The Real Issue With Instant Gratification

How quick-fix thinking creates problems in the modern world..

Posted September 14, 2019 | Reviewed by Devon Frye

The term “instant gratification” has become a fixture in the modern lexicon. Examples are everywhere. Our food, entertainment, online shopping, and even dating have been engineered to make it incredibly easy for us to obtain whatever we want in increasingly short order.

Having our desires quickly met isn’t necessarily a bad thing. But as it pertains to the spread of quick-fix solutions in the digital age, there are several reasons why certain instant gratification-fueled, impulsive behaviors may be detracting from our health and quality of life. To start, we need to appreciate how they influence our brains.

Our brains are constantly changing in response to what we do and the things we pay attention to. For example, each time we impulsively eat an unhealthy snack or buy something online, our brain pathways for those actions are reinforced and strengthened, making it easier to fall into the same patterns the next time around and harder to break the cycle.

This is worthy of consideration because many of the activities that promote instant gratification are linked to unhealthy behaviors. Over time, the ability to quickly satisfy a desire for low-quality, disease-inducing foods takes a real toll on our bodies. The unrestrained purchasing of whatever online good piques our interest creates a major burden on our credit card statement, and our constant drive to check in on social media , even while spending time with friends and family, lowers the quality of our in-person interactions.

Additionally, as we continue our quest for rewarding quick fixes, we start to experience a dopamine surge in our brains long before we actually experience any reward, and the craving associated with dopamine release hits us early, too. So now, just driving by your favorite fast-food restaurant or seeing your phone nearby is enough to induce powerful cravings, making it more challenging to break an unhealthy habit.

In the bigger picture, the more we overvalue instant gratification, the more likely we are to be distracted from longer-term, more meaningful goals . The constant checking of our social accounts or our exposure to auto-play features on streaming TV makes it difficult to maintain focus on actions that create long-term success and happiness .

In summary, over-reliance on instant gratification behaviors can create problems by changing our brains, distracting us from more meaningful pursuits, and leading to destructive financial, social, and health outcomes. And while this should not be taken to mean that we can’t enjoy the conveniences of the modern world, we need to be more conscious about the context, frequency, and consequences of this type of decision-making .

Austin Perlmutter, M.D. , is a board-certified internal medicine physician and the co-author of Brain Wash .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

What’s So Bad About Instant Gratification?

The internet is making us impatient. But is that actually such a bad thing? Our tech columnist takes a look.

The internet is making us impatient . Add that to the long list of ways that our use of technology is supposedly impoverishing the human character, making us stupid , distracted and socially disconnected .

Here’s how the argument goes: in this bold new world of instant gratification, we never have to wait for anything. Want to read the book you just heard about? Order it on your Kindle and start reading within minutes. Want to watch the movie your office-mates were gossiping about around the water cooler? Hit the sofa when you get home, and fire up Netflix. Getting lonely with your book or movie? Just launch Tinder and start swiping right until someone shows up at your door.

And that’s before we even get to the ever-expanding range of on-demand products and services that are available in big cities like New York, San Francisco, and Seattle. Thanks to services like Instacart, Amazon Prime Now, and TaskRabbit, you can get just about any product or service delivered to your door within minutes.

While all that instant gratification may be convenient, we are warned that it’s ruining a long-standing human virtue: the ability to wait. Well, it’s not waiting itself that’s a virtue; the virtue is self-control, and your ability to wait is a sign of just how much self-control you have.

The Virtues of Delayed Gratification

It all goes back to the marshmallow test , the heart of a legendary study in childhood self-control. Back in the 1960s, Stanford psychologist Walter Mischel offered 4-year-old children the chance to eat one marshmallow…or alternately, to wait and get two. A later follow-up study found that the kids who waited for TWO entire marshmallows grew up to be adults with greater self-control, as Mischel et. al describe :

those who had waited longer in this situation at 4 years of age were described more than 10 years later by their parents as adolescents who were more academically and socially competent than their peers and more able to cope with frustration and resist temptation.

From this core insight flowed an enormous body of literature describing the foundational value of self-control to life outcomes. It turns out that the ability to wait for things is a hugely important psychological resource: people who lack the self-control to wait for something they want run into real trouble on all sorts of fronts. As Angela Duckworth reports , self-control predicts…

income, savings behavior, financial security, occupational prestige, physical and mental health, substance use, and (lack of) criminal convictions, among other outcomes, in adulthood. Remarkably, the predictive power of self-control is comparable to that of either general intelligence or family socioeconomic status.

It’s this far-reaching impact of self-control that has led psychologists, educators, policy-makers, and parents to emphasize cultivating self-control at a young age. Michael Presley , for example, reviewed the effectiveness of self-verbalization (telling yourself that waiting is good), external verbalization (being told to wait) and affect cues (being told to think fun thoughts) as strategies for increasing children’s resistance to temptation. But self-control isn’t just good for kids. Abdullah J. Sultan et al. show that self-control exercises can even be effective with adults, reducing impulse buying.

Waiting for Prune Juice

If self-control is such a powerful resource—and one that is amenable to conscious development—no wonder we are leery of technologies that render it irrelevant, or worse yet, undermine our carefully practiced ability to wait for gratification. You can shower your kid (or yourself) with mindfulness training and withheld marshmallows, but as long as everything from ice cream to marijuana is just one click away, you’re fighting an uphill battle for self-control.

Buried amid the literature extolling the character-building value of deferred gratification, however, are a few nuggets that give us hope for the human spirit in the always-on, always-now internet age. Of particular interest: a 2004 study by Stephen M. Nowlis, Naomi Mandel and Deborah Brown McCabe on The Effect of a Delay between Choice and Consumption on Consumption Enjoyment .

Nowlis et al. observe that the vast majority of studies on deferred gratification assume that we are waiting for something we are actually looking forward to. But let’s be honest: not everything we get online is as deliriously enjoyable as a marshmallow. A lot of the time, what the Internet delivers is, at best, ho-hum. Your weekly re-supply of toilet paper from Amazon. That sales strategy book your boss insists everyone in the company has to read. The Gilmore Girls reboot .

And as Nowlis et al. point out, the subjective experience of a delay works totally differently when you’re waiting for something you’re not especially eager to enjoy. When people are waiting for something they really like, the delay in gratification increases their subjective enjoyment of their ultimate reward; when they’re waiting for something less intrinsically enjoyable, the delay imposes all the aggravation of waiting without the ultimate payoff.

Nowlis et al. provide a concrete example: “participants who had to wait for the chocolate enjoyed it more than those who did not have to wait” whereas “participants who had to wait to drink the prune juice liked it less than those who did not have to wait.”

When it comes to online gratification, we’re dealing with prune juice a lot more often than we’re dealing with chocolate. Sure, waiting for chocolate may ennoble the human spirit—and as Nowlis and others show, that waiting may actually increase our enjoyment of whatever we’ve been waiting for.

But a lot of the time, online technology just ensures the prompt arrival of our prune juice. We’re getting the efficiency gains of reduced wait times, without teaching our brains that good things come to those who fail to wait.

The Potential Cons of Self-Control

Nor is it obvious that instant gratification of our baser urges—if we can consider chocolate a “base urge”—is all that bad for us, anyhow. In the wake of Mischel’s research, a lively debate has sprung up over whether self-control is really such a good thing. As Alfie Kohn writes , quoting psychologist Jack Block:

It’s not just that self-control isn’t always good; it’s that a lack of self-control isn’t always bad because it may “provide the basis for spontaneity, flexibility, expressions of interpersonal warmth, openness to experience, and creative recognitions.”…What counts is the capacity to choose whether and when to persevere, to control oneself, to follow the rules rather than the simple tendency to do these things in every situation. This, rather than self-discipline or self-control, per se, is what children would benefit from developing. But such a formulation is very different from the uncritical celebration of self-discipline that we find in the field of education and throughout our culture.

