Will Healthy Eating Make You Happier? A Research Synthesis Using an Online Findings Archive

- Open access

- Published: 14 August 2019

- Volume 16 , pages 221–240, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ruut Veenhoven ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5159-393X 1 , 2

28k Accesses

10 Citations

128 Altmetric

13 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Healthy eating adds to health and thereby contributes to a longer life, but will it also add to a happier life? Some people do not like healthy food, and since we spend a considerable amount of our life eating, healthy eating could make their life less enjoyable. Is there such a trade-off between healthy eating and happiness? Or instead a trade-on , healthy eating adding to happiness? Or do the positive and negative effects balance? If there is an effect of healthy eating on happiness, is that effect similar for everybody? If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating happiness wise and what kind of people do not? If healthy eating does add to happiness, does it add linearly or is there some optimum for healthy ingredients in one’s diet? I considered the results published in 20 research reports on the relation between nutrition and happiness, which together yielded 47 findings. I reviewed these findings, using a new technique. The findings were entered in an online ‘findings archive’, the World Database of Happiness, each described in a standardized format on a separate ‘findings page’ with a unique internet address. In this paper, I use links to these finding pages and this allows us to summarize the main trends in the findings in a few tabular schemes. Together, the findings provide strong evidence of a causal effect of healthy eating on happiness. Surprisingly, this effect is not fully mediated by better health. This pattern seems to be universal, the available studies show only minor variations across people, times and places. More than three portions of fruits and vegetables per day goes with the most happiness, how many more for what kind of persons is not yet established.

Similar content being viewed by others

How the Exposure to Beauty Ideals on Social Networking Sites Influences Body Image: A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies

Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: What is the Difference?

The Psychology of Mukbang Watching: A Scoping Review of the Academic and Non-academic Literature

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Healthy eating, in particular a diet rich in fruit and vegetables (FV) adds to our health; primarily because it reduces our chances of contracting a number of eating related diseases (Oyebode et al. 2014 ; Bazzano et al. 2002 ; Liu et al. 2000 ). Since good health adds to happiness, it is likely that healthy diets will also add to happiness, but a firm connection has not been established.

In recent years, the relationship between obesity and mental states has begun to attract serious research interest (Becker et al. 2001 ; Rooney et al. 2013 ), as has the relationship between specific micro-nutrients and psychological health (Stough et al. 2011 ). As yet, there is little research on the relationship between nutrition and happiness.

It is worth knowing to what extent our eating habits affect our happiness. One reason is that most people are concerned about their happiness and look for ways to increase it. Most determinants of happiness are beyond our control, but what we eat is largely in our own hands. In this context, we would like to know whether there is a trade-off between healthy eating and happy living. Gains in length of life due to healthy eating may be counterbalanced by loss of satisfaction with life, as is argued in the debate on the benefits of drinking alcohol (Baum-Baicker 1985 ). If so, healthy eating may mean that we live longer, but not happier.

Empirical assessment of the effects of healthy eating on happiness is fraught with complications. One complication is that the effect of nutrition is probably not the same for everybody. Hence, we must identify what food pattern is optimal for what kind of person. A second problem is that happiness can influence nutrition behaviour, for example unhappiness can lead to the consumption of unhealthy comfort foods. Cause and effect must be disentangled. If a healthy diet does appear to add to happiness, then a third question arises: Is eating more healthy food always better or is there an optimum amount one should eat? For instance, is one apple a day enough to make us feel happy? Or will we feel better with four daily portions of fruit? How about small sins, such as a bar of chocolate or a daily glass of wine?

Research Questions

Is there a trade-of or between healthy eating and happiness? Or rather a trade-on , healthy eating adding to happiness? Or do the positive and negative effects balance?

Is this effect of healthy eating on happiness similar for everybody? If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating and what kind of people do not?

Is the shape of the relationship between healthy eating and happiness linear? The healthier one’s diet, the happier one is? Or is there an optimum?

I explored answers to these three questions in the available research literature and took stock of the findings obtained in quantitative studies on the relation between healthy eating and happiness. I applied a new technique for research reviewing, that takes advantage of an on-line findings archive, the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018a ), which allows us to present a lot of findings in a few easy to oversee tabular schemes.

To my knowledge, the research literature on this subject has not been reviewed as yet. One review has considered the observed effect of eating fruit and vegetables on psychological well-being (Rooney et al. 2013 ), however, this review does not really deal with happiness, as will be defined in “ Happiness ” section, but is about mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

Structure of the Paper

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. I define the key concepts in “ Concepts and Measures ” section; healthy eating and happiness and give a short account of happiness research. Next, I describe the new review technique in more detail: how the available research findings were gathered and how these are presented in an easy to overview way ( Methods section). Then I discuss what answers the available findings have provided for our research questions ( Results section). I found a clear answer to the first research question, but no clear answers to the second and third question. I discuss these findings in “ Discussion ” section and draw conclusions in “ Conclusions ” section.

Concepts and Measures

There are different view on what constitutes ‘healthy eating’ and ‘happiness’; for this reason, a delineation of these notions is required.

Healthy Eating

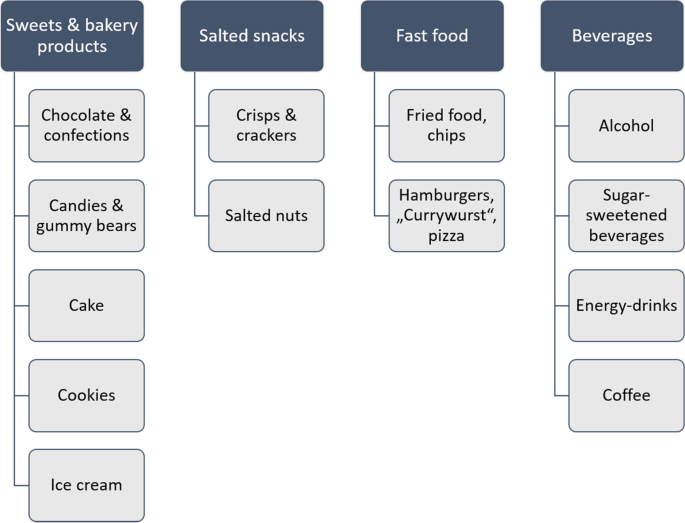

I follow the WHO ( 2018 ) characterization of a ‘healthy diet’ as involving’: 1) a varied diet, 2) rich in fruit and vegetables 3) a moderate amount of fats and oil and 4) less salt and sugar than usual these days. The typical Mediterranean diet is considered to fit these demands well. Unhealthy foods are considered to be rich in sugar and fat, such as processed meat, fast foods, sweets, cakes, sodas, deserts, alcohol and other foods high in calories, but low in nutritional content.

Throughout history, the word happiness has been used to denote different concepts that are loosely connected. Philosophers typically used the word to denote living a good life and often emphasize moral behaviour. ‘Happiness’ has also been used to denote good living conditions and associated with material affluence and physical safety. Today, many social scientists use the word to denote subjective satisfaction with life , which is also referred to as subjective well-being (SWB).

Definition of Happiness

In that latter line, I defined happiness as the degree to which an individual judge the overall quality of his/her life-as-a-whole favourably Footnote 1 (Veenhoven 1984 ) and in a later paper distinguished this definition of happiness from other notions of the good life (Veenhoven 2000 ). In this paper, I follow this conceptualization as it is also the focus of the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018a ) from which the data reported in this paper are drawn.

Components of Happiness

Our overall evaluation of life draws on two sources of information: a) how well one feels most of the time and b) to what extent one perceives one is getting from life what one wants from it. I refer to these sub-assessments as ‘components’ of happiness, called respectively ‘hedonic level of affect’ and ‘contentment’ (Veenhoven 1984 ). The affective component tends to dominate in the overall evaluation of life (Kainulainen et al. 2018 ).

The affective component is also known as ‘affect balance’, which is the degree to which positive affective (PA) experiences outweigh negative affective (NA) experiences Positive experience typically signals that we are doing well and encourages functioning in several ways (Fredrickson 2004 ) and protects health (Veenhoven 2008 ). As such, this aspect of happiness was particularly interesting for this review of effects of healthy eating.

Difference with Wider Notions of Wellbeing

Happiness in the sense of the ‘subjective enjoyment of one’s life-as-a-whole’, should not be equated with satisfaction with domains of life, such as satisfaction with one’s life-style, one’s diet in particular. Likewise, happiness in the sense of the ‘subjective enjoyment of one’s life’ should not be equated with ‘objective’ notions of what is a good life, which are sometimes denoted using the same term. Though strongly related to happiness, mental health is not the same; one can be pathologically happy or be happy in spite of a mental condition.

