Here’s How Bad a Nuclear War Would Actually Be

W e know that an all-out U.S.-Russia nuclear war would be bad. But how bad, exactly? How do your chances of surviving the explosions, radiation, and nuclear winter depend on where you live? The past year’s unprecedented nuclear saber-rattling and last weekend’s chaos in Russia has made this question timely. To help answer it, I’ve worked with an amazing interdisciplinary group of scientists (see end credits) to produce the most scientifically realistic simulation of a nuclear war using only unclassified data, and visualize it as a video . It combines detailed modeling of nuclear targeting, missile trajectories, blasts and the electromagnetic pulse, and of how black carbon smoke is produced, lofted and spread across the globe, altering the climate and causing mass starvation.

As the video illustrates, it doesn’t matter much who starts the war: when one side launches nuclear missiles, the other side detects them and fires back before impact. Ballistic missiles from U.S. submarines west of Norway start striking Russia after about 10 minutes, and Russian ones from north of Canada start hitting the U.S. a few minutes later. The very first strikes fry electronics and power grids by creating an electro-magnetic pulse of tens of thousands of volts per meter. The next strikes target command-and-control centers and nuclear launch facilities. Land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles take about half an hour to fly from launch to target.

More from TIME

Major cities are targeted both because they contain military facilities and to stymie the enemy’s post-war recovery. Each impact creates a fireball about as hot as the core of the sun, followed by a radioactive mushroom cloud. These intense explosions vaporize people nearby and cause fires and blindness further away. The fireball expansion then causes a blast wave that damages buildings, crushing nearby ones. The U.K. and France have nuclear capabilities and are obliged by NATO’s Article 5 to defend the U.S. so, Russia hits them too. Firestorms engulf many cities, where storm-level winds fan the flames, igniting anything that can burn, melting glass and some metals and turning asphalt into flammable hot liquid.

Unfortunately, peer-reviewed research suggests that explosions, the electromagnetic pulse, and the radioactivity aren’t the worst part: a nuclear winter is caused by the black carbon smoke from the nuclear firestorms. The Hiroshima atomic bomb caused such a firestorm, but today’s hydrogen bombs are much more powerful. A large city like Moscow, with almost 50 times more people than Hiroshima, can create much more smoke, and a firestorm that sends plumes of black smoke up into the stratosphere, far above any rain clouds that would otherwise wash out the smoke. This black smoke gets heated by sunlight, lofting it like a hot air balloon for up to a decade. High-altitude jet streams are so fast that it takes only a few days for the smoke to spread across much of the northern hemisphere.

This makes Earth freezing cold even during the summer, with farmland in Kansas cooling by about 20 degrees centigrade (about 40 degrees Fahrenheit), and other regions cooling almost twice as much. A recent scientific paper estimates that over 5 billion people could starve to death, including around 99% of those in the US, Europe, Russia, and China – because most black carbon smoke stays in the Northern hemisphere where it’s produced, and because temperature drops harm agriculture more at high latitudes.

It’s important to note that huge uncertainties remain, so the actual humanitarian impact could be either better or worse – a reason to proceed with caution. A recently launched $4M open research program will hopefully help clarify public understanding and inform the global policy conversation, but much more work is needed, since most of the research on this topic is classified and focused on military rather than humanitarian impacts.

We obviously don’t know how many people will survive a nuclear war. But if it’s even remotely as bad as this study predicts, it has no winners, merely losers. It’s easy to feel powerless, but the good news is that there is something you can do to help: please help share this video! The fact that nuclear war is likely to start via gradual escalation, perhaps combined by accident or miscalculation, means that the more people know about nuclear war, the more likely we are to avoid having one.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- The New Face of Doctor Who

- Putin’s Enemies Are Struggling to Unite

- Women Say They Were Pressured Into Long-Term Birth Control

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- Boredom Makes Us Human

- John Mulaney Has What Late Night Needs

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

The Devastating Effects of Nuclear Weapons

What can nuclear weapons do? How do they achieve their destructive purpose? What would a nuclear war — and its aftermath — look like? In the article that follows, excerpted from Richard Wolfson and Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress’s book “ Nuclear Choices for the Twenty-First Century ,” the authors explore these and related questions that reveal the most horrifying realities of nuclear war.

A Bomb Explodes: Short-Term Effects

The most immediate effect of a nuclear explosion is an intense burst of nuclear radiation, primarily gamma rays and neutrons. This direct radiation is produced in the weapon’s nuclear reactions themselves, and lasts well under a second. Lethal direct radiation extends nearly a mile from a 10-kiloton explosion. With most weapons, though, direct radiation is of little significance because other lethal effects generally encompass greater distances. An important exception is the enhanced-radiation weapon, or neutron bomb, which maximizes direct radiation and minimizes other destructive effects.

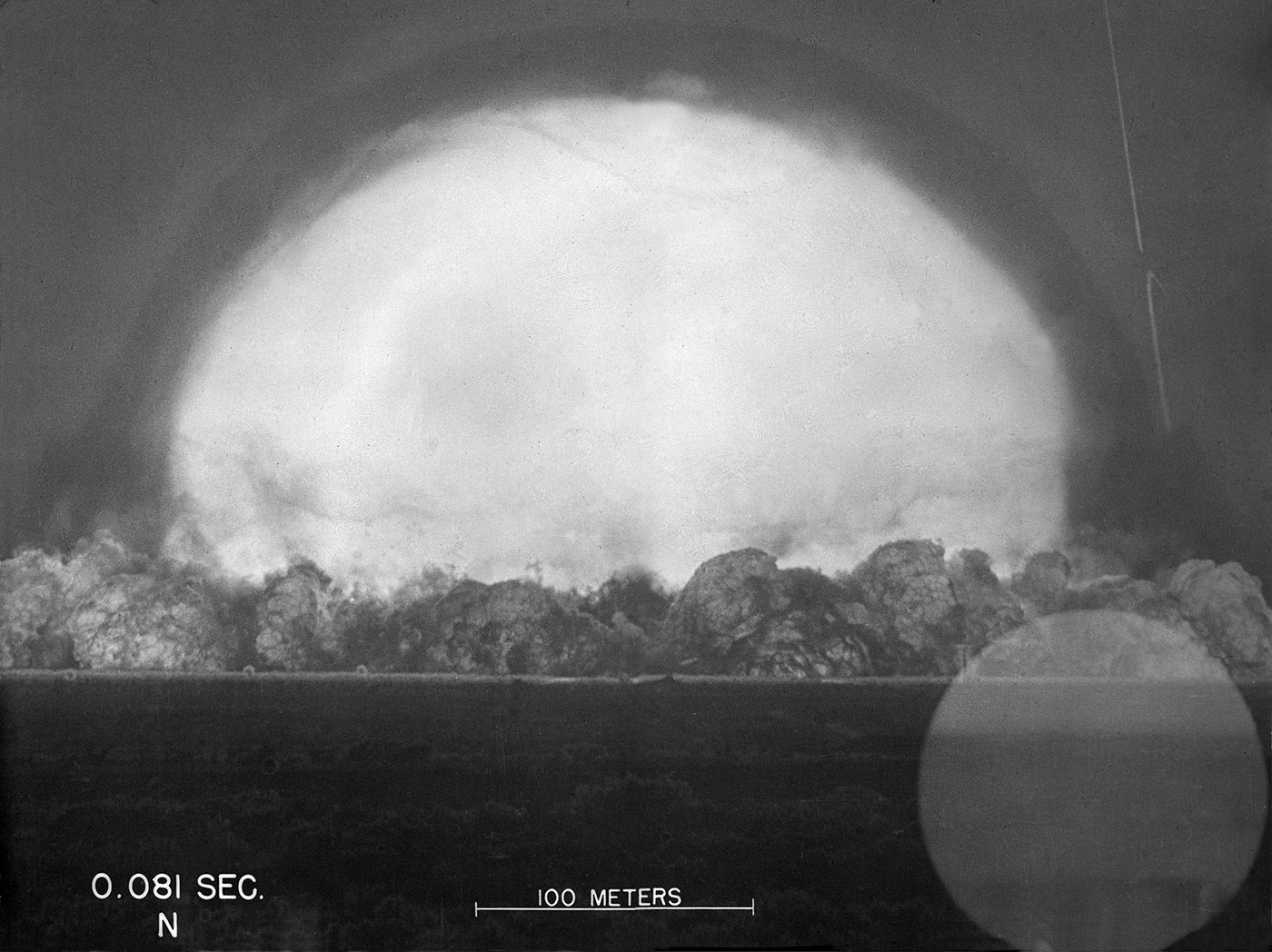

An exploding nuclear weapon instantly vaporizes itself. What was cold, solid material microseconds earlier becomes a gas hotter than the Sun’s 15-million-degree core. This hot gas radiates its energy in the form of X-rays, which heat the surrounding air. A fireball of superheated air forms and grows rapidly; 10 seconds after a 1-megaton explosion, the fireball is a mile in diameter. The fireball glows visibly from its own heat — so visibly that the early stages of a 1-megaton fireball are many times brighter than the Sun even at a distance of 50 miles. Besides light, the glowing fireball radiates heat.

This thermal flash lasts many seconds and accounts for more than one-third of the weapon’s explosive energy. The intense heat can ignite fires and cause severe burns on exposed flesh as far as 20 miles from a large thermonuclear explosion. Two-thirds of injured Hiroshima survivors showed evidence of such flash burns. You can think of the incendiary effect of thermal flash as analogous to starting a fire using a magnifying glass to concentrate the Sun’s rays. The difference is that rays from a nuclear explosion are so intense that they don’t need concentration to ignite flammable materials.

The intense heat can ignite fires and cause severe burns on exposed flesh as far as 20 miles from a large thermonuclear explosion.

As the rapidly expanding fireball pushes into the surrounding air, it creates a blast wave consisting of an abrupt jump in air pressure. The blast wave moves outward initially at thousands of miles per hour but slows as it spreads. It carries about half the bomb’s explosive energy and is responsible for most of the physical destruction. Normal air pressure is about 15 pounds per square inch (psi). That means every square inch of your body or your house experiences a force of 15 pounds. You don’t usually feel that force, because air pressure is normally exerted equally in all directions, so the 15 pounds pushing a square inch of your body one way is counterbalanced by 15 pounds pushing the other way. What you do feel is overpressure , caused by a greater air pressure on one side of an object.

