Explore your training options in 10 minutes Get Started

- Graduate Stories

- Partner Spotlights

- Bootcamp Prep

- Bootcamp Admissions

- University Bootcamps

- Coding Tools

- Software Engineering

- Web Development

- Data Science

- Tech Guides

- Tech Resources

- Career Advice

- Online Learning

- Internships

- Apprenticeships

- Tech Salaries

- Associate Degree

- Bachelor's Degree

- Master's Degree

- University Admissions

- Best Schools

- Certifications

- Bootcamp Financing

- Higher Ed Financing

- Scholarships

- Financial Aid

- Best Coding Bootcamps

- Best Online Bootcamps

- Best Web Design Bootcamps

- Best Data Science Bootcamps

- Best Technology Sales Bootcamps

- Best Data Analytics Bootcamps

- Best Cybersecurity Bootcamps

- Best Digital Marketing Bootcamps

- Los Angeles

- San Francisco

- Browse All Locations

- Digital Marketing

- Machine Learning

- See All Subjects

- Bootcamps 101

- Full-Stack Development

- Career Changes

- View all Career Discussions

- Mobile App Development

- Cybersecurity

- Product Management

- UX/UI Design

- What is a Coding Bootcamp?

- Are Coding Bootcamps Worth It?

- How to Choose a Coding Bootcamp

- Best Online Coding Bootcamps and Courses

- Best Free Bootcamps and Coding Training

- Coding Bootcamp vs. Community College

- Coding Bootcamp vs. Self-Learning

- Bootcamps vs. Certifications: Compared

- What Is a Coding Bootcamp Job Guarantee?

- How to Pay for Coding Bootcamp

- Ultimate Guide to Coding Bootcamp Loans

- Best Coding Bootcamp Scholarships and Grants

- Education Stipends for Coding Bootcamps

- Get Your Coding Bootcamp Sponsored by Your Employer

- GI Bill and Coding Bootcamps

- Tech Intevriews

- Our Enterprise Solution

- Connect With Us

- Publication

- Reskill America

- Partner With Us

- Resource Center

- Bachelor’s Degree

- Master’s Degree

The Top 10 Most Interesting Climate Change Research Topics

Finishing your environmental science degree may require you to write about climate change research topics. For example, students pursuing a career as environmental scientists may focus their research on environmental-climate sensitivity or those studying to become conservation scientists will focus on ways to improve the quality of natural resources.

Climate change research paper topics vary from anthropogenic climate to physical risks of abrupt climate change. Papers should focus on a specific climate change research question. Read on to learn more about examples of climate change research topics and questions.

Find your bootcamp match

What makes a strong climate change research topic.

A strong climate change research paper topic should be precise in order for others to understand your research. You must use research methods to find topics that discuss a concern about climate issues. Your broader topic should be of current importance and a well-defined discourse on climate change.

Tips for Choosing a Climate Change Research Topic

- Research what environmental scientists say. Environmental scientists study ecological problems. Their studies include the threat of climate change on environmental issues. Studies completed by these professionals are a good starting point.

- Use original research to review articles for sources. Starting with a general search is a good place to get ideas. However, as you begin to refine your search, use original research papers that have passed through the stage of peer review.

- Discover the current climatic conditions of the research area. The issue of climate change affects each area differently. Gather information on the current climate and historical climate conditions to help bolster your research.

- Consider current issues of climate change. You want your analyses on climate change to be current. Using historical data can help you delve deep into climate change effects. First, however, it needs to back up climate change risks.

- Research the climate model evaluation options. There are different approaches to climate change evaluation. Choosing the right climate model evaluation system will help solidify your research.

What’s the Difference Between a Research Topic and a Research Question?

A research topic is a broad area of study that can encompass several different issues. An example might be the key role of climate change in the United States. While this topic might make for a good paper, it is too broad and must be narrowed to be written effectively.

A research question narrows the topic down to one or two points. The question provides a framework from which to start building your paper. The answers to your research question create the substance of your paper as you report the findings.

How to Create Strong Climate Change Research Questions

To create a strong climate change research question, start settling on the broader topic. Once you decide on a topic, use your research skills and make notes about issues or debates that may make an interesting paper. Then, narrow your ideas down into a niche that you can address with theoretical or practical research.

Top 10 Climate Change Research Paper Topics

1. climate changes effect on agriculture.

Climate change’s effect on agriculture is a topic that has been studied for years. The concern is the major role of climate as it affects the growth of crops, such as the grains that the United States cultivates and trades on the world market. According to the scientific journal Nature , one primary concern is how the high levels of carbon dioxide can affect overall crops .

2. Economic Impact of Climate Change

Climate can have a negative effect on both local and global economies. While the costs may vary greatly, even a slight change could cost the United States a loss in the Global Domestic Product (GDP). For example, rising sea levels may damage the fiber optic infrastructure the world relies on for trade and communication.

3. Solutions for Reducing the Effect of Future Climate Conditions

Solutions for reducing the effect of future climate conditions range from reducing the reliance on fossil fuels to reducing the number of children you have. Some of these solutions to climate change are radical ideas and may not be accepted by the general population.

4. Federal Government Climate Policy

The United States government’s climate policy is extensive. The climate policy is the federal government’s action for climate change and how it hopes to make an impact. It includes adopting the use of electric vehicles instead of gas-powered cars. It also includes the use of alternative energy systems such as wind energy.

5. Understanding of Climate Change

Understanding climate change is a broad climate change research topic. With this, you can introduce different research methods for tracking climate change and showing a focused effect on specific areas, such as the impact on water availability in certain geographic areas.

6. Carbon Emissions Impact of Climate Change

Carbon emissions are a major factor in climate change. Due to the greenhouse effect they cause, the world is seeing a higher number of devastating weather events. An increase in the number and intensity of tsunamis, hurricanes, and tornados are some of the results.

