Featured Cases

Crianca Feliz: Brazil’s Ambitious Early Childhood Program

LaToya Cantrell, Mayor of New Orleans: A Political ‘Outsider’ Takes Charge of City Hall

Paying to Improve Girls’ Education: India’s First Development Impact Bond

Colombia’s Peace Negotiations: Finding Common Ground After 50 Years of Armed Conflict

The Mosquito Network: Global Governance in the Fight to Eliminate Malaria Deaths

Operation Pufferfish: Building and Sustaining a Department of Neighborhoods and Citizen Engagement in Lansing, Michigan

"The Toughest Beat": Investing in Employee Well-Being at the Denver Sheriff Department

Charting a Course for Boston: Organizing for Change

Expert Tips on Performing Effective Project Management in Government

By Kate Eby | October 29, 2020 (updated September 15, 2023)

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Link copied

In government agencies, strong project management helps ensure that government programs are effective and cost-efficient for taxpayers. This article includes tips and expert advice on performing effective government project management.

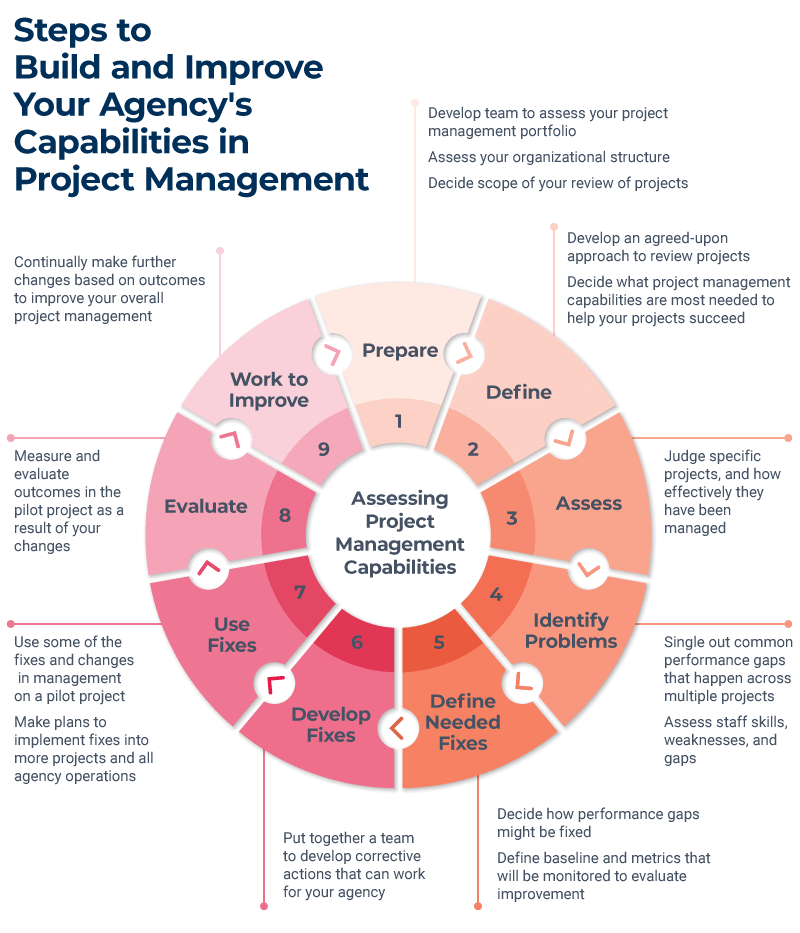

Include on this page, you’ll find the role of project management in government , examples of successful implementation of project management in government organizations , a roadmap for assessing your agency's PM performance (and how to improve it), and tips on overcoming challenges within government to achieve strong project management .

The Role of Project Management in Government

While government workers have used project management in project-based work for 50 years, they have increasingly used PM to drive public sector work forward in recent decades. Today, project management is used in all sectors and levels of government.

Below are some details about project work and project management within government agencies:

- Many people, including congressional leaders, political appointees, government workers, and citizens, advocate for improved and more efficient government operations. Most government improvement initiatives use project management to improve government operations.

- Many government projects today must deliver value in a limited amount of time and with limited resources, due to cutbacks in funding for various government agencies.

- Government agencies increasingly employ the principles of project management . But like all organizations, they still often waste significant money on inefficient project work. The Project Management Institute’s 2020 Pulse of the Profession report found that all organizations, including government organizations, waste 11.4 percent of each dollar invested in projects through poor performance — that’s $114 million for every $1 billion invested.

- Government agencies are outsourcing more work to private contractors, which requires government workers to manage the contractors, along with government employees, to move projects forward.

- Government organizations want to use effective project management to demonstrate their own value and viability.

- Project management provides a framework for better customer service, which is increasingly important within government agencies.

- As in private industry, government organizations need to give the public around-the-clock secure access to data, which requires more efficient work.

Senapathy says people wrongly perceive that good project management isn’t as important in government because it isn’t profit-driven, unlike private industry. “It is a misconception that project management is necessary only where profitability matters,” he says. “The government has similar responsibilities to the taxpayer. For every tax dollar that’s paid, you are accountable. The deal is everyone is eventually accountable. There is no free lunch.”

In fact, Senapathy says, “I think it is even more critical for the government to be invested in project management than private enterprise. Government projects are subjected to microscopic scrutiny from individual citizens in informal forums to formal congressional hearings.”

Stephen Townsend, Director, Network Programs, for the Project Management Institute , says the government must deliver value for its citizens, just as corporations do for shareholders. “That value can be through national security, roads, and infrastructure or service programs,” he says. “A strong project management discipline helps government deliver the right solutions efficiently and effectively.”

Project Management Guide

Your one-stop shop for everything project management

Ready to get more out of your project management efforts? Visit our comprehensive project management guide for tips, best practices, and free resources to manage your work more effectively.

View the guide

Benefits of Government Project Management

Here are some additional benefits of good project management for government operations:

- It provides insights into whether a project is worth taking on. “If the project has little likelihood to succeed or represents a highly risky venture, a good business case and review process can stop agencies from making poor investments,” says Townsend.

- It puts in place structures that enable teams to do work consistently across all projects and throughout the organization.

- It increases efficiency in responding to disasters or disturbances, including a pandemic. “In terms of the pandemic, having a consistent organization process allows for a seamless integration of work,” says Senapathy. “What if project management didn’t exist? The government entities and employees would all be scrambling.” Project management work and philosophies “allow us not to be reactive but proactive,” Senapathy says. “This pandemic has been the single biggest example of how quickly this country can respond ... Project management can do brilliant things.”

- It helps avoid the reinvention of project tools and techniques for each project that you take on.

- It provides workers with access to past data, past work, and best practices in project management, which helps ensure more consistent and better project execution.

- It monitors whether project deliverables are completed (and on time).

- It helps employees understand their responsibilities in completing the work.

- It helps project teams and leaders report on progress to agency and government leaders.

- It offers a structured proving ground for new project management strategies.

- It allows agencies to better adapt to new technologies, because they become part of structured project management.

- Project work can affect a range of stakeholders, including many outside the government agency doing the work. Good project management allows workers to better communicate with those stakeholders and address concerns.

- It allows people to better understand effective ways to solve problems.

Challenges of Government Project Management

Workers will encounter a number of challenges to managing government projects, including poor support from government leaders, government rules that impede the work, and limited money for worker training.

Here are some challenges to good government project management:

- Limited Knowledge about Project Management Principles: For years, government agencies inconsistently used standard project management principles in their work. Today, more government workers understand project management, but many senior managers still have limited knowledge that can affect how they deploy project management.

- Poor Institutional Support: Because of limited knowledge, leaders of government agencies may not understand the value of project management. This means many agencies offer little financial support or other resources.

- Instability of Sponsorship: Government tends to experience high turnover in agency leadership, and elections can bring in newly elected leaders to oversee these agencies. All of this change can hinder progress on government projects.