If you’ve ever tried to open a door against a strong wind, you’ve experienced overpressure. An overpressure of even 1/100 psi could make a door almost impossible to open. That’s because a door has lots of square inches — about 3,000 or more. So 1/100 psi adds up to a lot of pounds. The blast wave of a nuclear explosion may create overpressures of several psi many miles from the explosion site. Think about that! There are about 50,000 square inches in the front wall of a modest house — and that means 50,000 pounds or 25 tons of force even at 1 psi overpressure. Overpressures of 5 psi are enough to destroy most residential buildings. An overpressure of 10 psi collapses most factories and commercial buildings, and 20 psi will level even reinforced concrete structures.

People, remarkably, are relatively immune to overpressure itself. But they aren’t immune to collapsing buildings or to pieces of glass hurtling through the air at hundreds of miles per hour or to having themselves hurled into concrete walls — all of which are direct consequences of a blast wave’s overpressure. Blast effects therefore cause a great many fatalities. Blast effects depend in part on where a weapon is detonated. The most widespread damage to buildings occurs in an air burst , a detonation thousands of feet above the target. The blast wave from an air burst reflects off the ground, which enhances its destructive power. A ground burst , in contrast, digs a huge crater and pulverizes everything in the immediate vicinity, but its blast effects don’t extend as far. Nuclear attacks on cities would probably employ air bursts, whereas ground bursts would be used on hardened military targets such as underground missile silos. As you’ll soon see, the two types of blasts have different implications for radioactive fallout.

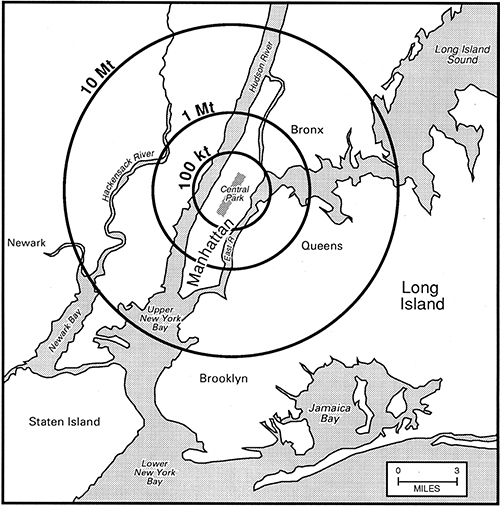

How far do a weapon’s destructive effects extend? That distance — the radius of destruction — depends on the explosive yield. The volume encompassing a given level of destruction depends directly on the weapon’s yield. Because volume is proportional to the radius cubed, that means the destructive radius grows approximately as the cube root of the yield. A 10-fold increase in yield then increases the radius of destruction by a factor of only a little over two. The area of destruction grows faster but still not in direct proportion to the yield. That relatively slow increase in destruction with increasing yield is one reason why multiple smaller weapons are more effective than a single larger one. Twenty 50-kiloton warheads, for example, destroy nearly three times the area leveled by a numerically equivalent 1-megaton weapon.

What constitutes the radius of destruction also depends on the level of destruction you want to achieve. Roughly speaking, though, the distance at which overpressure has fallen to about 5 psi is a good definition of destructive radius. Many of the people within this distance would be killed, although some wouldn’t. But some would be killed beyond the 5-psi distance, making the situation roughly equivalent to having everyone within the 5-psi circle killed and everyone outside surviving. The image to the left shows how the destructive zone varies with explosive yield for a hypothetical explosion. This is a simplified picture; a more careful calculation of the effects of nuclear weapons on entire populations requires detailed simulations that include many environmental and geographic variables.

The blast wave is over in a minute or so, but the immediate destruction may not be. Fires started by the thermal flash or by blast effects still rage, and under some circumstances they may coalesce into a single gigantic blaze called a firestorm that can develop its own winds and thus cause the fire to spread. Hot gases rise from the firestorm, replaced by air rushing inward along the surface at hundreds of miles per hour. Winds and fire compound the blast damage, and the fire consumes enough oxygen to suffocate any remaining survivors.

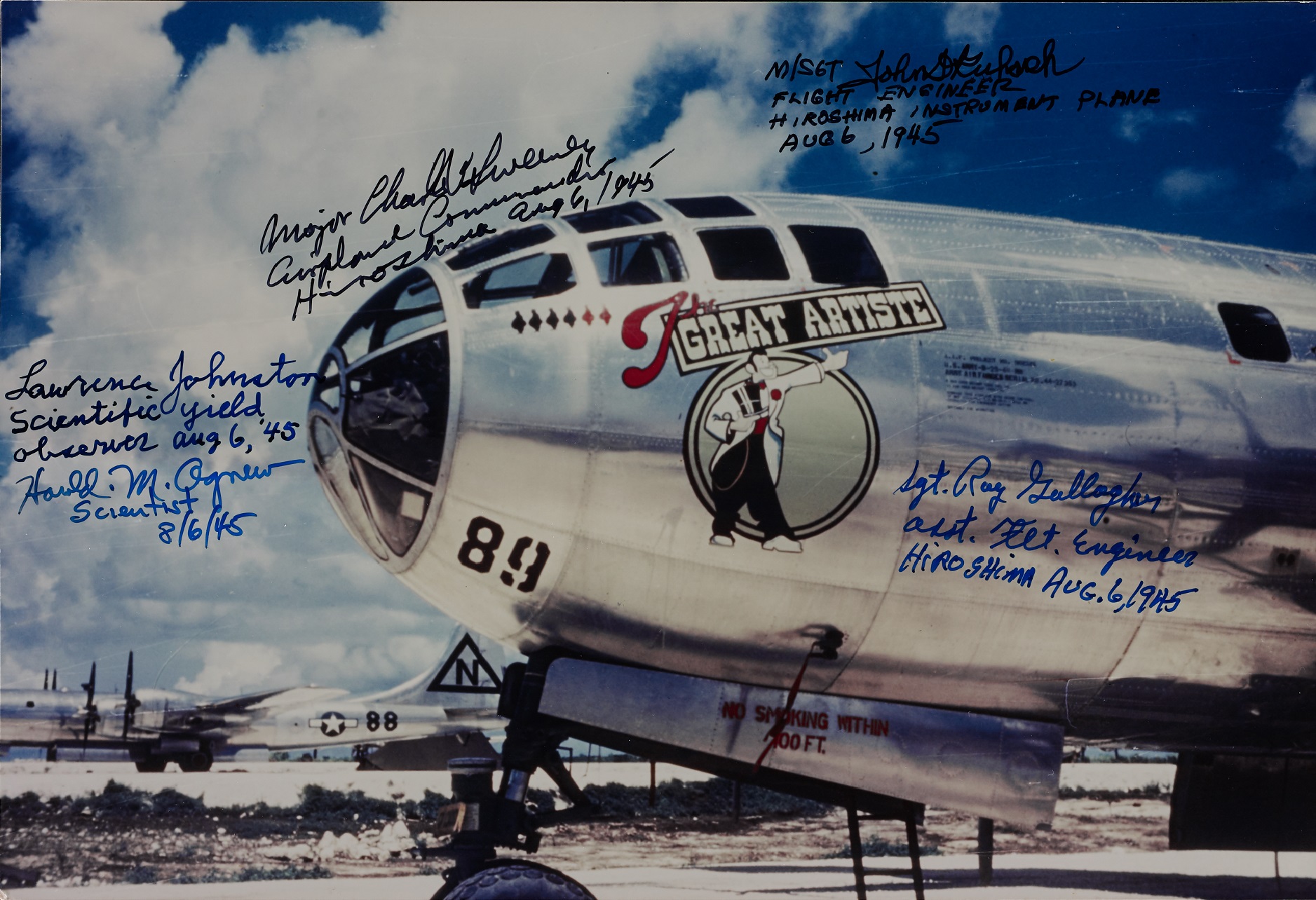

During World War II, bombing of Hamburg with incendiary chemicals resulted in a firestorm that claimed 45,000 lives. The nuclear bombing of Hiroshima resulted in a firestorm; that of Nagasaki did not, likely because of Nagasaki’s rougher terrain. The question of firestorms is important not only to the residents of a target area: Firestorms might also have significant long-term effects on the global climate, as we’ll discuss later.

Both nuclear and conventional weapons produce destructive blast effects, although of vastly different magnitudes. But radioactive fallout is unique to nuclear weapons. Fallout consists primarily of fission products, although neutron capture and other nuclear reactions contribute additional radioactive material. The term fallout generally applies to those isotopes whose half-lives exceed the time scale of the blast and other short-term effects. Although fallout contamination may linger for years and even decades, the dominant lethal effects last from days to weeks, and contemporary civil defense recommendations are for survivors to stay inside for at least 48 hours while the radiation decreases.

The fallout produced in a nuclear explosion depends greatly on the type of weapon, its explosive yield, and where it’s exploded. The neutron bomb, although it produces intense direct radiation, is primarily a fusion device and generates only slight fallout from its fission trigger. Small fission weapons like those used at Hiroshima and Nagasaki produce locally significant fallout. But the fission-fusion-fission design used in today’s thermonuclear weapons introduces the new phenomenon of global fallout . Most of this fallout comes from fission of the U-238 jacket that surrounds the fusion fuel. The global effect of these huge weapons comes partly from the sheer quantity of radioactive material and partly from the fact that the radioactive cloud rises well into the stratosphere, where it may take months or even years to reach the ground. Even though we’ve had no nuclear war since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, fallout is one weapons effect with which we have experience. Atmospheric nuclear testing before the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty resulted in detectable levels of radioactive fission products across the globe, and some of that radiation is still with us.

Fallout differs greatly depending on whether a weapon is exploded at ground level or high in the atmosphere. In an air burst, the fireball never touches the ground, and radioactivity rises into the stratosphere. This reduces local fallout but enhances global fallout. In a ground burst, the explosion digs a huge crater and entrains tons of soil, rock, and other pulverized material into its rising cloud. Radioactive materials cling to these heavier particles, which drop back the ground in a relatively short time. Rain may wash down particularly large amounts of radioactive material, producing local hot spots of especially intense radioactivity. A hot spot in Albany, New York, thousands of miles from the 1953 Nevada test that produced it, exposed area residents to some 10 times their annual background radiation dose. The exact distribution of fallout depends crucially on wind speed and direction; under some conditions, lethal fallout may extend several hundred miles downwind of an explosion. However, it’s important to recognize that the lethality of fallout quickly decreases as short-lived isotopes decay.

