Article Contents

- < Previous

Case Study: The Implementation of Total Quality Management at the Charleston VA Medical Center's Dental Service

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, Department of Defense, or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Barry L. Matthews, Case Study: The Implementation of Total Quality Management at the Charleston VA Medical Center's Dental Service, Military Medicine , Volume 157, Issue 1, January 1992, Pages 21–24, https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/157.1.21

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Total Quality Management (TQM) is an evolving management philosophy which has recently been introduced to the health care industry. TQM requires the use of a continuous process improvement methodology for delivered services. It was implemented at Charleston VAMC's Dental Service as a study to determine its effectiveness at the grassroots level. A modified Quality Circle was established within the clinical service under the guidance of Dr. Edward Deming's 14 principles. Top management support was not present. Many lessons were learned as process improvements were made. The overall success was limited due to the inability to address interdepartment process problems.

Email alerts

Citing articles via, looking for your next opportunity.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1930-613X

- Print ISSN 0026-4075

- Copyright © 2024 The Society of Federal Health Professionals

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

The role of place on healthcare quality improvement: A qualitative case study of a teaching hospital

Affiliation.

- 1 Queen's Management School, Queen's University Belfast, Riddel Hall, 185 Stranmillis Road, Belfast, BT9 5EE, Northern Ireland, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 29524869

- DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.03.003

This article examines how the built environment impacts, and is impacted by, healthcare staff day to day practice, care outcomes and the design of new quality and patient safety (Q&PS) projects. It also explores how perceptions of the built environment affect inter-professional dynamics. In doing so, it contributes to the overlooked interplay between the physical, social, and symbolic dimensions associated with a hospital's place. The study draws on 46 in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted at a large teaching hospital in Portugal formed by two buildings. Interview transcripts were analysed inductively using thematic analysis. The major contribution of this study is to advance the understanding of the interactions among the different dimensions of place on Q&PS improvement. For example, findings indicate that some of the characteristics of the physical infrastructure of the hospital have a negative impact on the quality of care provided and/or significantly limit the initiatives that can be implemented to improve it, including refurbishment works. However, decisions on refurbishment works were also influenced by the characteristics of the patient population, hospital budget, etc. Likewise, clinicians' emotional reactions to the limitations of the buildings depended on their expectations of the buildings and the symbolic projections they attributed to them. Nevertheless, differences between clinicians' expectations regarding the physical infrastructure and its actual features influenced clinicians' views on Q&PS initiatives designed by non-clinicians.

Keywords: Case study; Healthcare quality management; Hospital; Patient safety; Place.

Copyright © 2018. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Hospital Design and Construction*

- Hospitals, Teaching / statistics & numerical data*

- Organizational Case Studies

- Patient Safety

- Qualitative Research

- Quality Improvement / organization & administration*

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, integrated approach to healthcare quality management: a case study.

The TQM Magazine

ISSN : 0954-478X

Article publication date: 1 November 2006

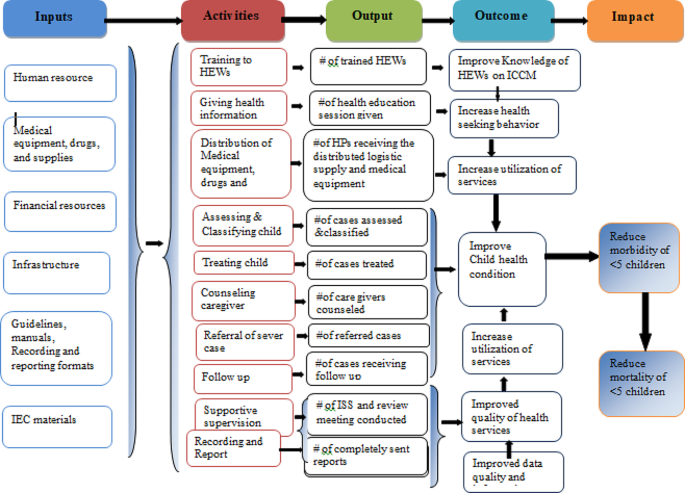

The purpose of the paper is to develop an integrated quality management model, which identifies problems, suggests solutions, develops a framework for implementation and helps evaluate performance of health care services dynamically.

Design/methodology/approach

This paper uses logical framework analysis (LFA), a matrix approach to project planning for managing quality. This has been applied to three acute healthcare services (Operating room utilization, Accident and emergency, and Intensive care) in order to demonstrate its effectiveness.

The paper finds that LFA is an effective method of quality management of hospital‐based healthcare services.

Research limitations/implications

This paper shows LFA application in three service processes in one hospital. However, ideally this is required to be tested in several hospitals and other services as well.

Practical implications

In the paper the proposed model can be practised in hospital‐based healthcare services for improving performance.

Originality/value

The paper shows that quality improvement in healthcare services is a complex and multi‐dimensional task. Although various quality management tools are routinely deployed for identifying quality issues in health care delivery and corrective measures are taken for superior performance, there is an absence of an integrated approach, which can identify and analyze issues, provide solutions to resolve those issues, develop a project management framework (planning, monitoring, and evaluating) to implement those solutions in order to improve process performance. This study introduces an integrated and uniform quality management tool. It integrates operations with organizational strategies.

- Service operations

- Health services

- Quality management

Dey, P.K. and Hariharan, S. (2006), "Integrated approach to healthcare quality management: a case study", The TQM Magazine , Vol. 18 No. 6, pp. 583-605. https://doi.org/10.1108/09544780610707093

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2006, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

An official website of the Department of Health & Human Services

- Search All AHRQ Sites

- Email Updates

1. Use quotes to search for an exact match of a phrase.

2. Put a minus sign just before words you don't want.

3. Enter any important keywords in any order to find entries where all these terms appear.

- The PSNet Collection

- All Content

- Perspectives

- Current Weekly Issue

- Past Weekly Issues

- Curated Libraries

- Clinical Areas

- Patient Safety 101

- The Fundamentals

- Training and Education

- Continuing Education

- WebM&M: Case Studies

- Training Catalog

- Submit a Case

- Improvement Resources

- Innovations

- Submit an Innovation

- About PSNet

- Editorial Team

- Technical Expert Panel

Leading quality and safety on the frontline - a case study of department leaders in nursing homes.

Magerøy M, Braut GS, Macrae C, et al. Leading quality and safety on the frontline - a case study of department leaders in nursing homes. J Healthc Leadersh. 2024;16:193-208. doi:10.2147/jhl.s454109.

Nursing homes face serious, ongoing patient safety challenges. This qualitative data analysis identified challenges and facilitators that are experienced by nursing home leaders in Norway as they manage the dual responsibilities of Health, Safety and Environment (HSE) and Quality and Patient Safety (QPS). The analysis identified four themes – temporal capacity, relational capacity, professional competence , and organizational structure – highlighting the importance of adequate resources , teamwork, and strong organizational safety culture .

