- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Summary – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Summary – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Summary

Definition:

A research summary is a brief and concise overview of a research project or study that highlights its key findings, main points, and conclusions. It typically includes a description of the research problem, the research methods used, the results obtained, and the implications or significance of the findings. It is often used as a tool to quickly communicate the main findings of a study to other researchers, stakeholders, or decision-makers.

Structure of Research Summary

The Structure of a Research Summary typically include:

- Introduction : This section provides a brief background of the research problem or question, explains the purpose of the study, and outlines the research objectives.

- Methodology : This section explains the research design, methods, and procedures used to conduct the study. It describes the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- Results : This section presents the main findings of the study, including statistical analysis if applicable. It may include tables, charts, or graphs to visually represent the data.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results and explains their implications. It discusses the significance of the findings, compares them to previous research, and identifies any limitations or future directions for research.

- Conclusion : This section summarizes the main points of the research and provides a conclusion based on the findings. It may also suggest implications for future research or practical applications of the results.

- References : This section lists the sources cited in the research summary, following the appropriate citation style.

How to Write Research Summary

Here are the steps you can follow to write a research summary:

- Read the research article or study thoroughly: To write a summary, you must understand the research article or study you are summarizing. Therefore, read the article or study carefully to understand its purpose, research design, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Identify the main points : Once you have read the research article or study, identify the main points, key findings, and research question. You can highlight or take notes of the essential points and findings to use as a reference when writing your summary.

- Write the introduction: Start your summary by introducing the research problem, research question, and purpose of the study. Briefly explain why the research is important and its significance.

- Summarize the methodology : In this section, summarize the research design, methods, and procedures used to conduct the study. Explain the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- Present the results: Summarize the main findings of the study. Use tables, charts, or graphs to visually represent the data if necessary.

- Interpret the results: In this section, interpret the results and explain their implications. Discuss the significance of the findings, compare them to previous research, and identify any limitations or future directions for research.

- Conclude the summary : Summarize the main points of the research and provide a conclusion based on the findings. Suggest implications for future research or practical applications of the results.

- Revise and edit : Once you have written the summary, revise and edit it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free of errors. Make sure that your summary accurately represents the research article or study.

- Add references: Include a list of references cited in the research summary, following the appropriate citation style.

Example of Research Summary

Here is an example of a research summary:

Title: The Effects of Yoga on Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis

Introduction: This meta-analysis examines the effects of yoga on mental health. The study aimed to investigate whether yoga practice can improve mental health outcomes such as anxiety, depression, stress, and quality of life.

Methodology : The study analyzed data from 14 randomized controlled trials that investigated the effects of yoga on mental health outcomes. The sample included a total of 862 participants. The yoga interventions varied in length and frequency, ranging from four to twelve weeks, with sessions lasting from 45 to 90 minutes.

Results : The meta-analysis found that yoga practice significantly improved mental health outcomes. Participants who practiced yoga showed a significant reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as stress levels. Quality of life also improved in those who practiced yoga.

Discussion : The findings of this study suggest that yoga can be an effective intervention for improving mental health outcomes. The study supports the growing body of evidence that suggests that yoga can have a positive impact on mental health. Limitations of the study include the variability of the yoga interventions, which may affect the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion : Overall, the findings of this meta-analysis support the use of yoga as an effective intervention for improving mental health outcomes. Further research is needed to determine the optimal length and frequency of yoga interventions for different populations.

References :

- Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Langhorst, J., Dobos, G., & Berger, B. (2013). Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and anxiety, 30(11), 1068-1083.

- Khalsa, S. B. (2004). Yoga as a therapeutic intervention: a bibliometric analysis of published research studies. Indian journal of physiology and pharmacology, 48(3), 269-285.

- Ross, A., & Thomas, S. (2010). The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(1), 3-12.

Purpose of Research Summary

The purpose of a research summary is to provide a brief overview of a research project or study, including its main points, findings, and conclusions. The summary allows readers to quickly understand the essential aspects of the research without having to read the entire article or study.

Research summaries serve several purposes, including:

- Facilitating comprehension: A research summary allows readers to quickly understand the main points and findings of a research project or study without having to read the entire article or study. This makes it easier for readers to comprehend the research and its significance.

- Communicating research findings: Research summaries are often used to communicate research findings to a wider audience, such as policymakers, practitioners, or the general public. The summary presents the essential aspects of the research in a clear and concise manner, making it easier for non-experts to understand.

- Supporting decision-making: Research summaries can be used to support decision-making processes by providing a summary of the research evidence on a particular topic. This information can be used by policymakers or practitioners to make informed decisions about interventions, programs, or policies.

- Saving time: Research summaries save time for researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and other stakeholders who need to review multiple research studies. Rather than having to read the entire article or study, they can quickly review the summary to determine whether the research is relevant to their needs.

Characteristics of Research Summary

The following are some of the key characteristics of a research summary:

- Concise : A research summary should be brief and to the point, providing a clear and concise overview of the main points of the research.

- Objective : A research summary should be written in an objective tone, presenting the research findings without bias or personal opinion.

- Comprehensive : A research summary should cover all the essential aspects of the research, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Accurate : A research summary should accurately reflect the key findings and conclusions of the research.

- Clear and well-organized: A research summary should be easy to read and understand, with a clear structure and logical flow.

- Relevant : A research summary should focus on the most important and relevant aspects of the research, highlighting the key findings and their implications.

- Audience-specific: A research summary should be tailored to the intended audience, using language and terminology that is appropriate and accessible to the reader.

- Citations : A research summary should include citations to the original research articles or studies, allowing readers to access the full text of the research if desired.

When to write Research Summary

Here are some situations when it may be appropriate to write a research summary:

- Proposal stage: A research summary can be included in a research proposal to provide a brief overview of the research aims, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

- Conference presentation: A research summary can be prepared for a conference presentation to summarize the main findings of a study or research project.

- Journal submission: Many academic journals require authors to submit a research summary along with their research article or study. The summary provides a brief overview of the study’s main points, findings, and conclusions and helps readers quickly understand the research.

- Funding application: A research summary can be included in a funding application to provide a brief summary of the research aims, objectives, and expected outcomes.

- Policy brief: A research summary can be prepared as a policy brief to communicate research findings to policymakers or stakeholders in a concise and accessible manner.

Advantages of Research Summary

Research summaries offer several advantages, including:

- Time-saving: A research summary saves time for readers who need to understand the key findings and conclusions of a research project quickly. Rather than reading the entire research article or study, readers can quickly review the summary to determine whether the research is relevant to their needs.

- Clarity and accessibility: A research summary provides a clear and accessible overview of the research project’s main points, making it easier for readers to understand the research without having to be experts in the field.

- Improved comprehension: A research summary helps readers comprehend the research by providing a brief and focused overview of the key findings and conclusions, making it easier to understand the research and its significance.

- Enhanced communication: Research summaries can be used to communicate research findings to a wider audience, such as policymakers, practitioners, or the general public, in a concise and accessible manner.

- Facilitated decision-making: Research summaries can support decision-making processes by providing a summary of the research evidence on a particular topic. Policymakers or practitioners can use this information to make informed decisions about interventions, programs, or policies.

- Increased dissemination: Research summaries can be easily shared and disseminated, allowing research findings to reach a wider audience.

Limitations of Research Summary

Limitations of the Research Summary are as follows:

- Limited scope: Research summaries provide a brief overview of the research project’s main points, findings, and conclusions, which can be limiting. They may not include all the details, nuances, and complexities of the research that readers may need to fully understand the study’s implications.

- Risk of oversimplification: Research summaries can be oversimplified, reducing the complexity of the research and potentially distorting the findings or conclusions.