Recommended Response to a Nuclear Explosion

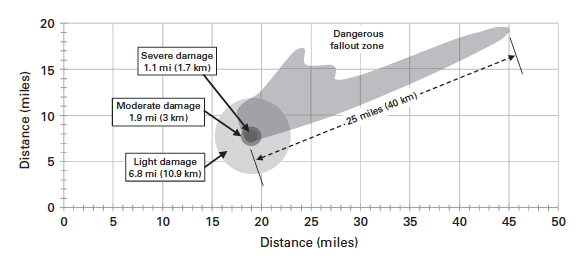

The United States government has recently provided guidance on how to respond to a nuclear detonation. One recommendation is to divide the region of destruction due to blast effects into three separate damage zones. This division provides guidance for first responders in assessing the situation. Outermost is the light damage zone , characterized by “broken windows and easily managed injuries.” Next is the moderate damage zone with “significant building damage, rubble, downed utility lines and some downed poles, overturned automobiles, fires, and serious injuries.” Finally, there’s the severe damage zone , where buildings will be completely collapsed, radiation levels high, and survivors unlikely.

The recommendations also define a dangerous fallout zone spanning different structural damage zones. This is the region where dose rates exceed a whole-body external dose of about 0.1 Sv/hour. First responders must exercise special precautions as they approach the fallout zone in order to limit their own radiation exposure. The dangerous fallout zone can easily stretch 10 to 20 miles (15 to 30 kilometers) from the detonation depending on explosive yield and weather conditions.

Electromagnetic Pulse

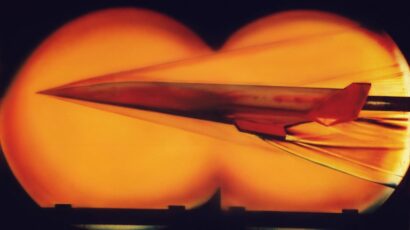

A nuclear weapon exploded at very high altitude produces none of the blast or local fallout effects we’ve just described. But intense gamma rays knock electrons out of atoms in the surrounding air, and when the explosion takes place in the rarefied air at high altitude this effect may extend hundreds of miles. As they gyrate in Earth’s magnetic field, the electrons generate an intense pulse of radio waves known as an electromagnetic pulse (EMP).

A single large weapon exploded some 200 miles over the central United States could blanket the entire country with an electromagnetic pulse intense enough to damage computers, communication systems, and other electronic devices. It could also affect satellites used for military communications, reconnaissance, and attack warning. The EMP phenomenon thus has profound implications for a military that depends on sophisticated electronics. In 1962, the United States detonated a 1.4-megaton warhead 250 miles above Johnston Island in the Pacific Ocean. People as far as Australia and New Zealand witnessed the explosion as a red aurora appearing in the night sky. Hawaiians, only 800 miles from the island, experienced a bright flash followed by a green sky and the failure of hundreds of street lights. In total, the Soviet Union and the United States conducted 20 tests of EMP from nuclear detonations. However, it’s unclear how to extrapolate the results to today’s more sensitive and more pervasive electronic equipment.

Since the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963 it has been virtually impossible to study EMP effects directly, although elaborate devices have been developed to mimic the electronic impact of nuclear weapons. Increasingly, crucial electronic systems are “hardened” to minimize the impact of EMP. Nevertheless, the use of EMP in a war could wreak havoc with systems for communication and control of military forces.

Many countries are around the world are developing high-powered microwave weapons which, although not nuclear devices, are designed to produce EMPs. These directed-energy weapons , also called e-bombs , emit large pulses of microwaves to destroy electronics on missiles, to stop cars, to detonate explosives remotely, and to down swarms of drones. Despite these EMP weapons being nonlethal in the sense that there’s no bang or blast wave, an enemy may be unable to distinguish their effects from those of nuclear weapons.

Would the high-altitude detonation of a nuclear weapon to produce EMP or the use of a directed-beam EMP weapon be an act of war warranting nuclear retaliation? With its electronic warning systems in disarray, should the EMPed nation launch a nuclear strike on the chance that it was about to be attacked? How are nuclear decisions to be made in a climate of EMP-crippled communications? These are difficult questions, but military strategists need to have answers.

Nuclear War

So far we’ve examined the effects of single nuclear explosions. But a nuclear war would involve hundreds to thousands of explosions, creating a situation for which we simply have no relevant experience. Despite decades of arms reduction treaties, there are still thousands of nuclear weapons in the world’s arsenals. Detonating only a tiny fraction of these would cause mass casualties.

What would a nuclear war be like? When you think of nuclear war, you probably envision an all-out holocaust in which adversaries unleash their arsenals in an attempt to inflict the most damage. Many people — including your authors — believe that misfortune to be the likely outcome of almost any use of nuclear weapons among the superpowers. But nuclear strategists have explored many scenarios that fall short of the all-out nuclear exchange. What might these limited nuclear wars be like? Could they really remain limited ?

Limited Nuclear War

One form of limited nuclear war would be like a conventional battlefield conflict but using low-yield tactical nuclear weapons. Here’s a hypothetical scenario: After its 2014 annexation of Crimea, Russia attacks a Baltic country with tanks and ground forces while the United States is distracted by a domestic crisis. NATO responds with decisive counterforce, destroying Russian tanks with fighter jets, but this doesn’t quell Russian resolve. Russia responds with even more tanks and by bombing NATO installations, killing several hundred troops. NATO cannot tolerate such aggression and to prevent further Russian advance launches low-yield tactical nuclear weapons with their dial-a-yield positions set to the lowest settings of only 300 tons TNT equivalent. The goal is to signal Russia that it has crossed a line and to deescalate the situation. NATO’s actions are based on fear that if the Russian aggression weren’t stopped the result would be all-out war in northern Europe.

This strategy is actually being discussed in the higher echelons of the Pentagon. The catchy concept is that use of a few low-yield nuclear weapons could show resolve, with the hoped-for outcome that the other party will back down from its aggressive behavior (this concept is known as escalate to deescalate ). The assumption is that the nuclear attack would remain limited, that parties would go back to the negotiating table, and that saner voices would prevail. However, this assumes a chain of events where everything unfolds as expected. It neglects the incontrovertible fact that, as the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz observed in the 19th century, “Three quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty.” Often coined fog of war , this describes the lack of clarity in wartime situations on which decisions must nevertheless be based. In the scenario described, sensors could have been damaged or lines of communication severed that would have reported the low-yield nature of the nuclear weapons. As a result, Russia might feel its homeland threatened and respond with an all-out attack using strategic nuclear weapons, resulting in millions of deaths.

There is every reason to believe that a limited nuclear war wouldn’t remain limited.

There is every reason to believe that a limited nuclear war wouldn’t remain limited. A 1983 war game known as Proud Prophet involved top-secret nuclear war plans and had as participants high-level decision makers including President Reagan’s Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger. The war game followed actual plans but unexpectedly ended in total nuclear annihilation with more than half a billion fatalities in the initial onslaught — not including subsequent deaths from starvation. The exercise revealed that a limited nuclear strike may not achieve the desired results! In this case, that was because the team playing the Soviet Union responded to a limited U.S. nuclear strike with a massive all-out nuclear attack.

What about an attack on North Korea? In 2017, some in the U.S. cabinet advocated for a “bloody nose” strategy in dealing with North Korea’s flagrant violations of international law. This is the notion that in response to a threatening action by North Korea, the U.S. would destroy a significant site to “bloody Pyongyang’s nose.” This might employ a low-yield nuclear attack or a conventional attack. The “bloody nose” strategy relies on the expectation that Pyongyang would be so overwhelmed by U.S. might that they would immediately back down and not retaliate. However, North Korea might see any type of aggression as an attack aimed at overthrowing their regime, and could retaliate with an all-or-nothing response using weapons of mass destruction (including but not necessarily limited to nuclear weapons) as well as their vast conventional force.

In September 2017, during the height of verbal exchanges between President Trump and the North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un, the U.S. flew B-1B Lancer bombers along the North Korean coast, further north of the demilitarized zone than the U.S. had ever done, while still staying over international waters. However, North Korea didn’t respond at all, making analysts wonder whether the bombers were even detected. Uncertainty in North Korea’s ability to discriminate different weapon systems might exacerbate a situation like this one and could lead the North Koreans viewing any intrusion as an “attack on their nation, their way of life and their honor.” This is exactly how the Soviet team in the Proud Prophet war game interpreted it.

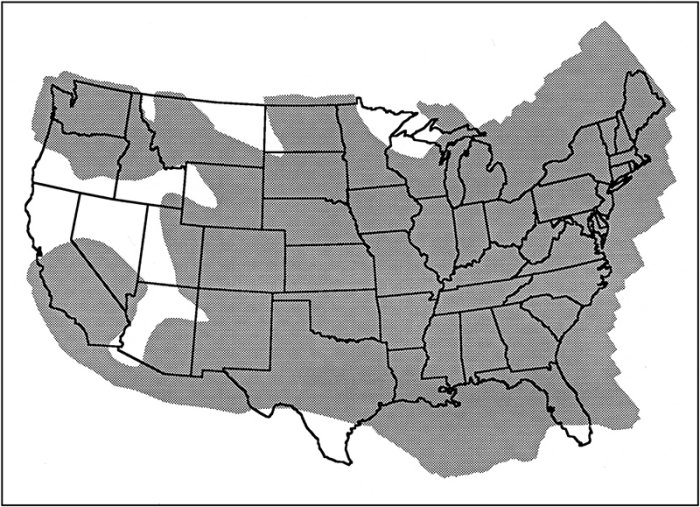

What about a limited attack on the United States? Suppose a nuclear adversary decided to cripple the U.S. nuclear retaliatory forces (a virtual impossibility, given nuclear missile submarines, but a scenario considered with deadly seriousness by nuclear planners). Many of the 48 contiguous states have at least one target — a nuclear bomber base, a submarine support base, or intercontinental missile silos — that would warrant destruction in such an attack. The attack, which would require only a tiny fraction of the strategic nuclear weapons in the Russian arsenal, could kill millions of civilians. Those living near targeted bomber and submarine bases would suffer blast and local radiation effects. Intense fallout from ground-burst explosions on missile silos in the Midwest would extend all the way to the Atlantic coast. Fallout would also contaminate a significant fraction of U.S. cropland for up to year and would kill livestock. On the other hand, the U.S. industrial base would remain relatively unscathed, if no further hostilities occurred.