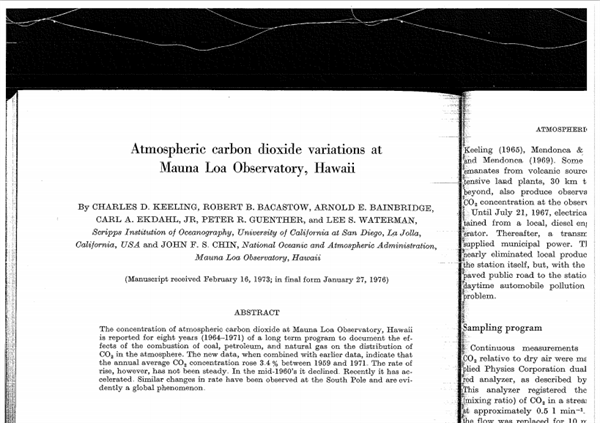

7. Evidence of Climate Change

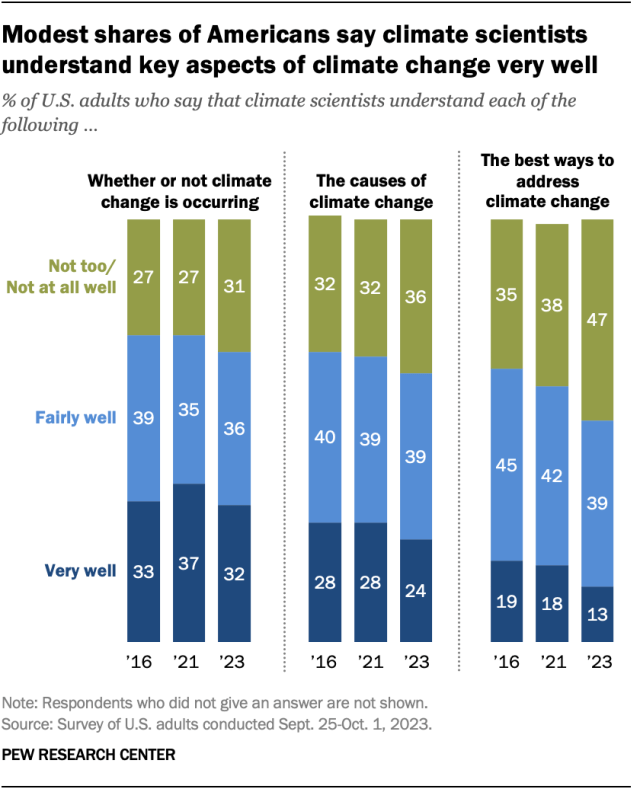

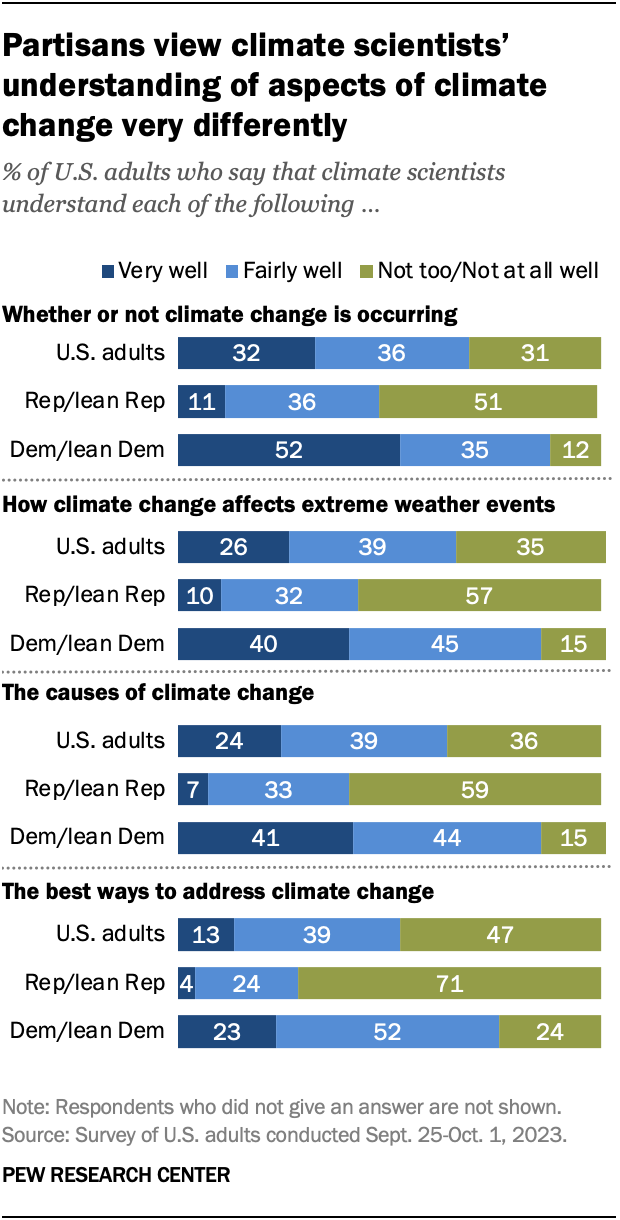

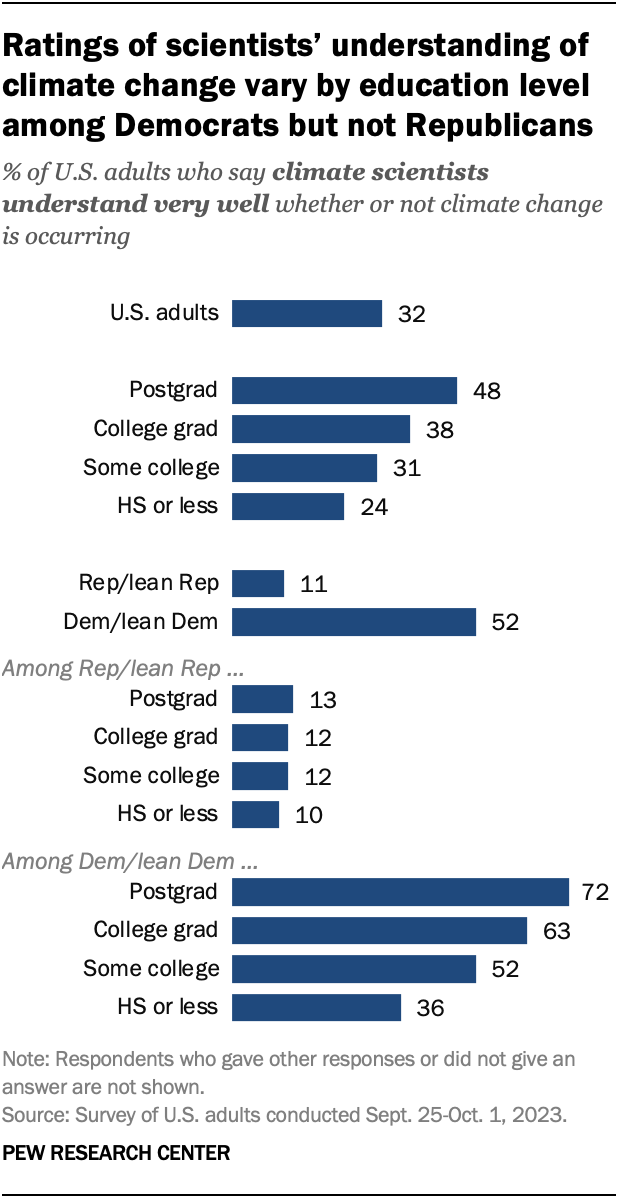

There is ample evidence of climate change available, thanks to the scientific community. However, some of these implications of climate change are hotly contested by those with poor views about climate scientists. Proof of climate change includes satellite images, ice cores, and retreating glaciers.

8. Cause and Mitigation of Climate Change

The causes of climate change can be either human activities or natural causes. Greenhouse gas emissions are an example of how human activities can alter the world’s climate. However, natural causes such as volcanic and solar activity are also issues. Mitigation plans for these effects may include options for both causes.

9. Health Threats and Climate Change

Climate change can have an adverse effect on human health. The impacts on health from climate change can include extreme heat, air pollution, and increasing allergies. The CDC warns these changes can cause respiratory threats, cardiovascular issues, and heat-related illnesses.

10. Industrial Pollution and the Effects of Climate Change

Just as car emissions can have an adverse effect on the climate, so can industrial pollution. It is one of the leading factors in greenhouse gas effects on average temperature. While the US has played a key role in curtailing industrial pollution, other countries need to follow suit to mitigate the negative impacts it causes.

Other Examples of Climate Change Research Topics & Questions

Climate change research topics.

- The challenge of climate change faced by the United States

- Climate change communication and social movements

- Global adaptation methods to climate change

- How climate change affects migration

- Capacity on climate change and the effect on biodiversity

Climate Change Research Questions

- What are some mitigation and adaptation to climate change options for farmers?

- How do alternative energy sources play a role in climate change?

- Do federal policies on climate change help reduce carbon emissions?

- What impacts of climate change affect the environment?

- Do climate change and social movements mean the end of travel?

Choosing the Right Climate Change Research Topic

Choosing the correct climate change research paper topic takes continuous research and refining. Your topic starts as a general overview of an area of climate change. Then, after extensive research, you can narrow it down to a specific question.

You need to ensure that your research is timely, however. For example, you don’t want to address the effects of climate change on natural resources from 15 or 20 years ago. Instead, you want to focus on views about climate change from resources within the last five years.

Climate Change Research Topics FAQ

A climate change research paper has five parts, beginning with introducing the problem and background before moving into a review of related sources. After reviewing, share methods and procedures, followed by data analysis . Finally, conclude with a summary and recommendations.

A thesis statement presents the topic of your paper to the reader. It also helps you as you begin to organize your paper, much like a mission statement. Therefore, your thesis statement may change during writing as you start to present your arguments.

According to the US Forest Service, climate change issues are related to topics regarding forest management, biodiversity, and species distribution. Climate change is a broad focus that affects many topics.

To write a research paper title, a good strategy is not to write the title right away. Instead, wait until the end after you finish everything else. Then use a short and to-the-point phrase that summarizes your document. Use keywords from the paper and avoid jargon.

About us: Career Karma is a platform designed to help job seekers find, research, and connect with job training programs to advance their careers. Learn about the CK publication .

What's Next?

Get matched with top bootcamps

Ask a question to our community, take our careers quiz.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Thesis Helpers

Find the best tips and advice to improve your writing. Or, have a top expert write your paper.

Top 100 Climate Change Topics To Write About

Climate change issues have continued to increase over the years. That’s because human activities like fossil fuel usage, excavation, and greenhouse emissions continue to drastically change the climate negatively. For instance, burning fossil fuels continues to release greenhouse emissions and carbon dioxide in large quantities. And the lower atmosphere of the earth traps these gasses thereby affecting the global climate. To enhance their awareness of the impact of global warming, educators ask learners to write academic papers and essays on different climate change topics.

According to statistics, global warming affects the climate in different ways. However, the earth has experienced a general temperature increase of 0.85 degrees centigrade over the last 100 years. Such statistics show that this increase will eventually pass the acceptable thresholds in the next 10 years or less. And this will have dire consequences on human health and the global climate. As such, writing a paper about a topic on climate change is a great way to educate the masses.

However, some learners have difficulties choosing topics for their papers and essays on climate change. That’s because this is a relatively new subject. Nevertheless, students that are pursuing ecology, political, and biology studies are conversant with this subject. If struggling to decide what to write about, consider this list of topics related to climate change.

Climate Change Topics for Short Essays

Perhaps, your educator has asked you to write a short essay on climate change. Maybe you’re yet to decide what to write about because every topic you think about seems to have been written about. In that case, use this list of climate change topics for inspiration. You can write about one of these topics or develop it to make it more unique.

- How climate change is responsible for the disappearing rainforest

- The effects of global warming on air quality within the urban areas

- Global warming and greenhouse emissions- Possible health risks

- Is climate change responsible for irregular weather patterns?

- How has climate change affected the food chain?

- The negative effects of climate change on human wellbeing

- How global warming affects agriculture

- How climate change works

- Why is climate change dangerous to human health?

