Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Parenting & Family Articles & More

How identity shapes the well-being of asian american youth, two new studies reveal the diversity of asian american paths to health and resilience..

Like many kids growing up in the United States, I came of age straddling two cultures: that of my family’s country of origin, and mainstream/majority American culture.

There was a significant Asian American community where I grew up, and among my friends I saw many ways in which families negotiated these two cultures. Some families spoke their first language at home, some didn’t. Some ate their heritage foods for all their meals, some only for special occasions. Some made annual trips to their country of origin, while others never or seldom visited. Mixed into these everyday practices, parents modeled attitudes about race, racism, and the majority culture, verbally and nonverbally.

All of these ingredients in an upbringing make up what social scientists call the ethnic-racial socialization of children—and as two new studies suggest, those choices have consequences for the health and well-being of young people.

“Asian American youth are quite different from each other,” says Tiffany Yip, a psychologist at Fordham University and coauthor of one of the studies. “There are very different ways in which Asian youth form a sense of who they are and how they make sense of the world.”

Can values foster well-being?

In a study published by the Journal of Counseling Psychology , Annabelle L. Atkin and Hyung Chol Yoo at Arizona State University surveyed 228 Asian American college students about the racial-ethnic socialization they received from their parents, their understanding of their own racial-ethnic identity, and their feelings of social connectedness.

Using latent profile analysis—a method of identifying subgroups based on certain variables—Atkin and Yoo identified three patterns of parental racial-ethnic socialization:

- Guarded separation. This group was by far the smallest, at a tenth of those surveyed. These students were encouraged to maintain ties to their heritage culture, and were also told to avoid people of other racial-ethnic groups. They also received few messages about adapting to mainstream American culture, respecting other cultures, and treating people equally.

- Passive integration. This group received frequent messages about staying connected to their heritage culture, but received few other socialization messages with regard to other racial ethnic groups or being American. They were 43% of those surveyed.

- Active integration. Almost half of the students also received frequent messaging about preserving their heritage culture, and received fewer messages about avoiding out-groups. However, this group was distinguished by the frequent messages students received about treating people equally and respecting diversity.

Findings in the study showed that the “active integration” group reported the highest scores of clarity and pride in their racial-ethnic identity, as well as the strongest feelings of social connectedness. This result suggests to the authors that therapists, social workers, teachers, and others who work with families might encourage bicultural socialization, low avoidance of out-groups, minimization of race, and promotion of equality and cultural pluralism as a way to support the resilience and mental health of Asian American youth.

The authors further note that the patterns of parental socialization identified in these profiles are in and of themselves significant, and emphasized the importance of looking at these multidimensional profiles holistically. Their findings indicate that “despite engaging in the same amount of socialization in several domains, if parents differ in how they engage in other socialization domains, their children may report different outcomes related to racial-ethnic identity and adjustment.”

For example, the “guarded separation” group had the lowest racial-ethnic identity scores (cognitive clarity, affective pride, behavioral engagement) even though it received the most frequent messages about maintaining ties to their heritage culture; this group also received the most frequent messages about avoiding out-groups and the least frequent messages about cultural pluralism and equality.

These findings suggest that Asian American children grow up hearing many kinds of messages about their heritage culture and becoming American, further complicated by the inclusion of messages about race and racism, and that all of these messages function synergistically in the formation of one’s racial-ethnic identity.

There’s no one path to wellness

In another study published last month in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence , researchers from Beijing Normal University and Fordham University surveyed 145 Asian American high school students about their “ethnic-racial knowledge.”

As in the previous study, the researchers asked the students about their parents’ socialization practices and their sense of their ethnic-racial identity—but this study also included questions that measured to what extent these students had internalized the “model-minority narrative,” the myth that Asian Americans are successful by virtue of their race/ethnicity. Their latent-profile analysis also identified three groups:

- Salient. This was the smallest group, at 13% of respondents. They reported high levels of ethnic-racial identity, greater cultural socialization, and relatively low levels of preparation for bias, and moderate internalization of achievement orientation.

- Moderate. At 72%, this was by far the largest group—and its members reported moderate levels of all indicators.

- Marginal. Fifteen percent reported relatively low levels of ethnic-racial identity, less cultural socialization, and comparatively high levels of preparation for bias and slightly less internalization of achievement orientation.

The researchers also collected data related to these students’ duration and quality of sleep, their psychological well-being (depressive symptoms and measures of self-esteem), their academic performance (grades and school engagement), and delinquency.

In this study, in contrast to the one by Atkin and Yoo, the researchers found no clear benefits to one group across any of these measures of health and well-being. For example, in the areas of self-esteem and school engagement, the salient group scored higher than both the moderate and marginal groups, but neither of the latter groups scored better than the other. The marginal group scored the highest in depressive symptoms, but neither the salient group nor the moderate group scored better than the other. Each group scored higher in some aspect of sleep quality, but no one group had the clear advantage in sleep quality overall.

“If you look at the adjustment outcomes for all of these profiles, some profiles do better on sleep indices, some profiles do better on socio-emotional outcomes,” says Yip, the study’s coauthor. “That’s the power of this study, that we have multiple dimensions of health and well-being.”

The complexity of the findings, she says, “underscores the importance of a really nuanced approach to thinking about Asian American youth and their development.”

Like the authors of the previous study, Yip says that regardless of the findings related to the outcomes of these profiles, identifying their patterns is a crucial result of the study, because it reveals the diversity of experiences that Asian Americans bring with them into adulthood. As these profiles illustrate, not all Asian American youth relate to their racial-ethnic identity in the same way.

This may be “a little bit less obvious to people who haven’t really stopped to think about what these model-minority perceptions do in terms of homogenizing the Asian American experience,” says Yip. “So I think it’s incredibly important to show that there are Asian kids for whom their ethnic identity is not that relevant—they don’t think about it, they don’t care about it, it’s not important to who they are. That’s the marginal group.” And then there are some kids, like those in the salient group, for whom their Asian American identity is “really, really important.”

Then there’s the moderate group, at 72% of those surveyed. “What’s interesting,” Yip says, “is that middle group that’s sort of average on everything—that’s actually the biggest group. I think there’s a tendency for non-Asian people to see Asian people as only Asian, but these data are telling us that there are Asian youth for whom being Asian is like, meh. It’s part of who they are, it may not even be that important.”

This is an important thing to understand, she says, not only for clinicians, but for anyone who interacts with Asian American youth “on a daily basis, in their role as educators, neighbors, friends, sports coaches.”

So how can Asian American parents optimize the health and well-being of their kids? Which families of my childhood were getting it right? As both studies show, when it comes to racial-ethnic socialization, there isn’t just one prescription, or pattern of messages, that best serves all or most kids.

And as is true about most aspects of parenting, it’s important to keep in mind that every child is different, says Yip—even when it comes to teaching about racial-ethnic identity. She continues:

As parents, it’s really important for us to recognize what our child brings to their own socialization and to be flexible and adaptable enough to use that individuality that they’re bringing, to tailor our parenting approaches, whether it’s around issues of culture, ethnicity, race, discrimination, whatever it is, that we have some tools that allow us to be adaptable and responsive to the unique needs of each child.

About the Author

Shinwha Whang

Shinwha Whang is a writer in Richmond, CA.

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69240126/Copy_of_I_AWP_Folder_8_001_OK.0.jpg)

What does it mean to be Asian American?

The label encompasses an entire continent of different cultural roots. Does it speak to a shared experience?

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: What does it mean to be Asian American?

The label “Asian American” is almost comically flattening.

It consists of people from more than 50 ethnic groups, all with different cultures, languages, religions, and their own sets of historic and contemporary international conflicts. It includes newly arrived migrants and Asians who have been on American soil for multiple generations. Depending on visa types, immigration status, and class, there are vast differences even among those from the same country. In fact, the income gaps between some Asian American groups are among the largest of any ethnic category in the nation. Yet these differences are rarely explored and discussed.

With the recent rise in anti-Asian attacks, however, Asian Americans have found themselves in a rare moment in the national spotlight. For many, it has led to a renewed sense of solidarity as well as confusion about what the Asian American label means or if there really is a unifying experience attached to it.