In contrast to attacking military targets, an adversary might seek to cripple the U.S. economy by destroying a vital industry. In one hypothetical attack considered by the congressional Office of Technology Assessment, ten Soviet SS-18 missiles, each with eight 1-megaton warheads, attack United States’ oil refineries. The result is destruction of two-thirds of the U.S. oil-refining capability. And even with some evacuation of major cities in the hypothetical crisis leading to the attack, 5 million Americans are killed.

Each of these “limited” nuclear attack scenarios kills millions of Americans — many, many times the 1.2 million killed in all the wars in our nation’s history. Do we want to entertain limited nuclear war as a realistic possibility? Do we believe nuclear war could be limited to “only” a few million casualties? Do we trust the professional strategic planners who prepare our possible nuclear responses to an adversary’s threats? What level of nuclear preparedness do we need to deter attack?

All-Out Nuclear War

Whether from escalation of a limited nuclear conflict or as an outright full-scale attack, an all-out nuclear war remains possible as long as nuclear nations have hundreds to thousands of weapons aimed at one another. What would be the consequences of all-out nuclear war?

Within individual target cities, conditions described earlier for single explosions would prevail. (Most cities, though, would likely be targeted with multiple weapons.) Government estimates suggest that over half of the United States’ population could be killed by the prompt effects of an all-out nuclear war. For those within the appropriate radii of destruction, it would make little difference whether theirs was an isolated explosion or part of a war. But for the survivors in the less damaged areas, the difference could be dramatic.

Consider the injured. Thermal flash burns extend well beyond the 5-psi radius of destruction. A single nuclear explosion might produce 10,000 cases of severe burns requiring specialized medical treatment; in an all-out war there could be several million such cases. Yet the United States has facilities to treat fewer than 2,000 burn cases — virtually all of them in urban areas that would be leveled by nuclear blasts. Burn victims who might be saved, had their injuries resulted from some isolated cause, would succumb in the aftermath of nuclear war. The same goes for fractures, lacerations, missing limbs, crushed skulls, punctured lungs, and myriad other injuries suffered as a result of nuclear blast. Where would be the doctors, the hospitals, the medicines, the equipment needed for their treatment? Most would lie in ruin, and those that remained would be inadequate to the overwhelming numbers of injured. Again, many would die whom modern medicine could normally save.

A single nuclear explosion might produce 10,000 cases of severe burns requiring specialized medical treatment; in an all-out war there could be several million such cases.

In an all-out war, lethal fallout would cover much of the United States. Survivors could avoid fatal radiation exposure only when sheltered with adequate food, water, and medical supplies. Even then, millions would be exposed to radiation high enough to cause lowered disease resistance and greater incidence of subsequent fatal cancer. Lowered disease resistance could lead to death from everyday infections in a population deprived of adequate medical facilities. And the spread of diseases from contaminated water supplies, nonexistent sanitary facilities, lack of medicines, and the millions of dead could reach epidemic proportions. Small wonder that the international group Physicians for Social Responsibility has called nuclear war “the last epidemic.”

Attempts to contain damage to cities, suburbs, and industries would suffer analogously to the treatment of injured people. Firefighting equipment, water supplies, electric power, heavy equipment, fuel supplies, and emergency communications would be gone. Transportation into and out of stricken cities would be blocked by debris. The scarcity of radiation-monitoring equipment and of personnel trained to operate it would make it difficult to know where emergency crews could safely work. Most of all, there would be no healthy neighboring cities to call on for help; all would be crippled in an all-out war.

Is Nuclear War Survivable?

We’ve noted that more than half the United States’ population might be killed outright in an all-out nuclear war. What about the survivors?

Recent studies have used detailed three-dimensional, block-by-block urban terrain models to study the effects of 10-kiloton detonations on Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. The results settle an earlier controversy about whether survivors should evacuate or shelter in place: Staying indoors for 48 hours after a nuclear blast is now recommended. That time allows fallout levels to decay by a factor of 100. Furthermore, buildings between a survivor and the blast can block the worst of the fallout, and going deep inside an urban building can lower fallout levels still further. The same shelter-in-place arguments apply to survivors in the non-urban areas blanketed by fallout.

These new studies, however, consider only single detonations as might occur in a terrorist or rogue attack. In considering all-out nuclear war, we have to ask a further question: Then what?

Individuals might survive for a while, but what about longer term, and what about society as a whole? Extreme and cooperative efforts would be needed for long-term survival, but would the shocked and weakened survivors be up to those efforts? How would individuals react to watching their loved ones die of radiation sickness or untreated injuries? Would an “everyone for themselves” attitude prevail, preventing the cooperation necessary to rebuild society? How would residents of undamaged rural areas react to the streams of urban refugees flooding their communities? What governmental structures could function in the postwar climate? How could people know what was happening throughout the country? Would international organizations be able to cope?

Staying indoors for 48 hours after a nuclear blast is now recommended. That time allows fallout levels to decay by a factor of 100.

Some students of nuclear war see postwar society in a race against time. An all-out war would have destroyed much of the nation’s productive capacity and would have killed many of the experts who could help guide social and physical reconstruction. The war also would have destroyed stocks of food and other materials needed for survival.

On the other hand, the remaining supplies would have to support only the much smaller postwar population. The challenge to the survivors would be to establish production of food and other necessities before the supplies left from before the war were exhausted. Could the war-shocked survivors, their social and governmental structure shattered, meet that challenge? That is a very big nuclear question — so big that it’s best left unanswered, since only an all-out nuclear war could decide it definitively.

Climatic Effects

A large-scale nuclear war would pump huge quantities of chemicals and dust into the upper atmosphere. Humanity was well into the nuclear age before scientists took a good look at the possible consequences of this. What they found was not reassuring.

The upper atmosphere includes a layer enhanced in ozone gas, an unusual form of oxygen that vigorously absorbs the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation. In the absence of this ozone layer , more ultraviolet radiation would reach Earth’s surface, with a variety of harmful effects. A nuclear war would produce huge quantities of ozone-consuming chemicals, and studies suggest that even a modest nuclear exchange would result in unprecedented increases in ultraviolet exposure. Marine life might be damaged by the increased ultraviolet radiation, and humans could receive blistering sunburns. More UV radiation would also lead to a greater incidence of fatal skin cancers and to general weakening of the human immune system.

Even more alarming is the fact that soot from the fires of burning cities after a nuclear exchange would be injected high into the atmosphere. A 1983 study by Richard Turco, Carl Sagan, and others (the so-called TTAPS paper) shocked the world with the suggestion that even a modest nuclear exchange — as few as 100 warheads — could trigger drastic global cooling as airborne soot blocked incoming sunlight. In its most extreme form, this nuclear winter hypothesis raised the possibility of extinction of the human species. (This is not the first dust-induced extinction pondered by science. Current thinking holds that the dinosaurs went extinct as a result of climate change brought about by atmospheric dust from an asteroid impact; indeed, that hypothesis helped prompt the nuclear winter research.)

The original nuclear winter study used a computer model that was unsophisticated compared to present-day climate models, and it spurred vigorous controversy among atmospheric scientists. Although not the primary researcher on the publication, Sagan lent his name in order to publicize the work. Two months before Science would publish the paper, he decided to introduce the results in the popular press. This backfired, as Sagan was derided by hawkish physicists like Edward Teller who had a stake in perpetuating the myth that nuclear war could be won and the belief that a missile defense system could protect the United States from nuclear attack. Teller called Sagan an “excellent propagandist” and suggested that the concept of nuclear winter was “highly speculative.” The damage was done, and many considered the nuclear winter phenomenon discredited.

But research on nuclear winter continued. Recent studies with modern climate models show that an all-out nuclear war between the United States and Russia, even with today’s reduced arsenals, could put over 150 million tons of smoke and soot into the upper atmosphere. That’s roughly the equivalent of all the garbage the U.S. produces in a year! The result would be a drop in global temperature of some 8°C (more than the difference between today’s temperature and the depths of the last ice age), and even after a decade the temperature would have recovered only 4°C. In the world’s “breadbasket” agricultural regions, the temperature could remain below freezing for a year or more, and precipitation would drop by 90 percent. The effect on the world’s food supply would be devastating.

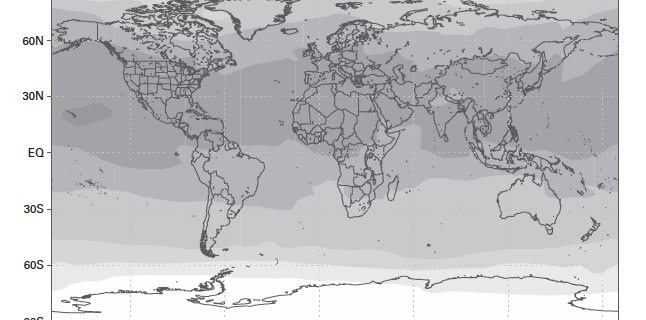

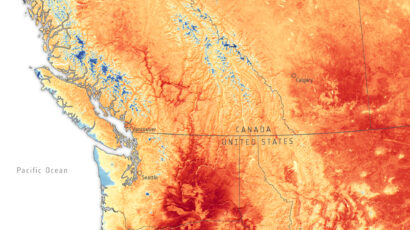

Even a much smaller nuclear exchange could have catastrophic climate consequences. The research cited above also suggests that a nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan, involving 100 Hiroshima-sized weapons, would shorten growing seasons and threaten annual monsoon rains, jeopardizing the food supply of a billion people. The image below shows the global picture one month after this hypothetical 100-warhead nuclear exchange.

Nuclear weapons have devastating effects. Destructive blast effects extend miles from the detonation point of a typical nuclear weapon, and lethal fallout may blanket communities hundreds of miles downwind of a single nuclear explosion. An all-out nuclear war would leave survivors with few means of recovery, and could lead to a total breakdown of society. Fallout from an all-out war would expose most of the belligerent nations’ surviving populations to radiation levels ranging from harmful to fatal. And the effects of nuclear war would extend well beyond the warring nations, possibly including climate change severe enough to threaten much of the planet’s human population.

