Biology library

Course: biology library > unit 1, the scientific method.

- Controlled experiments

- The scientific method and experimental design

Introduction

- Make an observation.

- Ask a question.

- Form a hypothesis , or testable explanation.

- Make a prediction based on the hypothesis.

- Test the prediction.

- Iterate: use the results to make new hypotheses or predictions.

Scientific method example: Failure to toast

1. make an observation..

- Observation: the toaster won't toast.

2. Ask a question.

- Question: Why won't my toaster toast?

3. Propose a hypothesis.

- Hypothesis: Maybe the outlet is broken.

4. Make predictions.

- Prediction: If I plug the toaster into a different outlet, then it will toast the bread.

5. Test the predictions.

- Test of prediction: Plug the toaster into a different outlet and try again.

- If the toaster does toast, then the hypothesis is supported—likely correct.

- If the toaster doesn't toast, then the hypothesis is not supported—likely wrong.

Logical possibility

Practical possibility, building a body of evidence, 6. iterate..

- Iteration time!

- If the hypothesis was supported, we might do additional tests to confirm it, or revise it to be more specific. For instance, we might investigate why the outlet is broken.

- If the hypothesis was not supported, we would come up with a new hypothesis. For instance, the next hypothesis might be that there's a broken wire in the toaster.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Six Steps of the Scientific Method

Learn What Makes Each Stage Important

ThoughtCo. / Hugo Lin

- Scientific Method

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

The scientific method is a systematic way of learning about the world around us and answering questions. The key difference between the scientific method and other ways of acquiring knowledge are forming a hypothesis and then testing it with an experiment.

The Six Steps

The number of steps can vary from one description to another (which mainly happens when data and analysis are separated into separate steps), however, this is a fairly standard list of the six scientific method steps that you are expected to know for any science class:

- Purpose/Question Ask a question.

- Research Conduct background research. Write down your sources so you can cite your references. In the modern era, a lot of your research may be conducted online. Scroll to the bottom of articles to check the references. Even if you can't access the full text of a published article, you can usually view the abstract to see the summary of other experiments. Interview experts on a topic. The more you know about a subject, the easier it will be to conduct your investigation.

- Hypothesis Propose a hypothesis . This is a sort of educated guess about what you expect. It is a statement used to predict the outcome of an experiment. Usually, a hypothesis is written in terms of cause and effect. Alternatively, it may describe the relationship between two phenomena. One type of hypothesis is the null hypothesis or the no-difference hypothesis. This is an easy type of hypothesis to test because it assumes changing a variable will have no effect on the outcome. In reality, you probably expect a change but rejecting a hypothesis may be more useful than accepting one.

- Experiment Design and perform an experiment to test your hypothesis. An experiment has an independent and dependent variable. You change or control the independent variable and record the effect it has on the dependent variable . It's important to change only one variable for an experiment rather than try to combine the effects of variables in an experiment. For example, if you want to test the effects of light intensity and fertilizer concentration on the growth rate of a plant, you're really looking at two separate experiments.

- Data/Analysis Record observations and analyze the meaning of the data. Often, you'll prepare a table or graph of the data. Don't throw out data points you think are bad or that don't support your predictions. Some of the most incredible discoveries in science were made because the data looked wrong! Once you have the data, you may need to perform a mathematical analysis to support or refute your hypothesis.

- Conclusion Conclude whether to accept or reject your hypothesis. There is no right or wrong outcome to an experiment, so either result is fine. Accepting a hypothesis does not necessarily mean it's correct! Sometimes repeating an experiment may give a different result. In other cases, a hypothesis may predict an outcome, yet you might draw an incorrect conclusion. Communicate your results. The results may be compiled into a lab report or formally submitted as a paper. Whether you accept or reject the hypothesis, you likely learned something about the subject and may wish to revise the original hypothesis or form a new one for a future experiment.

When Are There Seven Steps?

Sometimes the scientific method is taught with seven steps instead of six. In this model, the first step of the scientific method is to make observations. Really, even if you don't make observations formally, you think about prior experiences with a subject in order to ask a question or solve a problem.

Formal observations are a type of brainstorming that can help you find an idea and form a hypothesis. Observe your subject and record everything about it. Include colors, timing, sounds, temperatures, changes, behavior, and anything that strikes you as interesting or significant.

When you design an experiment, you are controlling and measuring variables. There are three types of variables:

- Controlled Variables: You can have as many controlled variables as you like. These are parts of the experiment that you try to keep constant throughout an experiment so that they won't interfere with your test. Writing down controlled variables is a good idea because it helps make your experiment reproducible , which is important in science! If you have trouble duplicating results from one experiment to another, there may be a controlled variable that you missed.

- Independent Variable: This is the variable you control.

- Dependent Variable: This is the variable you measure. It is called the dependent variable because it depends on the independent variable.

- Scientific Method Flow Chart

- What Is an Experiment? Definition and Design

- How To Design a Science Fair Experiment

- What Is a Hypothesis? (Science)

- Scientific Variable

- What Are the Elements of a Good Hypothesis?

- Scientific Method Vocabulary Terms

- Understanding Simple vs Controlled Experiments

- What Are Independent and Dependent Variables?

- Null Hypothesis Examples

- Null Hypothesis Definition and Examples

- Scientific Method Lesson Plan

- Dependent Variable Definition and Examples

- What Is a Testable Hypothesis?

- How to Write a Lab Report

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Scientific Method Steps in Psychology Research

Steps, Uses, and Key Terms

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Verywell / Theresa Chiechi

How do researchers investigate psychological phenomena? They utilize a process known as the scientific method to study different aspects of how people think and behave.

When conducting research, the scientific method steps to follow are:

- Observe what you want to investigate

- Ask a research question and make predictions

- Test the hypothesis and collect data

- Examine the results and draw conclusions

- Report and share the results

This process not only allows scientists to investigate and understand different psychological phenomena but also provides researchers and others a way to share and discuss the results of their studies.

Generally, there are five main steps in the scientific method, although some may break down this process into six or seven steps. An additional step in the process can also include developing new research questions based on your findings.

What Is the Scientific Method?

What is the scientific method and how is it used in psychology?

The scientific method consists of five steps. It is essentially a step-by-step process that researchers can follow to determine if there is some type of relationship between two or more variables.

By knowing the steps of the scientific method, you can better understand the process researchers go through to arrive at conclusions about human behavior.

Scientific Method Steps

While research studies can vary, these are the basic steps that psychologists and scientists use when investigating human behavior.

The following are the scientific method steps:

Step 1. Make an Observation

Before a researcher can begin, they must choose a topic to study. Once an area of interest has been chosen, the researchers must then conduct a thorough review of the existing literature on the subject. This review will provide valuable information about what has already been learned about the topic and what questions remain to be answered.

A literature review might involve looking at a considerable amount of written material from both books and academic journals dating back decades.

The relevant information collected by the researcher will be presented in the introduction section of the final published study results. This background material will also help the researcher with the first major step in conducting a psychology study: formulating a hypothesis.

