Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Two Decades Later, the Enduring Legacy of 9/11

Table of contents, a devastating emotional toll, a lasting historical legacy, 9/11 transformed u.s. public opinion, but many of its impacts were short-lived, u.s. military response: afghanistan and iraq, the ‘new normal’: the threat of terrorism after 9/11, addressing the threat of terrorism at home and abroad, views of muslims, islam grew more partisan in years after 9/11.

Americans watched in horror as the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, left nearly 3,000 people dead in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Nearly 20 years later, they watched in sorrow as the nation’s military mission in Afghanistan – which began less than a month after 9/11 – came to a bloody and chaotic conclusion.

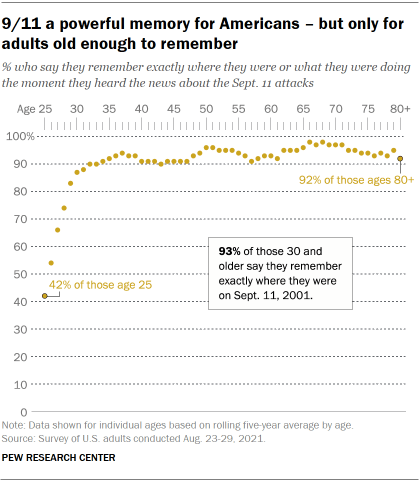

The enduring power of the Sept. 11 attacks is clear: An overwhelming share of Americans who are old enough to recall the day remember where they were and what they were doing when they heard the news. Yet an ever-growing number of Americans have no personal memory of that day, either because they were too young or not yet born.

A review of U.S. public opinion in the two decades since 9/11 reveals how a badly shaken nation came together, briefly, in a spirit of sadness and patriotism; how the public initially rallied behind the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, though support waned over time; and how Americans viewed the threat of terrorism at home and the steps the government took to combat it.

As the country comes to grips with the tumultuous exit of U.S. military forces from Afghanistan, the departure has raised long-term questions about U.S. foreign policy and America’s place in the world. Yet the public’s initial judgments on that mission are clear: A majority endorses the decision to withdraw from Afghanistan, even as it criticizes the Biden administration’s handling of the situation. And after a war that cost thousands of lives – including more than 2,000 American service members – and trillions of dollars in military spending, a new Pew Research Center survey finds that 69% of U.S. adults say the United States has mostly failed to achieve its goals in Afghanistan.

This examination of how the United States changed in the two decades following the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks is based on an analysis of past public opinion survey data from Pew Research Center, news reports and other sources.

Current data is from a Pew Research Center survey of 10,348 U.S. adults conducted Aug. 23-29, 2021. Most of the interviewing was conducted before the Aug. 26 suicide bombing at Kabul airport, and all of it was conducted before the completion of the evacuation. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology .

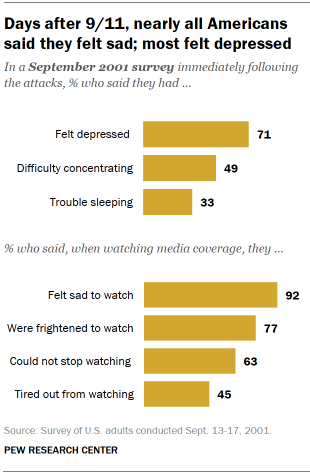

Shock, sadness, fear, anger: The 9/11 attacks inflicted a devastating emotional toll on Americans. But as horrible as the events of that day were, a 63% majority of Americans said they couldn’t stop watching news coverage of the attacks.

Our first survey following the attacks went into the field just days after 9/11, from Sept. 13-17, 2001. A sizable majority of adults (71%) said they felt depressed, nearly half (49%) had difficulty concentrating and a third said they had trouble sleeping.

It was an era in which television was still the public’s dominant news source – 90% said they got most of their news about the attacks from television, compared with just 5% who got news online – and the televised images of death and destruction had a powerful impact. Around nine-in-ten Americans (92%) agreed with the statement, “I feel sad when watching TV coverage of the terrorist attacks.” A sizable majority (77%) also found it frightening to watch – but most did so anyway.

Americans were enraged by the attacks, too. Three weeks after 9/11 , even as the psychological stress began to ease somewhat, 87% said they felt angry about the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon.

Fear was widespread, not just in the days immediately after the attacks, but throughout the fall of 2001. Most Americans said they were very (28%) or somewhat (45%) worried about another attack . When asked a year later to describe how their lives changed in a major way, about half of adults said they felt more afraid, more careful, more distrustful or more vulnerable as a result of the attacks.

Even after the immediate shock of 9/11 had subsided, concerns over terrorism remained at higher levels in major cities – especially New York and Washington – than in small towns and rural areas. The personal impact of the attacks also was felt more keenly in the cities directly targeted: Nearly a year after 9/11, about six-in-ten adults in the New York (61%) and Washington (63%) areas said the attacks had changed their lives at least a little, compared with 49% nationwide. This sentiment was shared by residents of other large cities. A quarter of people who lived in large cities nationwide said their lives had changed in a major way – twice the rate found in small towns and rural areas.

The impacts of the Sept. 11 attacks were deeply felt and slow to dissipate. By the following August, half of U.S. adults said the country “had changed in a major way” – a number that actually increased , to 61%, 10 years after the event .

A year after the attacks, in an open-ended question, most Americans – 80% – cited 9/11 as the most important event that had occurred in the country during the previous year. Strikingly, a larger share also volunteered it as the most important thing that happened to them personally in the prior year (38%) than mentioned other typical life events, such as births or deaths. Again, the personal impact was much greater in New York and Washington, where 51% and 44%, respectively, pointed to the attacks as the most significant personal event over the prior year.

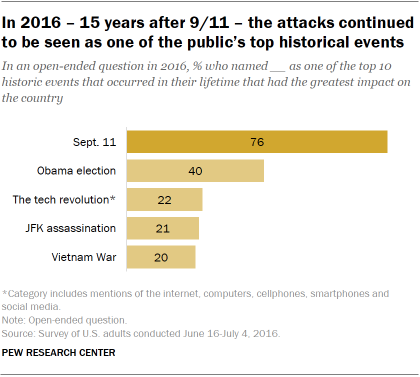

Just as memories of 9/11 are firmly embedded in the minds of most Americans old enough to recall the attacks, their historical importance far surpasses other events in people’s lifetimes. In a survey conducted by Pew Research Center in association with A+E Networks’ HISTORY in 2016 – 15 years after 9/11 – 76% of adults named the Sept. 11 attacks as one of the 10 historical events of their lifetime that had the greatest impact on the country. The election of Barack Obama as the first Black president was a distant second, at 40%.

The importance of 9/11 transcended age, gender, geographic and even political differences. The 2016 study noted that while partisans agreed on little else that election cycle, more than seven-in-ten Republicans and Democrats named the attacks as one of their top 10 historic events.

It is difficult to think of an event that so profoundly transformed U.S. public opinion across so many dimensions as the 9/11 attacks. While Americans had a shared sense of anguish after Sept. 11, the months that followed also were marked by rare spirit of public unity.

Patriotic sentiment surged in the aftermath of 9/11. After the U.S. and its allies launched airstrikes against Taliban and al-Qaida forces in early October 2001, 79% of adults said they had displayed an American flag. A year later, a 62% majority said they had often felt patriotic as a result of the 9/11 attacks.

Moreover, the public largely set aside political differences and rallied in support of the nation’s major institutions, as well as its political leadership. In October 2001, 60% of adults expressed trust in the federal government – a level not reached in the previous three decades, nor approached in the two decades since then.

George W. Bush, who had become president nine months earlier after a fiercely contested election, saw his job approval rise 35 percentage points in the space of three weeks. In late September 2001, 86% of adults – including nearly all Republicans (96%) and a sizable majority of Democrats (78%) – approved of the way Bush was handling his job as president.

Americans also turned to religion and faith in large numbers. In the days and weeks after 9/11, most Americans said they were praying more often. In November 2001, 78% said religion’s influence in American life was increasing, more than double the share who said that eight months earlier and – like public trust in the federal government – the highest level in four decades .

Public esteem rose even for some institutions that usually are not that popular with Americans. For example, in November 2001, news organizations received record-high ratings for professionalism. Around seven-in-ten adults (69%) said they “stand up for America,” while 60% said they protected democracy.

Yet in many ways, the “9/11 effect” on public opinion was short-lived. Public trust in government, as well as confidence in other institutions, declined throughout the 2000s. By 2005, following another major national tragedy – the government’s mishandling of the relief effort for victims of Hurricane Katrina – just 31% said they trusted the federal government, half the share who said so in the months after 9/11. Trust has remained relatively low for the past two decades: In April of this year, only 24% said they trusted the government just about always or most of the time.

Bush’s approval ratings, meanwhile, never again reached the lofty heights they did shortly after 9/11. By the end of his presidency, in December 2008, just 24% approved of his job performance.

With the U.S. now formally out of Afghanistan – and with the Taliban firmly in control of the country – most Americans (69%) say the U.S. failed in achieving its goals in Afghanistan.