- How to minimize global warming effects on human health

- How global warming affects the healthcare

- Effects of climate change of life quality in rural and urban areas

- How warmer temperatures support allergy-related illnesses

- How climate change is a risk to life on earth

- How climate change and natural disasters correlate

- How climate change affects the population of the earth

- How climate change relates to global warming

- How global warming has caused extreme heating in most urban areas

- How wildfires relate to climate change

- How ocean acidification and climate change affect the world’s habitat

These climate change essay topics cover different aspects of human activities and their effects on the earth’s ecosystem. As such, writing a research paper or essay on any of these topics requires extensive research and analysis of information. That’s the only way you can come up with a solid paper that will impress the educator to award you the top grade.

Climate Change Issues that Make for Good Topics

Maybe you want to research issues that relate to climate change. Most people may have not considered such issues but they are worthy of climate change debate topics. In that case, consider these issues when choosing your climate topics for papers and essays.

- Climate change and threat to natural biodiversity are equally important

- Climate change in Miami and Saudi Arabia- How the effects compare

- Climate change as a human activity’s effect on the environment

- Preventing climate change by protecting forests

- Climate change in China- How the country has declined to head to the global call about saving Mother Nature

- Common causes of climate change

- Common effects of climate change

- The definition of climate change

- What is anthropogenic climate change

- Describe climate change

- What drives climate change?

- Renewable energy sources and climate change

- Human and economics induced climate change

- Climate change biology

- Climate change and business

- Science, Spin, and climate change

- Climate change- How global warming affects populations

- Climate change and social concepts

- Extreme weather and climate change- How they relate

- Global warming as a complex issue in climate change

These are great climate change topics for research papers and essays. However, writing about these topics requires extensive research. You should also be ready to spend energy and time finding relevant and latest sources of information before you write about these topics.

Interesting Climate Change Topics for Papers and Essays

Perhaps, you want to write an essay or paper about something interesting. In that case, consider this list of interesting climate change research paper topics.

- Climate change across the globe- What experts say

- Development, climate change, and disaster reduction

- Critical review- Climate change and agriculture

- Schools should include climate change as a subject in geography courses

- Consumption and climate change- How the wind blows in Indiana

- How the United Nations responds to climate change

- Snowpack and climate change

- How climate change threatens global security

- The effects of climate change on coastal areas’ tourism

- How climate change relates to Queensland Australia’s floods

- How climate change affects the tourism and hospitality industry

- Possible strategies for addressing the effects of climate change on urban areas

- How climate change affects indigenous people

- How to avoid the threats of climate change

- How climate change affects coral triangle turtles

- Climate change drivers in the Asian countries

- Economic discourse analysis methodology in climate change

- How climate change affects New Hampshire businesses

- How climate change affects the life of an individual

- The economic cost of the effects of climate change

These are fantastic climate change paper topics to explore. Nevertheless, you must be ready to research your topic extensively before you start writing your academic paper or essay.

Major Topics on Climate Change for Academic Writing

Perhaps, you’re looking for topics related to climate change that you write major papers about. In that case, you should consider these global climate change topics.

- Early science on climate change

- How the world can manage the effects of climate change

- Environmental issues relating to climate change

- Views comparison about the climate change problem

- Asset-based community development and climate change

- Experts’ evaluation of climate change

- How science affects climate change

- How climate change affects the ocean life

- Scotland’s vulnerability to climate change

- How energy conservation can solve the climate change problem

- How climate change affects the world economy

- International collaboration and climate change

- International relations view on climate change

- How transportation affects climate change

- Climate change and technology

- Climate change policies and human rights

- Climate change from an anthropological perspective

- Climate change as an international security issue

- Role of the United Nations in addressing climate change

- Climate change and pollution

This category has some of the best climate change thesis topics. That’s because most people will be interested in reading papers on such topics due to their global perspectives. Nevertheless, you should prepare to spend a significant amount of time researching and writing about any of these topics on climate change.

Climate Change Topics for Presentation

Perhaps, you want to write papers on topics related to climate change for presentation purposes. In that case, you need topics that most people can resonate with. Here is a list of topics about climate change that will interest most people.

- How can humans stop global warming in the next ten years

- Could humans have stopped global warming a decade ago?

- How has the environment changed over the years and how has this change caused global warming?

- How did the Obama administration try to limit climate change?

- What is the influence of chemical engineering on global warming?

- How is urbanization connected to climate change?

- Theories that explain why some nations ignore climate change

- How global warming affects the rising sea levels

- How anthropogenic and natural climate change differ

- How the war against terrorism differs from the war on climate change

- How atmospheric change influences global climate change

- Negative effects of global climate change on Minnesota

- The greenhouse effect and ozone depletion

- How greenhouse affects the earth’s environment

- How can individuals reduce the emissions of greenhouse gasses

- How climate change will affect humans in their lifetime

- What are the social, physical, and economic effects of climate change

- Problems and solutions to climate change on the Pacific Ocean

- How climate change relates to species’ extinction

- How the phenomenon of denying climate change affects animals

This list prepared by our research helpers has some of the best essay topics on climate change. Pick one of these ideas, research it, and then compose a winning paper.

Make PhD experience your own

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Our Program Divisions

- Our Three Academies

- Government Affairs

- Statement on Diversity and Inclusion

- Our Study Process

- Conflict of Interest Policies and Procedures

- Project Comments and Information

- Read Our Expert Reports and Published Proceedings

- Explore PNAS, the Flagship Scientific Journal of NAS

- Access Transportation Research Board Publications

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Economic Recovery

- Fellowships and Grants

- Publications by Division

- Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education

- Division on Earth and Life Studies

- Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences

- Gulf Research Program

- Health and Medicine Division

- Policy and Global Affairs Division

- Transportation Research Board

- National Academy of Sciences

- National Academy of Engineering

- National Academy of Medicine

- Publications by Topic

- Agriculture

- Behavioral and Social Sciences

- Biography and Autobiography

- Biology and Life Sciences

- Computers and Information Technology

- Conflict and Security Issues

- Earth Sciences

- Energy and Energy Conservation

- Engineering and Technology

- Environment and Environmental Studies

- Food and Nutrition

- Health and Medicine

- Industry and Labor

- Math, Chemistry, and Physics

- Policy for Science and Technology

- Space and Aeronautics

- Surveys and Statistics

- Transportation and Infrastructure

- Searchable Collections

- New Releases

VIEW LARGER COVER

Climate Change Science

An analysis of some key questions.

The warming of the Earth has been the subject of intense debate and concern for many scientists, policy-makers, and citizens for at least the past decade. Climate Change Science: An Analysis of Some Key Questions , a new report by a committee of the National Research Council, characterizes the global warming trend over the last 100 years, and examines what may be in store for the 21st century and the extent to which warming may be attributable to human activity.

RESOURCES AT A GLANCE

- Press Release

- Earth Sciences — Climate, Weather and Meteorology

- Environment and Environmental Studies — Climate Change

Suggested Citation

National Research Council. 2001. Climate Change Science: An Analysis of Some Key Questions . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10139. Import this citation to: Bibtex EndNote Reference Manager

Publication Info

- Paperback: 978-0-309-07574-9

- Ebook: 978-0-309-18335-2

What is skim?

The Chapter Skim search tool presents what we've algorithmically identified as the most significant single chunk of text within every page in the chapter. You may select key terms to highlight them within pages of each chapter.

Copyright Information

The National Academies Press (NAP) has partnered with Copyright Clearance Center's Marketplace service to offer you a variety of options for reusing NAP content. Through Marketplace, you may request permission to reprint NAP content in another publication, course pack, secure website, or other media. Marketplace allows you to instantly obtain permission, pay related fees, and print a license directly from the NAP website. The complete terms and conditions of your reuse license can be found in the license agreement that will be made available to you during the online order process. To request permission through Marketplace you are required to create an account by filling out a simple online form. The following list describes license reuses offered by the NAP through Marketplace:

- Republish text, tables, figures, or images in print

- Post on a secure Intranet/Extranet website

- Use in a PowerPoint Presentation

- Distribute via CD-ROM

Click here to obtain permission for the above reuses. If you have questions or comments concerning the Marketplace service, please contact:

Marketplace Support International +1.978.646.2600 US Toll Free +1.855.239.3415 E-mail: [email protected] marketplace.copyright.com

To request permission to distribute a PDF, please contact our Customer Service Department at [email protected] .

What is a prepublication?

An uncorrected copy, or prepublication, is an uncorrected proof of the book. We publish prepublications to facilitate timely access to the committee's findings.

What happens when I pre-order?

The final version of this book has not been published yet. You can pre-order a copy of the book and we will send it to you when it becomes available. We will not charge you for the book until it ships. Pricing for a pre-ordered book is estimated and subject to change. All backorders will be released at the final established price. As a courtesy, if the price increases by more than $3.00 we will notify you. If the price decreases, we will simply charge the lower price. Applicable discounts will be extended.

Downloading and Using eBooks from NAP

What is an ebook.

An ebook is one of two file formats that are intended to be used with e-reader devices and apps such as Amazon Kindle or Apple iBooks.

Why is an eBook better than a PDF?

A PDF is a digital representation of the print book, so while it can be loaded into most e-reader programs, it doesn't allow for resizable text or advanced, interactive functionality. The eBook is optimized for e-reader devices and apps, which means that it offers a much better digital reading experience than a PDF, including resizable text and interactive features (when available).

Where do I get eBook files?

eBook files are now available for a large number of reports on the NAP.edu website. If an eBook is available, you'll see the option to purchase it on the book page.

