Review Essay: A Voice from the North Korean Gulag

- Carl Gershman

Select your citation format:

N orth Korea is widely and rightly viewed as an extremely repressive authoritarian country, but the actual nature of the dictatorship that rules it remains something of a mystery even to most of those who follow international politics and human rights. One reason for this is that North Korea is the world’s least accessible country to journalists and human-rights monitors, which makes it hard to verify the many horrendous abuses that defectors and prison-camp survivors report.

Hiding what is happening inside North Korea is among the tools that the xenophobic communist regime of the Kim family uses in order to maintain its power. As Kim Jong Il (1994–2011), the son of dictator Kim Il Sung (1948–94) and father of current dictator Kim Jong Un (2011–), once said: “We must envelop our environment in a dense fog to prevent our enemies from learning anything about us.” 1 This strategy of concealment has also been served by North Korea’s nuclear-weapons program and missile launches, which have diverted international attention from the country’s internal problems and generated controversies that have overshadowed concerns about human-rights violations.

The North Korean system also is hard to understand because it is so different from ordinary autocracies. North Korea and its neighbor China are both called dictatorships and are rated “Not Free” by Freedom House, but North Koreans go to extreme lengths to escape to China. Is China an open country compared to North Korea? And if China is nonetheless a dictatorship, which it is, what then is North Korea?

About the Author

Carl Gershman is the founding president of the National Endowment for Democracy .

View all work by Carl Gershman

The documentation contained in these materials has helped to spur greater international criticism of North Korea. Since 2005, the UN has annually adopted a resolution on North Korea—most recently by consensus—expressing “very serious concern” at reports of “systematic, widespread and grave violations of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights,” as well as of “the existence of a large number of prison camps and the extensive use of forced labor.” Most recently, Navanethem Pillay, the UN high commissioner for human rights, has called for the establishment of a commission of inquiry into the massive human-rights abuses reportedly taking place in North Korea.

As important as all these developments have been, nothing until now has had as great an impact on public opinion as Escape from Camp 14, 6 a short but powerful new book that tells the story of Shin Donghyuk, the only person born and raised in North Korea’s prison camps [End Page 166] to have escaped to tell what happened there—and what continues to happen every day. His is the most compelling and influential memoir yet written about the camps. The book has made Shin, whom the CBS news program 60 Minutes profiled in December 2012, the best-known North Korean defector and a voice to the world on behalf of the most oppressed and abandoned people in the most closed and isolated country on the face of the earth.

Almost Too Horrible to Believe

Shin’s personal story, including an account of how he was forced to witness his mother and brother being publicly executed for trying to escape, is almost too horrible to be believed. Its power is that it is told factually and without embellishment by a distinguished journalist, the Washington Post ’s Blaine Harden, with a well-earned reputation for professionalism and responsible reporting.

Shin was born in 1982 in sprawling Camp 14 on the Taedong River about eighty kilometers northeast of Pyongyang. He was the product of a marriage arranged by prison guards as a reward for his father’s work in the camp’s machine shop. Shin barely knew his father or older brother, and he viewed his mother, according to Harden, as “competition for survival” since he was always hungry and would often steal her food, for which she would beat him mercilessly (16). When he was old enough to go to school, he was informed that he was a prisoner because of the sins of his parents, and that he could lessen his inherent sinfulness—and improve his survival chances—by working hard, obeying the guards, and informing even on his parents.

The experiences that Shin recalls and Harden recounts expose the terrible yet routine cruelty of the camps. One victim Shin remembers was an “exceptionally pretty” six-year-old girl in his class who was beaten to death by her teacher, who had found five kernels of corn in her pocket. When he discovered the corn, he shouted, “You bitch, you stole corn? You want your hands cut off?” She had broken subsection 3 of the camp’s third rule: “Anyone who steals or conceals any foodstuffs will be shot immediately” (25).

When Shin was nine years old, he and thirty of his classmates were violently assaulted as they walked past the compound housing the camp guards’ children, who rained heavy stones down on the child prisoners, shouting “Reactionary sons of bitches are coming!” The “teacher” of the bloodied prison children ordered them back to work immediately, and when they asked what they should do with those who were still unconscious from being struck by the stones, he shouted, “Put them on your backs and carry them. All you need to do is work hard” (34).

This was Shin’s introduction to the North Korean caste system called songbun. A third of the country’s 23 million people belong to the bottom [End Page 167] caste, which is considered hostile or disloyal and has suffered the most from the camps and the famine that gripped the country in the mid-1990s. Harden quotes a former camp guard and driver who fled to China in 1994 as saying, “The theory behind the camps was to cleanse unto three generations the families of incorrect thinkers” (37). This theory of “cleansing” explains why a child would be imprisoned along with his or her parent or grandparent. It also explains why the newborn babies of female prisoners (who were preyed on sexually by the camp guards) were clubbed to death with iron rods. It was also common for such mothers to be murdered.

Shin told Harden that an assignment to work in the coal mines was the equivalent of a death sentence. Shin was fortunate to be sent to work on a pig farm and later in a garment factory, but when he dropped a sewing machine the guards cut off part of his right middle finger with a kitchen knife.

The most excruciating part of the story begins when the twelve-year-old Shin overhears a conversation between his mother and older brother about an attempted escape. Shin knew perfectly well the first rule of Camp 14: “Any witness to an attempted escape who fails to report it will be shot immediately” (193). Even if he did not inform on them, he knew that he would be tortured and probably killed as retaliation if they attempted to flee. By snitching, he might be able to save himself, and that is what he did.

As it happened, the guard to whom he snitched claimed all the credit for discovering the plot, and Shin was arrested and horribly tortured until a classmate confirmed his story. Shin spent the next seven months in a prison cell until he was taken with his father to an empty wheatfield that served as the camp’s execution ground. Shin thought that he and his father were the ones to be put to death. Then the guards sat them in front of the crowd and dragged out Shin’s mother and brother, whom the guards announced would be executed as “traitors of the people.” Shin’s mother was hanged, and three guards gunned down his brother. “It was a bloody, brain-splattered mess of a killing,” writes Harden, “a spectacle that sickened and frightened Shin” (66).

Shin spent the next ten years moving from one job to another, sharpening his survival skills, and never thinking of suicide or escape. Unlike prisoners who arrived in Camp 14 from the outside, he had no expectations and never experienced hopelessness. “He had no hope to lose,” Harden writes, “no past to mourn, no pride to defend” (73).

But this changed when Shin was paired with a new prisoner, Park Yong Chul, who had held a high-profile job before being arrested and sent to Camp 14. Shin’s job was to spy on Park. Instead, Shin became transfixed by Park’s stories, especially about food and eating, and chose not to snitch—“the first free decision of his life,” according to Harden (99). Together, Shin and his new friend plotted their escape. [End Page 168]

Their chance came when they were sent to work far up the mountain, near the camp’s fence of high-voltage barbed wire. Park reached the fence first, but was electrocuted when he tried to crawl through. Shin was able to crawl over Park’s body, which insulated him from the worst effects of the electric current, though he suffered burns more serious than at first he realized. But he had survived, and he immediately started heading in the only direction he could comprehend, which was down the other side of the mountain.

Nothing conveys the horror of life inside the camps more powerfully than Shin’s feeling of liberation in the days immediately after his escape. By any normal standard, his circumstances were desperate. He was without food or any place to sleep, ill-clothed in the bitter cold, and with legs burned and bloodied from the escape. Suddenly, however, he was wandering in a new world, with no guards in sight. As Harden writes:

It was not meaningful to him that North Korea in the dead of winter is ugly, dirty, and dark, or that it is poorer than Sudan, or that, taken as a whole, it is viewed by human rights groups as the world’s largest prison. His context had been twenty-three years in an open-air cage run by men who hanged his mother, shot his brother, crippled his father, murdered pregnant women, beat children to death, taught him to betray his family, and tortured him over a fire. He felt wonderfully free—and, as best he could determine, no one was looking for him (121).

The Beginnings of Change

Shin could not know it, but the country that he discovered outside the camp was in what the editor of Rimjin-gang, a Japan-based journal that compiles anonymous eyewitness accounts of life inside North Korea, including photographs and videos, told Harden was “a drastic state of change” (131). This change made Shin’s escape and trek toward freedom possible. Even today not fully apparent to the outside world, the change began in the 1990s with famine and the breakdown of the state system for distributing food, which led to the growth of private markets that have become essential to North Koreans’ survival. “Shin did not yet know this,” Harden writes, “but grassroots capitalism, vagabond trading, and rampant corruption were creating cracks in the police state that surrounded Camp 14” (85). Laws were ignored, police could be bribed, and military vehicles became profit-making servi-cha (service cars) that gave people mobility. Shin could find cover from the state in this world, and also food and shelter. “By keeping his mouth shut and his eyes open,” Harden writes, Shin “entered the slipstream of smuggling, trading, and petty bribery that had become North Korea’s postfamine economy” (126).