Differences in wider notions of well-being are discussed in more detail in Veenhoven (15).

Measurement of Happiness

Since happiness is defined as something that is on our mind, it can be measured using questioning. Various ways of questioning have been used, direct questions as well as indirect questions, open questions and closed questions and one-time retrospective questions and repeated questions on happiness in the moment.

Not all questions used fit the above definition of happiness adequately, e.g. not the question whether one thinks one is happier than most people of one’s age, which is an item in the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyobomirsky and Lepper 1999 ). Findings obtained using such invalid measures are not included in the World Database of Happiness and hence were not considered in this research synthesis. Further detail on the validity assessment of questions on happiness is available in the introductory text to the collection Measures of Happiness of the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018b ) chapter 4. Some illustrative questions deemed valid for archiving in the WDH are presented below.

Question on overall happiness:

Taking all together, how happy would you say you are these days?

Questions on hedonic level of affect:

Would you say that you are usually cheerful or dejected?

How is your mood today? (Repeated several days).

Question on contentment:

How important are each of these goals for you?

How successful have you been in the pursuit of these goals?

Happiness Research

Over the ages, happiness has been a subject of philosophical speculation and in the second half of the twentieth century it also became the subject of empirical research. In the 1960’s, happiness appeared as a side-subject in research on successful aging (Neugarten et al. 1961 ) and mental health (Gurin et al. 1960 ). In the 1970’s happiness became a topic in social indicators research (Veenhoven 2017 ) and in the 1980s in medical quality of life research (e.g. Calman 1984 ). Since the 2000’s, happiness has become a main subject in the fields of ‘Positive psychology’ (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005 ) and ‘Happiness Economics’ (Bruni and Porta 2005 ). All this has resulted in a spectacular rise in the number of scholarly publications on happiness and in the past year (2017) some 500 new research reports have been published. To date (May 2018), the Bibliography of Happiness list 6451 reports of empirical studies in which a valid measure of happiness has been used (Veenhoven 2018c ).

Findings Archive: The World Database of Happiness

This flow of research findings on happiness has grown too big to oversee, even for specialists. For this reason, a findings archive has been established, in which quantitative outcomes are presented in a uniform format and are sorted by subject. This ‘World Database of Happiness’ is freely available on the internet at https://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl

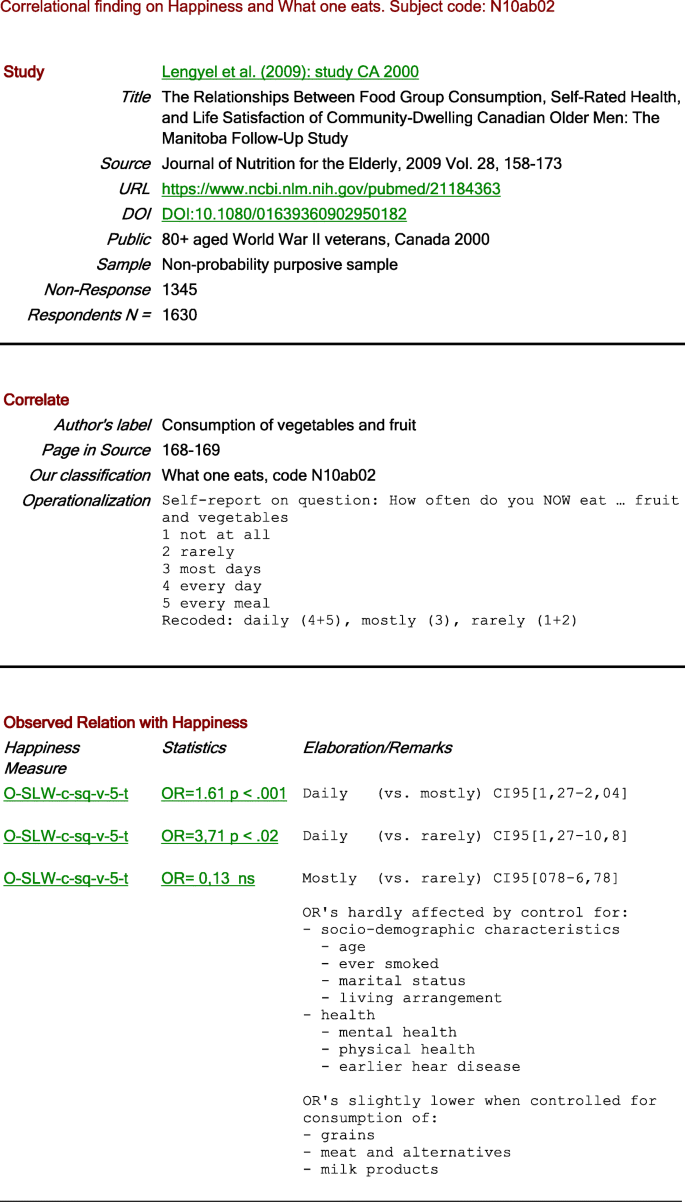

Its structure is shown on Fig. 1 and a recent description of this novel technique for the accumulation of research findings can be found with Veenhoven ( 2019 ).

Start page of the World Database of Happiness, showing the structure of this findings archive

One of the subject categories in the collection of correlational findings is ‘Happiness and Nutrition’ (Veenhoven 2018c ). I draw on that source for this paper.

A first step in this review was to gather the available quantitative research findings on the relationship between happiness and healthy eating. The second step was to present these findings in an uncomplicated form.

Gathering of Research Findings

In order to identify relevant papers for this synthesis, I inspected which publications on the subject of healthy eating were already included of the Bibliography of World Database of Happiness, in the subject sections ‘ Health behaviour’ and consumption of ‘ Food ’. Then to further complete the collection of studies, various databases were searched such as Google Scholar, EBSCO, ScienceDirect, PsycINFO, PubMed/Medline, using terms such as ‘ happiness ’, ‘ life satisfaction ’, ‘ subjective well-being ’, ‘ well-being ’, ‘ daily affect ’, ‘ positive affect ’, ‘ negative affect ’ in connection with terms such as ‘ food ’, ‘ healthy food ’, ‘ fruit and vegetables ’, ‘ fast food ‘and ‘ soft drinks ’ in different sequences.

All reviewed studies had to meet the following criteria:

A report on the study should be available in English, French, German or Spanish.

The study should concern happiness in the sense of life-satisfaction (cf. Healthy Eating section). I excluded studies on related matters, such as on mental health or wider notions of ‘flourishing’.

The study should involve a valid measure of happiness (cf. Happiness section). I excluded scales that involved questions on different matters, such as the much-used Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985 ).

The study results had to be expressed using some type of quantitative analysis.

Studies Found

Together, I found 20 reports of an empirical investigation that had examined the relationship between healthy eating and happiness, of which two were working papers and one dissertation. None of these publication s reported more than one study . Together, the studies yielded 47 findings.

All the papers were fairly recent, having been published between 2005 and 2017. Most of the papers (44.4%) were published in Medical Journals, including the International Journal of Behavioural Medicine, Journal of Health Psychology, The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, The Journal of Psychosomatic Research, The International Journal of Public Health, and Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology.

People Investigated

Together, the studies covered 149.880 respondents and 27 different countries. The publics investigated in these studies, included the general population in countries and particular groups such as students, children, veterans and medical patients. The majority of respondents belonged to a general public group (50%), students made up 27.8%, with children and veterans each forming 11.1%.

Research Methods Used

Most of the studies were cross-sectional 64.4%, longitudinal and daily food diaries accounted for 22% and 10.2% of the total number of studies respectively, and one experimental study accounted for 3.4%.

I present an overview of all the included studies, including information about population, methods and publication in Table 1 .

Format of this Research Synthesis

As announced, I applied a new technique of research reviewing, taking advantage of two technical innovations: a) The availability of an on-line findings-archive (the World Database of Happiness) that holds descriptions of research findings in a standard format and terminology, presented on separate finding pages with a unique internet address. b) The change in academic publishing from print on paper to electronic text read on screen, in which links to that online information can be inserted.

Links to Online Detail

In this review, I summarize the observed statistical relationships as +, − or 0 signs. Footnote 2 These signs link to finding pages in the World Database of Happiness, which serves as an online appendix in this article. If you click on a sign, one such a finding page will open, on which you can see full details of the observed relationship; of the people investigated, sampling, the measurement of both variables and the statistical analysis. An example of such an electronic finding page is presented in Fig. 2 . This technique allows me to present the main trends in the findings, without burdening the reader with all the details, while keeping the paper to a controllable size, at the same time allowing the reader to check in depth any detail they wish.

