An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Valuing Human Impact of Natural Disasters: A Review of Methods

Aditi kharb.

1 Institute of Health and Society (IRSS), Universite Catholique de Louvain, 1200 Brussels, Belgium

Sandesh Bhandari

2 Department of Medicine, University of Oviedo, 3204 Oviedo, Spain

Maria Moitinho de Almeida

Rafael castro delgado, pedro arcos gonzález, sandy tubeuf.

3 Institute of Economic and Social Research (IRES/LIDAM), Universite Catholique de Louvain, 1200 Brussels, Belgium

Associated Data

Not applicable.

This paper provides a comprehensive set of methodologies that have been used in the literature to give a monetary value to the human impact in a natural disaster setting. Four databases were searched for relevant published and gray literature documents with a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Twenty-seven studies that quantified the value of a statistical life in a disaster setting or discussed methodologies of estimating value of life were included. Analysis highlighted the complexity and variability of methods and estimations of values of statistical life. No single method to estimate the value of a statistical life is universally agreed upon, although stated preference methods seem to be the preferred approach. The value of one life varies significantly ranging from USD 143,000 to 15 million. While an overwhelming majority of studies concern high-income countries, most disaster casualties are observed in low- and middle-income countries. Data on the human impact of disasters are usually available in disasters databases. However, lost lives are not traditionally translated into monetary terms. Therefore, the full financial cost of disasters has rarely been evaluated. More research is needed to utilize the value of life estimates in order to guide policymakers in preparedness and mitigation policies.

1. Introduction

Since 1960, more than 11,000 disasters triggered by natural hazards have been recorded. The number has steadily increased from an annual total of 33 disasters in 1960 to a peak of 441 disasters in 2000 [ 1 ]. Hazards such as storms, floods, heatwaves, droughts and wildfires have increased in number, intensity and variability in recent years [ 2 ]. Between 2000 and 2019, there were 510,837 deaths and 3.9 billion people affected by 6681 natural disasters [ 3 ]. This rising death rate highlights the continued vulnerability of communities to natural hazards, especially in low- and middle-income countries. The Analysis of Emergency Events Database(EM-DAT) shows that, on average, more than three times as many people died per disaster in low-income countries than in high-income nations [ 1 ]. A similar pattern was evident when low- and lower-middle-income countries were grouped together and compared to high- and upper-middle-income countries. Taken together, higher-income countries experienced 56% of disasters but lost 32% of lives, while lower-income countries experienced 44% of disasters but suffered 68% of deaths [ 1 ].

Disasters datasets usually report the human impact of disasters fairly precisely, and also include the economic impact mainly related to damages to insured goods; for example, EM-DAT, NatCatservice, MunichRe [ 1 , 4 ]. While economic damages of disasters are available in monetary terms, the human impact is measured in different natural units (lost lives, lost life years, disability-adjusted life years (DALY), etc.). Transforming those human impacts into monetary terms is not straightforward. However, it is of great importance in disaster contexts, as it could serve as a vital tool for a multitude of purposes, not limited to informing policy decision making.

Reinsurance companies could utilize this value to generate risk assessments, calibrate loss-estimation models and validate compensation claims; investors and international organizations could make use of it to advise strategic risk mitigation plans; and academic institutions could use it to measure inequalities and identify research gaps. Additionally, for individuals, the perceived disaster severity and knowledge of disaster-related risks might be limited and can be supplemented by providing monetary value to the physical and psychological health risks they might face [ 5 ]. Similarly, as the principal focus of health, safety and environmental regulations and many public health-related policies is to enhance individual health, where the most consequential impacts often pertain to reductions in mortality risks, policymakers seeking to assess society’s willingness to pay for expected health improvements need some measures of the associated benefit values to monetize the risk reductions and to facilitate comparison of benefits and costs. In this context, evaluating the global impact of a disaster would rely on using a unique metric to translate both the human and the economic costs of disasters.

Providing a monetary value to lost lives or health losses relies on the value of statistical life literature. The economics and disaster literature today has shown that although it is difficult to ‘put a price on life’, observation of individual and group behaviors seem to indicate otherwise. People regularly weigh risks and make decisions through a cost–benefit analysis framework, where they weigh the willingness to pay for risk reduction and the marginal cost of enhancing safety [ 6 , 7 ]. According to Kniesner and Viscusi (2019) [ 8 ], the value of statistical life can be defined as the local trade-off rate between fatality risk and money. The utility associated with reducing a risk must compensate for the disutility associated with the cost of reducing that risk. This argument is further strengthened by the cost assessment of intangible effects of natural disasters in the literature in welfare economics [ 9 , 10 ]. Individuals derive welfare from non-market goods such as environmental and health assets in more ways than only direct consumption [ 11 ]. For example, does the cost of reinforcing and strengthening buildings in a seismically active zone and ensure earthquake resistance save enough lives and prevent enough injuries that, in the long run, individual productivity for the state overshoot the costs exhausted by the state [ 12 ]?

This review aims to provide an overview of the methodologies used to evaluate the value of life in a natural disaster context and to present the differences in values of statistical life calculated using these alternative methodologies. The review also highlights the areas in the literature where more research is needed. To this end, the first section of this review reports the methodology for the selection and analysis of the literature. The second section explains the results of the analysis. Finally, we discuss the results and shortcomings of the current literature and draw conclusions from the study.

2. Methodology

We conducted a review of the literature reporting on the value of life in disasters adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 13 ]. The research question was formulated with the collaboration of the co-authors and the search strategy was then developed following extensive discussion.

2.1. Search Strategy

Several databases were used to search for literature, including PubMed MeSH, EMBASE and ECONLIT. In addition to this, the search was also performed in SCOPUS and Google Scholar so as not to miss any relevant papers, but only the first 200 results sorted by relevance were picked up from the two latter databases. We then screened the references of included full texts to identify any potential misses from our initial search strategy.

Various keywords synonymous to the two concepts “Value of Life” and “Disasters” were identified to undertake the search for literature. For “Value of life”, words and phrases such as cost of life, value of statistical life, VSL, willingness to pay, value of life lost and economic value of life were identified as relevant. Similarly, for “Disasters”, two additional terms, i.e., natural disasters and hazards, were used. The two concepts were searched separately as one and two, and then the combination of one and two was searched to obtain the results. More details about the search strategy are available in Appendix A .

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The primary inclusion criteria for the search were peer-reviewed articles or gray literature such as conference papers, dissertation and discussion papers on disasters and value of life written in English from 2000 to 2020. We included studies that primarily quantified the value of life in a disaster setting and studies discussing methodology of estimating the value of life without providing a value by itself. No geographical limitations were set.

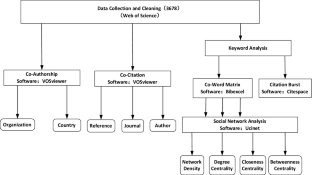

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The hits from different databases were exported onto Mendeley citation manager (Mendeley version 1.19.8) for subsequent screenings. Duplicates were excluded first. Titles and abstracts were then screened, and finally, full texts were screened for the papers included after abstract screening, excluding papers clearly outside the scope of this study. All uncertainties about eligibility were discussed between three co-authors (SB, MMA, ST) in all steps of the selection process.

