- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Personality and health.

- Sarah E. Hampson Sarah E. Hampson Department of Psychology and Health, Oregon Research Institute

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.121

- Published online: 19 December 2017

Although the belief that personality is linked to health goes back at least to Greek and Roman times, the scientific study of these links began in earnest only during the last century. The field of psychosomatic medicine, which grew out of psychoanalysis, accepted that the body and the mind were closely connected. By the end of the 20th century, the widespread adoption of the five-factor model of personality and the availability of reliable and valid measures of personality traits transformed the study of personality and health. Of the five broad domains of personality (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and intellect/openness), the most consistent findings in relation to health have been obtained for conscientiousness (i.e., hard-working, reliable, self-controlled). People who are more conscientious have better health and live longer lives than those who are less conscientious. These advantages are partly explained by the better health behaviors, good social relationships, and less stress that tend to characterize those who are more conscientious. The causal relation between personality and health may run in both directions; that is, personality influences health, and health influences personality. In addition to disease diagnoses and longevity, changes on biomarkers such as inflammation, cortisol activity, and cellular aging are increasingly used to chart health in relation to personality traits and to test explanatory models. Recognizing that both personality and health change over the life course has promoted longitudinal studies and a life-span approach to the study of personality and health.

- personality

- conscientiousness

- health behaviors

Introduction

Does the kind of person we are affect whether or not we will succumb to disease? This question has been posed since Greek and Roman times, but it only began to attract serious scientific inquiry in the latter half of the 20th century . With the widespread adoption of the Big Five approach to personality-trait measurement, the pace of personality–health research quickened, and its remit was greatly expanded. Although personality is only one of the myriad factors that impact health, it is a central element in the psychology of health because personality influences many of those other factors. The variation in people’s educational attainment and socioeconomic position, their response to stress, their social connectedness, and their diligence in following health recommendations can all be attributed, in part, to personality.

Personality–health research establishes associations between personality traits and health outcomes, and examines the mechanisms to account for these associations. The results of personality–health research have the potential to improve human health and well-being. With greater understanding of the pathways between individual characteristics and health comes the opportunity to redirect those pathways. This knowledge can be used by us all to help keep on a more healthful course. It can be used by healthcare professionals to improve the tailoring of care to the individual. The results of personality–health research may even be used to guide interventions to support the development of health-enhancing personality characteristics.

In the study of personality and health, trait approaches have become pre-eminent. Personality traits are generally defined as a person’s characteristic thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Funder, 2001 ). The widespread acceptance of the five-factor or Big Five approach to trait theory has been a boon for personality–health research. In this approach, personality traits are comprehensively organized in terms of five broad and relatively independent domains that include both positive and negative characteristics related to extraversion (sociable, energetic, withdrawn), agreeableness (helpful, cooperative, hostile), conscientiousness (hard-working, self-controlled, disorganized), emotional stability (calm, anxious, worrying), and openness to experience (curious, imaginative, unintelligent). By the early 21st century , there were reliable and valid measures of these broad domains and of the narrower groups of traits, known as facets, making up these domains (John, Naumann, & Soto, 2008 ; McCrae & Costa, 2008 ). With a common metric for personality measurement, personality–health research has become a cumulative, incremental science that is building a solid body of evidence.

In personality–health research, health outcomes include self-reports of general health and specific diseases, doctors’ reports of diagnosed conditions, clinically assessed biomarkers that are known risk factors for morbidity and mortality, and mortality itself. Self-reports of health are easy and inexpensive to collect, but they may be biased. This can be problematic for personality–health research; for example, people who are more neurotic (i.e., less emotionally stable in Big Five terms) tend to perceive themselves to be in poorer health (Chapman, Duberstein, Sörensen, Lyness, & Emery, 2006 ). In defense of self-reports, self-rated general health, measured by a single item (“Compared to others of your age and gender, would you say that in general your health is poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent?”) is a reliable predictor of risk of dying (DeSalvo, Bloser, Reynolds, He, & Muntner, 2006 ). Patients’ reports of diagnosed diseases tend to correlate moderately well with doctors’ diagnoses (Barr, Tonkin, Welborn, & Shaw, 2009 ). Objective outcomes, such as assay values and anthropometric measures, though free of subjective biases, can also suffer from unreliability, the “white coat” effect on blood pressure being a familiar example.

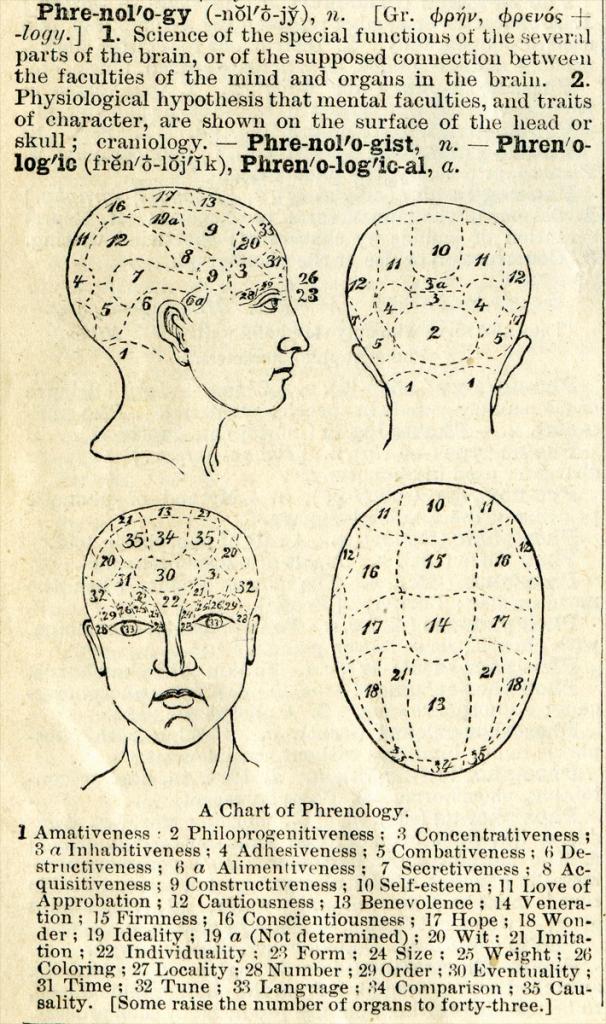

The Origins of Modern Personality and Health Research

Hippocrates (ca. 460–ca. 370 bc ) is known as the Father of Western medicine, but he was also a pioneer of personality and health because he recognized that the body and psyche are connected. His practice of medicine was based on the theory of the four body humors (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm), which were associated with four temperament types (sanguine, choleric, melancholic, phlegmatic). His was a biological model of personality and health; these bodily humors, which could be traced to different organs, were associated with temperament and disease. Although modern medicine has abandoned the four humors, the four temperaments resonate with modern personality-trait theory. For example, sanguine individuals are extraverted and emotionally stable, whereas melancholic individuals are introverted and neurotic. Western thought came to be dominated by Descartes’s mind-body dualism, but by the early 20th century , the link between the psyche and the soma was proving fascinating to psychoanalysts, particularly Sigmund Freud, who believed that mental illness could manifest itself in physical symptoms (Freud, 1955 ). The field of psychosomatic medicine developed from these traditions and formalized the idea that diseases can result from psychological problems.

Against this historical background, it was perhaps inevitable that late 20th century research focused on relating particular personality traits to specific diseases. The most prominent example of this work was on the association between the Type A and cardiovascular disease (M. Friedman & Rosenman, 1974 ). Type A individuals are characterized by behavior that is hostile and competitive, and they experience irritation and frustration because of a sense of time urgency (M. Friedman, 1996 ). Hippocrates would have called them choleric. Initially, studies appeared to demonstrate that Type A people were more likely to experience cardiovascular disease, but failures to replicate those finding and studies that included important control variables, such as diet, began to question the association (Houston & Snyder, 1988 ).

Instead of associating a particular type of person with a specific disease, H. S. Friedman and Booth-Kewley ( 1987 ) conducted a meta-analysis to see if the same traits in fact were associated with several diseases. They concluded that there may be a disease-prone personality, characterized by anxiety, hostility, and depression, a conclusion that has been confirmed by others (Suls & Bunde, 2005 ). With the Type A pattern reduced to its most active ingredient, hostility, Type A is no longer widely used as a measure of personality in personality–health research. But that body of work left behind the important legacy that certain personality traits are associated with diseases, if not in the one-to-one manner previously supposed.