- Agency Employees Dispersed Geographically: Some government agencies have employees in a number of geographically separate offices, which can make overseeing a PM team more difficult. (This may be more common in government than in the private sector.)

- Government Hiring and Employment Policies: To complete a project, team leaders may rely on specialists drawn from different areas within an agency or with other agencies. Government hiring and employment policies can make that difficult.

- Less Effective Collaboration within Agencies and Departments: It’s not unusual to have structures within private companies that impede collaboration, but that tendency is more pronounced within and among government agencies. “The interplay between various departments is much more synchronous in private industry than in government,” says Senapathy. “The interplay doesn’t work as efficiently [in government].”

- Overall Bureaucratic Environment: Even beyond identifiable rules and regulations, government agencies often operate in an environment where written and unwritten rules dominate all processes. This means they are often resistant to change or quick action on problems.

- Employees Who Don’t Understand or Use Project Management Lexicon: Project management training allows workers to understand common language pertaining to effective project management. Government employees can be ignorant of or resistant to that language. “Integrating modern project management lexicon into an established culture of business language that has been in use for decades presents unique challenges of organizational change management,” says Senapathy.

- Incremental Thinking Is the Norm: Governmental agencies often only accept slow or incremental change, if any at all.

- Ingrained Processes and Tools: Governments often lack the drive that exists in many private companies to continuously innovate to improve their tools and processes.

- Minimal Funds for Training: Government agencies might have limited funds to train leaders in project management. Those funds often are also the first to be cut when budgets need to be pared down. “Prioritizing training for program management roles across several leadership levels and multiple business lines may be a significant challenge since the education-related budget is one of the earliest victims of belt-tightening,” says Senapathy.

How Good Project Management Can Bring Positive Change in Government

Good project management can do more than bring about successful projects. It can change how government works, increase flexibility, and engender a culture of innovation within government agencies.

Here are some significant ways that project management can change government agencies:

- Project Management Can Be a Lever of Change: Many government agencies are change-averse. Good project management inherently brings about positive change. Team members should recognize their potential role as change agents.

- Project Management Increases Flexibility: As mentioned above, government agencies often operate within bureaucratic, inflexible environments. But good project management should allow agency leaders and employees to make needed adjustments in how they plan and execute work.

- Project Management Fosters Innovation: Government agencies are increasingly looking for ways to better serve the public. Much of that government innovation springs from project management. An example is a new employee incentive program in the federal government called Securing Americans Value and Efficiency ( SAVE ). The program rewards employees who come up with ideas that improve efficiencies and save money.

How to Implement a Project Management Culture in Government

It can be challenging to implement a project management culture in government. But, management leaders can do it — they just have to focus on everything from education and training to the development of methodologies to appropriate oversight.

First, federal agencies should be aware of job candidates with a Project Management Professional (PMP) certification from the Project Management Institute. The certification recognizes a level of knowledge and expertise in project management. Many project managers, in private industry and government, have that certification.

ESI International, a Virginia-based project management training company, has identified several other steps to implement project management within a government organization, including the following:

- Education and Training: Proper worker education and training provide the foundation for the cultural changes that can foster good project management.

- Maturity and Capability Assessments: Organizations must assess and understand their strengths and weaknesses in doing project management work. They should also make improvements where needed.

- Methodology Development: Leaders must create and follow consistent methodologies that guide how workers tackle a project. Doing so can help workers avoid having to reinvent processes and tools for every project.

- Project Execution Support: Organizations must support project managers in the work on actual projects. This might include hiring experienced coaches and mentors who can transfer their knowledge to workers so that they help projects succeed.

- Center of Competence: A centralized office can provide strategic oversight to projects throughout a government agency. It can also provide project management expertise and support.

- Strategic Oversight: Top leaders in an organization must stay involved in the organization’s project management process. They can make sure the organization’s projects align the organization’s overall goals.

What Is Earned Value Management in Project Management?

Earned value management is a method that tracks how much work has been accomplished on a project and how much of the budget has been spent on a project at any point.

Earned value management is an important part of project management in government and often required in federal government projects. The Department of Defense and NASA has used earned value management since the 1960s.

Using this method, PMs track total project work finished, along with hours and money spent on a project. They can then compare that to the total project budget. That allows team members to assess whether they are ahead of or behind schedule. And it allows them to assess whether they are over or under budget in their spending.

“Earned value management is one of the higher-emphasized areas in all of government project management,” says Ramirez. “That’s how you get visibility into what’s going on.”

A Program Management Framework to Help Guide Federal Technology Purchases

In 2015, the Project Manage Institute published a white paper that offers guidance and a framework for how federal agencies can use project management to improve the way they buy new or modify existing computer systems. You can read more about the PMI Standards Framework .

Common Project Management Frameworks

Regulations, guidelines, and certifications for federal government.

In 2016, the federal government approved a law to improve project management in federal work, established other regulations governing project management, and has created a special certification for government managers who prove their competence in project management. All of these are detailed below.

Program Management Improvement Accountability Act

In December 2016, President Obama signed into law the Program Management Improvement Accountability Act (PMIAA). In June 2018, the federal Office of Management and Budget issued Memorandum M-18-19 that established the federal government’s initial guidance to federal agencies in implementing the law. The law aims to ensure that federal workers use proven practices in managing programs and projects throughout the federal government. It achieves the following, among other goals:

- Sets up a framework to improve policy, staffing, and training in program and project management

- Ensures that management leaders conduct reviews of programs and projects to make sure they are well-managed

- Coordinates the development of policies and processes to continually improve project and program management

Project management leaders make a distinction between management of projects and programs. In this context, a project is a defined amount of work that an organization’s employees do to create or modify a product or service. A program is a group of related projects and operational activities. Managers coordinate these projects and activities to provide more overall benefit than if employees had managed them separately.

Procurement Regulations in Project Management

The federal government mandates certain actions in project management when it involves purchasing assets for the government, including buying or modifying computer technology. Regulations include the Federal Acquisition Regulation and the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act.

The Federal Acquisition Certification for Program and Project Managers

The federal government has established a special certification through which federal managers can prove their competence in program and project management. The certification is called the Federal Acquisition Certification for Program and Project Managers (FAC-P/PM). The certification is recognized by all federal agencies, except for the Department of Defense.

The certification focuses on essential competencies needed for program and project managers.

It offers three levels of certification:

- Entry/Apprentice: This level means the person has the ability to manage low-risk and simple projects.

- Midlevel/Journeyman: This means the person has the ability to manage projects with low- or moderate-level risks. The person also can apply basic management practices to projects.

- Senior/Expert: This person can manage and evaluate moderate to high-risk programs and projects. The person has significant knowledge and experience in project management practices.

California Project Management Recommendations for State Workers

Some states offer specific guidance about project management to state employees. The California Project Management Office, for example, has created a 461-page document providing a framework for project management in California state agencies. The document provides guidance and insights on project management methods. You can read the official documentation for more information.

Examples of Successful Government PM Implementation

Local, state, and federal government agencies have used project management to successfully complete tens of thousands of projects. Here are just a few examples:

- Michigan Office of Project Management: The state of Michigan’s information technology projects were often behind schedule, over budget, or both. To change that, the state created an Office of Project Management and built an infrastructure that helped establish a project management culture with state workers. Then leaders built a project management support structure to help all state government agencies, which allowed the state to integrate project management into much of the state’s daily business activities. To learn more about the project, visit “ Implementing a project management culture in a government organization .”

- New Orleans VA Hospital: In 2005, Hurricane Katrina destroyed thousands of buildings in New Orleans, Louisiana. Among those buildings was a Department of Veterans Affairs hospital complex where doctors and other medical providers trained medical students, conducted medical research, and served 40,000 military families. In 2006, Congress approved funding for a replacement complex of buildings that would encompass 1.6 million square feet. From the beginning, project leaders focused intently on understanding risks to the project, listening to stakeholders, and preventing inefficient changes in scope. They finished the three phases of the hospital complex on time, and the project’s final cost was 14 percent under budget. To learn more, visit “ Department of Veterans Affairs Realizes Benefits through Improved Healthcare for Veterans .”

