Biography of Samuel Johnson, 18th Century Writer and Lexicographer

Reinvented literary criticism and created the first English dictionary

Historical / Getty Images

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/JS800-800-5b70ad0c46e0fb00501895cd.jpg)

- B.A., English, Rutgers University

Samuel Johnson (September 18, 1709—December 13, 1784) was an English writer, critic, and all-around literary celebrity in the 18th century. While his poetry and works of fiction—though certainly accomplished and well-received—are not generally regarded among the great works of his time, his contributions to the English language and the field of literary criticism are extremely notable.

Also notable is Johnson’s celebrity; he is one of the first examples of a modern writer achieving great fame, in large part for his personality and personal style, as well as the massive posthumous biography published by his friend and acolyte James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson .

Fast Facts: Samuel Johnson

- Known For: English writer, poet, lexicographer, literary critic

- Also Known As: Dr. Johnson (pen name)

- Born: September 18, 1709 in Staffordshire, England

- Parents: Michael and Sarah Johnson

- Died: December 13, 1784 in London, England

- Education: Pembroke College, Oxford (did not obtain a degree). Oxford conferred a Master's degree on him after the publication of A Dictionary of the English Language.

- Selected Works: "Irene" (1749), "The Vanity of Human Wishes" (1749), "A Dictionary of the English Language" (1755), The Annotated Plays of William Shakespeare " (1765), A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland" (1775)

- Spouse: Elizabeth Porter

- Notable Quote: "The true measure of a man is how he treats someone who can do him absolutely no good."

Early Years

Johnson was born in 1704 in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England. His father owned a bookshop and the Johnsons initially enjoyed a comfortable middle-class lifestyle. Johnson’s mother was 40 years of age when he was born, at the time considered an incredibly advanced age for pregnancy. Johnson was born underweight and appeared quite weak, and the family did not think he would survive.

His early years were marked by illness. He suffered from mycobacterial cervical lymphadenitis. When treatments were ineffective, Johnson underwent an operation and was left permanently scarred. Nonetheless, he grew into a highly intelligent boy; his parents often prompted him to perform feats of memory to amuse and astound their friends.

The family's financial situation deteriorated and Johnson began to write poetry and to translate works into English while working as a tutor. The death of a cousin and a subsequent inheritance allowed him to attend Pembroke College at Oxford, though he did not graduate because of his family’s chronic lack of money.

From a young age, Johnson was plagued by a variety of tics, gestures, and exclamations—apparently beyond his direct control—that disturbed and alarmed the people around him. Although undiagnosed at the time, the descriptions of these tics have led many to believe that Johnson suffered from Tourette Syndrome. However, his quick wit and charming personality ensured that he was never ostracized for his behavior; in fact, these tics became part of Johnson’s growing legend when his literary fame was established.

Early Writing Career (1726-1744)

- A Voyage to Abyssinia (1735)

- London (1738)

- Life of Mr. Richard Savage (1744)

Johnson began work on his only play, Irene , in 1726. He would work on the play for the next two decades, finally seeing it performed in 1749. Johnson described the play as his "greatest failure" despite the fact that the production was profitable. Later critical assessment agreed with Johnson’s opinion that Irene is competent but not particularly brilliant.

After leaving school, the family’s financial situation worsened until Johnson’s father died in 1731. Johnson sought work as a teacher, but his lack of a degree held him back. At the same time, he began working on a translation of Jerónimo Lobo's account of the Abyssinians, which he dictated to his friend Edmund Hector. The work was published by his friend Thomas Warren in the Birmingham Journal as A Voyage to Abyssinia in 1735. After several years working on a few translation works which found little success, Johnson secured a position in London writing for The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1737.

It was his work for The Gentleman’s Magazine that first brought Johnson fame, and shortly afterwards he published his first major work of poetry, "London." As with many of Johnson’s works, "London" was based on an older work, Juvenal’s Satire III , and describes a man named Thales fleeing London’s many problems for a better life in rural Wales. Johnson did not think much of his own work and published it anonymously, which sparked curiosity and interest from the literary set of the time, although it took 15 years for the author’s identity to be discovered.

Johnson continued to seek work as a teacher and many of his friends in the literary establishment, including Alexander Pope , attempted to use their influence to have a degree awarded to Johnson, to no avail. Penniless, Johnson began to spend most of his time with the poet Richard Savage, who was jailed for his debts in 1743. Johnson wrote Life of Mr. Richard Savage and published it in 1744 to much acclaim.

Innovations in Biography

At a time when biography chiefly dealt with famous figures from the distant past, observed with appropriate seriousness and poetic distance, Johnson believed biographies should be written by people who knew their subjects, who had, in fact, shared meals and other activities with them. Life of Mr. Richard Savage was in that sense the first true biography, as Johnson made little effort to distance himself from Savage, and in fact, his closeness to his subject was very much the point. This innovative approach to the form, portraying a contemporary in intimate terms, was highly successful and changed how biographies were approached. This set off an evolution leading to our modern-day concept of the biography as intimate, personal, and contemporaneous.

A Dictionary of the English Language (1746-1755)

- Irene (1749)

- The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749)

- The Rambler (1750)

- A Dictionary of the English Language (1755)

- The Idler (1758)

At this point in history, there existed no codified dictionary of the English language regarded as satisfactory, and Johnson was approached in 1746 and offered a contract to create such a reference. He spent the next eight years working on what would become the most widely-used dictionary for the next century and a half, eventually supplanted by the Oxford English Dictionary. Johnson’s dictionary is imperfect and far from comprehensive, but it was very influential for the way Johnson and his assistants added commentary on individual words and their usage. In this way, Johnson's dictionary serves as a glimpse into 18th-century thinking and language use in a way that other texts do not.

Johnson put immense effort into his dictionary. He wrote a lengthy planning document setting out his approach and hired many assistants to perform much of the labor involved. The Dictionary published in 1755, and the University of Oxford conferred a Master’s degree on Johnson as a result of his work. The dictionary is still regarded highly as a work of linguistic scholarship and is frequently quoted in dictionaries to this day. One of the major innovations that Johnson introduced to the dictionary format was the inclusion of famous quotes from literature and other sources to demonstrate the meaning and use of words in context.

The Rambler, The Universal Chronicle, and The Idler (1750-1760)

Johnson wrote his poem "The Vanity of Human Wishes" while working on the dictionary. The poem, published in 1749, is again based on a work by Juvenal. The poem did not sell well, but its reputation rose in the years after Johnson’s death, and is now regarded as one of his best works of original verse.

Johnson began publishing a series of essays under the title of The Rambler in 1750, eventually producing 208 articles. Johnson intended these essays to be educational for the up-and-coming middle class in England at the time, noting that this relatively new class of people had economic affluence but none of the traditional education of the upper classes. The Rambler was marketed to them as a way of buffing their understanding of the subjects often brought up in society.

In 1758, Johnson revived the format under the title The Idler , which appeared as a feature in the weekly magazine The Universal Chronicle. These essays were less formal than The Rambler's, and were frequently composed shortly before his deadlines; some suspected he used The Idler as an excuse to avoid his other work commitments. This informality combined with Johnson’s great wit made them extremely popular, to the point where other publications began reprinting them without permission. Johnson eventually produced 103 of these essays.

Later Works (1765-1775)

- The Plays of William Shakespeare (1765)

- A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland (1775)

In his later life, still plagued by chronic poverty, Johnson worked on a literary magazine and published The Plays of William Shakespeare in 1765 after working on it for 20 years. Johnson believed that many early editions of Shakespeare’s plays had been poorly edited and noted that different editions of the plays often had glaring discrepancies in vocabulary and other aspects of the language, and he sought to revise them correctly. Johnson also introduced annotations throughout the plays where he explained aspects of the plays that might not be obvious to modern audiences. This was the first time anyone had attempted to determine an "authoritative" version of the text, a practice that is common today.

