Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking

(10 reviews)

Matthew Van Cleave, Lansing Community College

Copyright Year: 2016

Publisher: Matthew J. Van Cleave

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by "yusef" Alexander Hayes, Professor, North Shore Community College on 6/9/21

Formal and informal reasoning, argument structure, and fallacies are covered comprehensively, meeting the author's goal of both depth and succinctness. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

Formal and informal reasoning, argument structure, and fallacies are covered comprehensively, meeting the author's goal of both depth and succinctness.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The book is accurate.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

While many modern examples are used, and they are helpful, they are not necessarily needed. The usefulness of logical principles and skills have proved themselves, and this text presents them clearly with many examples.

Clarity rating: 5

It is obvious that the author cares about their subject, audience, and students. The text is comprehensible and interesting.

Consistency rating: 5

The format is easy to understand and is consistent in framing.

Modularity rating: 5

This text would be easy to adapt.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The organization is excellent, my one suggestion would be a concluding chapter.

Interface rating: 5

I accessed the PDF version and it would be easy to work with.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

The writing is excellent.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

This is not an offensive text.

Reviewed by Susan Rottmann, Part-time Lecturer, University of Southern Maine on 3/2/21

I reviewed this book for a course titled "Creative and Critical Inquiry into Modern Life." It won't meet all my needs for that course, but I haven't yet found a book that would. I wanted to review this one because it states in the preface that it... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

I reviewed this book for a course titled "Creative and Critical Inquiry into Modern Life." It won't meet all my needs for that course, but I haven't yet found a book that would. I wanted to review this one because it states in the preface that it fits better for a general critical thinking course than for a true logic course. I'm not sure that I'd agree. I have been using Browne and Keeley's "Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking," and I think that book is a better introduction to critical thinking for non-philosophy majors. However, the latter is not open source so I will figure out how to get by without it in the future. Overall, the book seems comprehensive if the subject is logic. The index is on the short-side, but fine. However, one issue for me is that there are no page numbers on the table of contents, which is pretty annoying if you want to locate particular sections.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

I didn't find any errors. In general the book uses great examples. However, they are very much based in the American context, not for an international student audience. Some effort to broaden the chosen examples would make the book more widely applicable.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

I think the book will remain relevant because of the nature of the material that it addresses, however there will be a need to modify the examples in future editions and as the social and political context changes.

Clarity rating: 3

The text is lucid, but I think it would be difficult for introductory-level students who are not philosophy majors. For example, in Browne and Keeley's "Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking," the sub-headings are very accessible, such as "Experts cannot rescue us, despite what they say" or "wishful thinking: perhaps the biggest single speed bump on the road to critical thinking." By contrast, Van Cleave's "Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking" has more subheadings like this: "Using your own paraphrases of premises and conclusions to reconstruct arguments in standard form" or "Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives." If students are prepared very well for the subject, it would work fine, but for students who are newly being introduced to critical thinking, it is rather technical.

It seems to be very consistent in terms of its terminology and framework.

Modularity rating: 4

The book is divided into 4 chapters, each having many sub-chapters. In that sense, it is readily divisible and modular. However, as noted above, there are no page numbers on the table of contents, which would make assigning certain parts rather frustrating. Also, I'm not sure why the book is only four chapter and has so many subheadings (for instance 17 in Chapter 2) and a length of 242 pages. Wouldn't it make more sense to break up the book into shorter chapters? I think this would make it easier to read and to assign in specific blocks to students.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The organization of the book is fine overall, although I think adding page numbers to the table of contents and breaking it up into more separate chapters would help it to be more easily navigable.

Interface rating: 4

The book is very simply presented. In my opinion it is actually too simple. There are few boxes or diagrams that highlight and explain important points.

The text seems fine grammatically. I didn't notice any errors.

The book is written with an American audience in mind, but I did not notice culturally insensitive or offensive parts.

Overall, this book is not for my course, but I think it could work well in a philosophy course.

Reviewed by Daniel Lee, Assistant Professor of Economics and Leadership, Sweet Briar College on 11/11/19

This textbook is not particularly comprehensive (4 chapters long), but I view that as a benefit. In fact, I recommend it for use outside of traditional logic classes, but rather interdisciplinary classes that evaluate argument read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

This textbook is not particularly comprehensive (4 chapters long), but I view that as a benefit. In fact, I recommend it for use outside of traditional logic classes, but rather interdisciplinary classes that evaluate argument

To the best of my ability, I regard this content as accurate, error-free, and unbiased

The book is broadly relevant and up-to-date, with a few stray temporal references (sydney olympics, particular presidencies). I don't view these time-dated examples as problematic as the logical underpinnings are still there and easily assessed

Clarity rating: 4

My only pushback on clarity is I didn't find the distinction between argument and explanation particularly helpful/useful/easy to follow. However, this experience may have been unique to my class.

To the best of my ability, I regard this content as internally consistent

I found this text quite modular, and was easily able to integrate other texts into my lessons and disregard certain chapters or sub-sections

The book had a logical and consistent structure, but to the extent that there are only 4 chapters, there isn't much scope for alternative approaches here

No problems with the book's interface

The text is grammatically sound

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

Perhaps the text could have been more universal in its approach. While I didn't find the book insensitive per-se, logic can be tricky here because the point is to evaluate meaningful (non-trivial) arguments, but any argument with that sense of gravity can also be traumatic to students (abortion, death penalty, etc)

No additional comments

Reviewed by Lisa N. Thomas-Smith, Graduate Part-time Instructor, CU Boulder on 7/1/19

The text covers all the relevant technical aspects of introductory logic and critical thinking, and covers them well. A separate glossary would be quite helpful to students. However, the terms are clearly and thoroughly explained within the text,... read more

The text covers all the relevant technical aspects of introductory logic and critical thinking, and covers them well. A separate glossary would be quite helpful to students. However, the terms are clearly and thoroughly explained within the text, and the index is very thorough.

The content is excellent. The text is thorough and accurate with no errors that I could discern. The terminology and exercises cover the material nicely and without bias.

The text should easily stand the test of time. The exercises are excellent and would be very helpful for students to internalize correct critical thinking practices. Because of the logical arrangement of the text and the many sub-sections, additional material should be very easy to add.

The text is extremely clearly and simply written. I anticipate that a diligent student could learn all of the material in the text with little additional instruction. The examples are relevant and easy to follow.

The text did not confuse terms or use inconsistent terminology, which is very important in a logic text. The discipline often uses multiple terms for the same concept, but this text avoids that trap nicely.

The text is fairly easily divisible. Since there are only four chapters, those chapters include large blocks of information. However, the chapters themselves are very well delineated and could be easily broken up so that parts could be left out or covered in a different order from the text.

The flow of the text is excellent. All of the information is handled solidly in an order that allows the student to build on the information previously covered.

The PDF Table of Contents does not include links or page numbers which would be very helpful for navigation. Other than that, the text was very easy to navigate. All the images, charts, and graphs were very clear

I found no grammatical errors in the text.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

The text including examples and exercises did not seem to be offensive or insensitive in any specific way. However, the examples included references to black and white people, but few others. Also, the text is very American specific with many examples from and for an American audience. More diversity, especially in the examples, would be appropriate and appreciated.

