Research Objectives: The Compass of Your Study

Table of contents

- 1 Definition and Purpose of Setting Clear Research Objectives

- 2 How Research Objectives Fit into the Overall Research Framework

- 3 Types of Research Objectives

- 4 Aligning Objectives with Research Questions and Hypotheses

- 5 Role of Research Objectives in Various Research Phases

- 6.1 Key characteristics of well-defined research objectives

- 6.2 Step-by-Step Guide on How to Formulate Both General and Specific Research Objectives

- 6.3 How to Know When Your Objectives Need Refinement

- 7 Research Objectives Examples in Different Fields

- 8 Conclusion

Embarking on a research journey without clear objectives is like navigating the sea without a compass. This article delves into the essence of establishing precise research objectives, serving as the guiding star for your scholarly exploration.

We will unfold the layers of how the objective of study not only defines the scope of your research but also directs every phase of the research process, from formulating research questions to interpreting research findings. By bridging theory with practical examples, we aim to illuminate the path to crafting effective research objectives that are both ambitious and attainable. Let’s chart the course to a successful research voyage, exploring the significance, types, and formulation of research paper objectives.

Definition and Purpose of Setting Clear Research Objectives

Defining the research objectives includes which two tasks? Research objectives are clear and concise statements that outline what you aim to achieve through your study. They are the foundation for determining your research scope, guiding your data collection methods, and shaping your analysis. The purpose of research proposal and setting clear objectives in it is to ensure that your research efforts are focused and efficient, and to provide a roadmap that keeps your study aligned with its intended outcomes.

To define the research objective at the outset, researchers can avoid the pitfalls of scope creep, where the study’s focus gradually broadens beyond its initial boundaries, leading to wasted resources and time. Clear objectives facilitate communication with stakeholders, such as funding bodies, academic supervisors, and the broader academic community, by succinctly conveying the study’s goals and significance. Furthermore, they help in the formulation of precise research questions and hypotheses, making the research process more systematic and organized. Yet, it is not always easy. For this reason, PapersOwl is always ready to help. Lastly, clear research objectives enable the researcher to critically assess the study’s progress and outcomes against predefined benchmarks, ensuring the research stays on track and delivers meaningful results.

How Research Objectives Fit into the Overall Research Framework

Research objectives are integral to the research framework as the nexus between the research problem, questions, and hypotheses. They translate the broad goals of your study into actionable steps, ensuring every aspect of your research is purposefully aligned towards addressing the research problem. This alignment helps in structuring the research design and methodology, ensuring that each component of the study is geared towards answering the core questions derived from the objectives. Creating such a difficult piece may take a lot of time. If you need it to be accurate yet fast delivered, consider getting professional research paper writing help whenever the time comes. It also aids in the identification and justification of the research methods and tools used for data collection and analysis, aligning them with the objectives to enhance the validity and reliability of the findings.

Furthermore, by setting clear objectives, researchers can more effectively evaluate the impact and significance of their work in contributing to existing knowledge. Additionally, research objectives guide literature review, enabling researchers to focus their examination on relevant studies and theoretical frameworks that directly inform their research goals.

Types of Research Objectives

In the landscape of research, setting objectives is akin to laying down the tracks for a train’s journey, guiding it towards its destination. Constructing these tracks involves defining two main types of objectives: general and specific. Each serves a unique purpose in guiding the research towards its ultimate goals, with general objectives providing the broad vision and specific objectives outlining the concrete steps needed to fulfill that vision. Together, they form a cohesive blueprint that directs the focus of the study, ensuring that every effort contributes meaningfully to the overarching research aims.

- General objectives articulate the overarching goals of your study. They are broad, setting the direction for your research without delving into specifics. These objectives capture what you wish to explore or contribute to existing knowledge.

- Specific objectives break down the general objectives into measurable outcomes. They are precise, detailing the steps needed to achieve the broader goals of your study. They often correspond to different aspects of your research question , ensuring a comprehensive approach to your study.

To illustrate, consider a research project on the impact of digital marketing on consumer behavior. A general objective might be “to explore the influence of digital marketing on consumer purchasing decisions.” Specific objectives could include “to assess the effectiveness of social media advertising in enhancing brand awareness” and “to evaluate the impact of email marketing on customer loyalty.”

Aligning Objectives with Research Questions and Hypotheses

The harmony between what research objectives should be, questions, and hypotheses is critical. Objectives define what you aim to achieve; research questions specify what you seek to understand, and hypotheses predict the expected outcomes.

This alignment ensures a coherent and focused research endeavor. Achieving it necessitates a thoughtful consideration of how each component interrelates, ensuring that the objectives are not only ambitious but also directly answerable through the research questions and testable via the hypotheses. This interconnectedness facilitates a streamlined approach to the research process, enabling researchers to systematically address each aspect of their study in a logical sequence. Moreover, it enhances the clarity and precision of the research, making it easier for peers and stakeholders to grasp the study’s direction and potential contributions.

Role of Research Objectives in Various Research Phases

Throughout the research process, objectives guide your choices and strategies – from selecting the appropriate research design and methods to analyzing data and interpreting results. They are the criteria against which you measure the success of your study. In the initial stages, research objectives inform the selection of a topic, helping to narrow down a broad area of interest into a focused question that can be explored in depth. During the methodology phase, they dictate the type of data needed and the best methods for obtaining that data, ensuring that every step taken is purposeful and aligned with the study’s goals. As the research progresses, objectives provide a framework for analyzing the collected data, guiding the researcher in identifying patterns, drawing conclusions, and making informed decisions.

Crafting Effective Research Objectives

The effective objective of research is pivotal in laying the groundwork for a successful investigation. These objectives clarify the focus of your study and determine its direction and scope. Ensuring that your objectives are well-defined and aligned with the SMART criteria is crucial for setting a strong foundation for your research.

