An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMJ Open Qual

- v.9(1); 2020

Development and application of ‘systems thinking’ principles for quality improvement

Duncan mcnab.

1 Medical Directorate, NHS Education for Scotland, Glasgow, UK

2 Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom

Steven Shorrock

3 EUROCONTROL, Brussels, Belgium

4 University of the Sunshine Coast Sippy Downs Campus, Sippy Downs, Queensland, Australia

Associated Data

bmjoq-2019-000714supp001.pdf

bmjoq-2019-000714supp002.pdf

Introduction

‘Systems thinking’ is often recommended in healthcare to support quality and safety activities but a shared understanding of this concept and purposeful guidance on its application are limited. Healthcare systems have been described as complex where human adaptation to localised circumstances is often necessary to achieve success. Principles for managing and improving system safety developed by the European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation (EUROCONTROL; a European intergovernmental air navigation organisation) incorporate a ‘Safety-II systems approach’ to promote understanding of how safety may be achieved in complex work systems. We aimed to adapt and contextualise the core principles of this systems approach and demonstrate the application in a healthcare setting.

The original EUROCONTROL principles were adapted using consensus-building methods with front-line staff and national safety leaders.

Six interrelated principles for healthcare were agreed. The foundation concept acknowledges that ‘most healthcare problems and solutions belong to the system’. Principle 1 outlines the need to seek multiple perspectives to understand system safety. Principle 2 prompts us to consider the influence of prevailing work conditions—demand, capacity, resources and constraints. Principle 3 stresses the importance of analysing interactions and work flow within the system. Principle 4 encourages us to attempt to understand why professional decisions made sense at the time and principle 5 prompts us to explore everyday work including the adjustments made to achieve success in changing system conditions.

A case study is used to demonstrate the application in an analysis of a system and in the subsequent improvement intervention design.

Conclusions

Application of the adapted principles underpins, and is characteristic of, a holistic systems approach and may aid care team and organisational system understanding and improvement.

Adopting a ‘systems thinking’ approach to improvement in healthcare has been recommended as it may improve the ability to understand current work processes, predict system behaviour and design modifications to improve related functioning. 1–3 ‘Systems thinking’ involves exploring the characteristics of components within a system (eg, work tasks and technology) and how they interconnect to improve understanding of how outcomes emerge from these interactions. It has been proposed that this approach is necessary when investigating incidents where harm has, or could have, occurred and when designing improvement interventions. While acknowledged as necessary, ‘systems thinking’ is often misunderstood and there does not appear to be a shared understanding and application of related principles and approaches. 4–6 There is a need, therefore, for an accessible exposition of systems thinking.

Systems in healthcare are described as complex. In such systems it can be difficult to fully understand how safety is created and maintained. 7 Complex systems consist of many dynamic interactions between people, tasks, technology, environments (physical, social and cultural), organisational structures and external factors. 8–10 Care system components can be closely ‘coupled’ to other system elements and so change in one area can have unpredicted effects elsewhere with non-linear, cause–effect relations. 11 The nature of interactions results in unpredictable changes in system conditions (such as patient demand, staff capacity, available resources and organisational constraints) and goal conflicts (such as the frequent pressure to be efficient and thorough). 12 13 To achieve success, people frequently adapt to these system conditions and goal conflicts. But rather than being planned in advance, these adaptations are often approximate responses to the situations faced at the time. 14 Therefore, to understand safety (and other emergent outcomes such as workforce well-being) we need to look beyond the individual components of care systems to consider how outcomes (wanted and unwanted) emerge from interactions in, and adaptations to, everyday working conditions. 14

Despite the complexity of healthcare systems, we often appear to treat problems and issues in simple, linear terms. 15–17 In simple systems (eg, setting your alarm clock to wake you up) and many complicated systems (eg, a car assembly production line) ‘cause and effect’ are often linked in a predictable or linear manner. This contrasts sharply with the complexity, dynamism and uncertainty associated with much of healthcare practice. 1 7 18 For example, in a study to evaluate the impact of a comprehensive pharmacist review of patients’ medication after hospital discharge, the linear perspective suggested that this specific intervention would improve the safety and quality of medication regimens and so reduce healthcare utilisation. 19 Unexpectedly the opposite result was observed. The authors suggested that this emergent outcome may have been due to the increased number of interactions with different healthcare professionals increasing the complexity of care resulting in greater anxiety, confusion and dependence on healthcare workers.

Analyses of safety issues in healthcare routinely examine how safety is destroyed or degraded but have surprisingly little to say about how it is created and maintained. In the UK, like many parts of the world, root cause analysis is the recommended method for analysing events with an adverse outcome. 20 At its best, this should take a ‘systems approach’ to identify latent system conditions that interacted and contributed to the event and recommend evidence-based change to reduce the risk of recurrence. 20 However, we find that the results of such analyses are commonly based on linear ‘cause and effect’ assumptions and thinking. 15 16 21 22 Despite allusions to ‘root causes’, investigation approaches have a tendency to focus on single system elements such as people and/or items of equipment, rather than attempting to understand the interacting relationships and dependencies between people and other elements of the sociotechnical system from which safety performance and other outcomes in complex systems emerge. 21 By focusing on components in isolation, proposed improvement interventions risk unintended consequences in other parts of the systems and enhanced performance of the targeted component rather than the overall system. The validity of focusing on relatively infrequent, unwanted events has been questioned as it does not always reveal how wanted outcomes usually occur and may limit our learning on how to improve care. 22

Despite much related activity internationally, the impact of current safety improvement efforts in healthcare is limited. 23–25 Similar to other safety-critical industrial sectors, such as nuclear power or air traffic control, there is a growing realisation in healthcare that exploring how safety is created in complex systems may add value to existing learning and improvement efforts. The European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation (EUROCONTROL), a pan-European intergovernmental air navigation organisation, published a white paper, Systems Thinking for Safety: Ten Principles . 26 This sets out a way of thinking about safety in organisations that aligns with systems thinking and applies ‘Safety-II’ principles, for which there is also growing interest in healthcare. 27 This latter approach attempts to explain and potentially resolve some of the ‘intractable problems’ associated with complex systems such as those found in healthcare, which traditional safety management thinking and responses (termed Safety-I) have struggled to adequately understand and improve on. 28 The Safety-II approach aims to increase the number of events with a positive outcome by exploring and understanding how everyday work is done under different conditions and contexts. This can lead to a more informed appreciation of system functioning and complexity that may facilitate a deeper understanding of safety within systems. 29 30

In this paper, we describe principles for systems thinking in healthcare that have been adapted and contextualised from the themes within the EUROCONTROL ‘Systems Thinking for Safety’ white paper. Our goal was to provide an accessible framework to explore how work is done under different conditions to facilitate a deeper understanding of safety within systems. A case report applying these principles to healthcare systems is described to illustrate systems thinking in everyday clinical practice and how this may inform quality improvement (QI) work.

Adaptation of EUROCONTROL Systems Thinking Principles

A participatory codesign approach 31 was employed with informed stakeholders. 32 33 First, in March 2016, a 1-day systems thinking workshop was held for participants who held a variety of roles in front-line primary care (general practitioners (GP), practice nurses, practice managers and community pharmacists) and National Health Service (NHS) Scotland patient safety leaders ( table 1 ). The relevance and applicability of the EUROCONTROL white paper system principles were explored through presentations and discussion led by two experts in the field (including the original lead author of this document—SS). This was followed by a facilitated small group simulation exercise to apply the 10 principles to a range of clinical and administrative healthcare case studies ( online supplementary appendix 1 ) ( figure 1 ).

