Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, the graduate.

Now streaming on:

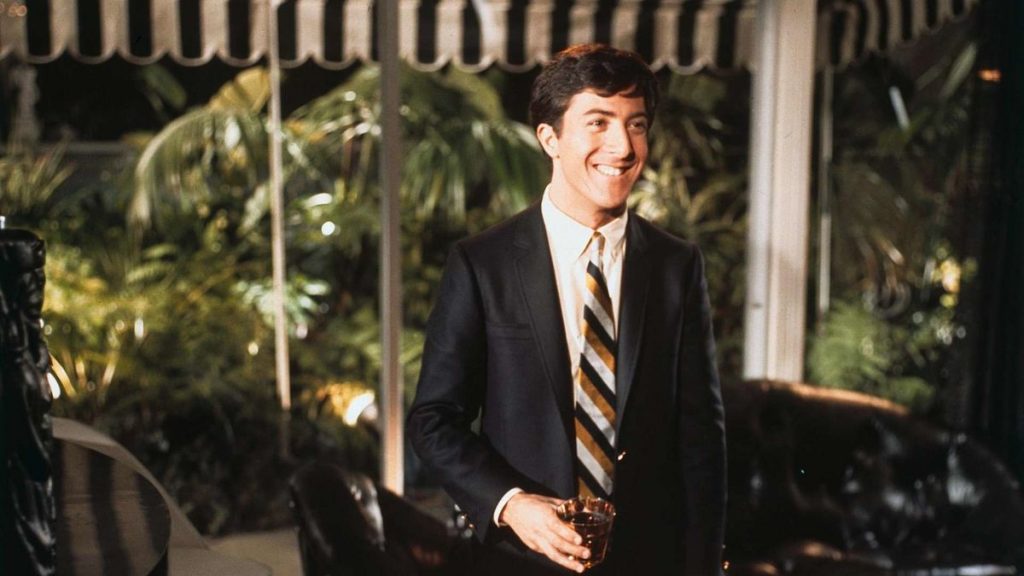

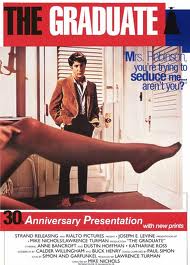

Well, here *is* to you, Mrs. Robinson: You've survived your defeat at the hands of that insufferable creep, Benjamin, and emerged as the most sympathetic and intelligent character in "The Graduate.'' How could I ever have thought otherwise? What murky generational politics were distorting my view the first time I saw this film? Watching the 30th anniversary revival of "The Graduate'' is like looking at photos of yourself at an old fraternity dance. You're gawky and your hair is plastered down with Brylcreem, and your date looks as if you found her behind the counter at the Dairy Queen. But--who's the babe in the corner? The great-looking brunette with the wide-set eyes and the full lips and the knockout figure? Hey, it's the chaperone! Great movies remain themselves over the generations; they retain a serene sense of their own identity. Lesser movies are captives of their time. They get dated and lose their original focus and power. "The Graduate'' (I can see clearly now) is a lesser movie. It comes out of a specific time in the late 1960s when parents stood for stodgy middle-class values, and "the kids'' were joyous rebels at the cutting edge of the sexual and political revolutions. Benjamin Braddock ( Dustin Hoffman ), the clueless hero of "The Graduate,'' was swept in on that wave of feeling, even though it is clear today that he was utterly unaware of his generation and existed outside time and space (he seems most at home at the bottom of a swimming pool).

"The Graduate,'' released in 1967, contains no flower children, no hippies, no dope, no rock music, no political manifestos and no danger. It is a movie about a tiresome bore and his well-meaning parents. The only character in the movie who is alive--who can see through situations, understand motives, and dare to seek her own happiness--is Mrs. Robinson ( Anne Bancroft ). Seen today, "The Graduate'' is a movie about a young man of limited interest, who gets a chance to sleep with the ranking babe in his neighborhood, and throws it away in order to marry her dorky daughter.

Consider, for a moment, the character of Elaine ( Katharine Ross ), Mrs. Robinson's daughter. She has no dialogue of any depth. She has an alarming fetish for false eyelashes. She agrees to marry a tall, blond jock ( Brian Avery ) mostly because her parents will be furious with her if she doesn't. She is so witless that she misunderstands everything Benjamin says to her. When she discovers Benjamin has slept with her mother, she is horrified, but before they have ever had a substantial conversation about the subject, she has forgiven him--apparently because Mrs. Robinson is so hateful that it couldn't have been Benjamin's fault. She then escapes from the altar at her own wedding to flee with Benjamin on a bus, where they look at each other nervously, perhaps because they are still to have a meaningful conversation.

As Benjamin and Elaine escaped in that bus at the end of "The Graduate,'' I cheered, the first time I saw the movie. What was I thinking of? What did the scene celebrate? "Doing your own thing,'' I suppose.

Occasionally I will meet an almost-adult son of friends, and notice that he behaves like a mute savage in company, responding to conversation with grunts and inarticulate syllables. This behavior is usually accompanied by uncoordinated lurches, as if he is behind the wheel of a body too big for him to drive. A few years pass, and this creature regains the use of his brain and speech, and I see that he was passing through a phase. Does he look back on his earlier years in embarrassment? Today, looking at "The Graduate,'' I see Benjamin not as an admirable rebel, but as a self-centered creep whose put-downs of adults are tiresome. (Anyone with average intelligence should have known, in 1967, that the word "plastics'' contained valuable advice--especially valuable for Benjamin, who lacks creative instincts and is destined to become a corporate drudge.) Mrs. Robinson is the only person in the movie who is not playing old tapes. She is bored by a drone of a husband, she drinks too much, she seduces Benjamin not out of lust but out of kindness or desperation. Makeup and lighting are used to make Anne Bancroft look older (she was 36 when the movie was made, and Hoffman was 30). But there is a scene where she is drenched in a rainstorm; we can see her face clearly and without artifice, and she is a great beauty. She is also sardonic, satirical and articulate--the only person in the movie you would want to have a conversation with.

When the movie was first released, I wrote of the "instantly forgettable'' songs by Simon and Garfunkel. History has proven me wrong. They are not forgettable. But what are they telling us? The liberating power of rock and roll is shut out of the soundtrack ("The Sound of Music'' plays on Muzak at one crucial point). The S&G songs are melodic, sophisticated, safe. They even accommodate the action, halting their lyrics and providing guitar chords to underline key moments. This is Benjamin's music; Mrs. Robinson, alone with her vodka, would twist the radio dial looking for the Beatles or Chuck Berry.

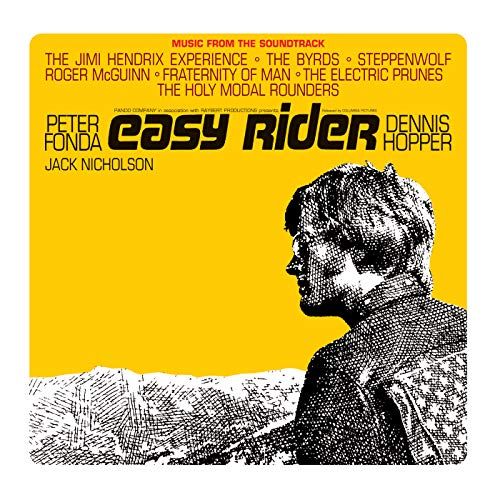

Is "The Graduate'' a bad movie? Not at all. It is a good topical movie whose time has passed, leaving it stranded in an earlier age. I give it three stars out of delight for the material it contains; to watch it today is like opening a time capsule. To know that the movie once spoke strongly to a generation is to understand how deep the generation gap ran during that extraordinary time in the late 1960s. There were true rebels in movies of the period (see "Easy Rider"), but Benjamin Braddock was not one of them. I wonder how long it took him to get into plastics.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

Now playing

Steve! (Martin): A Documentary in Two Pieces

Brian tallerico.

Sleeping Dogs

In the Land of Saints and Sinners

The Greatest Hits

Matt zoller seitz.

Amelia’s Children

Simon abrams.

Film Credits

The Graduate (1967)

106 minutes

Katharine Ross as Elaine Robinson

Murray Hamilton as Mrs. Braddock

Anne Bancroft as Mrs. Robinson

Brian Avery as Carl Smith

William Daniels as Mr. Braddock

Dustin Hoffman as Benjamin Braddock

Buck Henry as Room Clerk

- Mike Nichols-Lawrence Turman

Directed by

- Mike Nichols

From a screenplay by

- Calder Willingham

Screenplay by

Latest blog posts.