Johnson met James Boswell, a Scottish lawyer and aristocrat, in 1763. Boswell was 31 years younger than Johnson, but the two men became very close friends in a very short time and remained in touch after Boswell returned home to Scotland. In 1773, Johnson visited his friend to tour the highlands, which were regarded as a rough and uncivilized territory, and in 1775 published an account of the trip, A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland . There was in England at the time a deep interest in Scotland, and the book was a relative success for Johnson, who had been awarded a small pension by the king by this time and was living much more comfortably.

Personal Life

Johnson lived with a close friend named Harry Porter for a time in the early 1730s; when Porter passed away after an illness in 1734, he left behind his widow, Elizabeth, known as "Tetty." The woman was older (she was 46 and Johnson 25) and relatively wealthy; they married in 1735. That year Johnson opened his own school using Tetty’s money, but the school was a failure and cost the Johnsons a great deal of her wealth. His guilt over being supported by his wife and costing her so much money ultimately drove him to live apart from her with Richard Savage for a time in the 1740s.

When Tetty passed away in 1752, Johnson was wracked with guilt for the impoverished life he had given her, and often wrote in his diary about his regrets. Many scholars believe that providing for his wife was a major inspiration for Johnson’s work; after her death, it became increasingly difficult for Johnson to complete projects, and he became almost as famous for missing deadlines as he did for his work.

Johnson suffered from gout, and in 1783 he had a stroke. When he had somewhat recovered, he traveled to London for the express purpose of dying there, but later left for Islington to stay with a friend. On December 13, 1784 he was visited by a teacher named Francesco Sastres, who reported Johnson’s last words as " Iam moriturus ," Latin for "I am about to die." He fell into a coma and died a few hours later.

Johnson’s own poetry and other works of original writing were well-regarded but would have slid into relative obscurity if not for his contributions to literary criticism and the language itself. His works describing what constituted "good" writing remain incredibly influential. His work on biographies rejected the traditional view that a biography should celebrate the subject and instead sought to render an accurate portrait, transforming the genre forever. The innovations in his Dictionary and his critical work on Shakespeare shaped what we have come to know as literary criticism. He is thusly remembered as a transformative figure in English literature.

In 1791, Boswell published The Life of Samuel Johnson , which followed Johnson’s own thoughts on what a biography would be, and recorded from Boswell’s memory many things that Johnson actually said or did. Despite being subjective to a fault and larded with Boswell’s obvious admiration for Johnson, it is regarded as one of the most important works of biography ever written, and elevated Johnson’s posthumous celebrity to incredible levels, making him an early literary celebrity who was as famous for his quips and wit as he was for his work.

- Adams, Michael, et al. “What Samuel Johnson Really Did.” National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) , https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2009/septemberoctober/feature/what-samuel-johnson-really-did.

- Martin, Peter. “Escaping Samuel Johnson.” The Paris Review , 30 May 2019, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2019/05/30/escaping-samuel-johnson/.

- George H. Smith Facebook. “Samuel Johnson: Hack Writer Extraordinaire.” Libertarianism.org , https://www.libertarianism.org/columns/samuel-johnson-hack-writer-extraordinaire.

- Samuel Johnson Quotes

- Samuel Johnson's Dictionary

- lexicographer

- Biography of Samuel Beckett, Irish Novelist, Playwright, and Poet

- Biography of James Weldon Johnson

- Definition and Examples of Codification in English

- Eliza Haywood

- The Life and Work of Voltaire, French Enlightenment Writer

- Biography of Aldous Huxley, British Author, Philosopher, Screenwriter

- Key Events in the History of the English Language

- Definition and Examples of Lexicography

- What Is Bowdlerism and How Is It Used?

- Biography of Georgia Douglas Johnson, Harlem Renaissance Writer

- How Do You Rate as an Expert of the English Language?

- Periodical Essay Definition and Examples

- Biography of Mary Shelley, English Novelist, Author of 'Frankenstein'

Samuel Johnson: Biography of the Renowned 18th Century English Writer

- by history tools

- November 19, 2023

Full Name: Samuel Johnson Also Known As: Dr. Johnson

Birthday: September 18, 1709 Birthplace: Lichfield, Staffordshire, England Death Date: December 13, 1784 (aged 75)

Resting Place: Westminster Abbey, London Occupation: Essayist, lexicographer, biographer, poet, critic

Samuel Johnson, affectionately known as Dr. Johnson, was a prominent English writer who lived during the early 18th century. He was a legendary literary figure in his own lifetime who made lasting contributions as a poet, biographer, lexicographer, and one of the greatest critics in the history of English literature. Johnson is considered by many to be the most distinguished man of letters in British history.

Born on September 18, 1709 in Lichfield, Staffordshire, Johnson faced significant health problems growing up, including scrofula and near blindness. Thanks to the support of a wealthy patron, he attended Oxford University, but financial struggles forced him to leave without a degree. After working as a schoolteacher, Johnson eventually moved to London in 1737 to pursue a career in writing.

Through his early journalism and poetry, Johnson gained respect among London‘s literary circles. His most iconic work, the Dictionary of the English Language , was published in 1755 and immediately became the standard reference for English vocabulary and spelling. As Virginia Woolf later declared, "With the dictionary, Johnson set standards for the language which endured for over a century."

Beyond his dictionary, Johnson made major contributions across several genres. His periodical essays in The Rambler established his reputation as a moral thinker and innovative prose stylist. As a critic and biographer, he helped define the modern principles of journalism and biography that we still rely on today. By the end of his life, Johnson had become a legendary figure, honored even by King George III. He died in London on December 13, 1784 at the age of 75.

Here is a more in-depth look at the fascinating life and diverse literary accomplishments that make Samuel Johnson such an icon of English literature:

Early Life and Education

Samuel Johnson was born on September 18, 1709 in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England. His father Michael Johnson was a bookseller, and his mother Sarah Ford was 40 years old when she gave birth to Samuel. He was plagued by health issues as a child, including scrofula and near blindness that left him scarred and affected his vision his entire life.

Johnson attended Lichfield Grammar School but always felt self-conscious about his disfigured face and impoverished background. However, his brilliance was clear from an early age. A wealthy patron named Andrew Corbett funded Johnson‘s further education, allowing him to attend Oxford University‘s Pembroke College in 1728.

At Oxford, the boisterous Johnson was unimpressed by the university‘s pretentious intellectualism. He left Oxford in 1729 unable to afford the tuition. This early experience shaped his view of "ivory tower" academics disconnected from the real world.

Move to London and Literary Success

Unable to complete his degree, Johnson took on schoolteacher positions in the Birmingham area during the 1730s. Finding little opportunity there, he decided to pursue his passion for writing by moving to London in 1737.

Johnson lived in poverty early in his London years, writing frequently for The Gentleman‘s Magazine to make ends meet. Despite physical ailments and depression, Johnson immersed himself in the city‘s thriving literary community. He befriended luminaries like painter Joshua Reynolds and poet-adventurer Richard Savage.

Johnson‘s first major work was his satirical poem London in 1738, which critiqued urban life. The same year, he published a philosophical novella The Prince of Abissinia . This established his reputation as an innovative moral thinker attuned to modernity.

Johnson‘s breakthrough work was his comprehensive Dictionary of the English Language , published in 1755. It catalogued over 40,000 words with detailed definitions and literary examples, bringing order and elegance to the unruly English language. The dictionary was a huge success, earning Johnson widespread fame.

Prolific Output in Later Years

Now a bona fide celebrity, Johnson entered his most productive period. His groundbreaking essays in The Rambler (1750-1752) pioneered a new informal, conversational prose style that influenced essayists for generations.

From 1759-1762, Johnson published the innovative fictional work Rasselas , along with scholarly editions of Shakespeare‘s plays that remain influential today. His moral fable The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia marked his creative high point as a fiction writer.

In the 1770s and 1780s, Johnson applied his critical eye to biography in works like The Lives of the Poets , his renowned series of biographical essays on giants of English poetry. He also published thoughtful travelogues and social commentary, like his Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland .

Johnson continued working tirelessly almost until his death in London at age 75 on December 13, 1784. His close friend James Boswell‘s famous biography The Life of Samuel Johnson cemented the writer‘s legacy for generations to come.

Legacy and Influence

Few writers have left as broad an imprint on English literature as Samuel Johnson. His dictionary standardized the English language for over a century. His literary criticism and biographical essays established models for modern journalism and non-fiction. As a poet and moral thinker, he conveyed timeless insights in a new conversational style.

From Charles Dickens to Virginia Woolf, Johnson‘s influence can be seen across all eras of English literature after him. His penetrating intellect and vast contributions proved that a life wholly dedicated to the arts could leave an enduring cultural legacy. For any lover of literature and language, Johnson remains both an inspirational model and a writer who deserves to be rediscovered by each new generation.

Related posts:

- Chris Kyle: Legendary Navy SEAL Sniper and American Hero

- Pippa Middleton

- The History of Charles Babbage & The First Digital Computer

- Should Elon Musk Avoid Travel to Russia? Analyzing the Risks After Starlink‘s Role in Ukraine

- Meet Pop Icon Taylor Swift

- Brooke Monk: The Multi-Talented TikTok Trailblazer

- William Levy – The Talented Cuban American Actor Who Has Won Over Millions of Hearts

- Introducing Sarah Jakes Roberts: An Inspiring Voice of Hope

Biography Online

Samuel Johnson Biography

Samuel Johnson (usually known as Dr Johnson) (18 September 1709– 13 December 1784) was an English author, poet, moralist and literary critic. One of Dr Johnson’s greatest contributions was publishing, in 1747, The Dictionary of the English Language .

“Mankind have a great aversion to intellectual labor; but even supposing knowledge to be easily attainable, more people would be content to be ignorant than would take even a little trouble to acquire it.”

Samuel Johnson

Short Bio of Samuel Johnson

He was educated at Lichfield Grammar School before going to Pembroke College, Oxford. However, due to a lack of funds, he left after a year – never completing his degree. After Oxford, he worked as a teacher in Market Bosworth and Birmingham. In 1735, he married Elizabeth Porter, a widow 20 years older than him. Together they opened a school at Edial near Lichfield, but it later closed due to a lack of money. The Johnson’s then left for London, where he began spending more time working as a writer.

He made a living writing for the Gentleman’s Magazine – a report on Parliament. He also wrote a tragedy, Irene , and some attempts at poetry.

Johnson was also employed to catalogue the extensive library of Edward Harley, Earl of Oxford. This gave Johnson the opportunity to indulge his great love of reading and the English language. He was inspired to start working on a comprehensive dictionary of the English language. It would take him eight years, but it was considered to be his finest achievement. Though other dictionaries were in existence, the ‘Johnson Dictionary of the English language’ was a huge step forward in its comprehensiveness and quality.

Johnson was a prolific writer. For two years he almost single-handedly wrote a journal – ‘ The Rambler’ full of moral essays.

In 1752, his wife ‘Tetty’ died, plunging him into depression, which proved difficult for him to escape during the rest of his life.

After the publication of his dictionary in 1755, he began to be more appreciated by literary society. He was awarded an honorary degree by Oxford University, and in 1760 was given a pension of £300 a year from George III. This enabled him to engage in more social and cultural activities. He was friends with many of the leading cultural figures of the day, such as Sir Joshua Reynolds a painter, and the writer Oliver Goldsmith.

In 1764, he met the young Scot, James Boswell who would become his celebrated biographer. Together they toured the Hebrides, which Johnson wrote about in ‘A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland’, (1775) James Boswell wrote about Johnson in great detail, including information on Johnson’s unusual mannerisms, such as odd gestures and tics (which may have been a form of Tourette’s syndrome)

Johnson also embarked on an ambitious project – “Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets” (10 vols) and an influential edition of Shakespeare’s plays.

“Few things are impossible to diligence and skill. Great works are performed not by strength, but by perseverance.”

– Samuel Johnson

Towards the end of his life, Johnson was resentful after his housemaid, and friend Hester Thrale left him and married an Italian musician. After a series of illnesses, he died in 1784.

After his death, his contributions to English literature were increasingly admired. He had left a great body of work and was credited with being England’s finest literary critic of his time.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Samuel Johnson ”, Oxford, UK www.biographyonline.net , 22nd Jan 2013

Samuel Johnson: The Major Works

Samuel Johnson: The Major Works at Amazon

Johnson Dictionary

Samuel Johnson: A Dictionary of the English Language at Amazon

Related pages

- Inspiring Stories

- Relationship First

- Behind The Scenes

- Write for Us

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Editorial Guideline

- California Privacy Rights

- EU Privacy Perferences

- Do Not Sell My Info

Copyright ©2024 Biography Host

- Birth Date Sep 18, 1709

- Full Name Samuel Johnson

- Occupation Poet, Lexicographer, Playwright, Essayist, Literary critique, Biographer

- Nationality British

- Birthplace Lichfield, Staffordshire, England

- Death Date Dec 13, 1784 (aged 75)

"What is written without effort is in general read without pleasure."

"The fountain of content must spring up in the mind, and he who hath so little knowledge of human nature as to seek happiness by changing anything but his own disposition, will waste his life in fruitless efforts and multiply the grief he proposes to remove."

"There is no tracing the connection of ancient nations, but by language; and therefore I am always sorry when any language is lost, because languages are the pedigree of nations."

"Language is only the instrument of science, and words are but the signs of ideas: I wish, however, that the instrument might be less apt to decay, and that signs might be permanent, like the things they denote."

Samuel Johnson | Biography

In 1747, Johnson came up with a plan for 'A Dictionary of the English Language.' The dictionary aimed to explain different meanings of the word by using quotations from famous and influential authors. After the publication of the dictionary in 1755 and its abridgment in 1756, it received high critical acclaim due to its rich sense divisions, rich categorization of word's significance and meaning, and witty definitions with cultural assertiveness and conservative perspective to bind the language.

- By Grishma Giri

- Update : May 13, 2021

Samuel Johnson was one of the most respected literary figures of the 18th century. His dictionary, 'A Dictionary of the English Language,' published in 1755, would become an essential piece of literary work of that era.

Who is Samuel Johnson?

Samuel Johnson was a famous 18th-century poet, lexicographer, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critique and biographer. He is noted for publishing a dictionary back in 1755, for which he was given an honorary doctorate by Dublin University in 1765. He would also be later known as Dr. Johnson because of the degree. Although he started his formal career as an undermaster at Market Bosworth Grammar school, he is noted for being one of the brilliant minds in the field of literature.

Early Life and Education

Born on 18 September 1709 in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England, Samuel Johnson was the eldest son of Michael Johnson and Sarah (Ford) Johnson. His father was a bookseller at Sadler Street, Lichfield, and his mother was a housewife. Johnson's early childhood was full of illnesses and sorrow. He had mentioned in his own accounts that he was born "almost dead."

While growing up, he battled scrofula, which is tuberculosis of the lymphatic glands, along with partial blindness in the left eye and some indication of Tourette syndrome. At that time, it was believed that the monarch's touch could cure scrofula. That is also the reason why scrofula was called King's evil. So, at the age of two and half years, he was taken to Queen Anne. On 30 March 1712, he was touched by the queen. The gold touch piece was among one of his precious possessions, which he had kept with him for the remainder of his life.

After many medical procedures to improve his health condition, he started to get better. Yet, this good health came at the price of many mutilating scars on his face and neck. Johnson was a well-built person. He was tall, and along with time, he became huge. He was also strong and energetic. He loved to swim, walk and ride.

In 1717, Johnson was enrolled in Litchfield Grammar School to learn Greek and Latin. He was an intelligent chap who also had a fair share of arrogance and indolence. His master in the school, John Hunter, was an orthodox teacher of that time. Hunter believed in learning through brutal methods. Later, when Johnson published his first dictionary, ' A Dictionary of the English Language' on 15 April 1755, he defined "school" as "house of discipline and instruction."