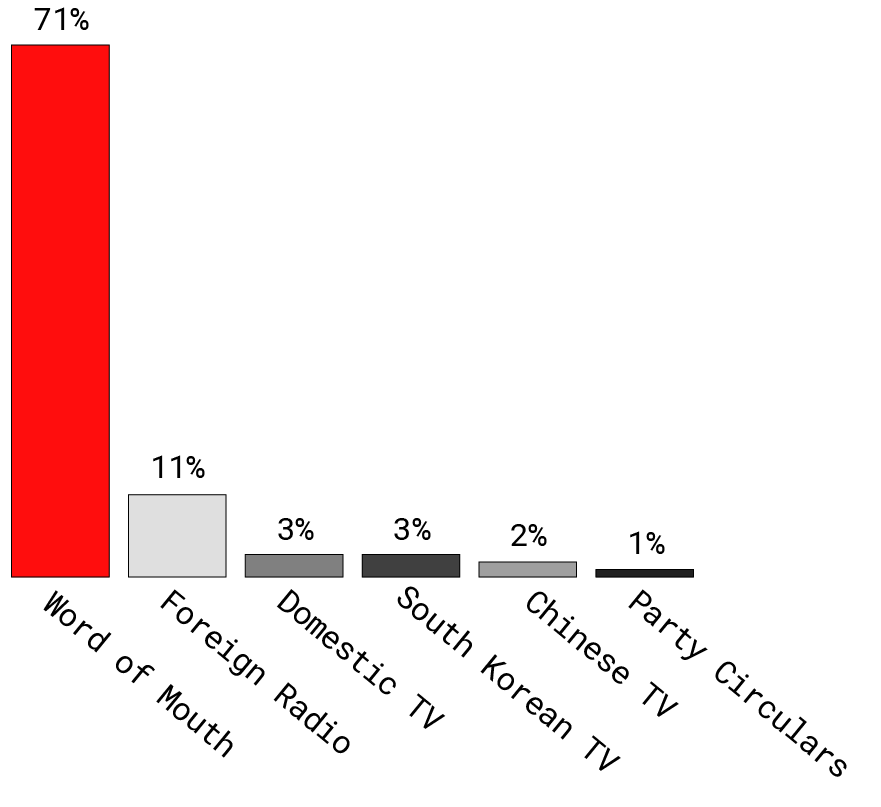

With the growth of unprecedented mobility, the borders of North [End Page 169] Korea had suddenly become more permeable. Harden writes that the catastrophic famine and the importance of Chinese foodstuffs in feeding the population forced the North Korean regime “to tolerate a porous border with China,” even to the point of allowing people “to cross back and forth into China legally” (140). In addition to allowing food to enter North Korea, the porous border has contributed to the breakdown of what scholar Andrei Lankov has called the North Korean regime’s information blockade. 7 As Harden reports, old Chinese televisions as well as video players, three-dollar radios, videotapes, compact discs, and flash drives are now regularly smuggled into the country, and people increasingly have the ability to listen to the Voice of America, Radio Free Asia, and other international broadcasts. Harden calls the two-million ethnic Koreans living in northeast China “an unsung force for cultural change inside North Korea” (148). They help to smuggle into the country hundreds of thousands of compact discs with South Korean soap operas and other programs that give North Koreans a new window on the outside world—and expose the North Korean regime’s systematic lies about it.

And then, of course, there are the stations and information networks run by the defectors and their allies in South Korea, which, according to Harden, not only send information into North Korea but “have revolutionized news coverage” of the country (152). In 2002, he notes, it tooks months for news of the reforms easing restrictions on private markets to reach the outside world. In 2009, the new independent media reported the disastrous currency reform within hours.

This raises the most important new development over the past decade, which is the resettlement in South Korea of some 25,000 North Korean defectors. Though Pyongyang and Beijing are doing everything they can to close off escape routes—including shooting evaders on sight and forcibly sending defectors back to face horrible punishment in North Korea—desperate North Koreans nonetheless continue to flee. About 2,000 were able to escape to China in 2012. This flow was down by almost a third from the year before, but it is still a substantial number considering the terrible risks involved in trying to cross the border.

These defectors are now the sole voices that speak for the victimized and silenced people inside North Korea. The defectors’ networks, NGOs, and media operations in South Korea represent a two-way communications link for people inside North Korea. This is something that never existed before, and the defectors are a growing force in bringing the terrible human-rights abuses of the Kim regime to the world’s attention. Still, as Harden notes, their voices have been relatively muted, and their reports “have barely pricked the world’s collective conscience” (12). This brings us to the importance of Shin Donghyuk.

As rights activist Suzanne Scholte told Harden, “Tibetans have the Dalai Lama . . . Burmese have Aung San Suu Kyi. . . . North Koreans have no one like that” (13). Shin does not have the stature of these leaders, [End Page 170] and Escape from Camp 14 does not have the monumental and historic significance of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago. But Shin’s story has a special power because it is such an astonishing and devastating indictment of the North Korean gulag, and because it is now reaching a much wider audience than any previous research report on the camps or North Korean prison memoir.

Shin’s prominence has placed on his shoulders the heavy responsibility of explaining the camps’ full horror to the world in hopes of rescuing the perhaps as many as 200,000 people who remain captive in them. It did not seem likely when he arrived in South Korea that he would ever be able bear such a responsibility. He endured great emotional suffering as he tried to recover from the terrible trauma that he had endured and the guilt that he felt over the deaths of his mother and brother.

According to Harden, though, Shin’s psychological recovery and moral development have been extraordinary. Escape from Camp 14 concludes with Harden observing Shin deliver a talk at a Korean Pentecostal church in Seattle. “Shin’s speech astonished me,” writes Harden:

Compared to the diffident, incoherent speaker I had seen six months earlier in Southern California, he was unrecognizable. He had harnessed his self-loathing and used it to indict the state that had poisoned his heart and killed his family. . . . When Shin was finished, when he told the congregation that one man, if he refuses to be silenced, could help free the tens of thousands who remain in North Korea’s camps, the church exploded in applause. . . . Shin had seized control of his past (190–91).

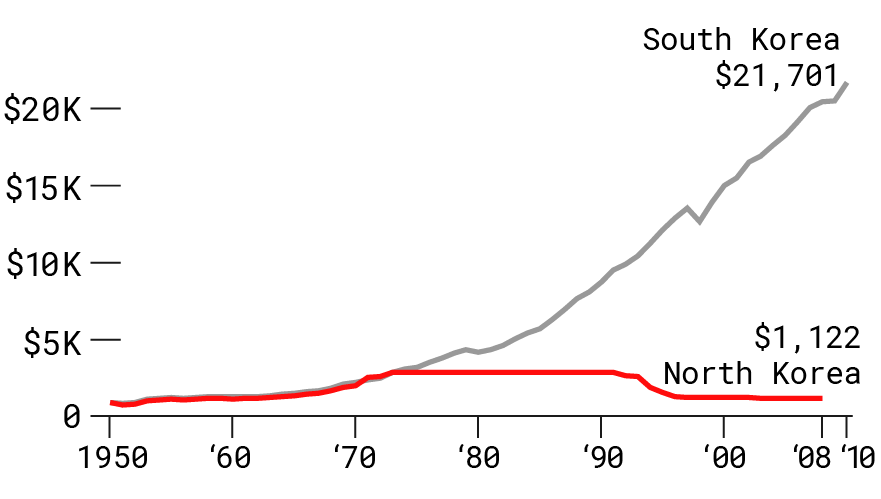

Shin’s personal development gives hope that the North Korean people have the capacity to recover from the terrible damage—which is intellectual and moral as well as physical and economic—that they have suffered from more than sixty years of life under the harshest form of totalitarianism ever devised. Harden reports that teenage defectors from North Korea are on average five inches shorter and 25 pounds lighter than their South Korean counterparts. He also notes that South Korea’s economy is 38 times larger than the North’s and that its international-trade volume is 224 times greater. It is no wonder, but no less inexcusable, that many South Koreans prefer to keep North Korea as it is rather than face the cost of rebuilding the country, which could dwarf what the West Germans had to pay to rebuild East Germany. Shin’s personal story, in addition to revealing the horrors of the camps, may also reveal a capacity for revival that now seems unimaginable to most South Koreans.

The Most Terrible Possibility

But there is a more immediate problem to be faced, and that is not just exposing the conditions in the camps but preventing the extermination of the prisoners. A brief passage toward the end of the book has the [End Page 171] most ominous implications, but Harden, inexplicably, fails to discuss or explore them. He writes that he met with Shin soon after witnessing an angry fracas between South Koreans favoring engagement and a defector trying to send balloons bearing anti-Kim leaflets north over the Demilitarized Zone between the two Koreas. Shin, Harden writes, had no interest in such street confrontations. Rather, he was busy watching old films of the Allied liberation of Nazi death camps, “which included scenes of bulldozers unearthing corpses that Adolph Hitler’s collapsing Third Reich had tried to hide.” Shin told Harden that “it is just a matter of time” before North Korea decides to destroy the camps. “I hope the United States, through pressure and persuasion,” he continued, “can convince [the North Korean government] not to murder all those people in the camps” (175).

This is more than Shin’s imagination, fueled by his terrible memories, running wild. As more defector testimonies regarding the criminal atrocities taking place in the camps become available, and as satellite photography irrefutably reveals the camps’ locations and layouts for all to see, the North Korean government’s continued denial that the camps are real is becoming a growing international scandal. 8 The failure of denial as a credible option raises the question of whether the regime will take steps to hide the camps by eliminating their inmates.

This possibility lends special urgency to a report (issued on 27 September 2012 by Radio Free Asia) that in Camp 22, one of the six active kwan-li-so concentration camps, “a large number of prisoners have starved to death since 2010” and “the North Korean authorities have been working in extreme secrecy to close the site since mid-March of last year.” The report quoted one source as saying, “Some guards from Camp 22 were left behind until the end of August to destroy all the traces of monitoring and detention facilities,” and added that the authorities are “organizing a new cooperative farm at the site” with people transferred from nearby collective farms. The website DailyNK reported the following day that “Camp 22 was totally shut down in June.”

When these reports came out, further investigation was immediately conducted by HRNK in cooperation with DigitalGlobe, a leading provider of high-resolution satellite images. Their own report confirmed that Camp 22 appeared to have been dismantled and its prisoners replaced by local farmers and laborers. Not surprisingly, researchers could not determine the fate of the prisoners, and further investigation is underway to determine if they might have been transferred to another camp. An update in December by HRNK noted that a second installation, Camp 18, may also have been shut down and emphasized that close monitoring is essential “to ensure that the North Korean regime does not attempt to erase all evidence of atrocities committed at the camps, including the surviving prisoners.”

This fuels worries that, as more becomes known about the camps, the [End Page 172] North Korean government may do exactly what Shin feared—murder the prisoners in order to eliminate the evidence of its crimes. Of course, we cannot know this for certain. But the regime has already given ample evidence that it places no value on the lives of its prisoners—Harden’s account of Shin Donghyuk’s experiences further attests to this—so the most horrific scenario cannot be ruled out.