The 1990s marked a turning point for the study of personality and health with the publication of findings on childhood personality predicting longevity using data from the Terman Life-Cycle study. The study began in 1921 with the goal of following a group of exceptionally gifted 11-year-olds to adulthood to see how their lives turned out (Terman & Oden, 1947 ). The sample was studied every 5 to 10 years, creating a uniquely valuable archive that included childhood personality and mortality data. H. S. Friedman and his colleagues used these data to test the hypothesis that childhood personality is associated with longevity. If supported, this would strongly indicate that personality influences health across the lifespan. Their first report caused quite a stir (H. S. Friedman et al., 1993 ). Children who were viewed as more conscientious by their teachers and parents lived longer than those who were less conscientious. They also observed that children who were more cheerful (optimistic, humorous) were at a slightly higher risk for mortality than those who were less cheerful, and that being emotionally stable may have been protective against mortality for men. The largest effect they observed was for conscientiousness. Having low childhood conscientiousness was equivalent to the mortality risk of having high blood pressure or high cholesterol (H. S. Friedman, Tucker, Schwartz, Tomlinson-Keasy et al., 1995 ). Naturally, the next question to investigate was why conscientiousness was related to longevity. The Terman archives included data on cause of death and on some health behaviors. However, the association was not fully accounted for by low-conscientious children dying from accidents and violence or by their histories of drinking alcohol, smoking, and obesity, which left many unanswered questions for the next era of personality–health research (H. S. Friedman, Tucker, Schwartz, Martin et al., 1995 ).

Twenty-First-Century Personality and Health Research

While H. S. Friedman and colleague’s findings provided the impetus for contemporary personality–health research, the emergence of the Big Five provided the necessary tools for describing and measuring personality. Now that a legitimate link between at least one of the Big Five traits and a hard health outcome (mortality) had been established, personality–health researchers began to take a closer look at all of the Big Five in relation to other health outcomes. They did so in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, and they began to examine possible underlying mechanisms to explain these associations.

The large-scale study by Goodwin and Friedman ( 2006 ) illustrates the value of cross-sectional research. The authors related scores on the Big Five personality dimensions to self-reported mental and physical health and physical limitations in a representative sample of over 3,000 community-dwelling men and women participating in the Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) study. They found that that the Big Five traits of conscientiousness and emotional stability (vs. neuroticism) were consistently and strongly related to better health; whereas the associations for extraversion, agreeableness, and openness were less clear-cut. A limitation of this study was the reliance on self-reported health, which may have inflated the association between neuroticism and reporting mental and physical illness. The consistent findings for conscientiousness in this representative sample provided further support that this trait protects against poor health. The findings suggested that more-conscientious people were less likely to get sick and that for this reason, they were more likely to live longer lives. Yet, without longitudinal studies, even a tentative inference that conscientiousness is somehow causally related to better health could not be justified. Better health could cause higher levels of conscientiousness; or, both good health and conscientiousness could be spuriously associated because of a third underlying variable causing them both. Fortunately, several longitudinal studies that included personality and health data had been underway over a long enough period to permit researchers to ask whether personality traits measured years or even decades earlier were associated with subsequent health outcomes.

Longitudinal Personality–Health Research

Personality and mortality.

The association between childhood conscientiousness and longevity observed in the Terman Life-Cycle study spurred researchers to examine this association in other samples. The Terman participants were selected because of their high IQs. Would the association be observed in samples taken from the general population, and would it be observed when conscientiousness was assessed at an older age than childhood? A meta-analysis combining findings from 20 different samples including nearly 9,000 people, primarily adults but some adolescents as well, established an overall correlation of r = .11 between conscientiousness and mortality (Kern & Friedman, 2008 ). To provide some context for this correlation, it is of the same magnitude as the association between antihistamine use and reduced runny nose, and combat exposure and subsequent PTSD within 18 years (Meyer et al., 2001 ). Even more impressive was the conclusion drawn from a later meta-analysis of over 76,000 individuals, from seven different cohort studies, with a mean age of 51 years at the time of personality measurement. This meta-analysis compared the associations for all the Big Five and mortality and concluded that conscientiousness was the only Big Five trait to predict all-cause mortality (Jokela et al., 2013 ). Those in the lowest tertile for conscientiousness had a 34% increased risk of dying.

The case for conscientiousness and longevity was compelling, but what about the other Big Five traits? There is evidence that people who are higher on neuroticism (i.e., those who are low on emotional stability) are at greater risk of dying (Grossardt, Bower, Geda, Colligan, & Rocca, 2009 ; Wilson, Mendes de Leon, Bienias, Evans, & Bennett, 2004 ). In one study, older men with high and increasing levels of neuroticism over time were at higher risk of death (Mroczek & Spiro, 2007 ). However, neuroticism was not associated with mortality at eight years follow-up in a study of Medicare recipients (Costa, Weiss, Duberstein, Friedman, & Siegler, 2014 ). For some, neuroticism may be associated with better health because of greater vigilance to environmental and bodily cues related to health. As a consequence, neuroticism may actually be advantageous for health for some people (H. S. Friedman, 2000 ). Some studies have found that people higher on openness to experience have a lower mortality risk (Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007 ; Turiano, Spiro, & Mroczek, 2012 ), and a meta-analysis indicated that there is a modest protective effect of openness even when controlling for standard mortality risk factors (Ferguson & Bibby, 2012 ). There is less evidence for extraversion and agreeableness. Extraverts may be at higher risk for mortality (Ploubidis & Grundy, 2009 ); whereas those with higher levels of agreeableness may enjoy protection from mortality risk (Costa et al., 2014 ). In sum, all of the Big Five have been associated with mortality, but the evidence is stronger and more consistent for conscientiousness than for the other traits.

Personality and Morbidity

Returning to a question asked by Hippocrates and Galen, personality researchers have used the Big Five framework to see whether there are traits that are predictive of the onset of particular diseases, and disease-specific mortality. To answer this question, meta-analyses have again proved helpful. In a meta-analysis of studies including nearly 35,000 participants who were diabetes-free at baseline, low conscientiousness was the only Big Five trait associated with risk of diabetes onset and diabetes mortality over the subsequent 5.7 years (Jokela, Elvainio et al., 2014 ). A meta-analysis of three cohort studies involving over 24,000 older participants examined death from coronary heart disease or stroke after 3–15 years (Jokela, Pulkki-Råback, Elovainio, & Kivimäki, 2014 ). Higher conscientiousness was protective against death from either heart disease or stroke, whereas higher extraversion increased the risk of stroke but not heart disease, and higher neuroticism was more strongly related to heart disease than stroke. Despite a common belief that personality is related to cancer, a meta-analysis of over 42,000 initially cancer-free individuals failed to relate any of the Big Five to increased risk of cancer or death by cancer after 5.4 years follow-up (Jokela, Batty et al., 2014 ).

Diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer are leading causes of mortality in developed countries. Lack of conscientiousness may be implicated in the onset of all but cancer. The evidence for the involvement of the other Big Five is either less clear or nonexistent. These studies have used diagnosed disease, typically self-reported, as their end point. However, chronic diseases can take years to develop, and the risk of their onset is signaled by deterioration over time on measures, known as biomarkers, such as blood pressure, lipid profiles, and body mass index. Finding associations between personality traits and disease onset provided good justification to look for associations between traits and biomarkers of disease risk.

Personality and Biomarkers

A cross-sectional study of personality and health in a community-based sample of over 5,000 Sardinians has yielded some provocative findings. Participants who were lower on conscientiousness had less healthy lipid profiles (Sutin, Terraciano et al., 2010 ), and were more likely to display an unhealthy pattern of nighttime blood pressure changes (Terracciano et al., 2014 ). They also had higher levels of leptin, a hormone involved in appetite, suggesting they might be more resistant to leptin, which could be a mechanism involved in weight gain (Sutin et al., 2013 ). Those lower on conscientiousness were more likely to be obese (Terracciano et al., 2009 ). Also in this same sample, those who were more impulsive had higher white-blood-cell counts, and those who were more neurotic and less conscientious had higher levels of interleuken-6 (Sutin et al., 2012 ). Both of these biomarkers are indicators of inflammation, which has health-damaging effects and is associated with several chronic conditions. The link between low conscientiousness and higher levels of the inflammatory markers of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 was confirmed in a meta-analysis involving several very large studies and many thousands of participants (Luchetti, Barkley, Stephan, Terracciano, & Sutin, 2014 ).