Several papers were excluded in subsequent screening steps. Papers only talking about environmental pollution and climate change without a reference to natural disasters were excluded, as these topics are quite broad and, if not a cause for natural disasters, fall outside the scope of this study. Additionally, articles mainly concerned with terrorism, conflicts and landmines were not included in the final selection. Other categories of papers that were excluded were coal mine accidents, traffic accidents and forest fires. Papers solely talking about housing insurance and policy recommendations were also excluded. A total of five papers were requested directly from the authors as they could not be accessed online.

A data extraction form was developed for this review after consultation with the authors. The data extraction form recorded the descriptive aspect of all the studies included in the review, including methodology used to calculate the value of statistical life (VSL), results, strengths and limitations. This form was then pilot tested to ensure all the information was covered. The excluded studies were also tested against the form to check why they did not fit the form and revised as needed in subsequent steps. More details about the form are available in the Appendix A .

We first provided a descriptive overview of the included studies in terms of disaster types, the year in which studies were published, distribution of studies among countries according to the level of income as classified by the World Bank, simple geographical distribution and methodologies mentioned in the studies which were used to calculate the VSL. We then synthesized the information provided according to major predefined themes, such as methods of estimation of VSL, calculated VSL, and variations in VSL by geographical regions. These were identified before the analysis following discussions within the research team. Additionally, the possibility of emerging themes was considered and actively looked for during identification and processing of predefined themes.

3.1. Descriptive Overview of Included Studies

The initial search yielded a total of n = 2121 articles, coming down to n = 2084 after duplicates were removed. After screening titles and abstracts, n = 115 papers were considered for full text screening. Subsequently, a further n = 87 articles were excluded and two additional papers were excluded during the data extraction process. In addition to the remaining n = 26 papers for the review, one article was included from the reference screening, making the final count of papers for the review n = 27. The detailed process of article selection is presented in a PRISMA flow diagram ( Figure 1 ) [ 13 ].

PRISMA flow chart of search, inclusion and exclusion screening and accepted studies of the review. Source: Authors.

The biggest proportion of the included papers (n = 8, 29.6%) focused on value of life lost due to floods. This was closely followed by papers discussing unspecified disasters or disasters in general (n = 5, 18.5%). Five articles (18.5%) focused on earthquakes specifically, followed by three papers (11.1%) examining the value of life in the context of avalanches and rockfalls. Two articles (7.4%) discussed tornadoes and three papers (11.1%) dealt with a group of disasters consisting of four types of disasters, namely flood, drought, alpine and coastal hazards. One article (3.7%) was about heatwaves ( Figure 2 ).

Numbers of included studies by type of disaster. Source: Author.

Most studies (n = 16, 59%) concerned countries classified as high-income countries by the World Bank, including four papers (15%) from the United States of America (USA), three (11%) from the Netherlands and two each (7%) from Switzerland and Australia. Germany, Austria, Russia, Italy, New Zealand and Japan also had one article each in the final pool. Four studies (15%) were from upper-middle-income countries, including two studies from China and one each from Russia and Iran. Only one paper considered a lower-middle-income country, namely Vietnam. Four papers (15%) were not specific to any country and discussed the value of statistical life in general, without geographical consideration. Finally, one paper (3.7%) talked about developing countries in general while talking about value of life and reconstruction costs resulting from earthquakes.

Regarding where the articles were published, all but 4 out of 27 articles (85%) were published in peer-reviewed journals. As we included gray literature, two out of the four were discussion papers, one was a conference proceedings and the remaining one was a doctoral dissertation. The included studies were published in a variety of disaster-related, economics, policy and environmental journals.

3.2. Methods Used to Estimate Value of Life

A number of methods used to estimate the value of life were highlighted after reviewing the literature. Table 1 summarizes the different methods used in the included literature.

Value of statistical life estimation methods.

- (a) Revealed preference methods.

The revealed preference method utilizes observed behavior among the individuals that has already occurred and makes use of this to approximate suggested willingness to pay for a change in mortality risk. This method has an advantage over the stated preference approach in that if a person pays a certain amount for a commodity, it is known with conviction that the same person’s WTP for that commodity is at least the amount he/she is willing to pay. The four methods used to reveal preferences include: (a) the hedonic pricing method; (b) the travel cost method; (c) the cost of illness approach; (d) the replacement cost method [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

- (b) Stated preference methods.

In contrast with revealed preference methods, the stated preferences method creates a hypothetical market in a survey. It parallels a market survey and estimates a willingness to pay for hypothetical reduction in mortality risks, since it resembles market behavior. In addition, stated preference methods incorporate both active and passive use of a commodity by the consumer. Direct or active values arise when an individual physically experiences the commodity, while passive or indirect values entail that an individual does not directly experience the commodity. The three methods used for stated preferences include: (a) the contingent valuation method; (b) the choice modeling method; (c) life satisfaction analysis [ 17 , 18 , 19 ].

- (c) Non-behavioral methods

Non-behavioral methods are not necessarily based on human choices and cognitive biases which affect the choices subconsciously. They include the human capital method (HCM) [ 20 ] and life quality index method (LQI) [ 21 ] to estimate the valuation of statistical life, and they are used to elicit the value of an individual in a society in the absence of a possibility to conduct a survey pre- or post- disaster.

In the selected literature, 7 papers out of 16 used stated preference methods. Within stated preference methods, two papers used choice modeling, while the other five used a contingent valuation method.

Papers using choice modeling method included Bockarjova et al. (2012) [ 22 ] and Rheinberger (2011) [ 23 ]. While Bockarjova et al. (2012) [ 22 ] carried out a choice modeling experiment via an internet-based questionnaire and elicited responses from people living in flood prone areas in the Netherlands in two separate studies, Rheinberger (2011) [ 23 ] undertook a choice experiment by recruiting respondents via a phone call prior to a mail survey.

For contingent valuation method, Leiter et al. (2010) [ 24 ] used face-to-face interviews and elicited people’s willingness to pay to prevent an increase in the risk of dying in a snow avalanche. Similarly, Hoffmann et al. (2017) [ 26 ] used a computerized payment card method to estimate the willingness to pay to reduce mortality risk in Chinese population living in four different cities in China. In contrast, Ozdemir (2011) [ 25 ] used a contingent valuation method as well, but used a mail survey to elicit willingness to pay to reduce the risks from tornadoes in the USA.

For non-behavioral methods, Dassanayake et al. (2012) [ 35 ] used a quality of life index method to evaluate intangible flood losses and integrate them into a flood risk analysis.

Other papers used one or a combination of methods. For example, Porfiriev (2014) [ 31 ] approached the economic valuation of human losses resulting from natural and technological disasters in Russia using the theory of welfare and an international comparative approach. Cropper and Sahin (2009) [ 12 ] used the comparative approach, along with transferring the VSL from USA to a whole list of countries classified by income groups by the OECD to estimate VSL.

3.3. Values Provided in the Literature

There was a wide range of VSL values in the literature, ranging from ISD 143,000 to 15 million for one life [ 12 , 25 ]. Table 2 summarizes the estimated value of statistical lives in the articles included in the review. Disaster types range from natural disasters to technological disasters with some disaster types appearing more often than others in the literature, with earthquakes and floods being the most common. The VSLs appeared to increase over the years: while it was estimated to be USD 0.81 million in 2005 in Switzerland in the context of avalanches [ 34 ], it was evaluated between USD 6.8 and 7.5 million in 2011 [ 23 ].