Much more is known today about what is happening in North Korea than was known about the Nazi crimes during World War II, which the historian Walter Laqueur has called “the terrible secret.” 9 And there is much stronger advocacy today, supported by information that is universally available on the Internet. There is no excuse for inaction. The issue needs to be raised in every international forum with an urgency equal to the scale of the evil that is being confronted. The message of this searing camp memoir, and of everything else that we have come to know about the North Korean dictatorship, is that there is no greater evil in the world today.

1. Ralph Hassig and Kongdan Oh, The Hidden People of North Korea: Everyday Life in the Hermit Kingdom (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2009), 27.

2. Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights, “Report on the Visit to Prague by NKHR Delegation,” 7–13 September 2002, 4–5.

3. Václav Havel, “Time to Act on N. Korea,” Washington Post, 18 June 2004.

4. David Hawk, The Hidden Gulag: The Lives and Voices of “Those Who Are Sent to the Mountains”—Exposing Crimes Against Humanity in North Korea’s Vast Prison System, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, 2012)

5. Barbara Demick, Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea (New York: Spiegel and Grau, 2009); Cholhwan Kang and Pierre Rigoulot, The Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in the North Korean Gulag (New York: Basic, 2001).

6. Blaine Harden, Escape from Camp 14: One Man’s Remarkable Odyssey from North Korea to Freedom in the West (New York: Viking, 2012). All quotations from the book in this essay are cited by page numbers given in parentheses.

7. . Andrei Lankov, “Changing North Korea: An Information Campaign Can Beat the Regime,” Foreign Affairs 88 (November–December 2009): 99.

8. In early 2013, the North Korean gulag drew added coverage as Google began showing the outlines of some of the camps on its popular online mapping site. See Evan Ramstad, “Google Fills in North Korea Map, from Subways to Gulags,” Wall Street Journal, 30 January 2013, A8. A Google Maps satellite image of Camp 14 may be seen at https://maps.google.com/maps?ll=39.571086126.055466&spn=0.01,0.01&t=h&q=39.571086,126.055466 .

9. Walter Laqueur, The Terrible Secret: Suppression of the Truth About Hitler’s “Final Solution” (New York: Henry Holt, 1980). [End Page 173]

Further Reading

Volume 12, Issue 1

Ending One-Party Dominance: Korea, Taiwan, Mexico

- Dorothy J. Solinger

The astonishing electoral victories by opposition presidential candidates in Korea, Taiwan, and Mexico all followed a remarkably similar pattern, but it is one that may lead to difficulties for democratic…

Volume 22, Issue 2

Books in Review: Opening North Korea

A review of Witness to Transformation: Refugee Insights into North Korea by Marcus Noland and Stephan Haggard.

Volume 9, Issue 3

Voices from the North Korean Gulag

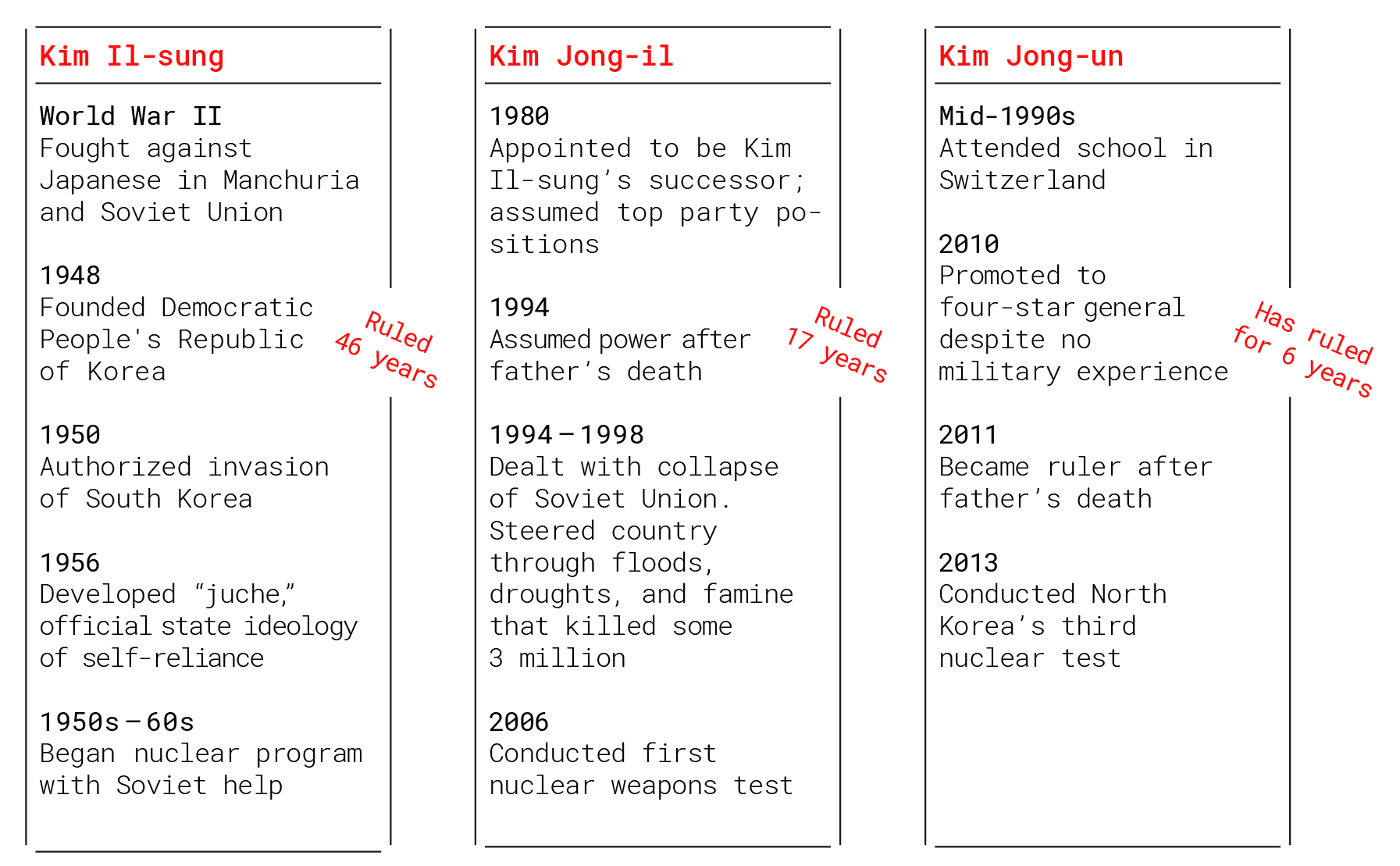

The Education of Kim Jong–un

When North Korean state media reported in December 2011 that leader Kim Jong-il had died at the age of 70 of a heart attack from “overwork,” I was a relatively new analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency. Everyone knew that Kim had heart issues—he had suffered a stroke in 2008—and that the day would probably come when his family’s history of heart disease and his smoking, drinking, and partying would catch up with him. His father and founder of the country Kim Il-sung had also died of a heart attack in 1994. Still, the death was jarring.

While North Koreans wept, fainted, and convulsed with grief, feigned or not, Kim Jong-un, the twenty-something-year-old son of Kim Jong-il, reportedly closed the country’s borders and declared a state of emergency. News of these events began to filter out to the international media through cell phones that had been smuggled in before Kim Jong-il’s death.

There had been signs before 2011 that Kim was grooming his son for the succession: he began to accompany his father on publicized inspections of military units, his birth home was designated a historical site, and he began to assume leadership titles and roles in the military, party, and security apparatus, including as a four-star general in 2010.

In response to the death, South Korea convened a National Security Council meeting as the country put its military and civil defense on high alert, Japan set up a crisis management team, and the White House issued a statement saying that it was “in close touch with our allies in South Korea and Japan.” Back in Langley, I remember being watchful for any indications of instability, as I began to develop my thinking on what was happening and where North Korea might be headed under the newly named leader. Immediately after Kim Jong-il’s death was announced, the North Korean state media made it clear that Jong-un was the successor: “At the forefront of our revolution, there is our comrade Kim Jong-un standing as the great successor … ”

What sort of person was Kim Jong-un? Would he even want the burden of being North Korea’s leader? And if so, how would he govern and conduct foreign affairs? What would be his approach to the nuclear weapons program that he inherited? Would the elites accept Kim? Or would there be instability, mass defections, a flood of refugees, bloody purges, a military coup?

Predictions about Kim’s imminent fall, overthrow, or demise were rife among North Korea and Asia watchers. Surely, someone in his mid-20s with no leadership experience would be quickly overwhelmed and usurped by his elders. There was no way North Koreans would stand for a second dynastic succession, unheard of in communism, not to mention that his youth was a critical demerit in a society that prizes the wisdom that comes with age and maturity. And if Kim Jong-un were to hold onto his position, what would happen to his country? North Korea was poor and backward, isolated, unable to feed its people, while clinging to its nuclear and missile programs for legitimacy and prestige. Under Kim Jong-un, the collapse of North Korea seemed more likely than ever.

That was then.