Healthcare leaders' and elected politicians' approach to support-systems and requirements for complying with quality and safety regulation in nursing homes - a case study. September 13, 2023

Managing patient safety and staff safety in nursing homes: exploring how leaders of nursing homes negotiate their dual responsibilities- a case study. February 28, 2024

Investigating hospital supervision: a case study of regulatory inspectors' roles as potential co-creators of resilience. April 14, 2021

Resilience from a stakeholder perspective: the role of next of kin in cancer care. September 23, 2020

Positive deviance: a different approach to achieving patient safety. August 20, 2014

Determination of health-care teamwork training competencies: a Delphi study. December 2, 2009

Naming the "baby" or the "beast"? The importance of concepts and labels in healthcare safety investigation. April 5, 2023

Issues and complexities in safety culture assessment in healthcare. July 19, 2023

The patient died: what about involvement in the investigation process? June 24, 2020

Tools for establishing a sustainable safety culture within maternity services: a retrospective case study. April 26, 2023

Using the WHO International Classification of patient safety framework to identify incident characteristics and contributing factors for medical or surgical complication deaths October 2, 2019

Back to basics: checklists in aviation and healthcare. June 17, 2015

Results of a medication reconciliation survey from the 2006 Society of Hospital Medicine national meeting. January 14, 2009

Patient safety risks associated with telecare: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the literature. January 7, 2015

Designing and pilot testing of a leadership intervention to improve quality and safety in nursing homes and home care (the SAFE-LEAD intervention). August 14, 2019

Prospects for comparing European hospitals in terms of quality and safety: lessons from a comparative study in five countries. March 27, 2013

Linking transformational leadership, patient safety culture and work engagement in home care services. January 29, 2020

How does the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist fit with existing perioperative risk management strategies? An ethnographic study across surgical specialties. March 18, 2020

Exploring challenges in quality and safety work in nursing homes and home care - a case study as basis for theory development. April 29, 2020

Family perceptions of medication administration at school: errors, risk factors, and consequences. April 16, 2008

Remembering to learn: the overlooked role of remembrance in safety improvement. December 7, 2016

Delivering high reliability in maternity care: in situ simulation as a source of organisational resilience. July 10, 2019

Learning from failure: the need for independent safety investigation in healthcare. November 19, 2014

The problem with incident reporting. October 28, 2015

Investigating for improvement? Five strategies to ensure national patient safety investigations improve patient safety. June 5, 2019

Can we import improvements from industry to healthcare? May 1, 2019

Governing the safety of artificial intelligence in healthcare. May 8, 2019

The harm susceptibility model: a method to prioritise risks identified in patient safety reporting systems. June 9, 2010

Early warnings, weak signals and learning from healthcare disasters. April 9, 2014

Imitating incidents: how simulation can improve safety investigation and learning from adverse events. June 27, 2018

Measurement and monitoring of safety: impact and challenges of putting a conceptual framework into practice. April 11, 2018

Safety analysis over time: seven major changes to adverse event investigation. January 24, 2018

Learning from patient safety incidents: creating participative risk regulation in healthcare. February 27, 2008

Communication and information deficits in patients discharged to rehabilitation facilities: an evaluation of five acute care hospitals. October 28, 2009

Deficits in discharge documentation in patients transferred to rehabilitation facilities on anticoagulation: results of a systemwide evaluation. August 6, 2008

Transformational improvement in quality care and health systems: the next decade. November 25, 2020

"Time is of the essence": relationship between hospital staff perceptions of time, safety attitudes and staff wellbeing. December 8, 2021

Dimensions of safety culture: a systematic review of quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods for assessing safety culture in hospitals. September 1, 2021

Unsafe care in residential settings for older adults. A content analysis of accreditation reports. December 13, 2023

Improving patient safety governance and systems through learning from successes and failures: qualitative surveys and interviews with international experts. December 6, 2023

Predictors of response rates of safety culture questionnaires in healthcare: a systematic review and analysis. October 26, 2022

Comparing rates of adverse events detected in incident reporting and the Global Trigger Tool: a systematic review. August 16, 2023

COVID-19: patient safety and quality improvement skills to deploy during the surge. June 24, 2020

A qualitative content analysis of retained surgical items: learning from root cause analysis investigations. May 27, 2020

Disentangling quality and safety indicator data: a longitudinal, comparative study of hand hygiene compliance and accreditation outcomes in 96 Australian hospitals. October 8, 2014

Harnessing implementation science to improve care quality and patient safety: a systematic review of targeted literature. May 21, 2014

'Between the flags': implementing a rapid response system at scale. May 14, 2014

Health service accreditation as a predictor of clinical and organisational performance: a blinded, random, stratified study. March 24, 2010

Improving patient safety: the comparative views of patient-safety specialists, workforce staff and managers. January 30, 2005

Learning from disasters to improve patient safety: applying the generic disaster pathway to health system errors. February 9, 2011

Beyond patient safety Flatland. June 30, 2010

Cultural and associated enablers of, and barriers to, adverse incident reporting. June 23, 2010

Nurses' workarounds in acute healthcare settings: a scoping review. June 19, 2013

Investigating patient safety culture across a health system: multilevel modelling of differences associated with service types and staff demographics. July 25, 2012

Analysis of Australian newspaper coverage of medication errors. January 25, 2012

Health professional networks as a vector for improving healthcare quality and safety: a systematic review. January 11, 2012

Effects of two commercial electronic prescribing systems on prescribing error rates in hospital in-patients: a before and after study. February 15, 2012

'Broken hospital windows': debating the theory of spreading disorder and its application to healthcare organizations. May 9, 2018

Changing how we think about healthcare improvement. June 13, 2018

Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review. January 17, 2018

The application of the Global Trigger Tool: a systematic review. October 26, 2016

False dawns and new horizons in patient safety research and practice. December 20, 2017

Implementation of a patient safety incident management system as viewed by doctors, nurses and allied health professionals. May 6, 2009

A root cause analysis of clinical error: confronting the disjunction between formal rules and situated clinical activity. May 31, 2006

Attitudes toward the large-scale implementation of an incident reporting system. April 9, 2008

Experiences of health professionals who conducted root cause analyses after undergoing a safety improvement programme. December 20, 2006

Turning the medical gaze in upon itself: root cause analysis and the investigation of clinical error. October 26, 2005

The effect of physicians' long-term use of CPOE on their test management work practices. September 27, 2006

Incidence, origins and avoidable harm of missed opportunities in diagnosis: longitudinal patient record review in 21 English general practices. June 30, 2021

Educational levels of hospital nurses and surgical patient mortality. April 3, 2005

A systematic narrative review of coroners’ Prevention of Future Deaths reports (PFDs): a tool for patient safety in hospitals. November 1, 2023

Quality gaps identified through mortality review. February 1, 2017

Assessing the impact of teaching patient safety principles to medical students during surgical clerkships. July 20, 2011

Medical errors: mandatory reporting, voluntary reporting, or both? August 10, 2005

Journal Article

Implementation of a medication reconciliation risk stratification tool integrated within an electronic health record: a case series of three academic medical centers.

Effects of a refined evidence-based toolkit and mentored implementation on medication reconciliation at 18 hospitals: results of the MARQUIS2 study. May 19, 2021

What works in medication reconciliation: an on-treatment and site analysis of the MARQUIS2 study. April 12, 2023

Handoff practices in emergency medicine: are we making progress? March 23, 2016

Preventability and causes of readmissions in a national cohort of general medicine patients. May 4, 2016

Project BOOST implementation: lessons learned. September 10, 2014

Making inpatient medication reconciliation patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. October 27, 2010

Process changes to increase compliance with the Universal Protocol for bedside procedures. June 1, 2011

Single-parameter early warning criteria to predict life-threatening adverse events. June 23, 2010

Impact of an automated email notification system for results of tests pending at discharge: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. November 27, 2013

Effect of a pharmacist intervention on clinically important medication errors after hospital discharge: a randomized trial. July 18, 2012

Effects of an online personal health record on medication accuracy and safety: a cluster-randomized trial. May 23, 2012

Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. August 21, 2013

A toolkit to disseminate best practices in inpatient medication reconciliation: Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS). July 31, 2013

Design and implementation of an automated email notification system for results of tests pending at discharge. February 29, 2012

The impact of automated notification on follow-up of actionable tests pending at discharge: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. April 11, 2018

Curriculum development and implementation of a national interprofessional fellowship in patient safety. September 5, 2018

Readiness of US general surgery residents for independent practice. October 4, 2017