Estimated values of statistical life in included articles.

* Values were converted into United States Dollars (USD) in respective years. Source: Authors [ 37 ].

4. Discussion

Disasters are complex events, and the assessment of losses they have caused is a compounded task. This review’s exploration of literature estimating the value of statistical life with regard to disasters highlighted the complexity and variability of the estimation of values of statistical life and the methods involved.

The geographical locations of studies included in the review showed the parts of the world where most of the studies were focused. An overwhelming majority of studies estimated the value of statistical life in high-income countries. The main reasons for this are related to the data availability and the investment made by developed countries in research and development for the advancement of science in general [ 38 ]. Low- and middle-income countries often experience several disasters occurring year round, and become trapped in a loop of disaster recovery and management annually. Amid ever-present financial constraints, disaster risk reduction and management planning to deal with disasters and their impact in the country therefore becomes much more demanding [ 39 ].

The estimation of economic damages due to disaster in a low-resource setting can also be challenging. Not all the houses, agricultural land, crops and other assets are insured in low- and middle-income countries. The insurance coverage is relatively small if not non-existent in these countries [ 40 ] and the data to quantify the impacts of disasters, such as the number of deaths, missing, affected population as well as reconstruction costs, are often incomplete and not well recorded. So, the unavailability of appropriate information becomes a big challenge in the first step of conducting research. This might be the reason why low- and middle-income countries are not well represented in studies estimating the value of life in disasters. As a result, the lack of studies in low- and middle-income countries can lead to a certain degree of extrapolation of results found in VSL calculation in high-income-country-based studies.

Furthermore, we note that the majority of articles measuring the value of life were about floods. Floods are indeed the most common type of disasters. In an analysis of disasters recorded in the EM-DAT database from 2000 to 2019, nearly half (n = 3254) of all recorded events (n = 7348) were floods [ 41 ]. However, there are many other types of disasters, and it is important to rely on such studies where those disasters were considered when measuring the value of a statistical life.

Methods used for VSL estimations showed significant diversity among the articles included in this review. Although the stated preferences method is the most frequent, it is closely followed by the adaptation method. There could be various reasons for this difference in methodologies across the literature. For instance, non-marketed good with no complementary or substitute market good may not have readily available individual data, and hence may lead the researchers to undertake stated preference methods with which to elicit people’s willingness to pay to reduce a hypothetical disaster risk through surveys [ 19 ]. The scope of the study and the budgetary constraints may also explain why a researcher chooses one method over the other. Additionally, the characteristics of the survey participants are another important factor, as they influence the type of survey that can be conducted and the methodology adopted. For example, if the target population is old and poor, face-to-face interviews in respondents’ private homes might be more suitable than internet-based questionnaires [ 42 , 43 ].

There was a wide range of monetary values of the VSL in the literature. These differences could be due to the level of income of the country where the disaster occurred [ 40 ]. The method of calculation could be another reason for such differences, for example, as consumers optimize their lifetime utility, thus neglecting intergenerational (long-term) utility, using willingness to pay (WTP) methods for a reduction of risk can often lead to overestimated values [ 44 , 45 ]. It could also simply be due to the differences in cultural norms between countries [ 40 ]. Furthermore, the context and the aim of the research and its evolution over the years might also explain variations across the studies. Further studies are required to establish a concrete cause for this observation. It should also be highlighted that low VSL estimates in low-income countries do not inherently mean that a human life is worth less. It could simply reflect individual income, the cost of commodities and the value of currency [ 8 , 46 ].

This study presents a number of limitations. First, the review only included articles published in English, and some studies may exist in other languages. Second, papers that did estimate a VSL considered a range of different methods, and therefore direct comparison of estimated values was not straightforward. Papers referring to economic impact in terms of natural environment or animals were also excluded, as they do not refer to value of statistical life; however, they can be important for calculating overall economic cost of disasters [ 47 , 48 ].

5. Conclusions

This study aims to explore literature estimating the value of statistical life with regard to disasters through a systematic review. After applying the inclusion criteria on the 2121 articles found in the initial keywords search, only 27 articles were included for final review. In the included literature, several attempts at estimating the value of statistical lives in disasters were identified; however, there was no consensus on the method used, and few investigations were carried out in a low- and middle-income country context. This review therefore provides a limited view of the value of statistical life calculations in disaster settings, which may become useful when implementing disaster risk reduction policies and calculating global losses incurred due to disasters. It reveals that an agreed, robust and multi-sectoral approach for the disaster and economics community remains to be defined.

Appendix A. Search Strategy Description

For PubMed MeSH, terms such as sanctity of life, life sanctity, life sanctities, respect for life, economic life valuation, life valuation/s, economic valuation/s and economic life were used. In addition to this, the search was performed in SCOPUS and GOOGLE SCHOLAR.

The data extraction form recorded the descriptive aspect of all the studies included in the review, the including methodology used to calculate VSL, results, strengths and limitations. A total of 16 categories of information were extracted:

(1) Author, (2) Title, (3) Year published, (4) Journal, (5) Study location, (6) Aim of the study, (7) Disaster type, (8) Type of study (Theoretical/Empirical), (9) Study data source, (10) Study participants, (11) Method of VSL estimation, (12) VSL if given, (13) Strengths, (14) Limitations, (15) Relevant references and (16) Study design.

Funding Statement

We are grateful to the European Commission for providing the Erasmus Mundus Grant for completing the Erasmus Mundus Master Course in Public Health in Disasters (EMPHID). We also thank USAID/DCHA/OFDA [ref no. 72OFDA20CA00072] for funding the research at Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters at the Universite catholique de Louvain.

Author Contributions

A.K.: Formal analysis, investigation, writing—review & editing; S.B.: Formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft; M.M.d.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing; R.C.D.: Funding acquisition, supervision, review & editing; P.A.G.: Funding acquisition, supervision, review & editing; S.T.: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Facing Hazards and Disasters: Understanding Human Dimensions (2006)

Chapter: 4 research on disaster response and recovery, 4 research on disaster response and recovery.

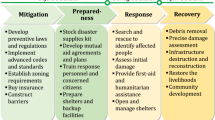

T his chapter and the preceding one use the conceptual model presented in Chapter 1 (see Figure 1.1 ) as a guide to understanding societal response to hazards and disasters. As specified in that model, Chapter 3 discusses three sets of pre-disaster activities that have the potential to reduce disaster losses: hazard mitigation practices, emergency preparedness practices, and pre-disaster planning for post-disaster recovery. This chapter focuses on National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program (NEHRP) contributions to social science knowledge concerning those dimensions of the model that are related to post-disaster response and recovery activities. As in Chapter 3 , discussions are organized around research findings regarding different units of analysis, including individuals, households, groups and organizations, social networks, and communities. The chapter also highlights trends, controversies, and issues that warrant further investigation. The contents of this chapter are linked to key themes discussed elsewhere in this report, including the conceptualization and measurement of societal vulnerability and resilience, the importance of taking diversity into account in understanding both response-related activities and recovery processes and outcomes, and linkages between hazard loss reduction and sustainability. Although this review centers primarily on research on natural disasters and to a lesser degree on technological disasters, research findings are also discussed in terms of their implications for understanding and managing emerging homeland security threats.