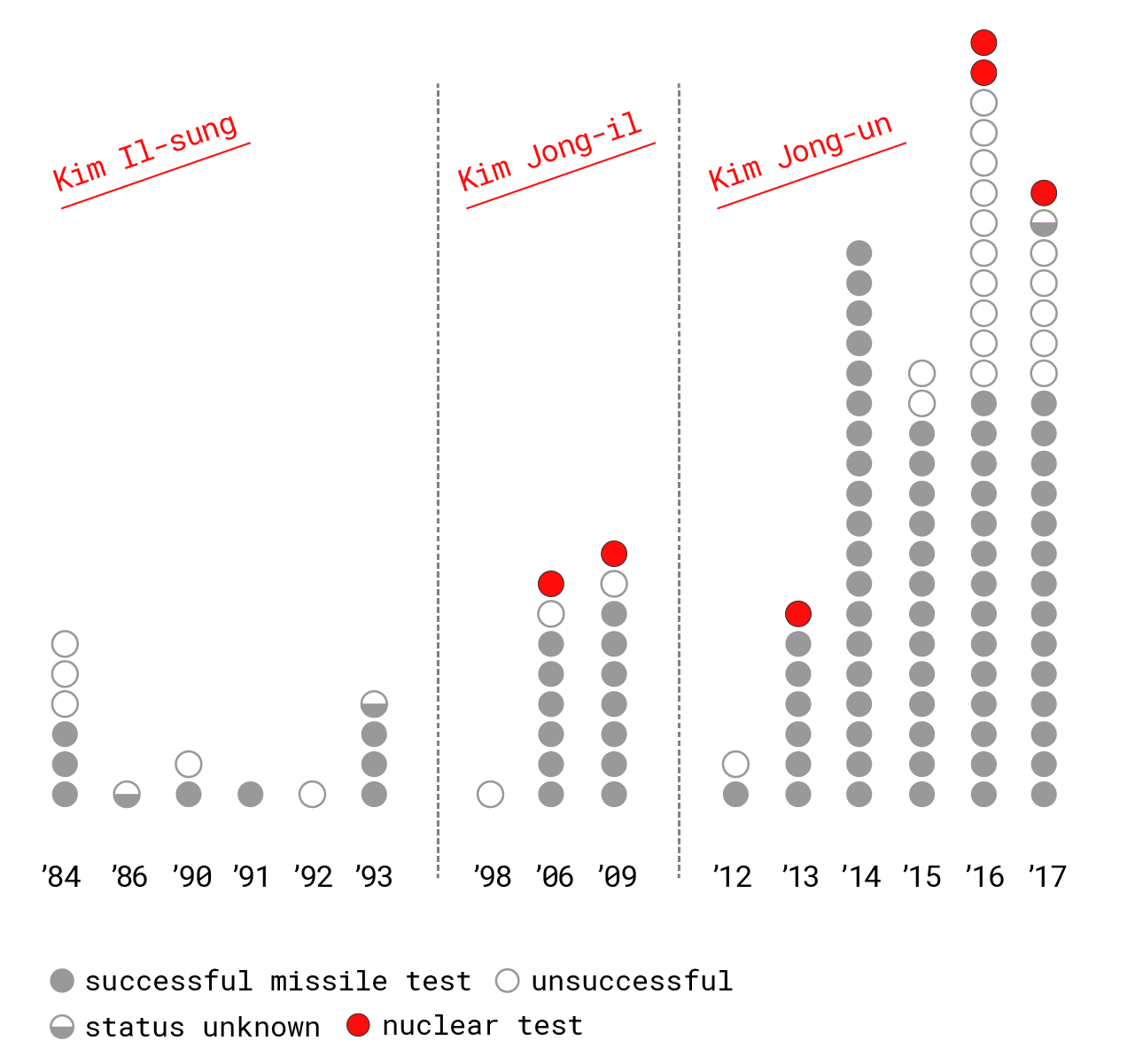

In the six years since, Kim has collected a number of honorifics, cementing his position as North Korea’s leader. Kim has carried out four of North Korea’s six nuclear tests, including the biggest one, in September 2017, with an estimated yield between 100-150 kilotons (the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan during World War II was an estimated 15 kilotons). He has also tested nearly 90 ballistic missiles, three times more than his father and grandfather combined. North Korea now has between 20 and 60 nuclear weapons and has demonstrated ICBMs that appear to be capable of hitting the continental United States. It could also be on track to have up to 100 nuclear weapons and a variety of missiles—long-range, road-mobile, and submarine-launched—that could be operational as early as 2020. Under Kim, North Korea has conducted major cyberattacks and reportedly used a chemical nerve agent to kill Kim’s half-brother at an international airport.

The last six years have also seen Kim dotting the North Korean landscape with ski resorts, water parks, and high-end restaurants to showcase the country’s modernity and prosperity to internal and external audiences. They are also meant to deliver on his promise to improve the people’s lives—as part of his byungjin policy of developing both the economy and nuclear weapons capabilities—and to attract foreign tourists.

Yet even as he is modernizing his country at a furious pace, Kim has deepened North Korea’s isolation. Having rebuffed U.S., South Korean, and Chinese attempts to reengage, he has refused to meet with any foreign head of state, and so far as is known, since becoming leader his significant foreign contacts have been limited to Kenji Fujimoto, a Japanese sushi chef whom he knew in his youth and whom he invited to Pyongyang in 2012, and Dennis Rodman, an American basketball player, who has visited North Korea five times since 2013.

Kim Jong-un is here to stay.

Of Missiles and Men

The pace of weapons testing is speeding up. Kim Jong-un has already tested nearly three times more missiles than his father and grandfather combined.

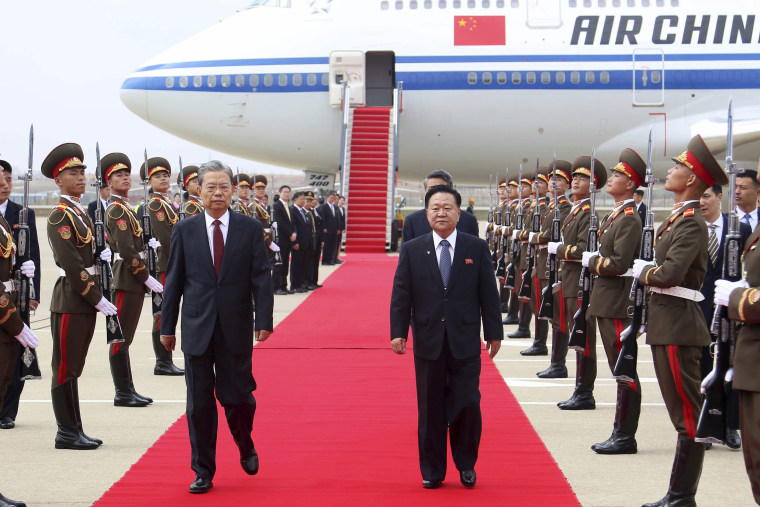

A painting of the late North Korean leaders Kim Il-sung (L) and Kim Jong-il hints at the opaqueness of the Hermit Kingdom. Jason Lee/Reuters

The ten-foot-tall baby

North Korea is what we at the CIA called “the hardest of the hard targets.” A former CIA analyst once said that trying to understand North Korea is like working on a “jigsaw puzzle when you have a mere handful of pieces and your opponent is purposely throwing pieces from other puzzles into the box.” The North Korean regime’s opaqueness, self-imposed isolation, robust counterintelligence practices, and culture of fear and paranoia provided at best fragmentary information.

Intelligence analysis is difficult, and not intuitive. The analyst has to be comfortable with ambiguity and contradictions, constantly training her mind to question assumptions, consider alternative hypotheses and scenarios, and make the call in the absence of sufficient information, often in high-stakes situations. To cultivate these habits of mind, we were required to take courses to improve our thinking. Walk into any current or former CIA analyst’s office, and you will find a slim, purple book by Richards Heuer with the title Psychology of Intelligence Analysis . This is required reading for CIA analysts. It was presented to us during our initial education as new CIA officers and often referred to in subsequent training. It still sits on my shelf at Brookings, within arm’s reach. When I happen to glance at the purple book, I am reminded about how humility is inherent in intelligence analysis—especially in studying a target like North Korea—since it forces me to confront my doubts, remind myself about how I know what I know and what I don’t know, confront my confidence level in my assessments, and evaluate how those unknowns might change my perspective.

Heuer, who worked at the CIA for 45 years in both operations and analysis, focused his book on how intelligence analysts can overcome, or at least recognize and manage, the weaknesses and biases in our thinking processes. One of his key points was that we tend to perceive what we expect to perceive, and that “patterns of expectations tell analysts, subconsciously, what to look for, what is important, and how to interpret what is seen.” The analyst’s established mindset predisposes her to think in certain ways and affects the way she incorporates new information.

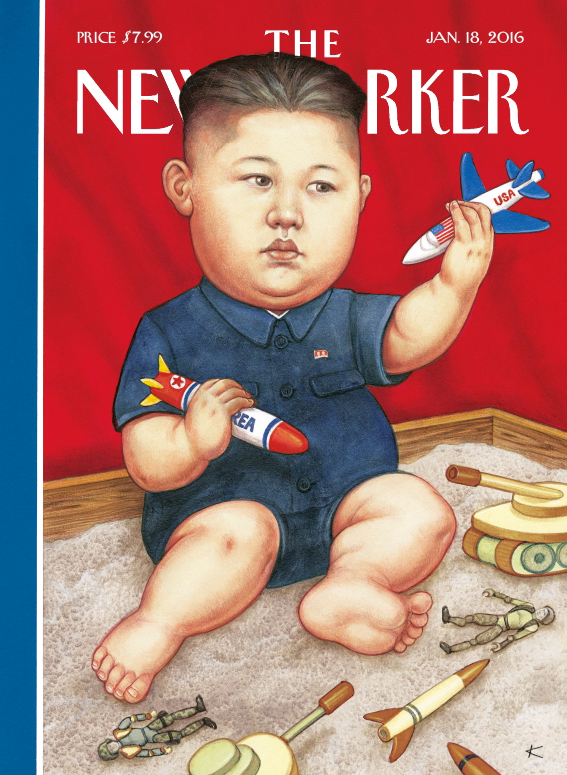

What, then, are the expectations and perceptions that we need to overcome to form an accurate assessment of Kim Jong-un and his regime? Given the over-the-top rhetoric from North Korea’s state media, Kim’s own often outrageous statements, and the hyperbolic imagery and boastful platitudes perpetuated by the ubiquitous socialist realism art, it has been only too easy to reduce Kim to caricature. That is a mistake.

When the focus is on Kim’s appearance, there’s a tendency to portray him as a cartoon figure, ridiculing his weight and youth. Kim has been called—and not just by our president—“Rocket Man,” “short and fat,” “a crazy fat boy,” and “Pyongyang’s pig boy.” A New Yorker cover from January 18, 2016, soon after North Korea’s fourth nuclear test, portrayed him as a chubby baby, playing with his “toys”: nuclear weapons, ballistic missiles, and tanks. The imagery suggests that, like a child, he is prone to tantrums and erratic behavior, unable to make rational choices, and liable to get himself and others into trouble.

However, when the focus is on the frighteningly rapid pace and advancement of North Korea’s cyber, nuclear, and conventional capabilities, Kim is portrayed as a ten-foot-tall giant with untold and unlimited power: unstoppable, undeterrable, omnipotent.