Key characteristics of well-defined research objectives

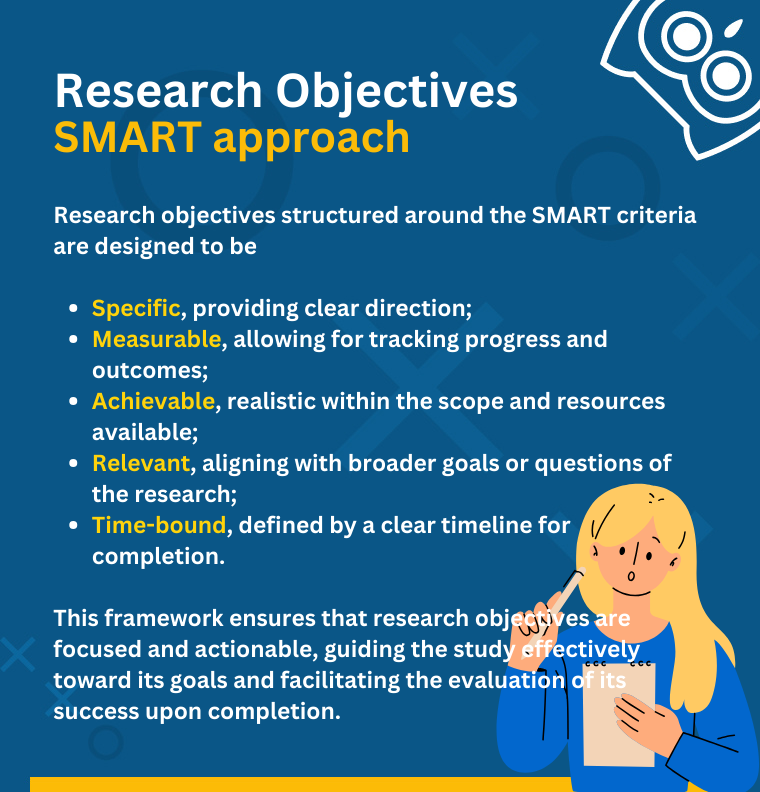

Well-defined research objectives are characterized by the SMART criteria – Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. Specific objectives clearly define what you plan to achieve, eliminating any ambiguity. Measurable objectives allow you to track progress and assess the outcome. Achievable objectives are realistic, considering the research sources and time available. Relevant objectives align with the broader goals of your field or research question. Finally, Time-bound objectives have a clear timeline for completion, adding urgency and a schedule to your work.

Step-by-Step Guide on How to Formulate Both General and Specific Research Objectives

So lets get to the part, how to write research objectives properly?

- Understand the issue or gap in existing knowledge your study aims to address.

- Gain insights into how similar challenges have been approached to refine your objectives.

- Articulate the broad goal of research based on your understanding of the problem.

- Detail the specific aspects of your research, ensuring they are actionable and measurable.

How to Know When Your Objectives Need Refinement

Your objectives of research may require refinement if they lack clarity, feasibility, or alignment with the research problem. If you find yourself struggling to design experiments or methods that directly address your objectives, or if the objectives seem too broad or not directly related to your research question, it’s likely time for refinement. Additionally, objectives in research proposal that do not facilitate a clear measurement of success indicate a need for a more precise definition. Refinement involves ensuring that each objective is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound, enhancing your research’s overall focus and impact.

Research Objectives Examples in Different Fields

The application of research objectives spans various academic disciplines, each with its unique focus and methodologies. To illustrate how the objectives of the study guide a research paper across different fields, here are some research objective examples:

- In Health Sciences , a research aim may be to “determine the efficacy of a new vaccine in reducing the incidence of a specific disease among a target population within one year.” This objective is specific (efficacy of a new vaccine), measurable (reduction in disease incidence), achievable (with the right study design and sample size), relevant (to public health), and time-bound (within one year).

- In Environmental Studies , the study objectives could be “to assess the impact of air pollution on urban biodiversity over a decade.” This reflects a commitment to understanding the long-term effects of human activities on urban ecosystems, emphasizing the need for sustainable urban planning.

- In Economics , an example objective of a study might be “to analyze the relationship between fiscal policies and unemployment rates in developing countries over the past twenty years.” This seeks to explore macroeconomic trends and inform policymaking, highlighting the role of economic research study in societal development.

These examples of research objectives describe the versatility and significance of research objectives in guiding scholarly inquiry across different domains. By setting clear, well-defined objectives, researchers can ensure their studies are focused and impactful and contribute valuable knowledge to their respective fields.

Defining research studies objectives and problem statement is not just a preliminary step, but a continuous guiding force throughout the research journey. These goals of research illuminate the path forward and ensure that every stride taken is meaningful and aligned with the ultimate goals of the inquiry. Whether through the meticulous application of the SMART criteria or the strategic alignment with research questions and hypotheses, the rigor in crafting and refining these objectives underscores the integrity and relevance of the research. As scholars venture into the vast terrains of knowledge, the clarity, and precision of their objectives serve as beacons of light, steering their explorations toward discoveries that advance academic discourse and resonate with the broader societal needs.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

- Defining Research Objectives: How To Write Them

Almost all industries use research for growth and development. Research objectives are how researchers ensure that their study has direction and makes a significant contribution to growing an industry or niche.

Research objectives provide a clear and concise statement of what the researcher wants to find out. As a researcher, you need to clearly outline and define research objectives to guide the research process and ensure that the study is relevant and generates the impact you want.

In this article, we will explore research objectives and how to leverage them to achieve successful research studies.

What Are Research Objectives?

Research objectives are what you want to achieve through your research study. They guide your research process and help you focus on the most important aspects of your topic.

You can also define the scope of your study and set realistic and attainable study goals with research objectives. For example, with clear research objectives, your study focuses on the specific goals you want to achieve and prevents you from spending time and resources collecting unnecessary data.

However, sticking to research objectives isn’t always easy, especially in broad or unconventional research. This is why most researchers follow the SMART criteria when defining their research objectives.

Understanding SMART Criteria in Research

Think of research objectives as a roadmap to achieving your research goals, with the SMART criteria as your navigator on the map.

SMART stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. These criteria help you ensure that your research objectives are clear, specific, realistic, meaningful, and time-bound.

Here’s a breakdown of the SMART Criteria:

Specific : Your research objectives should be clear: what do you want to achieve, why do you want to achieve it, and how do you plan to achieve it? Avoid vague or broad statements that don’t provide enough direction for your research.

Measurable : Your research objectives should have metrics that help you track your progress and measure your results. Also, ensure the metrics are measurable with data to verify them.

Achievable : Your research objectives should be within your research scope, timeframe, and budget. Also, set goals that are challenging but not impossible.

Relevant: Your research objectives should be in line with the goal and significance of your study. Also, ensure that the objectives address a specific issue or knowledge gap that is interesting and relevant to your industry or niche.

Time-bound : Your research objectives should have a specific deadline or timeframe for completion. This will help you carefully set a schedule for your research activities and milestones and monitor your study progress.

Characteristics of Effective Research Objectives

Clarity : Your objectives should be clear and unambiguous so that anyone who reads them can understand what you intend to do. Avoid vague or general terms that could be taken out of context.

Specificity : Your objectives should be specific and address the research questions that you have formulated. Do not use broad or narrow objectives as they may restrict your field of research or make your research irrelevant.

Measurability : Define your metrics with indicators or metrics that help you determine if you’ve accomplished your goals or not. This will ensure you are tracking the research progress and making interventions when needed.

Also, do use objectives that are subjective or based on personal opinions, as they may be difficult to accurately verify and measure.

Achievability : Your objectives should be realistic and attainable, given the resources and time available for your research project. You should set objectives that match your skills and capabilities, they can be difficult but not so hard that they are realistically unachievable.