The closer we look at research on the relationship between self-control and delay of gratification, the less likely it seems that the internet is eroding some core human virtue. Yes, self-control correlates with a wide range of positive outcomes, but it may come at the price of spontaneity and creativity. And it’s far from obvious that instant gratification is the enemy of self-control, anyhow: much depends on whether we’re gratifying needs or pleasures, and on whether delay is a function of self-control or simply slow delivery.

If there’s any obvious story here about our compulsion for instant gratification, it’s in our desire for quick, easy answers about the impact of the internet itself. We love causal stories about how the internet is having this or that monolithic impact on our characters—particularly if the causal story vindicates the desire to avoid learning new software and instead curl up with a hardbound, ink-on-paper book .

It’s far less satisfying to hear that the internet’s effects on our character are ambiguous, contingent, or even variable based on how we use it. Because that puts the burden back on us: the burden to make good choices about what we do online, guided by the kind of character we want to cultivate.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- Who Can Just Stop Oil?

- A Brief Guide to Birdwatching in the Age of Dinosaurs

The Alpaca Racket

NASA’s Search for Life on Mars

Recent posts.

- The Industrial Revolution and the Rise of Policing

- Colorful Lights to Cure What Ails You

- Ayahs Abroad: Colonial Nannies Cross The Empire

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

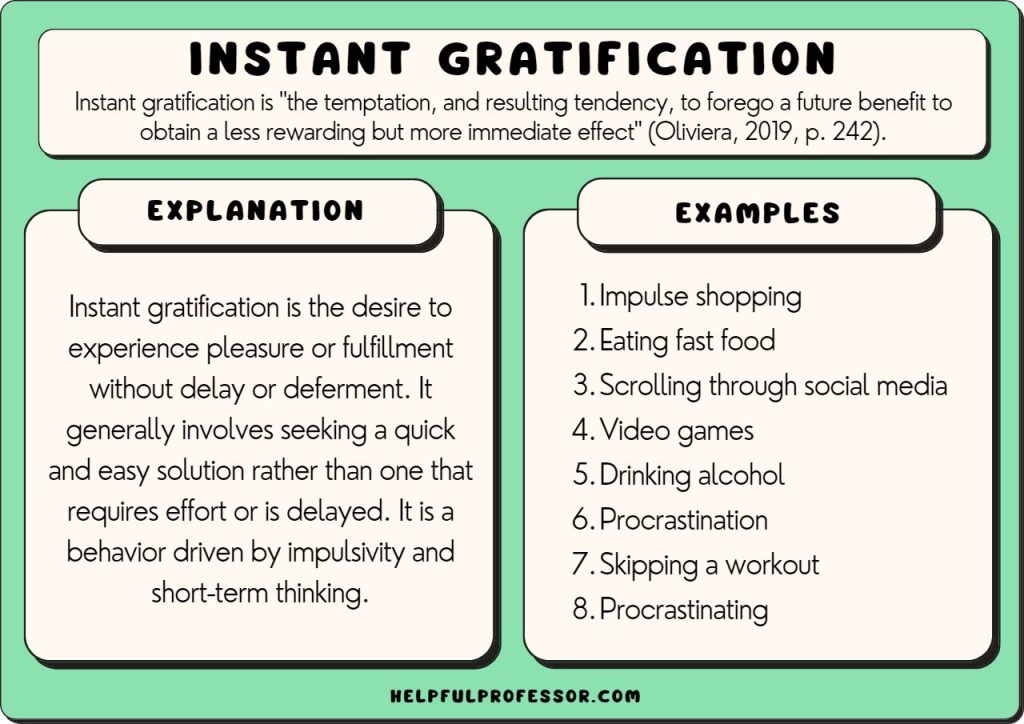

What Is Instant Gratification? (Definition & Examples)

Working on a project? Writing a paper?

Putting away that load of laundry that’s been in the dryer for two days?

If so, you’re in good company. We all find ourselves distracted from meeting more long-term goals by more enjoyable short-term activities. Each of us likely struggles with these urges to procrastinate every day—with varying degrees of success.

Why is it so hard to stay the course on our long-term projects, even when we are certain that the advantages of sticking to it will far outweigh the more immediate benefits of putting them off?

The answer is instant gratification.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains

What is the meaning of instant or immediate gratification, instant gratification theory in psychology, 6 examples of instant gratification, how to overcome an instant gratification bias, tim urban’s instant gratification monkey (the instant gratification monkey and why procrastinators procrastinate), instant gratification and its effects on relationships, instant gratification’s effect on society, “instant gratification takes too long” – 13 quotes, a take-home message, frequently asked questions.

Instant (or immediate) gratification is a term that refers to the temptation, and resulting tendency, to forego a future benefit in order to obtain a less rewarding but more immediate benefit. When you have a desire for something pleasurable—be it food, entertainment, or sex—you rarely think thoughts like, “My stomach is rumbling and I would love to have that delicious dish, but I’d rather wait another hour.”

It’s a natural human urge to want good things and to want them NOW. It has almost certainly provided an evolutionary advantage for humans and their ancestors, as life for pre-modern humans hinged on decisions made and actions taken in the immediate far more than those intended for long-term gain.

It’s all well and good to plan for the future, but actions that are taken to benefit you in the here and now are much more advantageous when you’re being stalked by a fierce predator or offered the opportunity to eat your fill in a time when starvation was a much bigger concern than obesity.

The flip side of instant gratification is delayed gratification, or the decision to put off satisfying your desire in order to gain an even better reward or benefit in the future. It’s easy to see how delayed gratification is generally the wiser behavior, but we still struggle on a daily basis with the temptation to give in to our immediate desires. Why is it so difficult to choose delayed over instant gratification?

At the heart of instant gratification is one of the most basic drives inherent in humans—the tendency to see pleasure and avoid pain. This tendency is known as the pleasure principle.

The term was first used by Sigmund Freud to describe the role of the “id,” his proposed component of the unconscious mind that is driven purely by baser instincts (Good Therapy, 2015). Although Freud’s conceptualization of the human mind has largely been relegated to the “interesting idea, but it doesn’t really pan out” category of psychological theories, the pleasure principle was one of his more enduring propositions.

It’s clear that humans are, to at least some extent, driven by the desire to experience pleasure.

You could even argue that self-defeating behavior that seems to bring no immediate benefits is in line with the pleasure principle—for example, a person who frequently starts fights with his spouse may seem to be getting no benefit from his actions, but perhaps the apology or make-up period after the fight has passed outweighs the short-term discomfort of the argument (Good Therapy, 2015).

However you slice it, the lure of short-term pleasure is a tough temptation to avoid. Psychologist Shahram Heshmat outlines 10 reasons why it is so difficult to sidestep this urge (2016):

- A desire to avoid delay: it’s uncomfortable to engage in self-denial, and all of our instincts are to seize any opportunity for pleasure as it comes.

- Uncertainty: generally, we are born with nearly infinite certainty and trust in others, but over time we learn to be less sure of the reliability of others and of our future; this uncertainty can cause us to value the less beneficial but certain-and-immediate over the more beneficial uncertain-and-long-term.

- Age: as you have likely already noted, younger people have a tendency to be more impulsive, while older people with more life experience are better able to delay and temper their urges.