Ape Shall Not Kill Ape: A Look at the Entire Apes Franchise

Criterion Celebrates the Films That Forever Shifted Our Perception of Kristen Stewart

The Estate of George Carlin Destroys AI George Carlin in Victory for Copyright Protection (and Basic Decency)

The Future of the Movies, Part 3: Fathom Events CEO Ray Nutt

Film Review: ‘The Graduate’

By A.D. Murphy

A.D. Murphy

- Domestic B.0. sizzles in record July 31 years ago

- $203.5 mil week makes B.O. history 31 years ago

- ‘Park’ propels June to new high 31 years ago

“ The Graduate ” is a delightful, satirical comedy-drama about a young man’s seduction by an older woman, and the measure of maturity which he attains from the experience. Anne Bancroft, Katharine Ross and relative newcomer Dustin Hoffman head a very competent cast. Mike Nichols directed in modern, uptight fashion, which wears well for two-thirds of the pic, and producer Lawrence Turman has supplied all the necessary props of a materialistic society. The young market, particularly, will dig this Embassy release (overseas, United Artists) and older audiences also will be amused. Strong b.o. prospects are likely in initial exclusive bookings, as a setup for a hotsy general playoff.

An excellent screenplay by Calder Willingham and comedy specialist Buck Henry, based on the Charles Webb novel, focuses on Hoffman, just out of college and wondering what it’s all about. Predatory Miss Bancroft, wife of Murray Hamilton, introduces Hoffman to mechanical sex, reaction to which evolves into true love with Miss Ross, Miss Bancroft’s daughter.

Had the story been told in terms of straight drama, it would have been one of those boring modern mellers — the hippie equivalent of a woman’s pic — in which vacant stares are supposed to convey emotion and plot action, and jazzed up cinematics become obvious and pretentious. To be sure, Nichols, in his second feature film, has laid on, with a trowel, most of the current gimmicks, but, thanks to a strong script, they are not noticeable for most of the film.

In the 70 minutes which elapse from Hoffman’s arrival home from school to the realization by Miss Ross that he has had an affair with her mother, pic is loaded with hilarious comedy and, because of this, the intended commentary on materialistic society is most effective. Only in retrospect does one realize a basic, but not overly damaging, flaw: Hoffman’s achievements in school are not credible in light of his basic shyness. No matter, or not much, anyway.

Miss Bancroft, feline and slinky in a manner very much like Lauren Bacall, is excellent, as is Miss Ross, an exciting, fresh actress from the Universal stable, who has a long career ahead of her. Hoffman is perfect in his role. William Daniels and Elizabeth Wilson play his parents in top fashion. Small, but well-cast, supporting contingent includes co-scripter Henry, as a room clerk.

Only in the final 35 minutes, as Hoffman drives up and down the LA-Frisco route in pursuit of Miss Ross, does film falter in pacing, result of which the switched-on cinematics become obvious, and therefore tiring. Vet cameraman Robert Surtees used Panavision and Technicolor to desired advantage. It would be wrong to say that Surtees has “turned on” to new techniques; more precisely, and more importantly, he is responsive to the desire for a modern look. In other words, he is a professional craftsman.

Richard Sylbert’s production design is outstanding, again. Paul Simon wrote the good songs, sung by Simon & Garfunkel, and Dave Grusin’s incidental music is equally adroit. Sam O’Steen’s editing is sharp, and other technical credits are strong. Count this one a winner for Joseph E. Levine, Turman and Nichols.

- Production: Embassy Pictures release. Director Mike Nichols; Producer Lawrence Turman; Screenplay Calder Willingham, Buck Henry; Camera Robert Surtees; Editor Sam O'Steen; Music Dave Grusin; Art Director Richard Sylbert

- Crew: (Color) Widescreen. Available on VHS, DVD. Original review text from Dec. 18, 1967. Running time: 105 MIN.

- With: Mrs. Robinson - Anne Bancroft Ben Braddock - Dustin Hoffman Elaine Robinson - Katharine Ross Also William Daniels, Murray Hamilton, Elizabeth Wilson, Brain Avery, Walter Brooke, Norman Fell, Elizabeth Fraser, Alice Ghostley, Buck Henry, Marion Lorne.

More From Our Brands

Larry david tried so hard to avoid all emotion on the last day of filming ‘curb your enthusiasm’, abu dhabi will build a $1 billion island dedicated to gaming, nwsl’s red stars move bay fc match to wrigley field, the best loofahs and body scrubbers, according to dermatologists, why the view’s sara haines is m.i.a. this week, verify it's you, please log in.

Log in or sign up for Rotten Tomatoes

Trouble logging in?

By continuing, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes.

Email not verified

Let's keep in touch.

Sign up for the Rotten Tomatoes newsletter to get weekly updates on:

- Upcoming Movies and TV shows

- Trivia & Rotten Tomatoes Podcast

- Media News + More

By clicking "Sign Me Up," you are agreeing to receive occasional emails and communications from Fandango Media (Fandango, Vudu, and Rotten Tomatoes) and consenting to Fandango's Privacy Policy and Terms and Policies . Please allow 10 business days for your account to reflect your preferences.

OK, got it!

Movies / TV

No results found.

- What's the Tomatometer®?

- Login/signup

Movies in theaters

- Opening this week

- Top box office

- Coming soon to theaters

- Certified fresh movies

Movies at home

- Netflix streaming

- Prime Video

- Most popular streaming movies

- What to Watch New

Certified fresh picks

- Monkey Man Link to Monkey Man

- The First Omen Link to The First Omen

- The Beast Link to The Beast

New TV Tonight

- Chucky: Season 3

- Mr Bates vs The Post Office: Season 1

- Fallout: Season 1

- Franklin: Season 1

- Dora: Season 1

- Good Times: Season 1

- Beacon 23: Season 2

Most Popular TV on RT

- Ripley: Season 1

- Sugar: Season 1

- 3 Body Problem: Season 1

- A Gentleman in Moscow: Season 1

- Parasyte: The Grey: Season 1

- Shōgun: Season 1

- We Were the Lucky Ones: Season 1

- The Gentlemen: Season 1

- Palm Royale: Season 1

- Best TV Shows

- Most Popular TV

- TV & Streaming News

Certified fresh pick

- Ripley Link to Ripley

- All-Time Lists

- Binge Guide

- Comics on TV

- Five Favorite Films

- Video Interviews

- Weekend Box Office

- Weekly Ketchup

- What to Watch

Best Movies of 2024: Best New Movies to Watch Now

25 Most Popular TV Shows Right Now: What to Watch on Streaming

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming

Awards Tour

Weekend Box Office Results: Godzilla x Kong Holds Strong

The Most Anticipated Movies of 2024

- Trending on RT

- Play Movie Trivia

The Graduate Reviews

The Graduate engages its audience almost exclusively at the level of events until the grandly satisfying conclusion, when its problems (Benjamin's problems) seem to arrive at a happy solution.

Full Review | Jun 23, 2023

You really can’t miss Bancroft’s iconic performance, but I wouldn’t blame anybody for feeling a bit disappointed by the film itself. The years have not been kind to it and it now seems shallow and overly calculated.

Full Review | Feb 1, 2023

It may not be the most tight-knit script and some key character relationships are underwritten. But anchored by some stellar performances and a great soundtrack, it’s still a lot of fun.

Full Review | Original Score: 4/5 | Aug 21, 2022

I suggest that you see The Graduate for fun, and the hell with the next American cinema coming of age.

Full Review | Aug 10, 2022

Something that any lover of American Cinema should see.

Full Review | Original Score: 5/5 | Jun 6, 2022

It’s hard to say which is best -- the direction, the script, or the performances by Dustin Hoffman, Katherine Ross, and Anne Bancroft. Together they achieve a major American film triumph.

Full Review | Mar 2, 2022

...a striking and thoroughly entertaining effort that boasts one of Hoffman's best performances.

Full Review | Original Score: 3.5/4 | Aug 8, 2021

Even from the opening shot (after the credits), it's apparent that the cinematography and dialogue are tinged with something peculiar and undeniably unique.

Full Review | Original Score: 10/10 | Aug 24, 2020

Still potent, still hilarious.

Full Review | Original Score: 5/5 | Jul 25, 2020

Every cinematic cliche, every formula plot device, every pseudo-intellectual ploy, every sentimental gimmick, every prefabricated, sure-fire boxoffice ingredient designed to empty pocketbooks and dampen hankies is present in this despicable movie.

Full Review | Feb 3, 2020

Pretends to be chic and modern, but its hero is a bewildered young dropout who cannot BEGIN to say what he dislikes about the view from his rubber raft.

Full Review | Jan 30, 2020

Over fifty years after its theatrical release, comedy-drama The Graduate manages to hold up as one of the best films of all time.

Full Review | Original Score: 5/5 | Jan 9, 2020

All this chopped steak is a give-away on the new tone in films; unless the material is thoroughly banal, it isn't considered chic.