The HOSPITAL score predicts potentially preventable 30-day readmissions in conditions targeted by the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. June 14, 2017

Medication safety in a psychiatric hospital. March 21, 2007

A controlled trial of a rapid response system in an academic medical center. June 25, 2008

Adverse events related to accidental unintentional ingestions from cough and cold medications in children. August 26, 2020

Evaluation of older persons' medications: a critical incident technique study exploring healthcare professionals' experiences and actions. June 23, 2021

Nurses' experience with presenteeism and the potential consequences on patient safety: a qualitative study among nurses at out-of-hours emergency primary care facilities. January 10, 2024

Medication dosage calculation among nursing students: does digital technology make a difference? A literature review. September 14, 2022

Clinical efficacy of combined surgical patient safety system and the World Health Organization's checklists in surgery: a nonrandomized clinical trial. June 3, 2020

Patient Safety Primers

Long-term Care and Patient Safety

Annual Perspective

Special Section: IEA Health Care 2021. February 28, 2024

Patient safety in nursing homes from an ecological perspective: an integrated review. January 17, 2024

National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports. January 9, 2024

Nurses' perspectives on medication errors and prevention strategies in residential aged care facilities through a national survey. December 20, 2023

The relationship between nursing home staffing and resident safety outcomes: a systematic review of reviews. December 6, 2023

Innovative approaches to analysing aged care falls incident data: International Classification for Patient Safety and correspondence analysis. November 8, 2023

Early identification and evaluation of severe pressure injuries. October 18, 2023

Exploring medication safety structures and processes in nursing homes: a cross-sectional study. August 30, 2023

Reimagining Healthcare Teams: Leveraging the Patient-Clinician-AI Triad To Improve Diagnostic Safety. August 16, 2023

Long-term care healthcare-associated infections in 2022: an analysis of 20,216 reports. May 24, 2023

WebM&M Cases

Efforts to improve the safety culture of the elderly in nursing homes: a qualitative study. April 19, 2023

Factors differentiating nursing homes with strong resident safety climate: a qualitative study of leadership and staff perspectives. February 15, 2023

New AHRQ SOPS Workplace Safety Supplemental Item Set for Nursing Homes. February 15, 2023

Surveys on Patient Safety Culture Nursing Home Survey: 2023 User Database Report. February 8, 2023

Nursing home patient safety culture perceptions among licensed practical nurses. February 1, 2023

Interventions to increase patient safety in long-term care facilities-umbrella review. January 25, 2023

Patient safety measurement tools used in nursing homes: a systematic literature review. December 7, 2022

Patient safety culture in assisted living: staff perceptions and association with state regulations. November 30, 2022

Reinforcing the Value and Roles of Nurses in Diagnostic Safety: Pragmatic Recommendations for Nurse Leaders and Educators. October 5, 2022

Nursing Home Survey on Patient Safety Culture. August 31, 2022

Accuracy of pressure ulcer events in US nursing home ratings. August 24, 2022

Using health information technology in residential aged care homes: an integrative review to identify service and quality outcomes. August 17, 2022

Communication disparities between nursing home team members. July 20, 2022

Long-term care healthcare-associated infections in 2021: an analysis of 17,971 reports. July 13, 2022

Supplemental Item Set for Nursing Home SOPS: Call for Pilot Participants. July 6, 2022

Connect With Us

Sign up for Email Updates

To sign up for updates or to access your subscriber preferences, please enter your email address below.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 Telephone: (301) 427-1364

- Accessibility

- Disclaimers

- Electronic Policies

- HHS Digital Strategy

- HHS Nondiscrimination Notice

- Inspector General

- Plain Writing Act

- Privacy Policy

- Viewers & Players

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- The White House

- Don't have an account? Sign up to PSNet

Submit Your Innovations

Please select your preferred way to submit an innovation.

Continue as a Guest

Track and save your innovation

in My Innovations

Edit your innovation as a draft

Continue Logged In

Please select your preferred way to submit an innovation. Note that even if you have an account, you can still choose to submit an innovation as a guest.

Continue logged in

New users to the psnet site.

Access to quizzes and start earning

CME, CEU, or Trainee Certification.

Get email alerts when new content

matching your topics of interest

in My Innovations.

Sign up for the newsletter

Digital editions.

Total quality management: three case studies from around the world

With organisations to run and big orders to fill, it’s easy to see how some ceos inadvertently sacrifice quality for quantity. by integrating a system of total quality management it’s possible to have both.

Top 5 ways to manage the board during turbulent times Top 5 ways to create a family-friendly work culture Top 5 tips for a successful joint venture Top 5 ways managers can support ethnic minority workers Top 5 ways to encourage gender diversity in the workplace Top 5 ways CEOs can create an ethical company culture Top 5 tips for going into business with your spouse Top 5 ways to promote a healthy workforce Top 5 ways to survive a recession Top 5 tips for avoiding the ‘conference vortex’ Top 5 ways to maximise new parents’ work-life balance with technology Top 5 ways to build psychological safety in the workplace Top 5 ways to prepare your workforce for the AI revolution Top 5 ways to tackle innovation stress in the workplace Top 5 tips for recruiting Millennials

There are few boardrooms in the world whose inhabitants don’t salivate at the thought of engaging in a little aggressive expansion. After all, there’s little room in a contemporary, fast-paced business environment for any firm whose leaders don’t subscribe to ambitions of bigger factories, healthier accounts and stronger turnarounds. Yet too often such tales of excess go hand-in-hand with complaints of a severe drop in quality.

Food and entertainment markets are riddled with cautionary tales, but service sectors such as health and education aren’t immune to the disappointing by-products of unsustainable growth either. As always, the first steps in avoiding a catastrophic forsaking of quality begins with good management.

There are plenty of methods and models geared at managing the quality of a particular company’s goods or services. Yet very few of those models take into consideration the widely held belief that any company is only as strong as its weakest link. With that in mind, management consultant William Deming developed an entirely new set of methods with which to address quality.

Deming, whose managerial work revolutionised the titanic Japanese manufacturing industry, perceived quality management to be more of a philosophy than anything else. Top-to-bottom improvement, he reckoned, required uninterrupted participation of all key employees and stakeholders. Thus, the total quality management (TQM) approach was born.