Debate about national and global effects of nuclear war continues, and the issues are unlikely to be decided conclusively without the unfortunate experiment of an actual nuclear war. But enough is known about nuclear war’s possible effects that there is near universal agreement on the need to avoid them. As the great science communicator and astronomer Carl Sagan once said, “It’s elementary planetary hygiene to clean the world of these nuclear weapons.” But can we eliminate nuclear weapons? Should we? What risks might such elimination entail? Those are the real issues in the ongoing debates about the future of nuclear weaponry.

Richard Wolfson is Benjamin F. Wissler Professor of Physics at Middlebury College. Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress is Scientist-in-Residence at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. This article is excerpted from their book “ Nuclear Choices for the Twenty-First Century: A Citizen’s Guide. “

air burst A nuclear explosion detonated at an altitude—typically, thousands of feet—that maximizes blast damage. Because its fireball never touches the ground, an air burst produces less radioactive fallout than a ground burst.

blast wave An abrupt jump in air pressure that propagates outward from a nuclear explosion, damaging or destroying whatever it encounters.

direct radiation Nuclear radiation produced in the actual detonation of a nuclear weapon and constituting the most immediate effect on the surrounding environment.

electromagnetic pulse (EMP) An intense burst of radio waves produced by a high-altitude nuclear explosion, capable of damaging electronic equipment over thousands of miles.

fallout Radioactive material, mostly fission products, released into the environment by nuclear explosions.

fireball A mass of air surrounding a nuclear explosion and heated to luminous temperatures.

firestorm A massive fire formed by coalescence of numerous smaller fires.

ground burst A nuclear explosion detonated at ground level, producing a crater and significant fallout but less widespread damage than an air burst.

nuclear difference Phrase we use to describe the roughly million-fold difference in energy released in nuclear reactions versus chemical reactions.

nuclear winter A substantial reduction in global temperature that might result from soot injected into the atmosphere during a nuclear war.

overpressure Excess air pressure encountered in the blast wave of a nuclear explosion. Overpressure of a few pounds per square inch is sufficient to destroy typical wooden houses.

radius of destruction The distance from a nuclear blast within which destruction is near total, often taken as the zone of 5-pound-per-square-inch overpressure.

thermal flash An intense burst of heat radiation in the seconds following a nuclear explosion. The thermal flash of a large weapon can ignite fires and cause third-degree burns tens of miles from the explosion.

Read the May magazine issue on food and climate change

Nowhere to hide

How a nuclear war would kill you — and almost everyone else.

Simulation of soot injected into the atmosphere after a nuclear war between India and Pakistan. (Courtesy Max Tegmark / Future of Life Institute )

October 20, 2022

By François Diaz-Maurin

Design by Thomas Gaulkin

This summer, the New York City Emergency Management department released a new public service announcement on nuclear preparedness, instructing New Yorkers about what to do during a nuclear attack. The 90-second video starts with a woman nonchalantly announcing the catastrophic news: “So there’s been a nuclear attack. Don’t ask me how or why, just know that the big one has hit.” Then the PSA video advises New Yorkers on what to do in case of a nuclear attack: Get inside, stay inside, and stay tuned to media and governmental updates.

But nuclear preparedness works better if you are not in the blast radius of a nuclear attack. Otherwise, there’s no going into your house and closing your doors because the house will be gone . Now imagine there have been hundreds of those “big ones.” That’s what even a “small” nuclear war would include. If you are lucky not to be within the blast radius of one of those, it may not ruin your day, but soon enough, it will ruin your whole life.

Effects of a single nuclear explosion

Any nuclear explosion creates radiation, heat, and blast effects that will result in many quick fatalities.

Direct radiation is the most immediate effect of the detonation of a nuclear weapon. It is produced by the nuclear reactions inside the bomb and comes mainly in the form of gamma rays and neutrons.

Direct radiation lasts less than a second, but its lethal level can extend over a mile in all directions from the detonation point of a modern-day nuclear weapon with an explosive yield equal to the effect of several hundred kilotons of TNT.

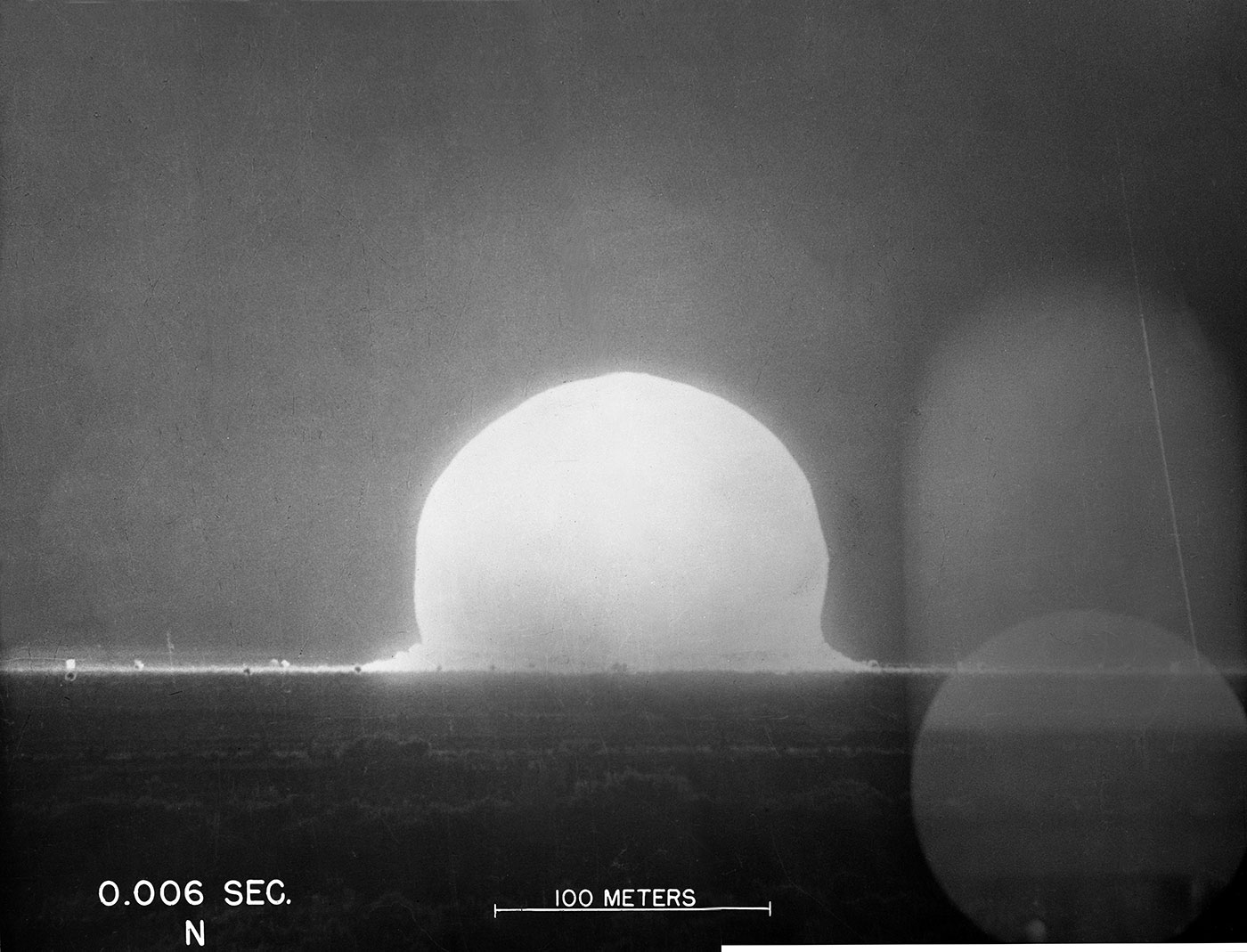

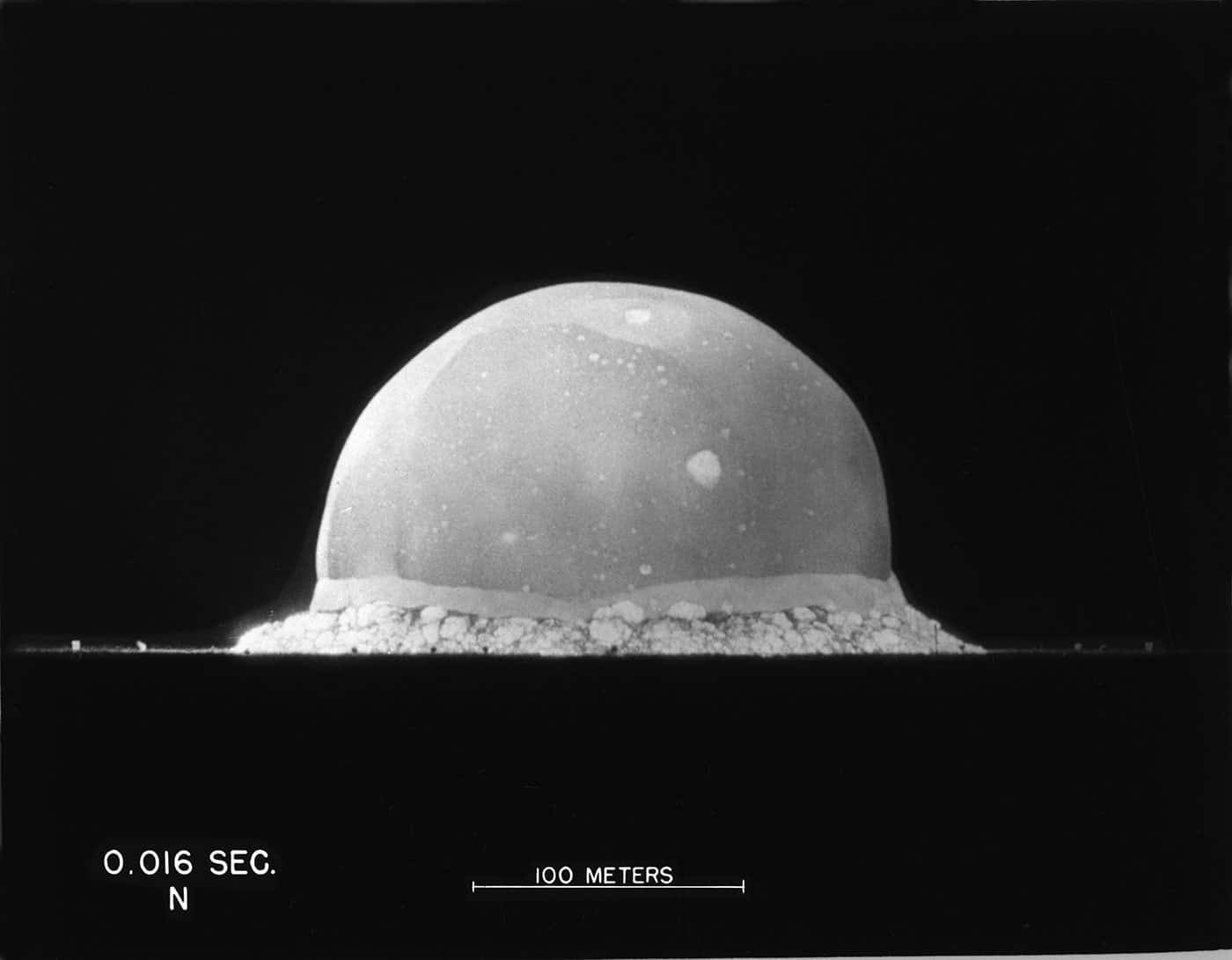

Photos from the first second of the Trinity test shot, the first nuclear explosion on Earth. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Microseconds into the explosion of a nuclear weapon, energy released in the form of X-rays heats the surrounding environment, forming a fireball of superheated air. Inside the fireball, the temperature and pressure are so extreme that all matter is rendered into a hot plasma of bare nuclei and subatomic particles, as is the case in the Sun’s multi-million-degree core.

