Nissim Ezekiel (1924-2004) | Graziano Krätli

Home » Nissim Ezekiel (1924-2004) | Graziano Krätli

MLA: Krätli, Graziano, “Nissim Ezekiel (1924-2004).” Indian Writing In English Online , 26 Dec 2022, indianwritinginenglish.uohyd.ac.in/ezekiel-bio/ .

Chicago: Krätli, Graziano, “Nissim Ezekiel (1924-2004).” Indian Writing In English Online. December 26, 2022. indianwritinginenglish.uohyd.ac.in/ezekiel-bio/ .

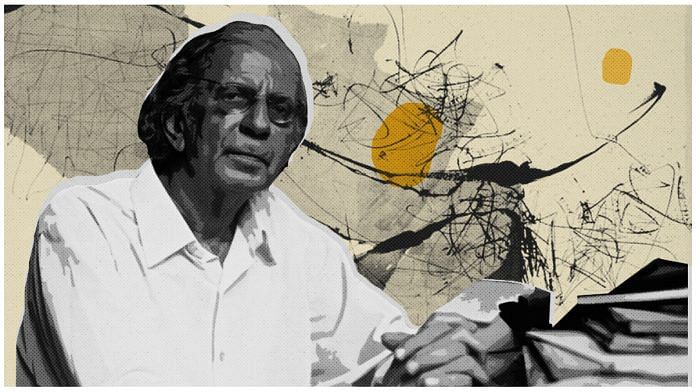

For more than three decades, from the early 1960s until the mid-1990s, Nissim Ezekiel was a pivotal figure in the cultural life of Bombay/Mumbai, as his work as poet, editor, critic, and teacher influenced and inspired younger writers and artists, helping shape the canon of Indian poetry in English along the way.

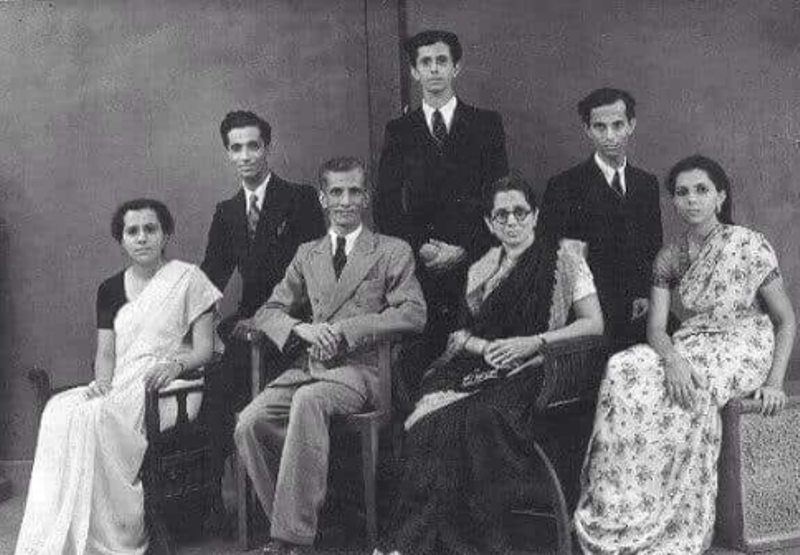

Born on December 16, 1924, in Bombay, Nissim was the third of five children, three boys and two girls. His parents, Diana and Moses Ezekiel Talkar, were both members of the Bene Israel (“Children of Israel”), the oldest and largest of the three Jewish communities in India. They were also part of the first generation who moved to the city from their ancestral homeland near Alibag, in the coastal region south of Mumbai. (Talkar, the additional toponymic which Moses Ezekiel added to, and eventually dropped from, his surname, refers to the native village of Tar, in the Raigad district). Both parents were teachers: Moses a lecturer in Botany and Zoology at Wilson College, and Diana a schoolteacher before starting her own nursery school. Liberal and progressive in their religious beliefs and practices, they held evening prayers (in Hebrew or English) and visited the synagogue on Yom Kippur. At home they spoke Marathi, a language Nissim never mastered enough to be able to write poetry in it, as some of his Maharashtrian contemporaries, such as Arun Kolatkar (1932‒2004) and Dilip Chitre (1938‒2009), did. (His only book of translations of Marathi poetry was done in collaboration with a university colleague.) Nissim’s formal education started at the Convent of Jesus and Mary, continued at the Antonio De Souza High School (both Roman Catholic), and was capped with a bachelor’s (1945) followed by a master’s (1947) in English Literature at Wilson College. Around this time, he published his first poems in the college magazine and elsewhere. After graduation, he taught for a year at Khalsa College, freelanced for various newspapers and magazines, and worked for M.N. Roy’s Radical Democratic Party, eventually distancing himself from politics to focus on poetry and the arts. The change was partly due to the influence of a new friend, Ebrahim Alkazi, a student at St. Xavier’s College and a member of Sultan Padamsee’s Theatre Group. Upon graduation, Alkazi decided to continue his studies at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA) in London, and convinced Nissim to join him by offering to pay his fare.

In London, where he arrived in November 1948, Nissim spent much of his time reading in the library of India House, the headquarters of India’s diplomatic mission to the United Kingdom, until the High Commissioner, V.K. Krishna Menon (a close friend of Nehru and a future Union Minister for Defence), offered him a job in the Internal Affairs Department. At the same time, Nissim enrolled in evening courses (Chinese, Western Philosophy, Art Appreciation, etc.) at the City Literary Institute, an adult education college nearby, and attended philosophy classes at Birkbeck College, University of London, without completing the BA program. A couple of visits to Paris, in late December 1949 and August 1951, resulted in a strong desire to move there. (Incidentally, Srinivas Rayaprol, an almost contemporary of Ezekiel, had the same impulse after visiting the City of Light in 1951, following a three-year residence in the United States. We may wonder whether either of them would have been a different poet, or a different author altogether, had he followed this impulse and settled in the French capital. (Just like we may wonder what kind of poet and scholar would have been Ramanujan, had he pursued his academic career at Cambridge or Oxford rather than Chicago; or what would have become of Dom Moraes, as a poet and journalist, had ne never left India). But we can only speculate. What we know is that, early on, London brought out Ezekiel’s vocation to be a poet, and he acted upon it with determination and perseverance. After one year at India House, he quit his job to devote all his time to reading and writing, living frugally and supporting himself with menial jobs and money occasionally sent from home. As he would characterize this period in “Background, Casually,” one of his most autobiographical (and anthologized) poems, “Philosophy, / Poverty and Poetry, three / Companions shared my basement room”. The result of this self-imposed, creative confinement was a manuscript which Reginald Ashley Caton, founder of the Fortune Press, accepted for a ten-pound publishing fee. (The house had previously published other South Asian poets living in England, among them Fredoon Kabraji and M.J. Tambimuttu, as well as British and American authors such as Kingsley Amis, Cecil-Day Lewis, Philip Larkin, Dylan Thomas, Wallace Stevens, and Robert Penn Warren, in addition to French, Greek, and Latin classics). Ezekiel then turned his efforts to planning his trip back to India, and eventually found a way to pay his fare by working on a cargo ship that was carrying ammunition to French Indo-China. The return trip took more than two months, from March to May 1952, as the ship made several stops; but at one of them, in Marseilles, the impromptu deckhand found copies of A Time to Change waiting for him.

Soon after his arrival in Bombay, Ezekiel was offered a job as sub-editor for The Illustrated Weekly of India . In the same year, he also began a long association with the P.E.N. All-India Centre and its founder, the Colombian-born Indian theosophist Sophia Wadia, initially assisting with the editing of The Indian P.E.N. and The Aryan Path , then, after Wadia’s death in 1986, editing the former newsletter and running the Centre from its offices in Theosophy Hall, Churchgate, a dual position he held until his failing health forced him to quit in 1998. As pointed out by one scholar, it was Ezekiel’s influence that eventually “helped transform the PEN All-India Centre from a formal institution which functioned primarily as a mediator, into a more flexible meeting place for new and established poets” (Bird 213). Before the year ended, Ezekiel married a member of the Bene Israel community, Daisy Jacob Dandekar. The couple will have two daughters (Kalpana and Kavita) and one son (Elkana). In May 1954, Ezekiel resigned from the Weekly to work for the Shilpi advertising agency, first as copywriter and then in a managerial position that allowed him to spend six months in New York for professional development. This gave him the opportunity to visit California and to attend poetry readings and other cultural events in San Francisco and Los Angeles. (Although the 1956 poetry scene in the Bay Area did not impress him as much as it did Rayaprol, who had experienced it only a few years before while a student at Stanford University.)

Not long after this trip, Ezekiel left Shilpi for a job at the Chemould Frames company, where his duties as factory manager did not prevent him from developing a lasting relationship with his employer, the art entrepreneur Kekoo Gandhy. This helped the young poet and critic to expand his links to the Bombay art world, and in turn prompted Gandhy to open Gallery Chemould in 1963, one of only two commercial galleries at the time, which Ezekiel would manage for a while.

With his appointment as lecturer and head of the English Department at Mithibai College, in 1961, Ezekiel eventually settled in the teaching profession of his parents, thus embarking on an academic career that would continue at the University of Bombay and include visiting professorships at the University of Leeds (1964) and the University of Chicago (1967), and a three-month residency at the National University of Singapore (1988‒89). However, if teaching represented the backbone of Ezekiel’s professional life for two decades and a half, it was through the correlated activities of literary editor, critic, book reviewer, and cultural organizer that the he acquired the reputation and exercised the influence which would grant him a foundational (if not patriarchal) status within the canon of postcolonial Indian poetry in English.

Sometime in the early 1950s, Ezekiel became involved with the Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom (ICCF), an affiliate of the Committee for Cultural Freedom (CCF), whose various activities, focused on literature and the arts (and secretly funded by the CIA), were meant to counter Soviet influence in western Europe, Africa and Asia. In India, two of the initiatives sponsored by the ICCF were the monthly newsletter Freedom First (1952‒2015) and the bi-monthly of arts and ideas Quest (1955‒76). Ezekiel was the first editor of Quest (August 1955‒February 1958) and subsequently served as its reviews editor (1961‒67). He also contributed articles and book reviews to both publications, and in 1980‒83 served as editor of Freedom First , his focus then being on current events and political issues, consistent with the ideology of the journal. (Another Bombay periodical funded—in this case directly—by the CIA was Imprint, which published mainly condensed versions of Western bestsellers. Run by a couple of American expatriates, it was edited by the Australian journalist Philip Knightley with Ezekiel as associate editor from 1961‒67.) Under Ezekiel’s editorship, Quest was a significant venue for the new poetry, publishing such emerging authors as Kersey Katrak, Arun Kolatkar, Dom Moraes, R. Parthasarathy, Gieve Patel, Srinivas Rayaprol and others, and paving the way for the special issue on contemporary Indian poetry in English (January‒February 1972), guest edited by Saleem Peeradina and subsequently published as a book, which was one of the earliest and remains one of the most influential postcolonial anthologies of its kind. Even more innovative, if short-lived, was the quarterly Poetry India , which featured poems written in English or translated from the main regional languages, plus an international section represented by British and North American authors (but also including translations from the Hebrew). Ezekiel edited all six issues (January‒March 1966 through April‒June 1967), and, with the second, took over the ownership and management of the publication from the Bombay-based Parichay Trust (The original plan included a series of books, but the only one which Ezekiel was able to publish, under his own name, was Gieve Patel’s first collection, Poems , in 1966).

A few years later, the model adopted by Ezekiel in Poetry India (in which English served as both creative and target language) inspired another little magazine, Vagartha , founded and edited by the scholar Meenakshi Mukherjee with the financial support of the Joshi Foundation. In the course of twenty-five quarterly issues published over six years (1973‒79), Vagartha featured contemporary poetry as well as short fiction, critical essays, discussions and interviews, either in English or translated from other Indian languages, namely Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Marathi, Malayalam, Oriya, Punjabi and Urdu. Ezekiel contributed a total of six poems (five of his and one translated from the Marathi with Vrinda Nabar), as well as the translator’s note to Snake-skin and Other Poems of Indira Sant (1975). A decade after the magazine closed down, Ezekiel was behind the idea of “[p]reserving the best of Vagartha in book form” (Ezekiel and Mukherjee, 13), which resulted in Another India: An Anthology of Contemporary Indian Fiction and Poetry (1990), co-edited with Mukherjee (ironically, the title was suggested to Mukherjee by Naipaul, during a “casual encounter” in Delhi in early 1989).

Overall, the 1960s were Ezekiel’s most productive decade. In addition to his academic and editorial responsibilities, his art and literary criticism for various publications, and his involvement in conferences and seminars (especially those organized by P.E.N. India and the ICCF), he managed to publish two collections of poetry ( The Unfinished Man, 1960, and The Exact Name , 1965) and one of plays ( Three Plays , 1969), in addition to five edited books: Indian Writers in Conference: Proceedings of the Sixth P.E.N. All-India Writers’ Conference, Mysore, 1962 (1964), Writing in India: Proceedings of the Seventh P.E.N. All-India Writers’ Conference, Lucknow, 1964 (1965), An Emerson Reader (1965), A Martin Luther King Reader (1969), and Poetry from India (co-edited with Howard Sergeant, 1970).

In 1972 Ezekiel joined the English Department at the University of Bombay as reader in American Literature, a position he held until his retirement in 1984. The subject was as new to the Indian universities as the Poet was new to the subject, but his appointment, like his rapid promotion to the rank of full professor, disregarded his lack of a doctoral degree or other scholarly credentials and considered instead his reputation as a poet and critic, his recent volumes on Emerson and Dr. King, and his visits to the United States, especially the second, in 1967, when among other things he was invited to give a talk at the Thoreau Festival at Nassau Community College, in Garden City, New York. Another significant change, and a step forward in the process of canonization, was Ezekiel’s moving from Writers Workshop (recently founded by the poet, critic and translator P. Lal, who had been one of the first reviewers of A Time to Change ) to the more established and prestigious (as a colonial legacy) Oxford University Press , which would publish his next four books, namely the poetry collections Hymns in Darkness (1976) and Latter-Day Psalms (1982), a volume of Collected Poems: 1952-1988 (1989), and one of Selected Prose (1992). The first two books appeared in the New Poetry in India series, launched in 1976 and also featuring Keki Daruwalla’s Crossing of Rivers , Shiv K. Kumar’s Subterfuges , R. Parthasarathy’s Rough Passage , A.K. Ramanujan’s Selected Poems , and Parthasarathy’s anthology, Ten Twentieth-Century Indian Poets . (Parthasarathy, in his role as OUP editor, was probably the link between his former colleague at Mithibai College and the publisher). Ezekiel’s growing reputation as the standard-bearer for Indian poetry in English is further evidenced by the frequent interviews he gave to literary journals and popular magazines (making him probably the most interviewed poet in the canon); by the many lecture tours and conference he attended over the next two decades, both in India and abroad; by his editorial consultancies for publishers and poetry series; by the Sahitya Akademi Award (1983) for Latter-Day Psalms and the Padma Shri (1988) for his contribution to Indian literature in English; and by the growing number of periodical issues ( Journal of South Asian Literature 1976, The Journal of Indian Writing in English 1986) and monographs (Karnani 1974, Rahman 1981, Raizada 1992, Das 1995, Sharma 1995, etc.) devoted to him.

In Modern Indian Poetry in English (1987), the first comprehensive and detailed overview of the field, the American scholar Bruce King presented Ezekiel as a watershed in the evolution of Indian poetry in English; the poet who “brought a sense of discipline, self-criticism and mastery to Indian English poetry”, separating poetry as a “hobby, something done in spare moments” from poetry as a vocation, to be pursued with “craftsmanship and purposefulness”. In King’s lapidary statement, “Other wrote poems, he wrote poetry” (91). A few years later, King included Dom Moraes and A.K. Ramanujan in his study of the Three Indian Poets (1991) who “may be considered the founders of modern poetry in English” (2005, 1). A genealogy was thus created, with Ezekiel as the oldest of the three, as well as the one with the longest and strongest connection to India. (Moraes, it should be remembered, first acquired literary fame in England and was considered a British poet until he returned to India, as a “stranger”, in the 1970s; while Ramanujan lived in the United States since the 1960s).

But canonization is a double-edged sword, and by the early 1990s Ezekiel’s stature as the founding father and doyen of Indian poetry in English was being questioned and scaled back, as some anthologists (Vilas Sarang and Arvind Krishna Mehrotra in particular) expressed reservations about his achievement. Likewise, his critical authority and judgment came occasionally under scrutiny when, as a consultant, his advice resulted in the publication of some younger poets to the exclusion of others; or also in relation to the ban imposed on Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in India (1988) and Taslima Nasrin’s Lajja in Bangladesh (1994), decisions which Ezekiel supported (as did the Indian P.E.N. and many other Indian intellectuals and writers).

While continuing to publish articles and book reviews, and to write poetry (often in response to requests from magazine editors, and as yet uncollected), most if not all of this late work is more a testimony to Ezekiel’s reputation and influence than a proof of his enduring strength and relevance as a poet or critic.

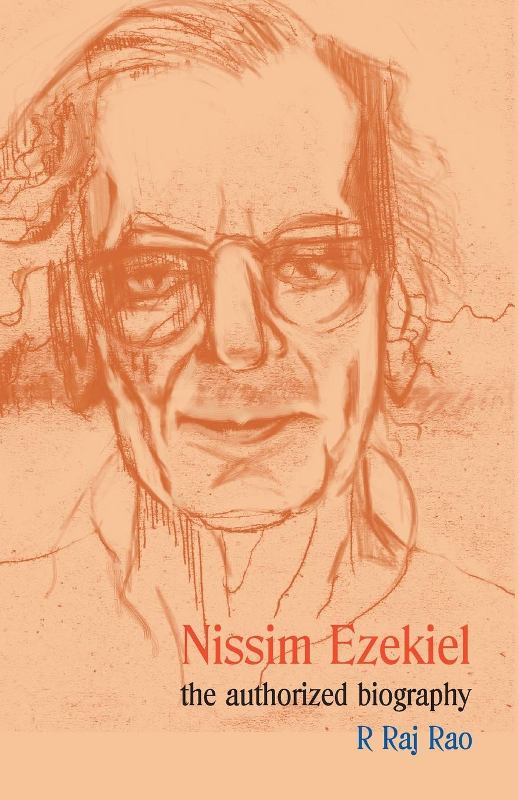

During the four-year period (1994‒98) when the writer and academic R. Raj Rao (a former student of Ezekiel’s at the University of Bombay) met regularly with him to gather information for an authorized biography, the poet’s memory and living conditions progressively deteriorated, until he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and admitted to a nursing home, where he died on 9 January 2004. His passing marked the beginning of what has been called the annus horribilis of Indian poetry in English, which also claimed the lives of Moraes and Kolatkar, on June 2 nd and September 25 th , respectively.

Spanning more than four decades, Ezekiel’s eight poetry collections represent a remarkable achievement per se, let alone when considered along with the poet’s concomitant activities as teacher and mentor, editor, reviewer, cultural organizer and public intellectual at large.

If A Time to Change passed virtually unnoticed in England, in India the reviews were more than a few and generally appreciative. Not surprisingly, the twenty-eight-year old’s inquiring, self-analytical and quintessentially urban poetic persona, combined with a conscious disregard for the nationalistic, spiritualistic, or folkloric themes characteristic of most Indian poetry written before and after the Independence (most notably by such prominent figures as Sarojini Naidu and Sri Aurobindo), and a corresponding indifference to India’s past or present history, archeological landscape, and current events appealed immediately to a younger generation of urban, college educated, anglophone readers and emerging writers, some of whom were about to study abroad themselves (Jussawalla, Moraes, Ramanujan), or had recently returned (Rayaprol), while others simply shared Ezekiel’s connection to Bombay’s vibrant cultural scene (Eunice de Souza, Katrak, Kolatkar, Patel, etc.). The book begins with a secular hymn and ends with five examples of prose poetry (a genre which Ezekiel, regrettably, did not follow up), their increasingly religious overtones culminating in the visionary call of “Encounter” (“Within the pandemonium of the street I felt his voice, like a command”). The voice’s imperative advice (to “Simplify,” to “Move in living images”) provides a programmatic answer to the question raised at the beginning, in the Eliotian call for renewal, regeneration and redemption: “How shall we return?” The introspective, questioning approach of “A Time to Change”, and its underlying preoccupation with the conflict between reason and emotion (the “passion of mind or heart”, in which the intellect struggles to comprehend and therefore control the relentless power of bodily desires), set the tone for the entire book and, to some extent, define Ezekiel’s poetic quest throughout his career. If this quest has a religious dimension, it is initially the modern man’s coming to terms with a state of godlessness, and the consequent need—liberating and terrifying at the same time—to make his own laws and fashion his own creed. (A patent masculine attitude toward religion, rooted in the Old Testament and defined by oedipal impulses and anxiety). The title poem provides a crescendo of Ezekiel’s concerns: “The pure invention or the perfect poem, / Precise communication of a thought, / Love reciprocated to a quiver, / Flawless doctrines, certainty of God” (the word “god”, either capitalized or not, singular or plural, recurs eighteen times in the thirty-one poems that make up A Time to Change ), ending with a realization that is also a course of action (“These are merely dreams; but I am human / And must testify to what they mean”). Not to discard or disregard these “dreams” but “testify to what they mean” (that is, to use them as evidence of their fallacy); and not a mere possibility but the only possible way, which for a poet means “To own a singing voice and a talking voice”. This double ownership (involving technical mastership as well as control over its results) is indeed what makes a poet and defines his art and belief; therefore “Practising a singing and a talking voice / Is all the creed a man of God requires”—a simple yet genuine profession of faith that simultaneously prefigures Ezekiel’s career as poet and critic.

Life in the English metropolis helped Ezekiel view his hometown of Bombay as a metropolitan space to be lived, experienced and described not only as a physical and social environment, made of “markets and courts of justice, / Slums, football grounds, entertainment halls, / Residential flats, palaces of art and business houses, / Harlots, basement poets, princes and fools” (“Something to Pursue”), but also as a projection and a reflection of the poet’s Geistesleben , or life of the mind. As such, it may be alternately oppressive, menacing, unnerving, enticing or liberating. It may combine the sense of being “continually/ Reduced to something less than human by the crowd” (“The Double Horror”) with the contrasting feelings (desire and deceit, excitement and dissatisfaction) that are the inevitable outcome of clandestine love affairs for which a big city, with its variety of anonymous public spaces, provides an opportunity as well as a backdrop. The “primeval jungle” evoked in the ekphrastic “On an African Mask” becomes the metaphoric urban jungle of poems such as “The Double Horror” and “Commitment”, where the strong imagery seems to draw on German Expressionist cinema, as

vast organised

Futilities suck the marrow from my bones

And put a fever there for cash and fame.

Huge posters dwarf my thoughts, I am reduced

To appetites and godlessness. I wear

A human face but prowl about the streets

Of towns with murderous claws and anxious ears,

Recognising all the jungle sounds of fear

And hunger, wise in tracking down my prey

And wise in taking refuge when the stronger roam.

(“Commitment”)

One of the distinguishing features of A Time to Change (and most of Ezekiel’s poetry until the mid 1960s) is a formal awareness that manifests itself in the consistent (and occasionally self-conscious) adherence to simple metrical structures. It features both stanzaic and free verse poems (the former typically consisting of three or four heroic quatrains rhyming ABAB, with variants made of seven or ten unrhymed lines each); and while it stands in obvious contrast to the recycled Victorian and Edwardian models of Ezekiel’s predecessors (and some of his lesser contemporaries), its actual achievement is rather more conservative (and subtly bifronted) than most critical assessments, focused as they are on the break with the past, seem prepared or willing to admit.

Ezekiel’s second collection is titled Sixty Poems (1953), but actually consists of sixty-five: nineteen written since the publication of A Time to Change , thirty-seven dating from the London years (1950‒51), and nine from the period immediately before (1945‒48), starting when Ezekiel was a graduate student at Wilson College. This was followed by The Third (1959), featuring thirty-six poems written over five years (January 1954‒December 1958) and showing a crystallized emphasis on the poet’s main subject so far, namely a sustained effort to scrutinize, analyze, and rationalize his own self from different angles, perspectives and grammatical persons (first as well as second or third). This may be challenging, daunting, intimidating, as the poet himself admits, confessionally, in “What Frightens Me”.

Myself examined frightens me.

I have long watched myself

Remotely doing what I had to do,

At times ashamed but always

Rationalising all I do.

I have heard the endless silent dialogue

Between the self-protective self

And the self naked.

I have seen the mask

And the secret behind the mask.

Subtly undermined by the ambiguity of “remotely” (does it refer to “watched” or “doing”?), as well as deflated by the hyperbolic “always rationalising all I do”, this self-awareness exercise ultimately leads to the disconcerting realization that the process of identity construction (the “image being formed”) has uncertainty as its end result. Thus the self is always, inevitably (but also salvifically) both a project and a projection of its own self.

If the three collections published in the 1950s document Ezekiel’s poetic development and growing influence, the next two represent the culmination of such a progress, resulting in the establishment of a solid reputation as the foremost representative of the “new poetry” in India.

The Unfinished Man was inscribed with a stanza from “A Dialogue of Self and Soul” by W.B. Yeats (one of Ezekiel’s early influences) and consists of ten poems written in 1959; while The Exact Name (1965) bears an epigraph from the Spanish poet (and recent Nobel Prize winner) Juan Ramón Jiménez, and features twenty poems written between 1960 and 1964. Thematically, they represent a broadening and sharpening of ongoing or lingering concerns, articulated in a style that is more accomplished and self-confident, but also less spontaneous and more controlled by metrical patterns that are responsible for the overall rhythmic regularity, mannered elegance and emotional detachment of the collection.

The “barbaric city sick with slums”, with its “million purgatorial lanes, / And child-like masses, many-tongued”, may still be grim and overwhelming, but instead of a nightmare it manifests itself as an “old, recurring dream” (“A Morning Walk”, from The Unfinished Man ), or a daydream in which the poet indulges as he “moves / In circles tracked within his head” and

dreams of morning walks, alone,

And floating on a wave of sand.

But still his mind its traffic turns

Away from beach and tree and stone

To kindred clamour close at hand.

(“Urban”, from The Unfinished Man )

In either case, it is a less threatening and more accommodating environment, and one that points to a future gesture of acceptance and reconciliation. The Exact Name features some of Ezekiel’s most anthologized and critically discussed poems, most notably “The Night of the Scorpion” and “Poet, Lover, Birdwatcher”, but also a few lesser results (“In India”, “Fruit”, “Art Lecture”), and at least one (“Conjugation”) that reads more like an impromptu exercise than anything worthy of publication.

Eventually the watcher and the watched (whose interplay defines much of Ezekiel’s self-analytical verse up to this point) merge in one poetic voice in the more spontaneous and straightforward poems written in the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, which in Collected Poems form two sections, “Poems (1965‒1974)” and “Poems Written in 1974”, placed between The Exact Name (1965) and Hymns in Darkness (1976). They are marked by a more direct and confrontational approach to religion, as in “Theological” (“Lord, I am tired / of being wrong … Your truth / is too momentous for man / and not always useful”), but also a more confident and questionable display of sexist attitudes (“My motives are sexual, / aesthetic and friendly / in that order”, from “Motives”), while the unprecedented attention to the lower strata of society (“The Truth about Dhanya”) lacks either empathy or originality. Formally, they show a preference for free verse and, with “The Poet Contemplates His Inaction”, the introduction of the three-line stanza that will characterize much of Ezekiel’s later poetry.

Hymns in Darkness gathers twenty-seven poems written mostly in the early 1970s, including a few that are among the poet’s most significant and popular. Early on in the book, “Background, Casually” and “Island” (respectively Ezekiel’s most directly autobiographical poem and his most eloquent poetic transfiguration of Bombay) stand next to each other to stress a double commitment—“to stay where I am” and to be where I stay (or we could say, more existentially, where I dwell ). The background of the title finds a more eloquent and ironic expression in the poet’s admission to “have become a part of [the Indian landscape] / To be observed by foreigners” (like a monument as well as a result of literary canonization). As for the background itself, “Unsuitable for song as well as sense” (a tongue-in-cheek statement, which the poem vividly contradicts), “the island flowers into slums / and skyscrapers, reflecting / precisely the growth of my mind. / I am here to find my way in it”. Thus Ezekiel renews his commitment to both, his birthplace (“I cannot leave the island, / I was born here and belong”) and reason as a way to navigate and find one’s bearings in both, urban sprawl and mind growth.

Overall, Indian subjects are more prominent and diverse in this than in Ezekiel’s previous collections. The often-quoted “Goodbye Party for Miss Pushpa T. S.” and “The Railway Clerk” provide a first taste of an ongoing series called “Very Indian Poems in Indian English”, whose main goal is to render the peculiarities of a demotic idiom that, typically (and perhaps inevitably), has more potential and opportunities in fiction than in poetry. “The Truth about the Floods” and “Rural Suite” are unprecedented excursions in the countryside, the former a found poem based on a newspaper account, the latter apparently derived from a letter; “Guru” and “Entertainment” offer disillusioned portraits of spiritual leadership and street life; while “Ganga” conveys the truth about domestic employment in a way than “The Truth about Dhanya” had not cared to do (to the extent that the closing line, “These people never learn”, may refer to the employee or the employers—or both). A different, more subtle Indian thread running through this collection is represented by Ezekiel’s dialogue with the country’s Vedic and classical Sanskrit literature, as documented by such poems as “Tribute to the Upanishads ”, the nine “Poster Poems” (based on Daniel H. H. Ingalls’ 1965 translation of Vidyākara’s Subhā ṣ itaratnako ṣ a , a major compilation of Sanskrit love poetry), and especially the sixteen “Hymns in Darkness”, inspired by the Vedic hymns which Ezekiel read, in English translation, in a darkened room of his apartment on Bellasis Road (King 55).

The “Very Indian Poems in Indian English” and the “Poster Poems”, like “The Egoist’s Prayers”, the “Passion Poems”, the “Songs for Nandu Bhende”, the“Postcard Poems”, “Nudes 1978”, “Blessings”, and “Edinburgh Interlude”, are groups of poems which Ezekiel started writing in the 1970s and included, partially, in Hymns in Darkness, Latter-Day Psalms and the final section of Collected Poems, featuring poems from 1983–1988. The “Poster Poems”, “The Egoist’s Prayers” and the “Passion Poems” were originally exhibited on posters, while the “Songs for Nandu Bhende” were written for, and set to music by, Ezekiel’s nephew, resulting in an album the two co-produced. Altogether, these groups of poems are representative of Ezekiel’s later poetry, characterized by a more consistent use of free verse and condensed forms, such as hymnic or aphoristic utterances, often delivered in brief stanzas of variable length. This original style, combining a dialogic approach with an exegetic impulse, has a precedent in “For William Carlos Williams” and a more recent (and complex) manifestation in “Tribute to the Upanishads ”; but its most substantial and ambitious formulation is to be found in “Hymns in Darkness” and “Latter-Day Psalms”, each representing Ezekiel’s poetic response to a major text in Hinduism and Judaism, the two religions that are closest to his Indian background and his Jewish ancestry, respectively. Written in June 1978 in a hotel room in Rotterdam, the “Latter-Day Psalms” consist of nine poems corresponding to Psalms 1, 3, 8, 23, 60, 78, 95, 102 and 127 (and “chosen as representative of the 150 Psalms”), followed by a personal commentary on the book as a whole. (Incidentally, the same, nine-plus-one structure reappears in the “Ten Poems in the Greek Anthology Mode,” written between 1983 and 1988 and included in the final section of Collected Poems ).

Inevitably, Ezekiel’s poetry and reputation as a poet have somehow detracted scholarly and critical attention from his prose. Although some articles (most notably “Naipaul’s India and Mine” and “Poetry as Knowledge”) have been reprinted more than once, at the time of this writing (2022) Ezekiel’s journalistic work can be sampled in Adil Jussawalla’s 1992 selection and in the 2008 commemorative volume Nissim Ezekiel Remembered. Together, they provide a representative and eloquent if partial view of the poet’s achievement as public intellectual, book reviewer, art critic, editorialist, and newspaper columnist. Indeed, his critical spectrum and adaptability were such that he wrote with equal comfort and acumen for highbrow journals such as Quest , its continuation New Quest , and Freedom First , but also for daily newspapers ( Times of India , Sunday Times ), and popular magazines ( Mid-Day ), while his contributions ranged from papers delivered at international conferences and seminars to art and literary criticism, and from reviews of books, exhibitions and theater productions to current events and politics, social commentary (e.g., the “Minding My Business” columns in the Sunday Times of 1980‒82) and even television programs (for The Times of India in the mid-1970s and for Mid-Day a decade later).

As a pathbreaking poet, mentor, editor and critic, Ezekiel played an important, indeed unique, role in the development of a canon for Indian poetry in English. No survey or assessment of the field would be complete without acknowledging his various and substantial contributions to it, just like no such acknowledgment would be fair which did not consider the particular, historical as well as geographical, extent and limitations of Ezekiel’s role and influence. While many Bombay poets who emerged in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s benefited from his mentoring skills, his editorial advice and his overall support, many others looked elsewhere for updated models: to American modernism, the Beat Generation or even more experimental forms such as concrete and minimalist poetry. The same historical perspective is necessary to properly appreciate Ezekiel’s own poetry, its formal adherence to pre- and post-World War Two British models (Yeats, Eliot, Auden, all the way to the Movement), its content-related concerns and its particular cultural context. It may also help explain and understand why Ezekiel’s poetry does not speak to Indian poets and readers today in the same way as does the poetry of some of his contemporaries, such as Arun Kolatkar, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra or A.K. Ramanujan, all of whom, unlike Ezekiel, have been the subject of recent and substantial international critical attention.

A Time to Change . London: Fortune Press, 1952.

Sixty Poems . Bombay: Ezekiel, 1953.

The Third . Bombay: Strand Bookshop, 1959.

The Unfinished Man . Calcutta: Writers Workshop, 1960.

The Exact Name . Calcutta: Writers Workshop, 1965.

Hymns in Darkness . New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Latter-Day Psalms . New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Collected Poems: 1952-1988 . Introduction by Gieve Patel. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1989 and 2005.

Selected Prose . Introduction by Adil Jussawalla. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Three Plays [ Nalini – Marriage Poem – The Sleepwalkers ]. Calcutta: Writers Workshop, 1969.

Song of Deprivation . Delhi: Enact, 1969.

Don ’t Call It Suicide: A Tragedy . Madras: Macmillan, 1993.

Translations

Snake-skin and Other Poems, s of Indira Sant . Translated from the Marathi by Vrinda Nabar and Nissim Ezekiel. Bombay: Nirmala Sadanand Publishers, 1975.

Edited Books

Indian Writers in Conference: Proceedings of the Sixth P.E.N. All-India Writers’ Conference, Mysore, 1962 . Bombay: PEN All-India Centre, 1964.

Writing in India: Proceedings of the Seventh P.E.N. All-India Writers’ Conference, Lucknow, 1964 . Bombay: PEN All-India Centre, 1965.

An Emerson Reader. Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1965.

A Martin Luther King Reader. Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1969.

Poetry from India . Edited by Nissim Ezekiel and Howard Sergeant. Oxford; New York: Pergamon, 1970.

Artists Today: East-West Visual Arts Encounter . Edited by Ursula Bickelmann and Nissim Ezekiel. Bombay: Marg Publications, 1987.

Another India: An Anthology of Contemporary Indian Fiction and Poetry . Edited by Nissim Ezekiel and Meenakshi Mukherjee. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1990.

Secondary Sources

Anklesaria, Havovi, ed. Nissim Ezekiel Remembered . New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2008.

Balarama Gupta, G.S. Nissim Ezekiel: A Critical Companion . New Delhi: Pencraft International, 2010.

Bharucha, Nilufer E., and Vrinda Nabar, eds. Mapping Cultural Spaces: Postcolonial Indian Literature in English: Essays in Honour of Nissim Ezekiel . New Delhi: Vision Books, 1998.

Bharvani, Shakuntala. Nissim Ezekiel . New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2008.

Bird, Emma. “A Platform for Poetry: The PEN All-India Centre and a Bombay Poetry Scene.” Journal of Postcolonial Writing, vol. 53, no. 1-2, 2017, pp. 207-220.

Chaudhuri, Amit. “Nissim Ezekiel: Poet of a Minor Literature.” A History of Indian Poetry in English , edited by Rosinka Chaudhuri, Cambridge University Press, 2016, pp. 205–22.

Chindhade, Shirish. Five Indian English Poets: Nissim Ezekiel, A.K. Ramanujan, Arun Kolatkar, Dilip Chitre, R. Parthasarathy . Atlantic, 1996.

Das, Bijay Kumar. The Horizon of Nissim Ezekiel’s Poetry . B.R. Publishing Corporation, 1995.

Dwivedi, Suresh Chandra, ed. Perspectives on Nissim Ezekiel: Essays in Honour of Rosemary C. Wilkinson . Kitab Mahal, 1989.

Karnani, Chetan. Nissim Ezekiel . New Delhi: Arnold-Heinemann, 1974.

King, Bruce. Modern Indian Poetry in English . Oxford University Press, 1987.

King, Bruce. Three Indian Poets: Ezekiel, Moraes, and Ramanujan . Delhi; Oxford University Press, 2005.

Krätli, Graziano. “Crossing Points and Connecting Lines: Nissim Ezekiel and Dom Moraes in Bombay and Beyond.” Journal of Postcolonial Writing, vol. 53, no. 1–2, March 4, 2017, pp. 176–89.

Kurup, P.K.J. Contemporary Indian Poetry in English: With Special Reference to the Poetry of Nissim Ezekiel, Kamala Das, A.K. Ramanujan, and R. Parthasarathy . Atlantic, 1991.

Mahan, Shaila. The Poetry of Nissim Ezekiel . Classic, 2001.

Mishra, Sanjit. The Poetic Art of Nissim Ezekiel . Atlantic, 2001.

Narendra Lall, Emmanuel. Poetry of Encounter: Three Indo-Anglian Poets . Sterling, 1983.

Raghu, A. The Poetry of Nissim Ezekiel. Atlantic, 2002.

Rahman, Anisur. Form and Value in the Poetry of Nissim Ezekiel . Abhinav, 1981.

Raizada, Harish. Nissim Ezekiel, Poet of Human Balance . Vimal Prakashan, 1992.

Rao, R. Raj. Nissim Ezekiel: The Authorized Biography . Viking/Penguin Books India, 2000.

Samal, Subrat Kumar. Postcoloniality and Indian English Poetry: A Study of the Poems of Nissim Ezekiel, Kamala Das, Jayanta Mahapatra and A.K. Ramanujan . Partridge, 2015.

Sharma, Tika Ram. Essays on Nissim Ezekiel . Shalabha Prakashan, 1995.

Talat, Qamar and A.A. Khan. Nissim Ezekiel: Poetry as Social Criticism . Adhyayan, 2009.

Thorat, Sandeep K. Indian Ethos and Culture in Nissim Ezekiel’s Poetry: A Critical Study . Atlantic, 2018.

Tilak, Raghukul. New Indian English Poets and Poetry: A Study of Nissim Ezekiel, Kamala Das, A K Ramanujan and Jayanta Mahapatra . Rama Bros., 1982.

Graziano Krätli

Read nissim ezekiel on iwe online.

- Jerry Pinto

You May Also Like

A.K. Ramanujan | Guillermo Rodríguez Martín

Nissim Ezekiel (1924-2004) was an Indian poet, actor, playwright, editor, and art critic. He is known as the father of post-independence Indian poetry in English, and his poems are included in the high school curriculum of NCERT. He was also a broadcaster and social commentator. He is a Padma Shri and Sahitya Akademi cultural award winner. Ezekiel played an important role in the development of Indian poetry in English. He died on 9 January 2004 in Mumbai.

Wiki/Biography

Nissim Ezekiel was born on Tuesday, 16 December 1924 ( age 79 years; at the time of death ). in Mumbai. His zodiac sign was Sagittarius. Nissim started his schooling at the Convent of Jesus and Mary and continued at the Antonio De Souza High School. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in Literature from Wilson College, Bombay University in 1947. After graduation, he taught for a year at Khalsa College, Mumbai and freelanced for various newspapers and magazines, and worked for M. N. Roy’s Radical Democratic Party. Later, he moved to England in November 1948, where he studied philosophy at Birkbeck College, London. while studying Philosophy, Nissim enrolled in evening courses in Chinese, Western Philosophy, and Art Appreciation at the City Literary Institute. He stayed there for three and a half years and later found his way back home by working as a deck scrubber on a ship carrying arms to India and China.

Nissim Ezekiel belonged to the Marathi-speaking Jewish community, known as the Bene Israel, in Mumbai.

Parents & Siblings

His father, Moses Ezekiel Talkar, was a Botany Professor at Wilson College, Mumbai and his mother, Diana Ezekiel Talkar, was a Principal in her own school. Nissim was the third among five children, three boys, and two girls, of his parents.

Nissim Ezekiel’s family

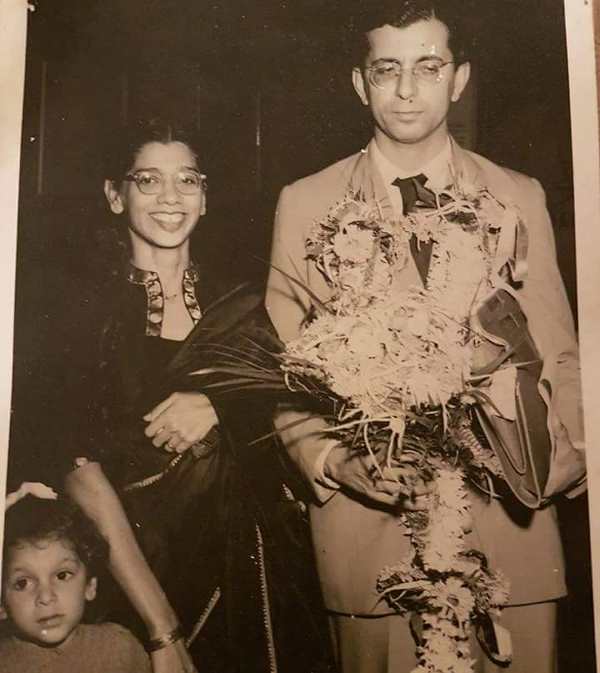

Wife & Children

Nissim got married in 1952 to Daizy Jacob Dandekarand, but the couple later got separated. They had 3 kids, a son, Elkana, and two daughters, Kalpana, and Kavita.

Nissim Ezekiel with his wife and daughter Kavita

Nissim Ezekiel followed Judaism.

Signature/Autograph

Literary career.

Nissim began his writing in the late 1940s. In 1952, he published his first book, “A Time to Change.” In 1960, he published another volume of poems, The Deadly Man. Between 1954 and 1959, he worked as an advertising copywriter and general manager for a picture frame company. In 1961, he co-founded the literary monthly Jumpo . In 1969, at the Writers Workshop, Ezekiel published his three plays, Nalini which include Nalini, Marriage Poem, and The Sleep-walkers. In 1976, he translated Jawaharlal Nehru’s poetry from English to Marathi, in collaboration with Vrinda Nabar, and co-edited a fiction and poetry anthology. His main themes of writing were pathos and melancholy. His poems are used in NCERT and ICSE English textbooks. His poem ‘Background, Casually’ is considered to be the most defining poem of his literary career.

Art Critic

He became an art critic for The Times of India for two years, from 1964 to 1966.

He worked as an editor for Poetry India from 1966 to 1967.

From 1961 to 1972, he was the head of the English Department at Mithibai College, Bombay. He was also a visiting professor at the University of Leeds in 1964 and the University of Pondicherry in 1967.

Awards and Honours

- In 1988, he was honoured with the Padma Shri award by the President of India.

- In 1983, he won the Sahitya Akademi cultural award.

On 9 January 2004, Nissim Ezekiel died at the age of 79 in Mumbai after fighting a long battle with Alzheimer’s. He died in a nursing home. The year he passed was considered the annus horribilis of Indian poetry in English.

Facts/Trivia

- He mentored many young writers like Dom Moraes, Adil Jussawalla, and Gieve Patel.

Dad often showed his work-in-progress to Mum. At times, he would read out to her while she was cooking our dinner which she paused, to patiently listen, sometimes encouraging him, though not fully approving. I’ve known Dad to actually re-write his poems based on how mum reacted.”

Nissim Ezekiel’s biography

- Ezekiel visited Paris twice, in December 1949, and in August 1951, and he wanted to settle there; however, he later quit the idea.

- During his stay in England, Ezekiel worked at the India House, the headquarters of India’s diplomatic mission to the United Kingdom, for a year. [1] University of Hyderabad

- His favourite writer was T.S Eliot.

References [+] [−]

Related Posts

Surjit Patar Wiki, Age, Wife, Children, Family, Biography & More

Rakesh Pathak Wiki, Height, Age, Wife, Family, Biography & More

Rupi Kaur Wiki, Age, Caste, Husband, Family, Biography & More

Lakshminath Bezbarua Wiki, Age, Death, Wife, Family, Biography & More

Tehmina Durrani Wiki, Age, Husband, Children, Family, Biography & More

Durvesh Yadav Wiki, Age, Family, Biography & More

Sanjeev Sanyal Wiki, Age, Wife, Family, Biography & More

Anita Nair, Wiki, Age, Husband, Children, Family, Biography & More

Jahnavi Barua Wiki, Family, Biography & More

Nikita Singh Wiki, Age, Boyfriend, Husband, Family, Biography & More

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Ground Reports

- 50-Word Edit

- National Interest

- Campus Voice

- Security Code

- Off The Cuff

- Democracy Wall

- Around Town

- PastForward

- In Pictures

- Last Laughs

- ThePrint Essential

M ost of us remember the name Nissim Ezekiel from studying his poem Night of the Scorpion in high school. Widely considered the father of Indian-English poetry in Independent India, Ezekiel’s talents, though, went beyond verse.

He wrote prose and plays, co-founded the literary magazine Imprint in 1961, worked as an art critic for The Times of India between 1964-66 and headed the English department of Mumbai’s Mithibai College’s from 1961 to 1972 with brief stints at University of Leeds and University of Chicago in the 1960s.

He taught at the University of Mumbai till he retired in 1984. His student and personal biographer R. Raj Rao remembered the poet fondly but critically.

“I learnt the need for rhythm and economy in a poetic line from him. But I was critical of the moralising stance he had assumed in many of his poems, which made them preachy,” he once said .

He was awarded a Sahitya Akademi award in 1983 and a Padma Shri five years later for his contributions to Indian-English writing. His most famous works include Latter-Day Psalms , The Discovery of India , The Third , The Unfinished Man , The Exact Name and Hymns in Darkness . His poetry dealt with themes of language and its powers and limitations, the craft of writing, religious scepticism, memory and, overwhelmingly, what it means to be Indian.

Towards the end of his life, the poet suffered from Alzheimer’s . He eventually passed away in 2004 in Mumbai at the age of 79.

On his 95th birth anniversary, ThePrint takes a look at some of his work.

A layered Indian-Jew identity

Born into a “ modestly bourgeois Jewish family ” on 16 December 1924, Ezekiel belonged to the Marathi-speaking Bene Israel Jewish community in Bombay, which at the time was 20,000 strong but in 2004, only 5,000 remained. His parents were teachers; his father taught botany at The Wilson College (later Ezekiel’s own alma mater) and his mother was a school principal. He went on to translate poetry from Marathi and even co-edited a fiction and poetry anthology.

Unlike a majority of Bene Israel Jews who returned to Israel following Partition and Indian Independence, Ezekiel’s family stayed on. In Three Plays , a comedy in three acts, Ezekiel revealed his frustration for people who go abroad “for false reputation”. One of the characters, Raj, expresses this in the lines — “You could go abroad and come back. They make better use of you when you go abroad and come back. At least they pay you better. You need not learn anything abroad. Just go and come back.”

He did touch upon the alienation felt by his ancestors on settling down in the Indian continent and struggling to find a place in the traditional caste-hierarchy. “My ancestors, among the castes, were aliens crushing seed for bread,” he wrote in a poem called Background, Casually . The line right after this reads “(The hooded bullock made his round)”, which is more of a detailed reference to his stock, who were oil-pressers from Galilee. The process of oil crushing involved a blind-folded bullock that crushed seeds to obtain oil. According to The Guardian , these oil-pressers were shipwrecked off the Indian subcontinent and eventually settled down, “forgot their Hebrew, yet maintained the Sabbath”.

Ezekiel, never shied away from his Jewishness or his language of choice being English. “Now I am through with /the Psalms; they are /part of my flesh,” he writes in his last collection of poems, Latter-Day Psalms (1982).

He also consistently reiterated the Indianness of his identity, and grappled with how history and present interact. A few lines from his collection, Poster Poems (1973), provide deeper insight into his layered identity —

“I’ve never been a refugee,

Except of the spirit,

A loved and troubled country

Which is my home and enemy.”

At a time when issue of Indianness and citizenship are on everyone’s mind, in the wake of the passing of the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill by both Houses of Parliament, Ezekiel’s words remain burningly relevant.

Also read: Harivansh Rai Bachchan — a critic of religiosity, class system and clingy lovers

Subscribe to our channels on YouTube , Telegram & WhatsApp

Support Our Journalism

India needs fair, non-hyphenated and questioning journalism, packed with on-ground reporting. ThePrint – with exceptional reporters, columnists and editors – is doing just that.

Sustaining this needs support from wonderful readers like you.

Whether you live in India or overseas, you can take a paid subscription by clicking here .

- indian poet

- night of the scorpion

Very interesting. thanks for sharing

Any articles on Gieve Patel’s poetry

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Most Popular

Rameswaram’s fisherfolk furious with katchatheevu politics. ‘don’t want island, just fishing rights’, shah’s stern message as rebellion brews in karnataka bjp — ‘rally behind modi or face consequences’ , mirv tech entry in nuclear arsenal must not lead india away from ‘no first use’ policy.

Required fields are marked *

Copyright © 2024 Printline Media Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Nissim Ezekiel

Nissim Ezekiel, who has died aged 79, was the father of post-independence Indian verse in English. A prolific dramatist, critic, broadcaster and social commentator, he was professor of English and reader in American literature at Mumbai (formerly Bombay) University during the 1990s, and secretary of the Indian branch of the international writers' organisation PEN.

Ezekiel belonged to Mumbai's tiny, Marathi-speaking Bene Israel Jewish community, which never experienced anti-semitism. They were descended from oil-pressers who sailed from Galilee around 150BC, and, shipwrecked off the Indian subcontinent, settled, intermarried and forgot their Hebrew, yet maintained the Sabbath. There were 20,000 Bene Israel in India 60 years ago; now, only 5,000 remain. Most of Ezekiel's relatives left for Israel; he served as a volunteer at an American-Jewish charity in Bombay.

Ezekiel was raised in a secular milieu by his botany professor father and school principal mother. Even as a schoolboy, he preferred TS Eliot, WB Yeats, Ezra Pound and Rainer Maria Rilke to the floridity of Indian English verse, and, when he began his writing career in the late 1940s, his adoption of formal English was controversial, given its association with colonialism. Yet he "naturalised the language to the Indian situation, and breathed life into the Indian English poetic tradition," wrote the Bangladeshi academic Kaiser Haq.

Ezekiel's poetry described love, loneliness, lust, creativity and political pomposity, human foibles and the "kindred clamour" of urban dissonance. He echoed England's postwar Movement (Philip Larkin, DJ Enright and Ted Hughes) but honed a distinct, ironic voice, moving from strict metre to free verse.

Over the course of his career, his attitude changed, too. The young man, "who shopped around for dreams", demanded truth and lambasted corruption. By the 1970s, he accepted "the ordinariness of most events"; laughed at "lofty expectations totally deflated"; and acknowledged that "The darkness has its secrets/ Which light does not know."

After 1965, he also began embracing India's English vernacular, and teased its idiosyncrasies in Poster Poems and in The Professor. In the latter he wrote: "Visit please my humble residence also./ I am living just on opposite house's backside."

Ezekiel took a first-class MA in literature at Mumbai University in 1947. After a brief dose of radical politics, he sailed to London the following year, studied philosophy at Birkbeck College and enjoyed "debauched affairs". His decrepit digs were immortalised in his debut poetry collection, Time To Change (1952).

That same year, Ezekiel worked his way home as a deck-scrubber aboard a cargo ship carrying arms to Indochina. The Illustrated Weekly of India made him an assistant editor in 1953, and published his poetry - and, for 10 years, he also broadcast on arts and literature for All-India Radio.

After dabbling as an advertising copywriter and manager of a picture frame company (1954-59), he co-founded the literary monthly Imprint, in 1961. He became art critic of the Times of India (1964-66) and edited Poetry India (1966-67). From 1961 to 1972, he headed the English department of Mithibai College, Mumbai. He experimented with LSD while in America in 1967, ceasing the habit in 1972. A year later, he presented an art series for Mumbai television.

Ezekiel once described India as too large for anyone to be at home in all of it. However, after tenures as visiting professor at Leeds University (1964) and Chicago (1967), plus lecture tours and conferences, he always gravitated back to his native city. Though a natural outsider, he still felt Indian, albeit "incurably critical and sceptical". As he wrote in Background, Casually: "Others choose to give themselves/ In some remote and backward place./ My backward place is where I am."

Throughout his career, Ezekiel continued to publish as a poet, bringing out many collections and some plays. He also translated poetry from Marathi in 1976, and coedited a fiction and poetry anthology, Another India (1990). A festschrift devoted to him, Mapping Cultural Spaces, appeared in 1998.

He acted as a mentor to younger poets, such as Dom Moraes, Adil Jussawalla and Gieve Patel. Many of his poems, such as The Night Of The Scorpion, and that supreme antidote to jingoism, The Patriot, are set-works in Indian and British schools.

Ezekiel received the Sahitya Akademi cultural award in 1983 and the Padma-Shri, India's highest civilian honour, in 1988. His wife Daisy, whom he married in 1952, but from whom he was separated, survives him, as do his son Elkana and daughters Kalpana and Kavita.

· Nissim Ezekiel, poet and scholar, born December 24 1924; died January 9 2004

Most viewed

Biography of Nissim Ezekiel

Nissim Ezekiel is an Indian poet who is famous for writing his poetry in English. He had a long career spanning more than forty years, during which he drastically influenced the literary scene in India. Many scholars see his first collection of poetry, A Time to Change, published when he was only 28 years old, as a turning point in postcolonial Indian literature towards modernism.

Ezekiel was born in 1924 in Bombay to a Jewish family. They were part of Mumbai's Marathi-speaking Jewish community known as Bene Israel. His father taught botany at Wilson College, and his mother was the principal of a school. Ezekiel graduated with his bachelor's degree in 1947. In 1948, he moved to England and studied philosophy in London. He stayed for three and a half years until working his way home on a ship.

Upon his return, he quickly joined the literary scene in India. He became an assistant editor for Illustrated Weekly in 1953. He founded a monthly literary magazine, Imprint, in 1961. He became an art critic for the Times of India. He also edited Poetry India from 1966-1967. Throughout his career, he published poetry and some plays. He was professor of English and a reader in American literature at Bombay University in the 1990s, and secretary of the Indian branch of the international writer's organization, PEN. Ezekiel was also a mentor for the next generation of poets, including Dom Moraes, Adil Jussawalla and Gieve Patel. Ezekiel received the Sahitya Akademi cultural award in 1983. He also received the Padma-Shri, India's highest honor for civilians, in 1988.

Ezekiel died in 2004 after a long battle against Alzheimer's Disease. At the time of his death, he was considered the most famous and influential Indian poet who wrote in English.

Despite the fact that he wrote in English, Ezekiel's poems primarily examine themes associated with daily life in India. Through his career, his poems become more and more situated in India until they can be nothing else but Indian. Ezekiel has been criticized in the past as not being authentically Indian on account of his Jewish background and urban outlook. Ezekiel himself writes about this in a 1976 essay entitled "Naipaul's India and Mine," in which he disagrees with another poet, V.S. Naipaul, about the critical voice with which he writes about India. "While I am not a Hindu and my background makes me a natural outsider," Ezekiel writes, "circumstances and decisions relate me to India. In other countries I am a foreigner. In India I am an Indian. When I was eighteen, a friend asked me what my ambition was. I said with the naive modesty of youth, 'To do something for India.'" We can see this attitude at work in Ezekiel's poetry—even when his poems are satirical, they come from the voice of a loving insider rather than someone who is looking from the outside. In this way, Ezekiel's poems are quintessentially Indian because they exist there. Ezekiel writes, "India is simply my environment. A man can do something for and in his environment by being fully what he is, by not withdrawing from it. I have not withdrawn from India."

The critic Vinay Lal argued in 1991 that it is not surprising that a poet like Ezekiel brought about so much literary change in India: "It is perhaps no accident either that the first blossoms of the birth and growth of modern Indian poetry in English should have come from the pen of a poet who, while very much an Indian, belongs to a community that in India was very small to begin with, and has in recent years become almost negligible, a veritable drop in the vast ocean of the Indian population."

Study Guides on Works by Nissim Ezekiel

The poems of nissim ezekiel nissim ezekiel.

Nissim Ezekiel's collected poems were first anthologized in 1992 by Oxford India Paperbacks. Since then, Oxford University Press has published three impressions and two editions of the anthology. The second edition, published in 2007, contains a...

- Study Guide

India Votes 2024

An Allahabad HC judge is using morality norms to deny protection to live-in couples

High funding but poor results: Bangladesh struggles with Bengal tiger conservation

Aditya Birla group donated Rs 100 crore to BJP two months before government’s Vodafone Idea bailout

Indian architecture: What was the influence of colonial styles on Indian bungalows?

Centre directs YouTube to take down ‘National Dastak’ from its platform

‘A storm in an ocean’: Hindustani vocalist Kumar Gandharva refused to be bound by orthodoxy

Does Dhruv Rathee’s popularity worry the BJP?

How do you get citizens to change their behaviour? Lesson’s from France’s ‘zero-waste’ push

Demolishing intangible barriers: Disability inclusion starts with changing societal attitudes

By financing environmentally damaging projects, can Indian funders be held liable?

‘A Time to Change’: How Nissim Ezekiel became the pioneer of a new era of English poetry in India

Published in 1952, the volume was one of the first significant books of postcolonial poetry in english..

Nissim Ezekiel’s A Time to Change was published seventy years ago, in 1952. To many, this was the first significant book of postcolonial poetry in English. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was published in England, where Ezekiel had travelled on impulse, and managed to stay nearly four years before returning to his beloved Bombay.

The fuller history of these movements still awaits their evaluation, though we are fortunate in having had Raj Rao as a sympathetic biographer. For Ezekiel’s work was not simply significant chronologically – ie, written five years after Independence. Rather, it is believed that its larger importance was its disruption of a certain grandiose register of poetry in English – the favoured example here is Aurobindo Ghose whose works such as Savitri (over 20,000 lines) sought no less than the redemption of the entire human race.

As said, a more comprehensive and inter-connected literary history of all poets of this era still needs to be written. For example, there are many ways of rehabilitating figures like Aurobindo, and indeed that mythic register has continued to haunt many poets. (One thinks, for example, of Ezekiel’s near contemporary, Muktibodh, writing in Hindi). Indeed, the very first lines of A Time to Change itself begin on just such a high register – there is a quotation from Revelation, the invocation of the Lord, and redemption. Many more poems in the collection directly invoke prayers, gods, and prophets.

A poet of his time

Yet, the lines from the first poem continue thus: “the music / Never quite completed, redemption/ Never fully won.” There has been some mutation, and there is a greater sense of diffidence and thwarted confidence. This is closer to the language of the post-1947 decades that Ezekiel helped concretise. The idiom has turned more modest, more wistful, more doubting. This was only apt – after the heroism of the independence movement and the devastation of war and partition, it was always going to be harder – at least for many decades – to speak in such grand notes again.

Redemption was more likely to be won, if at all, only in the “private country of my mind”; the great masses that looked so unified in their quest for freedom shows its other side as “continually / [reducing] to something less than human by the crowd, / Newspapers, cinemas, radio features, speeches”. All such media evoke the mass person, and is to Ezekiel a corruption of both social and personal human endeavour. The mutual infection of the isolated individual with the tyranny of the mass social is the “double horror” that Indian democracy was prey to even from the 1950s.

Of course many might argue that the truly great poets – say, a Tagore or a Nirala – could more expertly navigate multiple registers, sometimes within the same collection, or even within the same poem. Ezekiel managed rather fewer, successful simple poems – in this collection one might count Occupation, Birth, Reading. But equally, with hindsight, one may say that Ezekiel could never, despite his play with syntax, quite master the English vernacular of India with the verve, abrupt humour or observational skills of, say, an Arun Kolatkar or Arvind Krishna Mehrotra.

A celebration of the modest

What might be the core of Ezekiel’s achievement in this collection – even if it was not something he always managed to sustain – were really the poems that eked out that modest voice, that celebrated the modest “tasting freedom / On a bicycle.” What is a new country to do when, after the grandness of an independence movement, it suddenly finds itself rather unimportant in world affairs – apart from being famously desperately poor?

This is a moment (one might periodise it as belonging to the 1950s and 1960s, though it casts its shadow further) that required an unblinking eye. Here too, English was no different from any other Indian language – all of them had to be brought to the register of the everyday life-hustle – the familiar tedium of uninspiring livelihood, poorly compatible marriages and families, the banal squalor of the street, the fragility of all notions of community.

A country recently heroic in the world’s eye for fighting a mighty power is suddenly exposed – sans all that attention – as struggling to build basic institutions, be they of governance, or (literary and publishing) markets. What can one do except “unveil, expose, expound”?

A Time to Change is also a foretaste of Ezekiel as this assemblage of different pathways. For one, he was mostly alone in his writing till poetry in English picked up substantially in India in the 1970s. Through the 1950s and 1960s, he largely had to plough his faith alone. This collection thus also bares his essential – accommodative, anaesthetised – solitude, a solitude that nevertheless folded back into the world a young, embryonic nation, uncertain of its path, if very much on its way.

What and who we are today is being measured and tested against that generation’s labouring dawn: “Then we set to work as we had planned. / Not for us the dream, the dark illusion…We could not figure what it is went wrong”.

Literary Articles

- A Farewell to Arms (1)

- Absurd Drama (5)

- African Literature (11)

- Agamemnon (2)

- Agha Shahid Ali (1)

- American Literature (32)

- Amitav Ghosh (6)

- Anita Desai (1)

- Aristotle (6)

- Bengali Literature (4)

- British Fiction (20)

- Charles Dickens (8)

- Chaucer (1)

- Chomsky (11)

- Classics (12)

- Clear Light of the Day (1)

- Cotton Mather (1)

- Death of a Salesman (5)

- Derek Walcott (3)

- Derrida (1)

- Descartes (1)

- Dr. Samuel Johnson (7)

- Edward Said (1)

- Elaine Showalter (2)

- ELT Terms Difined (20)

- Emily Bronte (6)

- Emily Dickinson (3)

- English History (9)

- English Language (2)

- English Literature (2)

- Great Expectations (7)

- Greek Literature (7)

- Heart of Darkness (2)

- History of English Language (15)

- History of English literature (9)

- Indian Literature (18)

- Indian Literature in English (2)

- Indian Poetry in English (23)

- Irish Literature (4)

- John Donne (2)

- John Keats (5)

- John Locke (2)

- Kamala Das (17)

- Kim by Kipling (2)

- Latin American Literature (2)

- Life and time of Michael K (3)

- Linguistics (13)

- Literary Criticism (28)

- Literary Terms (7)

- Literary Theories (19)

- Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1)

- Machiavelli (2)

- Magic Realism (2)

- Marvell (2)

- Maupassant (1)

- Measure for Measure (3)

- Metaphysical poetry (3)

- Native Son (1)

- Nissim Ezekiel (4)

- Oedipus Rex (2)

- Othello (5)

- Phaedra by Seneca (3)

- Philosophy short notes (1)

- Postcolonial Reading (1)

- Postmodernist reading (2)

- Pride and Prejudice (4)

- Psychoanalytic Reading (1)

- Quartet (1)

- R K Narayan's The Guide (10)

- Red Badge of Courage (1)

- Riders to the Sea (1)

- Robert Frost (4)

- Roland Barthes (3)

- Romantic Literature (13)

- Romantic Poetry (4)

- Ronald Barthes (3)

- S .T . Coleridge (4)

- Samuel Beckett (1)

- Saul Bellow’s Seize the Day (1)

- Seamus Heaney (1)

- Seize the Day by Saul Bellow (4)

- Shakespeare (22)

- Shakespeare's Sonnets (6)

- Shelley (2)

- Song of Myself by Whitman (3)

- Sonnets (3)

- Sons and Lovers (5)

- Sophocles (2)

- South Asian Literature (2)

- Strange Pilgrims by Gabriel Garcia Marquez (3)

- T. S . Eliot (10)

- Teaching Language Through Literature (5)

- Tempest (4)

- Tennyson (1)

- The Ancient Mariner (5)

- The Great Gatsby (3)

- The Iliad (1)

- The Old Man And The Sea (1)

- The Playboy of the Western World (3)

- The Return of the Native (4)

- The Scarlet Letter (2)

- The Spanish Tragedy (1)

- The Turn of the Screw (3)

- The Waste Land (2)

- The Zoo Story by Adward Albee (4)

- Things Fall Apart (4)

- Thomas Hardy (4)

- Victorian Literature (5)

- W. J. Mitchell (1)

- W.B. Yeats (11)

- Waiting for Godot (3)

- Western Philosophy (13)

- William Blake (3)

- Wole Soyinka (5)

- Wordsworth (11)

- Workhouse Ward (1)

Friday, November 29, 2013

Nissim ezekiel as an indian poet writing in english, writer's profile.

(92) 336 3216666

Nissim Ezekiel

Nissim Ezekiel was an Indian-conceived author of Jewish plummet. He has been portrayed as the father of post-independence Indian poetry in English. He had various assortments of verse distributed which were well known. A few, for example, ‘The Night of the Scorpion’, and the counter patriotism sonnet ‘The Patriot’, are standard stanzas despite everything concentrated in some British and Indian schools.

He had a fluctuated profession as an English instructor in India, England, and the United States. He composed plays, filled in as a supporter on Indian radio, and contributed numerous basic articles to the literary segments of magazines and papers.

Ezekiel was conceived in December 1924 in Mumbai. The family lived in a Marathi-talking network known as the “Bene Israel.” It had approximately 20,000 occupants around then. Not at all like different networks far and wide this was a quiet spot with no proof of anti-Semitism to stress over. They were a generally princely family with his father being a teacher of Botany at the Wilson College in Mumbai. His mother served as the Principal of the school that she had set up.

Nissim was knowledgeable and had a specific preference for the verse of, for example, T S Eliot and Ezra Pound. He could do without stanza in his own language and, as he grew up, his composing pulled in the discussion. It was viewed as excessively near the old provincial impacts by numerous radicals in India. He went to Wilson College and he increased a degree in writing and quickly began teaching English Literature.

India was, strategically, a hotbed of movement around then and he took a functioning enthusiasm for a brief period yet before long chose to venture out to England by ship. He went through the following three years examining theory at Birkbeck College in London, living in a low standard settlement. Afterward, he came back to India. He served in India and continued publishing his books. He received a Padma Shri award from the government of India for his services for literature.

A Short Biography of Nissim Ezekiel

Nissim Ezekiel was born on December 16 th, 1924. He was born in Mumbai in Maharashtra, India. His father served as a Professor at Wilson College. He would teach Botany. His mother served as Principal of that school. This was her own school. His family basically belonged to the Jewish Community. This community was called Bene Israel. Their language was Marathi.

He completed his B.A. in 1947. His subject was Literature. He completed it from Wilson College, Mumbai. This was under the affiliation of Bombay University. Afterward, he started teaching English literature. He also started publishing literary articles in various journals and papers. During the partition of the Subcontinent in India and Pakistan, he went to England. There he completed his degree in Philosophy from Birkbeck College, London. He stayed for three years in England. Afterward, he returned to India. He was deck-scrubber on a ship that was carrying arms to Indochina.

He published his book ‘The Bad Day’ in 1952. In 1960, he published another book of poetry. It was titled ‘The Deadly man.’ From 1954 to 1959, he served as a general manager and advertising copywriter for a picture frame company. In 1961, he established a monthly magazine ‘Jumpo.’ In 1961, he also became the head of the English department at Mithibai College in Bombay. He served there till 1972.

In 1965, he published his next book of poetry. This was titled ‘The Exact Name.’ During this phase of his career in 1964, he also served as a visiting professor at the University of Leeds. In 1967, he was appointed as a visiting professor at the University of Pondicherry.

In 1969, he published his play ‘The Damn Plays.’ 1076, he translated the poetry of Jawaharlal Nehru to the Marathi language. His poetry was in English. Ezekiel`s poems are used in the course books of classes to be studied as study material in various parts of India.

He is called the father of Modern Indian English Poetry. In 1988, he was awarded the Padma Shri award by the then president of India.

He suffered for a very long time with Alzheimer’s disease. He fought with but lost to it and succumbed to death in 2004. At the time of death, he was 79 years old. He died in Mumbai.

Nissim Ezekiel’s Writing Style

Technique and style.

Ezekiel is the first Indo-Anglican artist to show reliably that craftsmanship is as essential to a poetic work as its topic. He doesn’t respect the composition of a poem as an easygoing issue. As per him, the composition of a poem includes a great deal of drudge. He says that we should work to be delightful.

In one of his sonnets, Ezekiel is of the view that the best writers hang tight for words. He views a sonnet as a natural, coordinated piece. In this way, the structure, the form, the words, and the expressions utilized by him become significant and a matter of imperative concern.

His Language

Ezekiel is practical in the utilization of language. He has faith in lucidity, economy, and unequivocal quality. He has been receiving a conversational style. The effortlessness and conversational simplicity make his verse vital. The continuous utilization of a casual figure of speech gives to his poetic work a fine mix of the clearness of articulation and cogency of contention.

Lack of clarity is deliberately kept away from by the artist and magnificence and exposed state of articulation are regularly amalgamated together. His poem ‘The Egoist’s Prayers’ shows his idyllic language at its best.

His Use of Words

Ezekiel shows a sharp feeling of structure and form and an exceptional concern for the utilization of the correct words in the right places. Words are picked cautiously by him. The economy and precision in the utilization of words are laudable. His words are exceptionally interesting. He utilizes words from the normal regular jargon. He disregards the utilization of antiquated words. He makes a fine lovely impact by mixing sense and sound. The utilization of contemporary saying grants effortlessness, clarity, and lucidity of articulation to Ezekiel’s lovely style.

His Use of Wit and Irony

Ezekiel is famous for his rich comical inclination and for the sharpness of his mind and incongruity. In a significant number of his poetic works, he has scorned the absurdities and indiscretions of the Indian individuals. For this reason, he has utilized silliness and incongruity as his central weapons.

In his poetic works like ‘Farewell Party For Miss Pushpa’, ‘The Railway Clerk’ and ‘The Healers and Guru’ one can without much of a stretch discover Ezekiel’s funniness, mind, and incongruity. Consequently, there is an enormous reserve of funniness, mind, and incongruity in Ezekiel’s verse.

His Use of Symbol and Imagery

Nissim Ezekiel utilizes profoundly reminiscent and intriguing images and pictures in his verse. Through these embellishment devices, he makes the theoretical abstract. The ladies, the city, and nature are repeating images in his verse. Slopes, waterways, winds, skies, sun, and downpours are likewise some significant pictures.

With the assistance of these normal pictures, Ezekiel dexterously brings out a realistic image of human life. Ezekiel’s best poetic works have an indefinable pictorial quality. They show a conspicuous liking for the visual expressions. For example ‘In India’ the artist has given us distinctive pictures of Bombay.

Stylistic Freewheeling

This stylistic freewheeling is normal for practically all of his poetical works. In the event that he has utilized profoundly expressive and telling expressions in his works, he has likewise slipped by in ‘The Exact Name into Shelleyian’ deliberations like fantasies of light or rest strolling broadcasting in real-time of thought.

He additionally double-crosses energy for utilizing concentrated expressions, which are allegorical in nature, and institute the focal weight of the sonnet plainly. In ‘The Double Horror’ the writer discusses wilderness development. It passes on the extraordinary increment of the modem degenerate world. While alluding to sexual relationships in ‘Paean’ he discusses the geometry of affection.

So, taking everything into account he causes us to notice ‘The epic of strolling in the road’. The utilization of articulations ”wilderness’, ‘geometry’, and ‘epic’ is profoundly interesting. In the previous works likewise happened such expressions as anecdotes of heck, happy amazement, and lasting daybreak.

Length of Sentences