Reviewed by Leslie Aarons, Associate Professor of Philosophy, CUNY LaGuardia Community College on 5/16/19

This is an excellent introductory (first-year) Logic and Critical Thinking textbook. The book covers the important elementary information, clearly discussing such things as the purpose and basic structure of an argument; the difference between an... read more

This is an excellent introductory (first-year) Logic and Critical Thinking textbook. The book covers the important elementary information, clearly discussing such things as the purpose and basic structure of an argument; the difference between an argument and an explanation; validity; soundness; and the distinctions between an inductive and a deductive argument in accessible terms in the first chapter. It also does a good job introducing and discussing informal fallacies (Chapter 4). The incorporation of opportunities to evaluate real-world arguments is also very effective. Chapter 2 also covers a number of formal methods of evaluating arguments, such as Venn Diagrams and Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives, but to my mind, it is much more thorough in its treatment of Informal Logic and Critical Thinking skills, than it is of formal logic. I also appreciated that Van Cleave’s book includes exercises with answers and an index, but there is no glossary; which I personally do not find detracts from the book's comprehensiveness.

Overall, Van Cleave's book is error-free and unbiased. The language used is accessible and engaging. There were no glaring inaccuracies that I was able to detect.

Van Cleave's Textbook uses relevant, contemporary content that will stand the test of time, at least for the next few years. Although some examples use certain subjects like former President Obama, it does so in a useful manner that inspires the use of critical thinking skills. There are an abundance of examples that inspire students to look at issues from many different political viewpoints, challenging students to practice evaluating arguments, and identifying fallacies. Many of these exercises encourage students to critique issues, and recognize their own inherent reader-biases and challenge their own beliefs--hallmarks of critical thinking.

As mentioned previously, the author has an accessible style that makes the content relatively easy to read and engaging. He also does a suitable job explaining jargon/technical language that is introduced in the textbook.

Van Cleave uses terminology consistently and the chapters flow well. The textbook orients the reader by offering effective introductions to new material, step-by-step explanations of the material, as well as offering clear summaries of each lesson.

This textbook's modularity is really quite good. Its language and structure are not overly convoluted or too-lengthy, making it convenient for individual instructors to adapt the materials to suit their methodological preferences.

The topics in the textbook are presented in a logical and clear fashion. The structure of the chapters are such that it is not necessary to have to follow the chapters in their sequential order, and coverage of material can be adapted to individual instructor's preferences.

The textbook is free of any problematic interface issues. Topics, sections and specific content are accessible and easy to navigate. Overall it is user-friendly.

I did not find any significant grammatical issues with the textbook.

The textbook is not culturally insensitive, making use of a diversity of inclusive examples. Materials are especially effective for first-year critical thinking/logic students.

I intend to adopt Van Cleave's textbook for a Critical Thinking class I am teaching at the Community College level. I believe that it will help me facilitate student-learning, and will be a good resource to build additional classroom activities from the materials it provides.

Reviewed by Jennie Harrop, Chair, Department of Professional Studies, George Fox University on 3/27/18

While the book is admirably comprehensive, its extensive details within a few short chapters may feel overwhelming to students. The author tackles an impressive breadth of concepts in Chapter 1, 2, 3, and 4, which leads to 50-plus-page chapters... read more

While the book is admirably comprehensive, its extensive details within a few short chapters may feel overwhelming to students. The author tackles an impressive breadth of concepts in Chapter 1, 2, 3, and 4, which leads to 50-plus-page chapters that are dense with statistical analyses and critical vocabulary. These topics are likely better broached in manageable snippets rather than hefty single chapters.

The ideas addressed in Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking are accurate but at times notably political. While politics are effectively used to exemplify key concepts, some students may be distracted by distinct political leanings.

The terms and definitions included are relevant, but the examples are specific to the current political, cultural, and social climates, which could make the materials seem dated in a few years without intentional and consistent updates.

While the reasoning is accurate, the author tends to complicate rather than simplify -- perhaps in an effort to cover a spectrum of related concepts. Beginning readers are likely to be overwhelmed and under-encouraged by his approach.

Consistency rating: 3

The four chapters are somewhat consistent in their play of definition, explanation, and example, but the structure of each chapter varies according to the concepts covered. In the third chapter, for example, key ideas are divided into sub-topics numbering from 3.1 to 3.10. In the fourth chapter, the sub-divisions are further divided into sub-sections numbered 4.1.1-4.1.5, 4.2.1-4.2.2, and 4.3.1 to 4.3.6. Readers who are working quickly to master new concepts may find themselves mired in similarly numbered subheadings, longing for a grounded concepts on which to hinge other key principles.

Modularity rating: 3

The book's four chapters make it mostly self-referential. The author would do well to beak this text down into additional subsections, easing readers' accessibility.

The content of the book flows logically and well, but the information needs to be better sub-divided within each larger chapter, easing the student experience.

The book's interface is effective, allowing readers to move from one section to the next with a single click. Additional sub-sections would ease this interplay even further.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

Some minor errors throughout.

For the most part, the book is culturally neutral, avoiding direct cultural references in an effort to remain relevant.

Reviewed by Yoichi Ishida, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Ohio University on 2/1/18

This textbook covers enough topics for a first-year course on logic and critical thinking. Chapter 1 covers the basics as in any standard textbook in this area. Chapter 2 covers propositional logic and categorical logic. In propositional logic,... read more

This textbook covers enough topics for a first-year course on logic and critical thinking. Chapter 1 covers the basics as in any standard textbook in this area. Chapter 2 covers propositional logic and categorical logic. In propositional logic, this textbook does not cover suppositional arguments, such as conditional proof and reductio ad absurdum. But other standard argument forms are covered. Chapter 3 covers inductive logic, and here this textbook introduces probability and its relationship with cognitive biases, which are rarely discussed in other textbooks. Chapter 4 introduces common informal fallacies. The answers to all the exercises are given at the end. However, the last set of exercises is in Chapter 3, Section 5. There are no exercises in the rest of the chapter. Chapter 4 has no exercises either. There is index, but no glossary.

The textbook is accurate.

The content of this textbook will not become obsolete soon.

The textbook is written clearly.

The textbook is internally consistent.

The textbook is fairly modular. For example, Chapter 3, together with a few sections from Chapter 1, can be used as a short introduction to inductive logic.

The textbook is well-organized.

There are no interface issues.

I did not find any grammatical errors.

This textbook is relevant to a first semester logic or critical thinking course.

Reviewed by Payal Doctor, Associate Professro, LaGuardia Community College on 2/1/18

This text is a beginner textbook for arguments and propositional logic. It covers the basics of identifying arguments, building arguments, and using basic logic to construct propositions and arguments. It is quite comprehensive for a beginner... read more

This text is a beginner textbook for arguments and propositional logic. It covers the basics of identifying arguments, building arguments, and using basic logic to construct propositions and arguments. It is quite comprehensive for a beginner book, but seems to be a good text for a course that needs a foundation for arguments. There are exercises on creating truth tables and proofs, so it could work as a logic primer in short sessions or with the addition of other course content.

The books is accurate in the information it presents. It does not contain errors and is unbiased. It covers the essential vocabulary clearly and givens ample examples and exercises to ensure the student understands the concepts

The content of the book is up to date and can be easily updated. Some examples are very current for analyzing the argument structure in a speech, but for this sort of text understandable examples are important and the author uses good examples.

The book is clear and easy to read. In particular, this is a good text for community college students who often have difficulty with reading comprehension. The language is straightforward and concepts are well explained.

The book is consistent in terminology, formatting, and examples. It flows well from one topic to the next, but it is also possible to jump around the text without loosing the voice of the text.