The coexistence of these two sets of overlapping perceptions—the ten-foot-tall baby—has shaped our understanding and misunderstanding of Kim and North Korea. It simultaneously underestimates and overestimates Kim’s capabilities, conflates his capabilities with his intentions, questions his rationality, or assumes his possession of a strategic purpose and the means to achieve his goals. These assumptions distort and skew our policy discussions.

A woman in Pyongyang walks past a billboard advertising North Korea’s missile prowess. The capital city is rife with stylized propaganda. David Guttenfelder/National Geographic Creative

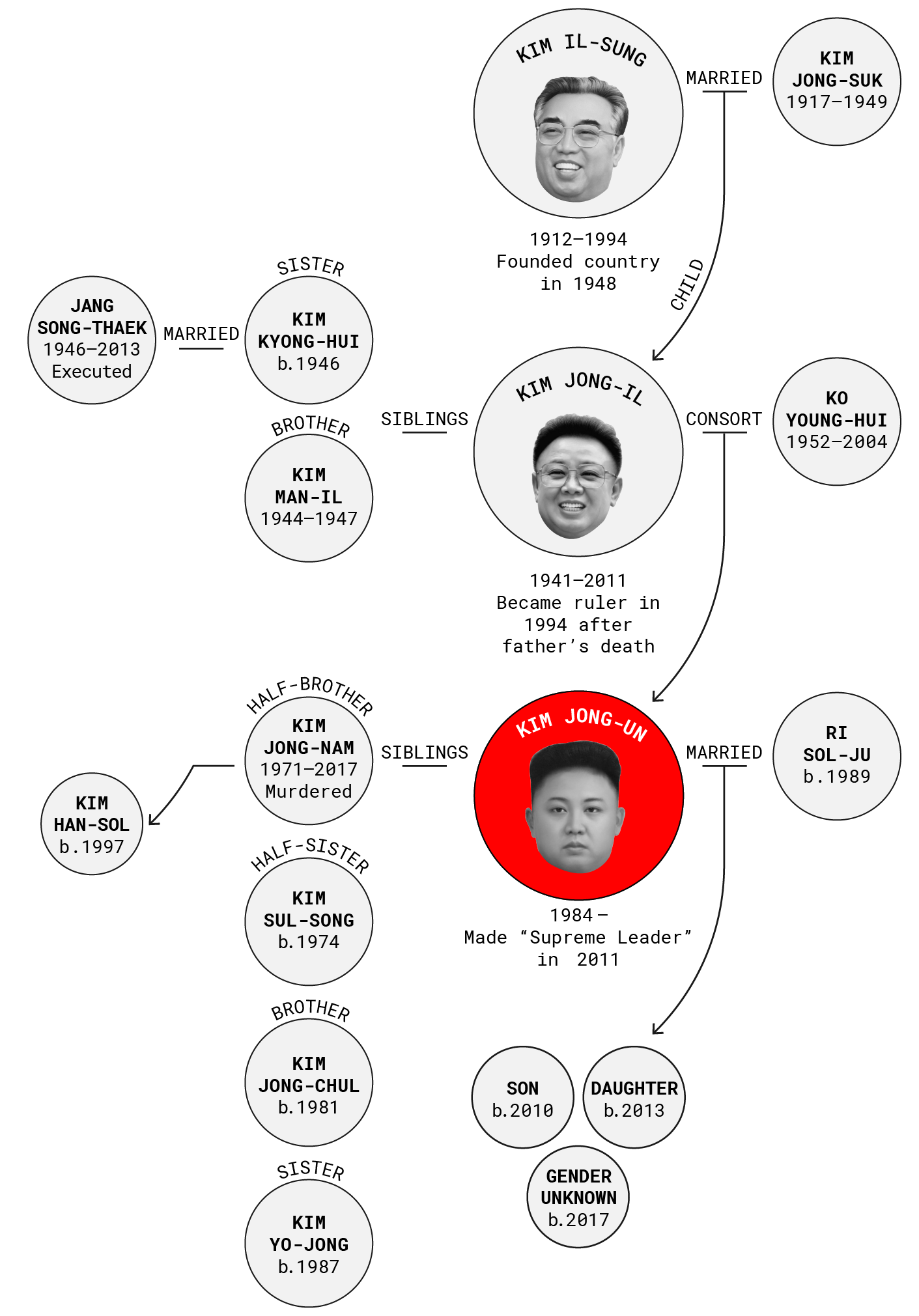

Footsteps of General Kim

If he had followed Korean custom and tradition, Kim Jong-il would have named Kim Jong-nam, not Kim Jong-un, his successor, because Jong-nam was the eldest of his three sons. But Kim Jong-il reportedly rejected Jong-nam as being unfit to lead North Korea. Why? For one, the elder Kim might have judged that Jong-nam was tainted by foreign influence. In 2001 Jong-nam had been detained in Japan with a fake passport in a failed attempt to go to Tokyo Disneyland. More seriously, it is said that he had suggested that North Korea undertake policy reform and open up to the West, enraging his father.

The second son, Jong-chul, was deemed too effeminate; one of Jong-chul’s friends recalled that “[Jong–chul] is not the type of guy who would do something to harm others. He is a nice guy who could never be a villain.” Indeed, he seems to be playing an unspecified supporting role in his younger brother’s regime.

All in the family

Four generations of Kims: A selective history*

That left Jong-un, whom the elder Kim chose to be the third Kim to lead North Korea because he was the most aggressive of his children. Kenji Fujimoto, Kim Jong-il’s former sushi chef, who visited Pyongyang at the request of Kim Jong-un, has provided some of the most fascinating firsthand observations about Jong-un and his relationship with his father. Fujimoto claims that Jong-il had chosen his youngest son to succeed him as early as 1992, citing as evidence the scene at Jong-un’s ninth birthday banquet where Jong-il instructed the band to play “Footsteps” and dedicated the song to his son: Tramp, tramp, tramp; The footsteps of our General Kim; Spreading the spirit of February [a reference to Kim Jong-il, who was born in February] ; We, the people, march forward to a bright future. Judging from the lyrics, Jong-il was expecting Kim Jong-un to lead North Korea into the future, guided by the spirit and legacy of his father.

Though Jong-il saw in his son a worthy successor to the dynasty, there are critical differences between the first two Kims and Kim Jong-un. Kim Il-sung, the country’s founder and Jong-un’s grandfather who ruled for nearly five decades until his death in 1994, was a revolutionary hero who fought Japanese imperialism, the South Korean “puppets,” and the American “jackals” in a military conflict that ended only because of an armistice.

In the next generation Kim Jong-il had to navigate through world-changing events that included the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent end of large-scale aid from Moscow, a changing relationship with the ever-suspicious Chinese who seemed to be prioritizing links with Seoul, and tense negotiations with the United States on North Korea’s burgeoning nuclear program. And let’s not forget the famine and the drought of the 1990s, or the tightening noose of sanctions and international ostracism.

In contrast with his battle-hardened elders, Kim Jong-un grew up in a cocoon of indulgence and privilege.

During the 1990s famine, in which as many as 2–3 million North Koreans died as a result of starvation and hunger-related illnesses, Kim was in Switzerland. His childhood was marked by luxury and leisure: vast estates with horses, swimming pools, bowling alleys, summers at the family’s private resort, luxury vehicles adapted so that he could drive when he was 7 years old. For Kim, skiing in the Swiss Alps and swimming in the French Riviera must have seemed part of his birthright. Kim had a temper, hated to lose, and loved Hollywood movies and basketball player Michael Jordan.

Fujimoto, the sushi chef, has described Jong-un’s mother as not very strict about education and says that he was never forced to study. His friend and classmate in Switzerland said of Kim: “We weren’t the dimmest kids in the class but neither were we the cleverest. We were always in the second tier … The teachers would see him struggling ashamedly and then move on. They left him in peace.” Jong-un was apparently unbothered by his less-than stellar scores; as his classmate noted, “He left without getting any exam results at all. He was much more interested in football and basketball than lessons.”

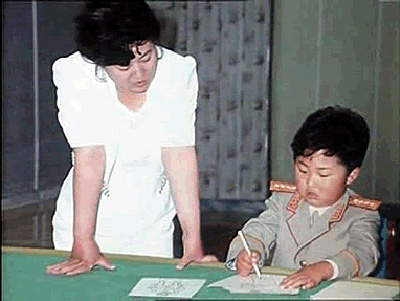

Despite his apparent lack of seriousness, Jong-un seems to have known from early on that, as his father’s chosen successor, he was destined to lead. His strong self-esteem and confidence were cultivated beginning when he was very young. And the Kim family dynasty—a totalitarian regime—carefully created a cult of personality around the young boy, as it had done with his father and grandfather before him, reinforcing it through fear and intimidation and shows of force. Kim’s aunt said that at his eighth birthday party, he wore a general’s uniform with stars, and the real generals with real stars bowed to him and paid their respects to the boy. According to Fujimoto, Kim carried a Colt .45 pistol when he was 11 years old and dressed in miniature army uniforms.

As Mark Bowden wrote in a 2015 Vanity Fair profile , “At age five, we are all the center of the universe. Everything—our parents, family, home, neighborhood, school, country—revolves around us. For most people, what follows is a long process of dethronement, as His Majesty the Child confronts the ever more obvious and humbling truth. Not so for Kim. His world at age 5 has turned out to be his world at age 30 … Everyone does exist to serve him.”

So, while small armies of teachers, tutors, cooks, assigned playmates, bodyguards, relatives, and chauffeurs developed Kim’s sense of entitlement and shielded him from the realities of North Korea and the world beyond when he was a child, the concept of juche (self-reliance) and suryong (Supreme Leader) would provide the ideological and existential justification for his rule when it came time for him to assume the mantle of leadership. The regime’s propaganda machine constructed and promoted the mythology, extolling his wisdom, his martial prowess, and his near supernatural capabilities, an example of which was his supposed ability to drive at age three.