Example of an online findings page

Organization of the Findings

I first sorted the findings by the research method used and these are presented in three separate tables. I distinguished a) cross-sectional studies, assessing same-time relationships between diet and happiness (Table 2 ), b) longitudinal studies, assessing change in happiness following changes in diet (Table 3 ), and c) experimental studies, assessing the effect of induced changes in diet on happiness (Table 4 ).

In the tables, I distinguish between studies at the micro level, in which the relation between diet and happiness of individuals was assessed and studies at the macro level, in which average diet in nations is linked to average happiness of citizens.

I present kinds of foods consumed vertically and horizontally two kinds of happiness: overall happiness (life-satisfaction) and hedonic level of affect.

Presentation of the Findings

The observed quantitative relationships between diet and happiness are summarized using 3 possible signs: + for a positive relationship, − for a negative relationship and 0 for a non-relationship. Statistical significance is indicated by printing the sign in bold . See Appendix . Each sign contains a link to a particular finding page in the World Database of Happiness, where you can find more detail on the checked finding.

Some of these findings appear in more than one cell of the tables. This is the case for pages on which a ‘raw’ (zero-order) correlation is reported next to a ‘partial’ correlation in which the effect of the control variables is removed. Likewise, you will find links to the same findings page at the micro level and the macro level in Table 2 ; on this page there is a time-graph of sequential studies in Russia from which both micro and macro findings can be read.

Several cells in the tables remain empty and denote blanks in our knowledge.

Advantages and Disadvantages of this Review Technique

There are pros and cons to the use of a findings-archive such as the World Database of Happiness and plusses and minuses to the use of links to an on-line source in a text like this one.

Use of a Findings-Archive

Advantages are: a) efficient gathering of research on a particular topic, happiness in this case, b) sharp conceptual focus and selection of studies on that basis, c) uniform description of research findings on electronic finding pages, using a standard format and a technical terminology, d) storage of these finding pages in a well searchable database, e) which is available on-line and f) to which links can be made from texts. The technique is particular useful for ongoing harvesting of research findings on a particular subject.

Disadvantages are: a) the sharp conceptual focus cannot easily be changed, b) considerable investment is required to develop explicit criteria for inclusion, definition of technical terms and software, Footnote 3 c) which pays only when a lot of research is processed on a continuous basis.

Use of Links in a Review Paper

The use of links to an on-line source allows us to provide extremely short summaries of research findings, in this text by using +, − and 0 signs in bold or not, while allowing the reader access to the full details of the research. This technique was used in an earlier research synthesis on wealth and happiness (Jantsch and Veenhoven 2019 ) and is described in more detail in Veenhoven ( 2019 ). Advantages of such representation are: a) an easy overview of the main trend in the findings, in this case many + signs for healthy foods, b) access to the full details behind the links, c) an easy overview of the white spots in the empty cells in the tables, and d) easy updates, by entering new sign in the tables, possibly marked with a colour.

The disadvantages are: a) much of the detailed information is not directly visible in the + and – signs, b) in particular not the effect size and control variables used, and c) the links work only for electronic texts.

Differences with Traditional Reviewing

Usual review articles cannot report much detail about the studies considered and rely heavily on references to the research reports read by the reviewer, which typically figure on a long list at the end of the review paper that the reader can hardly check. As a result, such reviews are vulnerable to interpretations made by the reviewer and methodological variation can escape the eye.

Another difference is that the conceptual focus of many traditional reviews in this field is often loose, covering fuzzy notions of ‘well-being’ rather than a well-defined concept of ‘happiness’ as used here. This blurs the view on what the data tell and involves a risk of ‘cherry picking’ by reviewers. A related difference is that traditional reviews of happiness research often assume that the name of a questionnaire corresponds with its conceptual contents. Yet, several ‘happiness scales’ measure different things than happiness as defined in “ Healthy Eating ” section, e.g. much used Life Satisfaction Scale (Neugarten et al. 1961 ), which measures social functioning.

Still another difference is that traditional narrative reviews focus on interpretations advanced by authors of research reports, while in this quantitative research synthesis I focus on the data actually presented. An example of such a difference in this review, is the publication by Connor & Brookie (Conner et al. 2015 ) who report no effect of healthier eating on mood in the experimental group, while their data show a small but significant gain in positive affect and a small but insignificant reduction of negative effect (Table 3 ), which together denote a positive effect on affect balance.

Difference with Traditional Meta-Analysis

Though this research synthesis is a kind of meta-analysis, it differs from common meta-analytic studies in several ways. One difference is the above- mentioned conceptual rigor; like narrative reviews many meta-analyses take the names given to variables for their content thus adding apples and oranges. Another difference is the direct online access to full detail about the research findings considered, presented in a standard format and terminology, while traditional meta-analytic studies just provide a reference to research reports from which the data were taken. A last difference is that most traditional meta-analytic studies aim at summarizing the research findings in numbers, such as an average effect size. Such quantification is not well possible for the data at hand here and not required for answering our research questions. My presentation of the separate findings in tabular schemers provides more information, both of the general tendency and of the details.

Let us now revert to the research questions ( Structure of the Paper section) and answer these one by one.

Is there a Trade-Of between Healthy Eating and Happiness?

Or does healthy eating rather add to happiness or do the positive and negative effects balance.

This question was addressed using different methods, a) same-time comparison of diet and happiness (cross-sectional analysis) b) follow-up of change in happiness following change in diet (longitudinal) and c) assessing the effect on happiness of induced change in diet (experimental). The results are summarized in, respectively, Tables 2 , 3 and 4 .

Cross-Sectional Findings

Together I found 42 correlational findings, which are presented in Table 2 . Of these findings 14 concerned raw correlations, while 28 reflected the results of a multivariate analysis. In Table 2 I see only micro level studies.

There were 16 + signs, which indicates that people who eat healthy tend to be happier than people who do not. A few (3) – signs were linked to unhealthy eating habits, i.e. fast food, soft drinks and sweets, and as such support this pattern.

Not all the findings supported the view that healthy eating goes with greater happiness. Consumption of soft-drinks was positively related to overall happiness, though not significantly, while the correlation with affect balance was significantly negative. A high intake of high caloric protein and fat is generally deemed to be unhealthy but appeared in one case to go with greater overall happiness, a study among medical patients in Arkhangelsk in Russia, where the medical conditions and cold climate may have require a higher intake of such foods.

The findings were mixed with respect to the relation of happiness with consumption of animal products, dairy and meat. For these foods a positive relation with overall happiness was found and a negative relation with affect level, in the case of milk products both relations were insignificant.

Several studies report both raw correlations and partial ones for the same population. Controls reduced the effect size somewhat but did not change the direction of the correlation. Importantly, the control for health and other health behaviours in 8 studies Footnote 4 did not change the direction of the correlation.

Longitudinal Findings

The findings of two studies that assessed the change in happiness following change in diet are presented in Table 3 , one study at the micro level among students and another study at the macro-level among the general population in Russia. Both studies found positive correlations, indicating that healthier eating adds to one’s happiness. The effects of greater consumption of meat and milk were not significant. No control variables were used in these studies. The relationship between healthy eating and affect level was not investigated longitudinally.

Experimental Study

To date, there is only one study on the effect of induced change to a healthier diet on an individual’s happiness. In this study people were randomly assigned to an experimental group and stimulated in various ways to consume more fruit and vegetables (FV), among other things by providing vouchers for health foods and sending e-mail reminders. After 2 weeks of increased FV consumption, the participant’s mood level had increased more than those of the control group.

Together, these findings provide a clear answer to our first research question. The net effect of healthy eating on happiness tends to be positive. If there is any trade-off at all, this is apparently more than compensated by the trade-on . The positive relationship is robust across research methods and measures of happiness.

Is this Effect of Healthy Eating on Happiness Similar for Everybody?

If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating and what kind of people do not.

The 19 studies reported here cover a wide range of populations, the general public in several parts of the world, children, students, church members, medical patients and elderly war veterans. No great differences in the correlation between diet and happiness appear in these findings, though children seem to be happier when allowed to consume sweets and soft drinks. The cross-national study by Grant et al. ( 2009 ) observed some differences in strength of the correlation between healthy eating and happiness across part of the world, but no difference in direction of the correlation. The micro-level studies by Pettay ( 2008 ) and Warner et al. ( 2017 ) found no differences between males and females, while Ford et al. ( 2013 ) found a slightly bigger negative effect of unhealthy eating among women than among men.