Full Review | Jun 19, 2019

Through Dustin Hoffman's star-making performance, through Simon & Garfunkel's now iconic soundtrack, through Mike Nichols' canny direction, The Graduate captures youth at a crossroads like no other film.

Full Review | Original Score: 4/4 | Jun 5, 2019

Even though it captures the look and sound of much of the contemporary California scene so skillfully, The Graduate seems to me basically a copout.

Full Review | Mar 13, 2018

Watching it today I can appreciate the historical significance of The Graduate, and Mike Nichols' direction is sharp and stylish. Yet I'm ambivalent about the film.

Full Review | Jun 27, 2017

If you have never seen it, go; if you have, go again.

Full Review | Original Score: 5/5 | Jun 27, 2017

Its pleasures and wit stand the test of time. Plus the cinematography is flat-out fantastic, like David Hockney's pool paintings made live.

Full Review | Original Score: 5/5 | Jun 23, 2017

One of the finest films of the 1960s remains just as clever, witty and relevant today as it captures the doubts and uncertainties of a generation questioning the values of their parents.

Full Review | Original Score: 5/5 | Jun 22, 2017

A hugely pleasurable film.

ARTS & CULTURE

When ‘the graduate’ opened 50 years ago, it changed hollywood (and america) forever.

The movie about a young man struggling to find his way in the world mesmerized the nation when it debuted

Alec Scott, Photographs by Greg Powers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5c/44/5c4455a2-b588-407c-a46e-3ca7c6bf352d/graduateopenerweb.png)

One day in 1963, a movie producer named Larry Turman came across a first novel by a young Californian. “It had an emotional coloration for me like Harold Pinter,” he says. “The book was funny, but it made you nervous at the same time.” So Turman, now 91 and teaching in the University of Southern California’s film and television program, did something he advises his students never to do: He put up his own money, $1,000, to option the movie rights.

Turman’s impulse buy led to one of the most consequential films ever: The Graduate , released in December 1967. Its success—a gross of almost $105 million, the third-highest at the time—revolutionized Hollywood decision-making over which movies got made, how they were cast and to whom they were marketed. Today, the film seems as subversive as it was 50 years ago, just in different ways.

In the novel, also titled The Graduate , author Charles Webb looks back in anger at the gilded California lifestyle he had as the son of a Pasadena cardiologist. He was only 24 when he published it, and yet the book gave the film not just its main plot points—the graduate’s homecoming, his seduction by Mrs. Robinson, his pursuit of her daughter, Elaine—but also much of its best dialogue.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/c6/c9c65d5a-df1f-475f-83ff-aa16df08ad86/dec2017_c03_prologue.jpg)

In grand Hollywood tradition, the film “almost didn’t get made,” says Turman. “Nobody liked the book.” His fitful search for financing led him to Joseph E. Levine (“the schlockmeister of the world,” Turman says), who put up $3 million. For a director Turman went after Mike Nichols, whose recently dissolved stand-up act with Elaine May had the same mordant streak as the book. Nichols was directing Robert Redford in the Broadway megahit Barefoot in the Park , but after Turman sent him the book, he signed on. Nichols found his screenwriter at a July Fourth pig roast at the Malibu home of Jane Fonda and her husband-to-be, the director Roger Vadim. The 1965 party has become legendary for its somewhat awkward mingling of Old Hollywood icons (Henry Fonda, William Wyler, George Cukor) with the talent that would shortly emerge as the New Hollywood (Jack Nicholson, Dennis Hopper, Jane Fonda’s brother, Peter). Somewhere between the spitted pig and the tented dance floor Nichols encountered Buck Henry, who was writing for the TV spy spoof “Get Smart,” though Henry ended up sharing credit for The Graduate with Calder Willingham, who’d written a failed first script.

In casting the leading man—Benjamin Braddock, described in the book as tall and athletic—Team Turman took its biggest risk. They passed over Redford (“Who’s going to believe Bob Redford as being sexually insecure?” Turman asks) for an unheralded, height-challenged 29-year-old Dustin Hoffman. Nichols and Henry had seen him in a small stage production of Harry, Noon and Night in New York, and Henry said Hoffman “played a crippled German transvestite, and I believed all three, no question.”

Years later, Hoffman recalled telling Nichols, “The character is five-eleven, a track star....It feels like this is a dirty trick, sir.” The director replied, “You mean you’re Jewish, that’s why you don’t think you’re right. Maybe he’s Jewish inside .” More seriously, Nichols, who was also Jewish, later said the casting of Hoffman emphasized Benjamin’s alienation from the WASP world around him. A next-generation director, Steven Soderbergh, said the choice was “the seminal event in the defining of motion picture leading men in the last 50 years.”

The Graduate

Pulsating with the rebellious spirit of the '60s and a haunting score sung by Simon and Garfunkel, The Graduate is truly a "landmark film" (Leonard Maltin).

Turman also cast against type for Mrs. Robinson. “I wanted Doris Day,” for her all-American image, he says. But she passed, so he signed Anne Bancroft, who’d won an Oscar in 1962 as the saintly Anne Sullivan in The Miracle Worker . And for Elaine Robinson, he enlisted Katharine Ross—a brunette, not a California blonde.

Simon & Garfunkel had signed on to write three songs for the film but were too busy to deliver. The editing team inserted “Sound of Silence” and “Scarborough Fair” as placeholders—and left them there. One song was new, though at Nichols’ suggestion Simon made a change: What was to have been a toast to “Mrs. Roosevelt” became “Here’s to you, Mrs. Robinson.” The song became a Number 1 hit in June 1968.

Before The Graduate , film historian Mark Harris has noted, the studios believed “everything should appeal to everyone.” After the film filled theaters for two years, they realized “almost half their paying audience was under 24.” Soon James Bond and John Wayne gave way to Ratso Rizzo and Al Pacino.

The Graduate won an Oscar, for Nichols’ direction, though critical reaction was vehemently mixed. However, a retrospective viewing by Roger Ebert shows that the film is rich enough to be read differently across time. At first he, like most boomer males, got a jolt out of Benjamin’s flight from the Establishment. But for the film’s 30th anniversary, he wrote this: “Here is to you, Mrs. Robinson. You’ve survived your defeat at the hands of that insufferable creep, Benjamin, and emerged as the most sympathetic and intelligent character in The Graduate . How could I ever have thought otherwise?”

The Ascent of Ma’am

Mrs. Robinson had few predecessors but a legion of successors. Here’s a sample of post- Graduate women who pursue younger men onscreen.

Harold and Maude (1971)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/88/e8881fcf-3710-4bd8-9334-a6e652664fa1/dec2017_c19_prologue.jpg)

Maude (Ruth Gordon) in Harold and Maude (1971)

79-year-old gets death-obsessed 20-year-old to lighten up.

Animal House (1978)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/23/de23d2e9-f21e-47ae-b446-1e97285562f0/dec2017_c15_prologue.jpg)

Marion Wormer ( Verna Bloom) in Animal House (1978)

The dean’s wife schools Delta House president Otter.

Class (1983)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/a6/efa6c3e8-4a9c-4a68-8055-31234e02615b/dec2017_c11_prologue.jpg)

Ellen ( Jacqueline Bisset) in Class (1983)

A woman of middle age is stunned to discover her boyfriend is 17.

Bull Durham (1988)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bb/21/bb21a044-bbba-4868-ab3c-28d1deb5ef07/dec2017_c10_prologue.jpg)

Annie Savoy ( Susan Sarandon) in Bull Durham (1988)

Baseball groupie dates ascendant pitcher before falling for aging catcher.

American Pie (1999)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/06/8206a0b2-ff66-4c45-95a5-d8d94255e01e/dec2017_c20_prologue.jpg)

Jeanine Stifler ( Jennifer Coolidge) in American Pie (1999)

A mom and her teen son’s friend find each other on prom night.

How Stella Got Her Groove Back (1998)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3b/b0/3bb04a11-f9d3-4fe9-bc0f-5397804182ab/dec2017_c21_prologue.jpg)

Stella Payne ( Angela Bassett) in How Stella Got Her Groove Back (1998)

Forty-something stockbroker vacations in Jamaica.

What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? (1993)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/03/e9/03e997b0-3304-4a09-bbaa-1b7e6d38eb3f/dec2017_c17_prologue.jpg)

Betty Carver ( Mary Steenburgen) in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? (1993)

Housewife finds temporary diversion in a dying Iowa town.

Thelma & Louise (1991)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/1a/401a9150-0775-408e-a4f8-17b5faa15353/dec2017_c18_prologue.jpg)

Thelma Dickinson ( Geena Davis) in Thelma & Louise (1991)

Woman on the run stops long enough to entertain a young drifter.