View more FAQ's about Ebooks

Types of Publications

Consensus Study Report: Consensus Study Reports published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine document the evidence-based consensus on the study’s statement of task by an authoring committee of experts. Reports typically include findings, conclusions, and recommendations based on information gathered by the committee and the committee’s deliberations. Each report has been subjected to a rigorous and independent peer-review process and it represents the position of the National Academies on the statement of task.

News from the Columbia Climate School

Six Tough Questions About Climate Change

Whenever the focus is on climate change, as it is right now at the Paris climate conference , tough questions are asked concerning the costs of cutting carbon emissions, the feasibility of transitioning to renewable energy, and whether it’s already too late to do anything about climate change. We posed these questions to Laura Segafredo , manager for the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project . The decarbonization project comprises energy research teams from 16 of the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitting countries that are developing concrete strategies to reduce emissions in their countries. The Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project is an initiative of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network .

- Will the actions we take today be enough to forestall the direct impacts of climate change? Or is it too little too late?

There is still time and room for limiting climate change within the 2˚C limit that scientists consider relatively safe, and that countries endorsed in Copenhagen and Cancun. But clearly the window is closing quickly. I think that the most important message is that we need to start really, really soon, putting the world on a trajectory of stabilizing and reducing emissions. The temperature change has a direct relationship with the cumulative amount of emissions that are in the atmosphere, so the more we keep emitting at the pace that we are emitting today, the more steeply we will have to go on a downward trajectory and the more expensive it will be.

Today we are already experiencing an average change in global temperature of .8˚. With the cumulative amount of emissions that we are going to emit into the atmosphere over the next years, we will easily reach 1.5˚ without even trying to change that trajectory.

Two degrees might still be doable, but it requires significant political will and fast action. And even 2˚ is a significant amount of warming for the planet, and will have consequences in terms of sea level rise, ecosystem changes, possible extinctions of species, displacements of people, diseases, agriculture productivity changes, health related effects and more. But if we can contain global warming within those 2˚, we can manage those effects. I think that’s really the message of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports—that’s why the 2˚ limit was chosen, in a sense. It’s a level of warming where we can manage the risks and the consequences. Anything beyond that would be much, much worse.

- Will taking action make our lives better or safer, or will it only make a difference to future generations?

It will make our lives better and safer for sure. For example, let’s think about what it means to replace a coal power plant with a cleaner form of energy like wind or solar. People that live around the coal power plant are going to have a lot less air pollution, which means less asthma for children, and less time wasted because of chronic or acute diseases. In developing countries, you’re talking about potentially millions of lives saved by replacing dirty fossil fuel based power generation with clean energy.

It will also have important consequences for agricultural productivity. There’s a big risk that with the concentration of carbon and other gases in the atmosphere, agricultural yields will be reduced, so preventing that means more food for everyone.

And then think about cities. If you didn’t have all that pollution from cars, we could live in cities that are less noisy, where the air’s much better, and have potentially better transportation. We could live in better buildings where appliances are more efficient. And investing in energy efficiency would basically leave more money in our pockets. So there are a lot of benefits that we can reap almost immediately, and that’s without even considering the biggest benefit—leaving a planet in decent condition for future generations.

- How will measures to cut carbon emissions affect my life in terms of cost?

To build a climate resilient economy, we need to incorporate the three pillars of energy system transformation that we focus on in all the deep decarbonization pathways. Number one is improving energy efficiency in every part of the economy—buildings, what we use inside buildings, appliances, industrial processes, cars…everything you can think of can perform the same service, but using less energy. What that means is that you will have a slight increase in the price in the form of a small investment up front, like insulating your windows or buying a more efficient car, but you will end up saving a lot more money over the life of the equipment in terms of decreased energy costs.

The second pillar is making electricity, the power sector, carbon-free by replacing dirty power generation with clean power sources. That’s clearly going to cost a little money, but those costs are coming down so quickly. In fact there are already a lot of clean technologies that are at cost parity with fossil fuels— for example, onshore wind is already as competitive as gas—and those costs are only coming down in the future. We can also expect that there are going to be newer technologies. But in any event, the fact that we’re going to use less power because of the first pillar should actually make it a wash in terms of cost.

The Australian deep decarbonization teams have estimated that even with the increased costs of cleaner cars, and more efficient equipment for the home, etc., when the power system transitions to where it’s zero carbon, you still have savings on your energy bills compared to the previous situation.

The third pillar that we think about are clean fuels, essentially zero-carbon fuels. So we either need to electrify everything— like cars and heating, once the power sector is free of carbon—or have low-carbon fuels to power things that cannot be electrified, such as airplanes or big trucks. But once you have efficiency, these types of equipment are also more efficient, and you should be spending less money on energy.

Saving money depends on the three pillars together, thinking about all this as a whole system.

- Given that renewable sources provide only a small percentage of our energy and that nuclear power is so expensive, what can we realistically do to get off fossil fuels as soon as possible?

There are a lot of studies that have been done for the U.S. and for Europe that show that it’s very realistic to think of a power sector that is almost entirely powered by renewables by 2050 or so. It’s actually feasible—and this considers all the issues with intermittency, dealing with the networks, and whatever else represents a technological barrier—that’s all included in these studies. There’s also the assumption that energy storage, like batteries, will be cheaper in the future.

That is the future, but 2050 is not that far away. 35 years for an energy transition is not a long time. It’s important that this transition start now with the right policy incentives in place. We need to make sure that cars are more efficient, that buildings are more efficient, that cities are built with more public transit so less fossil fuels are needed to transport people from one place to another.

I don’t want people to think that because we’re looking at 2050, that means that we can wait—in order to be almost carbon free by 2050, or close to that target, we need to act fast and start now.

- Will the remedies to climate change be worse than the disease? Will it drive more people into poverty with higher costs?

I actually think the opposite is true. If we just let climate go the way we are doing today by continuing business as usual, that will drive many people into poverty. There’s a clear relationship between climate change and changing weather patterns, so more significant and frequent extreme weather events, including droughts, will affect the livelihoods of a large portion of the world population. Once you have droughts or significant weather events like extreme precipitation, you tend to see displacements of people, which create conflict, and conflict creates disease.

I think Syria is a good example of the world that we might be going towards if we don’t do anything about climate change. Syria is experiencing a once-in-a-century drought, and there’s a significant amount of desertification going on in those areas, so you’re looking at more and more arid areas. That affects agriculture, so people have moved from the countryside to the cities and that has created a lot of pressure on the cities. The conflict in Syria is very much related to the drought, and the drought can be ascribed to climate change.

And consider the ramifications of the Syrian crisis: the refugee crisis in Europe, terrorism, security concerns and 7 million-plus people displaced. I think that that’s the world that we’re going towards. And in a world like that, when you have to worry about people being safe and alive, you certainly cannot guarantee wealth and better well-being, or education and health.

- So finally, doing what needs to be done to combat climate change all comes down to political will?

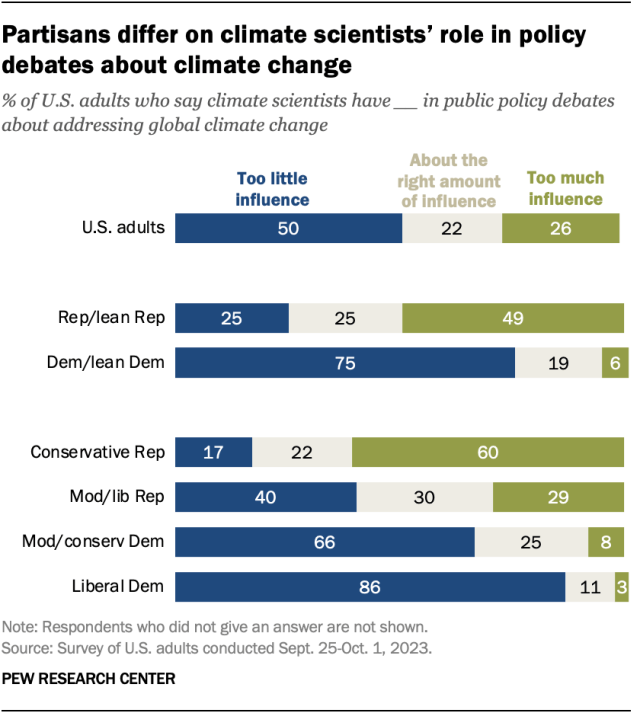

The majority of the American public now believe that climate change is real, that it’s human induced and that we should do something about it.

But there’s seems to be a disconnect between what these numbers seem to indicate and what the political discourse is like… I can’t understand it, yet it seems to be the situation.

I’m a little concerned because other more immediate concerns like terrorism and safety always come first. Because the effects of climate change are going to be felt a little further away, people think that we can always put it off. The Department of Defense, its top-level people, have made the connection between climate change and conflict over the next few decades. That’s why I would argue that Syria is actually a really good example to remind us that if we are experiencing security issues today, it’s also because of environmental problems. We cannot ignore them.

The reality is that we need to do something about climate change fast—we don’t have time to fight this over the next 20 years. We have to agree on this soon and move forward and not waste another 10 years debating.

