Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Cash flow management and its effect on firm performance: Empirical evidence on non-financial firms of China

Roles Investigation

Affiliation School of Accounting, Xijing University, Xi’an City, Shaanxi Province, People’s Republic of China

Affiliation Department of Economics and Management Sciences, NED University of Engineering & Technology, Karachi City, Pakistan

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Business and Economics, University of Almeria, Almería, Spain

- Fahmida Laghari,

- Farhan Ahmed,

- María de las Nieves López García

- Published: June 20, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135

- Reader Comments

The main purpose of this research is to investigate the impact of changes in cash flow measures and metrics on firm financial performance. The study uses generalized estimating equations (GEEs) methodology to analyze longitudinal data for sample of 20288 listed Chinese non-financial firms from the period 2018:q2-2020:q1. The main advantage of GEEs method over other estimation techniques is its ability to robustly estimate the variances of regression coefficients for data samples that display high correlation between repeated measurements. The findings of study show that the decline in cash flow measures and metrics bring significant positive improvements in the financial performance of firms. The empirical evidence suggests that performance improvement levers (i.e. cash flow measures and metrics) are more pronounced in low leverage firms, suggesting that changes in cash flow measures and metrics bring more positive changes in low leverage firms’ financial performance relatively to high leveraged firms. The results hold after mitigating endogeneity based on dynamic panel system generalized method of moments (GMM) and sensitivity analysis considering the robustness of main findings. The paper makes significant contribution to the literature related to cash flow management and working capital management. Since, this paper is among few to empirically study, how cash flow measures and metrics are related to firm performance from dynamic stand point especially from the context of Chinese non-financial firms.

Citation: Laghari F, Ahmed F, López García MdlN (2023) Cash flow management and its effect on firm performance: Empirical evidence on non-financial firms of China. PLoS ONE 18(6): e0287135. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135

Editor: Chenguel Mohamed Bechir, Universite de Kairouan, TUNISIA

Received: February 23, 2023; Accepted: May 31, 2023; Published: June 20, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Laghari et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data used in this study is taken from China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database.

Funding: Funded studies the grant has been awarded to the author María de la Nieves López García from the grant PID2021-127836NB-I00 (Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and FEDER). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Firms’ efficient cash flow management is significant tool to enhance financial performance [ 1 , 2 ]. Exercising proper management of cash flow is vital to the persistence of business [ 3 ]. Cash flow management is primarily concerned with identifying effective policies that balance customer satisfaction and service costs [ 4 ]. Firms manage efficiently of cash flows via working capital by balancing liquidity and profitability [ 5 – 7 ]. Working capital management, which is the main source of firm cash flow has significant importance in the context of China, where firms are restricted with limited access to external capital markets. In order to fulfill their cash flow needs firms heavily depend on internal funds, short-term bank loans, and trade credit in order to finance their undertakings [ 5 ]. For such firms’ working capital plays the role of additional source of finance. Consistent with this view, KPMG China [ 8 ] declared that effective management of working capital has played a vital role to alleviate the effects of recent financial crisis. Additionally, in recent times the remarkable growth of China roots to Chinese private firms’ effective management of working capital in general and their accounts receivables in particular [ 9 ]. Therefore, efficient management of working capital is an avenue that highly influence firm profitability [ 10 – 12 ], liquidity [ 7 , 13 ], and value. Since corporates cash flow management policies settle working capital by account receivables, inventories and accounts payables. Hence, existing theories of working capital management support the view that by cash flow manipulation firms can enhance liquidity and competitive positioning [ 6 , 14 , 15 ]. Therefore, firms manipulate cash flows through its measures, as by way speedy recovery of accounts receivables, reducing inventories, and delaying accounts payables [ 16 ]. Hence, the first research question is whether changes in cash flow measures are the tools that could bring positive changes in firm financial performance.

From the accounting perspective, liquidity management evaluates firm’s competence to cover obligations with cash flows [ 17 , 18 ], as uncertainty about cash flow increases the risk of collapse in most regions, industries, and other subsamples [ 19 ]. There are two extents: static or dynamic views, through which corporate liquidity can be inspected. The balance sheet data at some given point of time is a basis for static view. This comprises of traditional ratios such as, current ratios and quick ratios, in order to evaluate firms ability to fulfill its obligations through assets liquidation [ 20 ]. The static approach is commonly used to measure corporate liquidity, however, authors also declare that financial ratio’s static nature put off their capability to effectively measure liquidity [ 21 , 22 ]. The dynamic view is to be utilized to capture the firms’ ongoing liquidity from firm operations [ 16 , 21 ]. Therefore as a dynamic measure, the cash conversion cycle (CCC) is used by authors to measure liquidity in empirical studies of corporate performance [ 23 ]. For instance; Zeidan and Shapir [ 24 ] and Amponsah-Kwatiah and Asiamah [ 25 ] find that reducing the CCC by not affecting the sales and operating margin increases share price, profits and free cash flow to equity. Accordingly, Farris and Hutchison [ 20 ] find that shorter cash conversion cycle leads to higher present value of net cash flows generated by asset which contribute to higher firm value. Moreover, Kroes and Manikas [ 1 ] used operating cash cycle as a measure for cash flow metrics, which combines accounts receivables and firm inventory. As explained by Churchill and Mullins [ 26 ] that all other things being constant shorter the operating cash cycle faster the company can reassign its cash and can have growth from its internal resources. The second research question therefore is that whether changes in cash flow metrics bring positive improvements in firm financial performance.

Study uses CSMAR database of Chinese listed companies from the period 2018:q2-2020:q1. In the study, measure of firm performance is Tobin’s-q. Study uses three cash flow measures; accounts receivables turning days, inventory turning days and accounts payable turning days, and cash conversion cycle and operating cash cycle as measure for cash flow metrics. Consistent with the prediction, study finds that changes in cash flow measures and metrics bring positive improvements in firm financial performance. In particular decline in cash flow measures (ARTD, ITD, and APTD) to one unit would increase firm performance approximately 6.8%, 0.03%, and 7.2%; respectively. Additionally, one unit decline in cash conversion cycle would increase firm performance approximately 3.8%. Furthermore, study uses GMM estimator to alleviate the endogeneity and observe that the main estimation results still hold. In addition, study also employs a sensitivity analysis specifications to better isolate the impact of changes in cash flow measures and metrics on firm financial performance in previous period and observe that negative association is still sustained.

The sizable number of listed firms in China enable the study to divide sample into two subsamples: firms in high leverage industry and firms in low leverage industry. The study repeats the test on these two subsamples. Significant and negative association between cash flow measures, metrics and firm financial performance is still sustained. Moreover, the results of differential coefficients across two sub samples via seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) systems indicated that cash flow measures and metrics are more pronounced in low debt industries.

The paper makes significant contribution to the literature related to cash flow management and working capital management. First, this paper is among few to empirically study, how cash flow measures and metrics are related to firm performance from dynamic stand point especially in the Chinese context. The study sheds light on the role of cash flow management in improving the firm’s financial performance. Second, extant researches on cash flow management focus on the manufacturing industries. Unlike others this paper investigates the relation between cash flow measures, metrics and firm performance in the context of whole Chinese market, which is essential to know how these performance levers contribute to financial performance of other industries also. Third, results highlight the role of cash flow management in improving financial performance by taking firms’ leverage into consideration and declare that low leveraged industries are better off in terms of influence of changes in cash flow measures and metrics on firm performance. Fourth, the present paper uses generalized estimating equations (GEEs) Zeger and Liang [ 27 ] technique which is robust to estimate variances of regression coefficients for data samples that display high correlation between repeated measurements. Finally, to ensure robustness of findings the study uses sensitivity analysis, and in order to control for the potential issue of endogeneity the present study also uses generalized method of moments (GMM) following statistical procedures of Arellano and Bover [ 28 ] and Blundell and Bond [ 29 ].

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section two discusses the role of cash flow management in China. Section three discusses the relevant literature, theoretical framework and development of hypotheses. Section four presents the data and variables of the study. Section five reports the methodology, empirical results and discussions. Section six concludes the paper.