The books is broken down into sub units that make it easy to assign short blocks of content at a time. Later in the text, it does refer to a few concepts that appear early in that text, but these are all basic concepts that must be used to create a clear and understandable text. No sections are too long and each section stays on topic and relates the topic to those that have come before when necessary.

The flow of the text is logical and clear. It begins with the basic building blocks of arguments, and practice identifying more and more complex arguments is offered. Each chapter builds up from the previous chapter in introducing propositional logic, truth tables, and logical arguments. A select number of fallacies are presented at the end of the text, but these are related to topics that were presented before, so it makes sense to have these last.

The text is free if interface issues. I used the PDF and it worked fine on various devices without loosing formatting.

1. The book contains no grammatical errors.

The text is culturally sensitive, but examples used are a bit odd and may be objectionable to some students. For instance, President Obama's speech on Syria is used to evaluate an extended argument. This is an excellent example and it is explained well, but some who disagree with Obama's policies may have trouble moving beyond their own politics. However, other examples look at issues from all political viewpoints and ask students to evaluate the argument, fallacy, etc. and work towards looking past their own beliefs. Overall this book does use a variety of examples that most students can understand and evaluate.

My favorite part of this book is that it seems to be written for community college students. My students have trouble understanding readings in the New York Times, so it is nice to see a logic and critical thinking text use real language that students can understand and follow without the constant need of a dictionary.

Reviewed by Rebecca Owen, Adjunct Professor, Writing, Chemeketa Community College on 6/20/17

This textbook is quite thorough--there are conversational explanations of argument structure and logic. I think students will be happy with the conversational style this author employs. Also, there are many examples and exercises using current... read more

This textbook is quite thorough--there are conversational explanations of argument structure and logic. I think students will be happy with the conversational style this author employs. Also, there are many examples and exercises using current events, funny scenarios, or other interesting ways to evaluate argument structure and validity. The third section, which deals with logical fallacies, is very clear and comprehensive. My only critique of the material included in the book is that the middle section may be a bit dense and math-oriented for learners who appreciate the more informal, informative style of the first and third section. Also, the book ends rather abruptly--it moves from a description of a logical fallacy to the answers for the exercises earlier in the text.

The content is very reader-friendly, and the author writes with authority and clarity throughout the text. There are a few surface-level typos (Starbuck's instead of Starbucks, etc.). None of these small errors detract from the quality of the content, though.

One thing I really liked about this text was the author's wide variety of examples. To demonstrate different facets of logic, he used examples from current media, movies, literature, and many other concepts that students would recognize from their daily lives. The exercises in this text also included these types of pop-culture references, and I think students will enjoy the familiarity--as well as being able to see the logical structures behind these types of references. I don't think the text will need to be updated to reflect new instances and occurrences; the author did a fine job at picking examples that are relatively timeless. As far as the subject matter itself, I don't think it will become obsolete any time soon.

The author writes in a very conversational, easy-to-read manner. The examples used are quite helpful. The third section on logical fallacies is quite easy to read, follow, and understand. A student in an argument writing class could benefit from this section of the book. The middle section is less clear, though. A student learning about the basics of logic might have a hard time digesting all of the information contained in chapter two. This material might be better in two separate chapters. I think the author loses the balance of a conversational, helpful tone and focuses too heavily on equations.

Consistency rating: 4

Terminology in this book is quite consistent--the key words are highlighted in bold. Chapters 1 and 3 follow a similar organizational pattern, but chapter 2 is where the material becomes more dense and equation-heavy. I also would have liked a closing passage--something to indicate to the reader that we've reached the end of the chapter as well as the book.

I liked the overall structure of this book. If I'm teaching an argumentative writing class, I could easily point the students to the chapters where they can identify and practice identifying fallacies, for instance. The opening chapter is clear in defining the necessary terms, and it gives the students an understanding of the toolbox available to them in assessing and evaluating arguments. Even though I found the middle section to be dense, smaller portions could be assigned.

The author does a fine job connecting each defined term to the next. He provides examples of how each defined term works in a sentence or in an argument, and then he provides practice activities for students to try. The answers for each question are listed in the final pages of the book. The middle section feels like the heaviest part of the whole book--it would take the longest time for a student to digest if assigned the whole chapter. Even though this middle section is a bit heavy, it does fit the overall structure and flow of the book. New material builds on previous chapters and sub-chapters. It ends abruptly--I didn't realize that it had ended, and all of a sudden I found myself in the answer section for those earlier exercises.

The simple layout is quite helpful! There is nothing distracting, image-wise, in this text. The table of contents is clearly arranged, and each topic is easy to find.

Tiny edits could be made (Starbuck's/Starbucks, for one). Otherwise, it is free of distracting grammatical errors.

This text is quite culturally relevant. For instance, there is one example that mentions the rumors of Barack Obama's birthplace as somewhere other than the United States. This example is used to explain how to analyze an argument for validity. The more "sensational" examples (like the Obama one above) are helpful in showing argument structure, and they can also help students see how rumors like this might gain traction--as well as help to show students how to debunk them with their newfound understanding of argument and logic.

The writing style is excellent for the subject matter, especially in the third section explaining logical fallacies. Thank you for the opportunity to read and review this text!

Reviewed by Laurel Panser, Instructor, Riverland Community College on 6/20/17

This is a review of Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking, an open source book version 1.4 by Matthew Van Cleave. The comparison book used was Patrick J. Hurley’s A Concise Introduction to Logic 12th Edition published by Cengage as well as... read more

This is a review of Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking, an open source book version 1.4 by Matthew Van Cleave. The comparison book used was Patrick J. Hurley’s A Concise Introduction to Logic 12th Edition published by Cengage as well as the 13th edition with the same title. Lori Watson is the second author on the 13th edition.

Competing with Hurley is difficult with respect to comprehensiveness. For example, Van Cleave’s book is comprehensive to the extent that it probably covers at least two-thirds or more of what is dealt with in most introductory, one-semester logic courses. Van Cleave’s chapter 1 provides an overview of argumentation including discerning non-arguments from arguments, premises versus conclusions, deductive from inductive arguments, validity, soundness and more. Much of Van Cleave’s chapter 1 parallel’s Hurley’s chapter 1. Hurley’s chapter 3 regarding informal fallacies is comprehensive while Van Cleave’s chapter 4 on this topic is less extensive. Categorical propositions are a topic in Van Cleave’s chapter 2; Hurley’s chapters 4 and 5 provide more instruction on this, however. Propositional logic is another topic in Van Cleave’s chapter 2; Hurley’s chapters 6 and 7 provide more information on this, though. Van Cleave did discuss messy issues of language meaning briefly in his chapter 1; that is the topic of Hurley’s chapter 2.

Van Cleave’s book includes exercises with answers and an index. A glossary was not included.

Reviews of open source textbooks typically include criteria besides comprehensiveness. These include comments on accuracy of the information, whether the book will become obsolete soon, jargon-free clarity to the extent that is possible, organization, navigation ease, freedom from grammar errors and cultural relevance; Van Cleave’s book is fine in all of these areas. Further criteria for open source books includes modularity and consistency of terminology. Modularity is defined as including blocks of learning material that are easy to assign to students. Hurley’s book has a greater degree of modularity than Van Cleave’s textbook. The prose Van Cleave used is consistent.

Van Cleave’s book will not become obsolete soon.