Step 2. Ask a Question

Once a researcher has observed something and gained some background information on the topic, the next step is to ask a question. The researcher will form a hypothesis, which is an educated guess about the relationship between two or more variables

For example, a researcher might ask a question about the relationship between sleep and academic performance: Do students who get more sleep perform better on tests at school?

In order to formulate a good hypothesis, it is important to think about different questions you might have about a particular topic.

You should also consider how you could investigate the causes. Falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In other words, if a hypothesis was false, there needs to be a way for scientists to demonstrate that it is false.

Step 3. Test Your Hypothesis and Collect Data

Once you have a solid hypothesis, the next step of the scientific method is to put this hunch to the test by collecting data. The exact methods used to investigate a hypothesis depend on exactly what is being studied. There are two basic forms of research that a psychologist might utilize: descriptive research or experimental research.

Descriptive research is typically used when it would be difficult or even impossible to manipulate the variables in question. Examples of descriptive research include case studies, naturalistic observation , and correlation studies. Phone surveys that are often used by marketers are one example of descriptive research.

Correlational studies are quite common in psychology research. While they do not allow researchers to determine cause-and-effect, they do make it possible to spot relationships between different variables and to measure the strength of those relationships.

Experimental research is used to explore cause-and-effect relationships between two or more variables. This type of research involves systematically manipulating an independent variable and then measuring the effect that it has on a defined dependent variable .

One of the major advantages of this method is that it allows researchers to actually determine if changes in one variable actually cause changes in another.

While psychology experiments are often quite complex, a simple experiment is fairly basic but does allow researchers to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. Most simple experiments use a control group (those who do not receive the treatment) and an experimental group (those who do receive the treatment).

Step 4. Examine the Results and Draw Conclusions

Once a researcher has designed the study and collected the data, it is time to examine this information and draw conclusions about what has been found. Using statistics , researchers can summarize the data, analyze the results, and draw conclusions based on this evidence.

So how does a researcher decide what the results of a study mean? Not only can statistical analysis support (or refute) the researcher’s hypothesis; it can also be used to determine if the findings are statistically significant.

When results are said to be statistically significant, it means that it is unlikely that these results are due to chance.

Based on these observations, researchers must then determine what the results mean. In some cases, an experiment will support a hypothesis, but in other cases, it will fail to support the hypothesis.

So what happens if the results of a psychology experiment do not support the researcher's hypothesis? Does this mean that the study was worthless?

Just because the findings fail to support the hypothesis does not mean that the research is not useful or informative. In fact, such research plays an important role in helping scientists develop new questions and hypotheses to explore in the future.

After conclusions have been drawn, the next step is to share the results with the rest of the scientific community. This is an important part of the process because it contributes to the overall knowledge base and can help other scientists find new research avenues to explore.

Step 5. Report the Results

The final step in a psychology study is to report the findings. This is often done by writing up a description of the study and publishing the article in an academic or professional journal. The results of psychological studies can be seen in peer-reviewed journals such as Psychological Bulletin , the Journal of Social Psychology , Developmental Psychology , and many others.

The structure of a journal article follows a specified format that has been outlined by the American Psychological Association (APA) . In these articles, researchers:

- Provide a brief history and background on previous research

- Present their hypothesis

- Identify who participated in the study and how they were selected

- Provide operational definitions for each variable

- Describe the measures and procedures that were used to collect data

- Explain how the information collected was analyzed

- Discuss what the results mean

Why is such a detailed record of a psychological study so important? By clearly explaining the steps and procedures used throughout the study, other researchers can then replicate the results. The editorial process employed by academic and professional journals ensures that each article that is submitted undergoes a thorough peer review, which helps ensure that the study is scientifically sound.

Once published, the study becomes another piece of the existing puzzle of our knowledge base on that topic.

Before you begin exploring the scientific method steps, here's a review of some key terms and definitions that you should be familiar with:

- Falsifiable : The variables can be measured so that if a hypothesis is false, it can be proven false

- Hypothesis : An educated guess about the possible relationship between two or more variables

- Variable : A factor or element that can change in observable and measurable ways

- Operational definition : A full description of exactly how variables are defined, how they will be manipulated, and how they will be measured

Uses for the Scientific Method

The goals of psychological studies are to describe, explain, predict and perhaps influence mental processes or behaviors. In order to do this, psychologists utilize the scientific method to conduct psychological research. The scientific method is a set of principles and procedures that are used by researchers to develop questions, collect data, and reach conclusions.

Goals of Scientific Research in Psychology

Researchers seek not only to describe behaviors and explain why these behaviors occur; they also strive to create research that can be used to predict and even change human behavior.

Psychologists and other social scientists regularly propose explanations for human behavior. On a more informal level, people make judgments about the intentions, motivations , and actions of others on a daily basis.

While the everyday judgments we make about human behavior are subjective and anecdotal, researchers use the scientific method to study psychology in an objective and systematic way. The results of these studies are often reported in popular media, which leads many to wonder just how or why researchers arrived at the conclusions they did.

Examples of the Scientific Method

Now that you're familiar with the scientific method steps, it's useful to see how each step could work with a real-life example.

Say, for instance, that researchers set out to discover what the relationship is between psychotherapy and anxiety .

- Step 1. Make an observation : The researchers choose to focus their study on adults ages 25 to 40 with generalized anxiety disorder.

- Step 2. Ask a question : The question they want to answer in their study is: Do weekly psychotherapy sessions reduce symptoms in adults ages 25 to 40 with generalized anxiety disorder?

- Step 3. Test your hypothesis : Researchers collect data on participants' anxiety symptoms . They work with therapists to create a consistent program that all participants undergo. Group 1 may attend therapy once per week, whereas group 2 does not attend therapy.

- Step 4. Examine the results : Participants record their symptoms and any changes over a period of three months. After this period, people in group 1 report significant improvements in their anxiety symptoms, whereas those in group 2 report no significant changes.

- Step 5. Report the results : Researchers write a report that includes their hypothesis, information on participants, variables, procedure, and conclusions drawn from the study. In this case, they say that "Weekly therapy sessions are shown to reduce anxiety symptoms in adults ages 25 to 40."

Of course, there are many details that go into planning and executing a study such as this. But this general outline gives you an idea of how an idea is formulated and tested, and how researchers arrive at results using the scientific method.

Erol A. How to conduct scientific research ? Noro Psikiyatr Ars . 2017;54(2):97-98. doi:10.5152/npa.2017.0120102

University of Minnesota. Psychologists use the scientific method to guide their research .

Shaughnessy, JJ, Zechmeister, EB, & Zechmeister, JS. Research Methods In Psychology . New York: McGraw Hill Education; 2015.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

A Beginner's Guide to Starting the Research Process

When you have to write a thesis or dissertation , it can be hard to know where to begin, but there are some clear steps you can follow.