Cash flow management in China

The economy of China has undergone a massive economic growth rates followed by high rates of fixed investment in the past three decades [ 5 , 30 ]. This growth miracle is outcome of highly productive firms and their ability to accrue significant cash flows [ 31 ], despite inadequate financial system. Moreover, although Chinese economy has seen fast growth and development in the past two decades but still the legal environment in China cannot be regarded as conducive [ 32 , 33 ]. As, in the credit market of China government plays a decisive role in credit distribution [ 34 , 35 ], and mostly the credit is granted to companies owned by state or closely held firms [ 34 , 36 ]. The Chinese firms have restricted admittance to the long-standing funds marketplace [ 37 ], therefore, companies held private or non-SOE find difficulty to access credit from financial market relatively to state owned firms. Although by the 1998 leading Chinese banks were authorized to lend credit to privately held firms but still these firms face troublesome to get external finance comparatively to state owned firms [ 32 ]. The prior literature also indorses this and states that with the presence of regulatory discrimination amid privately held and state owned firms, the privately held firms to the extent are often the subject of state predation [ 38 , 39 ].

Given country’s poor financial system, firms in China have managed their growth rates from their internal resources. Working capital management from where firms manage cash flows is the source of financing of the growth by Chinese firms. Accordingly, Ding et al . [ 5 ] mentioned that in their sample of Chinese firms about 66.6% dataset were characterized by a large average ratio of working capital to fixed capital, as it is a source and use of short term credit. Additionally, Dewing [ 40 ] termed working capital as one of the vital elements of the firm along with fixed capital. Moreover, Ding et al . [ 5 ] conclude that in the presence of financial constraints and cash flow shocks still Chinese firms can manage high fixed investment levels which correspond more to working capital than fixed capital. They further state that this all roots to the efficient management of working capital that Chinese firms use in order to mitigate liquidity constraints.

Literature review, theoretical background and hypothesis development

Literature review and theoretical background.

Corporate finance theory states that the main goal of a corporation is to maximize shareholder wealth [ 41 ]. Neoclassical capital theory is based on the proposition put forward by Irving Fisher [ 42 ] that individual consumption decisions can be separated from investment decisions. Fisher’s separation theorem holds true in perfect capital markets, where companies and investors can lend and borrow on the same terms without incurring transaction costs. In such a world, the choice to change income streams by lending and borrowing to meet preferences of consumption means that investors rank income streams according to their present value. Therefore, the value of the company is maximized by choosing the set of investments that generate the largest net present value over returns. When the company pays cash dividends with capital reserves, cash dividends can be maintained at a certain level, and when the ratio of capital reserves to cash dividends is high, accrual income management is low [ 43 ]. Since Gitman’s [ 44 ] seminal work, in which he introduced the concept of cash circulation as a means of managing corporate working capital and its impact on firm liquidity. Richards and Laughlin [ 16 ] then transformed the cash cycle concept into the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) theory for analyzing the working capital management efficiency of firms. CCC theory holds that effective working capital management (i.e., shorter cash conversion cycles) will increase a company’s liquidity, all else being equal. Signal theory can illustrate how a company can provide excellent signals to users of financial and non-financial statements [ 45 ]. In addition, this theory can also be used as a reference for investors to see how good or bad a company is as an investment fund. This theory explains the relationship between working capital turnover and profitability.

The trade-off theory in capital structure is a balance of benefits and sacrifices that may occur due to the use of debt [ 46 ]. The higher the amount a company spends on financing its debt, the greater the risk that they will face financial hardship due to excessive fixed interest payments to debt holders each year and uncertain net income. Higher cash flow uncertainty leads to an increased risk of business collapse [ 19 ]. Companies with high levels of leverage should keep their liquid assets high, as leverage increases the likelihood of financial distress. This theory is used to explain the relationship between leverage and profitability. Pecking order theory explains that companies with high liquidity levels will use more debt funds than companies with low liquidity levels [ 47 ]. Liquidity measures a company’s ability to meet its cash needs to pay short-term debts and fund day-to-day operations as working capital. The better the company’s current ratio, the more the company will gain the trust of creditors so that creditors will not hesitate to lend the company funds used to increase capital, which will benefit the company.

Prevailing working capital management theories argue that firms can improve their competitive position by manipulating cash flow to improve liquidity [ 14 , 15 , 20 , 48 – 50 ]. In addition, the company’s ability to convert materials into cash from sales reflects the company’s ability to effectively generate returns from investments [ 51 ]. It’s better to combine investment spending with cash flow from ongoing operations than to measure and report both discretely [ 52 ]. Three factors directly affect the company’s access to cash: (i) the company’s inability to obtain cash receivables while waiting for the customer to pay for the delivered goods; (ii) the company is unable to obtain cash receivables; (iii) the company is unable to obtain cash receivables. (ii) Cash invested in goods is tied up and unavailable and the goods are inventoried; and (iii) cash may be made to the company if it chooses to delay payment to suppliers for goods or services provided [ 16 ]. While a company’s cash payments and collections are typically managed by the company’s finance department, the three factors that affect cash flow are primarily manipulated by operational decisions [ 53 ].

In the literature, the prevailing view is that the presence of liquidity is not always good for the company and its performance, because sometimes liquidity can be overinvested. Since emerging markets are characterized by imperfect markets, companies maintain internal resources in the form of liquidity to meet their obligations. As in emerging markets, financial markets are inefficient in allocating resources and releasing financial constraints, resulting in underinvestment by financially constrained companies [ 54 ]. In addition, access to capital markets, external financing costs, and availability of internal financing are financial factors on which a company’s investments rely [ 55 ]. Alternatively, the pecking order theory [ 56 ] argues that due to information asymmetry, companies adopt a hierarchical order of financing preferences, so internal financing takes precedence over external financing. A study by Zimon and Tarighi [ 7 ] argue that businesses must use the right working capital strategy to achieve sustainable growth as it optimizes operating costs and maintains financial liquidity. Moreover, asset acquirements affect a company’s output and performance [ 57 ].

The existing literature provides different evidence of the impact of working capital management on firm performance. A study by Sharma and Kumar [ 58 ] examine the relationship between working capital management and corporate performance in Indian firms. Considering a sample of 263 listed companies during the period 2000–2008, they found that CCC had a positive impact on ROA. Similarly, of the 52 Jordanian listed companies in the period 2000–2008, Abuzayed [ 11 ] found a positive impact of CCC on total operating profit and Tobin’s-Q. Similar findings have been reported by companies in China [ 59 ], the Czech Republic [ 60 ], Ghana [ 25 ], Indonesia [ 6 ], Spain [ 61 ], and Visegrad Group countries [ 62 ]. In contrast, few studies reported an inverse correlation between CCC and firm performance in India [ 63 ], Malaysia [ 2 ], and Vietnam [ 64 ]. A negative correlation indicates that a higher CCC leads to lower company performance. A study by Afrifa et al. [ 65 ] did not find any significant relationship between CCC and firm performance. The findings of the relationship between NWC and company performance are not much different from CCC. Companies in European countries [ 66 ], and the United Kingdom [ 67 ] reported positive correlations, and those in Poland reported negative correlations [ 68 ]. Although previous operations management studies have explored the relationship between working capital and firm performance, the results of these studies remain inconclusive, and the study has found positive, curved, and even insignificant relationships. This is mainly since accidental factors make this relationship both complex and special. Therefore, to enhance the beneficial impact of working capital and cash flow on corporate performance, companies must make appropriate investments to promote more objective, informed, and business-specific working capital and cash flow management choices [ 69 ]. Collectively, these mixed pieces of evidence provide sufficient motivation for this study to develop hypotheses based on positive and negative relationships.

The cash flow measures and firm financial performance

The firms’ trade where merchandise sold on credit instead of calling for instantaneous cash imbursement, such transaction generate accounts receivables [ 70 ]. Accounts receivable directly affect the liquidity of the enterprise, and thus the efficiency of the enterprise [ 71 ]. From the stands of a seller, the investment in accounts receivables is a substantial component in the firm’s balance sheet. Firms’ progressive approach towards significant investment in accounts receivables with respect to choice of policies for credit management contributes significantly to enhance firm value [ 72 ]. Firms can utilize cash received from customers by investing in activities which contribute to enhance sales [ 1 ]. Firms can improve liquidity position with capability to collect overheads from customers for supplied goods and services rendered in a timely manner [ 17 ]. However, credit sales is instrumental to increase sales opportunities for firms but may also increase collection risk which can lead to cash flow stresses even to healthy sales growth companies [ 73 ]. Firms offer sales discounts which may not increase sales but may increase payments by customers and improve firms’ cash flow, reduce uncertainty of future cash flows, reduce risk and required rate of return [ 74 ].