Van Cleave’s book has accessible prose.

Van Cleave used terminology consistently.

Van Cleave’s book has a reasonable degree of modularity.

Van Cleave’s book is organized. The structure and flow of his book is fine.

Problems with navigation are not present.

Grammar problems were not present.

Van Cleave’s book is culturally relevant.

Van Cleave’s book is appropriate for some first semester logic courses.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Reconstructing and analyzing arguments

- 1.1 What is an argument?

- 1.2 Identifying arguments

- 1.3 Arguments vs. explanations

- 1.4 More complex argument structures

- 1.5 Using your own paraphrases of premises and conclusions to reconstruct arguments in standard form

- 1.6 Validity

- 1.7 Soundness

- 1.8 Deductive vs. inductive arguments

- 1.9 Arguments with missing premises

- 1.10 Assuring, guarding, and discounting

- 1.11 Evaluative language

- 1.12 Evaluating a real-life argument

Chapter 2: Formal methods of evaluating arguments

- 2.1 What is a formal method of evaluation and why do we need them?

- 2.2 Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives

- 2.3 Negation and disjunction

- 2.4 Using parentheses to translate complex sentences

- 2.5 “Not both” and “neither nor”

- 2.6 The truth table test of validity

- 2.7 Conditionals

- 2.8 “Unless”

- 2.9 Material equivalence

- 2.10 Tautologies, contradictions, and contingent statements

- 2.11 Proofs and the 8 valid forms of inference

- 2.12 How to construct proofs

- 2.13 Short review of propositional logic

- 2.14 Categorical logic

- 2.15 The Venn test of validity for immediate categorical inferences

- 2.16 Universal statements and existential commitment

- 2.17 Venn validity for categorical syllogisms

Chapter 3: Evaluating inductive arguments and probabilistic and statistical fallacies

- 3.1 Inductive arguments and statistical generalizations

- 3.2 Inference to the best explanation and the seven explanatory virtues

- 3.3 Analogical arguments

- 3.4 Causal arguments

- 3.5 Probability

- 3.6 The conjunction fallacy

- 3.7 The base rate fallacy

- 3.8 The small numbers fallacy

- 3.9 Regression to the mean fallacy

- 3.10 Gambler's fallacy

Chapter 4: Informal fallacies

- 4.1 Formal vs. informal fallacies

- 4.1.1 Composition fallacy

- 4.1.2 Division fallacy

- 4.1.3 Begging the question fallacy

- 4.1.4 False dichotomy

- 4.1.5 Equivocation

- 4.2 Slippery slope fallacies

- 4.2.1 Conceptual slippery slope

- 4.2.2 Causal slippery slope

- 4.3 Fallacies of relevance

- 4.3.1 Ad hominem

- 4.3.2 Straw man

- 4.3.3 Tu quoque

- 4.3.4 Genetic

- 4.3.5 Appeal to consequences

- 4.3.6 Appeal to authority

Answers to exercises Glossary/Index

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This is an introductory textbook in logic and critical thinking. The goal of the textbook is to provide the reader with a set of tools and skills that will enable them to identify and evaluate arguments. The book is intended for an introductory course that covers both formal and informal logic. As such, it is not a formal logic textbook, but is closer to what one would find marketed as a “critical thinking textbook.”

About the Contributors

Matthew Van Cleave , PhD, Philosophy, University of Cincinnati, 2007. VAP at Concordia College (Moorhead), 2008-2012. Assistant Professor at Lansing Community College, 2012-2016. Professor at Lansing Community College, 2016-

Contribute to this Page

PHIL102: Introduction to Critical Thinking and Logic

Course introduction.

- Time: 40 hours

- College Credit Recommended ($25 Proctor Fee) -->

- Free Certificate

The course touches upon a wide range of reasoning skills, from verbal argument analysis to formal logic, visual and statistical reasoning, scientific methodology, and creative thinking. Mastering these skills will help you become a more perceptive reader and listener, a more persuasive writer and presenter, and a more effective researcher and scientist.

The first unit introduces the terrain of critical thinking and covers the basics of meaning analysis, while the second unit provides a primer for analyzing arguments. All of the material in these first units will be built upon in subsequent units, which cover informal and formal logic, Venn diagrams, scientific reasoning, and strategic and creative thinking.

Course Syllabus

First, read the course syllabus. Then, enroll in the course by clicking "Enroll me". Click Unit 1 to read its introduction and learning outcomes. You will then see the learning materials and instructions on how to use them.

Unit 1: Introduction and Meaning Analysis

Critical thinking is a broad classification for a diverse array of reasoning techniques. In general, critical thinking works by breaking arguments and claims down to their basic underlying structure so we can see them clearly and determine whether they are rational. The idea is to help us do a better job of understanding and evaluating what we read, what we hear, and what we write and say.

In this unit, we will define the broad contours of critical thinking and learn why it is a valuable and useful object of study. We will also introduce the fundamentals of meaning analysis: the difference between literal meaning and implication, the principles of definition, how to identify when a disagreement is merely verbal, the distinction between necessary and sufficient conditions, and problems with the imprecision of ordinary language.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 5 hours.

Unit 2: Argument Analysis

Arguments are the fundamental components of all rational discourse: nearly everything we read and write, like scientific reports, newspaper columns, and personal letters, as well as most of our verbal conversations, contain arguments. Picking the arguments out from the rest of our often convoluted discourse can be difficult. Once we have identified an argument, we still need to determine whether or not it is sound. Luckily, arguments obey a set of formal rules that we can use to determine whether they are good or bad.

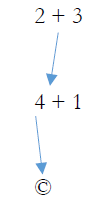

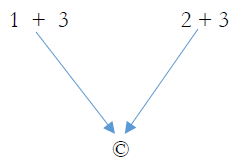

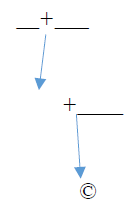

In this unit, you will learn how to identify arguments, what makes an argument sound as opposed to unsound or merely valid, the difference between deductive and inductive reasoning, and how to map arguments to reveal their structure.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 7 hours.

Unit 3: Basic Sentential Logic

This unit introduces a topic that many students find intimidating: formal logic. Although it sounds difficult and complicated, formal (or symbolic) logic is actually a fairly straightforward way of revealing the structure of reasoning. By translating arguments into symbols, you can more readily see what is right and wrong with them and learn how to formulate better arguments. Advanced courses in formal logic focus on using rules of inference to construct elaborate proofs. Using these techniques, you can solve many complicated problems simply by manipulating symbols on the page. In this course, however, you will only be looking at the most basic properties of a system of logic. In this unit, you will learn how to turn phrases in ordinary language into well-formed formulas, draw truth tables for formulas, and evaluate arguments using those truth tables.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 13 hours.

Unit 4: Venn Diagrams

In addition to using predicate logic, the limitations of sentential logic can also be overcome by using Venn diagrams to illustrate statements and arguments. Statements that include general words like "some" or "few" as well as absolute words like "every" and "all" – so-called categorical statements – lend themselves to being represented on paper as circles that may or may not overlap.

Venn diagrams are especially helpful when dealing with logical arguments called syllogisms. Syllogisms are a special type of three-step argument with two premises and a conclusion, which involve quantifying terms. In this unit, you will learn the basic principles of Venn diagrams, how to use them to represent statements, and how to use them to evaluate arguments.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 6 hours.