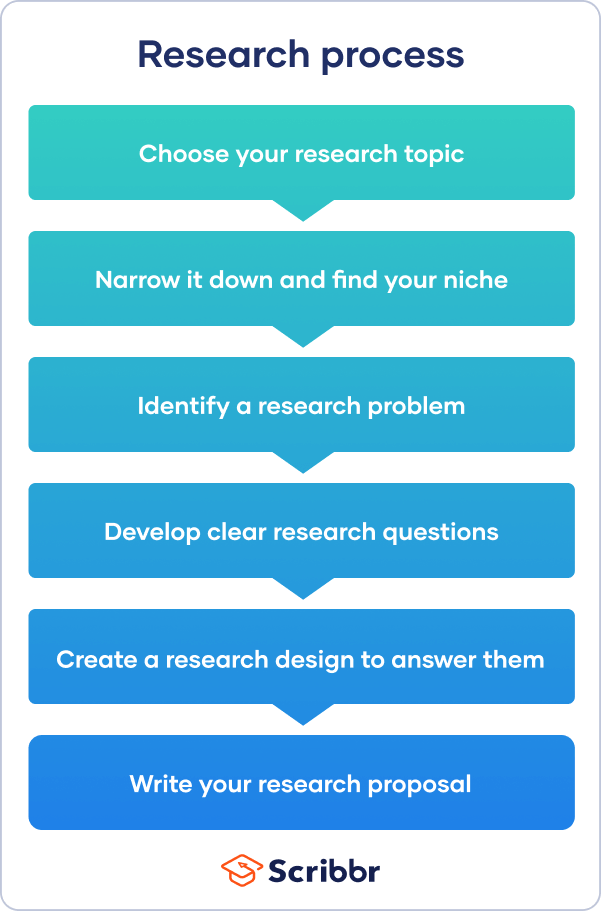

The research process often begins with a very broad idea for a topic you’d like to know more about. You do some preliminary research to identify a problem . After refining your research questions , you can lay out the foundations of your research design , leading to a proposal that outlines your ideas and plans.

This article takes you through the first steps of the research process, helping you narrow down your ideas and build up a strong foundation for your research project.

Table of contents

Step 1: choose your topic, step 2: identify a problem, step 3: formulate research questions, step 4: create a research design, step 5: write a research proposal, other interesting articles.

First you have to come up with some ideas. Your thesis or dissertation topic can start out very broad. Think about the general area or field you’re interested in—maybe you already have specific research interests based on classes you’ve taken, or maybe you had to consider your topic when applying to graduate school and writing a statement of purpose .

Even if you already have a good sense of your topic, you’ll need to read widely to build background knowledge and begin narrowing down your ideas. Conduct an initial literature review to begin gathering relevant sources. As you read, take notes and try to identify problems, questions, debates, contradictions and gaps. Your aim is to narrow down from a broad area of interest to a specific niche.

Make sure to consider the practicalities: the requirements of your programme, the amount of time you have to complete the research, and how difficult it will be to access sources and data on the topic. Before moving onto the next stage, it’s a good idea to discuss the topic with your thesis supervisor.

>>Read more about narrowing down a research topic

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

So you’ve settled on a topic and found a niche—but what exactly will your research investigate, and why does it matter? To give your project focus and purpose, you have to define a research problem .

The problem might be a practical issue—for example, a process or practice that isn’t working well, an area of concern in an organization’s performance, or a difficulty faced by a specific group of people in society.

Alternatively, you might choose to investigate a theoretical problem—for example, an underexplored phenomenon or relationship, a contradiction between different models or theories, or an unresolved debate among scholars.

To put the problem in context and set your objectives, you can write a problem statement . This describes who the problem affects, why research is needed, and how your research project will contribute to solving it.

>>Read more about defining a research problem

Next, based on the problem statement, you need to write one or more research questions . These target exactly what you want to find out. They might focus on describing, comparing, evaluating, or explaining the research problem.

A strong research question should be specific enough that you can answer it thoroughly using appropriate qualitative or quantitative research methods. It should also be complex enough to require in-depth investigation, analysis, and argument. Questions that can be answered with “yes/no” or with easily available facts are not complex enough for a thesis or dissertation.

In some types of research, at this stage you might also have to develop a conceptual framework and testable hypotheses .

>>See research question examples

The research design is a practical framework for answering your research questions. It involves making decisions about the type of data you need, the methods you’ll use to collect and analyze it, and the location and timescale of your research.

There are often many possible paths you can take to answering your questions. The decisions you make will partly be based on your priorities. For example, do you want to determine causes and effects, draw generalizable conclusions, or understand the details of a specific context?

You need to decide whether you will use primary or secondary data and qualitative or quantitative methods . You also need to determine the specific tools, procedures, and materials you’ll use to collect and analyze your data, as well as your criteria for selecting participants or sources.

>>Read more about creating a research design

Finally, after completing these steps, you are ready to complete a research proposal . The proposal outlines the context, relevance, purpose, and plan of your research.

As well as outlining the background, problem statement, and research questions, the proposal should also include a literature review that shows how your project will fit into existing work on the topic. The research design section describes your approach and explains exactly what you will do.

You might have to get the proposal approved by your supervisor before you get started, and it will guide the process of writing your thesis or dissertation.

>>Read more about writing a research proposal

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

More interesting articles

- 10 Research Question Examples to Guide Your Research Project

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

- How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

- How to Write a Problem Statement | Guide & Examples

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Objectives | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Fishbone Diagram? | Templates & Examples

- What Is Root Cause Analysis? | Definition & Examples

Unlimited Academic AI-Proofreading

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Sciencing_Icons_Science SCIENCE

Sciencing_icons_biology biology, sciencing_icons_cells cells, sciencing_icons_molecular molecular, sciencing_icons_microorganisms microorganisms, sciencing_icons_genetics genetics, sciencing_icons_human body human body, sciencing_icons_ecology ecology, sciencing_icons_chemistry chemistry, sciencing_icons_atomic & molecular structure atomic & molecular structure, sciencing_icons_bonds bonds, sciencing_icons_reactions reactions, sciencing_icons_stoichiometry stoichiometry, sciencing_icons_solutions solutions, sciencing_icons_acids & bases acids & bases, sciencing_icons_thermodynamics thermodynamics, sciencing_icons_organic chemistry organic chemistry, sciencing_icons_physics physics, sciencing_icons_fundamentals-physics fundamentals, sciencing_icons_electronics electronics, sciencing_icons_waves waves, sciencing_icons_energy energy, sciencing_icons_fluid fluid, sciencing_icons_astronomy astronomy, sciencing_icons_geology geology, sciencing_icons_fundamentals-geology fundamentals, sciencing_icons_minerals & rocks minerals & rocks, sciencing_icons_earth scructure earth structure, sciencing_icons_fossils fossils, sciencing_icons_natural disasters natural disasters, sciencing_icons_nature nature, sciencing_icons_ecosystems ecosystems, sciencing_icons_environment environment, sciencing_icons_insects insects, sciencing_icons_plants & mushrooms plants & mushrooms, sciencing_icons_animals animals, sciencing_icons_math math, sciencing_icons_arithmetic arithmetic, sciencing_icons_addition & subtraction addition & subtraction, sciencing_icons_multiplication & division multiplication & division, sciencing_icons_decimals decimals, sciencing_icons_fractions fractions, sciencing_icons_conversions conversions, sciencing_icons_algebra algebra, sciencing_icons_working with units working with units, sciencing_icons_equations & expressions equations & expressions, sciencing_icons_ratios & proportions ratios & proportions, sciencing_icons_inequalities inequalities, sciencing_icons_exponents & logarithms exponents & logarithms, sciencing_icons_factorization factorization, sciencing_icons_functions functions, sciencing_icons_linear equations linear equations, sciencing_icons_graphs graphs, sciencing_icons_quadratics quadratics, sciencing_icons_polynomials polynomials, sciencing_icons_geometry geometry, sciencing_icons_fundamentals-geometry fundamentals, sciencing_icons_cartesian cartesian, sciencing_icons_circles circles, sciencing_icons_solids solids, sciencing_icons_trigonometry trigonometry, sciencing_icons_probability-statistics probability & statistics, sciencing_icons_mean-median-mode mean/median/mode, sciencing_icons_independent-dependent variables independent/dependent variables, sciencing_icons_deviation deviation, sciencing_icons_correlation correlation, sciencing_icons_sampling sampling, sciencing_icons_distributions distributions, sciencing_icons_probability probability, sciencing_icons_calculus calculus, sciencing_icons_differentiation-integration differentiation/integration, sciencing_icons_application application, sciencing_icons_projects projects, sciencing_icons_news news.