The discussions that follow seek to address several interrelated questions: What is currently known about post-disaster response and recovery,

and to what extent is that knowledge traceable to NEHRP-sponsored research activities? What gaps exist in that knowledge? What further research—both disciplinary and interdisciplinary—is needed to fill those gaps?

RESEARCH ON DISASTER RESPONSE

Emergency response encompasses a range of measures aimed at protecting life and property and coping with the social disruption that disasters produce. As noted in Chapter 3 , emergency response activities can be categorized usefully as expedient mitigation actions (e.g., clearing debris from channels when floods threaten, containing earthquake-induced fires and hazardous materials releases before they can cause additional harm) and population protection actions (e.g., warning, evacuation and other self-protective actions, search and rescue, the provision of emergency medical care and shelter; Tierney et al., 2001). Another common conceptual distinction in the literature on disaster response (Dynes et al., 1981) contrasts agent-generated demands , or the types of losses and forms of disruption that disasters create, and response-generated demands , such as the need for situation assessment, crisis communication and coordination, and response management. Paralleling preparedness measures, disaster response activities take place at various units of analysis, from individuals and households, to organizations, communities, and intergovernmental systems. This section does not attempt to deal exhaustively with the topic of emergency response activities, which is the most-studied of all phases of hazard and disaster management. Rather, it highlights key themes in the literature, with an emphasis on NEHRP-based findings that are especially relevant in light of newly recognized human-induced threats.

Public Response: Warning Response, Evacuation, and Other Self-Protective Actions

The decision processes and behaviors involved in public responses to disaster warnings are among the best-studied topics in the research literature. Over nearly three decades, NEHRP has been a major sponsor of this body of research. As noted in Chapter 3 , warning response research overlaps to some degree with more general risk communication research. For example, both literatures emphasize the importance of considering source, message, channel, and receiver effects on the warning process. While this discussion centers mainly on responses to official warning information, it should be noted that self-protective decision-making processes are also initiated in the absence of formal warnings—for example, in response to cues that people perceive as signaling impending danger and in disasters that occur without warning. Previous research suggests that the basic deci-

sion processes involved in self-protective action are similar across different types of disaster events, although the challenges posed and the problems that may develop can be agent specific.

As in other areas discussed here, empirical studies on warning response and self-protective behavior in different types of disasters and emergencies have led to the development of broadly generalizable explanatory models. One such model, the protective action decision model, developed by Perry, Lindell, and their colleagues (see, for example, Lindell and Perry, 2004), draws heavily on Turner and Killian’s (1987) emergent norm theory of collective behavior. According to that theory, groups faced with the potential need to act under conditions of uncertainty (or potential danger) engage in interaction in an attempt to develop a collective definition of the situation they face and a set of new norms that can guide their subsequent action. 1 Thus, when warnings and protective instructions are disseminated, those who receive warnings interact with one another in an effort to determine collectively whether the warning is authentic, whether it applies to them, whether they are indeed personally in danger, whether they can reduce their vulnerability through action, whether action is possible, and when they should act. These collective determinations are shaped in turn by such factors as (1) the characteristics of warning recipients , including their prior experience with the hazard in question or with similar emergencies, as well as their prior preparedness efforts; (2) situational factors , including the presence of perceptual cues signaling danger; and (3) the social contexts in which decisions are made—for example, contacts among family members, coworkers, neighborhood residents, or others present in the setting, as well as the strength of preexisting social ties. Through interaction and under the influence of these kinds of factors, individuals and groups develop new norms that serve as guidelines for action.

Conceptualizing warning response as a form of collective behavior that is guided by emergent norms brings several issues to the fore. One is that far from being automatic or governed by official orders, behavior undertaken in response to warnings is the product of interaction and deliberation among members of affected groups—activities that are typically accompanied by a search for additional confirmatory information. Circumstances that complicate the deliberation process, such as conflicting warning information that individuals and groups may receive, difficulties in getting in touch with others whose views are considered important for the decision-making process, or disagreements among group members about any aspect of the

threat situation, invariably lead to additional efforts to communicate and confirm the information and lengthen the period between when a warning is issued and when groups actually respond.

Another implication of the emergent norm approach to protective action decision making is the recognition that groups may collectively define an emergency situation in ways that are at variance from official views. This is essentially what occurs in the shadow evacuation phenomenon, which has been documented in several emergency situations, including the Three Mile Island nuclear plant accident (Zeigler et al., 1981). While authorities may not issue a warning for a particular geographic area or group of people, or may even tell them they are safe, groups may still collectively decide that they are at risk or that the situation is fluid and confusing enough that they should take self-protective action despite official pronouncements.

The behavior of occupants of the World Trade Center during the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack illustrates the importance of collectively developed definitions. Groups of people in Tower 2 of the World Trade Center decided that they should evacuate the building after seeing and hearing about what was happening in Tower 1 and after speaking with coworkers and loved ones, even when official announcements and other building occupants indicated that they should not do so. Others decided to remain in the tower or, perhaps more accurately, they decided to delay evacuating until receiving additional information clarifying the extent to which they were in danger. Journalistic accounts suggest that decisions were shaped in part by what people could see taking place in Tower 1, conversations with others outside the towers who had additional relevant information, and directives received from those in positions of authority in tenant firms. In that highly confusing and time-constrained situation, emergent norms guiding the behavior of occupants of the second tower meant the difference between life and death when the second plane struck (NIST, 2005).

The large body of research that exists regarding decision making under threat conditions points to the need to consider a wide range of individual, group, situational, and resource-related factors that facilitate and inhibit self-protective action. Qualitatively based decision-tree models developed by Gladwin et al. (2001) demonstrate the complexity of self-protective decisions. As illustrated by their work on hurricane evacuation, a number of different factors contribute to decisions on whether or not to evacuate. Such factors range from perceptions of risk and personal safety with respect to a threatened disaster, to the extent of knowledge about specific areas at risk, to constraining factors such as the presence of pets in the home that require care, lack of a suitable place to go, counterarguments by other family members, fears of looting (shown by the literature to be unjustified; see, for example, Fischer, 1998), and fear that the evacuation process may

be more dangerous than staying home and riding out a hurricane. Warning recipients may decide that they should wait before evacuating, ultimately missing the opportunity to escape, or they may decide to shelter in-place after concluding that their homes are strong enough to resist hurricane forces despite what they are told by authorities.

In their research on Hurricane Andrew, Gladwin and Peacock describe some of the many factors that complicate the evacuation process for endangered populations (1997:54):

Except under extreme circumstances, households cannot be compelled to evacuate or to remain where they are, much less to prepare themselves for the threat. Even under extraordinary conditions many households have to be individually located and assisted or forced to comply. Segments of a population may fail to receive, ignore, or discount official requests and orders. Still others may not have the resources or wherewithal to comply. Much will depend upon the source of the information, the consistency of the message received from multiple sources, the nature of the information conveyed, as well as the household’s ability to perceive the danger, make decisions, and act accordingly. Disputes, competition, and the lack of coordination among local, state, and federal governmental agencies and between those agencies and privately controlled media can add confusion. Businesses and governmental agencies that refuse to release their employees and suspend normal activities can add still further to the confusion and noncompliance.

