My Speech Class

Public Speaking Tips & Speech Topics

How to Write a 500-Word Essay – Guide & Examples

Jim Peterson has over 20 years experience on speech writing. He wrote over 300 free speech topic ideas and how-to guides for any kind of public speaking and speech writing assignments at My Speech Class.

Five hundred words may not sound much. But when you have little to no knowledge of a topic, it isn’t easy to even reach 100 words. So how do you get 500 on your word count?

Keep reading for my step-by-step guide on how to write a 500-word essay easily. These tips will increase your chance of obtaining a perfect score, getting a scholarship, or convincing your readers to do something.

What Is a 500-Word Essay?

A 500-word essay is a piece of writing considered a common requirement among students. This paper usually has three parts: an introductory statement or thesis statement, a body paragraph, and a conclusion.

The 500-word essay format may have a consistent structure. But the types of essays vary according to the subject matter or requirement. You may be required to present an argument, describe a phenomenon, or recall an event.

Producing a 500-word essay is easy if you know the requirements and have enough writing skills. Exceptional techniques ensure that all sentences are coherent and essential to the entire paper.

500-Word Paper Essay Types

Your essay type will depend on the requirements and overall theme of the paper. For instance, you can write argumentative essays for your political science class or a scholarship essay when applying for college. Here are the most common essay types you’ll encounter.

Narrative Essay

A narrative essay tells a story about different things. It can be a college essay telling your life story or personal experiences. It can also be an effective essay that requires creativity and imagination.

Can We Write Your Speech?

Get your audience blown away with help from a professional speechwriter. Free proofreading and copy-editing included.

Narrative essays also follow the basic structure of an essay. But it would help if you used literary techniques in this essay type, such as metaphors, analogies, imagery, and metaphors.

Descriptive Essay

A descriptive essay is a concise paper that offers a detailed description of a certain topic. You might describe a past event, place, object, or scientific method. Descriptive essays should also have an exceptional essay flow to show a complete and understandable explanation.

Argumentative Essay

Argumentative essays require analytical skills because you must take a side on a particular topic. You need to base your paper on facts rather than emotion. For example, your argumentative essay can be about being for or against a new policy.

Persuasive Essay

A persuasive essay aims to convince readers to side with your opinion or do something. Writing essays of this kind requires both emotional appeal and facts.

For example, your persuasive essay can be a letter to your parents telling them why they should buy you a new gadget.

How to Format a 500-Word Piece

A 500-word writing piece should have this format to ensure that the arguments are clear to the reader.

Introduction Paragraph

- Hook statement

- Background details

- Compelling thesis statement

Body Paragraphs

- Essay topic sentence

- Supporting details

- Concluding sentence

- Restate the thesis statement

- Summarized key points

- Final thought

How to Write a 500-Word Essay

Now let’s look at this step-by-step guide to making a 500-word essay.

Create an Outline

The first thing to writing an excellent essay is to create an outline. This will allow you to plan every element of your paper using the common structure. Creating an outline is also easy if an essay prompt is already provided.

One common mistake among essay writers is not making a list for the outline. Use bullet points to make the entire plan simple and organized, from the introduction to the conclusion. Here’s a basic example of an outline for an essay about why we should read more books.

Introduction

- Hook statement: Have you ever felt stressed, lonely, or depressed?

- Background details: 73% of people have stress that impacts their mental health.

- Thesis statement: Individuals should read more books to improve their mental health.

Body Paragraph 1

- Essay topic sentence: Reading allows you to wind down before bedtime.

- The mind races before bedtime.

- Importance of putting down the phone before bedtime.

- Physical books are better than e-books when reading at night.

- Concluding sentence: Read a physical book at least one hour before bedtime.

Body Paragraph 2

- Essay topic sentence: Reading makes humans more understanding.

- Research states that literary fiction improves a reader’s capacity to think and feel.

- When we read about similar experiences, we feel less alone.

- Concluding sentence: Read fictional novels and short stories to improve your empathy.

Body Paragraph 3

- Essay topic sentence: Reading improves your focus and overall brain function.

- Thinking and imagining make your brain stronger.

- Following words builds your memory.

- Concluding sentence: Start reading any genre to improve your concentration.

- Restate thesis statement: Individuals should read more books to improve their mental health.

- Summarized key points: Reading helps you wind down before bedtime, makes you more understanding, and improves your focus.

- Final thought: Suggestions on where to buy inexpensive books in town.

Write a Good Introduction

Once you have an outline, writing a good introduction should be a breeze. Since it’s the first part of the essay, take it as an opportunity to grab the attention of readers. Depending on your target audience, it can be through a joke, statistics, or personal anecdote.

An amazing essay should not have a long introduction. For a 500-word essay task, the standard requirement for an intro is about 3-5 brief sentences. Aside from the hook statement or background, this section should include your thesis statement or main point.

Example: “Have you ever felt highly stressed or depressed that you struggled to find a coping mechanism? If you do, you may be one of the 73% of Americans whose stress impacts their mental health. One way to battle mental health problems is by reading.”

Compose the Body Paragraphs

Once you’re done with the hook introduction, it’s time to compose the body. This includes your arguments, supporting details, and possible counterarguments against your claim. The key to writing a compelling essay is to start with the topic sentence.

To make your essay more organized, divide the body paragraphs into the number of arguments you have. Since we have three points to make in our essay, we should compose a 3-paragraph body with around 100-150 words each.

Creating the body paragraph can be a challenging task. So, re-examine your main point of view and present solid facts. You can also appeal to your reader’s emotions or show off your creative writing skills, depending on your essay type.

Below is an example body paragraph for “Reading improves your focus and overall brain function.”

“Reading also improves your focus and overall brain function. Studies show that reading stimulates a human being’s part of the brain responsible for concentration, decision-making, and attention called the prefrontal cortex. No matter the genre of the book, reading can enhance brain connectivity and increase one’s attention span. Reading also improves your memory and vocabulary due to the new neurons being produced in the brain. It is a helpful pastime for students who need to study several hours a day or aging individuals who do not want their cognitive abilities to decline. You don’t need to consume technical non-fiction to improve your brain function. Pick up any book that sparks your interest to have great focus and memory.”

Draft a Compelling Conclusion

The biggest mistake you can make when writing an essay is forgetting the conclusion. The conclusion is one of the key elements for tying everything together and reaffirming your essay question.

A 3000-word essay may include additional key elements in the conclusion, such as recommendations for future research. However, classic essay writing treats the conclusion as a cohesive element that merely summarizes everything.

Professional essay writers repeat the thesis statement and present general conclusions in this section.

“Individuals should read to improve their mental health. Reading physical books, especially before bedtime, helps you wind down and escape from different stressors. Literary fiction improves a person’s ability to understand or empathize with others. Lastly, this activity enhances one’s focus and memory. Therefore, it’s best to read physical books, primarily literary fiction, before bedtime to enhance one’s overall mental health and well-being. Go to the nearest bookstore at Oak Lane now and pick any book that interests you.”

Tips for Writing a Great 500-Word Essay

Writing a 500-word essay may get complicated if you do not follow these tips.

Understand the Requirements

Reading and following instructions from your professor can make essay writing a simple task. Usually, the instructor provides an essay question you should answer, a topic, or a theme.

But if you are free to write about anything, your choice of theme must appeal to their interest. Understanding the requirements will also give you an idea of your audience. It will help you decide on the style and form of your writing.

The requirements also include the standard format of the paper. Aside from the essay length, you will be asked to write using a specific font, usually Times New Roman. Check whether you need to use single spaces or double spaces.