Tadpole (2000)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/97/a5977066-ea31-4764-9efe-2b6915b68421/dec2017_c12_prologue.jpg)

Diane Lodder ( Bebe Neuwirth) in Tadpole (2000)

Chiropractor complicates Thanksgiving for her best friend’s 15-year-old stepson.

Kathleen Cleary Jane Seymour in Wedding Crashers (2005) Treasury secretary’s wife stalks her daughter’s suitor.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ad/55/ad550527-b8a4-4eae-9365-9b2ce0ba0828/dec2017_c16_prologue.jpg)

Kathleen Cleary ( Jane Seymour) in Wedding Crashers (2005)

Treasury secretary’s wife stalks her daughter’s suitor.

The Boy Next Door (2015)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/76/fd/76fd4597-acca-492b-8e18-42dfa0391b06/dec2017_c14_prologue.jpg)

Claire Peterson ( Jennifer Lopez) in The Boy Next Door (2015)

Teacher meets neighbor and soon longs for a change of address.

Home Again (2017)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/13/ec/13eccaae-2660-4c30-bc50-c26c66cc6993/dec2017_c13_prologue.jpg)

Alice Kinney ( Reese Witherspoon) in Home Again (2017)

Newly separated mom goes wild for a younger man named Harry.

Get the latest Travel & Culture stories in your inbox.

A Note to our Readers Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

Alec Scott | READ MORE

Alec Scott is a journalist based in San Francisco. He’s written for several publications including the Los Angeles Times and the Guardian .

Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

Or browse by category:

- Get the app

- Movie Reviews

- Best Movie Lists

- Best Movies on Netflix, Disney+, and More

Common Sense Selections for Movies

50 Modern Movies All Kids Should Watch Before They're 12

- Best TV Lists

- Best TV Shows on Netflix, Disney+, and More

- Common Sense Selections for TV

- Video Reviews of TV Shows

Best Kids' Shows on Disney+

Best Kids' TV Shows on Netflix

- Book Reviews

- Best Book Lists

- Common Sense Selections for Books

8 Tips for Getting Kids Hooked on Books

50 Books All Kids Should Read Before They're 12

- Game Reviews

- Best Game Lists

Common Sense Selections for Games

- Video Reviews of Games

Nintendo Switch Games for Family Fun

- Podcast Reviews

- Best Podcast Lists

Common Sense Selections for Podcasts

Parents' Guide to Podcasts

- App Reviews

- Best App Lists

Social Networking for Teens

Gun-Free Action Game Apps

Reviews for AI Apps and Tools

- YouTube Channel Reviews

- YouTube Kids Channels by Topic

Parents' Ultimate Guide to YouTube Kids

YouTube Kids Channels for Gamers

- Preschoolers (2-4)

- Little Kids (5-7)

- Big Kids (8-9)

- Pre-Teens (10-12)

- Teens (13+)

- Screen Time

- Social Media

- Online Safety

- Identity and Community

Explaining the News to Our Kids

- Family Tech Planners

- Digital Skills

- All Articles

- Latino Culture

- Black Voices

- Asian Stories

- Native Narratives

- LGBTQ+ Pride

- Best of Diverse Representation List

Celebrating Black History Month

Movies and TV Shows with Arab Leads

Celebrate Hip-Hop's 50th Anniversary

The graduate, common sense media reviewers.

Influential coming-of-age sex comedy has mature themes.

A Lot or a Little?

What you will—and won't—find in this movie.

Blond, blue-eyed WASP America tacitly indicted for

No one behaves admirably. Feeling hollow and aimle

Ben rams his shoulder into a mob at a church, then

Sex is an ever-present topic. Ben has an affair wi

Infrequent use of, for example, "goddamn," "hell,"

Celebration of elaborate gifts (Alfa Romeo, scuba

Some drinking and smoking. Mrs. Robinson says she'

Parents need to know that The Graduate is a unique classic comedy charting an affair between a young man and a married friend of his parents. Much time is spent on the initial seduction and subsequent clandestine meetings in hotel rooms. Though no graphic depictions of intercourse are shown, there are brief…

Positive Messages

Blond, blue-eyed WASP America tacitly indicted for oblivious privilege. Some may consider Ben's use of a cross in a church blasphemous.

Positive Role Models

No one behaves admirably. Feeling hollow and aimless after college graduation, Ben has an adulterous affair with an older woman, which makes him feel more aimless and hollow. His parents' generation seems unhappy, superficial, and devoted to material things. At best, Ben seeks more meaning in life, but even when he wins Elaine, their living meaningful lives happily is far from assured. Mrs. Robinson is a self-described alcoholic who seduces her friends' son. Breaking and entering, stalking, going by an assumed name, and premarital pregnancy all featured.

Violence & Scariness

Ben rams his shoulder into a mob at a church, then grabs a large cross on the wall and wields it threateningly to keep the crowd back. Once outside, he uses the cross to bar the door.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Violence & Scariness in your kid's entertainment guide.

Sex, Romance & Nudity

Sex is an ever-present topic. Ben has an affair with a married woman, then falls in love with her daughter. Mrs. Robinson, in bra, unbuttons Ben's shirt as he lies in bed, then rubs his bare chest. A few seconds of the nude Mrs. Robinson are on display. A topless dancer at a bar is covered only by tassels on her nipples while she does a seductive dance for several seconds.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Sex, Romance & Nudity in your kid's entertainment guide.

Infrequent use of, for example, "goddamn," "hell," and "ass" and the epithet "wop."

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Language in your kid's entertainment guide.

Products & Purchases

Celebration of elaborate gifts (Alfa Romeo, scuba gear).

Drinking, Drugs & Smoking

Some drinking and smoking. Mrs. Robinson says she's an alcoholic.

Did you know you can flag iffy content? Adjust limits for Drinking, Drugs & Smoking in your kid's entertainment guide.

Parents Need to Know

Parents need to know that The Graduate is a unique classic comedy charting an affair between a young man and a married friend of his parents. Much time is spent on the initial seduction and subsequent clandestine meetings in hotel rooms. Though no graphic depictions of intercourse are shown, there are brief shots of female nudity during the seduction and later in a nightclub scene, where a woman strips down to underwear and pasties. Language is fairly restrained, with a few minor curse words, such as "ass" or "damn" used sparingly. Many of the adults drink alcohol and smoke cigarettes very casually. To stay in the loop on more movies like this, you can sign up for weekly Family Movie Night emails .

Where to Watch

Videos and photos.

Community Reviews

- Parents say (14)

- Kids say (20)

Based on 14 parent reviews

Classical Film: Best Viewed Age 16+

Mature themes appropriate for college kids or adults, what's the story.

In THE GRADUATE, after Benjamin Braddock ( Dustin Hoffman ) leaves college, he's disinterested in everything, career-related or not. A family friend, Mrs. Robinson ( Anne Bancroft ), propositions him with an offer of casual sex. The affair seems to bring Benjamin a certain level of contentment. Soon Ben finds problems with their relationship and develops an interest in the Robinsons' daughter, Elaine ( Katherine Ross ), much to Mrs. Robinson's disapproval.

Is It Any Good?

This intriguing comedy was influential in that the plot seems to build toward an energetic climax, but the actual closing moments are listless, providing little closure. This way of leaving a film open-ended and unsettled, above all else, influenced many of the cinematic treasures of the late 1960s and early 1970s, a period that most look back on as golden days of motion-picture history.

Much has been said about the success and aftershocks of the release of The Graduate in 1967. Certainly its deadpan humor and the main character's palpable sense of unease resonated with audience members steeped in the rising counterculture movement. It stands as a document of an era. The lush soundtrack by Simon and Garfunkel underscores a pervasive melancholy while also giving certain quiet moments an astounding serenity -- a marriage of pop music and film that influenced many later films.

Talk to Your Kids About ...

Families can talk about how well The Graduate has aged. Does Benjamin's lack of direction upon graduating seem applicable today, or is it more reflective of the state of youth in the '60s?

Parents definitely will want to address Ben's complicated relationship with Mrs. Robinson. Does she seem genuinely interested in Benjamin? If not, what might her motives be in seducing him?

Why does Elaine seem to gain appeal for Benjamin when Mrs. Robinson forbids him to see her?

Would you consider this movie to be a classic? Why, or why not?

Movie Details

- In theaters : December 22, 1967

- On DVD or streaming : December 7, 1999

- Cast : Anne Bancroft , Dustin Hoffman , Katharine Ross

- Director : Mike Nichols

- Studio : MGM/UA

- Genre : Comedy

- Run time : 105 minutes

- MPAA rating : PG

- Last updated : April 18, 2023

Did we miss something on diversity?

Research shows a connection between kids' healthy self-esteem and positive portrayals in media. That's why we've added a new "Diverse Representations" section to our reviews that will be rolling out on an ongoing basis. You can help us help kids by suggesting a diversity update.

Suggest an Update

Our editors recommend.