It also inspired Vox to post a survey asking Asian Americans to write in and tell us how they’re feeling right now. The rise in violence — especially the shootings at three spas in Atlanta that left eight people dead, including six women of Asian descent — haunted the responses. One major theme emerged: Why did it take such an extreme act of violence to get America to care about its Asian communities?

“It frustrates me that the anti-Asian sentiments popularized by Trump had to be escalated to media-worthy violence and mass shootings in order to be elevated to mainstream discourse,” one person wrote from California.

“We’re trending today, but I bet we’ll be forgotten by next week or month,” wrote another from Michigan.

Other persistent issues emerged from our survey, too. Many responded that they didn’t quite know how to talk about cultural identity or racism with their parents or their children. The experience of growing up in non-diverse areas versus immigrant- or minority-dense enclaves — and how different it felt when moving from one area to another — also kept coming up. People with roots in South and Southeast Asian cultures wondered how they fit into an ethnic category so commonly associated with East Asians. Many questioned what the label Asian American really means and what purpose it serves in the larger American conversation around race.

In a series of stories publishing throughout this month, we will explore some of these questions and shared experiences, in a time when many Asian Americans are experiencing a sense of alienation not only from the nation at large, but also from the label “Asian American” itself.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22489117/HANIFAFINAL.jpeg)

The pitfalls — and promise — of the term “Asian American”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22508965/Vox_Asian_American_identity.jpeg)

The many Asian Americas

by Karen Turner

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22527840/lizziechen_crop.jpg)

In many Asian American families, racism is rarely discussed

by Rachel Ramirez

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22538174/Vox___Lane_Kim___Sanjena_Sathian___AK___Final.png)

Seeing myself — and Asian American defiance — in Gilmore Girls’ Lane Kim

by Sanjena Sathian

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22657577/Screen_Shot_2021_06_14_at_10.17.21_AM.png)

The Asian American wealth gap, explained in a comic

by Lok Siu and Jamie Noguchi

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

What the Ohio train derailment teaches us about poisoning public trust

The michigan school shooter’s parents face precedent-setting sentences, americans are hooked on the fantasy of financial liberation, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

- HISTORY & CULTURE

- RACE IN AMERICA

'I've walked between two worlds': What belonging means for Asian Americans

Asian American families across generations reflect on the ways they hold on to their cultures while finding a place in America.

For most of my life, I hated my name. Before I was born, my parents, who had come to the United States from China a few years before, had chosen to call me Elaine, but my mom’s sole white friend at the time told her that it was an old-lady name. She suggested Alyssa instead.

My dad didn’t know how to spell that, so when the time came to register me, he sounded it out, figured “Alyssa” sounded like “eleven,” threw in a couple of S’s for good measure, and there I was, hours old and legally bound to this strange portmanteau, Elessa.

I still ended up going by Elaine, perhaps because my parents wanted me to use my Chinese name, Yilan. When I arrived in school, no one could say it and Yilan gradually became Elaine.

It didn’t matter much to my parents, who never use either of these English names for me. But it mattered to me. I hated Elessa, hated the question mark in the teacher’s voice on the first day of school, hated never finding it on a keychain or magnet, hated that it wasn’t “real.” I wasn’t even like the other kids who went by their Chinese or Korean names. My immigrant parents had done the most embarrassing thing possible as far as I was concerned: make something up. Elessa was proof of assimilation gone wrong, evidence that we didn’t belong.

I made everyone call me Elaine, I told this story like it was a big embarrassing joke, and when I turned 18, I changed my name legally. When I saw my name written on my college diploma, I hardly remembered there had ever been a different one. I was Elaine now, fully assimilated Chinese American, and no one could question where I’d come from.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Elessa, and how that name made me feel, has come back to me recently with the sharp rise in anti-Asian hate crimes across the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though Asian Americans are now the country’s fastest-growing racial or ethnic group, watching videos of elderly people being attacked in broad daylight—worrying that my parents could be next—reminds me that even if we change our names, even if we see ourselves as Americans, others may not see us that way .

In light of the March spa shooting in Atlanta that killed eight people , six of whom were of Asian descent, I sought to understand how people in a city where the most high-profile hate crime against Asians had occurred, felt about their place in America and what it means to them to belong.

What’s in a name?

On a recent spring afternoon, DD Lee, a 39-year-old woman who moved from China as a child, is laughing over Zoom, remembering her 12-year-old self. Living in Kentucky and in need of a new name, she picked “Annette” out of a book. She tried it on for a couple months, then went with Dina in high school before a friend suggested DD, the initials of her Chinese name, Dan Dan.

“There was literally an identity crisis when it came to the name part of things,” she says.

Lee was one of many Atlantans who shared a story about their name, and how it represented a fundamental question of who they were in this country. They remembered childhoods spent figuring out how to fit in, of striking the right balance between Asian and American, of holding onto their families’ cultures without feeling like an outsider.

Shawn Wen, 39, also didn’t have an English name as a kid. His father, who emigrated from Taiwan, didn’t give him one because he wanted his sons to find their names for themselves. He went by his Chinese name, I-Hsiang, at school, and was bullied for being “the smallest Asian kid” with a “horrible” name. At home he struggled with his parents’ expectations and joined the military out of high school to prove his father wrong.

“I’ve walked between two worlds: Having to balance the expectations of my cultural community while also confronting the realities of American society and its expectations of me as an Asian American,” he says. “Sometimes I haven’t felt like I’ve belonged to either.”

He chose the name Shawn in middle school but changed it again as an adult after making peace with his father. After many years of struggling with his identity, he says he’s found his name, and with it, where he belongs: “My Asian American name is Shawn I-Hsiang Wen.”

Reminders of home

Many of the people I spoke with remember being the only Asian family in town, the only Asian kid in school. They sought refuge in food, in the ingredients of home. When they couldn’t find them in the one Asian store within driving distance, they grew their own.

You May Also Like

This crippling disease often goes under-diagnosed—unless you’re white

How Chien-Shiung Wu changed the laws of physics

This American diet could add 10 years to your life

Hannah Son and her family would drive an hour and a half from Macon, Georgia, to Atlanta every Sunday after church to load up on Korean groceries for the week. When they moved to Gwinnett County, a suburban part of Atlanta with a larger Asian American population, it was “a big culture shock for me,” she says. “I didn’t know there were other Asian people in Georgia.”

Ruth McMullin, whose Black GI father and Vietnamese mother fled Vietnam in 1975, remembers the pride her mother felt about her bitter melon crop. A world away from her homeland, she grew these spiky, green reminders of Vietnam in the small Alabama town where they settled. “Everybody who came over thought that was the strangest thing,” McMullin says. “But she was pleased as punch.”

As a biracial child growing up in the Deep South at a time when there were very few kids like her, McMullin was picked on and felt like she didn’t belong to any group. Even today, she carries a photo of her mother as “street cred at Asian markets” because people don’t believe she’s of Vietnamese descent.

“If I had a sense of belonging, I wouldn’t have to pick one culture or the other. A lot of times society expects you to pick,” she says. “Why would I? It’s all of me.”

Who gets to belong?

For Mila Konomos, 45, being around the foods and norms of Korean culture made her feel even more confused about herself. She grew up on U.S. military bases as part of a white family that adopted her from Korea when she was six months old. Other kids in the predominantly white community, including her brothers, bullied her for her looks, and made her hate being Asian, she said.

When the family moved to California when she was a teenager, she met other Asian American kids and made friends, but they didn’t accept her either. They didn’t understand that she’d never had kimchi before or would make fun of her when she tried to speak Korean.

“I received a lot of shaming from Asian peers and the Asian community, you know, being called a twinkie or a banana—as if I had any choice in my situation,” she says.

Listening to Konomos, I felt ashamed of myself. I wanted to apologize to her even though we’d never met. I grew up in Southern California in a tightly knit Chinese community where 99 Ranch Market replaced Ralph’s as the go-to supermarket and entire shopping complexes were filled with all-you-can-eat Korean barbecue, boba shops, and tofu houses. My parents and their friends constantly compared us kids to each other, engaging in a complex psychological game of reverse one-upmanship. “No, your kid’s Chinese is so good.”

My friends and I judged other ABCs (American-born Chinese) who couldn’t switch between Mandarin and English seamlessly or who shamed their parents by using forks. They weren’t as good as us, couldn’t handle their bifurcated identity. We also looked down on kids who were, as we called them, “FOBs” (fresh off the boat), the ones who wore socks with sandals or whose haircuts looked like our grandparents. Somewhere between the twinkies and the FOBs was a place for us, the well-adjusted immigrants, the ones who really belonged.

Konomos would have been one of those kids we judged, and weeks later, something she said has stuck with me.

“For a long time, I felt like I had to become Korean,” she says. “What I realized is, no, I am Korean. Even if I don’t speak the language, even if I don’t celebrate all the traditions, even if I don’t always eat all the food, I’m still Korean, and Koreans need to expand their idea of who is allowed to be Korean.”

As a child, I came to understand that there are many ways to be American, just as there are many ways to be Asian. But as I listened to people share their stories at a time when our belonging is being challenged with violence, I realized I had had a very specific idea of how to be Asian American: It was to be Elaine—when, actually, Elessa is just fine.

Elaine Teng is a writer and editor at ESPN. ESPN and National Geographic are both owned by The Walt Disney Company. Follow her on Twitter at @elteng12 .

Haruka Sakaguchi is a Japanese freelance photographer based in New York. See more of her work on her website or by following her on Instagram @ hsakag .

Related Topics

- ASIAN AMERICAN AND PACIFIC ISLANDERS

- IMMIGRATION

What’s it like to be an immigrant in America? Here’s one family’s story.

She designed Jackie Kennedy’s wedding gown—so why was she kept a secret?

What exactly is a Yankee?

Which cities will still be livable in a world altered by climate change?

How street fashion sparked a WWII race riot in Los Angeles

- History & Culture

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Find anything you save across the site in your account

All products are independently selected by our editors. If you buy something, we may earn an affiliate commission.

The Difficulty of Being a Perfect Asian American

College admissions makes people do strange things. This was one of the takeaways of the Varsity Blues scandal , in 2019, which uncovered an admissions consultant and a network of coaches and administrators who helped wealthy and famous families essentially bribe their way into selective colleges. The scandal seemed to be the twisted, if logical, end point of all the credential-stacking and résumé-padding that has become part of the process. Yet there was something reassuring about the scandal, too: the conclusion that the admissions system is rigid enough that people with means, even Hollywood A-listers, would feel the desperation to game it. They may have believed that their children were entitled to a place at a prestigious school. But they couldn’t breeze right in. By some measures, it is twice as hard to get into élite colleges and universities than it was twenty years ago. Their desperation was warranted.

These anxieties about status are acutely felt among a cohort for whom going to college can seem a foregone conclusion. Asian Americans are often held up as a “model minority,” a group whose presence on campuses like Harvard or M.I.T., where forty per cent of incoming first-years self-identify as Asian American, far outpaces their percentage of the U.S. population. The figure of the model minority emerged in the fifties, a reflection of Cold War-era policies that were designed to attract highly educated immigrants from Asia. Over time, this stereotype ossified. American meritocracy held up the immigrant as proof that its rules were fair, and many high achievers were flattered to play along. Even though many of the gains for Asian Americans could be explained through policy—and even as studies showed how entire swaths of the community were left behind in poverty—the experience of being Asian in America has been rigidly defined by a framework of success and failure. As the scholar erin Khuê Ninh argues in “ Passing for Perfect: College Impostors and Other Model Minorities ,” it’s a framework that has been internalized, even by those who resist it.

Ninh’s fascinating book tells the stories of scammers, grifters, and impostors—Asian Americans following the high-pressure, expectation-heavy paths that can lead down darker alleys of faux accomplishment. There is Azia Kim, who masqueraded as a Stanford undergrad for months, even persuading two students to allow her to share a dorm room. Elizabeth Okazaki did something similar there, posing as a graduate student, attending class, and sleeping at a campus lab. Unlike the students caught up in the Varsity Blues scandal, these young people gave exhausting performances that weren’t going to result in a diploma or job. And, in the case of Jennifer Pan, who spent years tricking her parents into believing that she was attending the University of Toronto, the subterfuge resulted in tragedy. In 2010, she hired hitmen to murder them.

What compelled these impostors? To what extent were their actions driven by a need to keep up an illusion of excellence? Ninh, who teaches at the University of California, Santa Barbara, explores these stories not to rationalize them but to point out how they suggest a mood, a limited set of emotional possibilities for Asian Americans. “What if what seem to be outlandish and outlier behaviors are instead depressingly Asian American?” Ninh writes. Being a model minority, she argues, doesn’t require one to believe in the myth. Ninh asserts that a relationship to high achievement is “coded into one’s programming” as an Asian American, and that “its litmus test is whether an Asian American feels pride or shame by those standards.” Whether you are Amy Chua, extolling the virtues of being a “ tiger parent ,” or someone making fun of Chua, you are perpetuating the success-or-bust framework. A joking dismissal doesn’t debunk the stereotype so much as it signals the impossibility of living outside of it.

Ninh offers compelling evidence that adherents to the model-minority myth come “from an implausible multiplicity of life chances and immigration histories.” She cites the scholars Jennifer Lee and Min Zhou, who found that Southeast Asian refugees and wealthy, cosmopolitan transplants from China alike were “keenly aware” of stereotypes around Asian achievement. Lee and Zhou write that “for no other [racial] group is the success frame defined as getting straight A’s, gaining admission into an elite university, getting a graduate degree, and entering” into a coveted profession; in contrast, other groups balance grades with an investment in classroom behavior or how well they fit in with others. Ninh cites a 1998 study of perceptions of Asian Americans, based on interviews conducted with seven hundred college students of all races. A sense of Asian Americans as somehow exemplary permeated this student body; notably, the Asian Americans who took part in the interviews perceived themselves to be “more prepared, motivated, and more likely to have higher career success than whites,” even though their actual grades didn’t reflect any superiority.

Of all deceits, Ninh wonders if there is “something quaintly bookish, faintly charming about the academic grifter.” What drew Kim, Okazaki, Pan, and others to lie wasn’t a predictably ascendant path. Pretending to be students was a holding pattern, perhaps until a better answer presented itself. As Ninh points out, “The shortest route to mad bling does not run through four years of coursework. Money, then, would not appear to be the primary driver for our scammers— status is, arguably, and self-identity.”

Ninh feels enough sympathy for her subjects to probe their ambitions, their potential, the unnoticed mental-health struggles that led these people to take such immense risks. “Even when we have come to know our social formation as harmful to us,” she writes, “a life worth wanting may still be trapped in its terms.” The scammers and grifters might be viewed as people who allowed the expectations of Asian American identity to metastasize into something perilous. Ninh’s book is at its best when she seems to level with her subjects, to read them against their contexts: high-pressure parents, suburban milieus where value is doled out in how many colleges you get into, a national myth where you are both an undifferentiated mass and living proof of the American Dream. It’s a lot of work to pretend you are perfect—even more so when you know it is an illusion. Studies show that Asian Americans are the racial group who are least likely to seek help for mental illness, with much of it remaining undiagnosed. In 2018, Christine Yano and Neal Adolph Akatsuka published “ Straight A’s: Asian American College Students in Their Own Words ,” a collection of reflections from Harvard undergraduates. The achievements of these students aside—these were young people who, by traditional metrics, had done well—it was striking how each one navigated expectations of success and feelings of invisibility. Many lamented how the quest for excellence came to feel like a trap, ultimately leaving them unfulfilled. Even a drive to pursue unconventional paths, like art or writing, was cast as a rebellion against STEM stereotyping, not an expression of authentic desire.

“Passing for Perfect” is a tricky, unpredictable book, toggling between broad social analyses and sensational outliers, with close readings of reportage and court documents alongside Ninh’s bemused, occasionally exasperated commentary. Her shifting tones convey what it feels like to live inside a stereotype—to realize that even reasoned disavowals will never make it go away. She wonders whether it is possible to tunnel your way free from an imposed identity you know to be unhealthy and false. Stereotypes winnow down our imaginations or make us feel inadequate in the present; they also stifle a vision for the future, frustrating us, as our attempts to deny them only make them grow stronger.