- Department of Justice Website: By 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice website included more than 450,000 web pages, documents, and files. Lawyers, law enforcement officials, and many other citizens valued the information provided. But more than 100 offices of the department needed to maintain their own sections of the website using a wide range of processes and technologies. The website was becoming a huge burden to maintain. The Department of Justice’s project team decided to use a Scrum Agile methodology to rebuild the website in increments. The first job in the project was to build a website content management system and launch one section of the website. Eventually, there would be 120 sections in 12 major version releases. The incremental approach allowed website users to provide feedback on the first release, which became input on making changes in the second and later releases. Each release provided users with more functions, and each took less time to finish. To learn more, visit “ Case Study: Agile Government and the Department of Justice .”

Best Practices and Expert Tips for Effective Government Project Management

Experts offer a number of recommendations that can help leaders and workers to perform effective project management. Tips include requiring the buy-in of top organization leaders, understanding risks at the beginning of the project, and employing a mix of strategies.

Here are some additional expert recommendations and tips:

- Seek Top Leadership Buy-In for the Structure and Strategies: Organization leaders need to understand the principles of good project management and approve the overall strategies to get projects done. Without that, financial and other support for the work will be tentative and can be abandoned at any time. Support from organization leaders will also translate into more support from employees throughout the organization. “The buy-in (for the project and processes) should start at the top and not at the bottom,” says Senapathy, from the Project Management Training Institute. “The government needs to emphasize the discipline of project management from the top down,” says Ramirez, from the Institute for Neuro & Behavioral Project Management. “And it has to be a focused area — just as focused as safety, cost management, the production of the technical product you’re delivering or building.”

- Think about and Listen to All Stakeholders That the Project Might Affect: A wide range of people might be affected by a project — beyond one agency and even beyond the end-users. It’s important to understand everyone who might be affected and how they might react to the work. “Stakeholders represent any individual or group who is affected by or perceives themselves as affected by the project and its outputs,” says Townsend, with the Project Management Institute. “Stakeholders can affect every aspect of a project, including its plans, costs, and schedule. Understanding who the stakeholders are, how to engage with them, and how to balance potential conflicts among them is important.”

- Create a Plan and Provide Clear Direction Before You Start: If you’re using Agile methodologies to move forward a project, planning will likely be different from other project management methods. In any case, you need to set broad goals and make sure your team understands those goals. “Starting too early can mean that goals are unclear or misunderstood (and) key requirements get missed,” says Townsend. “Good, upfront planning with regular reviews of the plan through the project lifecycle can make a big difference in success rates.”

- Monitor Progress Well: Especially in more traditional project management, it’s imperative that the team monitors benchmarks, deadlines, and progress.

- Made Quick Adjustments Based on Monitoring: Your team must quickly make adjustments if your monitoring shows missed benchmarks or deadlines or other issues. This is especially true in government projects that could involve large budgets. “The sooner you catch things, the better you are in preventing (problems) and the draining away of millions of dollars,” Senapathy says.

- Be Selective: Don’t try to perform a wide range of projects that affect many agency operations all at once. Pick projects, and get leadership buy-in, that can improve operations in a specific area. That way you don’t cause chaos throughout your organization.

- Envision Your Success: Envision and articulate a path toward the project result and what that result will look like. You can do that in part through setting down the scope of the project.

- Make Sure Your Project Provides What the Intended Beneficiary Needs: “Most important, good project management ensures that the result meets the needs of its intended beneficiaries,” says Townsend. “If a result is produced quickly with all of the promised features but fails to meet the needs of the people who will use that result, the project has failed.”

- Bring Together Your “A-Team”: Pick some of your organization’s brightest minds to be part of the project team — even if their job description doesn’t suggest they fit. The brightest minds can envision bigger goals and foster real innovation.

- Integrate Employee Development and Career Goals with Project Management: Employees will respond more intently to project work when their job descriptions and rewards are influenced by their project management work. “There’s got to be motivation from individuals to take greater responsibility” for project success, Senapthy says.

- Think about Behavioral Economics and the Science of Human Behavior: Progress on any human work must take into account how humans make decisions, says Ramirez, from Institute for Neuro & Behavioral Project Management. “We don’t focus enough on the behavioral piece,” he says. “Progress in the government, private sector, or any organization is going to be slower when you do not incorporate the human factors that go into it.” That means organizations must think about why people make the decisions they do, including financial incentives, job security, and agreeing with superiors.

- Know the Risks Involved in Your Project: At the outset of every project, project leaders and team members need to assess the risks and challenges inherent to the project. From there, make adjustments or take other measures to deal with those risks. “Risk management considers factors that can negatively or positively impact a project and its results,” says Townsend. “Some risks can derail projects while others may enable teams to accelerate or increase value delivery. Good risk management keeps those threats and opportunities visible throughout the project so the team can mitigate risks and take advantage of opportunities. ”Ramirez says some risk analysis doesn’t go far enough in acknowledging human factors, however. This includes a disincentive to acknowledge risks in some areas, like how a risk might affect their jobs, or the opinions and views or their superiors in the agency. “There are many incentives to avoid considering additional risks,” Ramirez says. Those disincentives must be dealt with and considered by project leaders, he says.

- Start Small, and Scale Up: If your agency is just starting to deploy formal project management, start with a smaller project. Testing the process on a smaller or shorter-term project will allow team members to understand and tweak processes before moving on to a bigger project.

- Be Nimble and Willing to Employ a Mix of Strategies: “A real-life project needs to be nimble,” says Senapathy. That might mean that project leaders use a traditional project management framework, like Waterfall, for one portion of the project, and then use an Agile-based Scrum framework for another portion. “Keep the processes flexible,” he says. (To learn more about different project management methodologies, visit “ What's the Difference? Agile vs Scrum vs Waterfall vs Kanban. ”) “In general, since projects never fall into a theoretical bucket of a framework, it is perfectly fine to mix and match traditional and agile methodologies to gain maximum performance from available budget and schedule,” says Senapathy.

Streamline Project Management in Government with Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.

Discover why over 90% of Fortune 100 companies trust Smartsheet to get work done.

Using PRINCE2® to manage US Federal Government IT Projects

- Project management

- Project planning

- Project progress

September 30, 2015 |

24 min read

All of our White Papers and Case Studies are subject to the following Terms of Use .

This White Paper was originally published in September 2009, and was updated in September 2015.

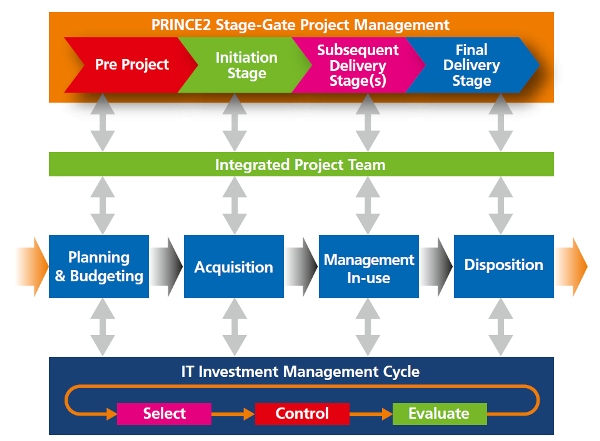

This paper shows how the PRINCE2® project management method supports US Federal government project managers as they deliver IT investments while satisfying requirements of the Clinger-Cohen Act and Capital Planning and Investment Control.

Since enactment of the Clinger-Cohen Act (CCA) in 1996, the US Federal government requires its agencies to improve their management, oversight and control of investments in information technology. Central to the CCA is an obligation for agencies to select, control, and evaluate their portfolio of IT projects in accordance with the principles of Capital Planning and Investment Control (CPIC), an approach to IT investment management referenced in the CCA.

In the same year the CCA was signed into effect, the UK government released PRINCE2, a principles and themes based project management method designed to provide direction and oversight of government/contractor projects. Project managers can find it difficult to meet the requirements of CPIC while running a project. Industry leading project management guides suggest one approach, contractors have another, while investment oversight groups within the agency reinforce the additional requirements of CCA onto the project team.

Capital Planning and Investment Control

The Information Technology Management Reform Act of 1996, commonly referred to as the CCA, requires US Federal agencies to “identify and collect information regarding best practices” for managing IT related projects. The CCA identifies the government’s approach to information technology investment management as Capital Planning and Investment Control (CPIC). Specifically, the CCA, through oversight from the President’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB), requires each agency to institute effective and efficient capital planning processes for selecting, controlling, and evaluating their investments in IT projects. These projects represent the strategic investment in IT capital assets that define an agency’s IT portfolio.

OMB requires each agency to institute effective capital planning.

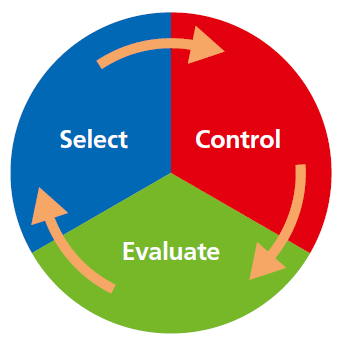

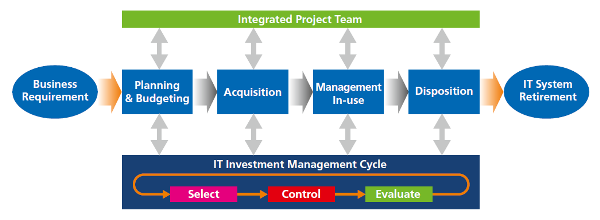

The CCA references use of a three-phase cycle for capital asset management to provide oversight of investment budgeting and spending. First, by selecting IT capital asset investments that will support core mission functions performed by the Federal Government; Next, through controlling their projects effectively through the application of best practices in project and performance management; And then, by evaluating investment results through a demonstration that the return on investment is supporting initial business case objectives. CPIC links the strategic planning of mission attainment to the tactical performance of project delivery and IT systems operations. The three phases of CCA’s IT Investment Management process are performed annually, and applied to IT investments continuously, throughout the life of an asset’s existence within the agency’s IT portfolio.

Select, Control and Evaluate

Figure 1.1 IT Investment Management Cycle

The Control phase is an ongoing investment management process designed to monitor the progress of IT projects against budgeted cost, schedule, performance goals, and expected mission benefits. The Control Phase helps to ensure that each investment is properly managed toward the intended objectives defined by the investment’s business case. However, the Control process does not manage the investment project. The responsibility to define a project management governance model is left to the agency and the project manager. It is not defined by CPIC.

In the Evaluate phase, project outcomes are measured, and systems are determined to be fit for purpose. Performance results are assessed to: (1) identify needed changes to products or systems to maintain optimal business operations; (2) measure the project’s effect on mission and strategic goals; and (3) continuously improve the agency’s investment management processes based on lessons learned, self-assessments and benchmarking.

The Challenges of CPIC

Interpretation of the CCA and CPIC has led to conflicting and competing solutions to satisfy its many requirements. OMB continues to amend their supporting Circular A-11, which keeps agencies’ reporting requirements a moving target.

Practitioners often confuse the cyclical phases of the CCA’s Select-Control-Evaluate as a project management lifecycle, for example, thinking that a project is in development activities only during the Control phase. This is inaccurate. The three phases of the CPIC IT Investment Management lifecycle define the sequence of when budget and investment management activities occur to plan, monitor and report the progress of IT investment dollars. The “project” lifecycle of CPIC has a linear progression, from Planning and Acquisition, to Management In-Use and Disposition. It starts when a business need is first defined and IT systems planning activities warrant a new project initiative, then continues to product acquisition/development, systems operation (production), and then asset retirement. In response to this, agencies should define and operate an enterprise lifecycle management framework that integrates governance, processes and information into a decision model that includes the requirements of investment and acquisition management, enterprise architecture planning, project management office (PMO), IT systems operations and maintenance, and capital asset control.

CPIC defines the activities of budget and investment management.

Project managers react to the oversight and governance of CPIC as a set of tasks and requirements that are in addition to their effort to running the project. This has led to frustration while project managers work to deliver their projects. Project managers sometimes view CPIC reporting as a “check the box” activity. Maintaining compliance to CPIC reporting can take considerable effort if it is not integrated to the project governance approach. However, when CPIC reporting is a pre-defined output designed into the project method, CPIC becomes integral with the other daily management and decision-making activities of project management.

Additional challenges face government project managers. The goals of CPIC are focused on budget management, not project management, which creates conflict in tactical management objectives. IT Investment Management support offices within the agencies are tasked with collecting and reporting financial information from the agency’s projects, while project managers focus on performance to cost and schedule milestones, earned value management, risk and issue status, and baseline change control logs. Too often, the data and information that reports project status is gathered using tools and techniques that are in contrast with the investment management reporting requirements of the CCA, CPIC and OMB.

Finding a Solution to CPIC

Project managers are searching for a governance model that can support both the day-to-day needs of project delivery and the requirements of CPIC investment management reporting. While the PMI’s Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge® is clear in identifying tools and techniques for performing project management activities, it is by its own admission “a guide rather than a methodology”, and it is not designed to address compliance requirements, such as those defined by CCA. To operate a project in a way that will achieve the needs of CPIC, project managers must utilize a method that supports sustainment of an investment business case, clearly identifies a governance process, and lends itself to regular reviews for “Go/No-Go” decisions, as required by US government IT investment management budget cycles.

Satisfying the requirements and objectives of CPIC is not easy. However, with the right project management method the project of CPIC while controlling and delivering the project. You must use a method that defines how and when to apply project management processes and techniques. The method must be scalable to the size of the investment, and it must define governance, tools and techniques that can balance the pulling forces that may exist between government and contractor. PRINCE2 is a de facto standard project management method from the UK government. It is public domain, available for anyone to use to manage a project, it can support the many requirements of CCA and CPIC, and it can be tailored to fit most any size project.

What is PRINCE2?

commissioned by the UK government. In 1989, the Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency (CCTA) of the UK government first established PRINCE (PRojects IN Controlled Environments) for controlling information systems projects, but the method soon realized a greater following. The UK Office of Government Commerce (OGC), continued development of the method into what is now PRINCE2 (2009). Since then the UK Government created by the Cabinet Office has set up a joint venture with Capita plc called AXELOS. AXELOS is responsible for the ongoing development and maintenance of PRINCE2 and other programmes in the Global Best Practice portfolio. Improvements include greater clarity of seven principles that guide behaviour of the project team as they perform, streamlining of the processes defined within the method, and instruction on how to tailor PRINCE2 to suit most any project’s needs. PRINCE2 has gained wide acceptance throughout Europe and Africa, and is quickly gaining popularity in North America.

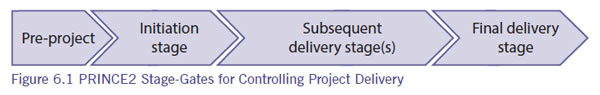

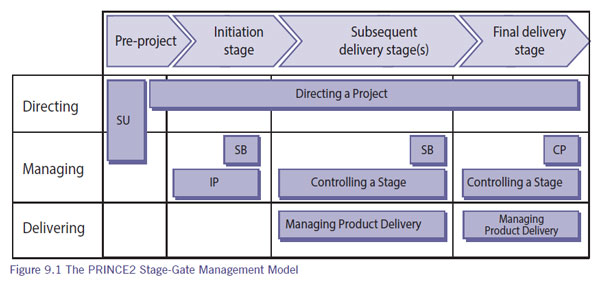

Figure 6.1 PRINCE2 Stage-Gates for Controlling Project Delivery

Principles of PRINCE2

PRINCE2 is a scalable method that you can apply to projects of varying sizes and types. The seven principles of PRINCE2 are universal in nature, they are self-validating due to the many thousands of projects that have used the method, and they empower the project management practitioner by providing a confident approach to directing a project.