Harold and Maude

Indie Films

Mockumentaries for teens.

Common Sense Media's unbiased ratings are created by expert reviewers and aren't influenced by the product's creators or by any of our funders, affiliates, or partners.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Why Do We Love “The Graduate”?

By Jacob R. Brackman

“We thought we had a commercial picture here, but we didn’t know what we had,” an Embassy Pictures official said to me. He was marvelling at the success of “The Graduate.” Joseph E. Levine, who is the president of Embassy Pictures, and who was in a large financial hole before “The Graduate” started paying off, marvelled, too, in a press release of this spring: “It’s absolutely incredible. There’s no way to describe it. It’s like an explosion, a dam bursting. The business just grows and grows and grows. Wherever we’ve played it, whatever the weather, it’s a sell-out attraction. And people have been coming back two and three times to see it again. I haven’t seen anything like this in all the years I’ve been in the business. . . .” So far, “The Graduate” has been shown in some nine hundred and fifty theatres, in almost as many cities of the United States and Canada, and from early figures the experts can now accurately project the degree of a movie’s long-term success. “The Graduate” has broken house records in about forty per cent of its engagements. In New York, in its first week it broke the house record at each of the two theatres it played in—the Coronet and the Lincoln Art. In its sixth and seventh weeks, it broke both records again. In its first six months, it grossed more than thirty-five million dollars in the nine hundred and fifty theatres—more than two million of it in New York. Whereas most films taper off after an initial spurt, its business continues to swell, just as Mr. Levine indicated; the receipts still haven’t peaked. From its performance thus far, Levine predicts that “The Graduate” will become the highest-grossing film in motion-picture history. Howard Taubman, of the Times , agrees that it will outgross even “The Sound of Music.”

Of course, box-office isn’t the only measure of a motion picture’s success. Like the Beatles, “The Graduate” has met with favor from every level of brow. Critically, it hasn’t been a controversial movie—like, say, “Bonnie and Clyde.” Two or three reviewers greeted it with mild enthusiasm; the rest, even hard-to-please critics, were wild about it. Stanley Kauffmann wrote in the New Republic , “ ‘The Graduate’ gives some substance to the contention that American films are coming of age—of our age. . . . [It is] a milestone in American film history.” It was included in the Ten Best lists of Newsweek , the Saturday Review , Cue , the National Board of Review, and a score of newspapers, including the Times . It won five of the seven Golden Globe Awards (Best Comedy, Best Director, Best Actress in a Comedy, and Best Male and Female Newcomers), was nominated for seven Academy Awards, and won the Oscar for Best Director. It was the subject of an essay question, on pre-marital sex, in a final exam at an Eastern women’s college. Its theme song—“Mrs. Robinson,” by Simon and Garfunkel—reached No. 1 on pop charts. And, as Variety says, the word-of-mouth is fabulous. “The Graduate” seems to have, in the Embassy official’s words, “a very special appeal, on both sides of the generation gap.” Indeed, it seems to have become something of a cultural phenomenon—a nearly mandatory movie experience, which can be discussed in gatherings that cross the boundaries of age and class. It also seems to be one of those propitious works of art which support the theory that we are no longer necessarily two publics—the undiscerning and the demanding—for whom separate kinds of entertainment must be provided. Its sensational profits suggest that Hollywood can have both its cake and its art. Filmmakers of lofty aspirations have long protested that enormous production expenses make it impossible to finance “really good, strong stuff,” because it won’t appeal to enough people to pay for itself. “The Graduate” seems to be telling us that the public has been underrated. Due weight having been given to such factors as economic achievement, popularity at different age and social levels, and critical reception by mass and élite media, it is clearly the biggest success in the history of the movies. Whatever is authentic or meretricious in “The Graduate” must reflect what is authentic or meretricious in our sentiment about its themes, and perhaps even in America’s current conceptions of itself. To some people, this statement will sound absurdly hyperbolic (after all, why set out to go on so about a film comedy?), but my feeling is that we are living in a time when the uses of a Brillo box can be as telling as a State of the Union Message, and that a uniquely celebrated movie may be worth a pretty close look.

I like reading both about movies I’ve seen and about movies I haven’t seen, but I often find myself irritated in the first case by superfluous chunks of expository briefing sprinkled through a text and in the second case by having to pick out and piece together the rudiments of the plot from clues, usually nonsequential, that are buried here and there amid the writer’s own reflections. So, although it’s not necessarily an ideal scheme, I’ll set down here most of what happens in “The Graduate.” Since its television trailer gave away the dénouement, I can include even that with an easy conscience.

The graduate is a young man named Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), who returns home to suburban Los Angeles from an Eastern college for the summer, loaded with credentials of glory, and at loose ends about what to do next. The evening after evening Benjamin’s arrival, his wealthy parents throw a party for their friends, more or less in his honor. Wishing to be left alone with his confusion, Benjamin tries to hide out in his room, away from the verbal cheek-pinching. Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft), the wife of his father’s partner, eventually corners him, and tricks and bullies him into driving her home, escorting her inside, having a drink, and engaging in a disconcertingly intimate conversation. She inveigles him up to her absent daughter’s bedroom, where she takes off her clothes and makes him a standing offer of herself. Benjamin, first miserable and then perfectly frantic through these stampeding events, is saved only by the arrival of Mr. Robinson. The two men have a nightcap together. Mr. Robinson, kindly paternal to the point of senility, urges Benjamin to take out his daughter, Elaine (Katharine Ross), who is now away at Berkeley. Some time later (after we have seen a bit more of Benjamin’s aimlessness and of the amiable obtuseness of his parents and their set), Benjamin telephones Mrs. Robinson. During and after the call, many minutes of comical footage illustrate Benjamin’s halfheartedness, awkwardness, sexual ingenuousness, and, of course, agony. There’s a painful meeting with Mrs. R. in a hotel bar; a long sequence in which Benjamin engages a room under a false name from a clerk who he imagines suspects his designs; a furtive pay-phone call to cement arrangements with Mrs. R.; more funny business underscoring Benjamin’s nervousness as he waits in the trysting room; and, at length, a remarkably unpleasant interview with Mrs. R. when she arrives, obviously intent upon getting down to business without amenities. Benjamin tries to back out at the last minute. Mrs. R. goads him on by suggesting that he is a virgin and is sexually inadequate. In a spirit of defensive anger, he comes across.

For the next few weeks, Benjamin hangs around his house by day—sunning, floating on an air mattress in the back-yard pool, avoiding his father’s questions about plans—and, by night, meets Mrs. R. at the hotel, where they conduct a tense, conversationless affair. Mr. Robinson has meanwhile enlisted Mr. Braddock in his campaign to get Benjamin together with his daughter. Benjamin jokingly brings the subject up with Mrs. R., and she makes him swear never to see Elaine. After Elaine arrives on vacation, however, parental pressure for a friendly date increases, and at last, in order to avoid a threatened Braddock-Robinson soirée, Benjamin does ask her out. Mrs. R. is livid. Elaine appears: the classy embodiment of a college man’s most extravagant fantasies. Benjamin, consummately rude, takes her to a cheap strip joint for a drink. After trying to be pleasant for both of them, Elaine rushes out in tears. Benjamin catches up to her, explains that the date was his parents’ idea, and apologizes. In the next scene, they are eating at a teen-agers’ drive-in, relaxed and chatty. When he drives her home, much later than he had expected to, neither wants to end the evening. The only place around that is still open turns out to be the hotel that Benjamin has been using for his assignations with Mrs. R., and he becomes flustered into a hasty exit when various attendants greet him as Mr. Gladstone. Back in the car, Elaine asks him if he is having an affair with someone. He acknowledges an involvement with a married woman (“with a son”) but says it is decidedly a thing of the past.

The next day, Benjamin drives up to the Robinsons’ house in the rain to pick up Elaine, as they had arranged, but Mrs. R. hops into his car and orders him to drive around the block. When he demurs at her demand that he never see Elaine again, she threatens to tell all. Benjamin stops the car and races back to the Robinsons’ through driving rain. He runs up the stairs and barges into Elaine’s bedroom, and as he begins to tell her how that married woman he’d been having an affair with wasn’t just any married woman, Mrs. Robinson, drenched and haggard-looking, appears in the doorway behind him. Elaine gets the picture and shrieks at him to get out.

