- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

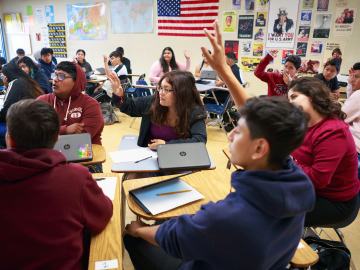

Credit: August de Richelieu

Does homework still have value? A Johns Hopkins education expert weighs in

Joyce epstein, co-director of the center on school, family, and community partnerships, discusses why homework is essential, how to maximize its benefit to learners, and what the 'no-homework' approach gets wrong.

By Vicky Hallett

The necessity of homework has been a subject of debate since at least as far back as the 1890s, according to Joyce L. Epstein , co-director of the Center on School, Family, and Community Partnerships at Johns Hopkins University. "It's always been the case that parents, kids—and sometimes teachers, too—wonder if this is just busy work," Epstein says.

But after decades of researching how to improve schools, the professor in the Johns Hopkins School of Education remains certain that homework is essential—as long as the teachers have done their homework, too. The National Network of Partnership Schools , which she founded in 1995 to advise schools and districts on ways to improve comprehensive programs of family engagement, has developed hundreds of improved homework ideas through its Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program. For an English class, a student might interview a parent on popular hairstyles from their youth and write about the differences between then and now. Or for science class, a family could identify forms of matter over the dinner table, labeling foods as liquids or solids. These innovative and interactive assignments not only reinforce concepts from the classroom but also foster creativity, spark discussions, and boost student motivation.

"We're not trying to eliminate homework procedures, but expand and enrich them," says Epstein, who is packing this research into a forthcoming book on the purposes and designs of homework. In the meantime, the Hub couldn't wait to ask her some questions:

What kind of homework training do teachers typically get?

Future teachers and administrators really have little formal training on how to design homework before they assign it. This means that most just repeat what their teachers did, or they follow textbook suggestions at the end of units. For example, future teachers are well prepared to teach reading and literacy skills at each grade level, and they continue to learn to improve their teaching of reading in ongoing in-service education. By contrast, most receive little or no training on the purposes and designs of homework in reading or other subjects. It is really important for future teachers to receive systematic training to understand that they have the power, opportunity, and obligation to design homework with a purpose.

Why do students need more interactive homework?

If homework assignments are always the same—10 math problems, six sentences with spelling words—homework can get boring and some kids just stop doing their assignments, especially in the middle and high school years. When we've asked teachers what's the best homework you've ever had or designed, invariably we hear examples of talking with a parent or grandparent or peer to share ideas. To be clear, parents should never be asked to "teach" seventh grade science or any other subject. Rather, teachers set up the homework assignments so that the student is in charge. It's always the student's homework. But a good activity can engage parents in a fun, collaborative way. Our data show that with "good" assignments, more kids finish their work, more kids interact with a family partner, and more parents say, "I learned what's happening in the curriculum." It all works around what the youngsters are learning.

Is family engagement really that important?

At Hopkins, I am part of the Center for Social Organization of Schools , a research center that studies how to improve many aspects of education to help all students do their best in school. One thing my colleagues and I realized was that we needed to look deeply into family and community engagement. There were so few references to this topic when we started that we had to build the field of study. When children go to school, their families "attend" with them whether a teacher can "see" the parents or not. So, family engagement is ever-present in the life of a school.

My daughter's elementary school doesn't assign homework until third grade. What's your take on "no homework" policies?

There are some parents, writers, and commentators who have argued against homework, especially for very young children. They suggest that children should have time to play after school. This, of course is true, but many kindergarten kids are excited to have homework like their older siblings. If they give homework, most teachers of young children make assignments very short—often following an informal rule of 10 minutes per grade level. "No homework" does not guarantee that all students will spend their free time in productive and imaginative play.

Some researchers and critics have consistently misinterpreted research findings. They have argued that homework should be assigned only at the high school level where data point to a strong connection of doing assignments with higher student achievement . However, as we discussed, some students stop doing homework. This leads, statistically, to results showing that doing homework or spending more minutes on homework is linked to higher student achievement. If slow or struggling students are not doing their assignments, they contribute to—or cause—this "result."

Teachers need to design homework that even struggling students want to do because it is interesting. Just about all students at any age level react positively to good assignments and will tell you so.

Did COVID change how schools and parents view homework?

Within 24 hours of the day school doors closed in March 2020, just about every school and district in the country figured out that teachers had to talk to and work with students' parents. This was not the same as homeschooling—teachers were still working hard to provide daily lessons. But if a child was learning at home in the living room, parents were more aware of what they were doing in school. One of the silver linings of COVID was that teachers reported that they gained a better understanding of their students' families. We collected wonderfully creative examples of activities from members of the National Network of Partnership Schools. I'm thinking of one art activity where every child talked with a parent about something that made their family unique. Then they drew their finding on a snowflake and returned it to share in class. In math, students talked with a parent about something the family liked so much that they could represent it 100 times. Conversations about schoolwork at home was the point.

How did you create so many homework activities via the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork program?

We had several projects with educators to help them design interactive assignments, not just "do the next three examples on page 38." Teachers worked in teams to create TIPS activities, and then we turned their work into a standard TIPS format in math, reading/language arts, and science for grades K-8. Any teacher can use or adapt our prototypes to match their curricula.