The challenge, Ninh acknowledges, is to talk about success in terms that don’t merely reify the myth of the model minority. The starting point is to imagine other models of teaching, assessing, or assigning value. For the individual, resisting the myth requires more than merely becoming a “bad Asian”—for example, by rejecting the stereotype that Asians are good at math and violin by opting for art and football. Her book ends with a consideration of “Better Luck Tomorrow,” a film, from 2002, that drew on elements of the 1992 killing of Stuart Tay, a teen-ager from Orange County. Tay was killed by five students from a competitive, affluent high school. Tay and his eventual killers—four of whom were Asian American—were plotting a robbery, and his conspirators became convinced that he was going to betray them. Three of Tay’s killers were honor-roll students, leading the press to refer to the event as the “honor roll murder.”

In the movie version, the culprits’ murderous success burnishes the model-minority image; they excel at their studies as well as their criminal dalliances. As the movie ends, it is possible to believe they got away with it. But, in one of the most harrowing parts of “Passing for Perfect,” Ninh discusses the movie with two of Tay’s killers, Kirn Young Kim, who was paroled in 2012 and is now a prison-reform activist, and Robert Chan, who remains incarcerated. They lament that the characters in the film essentially win, rather than, in Ninh’s words, pull up short and offer “a cold, hard look at what all the work is for.” She notes that Chan has spent his time in prison unlearning the anger and “hypermasculinity” that defined his high-pressure teen years. And yet, in his mother’s home, a framed letter hangs on her bedroom wall. It is an invitation from the Harvard-Radcliffe Club of Southern California to interview for admission.

From the distance of middle age, the pressure to achieve looks like a race toward a false horizon. Of course, this isn’t how it’s experienced. Debbie Lum’s recent documentary, “Try Harder!,” offers an absorbing exploration of the pressures internalized by today’s high-school students. It chronicles a year at Lowell High School , a public magnet school in San Francisco that was, at the time Lum was filming, roughly fifty per cent Asian American. (Up until recently, students had to test into Lowell. As a result of a 2021 change to the school’s admissions, the demographic is expected to shift.)

Lowell is one of the top public schools in California, and therefore the nation—the type of place where even those with astronomical G.P.A.s and perfect SATs feel intense worry about their futures. The type of place where a kid who rallies his wallflower friends at the school dance compares himself to an enzyme.

Students talk about a “war on two fronts,” the competitive environment of the school itself and the pressure they feel from their families. For many, the only way to cope is to joke about how impossible it is to truly measure up. As “Try Harder!” begins, there’s a whimsical quirk to Lum’s storytelling. A charismatic Chinese American student named Ian cracks that he is “not even close to the best of the best.” He is self-effacing and funny. Everyone starts at Lowell dreaming of Stanford, he explains. By sophomore year, the Stanford hoodies are relegated to the closet, and expectations grow more realistic: the U.C.s. By junior year, he says, kids settle for Occidental, a “West Coast private college that’s not that hard to get into.”

Lum follows a few students through their days, which are dizzying. Lowell seems a challenging place to distinguish oneself. A physics teacher implores the students to give up their fetish for prestige, pointing out that “you are not too good for Santa Cruz, or Riverside, or even Merced,” which are often perceived to be among the U.C. system’s lesser schools. There’s no way to win. On one hand, they must excel in their local rat race. On the other, Lowell doesn’t send as many students to schools like Stanford or Harvard as you might think. The students—and at least one teacher—suspect that, for top colleges, Lowell seems too “stereotypically Asian,” a monolith of “A.P.-guzzling grade grubbers,” bereft of the well-rounded superstars who make admissions officers happy.

At times, “Try Harder!” hints at these larger stories, from the alleged prejudices that top-tier colleges harbor against the perceived machinelike excellence of Asian applicants to the racial politics of San Francisco to the uneven distribution of resources that produce élite public schools like Lowell. In February, local voters recalled three members of the city’s Board of Education, in part to protest their role in a 2021 decision to diversify Lowell by replacing its merit-based admissions system with a lottery. The recall campaign was driven by Asian American voters—many of whom presumably have little interest in following Ninh’s call to rethink paradigms of success. As one parent told the Times , education has “been ingrained in Chinese culture for thousands and thousands of years.”

Lum focusses on these pressures as they trickle down to the students, which makes for a compelling set of dramas. One of the film’s stars is an African American student named Rachael, whose sweet, aggressive modesty leads her to underestimate her own capabilities. There’s a Taiwanese American kid named Alvan who seems happiest in his dance class—only his parents would never understand. His highest and lowest moments alike are commemorated with a dab . These are all students who, in Ninh’s words, “pass for perfect.” The occasional shots of students staring off into the distance convey more than they are capable of articulating as teen-agers.

As the year wears on, they begin to feel the effects of the grind. There’s less energy for all-night study sessions; the tense, feigned smile of the after-school job is harder to maintain. Students begin wondering why they worked so hard in the first place. I want to say that I felt a familiar sense of fear as the admissions letters began rolling in, but, even though I attended a competitive Bay Area high school full of Asian kids, it was nothing like this. There was less to do, yet more possible futures to imagine. “Try Harder!” slowly shifts genres from comedy to horror. You almost stop caring whether anyone will get into their dream school, because you already recognize that we should be encouraging students to dream of something other than school. Yet you desperately want them to get in, for it is the only horizon they have ever known.

New Yorker Favorites

Searching for the cause of a catastrophic plane crash .

The man who spent forty-two years at the Beverly Hills Hotel pool .

Gloria Steinem’s life on the feminist frontier .

Where the Amish go on vacation .

How Colonel Sanders built his Kentucky-fried fortune .

What does procrastination tell us about ourselves ?

Fiction by Patricia Highsmith: “The Trouble with Mrs. Blynn, the Trouble with the World”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By David Remnick

By Rebecca Mead

By Amanda Petrusich

By Jason Adam Katzenstein

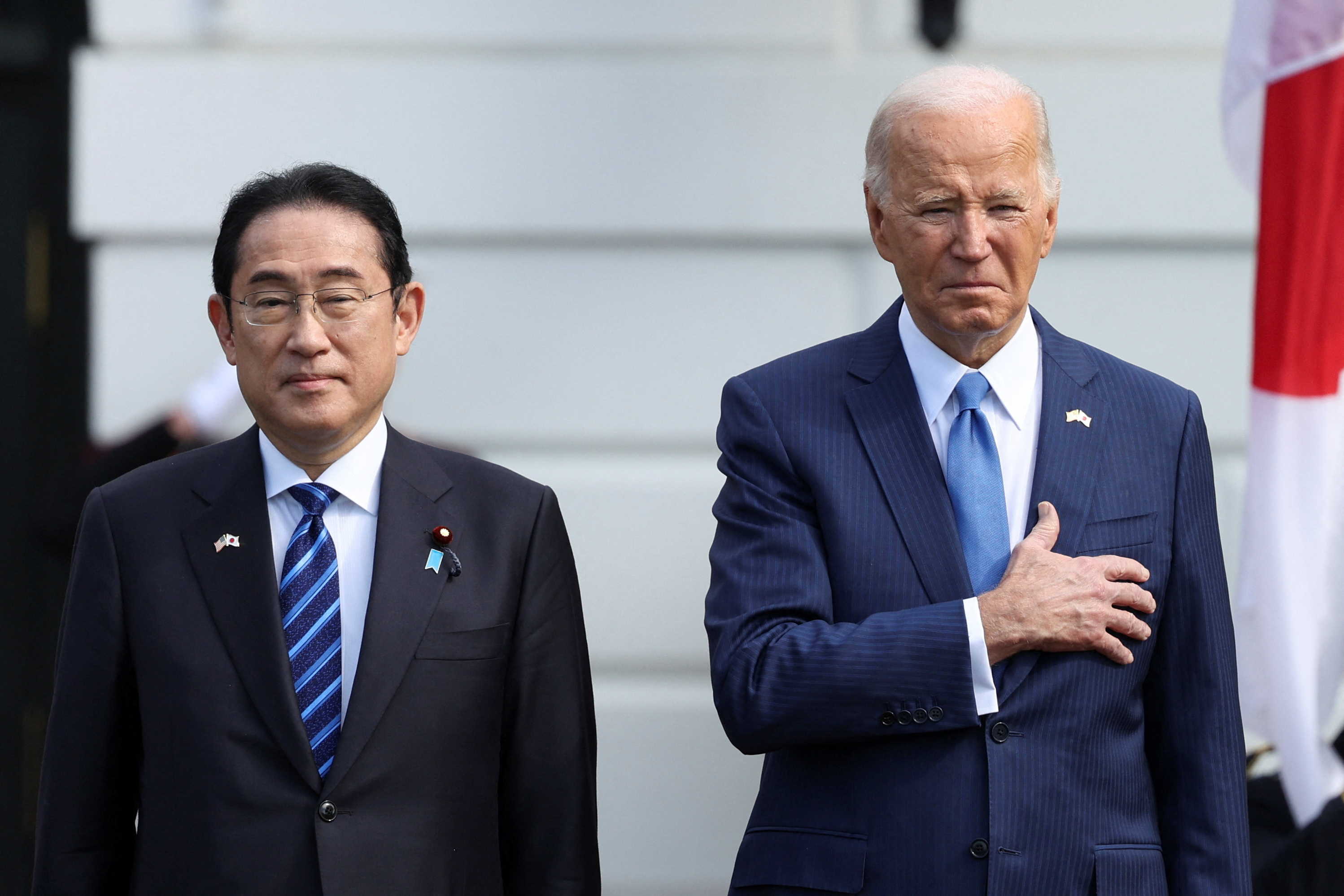

What It Means to Be Asian in America

In the fall of 2021, with support from a Luce Foundation grant, Pew Research Center embarked on a project exploring the experiences and views of Asian Americans, the fastest growing racial or ethnic group in the United States. The focus group study included participants of different languages, immigration or refugee experiences, educational backgrounds, and income levels from across the country and was designed to capture the voices of many ethnic subgroups whose perspectives have not been well-represented in traditional surveys.

Earlier this month, the Center released an interactive report with key takeaways from the study accompanied by a collection of publications that “capture in people’s own words what it means to be Asian in America.”

Reflections from participants revealed common sentiments including:

- A complicated relationship with the pan-ethnic labels “Asian” or “Asian American”

- A disconnect between how they see themselves and how others view them

- The negative impacts of the “model minority myth”

In a Q&A about the study , Neil G. Ruiz, associate director of race and ethnicity research at Pew Research Center, said, “We’re committed to providing a more complete picture of all people who live in the United States...We conducted this project to capture the diverse voices and experiences of Asian Americans and understand what it means to be Asian in America. This study aims to expand the depth and breadth of our understanding of racial and ethnic identity by asking Asian Americans to describe their attitudes and experiences in their own words , without preset response options.”

Read the Data Essay

Watch the Documentary

Explore the project further at Pew Research Center

Interactive quote sorter: In Their Own Words: The Diverse Perspectives of Being Asian in America Expanded interviews: Extended Interviews: Being Asian in America Q&A: Why and how Pew Research Center conducted 66 focus groups with Asian Americans

Related News

- United Kingdom

Coming To Terms With Being Asian American

Why it took me 25 years to come to terms with being asian american.

It was the first time that someone had encapsulated my entire personhood into one word: “Asian.”

Culture has a way of connecting us from the things we have in common to our differences. For #AsianPacificAmericanHeritageMonth we created a space for our voices to be heard and to defy (or embrace) the stereotypes that are placed on Asian Americans. We asked a few Asian Pacific American R29 staffers what their favorite thing about their culture is and discovered that the strings that attach us so closely with our culture are also associated with the memories we make with our families. The act of gathering and creating food brings us together (and something we still defer back to when we're feeling a bit homesick). Comment below with what about your culture brings you ✨joy✨. #APAHM #AcknowledgeIsPower #AsianPacificAmericanHeritageMonth A post shared by Refinery29 (@refinery29) on May 19, 2017 at 10:03am PDT

More from Mind

R29 original series.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Picture Show

Photographer explores asian american identity in 'where we're really from'.

Brothers Hayle (left) and Henry Pham run during a game of football, as their father, Hansel, throws a ball in the air on Jan. 26, 2020. Eric Lee hide caption

Brothers Hayle (left) and Henry Pham run during a game of football, as their father, Hansel, throws a ball in the air on Jan. 26, 2020.

Photographer Eric Lee spent a large part of his childhood struggling to find his place as an Asian American — the constant to and fro between, he says, feeling "too Asian" and "not Asian enough" inspired him to visually deconstruct the complexities of his identity.

In his multimedia project, "Where We're Really From," Lee explores what it's like to grow up Asian American, through the Pham brothers, Henry, 7, and Hayle, 9. The boys are just beginning to understand and peel the layers of being Vietnamese Americans living in Gaithersburg, Md., a mostly white community outside Washington, D.C.

While Lee found his own childhood reflected in several aspects of the boys' upbringing, he also found that the social and political context of the present deeply shape their growth. Their parents, Thu and Hansel Pham, lay emphasis on concepts like consent, nonviolence and healthy masculinity. When Lee, 27, was growing up, his parents didn't necessarily think about these concepts in the conscious manner that the Phams do.

In an interview, Lee describes his background and his experience photographing the Phams, which he did for more than a year. His answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Hayle smiles after blowing out candles at his 7th birthday party on April 28, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

Hayle smiles after blowing out candles at his 7th birthday party on April 28, 2019.

Henry Partain and Henry Pham (front left to right) play on iPads while Hayle Pham and Jack Partain play Nintendo Switch after skiing in Seven Springs, Pa., on Feb.16, 2020. Eric Lee hide caption

Thu Pham, center, encourages Henry, left, and Hayle, as they climb pull-up bars at a park on Chinqoteague Island, Md., on April 14, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

Thu Pham, center, encourages Henry, left, and Hayle, as they climb pull-up bars at a park on Chinqoteague Island, Md., on April 14, 2019.

Artists gravitate to stories that deeply resonate with their own life and experience. What inspired you to start this project?

I attended a predominantly white private school in Brooklyn growing up. I was one of very few Asian Americans in my class and I struggled for years trying to figure out where I fit. I always wanted to learn my history as a Chinese American. In college, I produced a documentary on Asian American masculinity. It was something I thought I understood and I wanted to help uncover the growing problems of many negative stereotypes, like the model minority myth — the perception that one minority group is achieving high success and other racial groups should model after them. But the more people I interviewed and the more I learned, the less I felt ready to tell this story. In 2018, four years after those interviews, I applied to the Corcoran College of Art and Design in Washington, D.C, knowing I wanted to begin exploring my own identity through my lens. I had more questions than ever about identity, but having the dedicated space, resources, and support to be intimate and open comforted me.

Hayle tackles Henry during a game of football Black Hill Regional Park in Boyds, Md., on April 7, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

Hayle tackles Henry during a game of football Black Hill Regional Park in Boyds, Md., on April 7, 2019.

Hayle sulks and walks behind Thu on the High Line in New York City on Jan. 25, 2020. Eric Lee hide caption

Hansel Pham lifts Henry at home on April 5, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

How did you go about building trust with Henry and Hayle? Did you know them beforehand?

I initially put a social media callout when I was searching for a family to document in early 2019. A former colleague put me in touch with the Phams, and they have always been attracted to topics revolving around Asian American identity. Building trust with the children wasn't easy. Early on, I followed their every move, often having to put down the camera and play football or tag before I could take photos. Sometimes they made a game out of leaving the frame when I would point the camera in their direction, but I played along. Knowing that this project would take time, I visited the Phams every few weeks, spending 8-12 hours with them each time.

Hayle lies on his bed after spending the afternoon alone after throwing a tantrum on Oct. 13, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

Hayle lies on his bed after spending the afternoon alone after throwing a tantrum on Oct. 13, 2019.

Hayle and Henry look at instructions while attempting to build a Hot Wheels set in Ocean City, Md., on April 14, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

Hayle and Henry look at instructions while attempting to build a Hot Wheels set in Ocean City, Md., on April 14, 2019.

How would you describe the boys' relationship with one another?

The boys are competitive but they always do whatever they can to support each other. At school, their classrooms share a door with a window. Hayle would peek through it every moment he could to see what Henry was up to. Even while playing or working independently, the brothers liked to keep tabs on each other, even at home. I grew up an only child with parents who worked long hours. Their brotherhood was new to me and didn't fall into the stereotypical brotherhood of teasing and bullying. The pair truly worked as a team, even when they were on different teams during football and other games. Henry gave Hayle a head start before races and gave him hints on how to win the game.

Hayle eats a corndog as Henry stacks oyster crackers on his head at Clyde's Tower Oaks Lodge in Rockville, Md., on Sept. 29, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

Hayle eats a corndog as Henry stacks oyster crackers on his head at Clyde's Tower Oaks Lodge in Rockville, Md., on Sept. 29, 2019.

How do the boys talk about their identity?

In October 2018, I went to one of Henry's swim meets in Virginia. One conversation with Hayle struck me in particular. He lifted his index finger to his chin, as he always does when he focuses a thought.

"You know, there are only two Asian kids in my class," he says, still with his finger on his chin. He turns towards me. By then I'd been around Hayle for about seven months, photographing and observing. While he's talked about being Asian with Thu and Hansel before, he and I have never had a conversation about it.

Thu drops in dumplings for Lunar New Year celebrations as Hayle checks on the pot of boiling water on Jan. 26, 2020. Eric Lee hide caption

Thu drops in dumplings for Lunar New Year celebrations as Hayle checks on the pot of boiling water on Jan. 26, 2020.

"There's me and Taiji. He speaks Japanese to his parents sometimes."I nod. He then tells me that his parents are Vietnamese, while continuing to fiddle with his fingers. "Do you like being Vietnamese?" I ask trying to keep his attention on the topic as a new race begins behind him. "I don't know, it's kind of weird," he says."Why is it weird?" "I don't know," pauses Hayle. "I guess I don't get sunburnt though!"

I was surprised by this conversation since it was the first time one of the boys acknowledged race and ethnicity without a prompt. It made me wonder how much they thought about being Asian American and how it affected their life. It's certainly made me more aware of who I am.

Thao Nguyen gives her nephew, Hayle, a red envelope in celebration of the Lunar New year on Jan. 26, 2020. Eric Lee hide caption

Thao Nguyen gives her nephew, Hayle, a red envelope in celebration of the Lunar New year on Jan. 26, 2020.

Is there one experience or instance from this project that stands out to you?

Earlier this year, I celebrated the Lunar New Year with the Phams.Thao and Nguyen, the boys' aunt and uncle, came from Baltimore to celebrate. As we ate at the table, Hansel began asking the boys if they knew the history of the traditions they were doing. The boys replied with half-hearted answers as they ate the meal of sautéed beef and wonton soup. This conversation sparked a moment of deja vu for me. I remember doing the same thing, replying to my parents' questions about the Lunar New year with my mouth full.

After dinner, Thao called the boys. She and Nguyen pulled out red envelopes filled with money. The red envelopes are signs of good luck and fortune and are often given to children to celebrate the New Year. Watching the boys take their red envelopes with both hands and wish their aunt and uncle "happy new year" froze me again. I always saw myself in Henry and Hayle's life, but this night solidified that feeling for me, seeing how another Asian American family celebrated traditions just like mine did.

Henry watches his friends play football at Hayle's birthday on April 28, 2019 in Darnestown, Md. Eric Lee hide caption

Henry watches his friends play football at Hayle's birthday on April 28, 2019 in Darnestown, Md.

What were some of the differences you saw between your upbringing and that of Henry and Hayle?

Thu and Hansel are presented with different challenges than my parents were two decades ago, like school shootings, racism and COVID-19, and the #MeToo movement. I don't think my parents ever thought about them in such an intentional way that parents nowadays have to. Henry and Hayle had an active shooter drill at school one day, something I never experienced. Hansel likes to tell a story about them seeing Spider Man: Into the Spider-Verse , and having to leave halfway through because it was too scary and violent for the boys. He jokingly vowed to never take them to the movies ever again.

Thu and Hansel don't try to push being "masculine" on the brothers. They can pick out their own clothing, toys, and activities — except contact football, which isn't allowed at all. After Hayle and Henry's karate belt test on a Saturday afternoon, Thu took them to an Asian food hall for lunch. They were eating lunch when Henry brought up that someone tried to hug him in class. This alarmed Thu, and she began a discussion about consent.

Henry pushes a wheel as Hayle sits on it in a park in Chincoteague, Md., on April 14, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

Henry pushes a wheel as Hayle sits on it in a park in Chincoteague, Md., on April 14, 2019.

What was the most challenging part of the project?

I began the project searching to understand what Asian American boyhood meant in terms of topics like identity, masculinity and family. These are hard topics to photograph as they're not always obvious. As I continued to make work, I made sure I kept the history in mind. The most challenging element of this project was learning all the background and figuring out how to convey the nuance of identity.

Thu helps Hayle pick up a box of Asian pears at a grocery store in Eden Center in Falls Church, Va., on Oct. 12, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

Thu helps Hayle pick up a box of Asian pears at a grocery store in Eden Center in Falls Church, Va., on Oct. 12, 2019.

Henry reaches for a strawberry Ramune, a Japanese soda-like drink at a grocery store in Eden Center in Falls Church, Va., on Oct. 12, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

Henry reaches for a strawberry Ramune, a Japanese soda-like drink at a grocery store in Eden Center in Falls Church, Va., on Oct. 12, 2019.

Did you learn new things about your own layered identity through this journey ?

During the project, I asked myself what it meant to be Asian American? I questioned if it was food, culture, family or solely based on what I looked like. It left me with more questions than answers.

Teased for not knowing English, my father embraced becoming American, both culturally and nationally. He played stickball in the streets, rode American-made motorcycles and often visited the American countryside. For him, the cons of being Asian American outweighed the pros.

Raising me without the "immigrant mentality" was a defense mechanism for him, and a way to protect me from the trauma he experienced.

After working on this project, I am coming to understand why my parents raised me the way they did. I'm finally seeing that they were raising me in a way that didn't have the same pain and sufferings they endured. It's taken me 27 years to finally understand my parents.

An eight-image panorama of the Phams in Ocean City, Md., on April 13, 2019. Eric Lee hide caption

An eight-image panorama of the Phams in Ocean City, Md., on April 13, 2019.

- Asian American

Advertisement

The Anxiety of Being Asian American: Hate Crimes and Negative Biases During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Published: 10 June 2020

- Volume 45 , pages 636–646, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Hannah Tessler 1 ,

- Meera Choi 1 &

- Grace Kao 1

78k Accesses

242 Citations

107 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In this essay, we review how the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic that began in the United States in early 2020 has elevated the risks of Asian Americans to hate crimes and Asian American businesses to vandalism. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidents of negative bias and microaggressions against Asian Americans have also increased. COVID-19 is directly linked to China, not just in terms of the origins of the disease, but also in the coverage of it. Because Asian Americans have historically been viewed as perpetually foreign no matter how long they have lived in the United States, we posit that it has been relatively easy for people to treat Chinese or Asian Americans as the physical embodiment of foreignness and disease. We examine the historical antecedents that link Asian Americans to infectious diseases. Finally, we contemplate the possibility that these experiences will lead to a reinvigoration of a panethnic Asian American identity and social movement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Anti-Asian Hate Crime During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring the Reproduction of Inequality

Angela R. Gover, Shannon B. Harper & Lynn Langton

Anti-vaccine rabbit hole leads to political representation: the case of Twitter in Japan

Fujio Toriumi, Takeshi Sakaki, … Mitsuo Yoshida

Writing biography in the face of cultural trauma: Nazi descent and the management of spoiled identities

Joachim J. Savelsberg

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

COVID-19 (or the coronavirus) is a global pandemic that has affected the everyday lives of hundreds of millions of people. At the time we write this, there have been over four million cases across over 200 countries worldwide (Pettersson, Manley, & Hern, 2020 ) . Moreover, pervasive stay-at-home orders and calls for social distancing, as well as the disruptions to every facet of our lives make it difficult to overstate the importance of COVID-19. As the beginning of the outbreak has been traced to China (and Wuhan in particular), both in the United States and elsewhere, people who are Chinese or seen as East Asian have become associated with this contagious disease. Early reports in the United States were often accompanied by stock photos of Asians in masks (Burton, 2020 ; Walker, 2020 ). Many of the first reports labeled the disease as the “Wuhan Virus,” or “Chinese Virus,” and the Trump administration has also used these terms (Levenson, 2020 ; Maitra, 2020 ; Marquardt & Hansler, 2020 ; Rogers, Jakes, & Swanson, 2020 ; Schwartz, 2020 ). News media coverage in the United States focused on the hygiene of the seafood market in Wuhan and wild animal consumption as a possible cause of coronavirus (Gomera, 2020 ; Mackenzie & Smith, 2020 ). Memes and jokes about bats and China flooded social media, including posts by our peers online. These reports provide the American public a straightforward narrative that focuses on China as the origin of COVID-19.