Though Johnson's school environment was full of terror under Hunter's mastership, the company of future life-ling friends, Edmund Hector and John Taylor, would make it seem tolerable. Later in life, Edmund Hector became a surgeon, and John Taylor became prebendary of Westminster and justice of the peace for Ashbourne.

Invitation From Cornelius

At the age of seventeen, Johnson was invited to spend nine months with his cousin Cornelius Ford at Pedmore, Worcestershire. He believed it was his liberation from the oppressive Lichfield. Ford was fourteen years older than Johnson. He was a well-educated scholar who had served a fellowship at Cambridge. For these reasons, Johnson believed that his pursuit of academics would flourish under the guidance of his worldly cousin. He would read the works of poets Matthew Prior and Samuel Garth along with the playwright William Congreve during his stay with his cousin. These writers influenced him to the extent that they were quoted frequently in his dictionary.

In the year 1728, Johnson started a new journey of his life in Pembroke College, Oxford. Through the inheritance of a distant relative and the generosity shown by his old friend from Lichfield Grammar School, Johnson managed to get into the college. This journey could not last more than 13 months as he ran out of funds. As a result, he had to leave his college.

Career and journey to literature

In 1731, Johnson made his first publication. It was a Latin translation of Alexander Pope's ' Messiah' which appeared in A Miscellany of Poems. Alexander Pope was among the leading poets of that time. This is also a reason why Johnson would comment on his achievement in most of his writings.

Later in 1731, Johnson took up a career as undermaster at Market Bosworth Grammar School. He did not like his position much as he thought it was untenable. The arrogance and rudeness of Sir Wolstan Dixie, who was in charge of his appointments, made it so. Johnson left his job and later described his feelings as escaping from prison. With just twenty pounds of inheritance from his father after his death, he went through some tough times.

Johnson moved to Birmingham to his friend Hector after failing in the pursuit of the teaching profession. During his stay in Birmingham, he published some of his essays in ' The Birmingham Journal' in 1732-1733. In 1735, he published an English translated version of ' A Voyage to Abyssinia' by Father Jerome Lobo with some help from his friend Hector. The book was an account of a Jesuit missionary expedition which was first translated into French by Joachim Le Grand in 1728. Johnson then translated the French edition of the book to English. This work of his showed some signs of matureness in his writing. It could also be seen in the book's preface, in which he praises Lobo for not attempting to present marvels. He writes, "He meets with no basilisks that destroy with their eyes, his crocodiles devour their prey without tears, and his cataracts fall from the rock without deafening the neighbouring inhabitants."

Marrying A Widow Twenty Years Younger

Johnson married Elizabeth Porter in 1735. Although she was twenty years older than him and was a widow, he chose her because he found her both attractive and intelligent. Porter belonged to a well-off family, so after their marriage, his financial status improved drastically. With her help, he opened a school at Edial in 1735. The school, Edial Hall School, was very near to Lichfield, his hometown. There, Johnson taught Latin and Greek to three young gentlemen. But, the school did not do well and ran out of funds. As a result, it had to be shut down after a year.

After closing the school, Johnson began to work on his historical tragedy, 'rene.' It was a neoclassical tragedy. The play dramatized the love of Sultan Mahomet towards Irene, who was a Christian slave captured in Constantinople. Although he started this play while he was working in his father's bookstore back in 1726, he had not been able to complete it. After knowing that his play was taking shape, he became very impatient to bring the play to the city stage. Therefore, in 1737, he moved to London.

Writer On Gentleman's Magazine

In London, Johnson found a job as a writer in Gentleman's Magazine. It was the first time in that era something termed magazine was published. Many scholars believe that during this time, he honed his skills to become a better writer. Henry Hitching, who is an author, reviewer, and critic, commented about Johnson's time in Gentleman's Magazine as "accustomed him to the vicissitudes and duties of a life of writing, an existence that combined studious drudgery with occasional opportunities for creative flair."

'Life of Mr Richard Savage.'

While Johnson was continuing his career as a writer, he came across Richard Savage. He then befriended the poet, who was not very well known for his character. Savage was impulsive, violent, depressive, and had a hedonistic lifestyle. Savage died in the debtor's prison in 1744. This gave Johnson the push to write a biography of his troubled friend. In the same year, he published 'Life of Mr Richard Savage.' The book did not bring any financial wonders to him, yet it helped his growing reputation as a writer.

Although Johnson was securing literary success in London, things were not going well with his conjugal life. His friendship with Savage was something his wife detested very much. Yet, when she grew ill, he returned to her and started to take care of her. They also started to have financial crises. It became his priority to indulge in a steady work that would pay him handsomely. During this time in 1746, a publisher named Robert Dodsley came to him with a proposition to compile a comprehensive, modern dictionary of the English language.

'A Dictionary of the English Language' And Later Career

In 1747, Johnson came up with a plan for 'A Dictionary of the English Language.' He then presented his plan to statesman Philp Dormer Stanhope also known as Lord Chesterfield. Lord Chesterfield ignored his idea and sent him ten pounds as compensation for his efforts. But, Johnson's only intention to create the dictionary was to stabilize the language. He wanted to set uniformity in the usages and pronunciation. He did not want his version of the dictionary to impose rigid rules like how dictionaries of the continental academics did.

The dictionary aimed to explain different meanings of the word by using quotations from famous and influential authors. After the publication of the dictionary in 1755 and its abridgment in 1756, it received high critical acclaim due to its rich sense divisions, rich categorization of word's significance and meaning, and witty definitions with cultural assertiveness and conservative perspective to bind the language. The abridged version of his dictionary remained the standard English dictionary for 66 years until Noah Webster published his version in 1828. Lord Chesterfield later wanted to show his support to him, which Johnson completely refused.

In 1749, Johnson published 'The Vanity of Human Wishes.' It was an imitation of the Latin poet Juvenal's tenth 'Satire.' The poem's interpretation created a debate among people who found it as 'pessimism at human vanity and those who found it as 'hope for humanity's redemption.' In the same year, his play 'Irene' was produced by David Garrick. Johnson received three hundred pounds for it, which was a hefty sum of money at that time.

After his mother's illness, he wrote 'The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia, in April 1759 to cover her medical expenses. Originally titled 'The Prince of Abissinia: A Tale,' it is an apologue about bliss and ignorance. The book was said to be a work of philosophical and practical importance. Some of the critics also classified it as a novel because of the complexity of the work.

In 1755, Johnson was awarded an honorary M.A. degree by Oxford for his scholarly successes. Later in 1765, he was again awarded another honorary degree of LL.D by Dublin University. After 1762, he was in a position where he did not need to write regularly to support himself financially. Though there were some controversies, he accepted the three hundred pounds annual pension from Lord Bute's ministry.

Meeting James Boswell And 'The Lives of the English Poets'

Johnson met and befriended James Boswell in 1763. Boswell was 31 years younger, but the bond he had with him was beyond age. Maybe that is the reason why Boswell wrote 'Life of Samuel Johnson' in 1791, which was an intimate and detailed biography of his beloved friend. Both Johnson and Boswell embarked upon the journey to Scotland, which was Boswell's native place. Samuel Johnson's 'A Journey to the Western Island of Scotland' was published in 1775 was an outcome of that journey.

Johnson spent the other half of the 1770s working on 'The Lives of the English Poets.' This project of his was originally designed as a series of biographical introductions of the English Poets. Although it was supposed to be 60 volumes, the texts were published on their own. This work of his became extremely popular and happened to be one of the influential works in the field of biography.

At the age of 75, on 13 December 1784, Samuel Johnson bid his final farewell to everyone and left behind some marvelous works of literary criticism, lexicography, biography, and many literary works.

Fact-checking and Ethical Concerns

We assure our audience that we will remove any contents that are not accurate or according to formal reports and queries if they are justified. We commit to cover sensible issues responsibly through the principles of neutrality.