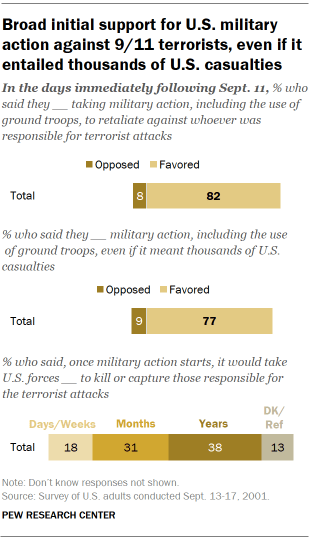

But 20 years ago, in the days and weeks following 9/11, Americans overwhelmingly supported military action against those responsible for the attacks. In mid-September 2001, 77% favored U.S. military action, including the deployment of ground forces, “to retaliate against whoever is responsible for the terrorist attacks, even if that means U.S. armed forces might suffer thousands of casualties.”

Many Americans were impatient for the Bush administration to give the go-ahead for military action. In a late September 2001 survey, nearly half the public (49%) said their larger concern was that the Bush administration would not strike quickly enough against the terrorists; just 34% said they worried the administration would move too quickly.

Even in the early stages of the U.S. military response, few adults expected a military operation to produce quick results: 69% said it would take months or years to dismantle terrorist networks, including 38% who said it would take years and 31% who said it would take several months. Just 18% said it would take days or weeks.

The public’s support for military intervention was evident in other ways as well. Throughout the fall of 2001, more Americans said the best way to prevent future terrorism was to take military action abroad rather than build up defenses at home. In early October 2001, 45% prioritized military action to destroy terrorist networks around the world, while 36% said the priority should be to build terrorism defenses at home.

Initially, the public was confident that the U.S. military effort to destroy terrorist networks would succeed. A sizable majority (76%) was confident in the success of this mission, with 39% saying they were very confident.

Support for the war in Afghanistan continued at a high level for several years to come. In a survey conducted in early 2002, a few months after the start of the war, 83% of Americans said they approved of the U.S.-led military campaign against the Taliban and al-Qaida in Afghanistan. In 2006, several years after the United States began combat operations in Afghanistan, 69% of adults said the U.S. made the right decision in using military force in Afghanistan. Only two-in-ten said it was the wrong decision.

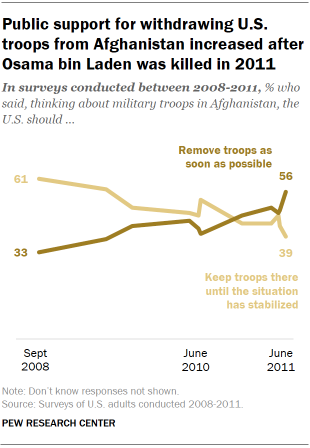

But as the conflict dragged on, first through Bush’s presidency and then through Obama’s administration, support wavered and a growing share of Americans favored the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. In June 2009, during Obama’s first year in office, 38% of Americans said U.S. troops should be removed from Afghanistan as soon as possible. The share favoring a speedy troop withdrawal increased over the next few years. A turning point came in May 2011, when U.S. Navy SEALs launched a risky operation against Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan and killed the al-Qaida leader.

The public reacted to bin Laden’s death with more of a sense of relief than jubilation . A month later, for the first time , a majority of Americans (56%) said that U.S. forces should be brought home as soon as possible, while 39% favored U.S. forces in the country until the situation had stabilized.

Over the next decade, U.S. forces in Afghanistan were gradually drawn down, in fits and starts, over the administrations of three presidents – Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Meanwhile, public support for the decision to use force in Afghanistan, which had been widespread at the start of the conflict, declined . Today, after the tumultuous exit of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, a slim majority of adults (54%) say the decision to withdraw troops from the country was the right decision; 42% say it was the wrong decision.

There was a similar trajectory in public attitudes toward a much more expansive conflict that was part of what Bush termed the “war on terror”: the U.S. war in Iraq. Throughout the contentious, yearlong debate before the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Americans widely supported the use of military force to end Saddam Hussein’s rule in Iraq.

Importantly, most Americans thought – erroneously, as it turned out – there was a direct connection between Saddam Hussein and the 9/11 attacks. In October 2002, 66% said that Saddam helped the terrorists involved in the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

In April 2003, during the first month of the Iraq War, 71% said the U.S. made the right decision to go to war in Iraq. On the 15th anniversary of the war in 2018, just 43% said it was the right decision. As with the case with U.S. involvement in Afghanistan, more Americans said that the U.S. had failed (53%) than succeeded (39%) in achieving its goals in Iraq.

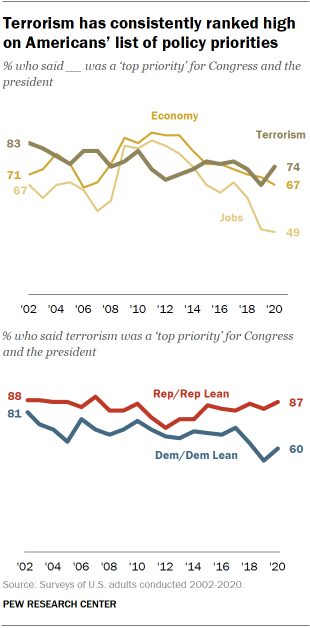

There have been no terrorist attacks on the scale of 9/11 in two decades, but from the public’s perspective, the threat has never fully gone away. Defending the country from future terrorist attacks has been at or near the top of Pew Research Center’s annual survey on policy priorities since 2002.

In January 2002, just months after the 2001 attacks, 83% of Americans said “defending the country from future terrorist attacks” was a top priority for the president and Congress, the highest for any issue. Since then, sizable majorities have continued to cite that as a top policy priority.

Majorities of both Republicans and Democrats have consistently ranked terrorism as a top priority over the past two decades, with some exceptions. Republicans and Republican-leaning independents have remained more likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to say defending the country from future attacks should be a top priority. In recent years, the partisan gap has grown larger as Democrats began to rank the issue lower relative to other domestic concerns. The public’s concerns about another attack also remained fairly steady in the years after 9/11, through near-misses and the federal government’s numerous “Orange Alerts” – the second-most serious threat level on its color-coded terrorism warning system.

A 2010 analysis of the public’s terrorism concerns found that the share of Americans who said they were very concerned about another attack had ranged from about 15% to roughly 25% since 2002. The only time when concerns were elevated was in February 2003, shortly before the start of the U.S. war in Iraq.

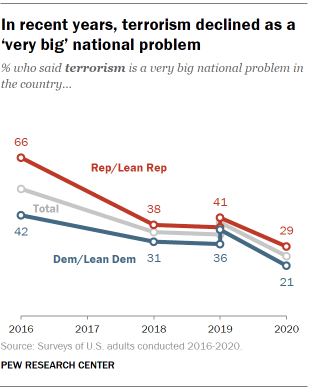

In recent years, the share of Americans who point to terrorism as a major national problem has declined sharply as issues such as the economy, the COVID-19 pandemic and racism have emerged as more pressing problems in the public’s eyes.

In 2016, about half of the public (53%) said terrorism was a very big national problem in the country. This declined to about four-in-ten from 2017 to 2019. Last year, only a quarter of Americans said that terrorism was a very big problem.

This year, prior to the U.S. withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan and the subsequent Taliban takeover of the country, a somewhat larger share of adults said domestic terrorism was a very big national problem (35%) than said the same about international terrorism . But much larger shares cited concerns such as the affordability of health care (56%) and the federal budget deficit (49%) as major problems than said that about either domestic or international terrorism.

Still, recent events in Afghanistan raise the possibility that opinion could be changing, at least in the short term. In a late August survey, 89% of Americans said the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan was a threat to the security of the U.S., including 46% who said it was a major threat.

Just as Americans largely endorsed the use of U.S. military force as a response to the 9/11 attacks, they were initially open to a variety of other far-reaching measures to combat terrorism at home and abroad. In the days following the attack, for example, majorities favored a requirement that all citizens carry national ID cards, allowing the CIA to contract with criminals in pursuing suspected terrorists and permitting the CIA to conduct assassinations overseas when pursuing suspected terrorists.

However, most people drew the line against allowing the government to monitor their own emails and phone calls (77% opposed this). And while 29% supported the establishment of internment camps for legal immigrants from unfriendly countries during times of tension or crisis – along the lines of those in which thousands of Japanese American citizens were confined during World War II – 57% opposed such a measure.

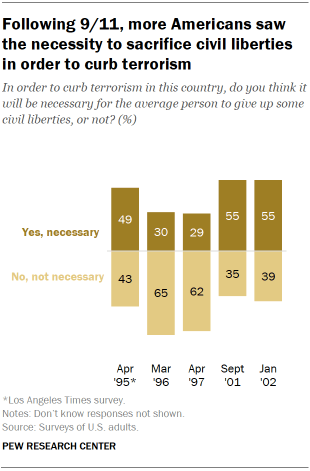

It was clear that from the public’s perspective, the balance between protecting civil liberties and protecting the country from terrorism had shifted. In September 2001 and January 2002, 55% majorities said that, in order to curb terrorism in the U.S., it was necessary for the average citizen to give up some civil liberties. In 1997, just 29% said this would be necessary while 62% said it would not.

For most of the next two decades, more Americans said their bigger concern was that the government had not gone far enough in protecting the country from terrorism than said it went too far in restricting civil liberties.

The public also did not rule out the use of torture to extract information from terrorist suspects. In a 2015 survey of 40 nations, the U.S. was one of only 12 where a majority of the public said the use of torture against terrorists could be justified to gain information about a possible attack.