Read the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project 2015 report . The full report will be released Dec. 2.

Laura Segafredo was a senior economist at the ClimateWorks Foundation, where she focused on best practice energy policies and their impact on emission trajectories. She was a lead author of the 2012 UNEP Emissions Gap Report and of the Green Growth in Practice Assessment Report. Before joining ClimateWorks, Segafredo was a research economist at Electricité de France in Paris.

She obtained her Ph.D. in energy studies and her BA in economics from the University of Padova (Italy), and her MSc in economics from the University of Toulouse (France).

Related Posts

Solar Geoengineering To Cool the Planet: Is It Worth the Risks?

Army Veteran and Environmental Advocate: A Sustainability Science Student’s Journey to Columbia

Sustainable Development Program Hosts Annual Alumni Career Conversations Panel

Celebrate over 50 years of Earth Day with us all month long! Visit our Earth Day website for ideas, resources, and inspiration.

Many find low wages prohibits saving. Changing personal vehicles and heating systems costs. Will there be financial support for people on low wages?

The energy innovation and dividend bill has already been introduced in the house. It’s a carbon fee and dividend plan. The carbon fee rises every year and 100% of it goes back directly into the hands of the people by a check each month. This helps offset rising costs, especially for lower income folks.

81 cosponsors now Tell your rep in Congress to support this HR 763!

Results show that yields for all four crops grown at levels of carbon dioxide remaining at 2000 levels would experience severe declines in yield due to higher temperatures and drier conditions. But when grown at doubled carbon dioxide levels, all four crops fare better due to increased photosynthesis and crop water productivity, partially offsetting the impacts from those adverse climate changes. For wheat and soybean crops, in terms of yield the median negative impacts are fully compensated, and rice crops recoup up to 90 percent and maize up to 60 percent of their losses.

When is Russia, China, and Mexico going to work toward a better environment instead of the United States trying to do it all? They continue to pollute like they have for years. Who is going to stop the deforestation of the rain forest?

I’m curious if climate change has any effect on seismic activity. It seems with ice melting on the poles and increasing water dispersement and temp of that water, it might cause the plates to shift to compensate. Is there any evidence of this?

this isn’t because of doldrums or jet streams. the pattern keeps having the same action. we must save trees :3

How long do we have, before it’s too late?

Climate Change isn’t nearly as big of a deal as everyone makes it out to be. Meaning no disrespect to the author, but I really don’t see how this is something that we should be worrying about given that one human recycling their soda cans or getting their old phone refurbished rather than dumping it isn’t going to restore the polar ice caps or lower the temperature of the planet. And supposedly agriculture is the problem, but I point-blank refuse to give up my beef night, or bacon and eggs for breakfast on Saturdays. Also, nuclear power is supposed to be a solution, but the building of the power plants is going to add more greenhouse gases than the plant will take out. The whole planet needs a reality check. Earth isn’t going to explode because it’s slightly hotter than it used to be!

Thank you and I need in your help

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter →

Researching Climate Change

Climate change research involves numerous disciplines of Earth system science as well as technology, engineering, and programming. Some major areas of climate change research include water, energy, ecosystems, air quality, solar physics, glaciology, human health, wildfires, and land use.

To have a complete picture of how the climate changes and how these changes affect the Earth, scientists make direct measurements of climate using weather instruments. They also look at proxy data that gives us clues about climate conditions from prehistoric times. And they use models of the Earth system to predict how the climate will change in the future.

Measurements of modern climate change

Because climate describes the weather conditions averaged over a long period of time (typically 30 years), much of the same information gathered about weather is used to research climate. Temperature is measured every day at thousands of locations around the world. This data is used to calculate average global temperatures . Changes in temperature patterns are a strong indicator of how much the climate is changing. Because we have thousands of temperature measurements, we know that record high temperatures are increasing across the globe, which is a sign that the climate is warming. Climatologists also look at changes in precipitation, the length and frequency of drought, as well as the number of days that rivers are at flood stage to understand how the climate is changing. Winds and other direct measures of climate contribute to climate change research as well.

This map shows the location of weather stations across the Earth. Continuous data from thousands of stations is important for climate change research.

Using proxy data to understand climate change in the past

Throughout Earth's 4.6 billion years, the climate has changed drastically, including periods that were much colder and much warmer than the climate today. But how do we know about the climate from prehistoric times ? Researchers decipher clues within the Earth to help reconstruct past environments based on our understanding of environments today. Proxy data can take the form of fossils, sediment layers, tree rings , coral, and ice cores. These proxies contain evidence of past environments. For example, marine fossils and ocean seafloor sediment preserved in rock layers from around 80 million years ago (the Cretaceous Period) indicate that North America was mostly covered in water. The high sea levels were due to a much warmer climate when all of the polar ice sheets had melted. We also find fossil vegetation and pollen records indicating that forests covered the polar regions during this same time period. The existence of multiple types of proxy data from different locations, often from overlapping time periods, strengthens our understanding of past climates.

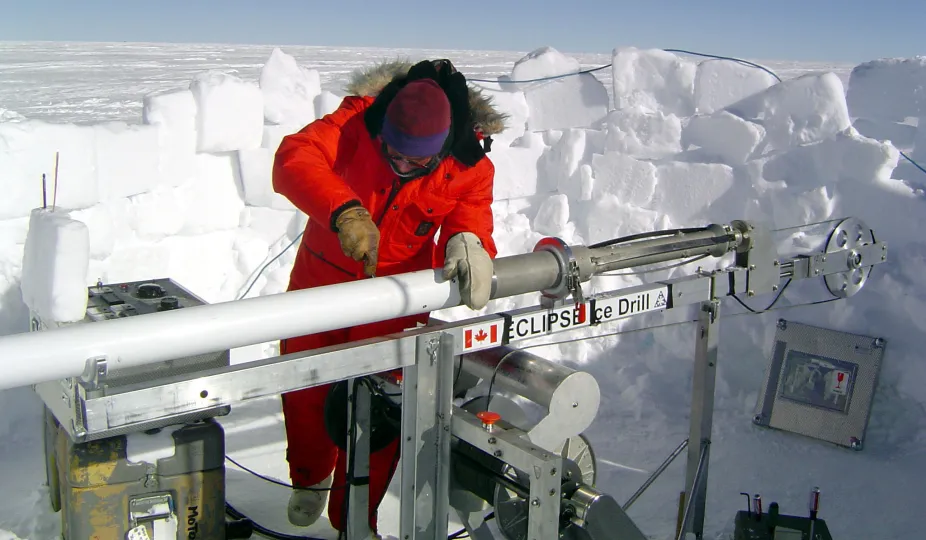

Ice core drilling in the Arctic provides proxy evidence of paleoclimate conditions.

National Snow and Ice Data Center

Using models to project future climate change

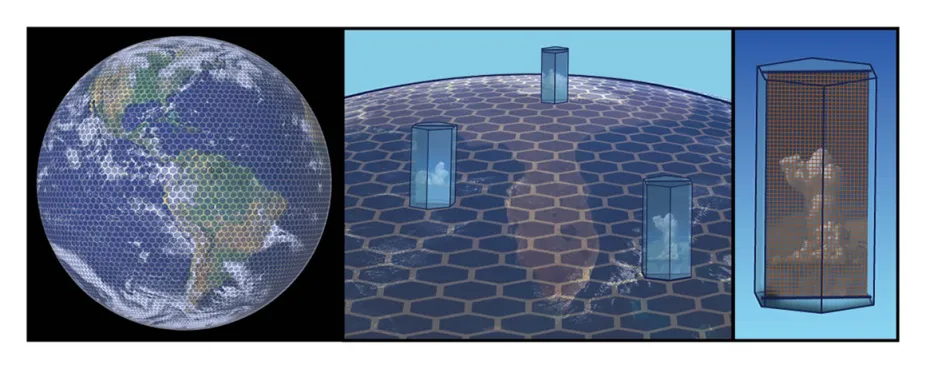

Scientists use models of the Earth to figure out how climate will likely change in the future. These models, which are simulations of Earth, include equations that describe everything from how the winds blow to how sea ice reflects sunlight and how forests take up carbon dioxide. In-depth knowledge of how each part of the Earth functions is needed to write the equations that represent each part within the model. Understanding climate change in both the present and the past helps to create computational models that can predict how the climate system might change in the future.

While scientists work hard to ensure that climate models are as accurate as possible, the models are unable to predict exactly how the climate will change in the future because some things are unknown, namely how much humans will change (or not change) behaviors that contribute to climate warming. Scientists run the models with different scenarios to account for a range of possibilities. For example, running the models to show how the climate will respond if we reduce fossil fuel emissions by different amounts can help us prepare for the many impacts that a changing climate has on the Earth.

Climate models keep track of how parameters change from place to place using a grid pattern on the Earth’s surface. The environmental conditions within each hexagon-shaped area are programmed into the model. More detailed models have smaller hexagons.