For example, setting very difficult make you lose confidence, and abandon your research. Also, setting very simple objectives could demotivate you and prevent you from closing the knowledge gap or making significant contributions to your field with your research.

Relevance : Your objectives should be relevant to your research topic and contribute to the existing knowledge in your field. Avoid objectives that are unrelated or insignificant, as they may waste your time or resources.

Time-bound : Your objectives should be time-bound and specify when you will complete them. Have a realistic and flexible timeframe for achieving your objectives, and track your progress with it.

Steps to Writing Research Objectives

Identify the research questions.

The first step in writing effective research objectives is to identify the research questions that you are trying to answer. Research questions help you narrow down your topic and identify the gaps or problems that you want to address with your research.

For example, if you are interested in the impact of technology on children’s development, your research questions could be:

- What is the relationship between technology use and academic performance among children?

- Are children who use technology more likely to do better in school than those who do not?

- What is the social and psychological impact of technology use on children?

Brainstorm Objectives

Once you have your research questions, you can brainstorm possible objectives that relate to them. Objectives are more specific than research questions, and they tell you what you want to achieve or learn in your research.

You can use verbs such as analyze, compare, evaluate, explore, investigate, etc. to express your objectives. Also, try to generate as many objectives as possible, without worrying about their quality or feasibility at this stage.

Prioritize Objectives

Once you’ve brainstormed your objectives, you’ll need to prioritize them based on their relevance and feasibility. Relevance is how relevant the objective is to your research topic and how well it fits into your overall research objective.

Feasibility is how realistic and feasible the objective is compared to the time, money, and expertise you have. You can create a matrix or ranking system to organize your objectives and pick the ones that matter the most.

Refine Objectives

The next step is to refine and revise your objectives to ensure clarity and specificity. Start by ensuring that your objectives are consistent and coherent with each other and with your research questions.

Make Objectives SMART

A useful way to refine your objectives is to make them SMART, which stands for specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

- Specific : Objectives should clearly state what you hope to achieve.

- Measurable : They should be able to be quantified or evaluated.

- Achievable : realistic and within the scope of the research study.

- Relevant : They should be directly related to the research questions.

- Time-bound : specific timeframe for research completion.

Review and Finalize Objectives

The final step is to review your objectives for coherence and alignment with your research questions and aim. Ensure your objectives are logically connected and consistent with each other and with the purpose of your study.

You also need to check that your objectives are not too broad or too narrow, too easy or too hard, too many or too few. You can use a checklist or a rubric to evaluate your objectives and make modifications.

Examples of Well-Written Research Objectives

Example 1- Psychology

Research question: What are the effects of social media use on teenagers’ mental health?

Objective : To determine the relationship between the amount of time teenagers in the US spend on social media and their levels of anxiety and depression before and after using social media.

What Makes the Research Objective SMART?

The research objective is specific because it clearly states what the researcher hopes to achieve. It is measurable because it can be quantified by measuring the levels of anxiety and depression in teenagers.

Also, the objective is achievable because the researcher can collect enough data to answer the research question. It is relevant because it is directly related to the research question. It is time-bound because it has a specific deadline for completion.

Example 2- Marketing

Research question : How can a company increase its brand awareness by 10%?

Objective : To develop a marketing strategy that will increase the company’s sales by 10% within the next quarter.

How Is this Research Objective SMART?

The research states what the researcher hopes to achieve ( Specific ). You can also measure the company’s reach before and after the marketing plan is implemented ( Measurable ).

The research objective is also achievable because you can develop a marketing plan that will increase awareness by 10% within the timeframe. The objective is directly related to the research question ( Relevant ). It is also time-bound because it has a specific deadline for completion.

Research objectives are a well-designed roadmap to completing and achieving your overall research goal.

However, research goals are only effective if they are well-defined and backed up with the best practices such as the SMART criteria. Properly defining research objectives will help you plan and conduct your research project effectively and efficiently.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- research goals

- research objectives

- research roadmap

- smart goals

- SMART research objectives

- Moradeke Owa

You may also like:

Projective Techniques In Surveys: Definition, Types & Pros & Cons

Introduction When you’re conducting a survey, you need to find out what people think about things. But how do you get an accurate and...

Desk Research: Definition, Types, Application, Pros & Cons

If you are looking for a way to conduct a research study while optimizing your resources, desk research is a great option. Desk research...

Research Summary: What Is It & How To Write One

Introduction A research summary is a requirement during academic research and sometimes you might need to prepare a research summary...

Subgroup Analysis: What It Is + How to Conduct It

Introduction Clinical trials are an integral part of the drug development process. They aim to assess the safety and efficacy of a new...

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

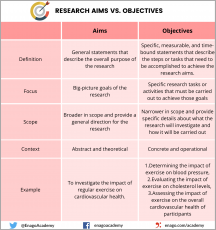

Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

The “Golden Thread” Explained Simply (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

The research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.

Research Aims: What are they?

Simply put, the research aim(s) is a statement that reflects the broad overarching goal (s) of the research project. Research aims are fairly high-level (low resolution) as they outline the general direction of the research and what it’s trying to achieve .

Research Aims: Examples

True to the name, research aims usually start with the wording “this research aims to…”, “this research seeks to…”, and so on. For example:

“This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.” “This study sets out to assess the interaction between student support and self-care on well-being in engineering graduate students”

As you can see, these research aims provide a high-level description of what the study is about and what it seeks to achieve. They’re not hyper-specific or action-oriented, but they’re clear about what the study’s focus is and what is being investigated.

Need a helping hand?

Research Objectives: What are they?

The research objectives take the research aims and make them more practical and actionable . In other words, the research objectives showcase the steps that the researcher will take to achieve the research aims.

The research objectives need to be far more specific (higher resolution) and actionable than the research aims. In fact, it’s always a good idea to craft your research objectives using the “SMART” criteria. In other words, they should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound”.

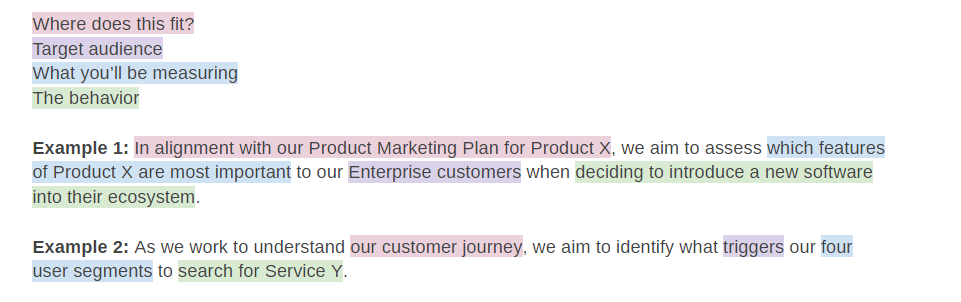

Research Objectives: Examples

Let’s look at two examples of research objectives. We’ll stick with the topic and research aims we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic:

To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation. To assess employee perceptions of digital transformation in retail HR. To identify the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR.