Benjamin keeps an eye on her from a distance until she goes back to school, then stews around home for a couple of weeks longer. One day, he announces to his parents that he has decided to marry Elaine, and drives up to Berkeley, where he takes a furnished room and continues to shadow her. After days of espionage, he accosts her on a bus, pretending, with no particular conviction, that he has run into her by accident. Elaine, who is on her way to meet a date at the zoo, converses with him icily . Benjamin doggedly tags along until her date, a blond medical student named Carl Smith, gives him the old brushoff. Shortly thereafter, Elaine shows up unannounced in Benjamin’s room, demanding to know what he is doing in Berkeley after raping her mother. Benjamin tries inarticulately to straighten her out; she screams him down. Late that night, she appears again, and asks for a kiss. Benjamin proposes marriage. After several days of indecision, she tentatively agrees. Then Mr. Robinson, having learned of his family’s plight, shows up at Benjamin’s room, promises to put him behind bars if he ever comes near his wife or his daughter again, and leaves hollering that Benjamin is filth, scum, a degenerate. Too much shouting. The landlord, who took Benjamin for an agitator from the start, orders him out. Elaine has disappeared from her dormitory.

Benjamin drives back to Los Angeles and goes straight to the Robinsons’ house, entering unannounced. Mrs. R. informs him, with glacial cordiality, that Elaine is getting married to Carl Smith, and calls the police to have him arrested as a robber. Benjamin takes off, and embarks upon a three-day mad dash to intercept Elaine at the altar—posing first, in a fraternity-house dining hall and locker room, as a friend of Carl’s, and then, over a pay phone in Santa Barbara, as Carl’s minister uncle. On his way to the church, he runs out of gas. He races the remaining distance on foot, and reaches a glass-enclosed balcony of the church just as the young Smiths are completing their vows. At the moment when the couple kiss, Benjamin begins banging on the glass and crying Elaine’s name. She sees him and, for a protracted moment, walks blankly up the aisle toward him. Then she cries out to him, and everyone springs into action. Benjamin gallops down the stairs, Mr. Robinson runs to the rear of the church to head him off, Elaine fights her way through the crowd, everybody starts screaming. In the melee that ensues, Benjamin elbows Mr. R. in the ribs, knocks him down, and then grabs a cross from the wall and swings it like a mace to ward off the attacking horde. Mrs. R. slaps Elaine across the face, screaming “It’s too late!” Elaine shouts “Not for me!” and runs out with Benjamin. He bars the door with the cross, locking the entire wedding party inside. The two of them—Benjamin grubby from his three-day chase, Elaine immaculate in her bridal gown—run, grinning wildly, across the broad church lawn and hail a passing bus. The last shots show them sitting exhausted and expressionless in the rear seat, oblivious of the stares of their fellow-passengers.

The tensions of the first third of the movie—ending with Benjamin’s phone call to Mrs. Robinson—arise from the question: What is Benjamin going to do with himself? Mike Nichols, the director, handles its exposition boldly, and we are given every reason to expect that what the movie will try to do is answer it. In more general terms, the first part of the film seems to be asking what it means to be a promising young man in America today. What does it add up to now, in this country, to be twenty-one, with a high-quality education behind you and a brilliant future ahead of you? Naturally gifted, with a family of wealth and position to back him up, an impressive degree, a fellowship award, the ability to excel in almost any career he might choose, Benjamin exists, as the film opens, in that condition of voluptuous potentiality which is supposed to define young men. The condition fills him with anguish and confusion. And this is fine material for a story, because what was once a predicament confined to the sons of a tiny élite has become a mass predicament in middle-class America. The shared assumptions about what one will do with oneself no longer hold together. Not only is Benjamin interesting to us because of the predicament he is in; he could not be interesting, and perhaps not even recognizable as a youth, if he weren’t in it. We could no longer be taken with a young man who stood smiling confidently upon the threshold of his future as a doctor or a businessman. Benjamin’s parents and their friends struggled, we can assume, to achieve what hard times had denied their parents. For Benjamin to make their youthful hopes his own would be preposterous. A son can pursue ambitions that his parents cherished and failed to fulfill but not ambitions that they fulfilled and then found wanting. From Benjamin’s vantage point, his parents and their friends exist in a world of murmuring emptiness. Upon his arrival home, he finds himself surrounded by fawning adults who have, in a way that escapes them, made a mess of their lives. He sees himself on the threshold only of making a mess of his own life. In the first segment of the film, Nichols himself occupies this limited vantage point so thoroughly as to make Benjamin’s perceptions his own, and the audience’s. He has managed to translate Benjamin’s vision of adult grotesquerie into such striking cinematic terms that even the most conventional moviegoers are hard pressed to see through Benjamin’s problem along such lines as “Spoiled brat, what’s he bellyaching about? My kid should have it so good!” Nichols’ conception, early in the film, is uncompromisingly anti-adult—perhaps the most anti-adult ever to come out of Hollywood. In the party scene, he uses huge, smothering closeups to impose Benjamin’s claustrophobia on the audience when his parents seek to show him off as part of their panoply of success. Even though Benjamin is in a position to accomplish no more, really, than they have accomplished, the guests claw at him hungrily. A tippler promises Benjamin the single word that will unlock the riddle of his future, draws him out onto the patio, and whispers portentously, “Plastics.” Benjamin seems momentarily stunned. Even, or precisely, through our laughter, something inside us cries out, with him, “No, that cannot be the word! That must be the opposite of the word!” But Benjamin can’t escape the clutches of the people who seem to live by it—except by standing at the dark bottom of his parents’ pool, breathing from a scuba tank.

A quick survey of parents who have seen “The Graduate” has turned up only a few who fancied Benjamin the villain of the piece. (For these, his mother and father were “bad” only insofar as they’d “spoiled” him.) Most, if they didn’t exactly identify themselves with Benjamin, were at least on his side , in an avuncular way. They managed to feel this sympathy by seeing Benjamin’s parents as terribly extreme. Parents who are in life as intellectually vulgar as the Braddocks urged their children to go to the movie and see how lucky they were. (“We aren’t that bad, are we, Andy?”) Actually, Mr. Braddock is a more reasonable figure than the usual suburban stereotype, that Hollywood blending of Jewish and wasp garishness—say, the father from Darien in “Auntie Mame,” who could be ridiculed because of his bigotry. There is some boldness to the disparagement of Braddock’s fatherhood. Braddock stands for nothing readily impugnable; he simply fails to stand for anything worthy of respect. The film condemns him because he is not a fit model, and because his ambitions for his son are misguided. Indeed, no one gives Benjamin any sense of direction, much less inspiration. Had there been a single great teacher—or, for that matter, a great hanger-on—back at his nameless Eastern college, he would not be quite so mopily lost. His adulthood looks bleak largely because his environment offers no decent ideal of adulthood—not even a clue to what that ideal might be.

The question posed in the middle third of the film, which ends when Benjamin realizes he’s in love with Elaine, is: How is he going to get out of his affair with Mrs. Robinson? We know that an entanglement with a married woman—especially one so awful—can come to no good end, and that the movie, in order to resolve itself, is going to have to get Benjamin out of it and into something else. More important, we understand that the whole Robinson episode is but a distraction from the problem of Benjamin’s future—worse than a distraction, though, for it helps make up the very syndrome Benjamin wants no part of. Mechanical sex—a bitchy adultery—is as indispensable to the vacuous suburban scene as a few tall, cool ones hoisted over the hibachi. Mrs. Robinson might be his emblem for the plastic world. Benjamin knows he can devote no attention to mapping out his life as long as he has her to deal with. We feel that “The Graduate” will have to return to its initial theme, which the affair has futilely tried to evade

The question we expect the final third to answer is something like: Will Benjamin find his way back to his initial dilemma, come to terms with it at last, and resolve it? Or, at least, we would expect such a question if we could halt the progress of the film until we were ready to proceed, the way we lay a book down on our lap to mull over what has happened and anticipate what is to come. Luckily for “The Graduate,” film affords no opportunity for immediate reflection, except at the risk of missing out on the ongoing action. For this reason, we must replay movies (or their most interesting parts, anyway) in our minds, and judge them largely in retrospect. We do watch movies in our minds rather as we read books: slow the pace at will to get into a particular scene, or even stop the action to get into a single frame; pause to take stock of what the author is doing to us; turn backward to reëxamine something that we didn’t realize would become important. (Marshall McLuhan might dismiss all this as clinging to linear-text methodologies, but I think most people go over movies this way. A number of film critics, one gathers, try to perform the same mental operations while they are actually watching a film. Not only can they not do it; they keep missing more. They go back mentally to retrieve something, only to discover that they hadn’t fully caught it the first time around.) Many films mellow in leisurely recollection; perhaps a fine film must. But “The Graduate,” although it is terrific fun to watch, begins to fall apart under reflection. The final third, in which the best scenes occur, is able to preoccupy us only as long as light is still flickering on the screen. Just when we have greeted Elaine as the catalytic agent to extricate Benjamin from his distracting entanglement with her mother, just when we have braced ourselves for a renewed confrontation with his future, the film, hurtling relentlessly onward, places terrible obstacles between Benjamin and Elaine. Soon it loses sight of its initial problem entirely The winning of Elaine, which we might properly have regarded as a preliminary step on Benjamin’s road to deliverance, supplants the very question of deliverance. As we watch him driving up to Berkeley from Los Angeles, his Alfa Romeo gliding swiftly across the Bay Bridge, he is changing inside. Suddenly, we see him behaving like a man of absolute purpose—a man who knows what he wants and fights for it. Suddenly, he is overflowing with energy and sense of direction. After moping aimlessly through two-thirds of the picture, he is transformed, through his pursuit of Elaine, into the conventional man, resolved upon his chase. On these terms, his success is assured. Once you really know what you’re after, in the movies, it’s mostly a question of going out and getting it.