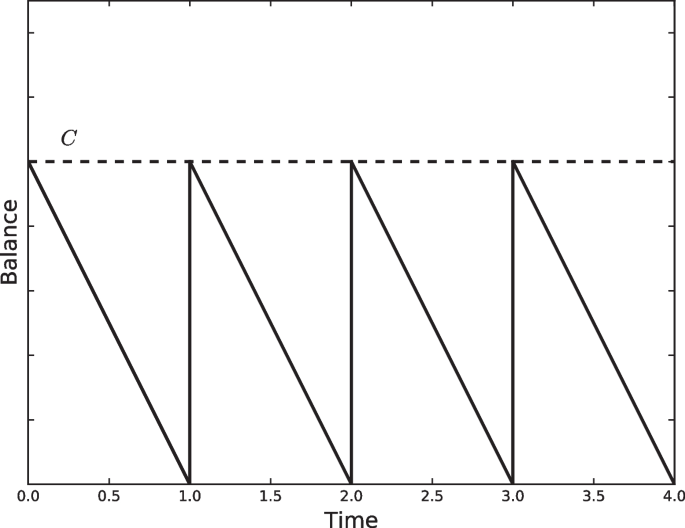

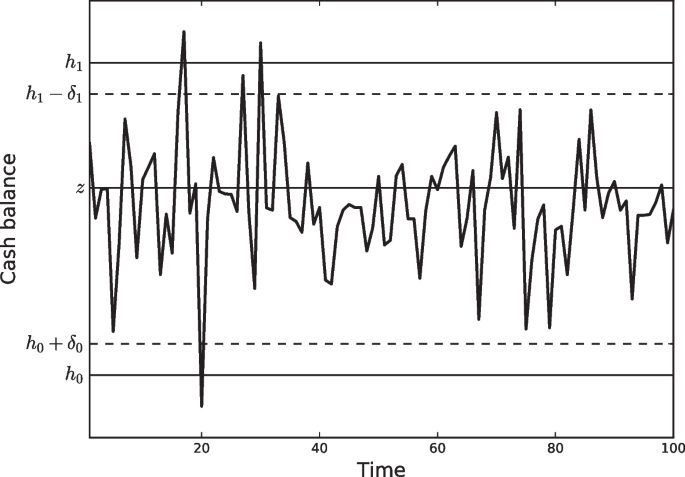

Literature suggests that firm performance increases with shorter period of day’s sales outstanding [ 15 , 20 , 26 ]. Accordingly, Deloof [ 75 ] by working on Belgians firms find negative relationship between number of days accounts receivables and gross operating income. However, models of trade credit (such as; Emery, [ 21 ]) endorse that higher profits also lead to more accounts receivables as firms with higher profits are rich in cash to lend to customers. In a study by García-Teruel and Martinez- Solano [ 76 ] suggest that managers of firms with fewer external financial resources available generally dependent on short term finance and particularly on trade credit that can create value by shortening the days sales outstanding. Furthermore, Gill et al . [ 10 ] declare that firm can create value and increase profitability by reducing the credit period given to customers. Kroes and Manikas [ 1 ] analyzed manufacturing firms and suggested that decline in days of sales outstanding relates to improvements in firm financial performance and persists to several quarters. According to Moran [ 77 ] suppliers happily offer reasonable sales discounts for early payments which improve their cash flow position, locks the receivables, remove the bad debt risk at early stage, and reduce their day’s sales outstanding significantly which ultimately improve their working capital position. Fig 1 depicts this relationship. In consistent with discussion the following hypothesis is proposed:

- H1a : A decrease (increase) in the duration of accounts receivables turning days increases (decreases) firm financial performance.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135.g001

The research has mixed views whether reduction in inventory is beneficial to firm performance or increase in inventory leads to increased performance. Despite high cash flow, inventory level management has been neglected [ 78 ]. In this regard literature has evidenced three themes of relationships: positive relationship, negative relationship or no relationship, and inclusion of moderators and mediators to the relationship of number of day’s inventory and firm performance [ 79 ]. However, the inventory management revolutionized after the launch of lean system with familiarizing just-in-time inventory philosophy by Japanese companies [ 80 , 81 ]. Afterwards, research related to inventory management evidenced that firms which adopted lean system not only improved customer satisfaction but also attained greater level of asset employment that ultimately leads to higher organizational growth, profitability, and market share [ 82 , 83 ]. Moreover, in a JIT context firms experience positive effects on organizational performance due to reduced inventory, and reduction in inventory significantly improves three performance measures such as: profits, firms return on sales, and return on investments [ 84 ]. Additionally, Fullerton and McWatters [ 85 ] found positive influence of reduced inventory on organizational performance which corresponds to JIT context.

However, generally literature considers that better inventory performance such as: higher inventory turns or decreased level of inventory is normally attributed to better firm financial performance [ 86 ]. Moreover, it is a mutual consent by researchers that high level of inventory also signifies demand and supply misalliance and often related to poor operational performance [ 87 , 88 ]. In a study by Elsayed and Wahba [ 79 ] indicated that there is influence of organizational life cycle on the relationship of inventory and organizational performance. Their results indicated that at initial stage though ratio of inventory to sales negatively affects organizational performance, but it put forth significant and positive coefficient on organizational performance at the revival phase or rapid growth phase. Additionally, literature has documented negative influence of reduced inventory on performance. In a study by Obermaier and Donhauser [ 89 ] evidenced that lowest level of inventory leads to poor organizational performance and suggest that moving towards zero inventory case is not always favorable. Fig 1 depicts this relationship. Accordingly the hypothesis is proposed as follows:

- H1b : A decrease (increase) in the duration of inventory turning days increases (decreases) firm financial performance.

According to Deloof [ 75 ] payment delays to suppliers are beneficial to assess the quality of product bought, and can serve as a low-cost and flexible basis of financing for the firm. On the contrary, delaying payments to suppliers may also prove to be costly affair if firm misses the discount for early payments offered [ 90 ], hence firms by reducing days payable outstanding (DPO) likely to enhance firm financial performance [ 76 ]. In line with this, Soenen [ 22 ] states that firms try to collect cash inflows as quickly as possible and delay outflows to possible length. Payment delays enable firms to hold cash for longer duration which ultimately increases firms’ liquidity [ 50 ]. As discussed by Farris and Hutchsion [ 20 ] that firms can improve cash to cash cycle by extending the average accounts payable along with inventory and get interest free financing. A study by Sandoval et al . [ 91 ] speculate that investors are more sensitive to accruals of long-term operating assets than to accruals of long-term operating liabilities because the former is more associated with recurring profits than the latter. Moreover, Fawcett et al . [ 92 ] indorsed that by extending the duration of accounts payable cycle companies can improve their cash to cash cycle. However, longer payment cycles not only harm relationship with suppliers, but may also lead to lower level of services from suppliers [ 93 ].

As discussed by Raghavan and Mishra [ 94 ] firms may be reluctant to produce or order at optimal point followed by cash restraints for fast growing firms where money plays the role of catalyst when demand is significantly high but firms are financially restricted to order less and this situation may mark the harmful effects over the performance of whole supply chain at least on temporary basis until restored. Hence, this situation is favoring that firms encourage and motivate their customers for quicker payments in order to increase cash to cash cycles [ 92 ]. Fig 1 depicts this relationship. Accordingly based on discussion hypothesis is proposed as follows:

- H1c : A decrease (increase) in the duration of accounts payable turning days’ increases (decreases) firm financial performance.

The cash flow metrics and firm financial performance

As shown by Richards and Laughlin [ 16 ] that firms should collect inflows as quickly as possible and postpone cash outflows as long as possible which is a general view based on the concepts of operating cash cycle (OCC) and cash conversion cycle (CCC). This shows that firms by reducing CCC cycle can make internal operation more efficient that ensures the availability of net cash flows, which in turn depicts a more liquid situation of the firm, or vice versa [ 25 ]. They further said that cash conversion cycle (CCC) is based on accrual accounting and linked to firm valuation. Baños-Caballero et al . [ 95 ] suggested that however, higher level of CCC increases firm sales and ultimately profitability, but may have opportunity cost because firms must forgo other potential investments in order to maintain that level. On the contrary, longer duration of CCC may hinder firms to be profitable because this is how firms’ duration of average accounts receivables and inventory turnover increase which may lead firms towards decline in profitability [ 96 ]. Therefore, cash conversion cycle (CCC) can be reduced by shortening accounts receivables period and inventory turnover with prolonged supplier credit terms which ultimately enable firms to experience higher profitability [ 97 , 98 ]. A shorter duration of CCC helps managers to reduce some unproductive assets’ holdings such as; marketable securities and cash [ 23 ]. Because with low level of CCC firms can conserve the debt capacity of firm which enable to borrow less short term assets in order to fulfill liquidity. Therefore, shorter CCC is beneficial for firms that not only corresponds to higher present value of net cash flows from firm assets but also corresponds to better firm performance [ 60 , 62 ].