Once you know the essay format and other requirements, it’s time to brainstorm the essay content. For many college students, this step takes the longest time. In fact, starting an essay from scratch involves a longer brainstorming process than the writing process.

Think of exciting ideas that will allow you to craft a perfect essay. Write all your ideas down, then filter them in the next stage. You can also try freewriting to determine whether a topic is worth pursuing.

Some visual learners prefer drawing a map of ideas instead of lists. Break down big ideas into smaller ones. For example, if your teacher asks you to write about the different aspects of your life, reflect on what you will include in your social, family, and academic life.

Refrain from pressuring yourself at this stage because brainstorming does not require you to plan the entire essay. Consider it a baby step to deciding on your topic and creating an outline.

Once you know the standard essay format and have an awesome theme for your 500-word writing piece, it’s time to do some research. If you’re a college or university student, you must already have some sort of experience with this task.

Refrain from being swayed by a single source. Otherwise, you’ll end up being biased or copying this paper. Have sufficient background knowledge about the topic, then learn how to take a critical approach.

Cite Your Sources

College papers or any academic essay will require you to cite sources to check which parts of your paper are original. Having a space for your list of references also lets your readers know that your piece is reliable.

Check the requirements on the citation style you should use. It could be MLA, APA, Chicago, CSE, or Turabian.

Make Sure to Edit and Proofread Several Times

Even if you have a concise piece, it helps to perform several rounds of edits on your work before submitting it. Keep it free from confusing sentences, grammar errors, and typos. You also want to ensure your citations are correct, especially when paraphrasing or quoting.

Have Someone Read Your Essay

An expert who offers essay writing services might help you create an attention-grabbing piece. The work of an editor goes beyond correcting writing mistakes. They allow you to see gaps in your arguments, evaluate your target audience, and teach proper formatting.

Take Breaks

Sometimes, we lose objectivity and creativity when we work too much on the same piece. Taking a break lets you return to work with a fresh mind and a better perspective.

Get enough sleep and go out. Instead of living inside your head, observe your environment and take inspiration from it.

You can also take breaks by reading. Evaluate how an author has caught your attention and see what methods you can imitate from them.

500-Word Essay Topics

Here are some essay examples you might consider as topics for your next paper.

- Admissions essay

- Scholarship applications

- Essay on honesty

- Leadership essay

- What is love?

- Building your online presence

- The pros and cons of homeschooling

- My summer vacation

- Importance of sports

- Festivals in my country

- What is religion?

- What is an ideal student?

- How to save water

How Many Paragraphs Are in a 500-Word Essay?

It depends on the requirement. But essays should always have one paragraph for the introduction and another for the conclusion. Standard outlines require three paragraphs for the body, giving you a total of five paragraphs.

How Many Pages Is a 500-Word Essay?

It depends on your font style, size, and spacing. A 500-word essay can fit on one page if you use single spaces. But if you use double spaces, you will need about 1.5 pages.

How Long Should It Take to Write a 500-Word Essay?

The time it takes to write a 500-word essay depends on your writing skills. But you must allot at least two days to complete the task.

Become a Better Essay Writer

This comprehensive guide revealed all the secrets you need to write a 500-word essay. A 500-word piece should be long enough to fit all your ideas and short enough not to make you feel tired after writing.

Allot two days for brainstorming, outlining, writing, and editing. Don’t forget to take quick breaks and continue researching your topic.

How To Write A Thematic Statement with Examples

Cheat-Sheet of 100 Psychology Research Topics

Leave a Comment

I accept the Privacy Policy

Reach out to us for sponsorship opportunities

Vivamus integer non suscipit taciti mus etiam at primis tempor sagittis euismod libero facilisi.

© 2024 My Speech Class

Speaking versus Writing

The pen is mightier than the spoken word. or is it.

Josef Essberger

The purpose of all language is to communicate - that is, to move thoughts or information from one person to another person.

There are always at least two people in any communication. To communicate, one person must put something "out" and another person must take something "in". We call this "output" (>>>) and "input" (<<<).

- I speak to you (OUTPUT: my thoughts go OUT of my head).

- You listen to me (INPUT: my thoughts go INto your head).

- You write to me (OUTPUT: your thoughts go OUT of your head).

- I read your words (INPUT: your thoughts go INto my head).

So language consists of four "skills": two for output (speaking and writing); and two for input (listening and reading. We can say this another way - two of the skills are for "spoken" communication and two of the skills are for "written" communication:

Spoken: >>> Speaking - mouth <<< Listening - ear

Written: >>> Writing - hand <<< Reading - eye

What are the differences between Spoken and Written English? Are there advantages and disadvantages for each form of communication?

When we learn our own (native) language, learning to speak comes before learning to write. In fact, we learn to speak almost automatically. It is natural. But somebody must teach us to write. It is not natural. In one sense, speaking is the "real" language and writing is only a representation of speaking. However, for centuries, people have regarded writing as superior to speaking. It has a higher "status". This is perhaps because in the past almost everybody could speak but only a few people could write. But as we shall see, modern influences are changing the relative status of speaking and writing.

Differences in Structure and Style

We usually write with correct grammar and in a structured way. We organize what we write into sentences and paragraphs. We do not usually use contractions in writing (though if we want to appear very friendly, then we do sometimes use contractions in writing because this is more like speaking.) We use more formal vocabulary in writing (for example, we might write "the car exploded" but say "the car blew up") and we do not usually use slang. In writing, we must use punctuation marks like commas and question marks (as a symbolic way of representing things like pauses or tone of voice in speaking).

We usually speak in a much less formal, less structured way. We do not always use full sentences and correct grammar. The vocabulary that we use is more familiar and may include slang. We usually speak in a spontaneous way, without preparation, so we have to make up what we say as we go. This means that we often repeat ourselves or go off the subject. However, when we speak, other aspects are present that are not present in writing, such as facial expression or tone of voice. This means that we can communicate at several levels, not only with words.

One important difference between speaking and writing is that writing is usually more durable or permanent. When we speak, our words live for a few moments. When we write, our words may live for years or even centuries. This is why writing is usually used to provide a record of events, for example a business agreement or transaction.

Speaker & Listener / Writer & Reader

When we speak, we usually need to be in the same place and time as the other person. Despite this restriction, speaking does have the advantage that the speaker receives instant feedback from the listener. The speaker can probably see immediately if the listener is bored or does not understand something, and can then modify what he or she is saying.

When we write, our words are usually read by another person in a different place and at a different time. Indeed, they can be read by many other people, anywhere and at any time. And the people reading our words, can do so at their leisure, slowly or fast. They can re-read what we write, too. But the writer cannot receive immediate feedback and cannot (easily) change what has been written.

How Speaking and Writing Influence Each Other

In the past, only a small number of people could write, but almost everybody could speak. Because their words were not widely recorded, there were many variations in the way they spoke, with different vocabulary and dialects in different regions. Today, almost everybody can speak and write. Because writing is recorded and more permanent, this has influenced the way that people speak, so that many regional dialects and words have disappeared. (It may seem that there are already too many differences that have to be learned, but without writing there would be far more differences, even between, for example, British and American English.) So writing has had an important influence on speaking. But speaking can also influence writing. For example, most new words enter a language through speaking. Some of them do not live long. If you begin to see these words in writing it usually means that they have become "real words" within the language and have a certain amount of permanence.