Despite its bizarre antecedents, the last few hundred feet of the film have a healthy American quality: Benjamin and his girl racing across a green lawn, he in his chinos and stained windbreaker, weary with work well done, and she in her lovely white wedding dress, looking so pure. And she is pure, as far as we know—the first pure flesh amid the plastic. However unnatural what led up to it may have been, they will have a proper wedding night! The clambering onto the bus filled with good common folk. Off on their honeymoon! “What crazy things happen in—well, America!” Somehow, the elation of the scene is almost untainted by any residue of Benjamin’s confusion, or by the “bad” implications of the relationship. The unseen bourgeois, looking very much like the man who spoke the single word “Plastics,” puts his arm fraternally around our shoulder: “See—the kid just needed a sweet little woman to straighten him out.” And we, perhaps clinging to a last-ditch reservation, ask, “But what about his marrying the daughter on the basis of nothing , after he’d been sleeping with the mother, the wife of his father’s partner, who looks so much like his own mother?” And the voice replies, “Are you talking about these two lovely American kids? Sitting in the bus there? Are you going to try and make something nasty out of that?” “For once,” wrote Stanley Kauffmann, “a happy ending makes us feel happy.”

“The Graduate” engages its audience almost exclusively at the level of events until the grandly satisfying conclusion, when its problems (Benjamin’s problems) seem to arrive at a happy solution. The pace of the film is swift and smooth, but its emotional progress—its movement toward resolution—is deeply illogical. The ending does answer the question: How will Benjamin get to marry Elaine, whom he loves? But this union—indeed, the entire boy-meets-loses-gets-girl theme—shapes into a line of resolution only after “The Graduate” is two-thirds over. At one level, the film proceeds awkwardly, deceptively, through a series of less and less interesting problems, sidestepping difficulties of its own authorship, until it can solve only the least interesting of them. All that remains when the bus drives Benjamin and Elaine off into a presumably roseate adulthood is the bare convention of young love triumphant. The trials that Benjamin seemed to forget once he had fixed upon getting the girl, we, too, are encouraged to forget.

Benjamin’s acquisition of Elaine is not an apt resolution of Charles Webb’s novel “The Graduate,” either—the book from which the movie was adapted—but then Webb doesn’t try to pass it off as one. The book is peculiarly spare for a long piece of fiction, reading more like a scenario treatment than a novel. In the manner of a scenario, Webb’s book tries to float its meanings on the surface of events—on easily visible changes in attitude and setting, and on what characters say rather than on what they think and feel.

In the book, Benjamin’s sudden infatuation with Elaine seems purposely unmotivated. Nothing about her presents a good reason for his falling in love with her. The novel, in dialogue that is omitted from the film, makes this abundantly clear at a number of points. For example:

He nodded. “So,” he said, taking her hand. “We’re getting married then.” “But Benjamin?” she said. “What.” “I can’t see why I’m so attractive to you.” “You just are.” “But why.” “You just are, I said. You’re reasonably intelligent. You’re striking looking.” “Striking?” “Sure.” “My ears are too prominent to be striking looking.” Benjamin frowned at her ears. “They’re all right,” he said.

What was, then, an artful point in the novel is wholly lost in the movie: the fact that Benjamin’s precipitate and (one wants to say “therefore”) consuming love for Elaine makes very little sense. We find ourselves sucked in by a cinematic convention: That’s how people fall in love in the movies; it doesn’t have to make sense. Katharine Ross’s scrumptiousness becomes a more than sufficient cause. Yet because the romance has now grown crucial to the scheme of Benjamin’s life, because we are encouraged to imagine Elaine as the light at the end of his darkness, the film seems suddenly top-heavy. The affair—the preliminary relationship—has been pictured in endless detail; now the love that promises salvation is treated skimpily.

In the film, when Elaine tells Benjamin she doesn’t want him to leave Berkeley until he has “some definite plan,” we appreciate only her coy desire for him to stay—a certain bubble-headed righteousness that Miss Ross makes adorable. In the book, we never overcome the anxiety created in us by Benjamin’s planlessness. Elaine perpetually reminds him, and us, that she is a distraction: “ ‘Well, I just think you’re wasting your time sitting around in this room,’ she said. ‘Or sitting around in a room with me if we got married.’ ” Webb can permit such revealing lines because although he lets his protagonist escape from the essential, he isn’t trying to pretend otherwise. Nichols could not have included Elaine’s keen remark; it is fundamental to his upbeat resolution of the movie that we do not stop to reconsider Elaine’s relation to Benjamin’s anguish about his life. Nichols cannot let us leave the theatre feeling that nothing has changed, so he gives us what he thinks we want by packing the last thirty minutes with passages of tremendous emotional power. The passages begin when Benjamin finds Mr. Robinson waiting in his room (Hoffman’s terrified scream is perfect), and keep coming, all but torrentially, until the final hundred feet of film. Their tension has to do with the horror of confronting brute, implacable stupidity— wrongheadedness —in others. With the over-obvious exception of Benjamin, people all appear to see the world so wackily that, like Benjamin, we have no idea what would be involved in getting them to see it straight. The adults will sacrifice him, and sacrifice Elaine, too. There is no reasoning with them. They cannot “win” (Elaine will obviously get an annulment; the couple can no longer be kept apart), but they will still destroy Benjamin, pointlessly, if they can. If he doesn’t escape with his girl, they’ll crack his head against a pew and have him thrown in jail.

Like Benjamin’s graduation party, the wedding guests are all middle-aged and elderly people. (Don’t kids in California ever get to invite any of their friends?) Benjamin’s creators have thus provided him with an absolutely sound reason for a thinly disguised orgy of parricide—or plain adulticide. If he lit into the congregation without the perfect rationale of self-defense, the scene would appear vengeful, even sadistic. But because the adults’ mindless attack seems to leave him no alternative his aggression seems fitting. The scene takes on overtones of Jesus driving the moneylenders from the temple. An author must manipulate his plot skillfully to legitimize so impermissible a release. Webb swung into his most dramatic pose:

Mr. Robinson drove in toward him and grabbed him around the waist. Benjamin twisted away, but before he could reach Elaine he felt Mr. Robinson grabbing at his neck and then grabbing at the collar of his shirt and pulling him backward and ripping the shirt down his back. He spun around and slammed his fist into Mr. Robinson’s face. Mr. Robinson reeled backward and crumpled into a corner.

Nichols has muted the smash to the face into an elbow to the solar plexus, but Mr. Robinson still lands senseless on the floor, and the scene begins to build to an Oedipal jubilee. If Benjamin could have handled the situation in any other way, or if he had really injured Mr. Robinson (or had killed him), Nichols might have led his young audiences to feel the guilt that lies just beyond, and sometimes mingles with, triumph. But “The Graduate”’s solution aims at gratifying not our understanding of its problems but our insecurities about them. Snatching away the bride at the altar—a pleasing fantasy that has turned up in movies often, at least since “It Happened One Night” and “The Philadelphia Story”—is regenerated by an inspired directorial stroke. Benjamin arrives after —instead of, as in the novel and in previous films, before—the ceremony is over. Benjamin’s crying out to Elaine before the vows would mean simply “Don’t marry him! Marry me!” After the sacramental kiss, his cry means “It doesn’t matter that you married him—or that I slept with your mother! We know what is real!” The chase to the altar puts us in a familiar frame of mind: we forget that the vows are only a ritual; the chase assumes a conventional urgency— maybe he will be too late! Then Nichols craftily steps outside the convention.