In this paper, we review current patterns of hate crimes, microaggressions, and other negative responses against Asian individuals and businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic. These hate crimes and bias incidents occur in the landscape of American racism in which Asian Americans are seen as the embodiment of China and potential carriers of COVID-19, regardless of their ethnicity or generational status. We believe that Asian Americans not only are not “honorary whites,” but their very status as Americans is, at best, precarious, and at worst, in doubt during the COVID-19 crisis. We suggest that what we witness today is an extension of the history of Asians in the United States and that this experience may lead to the reemergence of a vibrant panethnic Asian American identity.

Hate Crimes Against Asian Americans During COVID-19

As of early May 2020, there have been over 1.8 million individuals who have tested positive for and over 105,000 deaths from COVID-19 in the United States alone and the numbers are growing rapidly every day (“Cases in the U.S.,” 2020 ). Although researchers have traced cases of the virus in the United States to travelers from Europe (Gonzalez-Reiche et al., 2020 ) and to travelers within the United States (Fauver et al., 2020 ), some members of the general public regard Asian Americans with suspicion and as carriers of the disease. On April 28th, 2020, NBC News reported that 30% of Americans have personally witnessed someone blaming Asians for the coronavirus (Ellerbeck, 2020 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the negative perceptions of Asian Americans that have long been prevalent in American society. Many individuals in the United States see the virus as foreign and condemn phenotypically Asian bodies as the spreaders of the virus (Ellerbeck, 2020 ). Consistent with Claire Jean Kim’s theory on racial triangulation (Kim, 1999 ) and the concept of Asians as perpetual foreigners (Ancheta, 2006 ; Saito, 1997 ; Tuan, 1998 ; E. D. Wu, 2015 ) , we posit that during COVID-19, the racial positionality of Asian Americans as foreign and Other persists, and that this pernicious designation may be a threat to the safety and mental health of Asian Americans. They are not only at risk of exposure to COVID-19, but they must contend with the additional risk of victimization, which may increase their anxiety. Historically, from the late 19th through the mid twentieth century, popular culture and news media portrayed Asians in America as the “Yellow Peril,” which symbolized the Western fear of uncivilized, nonwhite Asian invasion and domination (Okihiro, 2014 ; Saito, 1997 ) . It is possible that the perceived threat of the Yellow Peril has reemerged in the time of COVID-19.

The spread of the coronavirus and the increased severity of the pandemic has caused fear and panic for most Americans, as COVID-19 has brought about physical restrictions and financial hardships. So far, forty-two states have issued stay-at-home orders, which has resulted in 95% of the American population facing restrictions that impact their daily lives (Woodward, 2020 ). Novel efforts to end the pandemic across the states have led businesses to shut down. As a result, more than 30 million people in the United States have filed for unemployment since the onset of the coronavirus crisis (Gura, 2020 ). Because this virus has been identified as foreign, for some individuals, their feelings have been expressed as xenophobia, prejudice, and violence against Asian Americans. These negative perceptions and actions have gained traction due to the unprecedented impact COVID-19 has on people’s lives, and institutions such as UC Berkeley have even normalized these reactions (Chiu, 2020 ). However, racism and xenophobia are not a “natural” reaction to the threat of the virus; rather, we speculate that the historical legacies of whiteness and citizenship have produced these reactions, where many individuals may interpret Asian Americans as foreign and presenting a higher risk of transmission of the disease.

Already, the FBI has issued a warning that due to COVID-19, there may be increased hate crimes against Asian Americans, because “a portion of the US public will associate COVID-19 with China and Asian American populations” (Margolin, 2020 ). News reports, police departments, and community organizations have been documenting these incidents. Evidence suggests that the FBI’s warning was warranted. Based on reporting from Stop AAPI Hate , in the one-month period from March 19th to April 23rd, there were nearly 1500 alleged instances of anti-Asian bias (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ). The reported incidents have been concentrated in New York and California, with 42% of the reports hailing from California and 17% of reports from New York, but Asian Americans in 45 states across the nation have reported incidents (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ).

Reports of Hate Crimes and Bias Incidents

There have been a large number of physical assaults against Asian Americans and ethnically Asian individuals in the United States directly related to COVID-19. While the majority of Americans are sheltering-in-place and staying at home, 80% of the self-reported anti-Asian incidents have taken place outside people’s private residences, in grocery stores, local businesses, and public places (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ). We suggest that these hate crimes and other incidents of bias have historical roots that have placed Asians outside the boundaries of whiteness and American citizenship. In addition, we believe that the current COVID-19 crisis draws attention to ongoing racial issues and provides a lens through which to challenge the notion of America as a post-racial society (Bonilla-Silva, 2006 ).

One of the incidents under investigation as a hate crime includes the attempted murder of a Burmese-American family at a Sam’s Club in Midland, Texas (Yam, 2020a ). The suspect said that he stabbed the father, a four-year-old child, and a two-year-old child because he “thought the family was Chinese, and infecting people with coronavirus” (Yam, 2020a ). Police are investigating numerous other physical incidents including attacks with acid (Moore & Cassady, 2020 ), an umbrella (Madani, 2020 ), and a log (Kang, 2020 ). There have been a number of physical altercations at bus stops (Bensimon, 2020 ; Madani, 2020 ), subway stations (Parnell, 2020 ), convenience stores (Oliveira, 2020 ), and on the street (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ; Sheldon, 2020 ). Asian Americans are also reporting physical threats being made against them (Driscoll, 2020 ; Parascandola, 2020 ). Based on Stop AAPI Hate statistics, 127 Asian Americans filed reports of physical assaults in four weeks (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ), and it is likely that other Asians have not reported their experiences out of fear or concern about the legal process.

In addition to the physical attacks and threats against Asian Americans, individuals have also filed reports of vandalism and property damage targeted at Asian businesses. One Korean restaurant in New York City had the graffiti “stop eating dogs” written on its window (Adams, 2020 ). Perpetrators have also made explicit references to COVID-19 in their vandalism, where phrases such as “take the corona back you ch*nk” (Goodell & Mann, 2020 ), and “watch out for corona” (Wang, 2020 ) have been documented on Asian-owned restaurants. Some of these incidents were not reported to the police and therefore will not be investigated as hate crimes, as business owners reasoned that it would be difficult to track the vandals (Adams, 2020 ; Buscher, 2020 ). These incidents of vandalism demonstrate the association some people make between Asian American businesses and COVID-19.

Beyond the narrow definition of the incidents that can be classified as punishable hate crimes, Asian Americans have also documented a large number of alleged bias and hate incidents. Stop AAPI Hate reports indicate that 70% of coronavirus discrimination against Asian Americans has involved verbal harassment, with over 1000 incidents of verbal harassment reported in just four weeks (Jeung & Nham, 2020 ). In addition, there have been over 90 reports of Asian Americans being coughed or spat on. One prevalent theme in the verbal incidents is the linking of Asian bodies to COVID-19, where the aggressors are purportedly calling Asians “coronavirus,” “Chinese virus,” or “diseased,” and telling them that they should “be quarantined,” or “go back to China” (ADL 2020 ). In all of these incidents, the perpetrators consistently use anti-Asian racial slurs (Buscher, 2020 ; Goodell & Mann, 2020 ; Sheldon, 2020 ). This hateful language that targets all Asians (and not just Chinese Americans) demonstrates the racialization of Asian Americans.