- Lack of context: Research summaries may not provide sufficient context to fully understand the research findings, such as the research background, methodology, or limitations. This may lead to misunderstandings or misinterpretations of the research.

- Possible bias: Research summaries may be biased if they selectively emphasize certain findings or conclusions over others, potentially distorting the overall picture of the research.

- Format limitations: Research summaries may be constrained by the format or length requirements, making it challenging to fully convey the research’s main points, findings, and conclusions.

- Accessibility: Research summaries may not be accessible to all readers, particularly those with limited literacy skills, visual impairments, or language barriers.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Research Summary

It’s a common perception that writing a research summary is a quick and easy task. After all, how hard can jotting down 300 words be? But when you consider the weight those 300 words carry, writing a research summary as a part of your dissertation, essay or compelling draft for your paper instantly becomes daunting task.

A research summary requires you to synthesize a complex research paper into an informative, self-explanatory snapshot. It needs to portray what your article contains. Thus, writing it often comes at the end of the task list.

Regardless of when you’re planning to write, it is no less of a challenge, particularly if you’re doing it for the first time. This blog will take you through everything you need to know about research summary so that you have an easier time with it.

What is a Research Summary?

A research summary is the part of your research paper that describes its findings to the audience in a brief yet concise manner. A well-curated research summary represents you and your knowledge about the information written in the research paper.

While writing a quality research summary, you need to discover and identify the significant points in the research and condense it in a more straightforward form. A research summary is like a doorway that provides access to the structure of a research paper's sections.

Since the purpose of a summary is to give an overview of the topic, methodology, and conclusions employed in a paper, it requires an objective approach. No analysis or criticism.

Research summary or Abstract. What’s the Difference?

They’re both brief, concise, and give an overview of an aspect of the research paper. So, it’s easy to understand why many new researchers get the two confused. However, a research summary and abstract are two very different things with individual purpose. To start with, a research summary is written at the end while the abstract comes at the beginning of a research paper.

A research summary captures the essence of the paper at the end of your document. It focuses on your topic, methods, and findings. More like a TL;DR, if you will. An abstract, on the other hand, is a description of what your research paper is about. It tells your reader what your topic or hypothesis is, and sets a context around why you have embarked on your research.

Getting Started with a Research Summary

Before you start writing, you need to get insights into your research’s content, style, and organization. There are three fundamental areas of a research summary that you should focus on.

- While deciding the contents of your research summary, you must include a section on its importance as a whole, the techniques, and the tools that were used to formulate the conclusion. Additionally, there needs to be a short but thorough explanation of how the findings of the research paper have a significance.

- To keep the summary well-organized, try to cover the various sections of the research paper in separate paragraphs. Besides, how the idea of particular factual research came up first must be explained in a separate paragraph.

- As a general practice worldwide, research summaries are restricted to 300-400 words. However, if you have chosen a lengthy research paper, try not to exceed the word limit of 10% of the entire research paper.

How to Structure Your Research Summary

The research summary is nothing but a concise form of the entire research paper. Therefore, the structure of a summary stays the same as the paper. So, include all the section titles and write a little about them. The structural elements that a research summary must consist of are:

It represents the topic of the research. Try to phrase it so that it includes the key findings or conclusion of the task.

The abstract gives a context of the research paper. Unlike the abstract at the beginning of a paper, the abstract here, should be very short since you’ll be working with a limited word count.

Introduction

This is the most crucial section of a research summary as it helps readers get familiarized with the topic. You should include the definition of your topic, the current state of the investigation, and practical relevance in this part. Additionally, you should present the problem statement, investigative measures, and any hypothesis in this section.

Methodology

This section provides details about the methodology and the methods adopted to conduct the study. You should write a brief description of the surveys, sampling, type of experiments, statistical analysis, and the rationality behind choosing those particular methods.

Create a list of evidence obtained from the various experiments with a primary analysis, conclusions, and interpretations made upon that. In the paper research paper, you will find the results section as the most detailed and lengthy part. Therefore, you must pick up the key elements and wisely decide which elements are worth including and which are worth skipping.

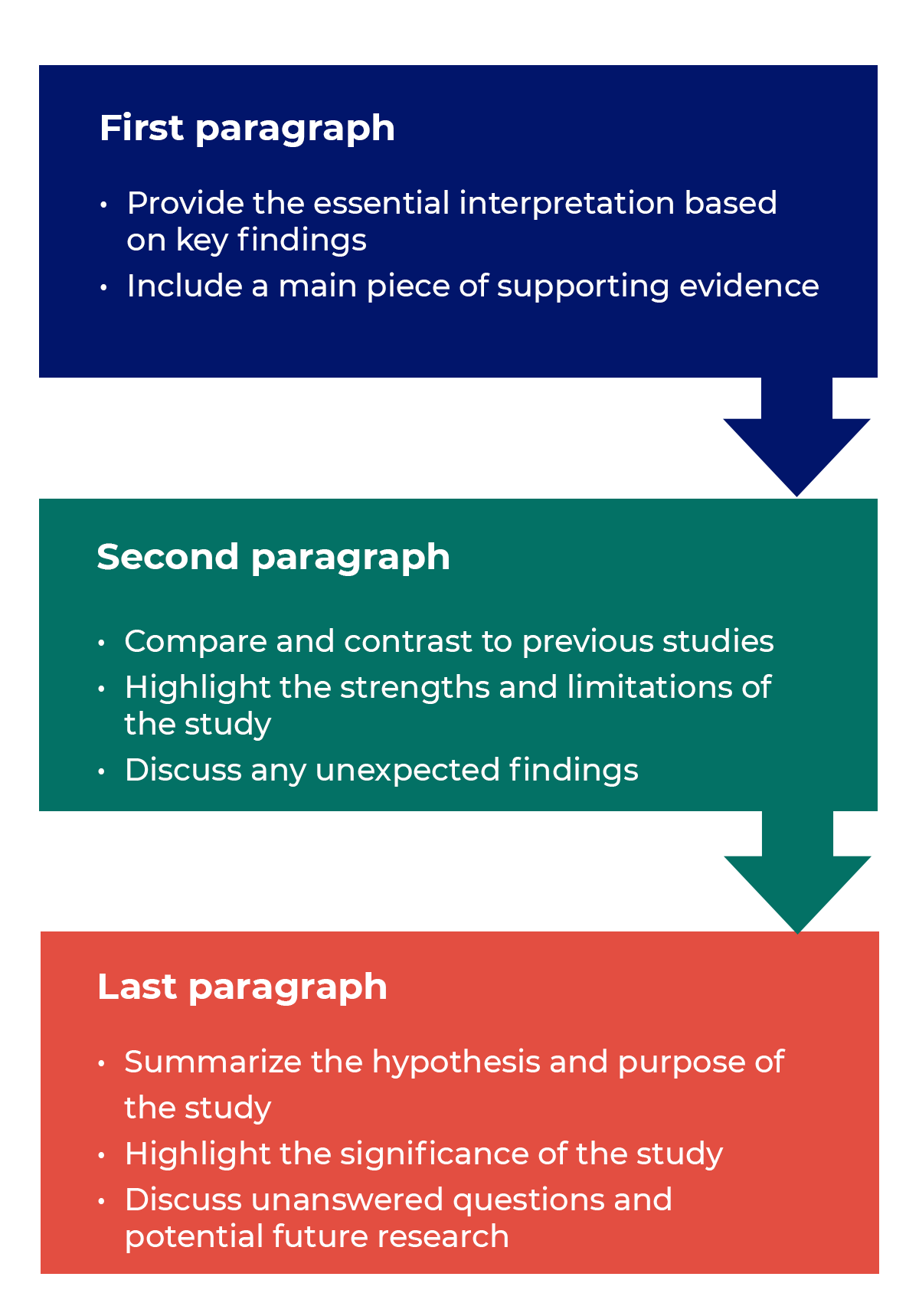

This is where you present the interpretation of results in the context of their application. Discussion usually covers results, inferences, and theoretical models explaining the obtained values, key strengths, and limitations. All of these are vital elements that you must include in the summary.