The observed positive effect of healthy eating on happiness seems to be universal. Possible differences in what diet provides the most happiness for whom have not (yet) been identified.

Is the Shape of The Relationship Linear; the Healthier One’s Diet, the Happier One Is?

Or is there an optimum, if so what is optimal for whom.

Two studies find a linear relation between happiness and the number of portions fruits and vegetables per day, Lesani et al. ( 2016 ) among students in Iran and Blanchflower et al. ( 2013 ) among the general public in the UK, the latter study up to 7–8 portion a day. Another study observed an optimum at the lower level of 3–4 portions a day among female Iranian students (Fararouei et al. 2013 ). These thee studies suggest that the optimum is at least beyond three portions a day. As yet the focus of research has been on particular kinds of food, while the relationship between happiness and total diet composition has not been investigated.

Together, our findings leave no doubt that healthy eating ads to happiness, frequent consumption of fruit and vegetables in particular.

Causal Effect

Though happiness may influence nutrition behaviour, happier people being more inclined to follow a healthy diet, there is strong evidence for a causal effect of healthy eating on happiness. Spurious correlation is unlikely to exist, since correlations remain positive after controlling for many different variables. Causality is strongly suggested by 3 out of the 4 longitudinal findings and the experimental study.

This is not to say that healthy eating will always add to the happiness of everybody, but the trend is sufficiently universal and strong to be used in policies that aim at greater happiness for a greater number of people, such as in happiness education.

Causal Paths

Healthy eating will add to good health and good health will add to happiness. An unexpected finding is that the effect of healthy eating on happiness is not fully mediated by better health. As mentioned in “ Is there a Trade-Of between Healthy Eating and Happiness? ” section, significant positive correlations remain when health is controlled. This means that healthy eating also affects happiness in other ways. As yet I can only speculate about what these ways are. Possibly effects are that healthy eaters attract nicer people or that intake of fruit and vegetables has a direct effect on mood.

Limitations

This first synthesis of the research on happiness and healthy eating draws on 20 empirical studies, which together yielded 47 findings. Though these results provide strong indications of a positive effect of healthy eating on happiness, we need more research to be sure. This research synthesis limits to happiness defined as the subjective enjoyment of one’s life as a whole and measure that matter adequately. This conceptual focus has a piece, we came to know more about less. The available research findings do not allow a traditional meta-analysis, both because of the limited numbers and their heterogeneity. Hence, we cannot yet compute effect sizes or test statistical significance of differences.

Topics for Further Research

Although we now know that healthy eating tends to make one’s life more satisfying, we do not know in much detail what particular diets are the most conducive to the happiness of what kinds of people. We are also largely in the dark about the causal mechanisms involved. The focus of current research is very much on particular food items, consumption of fruit and vegetables in particular. Future research should pay more attention to the effect of total diets on happiness.

Conclusions

Healthy eating adds to happiness, not just by protecting one’s health but also in other, as yet unidentified, ways. This finding deserves to be drawn to the public’s attention. People should know that changing to a healthier diet will not be at the cost of their happiness but will add to it. Faulty beliefs and misleading advertisements should be counter-balanced by this established fact.

Likewise, Diener (26) defined ‘life satisfaction’ as an overall judgement of one’s life.

The technique also allows summarization in a number, which can be presented in a stem-leaf diagram, or in short verbal. Statements, such as ‘U shaped relationship’

The archive can be easily adjusted for other subjects. The software is Open Source

Blanchflower et al. ( 2013 ); Fararouei et al. ( 2013 ); Ford et al. ( 2013 ); Huffman and Rizov ( 2016 ); Lesani et al. ( 2016 ); Lengyel et al. ( 2009 ) and Kye and Park ( 2014 )

Studies Included in this Research Synthesis Are Marked with a Link below the Reference. The Links Lead to a Standardized Description of that Study in the World Database of Happiness. The Codes Denote Place and Year of the Study

Averina, M. M., Brox, J. & Nilsson, O. (2005) Social and lifestyle determinants of depression, anxiety, sleeping disorders and self-evaluated quality of life in Russia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 40: 511–518 Study RU Archangelsk 1999

Baum-Baicker, C. (1985). The psychological benefits of moderate alcohol consumption: a review of the literature. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 15 (4), 305–322.

Article Google Scholar

Bazzano, L. A., He, J., Ogden, L. G., Loria, C. M., Vupputuri, S., Myers, L., & Whelton, P. K. (2002). Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease in US adults: the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76 (1), 93–99.

Becker, E. S., Margraf, J., Türke, C., Soeder, U., & Neumer, S. (2001). Obesity and mental illness in a representative sample of young women. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders, 25 (Suppl. 1), S5–S9.

Blanchflower, D. G., Oswald, A. J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2013). Is psychological well-being linked to the consumption of fruit and vegetables? Social Indicators Research, 114 , 785–801 Study GB Wales 2007-2010 .

Breslin, G., Donnelly, P., & Nevill, A. M. (2013). Socio-demographic and behavioural differences and associations with happiness for those who are in good and poor health. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 1 , 142–154 Study GB 2009 .

Bruni, L., & Porta, P. L. (2005). Economics and happines . UK: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Caligiuri, S., Lengyel, C. O., & Tate, R. B. (2012). Changes in food group consumption and associations with self-rated diet, health, life satisfaction, and mental and physical functioning over 5 years in very old Canadian men: The Manitoba follow-up study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 16 (8), 707–712 Study CA 2000-2005 .

Calman, A. C. (1984). Quality of life in cancer patients--a hypothesis. Journal of Medical Ethics, 10 , 124–127.

Chang, H. H., & Nayga, R. M., Jr. (2010). Childhood obesity and unhappiness: The influence of soft drinks and fast food consumption. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11 , 261–275 Study TW 2001 .

Conner, T.S. & Brookie, K.L. (2017). Let them eat fruit! The effect of fruit and vegetable consumption on the psychological well-being in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS one , February. 3201 Study NZ Auckland 2015

Conner, T.S., Brookie, K.L. & Richardson, A.C. (2015). On carrots and curiosity: Eating fruit and vegetables is associated with greater flourishing in daily life. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20: 413–444. Study NZ Auckland 2013

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Griffin, S., & Larsen, R. J. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49 , 71–75.

Fararouei, M., Akbartabar Toori, M. & Brown, I.J. (2013). Happiness and health behaviour in Iranian adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence, 36: 1187–1192. Study IR 2008

Ford, P.A., Jaceldo-Siegl, K. & Lee, J.W. (2013). Intake of mediterranean foods associated with positive and low negative affect. Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 74 (2013) 142–148. Study ZZ Anglo-America 2002

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden - and - build theory of positive emotions . Philosophical Transactions, Biological Sciences , 359: 1367–1377.

Grant, N.; Steptoe, A.; Wardle, J. (2009). The relationship between life satisfaction and health behaviour: a cross-cultural analysis of young adults. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine , 16: 259–268 Study ZZ 1999-2001

Gschwandtner, A., Jewell, S. & Kambhampati, U. (2015). On the relationship between lifestyle and happiness in the UK. Paper for 89th Annual Conference of AES, 2015, 1–33, Warwick, England. Study GB 2012

Gurin, G., Feld, S. & Veroff, J. (1960). Americans view their mental health. A nationwide interview survey. Basic Books, New York, USA (Reprint in 1980, Arno Press, New York, USA).

Honkala, S., Al Sahli, N., & Honkala, E. (2006). Consumption of sugar products and associated life- and school- satisfaction and self-esteem factors among schoolchildren in Kuwait. Acta Odonatological Scandinavia, 64 , 79–88 Study KW 2002 .

Huffman, S.K.; Rizov, M. (2016). Life satisfaction and diet: Evidence from the Russian longitudinal monitoring survey. Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting, 2016, 1–25, Boston, Massachusetts. Study RU 1994-2005

Jantsch, A & Veenhoven, R. (2019). Private wealth and happiness: A research synthesis using an online findings archive . In Gael Brule & Christian Suter (Eds.), “Wealth(s) and Subjective Well-Being Springer/Nature, pp 17–50.

Kainulainen, S., Saari, J., & Veenhoven, R. (2018). Life-satisfaction is more a matter of how well you feel, than of having what you want . International Journal of Happiness and Development, 4 (3), 209–235.