The normalcy bias adds other complications to the warning response process. While popular notions of crisis response behaviors seem to assume that people react automatically to messages signaling impending danger—for example, by fleeing in panic—the reality is quite different. People typically “normalize” unusual situations and persist in their everyday activities even when urged to act differently. As noted earlier, people will not act on threat information unless they perceive a personal risk to themselves. Simply knowing that a threat exists—even if that threat is described as imminent—is insufficient to motivate self-protective action. Nor can people be expected to act if warning-related guidance is not specific enough to provide them with a blueprint for what to do or if they do not believe they have the resources required to follow the guidance. One practical implication of research on warnings is that rather than being concerned about panicking the public with warning information, or about communicating too much information, authorities should instead be seeking better ways to penetrate the normalcy bias, persuade people that they should be concerned about an impending danger, provide directives that are detailed enough to follow during an emergency, and encourage pre-disaster response planning so that people have thought through what to do prior to being required to act.

Other Important Findings Regarding the Evacuation Process

As noted earlier, evacuation behavior has long been recognized as the reflection of social-level factors and collective deliberation. Decades ago, Drabek (1983) established that households constitute the basic deliberative units for evacuation decision making in community-wide disasters and that the decisions that are ultimately made tend to be consistent with pre-disaster household authority patterns. For example, gender-related concerns often enter into evacuation decision making. Women tend to be more risk-averse and more inclined to want to follow evacuation orders, while males are less inclined to do so (for an extensive discussion of gender differences in vulnerability, risk perception, and responses to disasters, see Fothergill, 1998). In arriving at decisions regarding evacuation, households take official orders into account, but they weigh those orders in light of their own priorities, other information sources, and their past experiences. Information received from media sources and from family and friends, along with confirmatory data actively sought by those at risk, generally has a greater impact on evacuation decisions than information provided by public officials (Dow and Cutter, 1998, 2000).

Recent research also suggests that family evacuation patterns are undergoing change. For example, even though families decide together to evacuate and wish to stay together, they increasingly tend to use more than one vehicle to evacuate—perhaps because they want to take more of their possessions with them, make sure their valuable vehicles are protected, or return to their homes at different times (Dow and Cutter, 2002). Other social influences also play a role. Neighborhood residents may be more willing to evacuate or, conversely, more inclined to delay the decision to evacuate if they see their neighbors doing so. Rather than becoming more vigilant, communities that are struck repeatedly by disasters such as hurricanes and floods may develop “disaster subcultures,” such as groups that see no reason to heed evacuation orders since sheltering in-place has been effective in previous events.

NEHRP-sponsored research has shown that different racial, ethnic, income, and special needs groups respond in different ways to warning information and evacuation orders, in part because of the unique characteristics of these groups, the manner in which they receive information during crises, and their varying responses to different information sources. For example, members of some minority groups tend to have large extended families, making contacting family members and deliberating on alternative courses of action a more complicated process. Lower-income groups, inner-city residents, and elderly persons are more likely to have to rely on public transportation, rather than personal vehicles, in order to evacuate. Lower-income and minority populations, who tend to have larger families, may

also be reluctant to impose on friends and relatives for shelter. Lack of financial resources may leave less-well-off segments of the population less able to afford to take time off from work when disasters threaten, to travel long distances to avoid danger, or to pay for emergency lodging. Socially isolated individuals, such as elderly persons living alone, may lack the social support that is required to carry out self-protective actions. Members of minority groups may find majority spokespersons and official institutions less credible and believable than members of the white majority, turning instead to other sources, such as their informal social networks. Those who rely on non-English-speaking mass media for news may receive less complete warning information, or may receive warnings later than those who are tuned into mainstream media sources (Aguirre et al., 1991; Perry and Lindell, 1991; Lindell and Perry, 1992, 2004; Klinenberg, 2002; for more extensive discussions, see Tierney et al., 2001).

Hurricane Katrina vividly revealed the manner in which social factors such as those discussed above influence evacuation decisions and actions. In many respects, the Katrina experience validated what social science research had already shown with respect to evacuation behavior. Those who stayed behind did so for different reasons—all of which have been discussed in past research. Some at-risk residents lacked resources, such as automobiles and financial resources that would have enabled them to escape the city. Based on their past experiences with hurricanes like Betsey and Camille, others considered themselves not at risk and decided it was not necessary to evacuate. Still others, particularly elderly residents, felt so attached to their homes that they refused to leave even when transportation was offered.

This is not to imply that evacuation-related problems stemmed solely from individual decisions. Katrina also revealed the crucial significance of evacuation planning, effective warnings, and government leadership in facilitating evacuations. Planning efforts in New Orleans were rudimentary at best, clear evacuation orders were given too late, and the hurricane rendered evacuation resources useless once the city began to flood.

With respect to other patterns of evacuation behavior when they do evacuate, most people prefer to stay with relatives or friends, rather than using public shelters. Shelter use is generally limited to people who feel they have no other options—for example, those who have no close friends and relatives to take them in and cannot afford the price of lodging. Many people avoid public shelters or elect to stay in their homes because shelters do not allow pets. Following earthquakes, some victims, particularly Latinos in the United States who have experienced or learned about highly damaging earthquakes in their countries of origin, avoid indoor shelter of all types, preferring instead to sleep outdoors (Tierney, 1988; Phillips, 1993; Simile, 1995).

Disaster warnings involving “near misses,” as well as concerns about the possible impact of elevated color-coded homeland security warnings,

raise the question of whether warnings that do not materialize can induce a “cry-wolf” effect, resulting in lowered attention to and compliance with future warnings. The disaster literature shows little support for the cry-wolf hypothesis. For example, Dow and Cutter (1998) studied South Carolina residents who had been warned of impending hurricanes that ultimately struck North Carolina. Earlier false alarms did not influence residents’ decisions on whether to evacuate; that is, there was little behavioral evidence for a cry-wolf effect. However, false alarms did result in a decrease in confidence in official warning sources, as opposed to other sources of information on which people relied in making evacuation decisions—certainly not the outcome officials would have intended. Studies also suggest that it is advisable to clarify for the public why forecasts and warnings were uncertain or incorrect. Based on an extensive review of the warning literature, Sorensen (2000:121) concluded that “[t]he likelihood of people responding to a warning is not diminished by what has come to be labeled the ‘cry-wolf’ syndrome if the basis for the false alarm is understood [emphasis added].” Along those same lines, Atwood and Major (1998) argue that if officials explain reasons for false alarms, that information can increase public awareness and make people more likely to respond to subsequent hazard advisories.

PUBLIC RESPONSE

Dispelling myths about crisis-related behavior: panic and social breakdown.