Business Justification

PRINCE2 projects perform continuous justification of the investment’s objectives. Project goals are tied to the requirements within the business case to validate that the project continues to serve the needs of the organization. This guides a project team through the decision-making process throughout the life of the project, which keeps progress moving toward defined business objectives. Even compulsory projects driven by legislative mandate require justification of the alternative selected. PRINCE2 provides a governance model for guiding an organization toward an effective solution.

The continued business justification of high-risk UK Government projects is scrutinized by the Cabinet Offices major projects authorities integrated assurance approach which is consistent with the way PRINCE2 supports the development and management of the business case.

Roles and Responsibilities

PRINCE2 defines the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders at all stages and processes of the method. Participation from investment oversight board members, executive sponsors, the project board (team), the project manager, team managers, suppliers, and change control authority is clearly identified throughout the PRINCE2 method. The activities necessary for sponsoring, directing and managing the project are not left to chance.

Manage by Stages

A PRINCE2 project is managed in stages, providing control points throughout the project lifecycle. The project manager plans, controls and progresses the project using a stage-gate approach. A high-level project plan is supported by detailed stage plans. Tranches that extend beyond the horizon remain at a high level until near-term work is completed to a degree of certainty that improves likelihood of the investment achieving its goals and objectives.

Management by Exception

Deviations experienced during a PRINCE2 project are managed by exception by developing plans to identify variance from baseline. Tolerances for cost, schedule, quality, scope, risk and benefit are delegated to the project management team, providing an efficient use of resources to deliver with fewer interruptions. Decisions are made at the right level, while issues outside of tolerance are escalated only when necessary.

Product Focused

A project exists to produce output, not to perform activities. PRINCE2 focuses on defining and delivering only those products that are within the scope of the project mandate (charter). PRINCE2 uses a product breakdown structure to clarify the purpose, composition, source, type, and quality expectations of a final solution that will fulfil the business case, defined to satisfy the organization’s mission.

Learn from Experience

PRINCE2 is an experiential process. Performing regular lessons learned reviews is a key activity to success with PRINCE2. While a project is, by definition, a unique endeavour, the approach to running a project is based on repeatable themes, processes, and reusable tools. When starting a project, the project manager leverages the experiences of past projects, including reuse of approaches, performance data for benchmarking metrics and targets, defining work plans, and estimating cost and schedule milestones.

Tailored to fit, PRINCE2 can best serve and support a project regardless of size, type, organization or culture. Adapting the PRINCE2 project management approach to the situation ensures alignment of processes, tools and techniques, to best support and govern the project, while avoiding success through heroics or forced compliance to process. PRINCE2 can be right-sized to the complexity and nature of the project environment.

PRINCE2’s use of principles based project management directs the decision making process.

The PRINCE2 Stages and Process Areas

PRINCE2 is a process-based method designed to direct, manage and deliver a project to plan. The project team performs across seven defined process areas to perform the many activities for delivering the objectives of the business case. PRINCE2’s seven processes integrate with one another by following a stage-gate lifecycle framework. This provides cadence to project management activities, directing results toward pre-defined goals, and success.

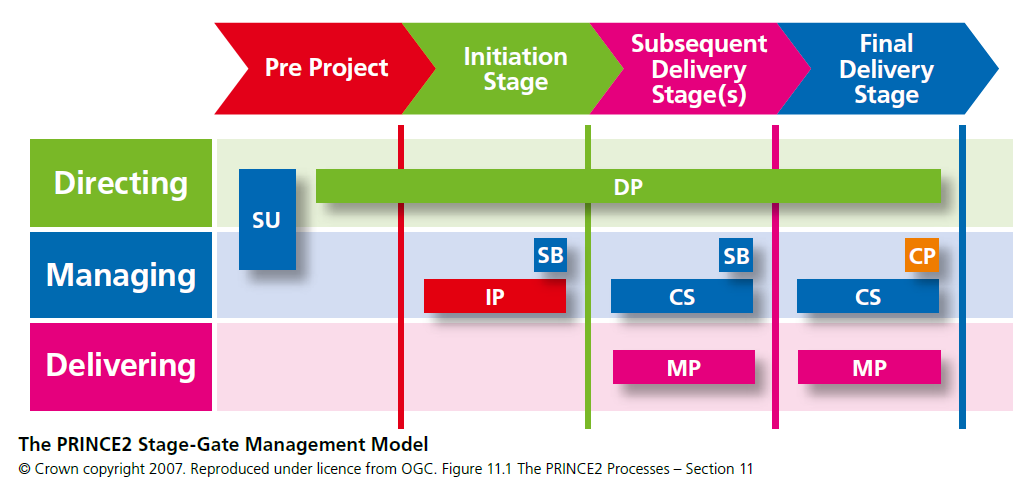

In the Pre-project Stage , the investment’s business objectives are determined by performing the activities in the Starting up a Project (SU) process. The business justifications for the investment are determined, scope is defined, and alternatives are analyzed. Through performance of the SU process, the business case is established, readying the project team to obtain authority to proceed with the investment.

In the Directing a Project (DP) process, the project is reviewed and approved by an executive review board to place the investment in the IT portfolio. DP processes manage the business case for the duration of the project lifecycle by providing senior level oversight of the investment’s progress.

The Initiation Stage continues the DP process to provide regular oversight and ad hoc direction of project activities. Upon approval to proceed with the investment, the Initiating a Project (IP) process establishes a solid foundation for achieving project success through the identification of project objectives and business benefits. IP also instructs the team to tailor project plans and invoke governance over project activities. Plans to control communications, scope, cost and schedule, risks and issues, quality, and product configuration management are all supported by PRINCE2. Techniques from other industry-popular project management guides easily integrate with the processes of PRINCE2 to monitor and control the investment.

As the Initiation Stage completes, the Managing a Stage Boundary (SB) process calls for the project manager to plan the next stage of the project. The project manager performs a business case review, updates the project plan, and reports status of the investment to the project board.

Subsequent Delivery Stages follow the Controlling a Stage (CS) process. CS provides guidance to the project manager to authorize work to the project resources, monitor and report progress, manage risks and issues, then take corrective action on variances to the plan. The project board delegates day-to-day team activities and decisions to progress the project on a stage-by-stage basis. Activities of the CS process assigns work to team members to ensure that they remain focused on delivering the products and goals of the project plan. The Managing Product (MP) Delivery process provides direction to the team members. As products are delivered, achievement to design specification is assured; the business case is reviewed for relevance to mission, and then the stage plan is completed. The SB process is again used to report and close the stage, and then subsequent Delivery Stages in the project plan repeat the CS and MP processes to continue solution fulfilment.

The Final Delivery Stage completes activities from the CS and MP processes during this last phase of the project. Then, using the Closing a Project (CP) process, the project manager performs final product acceptance testing, resolves or retires open risks and issues, reviews the investment’s performance to baseline, conducts a benefits realization review, and then recommends the project for closure to the executive investment review board.

Figure 11.1 The PRINCE2 Stage-Gate Management Model

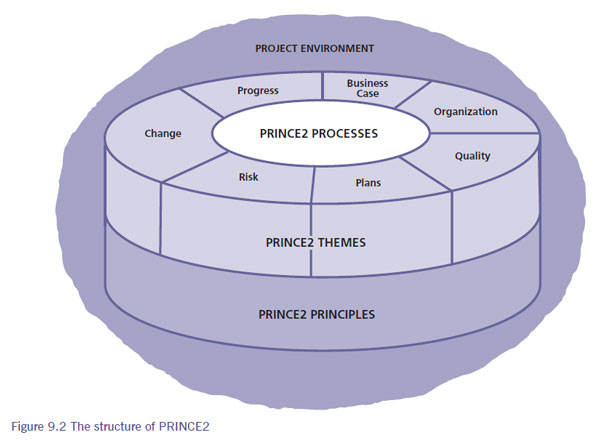

Seven Themes of PRINCE2

Project management provides little value unless it is performed with predefined intent. PRINCE2 identifies seven themes that are linked to project management. Each of the seven themes in the PRINCE2 method remains in effect during the entire project lifecycle. They are referenced according to a predetermined workflow of the method to minimize risk, and to heighten the quality of team performance and results.