Systems Thinking for Everyday Work model.

Characteristics of attendees at Stage 1—‘Systems thinking’ workshop

Supplementary data

Second, two rounds of consensus building using the Questback online survey tool were undertaken with workshop participants in April and July 2016. 34

Finally, in May 2017, two 90 min workshops were held to test and refine the adapted principles with primary and secondary care medical appraisers (experienced medical practitioners with responsibility for the critical review of improvement and safety work performed by front-line peers).

At each stage, feedback was collected and analysed to identify themes related to applicability including wording, merging and missing principles. These themes directed the modification of the original principles and descriptors, which were then used at the next stage of development.

Throughout the process, external guidance and ‘sense-checking’ were provided by a EUROCONTROL human factors expert and lead author of the original systems thinking for safety white paper. While we believe the outputs from this work are generically applicable to all healthcare contexts, we have focused on the primary care setting for pragmatic purposes. The agreed principles are illustrated graphically in the Systems Thinking for Everyday Work (STEW) conceptual model ( figure 1 ), and detailed descriptions are provided in online supplementary appendix 2 .

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design of the study or the adaptation of the principles. The presented case study included a patient in the application of the principles to analyse the system. A service user read and commented on the manuscript and their feedback was incorporated into the final paper.

Systems Thinking for Everyday Work

The STEW principles consist of six inter-related principles ( figure 1 , tables 2 and 3 , online supplementary appendix 2 ). A fundamental, overarching conclusion is that the principles should not be viewed as isolated ideas, but instead as inter-related and interdependent concepts that can aid our understanding of complex work processes to better inform safety and improvement work by healthcare teams and organisations.

Adaptation of Systems Thinking Principles

EUROCONTROL, European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation.

Analysis of GP-based pharmacist work system

GP, general practitioner; STEW, Systems Thinking for Everyday Work.

Foundation concept

The foundation concept acknowledges that ‘ most healthcare problems and solutions belong to the system ’. This emphasises that the aim of applying a systems approach is to improve overall system functioning and not the functioning of one individual component within a system. For example, improving clinical assessments will not improve overall system performance unless patients can access assessments appropriately.

All systems interact with other systems, but out of necessity those analysing the system need to agree boundaries for the analysis. This may mean the GP practice building, a single hospital ward, the emergency department, a pharmacy or nursing home. Despite this, it is important to remember that external factors will influence the system under study and changes may have effects in parts of the system outside the boundary.

Multiple perspectives

Appreciate that people, at all organisational levels and regardless of responsibilities and hierarchical status, are the local experts in the work they do. Exploring the different perspectives held by these people, especially in relation to the other principles, is crucial when analysing incidents and designing and implementing change.

System conditions

Obtaining multiple perspectives allows an exploration of variability in demand and capacity, availability of resources (such as information or physical resources) and constraints (such as guidance that directs work to be performed in a particular way). These considerations can help identify leading indicators of impending trouble by identifying where demand may exceed capacity or where resources may not be available. Multiple perspectives can also help explore how work conditions affect staff well-being (eg, health, safety, motivation, job satisfaction, comfort, joy at work) and performance (eg, care quality, safety, productivity, effectiveness, efficiency).

Interactions and flow

System outputs are dependent on the constantly changing interactions between people, tasks, equipment and the wider environment. Multiple perspectives on system functioning help explore interactions to better understand the effects of actions and proposed changes on other parts of the system. Examining flow of work can help identify how these interactions and the conditions of work contribute to bottlenecks and blockages.

Understand why decisions made sense at the time

This principle directs us that, when looking back on individual, team or organisational decision-making, we should appreciate that people do what makes sense to them based on the system conditions experienced at the time (demand, capacity, resources and constraints), interactions and flow of work. It is easy (and common) to look back with hindsight to blame or judge individual components (usually humans) and recommend change such as refresher training and punitive actions. This must consider why such decisions were made, or change is unlikely to be effective. The same conditions may occur again, and the same decision may need to be made to continue successful system functioning. By exploring why decisions were made, we move beyond blaming ‘human error’ which can help promote a ‘Just Culture’—where staff are not punished for actions that are in keeping with their experience and training and which were made to cope with the work conditions faced at the time. 35

Performance variability

As work conditions and interactions change rapidly and often in an unpredicted manner, people adapt what they do to achieve successful outcomes. They make trade-offs, such as efficiency thoroughness trade-offs, and use workarounds to cope with the conditions they face. In retrospect these could be seen as ‘errors’, but are often adaptations used to cope with unplanned or unexpected system conditions. They result in a difference between work-as-done and work-as-imagined and define everyday work from which outcomes, both good and bad, emerge.

Case report

The included case report describes the practical application of these principles to understand work within a system and the subsequent design of organisational change ( table 3 ). The presented details are a small part of a larger project in which the authors (DM, PB and SL) were involved. The new appointment of a health board employed pharmacist to a general practice had not had the anticipated impact and there had been unexpected effects. The GPs had hoped for a greater reduction in workload quantity, the health board had hoped for increased formulary compliance and there had been increased workload in secondary care.

Traditional ways of exploring this problem may include working backwards from the problem to identify an area for improvement. In this case, further training of the pharmacist may have been suggested and targets may have been introduced in relation to workload or formulary compliance. However, without understanding why the pharmacist worked this way, it is likely any retraining or change would be ineffective. The STEW principles provided a framework to analyse the problem from a systems perspective, understand what influenced the pharmacist’s decisions and explore the effects of these decisions elsewhere in the system. Obtaining multiple perspectives identified that the pharmacist had to trade off between competing goals (productivity vs thoroughness including safety and formulary compliance). The application of the principles identified how pharmacists varied their approach to increase productivity while remaining safe. Learning from this everyday work helped bring work-as-done and work-as-imagined closer and several changes to improve system performance were identified and implemented.

Access to hospital electronic prescribing information

This ensured pharmacists had the information needed to complete the task ( System condition—resources ). It also reduced work in other sectors ( Interactions ) and increased the efficiency of task completion and so reduced delays for patients ( Flow ).

Work scheduling

The timetable for the week was changed to prioritise other prescribing tasks at the start of the week and complete medication reconciliation later in the week ( System condition—capacity/demand ). Through discussion of system conditions, the pharmacist identified that certain discharges took longer to complete, resulted in further contact with the practice (with a resultant increased GP workload) or had an increased risk of patient harm. Discharges that included these factors were prioritised and completed early in the week in attempt to mitigate these problems.

Protocols were changed to have minimum specification to allow local adaptation by pharmacists ( System conditions—constraints ). This supported the pharmacists to employ a variety of responses dependent on the context ( Performance Variability ) which reduced pharmacists’ concerns of blame if they did not follow the protocol ( Understand why decision made sense ). For example, after a short admission where it was unlikely medication was changed, pharmacists did not need to contact secondary care regarding medication not recorded on the discharge letter ( Understand why decision made sense ). If they felt they did have to check, the option of contacting the patient was included. Similarly, the need to contact all patients after discharge was removed. Pharmacists could use other options such as contacting the community pharmacy if more appropriate ( Performance Variability ).

Pharmacist mentoring

Regular GP mentoring sessions were included as pharmacists’ found discussing cases with GPs allowed them to consider the benefits and potential problems of their actions in other parts of the system (Interactions and Performance Variability ). For example, not limiting the number of times certain medication can be issued but instead ensuring practice systems for monitoring are used. This also allowed them to consider when they needed to be more thorough at the expense of efficiency ( Performance Variability ), for example, when there were leading indicators of problems such as high-risk medication.

