew and at others, chafing at the lack of speed, reluctantly allowed (Morris 1994 ).

Success and failure studies

The causes of project success and failure now began to receive serious attention. DoD had commissioned a number of studies on project performance concluding that technological uncertainty, scope changes, concurrency, and contractor engagement were major issues (Marshall and Meckling 1959 ; Peck and Scherer 1962 ; Summers 1965 ; Perry et al. 1969 ; Large 1971 ). Developing world aid projects were analyzed (Hirschman 1967 ), the World Bank in a major review of project lending between 1945 and 1985 concluding that more attention was needed to technological adequacy, project design, and institution-building (Baum and Tolbert 1985 ). The US General Accounting Office and the UK National Audit Office conducted several highly critical reviews of publicly funded projects. Various academic and other research bodies reported on energy and power plants, systems projects, R&D projects, autos, and airports (Morris 1994 ).

In fact, Morris and Hough in their 1987 study of project success and failure, The Anatomy of Major Projects , listed 34 studies covering 1,536 projects and programs of the 1960s and 1970s (and added a further 8 of their own). Typical sources of difficulty were: unclear success criteria, changing sponsor strategy, poor project definition, technology (fascination with; uncertainty of; design management), concurrency, poor quality assurance, poor linkage with sales and marketing, inappropriate contracting strategy, unsupportive political environment, lack of top management support, inflation, funding difficulties, poor control, inadequate manpower, and geophysical conditions. Most of these factors fell outside the standard project management rubric of the time, as expressed in the textbooks and conference hall floors and as would soon be formalized by PMI in its Body of Knowledge (PMI 2008).

Later studies of project success and failure, such as those by Miller and Lessard ( 2000 ) on very large engineering projects, Flyvbjerg, Bruzelius, and Rothengatter ( 2003 ) on road and rail projects, and Meier ( 2008 ) on US defense and intelligence projects, as well as the notorious CHAOS Reports by Standish ( 1994 and later) on software development projects, emphasized similar factors, namely:

the importance of managing the front-end project definition stages of a project. 1 (DoD had come to the same conclusion, following the US 1972 Commission on Government Procurement, with its creation of the front-end Milestone 0);

the pivotal role of the owner (or sponsor);

the need to manage in some way project “externalities”.

Miller and Lessard further made the critical distinction between projects' efficiency (on time, in budget, to scope) and effectiveness (achieving the sponsor's objectives) measures, showing that their projects generally did much worse on the latter (around 45 percent) than the former (around 75 percent). (Is it reasonable that effectiveness should be so much worse than efficiency?) But by the time of their report, the early 2000s, the project management community was becoming much more aware of the importance of business value, as we shall see.

These studies signposted a growing bifurcation in the way project management is perceived, with many taking the predominantly middle management, execution, delivery-oriented perspective, others taking a broader, more holistic view where the focus is on managing projects. The difference may at first seem slight but the latter involves managing the front-end development period; the former is focused on activity once requirements have been set. The unit of analysis moves from delivery management to the project as an organizational entity which has to be managed successfully. Both paradigms involve managing multiple elements but the “management of projects” is an immensely richer, more complex domain than execution management. This intellectual contrast was marked clearly in the publication of PMI's “Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge” (BoK) in 1983/7.

Project management Bodies of Knowledge

The drive behind the development of a project management Body of Knowledge (BoK) was the idea then gaining ground that if project management was to be a profession surely there should be some form of certification of competence (Cook 1977 ). This would then require some definition of the distinctive knowledge area that the professional is competent in. The initial 1983 PMI BoK (PMBoK®) identified six knowledge elements: scope, time, cost, quality, human resources, and communications management; the 1987 edition added risk and contract/procurement; the 1996 edition added integration. (There have since been several further updates.)