Operating cash cycle is a time duration where firm’s cash is engaged in working capital prior cash recovery when customers make payments for sold goods and services rendered [ 16 , 26 ]. Literature endorses that shorter the operating cash cycle better the firm liquidity and financial performance because companies can quickly reassign cash and cultivate from internal sources [ 16 ]. In a study by Kroes and Manikas [ 1 ] find that there is significant negative relationship between changes in OCC with changes in firm financial performance. They further suggested that OCC can be taken by managers as a metric to monitor firm performance and can be used as lever to manipulate in order to improve firm performance. A study by Farshadfar and Monem [ 99 ] also found that when the company’s operating cash cycle is shorter and the company is small, the cash flow component improves earnings forecasting power better than the accrual component. Moreover, Nobanee and Al Hajjar [ 100 ] recommend the optimum operating cycle as a more accurate and complete working capital management measure to maximize the company’s sales, profitability, and market value. Fig 1 depicts this relationship. Hence, based on above discussion the proposed hypotheses are:

- H2a : A decrease (increase) in cash conversion cycle increases (decreases) firm financial performance.

- H2b : A decrease (increase) in operating cash cycle increases (decreases) firm financial performance.

Data and variables

Samples selection.

The data used in this study is taken from China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database. The study includes quarterly panel data of non-financial firms with A-shares listed on Shanghai Stock Exchange (SHSE) and Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE). The data comprises on eight quarters ranging from 2018:q2-2020:q1, and four lag effects are included that make data up to twelve quarters. The use of quarterly data ensures greater granularity in the findings of the study as prior studies have mainly used annual data, therefore, this study uses two years plus one year of lagged data which offers exclusively a robust sample period that is instrumental to effective inference [ 1 ]. The main benefit of this method of examining quarterly changes within a company is that the company cannot have any missing data items throughout the sample period. Because any missing data will lead to design errors and imbalance panel data. Therefore, this problem led to now selection of a 12-quarter observation frame (two years plus one year of lagging data) because it delivers a reliable sample period from which effective conclusions can be prepared. Moreover, the data is further refined and maintained from unobserved factors, unbalanced panels, and calculation biases. Moreover, deleted firm-year observation with missing values; excluded all financial firms; as their operating, investing, and financing activities are different from non-final firms [ 75 , 101 ], eliminated firms with traded period less than one year, and excluded all firms with less than zero equity. The data is further winsorized up to one percent tail in order to mitigate potential influence of outliers [ 76 ]. Additionally, the firms’ data with negative values for instance; sales and fixed assets is also removed [ 67 , 101 ]. The final sample left with balanced panel of 20288 firm year observations consists of 2536 groups. The change (Δ) in all dependent and independent variables of the study sample represents variable period t measured as difference between value at the end of current quarter and value of the variable at the end of prior quarter divided by value of the variable at the end of prior quarter.

Dependent variable

The firm’s financial performance is dependent variable in the study and is measured through Tobin’s-q. Tobin’s-q is the ratio of firm’s market value to its assets replacement value and it is widely used indictor for firm performance [ 1 , 102 – 105 ]. Tobin’s-q diminishes most of the shortcomings inherent in accounting profitability ratios as accounting practices influence accounting profit ratios and valuation of capital market applicably integrates firm risk and diminishes any distortion presented by tax laws and accounting settlements [ 106 ]. Moreover, this variable has preference over other accounting measures (such as; ROA) as an indicator of relative firm performance [ 107 ].

Independent variables

Based on established literature [ 1 , 5 , 12 , 75 , 76 ] this study has used three cash flow measures and two composite metrics as independent variables. Each one of them is discussed below.

Accounts receivables turning days (ARTD).

The increasing days of sales outstanding specifies that firm is not handling its working capital efficiently, because it takes longer duration to collect its payments, which signifies that firm may be short of cash to finance its short term obligations due to the longer duration of cash cycle [ 5 ].

Inventory turning days (ITD).

A higher ratio of inventory turnover is a good sign for firm as it signifies that firm is not having too many products in idle condition on shelves [ 5 ].

Accounts payable turning days (APTD).

A firm with higher days of payable outstanding ratio shows that it takes longer duration to make payments to suppliers which is a sign of poor efficiency of working capital, however longer duration of DPO also signifies that company has good terms with suppliers which is also beneficial [ 5 ].

Cash conversion cycle (CCC).

It is generally considered that lower the CCC cycle better the firm efficiency and able to accomplish its working capital [ 5 ]. Additionally, longer duration of CCC shows more time duration between cash outlay and recovery of cash [ 76 ].

Operating cash cycle does not take into account the payables, and hence comprises of days where cash is detained as inventory prior receipts of payments from customer [ 1 ]. Besides, generally it is considered that firm having shorter OCC is with better liquidity and performance [ 26 ].

Control variables

This study uses firm size and return on assets as control variables. Following Deloof [ 75 ] the study uses firm size by taking natural logarithm of quarterly sales. The firm size has significant impact on market value of firms [ 103 , 108 ]. Study uses quarterly sales instead of total assets as measure for firm size to avoid the potential multicollinearity problem because total asset is denominator for the dependent variable [ 1 ]. Following Baños-Caballero et al . [ 95 ] study controls for return on asset (ROA) which is accounting measure of firms. Return on assets (ROA) is a ratio of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) divided by total assets [ 109 ].

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of variables of the study. The mean and median value of ARTD is 92.89 and 73.14, respectively. On average, the firms in our sample have relatively higher median value of days of sales outstanding than evidence of Ding et al . [ 5 ], which shows that Chinese firms take longer to collect their payments from customers. The mean and median value of APTD is 105 and 82.25, respectively. The mean and median value of ITD is 166.18 and 107.13, respectively. On average it shows relatively high inventory turnover in our sample firms which signifies that Chinese firms are quite efficient in inventory management and products are not sitting idle in shelves. The mean and median value of CCC is 150.62 and 115.30, respectively. On average the CCC of Chinese firms is relatively high. However, in a study by Hill et al . [ 101 ] indicated that higher CCC also signifies higher firm profitability. The mean and median value of OCC is 250.71 and 206.44, respectively. The firm performance (Tobins-q) has a mean and median value of 2.86 and 2.27. The ROA shows mean and median value of 2.46 and 1.67, respectively. On average the size of Chinese firms is 20.79 with median value of 20.71.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135.t001

The Table 2 reports results for correlation matrix. The correlation coefficient between Tobin’s-Q and CCC is significant and negative at 1 percent level which is consistent to the findings of Afrifa [ 67 ]. The correlation between all the measures of cash flows and ROA is significant and negative at 1 percent, consistent with the results of Deloof [ 75 ]. Moreover the correlation between ROA and CCC is also significant and negative at 1 percent, similar evidences find by García-Teruel and Martinez-Solano [ 76 ] for the sample of Spanish firms. Furthermore, the correlation coefficients among all the variables are significantly lower than 0.80 indicating no sign of multicollinearity [ 110 ]. The formal test of variance inflation factor (VIF) for all the independent variables of study were examined to check if there is presence of multicollinearity. The variance inflation factor (VIF) also indicated no multicollinearity among analysis variables with all values below the threshold level of 10 proposed by Field [ 110 ], which shows that multicollinearity may not be the case and data is suitable for further analysis.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135.t002

Methodology, empirical analysis and discussion

Effect of cash flow measures on firm financial performance.

Where ΔY it represents Tobin’s-q for industry i and time t. The ΔX 1it is accounts receivable turning days (ΔARTD), and ΔX 1it-1 to ΔX 1it-4 are lags for ΔARTD. The ΔX 2it is inventory turning days (ΔITD), and ΔX 2it-1 to ΔX 2it-4 are lags for ΔITD. The ΔX 3it is accounts payable turning days (ΔAPTD), and ΔX 3it-1 to ΔX 3it-4 are lags for ΔAPTD. The CONTROLS it represent control variables; Size and ROA. The U it is probabilistic term. Study included four lag effects in Eq 6 for cash flow measures to examine how long the impact of changes in cash flow measures on changes in firm performance persists.