To report about any issues in our articles, please feel free to Contact Us . Our dedicated Editorial team verifies each of the articles published on the Biographyhost.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Everything, everywhere, all at once (kind of)

Acclaimed poet receives Arts Medal

DuVernay on exploring racism, antisemitism, caste in ‘Origin’

Johnson at 300.

Corydon Ireland

Harvard News Office

Celebrating a man of letters whose words still sing and sting

Samuel Johnson’s “Dictionary of the English Language” was first published in 1755 as his attempt to both rein in and celebrate the galloping vigor of English. For 150 years, it was considered the pre-eminent compilation of its kind.

But Johnson — born 300 years ago this coming Sept. 18 — was more than its author. He was England’s most famous man of letters, rising from humble origins as the son of a provincial bookseller to become an accomplished poet, literary critic, playwright, essayist, and (not least) conversationalist.

Johnson — in all his fullness, contradiction, erudition, and energy — was remembered, reviewed, and revered late last month (Aug. 27-29) in a Harvard literary celebration.

The three-day event, “Johnson at 300: A Houghton Library Symposium,” drew more than a hundred Johnsonians from all over the world. A few were unaffiliated with the academy, including a Boston software designer, a Texas biology student, a retired New York City trial lawyer, and a Florida judge who not long ago was kicking down doors as a prosecutor on police raids.

The symposium was the largest scholarly celebration of Johnson this year in the United States, said organizer Thomas Horrocks, Houghton’s associate librarian for collections. He called the author “this good and great man.”

The gathering came with a bonus: “ A Monument More Durable than Brass ,” a Houghton exhibit that samples the library’s 15,000-item Donald and Mary Hyde Collection of Dr. Samuel Johnson. Look for Johnson’s earliest surviving letter, his earliest diaries (kept in Latin), rare manuscript fragments from the original “Dictionary,” and even the great man’s silver teapot. The larger collection itself, at Harvard since 2004, “is the greatest gift an archivist could have,” said Houghton assistant curator John H. Overholt.

During sessions at Emerson Hall and Lamont Library, presenters drew Johnson through multiple cultural and literary filters: revolution, fledgling America, gender, religion, the book trade, intellectual history, fine arts, and the “circle” (including his biographer and fellow depressive James Boswell).

Understandably, one symposium trope was Johnson and his influence on the art of biography, both as a writer and a subject. His six-volume “Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets,” published just a few years before he died, enlivened the genre and recast it as a literary form. And his fame was assured by Boswell’s “The Life of Samuel Johnson,” itself a landmark of biography.

Understandably also, there were two sessions on Johnson’s “Dictionary,” which took him nine years to write — though 80 percent of the work went into a feverish last 18 months, according to speaker Anne McDermott. She teaches at the University of Birmingham (U.K.) and has for 20 years been working on a scholarly edition of the 42,000-entry tome.

McDermott delivered a paper on Johnson’s compilation methods that argued, in part, that he wrote the dictionary twice, abandoning the first version after possibly getting as far as “U.”

She also noted allusions of guilt in Johnson’s essays written concurrently with the dictionary — guilt at not finishing sooner. The same passages also echo his self-confessed admission of the dictionary’s imperfections. “The profit is less,” one passage reads, “than hope had pictured it.”

Also informing the symposium was Johnson’s ceaseless and untrammeled commentary on the world around him, including what he considered the grasping barbarity of England’s American cousins. He declared, famously, “I am willing to love all mankind, except an American,” and once called on slaves and American Indians to rise up against the rebels.

Johnson also disliked imperial expansion, whether by England, France, or by a young America that was seemingly bound to exterminate its native peoples. He hated black slavery too, which was both another bite at upstart Americans and another sign of his moral prescience.

“The wisdom of his scruples about America,” said Johnson scholar Thomas M. Curley of Bridgewater (Mass.) State College, “deserves special consideration.”

Share this article

You might like.

There’s never a shortage of creativity on campus. But during Arts First, it all comes out to play.

Kevin Young ’92 reflects on what took root at Harvard and how it’s grown

Despite horrors, film ‘a collection of love stories’

How old is too old to run?

No such thing, specialist says — but when your body is trying to tell you something, listen

Alcohol is dangerous. So is ‘alcoholic.’

Researcher explains the human toll of language that makes addiction feel worse

Cease-fire will fail as long as Hamas exists, journalist says

Times opinion writer Bret Stephens also weighs in on campus unrest in final Middle East Dialogues event

open search

- Open Today: 10 a.m.–5 p.m.

Samuel Johnson: Literary Giant of the 18th Century

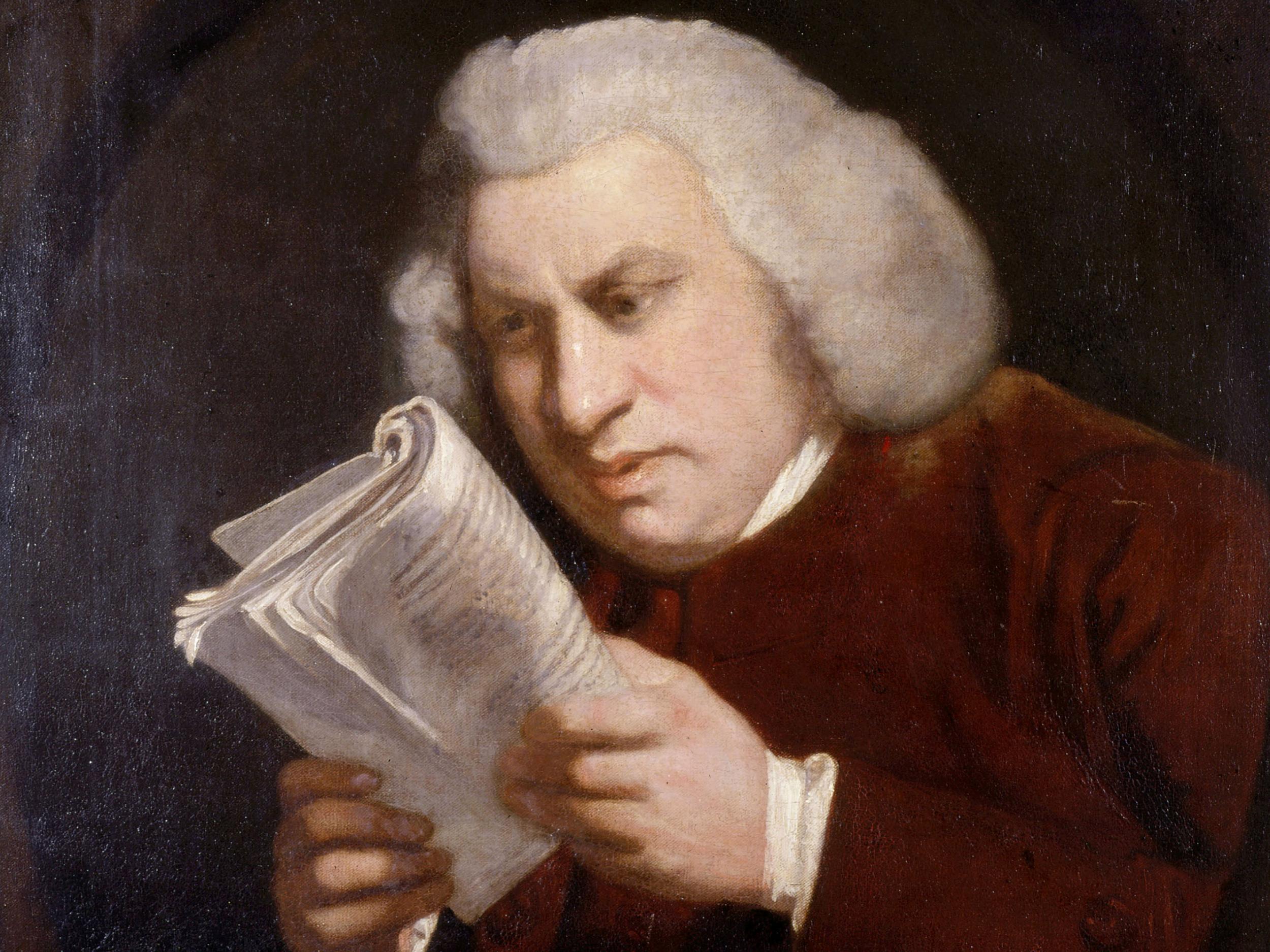

The famous "Blinking Sam" portrait of Samuel Johnson, painted by his friend Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1775. © Huntington Library.