Unit 5: Fallacies

Now that you have studied the necessary structure of a good argument and can represent its structure visually, you might think it would be simple to pick out bad arguments. However, identifying bad arguments can be very tricky in practice. Very often, what at first appears to be ironclad reasoning turns out to contain one or more subtle errors.

Fortunately, there are many easily identifiable fallacies (mistakes of reasoning) that you can learn to recognize by their structure or content. In this unit, you will learn about the nature of fallacies, look at a couple of different ways of classifying them, and spend some time dealing with the most common fallacies in detail.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 3 hours.

Unit 6: Scientific Reasoning

Unlike the syllogistic arguments you explored in the last unit, which are a form of deductive argument, scientific reasoning is empirical. This means that it depends on observation and evidence, not logical principles. Although some principles of deductive reasoning do apply in science, such as the principle of contradiction, scientific arguments are often inductive. For this reason, science often deals with confirmation and disconfirmation.

Nonetheless, there are general guidelines about what constitutes good scientific reasoning, and scientists are trained to be critical of their inferences and those of others in the scientific community. In this unit, you will investigate some standard methods of scientific reasoning, some principles of confirmation and disconfirmation, and some techniques for identifying and reasoning about causation.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 4 hours.

Unit 7: Strategic Reasoning and Creativity

While most of this course has focused on the types of reasoning necessary to critique and evaluate existing knowledge or to extend our knowledge following correct procedures and rules, an enormous branch of our reasoning practice runs in the opposite direction. Strategic reasoning, problem-solving, and creative thinking all rely on an ineffable component of novelty supplied by the thinker.

Despite their seemingly mystical nature, problem-solving and creative thinking are best approached by following tried and tested procedures that prompt our cognitive faculties to produce new ideas and solutions by extending our existing knowledge. In this unit, you will investigate problem-solving techniques, representing complex problems visually, making decisions in risky and uncertain scenarios, and creative thinking in general.

Completing this unit should take you approximately 2 hours.

Study Guide

This study guide will help you get ready for the final exam. It discusses the key topics in each unit, walks through the learning outcomes, and lists important vocabulary terms. It is not meant to replace the course materials!

Course Feedback Survey

Please take a few minutes to give us feedback about this course. We appreciate your feedback, whether you completed the whole course or even just a few resources. Your feedback will help us make our courses better, and we use your feedback each time we make updates to our courses.

If you come across any urgent problems, email [email protected].

Certificate Final Exam

Take this exam if you want to earn a free Course Completion Certificate.

To receive a free Course Completion Certificate, you will need to earn a grade of 70% or higher on this final exam. Your grade for the exam will be calculated as soon as you complete it. If you do not pass the exam on your first try, you can take it again as many times as you want, with a 7-day waiting period between each attempt.

Once you pass this final exam, you will be awarded a free Course Completion Certificate .

Saylor Direct Credit

Take this exam if you want to earn college credit for this course . This course is eligible for college credit through Saylor Academy's Saylor Direct Credit Program .

The Saylor Direct Credit Final Exam requires a proctoring fee of $5 . To pass this course and earn a Credly Badge and official transcript , you will need to earn a grade of 70% or higher on the Saylor Direct Credit Final Exam. Your grade for this exam will be calculated as soon as you complete it. If you do not pass the exam on your first try, you can take it again a maximum of 3 times , with a 14-day waiting period between each attempt.

We are partnering with SmarterProctoring to help make the proctoring fee more affordable. We will be recording you, your screen, and the audio in your room during the exam. This is an automated proctoring service, but no decisions are automated; recordings are only viewed by our staff with the purpose of making sure it is you taking the exam and verifying any questions about exam integrity. We understand that there are challenges with learning at home - we won't invalidate your exam just because your child ran into the room!

Requirements:

- Desktop Computer

- Chrome (v74+)

- Webcam + Microphone

- 1mbps+ Internet Connection

Once you pass this final exam, you will be awarded a Credly Badge and can request an official transcript .

Saylor Direct Credit Exam

This exam is part of the Saylor Direct College Credit program. Before attempting this exam, review the Saylor Direct Credit page for complete requirements.

Essential exam information:

- You must take this exam with our automated proctor. If you cannot, please contact us to request an override.

- The automated proctoring session will cost $5 .

- This is a closed-book, closed-notes exam (see allowed resources below).

- You will have two (2) hours to complete this exam.

- You have up to 3 attempts, but you must wait 14 days between consecutive attempts of this exam.

- The passing grade is 70% or higher.

- This exam consists of 50 multiple-choice questions.

Some details about taking your exam:

- Exam questions are distributed across multiple pages.

- Exam questions will have several plausible options; be sure to pick the answer that best satisfies each part of the question.

- Your answers are saved each time you move to another page within the exam.

- You can answer the questions in any order.

- You can go directly to any question by clicking its number in the navigation panel.

- You can flag a question to remind yourself to return to it later.

- You will receive your grade as soon as you submit your answers.

Allowed resources:

Gather these resources before you start your exam.

- Blank paper

What should I do before my exam?

- Gather these before you start your exam:

- A photo I.D. to show before your exam.

- A credit card to pay the automated proctoring fee.

- (optional) Blank paper and pencil.

- (optional) A glass of water.

- Make sure your work area is well-lit and your face is visible.

- We will be recording your screen, so close any extra tabs!

- Disconnect any extra monitors attached to your computer.

- You will have up to two (2) hours to complete your exam. Try to make sure you won't be interrupted during that time!

- You will require at least 1mbps of internet bandwidth. Ask others sharing your connection not to stream during your exam.

- Take a deep breath; you got this!

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1: Basic Concepts

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 223680

The most important thing we do as human beings is learn how to think. This is important in two senses of the word: it’s important to human beings because it is the most distinctively unique fact about our species—we think rationally and abstractly—but it’s also important because it the most wide reaching capacity we have—it touches virtually all aspects of our lives. Having a heart that pumps blood or a body capable of certain physical activities might be more fundamental meaning more crucial to simply surviving, but thinking underlies a broad range of activities without which we would be living less than full human lives.

The common title of this course is “Logic and Critical Thinking.” So, we can think about the course as having two main components: the study of formal logic and the study of the tools and strategies of critical thinking. This text is structured in a bit of a “sandwich”. Units on critical thinking and then formal logic, and then units on more critical thinking topics.

First, Logic. We’ll define logic more fully later, but for now: logic is a sort of reasoning that is mathematical in its precision and proofs. It’s like math with words and concepts, in a sense.

Oh no! Not math! I'm no good at math.

Don’t worry, dear student. Logic is more straightforward than a lot of the complex concepts that get discussed in math classes. Even better, all of logic can be broken down into simple, step-by-step processes that a computer can do. You just need to follow the steps carefully and you’ll be guaranteed the right answer every time. There’s no magic to it, no special skills or abilities needed. You just need to follow directions carefully and put a bit of work into it.

Next, let’s get a bit of a definition of critical thinking going. Critical thinking is primarily the ability to think carefully about thinking and reasoning—to have the ability to criticize your own reasoning. ‘Criticize’ here isn’t meant in the sense of being mean or talking down or making fun of. Instead, I mean the word in the sense of, for example, how a coach might take a critical stance toward her players’ skills—he throws high every time, she doesn’t lead with her foot, they ride too forward in the saddle, etc. ‘Critical’ here means something more like ‘reflective’ or ‘careful’ or ‘attention to potential errors’.