Studying the impacts of climate change

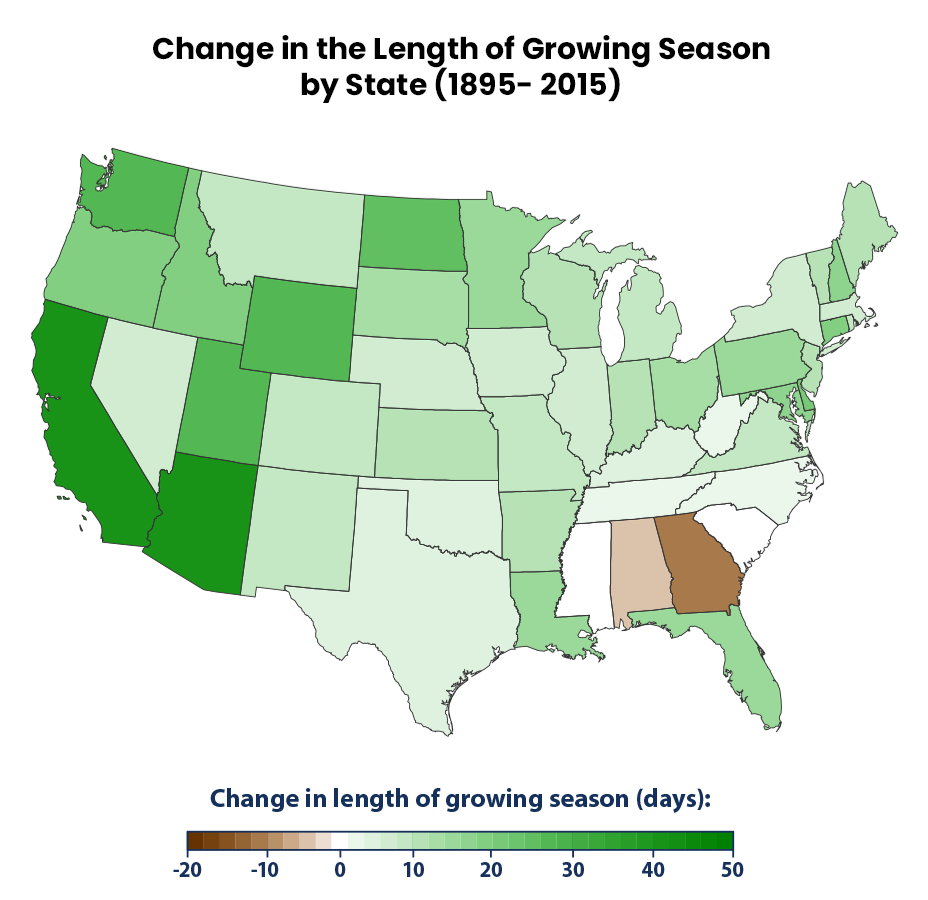

From monitoring changes in tropical coral reefs to changes in glacial ice, keeping track of how climate change is affecting the planet is important for adapting to the future. Scientists who monitor the environment report stronger and more frequent storms, changing weather patterns, a longer growing season in some locations, and changes in the distribution of plants and migratory animals. Monitoring how climate change is affecting our world can help identify new threats to human health as the ranges of insect-borne diseases change and as drought-prone regions expand.

Many different areas of research, from meteorology to oceanography, epidemiology to agriculture, and even fields such as sociology and economics, have a role to play in terms of researching both how the climate is changing and the impacts of climate change.

The average length of the growing season in the lower 48 states has increased by almost two weeks since the late 1800s, a result of the changing climate. Researchers study how this change in the growing season impacts humans and the Earth. Credit: EPA

© 2021 UCAR

- How Climate Works

- History of Climate Science Research

- Investigating Past Climates

- Climate Modeling

- Fast Computers and Complex Climate Models

- Visualizing Weather and Climate

- IPCC: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- From Dog Walking To Weather And Climate

- Satellite Signals from Space: Smart Science for Understanding Weather and Climate

Loading metrics

Open Access

Climate change mitigation and Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence and research gaps

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Global Centre for Environment and Energy, Ahmedabad University, Ahmedabad, India

Roles Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Roles Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Climate Economics and Risk Management, Department of Technology, Management and Economics, Technical University of Denmark, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark

- Minal Pathak,

- Shaurya Patel,

- Shreya Some

Published: March 4, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000366

- Reader Comments

Citation: Pathak M, Patel S, Some S (2024) Climate change mitigation and Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence and research gaps. PLOS Clim 3(3): e0000366. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000366

Editor: Jamie Males, PLOS Climate, UNITED KINGDOM

Copyright: © 2024 Pathak et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Never in the past three decades have the interlinkages between sustainable development and climate change been more pressing. The projected date when the remaining carbon budget will be exhausted if continuing at the current rate of emissions [ 1 ] is estimated to be around 2030- which also coincides with the timeline for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Recent global assessments clearly show the collective global performance on the targets relating to climate change, biodiversity and SDGs is abysmally poor [ 2 , 3 ]. Urgent efforts are needed to achieve both deep and rapid emissions reductions and to meet the SDGs to set the world on a pathway towards sustainable development.

The appreciation of interconnections between climate change and equity and sustainable development is not recent. In 1992, Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was restructured with a mandate to assess cross-cutting economic and other issues related to climate change including placing socio-economic perspectives in the context of sustainable development. IPCC’s Second Assessment Report in 1995 explicitly highlighted the different starting points of countries, trade-offs between economic growth and sustainability, distributional impacts of mitigation and adaptation actions and issues of intertemporal equity. This understanding has further deepened since then. Successive IPCC reports have highlighted the implications of efforts aimed at achieving targets under Climate Action (SDG 13) on SDGs [ 2 , 4 , 5 ]. There is now more evidence to show synergies of several climate actions with SDGs outweigh the trade-offs [ 6 ] Such actions include active transport, passive building design, clean energy, circular economy and urban green and blue infrastructure ( Fig 1 ) [ 7 ].

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000366.g001

A quick literature search on Scopus for papers focusing on climate change mitigation and SDGs showed 433 papers (Scopus search using search strings for each individual SDGs, for example: (TITLE-ABS-KEY ("SDG 1" OR "SDG1") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ("Climate") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ("mitigation" OR "mitigate"))). SDG 7 (Affordable and clean energy), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and 15 (Life on Land) were the most studied while SDGs 4 (Quality Education), 5 (Gender Equality), 10 (Reduced inequality) and 16 (Peace, Justice and strong institutions) received less attention.

Despite numerous studies, there’s limited evidence of the SDGs being perceived as a valuable tool for making decisions regarding climate action. Firstly, many of the existing studies highlight the potential of mitigation actions supporting SDG achievement through theoretical or modelled methods with few empirical studies demonstrating ex-post evaluation of specific interventions. In particular, there is limited literature on trade-offs and understanding of distributional effects for specific groups [ 8 ]. Secondly, a study on mapping SDG interactions of mitigation actions would not necessarily reveal the full picture. For example, urban public transport could show potential synergies with multiple SDGs however, it wouldn’t necessarily provide evidence on whether benefits could accrue to the most vulnerable groups. Similarly, a new urban transit system could have potential synergies with SDGs 3, 6, 9 and 11, however, this would fail to capture the near-term trade-offs e.g. relocation or costs or emissions.

It becomes more challenging when a particular action can result in mixed impacts, presenting both synergies and trade-offs across indicators within the same SDG. For example, while renewable energy can create green employment opportunities (synergy SDG 8 Target 8.5), it remains uncertain whether these jobs will ensure a safe and secure working environment for all workers throughout the supply chain (trade-off SDG 8, target 8.8). Mitigation options often work across sectors and systems and such interactions are not yet fully dealt with in existing studies.

Additionally, there are gaps in studies and available data for various crucial indicators worldwide, [ 6 ] which complicates the comprehensive assessment of comparing these key indicators across different countries, projects or entities. For instance, the Sustainable Development Report 2023 (Includes time-series data for 122 SDG indicators (out of 169 indicators) for 193 UN member states.) which measures progress across indicators for UN member states compiles data for 3 indicators to construct the index for SDG 13—all of which are related to emissions. Adaptation-related indicators are missing. Finally, studies do not cover temporal and spatial dimensions or the status of these interactions for alternate warming scenarios.

What does this mean for the scientific community?

Addressing the gaps identified presents an opportunity to enhance our understanding of progress towards SDGs and reduce missed opportunities [ 9 , 10 ]. Action that takes into account co-impacts can increase efficiency, reduce costs and support early and ambitious climate action, particularly in developing countries where there are simultaneous development priorities [ 11 ].

A business-as-usual approach to understanding mitigation SDG interactions has made progress but this is not enough. Data, indicators and methodologies, resources, the huge scope of SDGs, limitations of capturing non-measurable development dimensions and capacity constraints remain major challenges for in-depth research in this area [ 12 , 13 ]. New research therefore must focus on the SDGs and targets that have received limited attention and find ways to generate and report data ensuring access and transparency. Where specific data is not available, alternative approaches are needed for e.g. establishing reliable assumptions for utilizing proxy data through expert engagement. Developing indices specific to each goal and setting up reporting guidelines is essential for comparing progress. Failure to report the complete set of indicators limits comparability across goals and targets, and risks missing key priority areas.