Table 3 provides detailed results of GEEs model’s parameters estimation analysis. The dependent variable is firm performance (Tobin’s-q) in all the models columns 2 through 4. H1a , H1b , and H1c posits that changes in measures of cash flow (ΔARTD, ΔITD, and ΔAPTD) changes firm financial performance. The coefficient of accounts receivable turning days (ΔARTD) in model 1 is -0.0068297, which is statistically significant at 0.1% confidence level in the current quarter. It is consistent with the study’s argument that decline in firms’ days of accounts receivables increases firm financial performance. Similar evidences were found by Shin and Soenen [ 13 ], Wilner [ 114 ], Deloof [ 75 ], and Kroes and Manikas [ 1 ]. According to Deloof [ 75 ] the negative relationship between days sales outstanding and firm performance suggests that managers can create value for their shareholders by reducing number of day’s accounts receivables to a reasonable minimum.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135.t003

The coefficient of inventory turning days (ΔITD) in model 1 is -0.0003014, which is statistically significant at 0.1% confidence level in the current quarter. These results are consistent with the argument given in hypothesis H1b . Significant number of studies conclude that low inventory period increases liquidity and firm performance [ 75 , 86 , 115 , 116 ]. Moreover, this finding is consistent with literature as firms sound inventory position exhibits better operational and financial performance [ 117 , 118 ].

The coefficient of accounts payable turning days (ΔAPTD) in model 1 is -0.0717425, which is statistically significant at 0.1% confidence level in the current quarter. These results are consistent with present study’s argument that decline in accounts payable turning days brings positive improvements in firm performance. The findings of results for APTD present strong evidence that when companies reduce their APTD by taking advantage of early discounts payment from suppliers, firms may have a persistent duration of perpetual firm financial performance improvement. As suggested by Moran [ 77 ] that firms may be more beneficial by taking advantage of early payment discounts than prolonging the cycle because of reduction in purchase price of components and materials by them.

Next, study estimated Eq 6 by dividing the sample into two subsamples based on firm leverage level, which is measured by firms’ debt to assets ratio. The high leverage (low leverage) contains firms in industries where their debt to assets ratio is greater (smaller) than the median value. Model 2 and 3 obtain similar patterns when applied on Eq (6) for high and low leveraged firms. The findings of results for high leverage and low leverage firms still hold as of full sample firms and strongly support hypotheses H1a , H1b , and H1c . Conclusively, the findings of results imply that reduction in three cash flow measures (ARTD, ITD, and APTD) relate to significant positive improvements in financial performance of firms at current quarter.

Effect of cash flow metrics on firm financial performance

Where ΔY it represents Tobin’s-q for industry i and time t. The ΔX it is ΔCCC and from ΔX 1it-1 to ΔX 1it-4 are lags for ΔCCC. The ΔX 2it is OCC and from ΔX 2it-1 to ΔX 2it-4 are lags for ΔOCC. The CONTROLS it shows the control variables; Size and ROA. The U it is probabilistic term. Study includes four lag effects in Eq 7 for cash flow metrics to examine how long the impact of changes in CCC and OCC on changes in firm performance persists.

Table 4 represents results for cash flow metrics (CCC and OCC). H2a and H2b predict that changes in ΔCCC and ΔOCC bring positive changes in the firm financial performance. The coefficient for the cash conversion cycle (ΔCCC) is -0.0382176, which is statistically significant at a 5% confidence level in the current quarter (as shown in Table 4 column 2).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135.t004

Next, the study estimated Eq 7 by dividing the sample into two subsamples based on firm leverage level which is measured by firms’ debt to assets ratio. The results in Table 4 Column 3 posit findings for highly leveraged firms. The coefficient for ΔCCC is -0.4038345, which is statistically significant at a 1% confidence level in the current quarter, as shown in Table 4 Column 3. The coefficient for ΔOCC is -0.0572725, which is statistically significant at a 1% confidence level in the current quarter, as shown in Table 4 Column 3. The coefficient for ΔCCC is -0.027272, which is statistically significant at a 0.1% confidence level, as shown in Table 4 column 4 for low-leverage firms at the current quarter.

As predicted by the hypothesis H2a ; the findings of results also show significant negative association of CCC with firm financial performance at current quarter for full sample firms, high leveraged firms, and low leveraged firms. These evidences of results are consistent with existing literature and show that decline in cash conversion cycle brings positive improvements in firm financial performance [ 13 , 23 , 75 , 76 , 96 , 97 , 119 ]. A study by Zeidan and Shapir [ 24 ] finds that reducing the CCC by not affecting the sales and operating margin increases the prices of shares, profits, and free cash flow to equity. Moreover, Prior research view that careful handling of the cash conversion cycle leads firms to significantly higher returns [ 13 , 23 , 75 , 76 , 97 ]. This outcome is consistent with the research by Simon et al. [ 120 ], Soukhakian and Khodakarami [ 121 ], Basyith et al. [ 6 ], Yousaf et al. [ 60 ], and Bashir and Regupathi [ 2 ]. The findings of the results show a significant negative association of OCC with firm financial performance in the current quarter for highly leveraged firms. The findings suggest that change in OCC led to changes in corporate performance provides significant support to the use of OCC as an indicator for managers to monitor performance and as a lever to manipulate to improve the corporate financial performance. The findings show that OCC in the current quarter posits a significant negative relationship with firm financial performance for highly leveraged firms. This evidence is consistent with the empirical findings of Churchill and Mullins [ 26 ].

Difference of coefficients across high leverage and low leverage firms

In addition, in the next section the present study analyzed the difference of coefficients across two groups by dividing sample into two subsamples, high leveraged and low leveraged firms based on their total debt to total assets ratios. In order to check the difference of coefficients across two groups study applied seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) system on Eqs ( 6 ) and ( 7 ) to better isolate the effect of cash flow measures and metrics on firm financial performance. The study computed standard errors for differenced coefficients via the seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) system that combines two groups.

The Table 5 reports results for differential impact of cash flow measures and metrics on firm performance across high leverage and low leverage industries. The study finds that the estimated coefficients for differences are positive and statistically significant. These findings of results imply that low leveraged industries are better off in terms of changes in cash flow measures and metrics that bring more positive changes in low debt industries financial performance. Since, low cash conversion cycle (CCC) conserves the debt capacity of the firm as in this situation firms need less short term borrowing to provide liquidity [ 97 ]. Therefore, lower cash conversion cycle (CCC) lessens the requirement for lines of credit and contributes to the firms’ debt capacity [ 23 ]. Due to high financial distress and higher likelihood of bankruptcy high leverage firms are more bounded by financial constraints which may hinder them to take valuable investments and, thus, harm their profitability [ 122 ]. This also suggests that firms with low leverage are high value firms and maintain lower duration of cash conversion cycle (CCC) at low levels that counts to higher profitability which ultimately leads to higher retained earnings and reduce the need for debt.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135.t005

Test of endogeneity effect and sensitivity analysis

Where ΔY it represents firm performance, ΔY it-1 is first lag of dependent variable firm performance. All the independent variables (cash flow measures and metrics) are denoted with ΔX it . CONTROLS it represents control variables and λ t shows time fixed effects, Ƞ i represents industry fixed effects, and ɛ it represents unobserved heterogeneity factors.

Table 6 represents estimated results obtained using Eq (8) . The findings of study observes significant negative association between cash flow measures, metrics and firm financial performance in the full sample, high leverage and low leverage subsamples, indicating that firms’ changes in cash flow measures and metrics bring significant positive improvements in financial performance. Overall, the results still hold after study considers the endogeneity problem, supporting the hypotheses of the study.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135.t006

Where ΔY it represents firm performance. All the independent variables (cash flow measures and metrics) are denoted with ΔX it-1 , and CONTROLS it represents control variables. D t shows time fixed effect, D i represents industry fixed effects, and ɛ it represents unobserved heterogeneity factors.

Table 7 represents estimated results of sensitivity analysis regression. The study finds that estimated coefficients of cash flow measures (ΔARTD t-1 , ΔITD t-1 , ΔAPTD t-1 ) and cash flow metrics (ΔCCC t-1 , ΔOCC t-1 ) are negative and significant, indicating that changes in previous period’s cash flow measures (ΔARTD t-1 , ΔITD t-1 , ΔAPTD t-1 ) and cash flow metrics (ΔCCC t-1 , ΔOCC t-1 ) bring significant positive changes in firm financial performance. The study finds similar results to the previously reported findings for alternative subsamples of high leverage and low leverage firms. Overall, the sensitivity analysis results still hold in consistent with the primary analysis results and ensure robustness of main analysis results of the study.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135.t007

Practical, managerial, and regulatory implications

This study provides significant practical, managerial, and regulatory implications for cash flow management and working capital management decisions in the corporate sector to improve performance. Most studies on cash flow management have focused on its relationship to profitability from the perspective of manufacturing companies. This research focuses on cash flow management by linking the leverage of non-financial firms in the Chinese context, a fundamental issue of corporate cash flow management and working capital investment that has not been studied much in the emerging markets scenario. Practically study suggests that a decline in cash flow measures and metrics positively enhances a company’s financial performance. Moreover, the paper determines that low-leverage industries perform healthier to cash flow measures and metrics changes. The study also reveals that companies in low-debt industries experience more positive improvements in their financial performance relative to high-debt industry companies. Therefore, the findings of this paper suggest that highly leveraged companies may be less conducive to improving corporate performance in industries where competitors’ leverage is relatively low.