- Share Tweet Email Print

- Home ⋅

- Science Fair Project Ideas for Kids, Middle & High School Students ⋅

- Probability & Statistics

Steps & Procedures for Conducting Scientific Research

Laboratory Observation Methods

A good scientist practices objectivity to avoid errors and personal biases that may lead to falsified research. The entire scientific research process--from defining the research question to drawing conclusions about data--requires the researcher to think critically and approach issues in an organized and systematic way. Scientific research can lead to the confirmation or re-evaluation of existing theories or to the development of entirely new theories.

Defining Problem and Research

The first step of the scientific research process involves defining the problem and conducting research. First, a broad topic is selected concerning some topic or a research question is asked. The scientist researches the question to determine if it has been answered or the types of conclusions other researchers have drawn and experiments that have been carried out in relation to the question. Research involves reading scholarly journal articles from other scientists, which can be found on the Internet via research databases and journals that publish academic articles online. During research, the scientist narrows down the broad topic into a specific research question about some issue.

The hypothesis is a concise, clear statement containing the main idea or purpose of your scientific research. A hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable, meaning there must be a way to test the hypothesis and it can either be supported or rejected based on examining data. Crafting a hypothesis requires you to define the variables you're researching (e.g., who or what you're studying), explain them with clarity and explain your position. When writing the hypothesis, scientists either make a specific cause-and-effect statement about the variables being studied or make a general statement about the relationship between such variables.

Design Experiment

Designing a scientific experiment involves planning how you're going to collect data. Often, the nature of the research question influences how the scientific research will be conducted. For example, researching people's opinions naturally requires conducting surveys. When designing the experiment, the scientists selects from where and how the sample being studied will be obtained, the dates and times for the experiment, the controls being used and the other measures needed to carry out the research.

Collect Data

Data collection involves carrying out the experiment the scientist designed. During this process, the scientists record the data and complete the tasks required to conduct the experiments. In other words, the scientist goes to the research site to perform the experiment, such as a laboratory or some other setting. Tasks involved with conducting the experiment vary depending on the type of research. For example, some experiments require bringing human participants in for a test, conducting observations in the natural environment or experimenting with animal subjects.

Analyze Data

Analyzing data for the scientific research process involves bringing the data together and calculating statistics. Statistical tests can help the scientist understand the data better and tell whether a significant result is found. Calculating the statistics for a scientific research experiment uses both descriptive statistics and inferential statistics measures. Descriptive statistics describe the data and samples collected, such as sample averages or means, as well as the standard deviation that tells the scientists how the data is distributed. Inferential statistics involves conducting tests of significance that have the power to either confirm or reject the original hypothesis.

Draw Conclusions

After the data from an experiment is analyzed, the scientist examines the information and makes conclusions based on the findings. The scientist compares the results both to the original hypothesis and the conclusions of previous experiments by other researchers. When drawing conclusions, the scientist explains what the results mean and how to view them in the context of the scientific field or real-world environment, as well as making suggestions for future research.

Related Articles

How to eliminate bias in qualitative research, 5 components of a well-designed scientific experiment, types of observation in the scientific method, distinguishing between descriptive & causal studies, essential tenets of the scientific method, difference between proposition & hypothesis, how to write results for a science fair project, research methods in science, what are the 8 steps in scientific research, 10 characteristics of a science experiment, what is normative & descriptive science, the six parts of an experimental science project, why should you only test for one variable at a time..., what is the next step if an experiment fails to confirm..., writing objectives for lab reports, how to calculate success rate, the differences between concepts, theories & paradigms, how to use the scientific method in everyday life.

About the Author

Matthew Schieltz has been a freelance web writer since August 2006, and has experience writing a variety of informational articles, how-to guides, website and e-book content for organizations such as Demand Studios. Schieltz holds a Bachelor of Arts in psychology from Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. He plans to pursue graduate school in clinical psychology.

Photo Credits

diego cervo/iStock/Getty Images

Find Your Next Great Science Fair Project! GO

We Have More Great Sciencing Articles!

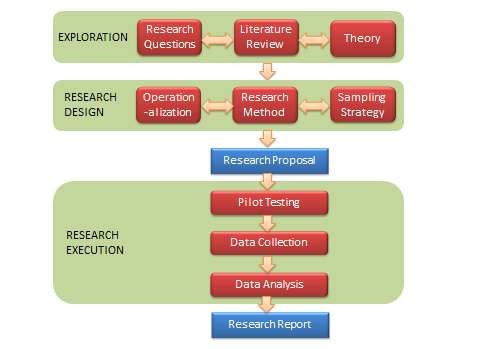

Overview of the Research Process

- First Online: 01 January 2012

Cite this chapter

- Phyllis G. Supino EdD 3

6252 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

Research is a rigorous problem-solving process whose ultimate goal is the discovery of new knowledge. Research may include the description of a new phenomenon, definition of a new relationship, development of a new model, or application of an existing principle or procedure to a new context. Research is systematic, logical, empirical, reductive, replicable and transmittable, and generalizable. Research can be classified according to a variety of dimensions: basic, applied, or translational; hypothesis generating or hypothesis testing; retrospective or prospective; longitudinal or cross-sectional; observational or experimental; and quantitative or qualitative. The ultimate success of a research project is heavily dependent on adequate planning.

- Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

- Prospective Research

- Control Hospital

- Putative Risk Factor

- Elective Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Calvert J, Martin BR (2001) Changing conceptions of basic research? Brighton, England: Background document for the Workshop on Policy Relevance and Measurement of Basic Research, Oslo, 29–30 Oct 2001. Brighton, England: SPRU.

Google Scholar

Leedy PD. Practical research. Planning and design. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 1997.