This paper describes the adaptation and redesign of previously developed system principles for generic application in healthcare settings. The STEW principles underpin and are characteristic of a holistic systems approach. The case report demonstrates application of the principles to analyse a care system and to subsequently design change through understanding current work processes, predicting system behaviour and designing modifications to improve system performance.

We propose that the STEW principles can be used as a framework for teams to analyse, learn and improve from unintended outcomes, reports of excellent care and routine everyday work ‘hassles’. 36 37 The overall focus is on team and organisational learning by, for example, small group discussion to promote a deep understanding of ‘how everyday work is actually done’ (rather than just fixating on things that go wrong). This allows an exploration of the system conditions that result in the need for people to vary how they work; the identification and sharing of successful adaptations and an understanding of the effect of adaptations elsewhere in the system (mindful adaptation). From this, we can decide if variation is useful (and thus support staff in doing this effectively) or unwanted (and system conditions can then be considered to try to damp variation). These discussions can help reconcile work-as-done and work-as-imagined . Although, as conditions change unpredictably, new ways of working will continue to evolve and so we must continue to explore and share learning from everyday work, not just when something goes wrong.

The focus of safety efforts, in incident investigation and other QI activity, is often on identifying things that have gone wrong and implementing change to prevent ‘error’ recurring. 20 The focus is often on the ‘root causes’ of adverse events or categorising events most likely to cause systems to fail (eg, using Pareto charts). 20 38 This linear ‘cause and effect’ thinking can lead to single components, deemed to be the ‘cause’ of the unwanted event or care problem, being prioritised for improvement. Although this may improve the performance of that component it may not improve overall system functioning and, due to the complex interactions in healthcare systems, may generate unwanted unintended consequences. The principles promote examining and treating the relevant system as a whole which may strengthen the way we conduct incident investigation and how we design QI projects.

To successfully align corrective actions or improvement interventions with contributing factors, and therefore ensure actions have the desired effect, a deep understanding of everyday work is essential. 39 Methods such as process mapping are often promoted to explore how systems work which, when used properly, can be a useful method to aid healthcare improvers. To more closely model and understand work-as-done , the STEW principles could be considered to show the influences on components that affect performance such as feedback loops, coupling to other components and internal and external influences.

The STEW principles may also support another commonly used QI method: Plan, Do, Study, Act cycles. 40 It has been suggested that more in-depth work is often required in the planning and study stages of improvement activity, especially when dealing with complex problems. 40 The application of the principles may help explore factors that will influence change (such as resources, interactions with other parts of the systems and personal and organisational goals). Similarly, during the study phase, the principles can help explore how system properties prompted people to act the way they did. This level of understanding can then inform further iterative cycles.

Patient care is often delivered by teams across interfaces of care which further increases complexity. 41 It is estimated that only around half to three-quarters of actions recommended after incident analysis are implemented. 21 Although this is often due to a lack of shared learning and local action plans and involvement of key stakeholders, 21 those investigating such cases may feel unable to influence change in such a complex environment. This may result on a focus on what is perceived as manageable or feasible changes to single processes. Obtaining multiple perspective on work and improvement encourages a team-based approach to learning and change but systems are still required to ensure learning and action plans are shared. Although the principles have been used in incident investigation and to influence organisational change across care interfaces, simply introducing a set of principles alone will not improve the likelihood of the implementation of effective system-level change. 42 43 Training on, and evaluation of, the application of the principles is required.

Understanding how safety is created and maintained must involve more than examining when it fails. Improvement interventions often aim to standardise and simplify current processes. Although these approaches are important, in a resource-limited environment, it will never be possible to implement organisational change to fix all system problems. Even if this was possible, as systems evolve with new treatments and technology, conditions will emerge that have not been considered. To optimise success in complex systems, the contribution of humans to creating safety needs to be explored, understood and enhanced. 44 Human adaptation is always required to ensure safe working and needs to be understood, appreciated and supported. Studying systems using the principles may support workers who make such adaptations to be more mindful of wider system effects.

There is growing interest in healthcare in how we can learn more from how people create safety. The Learning from Excellence movement promotes learning and improvement from the analysis of peer-reported episodes of excellent care and positive deviancy aims to identify how some people excel despite facing the same constraints as others. 36 45 The Safety-II systems approach that influenced these principles is similar in that it focuses on how people help to create safety by adapting to unplanned system factors and interactions.

By understanding why decisions are made, the application of the principles supports the development of a ‘Just Culture’—indeed this was one of EUROCONTROL’s original principles and was incorporated into the principle, ‘Understand why decisions make sense at the time’. A ‘Just Culture’ has been described as ‘a culture of trust, learning and accountability’, where people are willing to report incidents where something has gone wrong, as they know it will inform learning to improve care and not be used to assign blame inappropriately. 35 Our approach aims to avoid unwarranted blame and increase healthcare staff support and learning when something has gone wrong. 46 47 Furthermore, application of the principles may empower staff and patients to not just report incidents but contribute to analysis and become integral parts of the improvement process through coproduction of safer systems. Obtaining the perspective of the patient when applying the principles is critical to understanding and improving systems as they are often the only constant when care crosses interfaces. This type of approach to improvement is strongly promoted and may avoid short-sighted responses to patient safety incidents (eg, refresher training or new protocols) and result in the design of better, and more cost-effective care systems. 48

Alternative methods exist for modelling and understanding complex systems, such as the Functional Resonance Analysis Method, 49 and a complex systems approach is used in accident models such as the Systems Theoretic Accident Modelling and Processes 50 and AcciMAPs. 51 These robust methods for system analysis are difficult for front-line teams to implement without specialised training. 29 The principles, on the other hand, were designed with front-line healthcare workers in order to allow non-experts to be able to adopt this type of thinking to understand and improve systems. The influence of conditions of work, including organisational and external factors, on safety has been appreciated for some time and is included in other models used in healthcare to explore safety in complex systems. 52–54 The Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model is arguably one of the best known systems-based frameworks in healthcare. 53 While this model promotes seeking multiple perspectives to describe the interactions between components, the STEW principles focus on how these interactions influence the way work is done and thus may complement the use of the SEIPS model.

Strength and limitations

Any consensus method can produce an agreed outcome, but that does not mean these are wholly adequate in terms of validity, feasibility or transferability. Only 15 participants were involved in the initial development with 32 more in workshops; however, a wide range of professions with significant patient safety and QI experience were recruited. The appraiser workshop was attended by both primary and secondary care doctors, and other staff groups. Their comments were used to further refine the principles, but no attempt was made to assess their agreement on the importance and applicability of principles. The principles have not been shown in practice to improve performance, and further research and evaluation of their application in various sectors of healthcare is needed.

Systems thinking is essential for examining and improving healthcare safety and performance, but a shared understanding and application of the concept is not well developed among front-line staff, healthcare improvers, leaders, policymakers, the media and the general public. It is a complicated topic and requires an understandable framework for practical application by the care workforce. The developed principles may aid a deeper exploration of system safety in healthcare as part of learning from problematic situations, everyday work and excellent practices. They may also inform more effective design of local improvement interventions. Ultimately, the principles help define what a ‘systems approach’ actually entails in a practical sense within the healthcare context.

Research ethics

Under UK ‘Governance Arrangements for Research Ethics Committees’, ethical research committee review is not required for service evaluation or research which, for example, seeks to elicit the views, experiences and knowledge of healthcare professionals on a given subject area. 55 Similarly ‘service evaluation’ that involves NHS staff recruited as research participants by virtue of their professional roles also does not require ethical review from an established NHS research ethics committee.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all those who contributed to the adaptation of the principles and Michael Cannon for his comments from a service user’s perspective.