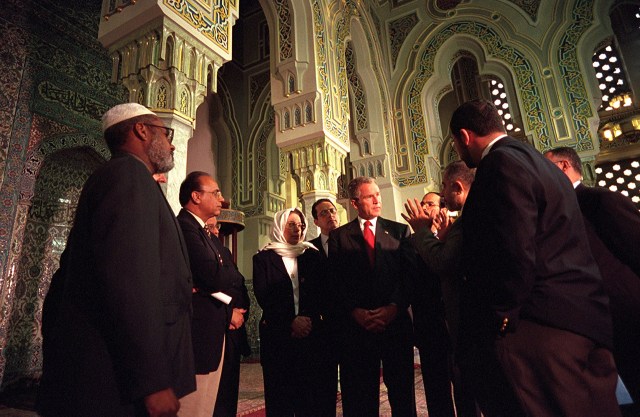

Concerned about a possible backlash against Muslims in the U.S. in the days after 9/11, then-President George W. Bush gave a speech to the Islamic Center in Washington, D.C., in which he declared: “Islam is peace.” For a brief period, a large segment of Americans agreed. In November 2001, 59% of U.S. adults had a favorable view of Muslim Americans, up from 45% in March 2001, with comparable majorities of Democrats and Republicans expressing a favorable opinion.

This spirit of unity and comity was not to last. In a September 2001 survey, 28% of adults said they had grown more suspicious of people of Middle Eastern descent; that grew to 36% less than a year later.

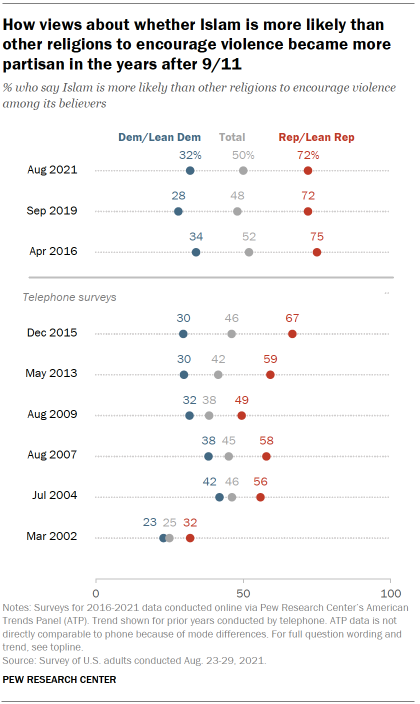

Republicans, in particular, increasingly came to associate Muslims and Islam with violence. In 2002, just a quarter of Americans – including 32% of Republicans and 23% of Democrats – said Islam was more likely than other religions to encourage violence among its believers. About twice as many (51%) said it was not.

But within the next few years, most Republicans and GOP leaners said Islam was more likely than other religions to encourage violence. Today, 72% of Republicans express this view, according to an August 2021 survey.

Democrats consistently have been far less likely than Republicans to associate Islam with violence. In the Center’s latest survey, 32% of Democrats say this. Still, Democrats are somewhat more likely to say this today than they have been in recent years: In 2019, 28% of Democrats said Islam was more likely than other religions to encourage violence among its believers than other religions.

The partisan gap in views of Muslims and Islam in the U.S. is evident in other meaningful ways. For example, a 2017 survey found that half of U.S. adults said that “Islam is not part of mainstream American society” – a view held by nearly seven-in-ten Republicans (68%) but only 37% of Democrats. In a separate survey conducted in 2017, 56% of Republicans said there was a great deal or fair amount of extremism among U.S. Muslims, with fewer than half as many Democrats (22%) saying the same.

The rise of anti-Muslim sentiment in the aftermath of 9/11 has had a profound effect on the growing number of Muslims living in the United States. Surveys of U.S. Muslims from 2007-2017 found increasing shares saying they have personally experienced discrimination and received public expression of support.

It has now been two decades since the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon and the crash of Flight 93 – where only the courage of passengers and crew possibly prevented an even deadlier terror attack.

For most who are old enough to remember, it is a day that is impossible to forget. In many ways, 9/11 reshaped how Americans think of war and peace, their own personal safety and their fellow citizens. And today, the violence and chaos in a country half a world away brings with it the opening of an uncertain new chapter in the post-9/11 era.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

- Research & Innovation

- Arts & Creativity

- Teaching & Learning

- Life at Ohio State

- In the Community

9/11: causes and lingering consequences

- Facebook profile — external

- Twitter profile — external

- Email — external

- LinkedIn profile — external

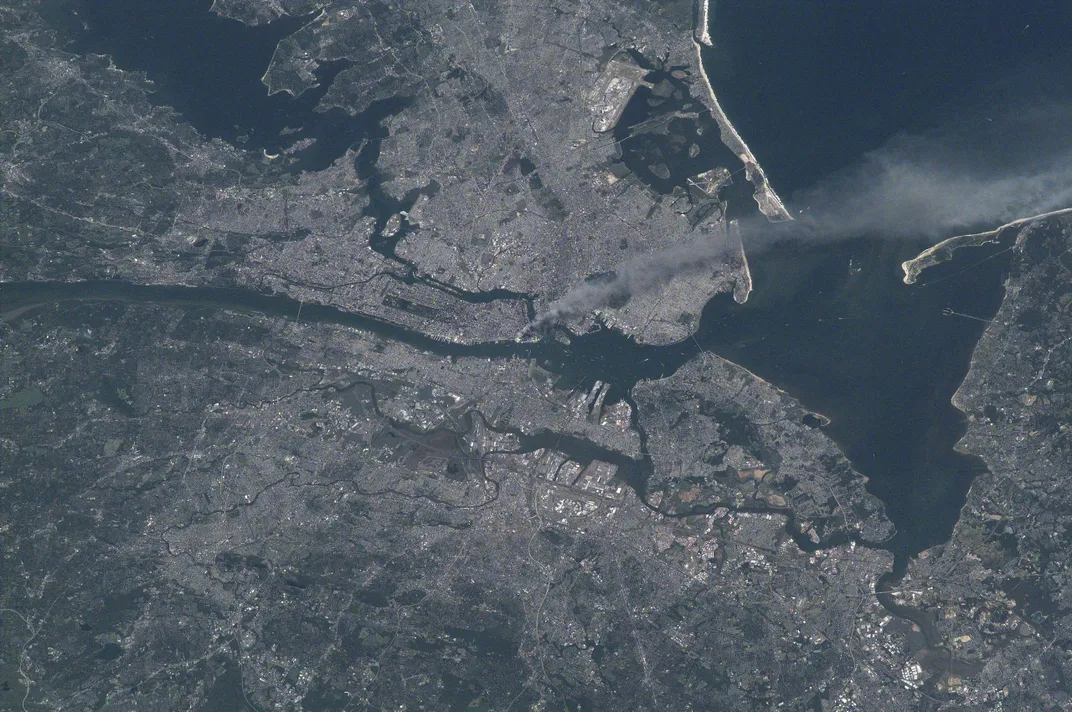

The images from that day still haunt us.

The Twin Towers plummeting to the ground, one following the other, smoke snaking through streets, billowing for blocks, fear and confusion spreading like ashes across the country.

We know now what we didn’t know that day: that the terrorist attack had been building for more than a decade. And that it would change our country, irreparably, forever.

Here, Peter Hahn , a professor of history and dean of arts and humanities at Ohio State, discusses the causes — and lingering consequences — of 9/11.

Our research community

You also might like.

This paper provides detailed rebuttals to attempts to explain the extreme and persistent high temperatures in the Ground Zero rubble piles as the results of fires rather than of energetic materials used to demolish the buildings.

This paper examines energy flows in the collapse of the North Tower, and presents a case that expansion of the dust cloud immediately following its collapse constituted a thermal energy sink many times the size of the presumed energy source -- the gravitational potential energy of the tower.

This paper examines the first few seconds of the North Tower's collapse after a detailed review of the fires based on NIST's data, and shows that collapse progressed far too rapidly to be explained without the involvement of demolition.

This paper examines the rate of descent of WTC 7 using measurements of a video that shows the top half of the building. It shows that the facade's rate of descent closely matches the rate of gravitational free-fall. (This paper is also published in the Journal of 9/11 Studies .)

This paper briefly reviews the major collapse theories of the Twin Towers and then zooms in on a key assertion of NIST: that the North Tower was "poised for collapse" prior to experiencing "global collapse". Legge uses NIST's own data to show that, at 10:28, WTC 1 was not "poised for collapse" and that the "collapse initiation" supposed by NIST could not have happened. (This paper is also published in the Journal of 9/11 Studies .)

This paper provides detailed data on the total mass and mass distrubtion of the North Tower (WTC 1), compiled from various sources including documents from NIST's investigation and leaked architectural plans of the skyscraper.

Knowledge from Tragedy: NYU Research Post-9/11

© Hollenshead: Courtesy of NYU Photo Bureau

For many NYU scholars—some of them New Yorkers who witnessed the destruction of the World Trade Center from the vantage point of our Greenwich Village campus, less than two miles north—research has been an essential tool for better understanding the September 11 attacks and their aftermath. Over the past two decades, numerous faculty have studied 9/11’s impact on our physical and mental health; examined how to improve our nation’s security and preparedness; evaluated New York City’s infrastructure and resilience; analyzed the legal and policy consequences of the attacks; and captured painful and inspiring stories through art.

On the occasion of this anniversary, NYU News gathered a small sampling of projects that show how our researchers in diverse fields—whose efforts may carry personal as well as professional significance—rose to the occasion to generate knowledge and contribute to New York City’s recovery.