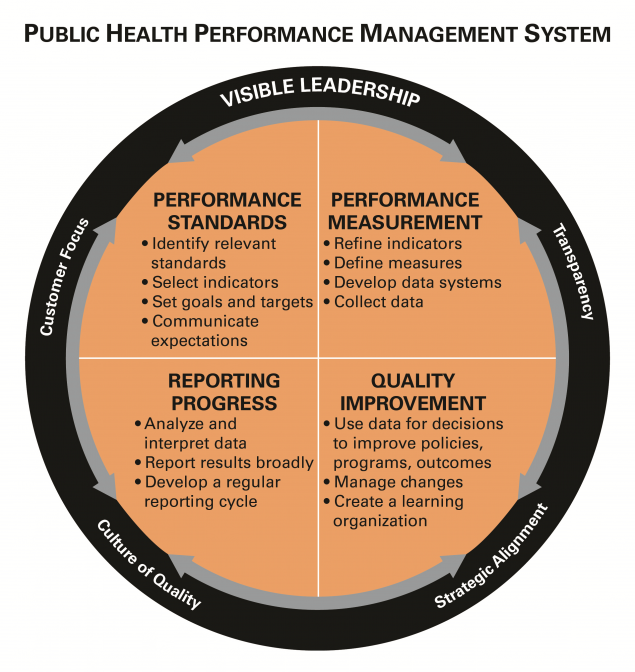

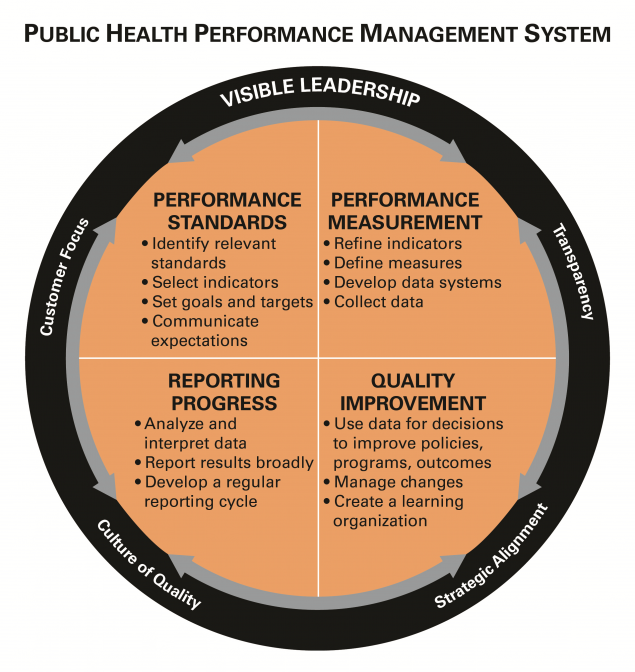

All in Similar to the Six Sigma improvement process, TQM ensures long-term success by enforcing all-encompassing internal guidelines and process standards to reduce errors. By way of serious, in-depth auditing – as well as some well-orchestrated soul-searching – TQM ensures firms meet stakeholder needs and expectations efficiently and effectively, without forsaking ethical values.

By opting to reframe the way employees think about the company’s goals and processes, TQM allows CEOs to make sure certain things are done right from day one. According to Teresa Whitacre, of international consulting firm ASQ , proper quality management also boosts a company’s profitability.

“Total quality management allows the company to look at their management system as a whole entity — not just an output of the quality department,” she says. “Total quality means the organisation looks at all inputs, human resources, engineering, production, service, distribution, sales, finance, all functions, and their impact on the quality of all products or services of the organisation. TQM can improve a company’s processes and bottom line.”

Embracing the entire process sees companies strive to improve in several core areas, including: customer focus, total employee involvement, process-centred thinking, systematic approaches, good communication and leadership and integrated systems. Yet Whitacre is quick to point out that companies stand to gain very little from TQM unless they’re willing to go all-in.

“Companies need to consider the inputs of each department and determine which inputs relate to its governance system. Then, the company needs to look at the same inputs and determine if those inputs are yielding the desired results,” she says. “For example, ISO 9001 requires management reviews occur at least annually. Aside from minimum standard requirements, the company is free to review what they feel is best for them. While implementing TQM, they can add to their management review the most critical metrics for their business, such as customer complaints, returns, cost of products, and more.”

The customer knows best: AtlantiCare TQM isn’t an easy management strategy to introduce into a business; in fact, many attempts tend to fall flat. More often than not, it’s because firms maintain natural barriers to full involvement. Middle managers, for example, tend to complain their authority is being challenged when boots on the ground are encouraged to speak up in the early stages of TQM. Yet in a culture of constant quality enhancement, the views of any given workforce are invaluable.

AtlantiCare in numbers

5,000 Employees

$280m Profits before quality improvement strategy was implemented

$650m Profits after quality improvement strategy

One firm that’s proven the merit of TQM is New Jersey-based healthcare provider AtlantiCare . Managing 5,000 employees at 25 locations, AtlantiCare is a serious business that’s boasted a respectable turnaround for nearly two decades. Yet in order to increase that margin further still, managers wanted to implement improvements across the board. Because patient satisfaction is the single-most important aspect of the healthcare industry, engaging in a renewed campaign of TQM proved a natural fit. The firm chose to adopt a ‘plan-do-check-act’ cycle, revealing gaps in staff communication – which subsequently meant longer patient waiting times and more complaints. To tackle this, managers explored a sideways method of internal communications. Instead of information trickling down from top-to-bottom, all of the company’s employees were given freedom to provide vital feedback at each and every level.

AtlantiCare decided to ensure all new employees understood this quality culture from the onset. At orientation, staff now receive a crash course in the company’s performance excellence framework – a management system that organises the firm’s processes into five key areas: quality, customer service, people and workplace, growth and financial performance. As employees rise through the ranks, this emphasis on improvement follows, so managers can operate within the company’s tight-loose-tight process management style.

After creating benchmark goals for employees to achieve at all levels – including better engagement at the point of delivery, increasing clinical communication and identifying and prioritising service opportunities – AtlantiCare was able to thrive. The number of repeat customers at the firm tripled, and its market share hit a six-year high. Profits unsurprisingly followed. The firm’s revenues shot up from $280m to $650m after implementing the quality improvement strategies, and the number of patients being serviced dwarfed state numbers.

Hitting the right notes: Santa Cruz Guitar Co For companies further removed from the long-term satisfaction of customers, it’s easier to let quality control slide. Yet there are plenty of ways in which growing manufacturers can pursue both quality and sales volumes simultaneously. Artisan instrument makers the Santa Cruz Guitar Co (SCGC) prove a salient example. Although the California-based company is still a small-scale manufacturing operation, SCGC has grown in recent years from a basement operation to a serious business.

SCGC in numbers

14 Craftsmen employed by SCGC

800 Custom guitars produced each year

Owner Dan Roberts now employs 14 expert craftsmen, who create over 800 custom guitars each year. In order to ensure the continued quality of his instruments, Roberts has created an environment that improves with each sale. To keep things efficient (as TQM must), the shop floor is divided into six workstations in which guitars are partially assembled and then moved to the next station. Each bench is manned by a senior craftsman, and no guitar leaves that builder’s station until he is 100 percent happy with its quality. This product quality is akin to a traditional assembly line; however, unlike a traditional, top-to-bottom factory, Roberts is intimately involved in all phases of instrument construction.

Utilising this doting method of quality management, it’s difficult to see how customers wouldn’t be satisfied with the artists’ work. Yet even if there were issues, Roberts and other senior management also spend much of their days personally answering web queries about the instruments. According to the managers, customers tend to be pleasantly surprised to find the company’s senior leaders are the ones answering their technical questions and concerns. While Roberts has no intentions of taking his manufacturing company to industrial heights, the quality of his instruments and high levels of customer satisfaction speak for themselves; the company currently boasts one lengthy backlog of orders.

A quality education: Ramaiah Institute of Management Studies Although it may appear easier to find success with TQM at a boutique-sized endeavour, the philosophy’s principles hold true in virtually every sector. Educational institutions, for example, have utilised quality management in much the same way – albeit to tackle decidedly different problems.

The global financial crisis hit higher education harder than many might have expected, and nowhere have the odds stacked higher than in India. The nation plays home to one of the world’s fastest-growing markets for business education. Yet over recent years, the relevance of business education in India has come into question. A report by one recruiter recently asserted just one in four Indian MBAs were adequately prepared for the business world.

RIMS in numbers

9% Increase in test scores post total quality management strategy

22% Increase in number of recruiters hiring from the school

20,000 Increase in the salary offered to graduates

50,000 Rise in placement revenue

At the Ramaiah Institute of Management Studies (RIMS) in Bangalore, recruiters and accreditation bodies specifically called into question the quality of students’ educations. Although the relatively small school has always struggled to compete with India’s renowned Xavier Labour Research Institute, the faculty finally began to notice clear hindrances in the success of graduates. The RIMS board decided it was time for a serious reassessment of quality management.

The school nominated Chief Academic Advisor Dr Krishnamurthy to head a volunteer team that would audit, analyse and implement process changes that would improve quality throughout (all in a particularly academic fashion). The team was tasked with looking at three key dimensions: assurance of learning, research and productivity, and quality of placements. Each member underwent extensive training to learn about action plans, quality auditing skills and continuous improvement tools – such as the ‘plan-do-study-act’ cycle.