Tuckman BW. Conducting educational research. 3rd ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1972.

Tanenbaum SJ. Knowing and acting in medical practice. The epistemological policies of outcomes research. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1994;19:27–44.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Richardson WS. We should overcome the barriers to evidence-based clinical diagnosis! J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:217–27.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

MacCorquodale K, Meehl PE. On a distinction between hypothetical constructs and intervening variables. Psych Rev. 1948;55:95–107.

Article CAS Google Scholar

The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research: The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Washington: DHEW Publication No. (OS) 78–0012, Appendix I, DHEW Publication No. (OS) 78–0013, Appendix II, DHEW Publication (OS) 780014; 1978.

Coryn CLS. The fundamental characteristics of research. J Multidisciplinary Eval. 2006;3:124–33.

Smith NL, Brandon PR. Fundamental issues in evaluation. New York: Guilford; 2008.

Committee on Criteria for Federal Support of Research and Development, National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine, National Research Council. Allocating federal funds for science and technology. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 1995.

Busse R, Fleming I. A critical look at cardiovascular translational research. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;277:H1655–60.

CAS Google Scholar

Schuster DP, Powers WJ. Translational and experimental clinical research. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Williams; 2005.

Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008;299:211–21.

Robertson D, Williams GH. Clinical and translational science: principles of human research. London: Elsevier; 2009.

Goldblatt EM, Lee WH. From bench to bedside: the growing use of translational research in cancer medicine. Am J Transl Res. 2010;2:1–18.

PubMed Google Scholar

Milloy SJ. Science without sense: the risky business of public health research. In: Chapter 5, Mining for statistical associations. Cato Institute. 2009. http://www.junkscience.com/news/sws/sws-chapter5.html . Retrieved 29 Oct 2009.

Gawande A. The cancer-cluster myth. The New Yorker, 8 Feb 1999, p. 34–37.

Kerlinger F. [Chapter 2: problems and hypotheses]. In: Foundations of behavioral research 3rd edn. Orlando: Harcourt, Brace; 1986.

Ioannidis JP. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e124. Epub 2005 Aug 30.

Andersen B. Methodological errors in medical research. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1990.

DeAngelis C. An introduction to clinical research. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990.

Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in medicine. 1st ed. Boston: Little Brown; 1987.

Jekel JF. Epidemiology, biostatistics, and preventive medicine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

Hess DR. Retrospective studies and chart reviews. Respir Care. 2004;49:1171–4.

Wissow L, Pascoe J. Types of research models and methods (chapter four). In: An introduction to clinical research. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990.

Bacchieri A, Della Cioppa G. Fundamentals of clinical research: bridging medicine, statistics and operations. Milan: Springer; 2007.

Wood MJ, Ross-Kerr JC. Basic steps in planning nursing research. From question to proposal. 6th ed. Boston: Jones and Barlett; 2005.

DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, Weinberg RA, DePinho RA. Cancer. Principles and practice of oncology, vol. 1. Philadelphia: Wolters Klewer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research. Applications to practice. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall Health; 2000.

Marks RG. Designing a research project. The basics of biomedical research methodology. Belmont: Lifetime Learning Publications: A division of Wadsworth; 1982.

Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867–72.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, 450 Clarkson Avenue, 1199, Brooklyn, NY, 11203, USA

Phyllis G. Supino EdD

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Phyllis G. Supino EdD .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

, Cardiovascular Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Clarkson Avenue, box 1199 450, Brooklyn, 11203, USA

Phyllis G. Supino

, Cardiovascualr Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Clarkson Avenue 450, Brooklyn, 11203, USA

Jeffrey S. Borer

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Supino, P.G. (2012). Overview of the Research Process. In: Supino, P., Borer, J. (eds) Principles of Research Methodology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3360-6_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3360-6_1

Published : 18 April 2012

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-3359-0

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-3360-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Science, health, and public trust.

September 8, 2021

Explaining How Research Works

We’ve heard “follow the science” a lot during the pandemic. But it seems science has taken us on a long and winding road filled with twists and turns, even changing directions at times. That’s led some people to feel they can’t trust science. But when what we know changes, it often means science is working.

Explaining the scientific process may be one way that science communicators can help maintain public trust in science. Placing research in the bigger context of its field and where it fits into the scientific process can help people better understand and interpret new findings as they emerge. A single study usually uncovers only a piece of a larger puzzle.

Questions about how the world works are often investigated on many different levels. For example, scientists can look at the different atoms in a molecule, cells in a tissue, or how different tissues or systems affect each other. Researchers often must choose one or a finite number of ways to investigate a question. It can take many different studies using different approaches to start piecing the whole picture together.

Sometimes it might seem like research results contradict each other. But often, studies are just looking at different aspects of the same problem. Researchers can also investigate a question using different techniques or timeframes. That may lead them to arrive at different conclusions from the same data.

Using the data available at the time of their study, scientists develop different explanations, or models. New information may mean that a novel model needs to be developed to account for it. The models that prevail are those that can withstand the test of time and incorporate new information. Science is a constantly evolving and self-correcting process.

Scientists gain more confidence about a model through the scientific process. They replicate each other’s work. They present at conferences. And papers undergo peer review, in which experts in the field review the work before it can be published in scientific journals. This helps ensure that the study is up to current scientific standards and maintains a level of integrity. Peer reviewers may find problems with the experiments or think different experiments are needed to justify the conclusions. They might even offer new ways to interpret the data.

It’s important for science communicators to consider which stage a study is at in the scientific process when deciding whether to cover it. Some studies are posted on preprint servers for other scientists to start weighing in on and haven’t yet been fully vetted. Results that haven't yet been subjected to scientific scrutiny should be reported on with care and context to avoid confusion or frustration from readers.

We’ve developed a one-page guide, "How Research Works: Understanding the Process of Science" to help communicators put the process of science into perspective. We hope it can serve as a useful resource to help explain why science changes—and why it’s important to expect that change. Please take a look and share your thoughts with us by sending an email to [email protected].

Below are some additional resources:

- Discoveries in Basic Science: A Perfectly Imperfect Process

- When Clinical Research Is in the News

- What is Basic Science and Why is it Important?

- What is a Research Organism?

- What Are Clinical Trials and Studies?

- Basic Research – Digital Media Kit

- Decoding Science: How Does Science Know What It Knows? (NAS)

- Can Science Help People Make Decisions ? (NAS)

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Scientific Method

Science is an enormously successful human enterprise. The study of scientific method is the attempt to discern the activities by which that success is achieved. Among the activities often identified as characteristic of science are systematic observation and experimentation, inductive and deductive reasoning, and the formation and testing of hypotheses and theories. How these are carried out in detail can vary greatly, but characteristics like these have been looked to as a way of demarcating scientific activity from non-science, where only enterprises which employ some canonical form of scientific method or methods should be considered science (see also the entry on science and pseudo-science ). Others have questioned whether there is anything like a fixed toolkit of methods which is common across science and only science. Some reject privileging one view of method as part of rejecting broader views about the nature of science, such as naturalism (Dupré 2004); some reject any restriction in principle (pluralism).