The associations between single biomarkers and personality traits can be quite small, particularly after controlling for covariates such as gender and education, necessitating large sample sizes to demonstrate statistically significant associations that may not be of clinical relevance. An alternative approach is to use a combination of biomarkers as the outcome. This has the advantage of summing across several small effects. It is also consistent with medical practice. For example, endocrinologists use the metabolic syndrome, which is derived from several biomarkers indicating cardiovascular and metabolic dysregulation, to evaluate risk for diabetes and heart disease. In another study using data from the Sardinian sample, Sutin, Costa et al. ( 2010 ) found that high neuroticism and low agreeableness were associated with the metabolic syndrome, whereas high conscientiousness was protective.

Cross-sectional findings such as those for the Sardinian sample are consistent with the interpretation that personality traits could lead to morbidity through deteriorating health, but longitudinal studies provide more compelling evidence for a causal pathway.

The ongoing Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development study is following more than 1,000 people from their births in 1972–1973 in the town of Dunedin, New Zealand, to the present. The study did not include a measure of the Big Five in childhood but several measures of self-control were collected over the children’s first decade of life from parents, teachers, and self-reports. These were combined into a single, internally reliable measure that predicted an objectively assessed physical-health index at age 32. This index was composed of metabolic abnormalities (including overweight), airflow limitation, periodontal disease, sexually transmitted infection, and C-reactive protein level. Lower childhood self-control predicted poorer adult health on this index, even after controlling for social class in childhood and IQ (Moffitt et al., 2011 ).

The Hawaii Longitudinal Study of Personality and Health (Hawaii study) is notable for its detailed childhood personality assessment at age 10 conducted by teachers, from which scores on the Big Five have been derived (Goldberg, 2001 ). Forty years later, at a mean age of 50–51, childhood personality was related to a composite of cardiovascular and metabolic biomarkers of physiological dysregulation (blood pressure, lipid profile, obesity, urine protein, fasting blood glucose, and medication for blood pressure or cholesterol). The only childhood trait to predict dysregulation was conscientiousness. Those who were less conscientious as children were more likely to be more physiologically dysregulated as adults approximately 40 years later, controlling for gender, ethnicity, social class in childhood, and adult levels of conscientiousness (Hampson, Edmonds, Goldberg, Dubanoski, & Hillier, 2013 ).

The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns (CRYF) study is an ongoing investigation of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in a representative sample aged 3 to 18 when first recruited (Raitakari et al., 2008 ). Baseline measures of psychosocial risk factors (parents’ ratings of their child’s self-regulation, the socioeconomic environment, and stressful life events) were summed and used to predict a composite measure of cardiovascular health assessed by self-report and clinical measures 27 years later (Pulkki-Råback et al., 2015 ). Lower overall psychosocial risk predicted better cardiovascular health in a dose-response pattern, and the measure of children’s self-regulation alone predicted cardiovascular health.

Together, these three longitudinal studies that differ in location, time period, age of sample, and measures all converge on the same result: measures related to conscientiousness and self-control in childhood were associated prospectively with a composite measure of physical health decades later. These findings strongly suggest that this personality domain exerts a sustained influence on health status across adulthood. Paired with the findings for mortality, a convincing picture emerges of conscientiousness affecting health across the lifespan. Given the weight of evidence for an association, quite possibly causal, it becomes important to investigate plausible explanations for how personality could influence health.

Personality and Health Mechanisms

Three mechanisms to account for personality influences on health have received particular attention: health behaviors, social relationships, and stress. Personality traits may influence whether a person engages in health-enhancing or health-damaging behaviors, has a supportive social environment, is exposed to stress and can manage stress. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and most probably work together to produce biological changes that lead to health outcomes. Personality traits influence many of the factors that are involved in health, which makes studying a particular personality mechanism challenging. For example, when studying health behaviors, it is also necessary to consider that personality influences educational attainment, which affects socioeconomic position, which is strongly related to health. Those with higher educational attainment are likely to be more knowledgeable about health behaviors and to have more time and money to spend on a health-enhancing lifestyle, which will result in better health. Personality most likely affects health through a series of processes involving additional factors in a chain of influences that take place over time (Shanahan et al., 2014 ).

Health-Behavior Mechanisms

Several studies demonstrate that health-behavior mechanisms account for some of the association between personality, particularly conscientiousness, and mortality (e.g., Hagger-Johnson et al., 2012 ; Hill, Turiano, Hurd, Mroczek, & Roberts, 2011 ; Turiano, Chapman, Gruenewald, & Mroczek, 2015 ; Turiano, Hill, Roberts, Spiro, & Mroczek, 2012 ). According to a review by Turiano et al. ( 2015 ), the amount of variance in mortality attributable to conscientiousness that was mediated by health behaviors ranged from 0% to 21% across studies, with a mean of 12%. This suggests that health behaviors provide a partial explanation for the effects of conscientiousness on mortality; but other mechanisms are likely to be involved as well.

The health-behavior model has also been tested with morbidity as the outcome. In a cross-sectional study, Lodi-Smith et al. ( 2010 ) showed that conscientiousness influenced self-reported physical health through education, risky behaviors, and preventive health behaviors. Ideally, the mediation process implied by the health-behavior model should be tested prospectively by assessing personality prior to health behavior, which is assessed prior to the health outcome. Furthermore, measuring health behavior at one time point probably does not adequately capture the long-term health-behavior patterns that are required to produce biological effects on biomarkers, such as high cholesterol. To address this limitation, a cumulative measure of health-damaging behavior across the lifespan was developed in the Hawaii study that combined lifetime smoking, physical inactivity, and BMI summed across decades in adulthood (Hampson, Edmonds, Goldberg, Dubanoski, & Hillier, 2015 ). Childhood conscientiousness was related to objectively assessed health status at age 50–51 through this measure of life-span health-damaging behavior as well as educational attainment and cognitive ability, controlling for any effects of adult conscientiousness. Health-behavior mechanisms appear to underlie the association between both conscientiousness and mortality and conscientiousness and morbidity.

Social-Relationship Mechanisms

Individuals who are more socially integrated tend to have better health and to live longer (Seeman, 1996 , 2000 ). Social integration is typically defined in terms of being married, having children, working, and having other supportive social networks, including belonging to organizations such as churches or volunteer groups. Mechanisms to account for the association between social integration and better health include health behaviors, stress, and physiological effects. Better integrated individuals may be more likely to engage in health-enhancing behaviors and to avoid health-damaging ones. Because of their social relationships, they may be exposed to less stress, and have better social resources to cope with stress. The effects of social integration may also have a direct impact on physiological regulation. Given the importance of social relationships for health, they may be involved in personality–health mechanisms. Personality may influence a person’s degree of social integration, and social integration may serve as an explanatory mechanism for the association between personality and health.

Support for social integration as a personality–health mechanism was demonstrated in a study of marital history and mortality using the Terman Life-Cycle data (Tucker, Friedman, Wingard, & Schwartz, 1996 ). It is well-established that being married is associated with better health outcomes. However, current marital status may be too simplistic. Taking a lifespan perspective, Tucker et al. ( 1996 ) examined marital history, and showed that those who were married but had been divorced were at higher risk of dying than those who were consistently married (i.e., had not experienced a marital breakup). Those who were consistently married had higher childhood conscientiousness than those who were inconsistently married. Childhood conscientiousness accounted for some, but not all, of the difference in mortality between those who were consistently married versus inconsistently married. This pattern of results suggests that the childhood trait of conscientiousness directs individuals on a pathway to health in part through its influence on social relationships, in this case, marriage. A more conscientious individual may make a better spouse, perhaps initially by making a more considered choice of marriage partner and subsequently by being a more reliable and persevering partner.

Given that social integration is important for health, people who are more extraverted may enjoy better health because of their sociability. However, research on extraversion has produced findings both for and against the health benefits of extraverted traits (Hampson & Friedman, 2008 ). In an experimental study, participants with higher levels of sociability (in this case, a combination of extraversion and agreeableness) were less likely to succumb to the common cold when deliberately infected with the virus, controlling for baseline immunity. Those who were more sociable had larger social networks and more social contacts, yet the effects of sociability on disease susceptibility were not mediated by social integration (Cohen, Doyle, Turner, Alper, & Skoner, 2003 ). This study illustrates the complexity of personality–health mechanisms. The researchers could not identify the mediators of sociability in this particular study, and concluded that a common genetic basis for sociability and disease resistance may provide the explanation.

Trauma and Stress Mechanisms

Trauma exposure has been reliably shown to have long-term negative consequences for physical and mental health (Felitti et al., 1998 ; Freyd, Klest, & Allard, 2005 ). Personality may increase the likelihood of experiencing trauma through greater probability of trauma exposure, greater reactivity to trauma, or both. Trauma is a source of stress and thus may have a direct negative impact on the stress-response system, and dysregulation of this system has been linked with a variety of biomarkers of stress and inflammation (Fagundes, Glaser, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2013 ; Schrepf, Markon, & Lutgendorf, 2014 ).

Personality is implicated in stress in several ways (Vollrath, 2001 ). Personality traits may moderate the stress response. For example, higher levels of neuroticism may be associated with greater sensitivity to stressful experiences so that a trauma may result in worse negative health outcomes for a more neurotic person compared to a less neurotic person. Higher levels of resilient traits, such as high conscientiousness, may dampen the stress response. In contrast, lack of self-control and low conscientiousness increase the probability that a person will be exposed to trauma and stress (Galla & Wood, 2015 ; Murphy, Miller, & Wrosch, 2013 ). In the Hawaii study, girls who were seen by their teachers as less agreeable and less conscientious at age 10 were more likely to retrospectively report trauma across three age periods (childhood, adolescence, and adulthood) 40 years later. In support of a personality–health mechanism, girls with lower levels of childhood conscientiousness reported more teen and adult trauma, which resulted in poorer objectively assessed health at age 50–51 (Hampson et al., 2016 ).

Multiple Mechanisms

Research indicates that personality–health mechanisms include health behaviors, social relationships, and trauma. These trait-related experiences have a biological impact that ultimately affects health, including disrupting the stress response and the immune system. The different kinds of mechanisms described here are interrelated and likely operate in combination. For example, personality is responsible, in part, for the stress resulting from a lack of close relationships, and for engaging in unhealthy behaviors, such as alcohol abuse and smoking. Stress and unhealthy behaviors compromise the immune system (Kiecolt-Glaser, Gouin, & Hantsu, 2010 ). Similarly, personality is implicated in experiencing trauma, such as child abuse, and childhood abuse is related to greater immune response to stressors in adulthood (Fagundes et al., 2013 ; Gouin, Glaser, Malarkey, Beversdorf, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2012 ). While no one study can capture the full complexity of personality–health mechanisms, oversimplification can result in misleading conclusions. Studies that address the complexity of these interrelated mechanisms as they unfold over time are needed (Friedman & Kern, 2014 ).

A further complexity that needs to be considered is that while personality may influence health outcomes, it is also likely that health may influence personality. That is, if there is a causal relation between personality and health, it may run in both directions. Most of personality–health research is conducted from the perspective that personality may contribute causally to health outcomes, but there are also studies that have investigated the possibility that health affects personality and that there may be reciprocal effects.

Effects of Health on Personality

The experience of being in poor health is often associated with changes in mood and energy levels, and the changes that accompany illness may be associated with, and perhaps are causally related, to changes in personality. A disease is associated with altered biology, which may also affect the biological bases of personality traits. A diagnosis can lead to a new social identity, referred to by Goffman as the “sick” role (Goffman, 1990 ). When a person becomes a “cancer patient” or a “diabetic,” aspects of her lifestyle inevitably must change, and she is likely to be treated differently by others. As a consequence, she may come to see herself differently and undergo some degree of personality change. In addition, a life-altering illness is a stressful event, and stressful events appear to affect aspects of personality, such as increasing the level of neuroticism (Riese et al., 2014 ).

To demonstrate that a health event preceded a change in personality, the ideal research design would be to measure personality before and after the event. Comparing personality measured after the onset of illness with retrospective reports of personality prior to illness is less satisfactory. Recalling one’s personality at an earlier time is a difficult task, and it may be affected by one’s current health and personality. There have been recent studies that assessed personality pre- and post-illness, but the findings do not provide a consistent picture. In a Finnish study of young adults, the onset of a chronic illness was related to increased neuroticism and increased conscientiousness (Liekas & Salmela-Aro, 2015 ). In contrast, among older participants across three independent, large-scale cohort studies, conscientiousness decreased after the onset of chronic illness (Jokela, Hakulinen, Singh-Manoux, & Kivimäki, 2014 ). Data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, which include multiple assessments of health and personality over time, indicated that personality remained largely unchanged in response to disease onset (Sutin, Zonderman, Ferrucci, & Terracciano, 2013 ). It appears that disease onset may have both negative and positive consequences for personality change. Increases in neuroticism may be the result of health-related anxiety and vigilant disease monitoring, whereas increases in conscientiousness may be the result of improved health behavior that led to changes in self-perception. Among older people, becoming ill may lead to a “dolce vita” effect: enjoy life while you can at the expense of prudence (Marsh, Nagengast, & Morin, 2013 ).

One challenge for these studies is in distinguishing between a personality change associated with a change in health and the normative changes in personality that occur across the life course. Over time, health change may precipitate personality change, which may then influence health, and so on. These kinds of patterns of cross-lagged influences over time are studied in autoregressive models. Latent curve models represent the overall shape of the developmental trajectory of a variable, such as health or personality, over time. Both statistical approaches can be combined to capture the variable’s overall trajectory and its perturbations in autoregressive latent trajectories (Bollen & Curran, 2004 ). Although only a few existing studies in personality and health have the necessary longitudinal data, it is likely that more of this kind of modeling will be used in future studies.

Using Personality to Achieve Health Benefits

The evidence for a link between personality and health is by now quite substantial. The prospective evidence that personality measured years, even decades, earlier predicts health outcomes suggests that personality has a causal influence on health. Further support for personality as a cause of health outcomes comes from intervention studies in which the effects of deliberate changes in personality on health are studied. The logic here is that if personality is causally related to health, then changing personality should change health. There is growing interest in developing such interventions, given the mounting evidence that personality is implicated in health outcomes.

One of the earliest demonstrations that personality change can have beneficial health effects was provided by M. Friedman et al. ( 1984 ), who showed that counseling to increase psychological well-being among Type A patients reduced the risk of reoccurrence of cardiovascular events. This is an example of a top-down approach, where the intervention is designed to change personality and then leads to healthful behavior change. This is the principle behind many psychotherapeutic interventions that address behavioral and mental health issues (Chapman, Hampson, & Clarkin, 2014 ). However, people do not necessarily need external support to make personality changes. Volitional top-down trait change was observed in undergraduates, and an intervention to support volitional trait change was also effective in this population (Hudson & Fraley, 2015 ). An alternative is a bottom-up approach in which the intervention targets behavior change, which then leads to personality change (Magidson, Roberts, Collado-Rodriguez, & Lejuez, 2014 ).

Given the remarkably far-reaching influences of childhood conscientiousness on health, it may seem like a good idea to develop interventions to increase conscientiousness from an early age. Indeed, the experience of preschool and elementary school encourages children to develop self-control. However, a cautionary note must be sounded. There is some evidence that conscientiousness can have detrimental effects on health, so that universally increasing this trait could have unintended consequences. Highly conscientious individuals are verging on obsessional-compulsive, which is related to lower well-being (Carter, Guan, Maples, Williamson, & Miller, 2015 ). In a study of adolescent young women, those higher in conscientiousness were less likely to get into stressful situations, but when they did, they had more unhealthy stress responses than those who were lower in conscientiousness (Murphy et al., 2013 ). Situations that one cannot change through one’s own efforts may be more harmful for conscientious than for unconscientious individuals.

Despite the concerns about personality interventions, a number of researchers have proposed that the evidence for the association between personality and health justifies the wider dissemination of this knowledge to the medical community (Bogg & Roberts, 2013 ; Israel et al., 2014 ). For example, in this era of personalized medicine, a relatively brief personality assessment could provide insights that would be helpful for doctor–patient communication and selecting treatment regimens best suited to the individual.

Future Directions

Several aspects of personality–health research may attract increasing attention in the future. These are related to separate developments in the fields of both personality and health. In personality, there is increasing interest in moving away from studying the influence of broad traits, such as the Big Five, in favor of drilling down to narrower traits, such as the facets of the Big Five. The driver behind this trend is that close analysis can reveal an association between a broad personality domain and a specific health variable that is attributable to a particular facet of the domain. For example, a meta-analysis of the associations between facets of conscientiousness and various health behaviors indicated that physical activity was most strongly associated with the industriousness facet of conscientiousness, whereas absence of self-control was most strongly related to excessive alcohol use (Bogg & Roberts, 2004 ). Such findings have led to a renewed discussion of what is meant by causality in personality-trait-outcome research, and some have concluded that narrower traits or even individual personality test items should be used instead of broad traits (Mõttus, 2016 ).

Whether using broad traits or narrower facets, hypothesized models underlying personality–health associations are likely to become more complex. For example, a model that compares two or more multiple mediating mechanisms, such as health behavior and stress, instead of examining just one, permits inferences about their relative importance in predicting health outcomes. These findings would be useful for prioritizing targets for interventions (e.g., stress reduction vs. health-behavior change). Research has tended to focus on the independent influences of traits, but this is an oversimplification of personality processes. Researchers are now examining the possible influence of particular trait combinations, such as being both conscientious and neurotic, on health and health behavior. Neuroticism is typically associated with poor health, particularly self-reported health, while the reverse is true for conscientiousness. H. S. Friedman ( 2000 ) hypothesized that the combination of being both highly conscientious and neurotic may be associated with better health. These individuals, so-called healthy neurotics, would be attentive to their symptoms, seek medical advice promptly, and dutifully follow recommended preventive and treatment regimens. Although this hypothesis is intuitively appealing, it has yet to receive consistent empirical support (Weston & Jackson, 2015 ). Finally, the recognition that it is misleading to treat personality and health as static variables, when they in fact change across the life course, will likely lead to more studies involving multiple assessments of both personality and health over time (Takahashi, Edmonds, Jackson, & Roberts, 2012 ).

On the health side, the use of objective health indicators (biomarkers) is increasingly favored over reliance on self-reported health or diagnosed disease as health outcomes. Biomarkers have several advantages. They can signal changes that are early risk factors for later chronic diseases that may take years, perhaps decades, to develop. Relating personality traits to these biomarkers provides the possibility of early intervention to change the course of declining health before the onset of clinical disease. The number of relatively low-cost biomarkers available for researchers is expanding. For example, assays for leucocyte telomere length and for mitochondrial DNA (markers of different aspects of cellular aging) are becoming more readily available and less expensive. Biomarkers avoid the possible biases of self-reports but have their own issues that will need to be addressed, such as test-retest reliability.

Finally, with the explosion of research on genetics in the 21st century , it is likely that much will be discovered in the future about shared the genetic influences on personality and physical health. Given that both personality and health are influenced by genetic factors, associations between the two could be the result of shared genetic processes (Figueredo & Rushton, 2009 ). Research on the genetics of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin suggests possible genetic links between personality and chronic illnesses (Delvecchio, Bellani, Altamura, & Brambilla, 2016 ). For example, chronic inflammation is associated with both depression (linked to neuroticism) and coronary artery disease, and may have a common genetic basis involving serotonin (McCaffery et al., 2006 ).

Over the past 25 years, the field of personality and health has moved from the margins to the mainstream. The evidence that personality traits are associated with health behaviors and health outcomes is overwhelming, and research is now focusing on explaining these associations. The field has only just begun to consider the implications of these advances for improving health at the individual and population levels. For individuals, it is quite possible to envisage that a visit to the doctor will eventually incorporate a brief personality assessment that will be used to tailor patient-centered self-management of health conditions. From a public health perspective, significant benefits could accrue from a higher mean level of a trait such as conscientiousness by shifting the entire distribution in a more healthful direction, for example, through universal school-based interventions. But until we better understand the possible costs as well as the benefits of using personality traits to improve health outcomes, we should proceed with care.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this contribution was supported by a grant R01AG020048 from the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health.

- Barr, E. L. , Tonkin, A. M. , Welborn, T. A. , & Shaw, J. E. (2009). Validity of self-reported cardiovascular disease events in comparison to medical record adjudication and a statewide hospital morbidity database: The AusDiab study. Internal Medicine Journal , 39 , 49–53.

- Bogg, T. , & Roberts, B. W. (2004). Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin , 130 , 887–919.

- Bogg, T. , & Roberts, B. W. (2013). The case for conscientiousness: Evidence and implications for a personality trait marker of health and longevity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine , 45 , 278–288.

- Bollen, K. A. , & Curran, P. J. (2004). Autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) models: A synthesis of two traditions . Sociological Methods and Research , 32 , 336–383.

- Carter, N. T. , Guan, L. , Maples, J. L. , Williamson, R. L. , & Miller, J. D. (2015). The downsides of extreme conscientiousness for psychological well-being: The role of obsessive compulsive tendencies . Journal of Personality , 84 , 510–522.

- Chapman, B. P. , Duberstein, P. R. , Sörensen, S. , Lyness, J. M. , & Emery, L. (2006). Personality and perceived health in older adults: The five-factor model in primary care . Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 61B (6), P362–P365.

- Chapman, B. P. , Hampson, S. E. , & Clarkin, J. (2014). Personality-informed interventions for healthy aging: Conclusions from a National Institute on Aging work group . Developmental Psychology , 50 , 1426–1441.

- Cohen, S. , Doyle, W. J. , Turner, R. B. , Alper, C. M. , & Skoner, D. (2003). Emotional style and susceptibility to the common cold. Psychosomatic Medicine , 65 , 652–657.

- Costa, P. J. , Weiss, A. , Duberstein, P. R. , Friedman, B. , & Siegler, I. C. (2014). Personality facets and all-cause mortality among Medicare patients aged 66 to 102 years: A follow-on study of Weiss and Costa (2005) . Psychosomatic Medicine , 76 , 370–378.

- Delvecchio, G. , Bellani, M. , Altamura, A. C. , & Brambilla, P. (2016). The association between the serotonin and dopamine neurotransmitters and personality traits . Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences , 25 (2), 109–112.

- DeSalvo, K. B. , Bloser, N. , Reynolds, K. , He, J. , & Muntner, P. (2006). Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question: A meta-analysis . Journal of General Internal Medicine , 21 (3), 267–275.

- Fagundes, C. P. , Glaser, R. , & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2013). Stressful early life experiences and immune dysregulation across the lifespan . Brain, Behavior, and Immunity , 27 , 8–12.

- Felitti, V. J. , Anda, R. F. , Nordenberg, D. , Williamson, D. F. , Spitz, A. M. , Edwards, V. , . . . Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 14 (4), 245–258.

- Ferguson, E. , & Bibby, P. A. (2012). Openness to experience and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis and r equivalent from risk ratios and odds ratios. British Journal of Health Psychology , 17 , 85–102.

- Figueredo, A. J. , & Rushton, J. P. (2009). Evidence for shared genetic dominance between the general factor of personality, mental and physical health, and life history traits . Twin Research and Human Genetics , 12 , 555–563.

- Freud, S. (1955). Collected works: Vol. 2. Studies on hysteria . New York: Hogarth.

- Freyd, J. J. Klest, B. , & Allard, C. B. (2005). Betrayal trauma: Relationship to physical health, psychological distress, and a written disclosure intervention. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation , 6 (3), 83–104.

- Friedman, H. S. (2000). Long-term relations of personality and health: Dynamisms, mechanisms, tropisms. Journal of Personality , 68 , 1089–1107.

- Friedman, H. S. , & Booth-Kewley, S. (1987). The “disease-prone personality”: A meta-analytic view of the construct . American Psychologist , 42 , 539–555.

- Friedman, H. S. , & Kern, M. L. (2014). Personality, well-being, and health . Annual Review of Psychology , 65 , 719–742.

- Friedman, H. S. , Tucker, J. S. , Schwartz, J. E. , Martin, L. R. , Tomlinson-Keasey, C. , Wingard, D. L. , & Criqui, M. H. (1995). Childhood conscientiousness and longevity: Health behaviors and cause of death . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 68 , 696–703.

- Friedman, H. S. , Tucker, J. S. , Schwartz, J. E. , Tomlinson-Keasy, C. , Martin, L. R. , Wingard, D. L. , & Criqui, M. H. (1995). Psychosocial and behavioral predictors of longevity: The aging and death of the “termites.” American Psychologist , 50 , 69–78.

- Friedman, H. S. , Tucker, J. S. , Tomlinson-Keasey, C. , Schwartz, J. E. , Wingard, D. L. , & Criqui, M. H. (1993). Does childhood personality predict longevity? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 65 , 176–185.

- Friedman, M. (1996). Type A behavior: Its diagnosis and treatment . New York: Plenum.

- Friedman, M. , & Rosenman, R. H. (1974). Type A behavior and your heart . New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Friedman, M. , Thoresen, C. , Gill, J. , Powell, L. , Ulmer, D. , Thompson, L. , . . . Edward Bourg . (1984). Alteration of Type A behavior and reduction in cardiac occurrences in postmyocardial infarction patients. American Heart Journal , 108 , 237–248.

- Funder, D. C. (2001). Personality. Annual Review of Psychology , 52 , 197–221.

- Galla, B. M. , & Wood, J. J. (2015). Trait self-control predicts adolescents’ exposure and reactivity to daily stressful events . Journal of Personality , 8 , 69–83.

- Goffman, E. (1990). The presentation of self in everyday life . London: Penguin.

- Goldberg, L. R. (2001). Analyses of Digman’s child-personality data: Derivation of big-five-factor scores from each of six samples . Journal of Personality , 69 , 709–743.

- Goodwin, R. D. , & Friedman, H. S. (2006). Health status and the five-factor personality traits in a nationally representative sample . Journal of Health Psychology , 11 , 643–654.

- Gouin, J.‑P. , Glaser, R. , Malarkey, W. B. , Beversdorf, D. , & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2012). Childhood abuse and inflammatory responses to daily stressors . Annals of Behavioral Medicine , 44 , 287–292.

- Grossardt, B. R. , Bower, J. H. , Geda, Y. E. , Colligan, R. C. , & Rocca, W. A. (2009). Pessimistic, anxious, and depressive personality traits predict all-cause mortality: The Mayo Clinic cohort study of personality and aging . Psychosomatic Medicine , 71 , 491–500.

- Hagger-Johnson, G. , Sabia, S. , Nabi, H. , Brunner, E. , Kivimaki, M. , Shipley, M. , & Singh-Manoux, A. (2012). Low conscientiousness and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality over 17 years: Whitehall II cohort study . Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 73 , 98–103.

- Hampson, S. E. , Edmonds, G. W. , Goldberg, L. R. , Barckley, M. , Klest, B. , Dubanoski , . . . Hillier, T. A. (2016). Lifetime trauma, personality traits, and health: A pathway to midlife health status . Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy , 8 (4), 447–454.

- Hampson, S. E. , Edmonds, G. W. , Goldberg, L. R. , Dubanoski, J. P. , & Hillier, T. A. (2013). Childhood conscientiousness relates to objectively measured adult physical health four decades later . Health Psychology , 32 , 925–928.

- Hampson, S. E. , Edmonds, G. W. , Goldberg, L. R. , Dubanoski, J. P. , & Hillier, T. A. (2015). A life-span behavioral mechanism relating childhood conscientiousness to adult clinical health . Health Psychology , 34 , 887–895.

- Hampson, S. E. , & Friedman, H. S. (2008). Personality and health: A lifespan perspective. In O. P. John , R. Robins , & L. Pervin (Eds.), The handbook of personality: Theory and research (3d ed., pp. 770–794). New York: Guilford.

- Hill, P. L. , Turiano, N. A. , Hurd, M. D. , Mroczek, D. K. , & Roberts, B. W. (2011). Conscientiousness and longevity: An examination of possible mediators . Health Psychology , 30 , 536–541.

- Houston, B. K. , & Snyder, C. R. (Eds.). (1988). Type A behavior pattern: Research, theory, and intervention . New York: Wiley.

- Hudson, N. W. , & Fraley, R. C. (2015). Volitional personality trait change: Can people choose to change their personality traits ? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 109 , 490–507.

- Israel, S. , Moffitt, T. E. , Belsky, D. W. , Hancox, R. J. , Poulton, R. , Roberts, B. , . . . Caspi, A. (2014). Translating personality psychology to help personalize preventive medicine for young adult patients . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 106 , 484–498.

- John, O. P. , Naumann, L. P. , & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy. In O. P. John , R. W. Robins , & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3d ed., pp. 114–158). New York: Guilford.

- Jokela, M. , Batty, G. D. , Hintsa, T. , Elovainio, M. , Hakulinen , & Kivimäki, M. (2014). Is personality associated with cancer incidence and mortality? An individual participant meta-analysis of 2156 incident cancer cases among 42 843 men and women . British Journal of Cancer , 110 , 1820–1824.

- Jokela, M. , Batty, G. D. , Nyberg, S. T. , Virtanen, M. , Nabi, H. , Singh-Manoux, A. , & Kivimäki, M. (2013). Personality and all-cause mortality: Individual-participant meta-analysis of 3,947 deaths in 76,150 adults. American Journal of Epidemiology , 178 , 667–675.

- Jokela, M. , Elovainio, M. , Nyberg, S. T. , Tabák, A. G. , Hintsa, T. , Batty, G. D. , & Kivimäki, M. (2014). Personality and risk of diabetes in adults: Pooled analysis of 5 cohort studies . Health Psychology , 33 , 1618–1621.

- Jokela, M. , Hakulinen, C. , Singh-Manoux, A. , & Kivimäki, M. (2014). Personality change associated with chronic diseases: Pooled analysis of four prospective cohort studies . Psychological Medicine , 44 , 2629–2640.

- Jokela, M. , Pulkki-Råback, L. , Elovainio, M. , & Kivimäki, M. (2014). Personality traits as risk factors for stroke and coronary heart disease mortality: Pooled analysis of three cohort studies . Journal of Behavioral Medicine , 37 , 881–889.

- Kern, M. L. , & Friedman, H. S. (2008). Do conscientious individuals live longer? A quantitative review . Health Psychology , 27 , 505–512.

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. , Gouin, J. , & Hantsoo, L. (2010). Close relationships, inflammation, and health . Psychophysiological biomarkers of health [Special issue]. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews , 35 , 33–38.

- Leikas, S. , & Salmela-Aro, K. (2015). Personality trait changes among young Finns: The role of life events and transitions . Journal of Personality , 83 , 117–126.

- Lodi-Smith, J. L. , Jackson, J. J. , Bogg, T. , Walton, K. , Wood, D. , Harms, P. D. , & Roberts, B. W. (2010). Mechanisms of health: Education and health-related behaviors partially mediate the relationship between conscientiousness and self-reported physical health . Psychology and Health , 25 , 305–319.

- Luchetti, M. , Barkley, J. M. , Stephan, Y. , Terracciano, A. , & Sutin, A. R. (2014). Five-factor model personality traits and inflammatory markers: New data and a meta-analysis . Psychoneuroendocrinology , 50 , 181–193.

- Magidson, J. F. , Roberts, B. W. , Collado-Rodriguez, A. , & Lejuez, C. W. (2014). Theory-driven intervention for changing personality: Expectancy value theory, behavioral activation, and conscientiousness . Developmental Psychology , 50 , 1442–1450.

- Marsh, H. W. , Nagengast, B. , & Morin, A. J. S. (2013). Measurement invariance of Big-Five factors over the life span: ESEM tests of gender, age, plasticity, maturity, and la dolce vita effects. Developmental Psychology , 49 , 1194–1218.

- McCaffery, J. M. , Frasure-Smith, N. , Dubé, M. , Théroux, P. , Rouleau, G. A. , Duan, Q. , & Lespérance, F. (2006). Common genetic vulnerability to depressive symptoms and coronary artery disease: A review and development of candidate genes related to inflammation and serotonin . Psychosomatic Medicine , 68 , 187–200.

- McCrae, R. R. , & Costa, P. T. (2008). The five-factor theory of personality. In O. P. John , R. W. Robins , & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3d ed., pp. 159–181). New York: Guilford.

- Meyer, G. J. , Finn, S. E. , Eyde, L. D. , Kay, G. G. , Moreland, K. L. , Dies, R. R. , . . . Reed, G. M. (2001). Psychological testing and psychological assessment: A review of evidence and issues . American Psychologist , 56 (2), 128–165.

- Moffitt, T. E. , Arseneault, L. , Belsky, D. , Dickson, N. , Hancox, R. J. , Harrington, H. , . . . Caspi, A. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety . PNAS: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 108 , 2693–2698.

- Mõttus, R. (2016). Towards more rigorous personality-trait outcome research . European Journal of Personality , 30 , 292–303.

- Mroczek, D. K. , & Spiro, A. (2007). Personality change influences mortality in older men . Psychological Science , 18 , 371–376.

- Murphy, M. L. M. , Miller, G. E. , & Wrosch, C. (2013). Conscientiousness and stress exposure and reactivity: A prospective study of adolescent females . Journal of Behavioral Medicine , 36 , 153–164.

- Ploubidis, G. B. , & Grundy, E. (2009). Personality and all-cause mortality: Evidence for indirect links . Personality and Individual Differences , 47 , 203–208.

- Pulkki-Råback, L. , Elovainio, M. , Hakulinen, C. , Lipsanen, J. , Hintsanen, M. , Jokela, M. , . . . Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2015). Cumulative effect of psychosocial factors in youth on ideal cardiovascular health in adulthood the cardiovascular risk in Young Finns study . Circulation , 131 , 245–253.

- Raitakari, O. T. , Juonala, M. , Rönnemaa, T. , Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. , Räsänen, L. , Pietikäinen , . . . Viikari, J. S. (2008). Cohort profile: The cardiovascular risk in Young Finns study . International Journal of Epidemiology , 37 , 1220–1226.

- Riese, H. , Snieder, H. , Jeronimus, B. F. , Korhonen, T. , Rose, R. J. , Kaprio, J. , & Ormel, J. (2014). Timing of stressful life events affects stability and change of neuroticism . European Journal of Personality , 28 , 193–200.

- Roberts, B. W. , Kuncel, N. R. , Shiner, R. , Caspi, A. , & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes . Perspectives on Psychological Science , 2 , 313–345.

- Schrepf, A. , Markon, K. , & Lutgendorf, S. K. (2014). From childhood trauma to elevated C-reactive protein in adulthood: The role of anxiety and emotional eating . Psychosomatic Medicine , 76 , 327–336.

- Seeman, T. E. (1996). Social ties and health: The benefits of social integration . Annals of Epidemiology , 6 , 442–451.

- Seeman, T. E. (2000). Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults . American Journal of Health Promotion , 14 , 362–370.

- Shanahan, M. J. , Hill, P. L. , Roberts, B. W. , Eccles, J. , & Friedman, H. S. (2014). Conscientiousness, health, and aging: The life course of personality model . Developmental Psychology , 50 , 1407–1425.

- Suls, J. , & Bunde, J. (2005). Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: The problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychological Bulletin , 131 , 260–300.

- Sutin, A. R. , Costa, P. T., Jr. , Uda, M. , Ferrucci, L. , Schlessinger, D. , & Terracciano, A. (2010). Personality and metabolic syndrome . Age , 32 , 513–519.

- Sutin, A. R. , Milaneschi, Y. , Cannas, A. , Ferrucci, L. , Uda, M. , Schlessinger, D. , . . . Terracciano, A. (2012). Impulsivity-related traits are associated with higher white blood cell counts . Journal of Behavioral Medicine , 35 , 616–623.

- Sutin, A. R. , Terracciano, A. , Deiana, B. , Uda, M. , Schlessinger, D. , Lakatta, E. G. , & Costa, P. J. (2010). Cholesterol, triglycerides, and the five-factor model of personality . Biological Psychology , 84 (2), 186–191.

- Sutin, A. R. , Zonderman, A. B. , Ferrucci, L. , & Terracciano, A. (2013). Personality traits and chronic disease: Implications for adult personality development . Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 68B , 912–920.

- Sutin, A. R. , Zonderman, A. B. , Uda, M. , Deiana, B. , Taub, D. D. , Longo, D. L. , . . . Terracciano, A. (2013) Personality traits and leptin . Psychosomatic Medicine , 75 , 505–509.

- Takahashi, Y. , Edmonds, G. W. , Jackson, J. J. , & Roberts, B. W. (2012). Longitudinal correlated changes in conscientiousness, preventative health-related behaviors, and self-perceived physical health . Journal of Personality , 81 , 417–427.

- Terman, L. M. , & Oden, M. H. (1947). Genetic studies of genius: Vol. 4. The gifted child grows up: Twenty-five years follow-up of a superior group . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Terracciano, A. , Strait, J. , Scuteri, A. , Meirelles, O. , Sutin, A. R. , Tarasov, K. , . . . Schlessinger, D. (2014). Personality traits and circadian blood pressure patterns: A 7-year prospective study . Psychosomatic Medicine , 76 , 237–243.

- Terracciano, A. , Sutin, A. R. , McCrae, R. R. , Deiana, B. , Ferrucci, L. , Schlessinger, D. , . . . Costa, P. J. (2009). Facets of personality linked to underweight and overweight . Psychosomatic Medicine , 71 , 682–689.

- Tucker, J. S. , Friedman, H. S. , Wingard, D. L. , & Schwartz, J. E. (1996). Marital history at mid-life as a predictor of longevity: Alternative explanations to the protective effect of marriage . Health Psychology , 15 , 94–101.

- Turiano, N. A. , Chapman, B. P. , Gruenewald, T. L. , & Mroczek, D. K. (2015). Personality and the leading behavioral contributors of mortality . Health Psychology , 34 , 51–60.

- Turiano, N. A. , Hill, P. L. , Roberts, B. W. , Spiro, A. , & Mroczek, D. K. (2012). Smoking mediates the effect of conscientiousness on mortality: The Veterans Affairs normative aging study . Journal of Research in Personality , 46 , 719–724.

- Turiano, N. A. , Spiro, A. I. , & Mroczek, D. K. (2012). Openness to experience and mortality in men: Analysis of trait and facets . Journal of Aging and Health , 24 , 654–672.

- Vollrath, M. E. (2001). Personality and stress. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology , 42 , 335–347.

- Weston, S. J. , & Jackson, J. J. (2015). Identification of the healthy neurotic: Personality traits predict smoking after disease onset . Journal of Research in Personality [R special issue], 54 , 61–69.

- Wilson, R. S. , Mendes de Leon, C. F. , Bienias, J. L. , Evans, D. A. , & Bennett, D. A. (2004). Personality and mortality in old age. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 59 (3), P110–P116.

Related Articles

- Stigma and Health

- Physical Activity and Personality Traits

- Personality Assessment in Clinical Psychology

- Loneliness and Health

- Human Aggression

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Psychology. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 16 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Character limit 500 /500

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, personality research in the 21st century: new developments and directions for the field.

Journal of Management History

ISSN : 1751-1348

Article publication date: 19 August 2022

Issue publication date: 6 April 2023

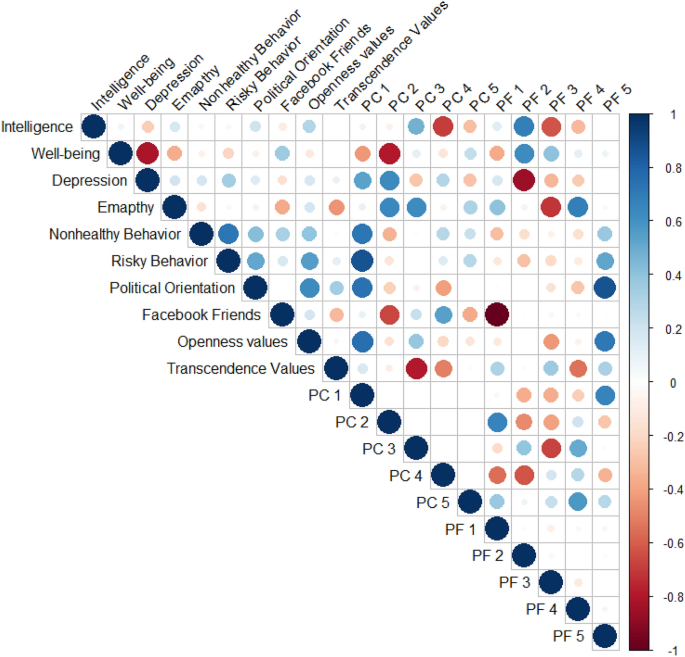

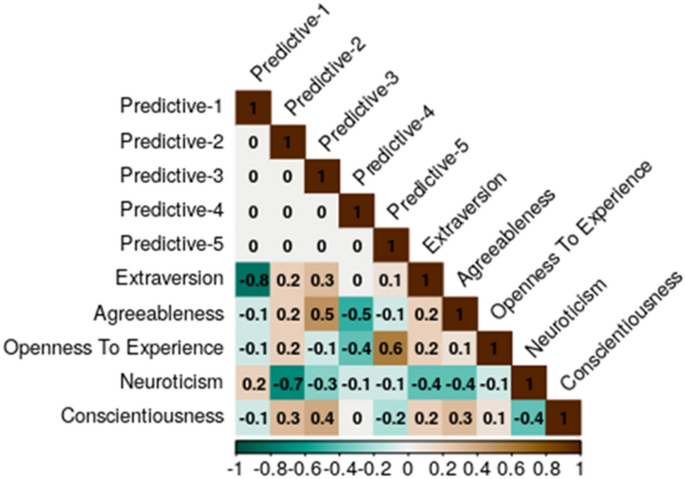

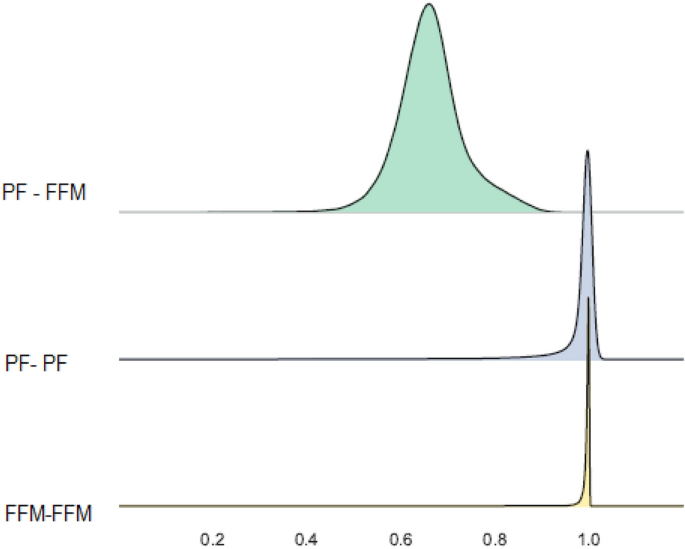

The purpose of this study is to systematically examine and classify the multitude of personality traits that have emerged in the literature beyond the Big Five (Five Factor Model) since the turn of the 21st century. The authors argue that this represents a new phase of personality research that is characterized both by construct proliferation and a movement away from the Big Five and demonstrates how personality as a construct has substantially evolved in the 21st century.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors conducted a comprehensive, systematic review of personality research from 2000 to 2020 across 17 management and psychology journals. This search yielded 1,901 articles, of which 440 were relevant and subsequently coded for this review.

The review presented in this study uncovers 155 traits, beyond the Big Five, that have been explored, which the authors organize and analyze into 10 distinct categories. Each category comprises a definition, lists the included traits and highlights an exemplar construct. The authors also specify the significant research outcomes associated with each trait category.

Originality/value

This review categorizes the 155 personality traits that have emerged in the management and psychology literature that describe personality beyond the Big Five. Based on these findings, this study proposes new avenues for future research and offers insights into the future of the field as the concept of personality has shifted in the 21st century.

- Personality

- Systematic literature review

Medina-Craven, M.N. , Ostermeier, K. , Sigdyal, P. and McLarty, B.D. (2023), "Personality research in the 21st century: new developments and directions for the field", Journal of Management History , Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 276-304. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMH-06-2022-0021

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Personality Impacts Our Daily Lives

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Verywell / Emily Roberts

Personality Characteristics

How personality develops, impact of personality, personality disorders.

Personality describes the unique patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that distinguish a person from others. A product of both biology and environment, it remains fairly consistent throughout life.

Examples of personality can be found in how we describe other people's traits. For instance, "She is generous, caring, and a bit of a perfectionist," or "They are loyal and protective of their friends."

The word "personality" stems from the Latin word persona , which refers to a theatrical mask worn by performers to play roles or disguise their identities.

Although there are many definitions of personality, most focus on the pattern of behaviors and characteristics that can help predict and explain a person's behavior.

Explanations for personality can focus on a variety of influences, ranging from genetic effects to the role of the environment and experience in shaping an individual's personality.

What exactly makes up a personality? Traits and patterns of thought and emotion play important roles, and so do these fundamental characteristics of personality:

- Consistency : There is generally a recognizable order and regularity to behaviors. Essentially, people act in the same way or in similar ways in a variety of situations.

- Both psychological and physiological : Personality is a psychological construct, but research suggests that it is also influenced by biological processes and needs.

- Affects behaviors and actions : Personality not only influences how we move and respond in our environment, but it also causes us to act in certain ways.

- Multiple expressions : Personality is displayed in more than just behavior. It can also be seen in our thoughts, feelings, close relationships, and other social interactions.

There are a number of theories about personality , and different schools of thought in psychology influence many of these theories. Some theories describe how personalities are expressed, and others focus more on how personality develops.

Type theories suggest that there are a limited number of personality types that are related to biological influences.

One theory suggests there are four types of personality. They are:

- Type A : Perfectionist, impatient, competitive, work-obsessed, achievement-oriented, aggressive, stressed

- Type B : Low stress, even- tempered , flexible, creative, adaptable to change, patient, tendency to procrastinate

- Type C : Highly conscientious, perfectionist, struggles to reveal emotions (positive and negative)

- Type D : Worrying, sad, irritable, pessimistic, negative self-talk, avoidance of social situations, lack of self-confidence, fear of rejection, appears gloomy, hopeless

There are other popular theories of personality types such as the Myers-Briggs theory. The Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator identifies a personality based on where someone is on four continuums: introversion-extraversion, sensing-intuition, thinking-feeling, and judging-perceiving.

After taking a Myers-Briggs personality test, you are assigned one of 16 personality types. Examples of these personality types are:

- ISTJ : Introverted, sensing, thinking, and judging. People with this personality type are logical and organized; they also tend to be judgmental.

- INFP : Introverted, intuitive, feeling, and perceiving. They tend to be idealists and sensitive to their feelings.

- ESTJ : Extroverted, sensing, thinking, and judging. They tend to be assertive and concerned with following the rules.

- ENFJ : Extroverted, intuitive, feeling, and judging. They are known as "givers" for being warm and loyal; they may also be overprotective.

Personality Tests

In addition to the MBTI, some of the most well-known personality inventories are:

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

- HEXACO Personality Inventory

- Caddell's 16PF Personality Questionnaire

- Enneagram Typology

Personality Traits

Trait theories tend to view personality as the result of internal characteristics that are genetically based and include:

- Agreeable : Cares about others, feels empathy, enjoys helping others

- Conscientiousness : High levels of thoughtfulness, good impulse control, goal-directed behaviors

- Eager-to-please : Accommodating, passive, and conforming

- Extraversion : Excitability, sociability, talkativeness, assertiveness, and high amounts of emotional expressiveness

- Introversion : Quiet, reserved

- Neuroticism : Experiences stress and dramatic shifts in mood, feels anxious, worries about different things, gets upset easily, struggles to bounce back after stressful events

- Openness : Very creative , open to trying new things, focuses on tackling new challenges

Try Our Free Personality Test

Our fast and free personality test can help give you an idea of your dominant personality traits and how they may influence your behaviors.

Psychodynamic Theories

Psychodynamic theories of personality are heavily influenced by the work of Sigmund Freud and emphasize the influence of the unconscious mind on personality. Psychodynamic theories include Sigmund Freud’s psychosexual stage theory and Erik Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development .

Behavioral Theories

Behavioral theories suggest that personality is a result of interaction between the individual and the environment. Behavioral theorists study observable and measurable behaviors, often ignoring the role of internal thoughts and feelings. Behavioral theorists include B.F. Skinner and John B. Watson .

Humanist theories emphasize the importance of free will and individual experience in developing a personality. Humanist theorists include Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow .

Research on personality can yield fascinating insights into how personality develops and changes over the course of a lifetime. This research can also have important practical applications in the real world.

For example, people can use a personality assessment (also called a personality test or personality quiz) to learn more about themselves and their unique strengths, weaknesses, and preferences. Some assessments might look at how people rank on specific traits, such as whether they are high in extroversion , conscientiousness, or openness.

Other assessments might measure how specific aspects of personality change over time. Some assessments give people insight into how their personality affects many areas of their lives, including career, relationships, personal growth, and more.

Understanding your personality type can help you determine what career you might enjoy, how well you might perform in certain job roles, or how effective a form of psychotherapy could be for you.

Personality type can also have an impact on your health, including how often you visit the doctor and how you cope with stress. Researchers have found that certain personality characteristics may be linked to illness and health behaviors.

While personality determines what you think and how you behave, personality disorders are marked by thoughts and behavior that are disruptive and distressing in everyday life. Someone with a personality disorder may have trouble recognizing their condition because their symptoms are ingrained in their personality.

Personality disorders include paranoid personality disorder , schizoid personality disorder , antisocial personality disorder , borderline personality disorder (BPD), and narcissistic personality disorder (NPD).

While the symptoms of personality disorders vary based on the condition, some common signs include:

- Aggressive behavior

- Delusional thinking

- Distrust of others

- Flat emotions (no emotional range)

- Lack of interest in relationships

- Violating others' boundaries

Some people with BPD experience suicidal thoughts or behavior as well.