And for the student wellness topic:

To determine whether student self-care predicts the well-being score of engineering graduate students. To determine whether student support predicts the well-being score of engineering students. To assess the interaction between student self-care and student support when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students.

As you can see, these research objectives clearly align with the previously mentioned research aims and effectively translate the low-resolution aims into (comparatively) higher-resolution objectives and action points . They give the research project a clear focus and present something that resembles a research-based “to-do” list.

Research Questions: What are they?

Finally, we arrive at the all-important research questions. The research questions are, as the name suggests, the key questions that your study will seek to answer . Simply put, they are the core purpose of your dissertation, thesis, or research project. You’ll present them at the beginning of your document (either in the introduction chapter or literature review chapter) and you’ll answer them at the end of your document (typically in the discussion and conclusion chapters).

The research questions will be the driving force throughout the research process. For example, in the literature review chapter, you’ll assess the relevance of any given resource based on whether it helps you move towards answering your research questions. Similarly, your methodology and research design will be heavily influenced by the nature of your research questions. For instance, research questions that are exploratory in nature will usually make use of a qualitative approach, whereas questions that relate to measurement or relationship testing will make use of a quantitative approach.

Let’s look at some examples of research questions to make this more tangible.

Research Questions: Examples

Again, we’ll stick with the research aims and research objectives we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic (which would be qualitative in nature):

How do employees perceive digital transformation in retail HR? What are the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR?

And for the student wellness topic (which would be quantitative in nature):

Does student self-care predict the well-being scores of engineering graduate students? Does student support predict the well-being scores of engineering students? Do student self-care and student support interact when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students?

You’ll probably notice that there’s quite a formulaic approach to this. In other words, the research questions are basically the research objectives “converted” into question format. While that is true most of the time, it’s not always the case. For example, the first research objective for the digital transformation topic was more or less a step on the path toward the other objectives, and as such, it didn’t warrant its own research question.

So, don’t rush your research questions and sloppily reword your objectives as questions. Carefully think about what exactly you’re trying to achieve (i.e. your research aim) and the objectives you’ve set out, then craft a set of well-aligned research questions . Also, keep in mind that this can be a somewhat iterative process , where you go back and tweak research objectives and aims to ensure tight alignment throughout the golden thread.

The importance of strong alignment

Alignment is the keyword here and we have to stress its importance . Simply put, you need to make sure that there is a very tight alignment between all three pieces of the golden thread. If your research aims and research questions don’t align, for example, your project will be pulling in different directions and will lack focus . This is a common problem students face and can cause many headaches (and tears), so be warned.

Take the time to carefully craft your research aims, objectives and research questions before you run off down the research path. Ideally, get your research supervisor/advisor to review and comment on your golden thread before you invest significant time into your project, and certainly before you start collecting data .

Recap: The golden thread

In this post, we unpacked the golden thread of research, consisting of the research aims , research objectives and research questions . You can jump back to any section using the links below.

As always, feel free to leave a comment below – we always love to hear from you. Also, if you’re interested in 1-on-1 support, take a look at our private coaching service here.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

39 Comments

Thank you very much for your great effort put. As an Undergraduate taking Demographic Research & Methodology, I’ve been trying so hard to understand clearly what is a Research Question, Research Aim and the Objectives in a research and the relationship between them etc. But as for now I’m thankful that you’ve solved my problem.

Well appreciated. This has helped me greatly in doing my dissertation.

An so delighted with this wonderful information thank you a lot.

so impressive i have benefited a lot looking forward to learn more on research.

I am very happy to have carefully gone through this well researched article.

Infact,I used to be phobia about anything research, because of my poor understanding of the concepts.

Now,I get to know that my research question is the same as my research objective(s) rephrased in question format.

I please I would need a follow up on the subject,as I intends to join the team of researchers. Thanks once again.

Thanks so much. This was really helpful.

I know you pepole have tried to break things into more understandable and easy format. And God bless you. Keep it up

i found this document so useful towards my study in research methods. thanks so much.

This is my 2nd read topic in your course and I should commend the simplified explanations of each part. I’m beginning to understand and absorb the use of each part of a dissertation/thesis. I’ll keep on reading your free course and might be able to avail the training course! Kudos!

Thank you! Better put that my lecture and helped to easily understand the basics which I feel often get brushed over when beginning dissertation work.

This is quite helpful. I like how the Golden thread has been explained and the needed alignment.

This is quite helpful. I really appreciate!

The article made it simple for researcher students to differentiate between three concepts.

Very innovative and educational in approach to conducting research.

I am very impressed with all these terminology, as I am a fresh student for post graduate, I am highly guided and I promised to continue making consultation when the need arise. Thanks a lot.

A very helpful piece. thanks, I really appreciate it .

Very well explained, and it might be helpful to many people like me.

Wish i had found this (and other) resource(s) at the beginning of my PhD journey… not in my writing up year… 😩 Anyways… just a quick question as i’m having some issues ordering my “golden thread”…. does it matter in what order you mention them? i.e., is it always first aims, then objectives, and finally the questions? or can you first mention the research questions and then the aims and objectives?

Thank you for a very simple explanation that builds upon the concepts in a very logical manner. Just prior to this, I read the research hypothesis article, which was equally very good. This met my primary objective.

My secondary objective was to understand the difference between research questions and research hypothesis, and in which context to use which one. However, I am still not clear on this. Can you kindly please guide?

In research, a research question is a clear and specific inquiry that the researcher wants to answer, while a research hypothesis is a tentative statement or prediction about the relationship between variables or the expected outcome of the study. Research questions are broader and guide the overall study, while hypotheses are specific and testable statements used in quantitative research. Research questions identify the problem, while hypotheses provide a focus for testing in the study.

Exactly what I need in this research journey, I look forward to more of your coaching videos.

This helped a lot. Thanks so much for the effort put into explaining it.

What data source in writing dissertation/Thesis requires?

What is data source covers when writing dessertation/thesis

This is quite useful thanks

I’m excited and thankful. I got so much value which will help me progress in my thesis.

where are the locations of the reserch statement, research objective and research question in a reserach paper? Can you write an ouline that defines their places in the researh paper?

Very helpful and important tips on Aims, Objectives and Questions.

Thank you so much for making research aim, research objectives and research question so clear. This will be helpful to me as i continue with my thesis.

Thanks much for this content. I learned a lot. And I am inspired to learn more. I am still struggling with my preparation for dissertation outline/proposal. But I consistently follow contents and tutorials and the new FB of GRAD Coach. Hope to really become confident in writing my dissertation and successfully defend it.