Twitter: @duncansmcnab, @pbnes

Contributors: DM, JM and PB conceived the project. SS developed the original principles and led the consensus building workshop. DM and SL collected the data. DM, SL, SS, JM and PB analysed the feedback to adapt the principles. DM drafted the original report and SL, SS and JM revised and agreed on the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon request relating to the stages of the consensus building process.

PERSPECTIVE article

Pivoting from systems “thinking” to systems “doing” in health systems—documenting stakeholder perspectives from southeast asia.

- 1 The George Institute for Global Health, New Delhi, India

- 2 Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3 Prasanna School of Public Health, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India

Applications of systems thinking in the context of Health Policy and Systems Research have been scarce, particularly in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). Given the urgent need for addressing implementation challenges, the WHO Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, in collaboration with partners across five global regions, recently initiated a global community of practice for applied systems thinking in policy and practice contexts within LMICs. Individual one on one calls were conducted with 56 researchers, practitioners & decision-makers across 9 countries in Southeast Asia to elucidate key barriers and opportunities for applying systems thinking in individual country settings. Consultations presented the potential for collaboration and co-production of knowledge across diverse stakeholders to strengthen opportunities by applying systems thinking tools in practice. While regional nuances warrant further exploration, there is a clear indication that policy documentation relevant to health systems will be instrumental in advancing a shared vision and interest in strengthening capacities for applied systems thinking in health systems across Southeast Asia.

Introduction

For more than a decade, there has existed a broad consensus on Systems thinking (ST) offering strong potential, both as a lens and as a set of methods for strengthening health systems ( 1 – 3 ). In the wake of ever-widening health inequities exacerbated by an ongoing pandemic ( 4 ), conflict ( 5 ), and anthropogenic climate change ( 6 ), the case for moving away from reductionist approaches and viewing health systems as complex, adaptive systems is strong.

In recent years, a growing chorus calling for a shift in systems thinking from the current 'research-to practice' model toward an applied research paradigm has gained momentum ( 2 , 7 – 9 ). The implementation of ST tools for overcoming complex healthcare system challenges across knowledge mobilization, workforce planning ( 10 , 11 ), and neglected tropical diseases ( 12 , 13 ), among others, has been promising. However, relative to the widespread endorsement of ST methodologies in disciplines dealing with complex systems [such as engineering, biology, and management ( 14 , 15 )], applications in the context of Health Policy and Systems Research (HPSR) have remained scarce, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

There are reasons for this. Firstly, despite the growing body of literature, resources available for supporting systems thinking implementation in the context of HPSR tend to emphasize conceptual writing with an almost exclusive focus on theoretical, as opposed to practical applications ( 16 , 17 ). Moreover, policymakers often tend to receive abstract problem descriptions from systems scholars rather than tangible assistance and input on what ought to be done ( 18 , 19 ).

Secondly, capacity-building initiatives for applied systems thinking are generally not calibrated well for adapting to existing relationships between internal (individual and organizational) and external (policy and socio-political environment) stakeholder groups across health systems ( 20 ). Long-term implementation of ST within various HPSR contexts requires stakeholders to have more than just knowledge of how ST tools can be applied–an understanding of who wields power over decision-making processes is an important consideration too ( 21 ).

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, little is known about how policymakers actually engage with ST, or how the dynamics of collaboration between multisectoral stakeholder groups facilitate (or hinder) this engagement. Moreover, a lack of documented examples of applied systems thinking within HPSR contexts in LMIC settings further skews policymaker perceptions of ST being largely conceptual and irrelevant for policy implementation ( 22 , 23 ).

Given the need for addressing these lacunae, the WHO Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (WHO AHPSR), in collaboration with partners across five global regions launched a Systems Thinking Accelerator (SYSTAC) in 2021 ( 24 ). Drawing from an outgrowth of learnings from the Systems Thinking for District Health Systems project implementation in Timor Leste, Pakistan, and Botswana, ( 25 ) SYSTAC was operationalized as a global community of practice for applied systems thinking in policy and practice contexts within LMICs.

Over the past year, for defining the initial engagement strategy and developing the project scope for SYSTAC, partner institutes conducted a series of regional consultations. The aim of these consultations was to: (1) Understand the needs of practitioners, researchers, and decision-makers for improving capacities in applied systems thinking across regions, (2) Elucidate key barriers and opportunities for applying systems thinking in specific settings, and (3) Catalog potential actors and initiatives in the region to explore collaborative cross-regional partnerships.

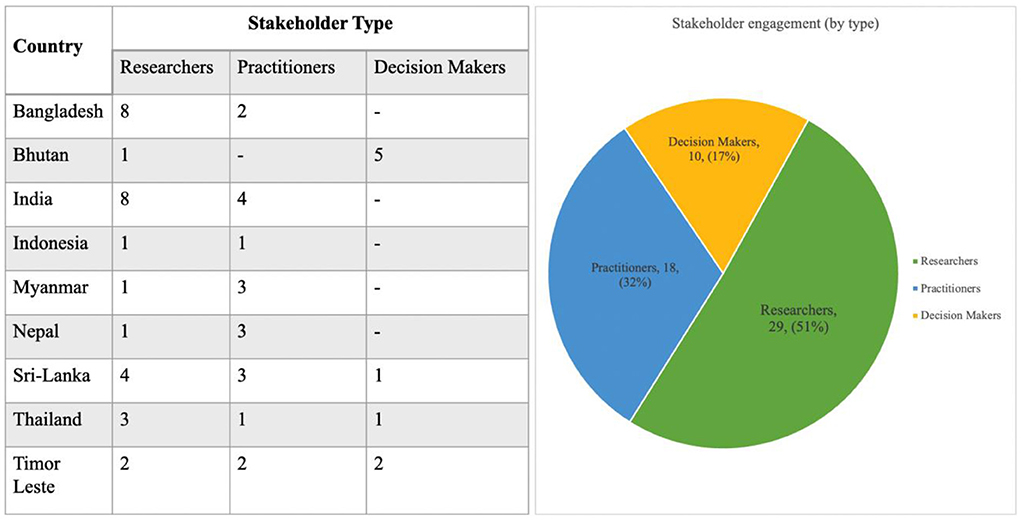

We present here, perspectives gathered through one-on-one virtual consultations with 56 researchers, practitioners, and decision-makers across nine Southeast Asian countries as part of a regional needs assessment, conducted between April 2021 and June 2021 (NB. outreach is still ongoing) ( Figure 1 ). Participants were identified through existing networks, web searches of publications and institutions related to systems thinking, and recommendations of other participants and global SYSTAC network members. Virtual conversations on Zoom were held with participants ranging in duration from 30 min to over an hour and covered understandings of systems thinking, key needs, existing challenges, and future directions for driving a greater implementation of systems thinking across HPSR contexts across the region.

Figure 1 . Stakeholder engagement and outreach statistics.

The need to explore the lexicon of systems thinking in the context of Southeast Asia

Practitioners and researchers from Thailand noted that although there was an overlap between the conceptual understanding of systems thinking, approaches toward it varied across regions. In some cases, there was familiarity with and use of systems thinking, while in others there were approaches using local idioms and terminologies that could be seen to be similar to systems thinking, for example like “ Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” (loosely translated to mean unity in diversity) in Indonesia. This was further corroborated by researchers and decision-makers in Sri Lanka, and Bhutan along with broader literature ( 26 , 27 ).