Numerous individual studies and research syntheses have contrasted commonsense ideas about how people respond during crises with empirical data on actual behavior. Among the most important myths addressed in these analyses is the notion that panic and social disorganization are common responses to imminent threats and to actual disaster events (Quarantelli and Dynes, 1972; Johnson, 1987; Clarke, 2002). True panic, defined as highly individualistic flight behavior that is nonsocial in nature, undertaken without regard to social norms and relationships, is extremely rare prior to and during extreme events of all types. Panic takes place under specific conditions that are almost never present in disaster situations. Panic only occurs when individuals feel completely isolated and when both social bonds and measures to promote safety break down to such a degree that individuals feel totally on their own in seeking safety. Panic results from a breakdown in the ongoing social order—a breakdown that Clarke (2003:128) describes as having moral, network, and cognitive dimensions:

There is a moral failure, so that people pursue their self interest regardless

of rules of duty and obligation to others. There is a network failure, so that the resources that people can normally draw on in times of crisis are no longer there. There is a cognitive failure, in which someone’s understanding of how they are connected to others is cast aside.

Failures on this scale almost never occur during disasters. Panic reactions are rare in part because social bonds remain intact and extremely resilient even under conditions of severe danger (Johnson, 1987; Johnson et al., 1994; Feinberg and Johnson, 2001).

Panic persists in public and media discourses on disasters, in part because those discourses conflate a wide range of other behaviors with panic. Often, people are described as panicking because they experience feelings of intense fear, even though fright and panic are conceptually and behaviorally distinct. Another behavioral pattern that is sometimes labeled panic involves intensified rumors and information seeking, which are common patterns among publics attempting to make sense of confusing and potentially dangerous situations. Under conditions of uncertainty, people make more frequent use of both informal ties and official information sources, as they seek to collectively define threats and decide what actions to take. Such activities are a normal extension of everyday information-seeking practices (Turner, 1994). They are not indicators of panic.

The phenomenon of shadow evacuation, discussed earlier, is also frequently confused with panic. Such evacuations take place because people who are not defined by authorities as in danger nevertheless determine that they are—perhaps because they have received conflicting or confusing information or because they are geographically close to areas considered at risk (Tierney et al., 2001). Collective demands for antibiotics by those considered not at risk for anthrax, “runs” on stores to obtain self-protective items, and the so-called worried-well phenomenon are other forms of collective behavior that reflect the same sociobehavioral processes that drive shadow evacuations: emergent norms that define certain individuals and groups as in danger, even though authorities do not consider them at risk; confusion about the magnitude of the risk; a collectively defined need to act; and in some cases, an unwillingness to rely on official sources for self-protective advice. These types of behaviors, which constitute interesting subjects for research in their own right, are not examples of panic.

Research also indicates that panic and other problematic behaviors are linked in important ways to the manner in which institutions manage risk and disaster. Such behaviors are more likely to emerge when those who are in danger come to believe that crisis management measures are ineffective, suggesting that enhancing public understanding of and trust in preparedness measures and in organizations charged with managing disasters can lessen the likelihood of panic. With respect to homeland security threats, some researchers have argued that the best way to “vaccinate” the public

against the emergence of panic in situations involving weapons of mass destruction is to provide timely and accurate information about impending threats and to actively include the public in pre-crisis preparedness efforts (Glass and Shoch-Spana, 2002).

Blaming the public for panicking during emergencies serves to diffuse responsibility from professionals whose duty it is to protect the public, such as emergency managers, fire and public safety officials, and those responsible for the design, construction, and safe operation of buildings and other structures (Sime, 1999). The empirical record bears out the fact that to the extent panic does occur during emergencies, such behavior can be traced in large measure to environmental factors such as overcrowding, failure to provide adequate egress routes, and breakdowns in communications, rather than to some inherent human impulse to stampede with complete disregard for others. Any potential for panic and other problematic behaviors that may exist can, in other words, be mitigated through appropriate design, regulatory, management, and communications strategies.

As discussed elsewhere in this report, looting and violence are also exceedingly rare in disaster situations. Here again, empirical evidence of what people actually do during and following disasters contradicts what many officials and much of the public believe. Beliefs concerning looting are based not on evidence but rather on assumptions—for example, that social control breaks down during disasters and that lawlessness and violence inevitably result when the social order is disrupted. Such beliefs fail to take into account the fact that powerful norms emerge during disasters that foster prosocial behavior—so much so that lawless behavior actually declines in disaster situations. Signs erected following disasters saying, “We shoot to kill looters” are not so much evidence that looting is occurring as they are evidence that community consensus condemns looting.

The myth of disaster looting can be contrasted with the reality of looting during episodes of civil disorder such as the riots of the 1960s and the 1992 Los Angeles unrest. During episodes of civil unrest, looting is done publicly, in groups, quite often in plain sight of law enforcement officials. Taking goods and damaging businesses are the hallmarks of modern “commodity riots.” New norms also emerge during these types of crises, but unlike the prosocial norms that develop in disasters, norms governing behavior during civil unrest permit and actually encourage lawbreaking. Under these circumstances, otherwise law-abiding citizens allow themselves to take part in looting behavior (Dynes and Quarantelli, 1968; Quarantelli and Dynes, 1970).

Looting and damaging property can also become normative in situations that do not involve civil unrest—for example, in victory celebrations following sports events. Once again, in such cases, norms and traditions governing behavior in crowd celebrations encourage destructive activities

(Rosenfeld, 1997). The behavior of participants in these destructive crowd celebrations again bears no resemblance to that of disaster victims.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, social scientists had no problem understanding why episodes of looting might have been more widespread in that event than in the vast majority of U.S. disasters. Looting has occurred on a widespread basis following other disasters, although such cases have been rare. Residents of St. Croix engaged in extensive looting behavior following Hurricane Hugo, and this particular episode sheds light on why some Katrina victims might have felt justified in looting. Hurricane Hugo produced massive damage on St. Croix, and government agencies were rendered helpless. Essentially trapped on the island, residents had no idea when help would arrive. Instead, they felt entirely on their own following Hugo. The tourist-based St. Croix economy was characterized by stark social class differences, and crime and corruption had been high prior to the hurricane. Under these circumstances, looting for survival was seen as justified, and patterns of collective behavior developed that were not unlike those seen during episodes of civil unrest. Even law enforcement personnel joined in the looting (Quarantelli, 2006; Rodriguez et al., forthcoming).

Despite their similarities, the parallels between New Orleans and St. Croix should not be overstated. It is now clear that looting and violent behavior were far less common than initially reported and that rumors concerning shootings, rapes, and murders were groundless. The media employed the “looting frame” extensively while downplaying far more numerous examples of selflessness and altruism. In hindsight, it now appears that many reports involving looting and social breakdown were based on stereotyped images of poor minority community residents (Tierney et al., forthcoming).

Extensive research also indicates that despite longstanding evidence, beliefs about disaster-related looting and lawlessness remain quite common, and these beliefs can influence the behavior of both community residents and authorities. For example, those who are at risk may decide not to evacuate and instead stay in their homes to protect their property from looters (Fischer, 1998). Concern regarding looting and lawlessness may cause government officials to make highly questionable and even counterproductive decisions. Following Hurricane Katrina, for example, based largely on rumors and exaggerated media reports, rescue efforts were halted because of fears for the safety of rescue workers, and Louisiana’s governor issued a “shoot-to-kill” order to quash looting. These decisions likely resulted in additional loss of life and also interfered with citizen efforts to aid one another. Interestingly, recent historical accounts indicate that similar decisions were made following other large-scale disasters, such as the 1871 Chicago fire, the 1900 Galveston hurricane, and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and firestorm. In all three cases, armed force was used to stop

looting, and immigrant groups and the poor were scapegoated for their putative “crimes” (Fradkin, 2005). Along with Katrina, these events caution against making decisions on the basis of mythical beliefs and rumors.

As is the case with the panic myth, attributing the causes of looting behavior to individual motivations and impulses serves to deflect attention from the ways in which institutional failures can create insurmountable problems for disaster victims. When disasters occur, communications, disaster management, and service delivery systems should remain sufficiently robust that victims will not feel isolated and afraid or conclude that needed assistance will never arrive. More to the point, victims of disasters should not be scapegoated when institutions show themselves to be entirely incapable of providing even rudimentary forms of assistance—which was exactly what occurred with respect to Hurricane Katrina.

Patterns of Collective Mobilization in Disaster-Stricken Areas: Prosocial and Helping Behavior

In contrast to the panicky and lawless behavior that is often attributed to disaster-stricken populations, public behavior during earthquakes and other major community emergencies is overwhelmingly adaptive, prosocial, and aimed at promoting the safety of others and the restoration of ongoing community life. The predominance of prosocial behavior (and, conversely, a decline in antisocial behavior) in disaster situations is one of the most longstanding and robust research findings in the disaster literature. Research conducted with NEHRP sponsorship has provided an even better understanding of the processes involved in adaptive collective mobilization during disasters.

Helping Behavior and Disaster Volunteers. Helping behavior in disasters takes various forms, ranging from spontaneous and informal efforts to provide assistance to more organized emergent group activity, and finally to more formalized organizational arrangements. With respect to spontaneously developing and informal helping networks, disaster victims are assisted first by others in the immediate vicinity and surrounding area and only later by official public safety personnel. In a discussion on search and rescue activities following earthquakes, for example, Noji observes (1997:162)

In Southern Italy in 1980, 90 percent of the survivors of an earthquake were extricated by untrained, uninjured survivors who used their bare hands and simple tools such as shovels and axes…. Following the 1976 Tangshan earthquake, about 200,000 to 300,000 entrapped people crawled out of the debris on their own and went on to rescue others…. They became the backbone of the rescue teams, and it was to their credit that more than 80 percent of those buried under the debris were rescued.

Thus, lifesaving efforts in a stricken community rely heavily on the capabilities of relatively uninjured survivors, including untrained volunteers, as well as those of local firefighters and other relevant personnel.

The spontaneous provision of assistance is facilitated by the fact that when crises occur, they take place in the context of ongoing community life and daily routines—that is, they affect not isolated individuals but rather people who are embedded in networks of social relationships. When a massive gasoline explosion destroyed a neighborhood in Guadalajara, Mexico, in 1992, for example, survivors searched for and rescued their loved ones and neighbors. Indeed, they were best suited to do so, because they were the ones who knew who lived in different households and where those individuals probably were at the time of the disaster (Aguirre et al., 1995). Similarly, crowds and gatherings of all types are typically comprised of smaller groupings—couples, families, groups of friends—that become a source of support and aid when emergencies occur.

As the emergency period following a disaster lengthens, unofficial helping behavior begins to take on a more structured form with the development of emergent groups—newly formed entities that become involved in crisis-related activities (Stallings and Quarantelli, 1985; Saunders and Kreps, 1987). Emergent groups perform many different types of activities in disasters, from sandbagging to prevent flooding, to searching for and rescuing victims and providing for other basic needs, to post-disaster cleanup and the informal provision of recovery assistance to victims. Such groupings form both because of the strength of altruistic norms that develop during disasters and because of emerging collective definitions that victims’ needs are not being met—whether official agencies share those views or not. While emergent groups are in many ways essential for the effectiveness of crisis response activities, their activities may be seen as unnecessary or even disruptive by formal crisis response agencies. In the aftermath of the attack on the World Trade Center, for example, numerous groups emerged to offer every conceivable type of assistance to victims and emergency responders. Some were incorporated into official crisis management activities, while others were labeled “rogue volunteers” by official agencies (Halford and Nolan, 2002; Kendra and Wachtendorf, 2002). 2

Disaster-related volunteering also takes place within more formalized organizational structures, both in existing organizations that mobilize in response to disasters and through organizations such as the Red Cross,

which has a federal mandate to respond in presidentially declared disasters and relies primarily on volunteers in its provision of disaster services. Some forms of volunteering have been institutionalized in the United States through the development of the National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (NVOAD) organization. NVOAD, a large federation of religious, public service, and other groups, has organizational affiliates in 49 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and U.S. territories. National-level NVOAD affiliates include organizations such as the Salvation Army, Church World Service, Church of the Brethren Disaster Response, and dozens of others that provide disaster services. Organizations such as the Red Cross and the NVOAD federation thus provide an infrastructure that can support very extensive volunteer mobilization. That infrastructure will likely form the basis for organized volunteering in future homeland security emergencies, just as it does in major disasters.

Helping behavior is very widespread after disasters, particularly large and damaging ones. For example, NEHRP-sponsored research indicates that in the three weeks following the 1985 earthquake in Mexico City, an estimated 1.7 to 2.1 million residents of that city were involved in providing volunteer aid. Activities in which volunteers engaged after that disaster included searching for and rescuing victims trapped under rubble, donating blood and supplies, inspecting building damage, collecting funds, providing medical care and psychological counseling, and providing food and shelter to victims (Wenger and James, 1994). In other research on post-earthquake volunteering, also funded by NEHRP, O’Brien and Mileti (1992) found that more than half of the population in San Francisco and Santa Cruz counties provided assistance to their fellow victims after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake—help that ranged from assisting with search and rescue and debris removal activities to offering food, water, and shelter to those in need. Thus, the volunteer sector responding to disasters typically constitutes a very large proportion of the population of affected regions, as well as volunteers converging from other locations.

Social science research, much of it conducted under NEHRP auspices, highlights a number of other points regarding post-disaster helping behavior. One such insight is that helping behavior in many ways mirrors roles and responsibilities people assume during nondisaster times. For example, when people provide assistance during disasters and other emergencies, their involvement is typically consistent with gender role expectations (Wenger and James, 1994; Feinberg and Johnson, 2001). Research also indicates that mass convergence of volunteers and donations can create significant management problems and undue burdens on disaster-stricken communities. In their eagerness to provide assistance, people may “overrespond” to disaster sites, creating congestion and putting themselves and others at risk or insisting on providing resources that are in fact not needed. After disas-

ters, communities typically experience major difficulties in dealing with unwanted and unneeded donations (Neal, 1990).

Research on public behavior during disasters has major implications for homeland security policies and practices. The research literature provides support for the inclusion of the voluntary sector and community-based organizations in preparedness and response efforts. Initiatives that aim at encouraging public involvement in homeland security efforts of all types are clearly needed. The literature also provides extensive evidence that members of the public are in fact the true “first responders” in major disasters. In using that term to refer to fire, police, and other public safety organizations, current homeland security discourse fails to recognize that community residents themselves constitute the front-line responders in any major emergency

One implication of this line of research is that planning and management models that fail to recognize the role of victims and volunteers in responding to all types of extreme events will leave responders unprepared for what will actually occur during disasters—for example, that, as research consistently shows, community residents will be the first to search for victims, provide emergency aid, and transport victims to health care facilities in emergencies of all types. 3 Such plans will also fail to take advantage of the public’s crucial skills, resources, and expertise. For this reason, experts on human-induced threats such as bioterrorism stress the value of public engagement and involvement in planning for homeland security emergencies (Working Group on “Governance Dilemmas” in Bioterrorism Response, 2004).