As a researcher and lecturer, I find splitting research goals into research aims, objectives, and questions is unnecessarily bureaucratic and confusing for students. For most biomedical research projects, including ‘real research’, 1-3 research questions will suffice (numbers may differ by discipline).

Awesome! Very important resources and presented in an informative way to easily understand the golden thread. Indeed, thank you so much.

Well explained

The blog article on research aims, objectives, and questions by Grad Coach is a clear and insightful guide that aligns with my experiences in academic research. The article effectively breaks down the often complex concepts of research aims and objectives, providing a straightforward and accessible explanation. Drawing from my own research endeavors, I appreciate the practical tips offered, such as the need for specificity and clarity when formulating research questions. The article serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers, offering a concise roadmap for crafting well-defined research goals and objectives. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced researcher, this article provides practical insights that contribute to the foundational aspects of a successful research endeavor.

A great thanks for you. it is really amazing explanation. I grasp a lot and one step up to research knowledge.

I really found these tips helpful. Thank you very much Grad Coach.

I found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing this.

thank you so much, the explanation and examples are really helpful

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Objectives – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Objectives

Research objectives refer to the specific goals or aims of a research study. They provide a clear and concise description of what the researcher hopes to achieve by conducting the research . The objectives are typically based on the research questions and hypotheses formulated at the beginning of the study and are used to guide the research process.

Types of Research Objectives

Here are the different types of research objectives in research:

- Exploratory Objectives: These objectives are used to explore a topic, issue, or phenomenon that has not been studied in-depth before. The aim of exploratory research is to gain a better understanding of the subject matter and generate new ideas and hypotheses .

- Descriptive Objectives: These objectives aim to describe the characteristics, features, or attributes of a particular population, group, or phenomenon. Descriptive research answers the “what” questions and provides a snapshot of the subject matter.

- Explanatory Objectives : These objectives aim to explain the relationships between variables or factors. Explanatory research seeks to identify the cause-and-effect relationships between different phenomena.

- Predictive Objectives: These objectives aim to predict future events or outcomes based on existing data or trends. Predictive research uses statistical models to forecast future trends or outcomes.

- Evaluative Objectives : These objectives aim to evaluate the effectiveness or impact of a program, intervention, or policy. Evaluative research seeks to assess the outcomes or results of a particular intervention or program.

- Prescriptive Objectives: These objectives aim to provide recommendations or solutions to a particular problem or issue. Prescriptive research identifies the best course of action based on the results of the study.

- Diagnostic Objectives : These objectives aim to identify the causes or factors contributing to a particular problem or issue. Diagnostic research seeks to uncover the underlying reasons for a particular phenomenon.

- Comparative Objectives: These objectives aim to compare two or more groups, populations, or phenomena to identify similarities and differences. Comparative research is used to determine which group or approach is more effective or has better outcomes.

- Historical Objectives: These objectives aim to examine past events, trends, or phenomena to gain a better understanding of their significance and impact. Historical research uses archival data, documents, and records to study past events.

- Ethnographic Objectives : These objectives aim to understand the culture, beliefs, and practices of a particular group or community. Ethnographic research involves immersive fieldwork and observation to gain an insider’s perspective of the group being studied.

- Action-oriented Objectives: These objectives aim to bring about social or organizational change. Action-oriented research seeks to identify practical solutions to social problems and to promote positive change in society.

- Conceptual Objectives: These objectives aim to develop new theories, models, or frameworks to explain a particular phenomenon or set of phenomena. Conceptual research seeks to provide a deeper understanding of the subject matter by developing new theoretical perspectives.

- Methodological Objectives: These objectives aim to develop and improve research methods and techniques. Methodological research seeks to advance the field of research by improving the validity, reliability, and accuracy of research methods and tools.

- Theoretical Objectives : These objectives aim to test and refine existing theories or to develop new theoretical perspectives. Theoretical research seeks to advance the field of knowledge by testing and refining existing theories or by developing new theoretical frameworks.

- Measurement Objectives : These objectives aim to develop and validate measurement instruments, such as surveys, questionnaires, and tests. Measurement research seeks to improve the quality and reliability of data collection and analysis by developing and testing new measurement tools.

- Design Objectives : These objectives aim to develop and refine research designs, such as experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational designs. Design research seeks to improve the quality and validity of research by developing and testing new research designs.

- Sampling Objectives: These objectives aim to develop and refine sampling techniques, such as probability and non-probability sampling methods. Sampling research seeks to improve the representativeness and generalizability of research findings by developing and testing new sampling techniques.

How to Write Research Objectives

Writing clear and concise research objectives is an important part of any research project, as it helps to guide the study and ensure that it is focused and relevant. Here are some steps to follow when writing research objectives:

- Identify the research problem : Before you can write research objectives, you need to identify the research problem you are trying to address. This should be a clear and specific problem that can be addressed through research.

- Define the research questions : Based on the research problem, define the research questions you want to answer. These questions should be specific and should guide the research process.

- Identify the variables : Identify the key variables that you will be studying in your research. These are the factors that you will be measuring, manipulating, or analyzing to answer your research questions.

- Write specific objectives: Write specific, measurable objectives that will help you answer your research questions. These objectives should be clear and concise and should indicate what you hope to achieve through your research.

- Use the SMART criteria: To ensure that your research objectives are well-defined and achievable, use the SMART criteria. This means that your objectives should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound.

- Revise and refine: Once you have written your research objectives, revise and refine them to ensure that they are clear, concise, and achievable. Make sure that they align with your research questions and variables, and that they will help you answer your research problem.

Example of Research Objectives

Examples of research objectives Could be:

Research Objectives for the topic of “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employment”:

- To investigate the effects of the adoption of AI on employment trends across various industries and occupations.

- To explore the potential for AI to create new job opportunities and transform existing roles in the workforce.

- To examine the social and economic implications of the widespread use of AI for employment, including issues such as income inequality and access to education and training.

- To identify the skills and competencies that will be required for individuals to thrive in an AI-driven workplace, and to explore the role of education and training in developing these skills.

- To evaluate the ethical and legal considerations surrounding the use of AI for employment, including issues such as bias, privacy, and the responsibility of employers and policymakers to protect workers’ rights.

When to Write Research Objectives

- At the beginning of a research project : Research objectives should be identified and written down before starting a research project. This helps to ensure that the project is focused and that data collection and analysis efforts are aligned with the intended purpose of the research.

- When refining research questions: Writing research objectives can help to clarify and refine research questions. Objectives provide a more concrete and specific framework for addressing research questions, which can improve the overall quality and direction of a research project.

- After conducting a literature review : Conducting a literature review can help to identify gaps in knowledge and areas that require further research. Writing research objectives can help to define and focus the research effort in these areas.

- When developing a research proposal: Research objectives are an important component of a research proposal. They help to articulate the purpose and scope of the research, and provide a clear and concise summary of the expected outcomes and contributions of the research.