Once faculty members were trained, the team’s first task was to identify the school’s key stakeholders, processes and their importance at the institute. Unsurprisingly, the most vital processes were identified as student intake, research, knowledge dissemination, outcomes evaluation and recruiter acceptance. From there, Krishnamurthy’s team used a fishbone diagram to help identify potential root causes of the issues plaguing these vital processes. To illustrate just how bad things were at the school, the team selected control groups and administered domain-based knowledge tests.

The deficits were disappointing. A RIMS students’ knowledge base was rated at just 36 percent, while students at Harvard rated 95 percent. Likewise, students’ critical thinking abilities rated nine percent, versus 93 percent at MIT. Worse yet, the mean salaries of graduating students averaged $36,000, versus $150,000 for students from Kellogg. Krishnamurthy’s team had their work cut out.

To tackle these issues, Krishnamurthy created an employability team, developed strategic architecture and designed pilot studies to improve the school’s curriculum and make it more competitive. In order to do so, he needed absolutely every employee and student on board – and there was some resistance at the onset. Yet the educator asserted it didn’t actually take long to convince the school’s stakeholders the changes were extremely beneficial.

“Once students started seeing the results, buy-in became complete and unconditional,” he says. Acceptance was also achieved by maintaining clearer levels of communication with stakeholders. The school actually started to provide shareholders with detailed plans and projections. Then, it proceeded with a variety of new methods, such as incorporating case studies into the curriculum, which increased general test scores by almost 10 percent. Administrators also introduced a mandate saying students must be certified in English by the British Council – increasing scores from 42 percent to 51 percent.

By improving those test scores, the perceived quality of RIMS skyrocketed. The number of top 100 businesses recruiting from the school shot up by 22 percent, while the average salary offers graduates were receiving increased by $20,000. Placement revenue rose by an impressive $50,000, and RIMS has since skyrocketed up domestic and international education tables.

No matter the business, total quality management can and will work. Yet this philosophical take on quality control will only impact firms that are in it for the long haul. Every employee must be in tune with the company’s ideologies and desires to improve, and customer satisfaction must reign supreme.

Contributors

- Industry Outlook

- Kindle Store

- Kindle eBooks

- Medical eBooks

Promotions apply when you purchase

These promotions will be applied to this item:

Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions.

- Highlight, take notes, and search in the book

- In this edition, page numbers are just like the physical edition

- Create digital flashcards instantly

Rent $49.00

Today through selected date:

Rental price is determined by end date.

Buy for others

Buying and sending ebooks to others.

- Select quantity

- Buy and send eBooks

- Recipients can read on any device

These ebooks can only be redeemed by recipients in the US. Redemption links and eBooks cannot be resold.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Healthcare Quality Management: A Case Study Approach 1st Edition, Kindle Edition

Healthcare Quality Management: A Case Study Approach is the first comprehensive case-based text combining essential quality management knowledge with real-world scenarios. With in-depth healthcare quality management case studies, tools, activities, and discussion questions, the text helps build the competencies needed to succeed in quality management.

Written in an easy-to-read style, Part One of the textbook introduces students to the fundamentals of quality management, including history, culture, and different quality management philosophies, such as Lean and Six Sigma. Part One additionally explains the A3 problem-solving template used to follow the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) or Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, and Control (DMAIC) cycles, that guides your completion of the problem-solving exercises found in Part Two. The bulk of the textbook includes realistic and engaging case studies featuring common quality management problems encountered in a variety of healthcare settings. The case studies feature engaging scenarios, descriptions, opinions, charts, and data, covering such contemporary topics as provider burnout, artificial intelligence, the opioid overdose epidemic, among many more.

Serving as a powerful replacement to more theory-based quality management textbooks, Healthcare Quality Management provides context to challenging situations encountered by any healthcare manager, including the health administrator, nurse, physician, social worker, or allied health professional.

- 25 Realistic Case Studies–Explore challenging Process Improvement, Patient Experience, Patient Safety, and Performance Improvement quality management scenarios set in various healthcare settings

- Diverse Author Team–Combines the expertise and knowledge of a health management educator, a Chief Nursing Officer at a large regional hospital, and a health system-based Certified Lean Expert

- Podcasts–Listen to quality management experts share stories and secrets on how to succeed, work in teams, and apply tools to solve problems

- Quality Management Tools–Grow your quality management skill set with 25 separate quality management tools and approaches tied to the real-world case studies

- Competency-Based Education Support–Match case studies to professional competencies, such as analytical skills, community collaboration, and interpersonal relations, using case-to-competency crosswalks for health administration, nursing, medicine, and the interprofessional team

- Comprehensive Instructor’s Packet–Includes PPTs, extensive Excel data files, an Instructor’s Manual with completed A3 problem-solving solutions for each Case Application Exercise, and more!

- Student ancillaries–Includes data files and A3 template

- ISBN-13 978-0826145130

- Edition 1st

- Sticky notes On Kindle Scribe

- Publisher Springer Publishing Company

- Publication date February 28, 2020

- Language English

- File size 36513 KB

- See all details

- Kindle (5th Generation)

- Kindle Keyboard

- Kindle (2nd Generation)

- Kindle (1st Generation)

- Kindle Paperwhite

- Kindle Paperwhite (5th Generation)

- Kindle Touch

- Kindle Voyage

- Kindle Oasis

- Kindle Scribe (1st Generation)

- Kindle Fire HDX 8.9''

- Kindle Fire HDX

- Kindle Fire HD (3rd Generation)

- Fire HDX 8.9 Tablet

- Fire HD 7 Tablet

- Fire HD 6 Tablet

- Kindle Fire HD 8.9"

- Kindle Fire HD(1st Generation)

- Kindle Fire(2nd Generation)

- Kindle Fire(1st Generation)

- Kindle for Windows 8

- Kindle for Windows Phone

- Kindle for BlackBerry

- Kindle for Android Phones

- Kindle for Android Tablets

- Kindle for iPhone

- Kindle for iPod Touch

- Kindle for iPad

- Kindle for Mac

- Kindle for PC

- Kindle Cloud Reader

Customers who bought this item also bought

Editorial Reviews

About the author.

Zachary Pruitt, PhD, MHA, CPH, is assistant professor and director of community practice at the University of South Florida College of Public Health.

Candace S. Smith, PhD, RN, NEA-BC, is chief nursing officer at Manatee Memorial Hospital.

Eddie Pérez-Ruberté, MS, is senior Lean project manager at BayCare Health Systems who leads the deployment of the Lean management system and culture. Eddie is a certified Lean expert and a certified Six Sigma Black Belt from the American Society for Quality. He also helps organizations implement Lean programs through his consulting company, Areito Group. Eddie is an instructor for the Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers where he teaches Lean and Six Sigma and certifies students in these methodologies at multiple universities and healthcare organizations across the United States.

Product details

- ASIN : B07YP7XC7V

- Publisher : Springer Publishing Company; 1st edition (February 28, 2020)

- Publication date : February 28, 2020

- Language : English

- File size : 36513 KB

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Not Enabled

- Word Wise : Not Enabled

- Sticky notes : On Kindle Scribe

- Print length : 404 pages

- #43 in Health Care Administration

- #106 in Health Care Delivery (Kindle Store)

- #132 in Public Health (Kindle Store)

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Report an issue

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2024

Nurse perceptions of practice environment, quality of care and patient safety across four hospital levels within the public health sector of South Africa

- Immaculate Sabelile Tenza 1 ,

- Alwiena J. Blignaut 1 ,

- Suria M. Ellis 2 &

- Siedine K. Coetzee 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 324 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

73 Accesses

Metrics details

Improving the practice environment, quality of care and patient safety are global health priorities. In South Africa, quality of care and patient safety are among the top goals of the National Department of Health; nevertheless, empirical data regarding the condition of the nursing practice environment, quality of care and patient safety in public hospitals is lacking.