Future research needs to focus on comprehensive assessments. For example, demonstrating how, where and to what speed and scale the implementation of a particular intervention resulted in synergies or trade-offs and whether these impacts are sustained. Similarly, going beyond acknowledging trade-offs towards a deeper understanding of what the trade-offs are, for which groups and whether and how these were resolved particularly in relation to questions around power and politics. In-depth studies require both time and resources. Funding needs to be directed to interdisciplinary research as well as building capacity of researchers to undertake such assessments. Quantitative studies involving new tools or modeling exercises, if complemented by qualitative approaches, can deliver more useful insights on synergies and trade-offs, particularly in situations where data is limited. Research institutions and universities can contribute by creating standardized templates and guidelines, as well as consistently reporting data using these templates.

Climate change mitigation research relies significantly on Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) to provide a comprehensive perspective on the interactions between socio-economic systems and earth systems. Existing models do not fully capture all development dimensions [ 14 ] or climate change adaptation though efforts are underway. Future research can focus on developing SD/G-compatible scenario storylines that prioritize development. More work is needed on variables and assumptions to better incorporate equity and justice issues [ 15 ] Modeling teams need to work closely with experts on various aspects of adaptation and sustainable development, including poverty, urbanisation, human well-being and biodiversity.

In conclusion, research frameworks and practices to assess mitigation SDG interactions are inadequate in their present form. Given the urgency, researchers and funders need to move away from business-as-usual approaches towards more in-depth assessments that significantly advance knowledge.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 2. IPCC. Climate Change 2023—Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2023 pp. 1–85. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6syr/pdf/IPCC_AR6_SYR_LongerReport.pdf

- 3. Sachs JD, Lafortune G, Fuller G, Drumm E. Sustainable Development Report 2023: Implementing the SDG Stimulus. Dublin University Press; 2023 pp. 1–546.

- 4. IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5°C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 2018.

- 5. IPCC. Climate Change 2022—Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 1st ed. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2022.

- 6. United Nations Synergy Solutions for a World in Crisis: Tackling Climate and SDG Action Together. Report on Stregnthening the Evidence Base. USA: United Nations; 2023 pp. 1–100. https://www.saoicmai.in/elibrary/first-global-report-on-climate-and-sdg-synergies.pdf

- 9. Dubash N, Mitchell C, Boasson EL, Borbor-Cordova MJ, Fifita S, Haites E, et al. National and Sub-national Policies and Institutions. 1st ed. In: Shukla P, Skea J, Slade R, Al Khourdajie A, van Diemen R, McCollum D, et al., editors. Climate Change 2022—Mitigation of Climate Change. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 2022. pp. 1355–1450.

- PubMed/NCBI

- 15. IPCC. IPCC Workshop on the Use of Scenarios in the Sixth Assessment Report and Subsequent Assessments. Thailand: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2023 pp. 1–76. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2023/07/IPCC_2023_Workshop_Report_Scenarios.pdf

- Climate Change - A Global Issue

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- Research Guides

- A Global Issue

- At the United Nations

- Major Reports

- Books & Journals

- Consulting the Experts

- Keeping up to date

- Data & Statistics

This site contains links and references to third-party databases, web sites, books and articles. It does not imply the endorsement of the content by the United Nations.

What is climate change?

- Background Climate change is an urgent global challenge with long-term implications for the sustainable development of all countries.

Exploring the Topic

- Climate.gov NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) maintains this gateway to peer-reviewed information on climate change for various audiences, from the layperson to teachers to scientists to planners and policy makers. Provides access to relevant data sets from a number of agencies, including the National Climatic Data Center and the NOAA Climate Prediction Center.

- Eldis resource guide on climate change (IDS) The Eldis website is maintained by the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex. It facilitates the sharing of information on development issues by aggregating information materials from reputable sources into the resource guide on climate change. It offers tools to create online communities for development practitioners; several such communities exist to discuss specific aspects of climate change. Eldis topic editors compile email newsletters, so-called reporters, including the “Climate Change and Development” reporter.

- IIED - International Institute for Environment and Development Well-established policy research institute that offers an online library of information materials on climate change and related topics, such as energy, biodiversity and forests. Publicizes its research output through email newsletters and on various social media channels.

- IISD - International Institute for Sustainable Development IISD offers a searchable and browsable knowledge base of its publications and video on climate change. IISDs LINKAGES reporting services closely monitor major international climate change meetings, including those of the IPCC and under the UNFCCC. IISD publishes the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, hosts the climate-l electronic mailing list and publicizes its work on twitter and Facebook.

Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change

Watch this video by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to learn more about what is at stake and what actions need to be taken to mitigate the impact of climate change globally.

More videos on other aspects of climate change can be found on the IPCC's YouTube page .

Climate Change FAQs

Check out what questions others have asked about climate change and related issues in Ask DAG , our FAQ database.

Related Research Guides

UN Research Guides on issues related to environment:

- Climate Change - A Global Issue by Dag Hammarskjöld Library Last Updated Jan 5, 2024 8886 views this year

- UN Documentation: Environment by Dag Hammarskjöld Library Last Updated Dec 29, 2023 6617 views this year

Other resource guides on climate change and related topics:

- Peace Palace Library: Environmental Law Starting point for research in the field of International Environmental Law provided by the Peace Palace Library in The Hague.

- Next: At the United Nations >>

- Last Updated: Jan 5, 2024 5:23 PM

- URL: https://research.un.org/en/climate-change

- Share full article

The Science of Climate Change Explained: Facts, Evidence and Proof

Definitive answers to the big questions.

Credit... Photo Illustration by Andrea D'Aquino

Supported by

By Julia Rosen

Ms. Rosen is a journalist with a Ph.D. in geology. Her research involved studying ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica to understand past climate changes.

- Published April 19, 2021 Updated Nov. 6, 2021

The science of climate change is more solid and widely agreed upon than you might think. But the scope of the topic, as well as rampant disinformation, can make it hard to separate fact from fiction. Here, we’ve done our best to present you with not only the most accurate scientific information, but also an explanation of how we know it.

How do we know climate change is really happening?

How much agreement is there among scientists about climate change, do we really only have 150 years of climate data how is that enough to tell us about centuries of change, how do we know climate change is caused by humans, since greenhouse gases occur naturally, how do we know they’re causing earth’s temperature to rise, why should we be worried that the planet has warmed 2°f since the 1800s, is climate change a part of the planet’s natural warming and cooling cycles, how do we know global warming is not because of the sun or volcanoes, how can winters and certain places be getting colder if the planet is warming, wildfires and bad weather have always happened. how do we know there’s a connection to climate change, how bad are the effects of climate change going to be, what will it cost to do something about climate change, versus doing nothing.

Climate change is often cast as a prediction made by complicated computer models. But the scientific basis for climate change is much broader, and models are actually only one part of it (and, for what it’s worth, they’re surprisingly accurate ).

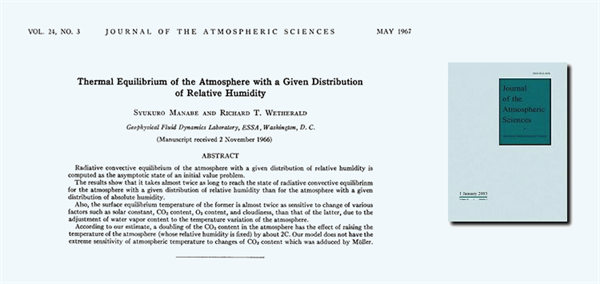

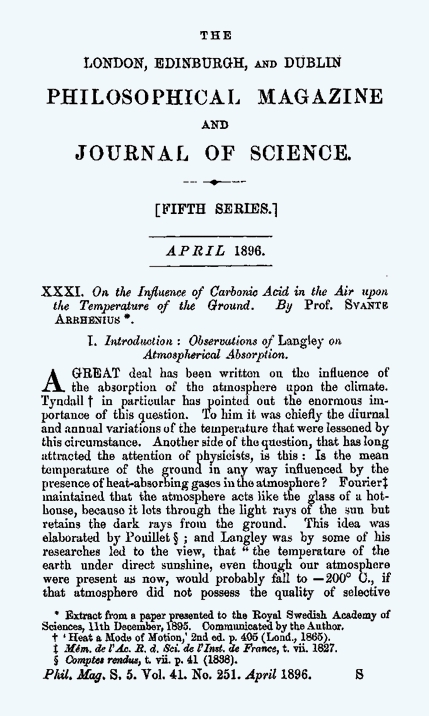

For more than a century , scientists have understood the basic physics behind why greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide cause warming. These gases make up just a small fraction of the atmosphere but exert outsized control on Earth’s climate by trapping some of the planet’s heat before it escapes into space. This greenhouse effect is important: It’s why a planet so far from the sun has liquid water and life!

However, during the Industrial Revolution, people started burning coal and other fossil fuels to power factories, smelters and steam engines, which added more greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Ever since, human activities have been heating the planet.

We know this is true thanks to an overwhelming body of evidence that begins with temperature measurements taken at weather stations and on ships starting in the mid-1800s. Later, scientists began tracking surface temperatures with satellites and looking for clues about climate change in geologic records. Together, these data all tell the same story: Earth is getting hotter.