Thus, from managers’ and policymakers’ points of view, the analysis found that changes in cash flow measures (ARTD, ITD, and APTD) and metrics (CCC and OCC) have led to significant positive improvements in the company’s financial performance. These positive changes in the CCC mean that changes in the accounts payable cycle appear to mitigate the combined impact of changes in the accounts receivable and inventory cycles. For managers, this finding suggests that reducing CCC simply by lowering APTD can translate into improvements in company performance. These findings provide rich insights and practical implications for managers and policymakers to use CCC as an operational tool to improve company performance. Therefore, managers and policymakers must actively evaluate the company’s policies regarding cash flow management, working capital management, corporate leverage, and capital budgeting policy before capitalizing on these companies.

Conclusion, limitations, and future implications

Cash flow management is the central issue of company operational strategies that affect a firm’s operational decisions and financial position. Firms’ effective policy of cash flow management is achievable through efficient management of working capital, which is possible through shorter days of accounts receivables, giving discounts on prompt payments, offering cash incentives, reducing inventory turning days through sound inventory management policies, shortening days of accounts payable by achieving rebate on early outlays. Likewise, inventory turnover may lead to a significant positive relationship with organizational performance symbolized by return on assets, cash flow margins, and return on sales in the JIT context. Moreover, high-performance firms may have a lengthier duration of days of accounts payables, which ensures the presence of liquidity. Many firms invest a large portion of their cash in working capital, which suggests that efficient working capital management significantly impacts corporate profitability.

This paper offers a strong insight and findings on cash flow management and firm financial performance by examining the Chinese full sample firms, high debt, and low debt firms to investigate the impact of changes in cash flow measures and metrics on firm performance. Using the exclusive cash flow measures and metrics data, study finds that decline in cash flow measures and metrics bring significant positive changes in firm financial performance. Moreover, study finds that low leveraged industries are better off in terms of changes in cash flow measures and metrics that bring more positive improvements in low debt industries firms’ financial performance relatively to high debt industries firms. This paper also demonstrates that, following firms’ leverage, high-leveraged firms may be less advantageous to enhance firm performance in industries where rivals are relatively low-leveraged.

The results of the study are consistent with the argument that changes in cash flow measure (ARTD, ITD and APTD) and metrics (CCC and OCC) bring significant positive improvements in firm financial performance. These findings furnish a great amount of insight and practical implication for manager to utilize CCC as operating tool in order to enhance firm performance. Firms by actively monitoring and controlling levers such as; ARTD, ITD, APTD, CCC, OCC can enhance financial performance. The findings of results are robust to different measures and metrics of cash flow and firm financial performance, following sensitivity analysis and endogeneity test still main results hold and ensures the robustness of primary analysis.

Study limitations and directions for future research

This research is of great significance to the studies on the relationship between cash flow management and enterprise performance in the Chinese market environment. However, the study did not consider some aspects that need consideration in future studies. This study uses Tobin Q to measure a company’s performance. However, it is also possible to include other company performance indicators that are important in the strategic impact of studies and may provide significant insights. The lack of data availability is a major constraint due to companies’ exits and entry into the sample period. This paper uses secondary data; however, studies can also use primary data to understand and gain appropriate knowledge of corporate cash flow management by combining archived and survey data to improve the robustness and significance of research findings in the context of emerging markets. This study focuses on the financial performance of firms. However, future studies can also use non-financial performance as a consequence variable.

Future extensions of this work may examine whether a company’s cash flow management policies in other areas of the supply chain have a similar relationship to company performance.

In addition, further inquiries that explore the directional association amid inventory and performance changes may extend the understanding of the cash flow management role in a company’s success. In addition, there is a need to explore more the impact of cash flow and working capital investment on firm performance by taking the market imperfections within the framework of emerging economies. Finally, the evidence of this research from the fastest emergent economy of the world may also use other transition economies to generalize for a widespread population group. Finally, studies in the future can consider linking product market competition with the cash flow measures, metrics, and firm performance relationship.

Supporting information

S1 appendix..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287135.s001

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank anonymous referees for all value comments. The authors are responsible for any remaining errors.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 8. China, K. P. M. G. China’s 12th five-year plan: Overview. China : KPMG Advisory . 2011.

- 9. Hale G., Long C. What are the sources of financing of the Chinese firms? In Cheung Y.-W., Kakkas V., Ma G. (eds.) The Evolving Role of Asia in Global Finance . Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Bingley, UK, 2011; 313–337.

- PubMed/NCBI

- 40. Dewing A.S. The financial policy of corporations, fourth ed. The Ronald Press Company, New York. 1941.

- 41. Arnold G. Financial Times Handbook of Corporate Finance : A Business Companion to Financial Markets , Decisions and Techniques . Pearson UK. 2013.

- 42. Fisher I. Theory of interest: As determined by impatience to spend income and opportunity to invest it. Augustusm Kelly Publishers. 1930.

- 55. Laghari, F., Chengang, Y., Chenyun, Y., Liu, Y., & Xiang, L. Corporate Liquidity Management in Emerging Economies under the Financial Constraints: Evidence from China. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society , 2022.

- 82. Womack J.P. and Jones D.T. Lean thinking: banish waste and create wealth in your Corporation. Simon & Schuster, New York, NY. 2003.

- 87. Radjou N., Orlov L. M., & Nakashima T. Adapting to supply network change. Forrester Research Inc, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 2002.

- 88. Singhal, V. R. Excess inventory and long-term stock price performance. College of Management , Georgia Institute of Technology . 2005.

- 110. Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS, (Second ed.). Sage Publications Ltd, London. 2005.

- Open access

- Published: 15 March 2023

A multidimensional review of the cash management problem

- Francisco Salas-Molina ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1168-7931 1 ,

- Juan A. Rodríguez-Aguilar 2 &

- Montserrat Guillen 3

Financial Innovation volume 9 , Article number: 67 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

8044 Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

In this paper, we summarize and analyze the relevant research on the cash management problem appearing in the literature. First, we identify the main dimensions of the cash management problem. Next, we review the most relevant contributions in this field and present a multidimensional analysis of these contributions, according to the dimensions of the problem. From this analysis, several open research questions are highlighted.

Introduction

Cash managers must make daily decisions about the number of transactions between cash holdings and any other type of available investment asset. On the one hand, a certain amount of cash must be kept for operational and precautionary purposes. On the other hand, idle cash balances may be invested in short-term assets such as interest-bearing accounts or treasury bills for profit. Since Baumol ( 1952 ), several cash management models have been proposed to address the cash management problem(CMP).

Keynes ( 1936 ) initially identified three motives for holding cash: the transaction motive, the precautionary motive and the speculative motive. Other authors have added other motives for holding cash, such as the agency motive (Jensen 1986 ) or tax motive (Foley et al. 2007 ). More recently, other authors have highlighted other determinants of corporate cash policies (e.g., Gao et al. ( 2013 ) and Pinkowitz et al. ( 2016 )). As a result, the first objective of this study is to review the literature related to CMP from an economic and financial perspective, derived from the analysis of the main motives for holding cash.

While most cash management literature stems from the seminal paper by Baumol ( 1952 ), many cash management works approach CMP from a decision-making perspective. Our second objective is to review the literature related to CMP from a decision-making perspective, considering models proposed by different researchers to deal with cash when the ultimate goal is to elicit a cash management policy, namely, a temporal sequence of transactions between accounts.

To the best of our knowledge, only three surveys on cash management have been published since the 1950s. Gregory ( 1976 ) covered the beginning of the cash management literature including the important works by Baumol ( 1952 ) and Miller and Orr ( 1966 ). Ten years later, Srinivasan and Kim ( 1986 ) extended the analysis to models not considered by Gregory ( 1976 ). Finally, da Costa Moraes et al. ( 2015 ) reviewed several stochastic models since the 1980s. However, there is a lack of taxonomy for classifying models and identifying open research questions in cash management.