Influence of New Technology

Modern inventions such as sound recording, telephone, radio, television, fax or email have made or are making an important impact on both speaking and writing. To some extent, the divisions between speaking and writing are becoming blurred. Emails are often written in a much less formal way than is usual in writing. With voice recording, for example, it has for a long time been possible to speak to somebody who is not in the same place or time as you (even though this is a one-way communication: we can speak or listen, but not interact). With the telephone and radiotelephone, however, it became possible for two people to carry on a conversation while not being in the same place. Today, the distinctions are increasingly vague, so that we may have, for example, a live television broadcast with a mixture of recordings, telephone calls, incoming faxes and emails and so on. One effect of this new technology and the modern universality of writing has been to raise the status of speaking. Politicians who cannot organize their thoughts and speak well on television win very few votes.

English Checker

- aspect: a particular part or feature of something

- dialect: a form of a language used in a specific region

- formal: following a set of rules; structured; official

- status: level or rank in a society

- spontaneous: not planned; unprepared

- structured: organized; systematic

Note : instead of "spoken", some people say "oral" (relating to the mouth) or "aural" (relating to the ear).

© 2011 Josef Essberger

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.2: Spoken Versus Written Communication

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 55218

What’s the Difference?

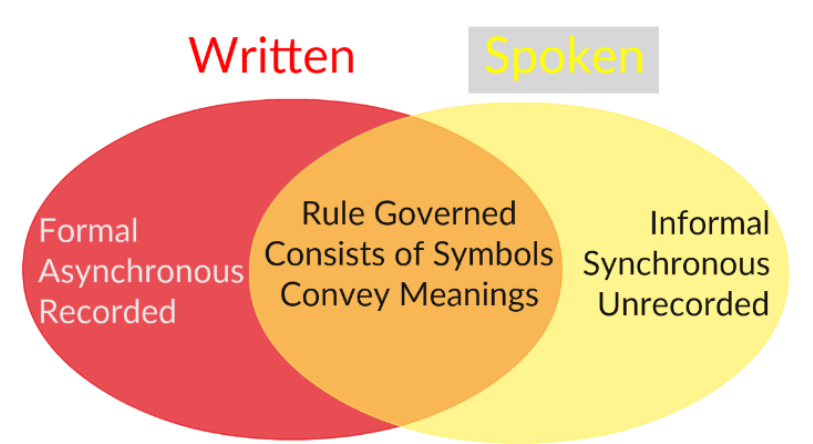

While both spoken and written communication function as agreed-upon rule-governed systems of symbols used to convey meaning, there are enough differences in pragmatic rules between writing and speaking to justify discussing some of their differences. Imagine for a moment that you’re a college student who desperately needs money. Rather than looking for a job you decide that you’re going to ask your parents for the money you need to make it through the end of the semester. Now, you have a few choices for using verbal communication to do this. You might choose to call your parents or talk to them in person. You may take a different approach and write them a letter or send them an email. You can probably identify your own list of pros and cons for each of these approaches. But really, what’s the difference between writing and talking in these situations? Let’s look at four of the major differences between the two: 1) formal versus informal, 2) synchronous versus asynchronous, 3) recorded versus unrecorded, and 4) privacy.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)1

Case In Point - Informal Versus Formal Communication

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)2

Text Version

FYI… we’re meeting on friday. wanna go to the office party after? its byob so bring whtvr you want. Last years was sooo fun. Your dancing made everyone lol! hope to see u there :)

Email Version

We are having a meeting on Friday, November 6th. Afterwards, there will be an office party. Let me know if you would like to attend. It will be a Bring Your Own Beverage party, so feel welcome to bring whatever you like. Last year’s was great, I’m sure everyone remembers your great dance moves! I hope to see you there,

The first difference between spoken and written communication is that we generally use spoken communication informally while we use written communication formally. Consider how you have been trained to talk versus how you have been trained to write. Have you ever turned in a paper to a professor that “sounds” like how you talk? How was that paper graded compared to one that follows the more formal structures and rules of the English language? In western societies like the U.S., we follow more formal standards for our written communication than our spoken communication. With a few exceptions, we generally tolerate verbal mistakes (e.g. “should of” rather than “should have”) and qualifiers (e.g. “uh” “um” “you know,” etc.) in our speech, but not our writing. Consider a written statement such as, “I should of, um, gone and done somethin’ ‘bout it’ but, um, I I didn’t do nothin’.” In most written contexts, this is considered unacceptable written verbal communication. However, most of us would not give much thought to hearing this statement spoken aloud by someone. While we may certainly notice mistakes in another’s speech, we are generally not inclined to correct those mistakes as we would in written contexts. Even though most try to speak without qualifiers and verbal mistakes, there is something to be said about those utterances in our speech while engaging in an interpersonal conversation. According to John Du Bois, the way two people use utterances and structure their sentences during conversation creates an opportunity to find new meaning within the language and develop “parallelism” which can lead to a natural feeling of liking or sympathy in the conversation partner. So, even though it may seem like formal language is valued over informal, this informal language that most of us use when we speak inadvertently contributes to bringing people closer together.

While writing is generally more formal and speech more informal, there are some exceptions to the rule, especially with the growing popularity of new technologies. For the first time in history, we are now seeing exceptions in our uses of speech and writing. Using text messaging and email, people are engaging in forms of writing using more informal rule structures, making their writing “sound” more like conversation. Likewise, this style of writing often attempts to incorporate the use of “nonverbal” communication (known as emoticons) to accent the writing. Consider the two examples in the box. One is an example of written correspondence using text while the other is a roughly equivalent version following the more formal written guidelines of an email or letter.

Notice the informality in the text version. While it is readable, it reads as if Tesia was actually speaking in a conversation rather than writing a document. Have you noticed that when you turn in written work that has been written in email programs, the level of formality of the writing decreases? However, when students use a word processing program like Microsoft Word, the writing tends to follow formal rules more often. As we continue using new technologies to communicate, new rule systems for those mediums will continue altering the rule systems in other forms of communication.

The second difference between spoken and written forms of verbal communication is that spoken communication or speech is almost entirely synchronous while written communication is almost entirely asynchronous. Synchronous communication is communication that takes place in real time, such as a conversation with a friend. When we are in conversation and even in public speaking situations, immediate feedback and response from the receiver is the rule. For instance, when you say “hello” to someone, you expect that the person will respond immediately. You do not expect that the person will get back to you sometime later in response to your greeting. In contrast, asynchronous communication is communication that is not immediate and occurs over longer periods of time, such as letters, email, or even text messages at times. When someone writes a book, letter, email, or text, there is no expectation from the sender that the receiver will provide an immediate response. Instead, the expectation is that the receiver will receive the message and respond to it when they have time. This is one of the reasons people sometimes choose to send an email instead of calling another person, because it allows the receiver to respond when they have time rather than “putting them on the spot” to respond right away.

Just as new technologies are changing the rules of formality and informality, they are also creating new situations that break the norms of written communication as asynchronous and spoken communication as synchronous. Voicemail has turned the telephone and our talk into asynchronous forms of communication. Even though we speak in these contexts, we understand that if we leave a message on voicemail, we will not get an immediate reply. Instead, we understand that the receiver will call us back at their convenience. In this example, even though the channel of communication is speaking, there is no expectation for immediate response to the sent message. Similarly, texting is a form of written communication that follows the rules of spoken conversation in that it functions as synchronous communication. When you type a text to someone you know, the expectation is that they will respond almost immediately. The lines continue to blur when video chats were introduced as communication technologies. These are a form of synchronous communication that mimics face-to-face interaction and in some cases even have an option to send written messages to others. The possible back and forth between written and spoken communication has allowed many questions to arise about rules and meaning behind interactions. Maria Sindoni explains in her article, “Through the Looking Glass” that even though people are having a synchronous conversation and are sharing meaning through their words, they are ultimately in different rooms and communicating through a machine which makes the meaning of their exchanges more ambiguous.

Verbal Communication Then 3

Historians have come up with a number of criteria people should have in order to be considered a civilization. One of these is writing, specifically for the purposes of governing and pleasure. Written verbal communication is used for literature, poetry, religion, instruction, recording history and governing. Influential written verbal communication from history includes:

- The Ten Commandments that Jews used as a guide to their faith

- Law Code of Hammurabi which was the recorded laws of the Ancient Babylonians.

- The Quran which is core to the Islam faith.

- The Bible which is followed by Christians.

- The Declaration of Independence which declared the U.S. independent from Britain.

- Mao’s Little Red Book which was used to promote communist rule in China.

The third difference between spoken and written communication is that written communication is generally archived and recorded for later retrieval, while spoken communication is generally not recorded. When we talk with friends, we do not tend to take notes or tape record our conversations. Instead, conversations tend to be ongoing and catalogued into our personal memories rather than recorded in an easily retrievable written format. On the other hand, it is quite easy to reference written works such as books, journals, magazines, newspapers, and electronic sources such as web pages and emails for long periods after the sender has written them. New communication applications like Vine add to the confusion. This app allows users to record themselves and post it to their profile. This would be considered a form of spoken communication, yet it is archived and asynchronous so others can look at the videos years after the original posting. To make the matter more complicated, Snapchat’s many functions come into play. On Snapchat you have the option of sending videos or photos that are traditionally not archived since the sender decides how long the receiver has to view them, then they will theoretically disappear forever. Most recently with the addition of My Story, users of the app can post a picture for 24 hours and have their friends view it multiple times. The feeling of technological communication not being archived can lead to a false sense of privacy, which can lead to some negative consequences.

As with the previous rules we’ve discussed, new technologies are changing many of the dynamics of speech and writing. Just take a look at the “Verbal Communication Then” sidebar and see how far we have come. For example, many people use email and texting informally like spoken conversation, as an informal form of verbal communication. Because of this, they often expect that these operate and function like a spoken conversation with the belief that it is a private conversation between the sender and receiver. However, many people have gotten into trouble because of what they have “spoken” about others through email and text. The corporation Epson (a large computer electronics manufacturer) was at the center of one of the first lawsuits regarding the recording and archiving of employees’ use of email correspondence. Employees at Epson assumed their email was private and therefore used it to say negative things about their bosses. What they didn’t know was their bosses were saving and printing these email messages, and using the content of these messages to make personnel decisions. When employees sued Epson, the courts ruled in favor of the corporation, stating that they had every right to retain employee email for their records.

While most of us have become accustomed to using technologies such as texting and instant messaging in ways that are similar to our spoken conversations, we must also consider the repercussions of using communication technologies in this fashion because they are often archived and not private. We can see examples of negative outcomes from archived messages in recent years through many highly publicized sexting scandals. One incident that was very pertinent was former congressman and former candidate for Mayor of New York, Anthony Weiner, and a series of inappropriate exchanges with women using communication technologies. Because of his position in power and high media coverage, his privacy was very minimal. Since he had these conversations in a setting that is recorded, he was not able to keep his anonymity or confidentiality in the matter. These acts were seen as inappropriate by the public, so there were both professional and personal repercussions for Weiner. Both the Epson and Anthony Weiner incidents, even though happening in different decades, show the consequences when assumed private information becomes public.

As you can see, there are a number of differences between spoken and written forms of verbal communication. Both forms are rule-governed as our definition points out, but the rules are often different for the use of these two types of verbal communication. However, it’s apparent that as new technologies provide more ways for us to communicate, many of our traditional rules for using both speech and writing will continue to blur as we try to determine the “most appropriate” uses of these new communication technologies. As Chapter 2 pointed out, practical problems of the day will continue to guide the directions our field takes as we continue to study the ways technology changes our communication. As more changes continue to occur in the ways we communicate with one another, more avenues of study will continue to open for those interested in being part of the development of how communication is conducted. Now that we have looked in detail at our definition of verbal communication, and the differences between spoken and written forms of verbal communication, let’s explore what our use of verbal communication accomplishes for us as humans.

Functions of Verbal Communication

Our existence is intimately tied to the communication we use, and verbal communication serves many functions in our daily lives. We use verbal communication to define reality, organize, think, and shape attitudes.

Teaching And Learning Communication Now

Being able to communicate effectively through verbal communication is extremely important. No matter what you plan to do as a career, effective verbal communication helps you in all aspects of your life. Former President Bush was often chided (and even chided himself) for the verbal communication mistakes he made. Here is a list of his “Top 10”.

- “Families is where our nation finds hope, where wings take dream.” —LaCrosse, Wis., Oct. 18, 2000

- “I know how hard it is for you to put food on your family.” —Greater Nashua, N.H., Jan. 27, 2000

- “I hear there’s rumors on the Internets that we’re going to have a draft.” —second presidential debate, St. Louis, Mo., Oct. 8, 2004

- “I know the human being and fish can coexist peacefully.” —Saginaw, Mich., Sept. 29, 2000

- “You work three jobs? … Uniquely American, isn’t it? I mean, that is fantastic that you’re doing that.” —to a divorced mother of three, Omaha, Nebraska, Feb. 2005

- “Too many good docs are getting out of the business. Too many OB-GYNs aren’t able to practice their love with women all across this country.” —Poplar Bluff, Mo., Sept. 6, 2004

- “They misunderestimated me.” —Bentonville, Ark., Nov. 6, 2000

- “Rarely is the questioned asked: Is our children learning?” —Florence, S.C., Jan. 11, 2000

- “Our enemies are innovative and resourceful, and so are we. They never stop thinking about new ways to harm our country and our people, and neither do we.” —Washington, D.C., Aug. 5, 2004

- “There’s an old saying in Tennessee — I know it’s in Texas, probably in Tennessee — that says, fool me once, shame on — shame on you. Fool me — you can’t get fooled again.” —Nashville, Tenn., Sept. 17, 2002

Verbal communication helps us define reality

We use verbal communication to define everything from ideas, emotions, experiences, thoughts, objects, and people (Blumer). Think about how you define yourself. You may define yourself as a student, employee, son/daughter, parent, advocate, etc. You might also define yourself as moral, ethical, a night-owl, or a procrastinator. Verbal communication is how we label and define what we experience in our lives. These definitions are not only descriptive, but evaluative. Imagine you are at the beach with a few of your friends. The day starts out sunny and beautiful, but the tides quickly turn when rain clouds appear overhead. Because of the unexpected rain, you define the day as disappointing and ugly. Suddenly, your friend comments, “What are you talking about, man? Today is beautiful!” Instead of focusing on the weather, he might be referring to the fact that he was having a good day by spending quality time with his buddies on the beach, rain or shine. This statement reflects that we have choices for how we use verbal communication to define our realities. We make choices about what to focus on and how to define what we experience and its impact on how we understand and live in our world.

Verbal communication helps us organize complex ideas and experiences into meaningful categories. Consider the number of things you experience with your five primary senses every day. It is impossible to comprehend everything we encounter. We use verbal communication to organize seemingly random events into understandable categories to make sense of our experiences. For example, we all organize the people in our lives into categories. We label these people with terms like, friends, acquaintances, romantic partners, family, peers, colleagues, and strangers. We highlight certain qualities, traits, or scripts to organize outwardly haphazard events into meaningful categories to establish meaning for our world.