Samuel Johnson (far right) converses with his friend James Boswell (center) and author Oliver Goldsmith in an engraving titled "The Mitre Tavern," 1880. Courtesy of Loren Rothschild.

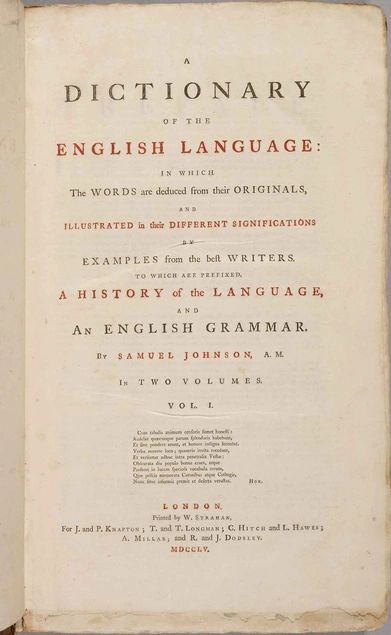

A first edition of Johnson's famous Dictionary of the English Language , published in 1755 in two volumes. Courtesy of Loren Rothschild.

New exhibition celebrates Samuel Johnson, author of the first English dictionary

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)—one of the greatest moralists, poets, biographers, critics, essayists, and correspondents of all time—so dominated literary and intellectual life in the last half of the 18th century that the era is frequently referred to as the “Age of Johnson.” As a conversationalist and writer he was so insightful and adept in the use of language that only Shakespeare and the Bible are quoted more often.

Samuel Johnson: Literary Giant of the 18th Century , a new exhibition opening May 23 and continuing through Sept. 21 in the West Hall of the Library, tells the story of Johnson’s life and achievements through a display of rare books, manuscripts, and portraits drawn from The Huntington’s holdings and from the Loren and Frances Rothschild Collection. The exhibition is curated by noted Johnson scholar O. M. “Skip” Brack, professor emeritus of English at Arizona State University.

One of the earliest English authors to make his living solely by his writings, Johnson spent his early years, after arriving in London in 1737, writing mostly for the Grub Street booksellers. Needing a large project that would produce a steady income, he accepted a commission to write an English dictionary. On April 15, 1755, after Johnson had labored over it for nine years, a consortium of London booksellers published, in two large volumes, A Dictionary of the English Language: In which the Words are Deduced from their Originals, and Illustrated in their Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers . This colossal achievement brought Johnson fame not only in England but across Europe.

A first edition of the Dictionary in its original binding will be one of the highlights of the exhibition. Other treasures to be displayed are the famous “Blinking Sam” portrait of Johnson by his friend Sir Joshua Reynolds, a portion of one of Johnson’s diaries, and a number of personal letters.

Johnson’s prolific output as a writer included his famous poem The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749), more than 200 essays for his twice-weekly publication, The Rambler (1750–52), and the allegorical fable Rasselas: The Prince of Abyssinia (1759). His edition of Shakespeare (1765) and the Lives of the Poets (1779–81) secured his fame as a literary critic and biographer.

Brack notes that while Johnson could occasionally be difficult and argumentative, his work reveals a deeply compassionate nature. “All of Johnson’s writings, although not often personal in an autobiographical sense, have the touch of his humanity—an essential understanding of the trials and joys of life that we all share.”

SUGGESTED READING LIST

Editions of Johnson’s Works The Essays Of Samuel Johnson: Selected From The Rambler, 1750–52 ; The Adventurer, 1753 ; And The Idler, 1758–60 . Kessinger Publishing, 2007. The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia . Various publishers. Johnson’s Dictionary: A Modern Selection . Dover Books, 2005. Letters of Samuel Johnson, edited by Bruce Redford. Princeton University Press, 1992–94. Lives of the Poets: A Selection . Oxford University Press, 2009. Samuel Johnson: The Major Works . Oxford University Press, 2009. Samuel Johnson , edited by Donald Greene. Oxford University Press. Various editions. Yale Edition of the Works of Samuel Johnson . Yale University Press. 1958–2004.

Works about Johnson W. Jackson Bate, Life of Samuel Johnson . Harcourt Brace, 1977. James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson . Various publishers. Sir John Hawkins, The Life of Samuel Johnson . University of GeorgiaPress, 2009. Peter Martin, Samuel Johnson: A Biography . Belknap Press, 2008. Jeffrey Meyers, Samuel Johnson: The Struggle . Basic Books, 2008. John Wain, Samuel Johnson . Viking Press, 1975.

RELATED EVENTS

Lecture: “Samuel Johnson and His Famous Dictionary” May 27 (Wednesday) 7:30 p.m. Loren Rothschild, a noted collector of the works of Samuel Johnson, will talk about how Johnson created his great dictionary.

Lecture: “Johnson Agonistes: Portraying Samuel Johnson” June 8 (Monday) 7:30 p.m. Richard Wendorf, Stanford Calderwood Director and Librarian of the Boston Athenaeum, will survey all of the known portraits of Johnson, including the famous portrait by Reynolds now at The Huntington.

Lecture: “Sam and Jamie: ‘No Theory Please, We’re British’” Sept. 9 (Wednesday) 7:30 p.m. Paul Ruxin, a corporate lawyer and Johnson collector, will discuss the famous relationship between Samuel Johnson and James Boswell.

All lectures take place in Friends’ Hall and are free to the public. No reservations required.

Gallery Guide

Quick links.

- Plan Your Visit

UK Edition Change

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Paris 2024 Olympics

- Rugby Union

- Sport Videos

- John Rentoul

- Mary Dejevsky

- Andrew Grice

- Sean O’Grady

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Fitness & Wellbeing

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Car Insurance Deals

- Lifestyle Videos

- UK Hotel Reviews

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Australia & New Zealand

- South America

- C. America & Caribbean

- Middle East

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Today’s Edition

- Home & Garden

- Broadband deals

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Solar Panels

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

- Betting Sites

- Online Casinos

- Wine Offers

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

Samuel Johnson: Who was he, and why is he so important to the English language?

Today's google doodle celebrates a colossus of english literature, article bookmarked.

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails, thanks for signing up to the breaking news email.

Today’s Google Doodle pays tribute to Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), English wit and author of the Dictionary of the English Language , on the 308th anniversary of his birth.

Johnson’s dictionary appeared in 1755 and remains a landmark achievement of English prose, an extraordinary individual undertaking that included over 42,000 entries and took its writer nine long years to assemble.

But who was Johnson? What else was he known for and why has his legacy endured beyond that of his many illustrious eighteenth century peers?

The best Google Doodles

Samuel Johnson was born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, the son of a bookseller. He attended Prembroke College, Oxford, in his late teens but struggled to afford the fees, complained of the intellectual idleness of his contemporaries and felt humiliated when a fellow student took pity on him and presented him with a replacement pair of shoes as a gift.

The great man left university without completing his degree and launched himself into the coffeehouses and print shops of literary London, living a life of genteel poverty, forever under threat from his creditors. His earliest works included the long-form poems ‘London’ and ‘The Vanity of Human Wishes’ and the periodicals The Rambler and The Idler .

Having completed the mammoth task of assembling the dictionary, a commission for which he was handsomely reimbursed, Johnson wrote an analysis of Shakespeare and a biography of his friend Richard Savage, a poet convicted of murder.

A rare foray into fiction, The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia (1759), followed and proved a commercial success. The novella was an exotic philosophical fable that told the story of a wayward young royal’s decision to leave behind his isolated homeland, the Happy Valley, in search of true contentment in the wider world.