- Imagination : choosing delayed gratification requires the ability to envision your desired future if you forego your current desire; if you cannot paint a vivid picture of your future, you have little motivation to plan for it.

- Cognitive capacity: higher intelligence is linked to a more forward-thinking perspective; those who are born with more innate intelligence have a tendency to see the benefits of delayed gratification and act in accordance.

- Poverty: even when we see the wisdom in delaying gratification, poverty can make the decision complicated and even more difficult; if you have an immediate, basic need that is begging to be met (e.g., food, shelter), it’s unlikely you will choose to forego that need in order to receive any future benefit.

- Impulsiveness: some of us are simply more impulsive or spontaneous than others, which makes delaying gratification that much more difficult; this trait is associated with problems like substance abuse and obesity.

- Emotion regulation: individual differences in emotion regulation also impact our tendency towards instant vs. delayed gratification ; emotional distress makes us lean towards choices that will immediately improve our mood, and those who have developed emotion regulation problems are especially at risk.

- Mood: even those with healthy emotion regulation can be led astray by their current mood; we all experience bad moods, boredom, and impatience—all of which serve to make immediate desires that much more seductive.

- Anticipation: finally, the experience of anticipation can influence our decisions to delay gratification or seek it immediately in either direction; humans generally like to anticipate positive things and dislike the anticipation of negative things, which can lead to decisions to put things off or to engage in them as quickly as possible to seek pleasure or avoid discomfort.

There are so many examples of instant gratification that it might seem easier to list examples of delayed gratification! However, humans engage in delayed gratification more often than you might think.

After all, if everyone pursued instant gratification all the time, would anyone actually make the trek into work early in the morning unless they absolutely loved their job?

Some particularly salient examples of instant gratification that you can likely spot around you include:

- The urge to indulge in a high-calorie treat instead of a snack that will contribute to good health.

- The desire to hit snooze instead of getting up early to exercise.

- The temptation to go out for drinks with your friends instead of finishing a paper or studying for an exam.

- The temptation to go out for drinks with your friends instead of getting a good night’s sleep on a work night (this is one temptation that crosses generational bounds!).

- The desire to buy a new car that will require a high-interest loan instead of waiting until you have saved enough money to buy it without taking a loan.

- The urge to spend all your time with a new beau instead of working towards your long-term goals.

You have probably noticed that at least one or two of these examples apply to you. Don’t worry—a little instant gratification now and then won’t hurt! If you find yourself constantly choosing the immediate over the long-term, however, you might be struggling with an instant gratification bias. Read on to learn how to address this bias.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

I won’t sugarcoat it (pun intended)—saying no to immediate gratification is no easy feat. If it was, we would all be trim, healthy, and have a reasonable amount of money in our savings account.

However, there are some things you can do to get better at avoiding the temptation to give in to instant gratification, including:

- Empathize with your future self. Before making a decision between instant and delayed gratification, take a moment to think about your future mental state—if you opt for instant gratification, how will the future you feel? Will she be happy you made this decision the way you did, or will she wish you had opted for delayed gratification?

- Precommitment. One of the best ways to protect yourself from the temptation of instant gratification is to make some decisions beforehand. If you can set some of your most important decisions in stone now, you will be less likely to change your mind or go through the hassle of backtracking and undoing your preparations when you come face to face with the decision.

- Break down big goals into small, manageable chunks. Big goals are fun set and can be motivating, but they can also seem overwhelming or far off. When you must decide between instant, easy gratification and delaying gratification in the attempt to meet a big, distant goal, it’s hard to stick to your long-term goa l. Breaking these big goals into smaller pieces with rewards after each step makes you more committed and more likely to make the best decisions (Mani, 2017).

When you give your future self some consideration, make important decisions ahead of time, and split your big goals up into smaller, more manageable goals, you will find it much easier to say no to immediate temptations.

If you haven’t happened upon Tim Urban’s blog Wait But Why, you’re in for a treat! He explores interesting and impactful topics at a depth that is unseen in the blogosphere.

His ability to explain complex ideas in a simple and straightforward manner is exceptional, and the drawings that accompany his blogs are nothing if not endearing.

One of his best pieces (in this author’s humble opinion) is “Why Procrastinators Procrastinate,” in which he introduces us to the Instant Gratification Monkey.

I highly recommend reading the entire piece (which you can find here ), but I’ll outline the gist of this naughty monkey if you don’t have the time to invest in Urban’s long but worthwhile blog post right now.

The Instant Gratification Monkey is a troublesome creature who lives in the brain of procrastinators and constantly grapples with the much wiser tenant of the brain (the Rational Decision-Maker) for control—and frequently wins. The problem is that this monkey is truly terrible at making decisions.

I’ll let Urban tell you why he’s so bad at decision-making:

“The fact is, the Instant Gratification Monkey is the last creature who should be in charge of decisions—he thinks only about the present, ignoring lessons from the past and disregarding the future altogether, and he concerns himself entirely with maximizing the ease and pleasure of the current moment. He doesn’t understand the Rational Decision-Maker any better than the Rational Decision-Maker understands him—why would we continue doing this jog, he thinks, when we could stop, which would feel better. Why would we practice that instrument when it’s not fun? Why would we ever use a computer for work when the internet is sitting right there waiting to be played with? He thinks humans are insane”

(Urban, 2013).

In procrastinators, the monkey is bigger, stronger, and louder than in those steadfast people who embody patience and wisdom. The monkey has only one natural enemy in the procrastinator’s brain: the Panic Monster. The Panic Monster shows up when deadlines are approaching and only immediate and extreme effort can salvage the situation.

Many Instant Gratification Monkeys run for the hills when the Panic Monster appears (although some are unaffected even then), and the procrastinator is finally able to get some things done.

While this might seem like a good thing—after all, at least something gets done—it’s a really bad strategy for the long-term. Here’s why it’s a really bad strategy:

- It’s unpleasant for the procrastinator, who could enjoy some well-deserved rewards after dedicated and consistent effort instead of guilty pleasure and last-minute panic.

- The procrastinator will eventually fall prey to underachieving and fail to meet his goals, which keeps him from reaching his full potential and is likely to result in guilt, regret, and self-esteem issues.

- The procrastinator may get the “must-do” things done, but he will rarely if ever, get the “want-to-do” things done; anything that does not have a strict deadline that sets off the Panic Monster’s alarm bells will never become a priority (Urban, 2013).

To hear more from Urban on the immediate allure and eventual disappointment of procrastination, check out his TED Talk here:

“We’re becoming impatient and lazy and we’re allowing this to shape our approach to our relationships. But successful relationships aren’t handed over on a plate, or downloaded at the click of a button, or ours in twenty-four hours for just £9.99 extra. Relationships are up there with food, water, clothing and shelter and you can’t just buy them or trade them in for an upgrade.”

It will not come as a surprise to you to learn that instant gratification can have a markedly negative impact on relationships. When we are consumed with our desire for immediate pleasure or satisfaction, we rarely make decisions that benefit our long-term future with our partner.

Whether these decisions are more innocuous, like putting off something you promised your partner you would do to binge a new show on Netflix, or more serious, like satisfying a desire to sleep with someone who is not your partner, instant gratification is not part of the standard recipe for a happy and healthy relationship.

How does instant gratification harm relationships? Laura Brown from Meet Mindful explains:

- Relationships must be respected as organic, living creations that develop and grow at their own pace; people are also on their own unique path that may result in a different pace than their partner’s. The desire to get the relationship you want right now or force a commitment in a relationship that is simply not mature enough yet is a great way to ensure that the relationship fails.