Kye, S.K. & Park, K. (2014). Health-related determinants of Happiness in Korean Adults. International Journal of Public Health, 59: 731–738. Study KR 2009

Lengyel, C. O., Oberik Blatz, A. K., & Tate, R. B. (2009). The relationships between food group consumption, self-rated health, and life satisfaction of community-dwelling canadian older men: The manitoba follow-up study. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 28 , 158–173 Study CA 2000 .

Lesani, A., Javadi, M., & Mohammadpoorasl, A. (2016). Eating breakfast, fruit and vegetable intake and their relation with happiness in college students. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 21 , 645–651 Study IR Tehran 2011 .

Liu, S., Manson, J. E., Lee, I. M., Cole, S. R., Hennekens, C. H., Willett, W. C., & Buring, J. E. (2000). Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: The Women’s Health Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72 (4), 922–928.

Lyobomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46 , 137–155.

Lyubomirsky, S., Diener, E., & King, L. A. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131 , 803–855.

Mujcic, R., & Oswald, A. (2016). Evolution of well-being and happiness after increases in consumption of fruit and vegetables. American Journal of Public Health, 106 (8), 1504–1510 Study AU 2007-2009 .

Neugarten, B.L., Havighurst, R.J. & Tobin, S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction . Journal of Gerontology , 16: 134–143.

Oyebode, O., Gordon-Dseagu, V., Walker, A., & Mindell, J. S. (2014). Fruit and vegetable consumption and all-cause, cancer and CVD mortality: analysis of Health Survey for England data. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health, 68 (9), 856–862.

Pettay, R.S. (2008). Health behaviours and life satisfaction in college students . PhD Thesis, Kansas State University, USA. Study US 2006

Rooney, C., McKinley, M.C. & Woodside, J.V. (2013). The Potential Role of Fruit and Vegetables in aspects of Psychological Well-Being: A Review of the Literature and Future Directions. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 72: 420–432.

Stough, C., Scholey, A., Lloyd, J., Spong, J., Myers, S., & Downey, L. A. (2011). The effect of 90-day administration of a high dose vitamin B-complex on work stress. Human Physio-pharmacology, 26 (7), 470–476.

Google Scholar

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness . Reidel (now Springer), Dordrecht, Netherlands.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life. Ordering concepts and measures of the good life . Journal of Happiness Studies, 1 , 1–39.

Veenhoven, R. (2008). Healthy happiness: Effects of happiness on physical health and the consequences for preventive health care . Journal of Happiness Studies, 9 , 449–464.

Veenhoven, R. (2017). Co-development of happiness research: Addition to “fifty years after the social indicator movement . Social Indicators Research , 135: 1001–1007.

Veenhoven, R. (2018a) World database of happiness: Archive of research findings on subjective enjoyment of life . Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Veenhoven, R. (2018b). Measures of happiness . World Database of Happiness, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Veenhoven, R. (2018c). Bibliography of happiness . World Database of Happiness, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Veenhoven, R. (2019). World database of happiness: A ‘findings archive’ . Chapter in Handbook of Wellbeing, Happiness and the Environment. Editors: Heinz Welsch, David Maddison and Katrin Rehdanz, Edward Elgar Publishing (forthcoming).

Warner, R.M., Frye, K. & Morrell, J. S. (2017). Fruit and vegetable intake predicts positive affect. Journal of Happiness Studies , 18: 809–826. Study US New England 2013

WHO (2018) Healthy diet. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Erasmus Happiness Economics Research Organization EHERO, Erasmus University Rotterdam, POB 1738, 3000DR, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Ruut Veenhoven

Optentia Research Program, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ruut Veenhoven .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Signs used in Finding Tables

positive correlation, statistically significant

positive correlation, not statistically significant

positive and negative correlations, depending on control variables used

no correlation

negative correlation, not statistically significant

negative correlation, statistically significant

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Veenhoven, R. Will Healthy Eating Make You Happier? A Research Synthesis Using an Online Findings Archive. Applied Research Quality Life 16 , 221–240 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09748-7

Download citation

Received : 20 December 2018

Accepted : 20 June 2019

Published : 14 August 2019

Issue Date : February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09748-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Health behaviour

- Research synthesis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- BMJ NPH Collections

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Online First

- Qualitative research study on addressing barriers to healthy diet among low-income individuals at an urban, safety-net hospital

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

other Versions

- You are currently viewing an earlier version of this article (January 17, 2023).

- View the most recent version of this article

- Erin Cahill 1 ,

- Stacie R Schmidt 2 ,

- Tracey L Henry 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2791-9960 Gayathri Kumar 3 ,

- Sara Berney 4 ,

- Jada Bussey-Jones 2 and

- Amy Webb Girard 1

- 1 Emory University School of Public Health , Atlanta , Georgia , USA

- 2 Division of General Medicine and Geriatrics , Emory University School of Medicine , Atlanta , Georgia , USA

- 3 Emory University School of Medicine , Atlanta , Georgia , USA

- 4 North Carolina State University School of Public and International Affairs , Raleigh , North Carolina , USA

- Correspondence to Tracey L Henry, General Medicine and Geriatrics, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA; henrytracey{at}hotmail.com

Background Some American households experience food insecurity, where access to adequate food is limited by lack of money and other resources. As such, we implemented a free 6-month Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Program within a large urban safety-net hospital .

Methods 32 participants completed a baseline and postintervention qualitative evaluation about food-related behaviour 6 months after study completion. Deductive codes were developed based on the key topics addressed in the interviews; inductive codes were identified from analytically reading the transcripts. Transcripts were coded in MAXQDA V.12 (Release 12.3.2).

Results The information collected in the qualitative interviews highlights the many factors that affect dietary habits, including the environmental and individual influences that play a role in food choices people make. Participants expressed very positive sentiments overall about their programme participation.

Conclusions A multifaceted intervention that targets individual behaviour change, enhances nutritional knowledge and skills, and reduces socioeconomic barriers to accessing fresh produce may enhance participant knowledge and self-efficacy around healthy eating. However, socioeconomic factors remain as continual barriers to sustaining healthy eating over the long term. Ongoing efforts that address social determinants of health may be necessary to promote sustainability of behaviour change.

- nutritional treatment

- nutrition assessment

- malnutrition

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000064

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Most US households have consistent, reliable access to enough food for active, healthy living. 1 Some American households, however, experience food insecurity, which is defined by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) as a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life. 1 In 2016, an estimated one in eight Americans were food insecure, equating to 42 million people. 1 Food insecurity can be influenced by a number of factors including income, employment and disability (Healthy People 2020). The prevalence of food insecurity varies across subgroups of the US population; some groups are more likely to be food insecure than others. The distribution of food insecurity across residence areas shows that the majority of food-insecure households are in metropolitan areas, with income as one of the primary characteristics associated with food insecurity. 2 Lower income households have a higher prevalence of food insecurity compared with higher income households. 2 Furthermore, food insecurity may increase the risk for obesity and chronic diseases. 3

Food assistance programmes such as the Women, Infants and Children programme and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) help address barriers to accessing healthy food and may reduce food insecurity. 4 5 Interventions implemented within healthcare settings—such as onsite food pantries and mobile food distributions—that serve food-insecure populations have also been effective. 3

Our hospital is a large, urban safety-net hospital in metro Atlanta that provides care to low income and other vulnerable populations. In 2015, an assessment of food insecurity was conducted in the hospital’s primary care centre, where 323 patients completed a questionnaire that included questions regarding age, sex, race, household income, number of people in the household, zip code, diabetes status, the USDA two-item food security screener and SNAP utilisation. The study revealed that 55% of low-income patients receiving outpatient care were food-insecure. 6 To address this issue, we implemented a free 6-month Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Program (FVRx) within a primary care clinic at the hospital in 2016.

Eligible participants had a Body Mass Index (BMI)>30 and at least one associated chronic condition, such as diabetes. Components of the FVRx programme included 4 weeks of fruit and vegetable prescriptions to be redeemed for fresh fruits and vegetables packaged locally, monthly interactive groups classes on nutrition, and monthly cooking classes providing evidence-based nutrition and cooking skills education.

On completion of the programme, we conducted a postintervention qualitative evaluation among participants of the FVRx programme to assess (1) constraints on programme participation, (2) barriers to maintaining a healthy diet among participants, (3) participant capacity to sustain behaviour change during and after completion of the programme, in an effort to identify strategies that could improve participant retention and satisfaction with future programmes. This paper describes the results of this evaluation.