The psychological impact of the attacks

- Research by Silver’s Carol Tosone explored how the World Trade Center attacks affected the practice of therapists. After surveying Manhattan clinicians , she described the construct of shared trauma, which involves the dual impact of trauma on clinicians exposed both through their personal experiences and their work with survivors.

- Steinhardt researchers Beth Weitzman and Tod Mijanovich conducted a nationwide survey of youth and their parents before and after September 11 to examine psychological distress among American youth related to the attacks. They found that young people experienced more emotional distress after 9/11, and that those exposed to physical threats at school were especially vulnerable to the psychological effects of disasters.

- A special issue of the journal Traumatology , published in 2011, focused on reflections of NYU faculty, students, and administrators who were at the university on September 11. The articles offer insights into what the campus community experienced, as well as professional analyses on the impact of the event.

- Steinhardt art therapist Marygrace Berberian developed and facilitated a curriculum for post-9/11 recovery for children. The intervention culminated in a large installation of artwork across from Ground Zero , including self-portraits of more than 3,100 children from around the world.

The World Trade Center Children's Mural at 120 Broadway in 2002. Photo courtesy of Marygrace Berberian

Health and dangerous exposures

- Research on 9/11 firefighters and EMS workers led by Anna Nolan and her team at the Grossman School of Medicine identified 30 chemical compounds that may help protect these first responders from losing lung function. These so-called metabolites are made when the body breaks down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, and include protein-building amino acids and mega-3 fatty acids, which are found in fish and olive oil. The findings suggest that drugs, dietary changes, and regular exercise can protect people exposed to toxic chemicals created by fire and smoke.

- An investigation by Leonardo Trasande and his team at the Grossman School of Medicine found that children living near the World Trade Center who likely breathed in toxic dust have elevated levels of artery-hardening fats in their blood, an early indicator of future heart disease. The study , which analyzed blood tests from over 300 kids, is the first to identify long-term cardiovascular health risks in children from toxic chemical exposure on 9/11, but offers hope that early intervention like diet and exercise can alleviate some of the health risks.

- Research involving the School of Global Public Health’s Jack Caravanos examined lead and other environmental toxins in New York City following the attacks. One study found only low levels of lead in dust in lower Manhattan, likely due to the extensive cleanup of the area, but also identified several "hot spots" of environmental lead elsewhere, including one in Staten Island that may have been connected to debris from the World Trade Center.

- A study led by the College of Dentistry’s Karen Raphael evaluated more than 1,300 women in the New York metro area both before and after the attacks to see whether symptoms consistent with fibromyalgia—a disorder marked by widespread pain—increased. She found that rates of fibromyalgia-like pain did not grow significantly after the attacks regardless of direct exposure to events, nor did prior depression predict the onset of this pain, suggesting that exposure to major stressors or prior depression are unlikely to be major factors in the development of fibromyalgia.

© Getty Images

Skyscrapers, infrastructure, and downtown Manhattan’s recovery

- The World Trade Center Evacuation Study , led by the School of Global Public Health’s Robyn Gershon , examined factors that helped people to quickly and safely exit the towers during the attacks. The study found that evacuees with lower levels of preparedness were more likely to report fear of working in tall buildings, stress, anxiety, and flashbacks compared to evacuees who had more emergency training. The findings helped lead to the first changes in New York City’s high-rise fire safety codes in more than 30 years.

- The ability to rapidly restore transportation, power, water, and environmental services is critical after a disaster. This became the focus of work by Wagner’s Rae Zimmerman , who evaluated New York City’s infrastructure and user needs before, during, and after September 11. Her research found that the capability of service providers to respond to needs for transportation, energy, communication, water, sanitation, and waste removal after the attacks was influenced by the flexibility of the initial infrastructure design and existing functions to respond to normal system disruptions and to other extreme events.

- A 2015 report by the Rudin Center found that the rebuilding of the World Trade Center will generate an enormous economic return for the Port Authority and the New York region.

Preparing for future threats

- In 2002, NYU established the Center for Catastrophe Preparedness and Response with funding from Congress. The university-wide center, focused on improving the nation’s preparedness and response capabilities to terrorist threats and catastrophic events, coordinated and disseminated research and generated policy recommendations related to homeland security. Resulting research included reports on facial recognition technology , modeling to help hospitals prepare for disasters , and emergency medical services as the “forgotten first responder.”

- Soon after 9/11, the U.S. was faced with the potential for biological and chemical attacks, an area of focus for several researchers who are now part of the Tandon School of Engineering. Kalle Levon worked on the environmental detection of bioagents using funds from the Department of Defense and DARPA; Vikram Kapila conceived of a wireless sensor network to connect hazard-detecting sensors in New York’s subway stations; and Kurt Becker conducted research on the inactivation of biological and chemical agents, such as anthrax, as well as on sensing and quantifying trace concentrations of explosives .

- Since many experts believed the next terrorist attack would be online, 9/11 was the impetus behind the creation of the Offensive Security, Incident Response, and Internet Security (OSIRIS) Lab , part of Tandon’s Center for Cybersecurity and led by Nasir Memon . Memon spearheaded a partnership with NYC Cyber Command , which leads the city’s cyber defense efforts, to run cybersecurity simulations to practice protecting the city’s systems from malicious attacks.

A 2019 cybersecurity training exercise with Tandon and NYC Cyber Command. Photo courtesy of NYU Tandon

Law and policy post-9/11

- The Reiss Center on Law and Security at the School of Law focuses on contemporary questions in the field of national security, including many that have arisen in the context of the “Forever War” that stemmed from September 11 and the evolution of power and legal authorities in the executive branch. In 2020, the Center published the War Powers Resolution Reporting Project , the first publicly accessible, searchable database analyzing the contents of more than 100 reports submitted by presidents to Congress, providing insights into the balance of powers between the branches with respect to how U.S. armed forces are used abroad.

- From 2005-2011, the then-Center on Law and Security also created a Terrorist Trial Report Card , a database that tracked the cases against alleged terrorists since 9/11, detailing the charges, convictions, plea bargains, and sentencing for federal terrorism prosecutions. In addition to the data collected in each of the 11 iterations of the report, the Terrorist Trial Report Card included analyses of the effectiveness of the "War on Terror" and the evolution in the Department of Justice's prosecution of these crimes.

- The NYU Review of Law and Security , founded by the Center on Law and Security, published articles, updates on the Terrorist Trial Report Card, and transcript excerpts from major dialogues convened by the Center. Each issue centered on a timely topic in national security and counterterrorism, ranging from Al-Qaeda to the legal questions surrounding Guantanamo and the challenges of prosecuting terrorism.

- In The Matador's Cape: America's Reckless Response to Terror (Cambridge University Press, 2009), law professor and Reiss Center faculty co-director Stephen Holmes explored the causes of the “catastrophic turn” in American policy at home and abroad since 9/11. Holmes detailed Washington’s inability to bring “the enemy” into focus since 9/11, describing the ideological, bureaucratic, electoral, and emotional forces that distorted the American understanding of, and response to, the terrorist threat.

- Politics Professor Bernard Manin examined the history of emergency powers going all the way back to Rome—and argued that constitutional democracies should not use these measures to deal with terrorism. In an essay , he suggested that emergency powers only work well when implemented as temporary measures to deal with temporary threats, but with terrorism as a long-term problem, a different response was called for.

American culture after the attacks

- NYU Abu Dhabi sociologist John O’Brien spent over three years conducting ethnographic fieldwork with a group of young Muslim teenagers coming of age in post-9/11 America. His book, Keeping It Halal: The Everyday Lives of Muslim American Teenage Boys (Princeton University Press, 2017), illustrated how the teens faced anti-Muslim discrimination, but much of their lives centered around “normal” teenage problems, like music and dating.

- In a new book, Terrorism in American Memory: Memorials, Museums, and Architecture in the Post-9/11 Era (NYU Press, 2022), Steinhardt’s Marika Sturken writes that the terrorist attacks were the primary force shaping U.S. politics and culture in the post-9/11 era. Her earlier book, Tourists of History (Duke University Press, 2007), argued that Americans have responded to the national trauma of September 11 through consumerism and kitsch, and explored the contentious debates about memorials and celebrity-architect designed buildings at Ground Zero.

- In " On The Actuarial Gaze: From 9/11 to Abu Ghraib ," Steinhardt's Allen Feldman considers the larger impact of circulated images. His analysis of pictures and video stemming from 9/11 illuminates the visual structure of catastrophes.

- In Tolerance and Risk: How U.S. Liberalism Racializes Muslims (University of Minnesota Press, 2021), Liberal Studies' Mitra Rastegar examines representations of Muslims in the media and writes that sympathetic representations cast Muslims as as a population with distinct characteristics, capacities, and risks.

Images courtesy of NYU Press

Catalyzing creative expression

- In 110 Stories: New York Writes after September 11 (NYU Press, 2002), Ulrich Baer gathered a range of voices that convey the shock and loss suffered in September 2001. The lineup of 110 renowned and emerging writers captured the shape and texture of a city in crisis, and what its inhabitants absorbed in the aftermath of a few unforgettable hours.

- Distinguished Writer-in-Residence Jonathan Safran Foer penned the novel Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (Houghton Mifflin, 2005), which centers on a nine-year-old boy whose father died in 1 World Trade Center. The book—which was later made into a film—was among several that formed a new genre of writing shaped by the attacks.