- Communicate, communicate, communicate! We all know communication is important, but the quality of communication is even more important than the quantity. It might feel good to shoot off an angry text or discuss what seems like an urgent issue right now, regardless of you and your partner’s current emotional state, but these actions can be extremely detrimental. High-quality, face-to-face communication beats out 160-character messages and taking the time to explore your feelings and reflect beats blurting out the first thing that pops into your head.

- Not every relationship SHOULD evolve, meaning that not all relationships will last ‘til-death-do-us-part, and that’s okay! It might feel extremely important to you to push your relationship to the next level—or to whatever level you desire—but forcing a relationship into a stage or a mold that doesn’t fit will only end in pain. Sometimes the best decision is to let a relationship go, even if it seems unbearably painful in the moment.

- Patience is a virtue . There’s a reason that on-the-fly marriages in Las Vegas are less likely to last than those between two long-term partners who have planned their future together: it takes time to get to know your partner, to get to know yourself, and to create a healthy, nurturing relationship. The poets and romantic comedies may push the idea of love at first sight, but it simply doesn’t exist; you must actually know someone to truly love them (although newborns have a unique tendency to capture our hearts pretty quickly). If you don’t spend the time and put in the effort to build a strong foundation, your relationship is at risk of folding at the slightest breeze (Brown, n.d.).

Aside from the impacts on our personal lives when we give in to instant gratification’s seduction, there are society-wide impacts as well. We are undoubtedly becoming a society that is accustomed to getting what we want when we want it, and there is a big reason for this trend: technology and social media.

What Role Does Technology and Social Media Play?

“Technology has eliminated the basement darkroom and the whole notion of photography as an intense labor of love for obsessives and replaced them with a sense of immediacy and instant gratification.”

Joe McNally

Although instant gratification has been a struggle for humans for a long time, it is undoubtedly harder than it used to be to delay gratification.

The biggest contributor to this increase in difficulty is modern technology and social media. When you have, essentially, the world at your fingertips, it’s extremely challenging to consciously choose delayed gratification over instant. In an age where Amazon has accustomed us to one-day delivery and Netflix and Hulu have gotten us hooked on instant streaming, it seems unthinkable to wait.

This relationship between instant gratification and technology is a two-way street: the more we are offered instant gratification through our technology, the more we come to expect it, and the more habituated we become to getting what we want right now, the more pressure there is on companies to fulfill this urge.

Emma Taubenfeld of Pace University outlines some of the effects of this interplay with salient examples:

- DVRs eliminate the need to wait through commercials to get back to your show or movie.

- Disney parks offer fast passes that allow you to skip the wait and jump to the front of the line—for a fee.

- Walmart and eBay are offering progressively faster shipping to compete with Amazon.

- Internet providers are constantly upgrading the speed of their connections to compete with other providers (2017).

Perhaps the biggest influence on our gratification habits comes from social media. Not only can we find out in an instant what all of our friends are up to or share the picture we snapped just moments ago, we can meet new people in seconds as well.

Dating apps like Tinder, Grindr, Bumble, and OkCupid offer the opportunity to connect with literally millions of people within seconds, and to filter them by dozens of specifications with a delay of only a minute or two.

While there are certainly positive outcomes from our new constantly-connected world, there are negative effects as well. It’s not a stretch to say that people are simply much less patient than they used to be.

Research from the University of Amherst found that video stream quality has a shocking impact on viewer behavior: if a video takes more than two seconds to load, would-be viewers start melting away, and each additional second of load time causes an additional 5.8% of people to give up and move on to something else (Krishnan & Sitaraman, 2013).

This is astounding when you stop to think about it. A delay of only two seconds is enough to make many of us give up on discovering something new, learning something we need to know, or even being entertained!

In a study on a similar topic, the Nielsen Norman Group found that most people stay on a web page long enough to read only about a fifth of the text that it contains (Nielsen, 2008). The average web page in the study contained 593 words, so visitors generally read only about 120 words on a typical visit.

Data from this study also showed that for 100 additional words on a page, visitors will spend only 4.4 seconds more before moving on to a new page. Depending on reading speed, that translates to around 18 words.

Think about that—when you add text to a page, you can only expect visitors to read about 18% of it! Although this certainly points to a tendency towards instant gratification (i.e., visitors find what they need and get out as soon as possible, or they give up because it takes too long), it may also be a sign that internet users are getting better at scanning pages and finding the information they are looking for.

However, with the exponential growth of false information online, even this silver lining has its own cloud—with so little time spent on gathering information, how could anyone have time to verify what they read? It’s all well and good to quickly find what you need, but how certain can you be that it is accurate when you spend mere seconds scanning the page?

As we become more dependent on the internet, and less patient with our time, it’s hard to see a future in which the prevalence of false information becomes less of a problem. If the past decade has been any indication, we can only expect more inaccuracy and less patience!

Are Millennials the Instant Gratification Generation?

“Everyone wants instant gratification: you have to have everything your parents had right away.”

Jim Flaherty

With such findings on instant gratification and technology, it’s easy to see how millennials got their reputation as the “instant gratification generation.” Millennials—the generation generally agreed to be those born in the 1980s and early 1990s—grew up with much more advanced technology than any previous generation.

They didn’t all have cell phones in their tweens, but they likely came of age with a connection to the internet that facilitated instant (or near instant, if you had dial-up) messaging.

Millennials get a lot of flak for their tendency towards instant gratification but ask a millennial about instant gratification and you might get an answer about how much longer this generation is waiting to get married, have children, buy a house, or dig out of student debt.

To be sure, millennials don’t get everything they want on demand—and are actually more patient when it comes to certain things—but they are certainly accustomed to receiving entertainment and communication with minimal delay.

Perhaps the question of whether millennials are the generation of instant gratification is the wrong question to ask; the right question might be about how the notion of instant gratification changes over time.

If you’re a member of the Baby Boomer generation, you probably agree that with the assertion about millennials and instant gratification, but take a moment to think back to your parents and grandparents’ generations: did they grow up with a telephone in the kitchen or fast, reliable, and (relatively) inexpensive automobile in the garage?

Traditionalists and earlier generations likely thought their children and grandchildren were spoiled by instant gratification as well; they could speak with anyone, nearly anywhere in the world, at the drop of a dime! The definition of the “instant gratification generation” is relative, such that whatever generation you were born into seems normal to you, while younger generations likely seem spoiled and entitled to immediate satisfaction.

Or perhaps millennials truly are spoiled and entitled to immediate satisfaction—you may want to take my millennial ideas with a grain of salt.

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Fans of the late Carrie Fisher will recognize her quote above: “Instant gratification takes too long.”

Meryl Streep had a similar quote: “Instant gratification is not soon enough.”

These humorous takes on instant gratification hold a kernel of truth to them—as we get more and more accustomed to quick satisfaction, we will only want quicker satisfaction. Avoiding the instant gratification trap requires delaying gratification, sometimes to gain even better benefits later, and sometimes just to remind us that we will survive the wait.

Here’s some other takes on instant gratification that you might find funny, insightful, or inspiring—and maybe just a few that validate the feel-good rush instant gratification can bring!

“What about getting up after five hours of sleep?’ ‘Oh, that’s morning guy’s problem. That’s not my problem—I’m night guy! I stay up as late as I want.”

Jerry Seinfeld

“In a world where people are hungry for quick fixes and sound bites, for instant gratification, there’s no patience for the long, slow rebuilding process: implementing after-school programs, hiring more community workers to act as mentors, adding more job training programs in marginalized areas.”

“As we get past our superficial material wants and instant gratification we connect to a deeper part of ourselves, as well as to others, and the universe.”

Judith Wright

“We live in a quick-fix society where we need instant gratification for everything. Too fat? Get lipo-sucked. Stringy hair? Glue on extensions. Wrinkles and lines? Head to the beauty shop for a pot of the latest miracle skin stuff. It’s all a beautiful £1 billion con foisted upon insecure women by canny cosmetic conglomerates.”

Joan Collins

“I don’t think patience is something that any of us grow up with in a large dose. It’s a world of instant gratification.”

“We’re used to the characteristics of social media—participation, connection, instant gratification—and when school doesn’t offer the same, it’s easy to tune out.”

Adora Svitak

“I think it’s kind of nice, in this day and age of instant gratification, that you have to wait for something.”

Julian Ovenden

“Working is not instantly rewarding. It’s a long process, and it’s much easier to just feed whatever dopamine cycles exist in your brain in instant gratification ways. I get it; I do.”

Greta Gerwig

“The phenomena of taking photos and sharing them isn’t new, but with Instagram being mobile, both have become cheaper and faster, producing the instant gratification of knowing how our shots look in our palms.”

“We live in a time where there’s a required instant gratification from audiences. That’s a fun challenge in terms of putting together this teaser, picking and choosing how much you’re actually giving away.”

“We are often too late with our brilliance. We are on time delay. The only instant gratification comes in the form of potato chips. The rest will find us by surprise somewhere down the road maybe as we sleep and dream of other things.”

Richard Schiff

The take-home message here is the same one you will find when you ask your parents or grandparents for advice, or the suggestion you find when clicking on nearly any link that pops up in response to Googling “instant gratification”—it’s important to learn how to put off instant gratification.

You don’t always need to say no to things that make you feel good. Giving yourself a break once in a while is important, as is treating yourself to a reward after hard work. However, these occasional treats are much more valuable when you have made delayed gratification a habit.

If that is your goal, read our post on delayed gratification exercises .

In addition, use the tips outlined earlier to build your capacity for delaying gratification—you will thank yourself later!

What do you think about this topic? Am I biased towards my generation, and missing the obvious signs that millennials are indeed the generation of instant gratification? How do you resist the urge to put off what you need to get done? Let us know in the comments section!

Thanks for reading—now get back to work!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

The opposite of instant gratification is delayed gratification, which means postponing immediate rewards to the future.

Not being able to regulate impulses can make you lazy. In particular, if constantly giving in to your impulses prevents you from taking care of your responsibilities and encourages you to slack.

Research suggests that low self-control is correlated with loneliness and depression (Özdemir et al., 2014).

One of the biggest contributors to instant gratification is social media. According to research by Donnelly and Kuss (2016), instant gratification through social media use can lead to addiction which was shown to predict depression in users of social networks.

- Brown, L. (n.d.). How instant gratification is ruining dating. Meet Mindful: Dating & Relationships. Retrieved from https://www.meetmindful.com/instant-gratification/#

- Dawd, A. M. (2017). Delay of Gratification: Predictors and Measurement Issues. Acta Psychopathologica , 3 , 1-7.

- Donnelly, E., & Kuss, D. J. (2016). Depression among users of social networking sites (SNSs): The role of SNS addiction and increased usage. Journal of Addiction and Preventive Medicine , 1 (2), 107.

- Good Therapy. (2015). Pleasure principle. GoodTherapy PsychPedia . Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/psychpedia/pleasure-principle

- Heshmat, S. (2016). 10 reasons we rush for immediate gratification. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/science-choice/201606/10-reasons-we-rush-immediate-gratification

- Hutchinson, G. T., Patock-Peckham, J. A., Cheong, J., & Nagoshi, C. T. (1998). Irrational beliefs and behavioral misregulation in the role of alcohol abuse among college students. Journal of rational-emotive and cognitive-behavior therapy , 16 , 61-74.

- Krishnan, S. S., & Sitaraman, R. K. (2013). Video stream quality impacts viewer behavior: Inferring causality using quasi-experimental designs. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, 21, 2001-2014.

- Mani, L. (2017). Hyperbolic discounting: Why you make terrible life choices. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/behavior-design/hyperbolic-discounting-aefb7acec46e

- Nielsen, J. (2008). How little do users read? Nielsen Norman Group. Retrieved from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-little-do-users-read/

- O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (2000). The economics of immediate gratification. Journal of behavioral decisión making , 13 (2), 233-250.

- Özdemir, Y., Kuzucu, Y., & Ak, Ş. (2014). Depression, loneliness and Internet addiction: How important is low self-control?. Computers in Human Behavior , 34 , 284-290.

- Patel, N. (2014). The psychology of instant gratification and how it will revolutionize your marketing approach. Entrepreneur. Retrieved from https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/235088

- Taubenfeld, E. (2017). The culture of impatience and instant gratification. Study Breaks: Culture. Retrieved from https://studybreaks.com/culture/instant-gratification/

- Urban, T. (2013). Why procrastinators procrastinate. Wait But Why. Retrieved from https://waitbutwhy.com/2013/10/why-procrastinators-procrastinate.html

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Is delayed gratification out of style? Wonder, these days more people are making trips to see psychologists or even worse psychiatrists? Like to hear from them. Enjoyed reading ur article. Thanks

Thank you for this very well written piece, and also the cross-reference to Tim Urban. His TED talk was amazing too.

Thank you for this article, it was helpful. The only thing I feel should be expanded upon is how childhood neglect and instability can make a person become addicted to instant gratification, it’s not all about laziness or spoiled behaviour. For example, my childhood was so unstable I took any pleasure I could get before it slipped away as I didn’t know how crazy the next day would be. It made me unaccustomed to say no to myself as I grew into a more stable life where I didn’t need to do that.

Very interesting article, and what you say about how it’s viewed across generations rings true — in my ears!

The example regarding instant photography, though, serves as a reminder how instant-this or instant-that is a reflection on productivity improvements. Hopefully, that benefits us and others.

Thank you for your insight and clear presentation!

Thanks for guilting me into reading this to the end 🙂 . Good article. Typo: In the quotation by Judith Wright, “As we get part our … “, “part” should be “past”.

Whoops! Thank you for bringing this to our attention — we’ve corrected this now. 🙂

– Nicole | Community Manager

Yes, I agree. It very important to reward ourselves or get pampered sometimes after a hardwork. This will surely help to get us refreshed and be ready for another day of work. Thanks for sharing this article.

Hi there, I completely agree. And we know from research that taking time for recovery through activities that are relaxing and enjoyable is really helpful for ensuring positive mood the next day at work (just in case you needed another reason to pamper yourself!) Thanks for reading. – Nicole | Community Manager

Yes, I strongly agree with what you said. Giving yourself a break once in a while is important, as is treating yourself to a reward after hard work. I think that by doing this, you can be refreshed again and work well again with a smile. Thanks for sharing this article.

Great read! I really love how things are explained! I am proud of myself finish reading this whole article . Which I think, I don’t want to belong to with this generation of “instant gratification” rather put myself with this “ delayed gratification” Yipees!

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

How to Let Go & Why It’s So Important for Wellbeing

The art of letting go has ancient Asian roots. Particularly prominent in Daoism and Buddhism, letting go entails non-attachment—that is, freeing ourselves from our desires [...]

The Scientific Validity of Manifesting: How to Support Clients

“Manifesting” is a big trend in the self-help and success industry. Because so many people actively try to practice manifesting strategies, it is important for [...]