Verbal communication helps us think. Without verbal communication, we would not function as thinking beings. The ability most often used to distinguish humans from other animals is our ability to reason and communicate. With language, we are able to reflect on the past, consider the present, and ponder the future. We develop our memories using language. Try recalling your first conscious memories. Chances are, your first conscious memories formed around the time you started using verbal communication. The example we used at the beginning of the chapter highlights what a world would be like for humans without language. In the 2011 Scientific American article, “How Language Shapes Thought,” the author, Lera Boroditsky, claims that people “rely on language even when doing simple things like distinguishing patches of color, counting dots on a screen or orienting in a small room: my colleagues and I have found that limiting people’s ability to access their language faculties fluently–by giving them a competing demanding verbal task such as repeating a news report, for instance–impairs their ability to perform these tasks.” This may be why it is difficult for some people to multitask – especially when one task involves speaking and the other involves thinking.

Verbal communication helps us shape our attitudes about our world. The way you use language shapes your attitude about the world around you. Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf developed the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis to explain that language determines thought. People who speak different languages, or use language differently, think differently (Whorf; Sapir; Mandelbaum; Maxwell; Perlovsky; Lucy; Simpson; Hussein). The argument suggests that if a native English speaker had the exact same experiences in their life, but grew up speaking Chinese instead of English, their worldview would be different because of the different symbols used to make sense of the world. When you label, describe, or evaluate events in your life, you use the symbols of the language you speak. Your use of these symbols to represent your reality influences your perspective and attitude about the world. So, it makes sense then that the more sophisticated your repertoire of symbols is, the more sophisticated your world view can be for you. While the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is highly respected, there have been many scholarly and philosophical challenges to the viewpoint that language is what shapes our worldview. For example, Agustin Vicente and Fernando Martinez-Manrique did a study regarding the “argument of explicitness,” which has two premises. The first premise is that “the instrument of thought must be explicit” in order for thought and language to be connected; the second is that natural languages – languages that humans can learn cognitively as they develop – are not explicit (Vicente and Martinez-Manrique, 384). The authors conclude that thoughts “demand a kind of completeness and stability of meaning that natural language sentences, being remarkably underdetermined, cannot provide” (Vicente and Martinez-Manrique, 397). It makes sense that something as arbitrary and complicated as the connection between thought and language is still being debated today.

While we have overly-simplified the complexities of verbal communication for you in this chapter, when it comes to its actual use—accounting for the infinite possibilities of symbols, rules, contexts, and meanings—studying how humans use verbal communication is daunting. When you consider the complexities of verbal communication, it is a wonder we can communicate effectively at all. But, verbal communication is not the only channel humans use to communicate. In the next chapter we will examine the other most common channel of communication we use: nonverbal communication.

- Image by H. Rayl is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Image by Garry Knight is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

- Content from Global Virtual Classroom

Contributors and Attributions

- Template:ContribCCComm100

- My Portfolio

Writing vs. Speaking – The Similarities and Differences

If you work somewhere as a writer, you may have often heard your supervisor saying: ‘Please, try to write in the way you speak so that we can sell our products effectively.’ If you are an expert at Grammar, you may reply to your supervisor: How can I express punctuation marks while speaking? Both you and your supervisor are right. Writing and speaking do have similarities; however, people need to know that there are also differences between the two. Without further ado, let’s have a look at the similarities and differences between writing and speaking:

The Similarities between Writing and Speaking

Point #1: Writers are motivated to speak to the audience as per their needs while writing, and the speakers do the same thing.

Point #2: You need to highlight essential points in the form of a summary, whether you are writing or speaking.

Point #3: You need to stick to the point while writing, so you need to keep the length of your sentences to eight to fifteen (8 to 15) words while writing. You need to remain clear while speaking, so you need to remain restricted to a few words to convey your message correctly.

Point #4: While writing, you focus on keywords to convey your message, and you make a strong emphasis on words that can deliver your message well to the audience. Thus, both writers and speakers speak of the keywords.

Point #5: Make a valid claim if you want to sell, particularly if you’re going to sell your product by writing. You need to do the same while speaking; otherwise, your audience can switch to your competitors.

Point #6: Jargons are bad, so you shouldn’t use them while speaking and writing. Why? Because the whole world has no time to chat and produce slang words.

Point #7: Whether you speak or write, you need to repeat important words to ensure your message is being conveyed to the audience.

Point #8: You will need to come up with a good message to win your audience’s trust. Thus, you need to edit your content and proofread while reading; the same goes for speech.

Point #9: You need a theme to start with while writing or speaking.

Point #10: Pictures can speak a thousand words. You need to use them while you want to elaborate on something while writing. You also need to use the pictures to express your message to the target audience while giving a presentation.

Point #11: Use strong words while you speak or write. For instance, you can use the following sentence while speaking or writing: ‘Each participant has an equal chance (strong words) of selection.’

Point #12: Explain your point while writing and speaking to let the audience understand what you want to convey to them.

The Differences between Writing and Speaking

Point #1: Readers want to read whenever they have a desire for it. For example: ‘Readers may pick up a book, white paper, and a proposal to read it.’ Thus, writers can get the readers’ attention easily. However, the listeners don’t plan to listen to you all day; hence, you need to stick to the point while speaking to the audience.

Point #2: You can easily interpret emotion from a speaker than an author. Yes, writers can bring feelings in you; nonetheless, if you are writing a business letter, you should avoid emotional words if you want to get your reader’s attention. Business is a serious deal; therefore, you should avoid emotions in business writing.

Point #3: If you want to feel your audience’s response with your own eyes, you can rely on speaking. Why? Because writers don’t convey their messages in front of the audience.

Point #4: The proper usage of Grammar can make your write-ups better. You can’t do that while speaking because you make loads of grammatical mistakes while speaking. For instance, ‘A comma is used for a pause in writing; however, while speaking, you may avoid that pause and may spoil your speech to convey your message to the audience better.’

Finally, if you know many other similarities and differences between writing and speaking, you can share them in the form of comments.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

10 EXCELLENT RESOURCES TO FIND TRENDING TOPICS AND WRITE ARTICLES

Why Can You Trust a Freelance Content Writer?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

I'M SOCIAL

Popular posts.

How Did Animation Proceed From Past to Present? Each Explainer Video Has a Value for Business

VALENTINE’S DAY

What Is a Logo?

Popular categories.

- Industry 17

- Content Writing 4

- Search Engine 4

- Ecommerce 1

MY FAVORITES

Top 5 most valuable fashion brands in the world, the mental health benefits of workouts, top 12 technology trends to follow in 2021, top 10 low investment business ideas in pakistan.

- Digital Offerings

- Biochemistry

- College Success

- Communication

- Electrical Engineering

- Environmental Science

- Mathematics

- Nutrition and Health

- Philosophy and Religion

- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Accessibility

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

- Learning Science

- Sustainability

- Affordable Solutions

- Curriculum Solutions

- Inclusive Access

- Lab Solutions

- LMS Integration

- Instructor Resources

- iClicker and Your Content

- Badging and Credidation

- Press Release

- Learning Stories Blog

- Discussions

- The Discussion Board

- Webinars on Demand

- Digital Community

- Macmillan Learning Peer Consultants

- Macmillan Learning Digital Blog

- Learning Science Research

- Macmillan Learning Peer Consultant Forum

- The Institute at Macmillan Learning

- Professional Development Blog

- Teaching With Generative AI: A Course for Educators

- English Community

- Achieve Adopters Forum

- Hub Adopters Group

- Psychology Community

- Psychology Blog

- Talk Psych Blog

- History Community

- History Blog

- Communication Community

- Communication Blog

- College Success Community

- College Success Blog

- Economics Community

- Economics Blog

- Institutional Solutions Community

- Institutional Solutions Blog

- Handbook for iClicker Administrators

- Nutrition Community

- Nutrition Blog

- Lab Solutions Community

- Lab Solutions Blog

- STEM Community

- STEM Achieve Adopters Forum

- Contact Us & FAQs

- Find Your Rep

- Training & Demos

- First Day of Class

- For Booksellers

- International Translation Rights

- Permissions

- Report Piracy

Digital Products

Instructor catalog, our solutions.