Figure 9.1 The PRINCE2 Stage-Gate Management Model

Business Case

A project initiates with a need to drive transformation through an organization to fulfil new or evolving mission requirements. The business case defines why a project exists. PRINCE2 uses the business case to carry requirements through to fulfilment, while maintaining the project team’s focus on objectives.

Organization

The PRINCE2 method defines roles and responsibilities at multiple levels for directing, managing and delivering a project. A PRINCE2 project’s organization structure includes the executive oversight, project board, program sponsorship, senior users, suppliers, team managers, support staff, and project assurance personnel. Projects must often share resources with other parts of an organization. Clear identification of the extended project team reduces confusion and minimizes conflicting demands on staff as they serve multiple requirements across the business.

The criteria under which project products are verified and accepted must be established early in the project lifecycle. PRINCE2 applies the tenets of quality management at the start, where they are central to project delivery, making the final product fit for purpose. This supports achievement of desired benefits defined by the business case. A robust quality management approach reduces the likelihood of discovering product performance issues when it is too late.

A plan is not just a schedule, but also a holistic approach to governance. PRINCE2 projects follow defined and approved plans that integrate requirements, cost, schedule, quality, risk, roles, resources, and communications. Performance to plan is measured in each stage of the project. Exception Plans define deviation from baseline, which are integrated into the master plan to steer performance back toward cost, schedule and quality goals.

Risk management is a key tenet of PRINCE2. It identifies, assesses, and controls uncertainty that may affect project outcome. Risk planning starts early in the PRINCE2 method, where it is first used to mitigate project threats while initiating the project. Where other project management standards offer a model for managing risk, PRINCE2 defines the procedures, tools, and techniques for performing the risk process.

Since change is inevitable for almost any project, controlling variance to plan must be included in the management approach for maintaining the project baseline. PRINCE2 identifies an approach to change control that addresses issues that enter the project plan. PRINCE2 integrates change control of the project lifecycle phase to configuration management of the operations and maintenance phase.

The PRINCE2 method establishes mechanisms to monitor, compare, review, and report actual performance to baseline objectives. Risks are mitigated, while quality issues and problems are addressed and corrected. Upon successful completion of scheduled goals, the next stage plan is authorized, progressing the project toward completion. Numerous reporting templates are defined by PRINCE2, that include definitions of each report’s contents and use, all supported by the various processes within the method.

The Capital Planning Lifecycle of CPIC

So, let’s go back. The Clinger-Cohen Act directs agencies to manage their IT budgets by measuring the return on investment using a Select-Control-Evaluate process. CCA also directs OMB to perform oversight of agency IT spending. In response to CCA, OMB recommends that agencies apply planning, acquisition, management, and disposition lifecycle controls to their major IT projects. Simply put, each agency must have a defined plan for buying, building, operating and retiring their IT assets, and they are accountable to report project status timely and accurately.

OMB annually releases Circular A-11, a budget management directive that requires agencies to report their annual IT budget (using the Exhibit 53 form) and report progress toward goals within the business case of each major IT project (using the Exhibit 300 form). However, A-11 does not define, nor prescribe, a project management method or approach for tactically controlling and delivering the project. Circular A-11 is only a process for reporting status of the budgeted and funded investments.

OMB provides agencies additional direction in their A-11, Part 7 Supplement: Capital Programming Guide (CPG). The objective of the CPG is to show agencies how project management activities relate to IT investment management. It helps to answer the question, “Will this investment drive transformation of the business toward the agency’s mission?” The CPG defines a Capital Planning Lifecycle: a four-phased approach to IT investment management. The lifecycle identifies strategies to achieve greater service delivery and move program effectiveness toward mission goals. The CPG recommends use of risk management, earned value management, quality assurance and control, and other project management techniques. However, these are only broad brushstrokes of guidance for the project manager. The CPG does not define a project management method that must exist beneath these phases. So then, how can project managers lead their projects toward success while meeting the requirements of CPIC?

Planning and Budgeting

The CPG’s objectives of the Planning and Budgeting phase are designed to support IT investment decision-making. Alignment of strategic planning to project performance goals is determined by utilizing an agency level enterprise architecture plan. An Integrated Project Team (IPT) is established to manage the project. The IPT formulates a clear definition of system functional requirements, performs an analysis of alternatives to select the best technology solution, and establishes operating and reporting baselines. They must apply risk management techniques to reduce the chance for incurring costs associated with delivery failure, and integrate earned value management (EVM) into the contract acquisition strategies. The agency implements an executive review process to oversee investment performance and adjust the investment as the needs of the mission change over time.

Figure 10.1 The Capital Planning Lifecycle

Upon completion of a comprehensive planning effort to define an integrated proposed budget to OMB during the Select phase. Approved through the President’s budget, the initiative receives funding from Congress to become a sanctioned project ready for acquisition.

Quality and risk management are central to PRINCE2, initiated during the Starting up a Project and the Directing a Project processes of the Pre-project stage. The PRINCE2 method supports the CPIC Planning and Budgeting phase through development of the project business case. The project manager justifies the business case to ensure that the investment is planning to build the right product, is fulfilling the right business need, and that the final products will serve the organization’s mission. Once the business case is reviewed and accepted by the investment board, the project is authorized to proceed to the Initiation Stage.

PRINCE2 keeps a focus on the business case to maintain IT business value.

CPIC’s requirement for EVM necessitates a “deliverables-based” work breakdown structure to define project scope. During the PRINCE2 Initiation stage, the product breakdown structure becomes the framework for managing solution delivery. Activities of the PRINCE2 Directing a Project process establish oversight and governance to lead investment plans toward mission goals.

Figure 10.2 PRINCE2 Project Management for CPIC

Acquisition

In the Acquisition phase of the Capital Planning Lifecycle, the project team validates decisions and objectives from the Planning and Budgeting phase. The team re-examines the mission needs to affirm investment justifications in the business case to determine a “build versus buy” acquisition strategy. The IPT addresses acquisition risks, and then the project is initiated. Teams are established, contract support secured, and then development activities of the Acquisition phase commence.

An Executive Review Committee (ERC) assesses the project team’s plan for solution delivery. Following a successful procurement, the IPT operates project governance that integrates scope, cost, schedule and quality into a comprehensive project management approach. EVM is used to monitor and control planned and actual results of both government and contractor resources applied toward development activities. Once the integrated project plan is approved by the ERC, a baseline is recorded as the project plan.

The Control phase of CPIC is used to measure and improve investment performance. It instructs project managers to perform regular monitoring of product development progress, cost, schedule and performance variance, review of scope within the work breakdown structure, and assessment of risk to the investment. Change control must be applied to maintain progress toward contractual scope. Investment control and oversight is in the hands of the project manager during the Control phase. Periodic status reports are brought to the ERC.

As part of the CPIC Evaluate Phase, the IPT and ERC conduct reviews of project progress to reaffirm the acquisition decision. The ERC recommends corrective action plans where necessary to keep the project moving toward its strategic and mission goals. Solution acceptance activities of the Acquisition phase include a complete review of delivered products to affirm that they meet all requirements and objectives defined by the business case. Product quality reviews, system testing, and recording IT assets into a configuration management baseline also happen. Any product deviations discovered during solution acceptance are addressed through rework or an accepted variance to plan. Additionally, contract performance requirements are assessed to determine the contractor’s success to the cost, schedule and performance goals of the contract.