The primary reason for Johnson’s enduring appeal though, outside of his own remarkable achievements in print, is surely the ongoing popularity of James Boswell’s fantastically detailed Life of Samuel Johnson (1791). The book recounts the many wise, comic and vitriolic sayings its subject produced when “talking for victory” late into the night with his peers and clubmates. That circle included such great figures of the age as portrait painter and Royal Academy founder Joshua Reynolds, actor David Garrick, politician Edmund Burke and playwright Oliver Goldsmith.

- Samuel Johnson's 10 finest quotes and witticisms

Boswell recalls such delightful comic incidents as Johnson good-naturedly dismissing Burke as “a vile Whig”, rebuking Goldsmith for being “loose in his principles” and declining a repeat visit backstage to visit Garrick at the theatre because, “the silk stockings and white bosoms of your actresses excite my amorous propensities.” His opinions on everything from remarriage ("the triumph of hope over experience") to women vicars and the merits of Alexander Pope are preserved for the ages in a work whose value cannot be overstated.

Boswell would also document Johnson’s tour of Scotland in his company, while his life was recorded in a separate biography by another friend, the socialite Mrs Hester Thrale, who published her own reminiscences of their time together in 1786.

Today, a statue of Johnson looks out over his former stomping ground of Fleet Street while his name has lived on in the title of a leading prize for non-fiction writing (lately rechristened the Baillie-Gifford), the most recent recipient of which was Philippe Sands.

Modern audiences will no doubt remember Robbie Coltrane’s performance as “the Great Cham” in the BBC sitcom Blackadder The Third (1987) while fans of his famous barbed tongue include stand-up comedian Frank Skinner, who became president of the Dr Johnson Society in 2010.

The good doctor’s namesake, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson , is another admirer, including him in his 2011 book Johnson’s Life of London and devoting an episode of BBC Radio 4’s Great Lives to his memory.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

New to The Independent?

Or if you would prefer:

Want an ad-free experience?

Hi {{indy.fullName}}

- My Independent Premium

- Account details

- Help centre

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Nothing but the truth

The final paragraph of my BS Johnson biography, Like A Fiery Elephant, begins: "These are the last words I intend to write about BS Johnson." I've spent most of the past few months eating them. Not that I'm complaining. It's wonderful when a book reaches a wider audience and sends out more ripples than you ever imagined it would. When I signed up, back in 1995, for the task of writing a biography of an experimental novelist who had only reached a small (though devoted) audience in his lifetime, and had been pretty much forgotten ever since, all I had to motivate me was a modest advance and a burning admiration for his work. The response of most people whenever I discussed the project was to give me pitying looks. Even when the book was published, one of the most favourable reviews ended with the prediction that "it will probably be read by about two or three hundred people".

The fact that Johnson's appeal is turning out to be far more enduring and far more widespread than expected raises some interesting questions. First of all, it is simply testament to his own gifts. He was certainly one of the best British prose stylists of the 1960s and on that subject I can do no better than quote the poet and novelist Adrian Mitchell's words from 1964: "Mr Johnson is a fine poet and he writes the prose of a fine poet. Every word is weighed for its rhythmic effect as well as for its sense and sound."

It's good to remember, incidentally, that Johnson began his working life as a poet, one whose preferred mode was the confessional, and who would only allow himself one subject: "nothing else but what happens to me". It may have been a common enough view in poetic circles at the time, but Johnson was perhaps the only person to carry this aesthetic over into the novel. Like many novelists (myself included), he started off by writing about thinly fictionalised versions of himself. In the early 1960s, as an impoverished poet forced to earn his living by supply teaching, he proceeded to write a novel, Albert Angelo, about an impoverished architect forced to earn his living by supply teaching. But he grew increasingly dissatisfied with this deception, and the book concludes with a howl of authorial self-disgust: "Oh, fuck all this LYING!"

From then on, Johnson refused to "make things up" in his novels. His disgruntled publisher wanted to market them as autobiography and facetiously asked him, "Aren't you rather young to be writing your memoirs?" But Johnson was adamant: "The two terms 'novel' and 'fiction' are not synonymous," he wrote in 1966. "The novel is a form in the same sense that the sonnet is a form; within that form, one may write truth or fiction. I choose to write truth in the form of a novel."

It's hardly surprising that these words came back to me on Tuesday night, when the Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction was awarded and in her opening speech Janice Hadlow, the controller of BBC4, declared that "fact is the new fiction". At the very least, I believed that BS Johnson would have felt vindicated. But it also helped me to realise why these 40-year-old novels of his, written on a modernist principle of formal innovation which many critics complained was out of date even at the time, suddenly feel so fresh and contemporary.

Behind Hadlow's soundbite was, I think, an accurate recognition that fiction had better watch its back at the moment. There appears to be a growing - one might even call it BS Johnsonian - lack of public faith in the ability of "stories" to tell us anything meaningful about our lives. This may be because novelists are not doing their job properly; more likely, it's because non-fiction writers are doing their job so well. One of the striking features of the judges' televised discussion in the run-up to the prize announcement was the extent to which they discussed all six of the shortlisted books in emotional terms: essays on cities, works of history and biography were repeatedly praised for moving the reader to laughter or tears - just the kind of response that fiction is traditionally expected to provoke.

Johnson himself, for that matter, was a highly emotional writer. I first discovered him as a postgraduate student back in the mid-1980s, at a time when I was dutifully gritting my teeth and forcing my way through the novels of people such as Robbe-Grillet and Ann Quin. It was a shock - and a joy - to find that there existed a writer who shared their radical aesthetic but could also write page-turners, books which seemed unprecedentedly candid and self-revealing. I would troop around the Warwick University campus evangelising for this strange writer who cut holes in the pages of his novels and insisted that his publishers package them as unbound pages in a box, until I remember a friend saying to me, one day: "I think you'll grow out of BS Johnson."

She was right in the sense that nowadays I'm no longer so impressed by these quirky, attention-grabbing aspects of his work. But wrong in the sense that the urgency of his themes, and the passionate honesty with which he explored them, continues to inspire me.

And not just me, I should add. I began writing the biography feeling like a lone voice in the wilderness; but one of my most gratifying discoveries was that many other writers - of my generation and younger - were already well aware of Johnson, and just as enamoured as I was. Will Self, John Lanchester, Scarlett Thomas, Richard Beard and Alain de Botton have all written or spoken of their admiration for him. Hari Kunzru gave Zadie Smith a first edition of The Unfortunates (his legendary book-in-a-box) as her wedding present. How many other British novelists from the 1960s continue to excite their literary heirs as BS Johnson does?

So perhaps these will - finally - be the last words I write about him. It's time for readers, now, to begin the adventure of rediscovering this most challenging, unusual and exasperating of writers and men. After all, in Johnson's own (far from modest) opinion of himself, he will only be receiving his due. On the day before he committed suicide, in November 1973, he remarked to his agent, Diana Tyler: "I shall be much more famous after I'm dead." I for one rejoice to think that this melancholy prophecy seems to be coming true at last.

An extract from Albert Angelo (1964) They had had to walk on the third day, but by then they had arrived: to Fishguard it had been easy, a lucky straight hitch, and then the boat to Cork with a night's loving and sleeping in a cabin that was like their first home, transitory as it was; then walking through the coldmorning city, and three lifts to Tralee by way of Macroom and Killarney; and finally, on that third day, the walking north after a bus to Dingle.

They had had rain about three o'clock when they were walking along an unmetalled road parallel to the sea. There had been mountains like hooded Fathers rising to their south, and a sea like tarnished hammered pewter in Brandon Bay to their north ... Lead-underbellied clouds had come from the north-west, had cut off up to the haunches the purple mountains and had foreshortened the horizon. They had brought umbrellas, firstly as a gimmick for lifts, but then they had been glad to use them seriously.