While certain health reforms across the region [such as Bangladesh's constitutional commitments for social justice ( 28 ) or Bhutan's Gross National Happiness Index ( 29 )] incorporated many of the underlying tenants of systems thinking approaches, they were not intentionally guided by the approach. Instead, these adopted an ethos of commitment to inclusion and broad-based reform, drawing upon tacit knowledge (i.e., not derived from formal research) and cultural nuances (like “ Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” in Indonesia), which, by their nature, involved variations of classic systems thinking methodologies such as network analysis, outcome mapping, etc.

A decision-maker in Timor Leste expressed that while there was an openness to the concept of applied ST in his country, the very term “systems thinking” felt esoteric and made it daunting for broader health systems actors. A small minority of individuals also took the view that the nomenclature of systems thinking, and interrelated concepts–were all in English and predominantly adopted a western approach to implementation which could have (in part) served as an impediment to wide-scale adoption across Southeast Asia.

In the consultations, it became clear that there was a need to explore alternative regional framing similar to applied systems thinking as well as a more explicit theorization of its application in HPSR. A former deputy minister of public health in Thailand, with prior experience using ST tools, suggested introducing the concepts through the lens of “learning health systems” ( 30 ), to “explore synergies with other ongoing health systems strengthening projects across the region.”

The need to strengthen capacities for sustained application of systems thinking in HPSR

Multiple stakeholder groups including practitioners, decision-makers, and researchers across Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Nepal, and Bangladesh expressed interest in engaging with participatory skill-building workshops demonstrating the “how” of applied systems thinking. Access to information and resources including (but not restricted to) webinars, publications, online courses, and research coalitions were identified as means to better understand the scope of applied systems thinking. Support for programming and research in the region was also called for, such that such training would not remain a disembodied, siloed exercise from ongoing regional work.

To advance this, practitioners and researchers from India suggested a potential integration of systems thinking modules into existing HPSR capacity strengthening initiatives such as the Health Innovation Fellowship ( 31 ) and the Health Policy and Systems Research fellowship ( 32 ).

For the sustainable implementation and capacity-strengthening across various contexts, however, the importance of designing a Theory of Change (ToC) ( 33 ) was underscored by multiple stakeholder groups across the region. During these discussions, an explicit emphasis was placed on considerations for delineating the scope (“how far we go”), shared understanding (“what terms we use”), and bespoke implementation strategies (“how we move things”).

The need to demonstrate tangible, policy-relevant benefits of systems thinking approaches to implementers

Consultations with practitioners and researchers from Timor Leste, Myanmar, and Nepal (where adoption of systems thinking continues to be at a relatively nascent stage), reaffirmed that programming within ministries of health tended to default to vertical approaches for problem-solving across health systems. Such approaches, (with a narrow focus and scope) were associated with greater efficiency and higher success ratios. In these contexts, driving the adoption and implementation of systems thinking tools at a policy level continues to pose a challenge. In the absence of a priori high commitment and interest on the part of decision-makers, there was an almost unanimous regional consensus on the need to demonstrate merit in the applicability of ST methodologies in improving community health outcomes relevant to local policy contexts.

While a lot of the discussions during the consultations served as reaffirmations to longstanding implementation challenges of ST tools in HPSR, the findings showcase the potential for collaboration and co-production of knowledge across diverse stakeholder groups for strengthening opportunities for applying systems thinking tools in practice. Going forward, it could be interesting to study the role of collaboration in enhancing the policy-relevance of research outputs. In the context of applying ST in HPSR, understanding the value and uptake of research by policy partners, and strengthening capacities for research via intellectual capital (knowledge) and social capital (relationships) could be an important dimension.

The discussions also shed light on the fact that in many countries across Southeast Asia, ST may have been applied across health strengthening programs under the guise of tacit knowledge and deep-rooted cultural practices. This provides an opportunity to take note of how systems thinking is approached and practiced in different countries, which can help policymakers identify processes that could be replicated. Careful documentation of the contexts undergirding these applications and their impacts on population health outcomes is a crucial next task that must not be overlooked.

One approach for documenting these exemplars could be as part of case book compilations geared toward policymakers. Case compilations in this context could prove useful as the methodology is often recommended for presenting data in a relatively accessible manner ( 34 , 35 ). Due to their focus on localized contexts, these could further assist policymakers in relating to and drawing conclusions from their own experiences. Another component for the widespread accessibility of systems thinking tools and methodologies in the context of HPSR requires a deliberate consideration of challenges posed by the unique linguistic diversity of >2,000 languages ( 36 ) across Southeast Asia. The local translation of content and resource material(s) on systems thinking could prove to be another key supplemental avenue for exploration.

Similar to the ones presented here, insights from stakeholder perspectives gathered across the global regions are being implemented across multiple, ongoing SYSTAC activities. While much remains to be explored, an overarching sentiment of fostering a shared vision and interest in strengthening capacities for applied systems thinking in HPSR across Southeast Asia is evident. Building upon this vision calls for an adherence to the heart of any systems approach–forming networks, maintaining dialogue, and actively pivoting applied systems thinking in health systems from a theory-driven (systems thinking) to an applied research (systems doing) paradigm.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

DN framed, supervised the work, reviewed, and provided feedback. SS wrote the first draft and submitted the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors received funding from the WHO Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research for the needs assessments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening - World Health Organization - Google Books . Available online at: https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=dyydaVwf4WkC&oi=fnd&pg=PA7&dq=Systems+thinking+(ST)+offering+strong+potential,+both+as+a+lens+and+as+a+set+of+methods+for+strengthening+health+systems&ots=MbPvpmp6_-&sig=A46uT60y2EEoeIG0DBqydCrVd0U&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed March 31, 2022).

Google Scholar

2. WHO | Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening . Available online at: https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/systemsthinking/en/ accessed March 31, 2022)

3. Paina L, Peters DH. Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy Plan. (2012) 27:365–73. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr054

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Omukuti J, Barlow M, Giraudo ME, Lines T, Grugel J. Systems thinking in COVID-19 recovery is urgently needed to deliver sustainable development for women and girls. Lancet Planet Heal. (2021) 5:e921–8. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00232-1

5. Kruk ME, Freedman LP, Anglin GA, Waldman RJ. Rebuilding health systems to improve health and promote statebuilding in post-conflict countries: a theoretical framework and research agenda. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 70:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.042

6. Ebi KL, Vanos J, Baldwin JW, Bell JE, Hondula DM, Errett NA, et al. Extreme weather and climate change: population health and health system implications. Annu Rev Public Health . (2021) 42:293–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-012420-105026

7. Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening - World Health Organization - Google Books . Available online at: https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=dyydaVwf4WkC&oi=fnd&pg=PA7&dq=systems+thinking+applied+research+paradigm&ots=MbPvpmq303&sig=axjvD5lYUeou9TM2taizXvSOJcw#v=onepage&q=systemsthinkingappliedresearchparadigm&f=false (accessed April 1, 2022).

8. Henry BC. New paradigm of systems thinking. Int J Econom Finan Manag . (2013) 2:351–5. Available online at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.677.2708&rep=rep1&type=pdf

9. Adam T, De Savigny D. Systems thinking for strengthening health systems in LMICs: need for a paradigm shift. Health Policy Plan . (2012) 27 (Suppl. 4):iv1–3. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs084

10. Manley K, Martin A, Jackson C, Wright T. Using systems thinking to identify workforce enablers for a whole systems approach to urgent and emergency care delivery: a multiple case study. BMC Health Serv Res. (2016) 16:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1616-y

11. Haynes A, Rychetnik L, Finegood D, Irving M, Freebairn L, Hawe P. Applying systems thinking to knowledge mobilisation in public health. Heal Res Policy Syst. (2020) 18:1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00600-1

12. Glenn JD. A systems thinking approach to global governance for neglected tropical diseases. (2018).

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

13. Glenn J, Kamara K, Umar ZA, Chahine T, Daulaire N, Bossert T. Applied systems thinking: a viable approach to identify leverage points for accelerating progress towards ending neglected tropical diseases. Heal Res Policy Syst. (2020) 18, 56. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00570-4

14. Advanced Systems Thinking Engineering and Management - Derek K. Hitchins - Google Books . Available online at: https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=SlxWiudf2g0C&oi=fnd&pg=PR15&dq=systems+thinking+%2B+engineering,+biology+and+management&ots=qWwn3PZpiq&sig=s-qYq_WTKYq8duYEakIm2FWKAhg#v=onepage&q=systemsthinking%2Bengineering%2Cbiologyandmanagement&f=false (accessed April 1, 2022).