How to Overcome Fear of Failure: Your Ultimate Guide

Although many of us may accept in theory that failure is a necessary component of all learning and growth, in practice, we struggle greatly with [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (3)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

Suggestions

The Culture of Impatience and Instant Gratification

Sometimes, I yell at my phone when the screen freezes. Just last week, I felt my heartbeat rapidly increasing and my legs shaking when the customer service representative from Amazon put me on hold for a few minutes because my package didn’t arrive in two days. It turned out that my package got lost somewhere between UPS and my apartment, so I had to wait a whole extra two days to receive my order.

Waiting four days for a delivery seems like an eternity in today’s society, as more consumers have become accustomed to the instant gratification afforded by technology.

Instant gratification is the need to experience fulfillment without any sort of delay or wait. This applies to a whole host of things including online pornography, gambling, and drug and alcohol use . When it comes to gambling in particular, there is a plethora of new online casinos on the market that are luring in an ever-growing amount of players by promising great fun and easy wins. Ultimately, you want it now, like greedy little Veruca Salt sings right up until she falls down Willy Wonka’s garbage chute. Waiting can be really hard, and when people don’t get what they want, the psychological reaction is anxiety.

To capitalize on that desire, companies are taking consumer anxiety and sprinting with it, like Absolutely , offering same-day delivery services, eliminating the need to wait for a taxi and providing the ability to stream full seasons of TV shows within seconds.

If you think about it, anything can be delivered: food, flowers, furniture, clean laundry, instant answers on Google, groceries and even people. Well, not literally people, but with apps like Tinder , Grindr and JSwipe , there are 50 million romantic candidates right at your fingertips, waiting for you to filter them by location, sexuality, religion, hobbies and how desperate they are for a partner.

Retailers too are reaping the benefits of society’s growing impatience. Walmart and eBay have challenged Amazon in a battle of which company can deliver the fastest, because consumer habits have made it clear that they will pay big bucks to avoid the wait, leading places like Disney World to profit off of passes that allow consumers to skip the line.

Instant gratification has even made its way into your living room, as DVRs have eliminated the need to watch commercials or wait for show times. Some companies, such ABC and NBC, have resorted to forcing their viewers to watch their advertisements by adding features that prevent them from fast-forwarding. In the same vein, internet providers are delivering faster connections — for a higher cost, of course — and are tempting buyers with their advertising speeds.

The patience of internet users is notoriously slow, and even minuscule differences in buffer times can have massive impacts on the success of a business. University of Massachusetts Amherst professor Ramesh Sitaraman conducted a study to establish the point at which people begin to leave a YouTube video that loads slowly.

He concluded that videos begin losing viewers at a delay of two seconds, and every one second of waiting after that marks a 5.8 percent increase in the number of people who leave. A wait of 40 seconds or more will eliminate one third of the audience.

Such demand for instantaneous feedback has repercussions beyond internet usage and purchasing habits; a society that experiences fewer and fewer waits in its daily habits will slowly possess less and less patience. In certain fields, a lack of patience is fine, but when raising children, teaching others or climbing the professional ladder, there is no way around slow, sometimes excruciating periods of growth.

Consider a recent graduate working in their first career. Their tendency to expect fast feedback will lead to disappointment when they are passed over for raises and promotions, and even a lack of positive reinforcement may lead them to struggle to stay motivated. When they don’t receive the expected fulfillment, they may feel frustrated and in extreme cases, may even seek a new job. In certain arenas accomplishments take time, and without a degree of patience, the pat on the back so many millennials are looking for will never be quick enough.

What’s more, instant gratification doesn’t grant lasting satisfaction; its entire purpose is to substitute the deep pleasure of earned enjoyment with the fleeting pleasure of instant enjoyment. People enjoy the rush of their phones beeping with a new text message, but the feeling of that pleasure disappears quickly after it comes. There isn’t anything wrong with wanting or needing objects, experiences or people within a certain amount of time, but it’s important to be able to exhibit restraint when you need to.

Instant gratification is to be expected in particular circumstances. If you order a pizza for dinner, you can expect the restaurant to deliver that order within a time frame. There is instant feedback from social media because followers can see your photos and status updates immediately. Your cell phone is always in your pocket so the connection is constant. There is no need for patience.

But letting the thrill of instant gratification deteriorate your ability to delay gratification is problematic, and will lead to serious problems on an individual and community basis. For instance, diagnoses of attention deficit disorder in children have skyrocketed in the last decade, and even the amount of adults being prescribed medication has soared. Society is losing its ability to focus.

With shorter attention spans, fewer and fewer people are choosing to read books, magazines and long articles. My grandmother is an elementary school principal, and she has begun noticing her students gravitating more toward graphic novels, most likely because of their short sentences and profusion of blank space. Even writing this article, I have consciously decided to keep the paragraphs shorter in order to make the information less overwhelming for the impatient millennial.

The good news is that more and more people are recognizing the issues of technology and are seeking ways to calm their racing minds. Last year, money spent on yoga increased to a record-breaking $16 million, and although many find it difficult to disconnect, they feel more relaxed in the end.

With the abundance of instant gratification, it’s difficult to recognize that people don’t need immediate satisfaction to feel happy. It’s important to remember how beneficial patience can be, because the best things in life are more than a click away.

- instant gratification

Emma Taubenfeld, Pace University

Arts and entertainment management, social media, 29 comments.

[…] we’re entitled to know everything immediately. And it’s a problem that may get worse over time. This recent blog post discusses the dangers of perpetuating a culture that expects immediate […]

[…] instant gratification. Globalisation and social media, amongst other things have made us an instant gratification society and the market has to keep […]

[…] [2] Emma Taubenfeld, “The Culture of Impatience and Instant Gratificaiton,” Study Breaks, March 23, 2017, https://studybreaks.com/2017/03/23/instant-gratification/ . […]

[…] is built upon appearances and accomplishments, marketing strategies and return on investments, on immediate gratification and instant communication; in a culture that is marked by all sorts of social and political […]

[…] Taubenfeld, Emma. 2017. “The Culture of Impatience and Instant Gratification.” Study Break, March 23. Accessed December 21, 2017. https://studybreaks.com/2017/03/23/instant-gratification/ . […]

[…] down to two words — instant gratification. This occurs when a human being experiences a form of immediate contentment. In other words, it is an instant feeling of fulfillment that is nearly impossible to find in a […]

[…] New York college student recently took to her blog to post about the distress she felt after learning her Amazon shipment had been delayed. The […]

[…] undoubtedly enables instant gratification. Inquiries can be answered within the time span of a few simple clicks, and skimming headlines […]

[…] Losing weight is a challenging and sometimes difficult path. Much of the problem is often connected with the fact that we live in a society that expects instant gratification. […]

[…] comparten y comunican. El mundo digital y la revolución del “ahora” han cambiado las expectativas de los usuarios que demandan instantaneidad en diferentes situaciones: atención al cliente, recompensas […]

[…] connect, share and communicate. The digital world and the “now” revolution have changed user’s expectations. They demand instantaneity in different situations: customer service, rewards, easy buying […]

[…] is a (Very Necessary) Virtue – the culture of impatience and instant gratification, in which we currently live, has us very accustomed to getting immediate results. Our culture, […]

[…] to their lack of patience, modern-day learners expect and look for swift resolutions. The moment Millennials stumble across a […]

[…] https://studybreaks.com/culture/instant-gratification/ […]

[…] for most of us when I say two-day shipping and on-demand taxis are now expected, not wanted. Our instant gratification society is conditioning us to demand immediate results, rush the process, and not let things take their […]