The fireball following the airburst explosion of a 300-kiloton nuclear weapon—like the W87 thermonuclear warhead deployed on the Minuteman III missiles currently in service in the US nuclear arsenal—can grow to more than 600 meters (2,000 feet) in diameter and stays blindingly luminous for several seconds, before its surface cools.

The light radiated by the fireball’s heat—accounting for more than one-third of the thermonuclear weapon’s explosive energy—will be so intense that it ignites fires and causes severe burns at great distances. The thermal flash from a 300-kiloton nuclear weapon could cause first-degree burns as far as 13 kilometers (8 miles) from ground zero.

Then comes the blast wave.

The blast wave—which accounts for about half the bomb’s explosive energy—travels initially faster than the speed of sound but slows rapidly as it loses energy by passing through the atmosphere.

Because the radiation superheats the atmosphere around the fireball, air in the surroundings expands and is pushed rapidly outward, creating a shockwave that pushes against anything along its path and has great destructive power.

The destructive power of the blast wave depends on the weapon’s explosive yield and the burst altitude.

Film footage from the Apple 2 / Cue nuclear test shot on May 5, 1955, part of the Operation Teapot series.

An airburst of a 300-kiloton explosion would produce a blast with an overpressure of over 5 pounds per square inch (or 0.3 atmospheres) up to 4.7 kilometers (2.9 miles) from the target. This is enough pressure to destroy most houses, gut skyscrapers, and cause widespread fatalities less than 10 seconds after the explosion.

Radioactive fallout

Shortly after the nuclear detonation has released most of its energy in the direct radiation, heat, and blast, the fireball begins to cool and rise, becoming the head of the familiar mushroom cloud. Within it is a highly-radioactive brew of split atoms, which will eventually begin to drop out of the cloud as it is blown by the wind. Radioactive fallout, a form of delayed radioactivity, will expose post-war survivors to near-lethal doses of ionizing radiation.

As for the blast, the severity of the fallout contamination depends on the fission yield of the bomb and its height of burst. For weapons in the hundreds of kilotons, the area of immediate danger can encompass thousands of square kilometers downwind of the detonation site. Radiation levels will be initially dominated by isotopes of short half-lives, which are the most energetic and so most dangerous to biological systems. The acutely lethal effects from the fallout will last from days to weeks, which is why authorities recommend staying inside for at least 48 hours, to allow radiation levels to decrease.

Because its effects are relatively delayed, estimating casualties from the fallout is difficult; the number of deaths and injuries will depend very much on what actions people take after an explosion. But in the vicinity of an explosion, buildings will be completely collapsed, and survivors will not be able to shelter. Survivors finding themselves less than 460 meters (1,500 feet) from a 300-kiloton nuclear explosion will receive an ionizing radiation dose of 500 Roentgen equivalent man (rem). “It is generally believed that humans exposed to about 500 rem of radiation all at once will likely die without medical treatment,” the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission says .

But at a distance so close to ground zero, a 300-kiloton nuclear explosion would almost certainly burn and crush to death any human being. The higher the nuclear weapon’s yield, the smaller the acute radiation zone is relative to its other immediate effects.

One detonation of a modern-day, 300-kiloton nuclear warhead—that is, a warhead nearly 10 times the power of the atomic bombs detonated at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined—on a city like New York would lead to over one million people dead and about twice as many people with serious injuries in the first 24 hours after the explosion. There would be almost no survivors within a radius of several kilometers from the explosion site.

deaths after 24 hours

Immediate effects of nuclear war

Excerpt from “ Plan A ” a video simulation of an escalatory nuclear war between the United States and Russia. (Alex Glaser / Program on Science and Global Security, Princeton University)

In a nuclear war, hundreds or thousands of detonations would occur within minutes of each other.

Regional nuclear war between India and Pakistan that involved about 100 15-kiloton nuclear weapons launched at urban areas would result in 27 million direct deaths .

deaths from regional war

A global all-out nuclear war between the United States and Russia with over four thousand 100-kiloton nuclear warheads would lead, at minimum, to 360 million quick deaths .* That’s about 30 million people more than the entire US population.

360,000,000

deaths from global war

* This estimate is based on a scenario of an all-out nuclear war between Russia and the United States involving 4,400 100-kiloton weapons under the 2002 Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT) limits, where each country can deploy up to 2,200 strategic warheads. The 2010 New START Treaty further limits the US- and Russian-deployed long-range nuclear forces down to 1,550 warheads. But as the average yield of today’s strategic nuclear forces of Russia and the United States far exceeds 100 kilotons, a full nuclear exchange between the two countries involving around 3,000 weapons likely would result in similar direct casualties and soot emissions.

In an all-out nuclear war between Russia and the United States, the two countries would not limit to shooting nuclear missiles at each other’s homeland but would target some of their weapons at other countries, including ones with nuclear weapons. These countries could launch some or all their weapons in retaliation.

Together, the United Kingdom, China, France, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea currently have an estimated total of over 1,200 nuclear warheads .

As horrific as those statistics are, the tens to hundreds of millions of people dead and injured within the first few days of a nuclear conflict would only be the beginnings of a catastrophe that eventually will encompass the whole world.

Global climatic changes, widespread radioactive contamination, and societal collapse virtually everywhere could be the reality that survivors of a nuclear war would contend with for many decades.

Two years after any nuclear war—small or large—famine alone could be more than 10 times as deadly as the hundreds of bomb blasts involved in the war itself.

The longer-term consequences of nuclear war

The only color photograph of the Trinity nuclear test on July 16, 1945. (Jack Aeby / Los Alamos National Laboratory)

In recent years, in some US military and policy circles, there has been a growing perception that a limited nuclear war can be fought and won. Many experts believe, however, that a limited nuclear war is unlikely to remain limited. What starts with one tactical nuclear strike or a tit-for-tat nuclear exchange between two countries could escalate to an all-out nuclear war ending with the immediate and utter destruction of both countries.

But the catastrophe will not be limited to those two belligerents and their allies.

The long-term regional and global effects of nuclear explosions have been overshadowed in public discussions by the horrific, obvious, local consequences of nuclear explosions. Military planners have also focused on the short-term effects of nuclear explosions because they are tasked with estimating the capabilities of nuclear forces on civilian and military targets. Blast, local radiation fallout, and electromagnetic pulse (an intense burst of radio waves that can damage electronic equipment) are all desired outcomes of the use of nuclear weapons—from a military perspective.

But widespread fires and other global climatic changes resulting from many nuclear explosions may not be accounted for in war plans and nuclear doctrines. These collateral effects are difficult to predict; assessing them requires scientific knowledge that most military planners don’t possess or take into account. Yet, in the few years following a nuclear war, such collateral damage may be responsible for the death of more than half of the human population on Earth.

Global climatic changes

Since the 1980s, as the threat of nuclear war reached new heights, scientists have investigated the long-term, widespread effects of nuclear war on Earth systems. Using a radiative-convective climate model that simulates the vertical profile of atmospheric temperatures, American scientists first showed that a nuclear winter could occur from the smoke produced by the massive forest fires ignited by nuclear weapons after a nuclear war. Two Russian scientists later conducted the first three-dimensional climate modeling showing that global temperatures would drop lower on land than on oceans, potentially causing an agricultural collapse worldwide. Initially contested for its imprecise results due to uncertainties in the scenarios and physical parameters involved, nuclear winter theory is now supported by more sophisticated climate models . While the basic mechanisms of nuclear winter described in the early studies still hold today, most recent calculations have shown that the effects of nuclear war would be more long-lasting and worse than previously thought.

A huge cloud resulting from the massive fires caused by “Little Boy”—the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945—a few hours after the initial explosion. (US Army)

Stratospheric soot injection

The heat and blast from a thermonuclear explosion are so powerful they can initiate large-scale fires in both urban and rural settings. A 300-kiloton detonation in a city like New York or Washington DC could cause a mass fire with a radius of at least 5.6 kilometers (3.5 miles), not altered by any weather conditions. Air in that area would be turned into dust, fire, and smoke.

But a nuclear war will set not just one city on fire , but hundreds of them, all but simultaneously. Even a regional nuclear war—say between India and Pakistan—could lead to widespread firestorms in cities and industrial areas that would have the potential to cause global climatic change , disrupting every form of life on Earth for decades.

Smoke from mass fires after a nuclear war could inject massive amounts of soot into the stratosphere, the Earth’s upper atmosphere. An all-out nuclear war between India and Pakistan, with both countries launching a total of 100 nuclear warheads of an average yield of 15 kilotons, could produce a stratospheric loading of some 5 million tons (or teragrams, Tg) of soot. This is about the mass of the Great Pyramid of Giza, pulverized and turned into superheated dust.

A simulation of the vertically averaged smoke optical depth in the first 54 days after a nuclear war between India and Pakistan. ( Robock et al., Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 2003–2012, 2007 )

But these lower-end estimates date back to the late 2000s. Since then, India and Pakistan have significantly expanded their nuclear arsenals, both in the number of nuclear warheads and yield. By 2025, India and Pakistan could have up to 250 nuclear weapons each, with yields of 12 kilotons on the low end, up to a few hundred kilotons. A nuclear war between India and Pakistan with such arsenals could send up to 47 Tg of soot into the stratosphere.

For comparison, the recent catastrophic forest fires in Canada in 2017 and Australia in 2019 and 2020 produced 0.3 Tg and 1 Tg of smoke respectively. Chemical analysis showed, however, that only a small percentage of the smoke from these fires was pure soot—0.006 and 0.02 Tg respectively. This is because only wood was burning. Urban fires following a nuclear war would produce more smoke, and a higher fraction would be soot. But these two episodes of massive forest fires demonstrated that when smoke is injected into the lower stratosphere, it is heated by sunlight and lofted at high altitudes—10 to 20 kilometers (33,000 to 66,000 feet)—prolonging the time it stays in the stratosphere. This is precisely the mechanism that now allows scientists to better simulate the long-term impacts of nuclear war. With their models, researchers were able to accurately simulate the smoke from these large forest fires, further supporting the mechanisms that cause nuclear winter.

The climatic response from volcanic eruptions also continues to serve as a basis for understanding the long-term impacts of nuclear war. Volcanic blasts typically send ash and dust up into the stratosphere where it reflects sunlight back into space, resulting in the temporary cooling of the Earth’s surface. Likewise , in the theory of nuclear winter, the climatic effects of a massive injection of soot aerosols into the stratosphere from fires following a nuclear war would lead to the heating of the stratosphere, ozone depletion, and cooling at the surface under this cloud. Volcanic eruptions are also useful because their magnitude can match—or even surpass—the level of nuclear explosions. For instance, the 2022 Hunga Tonga’s underwater volcano released an explosive energy of 61 megatons of TNT equivalent —more than the Tsar Bomba, the largest human-made explosion in history with 50 Mt. Its plume reached altitudes up to about 56 kilometers (35 miles), injecting well over 50 Tg —even up to 146 Tg —of water vapor into the stratosphere where it will stay for years. Such a massive injection of stratospheric water could temporarily impact the climate—although differently than soot.

Aerial footage of the 2022 Hunga Tonga volcanic eruption. The vapor plume reached altitudes up to 56 kilometers (35 miles) and injected more than 50 teragrams of water vapor into the stratosphere. (Tonga Geological Services via YouTube )

Since Russia’s war in Ukraine started, President Putin and other Russian officials have made repeated nuclear threats , in an apparent attempt to deter Western countries from any direct military intervention. If Russia were to ever start—voluntarily or accidentally—nuclear war with the United States and other NATO countries, the number of devastating nuclear explosions involved in a full exchange could waft more than 150 Tg of soot into the stratosphere, leading to a nuclear winter that would disrupt virtually all forms of life on Earth over several decades.

Stratospheric soot injections associated with different nuclear war scenarios would lead to a wide variety of major climatic and biogeochemical changes, including transformations of the atmosphere, oceans, and land. Such global climate changes will be more long-lasting than previously thought because models of the 1980s did not adequately represent the stratospheric plume rise. It is now understood that soot from nuclear firestorms would rise much higher into the stratosphere than once imagined, where soot removal mechanisms in the form of “black rains” are slow. Once the smoke is heated by sunlight it can self-loft to altitudes as high as 80 kilometers (50 miles), penetrating the mesosphere.

A simulation of the vertically averaged smoke optical depth in the first 54 days after a nuclear war between Russia and the United States. (Alan Robock)

Changes in the atmosphere

After soot is injected into the upper atmosphere, it can stay there for months to years, blocking some direct sunlight from reaching the Earth’s surface and decreasing temperatures. At high altitudes—20 kilometers (12 miles) and above near the equator and 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) at the poles—the smoke injected by nuclear firestorms would also absorb more radiation from the sun, heating the stratosphere and perturbing stratospheric circulation.

In the stratosphere, the presence of highly absorptive black carbon aerosols would result in considerably enhanced stratospheric temperatures. For instance, in a regional nuclear war scenario that leads to a 5-Tg injection of soot, stratospheric temperatures would remain elevated by 30 degrees Celsius after four years.

The extreme heating observed in the stratosphere would increase the global average loss of the ozone layer—which protects humans and other life on Earth from the severe health and environmental effects of ultraviolet radiation—for the first few years after a nuclear war. Simulations have shown that a regional nuclear war that lasted three days and injected 5 Tg of soot into the stratosphere would reduce the ozone layer by 25 percent globally; recovery would take 12 years. A global nuclear war injecting 150 Tg of stratospheric smoke would cause a 75 percent global ozone loss, with the depletion lasting 15 years.

Changes on land

Soot injection in the stratosphere will lead to changes on the Earth’s surface, including the amount of solar radiation that is received, air temperature, and precipitation.

The loss of the Earth’s protective ozone layer would result in several years of extremely high ultraviolet (UV) light at the surface, a hazard to human health and food production. Most recent estimates indicate that the ozone loss after a global nuclear war would lead to a tropical UV index above 35, starting three years after the war and lasting for four years. The US Environmental Protection Agency considers a UV index of 11 to pose an “extreme” danger; 15 minutes of exposure to a UV index of 12 causes unprotected human skin to experience sunburn. Globally, the average sunlight in the UV-B range would increase by 20 percent. High levels of UV-B radiation are known to cause sunburn, photoaging, skin cancer, and cataracts in humans. They also inhibit the photolysis reaction required for leaf expansion and plant growth.

Smoke lofted into the stratosphere would reduce the amount of solar radiation making it to Earth’s surface, reducing global surface temperatures and precipitation dramatically.

Even a nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan—causing a relatively modest stratospheric loading of 5 Tg of soot—could produce the lowest temperatures on Earth in the past 1,000 years—temperatures below the post-medieval Little Ice Age. A regional nuclear war with 5-Tg stratospheric soot injection would have the potential to make global average temperatures drop by 1 degree Celsius.

Even though their nuclear arsenals have been cut in size and average yield since the end of the Cold War, a nuclear exchange between the United States and Russia would still likely initiate a much more severe nuclear winter, with much of the northern hemisphere facing below-freezing temperatures even during the summer. A global nuclear war that injected 150 Tg of soot into the stratosphere could make temperatures drop by 8 degrees Celsius—3 degrees lower than Ice Age values.

In any nuclear war scenario, the temperature changes would have their greatest effect on mid- and high-latitude agriculture, by reducing the length of the crop season and the temperature even during that season. Below-freezing temperatures could also lead to a significant expansion of sea ice and terrestrial snowpack, causing food shortages and affecting shipping to crucial ports where sea ice is not now a factor.

Global average precipitation after a nuclear war would also drop significantly because the lower amounts of solar radiation reaching the surface would reduce temperatures and water evaporation rates. The precipitation decrease would be the greatest in the tropics . For instance, even a 5-Tg soot injection would lead to a 40 percent precipitation decrease in the Asian monsoon region. South America and Africa would also experience large drops in rainfall.

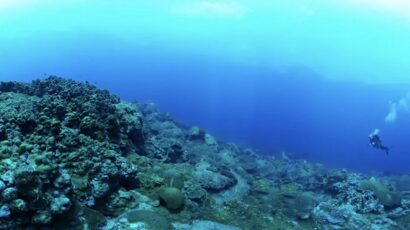

Changes in the ocean

The longest-lasting consequences of any nuclear war would involve oceans . Regardless of the location and magnitude of a nuclear war, the smoke from the resulting firestorms would quickly reach the stratosphere and be dispersed globally, where it would absorb sunlight and reduce the solar radiation to the ocean surface. The ocean surface would respond more slowly to changes in radiation than the atmosphere and land due to its higher specific heat capacity (i.e., the quantity of heat needed to raise the temperature per unit of mass).

Global ocean temperature decrease will be the greatest starting three to four years after a nuclear war, dropping by approximately 3.5 degrees Celsius for an India-Pakistan war (that injected 47 Tg of smoke into the stratosphere) and six degrees Celsius for a global US-Russia war (150 Tg). Once cooled, the ocean will take even more time to return to its pre-war temperatures, even after the soot has disappeared from the stratosphere and solar radiation returns to normal levels. The delay and duration of the changes will increase linearly with depth. Abnormally low temperatures are likely to persist for decades near the surface, and hundreds of years or longer at depth. For a global nuclear war (150 Tg), changes in ocean temperature to the Arctic sea-ice are likely to last thousands of years—so long that researchers talk of a “nuclear Little Ice Age.”

Because of the dropping solar radiation and temperature on the ocean surface, marine ecosystems would be highly disrupted both by the initial perturbation and by the new, long-lasting ocean state. This will result in global impacts on ecosystem services, such as fisheries. For instance, the marine net primary production (a measure of the new growth of marine algae, which makes up the base of the marine food web) would decline sharply after any nuclear war. In a US-Russia scenario (150 Tg), the global marine net primary production would be cut almost by half in the months after the war and would remain reduced by 20 to 40 percent for over 4 years, with the largest decreases being in the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans.

Impacts on food production

Changes in the atmosphere, surface, and oceans following a nuclear war will have massive and long-term consequences on global agricultural production and food availability. Agriculture responds to the length of growing seasons, the temperature during the growing season, light levels, precipitation, and other factors. A nuclear war will significantly alter all of those factors, on a global scale for years to decades.

Using new climate, crop, and fishery models, researchers have now demonstrated that soot injections larger than 5 Tg would lead to mass food shortages in almost all countries, although some will be at greater risk of famine than others. Globally, livestock production and fishing would be unable to compensate for reduced crop output. After a nuclear war, and after stored food is consumed, the total food calories available in each nation will drop dramatically, putting millions at risk of starvation or undernourishment. Mitigation measures—shifts in production and consumption of livestock food and crops, for example—would not be sufficient to compensate for the global loss of available calories.

The aforementioned food production impacts do not account for the long-term direct impacts of radioactivity on humans or the widespread radioactive contamination of food that could follow a nuclear war. International trade of food products could be greatly reduced or halted as countries hoard domestic supplies. But even assuming a heroic action of altruism by countries whose food systems are less affected, trade could be disrupted by another effect of the war: sea ice.

Cooling of the ocean’s surface would lead to an expansion of sea ice in the first years after a nuclear war, when food shortages would be highest. This expansion would affect shipping into crucial ports in regions where sea ice is not currently experienced, such as the Yellow Sea.

Post-nuclear famine

Number of people and percentage of the population who could die from starvation two years after a nuclear war. Regional nuclear war scenario corresponds to 5Tg of soot produced by 100 15-kiloton nuclear weapons launched between India and Pakistan. Large-scale nuclear war scenario corresponds to 150Tg of soot produced by 4,400 100-kiloton nuclear weapons launched between Russia and the United States. (Source: Xia et al. Nature Food 3, no. 8 (2022): 586-596 .)

Regional war

The impacts of nuclear war on agricultural food systems would have dire consequences for most humans who survive the war and its immediate effects.

The overall global consequences of nuclear war—including both short-term and long-term impacts—would be even more horrific causing hundreds of millions—even billions—of people to starve to death.

If this ↑ red line represents an estimate of deaths from one 300-kiloton nuclear bomb detonated over New York City ...

... then these ↑ are the direct deaths from an India-Pakistan nuclear war with an exchange of one hundred 15-kiloton warheads ...

... these are the direct deaths from a global nuclear war involving 4,400 100-kiloton warheads ...

... and this is how many people might eventually die from famine two years after that global nuclear war ends ...

5,341,000,000

Two years after a nuclear war ends, nearly everyone might face starvation.

There is nowhere to hide.

François Diaz-Maurin ( @francoisdm ) is the associate editor for nuclear affairs at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists .

Thomas Gaulkin ( @ThomasGaulkin ) is multimedia editor of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists .

Jump to comments ↓

References & Acknowledgments

This article is based on the work of many researchers who have studied the impacts of nuclear war since the 1980s. The author wishes to thank in particular Alex Glaser from Princeton University, Alan Robock from Rutgers University, and Alex Wellerstein from the Stevens Institute of Technology.

- Aleksandrov, Vladimir V., and Georgiy L. Stenchikov. “On the modelling of the climatic consequences of the nuclear war.” In The Proceeding on Applied Mathematics (1983), 21 pp. Moscow: Computing Centre, USSR Academy of Sciences. http://climate.envsci.rutgers.edu/pdf/AleksandrovStenchikov.pdf

- Bardeen, Charles G., Douglas E. Kinnison, Owen B. Toon, Michael J. Mills, Francis Vitt, Lili Xia, Jonas Jägermeyr et al. "Extreme ozone loss following nuclear war results in enhanced surface ultraviolet radiation." Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 126, no. 18 (2021): e2021JD035079. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2021JD035079

- Bele, Jean. M. “Nuclear Weapons Effects Simulator”, Nuclear Weapons Education Project, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. https://nuclearweaponsedproj.mit.edu/Node/103

- Coupe, Joshua, Charles G. Bardeen, Alan Robock, and Owen B. Toon. "Nuclear winter responses to nuclear war between the United States and Russia in the whole atmosphere community climate model version 4 and the Goddard Institute for Space Studies ModelE." Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 124, no. 15 (2019): 8522-8543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2019JD030509

- Eden, Lynn. Whole world on fire: Organizations, knowledge, and nuclear weapons devastation . Cornell University Press, 2004.

- Glaser, Alex. “Plan A”. Program on Science & Global Security, Princeton University. https://sgs.princeton.edu/the-lab/plan-a

- Harrison, Cheryl S., Tyler Rohr, Alice DuVivier, Elizabeth A. Maroon, Scott Bachman, Charles G. Bardeen, Joshua Coupe et al. "A new ocean state after nuclear war." AGU Advances 3, no. 4 (2022): e2021AV000610. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021AV000610

- Kataria, Sunita, Anjana Jajoo, and Kadur N. Guruprasad. "Impact of increasing Ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation on photosynthetic processes." Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 137 (2014): 55-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.02.004

- Kristensen, Hans M., and Matt Korda. “Russian nuclear weapons, 2022.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 78, no. 2 (2022a): 98-121. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2022.2038907

- Kristensen, Hans M., and Matt Korda. “United States nuclear weapons, 2022.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 78, no. 3 (2022b): 162-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2022.2062943

- MacKie, R. M. "Effects of ultraviolet radiation on human health." Radiation Protection Dosimetry 91, no. 1-3 (2000): 15-18. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a033186

- Millan, Luis, Michelle L. Santee, Alyn Lambert, Nathaniel J. Livesey, Frank Werner, Michael J. Schwartz, Hugh Charles Pumphrey et al. "The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai Hydration of the Stratosphere." (2022). https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL099381

- Mills, Michael J., Owen B. Toon, Richard P. Turco, Douglas E. Kinnison, and Rolando R. Garcia. "Massive global ozone loss predicted following regional nuclear conflict." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, no. 14 (2008): 5307-5312. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0710058105

- Robock, Alan. "Volcanic eruptions and climate." Reviews of geophysics 38, no. 2 (2000): 191-219. https://doi.org/10.1029/1998RG000054

- Robock, Alan. "The latest on volcanic eruptions and climate." Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 94, no. 35 (2013): 305-306. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013EO350001

- Robock, Alan, Luke Oman, and Georgiy L. Stenchikov. "Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences." Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 112, no. D13 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD008235

- Robock, Alan, Luke Oman, Georgiy L. Stenchikov, Owen B. Toon, Charles Bardeen, and Richard P. Turco. "Climatic consequences of regional nuclear conflicts." Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 7, no. 8 (2007): 2003-2012. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-2003-2007

- Robock, Alan, and Owen B. Toon. "Local nuclear war, global suffering." Scientific American 302, no. 1 (2010): 74-81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26001848

- Rogers, Jessica, Hans M. Kristensen, and Matt Korda. “The long view: strategic arms control after the New START Treaty.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists . Forthcoming November 2022.

- Teller, Edward. "Widespread after-effects of nuclear war." Nature 310, no. 5979 (1984): 621-624. https://doi.org/10.1038/310621a0

- Toon, Owen B., Charles G. Bardeen, Alan Robock, Lili Xia, Hans Kristensen, Matthew McKinzie, Roy J. Peterson, Cheryl S. Harrison, Nicole S. Lovenduski, and Richard P. Turco. "Rapidly expanding nuclear arsenals in Pakistan and India portend regional and global catastrophe." Science Advances 5, no. 10 (2019): eaay5478. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay5478

- Toon, Owen B., Alan Robock, and Richard P. Turco. "Environmental consequences of nuclear war." Physics Today 61, no. 12 (2008): 37. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3047679

- Toon, Owen B., Richard P. Turco, Alan Robock, Charles Bardeen, Luke Oman, and Georgiy L. Stenchikov. "Atmospheric effects and societal consequences of regional scale nuclear conflicts and acts of individual nuclear terrorism." Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 7, no. 8 (2007): 1973-2002. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-7-1973-2007

- Turco, Richard P., Owen B. Toon, Thomas P. Ackerman, James B. Pollack, and Carl Sagan. "Nuclear winter: Global consequences of multiple nuclear explosions." Science 222, no. 4630 (1983): 1283-1292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.222.4630.1283

- Vömel, Holger, Stephanie Evan, and Matt Tully. "Water vapor injection into the stratosphere by Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai." Science 377, no. 6613 (2022): 1444-1447. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abq2299

- Wellerstein, Alex. “NUKEMAP v.2.72”. Available at: https://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/

- Wolfson, Richard, and Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress. “13: Effects of Nuclear Weapons.” In Nuclear Choices for the Twenty-First Century: A Citizen's Guide . (MIT Press, 2021): 281-304. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11993.003.0017

- Xia, Lili, Alan Robock, Kim Scherrer, Cheryl S. Harrison, Benjamin Leon Bodirsky, Isabelle Weindl, Jonas Jägermeyr, Charles G. Bardeen, Owen B. Toon, and Ryan Heneghan. "Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection." Nature Food 3, no. 8 (2022): 586-596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00573-0

- Yu, Pengfei, Owen B. Toon, Charles G. Bardeen, Yunqian Zhu, Karen H. Rosenlof, Robert W. Portmann, Troy D. Thornberry et al. "Black carbon lofts wildfire smoke high into the stratosphere to form a persistent plume." Science 365, no. 6453 (2019): 587-590. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax1748

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows, nuclear threats are real, present, and dangerous

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important . In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: blast wave , climate impacts of nuclear warfare , famine , food insecurity , nuclear war , nuclear weapons , nuclear winter , radioactive fallout , societal collapse , thermonuclear weapons Topics: Investigative Reporting , Multimedia , Nuclear Risk , Nuclear Weapons

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]

I must say that I am SICKENED BY THE FACT THAT WE NEED WEAPONS LIKE THESE!!! I WISH THERE WAS A TREATY TO DO AWAY WITH ALL NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND ALL DATA PERTAINING TO NUKES!!!!

The data you need to keep. You would not want to forget just how deadly they are would you?

Still…. You got to laugh eh!

What is there to laugh about?

I love this comment.

Nowhere to hide is bs. There are no nuclear target zones in South America or Africa.

good. you would die of starvation then.

New Zealand and Australia are both shown as having minimal starvation effects. While Australia is well within the worst case scenarios of the Soot effects New Zealand is on the edge of even the worst case extrapolations of these effects. Australia will get hit by Boat refugees, but again New Zealand will get minimal “boat refugees”. Quite simply any attempt to get to New Zealand in a half-arsed overloaded boat will see everyone drown. The only boats like to make it are well supplied vessels carrying modest numbers of people.

Think also about collapsing supply chains. I’m in Canberra, and there’s no likely nuclear target anywhere near here. In a major US-Russia/China nuclear war, the main challenge Australia will face is feeding its own population, plus large numbers of refugees fleeing south from the equatorial regions – plus climate effects. But when supply chains collapse – we lose fuel so can’t get food to the market – and maybe our electric grids collapse too. Its grim here – maybe not to the same extent as the northern hemisphere – but still it won’t be easy for us.

Try reading the article.

If nuclear war happens I would prefer to die in the initial detonation than deal with the slow death of the aftermath. If I survived the initial blast I would probably just end it and not have to deal with the suffering.

Good. The rest of us will need your resources and you lack mentality to survive anyway.

Your Mom’s basement isn’t the bunker you think it is.