- When seeking funding for research: Funding agencies often require a detailed description of research objectives as part of a funding proposal. Writing clear and specific research objectives can help to demonstrate the significance and potential impact of a research project, and increase the chances of securing funding.

- When designing a research study : Research objectives guide the design and implementation of a research study. They help to identify the appropriate research methods, sampling strategies, data collection and analysis techniques, and other relevant aspects of the study design.

- When communicating research findings: Research objectives provide a clear and concise summary of the main research questions and outcomes. They are often included in research reports and publications, and can help to ensure that the research findings are communicated effectively and accurately to a wide range of audiences.

- When evaluating research outcomes : Research objectives provide a basis for evaluating the success of a research project. They help to measure the degree to which research questions have been answered and the extent to which research outcomes have been achieved.

- When conducting research in a team : Writing research objectives can facilitate communication and collaboration within a research team. Objectives provide a shared understanding of the research purpose and goals, and can help to ensure that team members are working towards a common objective.

Purpose of Research Objectives

Some of the main purposes of research objectives include:

- To clarify the research question or problem : Research objectives help to define the specific aspects of the research question or problem that the study aims to address. This makes it easier to design a study that is focused and relevant.

- To guide the research design: Research objectives help to determine the research design, including the research methods, data collection techniques, and sampling strategy. This ensures that the study is structured and efficient.

- To measure progress : Research objectives provide a way to measure progress throughout the research process. They help the researcher to evaluate whether they are on track and meeting their goals.

- To communicate the research goals : Research objectives provide a clear and concise description of the research goals. This helps to communicate the purpose of the study to other researchers, stakeholders, and the general public.

Advantages of Research Objectives

Here are some advantages of having well-defined research objectives:

- Focus : Research objectives help to focus the research effort on specific areas of inquiry. By identifying clear research questions, the researcher can narrow down the scope of the study and avoid getting sidetracked by irrelevant information.

- Clarity : Clearly stated research objectives provide a roadmap for the research study. They provide a clear direction for the research, making it easier for the researcher to stay on track and achieve their goals.

- Measurability : Well-defined research objectives provide measurable outcomes that can be used to evaluate the success of the research project. This helps to ensure that the research is effective and that the research goals are achieved.

- Feasibility : Research objectives help to ensure that the research project is feasible. By clearly defining the research goals, the researcher can identify the resources required to achieve those goals and determine whether those resources are available.

- Relevance : Research objectives help to ensure that the research study is relevant and meaningful. By identifying specific research questions, the researcher can ensure that the study addresses important issues and contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write Research Objectives

3-minute read

- 22nd November 2021

Writing a research paper, thesis, or dissertation ? If so, you’ll want to state your research objectives in the introduction of your paper to make it clear to your readers what you’re trying to accomplish. But how do you write effective research objectives? In this post, we’ll look at two key topics to help you do this:

- How to use your research aims as a basis for developing objectives.

- How to use SMART criteria to refine your research objectives.

For more advice on how to write strong research objectives, see below.

Research Aims and Objectives

There is an important difference between research aims and research objectives:

- A research aim defines the main purpose of your research. As such, you can think of your research aim as answering the question “What are you doing?”

- Research objectives (as most studies will have more than one) are the steps you will take to fulfil your aims. As such, your objectives should answer the question “How are you conducting your research?”

For instance, an example research aim could be:

This study will investigate the link between dehydration and the incidence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in intensive care patients in Australia.

To develop a set of research objectives, you would then break down the various steps involved in meeting said aim. For example:

This study will investigate the link between dehydration and the incidence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in intensive care patients in Australia. To achieve this, the study objectives w ill include:

- Replicat ing a small Singaporean study into the role of dehydration in UTIs in hospital patients (Sepe, 2018) in a larger Australian cohort.

- Trialing the use of intravenous fluids for intensive care patients to prevent dehydration.

- Assessing the relationship between the age of patients and quantities of intravenous fluids needed to counter dehydration.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Note that the objectives don’t go into any great detail here. The key is to briefly summarize each component of your study. You can save details for how you will conduct the research for the methodology section of your paper.

Make Your Research Objectives SMART

A great way to refine your research objectives is to use SMART criteria . Borrowed from the world of project management, there are many versions of this system. However, we’re going to focus on developing specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timebound objectives.

In other words, a good research objective should be all of the following:

- S pecific – Is the objective clear and well-defined?

- M easurable – How will you know when the objective has been achieved? Is there a way to measure the thing you’re seeking to do?

- A chievable – Do you have the support and resources necessary to undertake this action? Are you being overly ambitious with this objective?

- R elevant – Is this objective vital for fulfilling your research aim?

- T imebound – Can this action be realistically undertaken in the time you have?

If you follow this system, your research objectives will be much stronger.

Expert Research Proofreading

Whatever your research aims and objectives, make sure to have your academic writing proofread by the experts!

Our academic editors can help you with research papers and proposals , as well as any other scholarly document you need checking. And this will help to ensure that your academic writing is always clear, concise, and precise.

Submit a free sample document today to trial our services and find out more.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

How to insert a text box in a google doc.

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Aims and Objectives – A Guide for Academic Writing

- Doing a PhD

One of the most important aspects of a thesis, dissertation or research paper is the correct formulation of the aims and objectives. This is because your aims and objectives will establish the scope, depth and direction that your research will ultimately take. An effective set of aims and objectives will give your research focus and your reader clarity, with your aims indicating what is to be achieved, and your objectives indicating how it will be achieved.

Introduction

There is no getting away from the importance of the aims and objectives in determining the success of your research project. Unfortunately, however, it is an aspect that many students struggle with, and ultimately end up doing poorly. Given their importance, if you suspect that there is even the smallest possibility that you belong to this group of students, we strongly recommend you read this page in full.

This page describes what research aims and objectives are, how they differ from each other, how to write them correctly, and the common mistakes students make and how to avoid them. An example of a good aim and objectives from a past thesis has also been deconstructed to help your understanding.

What Are Aims and Objectives?

Research aims.

A research aim describes the main goal or the overarching purpose of your research project.

In doing so, it acts as a focal point for your research and provides your readers with clarity as to what your study is all about. Because of this, research aims are almost always located within its own subsection under the introduction section of a research document, regardless of whether it’s a thesis , a dissertation, or a research paper .

A research aim is usually formulated as a broad statement of the main goal of the research and can range in length from a single sentence to a short paragraph. Although the exact format may vary according to preference, they should all describe why your research is needed (i.e. the context), what it sets out to accomplish (the actual aim) and, briefly, how it intends to accomplish it (overview of your objectives).