Average global temperatures have increased by 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit, or 1.2 degrees Celsius, since 1880, with the greatest changes happening in the late 20th century. Land areas have warmed more than the sea surface and the Arctic has warmed the most — by more than 4 degrees Fahrenheit just since the 1960s. Temperature extremes have also shifted. In the United States, daily record highs now outnumber record lows two-to-one.

Where it was cooler or warmer in 2020 compared with the middle of the 20th century

This warming is unprecedented in recent geologic history. A famous illustration, first published in 1998 and often called the hockey-stick graph, shows how temperatures remained fairly flat for centuries (the shaft of the stick) before turning sharply upward (the blade). It’s based on data from tree rings, ice cores and other natural indicators. And the basic picture , which has withstood decades of scrutiny from climate scientists and contrarians alike, shows that Earth is hotter today than it’s been in at least 1,000 years, and probably much longer.

In fact, surface temperatures actually mask the true scale of climate change, because the ocean has absorbed 90 percent of the heat trapped by greenhouse gases . Measurements collected over the last six decades by oceanographic expeditions and networks of floating instruments show that every layer of the ocean is warming up. According to one study , the ocean has absorbed as much heat between 1997 and 2015 as it did in the previous 130 years.

We also know that climate change is happening because we see the effects everywhere. Ice sheets and glaciers are shrinking while sea levels are rising. Arctic sea ice is disappearing. In the spring, snow melts sooner and plants flower earlier. Animals are moving to higher elevations and latitudes to find cooler conditions. And droughts, floods and wildfires have all gotten more extreme. Models predicted many of these changes, but observations show they are now coming to pass.

Back to top .

There’s no denying that scientists love a good, old-fashioned argument. But when it comes to climate change, there is virtually no debate: Numerous studies have found that more than 90 percent of scientists who study Earth’s climate agree that the planet is warming and that humans are the primary cause. Most major scientific bodies, from NASA to the World Meteorological Organization , endorse this view. That’s an astounding level of consensus given the contrarian, competitive nature of the scientific enterprise, where questions like what killed the dinosaurs remain bitterly contested .

Scientific agreement about climate change started to emerge in the late 1980s, when the influence of human-caused warming began to rise above natural climate variability. By 1991, two-thirds of earth and atmospheric scientists surveyed for an early consensus study said that they accepted the idea of anthropogenic global warming. And by 1995, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a famously conservative body that periodically takes stock of the state of scientific knowledge, concluded that “the balance of evidence suggests that there is a discernible human influence on global climate.” Currently, more than 97 percent of publishing climate scientists agree on the existence and cause of climate change (as does nearly 60 percent of the general population of the United States).

So where did we get the idea that there’s still debate about climate change? A lot of it came from coordinated messaging campaigns by companies and politicians that opposed climate action. Many pushed the narrative that scientists still hadn’t made up their minds about climate change, even though that was misleading. Frank Luntz, a Republican consultant, explained the rationale in an infamous 2002 memo to conservative lawmakers: “Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly,” he wrote. Questioning consensus remains a common talking point today, and the 97 percent figure has become something of a lightning rod .

To bolster the falsehood of lingering scientific doubt, some people have pointed to things like the Global Warming Petition Project, which urged the United States government to reject the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, an early international climate agreement. The petition proclaimed that climate change wasn’t happening, and even if it were, it wouldn’t be bad for humanity. Since 1998, more than 30,000 people with science degrees have signed it. However, nearly 90 percent of them studied something other than Earth, atmospheric or environmental science, and the signatories included just 39 climatologists. Most were engineers, doctors, and others whose training had little to do with the physics of the climate system.

A few well-known researchers remain opposed to the scientific consensus. Some, like Willie Soon, a researcher affiliated with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, have ties to the fossil fuel industry . Others do not, but their assertions have not held up under the weight of evidence. At least one prominent skeptic, the physicist Richard Muller, changed his mind after reassessing historical temperature data as part of the Berkeley Earth project. His team’s findings essentially confirmed the results he had set out to investigate, and he came away firmly convinced that human activities were warming the planet. “Call me a converted skeptic,” he wrote in an Op-Ed for the Times in 2012.

Mr. Luntz, the Republican pollster, has also reversed his position on climate change and now advises politicians on how to motivate climate action.

A final note on uncertainty: Denialists often use it as evidence that climate science isn’t settled. However, in science, uncertainty doesn’t imply a lack of knowledge. Rather, it’s a measure of how well something is known. In the case of climate change, scientists have found a range of possible future changes in temperature, precipitation and other important variables — which will depend largely on how quickly we reduce emissions. But uncertainty does not undermine their confidence that climate change is real and that people are causing it.

Earth’s climate is inherently variable. Some years are hot and others are cold, some decades bring more hurricanes than others, some ancient droughts spanned the better part of centuries. Glacial cycles operate over many millenniums. So how can scientists look at data collected over a relatively short period of time and conclude that humans are warming the planet? The answer is that the instrumental temperature data that we have tells us a lot, but it’s not all we have to go on.

Historical records stretch back to the 1880s (and often before), when people began to regularly measure temperatures at weather stations and on ships as they traversed the world’s oceans. These data show a clear warming trend during the 20th century.

Global average temperature compared with the middle of the 20th century

+0.75°C

–0.25°

Some have questioned whether these records could be skewed, for instance, by the fact that a disproportionate number of weather stations are near cities, which tend to be hotter than surrounding areas as a result of the so-called urban heat island effect. However, researchers regularly correct for these potential biases when reconstructing global temperatures. In addition, warming is corroborated by independent data like satellite observations, which cover the whole planet, and other ways of measuring temperature changes.

Much has also been made of the small dips and pauses that punctuate the rising temperature trend of the last 150 years. But these are just the result of natural climate variability or other human activities that temporarily counteract greenhouse warming. For instance, in the mid-1900s, internal climate dynamics and light-blocking pollution from coal-fired power plants halted global warming for a few decades. (Eventually, rising greenhouse gases and pollution-control laws caused the planet to start heating up again.) Likewise, the so-called warming hiatus of the 2000s was partly a result of natural climate variability that allowed more heat to enter the ocean rather than warm the atmosphere. The years since have been the hottest on record .

Still, could the entire 20th century just be one big natural climate wiggle? To address that question, we can look at other kinds of data that give a longer perspective. Researchers have used geologic records like tree rings, ice cores, corals and sediments that preserve information about prehistoric climates to extend the climate record. The resulting picture of global temperature change is basically flat for centuries, then turns sharply upward over the last 150 years. It has been a target of climate denialists for decades. However, study after study has confirmed the results , which show that the planet hasn’t been this hot in at least 1,000 years, and probably longer.

Scientists have studied past climate changes to understand the factors that can cause the planet to warm or cool. The big ones are changes in solar energy, ocean circulation, volcanic activity and the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. And they have each played a role at times.

For example, 300 years ago, a combination of reduced solar output and increased volcanic activity cooled parts of the planet enough that Londoners regularly ice skated on the Thames . About 12,000 years ago, major changes in Atlantic circulation plunged the Northern Hemisphere into a frigid state. And 56 million years ago, a giant burst of greenhouse gases, from volcanic activity or vast deposits of methane (or both), abruptly warmed the planet by at least 9 degrees Fahrenheit, scrambling the climate, choking the oceans and triggering mass extinctions.

In trying to determine the cause of current climate changes, scientists have looked at all of these factors . The first three have varied a bit over the last few centuries and they have quite likely had modest effects on climate , particularly before 1950. But they cannot account for the planet’s rapidly rising temperature, especially in the second half of the 20th century, when solar output actually declined and volcanic eruptions exerted a cooling effect.

That warming is best explained by rising greenhouse gas concentrations . Greenhouse gases have a powerful effect on climate (see the next question for why). And since the Industrial Revolution, humans have been adding more of them to the atmosphere, primarily by extracting and burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas, which releases carbon dioxide.

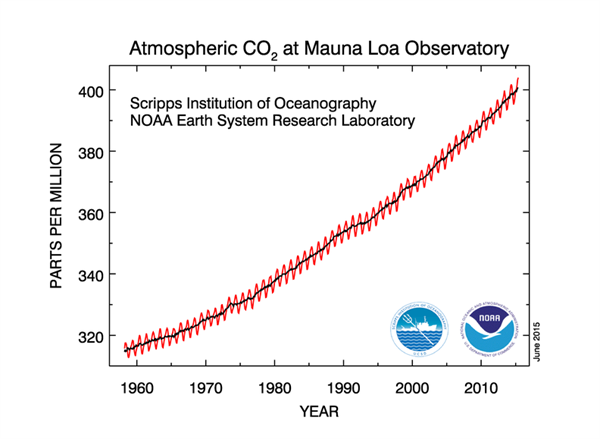

Bubbles of ancient air trapped in ice show that, before about 1750, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was roughly 280 parts per million. It began to rise slowly and crossed the 300 p.p.m. threshold around 1900. CO2 levels then accelerated as cars and electricity became big parts of modern life, recently topping 420 p.p.m . The concentration of methane, the second most important greenhouse gas, has more than doubled. We’re now emitting carbon much faster than it was released 56 million years ago .

30 billion metric tons

Carbon dioxide emitted worldwide 1850-2017

Rest of world

Other developed

European Union

Developed economies

Other countries

United States

E.U. and U.K.