This study examined nurses’ perceptions of the practice environment, quality of care and patient safety across four hospital levels (central, tertiary, provincial and district) within the public health sector of South Africa.

This was a cross-sectional survey design. We used multi-phase sampling to recruit all categories of nursing staff from central ( n = 408), tertiary ( n = 254), provincial ( n = 401) and district ( n = 244 [large n = 81; medium n = 83 and small n = 80]) public hospitals in all nine provinces of South Africa. After ethical approval, a self-reported questionnaire with subscales on the practice environment, quality of care and patient safety was administered. Data was collected from April 2021 to June 2022, with a response rate of 43.1%. ANOVA type Hierarchical Linear Modelling (HLM) was used to present the differences in nurses’ perceptions across four hospital levels.

Nurses rated the overall practice environment as poor (M = 2.46; SD = 0.65), especially with regard to the subscales of nurse participation in hospital affairs (M = 2.22; SD = 0.76), staffing and resource adequacy (M = 2.23; SD = 0.80), and nurse leadership, management, and support of nurses (M = 2.39; SD = 0.81). One-fifth (19.59%; n = 248) of nurses rated the overall grade of patient safety in their units as poor or failing, and more than one third (38.45%; n = 486) reported that the quality of care delivered to patient was fair or poor. Statistical and practical significant results indicated that central hospitals most often presented more positive perceptions of the practice environment, quality of care and patient safety, while small district hospitals often presented the most negative. The practice environment was most highly correlated with quality of care and patient safety outcomes.

There is a need to strengthen compliance with existing policies that enhance quality of care and patient safety. This includes the need to create positive practice environments in all public hospitals, but with an increased focus on smaller hospital settings.

Peer Review reports

Improving the nurse practice environment, quality of healthcare and patient safety has become a global priority [ 1 ]. This is because countries worldwide are striving to provide universal health coverage (UHC) to their citizens, and quality and safe care has been prioritised in the agenda to achieve UHC [ 2 , 3 ]. Recently there has been an increase in scholarly attention on the relationship between the nurse practice environment, quality of healthcare and patient safety, with global consensus that a positive nurse practice environment contributes positively to these [ 4 ].

The nurse practice environment is defined as the organisational characteristics of a work context that facilitate or constrain professional nursing practice [ 5 ]. Quality of care is the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of the desired health outcomes [ 6 ], and patient safety is a dimension of quality of care and is defined as the avoidance of unintended or unexpected harm to people during the provision of healthcare [ 1 ].

Studies on the nurse practice environment have focused on nurse participation in organisational affairs, staffing and resource adequacy, and nurse leadership, management, and support of nurses, nurse-physician collegial relations, and foundations of quality of care [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. A recent meta-analysis [ 10 ] found consistent and significant associations between the practice environment and quality of care and patient safety, based on data from 1,368,420 patients in 22 countries (including South Africa), 141 nursing units, 165,024 nurses, and 2677 hospitals. Ten years ago, a South African article—the only one from Africa included in this meta-analysis—showed the following trends: 52.3% of nurses assessed their practice environment as either poor or fair, 20.7% rated the quality of care as either poor or fair, and 5.5% rated patient safety as inadequate or failing [ 11 ]. In all cases, the public sector had worse outcomes than the private sector; and the study concluded that the nurse practice environment was significantly associated with better nurse and patient outcomes [ 11 ]. No national study has since followed this, with most studies focusing on small-scale or single-site qualitative and quantitative descriptive studies. Furthermore the variables of interest were explored separately from each other, such as the influence of the nurse practice environment on nurse outcomes [ 12 , 13 ], professional nurses’ understanding of quality nursing care [ 14 ], with a primary focus on patient safety culture [ 13 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Quality of care and patient safety studies in South Africa reported negative experiences of health providers, but these were not linked with the practice environment, even with ample evidence of its influence. One significant issue is the existence of policy documents that govern quality of care and patient safety in the nation. These include the following: the Patient Rights Charter, the Batho Pele principles, the National Core Standards framework [ 18 ], the National Guideline for Patient Safety Incident Reporting [ 19 ], and the Ideal Facility Framework [ 20 ]. Despite the aforementioned governmental obligations, achieving quality in healthcare continues to be a struggle [ 21 ]. This has been evidenced by the reports of litigations experienced by public health hospitals [ 22 ]. A major concern of the National Department of Health is the sudden increase in expenditure related to medico-legal claims. In the 2020/2021 financial year, more than ZAR6.5 billion (US $343,496.02) was awarded in medicolegal claims in the public sector [ 23 ].

Nurses as frontline, street-level bureaucrats in the implementation of the policies related to quality of care and patient safety in healthcare have critical experience of the nurse practice environment, quality of care and patient safety, and their views could contribute to future improvements [ 5 ]. Given existing evidence that the nurse practice environment influences quality of care and patient safety, it is important to understand the current situation. While there are existing policies directing quality of care and patient safety, it is not known how having these policies in place shapes the nurse practice environment, perceived quality of care and patient safety. This article expands on the findings of a previous national study [ 11 ], which demonstrated that the public sector had a more negative nurse practice environment, quality of care and patient safety. To add to the body of knowledge, this study examines the public sector and four hospital levels: central, tertiary, provincial, and district (small, medium, and large) hospitals. Hence this national study sought to examine nurses' perceptions of the practice environment, quality of care and patient safety across four hospital levels within the public health sector of South Africa.

Theoretical framework

This study is based on the theoretical framework of Tvedt et al. [ 24 ], which is a system perspective based on the model of Donabedian and modified by Battles (2006) to show how hospital structures and practice environment features improve quality of care and patient safety [ 24 ]. These outcomes are specifically identified as quality of care, patient safety (work-related outcome measures), and low-frequency adverse events and self-care ability (patient-related outcome measures).

Study context

This study was conducted in all nine provinces of South Africa, namely, Northern Cape, Western Cape, Eastern Cape, Free State, North West, Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and KwaZulu-Natal. South Africa has a two-tier healthcare system, with a public and a private sector [ 18 , 25 ]. The public sector is state-funded and caters to the majority – 71% – of the population [ 19 , 25 ]. The private sector is largely funded through individual contributions to medical aid schemes or health insurance, and serves a minority of the population [ 20 , 25 ]. This study focused on the public sector hospitals as they cater for the majority of the population. There are five categories of hospitals in the public sector, including district, regional, tertiary, central, and specialised hospitals, which are categorised according to the nature and extent of services provided and size [ 26 ]. The first point of entry to the South African health system is through primary healthcare (PHC) facilities, often referred to as clinics. Patients are referred from PHC facilities to district hospitals, regional, tertiary and central hospitals or specialised hospitals [ 26 ]. District hospitals are categorised into small, medium, and large district hospitals. Small district hospitals have between 50 and 150 beds; medium district hospitals have between 150 and 300 beds; and large district hospitals have between 300 and 600 beds [ 26 ]. These hospitals serve a defined population within a health district and support PHC facilities, providing services that include in-patient, ambulatory health services as well as emergency health services [ 26 ]. A regional hospital has between 200 and 800 beds and receives referrals from several district hospitals. Regional hospitals provide health services on a 24-h basis to a defined regional population, limited to provincial boundaries [ 26 ]. A tertiary hospital has between 400 and 800 beds and receives referrals from regional hospitals not limited to provincial boundaries, and also provides specialist level services [ 26 ]. A central hospital has a maximum of 1200 beds, receives patients referred from more than one province, and provides tertiary hospital services; they may also provide national referral services, including conducting research. A central hospital is attached to a medical school as the main teaching platform [ 26 ].