The wedding finale has been compared, largely because of its disruptiveness, with the wedding scene in “Morgan!” Yet there was no chance that Morgan would “get” Vanessa Redgrave; his busting up the post-wedding party meant simply that he’d gone over the brink, fallen victim to his unbalanced fantasies. Where Morgan hurts and humiliates no one but himself, Benjamin, like an Ivy League Douglas Fairbanks, outmaneuvers and routs the hostile wedding party. Anyone who has seen “The Graduate” when a fair number of young people were in the audience can have had no doubt about what was happening. Benjamin’s contemporaries aren’t apprehensive about his escaping safely; they stomp and hoot and cheer when he plows into the cluster of parents. And when he starts swinging the cross like a battle-axe they go wild. Hip Negro audiences respond the same way when Sidney Poitier returns the Southern patrician’s genteel slap in “In the Heat of the Night,” or when Jimmy Brown gets to slug a couple of white men—enemy soldiers—in “The Dirty Dozen.” Kids at “The Graduate” can let go because Benjamin kicks hell out of a whole entourage of parents—and with an unassailable motive. As far as I know, no movie has ever shown a black man beating up a white man outside a war setting (though in life it’s not uncommon)—not even in a situation that favors the white man. But one can imagine a screenplay with sufficient art to justify a Negro’s physically humiliating a crowd of dreadful whites. Like Benjamin, he would have to have no choice but the ordinarily forbidden.

Benjamin’s battle for Elaine is so sudden and ferocious that we involve ourselves in it completely. When they finally escape their tormentors, and the tension of the chase is relaxed, our relief is consummate. To Nichols’ credit, he has not permitted “The Graduate” to fade front the screen on a shot of the couple in a clinch, or even on grins of idiotic triumph. They stare blankly ahead, because at last things have stopped happening at a preoccupying clip. Now they have a chance to consider the momentous consequences of what they have done, and the difficulties that lie ahead. This final moment of thoughtfulness—Nichols has painstakingly established the use of full-screen expressionless faces to indicate thought and emotion—lessens only slightly the exuberant tone of his finale. But after the lights go on in the theatre we, for our part, have a chance to realize that Benjamin’s capture of Elaine was, at the outside, a secondary aim. What, after all, is Benjamin going to do with his life? Do we infer from the vigor of his pursuit, and from the conventionality of Elaine, that they will soon be discussing a mortgage on a split-level in Tarzana? That the whole “problem” upon which the film established itself was just a sort of “post-grad blues”—a phase that Benjamin simply had to be jolted out of? Or are these clues illusory? Will Benjamin now, with Elaine in tow, return to grapple with the confusions that unsettled him before the Robinson ladies turned up? These are crucial questions, and “The Graduate” has balked at them. Indeed, Nichols recently told a group of college-newspaper editors that as the movie ends, the real problems are just beginning (we must assume that Benjamin somehow needed Elaine before he could face them), and that the marriage would never work out. Nichols’ remarks were surprising, for none of their pertinent, even crucial extensions come across in his dénouement. The last third of the film implies either that “The Graduate” is about a boy passing through a difficult stage on his way to Normality or that Elaine represents, at best, Benjamin’s cowardly desire to simplify the complex issues of his life-to-be. (At worst, he has fixed upon her as a distraction, exactly as he fixed upon her mother.) The option is hardly satisfactory, so most of the critics have steadfastly ignored the evidence of the text and insisted that Benjamin’s long search for himself arrives at its payoff. The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin , typically, informed us that “The Graduate” is “rooted in the affirmative premise that the young can escape the traps of a society created by their parents.” And Glamour explained Benjamin’s barely controlled hysteria at the wedding by saying, “He doesn’t care what other people think because [now] he knows who he is. That’s growing up.”

The condition of being altogether lost may be unbearable; it is understandable that people usually take false roads out. The false roads don’t lead toward being found, exactly, or toward any particular wisdom, but at least they allow one a comforting feeling of movement, an illusion of progress—at least they consume energy. For an artist to detour onto such roads is also understandable, I suppose; in any event, it happens often enough. Resisting the lure of such detours and remaining still, in stark perplexity, to watch and listen is the nerviest course, in art as in life. The artist cannot afford to let himself get away with things; if he does, he cheats his characters and, consequently, his audience. If he cannot long maintain himself in the condition of being lost, he cannot long maintain his characters in that condition, either, because he has no sure sense of where it leads, or even of what its resolution might look like. He grows adept not at solving problems but at overcoming them—transmuting them, removing them, “settling” them, directing them toward false outcomes. The higher an artist’s distractibility is, the less tenaciously he clings to the essential, and the easier, and emptier, his aesthetic choices become.

Though we all identify European movies by naming their directors, film buffs who refer to American movies that way have seemed a little pedantic. Familiar though we are with the axiom that European auteurs produce unmistakably personal visions, we have seen Hollywood movies, even the movies of our most “distinctive” directors, as committee efforts. “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” was the Burton-Taylor movie or, in certain circles, the Albee movie. But “The Graduate” is, definitively, the Mike Nichols movie. In fact, it has given everybody the chance to be a movie buff; that is, to talk about the director . Even its actors, in interviews, have tried to turn attention away from the themselves toward Nichols. The critics—including some who usually scorn auteur notions—tended overwhelmingly to speak of “The Graduate”’s success in terms of Nichols’ success. Many of them called him a genius. The New York Film Critics and the Motion Picture Academy elected “In the Heat of the Night” Best Picture, but both groups chose Nichols over Norman Jewison (and Arthur Penn) as Best Director. The Directors’ Guild of America also gave Nichols its annual award. John Allen wrote in the Christian Science Monitor , “The director . . . has [hereby] announced his candidacy for election to the upper chamber of filmmakers now occupied by Fellini, Truffaut, Antonioni, and others of their calibre. Mr. Nichols, as a director whose sure control shapes and colors every frame of film with a distinctive, recognizable style, is almost sure of election. . . . Mr. Nichols is everywhere, blending, coloring, illuminating. He gives to ‘The Graduate’ that special brilliance that occurs when all the right lights are filtered through the proper prism: his touch as a director is a veritable chandelier of finely cut crystal.” Will Jones wrote more or less the same thing in the Minneapolis Tribune .” Everybody asks why the Americans don’t make movies the way Europeans do, right? Okay, buddies, here’s European moviemaking done right in the heart of American movieville. Hey, there, Schlesinger, Richardson, Antonioni, Truffaut . . . can little Mikey Nichols come play with your gang? You bet.” Nichols said recently, rather as if biting the hands that had fed him so generously, “Critics are like eunuchs watching a gang-bang. They must truly be ignored.” The fact is that critical hungers have been working in Nichols’ favor. Americans want to feel good about what is being produced here. In the early nineteenth century, when Continental literati scoffed, “Who ever read an American book?,” our critics often fell into a similar aesthetic chauvinism; this or that new author was always promising to take his place beside the European masters. A century later, when American movie pioneers set the pace for the international field, the heirs of those critics were quick to claim cinema as a fully legitimate medium for art. But its rapid industrialization—the demand for “something for everyone,” to insure maximum returns on huge production investments—soon dictated a cinema not of truth or beauty but of wish fulfillment: of prosperity, romance, and moral simplicity. At least since the end of the Second World War, with the flourishing of Italian neo-realism and, later, the French nouvelle vague , American entertainment has been forced back into the shadow of European art. Our cultural insecurity vis-à-vis the Old World is at work again. Oppressed by the confusions of the times, we look for the film genius who will do for us what Rossellini, Visconti, De Sica, Fellini, Antonioni, and Olmi have done for the Italians. It is an immense task, granted, but we cannot afford to accept less from our first mid-century genius. He must give this frazzled country some feeling for itself, for its contradictions and despairs, even as it goes through changes that make the job almost impossible.

Not altogether unlike Benjamin, Nichols has long existed on the verge, in a portentous condition of promise. He had a way of shrugging off his unbroken string of successes (five stage and two Hollywood hits out of seven tries) which made them appear playful warmups for some grand feat of art. Because his mastery over “unworthy vehicles” seemed consummate—because, in other words, he had attempted nothing in the theatre that strained at the limits of his talent—people considered him “better” than anything he had done showed him to be. Nearly every artist secretly thinks of himself in this way, but Nichols’ recent public statements suggests that critical overestimations of “The Graduate” may have momentarily beguiled him into presuming that the quality we are willing to attribute to him can already be found in his work.

Nichols has provided his film with the texture, if not the substance, of contemporaneity. Like “Blow-Up,” and more than any other recent American film, “The Graduate” has the look of today. The Berkeley students look like Berkeley students—not like Berkeley students of a dozen years ago, or like a middle-aged conservative’s nightmare of Berkeley students, or like a pop huckster’s souped-up Berkeley students. (Nichols is reported to have salted his crowd with casting-agency hippies. He evidently has an exceptional eye for extras.) Similarly, his camera has captured the exact appearance of a contingent of senior citizens, a nouveau-riche poolside lawn party, a Berkeley student boarding house, an Ivy League-type locker room, a suburban Los Angeles den. The care that Nichols has devoted to surface reality infuses into familiar personalities and their backgrounds a recognizability uncommon in American films (and virtually nonexistent on television). There’s something thrilling in that accomplishment—something rather like the strange excitement of overhearing one’s name mentioned—but his ability to capture our surroundings gives him an authority he does not merit on the subject of the feelings we experience in them.