This evaluation incorporated a qualitative research study design. A telephone interview script was used to ask questions about patients’ experience with the FVRx programme, grocery shopping habits and the patient’s current fruit and vegetable consumption (see online supplementary appendix A ). Interview questions were developed to address the main goals of the evaluation, which were to investigate constraints on programme participation, barriers to maintaining a healthy diet among participants postintervention and strategies to improve participant retention.

Supplemental material

Enrolment of the 32 patients into the FVRx study occurred in June 2016; participation in the FVRx programme by the 32 participants took place from July 2016 to December 2016. Participants were referred to the programme by their primary care provider if they had a BMI>30 and at least one diet-related illness. All 32 participants had access to a phone rather their own or a family member’s phone.

The first author contacted the original 32 patients who participated in the FVRx programme by phone in June 2017, approximately 6 months after completing the programme. Six of 32 participants did not answer but had a working voicemail, for which a maximum of two messages were left. Additionally, the team encountered the wrong number for three participants, and full mailboxes for two numbers. Two numbers went unanswered (no voicemail) and one number was disconnected. Thus, of the 32 participants, 18 were reached by phone and verbally consented to participate in follow-up evaluation. Seven participants completed the programme while 11 participants attended a few classes but dropped out. None of the FVRx participants contacted refused to be interviewed.

Interviews were recorded using the TapeACall app and transcribed verbatim. Four interviews were not recorded due to technical difficulties with the app. In these instances, detailed notes were taken and were used in analyses in lieu of verbatim transcripts. A codebook was developed consisting of deductive and inductive codes. Deductive codes were developed based on the key topics addressed in the interviews; inductive codes were identified from analytically reading the transcripts. Transcripts were uploaded to and coded in MAXQDA V.12 (Release 12.3.2). Constant comparative analysis was used to compare experiences and perspectives between those who graduated and those who dropped out. This comparison was undertaken to understand how capabilities, motivations and opportunities changed over the course of their participation, and how this ultimately influenced programme retention.

Participant data on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics were collected at baseline ( table 1 ).

- View inline

Demographics of the FVRx participants*

Overall participant perspectives of the program

When asked about their main motivation for enrolling in the programme, most participants reported the desire to eat healthier and the desire to lose weight. ‘Motivation to enrol’ was one of the codes used in MAXQDA for the analysis, with subcodes of lose weight, eat healthy or doctor recommended. Of the 18 people interviewed, 8 or 44% mentioned enrolling in the programme to lose weight, and 11 or 61% mentioned enrolling to learn to eat healthy. When asked about the most useful thing they learnt in the programme, nearly all the respondents mentioned an improvement in their knowledge of nutrition, such as learning correct portion sizes or reading nutrition labels. Other participants reported enjoying meeting new people and having a sense of camaraderie and support from the group. Additionally, over half of the participants, including those who did not finish the classes, said they would like to enrol in the programme again if given the opportunity.

Participant capacity to sustain behaviour change

When asked about fruit and vegetable consumption since the programme ended, most respondents reported they continue to eat a good amount of fruits and vegetables ( Excerpts: ‘I’m beginning to start to like broccoli and been doing some kale’ and ‘Yes, I do a lot of salads and fruits…I am loving the fresh fruits’). The majority of participants reported that they continue to use the lessons they learnt in the healthy living and cooking classes when making food choices.

Of the 18, 15 or 83% respondents mentioned nutrition knowledge as a positive takeaway from the programme, and 15 of the 18 or 83% respondents also mentioned continuing to consume fruits and vegetables.

Constraints on program participation

Two participants mentioned that even though they were getting free food with the vouchers, it was still expensive ( Excerpt: ‘I had to pay a co-pay each time, and it just got too expensive…’). Others reported challenges in having transportation to attend the Healthy Living Classes ( Excerpt: ‘I wasn’t able at that time to have the transportation to go to all of them’). Another participant with mobility limitations had difficulty picking up their packaged fresh produce. Those who did not graduate cited their own or a family member’s poor health; out of pocket costs (ie, copays); lack of affordable transportation or parking; and/or inconvenient scheduling of the sessions. ‘Dropout/Missed Sessions Reasons’ code had a subcode of transportation/mobility, and four of the 18 or 22% of the respondents mentioned lack of transportation as their reason for not attending classes.

Barriers to maintaining a healthy diet among participants

When asked what they believe the biggest barrier to healthy eating is, the most commonly reported answer was cost (n=6) ( Excerpt: ‘…for people like me, that have so many medical bills…it’s easier to get the cheaper, unhealthy things…’). Another participant explained that her family often gets groceries from the food pantry, where the healthy options such as fresh produce are limited. Another reported barrier was finding the time to cook healthy meals, especially when working or caring for children. Over half of the respondents mentioned shopping at multiple stores in order to obtain the lowest prices ( Excerpt: ‘I shop at the cheapest store I can get it (fruits and vegetables) at’).

This evaluation reveals that most participants of the FVRx programme reported improved knowledge of nutrition and continue to consume fresh fruits and vegetables months after completion of the programme. However, FVRx participants continue to encounter barriers to maintaining a healthy diet with the most commonly reported barriers being the cost of fresh produce and competing priorities such as child care which prohibited time dedicated to healthy food preparation.

Lifestyle change interventions have been shown to be effective in the treatment and prevention of diet-related illnesses such as diabetes. 7 Similarly, other research has shown the use of goal setting and small groups to be promising tools in dietary behaviour modification, both of which are used in FVRx. 8 However, lifestyle change initiatives and health education may be ineffective in increasing healthy food consumption if they do not take into consideration other factors such as neighbourhood segregation, market strategies and poverty as important modifiers of accessibility. 9 In order to address the food insecurity in these low-income patients, we have to find ways to tackle the cost barriers they face when it comes to accessing healthier foods. Our FVRx programme attempts to integrate both health education and monetary incentives through vouchers, enabling improvement in participant knowledge of healthy eating and addressing any socioeconomic barriers to eating fresh fruits and vegetables during the intervention.

Without access to free fruits and vegetables through vouchers, consumption of fruits and vegetables continued to be met with challenges such as their cost and competing priorities that precluded time for healthy food preparation. This highlights the importance of incorporating strategies that equip participants with the knowledge and self-efficacy to continue healthy behaviours, even after the programme has ended. While the healthy living curriculum and cooking classes work to provide participants with those tools, conducting follow-up with participants at various intervals, via phone calls or hosting alumni events to serve as booster sessions, could be useful strategies to increase likelihood of continued behaviour.

There are a few limitations to this study. One limitation is that qualitative data were collected from a small sample of participants of the programme. However, this study was intended to be an evaluation of a pilot programme, and results will be used to inform expansion of the FVRx programme within our hospital.

Given the poverty status of many of our patients (figure 1), it is expected that many would have transient housing, possibly leading to the wrong number for three participants, and a disconnected telephone numbers for one another participant. Such social determinants might have also affected the ability to afford transportation to and from classes, as well as copays for the classes. We suspect these factors contributed to the high dropout rate (n=11) and the 44% non-response rate when calling patients 6 months postcompletion of the programme. This is potentially supported by our findings among the six respondents who mentioned cost as the biggest barrier; five of those were individuals who did not finish the programme. The interviews show that nearly all 18 of the respondents had the same motivation for starting the programme: to learn to eat better; however for those that did not ‘graduate’ (n=11), they reported current life circumstances as preventing them from completing the programme. This included health issues (their own or that of a family member), scheduling or difficulty with transportation to the programme site were reported by respondents as reasons for dropping out. These types of variables are not able to be addressed through the FVRx programming in the pilot phase of the programme, but should be researched and addressed in larger studies moving forward

Our multifaceted FVRx pilot programme enhanced participants’ nutritional knowledge and skills and continued consumption of fresh produce months after completion of the programme. However, socioeconomic factors remain as continual barriers to sustaining healthy eating. Additional efforts may be necessary to promote sustained healthy eating, such as skill building around gardening and growing fresh produce in the home. Using these types of innovative approaches may empower lower income populations to overcome barriers to healthy behaviour change. Efforts to improve participant retention in the programme, expand the programme to more participants and promote sustained behaviour change on programme completion are underway.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Wholesome Wave Georgia, Project Open Hand, and The Common Market for their contributions to the FVRx program at our site. We are appreciative to Grady Memorial Hospital and the Primary Care Center for their innovative role in implementing systems change by supporting patient-centred group classes and FVRx prescriptions at our site.

- Coleman-Jensen A ,

- Rabbitt MP ,

- Gregory CA , et al

- Rabbitt M ,

- Laraia BA ,

- Oddo VM , et al

- Kreider B ,

- Pepper JV ,

- Ratcliffe C ,

- McKernan S-M ,

- Knowler WC ,

- Barrett-Connor E ,

- Fowler SE , et al

- Ammerman AS ,

- Lindquist CH ,

- Lohr KN , et al

- Azétsop J ,

Contributors All authors listed have contributed sufficiently to the project to be included as authors, and all those who are qualified to be authors are listed in the author byline. Authors’ contributions: EC conducted the study and the analysis for the study, and helped to write up the study. SRS (MD) gave idea for study and helped plan and conduct the study and helped write up the study. TLH (MD, MPH, MS, FACP) helped plan, developed and conducted the study along with helping write up the study. SB helped plan, developed and conducted the study along with helping to write up the study. GK (MD) helped plan the study and write up the study. JB-J (MD, FACP) helped plan and developed the study. AWG (PhD) supervised and assisted EC in conducting the study and analysing the study and helped to write up the study.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval All study protocols, informed consent documents and tools were reviewed and approved by the hospital review board and deemed exempt from review by Emory University Institutional Review Board. All participants gave verbal informed consent to participate and provided permission to record the call.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 18 January 2022

Large-scale diet tracking data reveal disparate associations between food environment and diet

- Tim Althoff ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4793-2289 1 ,

- Hamed Nilforoshan 2 ,

- Jenna Hua 3 , 4 &

- Jure Leskovec ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5411-923X 2 , 5

Nature Communications volume 13 , Article number: 267 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

31 Citations

114 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Risk factors

An unhealthy diet is a major risk factor for chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 . Limited access to healthy food options may contribute to unhealthy diets 5 , 6 . Studying diets is challenging, typically restricted to small sample sizes, single locations, and non-uniform design across studies, and has led to mixed results on the impact of the food environment 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 . Here we leverage smartphones to track diet health, operationalized through the self-reported consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, fast food and soda, as well as body-mass index status in a country-wide observational study of 1,164,926 U.S. participants (MyFitnessPal app users) and 2.3 billion food entries to study the independent contributions of fast food and grocery store access, income and education to diet health outcomes. This study constitutes the largest nationwide study examining the relationship between the food environment and diet to date. We find that higher access to grocery stores, lower access to fast food, higher income and college education are independently associated with higher consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables, lower consumption of fast food and soda, and lower likelihood of being affected by overweight and obesity. However, these associations vary significantly across zip codes with predominantly Black, Hispanic or white populations. For instance, high grocery store access has a significantly larger association with higher fruit and vegetable consumption in zip codes with predominantly Hispanic populations (7.4% difference) and Black populations (10.2% difference) in contrast to zip codes with predominantly white populations (1.7% difference). Policy targeted at improving food access, income and education may increase healthy eating, but intervention allocation may need to be optimized for specific subpopulations and locations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Population mobility data provides meaningful indicators of fast food intake and diet-related diseases in diverse populations

Integrating human activity into food environments can better predict cardiometabolic diseases in the United States

Assessing household lifestyle exposures from consumer purchases, the My Purchases cohort

Introduction.

Dietary factors significantly contribute to risk of mortality and chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes and cancer globally 1 , 2 , 3 . Emerging evidence suggests that the built and food environment, behavioral, and socioeconomic factors significantly affect diet 7 . Prior studies of the food environment and diet have led to mixed results 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , and very few used nationally representative samples. These mixed results are potentially attributed to methodological limitations of small sample size, differences in geographic contexts, study population, and non-uniform measurements of both the food environment and diet across studies. Therefore, research with larger sample size and using improved and consistent methods and measurements is needed 9 , 24 , 25 .

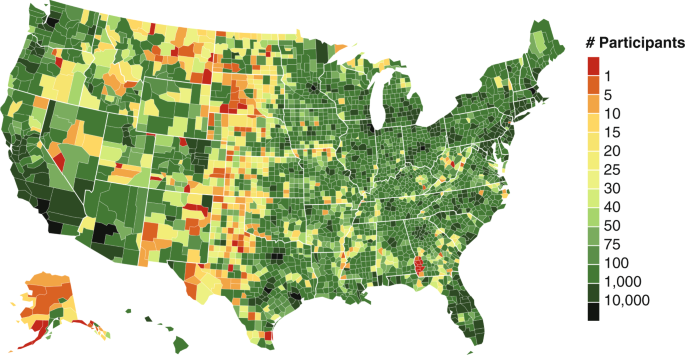

Commercially available and widely used mobile applications allow the tracking of health behaviors and population health 26 , as recently demonstrated in physical activity 27 , 28 , sleep 29 , 30 , COVID-19 pandemic response 31 , 32 , 33 , women’s health 34 , as well as diet research 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 . With ever increasing smartphone ownership in the U.S. 41 and the availability of immense geospatial data, there are now unprecedented opportunities to combine various data on individual diets, population characteristics (gender and ethnicity), socioeconomic status (income and educational attainment), as well as food environment at large scale. Interrogation of these rich data resources to examine geographical and other forms of heterogeneity in the effect of food environments on health could lead to the development and implementation of cost-effective interventions 42 . Here, we leverage large-scale smartphone-based food journals of 1,164,926 participants across 9822 U.S. zip codes (Fig. 1 ) and combine several Internet data sources to quantify the independent associations of food (grocery and fast food) access, income and educational attainment with food consumption and body-mass index (BMI) status (Fig. 2 ). This study constitutes the largest nationwide study examining the relationship between the food environment and diet to date.

A choropleth showing the number of participants in each U.S. county. This country-wide observational study included 1,164,926 participants across 9822 U.S. zip codes that collectively logged 2.3 billion food entries for an average of 197 days each. This study constitutes the largest nationwide study examining the relationship between food environment and diet to date (e.g., with 511% more counties represented compared to BRFSS data 93 ).

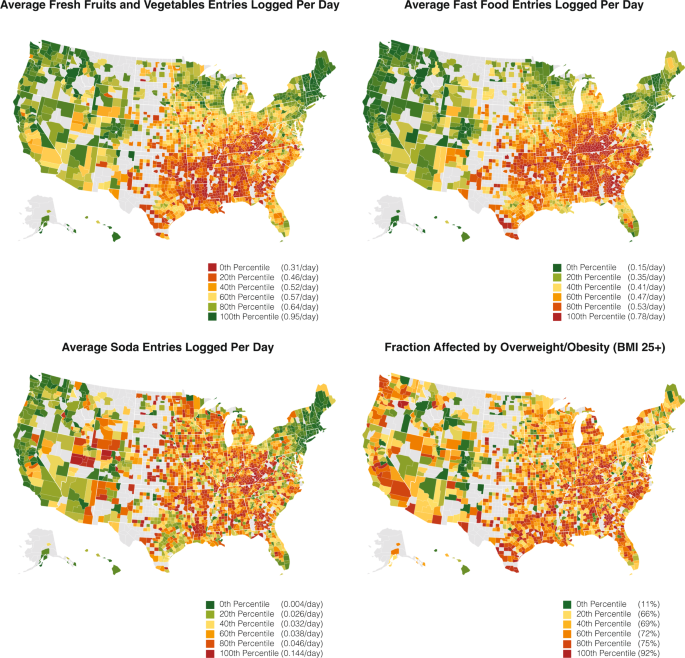

A set of choropleths showing the main study outcomes of the number of entries that are classified as fresh fruit and vegetables, fast food, and soda consumption as well as the fraction affected by overweight/obesity (BMI > 25) participants across the USA by counties with more than 30 participants. We observe that food consumption healthfulness varies significantly across counties in the United States.

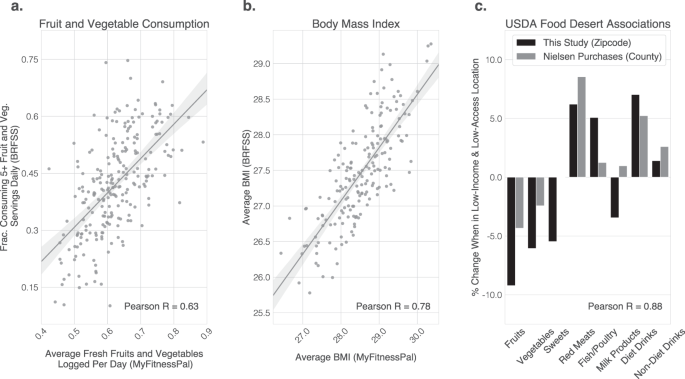

Data validation: diet tracking data correlates with existing large-scale measures

To determine the ability of our dataset to identify relationships between fast food, grocery store access, income, educational attainment and diet health outcomes, we confirmed that this studies’ smartphone-based food logs correlate with existing large-scale survey measures and purchase data. Specifically, the fraction of fresh fruits and vegetables (F&V) that participants logged is correlated with Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey data 43 (Fig. 3 a; Pearson Correlation R = 0.63, p < 10 −5 ; Two-sided Student’s t -test; Methods). Further, the reported BMI of MyFitnessPal (MFP) participants is correlated with BRFSS survey data 44 (Fig. 3 b; Pearson Correlation R = 0.78, p < 10 −5 ; Two-sided Student’s t -test; Methods). Lastly, the digital food logs data replicate previous findings of relative consumption differences in low-income, low-access food deserts based on Nielsen purchase data 45 (Fig. 3 c; Pearson Correlation R = 0.88, p < 0.01; Two-sided Student’s t -test; Methods). These results demonstrate that smartphone-based food logs are highly correlated with existing, gold-standard survey measures and purchase data.

a Fraction of fresh fruits and vegetables logged is correlated with BRFSS survey data 43 (Pearson Correlation R = 0.63, p < 10 −5 ; Two-sided Student’s t -test; Methods). b Body-mass index of smartphone cohort is correlated with BRFSS survey data 44 (Pearson Correlation R = 0.78, p < 10 −5 ; Two-sided Student’s t -test; Methods). Lines in a , b show best linear fit along with shaded 95% bootstrap confidence intervals. c Digital food logs replicate previous findings of relative consumption differences in low-income, low-access food deserts based on Nielsen purchase data 45 (Pearson Correlation R = 0.88, p < 0.01; Two-sided Student’s t -test; Methods). These results demonstrate that smartphone-based food logs are highly correlated with existing, gold-standard survey measures and purchase data.

Associations between food environment, demographics and diet

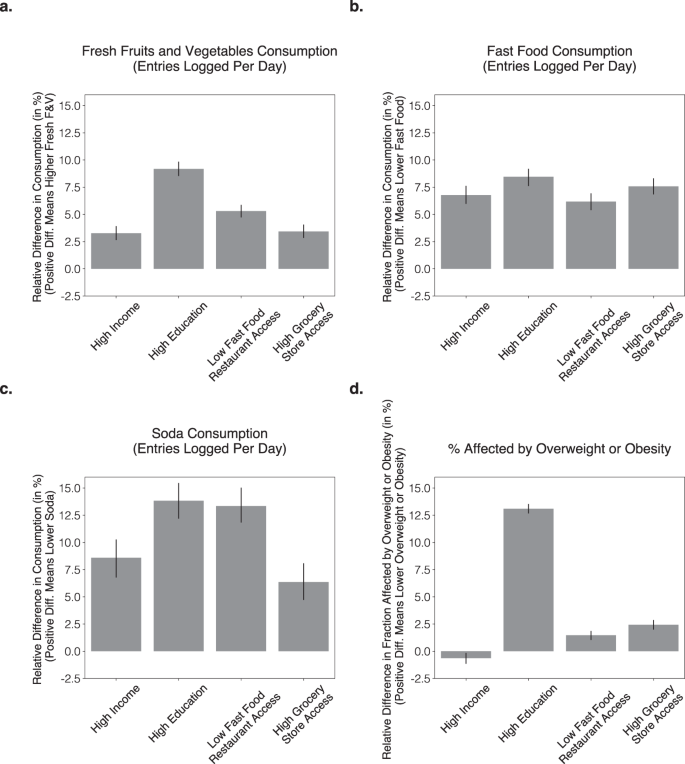

Using these data across all 9822 U.S. codes, we found that high income, high educational attainment, high grocery store access, and low fast food access were independently associated with higher consumption of fresh F&V, lower consumption of fast food and soda, and lower prevalence of BMI levels categorized as overweight or obesity (Fig. 4 ; BMI > 25). The only exception to this pattern was a very slight (0.6%) positive difference in BMI levels categorized as overweight or obesity associated with income. Specifically, in zip codes of above median grocery store access participants logged 3.4% more F&V, 7.6% less fast food, 6.4% less soda and were 2.4% less likely to be affected by overweight or obesity (all P < 0.001). In zip codes of below median fast food access participants logged 5.3% more F&V, 6.2% less fast food, 13.3% less soda and were 1.5% less likely to be affected by overweight or obesity (all P < 0.001). In zip codes of above median education, participants logged 9.2% more F&V, 8.5% less fast food, 13.8% less soda and were 13.1% less likely to be affected by overweight or obesity (all P < 0.001). Finally, in zip codes of above median household income (referred to as higher income below), participants logged 3.3% more F&V, 6.8% less fast food, 8.6% less soda (all P < 0.001), but had a 0.6% higher likelihood of being affected by overweight or obesity ( P = 0.006). Note that the reported effect size are based on comparing above and below median zip codes for any given factor. We found a general pattern of consistent, and in many cases higher effect sizes when comparing top versus bottom quartiles (Supplementary Fig. 2 ), suggesting the possibility of a dose-response relationships across most considered variables. We found that zip codes with high educational attainment levels compared to low educational attainment levels had the largest relative positive differences across F&V, fast food, soda, and BMI levels categorized as overweight or obesity.

Independent contributions of high income (median family income higher than or equal to $70,241), high educational attainment (fraction of population with college education 29.8% or higher), high grocery store access (fraction of population that is closer than 0.5 miles from nearest grocery store is greater than or equal to than 20.3%), and low fast food access (less than or equal to 5.0% of all businesses are fast-food chains) on relative difference in consumption of a fresh fruits and vegetables, b fast food, c soda, and d relative difference in fraction affected by overweight or obesity (BMI > 25). Cut points correspond to median values. Y -axes are oriented such that consistently higher is better. Estimates are based on matching experiments controlling for all but one treatment variable, across N = 4911 matched pairs of zip codes (Methods). Bar height corresponds to mean values; error bars correspond to 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (Methods). While the most highly predictive factors vary across outcomes, only high educational attainment was associated with a sizeable difference of 13.1% in the fraction affected by overweight or obesity.

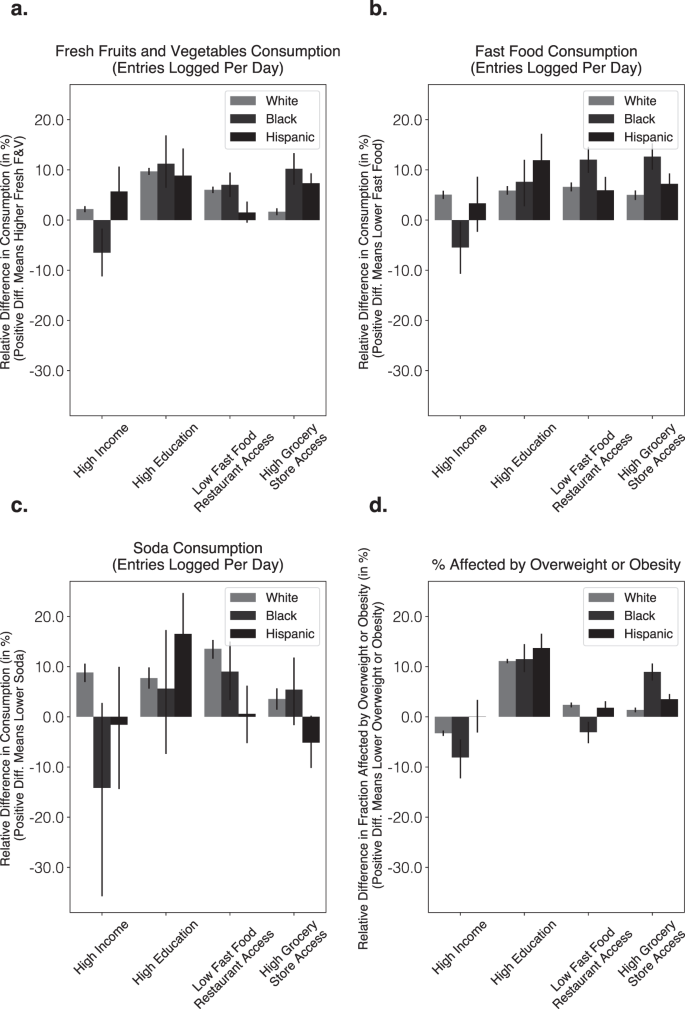

Significant differences across zip codes with predominantly Black, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic white populations