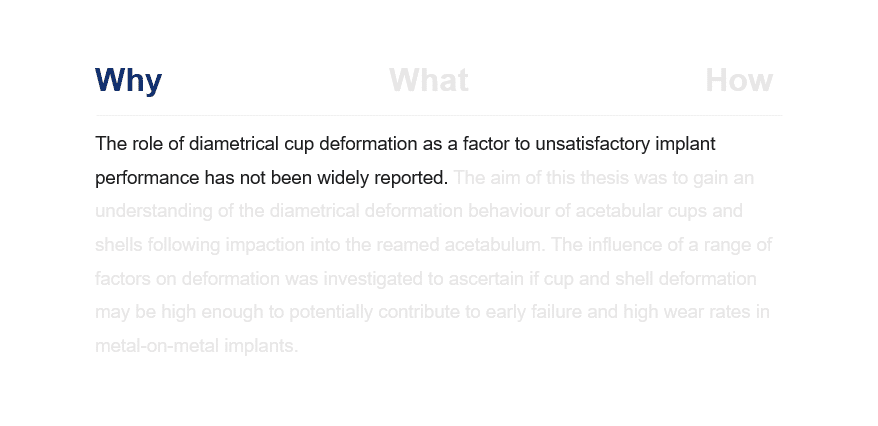

To give an example, we have extracted the following research aim from a real PhD thesis:

Example of a Research Aim

The role of diametrical cup deformation as a factor to unsatisfactory implant performance has not been widely reported. The aim of this thesis was to gain an understanding of the diametrical deformation behaviour of acetabular cups and shells following impaction into the reamed acetabulum. The influence of a range of factors on deformation was investigated to ascertain if cup and shell deformation may be high enough to potentially contribute to early failure and high wear rates in metal-on-metal implants.

Note: Extracted with permission from thesis titled “T he Impact And Deformation Of Press-Fit Metal Acetabular Components ” produced by Dr H Hothi of previously Queen Mary University of London.

Research Objectives

Where a research aim specifies what your study will answer, research objectives specify how your study will answer it.

They divide your research aim into several smaller parts, each of which represents a key section of your research project. As a result, almost all research objectives take the form of a numbered list, with each item usually receiving its own chapter in a dissertation or thesis.

Following the example of the research aim shared above, here are it’s real research objectives as an example:

Example of a Research Objective

- Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

- Investigate the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup.

- Determine the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types.

- Investigate the influence of non-uniform cup support and varying the orientation of the component in the cavity on deformation.

- Examine the influence of errors during reaming of the acetabulum which introduce ovality to the cavity.

- Determine the relationship between changes in the geometry of the component and deformation for different cup designs.

- Develop three dimensional pelvis models with non-uniform bone material properties from a range of patients with varying bone quality.

- Use the key parameters that influence deformation, as identified in the foam models to determine the range of deformations that may occur clinically using the anatomic models and if these deformations are clinically significant.

It’s worth noting that researchers sometimes use research questions instead of research objectives, or in other cases both. From a high-level perspective, research questions and research objectives make the same statements, but just in different formats.

Taking the first three research objectives as an example, they can be restructured into research questions as follows:

Restructuring Research Objectives as Research Questions

- Can finite element models using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum together with explicit dynamics be used to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion?

- What is the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup?

- What is the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types?

Difference Between Aims and Objectives

Hopefully the above explanations make clear the differences between aims and objectives, but to clarify:

- The research aim focus on what the research project is intended to achieve; research objectives focus on how the aim will be achieved.

- Research aims are relatively broad; research objectives are specific.

- Research aims focus on a project’s long-term outcomes; research objectives focus on its immediate, short-term outcomes.

- A research aim can be written in a single sentence or short paragraph; research objectives should be written as a numbered list.

How to Write Aims and Objectives

Before we discuss how to write a clear set of research aims and objectives, we should make it clear that there is no single way they must be written. Each researcher will approach their aims and objectives slightly differently, and often your supervisor will influence the formulation of yours on the basis of their own preferences.

Regardless, there are some basic principles that you should observe for good practice; these principles are described below.

Your aim should be made up of three parts that answer the below questions:

- Why is this research required?

- What is this research about?

- How are you going to do it?

The easiest way to achieve this would be to address each question in its own sentence, although it does not matter whether you combine them or write multiple sentences for each, the key is to address each one.

The first question, why , provides context to your research project, the second question, what , describes the aim of your research, and the last question, how , acts as an introduction to your objectives which will immediately follow.

Scroll through the image set below to see the ‘why, what and how’ associated with our research aim example.

Note: Your research aims need not be limited to one. Some individuals per to define one broad ‘overarching aim’ of a project and then adopt two or three specific research aims for their thesis or dissertation. Remember, however, that in order for your assessors to consider your research project complete, you will need to prove you have fulfilled all of the aims you set out to achieve. Therefore, while having more than one research aim is not necessarily disadvantageous, consider whether a single overarching one will do.

Research Objectives

Each of your research objectives should be SMART :

- Specific – is there any ambiguity in the action you are going to undertake, or is it focused and well-defined?

- Measurable – how will you measure progress and determine when you have achieved the action?

- Achievable – do you have the support, resources and facilities required to carry out the action?

- Relevant – is the action essential to the achievement of your research aim?

- Timebound – can you realistically complete the action in the available time alongside your other research tasks?

In addition to being SMART, your research objectives should start with a verb that helps communicate your intent. Common research verbs include:

Table of Research Verbs to Use in Aims and Objectives

Last, format your objectives into a numbered list. This is because when you write your thesis or dissertation, you will at times need to make reference to a specific research objective; structuring your research objectives in a numbered list will provide a clear way of doing this.

To bring all this together, let’s compare the first research objective in the previous example with the above guidance:

Checking Research Objective Example Against Recommended Approach

Research Objective:

1. Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

Checking Against Recommended Approach:

Q: Is it specific? A: Yes, it is clear what the student intends to do (produce a finite element model), why they intend to do it (mimic cup/shell blows) and their parameters have been well-defined ( using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum ).

Q: Is it measurable? A: Yes, it is clear that the research objective will be achieved once the finite element model is complete.

Q: Is it achievable? A: Yes, provided the student has access to a computer lab, modelling software and laboratory data.

Q: Is it relevant? A: Yes, mimicking impacts to a cup/shell is fundamental to the overall aim of understanding how they deform when impacted upon.

Q: Is it timebound? A: Yes, it is possible to create a limited-scope finite element model in a relatively short time, especially if you already have experience in modelling.

Q: Does it start with a verb? A: Yes, it starts with ‘develop’, which makes the intent of the objective immediately clear.

Q: Is it a numbered list? A: Yes, it is the first research objective in a list of eight.

Mistakes in Writing Research Aims and Objectives

1. making your research aim too broad.