The UK's Association for Project Management (APM) followed a similar path a few years later but considered the PMI BoK too narrow in its definition of the subject. APM's model was strongly influenced by the “management of projects” paradigm: that managing scope, time, cost, resources, quality, risk, procurement, etc. alone is not enough to assure successful project outcomes. In 1991 APM thus produced a broader document which gave recognition to matters such as objectives, strategy, technology, environment, people, business and commercial issues, and so on. The APM BoK has gone to five revisions, Versions 3 and 5 being based on special research (Morris, Jamieson, and Shepherd 2006 ). In 1998 the IPMA (which today comprises 45 national project management associations representing more than 40,000 members) published its Competence Baseline to support its certification programme (Pannenbacker et al. 1998 ). In doing so it adopted the APM BoK almost wholly as its model of project management. In 2002 the Japanese project management associations, ENAA and EPMF, also produced a broadly based BoK: P2M (Project and Program Management) (ENAA 2002 ).

New product development

Meanwhile during the 1980s a stream of insights began appearing from the product development industries. Their influence was to prove significant. Again the initial impetus was studies of success and failure, notably by Kleinschmidt, Edgett, and Cooper, the result of which was to emphasize a staged approach to development, with strong scrutiny at stage gates where there is a predisposition not to proceed unless assured of the investment and management health of the development process (Cooper 1986 ).

These ideas were taken further in two research programs which were to have a strong influence on practice across project-based sectors—pharmaceuticals and other R&D industries, manufacturing, oil and gas, utilities, systems development: one based at Harvard (Clark and Fujimoto 1990 ; Wheelwright and Clark 1992 ); the other centered at MIT, the International Motor Vehicle Program (IMVP) (Womack, Jones, and Roos 1990 ). Both drew heavily on Japanese auto manufacturers' practices, particularly Toyota's. Clark et al. articulated many of the principles now underlying good project development practice: portfolio selection (in relation to market demands and technology strategy and the pace of scheme development); stage reviews; the “Shusa”—the “large project leader”; project teams representing all the functions critical to overall project success; and the importance of the sponsor. Critically, the Shusa—the “heavyweight project manager”—has as his first role “to provide for the direct interpretation of the market and customer needs” (Wheelwright and Clark 1992 : 33). The (heavyweight) project core team exists throughout the project duration but—reflecting the domain's dual paradigms—project management is positioned in project execution following approval of the project plan!

Supply chain management

Both programs dealt extensively with supply chain issues. The IMVP addressed “lean management”; Clark et al. introduced “alliance or partnered” projects. Lean emphasizes productivity improvements through reduced waste, shorter supply lines, lower inventory, and similar; partnering is about gaining productivity improvements through alignment of supply chain members. Partnering became extremely significant as a supply chain practice in the 1990s and beyond.

Traditional forms of contract had long frustrated project management's goal of achieving project-wide integration. The scope is supposed to be fixed by the tender documents but when changes occur, as they often do, the contractor may be highly motivated to claim for contract variations, particularly since the contract had been awarded to the cheapest bidder. This creates a disposition towards conflict. Further, the contractor only enters the project once the design is substantially complete; this meant that “buildability” inputs are often missed. The 1980s and 1990s saw substantial efforts across many sectors but particularly the whole construction spectrum to address these issues and improve project performance. Partnering, with its move from an essentially transactional to a relationship form of engagement of contractors, with the focus on alignment and performance improvement, was an important element of this move for change.

Concurrent engineering

Simultaneous development, or concurrent engineering, was a major theme of both the IMVP and Harvard auto programs. The new practice of concurrent engineering was a more successful, sophisticated version of concurrency, avoiding the problems which had so encumbered project management since the days of Schriever. Concurrent engineering comprises parallel working where possible (simultaneous engineering); integrated teams drawing on all the functional skills needed to develop and deliver the total product (marketing, design, production—hence design-for-manufacturability, design-to-cost, etc.); integrated data modeling; and a propensity to delay decision-taking for as long as possible (Gerwin and Susman 1996).

Concurrency was often really part of the broader issue of how to manage technical innovation in a project environment. Various solutions began to emerge in the 1980s: prototyping off-line so that only proven technology is used in commercially sensitive projects (compare the nuclear power story with its 330 mW prototype plants!); rapid prototyping where quick impressions could be gained by quasi-mock-ups; use of pre-planned product improvements (P 3 I), particularly on shared platforms—a form of program management (Wheelwright and Clark 1992 ).

Technology management

Slowly the projects world got better at managing technical uncertainty—but not always. Defense, and intelligence, continues as an exception: the case for technology push and urgency may simply be so great for national security that the rules have to be disregarded—with predictable consequences. Hence Meier in 2008 reporting on a CIA/DoD study: “most unsuccessful programs (studied) fail at the beginning. The principal causes of (cost and schedule) growth…can be traced to…immature technology, lack of corporate technology roadmaps, requirements instability, ineffective acquisition strategy, unrealistic program baselines, inadequate systems engineering” (Meier 2008 ).

At the heart of many project difficulties lies the crucial issue of requirements. For if one isn't clear on what is required, it shouldn't be a surprise if one doesn't get it. The only trouble is, it's often very hard to do this. In building, architects take “the brief” from their clients—usually followed by scheme designs, specifications, and detailed design. In software (and many systems) projects the product is less physically obvious and harder to visualize and articulate. Requirements management (engineering) rose into prominence in the late 1980s (Davis, Hickey, and Zweig 2004 ). Several systems development models were published in the 1980s and 1990s—the Waterfall, Spiral, and Vee (Forsberg, Mooz, and Cotterman 1996 )—all emphasizing a move from user, system, and business requirements (requirements being solution free), through specifications, systems design, and build, and then back through mirrored levels of testing (verification and validation).

The extent to which project management should be responsible for ensuring that requirements are adequately defined is typical of the conceptual problem of the discipline: should project management cover the management of the front-end, including development of the requirements; or just the realization of these requirements, once these are fixed? (The latter being the view of PMBoK® and many systems engineers, but not of the more holistic “management of projects” approach.)

Quality management

Quality is seen by many as a technology measure. The “House of Quality”/QFD (Quality Function Deployment), for example, which links critical customer attributes to design parameters, is of this school. But, as the Quality gurus—Deming, Crosby, Juran, Ishikawa—of the 1970s and 1980s insisted, quality relates to the total work effort. It is about more than just technical performance.

The 1980s and 1990s saw a marked impact of quality thinking on project management. Quality Assurance became a standard management practice in many project industries. More fundamental was the increasing popularity of Total Quality Management with its emphasis on performance metrics, stable supplier relationships, and putting the customer first. The former trickled into enterprise-wide project management and benchmarking in the late 1990s; the latter strengthened the philosophy of aligned supply chains (partnering). (Another influence was Deming's contention that improvement isn't possible without statistical stability, which led to the maturity model idea—see below.) An International Standard on Quality Management in Projects (ISO 10006) was even published, in 1997 (ISO 1997/2003).

Health, safety, and environment

A series of high-profile accidents, mostly in transport (shipping, rail) and energy (oil and gas, building construction), in the 1980s propelled Health and Safety to be seen as central project criteria not just as important as the traditional iron triangle trio but much more so. Legislation in the early 2000s strengthened this further.

“Environment,” which of course had become increasingly recognized in the 1980s and 1990s as an important dimension of project management responsibility, partly due to environmental opposition (the nuclear, oil, and transport sectors), sustainability (the Bruntland Commission of 1987), and legislation (such as Environmental Impact Assessments), became widely tagged to Health and Safety. HSE (Health, Safety, and Environment) became inescapably supremely important across a large swathe of project-based industries.

Risks and opportunities

Curiously, although most of the standard project management techniques had been identified by the mid 1960s, risk management does not appear to have been one of them. Probabilistic estimating was of course present in PERT from the outset (and was officially abandoned by 1963) but this is not the same as the formal project risk management process (of identification, assessment, mitigation strategy, and reporting) that was articulated in the 1987 edition of PMBoK®. By the mid 1980s, however, formal procedures of risk management had become a commonly used practice, with software packages available to model the cumulative effect of different probabilities. (Almost always this was assessed on predicted cost or schedule completion, rarely on business benefit).