15. Rethinking Management Information Systems: An Interdisciplinary Perspective - Google Books . Available online at: https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=QJJE-p5LdG4C&oi=fnd&pg=PA45&dq=systems+thinking+%2B+engineering,+biology+and+management&ots=Wp6ryiGJNB&sig=Tykkuf-apEO9-2Z5ig5pnJnI4RA#v=onepage&q=systemsthinking%2Bengineering%2Cbiologyandmanagement&f=false (accessed April 1, 2022).

16. Carey G, Malbon E, Carey N, Joyce A, Crammond B, Carey A. Systems science and systems thinking for public health: a systematic review of the field. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e009002. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009002

17. Newell B, Tan DT, Proust K. Systems thinking for health system improvement. Syst Think Anal Heal Policy Syst Dev . (2021) 1:17–30. Available online at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/systems-thinking-analyses-for-health-policy-and-systems-development/systems-thinking-for-health-system-improvement/BEACCAAAAE7DC07841DEC2955600730F

18. Geyer R, Cairney P. Handbook on complexity and public policy. 482.

19. Sautkina E, Goodwin D, Jones A, Ogilvie D, Petticrew M, White M, et al. Lost in translation? Theory, policy and practice in systems-based environmental approaches to obesity prevention in the healthy towns programme in England. Health Place . (2014) 29:60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.05.006

20. Prashanth NS, Marchal B, Devadasan N, Kegels G, Criel B. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: a realist evaluation of a capacity building programme for district managers in Tumkur, India. Heal Res Policy Syst. (2014) 12:1–20. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-42

21. Roura M. The social ecology of power in participatory health research. Qual Health Res. (2021) 31:778–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732320979187

22. Haynes A, Garvey K, Davidson S, Milat A. What can policy-makers get out of systems thinking? Policy partners' experiences of a systems-focused research collaboration in preventive health. Int J Heal Policy Manag. (2020) 9:65–76. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2019.86

23. Kwamie A, Ha S, Ghaffar A. Applied systems thinking: unlocking theory, evidence and practice for health policy and systems research. Health Policy Plan. (2021) 36:1715–7. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czab062

24. SYSTAC Global Meeting . Available online at: https://ahpsr.who.int/newsroom/events/2021/11/02/default-calendar/systac-global-meeting (accessed April 1, 2022).

25. Sant Fruchtman C, Khalid MB, Keakabetse T, Bonito A, Saulnier DD, Mupara LM, et al. Digital communities of practice: one step towards decolonising global health partnerships Commentary. BMJ Glob Heal. (2022) 7:8174. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008174

26. Pan X, Valerdi R, Kang R. Systems thinking: a comparison between chinese and western approaches. Procedia Comput Sci. (2013) 16:1027–35. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2013.01.108

27. Zhu Z. Systems approaches: where the east meets the west? World Futures. (1999) 53:253–76. doi: 10.1080/02604027.1999.9972742

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Shafique S, Bhattacharyya DS, Anwar I, Adams A. Right to health and social justice in Bangladesh: Ethical dilemmas and obligations of state and non-state actors to ensure health for urban poor. BMC Med Ethics. (2018) 19:61–9. doi: 10.1186/s12910-018-0285-2

29. Masaki K, Tshering J. Exploring the origins of bhutan's gross national happiness. J South Asian Dev . (2021) 16:273–92. doi: 10.1177/09731741211039049

30. Enticott J, Johnson A, Teede H. Learning health systems using data to drive healthcare improvement and impact: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06215-8

31. TGI India Health Innovation Fellowship | The George Institute for Global Health . Available online at: https://www.georgeinstitute.org/news/tgi-india-health-innovation-fellowship (accessed April 1, 2022).

32. Home - India HPSR Fellowships Programme . Available online at: https://indiahpsrfellowships.org/ (accessed April 1, 2022)

33. Serrat O. Theories of change. Knowl Solut . (2017) 237–43. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-0983-9_24

34. Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2011) 11:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

35. Zainal Z. Case study as a research method. Jurnal Kemanusiaan . (2007) 9:1–6. Available online at: https://jurnalkemanusiaan.utm.my/index.php/kemanusiaan/article/view/165

36. Enfield N. The Languages of Mainland Southeast Asia (Cambridge Language Surveys) . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2021). doi: 10.1017/9781108605618

Keywords: systems thinking, Southeast Asia, health systems, low and middle income countries (LMICs), health policy and systems research (HPSR)

Citation: Srivastava S and Nambiar D (2022) Pivoting from systems “thinking” to systems “doing” in health systems—Documenting stakeholder perspectives from Southeast Asia. Front. Public Health 10:910055. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.910055

Received: 31 March 2022; Accepted: 12 July 2022; Published: 04 August 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Srivastava and Nambiar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Siddharth Srivastava, ssrivastava@georgeinstitute.org.in ; Devaki Nambiar, dnambiar@georgeinstitute.org.in

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Open access

- Published: 26 August 2014

Advancing the application of systems thinking in health

- Taghreed Adam 1

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 12 , Article number: 50 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

59 Citations

22 Altmetric

Metrics details

Peer Review reports

Highlighting the growing significance of systems thinking in health: introducing a new global series

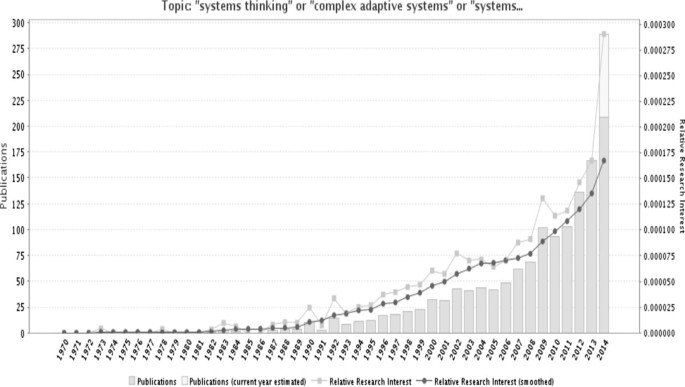

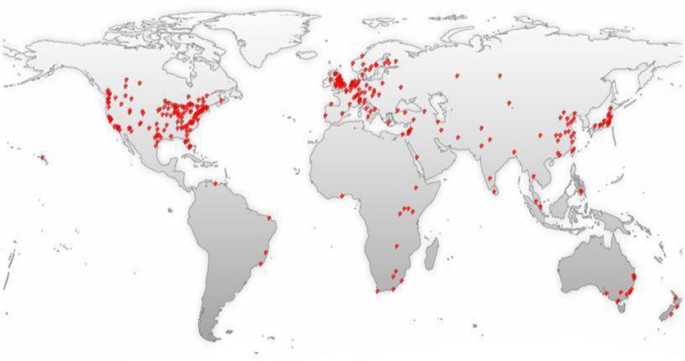

The past two decades have witnessed an increased recognition among global health stakeholders of the importance of systematically considering the complex adaptive nature of health systems to better anticipate some of the unexpected and counterintuitive consequences of implementing current and new policies. This is evidenced by the increased interest in topics such as systems thinking, complex adaptive systems, and systems science in the published health literature over the past 20 years (Figure 1 ). However, the majority of these publications are from high-income countries, while the need for applying these concepts is at least as great in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Figure 2 ). Most of these studies discuss the concepts or make the case for the utility of systems thinking for health systems strengthening; there is still a dearth in practical guidance on how systems thinking concepts, approaches, and tools can be applied in health systems research and practice to reach sustainable solutions [ 1 , 2 ].