So to engage in critical thinking is to engage in self-critical, self-reflective, self-aware thinking and reasoning—thinking and reasoning aimed at self-improvement, at truth, and at careful, deliberate, proper patterns of reasoning.

There are many definitions of what critical thinking is, but here’re my thoughts:

As you can see, being a critical thinker involves training yourself to have a lot of good habits and dispositions. It involves developing rational virtues so that when the time comes to think about something complex, you are naturally disposed to think well. It doesn’t happen overnight and it certainly doesn’t come for free—no one is born with it. We all need to train ourselves and educate ourselves to stay guarded against errors in reasoning.

- 1.1: Vital Course Concepts

- 1.2: Kinds of Inferences

- 1.3: Chapter 1 - Key Terms

- 1.E: Chapter One (Exercises)

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Special Issues

- Virtual Issues

- Trending Articles

- IMPACT Content

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Author Resources

- Read & Publish

- Why Publish with JOPE?

- About the Journal of Philosophy of Education

- About The Philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, the central argument, where should non-western contributions to logic and critical thinking be taught, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Does Critical Thinking and Logic Education Have a Western Bias? The Case of the Nyāya School of Classical Indian Philosophy

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Anand Jayprakash Vaidya, Does Critical Thinking and Logic Education Have a Western Bias? The Case of the Nyāya School of Classical Indian Philosophy, Journal of Philosophy of Education , Volume 51, Issue 1, February 2017, Pages 132–160, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12189

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In this paper I develop a cross-cultural critique of contemporary critical thinking education in the United States, the United Kingdom, and those educational systems that adopt critical thinking education from the standard model used in the US and UK. The cross-cultural critique rests on the idea that contemporary critical thinking textbooks completely ignore contributions from non-western sources, such as those found in the African, Arabic, Buddhist, Jain, Mohist and Nyāya philosophical traditions. The exclusion of these traditions leads to the conclusion that critical thinking educators, by using standard textbooks are implicitly sending the message to their students that there are no important contributions to the study of logic and argumentation that derive from non-western sources. As a case study I offer a sustained analysis of the so-called Hindu Syllogism that derives from the Nyāya School of classical Indian philosophy. I close with a discussion of why contributions from non-western sources, such as the Hindu Syllogism, belong in a Critical Thinking course as opposed to an area studies course, such as Asian Philosophy .

One question in the philosophy of education is the question concerning education for democracy , EDQ: How should public education enable the ethical implementation and proper functioning of democratic processes, such as voting on the basis of public and civic discourse? At least one plausible answer is that a public education should provide citizens of a political body with basic skills in public discourse, which is inclusive of critical thinking and civic debate. That is, education for democracy should have an element that enables ethical public discourse on topics of shared concern. This answer is grounded on two ideas. First, democratic processes, such as voting, take into account the will of the people through reflective deliberation and the exchange of ideas on matters of public concern, such as prison reform, marriage, taxation and gun control. Second, critical thinking through civic engagement allows for the expression of individual autonomy on a matter of public concern. Call this general answer to EDQ, the critical thinking and civic debate response , CTCD. Two important questions the CTCD response faces are the content question : What exactly are critical thinking, civic debate and ethical public discourse? And the normative question : What are the appropriate forms, norms and intellectual virtues by which we should engage in critical thinking, civic debate and ethical public discourse? 1

On March 24, 2014 at the Cross Examination Debate Association (CEDA) Championships at Indiana University, two Towson University students, Ameena Ruffin and Korey Johnson, became the first African-American women to win a national college debate tournament, for which the resolution asked whether the US president's war powers should be restricted. Rather than address the resolution straight on, Ruffin and Johnson, along with other teams of African-Americans, attacked its premise. The more pressing issue, they argued, is how the US government is at war with poor black communities. In the final round, Ruffin and Johnson squared off against Rashid Campbell and George Lee from the University of Oklahoma, two highly accomplished African-American debaters with distinctive dreadlocks and dashikis. Over four hours, the two teams engaged in a heated discussion of concepts like “nigga authenticity” and performed hip-hop and spoken-word poetry in the traditional timed format. At one point during Lee's rebuttal, the clock ran out but he refused to yield the floor. “Fuck the time!” he yelled. His partner Campbell, who won the top speaker award at the National Debate Tournament two weeks later, had been unfairly targeted by the police at the debate venue just days before, and cited this experience as evidence for his case against the government's treatment of poor African-Americans.

In the 2013 championship, two men from Emporia State University, Ryan Walsh and Elijah Smith, employed a similar style and became the first African-Americans to win two national debate tournaments. Many of their arguments, based on personal memoir and rap music, completely ignored the stated resolution, and instead asserted that the framework of collegiate debate has historically privileged straight, white, middle-class students . ( emphasis added ) 3

Although there are many important features that these cases bring to light, here I want to draw attention to three features that help us understand the importance of both the content question and the normative question. First, the kind of evidence that is appealed to does not just consist in objective facts, such as what the law states, and reasoning deductively or inductively from a set of premises, it also contains personal experience. Second, the mode of engagement used does not consist simply in rational argumentation through the use of the standard format of ethical theory, followed by premise, application and finally a conclusion. Rather, it includes poetry and hip-hop that takes both a reason-based approach and an emotional and musical element into play. Third, the norm of engagement used does not see deference to rules as trumping either the importance of what is talked about or the length of time one talks about it. We might summarise a caricature reaction to these students by a hypothetical critic as follows: how rude of these students to not debate the issue, to disregard the rules, and to fail to take into consideration the kinds of evidence required for public debate and discourse on matters of social and political concern. In light of these cases and the caricature, the critical thinking and civic debate community faces an important and unexamined question : does critical thinking and civic debate education rest on an uncritical examination of its very foundation? Is the foundation perhaps insensitive to race, class, gender and non-western traditions of critical thinking and debate? Call this question the meta-critical question about critical thinking.

The meta-critical question about critical thinking and civic debate education is extremely important to any education policy that embraces the CTCD response to EDQ. Furthermore, it is central to the project of coming to understand how public discourse is possible in a community that has diverse individuals with non-overlapping conceptions of the good life. In the next section, I present, explain, and defend the central argument leading to the conclusion that critical thinking education should include contributions from non-western sources. As a case study I present some material, well known in the classical Indian philosophical and comparative philosophy community, concerning contributions to logic and critical thinking deriving from the Nyāya tradition of orthodox Indian philosophy. My examination of these contributions aims to establish that there are things that critical thinking education can take on board from non-western traditions that are important and valuable to critical thinking and logic education. In the third section , I present and respond to the objection that contributions to critical thinking from non-western traditions should not be taught in a Critical Thinking course but rather in an area studies course, such as Asian Philosophy .

At present there is a social blindspot that critical thinking and debate education suffers from in the US, UK and those countries that use the standard model that originates from the US and UK. In short the blindspot is that critical thinking and debate education is insensitive to variation over what could count as critical thinking and civic debate based on an examination of non-western contributions to critical thinking and debate. The neglect of these traditions is largely due to the fact that those that work on critical thinking, logic and debate, such as members of the informal logic community are generally not historically informed about non-western contributions to critical thinking through engagement with those that work on Asian and comparative philosophy. Simply put, institutional separation has led to an impoverished educational package for critical thinking education for the past 100 years in which the modern university has developed. The central argument I will develop to expose the problem is as follows.