Scientific method should be distinguished from the aims and products of science, such as knowledge, predictions, or control. Methods are the means by which those goals are achieved. Scientific method should also be distinguished from meta-methodology, which includes the values and justifications behind a particular characterization of scientific method (i.e., a methodology) — values such as objectivity, reproducibility, simplicity, or past successes. Methodological rules are proposed to govern method and it is a meta-methodological question whether methods obeying those rules satisfy given values. Finally, method is distinct, to some degree, from the detailed and contextual practices through which methods are implemented. The latter might range over: specific laboratory techniques; mathematical formalisms or other specialized languages used in descriptions and reasoning; technological or other material means; ways of communicating and sharing results, whether with other scientists or with the public at large; or the conventions, habits, enforced customs, and institutional controls over how and what science is carried out.

While it is important to recognize these distinctions, their boundaries are fuzzy. Hence, accounts of method cannot be entirely divorced from their methodological and meta-methodological motivations or justifications, Moreover, each aspect plays a crucial role in identifying methods. Disputes about method have therefore played out at the detail, rule, and meta-rule levels. Changes in beliefs about the certainty or fallibility of scientific knowledge, for instance (which is a meta-methodological consideration of what we can hope for methods to deliver), have meant different emphases on deductive and inductive reasoning, or on the relative importance attached to reasoning over observation (i.e., differences over particular methods.) Beliefs about the role of science in society will affect the place one gives to values in scientific method.

The issue which has shaped debates over scientific method the most in the last half century is the question of how pluralist do we need to be about method? Unificationists continue to hold out for one method essential to science; nihilism is a form of radical pluralism, which considers the effectiveness of any methodological prescription to be so context sensitive as to render it not explanatory on its own. Some middle degree of pluralism regarding the methods embodied in scientific practice seems appropriate. But the details of scientific practice vary with time and place, from institution to institution, across scientists and their subjects of investigation. How significant are the variations for understanding science and its success? How much can method be abstracted from practice? This entry describes some of the attempts to characterize scientific method or methods, as well as arguments for a more context-sensitive approach to methods embedded in actual scientific practices.

1. Overview and organizing themes

2. historical review: aristotle to mill, 3.1 logical constructionism and operationalism, 3.2. h-d as a logic of confirmation, 3.3. popper and falsificationism, 3.4 meta-methodology and the end of method, 4. statistical methods for hypothesis testing, 5.1 creative and exploratory practices.

- 5.2 Computer methods and the ‘new ways’ of doing science

6.1 “The scientific method” in science education and as seen by scientists

6.2 privileged methods and ‘gold standards’, 6.3 scientific method in the court room, 6.4 deviating practices, 7. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries.

This entry could have been given the title Scientific Methods and gone on to fill volumes, or it could have been extremely short, consisting of a brief summary rejection of the idea that there is any such thing as a unique Scientific Method at all. Both unhappy prospects are due to the fact that scientific activity varies so much across disciplines, times, places, and scientists that any account which manages to unify it all will either consist of overwhelming descriptive detail, or trivial generalizations.

The choice of scope for the present entry is more optimistic, taking a cue from the recent movement in philosophy of science toward a greater attention to practice: to what scientists actually do. This “turn to practice” can be seen as the latest form of studies of methods in science, insofar as it represents an attempt at understanding scientific activity, but through accounts that are neither meant to be universal and unified, nor singular and narrowly descriptive. To some extent, different scientists at different times and places can be said to be using the same method even though, in practice, the details are different.

Whether the context in which methods are carried out is relevant, or to what extent, will depend largely on what one takes the aims of science to be and what one’s own aims are. For most of the history of scientific methodology the assumption has been that the most important output of science is knowledge and so the aim of methodology should be to discover those methods by which scientific knowledge is generated.

Science was seen to embody the most successful form of reasoning (but which form?) to the most certain knowledge claims (but how certain?) on the basis of systematically collected evidence (but what counts as evidence, and should the evidence of the senses take precedence, or rational insight?) Section 2 surveys some of the history, pointing to two major themes. One theme is seeking the right balance between observation and reasoning (and the attendant forms of reasoning which employ them); the other is how certain scientific knowledge is or can be.

Section 3 turns to 20 th century debates on scientific method. In the second half of the 20 th century the epistemic privilege of science faced several challenges and many philosophers of science abandoned the reconstruction of the logic of scientific method. Views changed significantly regarding which functions of science ought to be captured and why. For some, the success of science was better identified with social or cultural features. Historical and sociological turns in the philosophy of science were made, with a demand that greater attention be paid to the non-epistemic aspects of science, such as sociological, institutional, material, and political factors. Even outside of those movements there was an increased specialization in the philosophy of science, with more and more focus on specific fields within science. The combined upshot was very few philosophers arguing any longer for a grand unified methodology of science. Sections 3 and 4 surveys the main positions on scientific method in 20 th century philosophy of science, focusing on where they differ in their preference for confirmation or falsification or for waiving the idea of a special scientific method altogether.

In recent decades, attention has primarily been paid to scientific activities traditionally falling under the rubric of method, such as experimental design and general laboratory practice, the use of statistics, the construction and use of models and diagrams, interdisciplinary collaboration, and science communication. Sections 4–6 attempt to construct a map of the current domains of the study of methods in science.

As these sections illustrate, the question of method is still central to the discourse about science. Scientific method remains a topic for education, for science policy, and for scientists. It arises in the public domain where the demarcation or status of science is at issue. Some philosophers have recently returned, therefore, to the question of what it is that makes science a unique cultural product. This entry will close with some of these recent attempts at discerning and encapsulating the activities by which scientific knowledge is achieved.

Attempting a history of scientific method compounds the vast scope of the topic. This section briefly surveys the background to modern methodological debates. What can be called the classical view goes back to antiquity, and represents a point of departure for later divergences. [ 1 ]

We begin with a point made by Laudan (1968) in his historical survey of scientific method:

Perhaps the most serious inhibition to the emergence of the history of theories of scientific method as a respectable area of study has been the tendency to conflate it with the general history of epistemology, thereby assuming that the narrative categories and classificatory pigeon-holes applied to the latter are also basic to the former. (1968: 5)

To see knowledge about the natural world as falling under knowledge more generally is an understandable conflation. Histories of theories of method would naturally employ the same narrative categories and classificatory pigeon holes. An important theme of the history of epistemology, for example, is the unification of knowledge, a theme reflected in the question of the unification of method in science. Those who have identified differences in kinds of knowledge have often likewise identified different methods for achieving that kind of knowledge (see the entry on the unity of science ).

Different views on what is known, how it is known, and what can be known are connected. Plato distinguished the realms of things into the visible and the intelligible ( The Republic , 510a, in Cooper 1997). Only the latter, the Forms, could be objects of knowledge. The intelligible truths could be known with the certainty of geometry and deductive reasoning. What could be observed of the material world, however, was by definition imperfect and deceptive, not ideal. The Platonic way of knowledge therefore emphasized reasoning as a method, downplaying the importance of observation. Aristotle disagreed, locating the Forms in the natural world as the fundamental principles to be discovered through the inquiry into nature ( Metaphysics Z , in Barnes 1984).