- Macmillan Community

- What Are the Differences Between Speaking and Writ...

What Are the Differences Between Speaking and Writing?

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

- basic writing

- digital composing

- professional development

- teaching advice

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.

- Bedford New Scholars 49

- Composition 551

- Corequisite Composition 58

- Developmental English 38

- Events and Conferences 6

- Instructor Resources 9

- Literature 55

- Professional Resources 4

- Virtual Learning Resources 48

- Essay Guide

- Alex Essay Writing Tool

- Dissertation Guide

- Ask The Elephant

Speaking vs. Writing

Speaking vs writing 1: alan buys milk.

Another way to think about what’s involved in writing clearly is to think about the differences between speaking and writing. Because both use words, we assume they are the same but they are very different. The following example will help you think about the differences. Picture this: it’s Saturday morning, the family’s just sat down to breakfast when Dad realises there’s no milk. So he asks his eldest son Alan to go and get some. He says: “Drat! No milk – I can’t eat my cornflakes without some nice cold milk. Just pop out to the mini-mart, would you Alan? Better get a two pinta. Oh, and you’ll find some money in my jacket pocket.”

Speaking vs writing 2: a robot buys milk

Now picture this: imagine you had to write a computer program to tell a robot to go and buy milk. Where would you start? You would have to think of the most logical order for all the actions the robot would need to perform in order to buy milk. Dad’s instruction to Alan assumes that Alan already knows all sorts of information: where his jacket is, which pocket he usually keeps his money, where the mini-mart is, the visual difference between a one pint and two pint carton. The robot will know none of these things unless you put them in the program. You would also have to give the program a logical name or title so that when the program loaded the robot’s brain would be able to distinguish it from all the other programs in its memory. So in your writing at university, don’t be afraid to be obvious. One of the reasons tutors set essays is so you can show what you know.

Speaking vs writing 3: look at me when I’m talking to you

Another crucial difference between speaking and writing is that we can see people when we talk to them. We transmit and receive all sorts of non-verbal information when we’re talking to them. Think about the effect it has on you when someone talks to you but keeps staring at the floor and never looks at you once. We communicate all sorts of information by facial expression, hand gestures, tone of voice. We can’t do any of these things in a piece of writing. We have to find different ways of doing them; and we have to be sure that our writing isn’t doing things we don’t want it to.

Speaking vs writing 4: know what I mean?

Another crucial difference between speaking and writing is that speaking is informal, less structured, more colloquial – know what I mean? When we speak, we often start sentences in the middle. An important part of writing at university is to understand who you are writing for. To put this another way, when you are writing an essay you are not down the pub with your mates. In an essay, you can’t put things like the following sentence I once read in a first draft: “Apparently, imperialism has been going for ages – how weird is that?” The person who reads your essay will expect you to write in a serious and considered way.

Privacy Overview

- TOP CATEGORIES

- AS and A Level

- University Degree

- International Baccalaureate

- Uncategorised

- 5 Star Essays

- Study Tools

- Study Guides

- Meet the Team

- English Language

- Language: Context, Genre & Frameworks

Differences between Speech and Writing.

This is a preview of the whole essay

Document Details

- Word Count 1056

- Page Count 3

- Level AS and A Level

- Subject English

Related Essays

Consider the differences between speech and writing.

Is it true that typical speech and typical writing have many different qual...

The features of written language and speech

'Writing is often thought to be superior to speech - To what extent is this...

Word frequency in speech and writing

- Word frequency

- Word frequency: Activity

- Baby Sentences: Activity

- Compound word creation: Activity 2

- Verb endings

- Verb endings: Activity

- Adjective identification

- Adjective identification: Activity 1

- Adjective identification: Activity 2

- Adverb identification

Comparing word frequencies is an interesting way to think about some of the differences between speech and writing. Which are the most frequent words in speech, and how do they compare with the most frequent words in writing?

The Activity page appears in the menu entitled 'This Unit' in the upper right corner of this page. The Activity page can be displayed on a projector or smart board. The Activity page presents the ten most frequently used words in speech and in writing. How do we know which words are used most frequently? We use a corpus ! These figures are are based on the British National Corpus (BNC), a very large collection of real spoken and written British English. More information on the BNC can be found here .

Ask students the following questions:

- What words appear in both lists?

- What words appear only in the spoken list, or only in the written list?

- What do you notice about the differences between the spoken and written lists?

- Can you think of any possible reasons for the differences?

They might have noticed the following points:

- The spoken list has the contracted verb form ’s while the written list has the full form of the same verb, is . Contracted verb forms like this are much more frequent in speech than in writing.

- The spoken list has the personal pronouns I and you , which are not in the written list. This reflects the personal involvement and interactivity which are typical of spoken dialogue. Speakers often refer to themselves and to the people they are talking to (called interlocutors ). Writers do so less often.

- Only the written list has the past tense form was . The past tense is used more frequently in writing than in speech, as participants in spoken dialogue tend to talk more about the 'here' and 'now' than about the past.

We need to remember that these contrasts involve frequency differences rather than hard-and-fast rules. For instance, the past tense is of course not restricted to written English. We can and do use the past tense to discuss past events in spoken interaction too. It’s just that there is a strong tendency to talk more often about the present than the past.

Another point to remember is that not all types of written English work in a similar way, and nor do all types of spoken English. Informal types of written English (like social letters or texts) tend to be more like conversation, while a formal prepared speech tends to be more like writing.

Englicious is totally free for everyone to use!

But in exchange, we ask that you register for an account on our site.

If you’ve already registered, you can log in straight away.

Since this is your first visit today, you can see this page by clicking the button below.

- Word frequency in speech and writing: Activity

Verbs constitute one of the major word classes , including words for actions (e.g. shout , work , travel ) and states (e.g. be , belong , remain ). There are two main types of verb: main verbs and auxiliary verbs .

The surest way to identify verbs is by the ways they can be used: they can usually have a tense , either present tense or past tense (see also future ).

- He lives in Birmingham. [present tense]

- The teacher wrote a song for the class. [past tense]

Verbs are sometimes called ‘doing words’ because many verbs name an action that someone does; while this can be a way of recognising verbs, it doesn’t distinguish verbs from nouns (which can also name actions). Moreover many verbs name states or feelings rather than actions.

- He likes chocolate. [present tense; not an action]

- He knew my father. [past tense; not an action]

- The walk to Halina’s house will take an hour. [noun]

- All that surfing makes Morwenna so sleepy! [noun]

Verbs can be classified in various ways: for example, as auxiliary verbs , or modal verbs ; as transitive verbs or intransitive verbs ; and as states or events.

Irregular verbs form their past tense typically by a change of vowel (e.g. break-broke, see-saw, eat-ate). Be aware that in the National Curriculum a sequence of one or more auxiliaries together with a main verb are regarded as forms of the main verb. For example, have eaten is a form (the perfect form) of the verb eat , and will have been being seen is a form of the verb see . In other frameworks such sequences are regarded as verb phrases .