The threat of a global pandemic to people’s everyday lives is something that most Americans have not experienced before. However, the act of interpreting the current national crisis as an external threat and ascribing this danger to Chinese bodies and more broadly Asian bodies should not surprise scholars of Asian Americans. In fact, this deeply-rooted cognitive association of Asian Americans to Asia and to disease has a long history. Hence, we examine the phenomenon of xenophobia against Asian Americans in the context of historical racial dynamics in the United States.

The Color Line and the Positionality of Asian Americans

Race has been posited as a socio-historical concept, and while many race scholars in the United States have focused on the black/white binary, others have documented how Asian Americans have also been racialized over time (Omi & Winant, 2014 ). These scholars have examined how the racialization of Asian Americans has developed in relation to African Americans and white Americans (Bonilla-Silva, 2004 ; Kim, 1999 ). One of the dominant stereotypes of Asian Americans is that they are perpetual foreigners , where individuals directly link phenotypical Asian ethnic appearance with foreignness, regardless of Asian immigrant or generational status (Ancheta, 2006 ; Tuan, 1998 ; F. H. Wu, 2002 ). This stereotype is longstanding in American history and has forcefully re-emerged during the COVID-19 crisis. The perception of an Asian-looking person as simultaneously Chinese, Asian, and foreign underscores how this racial categorization affects all Asian Americans. Thus, we suggest that the concept of Asian American panethnicity (Okamoto & Mora, 2014 ) may be particularly applicable during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The legacy of white supremacy equates white bodies with purity and innocence, while nonwhite bodies are designated as unclean, uncivilized, and dangerous. White supremacy and its tactic of othering Asian bodies has been a consistent recurrence over earlier pandemics. Dating back to the nineteenth century, the bubonic plague was framed as a “racial disease” which only Asian bodies could be infected by whereas white bodies were seen as immune (Randall, 2019 ). In 1899, Honolulu officials quarantined and burned Chinatown as a precaution against the bubonic plague (Mohr, 2004 ). In 1900, San Francisco authorities quarantined Chinatown residents, and regulated food and people in and out of Chinatown, believing that the unclean food and Asian people were the cause of the epidemic (Shah, 2001 ; Trauner, 1978 ). The history of the Yellow Peril has continued throughout the 20th and 21st centuries in the embodied perceptions of Asian immigrants as the spreaders of disease (Molina, 2006 ).

More recently, during the 2003 SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic, the discourse in the United States focused on Chinatown as the epicenter of the disease (Eichelberger, 2007 ). Studies suggest that 14 % of Americans reported avoiding Asian businesses and Asian Americans experienced increased threat and anxiety during SARS (Blendon, Benson, DesRoches, Raleigh, & Taylor-Clark, 2004 ). We suspect the negative impact of COVID-19 on Asian Americans has been far greater than the impact of SARS. In New York City’s Chinatown, restaurants suffered immediately after the first reports of COVID-19, as some restaurants and businesses experienced up to an 85% drop in profits for the two months prior to March 16th, 2020 – far before any stay-at-home orders were given (Roberts, 2020 ). When moral panic arises, foreign bodies, typically the undesirable and “un-American” yellow bodies, may be seen as a threat that can harm pure white bodies.

The cycle of elevated risk, followed by fearing and blaming what is foreign is not just limited to disease outbreaks, but also occurs during economic downturns. In 1982, Vincent Chin was beaten to death by two men who blamed him for the influx of Japanese cars into the United States auto market. Vincent Chin was attacked with racial slurs and specifically targeted because of his race. Although Chin was Chinese American, in the minds of these two men, he represented the downturn of the auto industry in Detroit and the increased imports of Japanese automobiles (Choy & Tajima-Pena, 1987 ).

Similarly, after the 9/11 attacks in the United States, retaliatory aggressions were not limited to attacks against Arabs or Muslims (Perry, 2003 ). Violence and hatred against the perceived enemy resulted in incidents targeting Sikhs, second and third generation Indian Americans, and even Lebanese and Greeks (Perry, 2003 ). More recently, the hate crime murder of Srinivas Kuchibhotla, an Indian immigrant falsely assumed to be an Iranian terrorist and told “get out of my country” before being shot to death, illustrates the association between racialized perceptions of threat and incidents of violence (Fuchs 2018 ). With the COVID-19 pandemic, violent attacks and racial discrimination against Asian Americans have emerged as non-Asian Americans look for someone or something Asian to blame for their anger and fear about illness, economic insecurity, and stay-at-home orders.

Fear and the Mental Health of Asian Americans

The current perceptions of China and more broadly East Asia as both economic and public health threats have made Chinese and East Asians in America fearful for their own safety. Some Asian Americans have made efforts to hide their Asian identity or assert their status as American in an attempt to prevent hate crime attacks (Buscher, 2020 ; Tang, 2020 ). While this tactic may be effective on the individual level, it does not modify the positionality of Asian bodies during COVID-19. The attempt to distinguish Asian Americans from Asians who are foreign nationals misses the fact that in the United States, being Asians and being foreign are inextricably bound together.

After World War II, news media and local organizations encouraged Chinese Americans to distinguish themselves from the Japanese, and similarly encouraged Japanese Americans to show their Americanness and patriotism to gain acceptance by the white majority (E. D. Wu, 2015 ). Muslim and Sikh Americans displayed American flags after 9/11 to show that they were not a threat to the United States, and more recently there has been a movement to celebrate Sikh Captain America (Ishisaka, 2018 ). Former presidential candidate Andrew Yang suggested that Asian Americans fight against racism by wearing red white and blue and prominently displaying their Americanness (Yang, 2020 ). In many of these situations, these strategies did not directly address the problems of racism and xenophobia – they simply shifted the blame towards another group.

Disease does not differentiate among people based on skin color or national origin, yet many Asian Americans have suffered from discrimination and hatred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the threat of the virus is real for all Americans, Asian Americans bear the additional burden of feeling unsafe and vulnerable to attack by others. The link between COVID-19 and hate crimes and bias incidents against Asian Americans is indicative of the widespread racial sentiments which continue to be prominent in American society. While some scholars have gone as far as to regard Asian Americans as “honorary whites” (Tuan, 1998 ), the current COVID-19 crisis has made markedly clear this is an illusion, at best. There are a number of reasons why the racial dynamics of anti-Asian crimes during COVID-19 should be examined more closely.

First, the majority of incidents and attacks have occurred in diverse metropolitan areas such as New York City, Boston, and Los Angeles. These are spaces that most Americans have traditionally regarded as more liberal and tolerant of difference than other parts of the United States. In New York City alone, from the start of the COVID-19 outbreak through April 2020, the NYPD’s hate crime task force has investigated fourteen cases where all the victims were Asian and targeted due to coronavirus discrimination (NYPD, 2020 ). The remarks of a Kansas governor that said his town was safe “because it had only a few Chinese residents” (Lefler & Heying 2020 ) offers one explanation for the high concentration of racial incidents in large cities with sizable Asian populations, but we think that this is not sufficient in explaining the data so far. Future research should track racial bias and hate crimes more systematically in order to further our understanding of how demography and urbanicity influence these incidents.

Second, these hate crimes have increased the anxiety of Asian Americans during already uncertain times, with many fearful for their physical safety when running everyday errands (Tavernise & Oppel Jr., 2020 ). Asian Americans are now self-conscious about “coughing while Asian” (Aratani, 2020 ), and concerned about being targeted for hate crimes (Liu, 2020 ; Wong, 2020 ). There is evidence to suggest that Asian Americans under-report crimes (Allport, 1993 ), and some recent immigrants may lack an understanding of the legal system and process of reporting crimes, particularly in the case of hate crimes. Therefore, scholars should take additional care to document and analyze these incidents and their effects on Asian American communities across the United States.