[…] an app. Rather than being downloaded through an app store, which often takes time in a world that thrives on instant gratification, PWAs can be saved to a home screen directly from the browser. One tap then takes you to the […]

[…] FacebookTwitterGooglePinterestRedditStumbleuponTumblr Post Views: 21,994 […]

[…] apps has also contributed to people becoming tempted to find someone new. Studies show that the craving for instant gratification can become problematic for […]

[…] Faktanya, studi ilmiah menunjukkan : kebiasaan main hape demi aneka konten yang bisa dinikmati secara instan tersebut, memang membuat benak para penggunanya juga terdorong untuk berpikir secara lebih instan. Lihat: https://studybreaks.com/culture/instant-gratification/ […]

[…] studi ilmiah menunjukkan : kebiasaan main hape demi aneka konten yang bisa dinikmati secara instan tersebut, memang membuat […]

[…] live in a world where almost any request can be fulfilled at the click of a button. Therefore, if your contact page user experience is slow or clunky, people will get frustrated […]

[…] page to load for your website is going to have a huge impact on your consumers’ actions. Nowadays, we live in an instantaneous society where people have low attention spans and prioritize time and convenience over everything else. […]

[…] as a society are so used to instantaneous. We are starving for stillness and silence in our culture. I have grown to appreciate […]

[…] The Culture of Impatience and Instant Gratification — Study Breaks […]

[…] studi ilmiah menawarkan : kebiasaan main hape demi aneka konten yang mampu dinikmati secara instan tersebut, memang […]

[…] a culture where everything is instant, we don’t feel comfortable having to wait anymore. This song teaches that it’s always worth […]

[…] Taubenfeld of Pace University writes, instant gratification doesn’t grant lasting satisfaction; its entire purpose is to substitute […]

[…] Taubenfeld, E. (2017). The culture of impatience and instant gratification. Study Breaks: Culture. Retrieved from https://studybreaks.com/culture/instant-gratification/ […]

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related Posts

Is Social Media Ruining Our Attention Span?

The Century Ride: Is 100 Miles on a Bicycle Worth It?

Don't miss.

What’s Behind Beyoncé and Taylor Swift’s Massive 2023?

By the Way, the Universe Is Always Singing

It’s Time to Talk About Filipino Food

TV’s Future Golden Boy: Percy Jackson, The Hero You’ve Been Waiting For

The Parallels Between ‘The Talented Mr. Ripley’ and ‘Saltburn’

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Magazine

Gotta Have It Now, Right Now

Author: Ronald J. Alsop

Published: Winter 2011-12

Editor’s Note: Itching to check your email? Phone pinging? Tempted to tune into the latest Twitter outrage? Our digital distractions have been dividing our attention for years. Almost a decade ago, Ronald J. Alsop considered the social implications — particularly the impact on a generation raised on instant gratification — in this Magazine Classic.

As I write this article, I am struggling to resist the urge to peek at my email. I realize that checking it would partly be an escape for me when the words don’t flow freely. But I also may be a perfect example of how technology has intensified people’s need for instant gratification.

- Related article

- Wired for Rewards

Even though I don’t know what my inbox might hold, it’s that uncertainty, along with the expectation I just might find a gratifying message, that makes me want to look. David Greenfield, founder of the Center for Internet and Technology Addiction in West Hartford, Connecticut, likens my email experience to playing a slot machine. I’m not going to feel the excitement of winning a jackpot, but subconsciously I realize that a waiting message could contain a bit of good news.

“The hit when you get a good email is like the hit of winning money,” says Greenfield. “It provides instant gratification.”

Whether on our computers or at casinos, we are indeed a culture increasingly driven by our need for instant gratification. We want — no, demand — everything right now.

Once a virtue, patience is becoming as rare as handwritten letters. Examples of the need for instant gratification abound. A friend who works at a Williams-Sonoma store was fuming one day recently when a shopper called him incompetent and demanded his name and the customer service number so she could report him. The crime: She had to wait 10 minutes to pay for her bag of pasta.

Everything from on-demand movies to scratch-off lottery tickets to instant messages has heightened people’s sense of urgency. At Walt Disney World, FastPass tickets cut your wait time for the most popular rides. Cosmetics marketers promise a facelift in a flash with products like Maybelline Instant Age Rewind. Online, instantly downloaded music purchases have put record stores out of business. And there’s no need for high school seniors to worry for long about college admission decisions: Apply “early decision” and learn your fate within a month or so.

“Things are happening so fast and information can be obtained so quickly that it does bias us toward instant gratification,” says Darrell Worthy, assistant professor of psychology at Texas A&M University. “Five or 10 years ago, I would have been more able to sit down and read an entire journal article. Now I tend to read through the abstract and figures more quickly. I’m focused on acquiring the gist of things.”

Although people save time and may even be more productive in our accelerated world, the need for instant gratification raises concerns about our work ethic, social interactions, character development, even our mental health. Some people are so impatient and so driven by instant technology that they never unplug, never slow down. They don’t take time for contemplation and relaxation, and, according to some mental health professionals, they are at greater risk for addiction to drugs, alcohol, sex, gambling, video games and the Internet.

A number of societal trends, including easy credit and unfettered consumer buying before the Great Recession, the explosive growth of legalized gambling and the technology revolution, have stoked people’s desire for instant gratification. At the same time, our business and government leaders also demonstrate little tolerance for moderation and long-term planning. Staggering federal and state budget deficits show a reckless lack of self-control, and Wall Street’s fixation with short-term results puts pressure on companies to deliver quarterly gains at any cost. That mentality, along with personal greed, accounted in large part for the financial scandals at Enron, Tyco and other companies a decade ago, and for the extreme risk-taking that brought down Lehman Brothers and the world economy in 2008. A “spend now, save later” mindset also figured strongly in the housing market collapse. While predatory lenders took advantage of unqualified prospects in the subprime mortgage crisis, the homebuyers were also to blame for their unwillingness to delay a home purchase until they truly qualified for credit. Their parents likely worked extra hours or took second jobs as they scrimped and saved to buy a home, but who can wait that long anymore? Financial experts fret about people’s failure to delay gratification and save money, especially for their retirement years.

“I feel that America has become the culture of now, the culture of present consumption,” says Stephen Utkus, a principal with the Vanguard Group’s Center for Retirement Research. “It’s a major problem that people can’t get over their present-day bias and plan for retirement. And the financial system has been an enabler with the easy access to credit.”

The U.S. personal savings rate began dropping in the mid-1980s, the era of Madonna’s “Material Girl,” and has never come close again to the double digits of the 1970s and early 1980s. Meanwhile, consumers’ debt load rose steadily during the previous decade, peaking in 2007 just before the economy cratered.

Wanting things faster is by no means a new phenomenon. The Polaroid instant camera was invented in 1948, the same year the first McDonald’s fast food restaurant opened. FedEx created its powerful international brand with the 1980s ad slogan, “When it absolutely, positively has to be there overnight.” At about the same time, the microwave oven became a kitchen staple and the plastic squeeze bottle took the anticipation out of pouring Heinz ketchup.

But the world moves ever faster, and it seems that people are becoming less and less patient. Remember the days when waiting for a dial-up connection for the Internet seemed perfectly reasonable and gave you enough time to grab a cup of coffee? Now if a high-speed connection takes more than a few seconds, people complain to their Internet provider. Can’t stand waiting a few seconds for search engine results? Now, Google Instant reveals possible matches while you’re still typing in your request. Google determined that people type slowly, taking 300 milliseconds between keystrokes but only 30 milliseconds to glance at another part of the page and scan it. If everyone around the world uses Google Instant, the company estimates, they will save more than 3.5 billion seconds a day in Internet search time.