The past tense is a grammatical marking on verbs . (See also inflection .) E.g. the verb in She sounded tired is a past tense form (compare the present tense form in She sounds tired ).

Verbs in the past tense are commonly used to:

- talk about the past

- talk about imagined situations

- make a request sound more polite.

Most verbs take a suffix –ed , to form their past tense, but many commonly-used verbs are irregular.

See also tense .

- Tom and Chris showed me their new TV. [names an event in the past]

- Antonio went on holiday to Brazil. [names an event in the past; irregular past of go ]

- I wish I had a puppy. [names an imagined situation, not a situation in the past]

- I was hoping you'd help tomorrow. [makes an implied request sound more polite]

- Printer-friendly version

- Log in to view or leave comments

- Create new account

- Request new password

- Key Stage 1

- Y6 GPaS Test

- Key Stage 3

- Key Stage 4

- 'A' level

Language in use

- Composition

- Spoken language

- Standards and variation

- Grammar in context

- Word structure

- Word classes

- Grammar and meaning

Content type

- Assessments

- Professional development

- NC Specifications

2 Chapter 2. A Crash Course in Linguistics

Adapted from Hagen, Karl. Navigating English Grammar. 2020. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Language is an extremely complex system consisting of many interrelated components. As a result, learning how to analyze language can be challenging because to understand one part you often need to know about something else. In general, this book works on describing English sentence structure, which largely falls under the category of syntax, but there are other components to language, and to understand syntax, we will need to know a few basics about those other parts.

This chapter has two purposes: first, to give you an overview of the major structural components of language; second, to introduce some basic concepts from areas other than syntax that we will need to make sense of syntax itself.

We can think of language both in terms of a message and a medium by which that message is transmitted. These two aspects are partly independent of one another. For example, the same message can be conveyed through speech or through writing. Sound is one medium for transmitting language; writing is another. A third medium, although not one that occurs to most people immediately, is gesture, in other words, sign language. The message is only partly independent of the medium because while it is certainly possible to express the same message through different media, the medium has a tendency to shape the message by virtue of its peculiarities.

When we look at the content of the message, we find it consists of a variety of building blocks. Sounds (or letters) combine to make word parts, which combine to make words, which combine to make sentences, which combine to make a discourse. Indeed, language is often said to be a combinatorial system, where a small number of basic building blocks combine and recombine in different patterns. A small number of blocks can account for a very large variety indeed. DNA, another combinatorial system, uses only four basic blocks, and combinations of these four blocks give rise to all the biological diversity we see on earth today. With language, different combinations of a small number of sounds yield hundreds of thousands of words, and different combinations of those words yield an essentially infinite number of utterances.

The major components that have traditionally been considered the ‘core’ areas of linguistics are the following:

- Phonology : The patterns of sounds in language.

- Morphology : Word formation.

- Syntax : The arrangement of words into larger structural units such as phrases and sentences.

- Semantics : Meaning. Semantics sometimes refers to meaning independent of any particular context, and is distinguished from pragmatics , or how meaning is affected by the context in which it is uttered. For the purposes of this book, we will work under the assumption that there really is no such thing as completely decontextualized meaning.

Section contributors: Saul De Leon, Jodiann N. Samuels and an anonymous ENG 270 student.

Language varieties sound different from one another because they have different inventories of speech sounds. The sounds that you hear—combined into words that make sense—is called phonology . There is no clear limit to the number of distinct sounds that can be constructed by the human vocal apparatus. To that end, this unlimited variety is harnessed by human language into sound systems that are comprised of a few dozen language-specific categories known as phonemes (Szczegielniak). Phonology is the systemic study of sounds used in language, their internal structure, and their composition into syllables, words, and phrases. Sounds are made by pushing air from the lungs out through the mouth, sometimes by way of the nasal cavity (Kleinman). Think about this: All humans have a different way of pronouncing words that produce various sounds. Tongue movement, tenseness, and lip rounding (rounded or unrounded) are some examples in which sounds or even words are produced in different ways. Consider, for example, the sound of the consonant /ð/ represented by the written <th> in the English word <the>—this sound does not exist in French, but we can understand someone whose first language is French when they pronounce the same word with a /z/. Phonology seeks to explain the patterns of sounds that are used and how different rules interact with each other. Phonology is concerned more about the structure of sound instead of the sound itself; “Phonology focuses on the ‘function’ or ‘organization’ or patterning of the sound” (Aarts & McMahon pg. 360)

Every language variety has an inventory of sounds (essentially, they have different numbers of phonemes) and rules for those sounds. By way of illustration, in English, the phoneme /ŋ/, the last sound in the word sing , will never appear at the beginning of a word, but in some other languages, words can begin with /ŋ/.

Throughout this section, we will use the conventional / / slashes to indicate International Phonetic Alphabet representations of phonemes (the sounds of language) and < > brackets to indicate orthography (the way things are spelled in the standardized English writing system).

Say the following out loud: Vvvv. It has a “buzz” sound that ffff does not have, right? Keep in mind that the “buzz” sound is caused by the vibration of your vocal folds. Speech sounds are produced by moving air from the lungs through your larynx, the vocal cords that open to allow breathing—the noise made by the larynx is changed by the tongue, lips, and gums to generate speech. Most importantly, however, sounds are different from letters that are in a word. For example, a world like English has seven letters (<English>), six sounds (/ɪŋɡlɪʃ/), and two syllables (eng·lish). We often tend to think of English as a written language, but when studying phonology, it’s important not to conflate sounds and letters. This is more often true in English than in many other languages that use alphabets for their scripts; not only are the correspondences between sounds and letters not always one-to-one, sounds are often pronounced in many ways by different people. When you are speaking to someone, you automatically ignore nonlinguistic differences in speech (i.e., someone’s pitch level, rate of speed, coughs) (Szczegielniak).

Phonemes are a vital part of speech because they are what dictates how a sound of letter or word is distinguished which differentiates the meaning of words. Sometimes a letter represents more than one phoneme (<x> is often pronounced /ks/) and sometimes two or three letters are used to represent a single sound (like <sh> for the phoneme /ʃ/ ).

The sounds of a word can be broken down into phonemes , the smallest units of sound that distinguish meaning. These basic sounds can be arranged into syllables and a metrical phonological tree can be used to simplify breaking up a syllable (AAL Alumnae, Gussenhoven & Haike).

There are about 200 phonemes across all known languages; however, there are about forty-four in the English language and the forty-four phonemes are represented by the twenty-six letters of the alphabet (individually and in combination). The forty-four English sounds are thus divided into two distinct categories: consonants and vowels. A consonant gives off a basic speech sound in which the airflow is cut off or restrained in some way—when a sound is produced. On the other hand, if the airflow is unhindered when a sound is made, the speaker is producing a vowel. (DSF Literary Resources). Even with diphthongs, or sequences of two vowels, your tongue changes when you say a different vowel.

A syllable consists of an initial sound or onset and followed by another sound called a rhyme. A rhyme is further split into a nucleus which are the vowel sounds and the coda which are the consonants that come after the nucleus. The onset is simply the consonants before the rhyme. These aspects are all brought together to identify the differences of languages due to each language’s unique phonemes and syllable structures. (AAL Alumnae, n.d.).

Phonology and Phonetics

The study of phonology is closely related to another field, phonetics . Phonetics involves the study of the way sound is produced by certain parts of the body. The synchronous use of body parts like the mouth, teeth, tongue, voice box or larynx, and pharynx are involved with making speech sounds and what sounds exist in a language, and in sign languages, the shape and position of fingers and hands serves a similar purpose. Phonology and phonetics together can even analyze the distinction between distinctive accents or challenges native speakers may face attempting to acquire another language when facing phonemes that are not a part of their language (FSI, n.d.; Gussenhoven & Haike, 2017, p. 17).