Most research papers merge conclusion with discussions. However, depending upon the instructions, you may have to prepare this as a separate section in your research summary. Usually, conclusion revisits the hypothesis and provides the details about the validation or denial about the arguments made in the research paper, based upon how convincing the results were obtained.

The structure of a research summary closely resembles the anatomy of a scholarly article . Additionally, you should keep your research and references limited to authentic and scholarly sources only.

Tips for Writing a Research Summary

The core concept behind undertaking a research summary is to present a simple and clear understanding of your research paper to the reader. The biggest hurdle while doing that is the number of words you have at your disposal. So, follow the steps below to write a research summary that sticks.

1. Read the parent paper thoroughly

You should go through the research paper thoroughly multiple times to ensure that you have a complete understanding of its contents. A 3-stage reading process helps.

a. Scan: In the first read, go through it to get an understanding of its basic concept and methodologies.

b. Read: For the second step, read the article attentively by going through each section, highlighting the key elements, and subsequently listing the topics that you will include in your research summary.

c. Skim: Flip through the article a few more times to study the interpretation of various experimental results, statistical analysis, and application in different contexts.

Sincerely go through different headings and subheadings as it will allow you to understand the underlying concept of each section. You can try reading the introduction and conclusion simultaneously to understand the motive of the task and how obtained results stay fit to the expected outcome.

2. Identify the key elements in different sections

While exploring different sections of an article, you can try finding answers to simple what, why, and how. Below are a few pointers to give you an idea:

- What is the research question and how is it addressed?

- Is there a hypothesis in the introductory part?

- What type of methods are being adopted?

- What is the sample size for data collection and how is it being analyzed?

- What are the most vital findings?

- Do the results support the hypothesis?

Discussion/Conclusion

- What is the final solution to the problem statement?

- What is the explanation for the obtained results?

- What is the drawn inference?

- What are the various limitations of the study?

3. Prepare the first draft

Now that you’ve listed the key points that the paper tries to demonstrate, you can start writing the summary following the standard structure of a research summary. Just make sure you’re not writing statements from the parent research paper verbatim.

Instead, try writing down each section in your own words. This will not only help in avoiding plagiarism but will also show your complete understanding of the subject. Alternatively, you can use a summarizing tool (AI-based summary generators) to shorten the content or summarize the content without disrupting the actual meaning of the article.

SciSpace Copilot is one such helpful feature! You can easily upload your research paper and ask Copilot to summarize it. You will get an AI-generated, condensed research summary. SciSpace Copilot also enables you to highlight text, clip math and tables, and ask any question relevant to the research paper; it will give you instant answers with deeper context of the article..

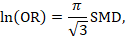

4. Include visuals

One of the best ways to summarize and consolidate a research paper is to provide visuals like graphs, charts, pie diagrams, etc.. Visuals make getting across the facts, the past trends, and the probabilistic figures around a concept much more engaging.

5. Double check for plagiarism

It can be very tempting to copy-paste a few statements or the entire paragraphs depending upon the clarity of those sections. But it’s best to stay away from the practice. Even paraphrasing should be done with utmost care and attention.

Also: QuillBot vs SciSpace: Choose the best AI-paraphrasing tool

6. Religiously follow the word count limit

You need to have strict control while writing different sections of a research summary. In many cases, it has been observed that the research summary and the parent research paper become the same length. If that happens, it can lead to discrediting of your efforts and research summary itself. Whatever the standard word limit has been imposed, you must observe that carefully.

7. Proofread your research summary multiple times

The process of writing the research summary can be exhausting and tiring. However, you shouldn’t allow this to become a reason to skip checking your academic writing several times for mistakes like misspellings, grammar, wordiness, and formatting issues. Proofread and edit until you think your research summary can stand out from the others, provided it is drafted perfectly on both technicality and comprehension parameters. You can also seek assistance from editing and proofreading services , and other free tools that help you keep these annoying grammatical errors at bay.

8. Watch while you write

Keep a keen observation of your writing style. You should use the words very precisely, and in any situation, it should not represent your personal opinions on the topic. You should write the entire research summary in utmost impersonal, precise, factually correct, and evidence-based writing.

9. Ask a friend/colleague to help

Once you are done with the final copy of your research summary, you must ask a friend or colleague to read it. You must test whether your friend or colleague could grasp everything without referring to the parent paper. This will help you in ensuring the clarity of the article.

Once you become familiar with the research paper summary concept and understand how to apply the tips discussed above in your current task, summarizing a research summary won’t be that challenging. While traversing the different stages of your academic career, you will face different scenarios where you may have to create several research summaries.

In such cases, you just need to look for answers to simple questions like “Why this study is necessary,” “what were the methods,” “who were the participants,” “what conclusions were drawn from the research,” and “how it is relevant to the wider world.” Once you find out the answers to these questions, you can easily create a good research summary following the standard structure and a precise writing style.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

- Research Summary: What Is It & How To Write One

Introduction

A research summary is a requirement during academic research and sometimes you might need to prepare a research summary during a research project for an organization.

Most people find a research summary a daunting task as you are required to condense complex research material into an informative, easy-to-understand article most times with a minimum of 300-500 words.

In this post, we will guide you through all the steps required to make writing your research summary an easier task.

What is a Research Summary?

A research summary is a piece of writing that summarizes the research of a specific topic into bite-size easy-to-read and comprehend articles. The primary goal is to give the reader a detailed outline of the key findings of a research.

It is an unavoidable requirement in colleges and universities. To write a good research summary, you must understand the goal of your research, as this would help make the process easier.

A research summary preserves the structure and sections of the article it is derived from.

Research Summary or Abstract: What’s The Difference?

The Research Summary and Abstract are similar, especially as they are both brief, straight to the point, and provide an overview of the entire research paper. However, there are very clear differences.

To begin with, a Research summary is written at the end of a research activity, while the Abstract is written at the beginning of a research paper.

A Research Summary captures the main points of a study, with an emphasis on the topic, method , and discoveries, an Abstract is a description of what your research paper would talk about and the reason for your research or the hypothesis you are trying to validate.

Let us take a deeper look at the difference between both terms.

What is an Abstract?

An abstract is a short version of a research paper. It is written to convey the findings of the research to the reader. It provides the reader with information that would help them understand the research, by giving them a clear idea about the subject matter of a research paper. It is usually submitted before the presentation of a research paper.

What is a Summary?

A summary is a short form of an essay, a research paper, or a chapter in a book. A research summary is a narration of a research study, condensing the focal points of research to a shorter form, usually aligned with the same structure of the research study, from which the summary is derived.

What Is The Difference Between an Abstract and a Summary?

An abstract communicates the main points of a research paper, it includes the questions, major findings, the importance of the findings, etc.

An abstract reflects the perceptions of the author about a topic, while a research summary reflects the ideology of the research study that is being summarized.

Getting Started with a Research Summary

Before commencing a research summary, there is a need to understand the style and organization of the content you plan to summarize. There are three fundamental areas of the research that should be the focal point:

- When deciding on the content include a section that speaks to the importance of the research, and the techniques and tools used to arrive at your conclusion.

- Keep the summary well organized, and use paragraphs to discuss the various sections of the research.

- Restrict your research to 300-400 words which is the standard practice for research summaries globally. However, if the research paper you want to summarize is a lengthy one, do not exceed 10% of the entire research material.

Once you have satisfied the requirements of the fundamentals for starting your research summary, you can now begin to write using the following format:

- Why was this research done? – A clear description of the reason the research was embarked on and the hypothesis being tested.