In October 2006, when Kim Jong-un was in his early twenties and two months away from his graduation from Kim Il-Sung Military University (which he had reportedly attended since 2002), North Korea conducted its first nuclear test, providing the Kim dynasty with yet another layer of protection, further steeping the nation in the Kim family mythology of supreme power, and further warping the young Jong-un’s sense of reality and expectations. That nuclear test, and his grandfather’s and father’s commitment to nuclear weapons, would also, however, narrow his choices once he took power, boxing him into the conviction that the fate of the nation and its 25 million people rested on his carrying forward this legacy. The young Kim and his classmates at the military university—the future military elite—no doubt celebrated that nuclear milestone, which probably also fortified their optimism about their country’s nuclear future and reinforced their belief in their role as the defenders of that future.

The Gulag Peninsula

An estimated 200,000 North Koreans are held in some 30 prison camps across the country.

Once Kim did become the leader, and as such the personification of North Korea’s national interest, he was endowed with all the tools of political repression that had consolidated his father’s and grandfather’s supremacy. These tools allowed him to validate his persecution of any real or suspected dissenters, and to maintain a horrific network of prison camps in which torture, rape, beatings, and a variety of other human rights violations continue to take place to this day, as they have done for many decades. As the U.N. Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea concluded in 2014, North Korea has committed “systematic, widespread and gross human rights violations,” and under its banner of “Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism,” the regime “seeks to dominate every aspect of its citizens’ lives and terrorizes them from within.”

A North Korean soldier in Pyongyang stands vigil in Kim Il-sung Square. The markings on the street are for military parades—a hallmark of dictatorships the world over. David Guttenfelder/National Geographic Creative

A 21st–century dictatorship

As a scholar of U.S. history before I became an intelligence analyst, I couldn’t help but think about Andrew Carnegie’s famous statement about the third generation in America as Kim 3.0 took the reins of power in North Korea. “There are but three generations from shirt sleeves to shirt sleeves.” Or in other words, the first generation makes the money, the second generation maintains it, and the third squanders it. Kim Jong-un seems determined to avoid that fate.

Kim has adopted the mantle of the mythical, godlike leadership role that grandfather and country founder Kim Il-sung and his father Kim Jong-il held and continue to hold in their death. But he seems determined to chart his own path. In short, this is not your grandfather’s dictatorship.

Kim is however harnessing the nostalgia for his grandfather’s era, before the 1990s famine and the collapse of the Soviet Union and the resulting termination of aid. With his uncanny likeness to his grandfather in both appearance and demeanor, he has skillfully exploited the country’s adulation of its founder. Just a few months after he became the leader of North Korea, on the 100th anniversary of his grandfather’s birth, Kim delivered his first public address. As he invoked his grandfather’s legacy in the lengthy, 20-minute speech, he also affirmed his father’s “military first” policy, proclaiming that “the days are gone forever when our enemies could blackmail us with nuclear bombs.” Yet even while endorsing his father’s policy, he was making a remarkable departure from his father’s practice, for this was the first time that North Koreans had heard their leader’s voice in a public speech since Kim Il-sung’s days: Kim Jong-il shunned speaking in public during his almost 20 years of rule.

While basking in the nostalgia for his grandfather, Kim Jong-un is also determined to be seen as a “modern” leader of a “modern North Korea.” His charting of his own path can be seen in another departure from his father’s public persona. Kim has allowed himself to seem more transparent and accessible than his father. He appears in public with his pretty and fashionable young wife, Ri Sol-ju (with whom he has at least one child, and possibly three). He hugs, holds hands, and links arms with men, women, and children, seeming comfortable with both young and old. That transparency has been extended to the government. When one of its satellite launches failed in April 2012, the regime admitted the failure publicly, the first time it had ever done so.

During his frequent public appearances, Jong-un can be seen giving guidance at various economic, military, and social and cultural venues, as his father and grandfather did, but he is also shown pulling weeds, riding roller coasters, navigating a tank, and galloping on a horse. He is comfortable with technology in the form of cell phones and laptops, and is also portrayed speaking earnestly with nuclear scientists and overseeing scores of missile tests.

Kim appears to want to reinforce the impression that he is young, vigorous, on the move—qualities that he attributes to his country as well. Speaking directly to the people in April 2012 in that first public speech he gave as their leader, he confidently promised that North Koreans would no longer have to tighten their belts. Later he announced his byungjin policy: that North Korea can have both its nuclear weapons and prosperity. Animated by the optimism of one whose privilege made him believe anything was possible, he has prioritized both these issues and personally taken ownership of them—all part of creating and nurturing his brand.

The images that the regime chooses to disseminate and weave into Kim’s hagiography say a lot about how Kim envisions North Korea’s future and his place in it. The carefully curated public appearances of Kim’s wife, Ri Sol-ju, provide the regime with a “softer” side, a thin veneer of style and good humor to mask the brutality, starvation, and deprivation endured by the people, while reports about the existence of possibly multiple children hint at Kim and his wife’s fecundity and the potential for the birth of another male heir to the Kim family dynasty (although I wouldn’t rule out the possibility for Kim to choose a daughter to lead North Korea, given his “modern” tendencies). For the toiling masses as well as for the elite, Ri, the glamorous and devoted wife, is an aspirational figure.

To outside scholars, Ri’s public appearances offer something else—a glimpse of an emerging material and consumer culture, which Kim seems to be actively promoting. Even as tension with the United States went into overdrive after a sixth nuclear test and the launch of numerous ballistic missiles during the summer and fall of 2017, state media showed Kim and his wife touring a North Korean cosmetics factory. He reportedly urged the industry to be “world competitive,” praised the factory for helping women realize their dream of being beautiful, and offered his own comments on the packaging.

In addition to the beauty industry, the vision of economic development that Kim has been promoting includes ski resorts, a riding club, skate parks, amusement parks, a new airport, and a dolphinarium, perhaps because he considers these as markers of a “modern” state. Or in his naiveté he may simply want his people to enjoy the things to which he has had privileged access. (Fujimoto claimed that when Kim was 18, he ruminated to the sushi chef, “We are here, playing basketball, riding horses, riding Jet Skis, having fun together. But what of the lives of the average people?”)

A Tale Of Two Koreas

GDP Per Capita, USD

Kim may also be using the imagery of these amenities as a corrective, a way of undermining the dominant external narrative of a decaying, starving, economically hobbled North Korea. Perhaps even more importantly, he may be deploying these signs of affluence to craft an internal narrative about North Korea’s material well-being at a time when his people are being exposed to more and more information about South Korea’s wealth. DVDs and flash drives of South Korea’s soap operas and K-pop music have been smuggled into the country in ever greater numbers, infiltrating the previously sealed mental and cultural landscape of North Koreans and presenting a potential danger to the regime. As North Korean defector Thae Yong-ho recently said in testimony to the U.S. Congress, this access to information about how the world outside North Korea lives is beginning to have a real impact: “While on the surface the Kim Jong-un regime seems to have consolidated its power through [a] reign of terror … there are great and unexpected changes taking place within North Korea.”

Of course, Kim still has enormous power and, like his father and grandfather, the willingness to hold onto it through extreme brutality. He maintains control through purges and executions—punishments and acts of revenge he appears to inflict with relish. In the six years of his reign the regime has purged, demoted, “reeducated,” and shuffled scores of senior leaders.

There was also the spectacularly shocking public humiliation of Kim’s uncle Jang Song-thaek in 2013, who was labeled “human scum” and “worse than a dog” and then reportedly executed by an anti-aircraft gun for allegedly undermining the “unitary leadership of the party” and “anti-party and counterrevolutionary factional acts.” Kim probably also ordered the deadly attack by the application of a VX nerve agent—one of the most toxic of the chemical warfare agents—against Jong-nam, his half-brother and erstwhile competitor for the position of supreme leader of North Korea. Captured on camera, the attack occurred in Malaysia’s airport, and images of Jong-nam’s gruesome death were circulated around the world.

Kim has made it clear that he will not tolerate any potential challengers. And his rule through terror and repression—against the backdrop of that pastel wonderland of waterparks—means that the terrorized and repressed will continue to feed Kim’s illusions and expectations, his grandiose visions of himself and North Korea’s destiny.

Kim Jong–un has overseen four nuclear tests and debuted ballistic missiles of various ranges, launched from multiple locations. STR/AFP/Getty Images

Bigger, badder, bolder

For the past six years, Kim has poked and prodded, testing and pushing the boundaries of international tolerance for his actions, calculating that he can handle whatever punishment is meted out. To a large extent, he has maintained the initiative on the Korean Peninsula, to the frustration of the United States and his neighbors. And as the U.S. and the international community have imposed ever stricter sanctions, Kim has chosen to double down on his nuclear weapons despite the financial consequences and the increasing international isolation.

Just two weeks after North Korean negotiators agreed to the 2012 Leap Day deal with the U.S., which called for a moratorium on Pyongyang’s nuclear and ballistic missile tests in exchange for food aid, the new Kim regime announced its intention to conduct a space launch, using the same ballistic missile technology banned by sanctions. Although that space launch failed, North Korea, despite international condemnation of the April test, had success with its next attempt, when it launched a satellite into orbit in December 2012. By portraying Kim Jong-un as a hands-on leader who personally ordered the rocket launch from a satellite command center, the state media framed their new leader as bold and action-oriented even in the face of widespread international censure. Two months later in February 2013—just a little over a year into Kim’s rule—North Korea conducted its third nuclear test, and Kim’s first.

Under Kim, North Korea has pressed the accelerator on nuclear and missile development and has codified its status as a nuclear-armed state by inscribing that description into the revised constitution it issued in 2012. It has also reinforced Kim’s role in advancing these nuclear capabilities, further solidifying his authority over their use. Kim has overseen three more nuclear tests, and debuted and tested new ballistic missiles of various ranges from multiple locations, including a submarine-launched ballistic missile and, in July and November 2017, intercontinental ballistic missiles.