Within the context of CMP, from a decision-making perspective, we propose a taxonomy based on the main dimensions of the cash management problem: (i) the model deployed, (ii) the type of cash flow process considered, (iii) the particular cost functions used, (iv) the objectives pursued by cash managers, (v) the method used to set the model and solve the problem, and (vi) the number of accounts considered. These six dimensions provide a sound framework to classify the cash management models proposed in the literature. Here, we focus on the most relevant models in terms of number of citations. For a comprehensive review, we refer interested readers to Gregory ( 1976 ), da Costa Moraes et al. ( 2015 ) and Srinivasan and Kim ( 1986 ).

Our taxonomy helps researchers use a common framework to establish cash management areas. In addition, our multidimensional analysis enhances the understanding of the cash management problem, making it easier to identify open research questions. Note that the multidimensional framework described in this paper is not limited to the six dimensions mentioned above. Researchers may extend the number of dimensions, thereby enriching the analysis of the cash management problem.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In " Motives for holding cash and related literature " in section, we consider the main motives for holding cash and review the literature related to CMP from an economic and financial perspective. In " A multidimensional taxonomy of the cash management problem " in section, we introduce and motivate the six dimensions of the CMP that define our taxonomy proposal. In " A review of the main contributions to the cash management problem " in section, we review the most relevant contributions to CMP from a decision-making perspective. Next, " A multidimensional analysis of the cash management problem " in section, we perform a comparative analysis of alternative cash management models that are directly linked to " Open research questions in cash management " in section, which identifies several open research questions in cash management. Finally, " Concluding remarks " in section concludes the paper.

Motives for holding cash and related literature

In this section, we consider the main motives for holding cash and review the literature related to CMP from an economics and finance perspective. We first consider the three motives for holding cash, initially identified by Keynes ( 1936 ), as follows:

The transaction motive, which is the need for cash for the current transaction of personal and business exchanges.

The precautionary motive, which is the desire for security as the future cash equivalent of a certain proportion of total resources acts as a financial reserve.

The speculative motive or the object of securing profit from knowing better than the market what the future will bring forth. The goal is to take advantage of future investment opportunities.

Later, Jensen ( 1986 ) argued that managers tend to accumulate cash rather than increase payouts to shareholders because of agency motives. Cash holdings may act as a buffer to cover eventual bad management decisions. One possible reason for this behavior is information asymmetry. Information is distributed asymmetrically throughout the organization; thus, managers usually have an advantage over shareholders in handling specific events because of information asymmetry (Eisenhardt 1989 ; Dierkens 1991 ). In addition, managers have an incentive to make the company bigger when compensation is linked to the size of the company, even when the company has poor investment opportunities. The motive for holding cash stems from the financial implications of agency theory (Jensen and Meckling 1976 ; Fama 1980 ; Fama and Jensen 1983 ; Eisenhardt 1989 ). In this theory, the firm is viewed as a set of contracts among the factors of production, in which each one is motivated by self-interest (Fama 1980 ). Consequently, the relationship between corporate managers (including cash managers) and owners presents friction due to conflicts of interest. The concept of agency costs defined by Jensen and Meckling ( 1976 ) is derived from an agency relationship in which managers and owners present divergences that result in monitoring costs, bonding costs to avoid certain actions, and other residual losses. One of these divergences relates to cash holdings. For example, consider that cash outflows to shareholders in the form of dividends reduce resources under managers’ control.

Kaplan and Zingales ( 1997 ) investigated the relationship between sensitivity of investment to cash flow and financing constraints, expressed as the differential cost between internal and external finance. They found that even though investment is sensitive to cash flow for the vast majority of firms analyzed, investment-cash flow sensitivities do not increase monotonically with the degree of financing constraints. Most of the firms analyzed could increase their investment if they choose to do so, thus providing further evidence of the agency motive for holding cash. Contrary to what was thought before, the authors concluded that higher sensitivities cannot be interpreted as evidence that firms are more financially constrained.

Leland ( 1998 ) argued that the key insight by Jensen and Meckling ( 1976 ) is that the firm’s choice of risk may depend on capital structure, hence challenging the Modigliani and Miller ( 1958 , 1963 ) assumption that investment decisions are independent of capital structure. Consequently, Leland ( 1998 ) proposed integrating both approaches to derive the optimal capital structure of a firm. The model reflects the interaction of different cash flow policies, namely, financing decisions and investment risk strategies. When investment policies are chosen, agency costs appear as a critical element in the model.

Further evidence of the agency motive for holding cash can be found in Dittmar et al. ( 2003 ), Pinkowitz et al. ( 2006 ), Dittmar and Mahrt-Smith ( 2007 ) and Harford et al. ( 2008 ). More recently, but still within the context of agency theory, Tran ( 2020 ) emphasized how external factors, such as the economic cycle, including the eventual financial crisis, affect cash holdings. The author found that the 2008 global financial crisis decreased the controlling effect of shareholder rights on corporate cash holdings, regardless of any control agency mechanism. Following a similar line of research, Tekin ( 2020 ) and Tekin et al. ( 2021 ) examined whether an agency cost explanation is valid for cash holdings during and after the financial crisis. During a financial crisis, agency costs tend to be higher than usual and the agency motive for holding cash is greater. The authors assessed the role of governance in cash management in 26 Asian developing countries and found that firms with poor governance increased their cash levels after the financial crisis. They concluded that cash holdings had a substitution effect on governance due to changes in managers’ risk aversion perceptions.

Cash management relates to financial constraints. The impact of financial restrictions on optimal cash holdings in the context of a financial crisis was considered by Tekin and Polat ( 2020 ), who compared firms in a highly regulated market with firms in a relatively unregulated market in the United Kingdom. The authors found that less-regulated firms had a faster adjustment of cash over the period 2002-2017. However, these firms decreased their cash adjustment speed more than highly regulated firms did during the financial crisis. Using a sample of firms from 26 developing Asian economies from 1991 to 2016, Tekin ( 2022 ) recently showed that financially constrained firms increased their cash levels more than financially unconstrained firms after the 2008 global financial crisis. In summary, exogenous shocks such as financial crises represent an important external factor in cash management.

Conversely, Foley et al. ( 2007 ) identify the tax motive for holding cash. More precisely, they found that the U.S. corporations, that would incur tax consequences associated with repatriating foreign earnings, hold higher levels of cash. Bates et al. ( 2009 ) showed that the average cash-to-assets ratio for U.S. industrial firms doubled from 1980 to 2006. They argue that the precautionary motive for cash holdings plays an important role in explaining the increase in cash ratios. From an analysis of the literature, Bates et al. ( 2009 ) summarized two additional motives for holding cash:

The agency motive, which is the need for cash derived from conflicts of interest among managers and owners.

The tax motive, which is the desire to avoid tax consequences associated with repatriation of foreign earnings.

Gao et al. ( 2013 ) analyzed a sample of public and private U.S. firms during the period 1995-2011 to conclude that public firms hold more cash than private firms. By examining the drivers of cash policies for each group, the authors attribute this difference to the much higher agency costs in public firms. Using a similar period (1998–2011), Pinkowitz et al. ( 2016 ) showed that U.S. firms held more cash on average than similar foreign firms. However, they argued that country characteristics had negligible explanatory power for the differences in cash holdings between U.S. firms and their foreign twins. Graham and Leary ( 2018 ) included the historic perspective in the analysis by studying average and aggregate cash holdings of companies in the U.S. from 1920 to 2014. Corporate cash holdings doubled in the first 25 years of the sample before returning to 1920 levels by 1970. Since then, the average and aggregate patterns have diverged.

Interest rates and environmental and health motives have recently been included in cash holding analyses. Gao et al. ( 2021 ) highlighted a non-monotonic relation between corporate cash and both real and nominal interest rates in both aggregate and firm-level data. The authors argue that these results imply that interest rates are unlikely to be the cause of the recent increase in corporate cash. Tan et al. ( 2021 ) compared cash holdings before and after the Environmental Inspection Program in China during the period 2014-2018 for manufacturing firms included and non-included in the program. The results suggest that this environmental program enhanced cash management efficiency because firms included in the program accumulated less cash. Finally, Alvarez and Argente ( 2022 ) focused on the impact of COVID-19 in household’s cash management behavior, considering the choice of means of payment and the average size and frequency of cash withdrawals. The authors used data on ATM (automated teller machine) cash disbursements in Argentina, Chile, and the U.S. to show that the intensity of the virus increased transaction costs.

A multidimensional taxonomy of the cash management problem

Cash flow management concerns the efficient use of a company’s cash and short-term investments (Gregory 1976 ). Cash is then viewed as a stock, a buffer, such as an inventory of wheat or bolts. Holding cash has a cost because of it being idle but, at the same time, transferring idle money to alternative investments is also costly. How much money should companies keep to operate efficiently? Identifying an appropriate answer to this question is the main goal of CMP. However, several aspects and dimensions must be considered to establish the boundaries of the problem. Hereafter, we focus on the main dimensions of the cash management problem, defining a cash management problem taxonomy to classify past research and identify open research questions.