That figure is something the millennial generation would surely appreciate. The need for speed is especially pronounced with millennials, who literally grew up on technology. They were born in the 1980s and 1990s as, first, personal computers and video games, and, later, the Internet and cell phones came to dominate our lives. My teenage son and other millennials find it hard to believe that their parents once had to sit through television commercials, search for a pay phone to make a call if their car broke down and spent hours in the library combing through books for college research papers. A college intern who worked for me recently didn’t know what I meant when I suggested he look in a telephone directory or call directory assistance when he couldn’t quickly track down a source on the Internet for an article he was writing.

Helicopter parents who hover over their millennial children have fed into the need for instant gratification by intervening to solve every problem, buying them the latest in fashion and technology, and dishing out praise for even the smallest accomplishment. Because many things have come easily to millennials, they aren’t always willing to pay their dues. Some educators and employers worry that their work ethic isn’t as strong as that of previous generations and that they are willing to cut corners and even cheat in school to get what they want now.

For their part, millennials make no excuses for their impatience. Nearly three quarters agree that they want instant gratification, according to a survey by the career center at California State University, Fullerton, and Spectrum Knowledge, a research and training firm in Cerritos, California. “It is almost an innate instinct of ours to receive instant feedback for something we do, not because we are greedy, careless or selfish but because we grew up that way,” Kristin Dziadul said in a post on Social Media Today, an online community for PR and marketing professionals. “Many people criticize our age cohort because we are this way, but consider how you would respond to things if you grew up experiencing feedback or rewards after everything you did.”

As millennials grow older, their need for instant gratification is extending well beyond the virtual world. Teachers find it harder to engage millennials in class because many want fast-paced, interactive lessons that entertain them. I once sat in the back of a classroom at the University of California at Berkeley and observed a fascinating discussion of business ethics. I was appalled that several students were checking email and surfing the Internet rather than paying attention.

Struggling to compete with YouTube and Facebook, some professors try to connect lessons with popular music and movies. Others give condensed reading assignments rather than entire books. And some schools even provide students with video iPods for online lessons.

While I applaud such creativity and dedication to trying to motivate students, I believe such approaches could shortchange them. Already many students aren’t developing the sound problem-solving skills they will need in their lives and careers. They don’t take time to do the thoughtful research that ambiguous problems — the stuff of life — require.

Millennials also expect near daily praise and feedback from their teachers and bosses, as well as rapid promotions and steady pay increases. Julie Heitzler, human resources manager at the Orlando Airport Marriott Hotel, sometimes feels she should be further along in her career at age 29. Yet when she looks around at her peers within Marriott, she finds that she is one of the few millennials at her level. “As I’m growing older and younger millennials are entering the workforce,” she says, “I am starting to see that some of the expectations, especially timing, we have for our careers can be unrealistic.”

Millennials’ reward mentality is proving to be a major challenge for employers around the world. I recently spoke at a college recruiting conference in Venice, Italy, where employers complained about their excessive expectations. “They don’t want to wait,” Federica Gianotti, a recruiting specialist for Iveco, an Italian truck and bus manufacturer, told me. “It’s always ‘What can the company give me?’ not ‘What can I give the company?’”

The Great Recession and its aftermath have certainly thwarted millennials’ desire for instant gratification in the form of a dream job. “There’s a lot of pent-up frustration,” says Jim Case, director of Cal State Fullerton’s career center. “They’re not getting jobs and a lot of postponement — marriage, buying a house — is being forced on them by the economy.”

As the millennials demonstrate so vividly, it’s technology and gadgets, from social networks to smartphones, that have really put our culture on steroids. Mobile phone owners between 18 and 24 years of age exchange an average of 109.5 text messages a day, according to the Pew Research Center, and 90 percent of 18-to-29-year-olds sleep with their phones. One new bride recently posted the happy news on her Facebook page — as she was walking out of the church. Some surveys even show that people check texts and answer cell phones while having sex because they simply can’t wait to see who’s contacting them.

While the millennials epitomize the instant gratification culture, the next generation could want things even faster. Some parents are giving babies and toddlers cell phones, iPads and other tablet devices loaded with entertaining applications that may or may not have any educational value. A new survey from Common Sense Media found that 10 percent of children under age 2 have used mobile devices, as have 39 percent of 2-to-4-year-olds and more than half of 5-to-8-year-olds. The growing number of televisions, computers and mobile devices in homes and automobiles recently prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to warn parents to limit children’s time in front of video screens so they have time for creative play and interaction with other people.

To be sure, ever-faster technology can be beneficial when it connects us to the right information in seconds. Some people maintain that instant technology not only is rewarding, but it also makes them more productive. Many pride themselves on multitasking on computers and mobile devices. But a growing body of scientific research shows that multitasking is a myth. The need for stimulation from multiple sources simultaneously plays havoc with our brains and our performance. A Stanford University research study in 2009 concluded that people who are being bombarded with several streams of electronic information do not pay attention, control their memory or switch from one job to another as well as those who complete one task at a time.

People can talk on the phone while answering emails and watching a video, but their focus is split and performance suffers. What’s more, the compulsion to check email, send texts and talk on cellphones becomes extremely dangerous when people are driving. The National Safety Council estimates that more than a quarter of all traffic crashes — over 1.6 million a year — involve cell phone calls or texting. Some lawyers even call mobile phone use the DWI of the 21st century.

The need for a quick technology fix is making people not only less focused but also less considerate. Inevitably, perhaps, instant gratification comes at the expense of civility. Although it’s impolite and annoying to others, people these days routinely check their email and send texts in the middle of dinner with friends, during business meetings or while speakers make presentations at conferences. At a performance of The Color Purple on Broadway, friends of mine had to endure texting between the woman seated next to them and her husband a few rows behind. The couple couldn’t stay focused on the play that they had paid over $200 to attend and didn’t mind disturbing those around them.

Such behavior recently prompted the Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago to ask patrons to refrain from texting until intermission. Glowing phones on vibrate may be quiet, but they can be quite distracting in a darkened theater. “When people live in the now, they want to share their experiences in real time; they can’t wait to announce that they’re blown away by the play they’re watching,” says David Rosenberg, Steppenwolf’s communications director. “But for us at the Steppenwolf, sending texts and tweets during the performance is distracting and unacceptable. Actors complain that they can see the lights from the texting, and more audience members are saying they’re distracted from the play.”

A few of those texting and tweeting theatergoers might be looking for a date after the play. That may seem like short notice, but some of the latest mobile apps promise the ultimate in speed dating — or at least hookups. While traditional online matchmaking services mean weeks of searching profiles and meeting potential mates, new mobile applications, such as Blendr and OKCupid Locals, offer instant gratification by connecting people in the blink of an eye. Through location-based technology, the apps reveal who is nearby and might be up for a drink, a date or just a sexual encounter. Such quick and easy connections could devalue relationships and lead to an obsession with sexual hookups.

Of course, the need for instant gratification underlies most addictions, whether to sex, drugs, alcohol or gambling. Now some therapists believe people suffer from Internet addiction because they’re hooked on social media, video games, and online gambling and sex sites. There is even debate among therapists over whether to add Internet addiction to the next edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Some universities, including Notre Dame, provide counseling services for Internet addiction, and specialized treatment centers offer both outpatient and residential programs to people who lack the impulse control to disconnect from computers and smartphones.