- Who was surveyed? – Your research study should have details of the source of your information. If it was via a survey, you should document who the participants of the survey were and the reason that they were selected.

- What was the methodology? – Discuss the methodology, in terms of what kind of survey method did you adopt. Was it a face-to-face interview, a phone interview, or a focus group setting?

- What were the key findings? – This is perhaps the most vital part of the process. What discoveries did you make after the testing? This part should be based on raw facts free from any personal bias.

- Conclusion – What conclusions did you draw from the findings?

- Takeaways and action points – This is where your views and perception can be reflected. Here, you can now share your recommendations or action points.

- Identify the focal point of the article – In other to get a grasp of the content covered in the research paper, you can skim the article first, in a bid to understand the most essential part of the research paper.

- Analyze and understand the topic and article – Writing a summary of a research paper involves being familiar with the topic – the current state of knowledge, key definitions, concepts, and models. This is often gleaned while reading the literature review. Please note that only a deep understanding ensures efficient and accurate summarization of the content.

- Make notes as you read – Highlight and summarize each paragraph as you read. Your notes are what you would further condense to create a draft that would form your research summary.

How to Structure Your Research Summary

- Title – This highlights the area of analysis, and can be formulated to briefly highlight key findings.

- Abstract – this is a very brief and comprehensive description of the study, required in every academic article, with a length of 100-500 words at most.

- Introduction – this is a vital part of any research summary, it provides the context and the literature review that gently introduces readers to the subject matter. The introduction usually covers definitions, questions, and hypotheses of the research study.

- Methodology –This section emphasizes the process and or data analysis methods used, in terms of experiments, surveys, sampling, or statistical analysis.

- Results section – this section lists in detail the results derived from the research with evidence obtained from all the experiments conducted.

- Discussion – these parts discuss the results within the context of current knowledge among subject matter experts. Interpretation of results and theoretical models explaining the observed results, the strengths of the study, and the limitations experienced are going to be a part of the discussion.

- Conclusion – In a conclusion, hypotheses are discussed and revalidated or denied, based on how convincing the evidence is.

- References – this section is for giving credit to those who work you studied to create your summary. You do this by providing appropriate citations as you write.

Research Summary Example 1

Below are some defining elements of a sample research summary.

Title – “The probability of an unexpected volcanic eruption in Greenwich”

Introduction – this section would list the catastrophic consequences that occurred in the country and the importance of analyzing this event.

Hypothesis – An eruption of the Greenwich supervolcano would be preceded by intense preliminary activity manifesting in advance, before the eruption.

Results – these could contain a report of statistical data from various volcanic eruptions happening globally while looking critically at the activity that occurred before these events.

Discussion and conclusion – Given that Greenwich is now consistently monitored by scientists and that signs of an eruption are usually detected before the volcanic eruption, this confirms the hypothesis. Hence creating an emergency plan outlining other intervention measures and ultimately evacuation is essential.

Research Summary Example 2

Below is another sample sketch.

Title – “The frequency of extreme weather events in the UK in 2000-2008 as compared to the ‘60s”

Introduction – Weather events bring intense material damage and cause pain to the victims affected.

Hypothesis – Extreme weather events are more frequent in recent times compared to the ‘50s

Results – The frequency of several categories of extreme events now and then are listed here, such as droughts, fires, massive rainfall/snowfalls, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, etc.

Discussion and conclusion – Several types of extreme events have become more commonplace in recent times, confirming the hypothesis. This rise in extreme weather events can be traced to rising CO2 levels and increasing temperatures and global warming explain the rising frequency of these disasters. Addressing the rising CO2 levels and paying attention to climate change is the only to combat this phenomenon.

A research summary is the short form of a research paper, analyzing the important aspect of the study. Everyone who reads a research summary has a full grasp of the main idea being discussed in the original research paper. Conducting any research means you will write a summary, which is an important part of your project and would be the most read part of your project.

Having a guideline before you start helps, this would form your checklist which would guide your actions as you write your research summary. It is important to note that a Research Summary is different from an Abstract paper written at the beginning of a research paper, describing the idea behind a research paper.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- abstract in research papers

- abstract writing

- action research

- research summary

- research summary vs abstract

- research surveys

- Angela Kayode-Sanni

You may also like:

Action Research: What it is, Stages & Examples

Introduction Action research is an evidence-based approach that has been used for years in the field of education and social sciences....

The McNamara Fallacy: How Researchers Can Detect and to Avoid it.

Introduction The McNamara Fallacy is a common problem in research. It happens when researchers take a single piece of data as evidence...

Research Questions: Definitions, Types + [Examples]

A comprehensive guide on the definition of research questions, types, importance, good and bad research question examples

How to Write An Abstract For Research Papers: Tips & Examples

In this article, we will share some tips for writing an effective abstract, plus samples you can learn from.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Chapter 15: interpreting results and drawing conclusions.

Holger J Schünemann, Gunn E Vist, Julian PT Higgins, Nancy Santesso, Jonathan J Deeks, Paul Glasziou, Elie A Akl, Gordon H Guyatt; on behalf of the Cochrane GRADEing Methods Group

Key Points:

- This chapter provides guidance on interpreting the results of synthesis in order to communicate the conclusions of the review effectively.

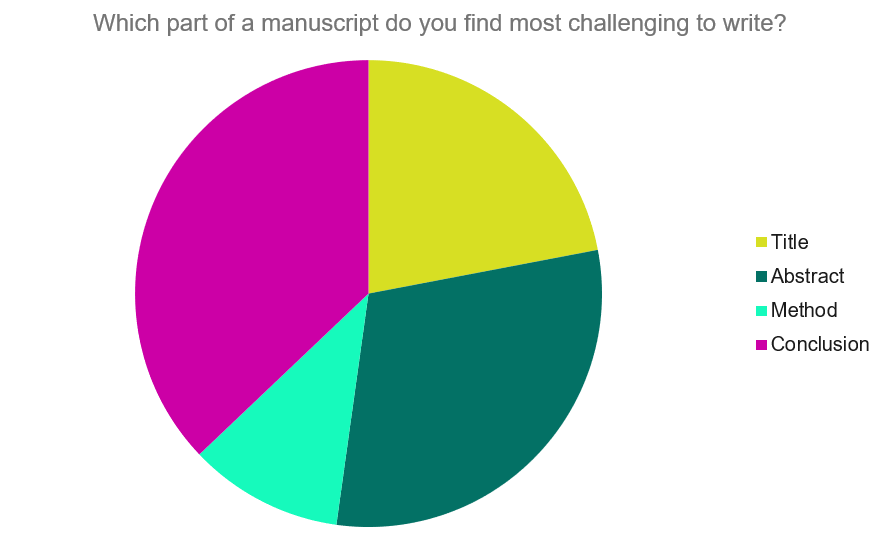

- Methods are presented for computing, presenting and interpreting relative and absolute effects for dichotomous outcome data, including the number needed to treat (NNT).

- For continuous outcome measures, review authors can present summary results for studies using natural units of measurement or as minimal important differences when all studies use the same scale. When studies measure the same construct but with different scales, review authors will need to find a way to interpret the standardized mean difference, or to use an alternative effect measure for the meta-analysis such as the ratio of means.

- Review authors should not describe results as ‘statistically significant’, ‘not statistically significant’ or ‘non-significant’ or unduly rely on thresholds for P values, but report the confidence interval together with the exact P value.

- Review authors should not make recommendations about healthcare decisions, but they can – after describing the certainty of evidence and the balance of benefits and harms – highlight different actions that might be consistent with particular patterns of values and preferences and other factors that determine a decision such as cost.

Cite this chapter as: Schünemann HJ, Vist GE, Higgins JPT, Santesso N, Deeks JJ, Glasziou P, Akl EA, Guyatt GH. Chapter 15: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

15.1 Introduction

The purpose of Cochrane Reviews is to facilitate healthcare decisions by patients and the general public, clinicians, guideline developers, administrators and policy makers. They also inform future research. A clear statement of findings, a considered discussion and a clear presentation of the authors’ conclusions are, therefore, important parts of the review. In particular, the following issues can help people make better informed decisions and increase the usability of Cochrane Reviews:

- information on all important outcomes, including adverse outcomes;

- the certainty of the evidence for each of these outcomes, as it applies to specific populations and specific interventions; and

- clarification of the manner in which particular values and preferences may bear on the desirable and undesirable consequences of the intervention.

A ‘Summary of findings’ table, described in Chapter 14 , Section 14.1 , provides key pieces of information about health benefits and harms in a quick and accessible format. It is highly desirable that review authors include a ‘Summary of findings’ table in Cochrane Reviews alongside a sufficient description of the studies and meta-analyses to support its contents. This description includes the rating of the certainty of evidence, also called the quality of the evidence or confidence in the estimates of the effects, which is expected in all Cochrane Reviews.

‘Summary of findings’ tables are usually supported by full evidence profiles which include the detailed ratings of the evidence (Guyatt et al 2011a, Guyatt et al 2013a, Guyatt et al 2013b, Santesso et al 2016). The Discussion section of the text of the review provides space to reflect and consider the implications of these aspects of the review’s findings. Cochrane Reviews include five standard subheadings to ensure the Discussion section places the review in an appropriate context: ‘Summary of main results (benefits and harms)’; ‘Potential biases in the review process’; ‘Overall completeness and applicability of evidence’; ‘Certainty of the evidence’; and ‘Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews’. Following the Discussion, the Authors’ conclusions section is divided into two standard subsections: ‘Implications for practice’ and ‘Implications for research’. The assessment of the certainty of evidence facilitates a structured description of the implications for practice and research.

Because Cochrane Reviews have an international audience, the Discussion and Authors’ conclusions should, so far as possible, assume a broad international perspective and provide guidance for how the results could be applied in different settings, rather than being restricted to specific national or local circumstances. Cultural differences and economic differences may both play an important role in determining the best course of action based on the results of a Cochrane Review. Furthermore, individuals within societies have widely varying values and preferences regarding health states, and use of societal resources to achieve particular health states. For all these reasons, and because information that goes beyond that included in a Cochrane Review is required to make fully informed decisions, different people will often make different decisions based on the same evidence presented in a review.

Thus, review authors should avoid specific recommendations that inevitably depend on assumptions about available resources, values and preferences, and other factors such as equity considerations, feasibility and acceptability of an intervention. The purpose of the review should be to present information and aid interpretation rather than to offer recommendations. The discussion and conclusions should help people understand the implications of the evidence in relation to practical decisions and apply the results to their specific situation. Review authors can aid this understanding of the implications by laying out different scenarios that describe certain value structures.

In this chapter, we address first one of the key aspects of interpreting findings that is also fundamental in completing a ‘Summary of findings’ table: the certainty of evidence related to each of the outcomes. We then provide a more detailed consideration of issues around applicability and around interpretation of numerical results, and provide suggestions for presenting authors’ conclusions.

15.2 Issues of indirectness and applicability

15.2.1 the role of the review author.

“A leap of faith is always required when applying any study findings to the population at large” or to a specific person. “In making that jump, one must always strike a balance between making justifiable broad generalizations and being too conservative in one’s conclusions” (Friedman et al 1985). In addition to issues about risk of bias and other domains determining the certainty of evidence, this leap of faith is related to how well the identified body of evidence matches the posed PICO ( Population, Intervention, Comparator(s) and Outcome ) question. As to the population, no individual can be entirely matched to the population included in research studies. At the time of decision, there will always be differences between the study population and the person or population to whom the evidence is applied; sometimes these differences are slight, sometimes large.

The terms applicability, generalizability, external validity and transferability are related, sometimes used interchangeably and have in common that they lack a clear and consistent definition in the classic epidemiological literature (Schünemann et al 2013). However, all of the terms describe one overarching theme: whether or not available research evidence can be directly used to answer the health and healthcare question at hand, ideally supported by a judgement about the degree of confidence in this use (Schünemann et al 2013). GRADE’s certainty domains include a judgement about ‘indirectness’ to describe all of these aspects including the concept of direct versus indirect comparisons of different interventions (Atkins et al 2004, Guyatt et al 2008, Guyatt et al 2011b).

To address adequately the extent to which a review is relevant for the purpose to which it is being put, there are certain things the review author must do, and certain things the user of the review must do to assess the degree of indirectness. Cochrane and the GRADE Working Group suggest using a very structured framework to address indirectness. We discuss here and in Chapter 14 what the review author can do to help the user. Cochrane Review authors must be extremely clear on the population, intervention and outcomes that they intend to address. Chapter 14, Section 14.1.2 , also emphasizes a crucial step: the specification of all patient-important outcomes relevant to the intervention strategies under comparison.

In considering whether the effect of an intervention applies equally to all participants, and whether different variations on the intervention have similar effects, review authors need to make a priori hypotheses about possible effect modifiers, and then examine those hypotheses (see Chapter 10, Section 10.10 and Section 10.11 ). If they find apparent subgroup effects, they must ultimately decide whether or not these effects are credible (Sun et al 2012). Differences between subgroups, particularly those that correspond to differences between studies, should be interpreted cautiously. Some chance variation between subgroups is inevitable so, unless there is good reason to believe that there is an interaction, review authors should not assume that the subgroup effect exists. If, despite due caution, review authors judge subgroup effects in terms of relative effect estimates as credible (i.e. the effects differ credibly), they should conduct separate meta-analyses for the relevant subgroups, and produce separate ‘Summary of findings’ tables for those subgroups.

The user of the review will be challenged with ‘individualization’ of the findings, whether they seek to apply the findings to an individual patient or a policy decision in a specific context. For example, even if relative effects are similar across subgroups, absolute effects will differ according to baseline risk. Review authors can help provide this information by identifying identifiable groups of people with varying baseline risks in the ‘Summary of findings’ tables, as discussed in Chapter 14, Section 14.1.3 . Users can then identify their specific case or population as belonging to a particular risk group, if relevant, and assess their likely magnitude of benefit or harm accordingly. A description of the identifying prognostic or baseline risk factors in a brief scenario (e.g. age or gender) will help users of a review further.

Another decision users must make is whether their individual case or population of interest is so different from those included in the studies that they cannot use the results of the systematic review and meta-analysis at all. Rather than rigidly applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria of studies, it is better to ask whether or not there are compelling reasons why the evidence should not be applied to a particular patient. Review authors can sometimes help decision makers by identifying important variation where divergence might limit the applicability of results (Rothwell 2005, Schünemann et al 2006, Guyatt et al 2011b, Schünemann et al 2013), including biologic and cultural variation, and variation in adherence to an intervention.

In addressing these issues, review authors cannot be aware of, or address, the myriad of differences in circumstances around the world. They can, however, address differences of known importance to many people and, importantly, they should avoid assuming that other people’s circumstances are the same as their own in discussing the results and drawing conclusions.

15.2.2 Biological variation

Issues of biological variation that may affect the applicability of a result to a reader or population include divergence in pathophysiology (e.g. biological differences between women and men that may affect responsiveness to an intervention) and divergence in a causative agent (e.g. for infectious diseases such as malaria, which may be caused by several different parasites). The discussion of the results in the review should make clear whether the included studies addressed all or only some of these groups, and whether any important subgroup effects were found.

15.2.3 Variation in context

Some interventions, particularly non-pharmacological interventions, may work in some contexts but not in others; the situation has been described as program by context interaction (Hawe et al 2004). Contextual factors might pertain to the host organization in which an intervention is offered, such as the expertise, experience and morale of the staff expected to carry out the intervention, the competing priorities for the clinician’s or staff’s attention, the local resources such as service and facilities made available to the program and the status or importance given to the program by the host organization. Broader context issues might include aspects of the system within which the host organization operates, such as the fee or payment structure for healthcare providers and the local insurance system. Some interventions, in particular complex interventions (see Chapter 17 ), can be only partially implemented in some contexts, and this requires judgements about indirectness of the intervention and its components for readers in that context (Schünemann 2013).

Contextual factors may also pertain to the characteristics of the target group or population, such as cultural and linguistic diversity, socio-economic position, rural/urban setting. These factors may mean that a particular style of care or relationship evolves between service providers and consumers that may or may not match the values and technology of the program.

For many years these aspects have been acknowledged when decision makers have argued that results of evidence reviews from other countries do not apply in their own country or setting. Whilst some programmes/interventions have been successfully transferred from one context to another, others have not (Resnicow et al 1993, Lumley et al 2004, Coleman et al 2015). Review authors should be cautious when making generalizations from one context to another. They should report on the presence (or otherwise) of context-related information in intervention studies, where this information is available.

15.2.4 Variation in adherence

Variation in the adherence of the recipients and providers of care can limit the certainty in the applicability of results. Predictable differences in adherence can be due to divergence in how recipients of care perceive the intervention (e.g. the importance of side effects), economic conditions or attitudes that make some forms of care inaccessible in some settings, such as in low-income countries (Dans et al 2007). It should not be assumed that high levels of adherence in closely monitored randomized trials will translate into similar levels of adherence in normal practice.

15.2.5 Variation in values and preferences

Decisions about healthcare management strategies and options involve trading off health benefits and harms. The right choice may differ for people with different values and preferences (i.e. the importance people place on the outcomes and interventions), and it is important that decision makers ensure that decisions are consistent with a patient or population’s values and preferences. The importance placed on outcomes, together with other factors, will influence whether the recipients of care will or will not accept an option that is offered (Alonso-Coello et al 2016) and, thus, can be one factor influencing adherence. In Section 15.6 , we describe how the review author can help this process and the limits of supporting decision making based on intervention reviews.

15.3 Interpreting results of statistical analyses

15.3.1 confidence intervals.

Results for both individual studies and meta-analyses are reported with a point estimate together with an associated confidence interval. For example, ‘The odds ratio was 0.75 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.70 to 0.80’. The point estimate (0.75) is the best estimate of the magnitude and direction of the experimental intervention’s effect compared with the comparator intervention. The confidence interval describes the uncertainty inherent in any estimate, and describes a range of values within which we can be reasonably sure that the true effect actually lies. If the confidence interval is relatively narrow (e.g. 0.70 to 0.80), the effect size is known precisely. If the interval is wider (e.g. 0.60 to 0.93) the uncertainty is greater, although there may still be enough precision to make decisions about the utility of the intervention. Intervals that are very wide (e.g. 0.50 to 1.10) indicate that we have little knowledge about the effect and this imprecision affects our certainty in the evidence, and that further information would be needed before we could draw a more certain conclusion.

A 95% confidence interval is often interpreted as indicating a range within which we can be 95% certain that the true effect lies. This statement is a loose interpretation, but is useful as a rough guide. The strictly correct interpretation of a confidence interval is based on the hypothetical notion of considering the results that would be obtained if the study were repeated many times. If a study were repeated infinitely often, and on each occasion a 95% confidence interval calculated, then 95% of these intervals would contain the true effect (see Section 15.3.3 for further explanation).

The width of the confidence interval for an individual study depends to a large extent on the sample size. Larger studies tend to give more precise estimates of effects (and hence have narrower confidence intervals) than smaller studies. For continuous outcomes, precision depends also on the variability in the outcome measurements (i.e. how widely individual results vary between people in the study, measured as the standard deviation); for dichotomous outcomes it depends on the risk of the event (more frequent events allow more precision, and narrower confidence intervals), and for time-to-event outcomes it also depends on the number of events observed. All these quantities are used in computation of the standard errors of effect estimates from which the confidence interval is derived.

The width of a confidence interval for a meta-analysis depends on the precision of the individual study estimates and on the number of studies combined. In addition, for random-effects models, precision will decrease with increasing heterogeneity and confidence intervals will widen correspondingly (see Chapter 10, Section 10.10.4 ). As more studies are added to a meta-analysis the width of the confidence interval usually decreases. However, if the additional studies increase the heterogeneity in the meta-analysis and a random-effects model is used, it is possible that the confidence interval width will increase.

Confidence intervals and point estimates have different interpretations in fixed-effect and random-effects models. While the fixed-effect estimate and its confidence interval address the question ‘what is the best (single) estimate of the effect?’, the random-effects estimate assumes there to be a distribution of effects, and the estimate and its confidence interval address the question ‘what is the best estimate of the average effect?’ A confidence interval may be reported for any level of confidence (although they are most commonly reported for 95%, and sometimes 90% or 99%). For example, the odds ratio of 0.80 could be reported with an 80% confidence interval of 0.73 to 0.88; a 90% interval of 0.72 to 0.89; and a 95% interval of 0.70 to 0.92. As the confidence level increases, the confidence interval widens.

There is logical correspondence between the confidence interval and the P value (see Section 15.3.3 ). The 95% confidence interval for an effect will exclude the null value (such as an odds ratio of 1.0 or a risk difference of 0) if and only if the test of significance yields a P value of less than 0.05. If the P value is exactly 0.05, then either the upper or lower limit of the 95% confidence interval will be at the null value. Similarly, the 99% confidence interval will exclude the null if and only if the test of significance yields a P value of less than 0.01.

Together, the point estimate and confidence interval provide information to assess the effects of the intervention on the outcome. For example, suppose that we are evaluating an intervention that reduces the risk of an event and we decide that it would be useful only if it reduced the risk of an event from 30% by at least 5 percentage points to 25% (these values will depend on the specific clinical scenario and outcomes, including the anticipated harms). If the meta-analysis yielded an effect estimate of a reduction of 10 percentage points with a tight 95% confidence interval, say, from 7% to 13%, we would be able to conclude that the intervention was useful since both the point estimate and the entire range of the interval exceed our criterion of a reduction of 5% for net health benefit. However, if the meta-analysis reported the same risk reduction of 10% but with a wider interval, say, from 2% to 18%, although we would still conclude that our best estimate of the intervention effect is that it provides net benefit, we could not be so confident as we still entertain the possibility that the effect could be between 2% and 5%. If the confidence interval was wider still, and included the null value of a difference of 0%, we would still consider the possibility that the intervention has no effect on the outcome whatsoever, and would need to be even more sceptical in our conclusions.

Review authors may use the same general approach to conclude that an intervention is not useful. Continuing with the above example where the criterion for an important difference that should be achieved to provide more benefit than harm is a 5% risk difference, an effect estimate of 2% with a 95% confidence interval of 1% to 4% suggests that the intervention does not provide net health benefit.

15.3.2 P values and statistical significance

A P value is the standard result of a statistical test, and is the probability of obtaining the observed effect (or larger) under a ‘null hypothesis’. In the context of Cochrane Reviews there are two commonly used statistical tests. The first is a test of overall effect (a Z-test), and its null hypothesis is that there is no overall effect of the experimental intervention compared with the comparator on the outcome of interest. The second is the (Chi 2 ) test for heterogeneity, and its null hypothesis is that there are no differences in the intervention effects across studies.