- Covering Catastrophe: Broadcast Journalists Report September 11 (Bonus Books, 2002), co-edited by journalism professor Mitchell Stephens , is an oral history of the events of that day in the words of more than 130 television and radio journalists, ranging from network anchors to local reporters from Johnstown, Pennsylvania.

- The 9/11 attacks inspired the composition of many artistic works, including a poem by Creative Writing’s Deborah Landau entitled “ Manhattan Fragments 2001-2002 ” and a musical composition by Steinhardt’s Faye-Ellen Silverman named “ Reconstructed Music ” (2002), which she began writing three days after the attacks.

This research was supported by funding from Congress, the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, among others.

September 1, 2011

Science after 9/11: How Research Was Changed by the September 11 Terrorist Attacks

New work in forensics, biodefense and cyber security blossomed after the attacks on New York City, Washington, D.C., and in the skies over Pennsylvania, but increased regulations have also stymied international collaboration as well as work on some infectious diseases

By Eugenie Samuel Reich

Two months after al Qaeda terrorists flew airplanes into the World Trade Center towers in Manhattan on September 11, 2001, analytical chemist John Butler found himself working late nights in his lab, developing DNA assays to identify 911 victims from the tens of thousands of charred human remains recovered at Ground Zero. Thinking back, he still clearly remembers the sense of rising to a national need that was shared by dozens of researchers recruited to the same difficult problem. "People wanted to step up and help the country," he says.

Ten years on, Butler's solitary effort at National Institute of Standards and Technology has grown to a large research group working on the forensics of blended, degraded or soiled DNA, and U.S. expertise developed in the wake of 9/11 has also been exported worldwide, put to use identifying victims of mass atrocities in Africa, Asia, Bosnia and Iraq.

It is just one example of how a research direction blossomed as a result of 9/11. Scientists and science policy experts say the federal government's response to terrorist events in 2001, both the September attacks and the anthrax letters in October, have had a profound effect on U.S. research in areas as diverse as forensics, biodefense, infectious diseases, public health, cyber security, geology and infrastructure, energy, and nuclear weapons. Even the social sciences have been affected by the emergence of "terrorism studies" and the new emphasis on the threat in the field of risk analysis.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A major conduit for the shifts is the availability of money: The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), created by consolidating 22 federal services and agencies in 2002 in direct response to September 11, had a science budget that peaked at $1.3 billion in 2006 before falling again to about $700 million in 2011. Key science-funding agencies including the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Energy, also put money into research motivated by security concerns (amounting to a total homeland security (this number does not refer to DHS but to homeland security funding across all agencies) research budget of $7.3 billion in 2011) and a small amount of the U.S. Department of Defense money associated with wars in Afghanistan and Iraq ended up in the hands of researchers as well—for example, by funding work on explosives detection and weaponry.

In biodefense, so much money poured into science that Judith Reppy, a science and technology studies expert at Cornell University, even considered whether (adapting the term coined by President Dwight Eisenhower in 1961) a "biomedical-military-industrial complex" has emerged in which scientists, the military and lobbyists conspire to try to keep the funds coming . She rejected that hypothesis, finding that biomedical science in the U.S. remains primarily a civilian endeavor, but says 9/11 has introduced trimmings of "guards, guns and gates," and increased funding research on pathogens that might be used by terrorists.

Some of the post-9/11 changes have entailed increased regulation. Jerry Jaax, a veterinarian and infectious disease researcher who oversees research compliance at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kans., says that many biomedical fields have been swamped by such new regulations or increased enforcement of pre-9/11 regulations in a bid to prevent researchers and the materials they handle from becoming security threats. He says federal rules on select agents—pathogens that require special facilities and handling—and on imports and exports of biological samples and materials, have slowed the ability of scientists to do research important to public and agricultural health. "Some say we're regulating away our ability to do this kind of research and I think there's some truth to that," he says.

And, a major difficulty has been immigration. The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 imposed stringent new visa requirements that restricted scientists and science students from all over the world from entering the U.S. Albert Teich, who has tracked the issue for the American Association for the Advancement of Science where he is director of science and policy programs, says that problem peaked in 2003, but has since improved, especially following lobbying of Congress by scientific societies and advice from the National Academy of Sciences, whose 2009 report " Beyond 'Fortress America '" and 2007 report " Rising above the Gathering Storm " were among those to suggest the rules be eased. But the policies had a lasting impact on the ability of U.S. researchers to collaborate and recruit students, he says.

Teich adds that security concerns have cast a shadow over U.S. science in a number of ways, and points to the erection of a steel security barrier around the perimeter of the previously open campus of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. "To me," he says, "that fence is a very dramatic visual impact of 9/11 on science."

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Exhibition Home

Research on 9/11 Health Impacts

After 9/11, health experts began evaluating exposure potential, defining diseases, and studying emerging trends in symptoms and conditions. In 2002, the CDC Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and the New York City (NYC) Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) established the World Trade Center Health Registry (the Registry). It became the largest post-disaster health registry in U.S. history, recruiting more than 71,000 voluntary registrants at the close of enrollment in 2004. In 2009, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) began administrating the Registry through the NYC DOHMH. Since inception, the Registry has published over 140 research papers on short- and long-term 9/11 health outcomes.

In addition to the Registry, research projects began to characterize exposures and assess the potential health burden in the 9/11 population. Early efforts examined a broad range of health conditions in both responders and survivors, such as aerodigestive disorders, cancers, and mental health disorders. This research was supported by private and public funds, including federal funding administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and NIOSH. In total, there were 565 articles published in peer-reviewed literature describing 9/11 research prior to the passing of the Zadroga Act.

The Zadroga Act provided funding for a formal 9/11 research program. From 2011-2020, the WTC Health Program has awarded a total of $195.1M for research through contracts, cooperative research agreements, and the Registry ($67.6M). Over 430 peer-reviewed articles have been published from WTC Health Program-funded studies. Annual research funding for long-term physical and mental health effects is authorized until 2090.

The WTC Health Program updates its research agenda to address existing knowledge gaps, investigate the emergence of health conditions linked to 9/11, and build upon current knowledge. Insight from scientists, community members, patients, and other stakeholders continue to shape the WTC Health Program’s research agenda.

Other Resources

- Program Statistics

- Research Gateway

- Research Compendium

- Research Agenda

- Research-to-Care Logic Model

- Research Webinars

Research Timeline

This timeline conveys the history of 9/11 Health Impacts Research efforts to today.

Prezant et al., 2002. N Engl J Med

Lin et al., 2005. Am J Epidemiol.

Brackbill, R. M., et al. (2009).

Zeig-Owens et al., 2011. Lancet

Stellman et al., 2013

Bromet et al., 2016. Psychol Med.

Clouston et al., 2016. Alzheimers Dement

Jordan et al., 2017. Occup Environ Med

Yu, S., et al. (2018).

Cohen et al., 2019. JAMA Network Open.

Learn more about our ongoing research efforts.

Treatment Inside the Clinic

Page Last Reviewed: October 23, 2023 | Page Last Updated: September 6, 2022

Smart News | September 9, 2021

Free Online Resources About 9/11

Browse 12 archives, databases and portals that help users deepen their understanding of the attacks

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/47/e347cda0-5a48-4e82-b776-43a0af5f7379/mobile_93.jpg)

Nora McGreevy

Correspondent

Twenty years after September 11, 2001, the first generation that grew up in a world profoundly altered by the attacks is coming of age.

Many of these young adults have little or no memory of the day itself. As the Pew Research Center reports, just 42 percent of 25-year-old Americans clearly remember where they were when they learned of the attacks. But for those who do remember, the horror of 9/11 remains fresh.

On that day, more than 2,977 people were killed in New York, Arlington and Pennsylvania. Thousands sustained physical injuries, and thousands more continue to reckon with trauma inflicted by the tragedy. Post- 9/11 wars , including those in Afghanistan and Iraq, have killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions more. The profound changes wrought by September 11, including the U.S. military response and the attacks’ impact on American art and culture , continue to be felt to this day.

Individuals hoping to learn more about this multifaceted history may find it difficult to know where to start. To support this search, Smithsonian has compiled a list of 12 free resources that deepen readers’ understanding of the September 11 attacks and their complicated, painful legacy. From the Library of Congress to the National September 11 Memorial and Museum, these archives, databases and web platforms help researchers and members of the public alike make sense of one of the most defining events of the 21st century.