PRINCE2 uses a stage-gated approach to controlling project progress.

The PRINCE2 Controlling a Stage process continues to provide justification of Acquisition phase activities performed during Subsequent Delivery Stages. The PRINCE2 processes provide oversight of product development activities, guiding the project team as they fulfill business case requirements. The project manager conducts a review of the investment’s status to the detailed business case. Impact assessments are performed on any new or existing risks and issues. The project manager assesses progress towards cost, time, quality and benefit goals. Exception plans are introduced to address and correct variances to baselines. The project manager reviews completed work packages against defined specifications. Configuration records and stage plans are updated upon acceptance. Then, following the Managing a Stage Boundary process at the end of each Delivery Stage, the Project Board authorizes continuation to the next stage plan for the project.

Management In Use and Disposition

Once the IT system goes into production, the Evaluate Phase of CPIC prescribes that the project manager performs regular Operational Analysis (OA) to measure investment performance to predefined goals, and to determine, measure and report on the return on investment. Operational Analysis requires regular monitoring of achievement toward original business objectives. Performance goal baselines are defined, thresholds set and measurements taken to improve service over time while driving operational costs down. This continues until the asset is taken out of service (retired) during the Disposition Phase.

Management in Use involves post project operations of the IT system. To enter this phase of the Capital Planning lifecycle, the delivered IT solution must meet the defined requirements of PRINCE2’s Product Descriptions. The IT solution must also perform to the objectives of the business case. The PRINCE2 Managing Product Delivery (MP) and Closing a Project (CP) processes ensure that the project has met its requirements and is ready to enter the final phases of the Capital Planning lifecycle.

Since introduction of the Clinger-Cohen Act in 1996, agency CIOs and project managers across the US Federal government have been working to improve their IT investment management practices. The OMB A-11, Part 7 Supplement: Capital Programming Guide provides project managers guidance on the four phases of the Capital Planning Lifecycle, while oversight performed using Capital Planning and Investment Control monitors the value returned from the dollars invested in IT assets. However, without a project delivery method that supports the control and reporting requirements of CCA and CPIC, teams continue to struggle to operate projects that exhibit best practices that produce the right measures required by OMB. Best practices defined in commercially driven project management guides fail to provide an approach that connects project management methods to the IT portfolio results defined by CPIC business cases.

In contrast PRINCE2 is a scalable and proven project management method, having supported government and commercial projects for more than two decades. It supports continuous justification of the IT investment by focusing on sustainment of the business case, driving results to the organization’s mission.

PRINCE2 is scalable to the enterprise, has no cost to use and supports US government IT Investment Management controls.

The processes of PRINCE2 are scalable to suit various sized projects, ranging from only thousands of dollars to those that are tens of millions in scope. Project team performance is governed through stage-gated project plans, measuring progress of product delivery, not activities. Most important, PRINCE2 defines the roles of stakeholders, the project board and delivery teams. It establishes governance, process and controls to bring the investment from concept to fulfillment of the mission objectives, all the while improving the project management practices of the agency.

Richard Tucker is a management consultant with more than 20 years of experience in IT project management and Federal capital investment management. He provides practical knowledge and advice to US Federal agencies and departments. He is a certified PRINCE2 Practitioner and a Project Management Professional (PMP). He is an active member of the Federal CPIC Forum and contributor to numerous online communities where he shares his interest and experiences in project management methodology and tools implementation.

Richard Tucker, PMP Certified PRINCE2 Practitioner ICOR Partners, LLC www.icorpartners.com

- PRINCE2® to manage US Federal Government IT Projects

Agile Problem Solving in Government: A Case Study of The Opportunity Project

Citizen expectations, changing technologies, a mass proliferation of data, and new business processes are among the key external forces that challenge agencies to serve constituents in new ways.

At the same time, growing demands for fast response to problem solving reduce the time that agencies have for developing strategies that enable them to achieve mission objectives. In recent years, agile development has advanced in both industry and government as a method of designing software that builds functionality in rapid increments that involve both developers and users. Agile methodology is increasingly being used in non-IT efforts as well.

The Opportunity Project (TOP), a program run out of the U.S. Census Bureau at the U.S. Department of Commerce, has for several years served as a catalyst in adapting agile techniques to solve complex agency mission problems, through a process that brings together agencies, industry, and citizens. The Project’s website refers to its goal as “a process for engaging government, communities, and the technology industry to create digital tools that address our greatest challenges as a nation. This process helps to empower people with technology, make government data more accessible and user-friendly, and facilitate cross-sector collaboration to build new digital solutions with open data.”

TOP works with Federal government agencies to identify significant challenges, and then facilitates partnerships among agency leaders, industry and non-profit innovators, and citizen users to collaborate as teams in developing innovative approaches to address those challenges. The teams leverage agile techniques to build prototype technology and process solutions over a 12-14 week time frame, and then show their work to the public so that agency stakeholders from all sectors can learn from and adapt the solutions. TOP represents a unique, cross agency program that provides a model for how agencies can work with private sector partners to develop practical approaches to complex problems in an agile, iterative fashion.

In this report , Joel Gurin and Katarina Rebello outline the key elements and critical success factors involved in The Opportunity Project. Drawing insights from several TOP case studies, the authors provide lessons for other agencies, and indeed for governments at all levels, on how agile problem solving can enable public-private collaboration that helps address some of their most significant mission-focused issues.

This report continues the Center’s longstanding focus on how agile techniques can help improve government. Prior studies on this topic include A Guide to Critical Success Factors in Agile Delivery by Philipe Krutchen and Paul Gorans, which was an early assessment of the promise of agile for the public sector; and Digital Service Teams: Challenges and Recommendations for Government by Ines Mergel, which provided insights into digital services activities that leveraged agile techniques for governments in the U.S. and around the world.

Review our infographic on the report.

Read the FedScoop article, " How federal agencies can use agile development to apply open data ."

Watch our video overview:

Project governance and portfolio management in government digitalization

Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy

ISSN : 1750-6166

Article publication date: 20 June 2019

Issue publication date: 17 July 2019

This paper aims to increase the current understanding of the connection between operational level information and communication technology (ICT) projects and national level digital transformation by researching how project governance structures and practices are applied in an e-government context.

Design/methodology/approach

An elaborative qualitative study through public documentary analysis and empirical multi-case research on Finnish central government is used.

The study constructs a multi-level governance structure with three main functions and applies this in an empirical setting. The results also describe how different governance practices and processes, focusing on project portfolio management, are applied vertically across different organizational levels to connect the ICT projects with the national digitalization strategy.

Originality/value

This study integrates project governance and portfolio management knowledge into public sector digitalization, thus contributing to project management, e-government and ICT research streams by improving the current understanding on the governance of ICT projects as part of a larger-scale digitalization. This study also highlights perceived gaps between current governance practices and provides implications to managers and practitioners working in the field to address these gaps.

- Project governance

- Public sector

- ICT project

- E-government

- Digitalization

- Project portfolio management

Lappi, T.M. , Aaltonen, K. and Kujala, J. (2019), "Project governance and portfolio management in government digitalization", Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy , Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 159-196. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-11-2018-0068

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Teemu Mikael Lappi, Kirsi Aaltonen and Jaakko Kujala.

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and noncommercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Digital transformation, or digitalization, is one of the global megatrends that drive private – and public sector – organizations’ reforms through the adoption of information and communication technology (ICT) solutions to optimize operations and provide better services to customers – or citizens. Digitalization challenges institutions’ and individuals’ technological, organizational and cultural mindsets and capabilities, which can be a struggle especially in the public sector, as governments have to also cope with legal, political and public accountability-related issues while aiming towards national level digitalization, or “e-government” ( Cordella and Tempini, 2015 ). However, understanding of the impact of processes behind this reformation connecting different government levels – the strategic governance level (e.g. government, parliament), the middle executive level (e.g. ministries, agencies) and the operational (ICT project) level – is limited. Hence, more exploratory, empirical research is called for ( Snead and Wright, 2014 ). Even though Finland has been recognized internationally as one of the most advanced e-government countries ( OECD, 2015 ), the ICT development projects keep struggling also in Finland. These struggles are due to complexities and uncertainties in related issues, such as governance, organizing and technology ( Omar et al. , 2017 ; Walser, 2013 ).