Critical thinking, and practice in ethical civic debate, is important to public discourse on social and political issues that citizens of a democratic body vote on when making policy decisions that concern all members of the public. The current model for critical thinking and civic debate education is dominated by a western account of informal logic, formal logic, debate rules and intellectual virtues. Critical thinking education should include contributions from non-western philosophers.∴ Critical thinking education should be revised so as to be inclusive of contributions from non-western thinkers.

Why should we accept the premises of this argument?

Premise 1: Critical thinking, and practice in ethical civic debate, is important to public discourse on social and political issues that citizens of a democratic body vote on when making policy decisions that concern all members of the public.

The main objection to Premise 1 derives from the work of Michael Huemer's (2005) paper: Is Critical Thinking Epistemically Responsible? In this work he provides an argument against the epistemic responsibility of critical thinking. The core idea is that if one is forming a belief on an issue of public concern one ought to do so responsibly. Given that one ought to form the belief in a responsible way, one might consider different strategies open to the person for how to form the belief. Consider the following belief forming strategies.

Credulity : In forming a belief a person is to canvass the opinions of a number of experts and adopt the belief held by most of them. In the best case, the person finds a poll of the experts; failing that, the person may look through several reputable sources, such as scholarly books and peer-reviewed journal articles, and identify the conclusions of the experts.

Skepticism : In forming a belief a person is to form no opinion on the matter; that is, the person is to withhold judgement about the issue.

Critical Thinking : In forming a belief a person is to gather arguments and evidence that are available on the issue, from all sides, and assess them. The person tries thereby to form some overall impression on the issue. If the person forms such an impression, then she bases her belief on it. Otherwise, the person suspends judgement.

Now, where P is a specific controversial and publicly debated issue, and C b P is the context of belief formation for P, the central argument against the epistemic responsibility of critical thinking is the following.

Adopting Critical Thinking about P in C b P is epistemically responsible only if Critically Thinking about P is the most reliable strategy from the available strategies in C b P. One ought to always use the most reliable strategy available in forming a belief about an issue of public concern. Critical Thinking about P is not the most reliable strategy from the available strategies in C b P.∴ It is not the case that Critical Thinking about P in C b P is epistemically responsible.

In Vaidya (2013) , I offered an extensive argument against Huemer's position. That argument depends on a development of a theory of what constitutes an autonomous critical identity, and why forming a critical identity is valuable for a person. As a consequence, I will not go into a sustained response to Huemer's argument here. Rather, I will note a simple set of points that can be used to assuage the initial force of what is being argued.

First, in so far as the claim is that critical thinking about an issue is not to be preferred over taking the view of an expert on an issue it is clear that choosing who the expert is on the issue is a matter of critical thinking. In order for one to identify someone as an expert one must understand how to track through sources for the appropriate identification of experts. So, in general, deference to experts actually depends on critical thinking , since deference is a choice one must make. The core idea is that one cannot outsource all cognition to an alternative source, since outsourcing is itself a decision that has to be made .

Secondly, it is important to distinguish between the different types of issues in which deference to experts can be made. For example, there is a difference between an argument that contains a scientific conclusion, with mathematical and scientific premises, and an argument that contains moral premises and has a moral conclusion. Given this difference, it is plausible to maintain that deference to experts in the scientific and mathematics case is not the same as deference in the moral case. While I can defer to a moral expert to tell me what a moral theory says, such as what the details of consequentialism, as opposed to deontology, are, I can't defer to a moral expert on the issue of what the correct moral conclusion is, independently of the adoption of a specific moral view. By contrast, I can defer to a scientist or a mathematician as to which conclusion to believe on the basis of the premises.

Premise 2: The current model for critical thinking and civic debate education is dominated by a western account of informal logic, formal logic, debate rules and intellectual virtues.

The key defence I will offer for Premise 2 relies on an examination of two of the most commonly used textbooks for critical thinking in the US and UK, Patrick Hurley's A Concise Introduction to Logic and Lewis Vaughn's The Power of Critical Thinking: Effective Reasoning about Ordinary and Extraordinary Claims . The guiding idea of the argument is that if our main textbooks for teaching critical thinking and logic at the introductory level do not engage non-western philosophy, we can reasonably infer that those that use the textbook are not teaching critical thinking and logic by way of engaging non-western sources. Of course there will be those that supplement the texts, perhaps even for the very reason I am presenting here—that they lack non-western ideas. But we can safely examine and entertain the claim that I am defending as being primarily about textbooks as opposed to variable classroom practice . More importantly, if the textbooks are widely used, which they are, we can ask: what do they represent about critical thinking and civic debate education?

I will focus my examination of non-western contributions to critical thinking on two places in critical thinking education where adjustments can be made. The point of this presentation is to show that our main textbooks can be altered to include non-western sources in specific ways. Although there are many contributions I could discuss, for simplicity I will focus on contributions from the Nyāya School of classical Indian philosophy concerning the nature of argumentation. In future work I will discuss other cases, such as those deriving from Africana, Arabic, Jaina, and Jewish philosophy. I begin my investigation of the Nyāya by answering a basic question: Is there a distinction in Indian philosophy between different kinds of discussions that allows us to isolate out critical discourse from non-critical discourse?

Is there any critical thinking in Indian philosophy?

Of course this question cannot be seriously entertained by anyone who works in Indology or Asian and Comparative Philosophy. However, for those who are not in the know, a presentation and defence of an affirmative answer must be made. For if one is to include non-western ideas about critical thinking in a textbook that is eventually used to teach the subject, one needs to show that non-western traditions are in fact engaging in critical thinking. In order to do that we need to look at competing views of what critical thinking is, the content question , in order to locate critical thinking outside of the west.

The Skill View holds that critical thinking is exhausted by the acquisition and proper deployment of critical thinking skills.

The Character View holds that critical thinking involves the acquisition and proper deployment of specific skills as well as the acquisition of specific character traits, dispositions, attitudes, and habits of mind. These components are aspects of the “critical spirit” ( Siegel, 1993 , 163–165).

Given this distinction, where does classical Indian philosophy fall? We have three options. Indian philosophical traditions take one or another of the views, or there is no discussion at all of either of these views. I will show that some Indian philosophical traditions make a distinction between various kinds of discussion, one of which is a critical discussion, and that there is evidence for the character view of critical thinking.

Discussion is the adoption of one of two opposing sides. What is adopted is analyzed in the form of the five members, and defended by the aid of any of the means of right knowledge, while its opposite is assailed by confutation, without deviation from the established tenets ( Sinha, 1990 , p. 19).

Wrangling , which aims at gaining victory, is the defense or attack of a proposition in the manner aforesaid, by quibbles, futilities, and other processes which deserve rebuke ( Sinha, 1990 , p. 20).

Cavil is a kind of wrangling, which consists in mere attacks on the opposite side ( Sinha, 1990 , p. 20).

Matilal maintains, on the basis of Akṣapāda's Nyāya Sūtras that there are three distinct kinds of discussions. Vāda is an honest debate where both sides, proponent and opponent, are seeking the truth, that is, wanting to establish the right view. Jalpa , by contrast, is a discussion/debate in which one tries to win by any means, fair or unfair. Vitaṇdā is a discussion in which one aims to destroy or demolish the opponent no matter how. One way to explain the distinctions is as follows: (i) vāda is an honest debate for the purposes of finding the truth, (ii) jalpa is a debate aimed at victory where one propounds a thesis; (ii) vitaṇdā is a debate aimed at victory, where no thesis is defended, one simply aims to demolish the view propounded by the proponent. 4 The distinction between these three kinds of discussions grounds the claim that classical Indian philosophers were aware of different kinds of discussions based on the purpose of the discussion, and that critical thinking, for the purposes of finding the truth on an issue, was not at all a foreign idea .