Aristotle is recognized as giving the earliest systematic treatise on the nature of scientific inquiry in the western tradition, one which embraced observation and reasoning about the natural world. In the Prior and Posterior Analytics , Aristotle reflects first on the aims and then the methods of inquiry into nature. A number of features can be found which are still considered by most to be essential to science. For Aristotle, empiricism, careful observation (but passive observation, not controlled experiment), is the starting point. The aim is not merely recording of facts, though. For Aristotle, science ( epistêmê ) is a body of properly arranged knowledge or learning—the empirical facts, but also their ordering and display are of crucial importance. The aims of discovery, ordering, and display of facts partly determine the methods required of successful scientific inquiry. Also determinant is the nature of the knowledge being sought, and the explanatory causes proper to that kind of knowledge (see the discussion of the four causes in the entry on Aristotle on causality ).

In addition to careful observation, then, scientific method requires a logic as a system of reasoning for properly arranging, but also inferring beyond, what is known by observation. Methods of reasoning may include induction, prediction, or analogy, among others. Aristotle’s system (along with his catalogue of fallacious reasoning) was collected under the title the Organon . This title would be echoed in later works on scientific reasoning, such as Novum Organon by Francis Bacon, and Novum Organon Restorum by William Whewell (see below). In Aristotle’s Organon reasoning is divided primarily into two forms, a rough division which persists into modern times. The division, known most commonly today as deductive versus inductive method, appears in other eras and methodologies as analysis/synthesis, non-ampliative/ampliative, or even confirmation/verification. The basic idea is there are two “directions” to proceed in our methods of inquiry: one away from what is observed, to the more fundamental, general, and encompassing principles; the other, from the fundamental and general to instances or implications of principles.

The basic aim and method of inquiry identified here can be seen as a theme running throughout the next two millennia of reflection on the correct way to seek after knowledge: carefully observe nature and then seek rules or principles which explain or predict its operation. The Aristotelian corpus provided the framework for a commentary tradition on scientific method independent of science itself (cosmos versus physics.) During the medieval period, figures such as Albertus Magnus (1206–1280), Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), Robert Grosseteste (1175–1253), Roger Bacon (1214/1220–1292), William of Ockham (1287–1347), Andreas Vesalius (1514–1546), Giacomo Zabarella (1533–1589) all worked to clarify the kind of knowledge obtainable by observation and induction, the source of justification of induction, and best rules for its application. [ 2 ] Many of their contributions we now think of as essential to science (see also Laudan 1968). As Aristotle and Plato had employed a framework of reasoning either “to the forms” or “away from the forms”, medieval thinkers employed directions away from the phenomena or back to the phenomena. In analysis, a phenomena was examined to discover its basic explanatory principles; in synthesis, explanations of a phenomena were constructed from first principles.

During the Scientific Revolution these various strands of argument, experiment, and reason were forged into a dominant epistemic authority. The 16 th –18 th centuries were a period of not only dramatic advance in knowledge about the operation of the natural world—advances in mechanical, medical, biological, political, economic explanations—but also of self-awareness of the revolutionary changes taking place, and intense reflection on the source and legitimation of the method by which the advances were made. The struggle to establish the new authority included methodological moves. The Book of Nature, according to the metaphor of Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) or Francis Bacon (1561–1626), was written in the language of mathematics, of geometry and number. This motivated an emphasis on mathematical description and mechanical explanation as important aspects of scientific method. Through figures such as Henry More and Ralph Cudworth, a neo-Platonic emphasis on the importance of metaphysical reflection on nature behind appearances, particularly regarding the spiritual as a complement to the purely mechanical, remained an important methodological thread of the Scientific Revolution (see the entries on Cambridge platonists ; Boyle ; Henry More ; Galileo ).

In Novum Organum (1620), Bacon was critical of the Aristotelian method for leaping from particulars to universals too quickly. The syllogistic form of reasoning readily mixed those two types of propositions. Bacon aimed at the invention of new arts, principles, and directions. His method would be grounded in methodical collection of observations, coupled with correction of our senses (and particularly, directions for the avoidance of the Idols, as he called them, kinds of systematic errors to which naïve observers are prone.) The community of scientists could then climb, by a careful, gradual and unbroken ascent, to reliable general claims.

Bacon’s method has been criticized as impractical and too inflexible for the practicing scientist. Whewell would later criticize Bacon in his System of Logic for paying too little attention to the practices of scientists. It is hard to find convincing examples of Bacon’s method being put in to practice in the history of science, but there are a few who have been held up as real examples of 16 th century scientific, inductive method, even if not in the rigid Baconian mold: figures such as Robert Boyle (1627–1691) and William Harvey (1578–1657) (see the entry on Bacon ).

It is to Isaac Newton (1642–1727), however, that historians of science and methodologists have paid greatest attention. Given the enormous success of his Principia Mathematica and Opticks , this is understandable. The study of Newton’s method has had two main thrusts: the implicit method of the experiments and reasoning presented in the Opticks, and the explicit methodological rules given as the Rules for Philosophising (the Regulae) in Book III of the Principia . [ 3 ] Newton’s law of gravitation, the linchpin of his new cosmology, broke with explanatory conventions of natural philosophy, first for apparently proposing action at a distance, but more generally for not providing “true”, physical causes. The argument for his System of the World ( Principia , Book III) was based on phenomena, not reasoned first principles. This was viewed (mainly on the continent) as insufficient for proper natural philosophy. The Regulae counter this objection, re-defining the aims of natural philosophy by re-defining the method natural philosophers should follow. (See the entry on Newton’s philosophy .)

To his list of methodological prescriptions should be added Newton’s famous phrase “ hypotheses non fingo ” (commonly translated as “I frame no hypotheses”.) The scientist was not to invent systems but infer explanations from observations, as Bacon had advocated. This would come to be known as inductivism. In the century after Newton, significant clarifications of the Newtonian method were made. Colin Maclaurin (1698–1746), for instance, reconstructed the essential structure of the method as having complementary analysis and synthesis phases, one proceeding away from the phenomena in generalization, the other from the general propositions to derive explanations of new phenomena. Denis Diderot (1713–1784) and editors of the Encyclopédie did much to consolidate and popularize Newtonianism, as did Francesco Algarotti (1721–1764). The emphasis was often the same, as much on the character of the scientist as on their process, a character which is still commonly assumed. The scientist is humble in the face of nature, not beholden to dogma, obeys only his eyes, and follows the truth wherever it leads. It was certainly Voltaire (1694–1778) and du Chatelet (1706–1749) who were most influential in propagating the latter vision of the scientist and their craft, with Newton as hero. Scientific method became a revolutionary force of the Enlightenment. (See also the entries on Newton , Leibniz , Descartes , Boyle , Hume , enlightenment , as well as Shank 2008 for a historical overview.)