Overall, we know that if future teachers and practicing educators were prepared to design homework assignments to meet specific purposes—including but not limited to interactive activities—more students would benefit from the important experience of doing their homework. And more parents would, indeed, be partners in education.

Posted in Voices+Opinion

You might also like

News network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Should We Get Rid of Homework?

Some educators are pushing to get rid of homework. Would that be a good thing?

By Jeremy Engle and Michael Gonchar

Do you like doing homework? Do you think it has benefited you educationally?

Has homework ever helped you practice a difficult skill — in math, for example — until you mastered it? Has it helped you learn new concepts in history or science? Has it helped to teach you life skills, such as independence and responsibility? Or, have you had a more negative experience with homework? Does it stress you out, numb your brain from busywork or actually make you fall behind in your classes?

Should we get rid of homework?

In “ The Movement to End Homework Is Wrong, ” published in July, the Times Opinion writer Jay Caspian Kang argues that homework may be imperfect, but it still serves an important purpose in school. The essay begins:

Do students really need to do their homework? As a parent and a former teacher, I have been pondering this question for quite a long time. The teacher side of me can acknowledge that there were assignments I gave out to my students that probably had little to no academic value. But I also imagine that some of my students never would have done their basic reading if they hadn’t been trained to complete expected assignments, which would have made the task of teaching an English class nearly impossible. As a parent, I would rather my daughter not get stuck doing the sort of pointless homework I would occasionally assign, but I also think there’s a lot of value in saying, “Hey, a lot of work you’re going to end up doing in your life is pointless, so why not just get used to it?” I certainly am not the only person wondering about the value of homework. Recently, the sociologist Jessica McCrory Calarco and the mathematics education scholars Ilana Horn and Grace Chen published a paper, “ You Need to Be More Responsible: The Myth of Meritocracy and Teachers’ Accounts of Homework Inequalities .” They argued that while there’s some evidence that homework might help students learn, it also exacerbates inequalities and reinforces what they call the “meritocratic” narrative that says kids who do well in school do so because of “individual competence, effort and responsibility.” The authors believe this meritocratic narrative is a myth and that homework — math homework in particular — further entrenches the myth in the minds of teachers and their students. Calarco, Horn and Chen write, “Research has highlighted inequalities in students’ homework production and linked those inequalities to differences in students’ home lives and in the support students’ families can provide.”

Mr. Kang argues:

But there’s a defense of homework that doesn’t really have much to do with class mobility, equality or any sense of reinforcing the notion of meritocracy. It’s one that became quite clear to me when I was a teacher: Kids need to learn how to practice things. Homework, in many cases, is the only ritualized thing they have to do every day. Even if we could perfectly equalize opportunity in school and empower all students not to be encumbered by the weight of their socioeconomic status or ethnicity, I’m not sure what good it would do if the kids didn’t know how to do something relentlessly, over and over again, until they perfected it. Most teachers know that type of progress is very difficult to achieve inside the classroom, regardless of a student’s background, which is why, I imagine, Calarco, Horn and Chen found that most teachers weren’t thinking in a structural inequalities frame. Holistic ideas of education, in which learning is emphasized and students can explore concepts and ideas, are largely for the types of kids who don’t need to worry about class mobility. A defense of rote practice through homework might seem revanchist at this moment, but if we truly believe that schools should teach children lessons that fall outside the meritocracy, I can’t think of one that matters more than the simple satisfaction of mastering something that you were once bad at. That takes homework and the acknowledgment that sometimes a student can get a question wrong and, with proper instruction, eventually get it right.

Students, read the entire article, then tell us:

Should we get rid of homework? Why, or why not?

Is homework an outdated, ineffective or counterproductive tool for learning? Do you agree with the authors of the paper that homework is harmful and worsens inequalities that exist between students’ home circumstances?

Or do you agree with Mr. Kang that homework still has real educational value?

When you get home after school, how much homework will you do? Do you think the amount is appropriate, too much or too little? Is homework, including the projects and writing assignments you do at home, an important part of your learning experience? Or, in your opinion, is it not a good use of time? Explain.

In these letters to the editor , one reader makes a distinction between elementary school and high school:

Homework’s value is unclear for younger students. But by high school and college, homework is absolutely essential for any student who wishes to excel. There simply isn’t time to digest Dostoyevsky if you only ever read him in class.

What do you think? How much does grade level matter when discussing the value of homework?

Is there a way to make homework more effective?

If you were a teacher, would you assign homework? What kind of assignments would you give and why?

Want more writing prompts? You can find all of our questions in our Student Opinion column . Teachers, check out this guide to learn how you can incorporate them into your classroom.

Students 13 and older in the United States and Britain, and 16 and older elsewhere, are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

Jeremy Engle joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2018 after spending more than 20 years as a classroom humanities and documentary-making teacher, professional developer and curriculum designer working with students and teachers across the country. More about Jeremy Engle

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in.

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas about workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework.

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says, he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy workloads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold , says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace , says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework can cause, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says, homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends, from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no-homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely but to be more mindful of the type of work students take home, suggests Kang, who was a high school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework; I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the past two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic , making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized. ... Sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking up assignments can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

More: Some teachers let their students sleep in class. Here's what mental health experts say.

More: Some parents are slipping young kids in for the COVID-19 vaccine, but doctors discourage the move as 'risky'

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71970990/05_nohomework_Jiayue_Li.0.jpg)

Filed under:

- The Highlight

Nobody knows what the point of homework is

The homework wars are back.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Nobody knows what the point of homework is

As the Covid-19 pandemic began and students logged into their remote classrooms, all work, in effect, became homework. But whether or not students could complete it at home varied. For some, schoolwork became public-library work or McDonald’s-parking-lot work.

Luis Torres, the principal of PS 55, a predominantly low-income community elementary school in the south Bronx, told me that his school secured Chromebooks for students early in the pandemic only to learn that some lived in shelters that blocked wifi for security reasons. Others, who lived in housing projects with poor internet reception, did their schoolwork in laundromats.

According to a 2021 Pew survey , 25 percent of lower-income parents said their children, at some point, were unable to complete their schoolwork because they couldn’t access a computer at home; that number for upper-income parents was 2 percent.

The issues with remote learning in March 2020 were new. But they highlighted a divide that had been there all along in another form: homework. And even long after schools have resumed in-person classes, the pandemic’s effects on homework have lingered.

Over the past three years, in response to concerns about equity, schools across the country, including in Sacramento, Los Angeles , San Diego , and Clark County, Nevada , made permanent changes to their homework policies that restricted how much homework could be given and how it could be graded after in-person learning resumed.

Three years into the pandemic, as districts and teachers reckon with Covid-era overhauls of teaching and learning, schools are still reconsidering the purpose and place of homework. Whether relaxing homework expectations helps level the playing field between students or harms them by decreasing rigor is a divisive issue without conclusive evidence on either side, echoing other debates in education like the elimination of standardized test scores from some colleges’ admissions processes.

I first began to wonder if the homework abolition movement made sense after speaking with teachers in some Massachusetts public schools, who argued that rather than help disadvantaged kids, stringent homework restrictions communicated an attitude of low expectations. One, an English teacher, said she felt the school had “just given up” on trying to get the students to do work; another argued that restrictions that prohibit teachers from assigning take-home work that doesn’t begin in class made it difficult to get through the foreign-language curriculum. Teachers in other districts have raised formal concerns about homework abolition’s ability to close gaps among students rather than widening them.

Many education experts share this view. Harris Cooper, a professor emeritus of psychology at Duke who has studied homework efficacy, likened homework abolition to “playing to the lowest common denominator.”

But as I learned after talking to a variety of stakeholders — from homework researchers to policymakers to parents of schoolchildren — whether to abolish homework probably isn’t the right question. More important is what kind of work students are sent home with and where they can complete it. Chances are, if schools think more deeply about giving constructive work, time spent on homework will come down regardless.

There’s no consensus on whether homework works

The rise of the no-homework movement during the Covid-19 pandemic tapped into long-running disagreements over homework’s impact on students. The purpose and effectiveness of homework have been disputed for well over a century. In 1901, for instance, California banned homework for students up to age 15, and limited it for older students, over concerns that it endangered children’s mental and physical health. The newest iteration of the anti-homework argument contends that the current practice punishes students who lack support and rewards those with more resources, reinforcing the “myth of meritocracy.”

But there is still no research consensus on homework’s effectiveness; no one can seem to agree on what the right metrics are. Much of the debate relies on anecdotes, intuition, or speculation.

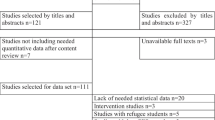

Researchers disagree even on how much research exists on the value of homework. Kathleen Budge, the co-author of Turning High-Poverty Schools Into High-Performing Schools and a professor at Boise State, told me that homework “has been greatly researched.” Denise Pope, a Stanford lecturer and leader of the education nonprofit Challenge Success, said, “It’s not a highly researched area because of some of the methodological problems.”

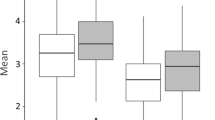

Experts who are more sympathetic to take-home assignments generally support the “10-minute rule,” a framework that estimates the ideal amount of homework on any given night by multiplying the student’s grade by 10 minutes. (A ninth grader, for example, would have about 90 minutes of work a night.) Homework proponents argue that while it is difficult to design randomized control studies to test homework’s effectiveness, the vast majority of existing studies show a strong positive correlation between homework and high academic achievement for middle and high school students. Prominent critics of homework argue that these correlational studies are unreliable and point to studies that suggest a neutral or negative effect on student performance. Both agree there is little to no evidence for homework’s effectiveness at an elementary school level, though proponents often argue that it builds constructive habits for the future.

For anyone who remembers homework assignments from both good and bad teachers, this fundamental disagreement might not be surprising. Some homework is pointless and frustrating to complete. Every week during my senior year of high school, I had to analyze a poem for English and decorate it with images found on Google; my most distinct memory from that class is receiving a demoralizing 25-point deduction because I failed to present my analysis on a poster board. Other assignments really do help students learn: After making an adapted version of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book for a ninth grade history project, I was inspired to check out from the library and read a biography of the Chinese ruler.

For homework opponents, the first example is more likely to resonate. “We’re all familiar with the negative effects of homework: stress, exhaustion, family conflict, less time for other activities, diminished interest in learning,” Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, which challenges common justifications for homework, told me in an email. “And these effects may be most pronounced among low-income students.” Kohn believes that schools should make permanent any moratoria implemented during the pandemic, arguing that there are no positives at all to outweigh homework’s downsides. Recent studies , he argues , show the benefits may not even materialize during high school.

In the Marlborough Public Schools, a suburban district 45 minutes west of Boston, school policy committee chair Katherine Hennessy described getting kids to complete their homework during remote education as “a challenge, to say the least.” Teachers found that students who spent all day on their computers didn’t want to spend more time online when the day was over. So, for a few months, the school relaxed the usual practice and teachers slashed the quantity of nightly homework.

Online learning made the preexisting divides between students more apparent, she said. Many students, even during normal circumstances, lacked resources to keep them on track and focused on completing take-home assignments. Though Marlborough Schools is more affluent than PS 55, Hennessy said many students had parents whose work schedules left them unable to provide homework help in the evenings. The experience tracked with a common divide in the country between children of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

So in October 2021, months after the homework reduction began, the Marlborough committee made a change to the district’s policy. While teachers could still give homework, the assignments had to begin as classwork. And though teachers could acknowledge homework completion in a student’s participation grade, they couldn’t count homework as its own grading category. “Rigorous learning in the classroom does not mean that that classwork must be assigned every night,” the policy stated . “Extensions of class work is not to be used to teach new content or as a form of punishment.”

Canceling homework might not do anything for the achievement gap

The critiques of homework are valid as far as they go, but at a certain point, arguments against homework can defy the commonsense idea that to retain what they’re learning, students need to practice it.

“Doesn’t a kid become a better reader if he reads more? Doesn’t a kid learn his math facts better if he practices them?” said Cathy Vatterott, an education researcher and professor emeritus at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. After decades of research, she said it’s still hard to isolate the value of homework, but that doesn’t mean it should be abandoned.

Blanket vilification of homework can also conflate the unique challenges facing disadvantaged students as compared to affluent ones, which could have different solutions. “The kids in the low-income schools are being hurt because they’re being graded, unfairly, on time they just don’t have to do this stuff,” Pope told me. “And they’re still being held accountable for turning in assignments, whether they’re meaningful or not.” On the other side, “Palo Alto kids” — students in Silicon Valley’s stereotypically pressure-cooker public schools — “are just bombarded and overloaded and trying to stay above water.”

Merely getting rid of homework doesn’t solve either problem. The United States already has the second-highest disparity among OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations between time spent on homework by students of high and low socioeconomic status — a difference of more than three hours, said Janine Bempechat, clinical professor at Boston University and author of No More Mindless Homework .

When she interviewed teachers in Boston-area schools that had cut homework before the pandemic, Bempechat told me, “What they saw immediately was parents who could afford it immediately enrolled their children in the Russian School of Mathematics,” a math-enrichment program whose tuition ranges from $140 to about $400 a month. Getting rid of homework “does nothing for equity; it increases the opportunity gap between wealthier and less wealthy families,” she said. “That solution troubles me because it’s no solution at all.”

A group of teachers at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia, made the same point after the school district proposed an overhaul of its homework policies, including removing penalties for missing homework deadlines, allowing unlimited retakes, and prohibiting grading of homework.

“Given the emphasis on equity in today’s education systems,” they wrote in a letter to the school board, “we believe that some of the proposed changes will actually have a detrimental impact towards achieving this goal. Families that have means could still provide challenging and engaging academic experiences for their children and will continue to do so, especially if their children are not experiencing expected rigor in the classroom.” At a school where more than a third of students are low-income, the teachers argued, the policies would prompt students “to expect the least of themselves in terms of effort, results, and responsibility.”

Not all homework is created equal

Despite their opposing sides in the homework wars, most of the researchers I spoke to made a lot of the same points. Both Bempechat and Pope were quick to bring up how parents and schools confuse rigor with workload, treating the volume of assignments as a proxy for quality of learning. Bempechat, who is known for defending homework, has written extensively about how plenty of it lacks clear purpose, requires the purchasing of unnecessary supplies, and takes longer than it needs to. Likewise, when Pope instructs graduate-level classes on curriculum, she asks her students to think about the larger purpose they’re trying to achieve with homework: If they can get the job done in the classroom, there’s no point in sending home more work.

At its best, pandemic-era teaching facilitated that last approach. Honolulu-based teacher Christina Torres Cawdery told me that, early in the pandemic, she often had a cohort of kids in her classroom for four hours straight, as her school tried to avoid too much commingling. She couldn’t lecture for four hours, so she gave the students plenty of time to complete independent and project-based work. At the end of most school days, she didn’t feel the need to send them home with more to do.

A similar limited-homework philosophy worked at a public middle school in Chelsea, Massachusetts. A couple of teachers there turned as much class as possible into an opportunity for small-group practice, allowing kids to work on problems that traditionally would be assigned for homework, Jessica Flick, a math coach who leads department meetings at the school, told me. It was inspired by a philosophy pioneered by Simon Fraser University professor Peter Liljedahl, whose influential book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics reframes homework as “check-your-understanding questions” rather than as compulsory work. Last year, Flick found that the two eighth grade classes whose teachers adopted this strategy performed the best on state tests, and this year, she has encouraged other teachers to implement it.

Teachers know that plenty of homework is tedious and unproductive. Jeannemarie Dawson De Quiroz, who has taught for more than 20 years in low-income Boston and Los Angeles pilot and charter schools, says that in her first years on the job she frequently assigned “drill and kill” tasks and questions that she now feels unfairly stumped students. She said designing good homework wasn’t part of her teaching programs, nor was it meaningfully discussed in professional development. With more experience, she turned as much class time as she could into practice time and limited what she sent home.

“The thing about homework that’s sticky is that not all homework is created equal,” says Jill Harrison Berg, a former teacher and the author of Uprooting Instructional Inequity . “Some homework is a genuine waste of time and requires lots of resources for no good reason. And other homework is really useful.”

Cutting homework has to be part of a larger strategy

The takeaways are clear: Schools can make cuts to homework, but those cuts should be part of a strategy to improve the quality of education for all students. If the point of homework was to provide more practice, districts should think about how students can make it up during class — or offer time during or after school for students to seek help from teachers. If it was to move the curriculum along, it’s worth considering whether strategies like Liljedahl’s can get more done in less time.

Some of the best thinking around effective assignments comes from those most critical of the current practice. Denise Pope proposes that, before assigning homework, teachers should consider whether students understand the purpose of the work and whether they can do it without help. If teachers think it’s something that can’t be done in class, they should be mindful of how much time it should take and the feedback they should provide. It’s questions like these that De Quiroz considered before reducing the volume of work she sent home.

More than a year after the new homework policy began in Marlborough, Hennessy still hears from parents who incorrectly “think homework isn’t happening” despite repeated assurances that kids still can receive work. She thinks part of the reason is that education has changed over the years. “I think what we’re trying to do is establish that homework may be an element of educating students,” she told me. “But it may not be what parents think of as what they grew up with. ... It’s going to need to adapt, per the teaching and the curriculum, and how it’s being delivered in each classroom.”

For the policy to work, faculty, parents, and students will all have to buy into a shared vision of what school ought to look like. The district is working on it — in November, it hosted and uploaded to YouTube a round-table discussion on homework between district administrators — but considering the sustained confusion, the path ahead seems difficult.

When I asked Luis Torres about whether he thought homework serves a useful part in PS 55’s curriculum, he said yes, of course it was — despite the effort and money it takes to keep the school open after hours to help them do it. “The children need the opportunity to practice,” he said. “If you don’t give them opportunities to practice what they learn, they’re going to forget.” But Torres doesn’t care if the work is done at home. The school stays open until around 6 pm on weekdays, even during breaks. Tutors through New York City’s Department of Youth and Community Development programs help kids with work after school so they don’t need to take it with them.

As schools weigh the purpose of homework in an unequal world, it’s tempting to dispose of a practice that presents real, practical problems to students across the country. But getting rid of homework is unlikely to do much good on its own. Before cutting it, it’s worth thinking about what good assignments are meant to do in the first place. It’s crucial that students from all socioeconomic backgrounds tackle complex quantitative problems and hone their reading and writing skills. It’s less important that the work comes home with them.

Jacob Sweet is a freelance writer in Somerville, Massachusetts. He is a frequent contributor to the New Yorker, among other publications.

Will you support Vox today?

Millions rely on Vox’s journalism to understand the coronavirus crisis. We believe it pays off for all of us, as a society and a democracy, when our neighbors and fellow citizens can access clear, concise information on the pandemic. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive. Support from our readers helps us keep it free for everyone. If you have already made a financial contribution to Vox, thank you. If not, please consider making a contribution today from as little as $3.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Social media platforms aren’t equipped to handle the negative effects of their algorithms abroad. Neither is the law.

The real science behind the billionaire pursuit of immortality, if you want to belong, find a third place, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

- Our Mission

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

School Life Balance , Tips for Online Students

The Pros and Cons of Homework

Updated: December 7, 2023

Published: January 23, 2020

Homework is a word that most students dread hearing. After hours upon hours of sitting in class , the last thing we want is more schoolwork over our precious weekends. While it’s known to be a staple of traditional schooling, homework has also become a rather divise topic. Some feel as though homework is a necessary part of school, while others believe that the time could be better invested. Should students have homework? Have a closer look into the arguments on both sides to decide for yourself.

Photo by energepic.com from Pexels

Why should students have homework, 1. homework encourages practice.

Many people believe that one of the positive effects of homework is that it encourages the discipline of practice. While it may be time consuming and boring compared to other activities, repetition is needed to get better at skills. Homework helps make concepts more clear, and gives students more opportunities when starting their career .

2. Homework Gets Parents Involved

Homework can be something that gets parents involved in their children’s lives if the environment is a healthy one. A parent helping their child with homework makes them take part in their academic success, and allows for the parent to keep up with what the child is doing in school. It can also be a chance to connect together.

3. Homework Teaches Time Management

Homework is much more than just completing the assigned tasks. Homework can develop time management skills , forcing students to plan their time and make sure that all of their homework assignments are done on time. By learning to manage their time, students also practice their problem-solving skills and independent thinking. One of the positive effects of homework is that it forces decision making and compromises to be made.

4. Homework Opens A Bridge Of Communication

Homework creates a connection between the student, the teacher, the school, and the parents. It allows everyone to get to know each other better, and parents can see where their children are struggling. In the same sense, parents can also see where their children are excelling. Homework in turn can allow for a better, more targeted educational plan for the student.

5. Homework Allows For More Learning Time

Homework allows for more time to complete the learning process. School hours are not always enough time for students to really understand core concepts, and homework can counter the effects of time shortages, benefiting students in the long run, even if they can’t see it in the moment.

6. Homework Reduces Screen Time

Many students in North America spend far too many hours watching TV. If they weren’t in school, these numbers would likely increase even more. Although homework is usually undesired, it encourages better study habits and discourages spending time in front of the TV. Homework can be seen as another extracurricular activity, and many families already invest a lot of time and money in different clubs and lessons to fill up their children’s extra time. Just like extracurricular activities, homework can be fit into one’s schedule.

The Other Side: Why Homework Is Bad

1. homework encourages a sedentary lifestyle.

Should students have homework? Well, that depends on where you stand. There are arguments both for the advantages and the disadvantages of homework.

While classroom time is important, playground time is just as important. If children are given too much homework, they won’t have enough playtime, which can impact their social development and learning. Studies have found that those who get more play get better grades in school , as it can help them pay closer attention in the classroom.

Children are already sitting long hours in the classroom, and homework assignments only add to these hours. Sedentary lifestyles can be dangerous and can cause health problems such as obesity. Homework takes away from time that could be spent investing in physical activity.

2. Homework Isn’t Healthy In Every Home

While many people that think homes are a beneficial environment for children to learn, not all homes provide a healthy environment, and there may be very little investment from parents. Some parents do not provide any kind of support or homework help, and even if they would like to, due to personal barriers, they sometimes cannot. Homework can create friction between children and their parents, which is one of the reasons why homework is bad .

3. Homework Adds To An Already Full-Time Job

School is already a full-time job for students, as they generally spend over 6 hours each day in class. Students also often have extracurricular activities such as sports, music, or art that are just as important as their traditional courses. Adding on extra hours to all of these demands is a lot for children to manage, and prevents students from having extra time to themselves for a variety of creative endeavors. Homework prevents self discovery and having the time to learn new skills outside of the school system. This is one of the main disadvantages of homework.

4. Homework Has Not Been Proven To Provide Results

Endless surveys have found that homework creates a negative attitude towards school, and homework has not been found to be linked to a higher level of academic success.

The positive effects of homework have not been backed up enough. While homework may help some students improve in specific subjects, if they have outside help there is no real proof that homework makes for improvements.

It can be a challenge to really enforce the completion of homework, and students can still get decent grades without doing their homework. Extra school time does not necessarily mean better grades — quality must always come before quantity.

Accurate practice when it comes to homework simply isn’t reliable. Homework could even cause opposite effects if misunderstood, especially since the reliance is placed on the student and their parents — one of the major reasons as to why homework is bad. Many students would rather cheat in class to avoid doing their homework at home, and children often just copy off of each other or from what they read on the internet.

5. Homework Assignments Are Overdone

The general agreement is that students should not be given more than 10 minutes a day per grade level. What this means is that a first grader should be given a maximum of 10 minutes of homework, while a second grader receives 20 minutes, etc. Many students are given a lot more homework than the recommended amount, however.

On average, college students spend as much as 3 hours per night on homework . By giving too much homework, it can increase stress levels and lead to burn out. This in turn provides an opposite effect when it comes to academic success.

The pros and cons of homework are both valid, and it seems as though the question of ‘‘should students have homework?’ is not a simple, straightforward one. Parents and teachers often are found to be clashing heads, while the student is left in the middle without much say.

It’s important to understand all the advantages and disadvantages of homework, taking both perspectives into conversation to find a common ground. At the end of the day, everyone’s goal is the success of the student.

Related Articles

This is why we should stop giving homework

At Human Restoration Project, one of the core systemic changes we suggest is the elimination of homework. Throughout this piece, I will outline several research studies and reports that demonstrate how the negative impact of homework is so evident that any mandated homework, outside of some minor catching up or for incredibly niche cases, simply does more harm than good.

I’ll summarize four main reasons why homework just flat out doesn’t make sense.

- Achievement, whether that be measured through standardized tests or general academic knowledge, isn’t correlated to assigning or completing homework.

- Homework is an inequitable practice that harms certain individuals more than others, to the detriment of those with less resources and to minor, if any, improvement for those with resources.

- It contributes to negative impacts at home with one’s family, peer relationships, and just general school-life balance, which causes far more problems than homework is meant to solve.

- And finally, it highlights and exacerbates our obsession with ultra-competitive college admissions and job opportunities, and other detrimental faults of making everything about getting ahead .

Does Homework Make Us Learn More?

Homework is such a ubiquitous part of school that it’s considered radical to even suggest that lessening it could be good teaching. It’s completely normal for families to spend extra hours each night, even on weekends, completing projects, reports, and worksheets. On average, teenagers spend about an hour a day completing homework, which is up 30-45 minutes from decades past. Kindergartners, who are usually saved from completing a lot of after school work, average about 25 minutes of homework a night (which to note, is 25 minutes too much than is recommended by child development experts).

The “10-minute rule”, endorsed by the National Parent Teacher Association and National Education Association, is incorporated into most school policies: there’s 10 minutes of homework per day per grade level – as in 20 minutes a day in second grade or 2 hours a day in 12th grade.

It’s so normalized that it was odd, when seemingly out of nowhere the President of Ireland recently suggested that homework should be banned . (And many experts were shocked at this suggestion.)

Numerous studies on homework reflect inconsistent results on what it exactly achieves. Homework is rarely shown to have any impact on achievement, whether that be measured through standardized testing or otherwise. As I’ll talk about later, the amount of marginal gains homework may lead to aren’t worth its negative trade-offs.

Let’s look at a quick summary of various studies:

- First off, the book National Differences, Global Similarities: World Culture and the Future of Schooling by David P. Baker and Gerald K. LeTendre draws on a 4 year investigation of schools in 47 countries. It’s the largest study of its type: looking at how schools operate, their pedagogy, their procedures, and the like. They made a shocking discovery: countries that assigned the least amount of homework: Denmark and the Czech Republic, had much higher test scores than those who assigned the most amount of homework: Iran and Thailand. The same work indicated that there was no correlation between academic achievement and homework with elementary students, and any moderate positive correlation in middle or high school diminished as more and more homework was assigned.

- A study in Contemporary Educational Psychology of 28,051 high school seniors concluded that quality of instruction, motivation, and ability are all correlated to a student’s academic success. However, homework’s effectiveness was marginal or perhaps even counterproductive: leading to more academic problems than it hoped to solve.

- The Teachers College Record published that homework added academic pressure and societal stress to those already experiencing pressures from other forces at home. This caused a further divide in academic performance from those with more privileged backgrounds. We’ll talk about this more later.

- A study in the Journal of Educational Psychology examined 2,342 student attitudes toward homework in foreign language classes. They found that time spent on homework had a significant negative impact on grades and standardized test scores. The researchers concluded that this may be because participants had to spend their time completing worksheets rather than spend time practicing skills on their own time.

- Some studies are more positive. In fact, a meta-analysis of 32 homework studies in the Review of Educational Research found that most studies indicated a positive correlation between achievement and doing homework. However, the researchers noted that generally these studies made it hard to draw causal conclusions due to how they were set up and conducted. There was so much variance that it was difficult to make a claim one way or another, even though the net result seemed positive. This often cited report led by Dr. Harris Cooper at Duke University is the most commonly used by proponents of the practice. But popular education critic Alfie Kohn believes that this study fails to establish, ironically, causation among other factors.

- And that said in a later published study in The High School Journal , researchers concluded that in all homework assigned, there were only modest linkages to improved math and science standardized test scores, with no difference in other subjects between those who were assigned homework and those who were not. None of the homework assigned had any bearing on grades. The only difference was for a few points on those particular subject’s standardized test scores.

All in all, the data is relatively inconclusive. Some educational experts suggest that there should be hours of homework in high school, some homework in middle school, and none in elementary school. Some call for the 10-minute rule. Others say that homework doesn’t work at all. It’s still fairly unstudied how achievement is impacted as a result of homework. But as Alfie Kohn says , “The better the research, the less likely one is to find any benefits from homework.” That said, when we couple this data with the other negative impacts of assigning homework: how it impacts those at the margins, leads to anxiety and stress, and takes away from important family time – it really makes us question why this is such a ubiquitous practice.

Or as Etta Kralovec and John Buell write in The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning,

‘Extensive classroom research of ‘time on task’ and international comparisons of year-round time for study suggest that additional homework might promote U.S. students’ achievement.’ This written statement by some of the top professionals in the field of homework research raises some difficult questions. More homework might promote student achievement? Are all our blood, sweat, and tears at the kitchen table over homework based on something that merely might be true? Our belief in the value of homework is akin to faith. We assume that it fosters a love of learning, better study habits, improved attitudes toward school, and greater self-discipline; we believe that better teachers assign more homework and that one sign of a good school is a good, enforced homework policy.

Our obsession with homework is likely rooted in select studies that imply it leads to higher test scores. The authors continue by deciphering this phenomena:

“[this is] a problem that routinely bedevils all the sciences: the relationship between correlation and causality. If A and B happen simultaneously, we do not know whether A causes B or B causes A, or whether both phenomena occur casually together or are individually determined by another set of variables…Thus far, most studies in this area have amounted to little more than crude correlations that cannot justify the sweeping conclusions some have derived from them.”

Alfie Kohn adds that even the correlation between achievement and homework doesn’t really matter. Saying,

“If all you want is to cram kids’ heads with facts for tomorrow’s tests that they’re going to forget by next week, yeah, if you give them more time and make them do the cramming at night, that could raise the scores…But if you’re interested in kids who know how to think or enjoy learning, then homework isn’t merely ineffective, but counterproductive… The practice of homework assumes that only academic growth matters, to the point that having kids work on that most of the school day isn’t enough…”

Ramping Up Inequity

Many justify the practice of assigning homework with the well-intentioned belief that we’ll make a more equitable society through high standards. However, it seems to be that these practices actually add to inequity. “Rigorous” private and preparatory schools – whether they be “no excuses” charters in marginalized communities or “college ready” elite suburban institutions, are notorious for extreme levels of homework assignment. Yet, many progressive schools who focus on holistic learning and self-actualization assign no homework and achieve the same levels of college and career success.

Perhaps this is because the largest predictor of college success has nothing to do with rigorous preparation, and everything to do with family income levels. 77% of students from high income families graduated from a highly competitive college, whereas 9% of students from low income families did the same .

It seems like by loading students up with mountains of homework each night in an attempt to get them into these colleges, we actually make their chances of success worse .

When assigning homework, it is common practice to recommend that families provide a quiet, well-lit place for the child to study. After all, it’s often difficult to complete assignments after a long day. Having this space, time, and energy must always be considered in the context of the family’s education, income, available time, and job security. For many people, jobs have become less secure and less well paid over the course of the last two decades.

In a United States context, we work the longest hours of any nation . Individuals in 2006 worked 11 hours longer than their counterparts in 1979. In 2020, 70% of children lived in households where both parents work. We are the only country in the industrial world without guaranteed family leave. And the results are staggering: 90% of women and 95% of men report work-family conflict . According to the Center for American Progress , “the United States today has the most family-hostile public policy in the developed world due to a long-standing political impasse.”

As a result, parents have much less time to connect with their children. This is not a call to a return to traditional family roles or to have stay-at-home parents – rather, our occupation-oriented society is structured inadequately which causes problems with how homework is meant to function.

For those who work in entry level positions, such as customer service and cashiers, there is an average 240% turnover per year due to lack of pay, poor conditions, work-life balance, and mismanagement. Family incomes continue to decline for lower- and middle-class Americans, leaving more families to work increased hours or multiple jobs. In other words, families, especially poor families, have less opportunities to spend time with their children, let alone foster academic “gains” via homework.

Even for students with ample resources who attend “elite schools”, the amount of homework is stressful. In a 2013 study in The Journal of Experiential Education, researchers conducted a survey of 4,317 students in 10 high-performing upper middle class high schools. These students had an average of more than 3 hours of homework a night. In comparison to their peers, they had more academic stress, notable physical health problems, and spent a worrying amount of time focused entirely on school and nothing else. Competitive advantage came at the cost of well-being and just being a kid.

A similar study in Frontiers of Psychology found that students pressured in the competitive college admissions process , who attended schools assigning hours of homework each night and promoting college-level courses and resume building extracurriculars, felt extreme stress. Two-thirds of the surveyed students reported turning to alcohol and drugs to cope.

In fact, a paper published by Dr. Suniya Luthar and her colleagues concluded that upper middle-class youth are actually more likely to be troubled than their middle class peers . There is an extreme problem with academic stress, where young people are engaging in a rat race toward the best possible educational future as determined by Ivy League colleges and scholarships. To add fuel to the fire, schools continue to add more and more homework to have students get ahead – which has a massively negative impact on both ends of the economic spectrum.

A 2012 study by Dr. Jonathan Daw indicated that their results,

“...imply that increases in the amount of homework assigned may increase the socioeconomic achievement gap in math, science, and reading in secondary school.”

In an effort to increase engagement with homework, teachers have been encouraged to create interesting, creative assignments. In fact, most researchers seem to agree that the quality of assignments matters a whole lot . After all, maybe assigning all of this homework won’t matter as long as it’s interesting and relevant to students? Although this has good intentions, rigorous homework with increased complexity places more impetus on parents. As researcher and author Gary Natrillo, an initial proponent of creative homework , stated later:

…not only was homework being assigned as suggested by all the ‘experts,’ but the teacher was obviously taking the homework seriously, making it challenging instead of routine and checking it each day and giving feedback. We were enveloped by the nightmare of near total implementation of the reform recommendations pertaining to homework…More creative homework tasks are a mixed blessing on the receiving end. On the one hand, they, of course, lead to higher engagement and interest for children and their parents. On the other hand, they require one to be well rested, a special condition of mind not often available to working parents…

Time is a luxury to most people. With increased working hours, in conjunction with extreme levels of stress, many people don’t have the necessary mindset to adequately supply children with the attention to detail for complex homework. As Kralovec and Buell state,

To put it plainly, I have discovered that after a day at work, the commute home, dinner preparations, and the prospect of baths, goodnight stories, and my own work ahead, there comes a time beyond which I cannot sustain my enthusiasm for the math brain teaser or the creative story task.

Americans are some of the most stressed people in the world. Mass shootings, health care affordability, discrimination, racism, sexual harassment, climate change, the presidential elections, and literally: staying informed on current events have caused roughly 70% of people to report moderate or extreme stress , with increased rates for people of color, LGBTQIA Americans, and other discriminated groups. 90% of high schoolers and college students report moderate or higher stress, with half reporting depression and a lack of energy and motivation .

In 2015, 1,100 parents were surveyed on the impact of homework on family life. Fights over homework were 200% more likely in families where parents didn’t have a college degree. Generally, these families believed that if their children didn’t understand a homework assignment then they must have been not paying attention at school. This led to young people feeling dumb or upset, and parents feeling like their child was lying or goofing off. The lead researcher noted,

All of our results indicate that homework as it is now being assigned discriminates against children whose parents don’t have a college degree, against parents who have English as a second language, against, essentially, parents who are poor.

Schooling is so integrated into family life that a group of researchers noted that “...homework tended to recreate the problems of school, such as status degradation.” An online survey of over 2,000 students and families found that 90% of students reported additional stress from homework, and 40% of families saw it as nothing more than busy work. Authors Sara Bennett and Nancy Kalish wrote the aptly titled The Case Against Homework which conducted interviews across the mid-2000s with families and children, citing just how many people are burdened with overscheduling homework featuring over-the-top assignments and constant work. One parent remarked,

I sit on Amy's bed until 11 p.m. quizzing her, knowing she's never going to use this later, and it feels like abuse," says Nina of Menlo Park, California, whose eleven-year-old goes to a Blue Ribbon public school and does at least three-and-a-half hours of homework each night. Nina also questions the amount of time spent on "creative" projects. "Amy had to visit the Mission in San Francisco and then make a model of it out of cardboard, penne pasta, and paint. But what was she supposed to be learning from this? All my daughter will remember is how tense we were in the garage making this thing. Then when she handed it in, the teacher dropped it and all the penne pasta flew off." These days, says Nina, "Amy's attitude about school has really soured." Nina's has, too. "Everything is an emergency and you feel like you're always at battle stations."