A P value that is very small indicates that the observed effect is very unlikely to have arisen purely by chance, and therefore provides evidence against the null hypothesis. It has been common practice to interpret a P value by examining whether it is smaller than particular threshold values. In particular, P values less than 0.05 are often reported as ‘statistically significant’, and interpreted as being small enough to justify rejection of the null hypothesis. However, the 0.05 threshold is an arbitrary one that became commonly used in medical and psychological research largely because P values were determined by comparing the test statistic against tabulations of specific percentage points of statistical distributions. If review authors decide to present a P value with the results of a meta-analysis, they should report a precise P value (as calculated by most statistical software), together with the 95% confidence interval. Review authors should not describe results as ‘statistically significant’, ‘not statistically significant’ or ‘non-significant’ or unduly rely on thresholds for P values , but report the confidence interval together with the exact P value (see MECIR Box 15.3.a ).

We discuss interpretation of the test for heterogeneity in Chapter 10, Section 10.10.2 ; the remainder of this section refers mainly to tests for an overall effect. For tests of an overall effect, the computation of P involves both the effect estimate and precision of the effect estimate (driven largely by sample size). As precision increases, the range of plausible effects that could occur by chance is reduced. Correspondingly, the statistical significance of an effect of a particular magnitude will usually be greater (the P value will be smaller) in a larger study than in a smaller study.

P values are commonly misinterpreted in two ways. First, a moderate or large P value (e.g. greater than 0.05) may be misinterpreted as evidence that the intervention has no effect on the outcome. There is an important difference between this statement and the correct interpretation that there is a high probability that the observed effect on the outcome is due to chance alone. To avoid such a misinterpretation, review authors should always examine the effect estimate and its 95% confidence interval.

The second misinterpretation is to assume that a result with a small P value for the summary effect estimate implies that an experimental intervention has an important benefit. Such a misinterpretation is more likely to occur in large studies and meta-analyses that accumulate data over dozens of studies and thousands of participants. The P value addresses the question of whether the experimental intervention effect is precisely nil; it does not examine whether the effect is of a magnitude of importance to potential recipients of the intervention. In a large study, a small P value may represent the detection of a trivial effect that may not lead to net health benefit when compared with the potential harms (i.e. harmful effects on other important outcomes). Again, inspection of the point estimate and confidence interval helps correct interpretations (see Section 15.3.1 ).

MECIR Box 15.3.a Relevant expectations for conduct of intervention reviews

15.3.3 Relation between confidence intervals, statistical significance and certainty of evidence

The confidence interval (and imprecision) is only one domain that influences overall uncertainty about effect estimates. Uncertainty resulting from imprecision (i.e. statistical uncertainty) may be no less important than uncertainty from indirectness, or any other GRADE domain, in the context of decision making (Schünemann 2016). Thus, the extent to which interpretations of the confidence interval described in Sections 15.3.1 and 15.3.2 correspond to conclusions about overall certainty of the evidence for the outcome of interest depends on these other domains. If there are no concerns about other domains that determine the certainty of the evidence (i.e. risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness or publication bias), then the interpretation in Sections 15.3.1 and 15.3.2 . about the relation of the confidence interval to the true effect may be carried forward to the overall certainty. However, if there are concerns about the other domains that affect the certainty of the evidence, the interpretation about the true effect needs to be seen in the context of further uncertainty resulting from those concerns.

For example, nine randomized controlled trials in almost 6000 cancer patients indicated that the administration of heparin reduces the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), with a risk ratio of 43% (95% CI 19% to 60%) (Akl et al 2011a). For patients with a plausible baseline risk of approximately 4.6% per year, this relative effect suggests that heparin leads to an absolute risk reduction of 20 fewer VTEs (95% CI 9 fewer to 27 fewer) per 1000 people per year (Akl et al 2011a). Now consider that the review authors or those applying the evidence in a guideline have lowered the certainty in the evidence as a result of indirectness. While the confidence intervals would remain unchanged, the certainty in that confidence interval and in the point estimate as reflecting the truth for the question of interest will be lowered. In fact, the certainty range will have unknown width so there will be unknown likelihood of a result within that range because of this indirectness. The lower the certainty in the evidence, the less we know about the width of the certainty range, although methods for quantifying risk of bias and understanding potential direction of bias may offer insight when lowered certainty is due to risk of bias. Nevertheless, decision makers must consider this uncertainty, and must do so in relation to the effect measure that is being evaluated (e.g. a relative or absolute measure). We will describe the impact on interpretations for dichotomous outcomes in Section 15.4 .

15.4 Interpreting results from dichotomous outcomes (including numbers needed to treat)

15.4.1 relative and absolute risk reductions.

Clinicians may be more inclined to prescribe an intervention that reduces the relative risk of death by 25% than one that reduces the risk of death by 1 percentage point, although both presentations of the evidence may relate to the same benefit (i.e. a reduction in risk from 4% to 3%). The former refers to the relative reduction in risk and the latter to the absolute reduction in risk. As described in Chapter 6, Section 6.4.1 , there are several measures for comparing dichotomous outcomes in two groups. Meta-analyses are usually undertaken using risk ratios (RR), odds ratios (OR) or risk differences (RD), but there are several alternative ways of expressing results.

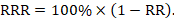

Relative risk reduction (RRR) is a convenient way of re-expressing a risk ratio as a percentage reduction:

For example, a risk ratio of 0.75 translates to a relative risk reduction of 25%, as in the example above.

The risk difference is often referred to as the absolute risk reduction (ARR) or absolute risk increase (ARI), and may be presented as a percentage (e.g. 1%), as a decimal (e.g. 0.01), or as account (e.g. 10 out of 1000). We consider different choices for presenting absolute effects in Section 15.4.3 . We then describe computations for obtaining these numbers from the results of individual studies and of meta-analyses in Section 15.4.4 .

15.4.2 Number needed to treat (NNT)

The number needed to treat (NNT) is a common alternative way of presenting information on the effect of an intervention. The NNT is defined as the expected number of people who need to receive the experimental rather than the comparator intervention for one additional person to either incur or avoid an event (depending on the direction of the result) in a given time frame. Thus, for example, an NNT of 10 can be interpreted as ‘it is expected that one additional (or less) person will incur an event for every 10 participants receiving the experimental intervention rather than comparator over a given time frame’. It is important to be clear that:

- since the NNT is derived from the risk difference, it is still a comparative measure of effect (experimental versus a specific comparator) and not a general property of a single intervention; and

- the NNT gives an ‘expected value’. For example, NNT = 10 does not imply that one additional event will occur in each and every group of 10 people.

NNTs can be computed for both beneficial and detrimental events, and for interventions that cause both improvements and deteriorations in outcomes. In all instances NNTs are expressed as positive whole numbers. Some authors use the term ‘number needed to harm’ (NNH) when an intervention leads to an adverse outcome, or a decrease in a positive outcome, rather than improvement. However, this phrase can be misleading (most notably, it can easily be read to imply the number of people who will experience a harmful outcome if given the intervention), and it is strongly recommended that ‘number needed to harm’ and ‘NNH’ are avoided. The preferred alternative is to use phrases such as ‘number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome’ (NNTB) and ‘number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome’ (NNTH) to indicate direction of effect.

As NNTs refer to events, their interpretation needs to be worded carefully when the binary outcome is a dichotomization of a scale-based outcome. For example, if the outcome is pain measured on a ‘none, mild, moderate or severe’ scale it may have been dichotomized as ‘none or mild’ versus ‘moderate or severe’. It would be inappropriate for an NNT from these data to be referred to as an ‘NNT for pain’. It is an ‘NNT for moderate or severe pain’.

We consider different choices for presenting absolute effects in Section 15.4.3 . We then describe computations for obtaining these numbers from the results of individual studies and of meta-analyses in Section 15.4.4 .