Study design

This study had a cross-sectional descriptive design. The STROBE checklist of items that should be included in reports of cross-sectional studies was used to guide the study and the reporting thereof.

Population and sampling

Multi-phase sampling was applied in the public sector. Purposive sampling was applied to the selection of hospitals in the public sector. A total of 27 hospitals were included by selecting the largest central or tertiary hospital in every province, and the provincial and district hospital in closest proximity to the selected central or tertiary hospital. The district hospitals were further stratified into large ( n = 2), medium ( n = 3), and small ( n = 4) hospitals. Specialist hospitals were excluded. All in-patient medical and surgical units were included. Total population sampling was applied to all categories of nursing staff (registered nurses, community service nurses, enrolled nurses [2-year diploma], and enrolled nursing auxiliaries [1-year certificate]), including temporary staff, in these selected units. Nurses had to have worked in the respective unit for at least three months, and student nurses were excluded. The total sample of participants was as follows: central n = 408; tertiary, n = 254; provincial, n = 401; and district, n = 244 [large n = 81; medium n = 83 and small n = 80]). Data were collected from April 2021 to June 2022. A sample size calculation was performed in g-power using the F-tests as the Test Family and the ANOVA: Fixed effects, special, main effects and interactions as the Statistical test in order to take the structure of the data into account. The parameters were specified as follow: Effect size f as and large (0.4) and medium (0.25), α err prob as 0.05, Power (1-β err prob) as 0.95, Numerator df as 10, Number of groups 6. The total sample sizes calculated were 162 and 400, which is well below the realised sample size of 1307. Total population sampling was used and not a random sample, thus no generalisations are made beyond the study population of nurses from these hospitals.

Instruments

In accordance with the theoretical framework of Tvedt et al., the variables measured included practice environment, quality of care, self-care ability, patient safety, and adverse events [ 24 ] . The practice environment was measured using the Practice Environment Scale of the Nurse Work Index Revised (PES-NWI-R). It consists of 32 questions and is divided into five subscales measuring nurse participation in hospital affairs; nursing foundations for quality of care; nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses; staffing and resource adequacy; and collegial nurse-physician relations. The questions are measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 4, where 1 represents strongly disagree and 4 strongly agree. A mean score of 2.5 or more is indicative of a positive practice environment. This tool was found to be valid and reliable in many countries, including South Africa [ 27 ].

Quality of care was measured using the following question: In general, how would you describe the quality of nursing care delivered to patients on your unit/ward? The question was measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 represented excellent and 5 poor. Self-care ability was measured using one question (How confident are you that your patients and their caregivers can manage their care after discharge?), measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 4, where 1 represented very confident and 5 not at all confident.

Patient safety was measured using the following question: Please give your current practice setting an overall grade on patient safety. This was measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 represented excellent and 5 represented failing. The other eight items came from the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC) [ 28 ]. They were answered on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where one represented strongly agree and five strongly disagree.

Finally, adverse events were measured by five questions on a five-point scale, where 1 represented never and 5 represented daily. These questions have been employed in multi-country research in South Africa [ 29 ], Europe [ 30 ], the United States of America [ 31 ], and Asia [ 32 ]. The specific outcomes have also been used in a meta-analysis [ 33 ]. The authors tried to control for response bias and subjectivity by asking neutrally worded questions, using anonymous surveys, ensuring that answer options were not leading, and that the order of the answers was randomised. i.e. the range for the practice environment was 1 = Strongly disagree.

4 = Strongly agree (ascending order), while quality of care and patient safety ranged from 1 = Excellent; 4 = Poor (descending order).

Data collection

Data collection took place between April 2021 and June 2022 after ethics approval and obtaining permission from relevant health departments. A team of trained field workers visited the hospitals to administer a paper-based survey to all of the consenting nurses in the hospitals, according to participation criteria. Upon arrival at each hospital, each unit manager was approached and a discussion was held between researcher, manager and staff regarding permission to do a survey among nurses in the unit. The discussion gave detailed information about the study, including the voluntary nature of participation, with an invitation to participate. The survey forms were given to the participants and they were allowed to complete them at a time convenient to them. The survey was completed anonymously, and participants were requested to return them in a sealed envelope via a sealed box with a post-box split, which was placed in all departments in the participating hospitals. The contents of these boxes were emptied by the researcher at the end of each day and removed a week later upon completion of data collection at the selected hospital.

Quantitative data analysis

Data was analysed using SPSS [ 34 ]. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the demographic data, and data from each subscale representing the practice environment, quality of care and patient safety. These described frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations. ANOVA type Hierarchical Linear Modelling (HLM), with p -values for all effects and interactions were calculated to present the differences in nurses’ perceptions of the practice environment, quality of care and patient safety across four hospital levels within the public health sector of South Africa, as the means of the different hospital levels and not the regression coefficients were important in the interpretation of the results. After the ANOVA type HLM, pair wise post-hoc comparisons were done to determine the statistically significant differences between the groups. Additionally, effect sizes were computed to determine which of these differences were important in practice. Where significant p - values lead to generalisations of results, effect sizes only indicate whether the differences in the sample groups were important in practice and are not used for generalisation if the p -values are not significant. Effect sizes were calculated and the magnitude of difference between the groups indicated as 0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large. Correlations between aspects of the nurse practice environment, quality of care and patient safety were also explored for the entire sample with 0.1. = small; 0.3 = medium and 0.5 = large relationships. Normality of the data was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, but due to the unlikelihood of non-significant p -values in such a large sample size, more significance was ascribed to results from Q-Q plots. The points in the Q-Q plot lies close enough to the straight line to retain the assumption that the data distribution is normal for all variables [ 35 ].

Demographic data

We obtained a 43.1% response rate. As indicated in Table 1 , the majority of the participants were female ( n = 1159; 88.7%), working on a full-time basis ( n = 1158; 89.35%) and in the registered nurse/midwifery category ( n = 593; 45.58%). Most nurses worked in the surgical units ( n = 483; 36.95%), and we received most participation from the central level hospitals ( n = 408; 31.22%).

- Nurse practice environment

The overall practice environment was not considered to be positive (M = 2.46; SD = 0.65), especially with regard to the subscales of nurse participation in hospital affairs (M = 2.22, SD = 0.76), staffing and resource adequacy (M = 2.23; SD = 0.80), and nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses (M = 2.39; SD = 0.81), see Table 2 .

Table 3 provides an overview of responses to items on quality of care, patient safety, and adverse events.

- Quality of care

When asked about their perception of the quality of nursing care delivered to patients in their work setting, a third of participants (38.45%; n = 486) indicated a negative outcome, and more than half of the nurses reported that they lacked confidence in patient or caregiver post-discharge care abilities (52.22%; n = 658).

- Patient safety

As indicated in Table 3 , the overall grade for patient safety was rated as poor or failing by 19.59% ( n = 248) of participants, and 430 participants (35.95%) agreed that there was a high reliance on temporary staff in their hospitals. In addition, more than half of the participants strongly agreed that their mistakes were held against them (64.38%; n = 770), and that there was a lack of support for staff involved in patient safety errors (63.15%; n = 749). Close to half felt that they could not question the decisions or actions of those in authority when related to patient safety issues (42.22%; n = 505).

Adverse events

The subscale on adverse events examined the weekly and daily occurrence of adverse events. At least 21.32% ( n = 252) of the participants experienced complaints weekly or daily, while 9.29% ( n = 108) reported a weekly or daily incidence of hospital-acquired infections, and 7.77% ( n = 93) weekly or daily medication errors.