Trends in the use of the terms “systems thinking”, “complex adaptive systems”, or “systems science” in the Medline database over the past 40 years. Source: GoPubMed, which reports the frequency that terms appear in MEDLINE indexes for publications, which include titles, abstracts, journal names and corresponding author’s affiliation. Number of publications mentioning these search terms was 1386 as of 14 August 2014.

World map of the 1,386 MEDLINE records mentioning the terms “systems thinking”, “complex adaptive systems”, or “systems science”. Source: GoPubMed, which reports the frequency that terms appear in MEDLINE indexes for publications, which include titles, abstracts, journal names and corresponding author’s affiliation. This data was obtained on 14 August 2014.

Systems thinking is, foremost, a mindset that views systems and their sub-components as intimately interrelated and connected to each other, believing that mastering our understanding of how things work lies in interpreting interrelationships and interactions within and between systems [ 1 , 3 , 4 ]. It is a perspective that deliberately goes beyond events, to look for patterns of behavior and the underlying systemic interrelationships which are responsible for these patterns and their associated events [ 5 ]. It embraces the understanding of open systems as complex adaptive systems that are constantly changing, resistant to change, counter-intuitive, non-linear, and where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts [ 3 ].

The Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (hereafter called the Alliance) has been one of the avid advocates for moving this kind of thinking forward, dedicating a number of activities and resources to promote this field among health practitioners and researchers. First, through its flagship publication on “ Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening ” in 2009 [ 5 ], followed by a Journal Supplement in Health Policy and Planning , in 2012, it has sought to generate better understanding of current practices in applying systems thinking for health systems in LMICs [ 1 ].

The 2012 supplement demonstrated the dearth of applications that explicitly took into account the complexity and dynamics resulting from intervening in health systems, including evaluations of interventions with system-wide effects [ 2 ]. In addition, the very few applications that existed at the time of developing that supplement were predominately from high income countries [ 1 ]. These observations revealed the need for concerted efforts to advance the application of systems thinking in health, particularly in LMICs.

In March 2013, the Alliance, in collaboration with Canada’s International Development Research Centre, launched a Call for papers inviting teams of researchers and health practitioners, with particular focus on lead authorship from LMICs, to develop and share applications of systems thinking methods and approaches, culminating in this Series. This whole program of work, which spanned over two and a half years, provided a great opportunity for strengthening programs, policies, and methods in LMICs to enable researchers and decision makers to think through how systems thinking approaches can be applied to their current health systems questions with practical results.

It is worth noting that, while this collection of articles offers innovative and diverse range of applications of systems thinking approaches, methods, and tools, as the Commentary by Peters illustrates [ 6 ], these applications by no means capture the entire range of relevant tools and approaches that can be applied.

The applicability of a wide range of tools and approaches

This Series illustrates how research approaches that are commonly used in various disciplines, such as realist evaluation, sense-making (as a mental model), or program evaluation theories, can be applied within a systems thinking approach to address complex health systems questions. It does so by showing that the types of questions asked are the most important element that shape the orientation of the analysis, not the tool itself.

For example, in the paper by Prashanth et al. [ 7 ], systems thinking and complex adaptive systems approaches added depth to the realist evaluation by digging deeper into the drivers of, and the context in which the differences in responses of health workers in the two sub-districts were observed and what triggered them. They could show that settings with committed staff and positive intentions to make changes demonstrated more positive outcomes and an ability to use existing opportunities to solve problems and improve performance. Further, that commitment alone was neither crucial nor sufficient as demonstrated by findings from another setting with committed staff but different outcomes. Finally, that in settings with a lack of commitment from staff, strong leadership became more pronounced in driving the change into better outcomes [ 7 ].

Systems thinking and mixed methods

As discussed by Peters and demonstrated by several of the Series papers, both qualitative and quantitative methods contribute in their own way to our understanding of complexity [ 6 , 8 ]. As some of the early systems thinking literature originated from quantitative disciplines such as physics and biology, it may give the impression that relevant systems thinking approaches are predominantly quantitative. Perhaps one of the main contributions of this Series is demonstrating how qualitative methods commonly used in fields such as social science or anthropology add equally important value and depth to analyses of complex health systems questions and phenomena [ 8 – 12 ]. For example, they are often used to provide a profound initial understanding of the problem that can then be complemented by quantitative approaches that incorporate the learning into a more realistic and sophisticated quantitative analysis [ 6 ].

Exploiting the potential of visual interpretations of complex phenomena

During the past decade there has been a revolution of infographics due to the increased recognition of the power of graphics to aid data interpretation and decision making. In this Series, several papers illustrate how a range of graphic tools can help convey complex interpretations and findings in a meaningful visual form, namely causal loop diagrams [ 8 – 12 ], stakeholder network analysis, and sociographs [ 13 , 14 ].

For example, causal loop diagrams used by Rwashana et al. to understand the causes of neonatal mortality in Uganda not only helped analyze and make sense of the different sources of data in a dynamic and iterative way, they were also used to present these complex findings in one main diagram that summarized the relationships, dynamics, and associated factors all in one graph [ 8 ].

Another example of visual interpretations is presented in Malik et al., where they used sociographs to interpret the pattern of advice-seeking behavior among primary health care physicians and the potential explanations for their choices [ 13 ].

Content of the series

The Series covers a range of systems thinking methods, tools, and approaches, including system dynamics modeling [ 15 ], causal loop diagrams [ 8 – 12 ], and social network analysis [ 13 , 14 ]. In addition, several papers couched their analysis in a complex adaptive systems framework [ 9 , 10 , 16 ], or adapted established methods, such as realist evaluation [ 7 , 12 ] and policy analysis [ 16 , 17 ], to untangle the underlying complexity of their research questions. The main approaches, research questions. and findings of the Series papers are discussed in turn below.

The paper by Bishai et al. uses a system dynamics simulation model to illustrate trade-offs and unintended consequences in allocative funding decisions to curative versus preventive care [ 15 ]. The model provides a quantitative application of complex adaptive systems methodologies to a health systems and policy question, something that traditional cost-effectiveness analysis techniques fail to illustrate. In this paper, the authors demonstrate how the growth of curative care services can crowd both fiscal space and policy space for delivering population-level prevention services, which would require extensive and long-term interventions to overcome the fiscal and population health consequences [ 15 ].

The paper by Prashanth et al. is one of three papers exploring capacity strengthening initiatives targeting health workers and managers [ 7 ]. They use realist evaluation to explore how a capacity building intervention for district health managers implemented in two different places evolved over time, taking into account the context and the mechanism of change. The paper highlights the importance of the people involved and the choices they make in the evolution of outcomes, and how individual and organizational attributes and the interaction between them contribute to any particular outcome [ 7 ].