They had decided that it would be as well to pitch their tent at the first place suitable, because of the set-in rain, rather than go on farther eastwards as they had at first intended. They had come down a path towards a lough and had turned inland along it: everywhere the land had been sodden and marshy, with peat digs here and there. They had walked about a mile alongside the lough without finding a large enough area of firm grass, drinking water from the bitter lough to ease unusual thirsts, before they had decided to turn back towards the sea. A stream had led out of the lough, down through striated rocks, and amongst these rocks they had found a small area of thick, close grass, green as spring, as unexpected as if it had been a hotel, and more welcome, where they had set their camp. When they were warm and comfortable they had realised that their love had come through its most severe trying yet: that miserable walk in the heavy rain with no knowledge of where they would that night sleep.

... They had spent six days at this place, which had no name on their maps: but they had called it Balgy, for no reason other than that it had come to them, Balgy. They had built a kitchen area protected by rocks, and dug a pit in which to bury their detritus, and had defined an area where they could comfortably and civilisedly defecate, and had found a thicket where they could collect wood for a fire.

Gneiss had been exposed in two great slabs at acute angles, the fault cut wider by the stream, the sides showing glacial striation. They had sketched the mountains, and had talked, had cooked and eaten enormous meals, and had never been as close. They had designed and drawn a house to be built for them over this stream, founded on the gneiss, inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright but more beautiful than his Falling Water, they had thought, and they had called it Above the Fault .

On the ninth day they had left their Balgy, regretfully, and had walked eastwards to Tralee, twenty miles in that one day, on that warm day, and with heavy packs: and this journey and its physical exhaustion had drawn them the closest they were ever to be, for its length. Well before they had reached London they had both known that they had passed the pitch of their loving.

· Like A Fiery Elephant: The Story of BS Johnson is published by Picador, £9.99 on July 1.

· An omnibus comprising three of BS Johnson's novels - Albert Angelo, Trawl and House Mother Normal - as well as The Unfortunates (the 'book in a box') and Christie Malry's Own Double-Entry is published by Picador, £14.99.

- Biography books

- Samuel Johnson prize 2005

- Samuel Johnson prize

- Awards and prizes

- Jonathan Coe

Most viewed

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 [OS 7 September] - 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer.The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography calls him "arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history".

Samuel Johnson (born September 18, 1709, Lichfield, Staffordshire, England—died December 13, 1784, London) was an English critic, biographer, essayist, poet, and lexicographer, regarded as one of the greatest figures of 18th-century life and letters. Johnson once characterized literary biographies as "mournful narratives," and he believed ...

Samuel Johnson (September 18, 1709—December 13, 1784) was an English writer, critic, and all-around literary celebrity in the 18th century. While his poetry and works of fiction—though certainly accomplished and well-received—are not generally regarded among the great works of his time, his contributions to the English language and the field of literary criticism are extremely notable.

The biography of Johnson written by his contemporary James Boswell is one of the most admired biographies of all time. James Boswell Summary. James Boswell was a friend and biographer of Samuel Johnson (Life of Johnson, 2 vol., 1791). The 20th-century publication of his journals proved him to be also one of the world's greatest diarists ...

November 19, 2023. Samuel Johnson, affectionately known as Dr. Johnson, was a prominent English writer who lived during the early 18th century. He was a legendary literary figure in his own lifetime who made lasting contributions as a poet, biographer, lexicographer, and one of the greatest critics in the history of English literature.

The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D., generally regarded as the greatest of English biographies, written by James Boswell and published in two volumes in 1791. Boswell, a 22-year-old lawyer from Scotland, first met the 53-year-old Samuel Johnson in 1763, and they were friends for the 21 remaining years of Johnson's life. From the beginning, using a self-invented system of shorthand, Boswell ...

Life of Samuel Johnson. The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (1791) by James Boswell is a biography of English writer Samuel Johnson. The work was from the beginning a critical and popular success, and represents a landmark in the development of the modern genre of biography. It is notable for its extensive reports of Johnson's conversation.

Samuel Johnson, the premier English literary figure of the mid and late 18th century, was a writer of exceptional range: a poet, a lexicographer, a translator, a journalist and essayist, a travel writer, a biographer, an editor, and a critic. His literary fame has traditionally—and properly—rested more on his prose than on his poetry. As a result, aside from his two verse satires (1738 ...

The Life of Samuel Johnson, regarded by many as the finest biography ever written, has given the world an unforgettable portrait of Samuel Johnson. Johnson was a prolific writer—a poet, a lexicographer, a biographer, a playwright, and an essayist—yet Boswell's biography focuses not on Johnson's works but on the personality and the ...

Samuel Johnson was born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, on 18 September 1709. His father was a bookseller. He was educated at Lichfield Grammar School and spent a brief period at Oxford University ...

Thanks to Boswell's monumental biography of Samuel Johnson, we remember Dr. Johnson today as a great wit and conversationalist, the rationalist epitome and the sage of the Enlightenment. He is more often quoted than read, his name invoked in party conversation on such diverse topics as marriage, sleep, deceit, mental concentration, and patriotism, to generally humorous effect. But in Johnson ...

Samuel Johnson Biography. Samuel Johnson (usually known as Dr Johnson) (18 September 1709- 13 December 1784) was an English author, poet, moralist and literary critic. One of Dr Johnson's greatest contributions was publishing, in 1747, The Dictionary of the English Language. "Mankind have a great aversion to intellectual labor; but even ...

Samuel Johnson was a famous 18th-century poet, lexicographer, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critique and biographer. He is noted for publishing a dictionary back in 1755, for which he was given an honorary doctorate by Dublin University in 1765. He would also be later known as Dr. Johnson because of the degree.

Samuel Johnson, often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography calls him "arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history".

Samuel Johnson. A Biography. Peter Martin. Paperback. ISBN 9780674057371. Publication date: 11/15/2010. Bewigged, muscular and for his day unusually tall, adorned in soiled, rumpled clothes, beset by involuntary tics, opinionated, powered in his conversation by a prodigious memory and intellect, Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) was in his life a ...

He called the author "this good and great man." The gathering came with a bonus: "A Monument More Durable than Brass," a Houghton exhibit that samples the library's 15,000-item Donald and Mary Hyde Collection of Dr. Samuel Johnson. Look for Johnson's earliest surviving letter, his earliest diaries (kept in Latin), rare manuscript ...

Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (September 7, 1709 - December 13, 1784), often referred to simply as Dr. Johnson, was an English poet, essayist, lexicographer, biographer, and iconic literary critic.Although his literary output is relatively meager—he wrote only one novel, one play, and only a small volume of poems—his intellectual breadth and contributions as a public man of letters were so ...

Samuel Johnson - Literary Critic, Poet, Lexicographer: Johnson is well remembered for his aphorisms, which contributed to his becoming one of the most frequently quoted of English writers. Many of these are recorded in Boswell's The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D., including his famous assertion "Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel" and his admonition "Clear your mind of cant."

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)—one of the greatest moralists, poets, biographers, critics, essayists, and correspondents of all time—so dominated literary and intellectual life in the last half of the 18th century that the era is frequently referred to as the "Age of Johnson.". As a conversationalist and writer he was so insightful and ...

Today's Google Doodle pays tribute to Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), English wit and author of the Dictionary of the English Language, on the 308th anniversary of his birth.

A detail of Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language (1755). The definition of "Oats" is often cited as evidence of Johnson's prejudice against Scots. A Dictionary of the English Language was published in two volumes in 1755, six years later than planned but remarkably quickly for so extensive an undertaking.

Jonathan Coe, whose biography of the author this week won the Samuel Johnson award, explains why he chose to focus on the largely forgotten writer Jonathan Coe Fri 17 Jun 2005 05.22 EDT

Samuel Johnson - Poet, Critic, Lexicographer: Johnson's last great work, Prefaces, Biographical and Critical, to the Works of the English Poets (conventionally known as The Lives of the Poets), was conceived modestly as short prefatory notices to an edition of English poetry. When Johnson was approached by some London booksellers in 1777 to write what he thought of as "little Lives, and ...