Table 4 shows several effect sizes between the different levels of hospitals; however, only medium effect sizes will be reported on. Regarding the practice environment, there were medium practical effects between central hospitals and the small district hospitals for nurse participation in hospital affairs ( r = 0.40; p = 0.291), nursing foundations for quality of care ( r = 0.44; p = 0.469), and nurse manager ability, leadership, and support of nurses ( r = 0.45; p = 0.484), where central hospitals reported a more positive perception of these elements. There were also medium practical effects between provincial hospitals and the small district hospitals for nurse participation in hospital affairs ( r = 0.40; p = 0.211) and nursing foundations for quality of care ( r = 0.43; p = 0.398), where provincial hospitals reported a more positive perception of these elements of the practice environment.

Regarding the quality of care, there were medium practical effects with statistical significance between central hospitals and tertiary hospitals ( r = 0.54; p = 0.015) and small district hospitals ( r = 0.51; p = 0.061), where central hospitals reported better quality of care. Regarding patients’ self-care ability, there were medium practical effects between central hospitals and tertiary hospitals ( r = 0.42; p = 0.042) as well as medium district hospitals ( r = 0.41; p = 0.110) and small district hospitals ( r = 0.56; p = 0.007), where central hospitals reported more confidence in patients’ ability to manage their own care after discharge.

Regarding patient safety, there were medium practical effects between central hospitals and tertiary hospitals ( r = 0.45; p = 0.178), and also between medium district hospitals ( r = 0.44; p = 0.399), and small district hospitals ( r = 0.51; p = 0.178), where central hospitals reported higher grades of patient safety. Regarding staff feeling that their mistakes are held against them, there was a medium practical effect between small and medium district hospitals ( r = 0.42; p = 0.681), where small district hospitals reported that mistakes were held against them more often. There was also a medium practical effect between medium and large district hospitals regarding lack of support for staff involved in patient safety errors ( r = 0.44; p = 0.572), where small district hospitals reported less support for staff involved in patient safety errors. Finally, there was a medium practical effect between large and small district hospitals regarding the actions of hospital management showing that patient safety is a top priority ( r = 0.40; p = 0.856), where small district hospitals felt that the actions of hospital management showed that patient safety is a top priority.

Complaints were the only adverse event that had a medium practical effect, these effects being between provincial hospitals and large district hospitals ( r = 0.57; p = 0.056), and large district hospitals and small district hospitals ( r = 0.60; p = 0.114), where large district hospitals had a greater incidence of complaints.

As shown in Table 5 , all practice environment subscales showed medium to large negative correlations with the quality of nursing care delivered ( r = -3.20 to r = -4.28; p = 0.00) and that patients and their caregivers can manage care after discharge ( r = -0.282 to r = -0.327; p = 0.00). When considering the correlations of the practice environment on overall grade of patient safety, the practice environment had a large negative correlation ( r = -0.405; p = 0.00), especially regarding nurse foundations of quality of care ( r = -0.411; p = 0.00). Furthermore, medium negative correlations were noted between overall grade of patient safety and staffing and resources ( r = -0.347; p = 0.00) and nurse management, leadership, and support of nurses ( r = -0.340; p = 0.00), nurse participation ( r = -0.323; p = 0.00) and collegial nurse-physician relationships ( r = -0.299; p = 0.00). This shows that the more that participants agreed with positive statements about the nurse practice environment, the better they rated their quality of care, the more confidence they had in their patients’ post-discharge management, and the better they rated their overall grade on patient safety.

All practice environment items, except for collegial nurse-physician relationships, had medium negative correlations with the AHRQ item that the unit regularly reviews work processes to determine if changes are needed to improve patient safety ( r = -0.221 to r = -0.275; p = 0.00). Furthermore, foundations of quality of care showed a medium negative correlation with staff speaking up when they see something that may negatively impact patient care ( r = -0.226; p = 0.00). Nurse participation ( r = 0.235; p = 0.00), leadership ( r = 0.278; p = 0.00), collegial nurse- physician relationship ( r = 0.200; p = 0.00), and the total practice environment scale ( r = 0.259; p = 0.00) all showed medium positive correlations with the AHRQ item ‘Staff feel like their mistakes are held against them’. All practice environment subscales exhibited medium correlations with the lack of support for staff involved in patient safety errors ( r = 0.239 to r = 0.315; p = 0.00). Foundations of quality of care ( r = -0.222; p = 0.00), leadership, management, and support of nurses ( r = -0.223; p = 0.00), and the overall practice environment scale ( r = -0.219; p = 0.00) had negative medium correlations with discussing ways to prevent errors from happening again. All except the collegial nurse-physician relationship subscale of the practice environment showed medium negative correlations with staff feeling free to question the decisions or actions of those in authority ( r = -0.222 to r = -0.314; p = 0.00). All practice environment subscales had medium correlations with the actions of hospital staff showing that patient safety is a top priority ( r = -0.222 to r = -0.362; p = 0.00). To explain, the more that nurses agreed with positive practice environment items, the more they would agree to positive patient safety (AHRQ) items and the more they would disagree with negative patient safety (AHRQ) items.

Overall patient safety correlated positively and strongly with quality of nursing care delivered ( r = 0.563; p = 0.00), with a medium positive correlation with confidence in patients’ and caregivers’ post-discharge management ( r = 0.357; p = 0.00). Overall grade of patient safety also revealed a medium positive correlation with the unit regularly reviewing work processes ( r = 0.258; p = 0.00), staff feeling free to question the actions of those in authority ( r = 0.222; p = 0.00), and the actions of hospital management showing that patient safety is a top priority ( r = 0.372; p = 0.00). Regarding adverse events, overall grade of patient safety showed medium correlations with medication errors ( r = 0.208; p = 0.00) and patient falls ( r = 0.223 p = 0.00). This indicates that, as nurses rated overall patient safety more positively, they would also rate quality of care, confidence in post-discharge management, and positive items on patient safety (AHRQ) better, while at the same time leaning towards a lower incidence of adverse events occurring.

Another strong positive correlation was observed between quality of nursing care, and confidence that patients and their caregivers can manage care after discharge ( r = 0.438; p = 0.00), while medium positive correlations were noted between quality of nursing care and the unit reviewing work processes regularly ( r = 0.273; p = 0.00), staff speaking up if they see something that may negatively impact patient care ( r = 0.209; p = 0.00), staff feeling free to question the actions of those in authority ( r = 0.210; p = 0.00), and the actions of hospital management showing that patient safety is a top priority ( r = 0.305; p = 0.00). Regarding adverse events, quality of nursing care was correlated positively with medication errors ( r = 0.230; p = 0.00), patient falls ( r = 0.237; p = 0.00), and complaints ( r = 0.249; p = 0.00). This shows that the nurses rating the quality of care in their units as more positive would also have more confidence in their patients’ post-discharge management and agree more with positive patient safety items (AHRQ), while indicating a lower incidence of adverse events.

Confidence in post-discharge care and the actions of hospital management showing that patient safety is a top priority were also correlated positively on a medium level ( r = 0.216; p = 0.00). Regarding adverse events, confidence in post-discharge care was correlated positively with patient falls ( r = 0.202; p = 0.00), healthcare-associated infections ( r = 0.206; p = 0.00), and complaints ( r = 0.211; p = 0.00). To explain, this indicates that nurses with a higher rating in confidence in post-discharge management would also have a higher rating of their hospital management’s actions showing that patient safety is a top priority, while also rating the incidence of patient falls, healthcare-associated infections and complaints as occurring less often.

This national study sought to examine nurses' perceptions of the practice environment, quality of care and patient safety across four hospital levels within the public health sector of South Africa. In the participating hospitals we found that there was a negative nurse practice environment, and reports of poor quality of care and patient safety.