Kwamie et al. is another paper looking at capacity strengthening of middle-range managers [ 12 ]. The authors also used realist evaluation, supplemented by visually interpreting their findings using a causal loop diagram, to examine how and why a Leadership Development Programme works when it is introduced into a district health system and whether or not it supports systems thinking in district teams, using Ghana as a case study. They conclude that the leadership program on its own did not lead to the development of a systems thinking approach in management and decision-making in the district and argue that the complexity of organizational contexts and history are important influencing factors for the sustainability or scaling up of such programs, as much as the complexity of the intervention itself [ 12 ].

Gilson et al. stimulate wider thinking about the forms and practices of health leadership [ 17 ]. They use the concepts of sense-making and discretionary power drawn from the theories of complex adaptive systems and policy implementation to highlight how important it is that health system actors are able to make sense of the intentions of policies to be able to incorporate them into their everyday routines and practices. The study reveals how the collective staff understanding of their working environment, and how changes occur within it, may act as a barrier to centrally-led initiatives to strengthen capacities [ 17 ].

Next, in an application of social network analysis, the study by Malik et al. describes the formal and informal ways in which primary care physicians in Pakistan access information [ 13 ]. By employing a range of research methods, the paper examines the reasons for the disparity between organizational structures for supervisory and reporting relationships and the actual behavior of primary care physicians when seeking information. They argue for the importance and value of exploring the supervisory and technical support arrangements from the view point of the users [ 13 ].

In the paper by Paina et al. [ 9 ], the authors investigate how, in a context of no official government policy on dual practice, this practice is currently being regulated in Uganda through a system of “unwritten” expectations and local management practices that have not been elsewhere documented. Through a series of causal loop diagrams and historical and primary accounts, the authors depict the resulting behavioral patterns and complex systems characteristics such as policy resistance in the form of protests by government providers and coping approaches by providers and their managers to maintain public sector’s service delivery and performance [ 9 ].

Rwashana et al. offer another application of causal loop diagrams in exploring the complexity which characterize neonatal health and its interplay with health systems factors, using Uganda as a case study [ 8 ]. The analysis revealed multiple feedback loops, such as trust, that household place on the health system, awareness of the benefits of antenatal and postnatal care, myths, frustration of health workers and its impact on all aspects of their performance, among others. The authors also discuss high leverage points that may be considered by policy makers to improve neonatal health such as gender considerations related to girls education and empowerment [ 8 ].

Next, in their analysis of the causes of reductions in coverage of vaccination in Kerala, Varghese et al. demonstrate how important it is that the evidence used to design and evaluate public health programs goes beyond epidemiological and economic analysis [ 10 ]. The paper shows how key factors that contributed to the unexpected decline in vaccination coverage were revealed such as how the opposition by the government medical doctors association and alternative medicines proponents, compounded by strong media influence, have evolved overtime and created a big unexpected influence on people’s decision to vaccinate [ 10 ].

The following two papers explore experiences with two financing schemes in Ghana and China. In their analysis of the Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme, Agyepong et al. suggest that relatively less attention seems to be paid to service access and service responsiveness when evaluating an insurance scheme [ 11 ]; something that people thinking about enrolling consider as much as the financial risk protection potential. They highlight why a comprehensive systems thinking approach is essential when conceptualization and designing a health insurance scheme to avoid the emergence of counterintuitive and undesired effects [ 11 ]. Zhang et al. offer another perspective of a financing intervention, by exploring the evolution of rural finance schemes in China [ 16 ]. The paper discusses the nature of health systems resilience facing the implementation problems associated with the policy and argues that initial trajectories have been a big determinant of how policy-makers adapted in the various contexts [ 16 ].

Blanchet et al. examine sustainability in internationally-initiated programs in their comparison of sustainability-oriented processes in two rehabilitation centres in Nepal and Somaliland [ 14 ]. The paper shows how differences in the governance and network structure of the rehabilitation centres, revealed through a stakeholder network analysis, have influenced the process and commitment to sustainability. The analysis helped in the understanding of change in the nature of relationships between actors and their capacity to work together over time and what factors are conducive to providing the right incentives to work as an interrelated network rather than as individual actors [ 14 ].

In second paper addressing sustainability issues, Sarriot et al. examine how an international NGO worked with two Bangladeshi municipal health departments to intentionally advance sustainability in their support for maternal and child health preventive services [ 18 ]. The paper explores how systems thinking was used to generate a process of change within municipal health systems, affecting technical, social, political, and organizational sub-systems. The authors document how a sustainability framework method was used to work with stakeholders in an explicit process to guide their decisions and choices during and after the life of a project. They illustrate how this process offered useful tools to engage stakeholders, give shared meaning to information about activities and achievements, facilitate decision making, and mitigate the risk of unintended project effects in order to achieve a measure of sustainability in a complex setting [ 18 ].

Last but not least, the commentary by Peters discusses which of the large body of theories, tools, and methods associated with systems thinking are more useful to understanding the behaviour and complexity of health systems [ 6 ]. It also discusses the “jungle” of terminology surrounding this field and how and why some terms have emerged and been used differently in different disciplines. It then provides a helpful overview of a wide range of systems thinking theories, methods, and tools that are relevant to understanding and exploring health systems questions [ 6 ].

Looking forward

With the selection of papers in this Series, our aim was to give meaning to abstract concepts and theories through actual applications and experiences of how systems thinking tools and concepts can be used to understand and strengthen health systems, particularly in LMICs. We hope that by providing a variety of experiences, examples, and ideas that are relevant to other complex interventions and contexts, this collection will stimulate wider applications and innovations of these and other approaches relevant to this field.

Adam T, de Savigny D: Systems thinking for strengthening health systems in LMICs: need for a paradigm shift. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27: 1-3. 10.1093/heapol/czr006.

Article Google Scholar

Adam T, Hsu J, de Savigny D, Lavis JN, Rottingen JA, Bennett S: Evaluating health systems strengthening interventions in low-income and middle-income countries: are we asking the right questions?. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27: 9-19.

Google Scholar

Best A, Clark PI, Leischow SJ, Trochim WM: Greater than the Sum: Systems Thinking in Tobacco Control. 2007, Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health

Leischow SJ, Best A, Trochim WM, Clark PI, Gallagher RS, Marcus SE, Matthews E: Systems thinking to improve the public’s health. Am J Prev Med. 2008, 35: S196-S203. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.014.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

de Savigny D, Adam T: Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening. Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. 2009, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/9789241563895/en/ ,

Peters DH: Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: why use systems thinking?. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014, 12: 51-10.1186/1478-4505-12-51.

Prashanth NS, Marchal B, Macq J, Devadasan N, Kegels G, Criel B: Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: a realist evaluation of a capacity building programme for district managers. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014, 12: 42-

Rwashana Semwanga A, Nakubulwa S, Nakakeeto-Kijjambu M, Adam T: Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: understanding the dynamics of neonatal mortality in Uganda. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014, 12: 36-10.1186/1478-4505-12-36.

Paina L, Bennett S, Ssengooba F, Peters DH: Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: exploring dual practice and its management in Kampala, Uganda. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014, 12: 41-10.1186/1478-4505-12-41.

Varghese J, Kutty VR, Paina L, Adam T: Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: understanding the growing complexity governing immunization services in Kerala, India. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014, 12: 47-

Agyepong IA, Aryeetey GC, Nonvignon J, Asenso-Boadi F, Dzikunu H, Antwi E, Ankrah D, Adjei-Acquah C, Esena R, Aikins M, Arhinful DK: Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: provider payment and service supply incentives in the Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme: a systems approach. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014, 12: 35-10.1186/1478-4505-12-35.

Kwamie A, van Dijk H, Agyepong IA: Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: realist evaluation of the leadership development programme for district manager decision-making in Ghana. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014, 12: 29-10.1186/1478-4505-12-29.