North Korea shows every indication of making rapid progress toward the ability to threaten the United States and its allies, while also developing an arsenal for survivable second-strike options in the event of a conflict. But it has consistently asserted, as it did in the 2013 Law on Consolidating Position of Nuclear Weapons State, that the regime’s nuclear weapons are for deterrence. Subsequent authoritative statements, including the North Korean foreign minister’s remarks at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2017, have continued to hew to the same line: “[North Korea’s] national nuclear force is, to all intents and purposes, a war deterrent for putting an end to nuclear threat of the U.S. and for preventing its military invasion,” he said, adding that Pyongyang’s ultimate goal is to “establish the balance of power with the U.S.”

In Harm’s Way

In November 2017, North Korea tested intercontinental ballistic missiles with a potential reach of 8,000 miles–putting the entire United States in range.

While Kim has been developing and demonstrating advanced nuclear weapons capabilities, he has also focused on diversifying the North’s toolkit of provocations to include cyberattacks, the use of chemical and biological weapons, and the modernization of North Korea’s military, which is among the world’s largest armed forces with over 1 million warriors. Kim has presided over high-profile artillery firepower demonstrations, been captured in photographs poring over military plans purported to depict attacks against the United States and South Korea, and has issued inflammatory threats in response to U.S. and international pressure.

The rhetoric has also extended to threats against those who create negative portrayals of North Korea in popular culture. For example, in 2014, the regime said that the release of the movie The Interview —a comedy depicting an assassination attempt against Kim—would constitute “an act of war”; North Korean hackers threatened 9/11-type attacks against theaters that showed the film.

Although a 9/11-type event did not happen, the regime made it clear through a cyberattack that insults against Kim and North Korea would not be tolerated and that the financial consequences for the perpetrators would be dire. North Korean hackers destroyed the data of Sony Pictures Entertainment, the company responsible for producing the film, and dumped confidential information, including salary lists, nearly 50,000 Social Security numbers, and five unreleased films onto public file-sharing sites.

Yet, despite all the chest-thumping and bad behavior, Kim is not looking for a military confrontation with the United States. He is rational, not suicidal, and given his almost-certain knowledge of the significant deficiencies in North Korea’s military capacity, he is surely aware that North Korea would not be able to sustain a prolonged conflict with either South Korea or the U.S. Although Kim is aggressive, he is not reckless or a “madman.” In fact, he has been learning how and when to recalibrate. And it is his ability to recalibrate, change course, and shift tactics that requires us to heed Heuer’s warnings about the “weaknesses and biases in our thinking process” and continually challenge our assumptions and perceptions about “patterns of expectations” in North Korea analysis. We have to learn how to incorporate new information about what is driving Kim Jong-un and how we might counter this profound—and ever evolving—national security threat.

It is true that Kim has been emboldened since 2011, and he’s gotten away with a lot: scores of missile test launches, nuclear tests, the probable VX nerve agent attack against his half-brother in Malaysia, a 2015 incident involving a landmine in the DMZ, the Sony hack in 2014 in which North Korean entities wiped out half of Sony’s global network in response to the release of The Interview , and the mistreatment and death of U.S. citizen Otto Warmbier, a student tourist who was detained and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor for alleged hostile acts against the North Korean state. However, Kim has carefully stopped short of actions that might lead to U.S. or allied military responses that would threaten the regime.

That said, he has also been firm in his insistence that he will not give up North Korea’s nuclear weapons, regardless of threats of military attacks or engagement. It is clear that he sees the program as vital to the security of his regime and his legitimacy as the leader of North Korea. He may well be haunted by a very real fear of the consequences of unilateral disarmament.

The North Korean regime has often made reference to the fate of Iraq and Libya—the invasion and overthrow of its leaders—as key examples of what happens to states that give up their nuclear weapons. At the 2017 Aspen Security Forum, Dan Coats, the U.S. director of National Intelligence, said that Kim “has watched … what has happened around the world relative to nations that possess nuclear capabilities and the leverage they have,” and added that the “lesson” from Libya for North Korea is: “If you had nukes, never give them up. If you don’t have them, get them.”

If we unpack this comparison, we can envision how deeply Kim Jong-un might have been affected by the death of Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi. The once “king of kings in Africa,” who ruled Libya for four decades, was captured by rebels in October 2011, a date well into the process of grooming Kim for leadership and just two months before Kim Jong-il’s death. Graphic images of the bloodied Qaddafi ricocheted around the world. Contemporary reports described how Qaddafi was captured, hacked and beaten by a mob, shirtless and bloody, his body then stored in a freezer.

As Kim assumed his status as the newly anointed leader of North Korea, it’s likely that this imagery was seared in his brain. And Washington’s promises of a brighter future for North Korea if it denuclearized probably seemed hollow to the regime in Pyongyang. The North’s foreign ministry said at the time that the Libya crisis showed that the U.S.-led effort to coax Libya to give up its weapons of mass destruction had been “an invasion tactic to disarm the country.”

Moreover, Qaddafi’s death occurred during the so-called Arab Spring, when a wave of popular protests against authoritarian regimes convulsed the Middle East and North Africa between 2010 and 2011. The overthrow of regimes hitherto believed to be invincible probably highlighted for Jong-un the potential consequences of showing any signs of weakness, and reinforced the brutal suppression of dissent practiced by the Kim dynasty.

Even without all these warning signs, however, it is unlikely that Kim would have given serious consideration to denuclearizing his country. For him and his generation, people who came of age in a nuclear North Korea, the idea of disarming is probably an alien concept, an artifact of a distant “pre-modern” time that they see no advantage to revisiting, especially given the Trump administration’s hints about “preventive war” and the president’s own tweets threatening “fire and fury” against Kim and “military solutions [that] are now fully in place, locked and loaded.”

Dusk falls on Pyongyang, where three generations of Kims have ruled since the country’s founding in 1948. David Guttenfelder/National Geographic Creative

Edging Toward Hubris

North Korea’s highly provocative actions in the summer and fall of 2017—demonstrating ICBMs, conducting a test of a probable thermonuclear device, and threatening to detonate a hydrogen bomb over the Pacific—suggest that Kim’s confidence has grown over the past six years. After all, he has outlasted both South Korean president Park Geun-hye and President Barack Obama. Perhaps he thinks he can out-bully and out-maneuver President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping as well.

Such confidence may be bolstered by the fact that Kim has yet to face a real “crisis” of the kind his father and grandfather had to confront and manage. He has relied on military demonstrations and provocative actions to get his way, and has no experience in the arts of negotiation, compromise, and diplomacy.

Qualifications by Generations

Given the steady drumbeat of internal purges, the sidelining of North Korea’s diplomats since 2011 because of Kim’s focus on advancing his nuclear weapons program and conventional capabilities, and Kim’s apparent reveling in his recent war of words with President Trump—Kim called Trump “mentally deranged” in response to Trump’s personal attacks against Kim in his tweets and speech to the U.N. General Assembly in September—it would take a very brave North Korean official to counsel dialogue and efforts to mollify Washington and Beijing. Instead, Kim’s use of repression and his conferring of financial benefits and special privileges to loyalists has probably encouraged sycophants and groupthink within his inner circle, fueling his preference for violence and aggression.

But he may be reaching a critical point where he has to make a strategic choice. While Kim has avidly pursued nuclear weapons, he is also, in accord with his announced policy of byungjin , deeply invested in improving the North Korean economy—certainly a tall order given the gravity of internal changes, the weight of sanctions, and Beijing’s willingness to apply stronger pressure than we have seen before. Trends in North Korea’s internal affairs, such as greater information penetration from the outside world, loosening of state control over resources and markets, the rise of consumerism, and the growth of a moneyed class, will also place severe stresses on the Kim regime.

How North Koreans Get Their News

At the same time, international pressure on North Korea has never been greater. A number of recent actions have the potential to squeeze North Korea’s ability to earn hard currency for the regime to fund its economic and military goals, including: recent U.N. Security Council resolutions, such as the latest UNSCR 2397 in response to North Korea’s ICBM test in November; successful U.S. efforts to compel countries—including China—to cut off trade and financial links with North Korea; and President Trump’s September 21, 2017 executive order imposing new sanctions on North Korea (and authorizing broad secondary sanctions). These efforts also have the potential to undermine Kim’s ability to reward elites and suppress their ability to make money for themselves or raise money for loyalty payments to the regime.

The combined weight of all these pressures, internal and external, on North Korea, coming precisely at a time of rising expectations within the country, may overwhelm the regime—unless Kim learns to dial back his aggression. That, of course, is a big if.

We should be concerned about Kim’s hubris. In 2012, when Kim gave his first public speech, he ended with the line, “Let’s go on for our final victory.” At the time, despite the fact that it was delivered against the backdrop of a military parade featuring the biggest display of Korean weapons ever to have been seen by the world, it sounded to me like the bluster of a new, young leader. For all we know he may have been posturing then, but given recent developments and Kim’s likely increased confidence about his ability to call the shots, the U.S. and its partners and allies, including China, must be clear-eyed about the potential for Kim to shift his stated defensive position to a more aspirational one.

I still agree with the U.S. intelligence community’s assessment that “Pyongyang’s nuclear capabilities are intended for deterrence, international prestige, and coercive diplomacy,” as the director of National Intelligence testified in early 2017. But I believe it would be a mistake to extrapolate Kim’s future intentions from his past pronouncements and actions because we do not and will never have enough information about North Korea’s intentions and capabilities that will make us feel certain about our understanding of Kim. He and his country do not exist in an ahistorical space that is unchanging and static. Our analysis and policy responses must also change and evolve and be prepared for all potential scenarios. We, too, must avoid edging toward hubris.

Even as we parse every statement issued by North Korea, the country’s media content, the satellite imagery of its infrastructure, the state-sponsored videos, and the testimonies of defectors, we must remember that Kim is watching us as much as we are watching him. The U.S. must work to minimize the threat of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program without fueling conditions that could invite unintended escalation leading to armed conflict. The U.S. has opportunities to reshape Kim’s calculus, constrain his ambitions, and cause him to question his current assumptions about his ability to absorb increasing external pressure.