Public sector digitalization, like any strategic transformation process, is executed eventually through ICT projects ( Anthopoulos and Fitsilis, 2014 ; McElroy, 1996 ), ranging from a simple agency-specific online portal to vast, multi-organizational operations management systems. In both digitalization and ICT project perspectives, it is essential to connect the projects with digitalization strategy by ensuring that the project objectives are correctly aimed and properly conducted. In other words, one must ensure that digitalization and associated ICT projects are governed appropriately ( Crawford and Helm, 2009 ; Marnewick and Labuschagne, 2011 ). One technique to govern projects is project portfolio management (PPM) – a mechanism that on the management level consolidates a group of projects into one entity to ensure the strategic contribution and fit of the projects and maximize the value of the whole portfolio ( Kaiser et al. , 2015 ; Meskendahl, 2010 ; Müller, 2009 ). Though there have been some contextual studies on PPM application in regional governments level ( Hansen and Kræmmergaard, 2013 ; Nielsen and Pedersen, 2014 ), knowledge of the topic in e-government context is still limited. Furthermore, the vertical processes between different central or state government levels, and how PPM can be applied to facilitate these processes and the governance of ICT projects, must be researched ( Jenner, 2010 ; Snead and Wright, 2014 ). The Finnish Ministry of Finance (VM) introduced PPM in 2012 to consolidate central government ICT projects, but its impact and utilization have not been analyzed properly, further empirically motivating this study.

What kind of governance structure is applied to ICT projects in public sector digitalization?

How can PPM facilitate the governance of ICT projects vertically across different levels?

This study integrates project governance and portfolio management knowledge into public sector digitalization context, thus contributing to project management, e-government and ICT research by improving understanding of the governance of ICT projects as part of a larger scale digitalization. By describing and analyzing practices related to the governance of ICT projects, this study provides implications for managers and practitioners working in the field. This paper includes a review of applicable literature on e-government, governance and PPM, followed by the research and methodology of this study and the results and discussion, with suggestions for further research.

2. Theoretical background

2.1 public sector digitalization and e-government.

Public administrations across the world have been striving towards digitalization, enabled by rapidly evolving technology and motivated by cost-efficiency and quality. This transformation mostly centers around developing and applying digital solutions to streamline internal and external processes and providing better services for citizens ( Asgarkhani, 2005 ; Fishenden and Thompson, 2013 ; Janowski, 2015 ). However, to fully use the potential of digital solutions and services, public sector strategies, structures and organizations need to reform accordingly to support renewed solutions and services. This combination has been commonly referred to as e-government ( Layne and Lee, 2001 ; Lee, 2010 ), and it is achieved through a transformation process that consists of phases from strategy formation to project execution ( Anthopoulos and Fitsilis, 2014 ; Pedersen, 2018 ). E-government has strong citizen value and collaboration perspectives, thus sharing common ground with preceding public reformation initiatives, such as the market-lead New Public Management (NPM) ( Arnaboldi et al. , 2004 ) or coordination encouraging Joined-up Government ( Cordella and Bonina, 2012 ). Though the etymology of “e-government” has somewhat suffered from inflation and been complemented with more generic and ambiguous terms, e-government is still widely used to assess the maturity of ongoing digitalization and to benchmark and provide guidelines for future efforts ( OECD, 2015 ; Rorissa et al. , 2011 ; Valdés et al. , 2011 ). The purpose of e-government or public sector digitalization is not only to provide information and services to citizens but also to create strategic connections internally and externally between government layers and agencies, enterprises and citizens. However, digitalization is challenging in many ways ( Pedersen, 2018 ) and may cause resistance, as it requires significant organizational and technological adjustments, such as architecture adoption ( Irani, 2005 ). The primary reasons for e-government struggles include ambiguous mission statements and poor project management (scope, schedule, stakeholders) causing, for example, resource overuse, longer time to market and unmet client expectations, but there are also governance-related remedies to counter these challenges ( Altameem et al. , 2006 ; Kathuria et al. , 2007 ).

2.2 Project governance

Governance is a function of management for establishing policies to oversee the work – and ensure the viability – of an organization. It is a rather ambiguous term that has been perhaps most efficiently defined by McGrath and Whitty in their review article from 2015 as follows: “the system by which an entity is directed and controlled” (p. 774).

Furthermore, from organizational perspective, governance defines the structures used by the organization, allocating rights and responsibilities within those structures, and requiring assurance that management is operating effectively and properly within the defined structures ( Too and Weaver, 2013 ). Governance takes place on different levels of an organization that are most commonly divided into three ( Loorbach, 2010 ; Kathuria et al. , 2007 ; Too and Weaver, 2013 ): the highest level – the strategic, corporate or board of directors and governance system; the middle level – tactical, business or executive and management system; and the lowest level of functional, or operational project delivery system activities. A governance structure is essentially a framework describing the functional roles and responsibilities of these levels within an organizational system, while also identifying the links between them needed for effective and efficient execution ( Müller, 2009 ).

Project governance exists within the corporate governance framework and comprises the value system, responsibilities, processes and policies that allow projects to achieve organizational objectives and foster implementation beneficial to stakeholders and the organization itself ( Müller, 2009 ; Turner, 2006 ). However, the temporary nature of project organizations separates the governance of project organization from that of a permanent organization ( Lundin et al. , 1995 ; McGrath and Whitty, 2015 ). Project governance is a multidimensional concept: it takes place in all levels within an organization by shifting the scope and objectives between ( Biesenthal and Wilden, 2014 ; Brunet, 2018 ), outside the organization and project through stakeholders and networks ( DeFillippi and Sydow, 2016 ; Ruuska et al. , 2011 ; Winch, 2014 ), and also a process with the project life cycle ( Samset and Volden, 2016 ; Sanderson, 2012 ; Stewart, 2008 ). Project governance creates a decision-making framework for project organizations to execute projects ( Joslin and Müller, 2016a ; Oakes, 2008 ). In other words, to ensure that organizations efficiently “Do the projects right.” Besides the how , another important aspect governance of projects is the what , i.e. to ensure that organizations effectively “Do the right projects” ( McGrath and Whitty, 2015 ; Müller, 2009 ). To assure that a project contributes to an organization’s strategic objectives, one must constantly align, revise and communicate long-term and short-term project goals and use motivation and control to make performances comply with goals ( Hrebiniak and Joyce, 1984 ; Srivannaboon and Milosevic, 2006 ).

2.3 Project portfolio management

PPM is a project management technique used to align and control a group of projects according to the objectives and benefits of an organization. There are three central objectives for PPM: strategic alignment (ensure strategic direction of projects); balancing across projects (in terms of strategically important parameters, such as resources or risks); and value maximization (in terms of company objectives) ( Martinsuo and Lehtonen, 2007 ; Petro and Gardiner, 2015 ). Meskendahl (2010) complements these objectives by adding the use of synergies (reduce double work and enhance utilization regarding technologies, marketing, knowledge and resources) to the list. In practice, the managerial activities related to PPM are the initial screening, evaluation and prioritization of project proposals; the concurrent evaluation and reprioritization of individual projects; and the allocation and reallocation of shared resources ( Blichfeldt and Eskerod, 2008 ; Jonas, 2010 ). These managerial practices are conducted through decisions by portfolio owners and managers at certain process gates or portfolio management board meetings and must balance a multitude of conflicting goals within an organization. PPM therefore attempts to answer project-related questions such as: “What should we take on? What should be terminated? What is possible? What is needed ( Dye and Pennypacker, 1999 )?”