National September 11 Memorial and Museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/5d/9b5d35b2-f8e4-4503-a54a-f236c9dcef55/about-board-directorsjl_otribnight_09.jpeg)

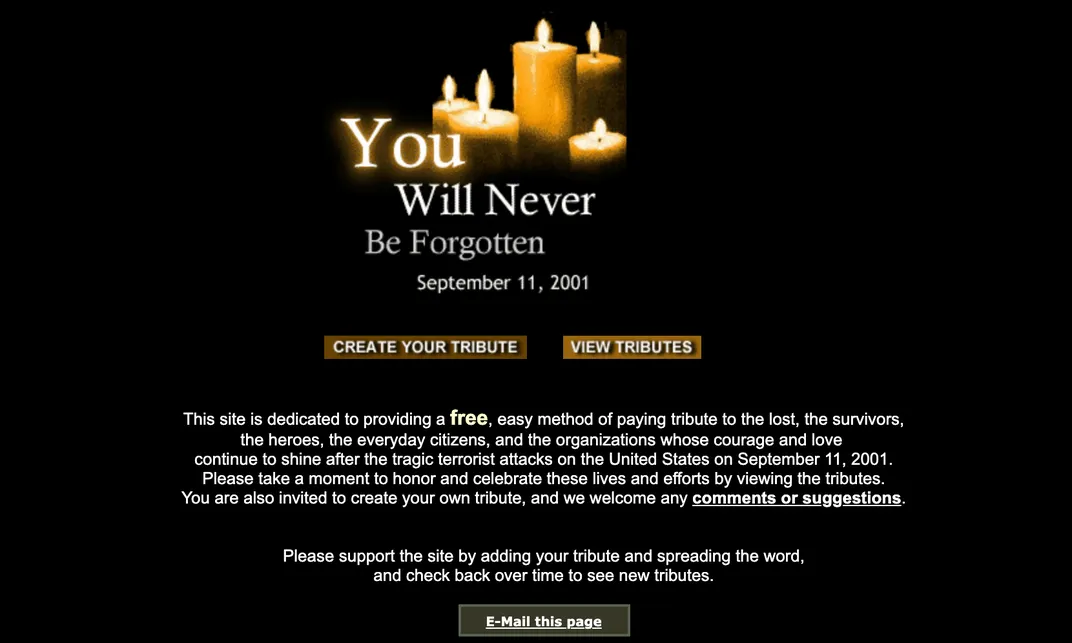

Every year, millions of people visit Ground Zero to see the two square reflecting pools installed where the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center (WTC) once stood. The museum affiliated with this memorial offers a bevy of digital resources , including explanatory exhibitions about the history of the WTC and the search for al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden . Librarians and educators can register to download a free poster exhibition about the attacks for classroom use.

Online viewers can also peruse the museum’s collection of more than 70,000 artifacts, including material evidence such as a pair of shoes worn by a survivor of the towers’ collapse. Those interested in hearing firsthand accounts of the day can listen to an edited selection from the museum’s ever-expanding collection of more than 1,000 oral histories.

September 11 Digital Archive

A project of the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, this free online archive holds more than 150,000 files related to 9/11. Users can browse over 40,000 first-person accounts; scroll through some 15,000 images; or peruse emails, documents, sound clips, videos and other digital ephemera.

The Library of Congress

Within hours of the attacks, Library of Congress (LOC) staff began collecting original materials linked to the day. Online users can search the library’s digital collections to find photographs, poetry, art, maps and eyewitness accounts of 9/11, many of which were featured in a 2002 exhibition at the Washington, D.C. institution.

The library’s 9/11 web archive preserves slices of the early internet as it appeared in the weeks and months following the attacks. Offerings include memorial websites, the front pages of major magazines like the New Yorker , political and religious websites, and the home page of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee .

On the day after the attacks, the LOC’s American Folklife Center started collecting oral history interviews with survivors and people across the country. “This collection captures the voices of a diverse ethnic, socioeconomic, and political cross-section of America during trying times and serves as a historical and cultural resource for future generations,” the library notes. Listeners can hear more than 150 of the audio recordings here .

National Museum of American History

Shortly after September 11, Congress designated the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History (NMAH) as the official repository for all objects related to the attacks. Curators cast a wide net, searching for items that explained the immediate impact of the violence and illuminated rescue and recovery efforts.

Today, viewers can explore the collection online. Items of note include the cellphone that then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani used to coordinate emergency efforts on the day of the attacks and a clock from the Pentagon whose hands froze when the plane hit the building.

NMAH also holds a turban that once belonged to Balbir Singh Sodhi , an Indian immigrant who owned a gas station in Mesa, Arizona. Four days after the attacks, a gunman killed Sodhi in a drive-by shooting. The killer had assumed that Sodhi was Muslim because of his turban; in reality, he was a follower of the Sikh faith. His murder marked the first in a wave of post-9/11 hate crimes against Muslim, South Asian, Arab and Middle Eastern communities in the U.S.

Brooklyn-based nonprofit StoryCorps preserves short oral histories—some accompanied by animations—from September 11 survivors and victims’ families. Viewers can peruse the multimedia stories and read transcripts of interviews on the organization’s website. Listings include an interview with Sodhi’s brothers, Rana and Harjit Sodhi .

American Archive of Public Broadcasting

The September 11 attacks consumed news cycles across the country on the day of the event and for weeks afterward. Through the 9/11 Special Coverage Collection at the American Archive of Public Broadcasting , members of the public can comb through hours of footage from 68 local and national television and radio stations.

Featured clips include a “PBS NewsHour” segment that aired on the evening of 9/11 and a September 12 “ New York Voices ” episode that found hosts Bill Moyer and Bill Baker interviewing religious leaders, callers and frontline workers as they began to process the attacks.

The Costs of War Project

More than 50 scholars, human rights practitioners and other experts contribute to Brown University’s Costs of War project, which documents the enormous human and monetary cost of the U.S.-led, post-9/11 military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as related violence in Pakistan and Syria. Readers can explore academic papers, data and classroom resources for free on the program’s website . All told, the team estimates that these conflicts have killed more than 929,000 people and displaced more than 38 million across the world.

Pew Research Center

To mark the 20th anniversary of the September 11 attacks, Hannah Hartig and Carroll Doherty of the nonpartisan Pew Research Center compiled a comprehensive, user-friendly overview of data about 9/11. Readers can access the resource here . Topics covered include trends in public opinion over the past two decades: For instance, though Americans overwhelmingly supported the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan at their outset, 69 percent now say that the U.S. mostly failed to achieve its goals in Afghanistan.

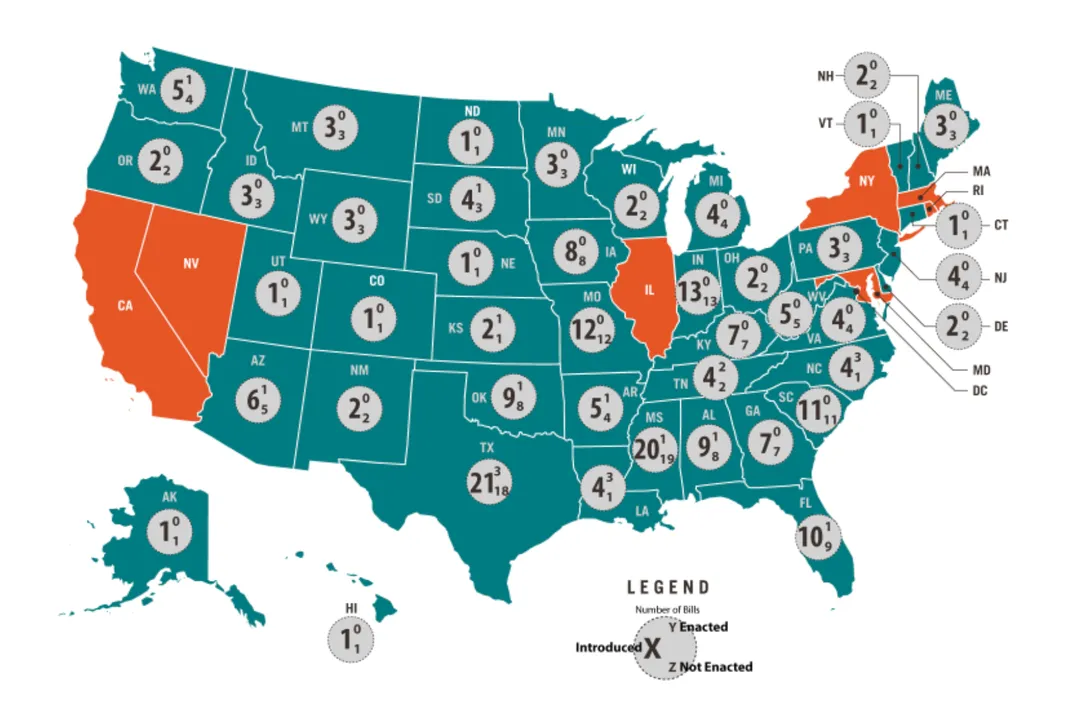

Othering and Belonging Institute’s Islamophobia Project

Researchers with UC Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute maintain a searchable database of anti-Muslim legislation introduced and enacted in the past decade, as well as major shifts in anti-Muslim sentiment that took place in the U.S. in the wake of 9/11. Online users can use the site more broadly to learn about the history of Islamophobia and find additional reading resources on the subject.

National Archives and Records Administration

In late 2002, Congress and President George W. Bush created the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, otherwise known as the 9/11 Commission , to research the events of September 11. Investigators conducted more than 1,200 fact-finding interviews. Executive summaries of some of these interviews have been declassified and can be located in the National Archives and Records Administration’s (NARA) digital catalog .

The commission’s full report, which is preserved by NARA and can be read in full here , chronicled the events of the day as accurately as possible and provided recommendations to prevent future attacks.