As I have written elsewhere , we can still test Kim’s willingness to pursue a different course and shift his focus toward moves that advance denuclearization. We can do so through strengthening regional alliances—especially with South Korea and Japan—that are demonstrably in lockstep on the North Korea issue. We can also increase stresses on the North Korean regime by cutting off resources that fund its nuclear weapons program and undermine Kim’s promise to bring prosperity to North Koreans, and ramp up defensive and cyber capabilities to mitigate the threat posed by North Korea against the U.S. and its allies. We should also intensify pressure on the regime through information penetration, raising public awareness of Pyongyang’s human rights violations, and create a credible, alternative vision for a post-Kim era to encourage defections.

Kim Jong-un is still learning. Let’s make sure he’s learning the right lessons.

Jung H. Pak is a senior fellow and the SK-Korea Foundation Chair in Korea Studies at the Brookings Institution’s Center for East Asia Policy Studies. She focuses on the national security challenges facing the United States and East Asia, including North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction capabilities, the regime’s domestic and foreign policy calculus, internal stability, and inter-Korean ties. She has held senior positions at the Central Intelligence Agency and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Prior to her work in national security, Pak taught U.S. history at Hunter College in New York City and studied in South Korea as a Fulbright Scholar.

Now more than ever, facts and research matter. Sign up to get our best ideas of the day in your inbox.

Stanford University

“What Did You Do as We Were Dying?”: The Urgency of Addressing North Korean Human Rights

- Gi-Wook Shin

This essay originally appeared in Korean on January 27 in Sindonga (New East Asia), Korea’s oldest monthly magazine (established 1931), as part of a monthly column, "Shin’s Reflections on Korea ." Translated by Raymond Ha. A PDF version of this essay is also available to download.

During the Moon Jae-In administration, many of my American friends and colleagues were puzzled and disappointed by a strange contradiction. The former pro-democracy activists—who had fought for democracy and human rights in South Korea—had entered the Blue House, only to turn a blind eye to serious human rights abuses in the North. In particular, the Moon administration punished activists who sent leaflet balloons across the border and forcibly repatriated two North Korean fishermen who had been detained in South Korean waters. It not only cut the budget for providing resettlement assistance to North Korean escapees, but also stopped co-sponsoring United Nations (UN) resolutions that expressed concern about the human rights situation in North Korea. My friends, including individuals who had supported South Korea’s pro-democracy movement decades ago, asked me to explain this perplexing state of affairs. I had no clear answer.

A Gross Overstepping of Authority

On April 15, 2021, the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission held a congressional hearing on “civil and political rights in the Republic of Korea.” [1] The speakers expressed their concern about worrying trends in South Korea’s democracy. In his opening remarks, Rep. Chris Smith, the co-chair of the commission, stated that “the power that had been given [to] the Moon Administration, including a supermajority in the National Assembly, has led to a gross overstepping of authority.” He observed that “in addition to passing laws which restrict freedom of expression, we have seen politicization of prosecutorial powers. . . and the harassment of civil society organizations, particularly those engaged on North Korea issues.” [2] Expressing his disappointment at the Moon administration’s North Korea policy, Smith twice referred to my 2020 analysis of South Korea’s “democratic decay” published in the Journal of Democracy . [3]

Rep. James McGovern, the other co-chair of the Tom Lantos Commission, noted in his remarks that “international human rights law provides guidance on what is and is not acceptable when it comes to restricting freedom of expression for security reasons.” [4] This hearing had echoes of U.S. congressional hearings in the 1970s, when there was criticism of South Korea’s authoritarian practices.

South Korea’s progressives, including those who served in the Moon administration, may respond that criticizing North Korea for its human rights practices infringes upon Pyongyang’s sovereignty. They may argue that emphasizing human rights will worsen inter-Korean relations and make it even more difficult to address the security threat posed by North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missiles. This argument may appear to have some face validity, since Pyongyang has responded to criticisms of its human rights record with fiercely hostile rhetoric. The same progressives, however, did not regard it as an encroachment upon South Korea’s sovereignty when the U.S. government and American civil society criticized Seoul for its human rights violations during the 1970s and 80s. In fact, they sought support from various actors in America and welcomed external pressure upon South Korea’s authoritarian governments during their fight for democracy.

We must ask ourselves whether the Moon administration achieved durable progress in inter-Korean relations or on denuclearizing North Korea by sidelining human rights. There is no empirical evidence to support the assertion that raising human rights will damage inter-Korean relations or complicate negotiations surrounding North Korea’s nuclear program. While there are valid concerns about how Pyongyang may react, it is also true that past efforts have failed to achieve progress on nuclear weapons or human rights. Both the Moon and Trump administrations sidelined human rights in their summit diplomacy with Kim Jong-Un, and their efforts came to naught. They compromised their principles, but to what end?

This is not to say that raising human rights issues would certainly have yielded tangible progress in improving inter-Korean relations or dismantling Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons. Rather, I like to point out that there is no reason or evidence to believe that there is an obvious link between raising human rights in a sustained, principled manner and the success or failure of diplomatic engagements with Pyongyang. The arguments given by South Korea’s progressives are not sufficient to justify neglecting human rights concerns when addressing North Korea. Furthermore, criticizing another country’s human rights practices is not seen as an unacceptable violation of state sovereignty. The international community regards such discussions on human rights as a legitimate form of diplomatic engagement.

The Error of Zero-Sum Thinking

The abject state of human rights in North Korea is not a matter of debate. In addition to the operation of political prison camps and the imposition of draconian restrictions on the freedoms of thought, expression, and movement, the country suffers from a severe food crisis. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s September 2022 International Food Security Assessment estimated that close to 70% of the country’s population was “food insecure.” [5] The border closure imposed due to the COVID -19 pandemic has resulted in a sharp decline in trade with China, which plays a vital role in North Korea’s economy. By all indications, the people of North Korea are likely to be in dire straits. James Heenan , the head of the UN Human Rights Office in Seoul, stated in December 2022 that the human rights situation in North Korea is a “black box” due to difficulties in obtaining information as a result of COVID -19 border controls. [6] Freedom House’s 2022 report gave North Korea 0 points out of 40 in political rights, and 3 out of 60 in civil liberties, resulting in a total score of 3 out of 100. Only South Sudan, Syria, and Turkmenistan have lower scores. [7]

Nonetheless, Pyongyang continues to pour an enormous amount of resources into developing nuclear weapons and advanced missile capabilities. According to South Korean government estimates, North Korea spent over $2 million on launching 71 missiles in 2022. This was enough to buy over 500,000 tons of rice, which could provide sufficient food for North Korea’s population for 46 days. The same amount would also have made up for over 60% of North Korea’s estimated food shortfall of 800,000 tons in 2023. [8] In its single-minded pursuit of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, the North Korean regime has shown utter disregard for the human rights of its population.

The details of North Korea’s human rights record are available for anyone to see in the reports of the UN Special Rapporteur on North Korean human rights, as well as the U.S. State Department’s annual country reports on human rights practices. [9] In particular, a 2014 report published by the UN Commission of Inquiry (COI) on North Korean human rights found that “systematic, widespread and gross human rights violations have been and are being committed by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, its institutions and officials.” Moreover, the COI concluded that “in many instances, the violations of human rights found by the commission constitute crimes against humanity.” [10]

North Korea’s headlong pursuit of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles is inextricably tied the human rights situation in the country. When allocating available resources, Pyongyang prioritizes the strengthening of its military capabilities. The health, well-being, and human rights of the population are of peripheral concern. An array of international sanctions imposed against the regime may constrain its budget, but it will pass on the cost to the population, further worsening their suffering. In addition, there can be no meaningful solution to security issues without improving the human rights situation. A government that values military strength over the welfare of its people will not hesitate to use force against other countries.

The North Korean nuclear problem, inter-Korean relations, and human rights issues are closely intertwined, which necessitates a comprehensive approach to North Korea policy. Ignoring human rights does not make it easier to achieve progress on security issues. Victor Cha refers to this as the “error of zero-sum thinking about human rights and U.S. denuclearization policy.” [11] There is an urgent need to formulate a holistic approach that can foster mutually beneficial engagements between Pyongyang, Seoul, and Washington. Reflecting upon the shortcomings of past U.S. policy toward North Korea, Cha notes that marginalizing human rights has not yielded any meaningful progress on the nuclear problem. He argues that it is first necessary to craft a comprehensive strategy that fosters positive-sum dynamics between security issues and human rights. This strategy will then provide a road map for future negotiations by specifying the standards and principles that should be observed.

Avoiding Demonization and Politicization

To generate positive-sum dynamics between human rights and security issues, it is important to refrain from demonizing North Korea. Taking a moralistic approach along the lines of the Bush administration’s “axis of evil” will do little to improve the human rights situation in North Korea. The purpose of raising human rights issues must not be to tarnish the North Korean leader’s reputation or to weaken the regime. As Ambassador Robert King, the former U.S. special envoy on North Korean human rights issues, stressed during a recent interview with Sindonga , human rights should not be weaponized for political purposes. [12] The world must call upon North Korea to improve its human rights record as a responsible member of the international community. If Pyongyang shows a willingness to engage, other countries should be ready to assist.

North Korea usually responds with aggressive rhetoric to criticisms of its human rights record, but it has taken tangible steps to engage on certain occasions. Even as it denounced the February 2014 report of the UN COI, North Korea sent its foreign minister to speak at the UN General Assembly in September for the first time in 15 years. In October, Jang Il-Hun, North Korea’s deputy permanent representative to the UN in New York, participated in a seminar at the Council on Foreign Relations to discuss North Korean human rights. [13] Even though it forcefully denies the international community’s criticism, North Korea appears to have realized that it cannot simply sweep the issue under the rug. Some argue that North Korea’s limited engagements on human rights are empty political gestures to divert attention. Nonetheless, North Korea also understands that it must improve its human rights record if it hopes to establish diplomatic relations with the United States.

Instead of using human rights as a cudgel to demonize North Korea, it is vital to identify specific issues where it may be willing to cooperate. So far, it has refused to engage on issues that could undermine regime stability, such as closing political prison camps, ending torture, and guaranteeing freedom of the press. On the other hand, it has shown an interest in discussing issues that do not pose an immediate political threat, such as improving the situations of women, children, and persons with disabilities. By seeking avenues for dialogue and cooperation, the international community can try to achieve slow but tangible progress on improving the human rights situation in North Korea.