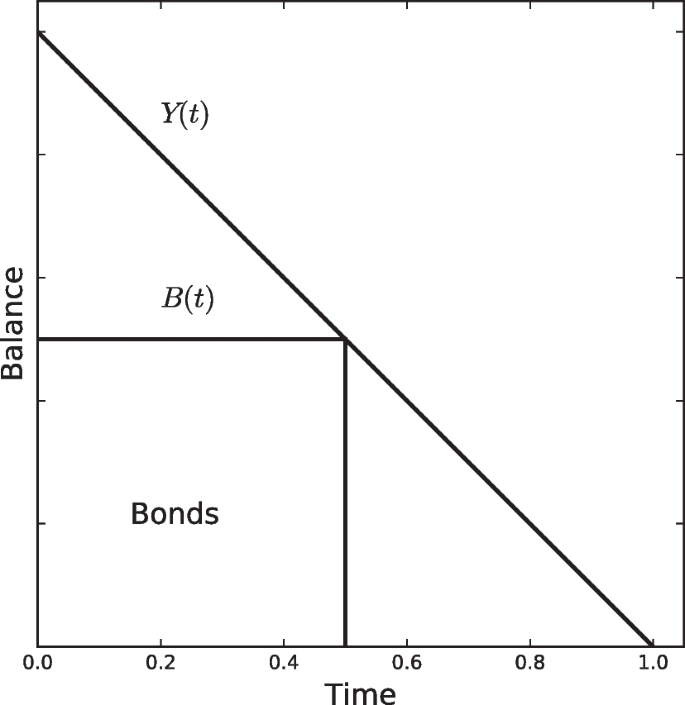

Cash management models

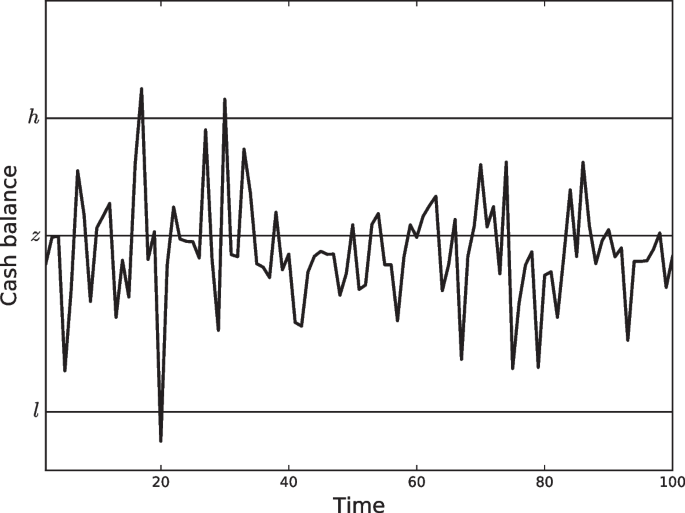

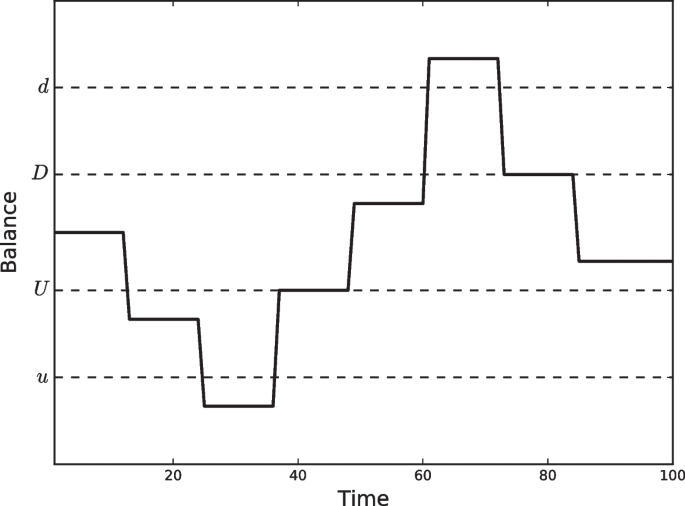

In an attempt to solve CMP, several cash management models have been proposed to control cash balances based on a set of levels or bounds. CMP was first proposed from an inventory control perspective by Baumol ( 1952 ) in a deterministic manner. Later, Miller and Orr ( 1966 ) followed a stochastic approach, assuming that cash balance changes are random. Many other models have been developed based on these two seminal works. Most previous models assume a set of bounds to control cash balances; however, alternative configurations are also suitable.

Cash flow process

Cash flow statistical characterization is also a key issue in understanding cash management. Separation between inflows and outflows, or receipts and disbursements, is the basic breakdown, but a more detailed separation can be helpful when trying to extract patterns from data. In this sense, Stone and Miller ( 1981 , 1987 ) suggest the utility of problem structuring, or breaking down a problem into different subproblems, to appropriately handle cash flow forecasting as a key task in cash management. In addition, common assumptions on the statistical properties of cash flows include (i) normality, meaning that its values are centered around the average following a Gaussian distribution; (ii) independence, meaning that its values are not correlated with each other; and (iii) stationarity, meaning that its mean and variance are constant with time. However, little empirical evidence on the statistical properties of cash flow has been provided, with the exception of Mullins and Homonoff ( 1976 ), Emery ( 1981 ), Pindado and Vico ( 1996 ).

Costs in cash management

The main objective of managing cash is to keep the amount of available cash as low as possible while still keeping the company operating efficiently. Additionally, companies may place idle cash in short-term investments (Ross et al. 2002 ). Thus, the cash management problem can be viewed as a trade-off between holding and transaction costs. On the one hand, holding costs are usually opportunity costs due to idle cash that can be allocated to alternative investments. Holding too much cash is inefficient but holding too little may result in high shortage costs. On the other hand, transaction costs are associated with the movement of cash from/into a cash account into/from any other short-term available asset, such as treasury bills and other marketable securities. In summary, if a company tries to keep balances too low, holding costs will be reduced, but undesirable situations of shortage will force the sale of available marketable securities, thereby increasing transaction costs. By contrast, if the balance is too high, low trading costs will be incurred due to unexpected cash flow, but the company will carry high holding costs because no interest is earned on cash. Therefore, the company must optimize its target cash balance.

Desired objectives

In cash management literature, the focus is typically placed on a single objective, namely, cost. Except for Zopounidis ( 1999 ), Salas-Molina et al. ( 2018 ), cash management and multi-criteria decision-making are not usually linked concepts in financial literature. However, risk management is an important task in decision-making, and since different cash strategies entail different degrees of risk, a quantitative approach to measure risk is required. Furthermore, due to the different degrees of risk that firms are willing to accept, risk preferences are also an important issue for decision-makers.

Solving the cash management problem

Cash management poses a general optimization problem, namely, determining a policy that optimizes objective functions. However, several different techniques have been used to solve this optimization problem, ranging from mathematical programming, such as dynamic programming (Eppen and Fama 1968 ; Penttinen 1991 ) and control theory methods Sethi and Thompson ( 1970 ), to approximate techniques such as genetic algorithms (Gormley and Meade 2007 ; da Costa Moraes and Nagano 2014 ). An important question regarding alternative solvers is the optimality of solutions, which is a desired objective, but must be balanced with computational and deployment costs.

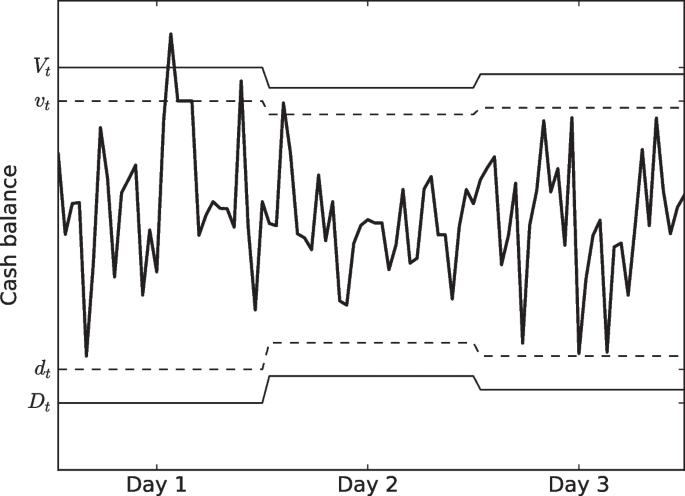

Managing multiple bank accounts