15.4.3 Expressing risk differences

Users of reviews are liable to be influenced by the choice of statistical presentations of the evidence. Hoffrage and colleagues suggest that physicians’ inferences about statistical outcomes are more appropriate when they deal with ‘natural frequencies’ – whole numbers of people, both treated and untreated (e.g. treatment results in a drop from 20 out of 1000 to 10 out of 1000 women having breast cancer) – than when effects are presented as percentages (e.g. 1% absolute reduction in breast cancer risk) (Hoffrage et al 2000). Probabilities may be more difficult to understand than frequencies, particularly when events are rare. While standardization may be important in improving the presentation of research evidence (and participation in healthcare decisions), current evidence suggests that the presentation of natural frequencies for expressing differences in absolute risk is best understood by consumers of healthcare information (Akl et al 2011b). This evidence provides the rationale for presenting absolute risks in ‘Summary of findings’ tables as numbers of people with events per 1000 people receiving the intervention (see Chapter 14 ).

RRs and RRRs remain crucial because relative effects tend to be substantially more stable across risk groups than absolute effects (see Chapter 10, Section 10.4.3 ). Review authors can use their own data to study this consistency (Cates 1999, Smeeth et al 1999). Risk differences from studies are least likely to be consistent across baseline event rates; thus, they are rarely appropriate for computing numbers needed to treat in systematic reviews. If a relative effect measure (OR or RR) is chosen for meta-analysis, then a comparator group risk needs to be specified as part of the calculation of an RD or NNT. In addition, if there are several different groups of participants with different levels of risk, it is crucial to express absolute benefit for each clinically identifiable risk group, clarifying the time period to which this applies. Studies in patients with differing severity of disease, or studies with different lengths of follow-up will almost certainly have different comparator group risks. In these cases, different comparator group risks lead to different RDs and NNTs (except when the intervention has no effect). A recommended approach is to re-express an odds ratio or a risk ratio as a variety of RD or NNTs across a range of assumed comparator risks (ACRs) (McQuay and Moore 1997, Smeeth et al 1999). Review authors should bear these considerations in mind not only when constructing their ‘Summary of findings’ table, but also in the text of their review.

For example, a review of oral anticoagulants to prevent stroke presented information to users by describing absolute benefits for various baseline risks (Aguilar and Hart 2005, Aguilar et al 2007). They presented their principal findings as “The inherent risk of stroke should be considered in the decision to use oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation patients, selecting those who stand to benefit most for this therapy” (Aguilar and Hart 2005). Among high-risk atrial fibrillation patients with prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack who have stroke rates of about 12% (120 per 1000) per year, warfarin prevents about 70 strokes yearly per 1000 patients, whereas for low-risk atrial fibrillation patients (with a stroke rate of about 2% per year or 20 per 1000), warfarin prevents only 12 strokes. This presentation helps users to understand the important impact that typical baseline risks have on the absolute benefit that they can expect.

15.4.4 Computations

Direct computation of risk difference (RD) or a number needed to treat (NNT) depends on the summary statistic (odds ratio, risk ratio or risk differences) available from the study or meta-analysis. When expressing results of meta-analyses, review authors should use, in the computations, whatever statistic they determined to be the most appropriate summary for meta-analysis (see Chapter 10, Section 10.4.3 ). Here we present calculations to obtain RD as a reduction in the number of participants per 1000. For example, a risk difference of –0.133 corresponds to 133 fewer participants with the event per 1000.

RDs and NNTs should not be computed from the aggregated total numbers of participants and events across the trials. This approach ignores the randomization within studies, and may produce seriously misleading results if there is unbalanced randomization in any of the studies. Using the pooled result of a meta-analysis is more appropriate. When computing NNTs, the values obtained are by convention always rounded up to the next whole number.

15.4.4.1 Computing NNT from a risk difference (RD)

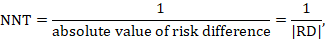

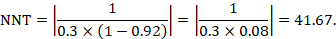

A NNT may be computed from a risk difference as

where the vertical bars (‘absolute value of’) in the denominator indicate that any minus sign should be ignored. It is convention to round the NNT up to the nearest whole number. For example, if the risk difference is –0.12 the NNT is 9; if the risk difference is –0.22 the NNT is 5. Cochrane Review authors should qualify the NNT as referring to benefit (improvement) or harm by denoting the NNT as NNTB or NNTH. Note that this approach, although feasible, should be used only for the results of a meta-analysis of risk differences. In most cases meta-analyses will be undertaken using a relative measure of effect (RR or OR), and those statistics should be used to calculate the NNT (see Section 15.4.4.2 and 15.4.4.3 ).

15.4.4.2 Computing risk differences or NNT from a risk ratio

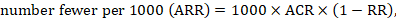

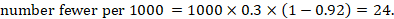

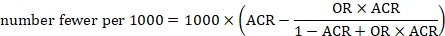

To aid interpretation of the results of a meta-analysis of risk ratios, review authors may compute an absolute risk reduction or NNT. In order to do this, an assumed comparator risk (ACR) (otherwise known as a baseline risk, or risk that the outcome of interest would occur with the comparator intervention) is required. It will usually be appropriate to do this for a range of different ACRs. The computation proceeds as follows:

As an example, suppose the risk ratio is RR = 0.92, and an ACR = 0.3 (300 per 1000) is assumed. Then the effect on risk is 24 fewer per 1000:

The NNT is 42:

15.4.4.3 Computing risk differences or NNT from an odds ratio

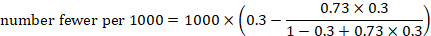

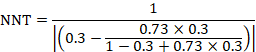

Review authors may wish to compute a risk difference or NNT from the results of a meta-analysis of odds ratios. In order to do this, an ACR is required. It will usually be appropriate to do this for a range of different ACRs. The computation proceeds as follows:

As an example, suppose the odds ratio is OR = 0.73, and a comparator risk of ACR = 0.3 is assumed. Then the effect on risk is 62 fewer per 1000:

The NNT is 17:

15.4.4.4 Computing risk ratio from an odds ratio

Because risk ratios are easier to interpret than odds ratios, but odds ratios have favourable mathematical properties, a review author may decide to undertake a meta-analysis based on odds ratios, but to express the result as a summary risk ratio (or relative risk reduction). This requires an ACR. Then

It will often be reasonable to perform this transformation using the median comparator group risk from the studies in the meta-analysis.

15.4.4.5 Computing confidence limits

Confidence limits for RDs and NNTs may be calculated by applying the above formulae to the upper and lower confidence limits for the summary statistic (RD, RR or OR) (Altman 1998). Note that this confidence interval does not incorporate uncertainty around the ACR.

If the 95% confidence interval of OR or RR includes the value 1, one of the confidence limits will indicate benefit and the other harm. Thus, appropriate use of the words ‘fewer’ and ‘more’ is required for each limit when presenting results in terms of events. For NNTs, the two confidence limits should be labelled as NNTB and NNTH to indicate the direction of effect in each case. The confidence interval for the NNT will include a ‘discontinuity’, because increasingly smaller risk differences that approach zero will lead to NNTs approaching infinity. Thus, the confidence interval will include both an infinitely large NNTB and an infinitely large NNTH.

15.5 Interpreting results from continuous outcomes (including standardized mean differences)

15.5.1 meta-analyses with continuous outcomes.

Review authors should describe in the study protocol how they plan to interpret results for continuous outcomes. When outcomes are continuous, review authors have a number of options to present summary results. These options differ if studies report the same measure that is familiar to the target audiences, studies report the same or very similar measures that are less familiar to the target audiences, or studies report different measures.

15.5.2 Meta-analyses with continuous outcomes using the same measure