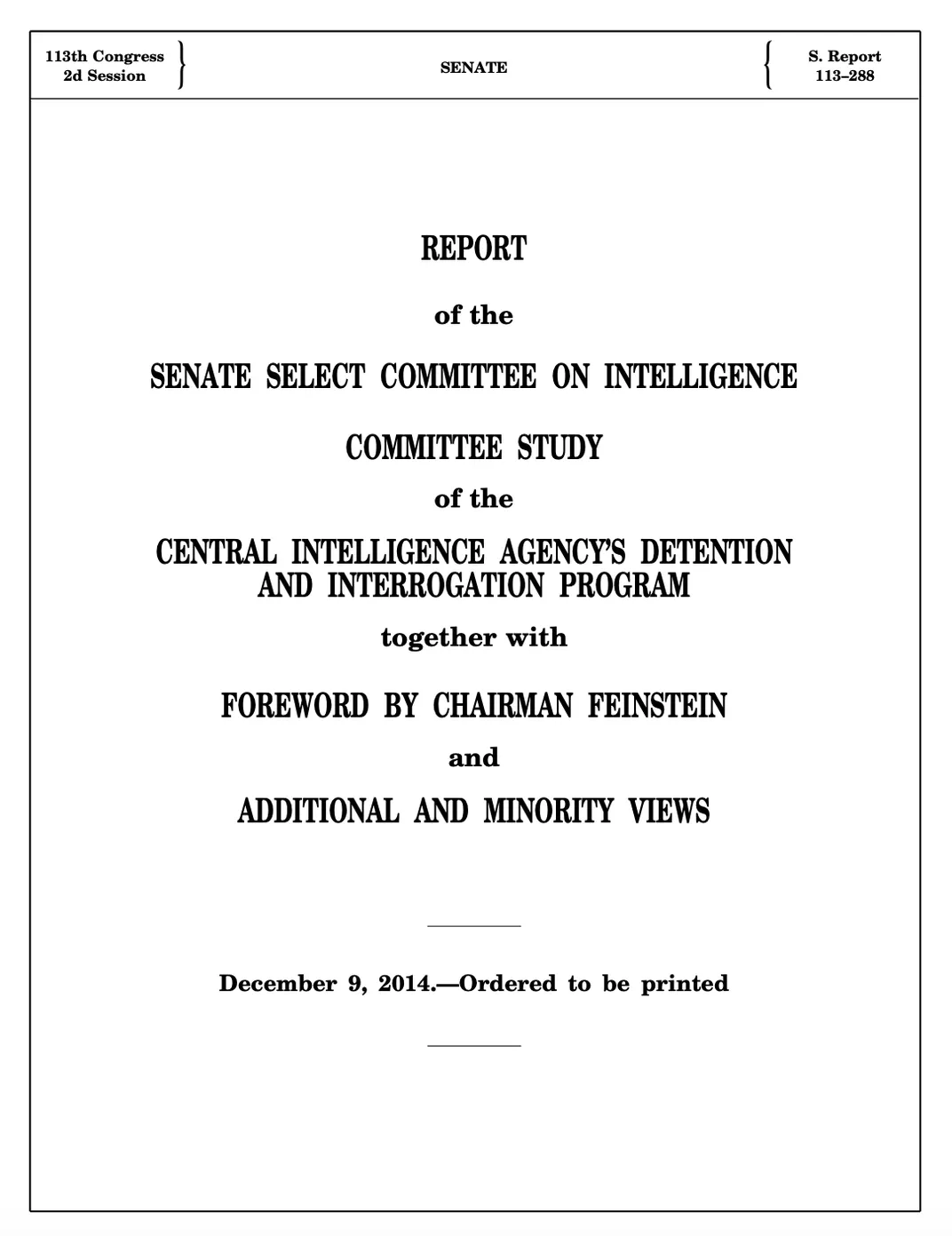

U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence

Within three years of the attacks, the United States had launched wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The military also opened Guantanamo Bay detention camp, a U.S. military prison in Cuba, as part of a series of aggressive anti-terrorism military operations.

In 2014, the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released an investigative report detailing the CIA’s use of torture and other human rights abuses inflicted on prisoners at Guantanamo and elsewhere during the so-called “War on Terror.” Though the full document remains classified, members of the public can read the committee’s executive summary, findings and conclusions online .

The New York Times

On the tenth anniversary of the attacks, the New York Times created an expansive hub for educators seeking to explain 9/11 and its impact on the world to students. Free resources include lesson plans, activities and readings that address complex subjects such as the war in Afghanistan and racism against Muslim Americans.

A separate anniversary collection designed for adult readers is available online, too. Highlights include more than 2,500 “ impressionistic sketches ” of lives lost, an interactive reconstruction of the World Trade Center as it stood prior to the attacks and a feature article on Muslim Americans who came of age in the decade following 9/11.

The Washington Post

In 2019, a protracted legal battle mounted by the Washington Post successfully secured the release of a series of interviews with high-ranking officials about the war in Afghanistan. Reporter Craig Whitlock published the Post ’s first survey of the papers in an article titled “ At War With the Truth ”; the story was later turned into a book .

As Whitlock reported, the documents “reveal[ed] that senior U.S. officials failed to tell the truth about the war in Afghanistan throughout the 18-year campaign, making rosy pronouncements they knew to be false and hiding unmistakable evidence the war had become unwinnable.” Readers can explore the Post ’s reporting, feedback from the public and interviewees, timelines of the war, and more than 2,000 pages of documents online.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

Nora McGreevy | | READ MORE

Nora McGreevy is a former daily correspondent for Smithsonian . She is also a freelance journalist based in Chicago whose work has appeared in Wired , Washingtonian , the Boston Globe , South Bend Tribune , the New York Times and more.

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Impact of 9/11 Terrorist Attacks on Research Agenda

Archival notice.

This is an archive page that is no longer being updated. It may contain outdated information and links may no longer function as originally intended.

The pressing need to respond to the disaster of 9/11, understand terrorist behavior and prevent future terrorist acts has shaped NIJ's research, development and evaluation agenda. Since the attacks, the Institute has brought its expertise in forensics, technology and social science to bear on various areas related to terrorism. We have worked in a number of areas:

DNA Identification in Mass Disasters

Improving the criminal justice response to terrorism incidents, assessing potential high-risk targets, terrorist links to other crimes, terrorism's organization, structure and culture, barriers to interagency coordination when responding to terrorist incidents, analyzing terrorism databases.

Lessons Learned From 9/11: DNA Identification in Mass Fatality Incidents, 2006 . The Kinship and Data Analysis Panel (KADAP) is a blue-ribbon panel of forensic scientists assembled by NIJ after the 9/11 attacks to support New York City's Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in the identification — through DNA analysis — of the World Trade Center victims. This is a report prepared by a group of the nation's top forensic scientists and published by NIJ that reviews the experiences of the KADAP. The report offers guidance (particularly to the nation's laboratory directors) on preparing a plan for responding to a mass fatality event. See Lessons Learned From 9/11: DNA Identification in Mass Fatality Incidents, 2006 .

Mass Fatality Incidents: A Guide for Human Forensic Identification, 2005 . This Special Report provides medical examiners and coroners with guidelines for preparing their disaster plan with regard to victim identification and summarizes the victim identification process for other first responders. It discusses the integration of the medical examiner or coroner into the initial response process and describes the roles of various forensic disciplines (including forensic anthropology, radiology, fingerprinting, and DNA analysis) in victim identification. This report represents the experience of dozens of federal, state, international and private forensic experts who took part in the Technical Working Group for Mass Fatality Forensic Identification. See Mass Fatality Incidents: A Guide for Human Forensic Identification, 2005

Identifying Victims Using DNA: A Guide for Families, 2005. This guide for grieving family members was distributed to victims' families after the 9/11 attacks to help explain the DNA identification process of identifying the remains of a victim through DNA analysis to the public. See Identifying Victims Using DNA: A Guide for Families (pdf, 13 pages) . This document is also available in Spanish (pdf, 14 pages) .

Learning From 9/11: Comparative Case Studies of the Law Enforcement Response, 2009. NIJ funded a study of the two law enforcement agencies that dealt most directly with 9/11 — the New York City Police Department and the Arlington County Police Department. The study found the following: counterterrorism policing is the same as crime policing, the first response priority is to save lives, both departments have greatly expanded counterterrorism training at all levels, and setting up a media relations plan is essential for getting accurate information to victims' family members and the public. See the Research for Practice: Learning From 9/11: Organizational Change in the New York City and Arlington County, Va., Police Departments .

Through-the-Wall Surveillance for Locating Individuals Within Buildings, 2008. NIJ is developing a system that will give law enforcement officers the ability to remotely see people moving within buildings, as opposed to having to place the sensor close to a building wall, thereby lessening law enforcement personnel's exposure to unknown danger. See the final report Standoff Through-the-Wall Imaging Sensor . NIJ also funded the development of a portable device that, while it must be put in close proximity to a building, should be able to detect people who are hiding or trapped behind metal walls or in shipping containers. See the final report Through-the-Wall Surveillance for Locating Individuals Within Buildings.

Improving the Relationship Between Law Enforcement and Arab-American Communities, 2006. NIJ funded one of the first studies to examine the effects of 9/11 on law enforcement agencies and communities with high concentrations of Arab-American residents. The study found that Arab-Americans expressed greater concern about being victimized by federal policies than by individual acts of harassment. In all cases, law enforcement and community members expressed a desire for improved relations. Nonetheless, few jurisdictions actively adopted programs or policies to improve relations. See the final report Law Enforcement and Arab American Community Relations After September 11, 2001: Engagement in a Time of Uncertainty .

Biometrics Research: Facial and Iris Recognition, 2006. NIJ funded research to produce facial recognition software that extracts facial images from surveillance video, rotates the images in three dimensions, and combines them to produce a single recognizable image. See "Recognize the Face." Another NIJ-funded project evaluated the use of iris recognition technology in New Jersey schools and research in a Navy brig and dozens of U.S. jails on the use of iris scanners to track movements. See the final report Safe Kids, Safe Schools: Evaluating the Use of Iris Recognition Technology in New Egypt, NJ.