Having a research aim too broad becomes very difficult to achieve. Normally, this occurs when a student develops their research aim before they have a good understanding of what they want to research. Remember that at the end of your project and during your viva defence , you will have to prove that you have achieved your research aims; if they are too broad, this will be an almost impossible task. In the early stages of your research project, your priority should be to narrow your study to a specific area. A good way to do this is to take the time to study existing literature, question their current approaches, findings and limitations, and consider whether there are any recurring gaps that could be investigated .

Note: Achieving a set of aims does not necessarily mean proving or disproving a theory or hypothesis, even if your research aim was to, but having done enough work to provide a useful and original insight into the principles that underlie your research aim.

2. Making Your Research Objectives Too Ambitious

Be realistic about what you can achieve in the time you have available. It is natural to want to set ambitious research objectives that require sophisticated data collection and analysis, but only completing this with six months before the end of your PhD registration period is not a worthwhile trade-off.

3. Formulating Repetitive Research Objectives

Each research objective should have its own purpose and distinct measurable outcome. To this effect, a common mistake is to form research objectives which have large amounts of overlap. This makes it difficult to determine when an objective is truly complete, and also presents challenges in estimating the duration of objectives when creating your project timeline. It also makes it difficult to structure your thesis into unique chapters, making it more challenging for you to write and for your audience to read.

Fortunately, this oversight can be easily avoided by using SMART objectives.

Hopefully, you now have a good idea of how to create an effective set of aims and objectives for your research project, whether it be a thesis, dissertation or research paper. While it may be tempting to dive directly into your research, spending time on getting your aims and objectives right will give your research clear direction. This won’t only reduce the likelihood of problems arising later down the line, but will also lead to a more thorough and coherent research project.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Crafting Clear Pathways: Writing Objectives in Research Papers

Struggling to write research objectives? Follow our easy steps to learn how to craft effective and compelling objectives in research papers.

Are you struggling to define the goals and direction of your research? Are you losing yourself while doing research and tend to go astray from the intended research topic? Fear not, as many face the same problem and it is quite understandable to overcome this, a concept called research objective comes into play here.

In this article, we’ll delve into the world of the objectives in research papers and why they are essential for a successful study. We will be studying what they are and how they are used in research.

What is a Research Objective?

A research objective is a clear and specific goal that a researcher aims to achieve through a research study. It serves as a roadmap for the research, providing direction and focus. Research objectives are formulated based on the research questions or hypotheses, and they help in defining the scope of the study and guiding the research design and methodology. They also assist in evaluating the success and outcomes of the research.

Types of Research Objectives

There are typically three main types of objectives in a research paper:

- Exploratory Objectives: These objectives are focused on gaining a deeper understanding of a particular phenomenon, topic, or issue. Exploratory research objectives aim to explore and identify new ideas, insights, or patterns that were previously unknown or poorly understood. This type of objective is commonly used in preliminary or qualitative studies.

- Descriptive Objectives: Descriptive objectives seek to describe and document the characteristics, behaviors, or attributes of a specific population, event, or phenomenon. The purpose is to provide a comprehensive and accurate account of the subject of study. Descriptive research objectives often involve collecting and analyzing data through surveys, observations, or archival research.

- Explanatory or Causal Objectives: Explanatory objectives aim to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between variables or factors. These objectives focus on understanding why certain events or phenomena occur and how they are related to each other.

Also Read: What are the types of research?

Steps for Writing Objectives in Research Paper

1. identify the research topic:.

Clearly define the subject or topic of your research. This will provide a broad context for developing specific research objectives.

2. Conduct a Literature Review

Review existing literature and research related to your topic. This will help you understand the current state of knowledge, identify any research gaps, and refine your research objectives accordingly.

3. Identify the Research Questions or Hypotheses

Formulate specific research questions or hypotheses that you want to address in your study. These questions should be directly related to your research topic and guide the development of your research objectives.

4. Focus on Specific Goals

Break down the broader research questions or hypothesis into specific goals or objectives. Each objective should focus on a particular aspect of your research topic and be achievable within the scope of your study.

5. Use Clear and Measurable Language

Write your research objectives using clear and precise language. Avoid vague terms and use specific and measurable terms that can be observed, analyzed, or measured.

6. Consider Feasibility

Ensure that your research objectives are feasible within the available resources, time constraints, and ethical considerations. They should be realistic and attainable given the limitations of your study.

7. Prioritize Objectives

If you have multiple research objectives, prioritize them based on their importance and relevance to your overall research goals. This will help you allocate resources and focus your efforts accordingly.

8. Review and Refine

Review your research objectives to ensure they align with your research questions or hypotheses, and revise them if necessary. Seek feedback from peers or advisors to ensure clarity and coherence.

Tips for Writing Objectives in Research Paper

1. be clear and specific.

Clearly state what you intend to achieve with your research. Use specific language that leaves no room for ambiguity or confusion. This ensures that your objectives are well-defined and focused.

2. Use Action Verbs

Begin each research objective with an action verb that describes a measurable action or outcome. This helps make your objectives more actionable and measurable.

3. Align with Research Questions or Hypotheses

Your research objectives should directly address the research questions or hypotheses you have formulated. Ensure there is a clear connection between them to maintain coherence in your study.

4. Be Realistic and Feasible

Set research objectives that are attainable within the constraints of your study, including available resources, time, and ethical considerations. Unrealistic objectives may undermine the validity and reliability of your research.

5. Consider Relevance and Significance

Your research objectives should be relevant to your research topic and contribute to the broader field of study. Consider the potential impact and significance of achieving the objectives.

SMART Goals for Writing Research Objectives

To ensure that your research objectives are well-defined and effectively guide your study, you can apply the SMART framework. SMART stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. Here’s how you can make your research objectives SMART:

- Specific : Clearly state what you want to achieve in a precise and specific manner. Avoid vague or generalized language. Specify the population, variables, or phenomena of interest.

- Measurable : Ensure that your research objectives can be quantified or observed in a measurable way. This allows for objective evaluation and assessment of progress.

- Achievable : Set research objectives that are realistic and attainable within the available resources, time, and scope of your study. Consider the feasibility of conducting the research and collecting the necessary data.

- Relevant : Ensure that your research objectives are directly relevant to your research topic and contribute to the broader knowledge or understanding of the field. They should align with the purpose and significance of your study.

- Time-bound : Set a specific timeframe or deadline for achieving your research objectives. This helps create a sense of urgency and provides a clear timeline for your study.

Examples of Research Objectives

Here are some examples of research objectives from various fields of study:

- To examine the relationship between social media usage and self-esteem among young adults aged 18-25 in order to understand the potential impact on mental well-being.

- To assess the effectiveness of a mindfulness-based intervention in reducing stress levels and improving coping mechanisms among individuals diagnosed with anxiety disorders.

- To investigate the factors influencing consumer purchasing decisions in the e-commerce industry, with a focus on the role of online reviews and social media influencers.

- To analyze the effects of climate change on the biodiversity of coral reefs in a specific region, using remote sensing techniques and field surveys.