Not all 18 th century reflections on scientific method were so celebratory. Famous also are George Berkeley’s (1685–1753) attack on the mathematics of the new science, as well as the over-emphasis of Newtonians on observation; and David Hume’s (1711–1776) undermining of the warrant offered for scientific claims by inductive justification (see the entries on: George Berkeley ; David Hume ; Hume’s Newtonianism and Anti-Newtonianism ). Hume’s problem of induction motivated Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) to seek new foundations for empirical method, though as an epistemic reconstruction, not as any set of practical guidelines for scientists. Both Hume and Kant influenced the methodological reflections of the next century, such as the debate between Mill and Whewell over the certainty of inductive inferences in science.

The debate between John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) and William Whewell (1794–1866) has become the canonical methodological debate of the 19 th century. Although often characterized as a debate between inductivism and hypothetico-deductivism, the role of the two methods on each side is actually more complex. On the hypothetico-deductive account, scientists work to come up with hypotheses from which true observational consequences can be deduced—hence, hypothetico-deductive. Because Whewell emphasizes both hypotheses and deduction in his account of method, he can be seen as a convenient foil to the inductivism of Mill. However, equally if not more important to Whewell’s portrayal of scientific method is what he calls the “fundamental antithesis”. Knowledge is a product of the objective (what we see in the world around us) and subjective (the contributions of our mind to how we perceive and understand what we experience, which he called the Fundamental Ideas). Both elements are essential according to Whewell, and he was therefore critical of Kant for too much focus on the subjective, and John Locke (1632–1704) and Mill for too much focus on the senses. Whewell’s fundamental ideas can be discipline relative. An idea can be fundamental even if it is necessary for knowledge only within a given scientific discipline (e.g., chemical affinity for chemistry). This distinguishes fundamental ideas from the forms and categories of intuition of Kant. (See the entry on Whewell .)

Clarifying fundamental ideas would therefore be an essential part of scientific method and scientific progress. Whewell called this process “Discoverer’s Induction”. It was induction, following Bacon or Newton, but Whewell sought to revive Bacon’s account by emphasising the role of ideas in the clear and careful formulation of inductive hypotheses. Whewell’s induction is not merely the collecting of objective facts. The subjective plays a role through what Whewell calls the Colligation of Facts, a creative act of the scientist, the invention of a theory. A theory is then confirmed by testing, where more facts are brought under the theory, called the Consilience of Inductions. Whewell felt that this was the method by which the true laws of nature could be discovered: clarification of fundamental concepts, clever invention of explanations, and careful testing. Mill, in his critique of Whewell, and others who have cast Whewell as a fore-runner of the hypothetico-deductivist view, seem to have under-estimated the importance of this discovery phase in Whewell’s understanding of method (Snyder 1997a,b, 1999). Down-playing the discovery phase would come to characterize methodology of the early 20 th century (see section 3 ).

Mill, in his System of Logic , put forward a narrower view of induction as the essence of scientific method. For Mill, induction is the search first for regularities among events. Among those regularities, some will continue to hold for further observations, eventually gaining the status of laws. One can also look for regularities among the laws discovered in a domain, i.e., for a law of laws. Which “law law” will hold is time and discipline dependent and open to revision. One example is the Law of Universal Causation, and Mill put forward specific methods for identifying causes—now commonly known as Mill’s methods. These five methods look for circumstances which are common among the phenomena of interest, those which are absent when the phenomena are, or those for which both vary together. Mill’s methods are still seen as capturing basic intuitions about experimental methods for finding the relevant explanatory factors ( System of Logic (1843), see Mill entry). The methods advocated by Whewell and Mill, in the end, look similar. Both involve inductive generalization to covering laws. They differ dramatically, however, with respect to the necessity of the knowledge arrived at; that is, at the meta-methodological level (see the entries on Whewell and Mill entries).

3. Logic of method and critical responses

The quantum and relativistic revolutions in physics in the early 20 th century had a profound effect on methodology. Conceptual foundations of both theories were taken to show the defeasibility of even the most seemingly secure intuitions about space, time and bodies. Certainty of knowledge about the natural world was therefore recognized as unattainable. Instead a renewed empiricism was sought which rendered science fallible but still rationally justifiable.

Analyses of the reasoning of scientists emerged, according to which the aspects of scientific method which were of primary importance were the means of testing and confirming of theories. A distinction in methodology was made between the contexts of discovery and justification. The distinction could be used as a wedge between the particularities of where and how theories or hypotheses are arrived at, on the one hand, and the underlying reasoning scientists use (whether or not they are aware of it) when assessing theories and judging their adequacy on the basis of the available evidence. By and large, for most of the 20 th century, philosophy of science focused on the second context, although philosophers differed on whether to focus on confirmation or refutation as well as on the many details of how confirmation or refutation could or could not be brought about. By the mid-20 th century these attempts at defining the method of justification and the context distinction itself came under pressure. During the same period, philosophy of science developed rapidly, and from section 4 this entry will therefore shift from a primarily historical treatment of the scientific method towards a primarily thematic one.

Advances in logic and probability held out promise of the possibility of elaborate reconstructions of scientific theories and empirical method, the best example being Rudolf Carnap’s The Logical Structure of the World (1928). Carnap attempted to show that a scientific theory could be reconstructed as a formal axiomatic system—that is, a logic. That system could refer to the world because some of its basic sentences could be interpreted as observations or operations which one could perform to test them. The rest of the theoretical system, including sentences using theoretical or unobservable terms (like electron or force) would then either be meaningful because they could be reduced to observations, or they had purely logical meanings (called analytic, like mathematical identities). This has been referred to as the verifiability criterion of meaning. According to the criterion, any statement not either analytic or verifiable was strictly meaningless. Although the view was endorsed by Carnap in 1928, he would later come to see it as too restrictive (Carnap 1956). Another familiar version of this idea is operationalism of Percy William Bridgman. In The Logic of Modern Physics (1927) Bridgman asserted that every physical concept could be defined in terms of the operations one would perform to verify the application of that concept. Making good on the operationalisation of a concept even as simple as length, however, can easily become enormously complex (for measuring very small lengths, for instance) or impractical (measuring large distances like light years.)

Carl Hempel’s (1950, 1951) criticisms of the verifiability criterion of meaning had enormous influence. He pointed out that universal generalizations, such as most scientific laws, were not strictly meaningful on the criterion. Verifiability and operationalism both seemed too restrictive to capture standard scientific aims and practice. The tenuous connection between these reconstructions and actual scientific practice was criticized in another way. In both approaches, scientific methods are instead recast in methodological roles. Measurements, for example, were looked to as ways of giving meanings to terms. The aim of the philosopher of science was not to understand the methods per se , but to use them to reconstruct theories, their meanings, and their relation to the world. When scientists perform these operations, however, they will not report that they are doing them to give meaning to terms in a formal axiomatic system. This disconnect between methodology and the details of actual scientific practice would seem to violate the empiricism the Logical Positivists and Bridgman were committed to. The view that methodology should correspond to practice (to some extent) has been called historicism, or intuitionism. We turn to these criticisms and responses in section 3.4 . [ 4 ]