These research findings have significant policy implications. To date, Department of Homeland Security initiatives have focused almost exclusively on providing equipment and training for uniformed responders, as opposed to community residents. Recently, however, DHS has begun placing more emphasis on its Citizen Corps component, which is designed to mobilize the skills and talents of the public when disasters strike. Public involvement in Citizen Corps and Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) activities have expanded considerably since the terrorist attacks of

9/11—a sign that many community residents around the nation wish to play an active role in responding to future disasters. The need for community-based preparedness and response initiatives is more evident than ever follow-ing the Katrina disaster.

Organizational, Governmental, and Network Responses. The importance of observing disaster response operations while they are ongoing or as soon as possible after disaster impact has long been a hallmark of the disaster research field. The quick-response tradition in disaster research, which has been a part of the field since its inception, developed out of a recognition that data on disaster response activities are perishable and that information collected from organizations after the passage of time is likely to be distorted and incomplete (Quarantelli, 1987, 2002). NEHRP funds, provided through grant supplements, Small Grants for Exploratory Research (SGER) awards, Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI) reconnaissance missions, earthquake center reconnaissance funding, and small grants such as those provided by the Natural Hazards Research and Applications Information Center, have supported the collection of perishable data and enabled social science researchers to mobilize rapidly following major earthquakes and other disasters.

NEHRP provided substantial support for the collection of data on organizational and community responses in a number of earthquake events, including the 1987 Whittier Narrows, 1989 Loma Prieta, and 1994 Northridge earthquakes (see, for example, Tierney, 1988, 1994; EERI, 1995), as well as major earthquakes outside the United States such as the 1985 Mexico City, 1986 San Salvador, and 1988 Armenia events. More recently, NEHRP funds were used to support rapid-response research on the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks and Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Many of those studies focused on organizational issues in both the public and private sectors. (For a compilation of NEHRP-sponsored quick-response findings on the events of September 11, see Natural Hazards Research and Applications Information Center, 2003).

In many cases, quick-response research on disaster impacts and organizational and governmental response has led to subsequent in-depth studies on response-related issues identified during the post-impact reconnaissance phase. Following major events such as Loma Prieta, Northridge, and Kobe, insights from initial reconnaissance studies have formed the basis for broader research initiatives. Recent efforts have focused on ways to better take advantage of reconnaissance opportunities and to identify topics for longer-term study. A new plan has been developed to better coordinate and integrate both reconnaissance and longer-term research activities carried out with NEHRP support. That planning activity, outlined in the report The Plan to Coordinate NEHRP Post-earthquake Investigations (Holzer et

al., 2003), encompasses both reconnaissance and more systematic research activities in the earth sciences, engineering, and social sciences.

Through both initial quick-response activities and longer-term studies, NEHRP research has added to the knowledge base on how organizations cope with crises. Studies have focused on a variety of topics. A partial list of those topics includes organizational and group activities associated with the post-disaster search and rescue process (Aguirre et al., 1995); intergovernmental coordination during the response period following major disaster events (Nigg, 1998); expected and improvised organizational forms that characterize the disaster response milieu (Kreps, 1985, 1989b); strategies used by local government organizations to enhance interorganizational coordination following disasters (Drabek, 2003); and response activities undertaken by specific types of organizations, such as those in the volunteer and nonprofit sector (Neal, 1990) and tourism-oriented enterprises (Drabek, 1994).

Focusing specifically at the interorganizational level of analysis, NEHRP research has also highlighted the significance and mix of planned and improvised networks in disaster response. It has long been recognized that post-disaster response activities involve the formation of new (or emergent) networks of organizations. Indeed, one distinguishing feature of major crisis events is the prominence and proliferation of network forms of organization during the response period. Emergent multiorganizational networks (EMON) constitute new organizational interrelationships that reflect collective efforts to manage crisis events. Such networks are typically heterogeneous, consisting of existing organizations with pre-designated crisis management responsibilities, other organizations that may not have been included in prior planning but become involved in crisis response activities because those involved believe they have some contribution to make, and emergent groups. EMONs tend to be very large in major disaster events, encompassing hundreds and even thousands of interacting entities. As crisis conditions change and additional resources converge, EMON structures evolve, new organizations join the network, and new relationships form. What is often incorrectly described as disaster-generated “chaos” is more accurately seen as the understandable confusion that results when mobilization takes place on such a massive scale and when organizations and groups that may be unfamiliar with one another attempt to communicate, negotiate, and coordinate their activities under extreme pressure. (For more detailed discussions on EMONs in disasters, including the 2001 World Trade Center attack, see Drabek, 1985, 2003; Tierney, 2003; Tierney and Trainor, 2004.)

This is not to say that response activities always go smoothly. The disaster literature, organizational after-action reports, and official investigations contain numerous examples of problems that develop as inter-

organizational and intergovernmental networks attempt to address disaster-related challenges. Such problems include the following: failure to recognize the magnitude and seriousness of an event; delayed and insufficient responses; confusion regarding authorities and responsibilities, often resulting in major “turf battles;” resource shortages and misdirection of existing resources; poor organizational, interorganizational, and public communications; failures in intergovernmental coordination; failures in leadership and vision; inequities in the provision of disaster assistance; and organizational practices and cultures that permit and even encourage risky behavior. Hurricane Katrina became a national scandal because of the sheer scale on which these organizational pathologies manifested. However, Katrina was by no means atypical. In one form or another and at varying levels of severity, such pathologies are ever-present in the landscape of disaster response (for examples, see U.S. President’s Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island, 1979; Perrow, 1984; Shrivastava, 1987; Sagan, 1993; National Academy of Public Administration, 1993; Vaughan, 1996, 1999; Peacock et al., 1997; Klinenberg, 2002; Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparations for and Response to Hurricane Katrina, 2006; White House, 2006).

Management Considerations in Disaster Response

U.S. disaster researchers have identified two contrasting approaches to disaster response management, commonly termed the “command-and-control” and the “emergent human resources,” or “problem-solving,” models. The command-and-control model equates preparedness and response activities with military exercises. It assumes that (1) government agencies and other responders must be prepared to take over management and control in disaster situations, both because they are uniquely qualified to do so and because members of the public will be overwhelmed and will likely engage in various types of problematic behavior, such as panic; (2) disaster response activities are best carried out through centralized direction, control, and decision making; and (3) for response activities to be effective, a single person is ideally in charge, and relations among responding entities are arranged hierarchically.

In contrast, the emergent human resources, or problem-solving, model is based on the assumption that communities and societies are resilient and resourceful and that even in areas that are very hard hit by disasters, considerable local response capacity is likely to remain. Another underlying assumption is that preparedness strategies should build on existing community institutions and support systems—for example by pre-identifying existing groups, organizations, and institutions that are capable of assuming leadership when a disaster strikes. Again, this approach argues against