One who has acquired the knowledge (given by the authoritative text) based on various reasons and refuting the opponent's view in debates, does not get fastened by the pressure of the opponent's arguments nor does he get subdued by their arguments ( Van Loon, 2002 , p. 115).

Discussion with specialists: promotes pursuit and advancement of knowledge, provides dexterity, improves power of speaking, illumines fame, removes doubt in scriptures, if any, by repeating the topics, and it creates confidence in case there is any doubt, and brings forth new ideas. The ideas memorized in study from the teacher, will become firm when applied in (competitive) discussion ( Van Loon, 2002 , pp. 115–116).

Discussion with specialists is of two types— friendly discussion and hostile discussion. The friendly discussion is held with one who is endowed with learning, understanding and the power of expression and contradiction, devoid of irritability, having uncensored knowledge, without jealousy, able to be convinced and convince others, enduring and adept in the art of sweet conversation. While in discussion with such a person one should speak confidently, put questions unhesitatingly, reply to the sincere questioner with elaborateness, not be agitated with fear of defect, not be exhilarated on defeating the partner, nor boast before others, not hold fast to his solitary view due to attachment, not explain what is unknown to him, and convince the other party with politeness and be cautious in that. This is the method of friendly discussion ( Van Loon, 2002 , pp. 117–118, emphasis added ).

The passages from the Handbook of Ayurveda , especially the emphasised area, substantiate the idea that the character view is in play in one of the oldest recorded presentations of critical reasoning and how it is to be executed.

Furthermore, in his Indian Logic , Jonardon Ganeri (2004) presents a picture of argumentation and critical thinking in ancient India by turning to the classic dialogue of the Buddhist tradition: Milinda-pañha ( Questions for King Milinda ). Ganeri presents an important passage on discussion and critical thinking. 5

Milinda: Reverend Sir, will you discuss with me again?

Nāgasena: If your Majesty will discuss ( vāda ) as a scholar, well, but if you will discuss as a king, no.

Milinda: How is it that scholars discuss?

Nāgasena: When scholars talk a matter over one with another, then there is a winding up, an unraveling, one or other is convicted of error, and he then acknowledges his mistake; distinctions are drawn, and contra-distinctions; and yet thereby they are not angered. Thus do scholars, O King, discuss.

Milinda: And how do kings discuss?

Nāgasena: When a king, your Majesty, discusses a matter, and he advances a point, if any one differ from him on that point, he is apt to fine him, saying “Inflict such and such a punishment upon that fellow!” Thus, your Majesty, do kings discuss.

Milinda: Very well. It is as a scholar, not as a king, that I will discuss.( As quoted in Ganeri, 2004 , p. 17)

When scholars talk a matter over one with another, then is there a winding up, an unraveling, one or other is convicted of error, and he then acknowledges his mistake ; distinctions are drawn, and contra-distinctions; and yet thereby they are not angered ( as quoted in Ganeri, 2004 , p. 17, emphasis added ).

One reading of this claim is that Nāgasena is pointing out that a good discussion requires not only that certain moves are made ‘a winding up’ and an ‘unraveling’, but that the persons involved in making those moves have a certain epistemic temper . Participants in a good debate moreover have the capacity, and exercise the capacity, to (i) acknowledge mistakes , and (ii) not become angered by the consequences of where the inquiry leads . Nāgasena's answer to King Milinda suggests that Buddhist accounts of critical thinking also adopt the character view as opposed to the skill view . It is not enough to simply know how to ‘make moves’, ‘destroy’ or ‘demolish’ an opponent by various techniques. What is central to an honest debate is that a participant must also have a certain attitude and character that exemplifies a specific epistemic temper .

If one agrees with the character view, then this simple passage from Milinda - pañha could be compared with other passages, such as from the Meno , to teach critical thinking students what critical thinking is about. 6

The tale of two syllogisms

But once we have introduced students to what critical thinking is we are often faced with having to show them how to present their ideas for the purposes of a critical discussion. This takes us to the normative question : what are the appropriate forms, norms and intellectual virtues by which we should engage in critical thinking and civic debate? Many contemporary introductory level textbooks, such as Hurley's Concise Introduction to Logic and Vaughn's The Power of Critical Thinking contain some section where they present and discuss how an argument should be put into, what is often called, standard form . The notion of a standard form is normative . It suggests that an argument has a way that it should be presented for the purposes of engaging someone in a dialectical inquiry. Often discussion of standard form takes place either in the context of the presentation of how to identify an argument, or in the area where Aristotelian Categorical Logic is presented. However, the presentation of what constitutes a good argument, in either Hurley or Vaughn, is not given comparatively by considering other traditions. For example, it is simply presupposed that there is no alternative way in which one could present an argument. In contrast to the Aristotelian picture, the Hindu Syllogism has a different structure. It was developed and debated in classical Hindu, Buddhist and Jain philosophy for centuries. What is the basic contrast between the Aristotelian Syllogism and the Hindu Syllogism?

Aristotle was the ancient Greek philosopher who first codified logic for the western tradition. Students of logic and critical thinking are often brought into the topic of the syllogism and the standard form of reasoning by the following example from Aristotle.

Major Premise: All men are mortal.

Minor Premise: Socrates is a man.

Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

Akṣapāda Gautama was the founding father of the Nyāya School of philosophy. Like Aristotle he was also concerned with the proper form of how an argument should be displayed. The most commonly discussed argument in Indian philosophy deriving from his work, and perhaps even earlier, is the following:

Thesis: The hill has fire.

Reason/Mark: Because of smoke.

Rule/Examples: Wherever there is smoke, there is fire, as in a kitchen.

Application: This is such a case, i.e., the hill has smoke pervaded by fire.

Conclusion: Therefore it is so, i.e., the hill has fire. 7

There are many differences between the two examples. Two of the most important, highlighted by Matilal (1985 , pp. 6–7), are: (i) Aristotle's Syllogism is in subject-predicate form, Akṣapāda's Syllogism is in property-location form; (ii) Aristotle's study of syllogistic inference is primarily about universal and particular form propositions, Akṣapāda's study involves singular propositions in the thesis and conclusion. However, even though there are these differences, both examples have a similar normative force . They are both offered as a case of good reasoning , and they both are examples of what counts as how one should present their argument in a debate.

Given that neither Hurley nor Vaughn discuss the Hindu Syllogism, we might ask all of the following questions. Does it make sense as an argument form? Is there any benefit to teaching it? What do we gain by including it?

The western gaze on classical Indian logic

To answer these questions we need to look at the history of the reception of the Hindu Syllogism and how to correct the colonialist interpretation of it.

In the study of classical Indian logic from the Anglo-European point of view it is well known that the Hindu Syllogism received a great deal of criticism and was often presented as being inferior to the Aristotelian Syllogism. Jonardon Ganeri (2001) has compiled a list of some of these critiques in his work on Indian Logic:

[Western philosophy] looks outward and is concerned with Logic and with the presuppositions of scientific knowledge; [Indian philosophy] looks inward, into the ‘deep yet dazzling darkness’ of the mystical consciousness ( as quoted in Ganeri, 2001 , p. 1).