Minimal Pairs and Allophones

Understanding how to pronounce and to make a clear distinction of letters is essential to the structure of a language sound system. In English and other languages, there are many words that sound similar to one another, but differ in a single sound, like ‘pit’ and ‘bit’, or like ‘leap’ and ‘leave’. Linguists call these minimal pairs. “Minimal pairs are word that differs in one phoneme” (McArthur Oxford Reference). Even though they end identically both words are completely unrelated to each other in meaning. Minimal pairs are useful for linguists because they provide comprehension into how sounds and meanings coexist in language. They tell us which sounds (phones) are distinct phonemes, and which are allophones of the same phoneme.

Allophones are a related concept, in which a single phoneme can be produced differently in different circumstances. For example, the phoneme /k/ in the word ‘kite’ is aspirated, meaning it’s accompanied by a puff of air. But in the word ‘sky’ there is no puff of air along with the /k/ sound. We still think of these as the same sound, and they don’t occur in the same positions, which makes them allophones of a single phoneme.

Allophones are determined by their position in the word or by their phonetic environment. Speakers often have issues hearing the phonetic differences between allophones of the same phoneme because these differences do not serve to distinguish one word from another. In English, the /t/ sounds in the words “hit,” “tip,” and “little” are all allophones (Britannica)—they are all realizations the same phoneme, though they are different phonetically in terms of how they are produced.

The relationship between syntax and phonology

Syntax and phonology are both structural components of language, but it is common to think of them as parallel levels of structure that do not often interact. What they both address at their core is the structure of the language, but we could consider morphology (described in the next section) to mediate between the two.

Citations and Further Reading:

- AAL Alumnae. “Why Study Phonology”. University of Sheffield. 2012a. https://sites.google.com/a/sheffield.ac.uk/aal2013/branches/phonology/why-study-phonology Accessed 09 September 2020.

- Anderson, Catherine. “4.2 Allophones and Predictable Variation.” Essentials of Linguistics, McMaster University, 15 Mar. 2018, https://essentialsoflinguistics.pressbooks.com/chapter/4-3-allophones-and-predictable-variation Accessed: 21 September 2020.

- Bromberger, Sylvain, and Morris Halle. “Why Phonology Is Different.” Linguistic Inquiry , vol. 20, no. 1, 1989, pp. 51–70. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/4178613 Accessed 7 Sept. 2020.

- Collier, Katie, et al. “Language Evolution: Syntax before Phonology?” Proceedings: Biological Sciences , vol. 281, no. 1788, 2014, pp. 1–7. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/43600561. Accessed 7 Sept. 2020 .

- Coxhead, P. “Natural Language Processing & Applications Phones and Phonemes.” University of Birmingham (UK) , 2006, www.cs.bham.ac.uk/~pxc/nlp/NLPA-Phon1.pdf

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Allophone.” Encyclopædia Britannica , Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 26 Feb. 2018, www.britannica.com/topic/allophone .

- FIS. “Phonetics and Phonology.” Language Differences – Phonetics and Phonology . Frankfurt International School. https://esl.fis.edu/grammar/langdiff/phono.htm Accessed 09 September 2020.

- Goswami, Usha. “Phonological Representation.” SpringerLink , Springer, Boston, MA. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6 Accessed: 21 September 2020.

- Gussenhoven, Carlos, and Haike, Jacobs. Understanding phonology . London New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017. https://salahlibrary.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/understanding-phonology-4th-ed.pdf Accessed: 05 September 2020.

- Hayes, Bruce. Introductory Phonology . John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Hellmuth, Sam, and Ian Cushing. “Grammar and Phonology.” Oxford Handbooks Online , 14 Nov. 2019, www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198755104.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780198755104-e-2

- Honeybone, Patrick, and Bermudez-Otero, Ricardo. “Phonology and Syntax: A Shifting Relationship.” Lingua, 22 Oct. 2004, pp. 543-561. www.lel.ed.ac.uk/homes/patrick/lingua.pdf Accessed 21 September 2020 .

- K12 Reader. “Phonemic Awareness vs. Phonological Awareness Explained.” Phonemic Awareness vs Phonological Awareness. K12 Reader Reading Instruction Resources, 29 Mar. 2019. www.k12reader.com/phonemic-awareness-vs-phonological-awareness/ Accessed 21 September 2020.

- Kirchner, Robert. “Chapter 1 – Phonetics and Phonology: Understanding the Sounds of Speech.” University of Alberta , https://sites.ualberta.ca/~kirchner/Kirchner_on_Phonology.pdf .

- American Speech-Language Hearing Association. “Language in Brief.” American Speech-Language-Hearing Association , www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Spoken-Language-Disorders/Language-In–Brief/

- Kleinman, Scott. 2006. “Phonetics and Phonology.” California State University, Northridge , www.csun.edu/~sk36711/WWW/engl400/phonol.pdf

- Szczegielniak, Adam. “Phonology: The Sound Patterns of Language.” Harvard University , https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/adam/files/phonology.ppt.pdf

- Aarts, Bas, and April McMahon. The Handbook of English Linguistics. 1. Aufl. Williston: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. Print.

- De Lacy, Paul V. The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology. Cambridge University Press, 2007. Print.

- McArthur, Tom, Jacqueline Lam-McArthur, and Lise Fontaine. Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press USA – OSO, 2018. Print.

- Philipp Strazny. Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 1st ed. Chicago: Taylor and Francis, 2013. Web.

Contributors: Paul Junior Prudent and an anonymous ENG 270 student

Morphology is a branch of linguistics that deals with the structure and form of the words in a language (Hamawand 2). In grammar, morphology differs from syntax, though both are concerned with structure. Syntax is the field that studies the structure of sentences, which are composed of words, while morphology is the field that studies the structure of the words themselves (Julien 8). Unlike phonology, covered earlier, morphology is more directly related to syntax, and will see some coverage in this textbook.

In language, some words are made up of one indivisible part, but many other words are made up of more than one component, and these components (whether a word has one or more) are called morphemes. A morpheme is a minimal unit of lexical meaning (Hamawand 3). So, while some words can consist of one morpheme and thus be minimal units of meaning in and of themselves, many words consist of more than one morpheme. For example, the word peace has one morpheme and cannot be broken down into smaller units of meaning. Peaceful has two morphemes, peace the state of harmony that exists during the absence of war, plus -ful , a suffix, meaning full of something. Peacefully has three morphemes: peace + – ful + – ly , with the final morpheme – ly indicating ‘in the manner of’. So really, peacefully contains three units of meaning that, when combined, give us the meaning of the word as a whole. Words can have a lot more than three morphemes, however (Kurdi 90).

Comparative Morphology

In some languages, there are only simple words and straightforward compounds, and therefore very little morphology—most of the grammatical complexity is syntactic in these languages. Languages like these are referred to as having an isolating morphology . On the other end of the scale, languages that combine many morphemes to produce words are referred to as polysynthetic . Polysynthetic essentially means that the language is characterized by complex words consisting of several morphemes, in which a single word may function as a whole sentence. Other types of language morphology in between are fusional (where morphemes often encode multiple meanings or grammatical categories at once) and agglutinative (where morphemes are added on to each other to create long words, but generally have individual meanings). Modern English is closer to the isolating end of the spectrum, while still having a productive morphology on some morphemes. Languages like this are known as analytic languages, in which sentences are constructed by following a specific word order.

Types of morphemes