Communications Technology. NIJ is developing technologies that will provide law enforcement first responders ready access to the radio spectrum they need, when and where they need it, under all circumstances. These efforts include development of advanced antenna concepts and development of cognitive and software defined radios. Additionally, NIJ has taken a leading role within the Department of Justice in efforts to implement the proposed national public safety broadband network.

Digital Forensics. Mobile devices, such as cell phones, are widely used by terrorists and other criminals. The ability to extract forensic data from them is vital. NIJ funding has resulted in the development and introduction of various forensic tools to extract information from mobile digital devices and computer systems. See Digital Evidence and Forensics Web pages .

Protective Equipment. The 9/11 attacks illustrated how law enforcement officers might be called to respond to a variety of situations that previously had been associated with military actions. NIJ is working to ensure the safety of law enforcement officers. In these efforts NIJ consistently partners with the U.S. Departments of Defense and Homeland Security. Products under development include a portable system to decontaminate law enforcement equipment after exposure to pathogens, puncture-resistant gloves to protect the law enforcement responder from various hazards, a full-face respirator (gas mask) that meets the tactical needs of the law enforcement responder, and a duty uniform that offers the law enforcement responder limited protection from chemical, biological and fire hazards.

Standards and Guides. NIJ has published or is in the process of developing a number of standards and guides for equipment that first responders and law enforcement officers can use in preventing, preparing for and responding to terrorism events:

- Protection. NIJ and a number of partners developed a standard for an ensemble to protect law enforcement officers from chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) threats. The standard is the first of its kind to address the specific needs of law enforcement (such as the need to handle firearms and the need for the ensembles to be inconspicuous). See the CBRN Protective Ensemble Standard for Law Enforcement, NIJ Standard-0116.00, 2011. In addition, NIJ produced guides for selecting first responder equipment, such as the Guide for the Selection of Chemical and Biological Decontamination Equipment for Emergency First Responders, NIJ Guide 103-00 (pdf, 96 pages) . NIJ is also developing a performance standard for the protective ensembles worn by bomb technicians to protect them against improvised explosive devices, or IEDs.

- Robots. NIJ is developing and evaluating standards for robotic products. In collaboration with the Department of Homeland Security and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIJ funding led to the development and publication of a comprehensive set of standard test methods and metrics for emergency response robots. The goal was to improve the logistics and safety of remotely operated robots in urban settings. Learn more: Standard Test Methods for Response Robots (pdf, 94 pages) . Read NIJ's assessment of the Vanguard robot technology (pdf, 6 pages).

- Weapons Detection. NIJ has developed standards for both hand-held and walk-through weapons and contraband detectors as well as portable x-ray systems for defeating improvised explosive devices (IEDs). See information about the portable X-ray system .

Improvised Explosive Device (IED) Defeat. Current research and development efforts include development of a universal cutting tool that will interface with any of the existing common robots such as the Andros series, Talon, Pacbot and Vanguard. The Institute also sponsors annual publication of the National Strategic Plan for U.S. Bomb Squads in collaboration with DOD's TSWG.

Surveillance and detection systems. NIJ is developing a range of technologies that can detect concealed weapons and spot unusual activity that could be related to criminal behavior.

- The Sago ST-150 standoff detector is a system to detect weapons concealed under clothing. It is now being used in U.S. government and military applications.

- Other efforts are underway to develop a smart closed-circuit television (CCTV system) and an intelligent, unobtrusive, real-time, continuous monitoring system for assessing activity and predicting emergent suspicious and criminal behavior across a network of distributed cameras.

Securing America’s Passenger Rail Systems, 2007. NIJ funded a study that found that although bombings are the most prevalent terrorist threat to rail systems, most bombings produce few fatalities or injuries. The study also identified 17 options for improving security, some of which are relatively inexpensive. The study also provided transit security managers with a method to evaluate approaches to increasing security and gave practical guidance about how to improve safety efficiently and economically. See the final report Securing America’s Passenger Rail Systems, 2007.

Protecting America’s Ports: Assessing Coordination Between Law Enforcement and Industrial Security, 2007. NIJ funded a study that obtained information about security systems in all 185 American seaports and examined how public-private partnerships operate and focus on terrorism around ports. The study identified a number of promising practices for preventing and preparing for attacks. See the final report Protecting America’s Ports: Assessing Coordination Between Law Enforcement and Industrial Security .

Identifying Links Between White Collar Crime and Terrorism, 2004. NIJ funded a study of the investigation and prosecution of members of a terrorist group (Jamaat Ul Fuqra) in Colorado, identifying the types of white-collar crimes used for funding and identity deception. The study described lessons learned from white-collar crime investigations and provided guidance for state and local police and prosecutors. See the final report Identifying Links Between White Collar Crime and Terrorism .

Methods and Motives: Exploring Links Between Transnational Organized Crime and International Terrorism, 2005. NIJ funded a study that analyzed the overlap between international organized crime and terrorist groups to develop watch points and indicators of convergence, using open-source information and intelligence analysis tools. See the final report Methods and Motives: Exploring Links Between Transnational Organized Crime and International Terrorism .

Terrorist Recruitment in American Correctional Institutions: An Exploratory Study of Nontraditional Faith Groups, 2007. NIJ funded a study on nontraditional religions in U.S. correctional institutions. The study identified the personal and social motivations for incarcerated individuals' conversions to these faith groups and assessed the risk for terrorist recruitment among these persons. The study found that the danger to U.S. security from adherents to these nontraditional faiths is not the number of adherents, but rather the potential for small groups of radical believers to instigate terrorist acts upon their release from custody. See the final report Terrorist Recruitment in American Correctional Institutions: An Exploratory Study of Non-Traditional Faith Groups

Organizational Learning and Islamic Militancy, 2008. NIJ funded a study exploring how Islamic terrorists learn to design and execute attacks. The study assessed the Internet's role in facilitating the teaching of terrorist tactics and strategies, and it identified limitations in Islamic terrorists' ability to acquire knowledge on how to design and execute effective attacks. The study found that terrorists' learning is based mostly on hands-on training from other terrorists. The study also found that many terrorist conspiracies are compartmentalized, impeding the free flow of information between novices and more experienced terrorists. See the final report Organizational Learning and Islamic Militancy .

Interagency Coordination: A Case Study of the 2005 London Train Bombings, 2008, and Interagency Coordination: Lessons Learned From the 2005 London Train Bombings, 2008. Researchers produced a two-part series for the NIJ Journal on interagency coordination in responding to the 2005 train bombings in London, England. The articles focus on lessons learned and promising practices for addressing barriers to interagency coordination when responding to large-scale emergencies. See Interagency Coordination: A Case Study of the 2005 London Train Bombings and Interagency Coordination: Lessons Learned From the 2005 London Train Bombings .

Cross-National Comparison of Interagency Coordination Between Law Enforcement and Public Health, 2005. NIJ funded a study examining the cooperative roles of law enforcement and public health in responding to terrorist threats in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Ireland. The study found common barriers to working together and suggested several measures for successful interagency coordination. See the final report Cross-National Comparison of Interagency Coordination Between Law Enforcement and Public Health .

Building a Global Terrorism Database (University of Maryland). NIJ funded a project to computerize and assess the validity of the original Pinkerton Global Intelligence Service (PGIS) data, which were designed to document every known terrorism event across countries and time frames. The PGIS data collection ended in 1997, exactly the same time that the RAND Corporation began collecting worldwide terrorist incident data. A project at START, the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, brought the data together to produce a geocoded, integrated terrorism event database stretching from 1970 to the present. The database now includes more than 98,000 cases, including date and location of the incident, weapons used and nature of the target, number of casualties, and group or individual responsible (when known). It is by far the most extensive and empirically defensible terrorism event database of this type ever assembled. See the final report Building a Global Terrorism Database .

Pre-Incident Indicators of Terrorist Incidents: The Identification of Behavioral, Geographic, and Temporal Patterns of Preparatory Conduct, 2006. NIJ funded an exploratory analysis of the behavioral, geographic and temporal patterns of preparatory acts to support terrorist events. Researchers found that terrorists typically prepare three to four months before an incident, with measures such as meetings, phone calls, the purchase of supplies and materials, and banking activities (including both bank robbery and legitimate account withdrawals). The spatial analysis revealed that terrorists typically live close to their incident target, with one-half residing and preparing for the incident within 30 miles of the target. See the final report Pre-Incident Indicators of Terrorist Incidents: The Identification of Behavioral, Geographic, and Temporal Patterns of Preparatory Conduct .

Cite this Article

Read more about:.

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

As U.S. cities rethink the role of law enforcement in nonviolent 911 emergencies, new Stanford research uncovers the strongest evidence yet that dispatching mental health professionals instead of police officers in some instances can have significant benefits.

A new study shows dispatching mental health specialists for nonviolent emergencies can be beneficial. In Denver, it reduced reports of less serious crimes and lowered response costs. (Image credit: Getty Images)

The study of a pilot 911 response program in Denver, in which mental health specialists responded to calls involving trespassing and other nonviolent events, finds a 34% drop in reported crimes during the six-month trial. The study by Stanford scholars Thomas Dee and Jaymes Pyne also shows that the direct costs of the alternative 911 approach were four times lower than police-only responses.

“We provide strong, credible evidence that providing mental health support in targeted, nonviolent emergencies can result in a huge reduction in less serious crimes without increasing violent crimes,” says Dee, the Barnett Family Professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR).