Username or email *

Password *

Forgotten password?

[email protected]

+44 (0)20 8834 4579

Medicine Personal Statement Examples

Get some inspiration to start writing your Medicine Personal Statement with these successful examples from current Medical School students. We've got Medicine Personal Statements which were successful for universities including Imperial, UCL, King's, Bristol, Edinburgh and more.

Personal Statement Examples

- Read successful Personal Statements for Medicine

- Pay attention to the structure and the content

- Get inspiration to plan your Personal Statement

Personal Statement Example 1

Check out this Medicine Personal Statement which was successful for Imperial, UCL, QMUL and King's.

Personal Statement Example 2

This Personal Statement comes from a student who received Medicine offers from Bristol and Plymouth - and also got an interview at Cambridge.

Personal Statement Example 3

Have a look at this Medicine Personal Statement which was successful for Imperial, Edinburgh, Dundee and Newcastle.

Personal Statement Example 4

Take a look at this Medicine Personal Statement which was successful for King's, Newcastle, Bristol and Sheffield.

Personal Statement Example 5

Pick up tips from this Medicine Personal Statement which was successful for Imperial, Birmingham and Manchester.

Personal Statement Example 6

This Personal Statement comes from a student who got into Graduate Entry Medicine at King's - and also had interviews for Undergraduate Medicine at King's, QMUL and Exeter.

Loading More Content

Great Medical School Personal Statement Examples (2024-2025) Insider’s Guide

A physician and former medical school admissions officer teaches you how to write your medical school personal statement, step by step. Read several full-length medical school personal statement examples for inspiration.

In this article, a former medical school admissions officer explains exactly how to write a stand-out medical school personal statement!

Our goal is to empower you to write a medical school personal statement that reflects your individuality, truest aspirations and genuine motivations.

This guide also includes:

- Real life medical school personal statement examples

- Medical school personal statement inventory template and outline exercise

- AMCAS, TMDSAS, and AACOMAS personal statement prompts

- Advanced strategies to ensure you address everything admissions committees want to know

- The secret to writing a great medical school personal statement

So, if you want your medical school personal statement to earn more more medical school interviews, you will love this informative guide.

Let’s dive right in.

Table of Contents

Medical School Personal Statement Fundamentals

If you are getting ready to write your medical school personal statement for the 2024-2025 application year, you may already know that almost 60% of medical school applicants are not accepted every year . You have most likely also completed all of your medical school requirements and have scoured the internet for worthy medical school personal statement examples and guidance.

You know the medical school personal statement offers a crucial opportunity to show medical schools who you are beyond your GPA and MCAT score .

It provides an opportunity to express who you are as an individual, the major influences and background that have shaped your interests and values, what inspired you to pursue medicine, and what kind of a physician you envision yourself becoming.

However, with so much information online, you are not sure who to trust. We are happy you have found us!

Because the vast majority of people offering guidance are not former admissions officers or doctors , you must be careful when searching online.

We are real medical school admissions insiders and know what goes on behind closed doors and how to ensure your medical school personal statement has broad appeal while highlighting your most crucial accomplishments, perspectives, and insights.

With tight limits on space, it can be tough trying to decide what to include in your medical school personal statement to make sure you stand out. You must think strategically about how you want to present your personal “big picture” while showing you possess the preprofessional competencies med schools are seeking.

When a medical school admissions reviewer finishes reading your medical school personal statement, ask yourself:

- What are the most important things you want that person to remember about you?

- Does your medical school personal statement sum up your personality, interests, and talents?

- Does your medical school personal statement sound as if it’s written from the heart?

It’s pretty obvious to most admissions reviewers when applicants are trying too hard to impress them. Being authentic and upfront about who you are is the best way to be a memorable applicant.

The Biggest Medical School Personal Statement Mistakes

The most common medical school personal statement mistake we see students make is that they write about:

- What they have accomplished

- How they have accomplished it

By including details on what you have accomplished and how, you will make yourself sound like every other medical school applicant.

Most medical school applicants are involved in similar activities: research, clinical work, service, and social justice work.

To stand out, you must write from the heart making it clear you haven’t marched through your premedical years and checking boxes.

We also strongly discourage applicants from using ChatGPT or any AI bot to write their medical school personal statement. Writing in your own voice is essential and using anything automated will undermine success.

The Medical School Personal Statement Secret

MedEdits students stand out in the medical school personal statement because in their personal statements they address:

WHY they have accomplished what they have.

In other words, they write in more detail about their passions, interests, and what is genuinely important to them.

It sounds simple, we know, but by writing in a natural way, really zeroing in on WHY YOU DO WHAT YOU DO, you will appeal to a wide variety of people in a humanistic way.

MedEdits students have done extremely well in the most recent medical school admissions cycle. Many of these applicants have below average “stats” for the medical schools from which they are receiving interviews and acceptances.

Why? How is that possible? They all have a few things in common:

- They write a narrative that is authentic and distinctive to them.

- They write a medical school personal statement with broad appeal (many different types of people will be evaluating your application; most are not physicians).

- They don’t try too hard to impress; instead they write about the most impactful experiences they have had on their path to medical school.

- They demonstrate they are humble, intellectual, compassionate, and committed to a career in medicine all at the same time.

Keep reading for a step by step approach to write your medical school personal statement.

“After sitting on a medical school admissions committee for many years, I can tell you, think strategically about how you want to present your personal “big picture.” We want to know who you are as a human being.”

As physicians, former medical school faculty, and medical school admissions committee members, this article will offer a step by step guide to simplify the medical school personal statement brainstorming and writing process.

By following the proven strategies outlined in this article, you will be and to write a personal statement that will earn you more medical school interviews . This proven approach has helped hundreds of medical school applicants get in to medical school the first time they apply!

Learn the 2024-2025 Medical School Personal Statement Prompts ( AMCAS , TMDSAS , AACOMAS )

The personal statement is the major essay portion of your primary application process. In it, you should describe yourself and your background, as well as any important early exposures to medicine, how and why medicine first piqued your interest, what you have done as a pre med, your personal experiences, and how you became increasingly fascinated with it. It’s also key to explain why medicine is the right career for you, in terms of both personal and intellectual fulfillment, and to show your commitment has continued to deepen as you learned more about the field.

The personal statement also offers you the opportunity to express who you are outside of medicine. What are your other interests? Where did you grow up? What did you enjoy about college? Figuring out what aspects of your background to highlight is important since this is one of your only chances to express to the med school admissions committee before your interview what is important to you and why.

However, it is important to consider the actual personal statement prompt for each system through which you will apply, AMCAS, AACOMAS, and TMDSAS, since each is slightly different.

Getting into a medical school has never been more competitive. Let the experts at MedEdits help you with your medical school application materials. We’ve worked with more than 5,000 students and 94% have been admitted to medical school.

Need help with your Personal Statement?

Schedule a free 15 Minute Consultation with a MedEdits expert.

2024 AMCAS Personal Statement Prompt

The AMCAS personal statement instructions are as follows:

Use the Personal Comments Essay as an opportunity to distinguish yourself from other applicants. Consider and write your Personal Comments Essay carefully; many admissions committees place significant weight on the essay. Here are some questions that you may want to consider while writing the essay:

- Why have you selected the field of medicine?

- What motivates you to learn more about medicine?

- What do you want medical schools to know about you that hasn’t been disclosed in other sections of the application?

In addition, you may wish to include information such as:

- Unique hardships, challenges, or obstacles that may have influenced your educational pursuits

- Comments on significant fluctuations in your academic record that are not explained elsewhere in your application

As you can see, these prompts are not vague; there are fundamental questions that admissions committees want you to answer when writing your personal statement. While the content of your statement should be focused on medicine, answering the open ended third question is a bit trickier.

The AMCAS personal statement length is 5,300 characters with spaces maximum.

2024 TMDSAS Personal Statement Prompt

The TMDSAS personal statement is one of the most important pieces of your medical school application.

The TMDSAS personal statement prompt is as follows:

Explain your motivation to seek a career in medicine. Be sure to include the value of your experiences that prepare you to be a physician.

This TMDSAS prompt is very similar to the AMCAS personal statement prompt. The TMDSAS personal statement length is 5,000 characters with spaces whereas the AMCAS personal statement length is 5,300 characters with spaces. Most students use the same essay (with very minor modifications, if necessary) for both application systems.

You’ve been working hard on your med school application, reading medical school personal statement examples, editing, revising, editing and revising. Make sure you know where you’re sending your personal statement and application. Watch this important medical school admissions statistics video.

2024 AACOMAS Personal Statement Prompt

The AACOMAS personal statement is for osteopathic medical schools specifically. As with the AMCAS statement, you need to lay out your journey to medicine as chronologically as possible in 5,300 characters with spaces or less. So you essentially have the same story map as for an AMCAS statement. Most important, you must show you are interested in osteopathy specifically. Therefore, when trying to decide what to include or leave out, prioritize any osteopathy experiences you have had, or those that are in line with the osteopathic philosophy of the mind-body connection, the body as self-healing, and other tenets.

Medical School Application Timeline and When to Write your Personal Statement

If you’re applying to both allopathic and osteopathic schools, you can most likely use the same medical school personal statement for both AMCAS and AACOMAS. In fact, this is why AACOMAS changed the personal statement length to match the AMCAS length several years ago.

Most medical school personal statements can be used for AMCAS and AACOMAS.

Know the Required Medical School Personal Statement Length

Below are the medical schools personal statement length limits for each application system. As you can see, they are all very similar. When you start brainstorming and writing your personal statement, keep these limits in mind.

AMCAS Personal Statement Length : 5,300 characters with spaces.

As per the AAMC website : “The available space for this essay is 5,300 characters (spaces are counted as characters), or approximately one page. You will receive an error message if you exceed the available space.”

AACOMAS Personal Statement Length : 5,300 characters with spaces

TMDSAS Personal Statement Length : 5,000 characters with spaces

As per the TMDSAS Website (Page 36): “The personal essay asks you to explain your motivation to seek a career in medicine. You are asked to include the value of your experiences that prepare you to be a physician. The essay is limited to 5000 characters, including spaces.”

Demonstrate Required Preprofessional Competencies

Next, your want to be aware of the nine preprofessional core competencies as outlined by the Association of American Medical Colleges . Medical school admissions committees want to see, as evidenced by your medical school personal statement and application, that you possess these qualities and characteristics. Now, don’t worry, medical school admissions committees don’t expect you to demonstrate all of them, but, you should demonstrate some.

- Service Orientation

- Social Skills

- Cultural Competence

- Oral Communication

- Ethical Responsibility to Self and Others

- Reliability and Dependability

- Resilience and Adaptability

- Capacity for Improvement

In your personal statement, you might be able to also demonstrate the four thinking and reasoning competencies:

- Critical Thinking

- Quantitative Reasoning

- Written Communication

- Scientific Inquiry

So, let’s think about how to address the personal statement prompts in a slightly different way while ensuring you demonstrate the preprofessional competencies. When writing your personal statement, be sure it answers the four questions that follow and you will “hit” most of the core competencies listed above.

1. What have you done that supports your interest in becoming a doctor?

I always advise applicants to practice “evidence based admissions.” The reader of your essay wants to see the “evidence” that you have done what is necessary to understand the practice of medicine. This includes clinical exposure, research, and community service, among other activities.

2. Why do you want to be a doctor?

This may seem pretty basic – and it is – but admissions officers need to know WHY you want to practice medicine. Many applicants make the mistake of simply listing what they have done without offering insights about those experiences that answer the question, “Why medicine?” Your reasons for wanting to be a doctor may overlap with those of other applicants. This is okay because the experiences in which you participated, the stories you can tell about those experiences, and the wisdom you gained are completely distinct—because they are only yours.

“In admissions committee meetings we were always interested in WHY you wanted to earn a medical degree and how you would contribute to the medical school community.”

Medical school admissions committees want to know that you have explored your interest deeply and that you can reflect on the significance of these clinical experiences and volunteer work. But writing only that you “want to help people” does not support a sincere desire to become a physician; you must indicate why the medical profession in particular—rather than social work, teaching, or another “helping” profession—is your goal.

3. How have your experiences influenced you?

It is important to show how your experiences are linked and how they have influenced you. How did your experiences motivate you? How did they affect what else you did in your life? How did your experiences shape your future goals? Medical school admissions committees like to see a sensible progression of involvements. While not every activity needs to be logically “connected” with another, the evolution of your interests and how your experiences have nurtured your future goals and ambitions show that you are motivated and committed.

4. Who are you as a person? What are your values and ideals?

Medical school admissions committees want to know about you as an individual beyond your interests in medicine, too. This is where answering that third open ended question in the prompt becomes so important. What was interesting about your background, youth, and home life? What did you enjoy most about college? Do you have any distinctive passions or interests? They want to be convinced that you are a good person beyond your experiences. Write about those topics that are unlikely to appear elsewhere in your statement that will offer depth and interest to your work and illustrate the qualities and characteristics you possess.

Related Articles:

- How to Get into Stanford Medical School

- How to Get into NYU Medical School

- How To Get Into Columbia Medical School

- How To Get Into UT Southwestern Medical School

- How To Get Into Harvard Medical School

Complete Your Personal Inventory and Outline (Example Below)

The bulk of your essay should be about your most valuable experiences, personal, academic, scholarly, clinical, academic and extracurricular activities that have impacted your path to medical school and through which you have learned about the practice of medicine. The best personal statements cover several topics and are not narrow in scope. Why is this important? Many different people with a variety of backgrounds, interests, and ideas of what makes a great medical student will be reading your essay. You want to make sure you essay has broad appeal.

The following exercise will help you to determine what experiences you should highlight in your personal statement.

When composing your personal statement, keep in mind that you are writing, in effect, a “story” of how you arrived at this point in your life. But, unlike a “story” in the creative sense, yours must also offer convincing evidence for your decision to apply to medical school. Before starting your personal statement, create an experience- based personal inventory:

- Write down a list of the most important experiences in your life and your development. The list should be all inclusive and comprise those experiences that had the most impact on you. Put the list, which should consist of personal, extracurricular, and academic events, in chronological order.

- From this list, determine which experiences you consider the most important in helping you decide to pursue a career in medicine. This “experience oriented” approach will allow you to determine which experiences best illustrate the personal competencies admissions committees look for in your written documents. Remember that you must provide evidence for your interest in medicine and for most of the personal qualities and characteristics that medical school admissions committees want to see.

- After making your list, think about why each “most important” experience was influential and write that down. What did you observe? What did you learn? What insights did you gain? How did the experience influence your path and choices?

- Then think of a story or illustration for why each experience was important.

- After doing this exercise, evaluate each experience for its significance and influence and for its “story” value. Choose to write about those experiences that not only were influential but that also will provide interesting reading, keeping in mind that your goal is to weave the pertinent experiences together into a compelling story. In making your choices, think about how you will link each experience and transition from one topic to the next.

- Decide which of your listed experiences you will use for your introduction first (see below for more about your introduction). Then decide which experiences you will include in the body of your personal statement, create a general outline, and get writing!

Remember, you will also have your work and activities entries and your secondary applications to write in more detail about your experiences. Therefore, don’t feel you must pack everything in to your statement!

Craft a Compelling Personal Statement Introduction and Body

You hear conflicting advice about application essays. Some tell you not to open with a story. Others tell you to always begin with a story. Regardless of the advice you receive, be sure to do three things:

- Be true to yourself. Everyone will have an opinion regarding what you should and should not write. Follow your own instincts. Your personal statement should be a reflection of you, and only you.

- Start your personal statement with something catchy. Think about the list of potential topics above.

- Don’t rush your work. Composing thoughtful documents takes time and you don’t want your writing and ideas to be sloppy and underdeveloped.

Most important is to begin with something that engages your reader. A narrative, a “story,” an anecdote written in the first or third person, is ideal. Whatever your approach, your first paragraph must grab your reader’s attention and motivate him to want to continue reading. I encourage applicants to start their personal statement by describing an experience that was especially influential in setting them on their path to medical school. This can be a personal or scholarly experience or an extracurricular one. Remember to avoid clichés and quotes and to be honest and authentic in your writing. Don’t try to be someone who you are not by trying to imitate personal statement examples you have read online or “tell them what you think they want to hear”; consistency is key and your interviewer is going to make sure that you are who you say you are!

When deciding what experiences to include in the body of your personal statement, go back to your personal inventory and identify those experiences that have been the most influential in your personal path and your path to medical school. Keep in mind that the reader wants to have an idea of who you are as a human being so don’t write your personal statement as a glorified resume. Include some information about your background and personal experiences that can give a picture of who you are as a person outside of the classroom or laboratory.

Ideally, you should choose two or three experiences to highlight in the body of your personal statement. You don’t want to write about all of your accomplishments; that is what your application entries are for!

Write Your Personal Statement Conclusion

In your conclusion, it is customary to “go full circle” by coming back to the topic—or anecdote—you introduced in the introduction, but this is not a must. Summarize why you want to be a doctor and address what you hope to achieve and your goals for medical school. Write a conclusion that is compelling and will leave the reader wanting to meet you.

Complete Personal Statement Checklist

When reading your medical school personal statement be sure it:

Shows insight and introspection

The best medical school personal statements tell a great deal about what you have learned through your experiences and the insights you have gained.

You want to tell your story by highlighting those experiences that have been the most influential on your path to medical school and to give a clear sense of chronology. You want your statement always to be logical and never to confuse your reader.

Is interesting and engaging

The best personal statements engage the reader. This doesn’t mean you must use big words or be a literary prize winner. Write in your own language and voice, but really think about your journey to medical school and the most intriguing experiences you have had.

Gives the reader a mental image of who you are

You want the reader to be able to envision you as a caregiver and a medical professional. You want to convey that you would be a compassionate provider at the bedside – someone who could cope well with crisis and adversity.

Illustrates your passion for, and commitment to, medicine

Your reader must be convinced that you are excited about and committed to a career in medicine!

Above all, your personal statement should be about you. Explain to your reader what you have done and why you want to be a doctor with insight, compassion, and understanding.

Medical School Personal Statement Myths

Also keep in mind some common myths about personal statements that I hear quite often:

My personal statement must have a theme.

Not true. The vast majority of personal statements do not have themes. In fact, most are somewhat autobiographical and are just as interesting as those statements that are woven around a “theme.” It is only the very talented writer who can creatively write a personal statement around a theme, and this approach often backfires since the applicant fails to answer the three questions above.

My personal statement must be no longer than one page.

Not true. This advice is antiquated and dates back to the days of the written application when admissions committees flipped through pages. If your personal statement is interesting and compelling, it is fine to use the entire allotted space. The application systems have incorporated limits for exactly this reason! Many students, depending on their unique circumstances, can actually undermine their success by limiting their personal statement to a page. That said, never max out a space just for the sake of doing so. Quality writing and perspectives are preferable to quantity.

My personal statement should not describe patient encounters or my personal medical experiences.

Not true. Again, the actual topics on which you focus in your personal statement are less important than the understanding you gained from those experiences. I have successful clients who have written extremely powerful and compelling personal statements that included information about clinical encounters – both personal and professional. Write about whichever experiences were the most important on your path to medicine. It’s always best, however, to avoid spending too much space on childhood and high school activities. Focus instead on those that are more current.

In my personal statement I need to sell myself.

Not exactly true. You never want to boast in your personal statement. Let your experiences, insights, and observations speak for themselves. You want your reader to draw the conclusion – on his or her own – that you have the qualities and characteristics the medical school seeks. Never tell what qualities and characteristics you possess; let readers draw these conclusions on their own based on what you write.

Medical School Personal Statement Examples and Analysis for Inspiration

Below are examples of actual medical school personal statements. You can also likely find medical school personal statements on Reddit.

AMCAS Medical School Personal Statement Example and Analysis #1 with Personal Inventory

We will use Amy to illustrate the general process of writing an application to medical school, along with providing the resulting documents. Amy will first list those experiences, personal, extracurricular, and scholarly, that have been most influential in two areas: her life in general and her path to medical school. She will put this personal inventory in chronologic order for use in composing her personal statement.

She will then select those experiences that were the most significant to her and will reflect and think about why they were important. For her application entries, Amy will write about each experience, including those that she considers influential in her life but not in her choice of medicine, in her application entries. Experiences that Amy will not write about in her activity entries or her personal statement are those that she does not consider most influential in either her life or in her choice of medicine.

Amy’s personal inventory (from oldest to most recent)

- Going with my mom to work. She is a surgeon — I was very curious about what she did. I was intrigued by the relationships she had with patients and how much they valued her efforts. I also loved seeing her as “a doctor” since, to me, she was just “mom.”

- I loved biology in high school. I started to think seriously about medicine then. It was during high school that I became fascinated with biology and how the human body worked. I would say that was when I thought, “Hmm, maybe I should be a doctor.”

- Grandmother’s death, senior year of high school. My grandmother’s death was tragic. It was the first time I had ever seen someone close to me suffer. It was one of the most devastating experiences in my life.

- Global Health Trip to Guatemala my freshman year of college. I realized after going to Guatemala that I had always taken my access to health care for granted. Here I saw children who didn’t have basic health care. This made me want to become a physician so I could give more to people like those I met in Guatemala.

- Sorority involvement. Even though sorority life might seem trivial, I loved it. I learned to work with different types of people and gained some really valuable leadership experience.

- Poor grades in college science classes. I still regret that I did badly in my science classes. I think I was immature and was also too involved in other activities and didn’t have the focus I needed to do well. I had a 3.4 undergraduate GPA.

- Teaching and tutoring Jose, a child from Honduras. In a way, meeting Jose in a college tutoring program brought my Guatemala experience to my home. Jose struggled academically, and his parents were immigrants and spoke only Spanish, so they had their own challenges. I tried to help Jose as much as I could. I saw that because he lacked resources, he was at a tremendous disadvantage.

- Volunteering at Excellent Medical Center. Shadowing physicians at the medical center gave me a really broad view of medicine. I learned about different specialties, met many different patients, and saw both great and not-so-great physician role models. Counselor at Ronald McDonald House. Working with sick kids made me appreciate my health. I tried to make them happy and was so impressed with their resilience. It made me realize that good health is everything.

- Oncology research. Understanding what happens behind the scenes in research was fascinating. Not only did I gain some valuable research experience, but I learned how research is done.

- Peer health counselor. Communicating with my peers about really important medical tests gave me an idea of the tremendous responsibility that doctors have. I also learned that it is important to be sensitive, to listen, and to be open-minded when working with others.

- Clinical Summer Program. This gave me an entirely new view of medicine. I worked with the forensics department, and visiting scenes of deaths was entirely new to me. This experience added a completely new dimension to my understanding of medicine and how illness and death affect loved ones.

- Emergency department internship. Here I learned so much about how things worked in the hospital. I realized how important it was that people who worked in the clinical department were involved in creating hospital policies. This made me understand, in practical terms, how an MPH would give me the foundation to make even more change in the future.

- Master’s in public health. I decided to get an MPH for two reasons. First of all, I knew my undergraduate science GPA was an issue so I figured that graduate level courses in which I performed well would boost my record. I don’t think I will write this on my application, but I also thought the degree would give me other skills if I didn’t get into medical school, and I knew it would also give me something on which I could build during medical school and in my career since I was interested in policy work.

As you can see from Amy’s personal inventory list, she has many accomplishments that are important to her and influenced her path. The most influential personal experience that motivated her to practice medicine was her mother’s career as a practicing physician, but Amy was also motivated by watching her mother’s career evolve. Even though the death of her grandmother was devastating for Amy, she did not consider this experience especially influential in her choice to attend medical school so she didn’t write about it in her personal statement.

Amy wrote an experience-based personal statement, rich with anecdotes and detailed descriptions, to illustrate the evolution of her interest in medicine and how this motivated her to also earn a master’s in public health.

Amy’s Medical School Personal Statement Example:

She was sprawled across the floor of her apartment. Scattered trash, decaying food, alcohol bottles, medication vials, and cigarette butts covered the floor. I had just graduated from college, and this was my first day on rotation with the forensic pathology department as a Summer Scholar, one of my most valuable activities on the path to medical school. As the coroner deputy scanned the scene for clues to what caused this woman’s death, I saw her distraught husband. I did not know what to say other than “I am so sorry.” I listened intently as he repeated the same stories about his wife and his dismay that he never got to say goodbye. The next day, alongside the coroner as he performed the autopsy, I could not stop thinking about the grieving man.

Discerning a cause of death was not something I had previously associated with the practice of medicine. As a child, I often spent Saturday mornings with my mother, a surgeon, as she rounded on patients. I witnessed the results of her actions, as she provided her patients a renewed chance at life. I grew to honor and respect my mother’s profession. Witnessing the immense gratitude of her patients and their families, I quickly came to admire the impact she was able to make in the lives of her patients and their loved ones.

I knew I wanted to pursue a career in medicine as my mother had, and throughout high school and college I sought out clinical, research, and volunteer opportunities to gain a deeper understanding of medicine. After volunteering with cancer survivors at Camp Ronald McDonald, I was inspired to further understand this disease. Through my oncology research, I learned about therapeutic processes for treatment development. Further, following my experience administering HIV tests, I completed research on point-of-care HIV testing, to be instituted throughout 26 hospitals and clinics. I realized that research often served as a basis for change in policy and medical practice and sought out opportunities to learn more about both.

All of my medically related experiences demonstrated that people who were ‘behind the scenes’ and had limited or no clinical background made many of the decisions in health care. Witnessing the evolution of my mother’s career further underscored the impact of policy change on the practice of medicine. In particular, the limits legislation imposed on the care she could provide influenced my perspective and future goals. Patients whom my mother had successfully treated for more than a decade, and with whom she had long-standing, trusting relationships, were no longer able to see her, because of policy coverage changes. Some patients, frustrated by these limitations, simply stopped seeking the care they needed. As a senior in college, I wanted to understand how policy transformations came about and gain the tools I would need to help effect administrative and policy changes in the future as a physician. It was with this goal in mind that I decided to complete a master’s in public health program before applying to medical school.

As an MPH candidate, I am gaining insight into the theories and practices behind the complex interconnections of the healthcare system; I am learning about economics, operations, management, ethics, policy, finance, and technology and how these entities converge to impact delivery of care. A holistic understanding of this diverse, highly competitive, market-driven system will allow me, as a clinician, to find solutions to policy, public health, and administration issues. I believe that change can be more effective if those who actually practice medicine also decide where improvements need to be made.

For example, as the sole intern for the emergency department at County Medical Center, I worked to increase efficiency in the ED by evaluating and mapping patient flow. I tracked patients from point of entry to point of discharge and found that the discharge process took up nearly 35% of patients’ time. By analyzing the reasons for this situation, in collaboration with nurses and physicians who worked in the ED and had an intimate understanding of what took place in the clinical area, I was able to make practical recommendations to decrease throughput time. The medical center has already implemented these suggestions, resulting in decreased length of stays. This example illustrates the benefit of having clinicians who work ‘behind the scenes’ establish policies and procedures, impacting operational change and improving patient care. I will also apply what I have learned through this project as the business development intern at Another Local Medical Center this summer, where I will assist in strategic planning, financial analysis, and program reviews for various clinical departments.

Through my mother’s career and my own medical experiences, I have become aware of the need for clinician administrators and policymakers. My primary goal as a physician will be to care for patients, but with the knowledge and experience I have gained through my MPH, I also hope to effect positive public policy and administrative changes.

What’s Good About Amy’s Medical School Personal Statement:

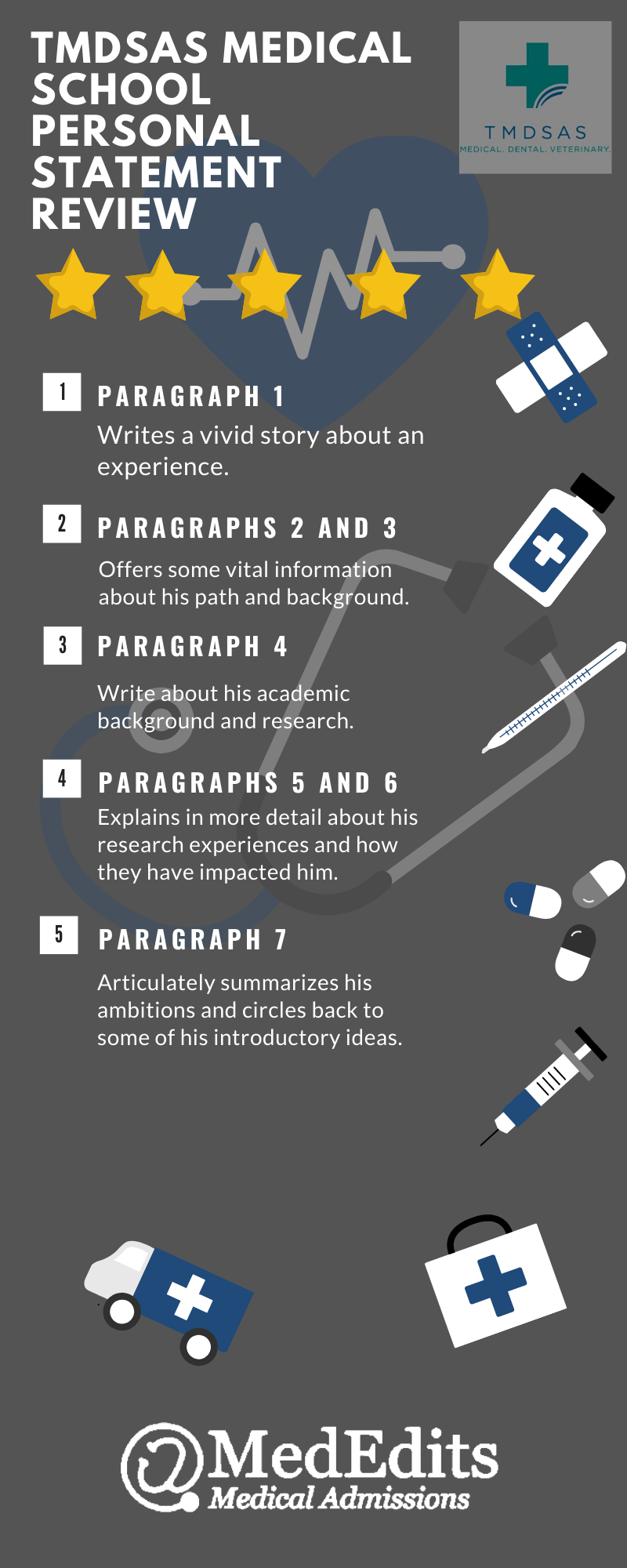

Paragraphs 1 and 2: Amy started her personal statement by illustrating a powerful experience she had when she realized that medical caregivers often feel impotent, and how this contrasted with her understanding of medicine as a little girl going with her mother to work. Recognition of this intense contrast also highlights Amy’s maturity.

Paragraph 3: Amy then “lists” a few experiences that were important to her.

Paragraph 4: Amy describes the commonality in some of her experiences and how her observations were substantiated by watching the evolution of her mother’s practice. She then explains how this motivated her to earn an MPH so she could create change more effectively as a physician than as a layman.

Paragraph 5: Amy then explains how her graduate degree is helping her to better understand the “issues in medicine” that she observed.

Paragraph 6: Amy then describes one exceptional accomplishment she had that highlights what she has learned and how she has applied it.

Paragraph 7: Finally, Amy effectively concludes her personal statement and summarizes the major topics addressed in her essay.

As you can see, Amy’s statement has excellent flow, is captivating and unusual, and illustrates her understanding of, and commitment to, medicine. She also exhibits, throughout her application entries and statement, the personal competencies, characteristics, and qualities that medical school admissions officers are seeking. Her application also has broad appeal; reviewers who are focused on research, cultural awareness, working with the underserved, health administration and policy, teaching, or clinical medicine would all find it of interest.

med school personal statement examples

Osteopathic Medical School Personal Statement Example and Analysis #2

Medical School Personal Statement Example Background: This is a nontraditional applicant who applied to osteopathic medical schools. With a 500 and a 504 on the MCAT , he needed to showcase how his former career and what he learned through his work made him an asset. He also needed to convey why osteopathic medicine was an ideal fit for him. The student does an excellent job illustrating his commitment to medicine and explaining why and how he made the well-informed decision to leave his former career to pursue a career in osteopathic medicine.

What’s Good About It: A nontraditional student with a former career, this applicant does a great job outlining how and why he decided to pursue a career in medicine. Clearly dedicated to service, he also does a great job making it clear he is a good fit for osteopathic medical school and understands this distinctions of osteopathic practice..

Working as a police officer, one comes to expect the unexpected, but sometimes, when the unexpected happens, one can’t help but be surprised. In November 20XX, I had been a police officer for two years when my partner and I happened to be nearby when a man had a cardiac emergency in Einstein Bagels. Entering the restaurant, I was caught off guard by the lifeless figure on the floor, surrounded by spilled food. Time paused as my partner and I began performing CPR, and my heart raced as I watched color return to the man’s pale face.

Luckily, paramedics arrived within minutes to transport him to a local hospital. Later, I watched as the family thanked the doctors who gave their loved one a renewed chance at life. That day, in the “unexpected,” I confirmed that I wanted to become a physician, something that had attracted me since childhood.

I have always been enthralled by the science of medicine and eager to help those in need but, due to life events, my path to achieving this dream has been long. My journey began following high school when I joined the U.S. Army. I was immature and needed structure, and I knew the military was an opportunity to pursue my medical ambitions. I trained as a combat medic and requested work in an emergency room of an army hospital. At the hospital, I started IVs, ran EKGs, collected vital signs, and assisted with codes. I loved every minute as I was directly involved in patient care and observed physicians methodically investigating their patients’ signs and symptoms until they reached a diagnosis. Even when dealing with difficult patients, the physicians I worked with maintained composure, showing patience and understanding while educating patients about their diseases. I observed physicians not only as clinicians but also as teachers. As a medic, I learned that I loved working with patients and being part of the healthcare team, and I gained an understanding of acute care and hospital operations.

Following my discharge in 20XX, I transferred to an army reserve hospital and continued as a combat medic until 20XX. Working as a medic at several hospitals and clinics in the area, I was exposed to osteopathic medicine and the whole body approach to patient care. I was influenced by the D.O.s’ hands-on treatment and their use of manipulative medicine as a form of therapy. I learned that the body cannot function properly if there is dysfunction in the musculoskeletal system.

In 20XX, I became a police officer to support myself as I finished my undergraduate degree and premed courses. While working the streets, I continued my patient care experiences by being the first to care for victims of gunshot wounds, stab wounds, car accidents, and other medical emergencies. In addition, I investigated many unknown causes of death with the medical examiner’s office. I often found signs of drug and alcohol abuse and learned the dangers and power of addiction. In 20XX, I finished my undergraduate degree in education and in 20XX, I completed my premed courses.

Wanting to learn more about primary care medicine, in 20XX I volunteered at a community health clinic that treats underserved populations. Shadowing a family physician, I learned about the physical exam as I looked into ears and listened to the hearts and lungs of patients with her guidance. I paid close attention as she expressed the need for more PCPs and the important roles they play in preventing disease and reducing ER visits by treating and educating patients early in the disease process. This was evident as numerous patients were treated for high cholesterol, elevated blood pressure, and diabetes, all conditions that can be resolved or improved by lifestyle changes. I learned that these changes are not always easy for many in underserved populations as healthier food is often more expensive and sometimes money for prescriptions is not available. This experience opened my eyes to the challenges of being a physician in an underserved area.

The idea of disease prevention stayed with me as I thought about the man who needed CPR. Could early detection and education about heart disease have prevented his “unexpected” cardiac event? My experiences in health care and law enforcement have confirmed my desire to be an osteopathic physician and to treat the patients of the local area. I want to eliminate as many medical surprises as I can.

Texas Medical School Personal Statement Example and Analysis #3

Medical School Personal Statement Example Background: This applicant, who grew up with modest means, should be an inspiration to us all. Rather than allowing limited resources to stand in his way, he took advantage of everything that was available to him. He commuted to college from home and had a part-time job so he was stretched thin, and his initial college performance suffered. However, he worked hard and his grades improved. Most medical school admissions committees seek out applicants like this because, by overcoming adversity and succeeding with limited resources, they demonstrate exceptional perseverance, maturity, and dedication. His accomplishments are, by themselves, impressive and he does an outstanding job of detailing his path, challenges, and commitment to medicine. He received multiple acceptances to top medical schools and was offered scholarships.

What’s Good About It: This student does a great job opening his personal statement with a beautifully written introduction that immediately takes the reader to Central America. He then explains his path, why he did poorly early in college, and goes on to discuss his academic interests and pursuits. He is also clearly invested in research and articulates that he is intellectually curious, motivated, hard working, compassionate and committed to a career in medicine by explaining his experiences using interesting language and details. This is an intriguing statement that makes clear the applicant is worthy of an interview invitation. Finally, the student expresses his interest in attending medical school in Texas.

They were learning the basics of carpentry and agriculture. The air was muggy and hot, but these young boys seemed unaffected, though I and my fellow college students sweated and often complained. As time passed, I started to have a greater appreciation for the challenges these boys faced. These orphans, whom I met and trained in rural Central America as a member of The Project, had little. They dreamed of using these basic skills to earn a living wage. Abandoned by their families, they knew this was their only opportunity to re-enter society as self- sufficient individuals. I stood by them in the fields and tutored them after class. And while I tried my best to instill in them a strong work ethic, it was the boys who instilled in me a desire to help those in need. They gave me a new perspective on my decision to become a doctor.

I don’t know exactly when I decided to become a physician; I have had this goal for a long time. I grew up in the inner city of A City, in Texas and attended magnet schools. My family knew little about higher education, and I learned to seek out my own opportunities and advice. I attended The University with the goal of gaining admission to medical school. When I started college, I lacked the maturity to focus on academics and performed poorly. Then I traveled to Central America. Since I was one of the few students who spoke Spanish, many of the boys felt comfortable talking with me. They saw me as a role model.

The boys worked hard so that they could learn trades that would help them to be productive members of society. It was then I realized that my grandparents, who immigrated to the US so I would have access to greater opportunities, had done the same. I felt like I was wasting what they had sacrificed for me. When I returned to University in the fall, I made academics my priority and committed myself to learn more about medicine .

Through my major in neuroscience, I strengthened my understanding of how we perceive and experience life. In systems neurobiology, I learned the physiology of the nervous system. Teaching everything from basic neural circuits to complex sensory pathways, Professor X provided me with the knowledge necessary to conduct research in Parkinson’s disease. My research focused on the ability of antioxidants to prevent the onset of Parkinson’s, and while my project was only a pilot study at the time, Professor X encouraged me to present it at the National Research Conference. During my senior year, I developed the study into a formal research project, recruiting the help of professors of statistics and biochemistry.

Working at the School of Medicine reinforced my analytical skills. I spent my summer in the department of emergency medicine, working with the department chair, Dr. Excellent. Through Dr. Excellent’s mentorship, I participated in a retrospective study analyzing patient charts to determine the efficacy of D-dimer assays in predicting blood clots. The direct clinical relevance of my research strengthened my commitment and motivated my decision to seek out more clinical research opportunities.

A growing awareness of the role of human compassion in healing has also influenced my choice to pursue a career in medicine. It is something no animal model or cell culture can ever duplicate or rival. Working in clinical research has allowed me to see the selflessness of many physicians and patients and their mutual desire to help others. As a research study assistant in the department of surgery, I educate and enroll patients in clinical trials. One such study examines the role of pre-operative substance administration in tumor progression. Patients enrolled in this study underwent six weeks of therapy before having the affected organ surgically excised. Observing how patients were willing to participate in this research to benefit others helped me understand the resiliency of the human spirit.

Working in clinical trials has enabled me to further explore my passion for science, while helping others. Through my undergraduate coursework and participation in volunteer groups I have had many opportunities to solidify my goal to become a physician. As I am working, I sometimes think about my second summer in Central America. I recall how one day, after I had turned countless rows of soil in scorching heat, one of the boys told me that I was a trabajador verdadero—a true worker. I paused as I realized the significance of this comment. While the boy may not have been able to articulate it, he knew I could identify with him. What the boy didn’t know, however, was that had my grandparents not decided to immigrate to the US, I would not have the great privilege of seizing opportunities in this country and writing this essay today. I look forward to the next step of my education and hope to return home to Texas where I look forward to serving the communities I call home.

Final Thoughts

Above all, and as stated in this article numerous times, your personal statement should be authentic and genuine. Write about your path and and journey to this point in your life using anecdotes and observations to intrigue the reader and illustrate what is and was important to you. Good luck!

Medical School Personal Statement Help & Consulting

If all this information has you staring at your screen like a deer in the headlights, you’re not alone. Writing a superb medical school personal statement can be a daunting task, and many applicants find it difficult to get started writing, or to express everything they want to say succinctly. That’s where MedEdits can help. You don’t have to have the best writing skills to compose a stand-out statement. From personal-statement editing alone to comprehensive packages for all your medical school application needs, we offer extensive support and expertise developed from working with thousands of successful medical school applicants. We can’t promise applying to medical school will be stress-free, but most clients tell us it’s a huge relief not to have to go it alone.

MedEdits offers personal statement consulting and editing. Our goal when working with students is to draw out what makes each student distinctive. How do we do this? We will explore your background and upbringing, interests and ideals as well as your accomplishments and activities. By helping you identify the most distinguishing aspects of who you are, you will then be able to compose an authentic and genuine personal statement in your own voice to capture the admissions committee’s attention so you are invited for a medical school interview. Our unique brainstorming methodology has helped hundreds of aspiring premeds gain acceptance to medical school.

Sample Medical School Personal Statement

Example Medical School Personal Statement

- Website Disclaimer

- Terms and Conditions

- MedEdits Privacy Policy

- Medical School Application

Medical School Personal Statement Examples That Got 6 Acceptances

Featured Admissions Expert: Dr. Monica Taneja, MD

These 30 exemplary medical school personal statement examples come from our students who enrolled in one of our application review programs. Most of these examples led to multiple acceptance for our students. For instance, the first example got our student accepted into SIX medical schools. Here's what you'll find in this article: We'll first go over 30 medical school personal statement samples, then we'll provide you a step-by-step guide for composing your own outstanding statement from scratch. If you follow this strategy, you're going to have a stellar statement whether you apply to the most competitive or the easiest medical schools to get into .

>> Want us to help you get accepted? Schedule a free strategy call here . <<

Listen to the blog!

Article Contents 36 min read

Stellar medical school personal statement examples that got multiple acceptances, medical school personal statement example #1.

I made my way to Hillary’s house after hearing about her alcoholic father’s incarceration. Seeing her tearfulness and at a loss for words, I took her hand and held it, hoping to make things more bearable. She squeezed back gently in reply, “thank you.” My silent gesture seemed to confer a soundless message of comfort, encouragement and support.

Through mentoring, I have developed meaningful relationships with individuals of all ages, including seven-year-old Hillary. Many of my mentees come from disadvantaged backgrounds; working with them has challenged me to become more understanding and compassionate. Although Hillary was not able to control her father’s alcoholism and I had no immediate solution to her problems, I felt truly fortunate to be able to comfort her with my presence. Though not always tangible, my small victories, such as the support I offered Hillary, hold great personal meaning. Similarly, medicine encompasses more than an understanding of tangible entities such as the science of disease and treatment—to be an excellent physician requires empathy, dedication, curiosity and love of problem solving. These are skills I have developed through my experiences both teaching and shadowing inspiring physicians.

Medicine encompasses more than hard science. My experience as a teaching assistant nurtured my passion for medicine; I found that helping students required more than knowledge of organic chemistry. Rather, I was only able to address their difficulties when I sought out their underlying fears and feelings. One student, Azra, struggled despite regularly attending office hours. She approached me, asking for help. As we worked together, I noticed that her frustration stemmed from how intimidated she was by problems. I helped her by listening to her as a fellow student and normalizing her struggles. “I remember doing badly on my first organic chem test, despite studying really hard,” I said to Azra while working on a problem. “Really? You’re a TA, shouldn’t you be perfect?” I looked up and explained that I had improved my grades through hard work. I could tell she instantly felt more hopeful, she said, “If you could do it, then I can too!” When she passed, receiving a B+;I felt as if I had passed too. That B+ meant so much: it was a tangible result of Azra’s hard work, but it was also symbol of our dedication to one another and the bond we forged working together.

My passion for teaching others and sharing knowledge emanates from my curiosity and love for learning. My shadowing experiences in particular have stimulated my curiosity and desire to learn more about the world around me. How does platelet rich plasma stimulate tissue growth? How does diabetes affect the proximal convoluted tubule? My questions never stopped. I wanted to know everything and it felt very satisfying to apply my knowledge to clinical problems.

Shadowing physicians further taught me that medicine not only fuels my curiosity; it also challenges my problem solving skills. I enjoy the connections found in medicine, how things learned in one area can aid in coming up with a solution in another. For instance, while shadowing Dr. Steel I was asked, “What causes varicose veins and what are the complications?” I thought to myself, what could it be? I knew that veins have valves and thought back to my shadowing experience with Dr. Smith in the operating room. She had amputated a patient’s foot due to ulcers obstructing the venous circulation. I replied, “veins have valves and valve problems could lead to ulcers.” Dr. Steel smiled, “you’re right, but it doesn’t end there!” Medicine is not disconnected; it is not about interventional cardiology or orthopedic surgery. In fact, medicine is intertwined and collaborative. The ability to gather knowledge from many specialties and put seemingly distinct concepts together to form a coherent picture truly attracts me to medicine.

It is hard to separate science from medicine; in fact, medicine is science. However, medicine is also about people—their feelings, struggles and concerns. Humans are not pre-programmed robots that all face the same problems. Humans deserve sensitive and understanding physicians. Humans deserve doctors who are infinitely curious, constantly questioning new advents in medicine. They deserve someone who loves the challenge of problem solving and coming up with innovative individualized solutions. I want to be that physician. I want to be able to approach each case as a unique entity and incorporate my strengths into providing personalized care for my patients. Until that time, I may be found Friday mornings in the operating room, peering over shoulders, dreaming about the day I get to hold the drill.

Let's take a step back to consider what this medical school personal statement example does, not just what it says. It begins with an engaging hook in the first paragraph and ends with a compelling conclusion. The introduction draws you in, making the essay almost impossible to put down, while the conclusion paints a picture of someone who is both passionate and dedicated to the profession. In between the introduction and conclusion, this student makes excellent use of personal narrative. The anecdotes chosen demonstrate this individual's response to the common question, " Why do you want to be a doctor ?" while simultaneously making them come across as compassionate, curious, and reflective. The essay articulates a number of key qualities and competencies, which go far beyond the common trope, I want to be a doctor because I want to help people.

This person is clearly a talented writer, but this was the result of several rounds of edits with one of our medical school admissions consulting team members and a lot of hard work on the student's part. If your essay is not quite there yet, or if you're just getting started, don't sweat it. Do take note that writing a good personal essay takes advanced planning and significant effort.

I was one of those kids who always wanted to be doctor. I didn’t understand the responsibilities and heartbreaks, the difficult decisions, and the years of study and training that go with the title, but I did understand that the person in the white coat stood for knowledge, professionalism, and compassion. As a child, visits to the pediatrician were important events. I’d attend to my hair and clothes, and travel to the appointment in anticipation. I loved the interaction with my doctor. I loved that whoever I was in the larger world, I could enter the safe space of the doctor’s office, and for a moment my concerns were heard and evaluated. I listened as my mother communicated with the doctor. I’d be asked questions, respectfully examined, treatments and options would be weighed, and we would be on our way. My mother had been supported in her efforts to raise a well child, and I’d had a meaningful interaction with an adult who cared for my body and development. I understood medicine as an act of service, which aligned with my values, and became a dream.

I was hospitalized for several months as a teenager and was inspired by the experience, despite the illness. In the time of diagnosis, treatment and recovery, I met truly sick children. Children who were much more ill than me. Children who wouldn’t recover. We shared a four-bed room, and we shared our medical stories. Because of the old hospital building, there was little privacy in our room, and we couldn’t help but listen-in during rounds, learning the medical details, becoming “experts” in our four distinct cases. I had more mobility than some of the patients, and when the medical team and family members were unavailable, I’d run simple errands for my roommates, liaise informally with staff, and attend to needs. To bring physical relief, a cold compress, a warmed blanket, a message to a nurse, filled me with such an intense joy and sense of purpose that I applied for a volunteer position at the hospital even before my release.

I have since been volunteering in emergency departments, out-patient clinics, and long term care facilities. While the depth of human suffering is at times shocking and the iterations of illness astounding, it is in the long-term care facility that I had the most meaningful experiences by virtue of my responsibilities and the nature of the patients’ illnesses. Charles was 55 when he died. He had early onset Parkinson’s Disease with dementia that revealed itself with a small tremor when he was in his late twenties. Charles had a wife and three daughters who visited regularly, but whom he didn’t often remember. Over four years as a volunteer, my role with the family was to fill in the spaces left by Charles’ periodic inability to project his voice as well as his growing cognitive lapses. I would tell the family of his activities between their visits, and I would remind him of their visits and their news. This was a hard experience for me. I watched as 3 daughters, around my own age, incrementally lost their father. I became angry, and then I grew even more determined.

In the summer of third year of my Health Sciences degree, I was chosen to participate in an undergraduate research fellowship in biomedical research at my university. As part of this experience, I worked alongside graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, medical students, physicians, and faculty in Alzheimer’s research into biomarkers that might predict future disease. We collaborated in teams, and by way of the principal investigator’s careful leadership, I learned wherever one falls in terms of rank, each contribution is vital to the outcome. None of the work is in isolation. For instance, I was closely mentored by Will, a graduate student who had been in my role the previous summer. He, in turn, collaborated with post docs and medical students, turning to faculty when roadblocks were met. While one person’s knowledge and skill may be deeper than another’s, individual efforts make up the whole. Working in this team, aside from developing research skills, I realized that practicing medicine is not an individual pursuit, but a collaborative commitment to excellence in scholarship and leadership, which all begins with mentorship.

Building on this experience with teamwork in the lab, I participated in a global health initiative in Nepal for four months, where I worked alongside nurses, doctors, and translators. I worked in mobile rural health camps that offered tuberculosis care, monitored the health and development of babies and children under 5, and tended to minor injuries. We worked 11-hour days helping hundreds of people in the 3 days we spent in each location. Patients would already be in line before we woke each morning. I spent each day recording basic demographic information, blood pressure, pulse, temperature, weight, height, as well as random blood sugar levels, for each patient, before they lined up to see a doctor. Each day was exhausting and satisfying. We helped so many people. But this satisfaction was quickly displaced by a developing understanding of issues in health equity.

My desire to be doctor as a young person was not misguided, but simply naïve. I’ve since learned the role of empathy and compassion through my experiences as a patient and volunteer. I’ve broadened my contextual understanding of medicine in the lab and in Nepal. My purpose hasn’t changed, but what has developed is my understanding that to be a physician is to help people live healthy, dignified lives by practicing both medicine and social justice.

28 More Medical School Personal Statement Examples That Got Accepted

What my sister went through pushed me to strengthen my knowledge in medical education, patient care, and research. These events have influenced who I am today and helped me determine my own passions. I aspire to be a doctor because I want to make miracles, like my sister, happen. Life is something to cherish; it would not be the same if I did not have one of my four sisters to spend it with. As all stories have endings, I hope that mine ends with me fulfilling my dream of being a doctor, which has been the sole focus of my life to this point. I would love nothing more than to dedicate myself to such a rewarding career, where I achieve what those doctors did for my family. Their expertise allowed my sister to get all the care she needed for her heart, eyes, lungs, and overall growth. Those physicians gave me more than just my little sister, they gave me the determination and focus needed to succeed in the medical field, and for that, I am forever grateful. ","label":"Medical School Personal Statement Example #3","title":"Medical School Personal Statement Example #3"}]" code="tab4" template="BlogArticle">

I came to America, leaving my parents and friends behind, to grasp my chance at a better future. I believe this chance is now in front of me. Medicine is the only path I truly desire because it satisfies my curiosity about the human body and it allows me to directly interact with patients. I do not want to miss this chance to further hone my skills and knowledge, in order to provide better care for my patients. ","label":"Medical School Personal Statement #4","title":"Medical School Personal Statement #4"}]" code="tab5" template="BlogArticle">

The time I have spent in various medical settings has confirmed my love for the field. Regardless of the environment, I am drawn to patients and their stories, like that scared young boy at AMC. I am aware that medicine is a constantly changing landscape; however, one thing that has remained steadfast over the years is putting the patient first, and I plan on doing this as a physician. All of my experiences have taught me a great deal about patient interaction and global health, however, I am left wanting more. I crave more knowledge to help patients and become more useful in the healthcare sector. I am certain medical school is the path that will help me reach my goal. One day, I hope to use my experiences to become an amazing doctor like the doctors that treated my sister, so I can help other children like her. ","label":"Medical School Personal Statement Example #5","title":"Medical School Personal Statement Example #5"}]" code="tab6" template="BlogArticle">

My interest in the field of medicine has developed overtime, with a common theme surrounding the importance of personal health and wellness. Through my journey in sports, travelling, and meeting some incredible individuals such as Michael, I have shifted my focus from thinking solely about the physical well-being, to understanding the importance of mental, spiritual, and social health as well. Being part of a profession that emphasizes continuous education, and application of knowledge to help people is very rewarding, and I will bring compassion, a hard work ethic and an attitude that is always focused on bettering patient outcomes. ","label":"Medical School Personal Statement Example # 7","title":"Medical School Personal Statement Example # 7"}]" code="tab8" template="BlogArticle">

Medicine embodies a hard science, but it is ultimately a profession that treats people. I have seen firsthand that medicine is not a \u201cone-treatment-fits-all\u201d practice, as an effective physician takes a holistic approach. This is the type of physician I aspire to be: one who refuses to shy away from the humanity of patients and their social context, and one who uses research and innovation to improve the human condition. So, when I rethink \u201cwhy medicine?\u201d, I know it\u2019s for me \u2013 because it is a holistic discipline, because it demands all of me, because I am ready to absorb the fascinating knowledge and science that dictates human life, and engage with humanity in a way no other profession allows for. Until the day that I dawn the coveted white coat, you can find me in inpatient units, comforting the many John\u2019s to come, or perhaps at the back of an operating room observing a mitral valve repair \u2013 dreaming of the day the puck is in my zone. ","label":"Medical School Personal Statement Example #8","title":"Medical School Personal Statement Example #8"}]" code="tab9" template="BlogArticle">

When I signed up to be a live DJ, I didn't know that the oral skills I practiced on-air would influence all aspects of my life, let alone lead me to consider a career in the art of healing. I see now, though, the importance of these key events in my life that have allowed me to develop excellent communication skills--whether that be empathic listening, reading and giving non-verbal cues, or verbal communication. I realize I have always been on a path towards medicine. Ultimately, I aim to continue to strengthen my skills as I establish my role as a medical student and leader: trusting my choices, effectively communicating, and taking action for people in need. ","label":"Medical School Personal Statement Example #9","title":"Medical School Personal Statement Example #9"}]" code="tab10" template="BlogArticle">

\u201cWhy didn\u2019t I pursue medicine sooner?\u201d Is the question that now occupies my mind. Leila made me aware of the unprofessional treatment delivered by some doctors. My subsequent activities confirmed my desire to become a doctor who cares deeply for his patients and provides the highest quality care. My passion for research fuels my scientific curiosity. I will continue to advocate for patient equality and fairness. Combining these qualities will allow me to succeed as a physician. ","label":"Medical School Personal Statement Example #10","title":"Medical School Personal Statement Example #10"}]" code="tab11" template="BlogArticle">

Medical school personal statement example: #11

Medical school personal statement example: #12, medical school personal statement example: #13, medical school personal statement example: #14, medical school personal statement example: #15, medical school personal statement example: #16, medical school personal statement example: #17, medical school personal statement example: #18, medical school personal statement example: #19, medical school personal statement example: #20, medical school personal statement example: #21, medical school personal statement example: #22, medical school personal statement example: #23, medical school personal statement example: #24, medical school personal statement example: #25, medical school personal statement example: #26, medical school personal statement example: #27, medical school personal statement example: #28, medical school personal statement example: #29, medical school personal statement example: #30.

Please note that all personal statements are the property of the students who wrote them, re-printed with permission. Names and identifying characteristics have been changed. Plagiarism detection software is used when evaluating personal statements. Plagiarism is grounds for disqualification from the application. ","label":"NOTE","title":"NOTE"}]" code="tab2" template="BlogArticle">

As one of the most important medical school requirements , the personal statement tells your story of why you decided to pursue the medical profession. Keep in mind that personal statements are one of the key factors that affect medical school acceptance rates . This is why it's important to write a stellar essay!

“Personal statements are often emphasized in your application to medical school as this singular crucial factor that distinguishes you from every other applicant. Demonstrating the uniqueness of my qualities is precisely how I found myself getting multiple interviews and offers into medical school.” – Dr. Vincent Adeyemi, MD, Emory University school of Medicine

But this is easier said than done. In fact, medical school personal statements remain one of the most challenging parts of students' journeys to medical school. Here's our student Melissa sharing her experience of working on her personal statement:

"I struggled making my personal statement personal... I couldn't incorporate my feelings, motives and life stories that inspired me to pursue medicine into my personal statement" -Melissa, BeMo Student

Our student Rishi, who is now a student at the Carver College of Medicine , learned about the importance of the medical school personal statement the hard way:

"If you're a reapplicant like me, you know we all dread it but you have to get ready to answer what has changed about your application that we should accept you this time. I had an existing personal statement that did not get me in the first time so there was definitely work to be done." - Rishi, BeMo Student, current student at the Carver College of Medicine

The importance of the medical school personal statement can actually increase if you are applying to medical school with any red flags or setbacks, as our student Kannan did:

"I got 511 on my second MCAT try... My goal was anything over median of 510 so anything over that was honestly good with me because it's just about [creating] a good personal statement at that point... I read online about how important the personal statement [is]... making sure [it's] really polished and so that's when I decided to get some professional help." - Kannan, BeMo Student, current student at the Schulich School of Medicine

As you can see from these testimonials, your medical school personal statement can really make a difference. So we are here to help you get started writing your own personal statement. Let's approach this step-by-step. Below you will see how we will outline the steps to creating your very best personal statement. And don't forget that if you need to see more examples, you can also check out our AMCAS personal statement examples, AACOMAS personal statement examples and TMDSAS personal statement examples to further inspire you!

Here's a quick run-down of what we'll cover in the article:

Now let's dive in deeper!

#1 Understanding the Qualities of a Strong Med School Personal Statement

Before discussing how to write a strong medical school personal statement, we first need to understand the qualities of a strong essay. Similar to crafting strong medical school secondary essays , writing a strong personal statement is a challenging, yet extremely important, part of your MD or MD-PhD programs applications. Your AMCAS Work and Activities section may show the reader what you have done, but the personal statement explains why. This is how Dr. Neel Mistry, MD and our admissions expert, prepared for his medical school personal statement writing: