Video conferencing in the e-learning context: explaining learning outcome with the technology acceptance model

- Published: 21 February 2022

- Volume 27 , pages 7679–7698, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Daniel R. Bailey 1 ,

- Norah Almusharraf 2 &

- Asma Almusharraf ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8916-6768 3

6526 Accesses

29 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This study uses the technology acceptance model (TAM) to help explain how the use of technology influences learning outcomes emanating from engagement with the Zoom video conference platform. To this end, structural equation modeling was used to analyze the relationships among the TAM variables in reference to Zoom taught during the Covid-19 pandemic. Following a cross-sectional research design, data were collected using Davis's TAM (1989) scales including perceived ease of use (PEoU), perceived usefulness (PU), behavioral intentions, and attitude from 321 South Korean university students attending their 10 th week of English as a foreign language (EFL) conversational English classes. Results revealed that seven of the ten proposed hypotheses were confirmed, with path coefficients having small to large effect sizes. Most notably, PEoU with Zoom strongly affected PU and actual use. In addition, PU with Zoom predicted intentions to use Zoom in the future; however, it failed to influence perceived learning outcomes. While PU predicted future use, it did not influence actual use regarding how well students reported their current performance in their video conference course. PEoU with video conference tools was an influential antecedent to usefulness, attitude, and perceived learning outcome. Lastly, two notable instances of mediation through PU occurred. In consideration of findings, students and instructors should be well trained on the use and functionality of video conference software before its implementation in video conference classrooms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adoption of online mathematics learning in Ugandan government universities during the COVID-19 pandemic: pre-service teachers’ behavioural intention and challenges

Geofrey Kansiime & Marjorie Sarah Kabuye Batiibwe

Online learning in higher education: exploring advantages and disadvantages for engagement

Amber D. Dumford & Angie L. Miller

Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning the new domain of learning

Jamal Abdul Nasir Ansari & Nawab Ali Khan

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Methods addressing challenges faced during the e-learning adoption in the context of higher education were reported during the emergency remote teaching in the wake of Covid-19 campus closures (Almaiah et al., 2020 ; Ho et al., 2020 ; Vladova et al., 2021 ). To overcome social distancing issues, several studies addressed the use of educational e-learning platforms with video conferencing tools that dominated teaching and learning, including Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Moodle, and Google Classroom (Alfadda & Mahdi, 2021 ; Bui et al., 2020 ; Mailizar et al., 2021 ; Virtič et al., 2021 ). The effectiveness of these video conference platforms was evident during the pandemic spread and offered an appropriate solution to the difficulties with emergency online teaching (Pal & Vanijja, 2020 ).

Several studies during the Covid-19 pandemic incorporated the technology acceptance model (TAM) as a framework to understand how technology was utilized during the online classes. The TAM, initiated by Davis ( 1989 ), is one of the most well-established conceptual models in interpreting and predicting the implementation behavior of Information Technology (IT) (Chang et al., 2017 ) and helped guide the implementation of e-learning tools during the Covid-19 pandemic. Amid Covid-19 emergency remote online classes, studies looked at e-learning systems (Almaiah et al., 2020 ; Ho et al., 2020 ) and online learning tools in general (Mishra et al., 2020 ). However, there is a need for TAM studies that specifically reference video conference platforms during the Covid-19 pandemic (Alfadda & Mahdi, 2021 ).

The video conference platform Zoom was the referenced technology of interest in this study. This is a widely used video conference platform that allows for multiple ongoing sub-conferences referred to as breakout rooms (BOR). In a BOR, instructors can separate students into partners and groups to independently practice conversational English. In conventional offline settings, conversational English classes are collaborative in nature and help develop social ties among classmates (Farr & Murray, 2016 ). In English as a foreign language (EFL) classes that focus on conversation skills, having only one speaker at a time becomes problematic because it decreases the amount of student-speaking time. To compensate while teaching in video conference settings, the instructor can create breakout rooms that allow students to work together independently from the main class and instructor. In these sub-conference rooms, the instructor can have students participate in partner and group activities, and the students are responsible for using English while in their groups outside the instructor's supervision. In addition to the BOR function, Zoom allows for several multimodal communication opportunities in online settings, including the use of group and one-to-one chat options, attention indicators (e.g., smiling faces and raising hands, and screen-share options. Other Zoom features include audio-only (i.e., no camera), whiteboard, annotation tools, file sharing, and meeting recordings.

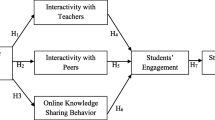

1.1 Proposed model

The proposed model in Fig. 1 illustrates the variables of interest from the TAM framework and how they are expected to help explain the reported levels of actual use as it pertains to perceived learning in video conference courses.

Proposed Model (Davis, 1986 )

This study incorporated the TAM to help explain how Zoom video conference features contribute to learning outcomes in conversational English courses taught during the Covid-19 pandemic. The TAM framework helps explain behavioral intentions and the actual use of technology (Davis, 1986 ), and studies suggest PEoU influences PU, while both TAM variables influence attitude and behavioral intentions to use the referenced technology in the future (Almaiah et al., 2020 ). Myriad studies have used the TAM as a framework to investigate different learning technologies like e-learning systems (Coman et al., 2020 ; Park, 2009 ), including mobile learning (Park et al., 2012 ), formal Learning Management System (LMS) software (Alharbi & Drew, 2014 ; Revythi & Tselios, 2019 ) and e-portfolio tools (Abdullah & Ward, 2016 ). The reason for the wide use of the TAM is its flexibility with a variety of technology devices and platforms, and according to Saadé et al.'s ( 2007 ) comparative study, the TAM is a solid theoretical model whose validity can extend to the multimedia and the e-learning context.

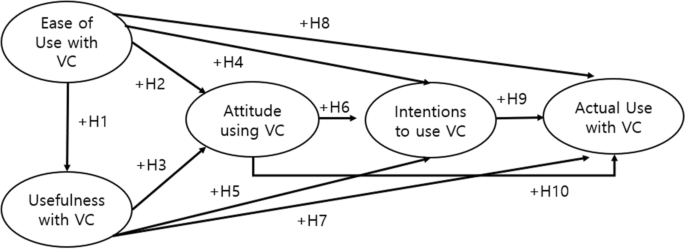

1.2 Proposed hypotheses

The modified TAM used in the current study referred to attitude pertaining to conversational English activities assigned during the video conference classes (e.g., partner and small group EFL speaking activities). Previous studies utilized the TAM to examine factors related but not limited to experience, perceived usefulness, technology anxiety, and technology self-efficacy (Abdullah & Ward, 2016 ; Chang et al., 2017 ). TAM findings during Covid-19 indicate PEoU and PU with educational technology directly influenced students' attitudes and behavioral intentions (Almaiah et al., 2020 ; Ho et al., 2020 ; Mishra et al., 2020 ). In line with the established TAM framework, the following hypotheses are posited to help explain the PU and attitudes towards the use of the Zoom video conference platform during the Covid-19 pandemic:

H1: Perceived ease of use positively affects perceived usefulness with video conference tools.

H2: Perceived ease of use positively affects attitudes towards using video conference tools.

H3: Perceived usefulness positively affects attitudes towards using video conference tools.

When participating in video conference courses through Zoom, ease of use, usefulness, and attitude towards the learning environment are proposed here to influence behavioral intention and actual use. The TAM suggests several external variables that influence users' decisions about when and how to use a specific technology. These variables are determinants of PU and PEoU, which involve individual differences, system characteristics, social influence, and facilitating conditions (Venkatesh & Bala, 2008 ). There is a current need to understand how the TAM framework can help explain behavioral intentions and actual use when referencing video conferencing features in fully online synchronous classes taught using the video conference platform Zoom. Understanding these factors can help identify the influence attitude has on the relationship between the use of video conference tools and expected learning outcomes. To explain 'users' technology adoption behaviors, it is essential to understand the external variables of PU and PEoU (Al-Gahtani, 2016). To this end, the following hypotheses were posited:

H4: Perceived ease of use positively affects behavioral intentions with video conference tools.

H5: Perceived usefulness positively affects behavioral intentions with video conference tools.

H6: Attitude positively affects behavioral intentions with video conference tools.

Modifications are warranted with the TAM framework in the e-learning context when reported perceptions and acceptance of the referenced technology is connected to learning outcomes pertaining to the actual use (Alfadda & Mahdi, 2021 ). In communication courses like conversational English, a required university course in South Korea, participation on the video conference platform through active conversations equates to higher learning expectations because participation is a crucial grade component (Crosthwaite et al., 1986 ). Following Alfadda & Mahdi's ( 2021 ) use of the TAM with EFL student, actual use was defined as perceived learning that occurred using the video conference platform, Zoom. Using the TAM to explain actual use as it pertains to expected learning outcome, the following hypotheses were put forward:

H7: Perceived usefulness positively affects reported learning outcomes with video conference tools.

H8: Perceived ease of use positively affects reported learning outcomes with video conference tools.

H9: Behavioral intention positively affects reported learning outcomes with video conference tools.

H10: Attitude positively affects reported learning outcomes with video conference tools.

2 Literature review

2.1 technology acceptance model.

The TAM is an information system theory that forms how users accept and use technology and is based on Fishbein & Ajzen's ( 1975 ) theory of reasoned action, which posits that pre-existing attitudes and behavioral intentions drive individual behavior. The TAM proposes that a user's attitude toward a new technology determines whether the user will use or reject the technology. Such an attitude is influenced by two significant beliefs: PU and PEoU, both directly affecting learners' intention to use technology (Al-Gahtani, 2016; Lee et al., 2014 ; Tarhini et al., 2014 ).

Similarly, Al-Gahtani (2016) confirmed that most of the hypotheses of the TAM are supported, suggesting that better organizational e-learning management can lead to greater acceptance and effective implementation. The TAM is not without criticism. Chuttur ( 2009 ) found fault with the TAM for its limited explanatory and predictive power, leading to a lack of practical value. To offset Chuttur ( 2009 ) criticism, researchers can substitute learning outcome beliefs for user log data to extend the TAM application and practicality into the e-learning context (Alfadda & Mahdi, 2021 ).

Variables within the technology acceptance model include perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, attitude, behavioral intentions (i.e., future use), and actual use. The TAM can be used to explain further variance in technology use with the inclusion of additional exogenous variables such as subjective norms, experience, and joy (Chang et al., 2017 ). Typically with the TAM, the most critical constructs are PU and PEoU. PU refers to the extent to which one believes that using specific technology will develop their performance, whereas PEoU partly refers to the mental effort and ease of learning exerted when using technology (Davis, 1989 ). In the educational contexts, TAM has been explored to verify how learners' PU and PEoU affect their acceptance of e-learning technology (Park, 2009 ) and their behavioral intention to use that technology in future circumstances (Al-Gahtani, 2016; Almaiah et al., 2020 ; Lee et al., 2014 ; Tarhini et al., 2014 ). According to Pajo & Wallace ( 2001 ), successful technology integration in the learning context depends on available technologies and how they are embraced and used. Similarly, Pituch & Lee ( 2006 ) noticed that PU and PEoU determine learners' acceptance and overall e-learning performance.

Attitude is defined as the degree to which a user is interested in using the system. According to Davis ( 1989 ), attitude is the determinant of behavioral intention, leading to actual system usage. Saadé et al.'s ( 2007 ) TAM study on 362 students in the e-learning context indicated that PU significantly affects university learners' attitudes toward multimedia learning environments. Their study revealed that learners' attitudes affect their behavioral intention to use technology. If instructors and learners find e-learning valuable and easy to use, they will develop a positive attitude towards it.

Several studies have shown attitude as an essential factor in acceptance behavior (Alharbi & Drew, 2014 ). Cheung & Vogel ( 2013 ) investigated students' attitudes and revealed that PEoU and PU influenced students' attitudes toward technology. PEoU was also found to predict PU and to be a stronger predictor of attitude than PU.

2.2 Video conferencing tools and TAM

During the Covid-19 pandemic, video conferencing tools such as Zoom, Google Meet, and Microsoft Teams became popular teaching platforms to replicate face-to-face classes (Al-Samarraie, 2019 ). Video conferencing tools are defined as real-time audio and video means of communication between individuals from geographically different places (Mader & Ming, 2015 ). However, the effectiveness of such platforms depends on both PU and PEoU (Park, 2009 ). Those e-learning platforms should provide learners with tools and features needed to support learning that is useful and easy to use. Through a proposed usability framework for e-learning tools, Zaharias ( 2009 ) found that students could not achieve complex learning tasks using e-learning systems without help. The poor accessibility of the platform might cause learners' dissatisfaction and reduce their learning (Zaharias, 2009 ). To best provide help, Granic & Marangunic ( 2019 ) found that there is a demand to address learners' acceptance, attitude, purpose, and use of video conferencing tools, among other technological learning tools, early in the implementation process.

Pal & Vanijja ( 2020 ) have implemented a survey among university students that measures the usability of Microsoft Teams as a reference platform based on the TAM. They concluded that a higher perception of usability leads to the adoption of the online platform. Similarly, Taat & Francis ( 2020 ) conducted a study to assess students' acceptance level of e-learning and identified factors that influence it. Their study showed that students' acceptance of e-learning is influenced by the benefits and usefulness of the online platform that could, in turn, enhance the effectiveness of learning online. Moreover, in a study by Alfadda & Mahdi ( 2021 ), the PEoU and PU are considered to affect the acceptance of Zoom as an e-learning platform that substantially and positively correlates with self-efficacy with the technology in use. Furthermore, Pal & Patra ( 2021 ) examined the perceptions of 232 students who have taken part in a full-semester video-based online learning course during the pandemic. Their results showed that video-based learning positively fits into the student's perception and their actual use of the system.

Perceived learning success greatly depends on how learners perceive the learning process effectively. When learners have positive attitudes towards their learning process, they might promote a higher level of self-efficacy and, in turn, achieve higher learning outcomes (Gupta & Bostrom, 2013 ; Hattie & Yates, 2014 ; Janson et al., 2017 ). Moreover, Jan ( 2015 ) indicated that students' academic self-efficacy and computer self-efficacy in online education programs positively influence student academic motivation and satisfaction. Students' satisfaction with e-learning is linked with students' perceived learning from the online platform.

Landrum ( 2020 ) highlighted that the technology used must be clearly introduced to students to ease the online learning process and consequently enhance students' ability to perform successfully. Therefore, research assessing learners' attitudes and acceptance of video conferencing tools in online learning are necessary, especially when the institutions and learners are not well prepared for the new class delivery mode during emergency online courses like those experienced during the Covid-19 pandemic.

3.1 Overview and participants

This study followed a cross-sectional survey research design that used Davis's ( 1986 ) TAM framework to measure levels of PeoU, PU, attitude, behavioral intention, and learning outcome. A cross-sectional research design involves looking at data at a specific point in time. The data here pertained to perceptions and behavior with videoconference tools used to support EFL course learning objectives (e.g., develop English speaking and writing skills). The specific time of interest for this survey study was the second semester of fully online courses due to Covid-19. By the second semester, students were considered to have sufficient experience with the videoconference technology under investigation.

The participants in this study were a combination of freshmen and sophomore students attending conversational English courses in South Korea (n = 321; M = 129, F = 192), and ranged from a variety of majors including economics, logistics, nursing, nutrition, social welfare, chemistry, history, Korean, Chinese, and interior design. Criteria for inclusion into the study entailed students attending conversational English courses using the video conference platform Zoom taught by native English-speaking instructors. To accomplish communication goals with Zoom, the conversational English instructor first provided talking points for students to discuss with a partner or in small discussion groups and then separated students into their own sub-conference rooms (i.e., break-out rooms).

3.2 The instrument

The first part of the two-part questionnaire contained a nominal scale to collect basic information pertaining to demographic information such as gender, self-reported L2 proficiency, and academic major. This was followed by the second section that included the three TAM scales of interest, PEoU, PU, and behavioral intentions, which originated from Davis ( 1989 ) survey. The fourth variable, attitude, was developed in-house and pertained specifically to the learning activities performed through Zoom (e.g., partner and group speaking activities). For the actual use of video conference tools, five modified items from Bong & Skaalvik's ( 2003 ) academic self-efficacy for learning scale were used. An original item states, "I can tell what is important in my class," while a modified item states, "I can tell what is important in my video conference class." These five items were chosen because they explicitly referred to learning that emanates from the actual use of the video conference platform. Table 1 lists each scale with its corresponding items. Participants were asked to respond using a 5-point interval scale for the five variables of interest, with one denoting strong disagreement and five as strong agreement with the statements.

3.3 Data analysis

Initially, the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS; Version 26.0) was used to calculate mean score and Pearson correlation analysis on the variables of interest. Next, Analysis of Moment Structure (AMOS; Version 21.0) was used for structural equation modeling. After data cleaning and an initial view of the data, the next step entailed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with AMOS to develop the measurement model. After this, structural equation modeling was used to measure the causal relationships within the proposed structural model.

3.4 Data cleaning

Data cleaning initially entailed outlier analysis to check for irregularities within the data. Using linear regression, Mahalanobis and Cook's distance were used to check for outliers in which 11 existed and were consequently removed. Overall, fairly normal distributions were observed concerning indicators for the latent factors. Kurtosis and skewness values were in the acceptable range, between -1.0 and + 1.0, providing further support for normal univariate distribution (George & Mallery, 2010 ). The study next looked at Variable Inflation Factors (VIF) to test for multicollinearity. In no case was a VIF greater than 3 observed, far below the upper threshold of 10. Regarding the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure (KMO) of sampling adequacy, a value of 0.901 was observed which was above the recommended value of 0.60. Regarding Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, the value was significant (χ 2 (55) = 3498.50, p < 0.001). Lastly, commonalities were above the recommended value of 0.50 (Kline, 2015 ). When complete, it was determined that the data were sufficient to proceed with structural equation modeling.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 results.

To measure linearity between the observed variables, bivariate Pearson correlation was calculated. All the observed variables of interest were significant in the medium to high levels, with r values ranging from 0.292 to 0.643 (Cohen, 1988 ). In addition to Pearson correlation, Table 2 displays mean score values for variables that ranged from 2.83 to 3.23 and standard deviations ranging from 0.70 to 0.83. PEoU produced the highest mean and standard deviation, indicating moderate levels of variation in how students regarded comfort with using Zoom. Regarding gender, females reported a having a slightly better attitude towards Zoom activities, however, no other gender differences were noticed. L2 proficiency strongly correlated with actual use, and to a lesser extent, PEoU and PU.

4.2 Validity checks

The next step entailed checking convergent and discriminant validity to ensure the unidimensionality of the five-construct model. Cronbach alphas ranged from 0.77 to 0.92, indicating adequate internal reliability ( see Table 2 ), above the recommended 0.70 limit (Nunnally, 1994 ). Next, composite reliability scores were above the recommended 0.60 values. The average variance extracted was above the 0.50 value (Hair et al., 2006 ) except for attitude, which was 0.424. AVE's above 0.40 is considered adequate when Composite Reliability (CR) values are above 0.60 (Fornell & Larker, 1981 ), which attitude safely was. The study proceeded to test the proposed model upon confirming validity (Table 3 ).

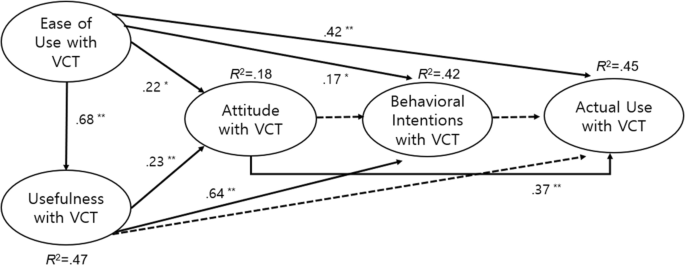

4.3 Structural model

Confirmatory factor analysis with AMOS was used to estimate the model's parameter. Goodness-of-fit was reached using a series of recommended indices, including the Root Mean Square Error of Approximations (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Normal Fit Index (NFI) (Hair et al., 2006 ; Kline, 2015 ). The structural equation model, upon adjusting according to the modification indices, produced a good fit (χ 2 /df = 2.158, p < 0.001; TLI = 0.942; CFI = 0.952; NFI = 0.925; RMSEA = 0.059; PCLOSE = 0.060). Figure 2 displays the final model with regression weights and path coefficients. The significant paths are shown as solid lines and insignificant paths as dotted ones (Table 4 ).

The final model with regression weights and path coefficients

For the statistically significant findings, varying effect sizes were found amid the path coefficients. The highest path coefficient was from PEoU to PU, producing a total regression weight ( R 2 ) of 0.47 (p < 0.001). To a lesser degree, in the low effect size range (Cohen, 1988 ), both PEoU and PU had positive path coefficients to reported levels of attitude using video conference tools, producing a total regression weight ( R 2 ) of 0.18 (p < 0.001). PU was the strongest predictor for behavioral intentions, indicating that utility in the video conferencing system is an essential antecedent for future use. While PEoU revealed a statistically significant path to behavioral intentions to use video conferencing tools in the educational context, the path was in the low effect size range (Cohen, 1988 ). Together, PU and PEoU produced a total regression weight ( R 2 ) of 0.42 (p < 0.001) on behavioral intention to use Zoom for English conversational purposes. Regarding actual use, only PEoU and attitude produced significant path coefficients, accounting for an overall total regression weight ( R 2 ) of 0.45 (p < 0.001).

Results from post hoc analysis using a 5000-sample bootstrap revealed two instances of mediation. For every one-point increase in PEoU (on the five-point Likert scale), there was an indirect effect through PU that accounted for a 0.337-point increase in reported levels of behavioral intention to use video conference tools in the future, equating to a standardized regression weight of 0.437 ( p < 0.001). Following a similar path through PU, for every one-point increase in PEoU, there was a statistically significant indirect effect through PU that accounted for a 0.163-point increase in reported attitude with using video conference tools for conversational English classes, equating to a standardized regression weight of 0.147 ( p = 0.023). The next chapter explains these findings through the lens of past literature.

4.4 Discussion

In the current research, the Zoom video conference platform was evaluated using a modified version of the TAM. The study's model helps explain the adoption of video conference tools during the Covid-19 pandemic . For the modified TAM, actual use was substituted with perceived learning outcome as it pertains to direct participation with video conference tools. Several points of significance surfaced from our study. From the initial review of data, bivariate Pearson correlation analysis found that all variables shared statistically significant relationships with one another, which is a common emergence within TAM literature (Park, 2009 ). Once testing the structural model, a multivariate understanding of how these constructs related to one another was observed. For seven of the ten proposed hypotheses, paths were in the anticipated positive direction, adding credit to the reliable nature of the TAM's application with educational technology in general and video conference tools specifically.

4.4.1 Hypotheses 1 to 3

Hypotheses one was confirmed, indicating that perceived ease of use positively affects perceived usefulness with video conference tools , and this finding is directly in line with extant literature (Almaiah et al., 2020 ; Mohammadi, 2015 ; Sukendro et al., 2020 ). PEoU produced the highest path coefficient in the model with PU, echoing past studies in reference to LMS technology (Cheung & Vogel, 2013 ) and in line with the growing literature pertaining specifically to video conference tools for e-learning purposes (Coman et al., 2020 ). Hypotheses two, perceived ease of use positively affected attitude using video conference tools, and three, perceived usefulness positively affects attitudes towards using video conference tools , were also confirmed, supporting similar findings from recent studies (Buabeng-Andoh et al., 2019 ; Muhaimin et al., 2019 ; Sukendro et al., 2020 ). These findings indicate that Zoom's ease of use and PU in conversational English courses contribute to improved attitudes towards communication tasks, including partner and group EFL speaking activities.

4.4.2 Hypotheses 4 to 6

Hypotheses four and five confirmed that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness positively affect behavioral intentions to use video conference tools. PEoU positively affected intentions to use zoom but not at as high a level as PU, which is in line with similar TAM patterns recognized by Zhang et al. ( 2008 ) and Yang & Wang ( 2019 ). Technology that is perceived as applicable helps students (Zaharias, 2009 ), contributing to future use with the Zoom video conference platform for classroom purposes. To a lesser degree than with PU, PEoU positively affected intentions to use video conference tools in the future, and this result ties well with previous studies (Nikou & Economides, 2017 ; Sukendro et al., 2020 ; Teo et al., 2018 ).

Hypothesis six, attitude positively affects behavioral intentions with video conference tools, was rejected. A different result was obtained from previous studies wherein Saadé et al. ( 2007 ) indicated that PU has a significant favorable influence on university learners' attitude toward online environments as well as their behavioral intention to use such technology in the future. Therefore, our primary findings pertaining to attitude contradict prior research, showing that attitude was a key indicator in acceptance behavior (Alharbi & Drew, 2014 ; Cheung & Vogel, 2013 ). Reasoning for this may be attributed to the wording of the items in the in-house developed attitude scale. Students reported on their attitude towards conversational English activities delivered through Zoom, but not Zoom features specifically, which may have influenced the findings.

4.4.3 Hypotheses 7 to 10

Hypothesis seven, perceived usefulness positively affects reported learning outcomes with video conference tools, was rejected . This finding was in stark contrast to past TAM studies prior to Covid and outside the video conference context (Al-Gahtani, 2016; Chang et al., 2017 ; Lee et al., 2014 ; Tarhini et al., 2014 ). Students recognized that video conference tools had been used for e-learning purposes in general and even for EFL classes specifically. However, increased levels of perceived usefulness did not influence increased levels of perceived learning outcome with the Zoom conversational English classes under investigation here.

Next, the study revealed that hypothesis eight , perceived ease of use positively affects reported learning outcomes with video conference tools, was confirmed . When comparing our results to prior TAM studies (Gupta & Bostrom, 2013 ; Hattie & Yates, 2014 ; Janson et al., 2017 ), it must be pointed out that success in accomplishing learning goals often relies on how efficient learners perceive the learning program and their learning development. When learners have positive attitudes towards their learning development, they gain a higher level of self-efficacy and, consequently, achieve higher learning outcomes.

With the video conference technology referenced here, perceived usage, or how students reported their level of learning while participating in the video conference course, was used to define actual use in the tested TAM. PEoU positively influenced perceived levels of learning, indicating that self-efficacy with the technology regarding ease of use contributes to self-efficacy with learning expectations when using that technology. PEoU predicted learning outcomes (e.g., mastering conversational EFL activities), while PU did not. As less effort is exerted when using the e-learning tools, more time and energy can be dedicated to the learning activity, contributing to a higher likelihood of mastering the course objective. Contrarily, students who may or may not feel they are mastering the content may still judge the video conference tools as beneficial; however, this is independent of how well they perceive their performance when attending video conference courses.

Hypothesis nine, behavioral intention positively affects reported learning outcomes with video conference tools, was rejected. Behavioral intention to use video conference tools in the future did not predict actual use in the context of conversational English courses, which contrasts with extant TAM literature (Sukendro et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2008 ). Finally, hypothesis ten, attitude positively affects reported learning outcomes with video conference tools, was confirmed. This is consistent with what has been found in previous research, which found that attitude positively affected the actual use of video conference tools for e-learning purposes to offset complications brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic (Pal & Patra, 2021 ).

4.4.4 Mediation results

Through post hoc analysis, two instances of mediation were identified. Specifically, PU mediated the relationship between PEoU and behavioral intentions, repeating similar findings with video conference courses taught during the Covid-19 pandemic (Utami, 2021 ) as well as earlier TAM studies (Wu & Chen, 2017 ). Further, PU mediated the relationship between PEoU and attitude, supporting prior mediation found with the TAM among a group of MOOC students and their choice to continue to participate in their massive online course (Wu & Chen, 2017 ). If video conference tools provide critical functionality, students will have a better attitude to using them, and this perceived usefulness will equate to a better attitude and more engagement.

4.4.5 Pedagogical implications

The main practical contribution of the study is that it offers evidence from the students' perspective for the acceptance level of continuing use of video conferencing systems for teaching in the post-Covid-19 era. In addition to the added contributions to the TAM literature, evidence emerged arguing for training sessions to be organized by the administrators within universities outside the regular classroom sessions to familiarize students with the video-based learning systems and discuss possible solutions to reported challenges. Instructors should also be informed about the features, usefulness, and technical issues of the newly implemented video conferencing platform to extend their knowledge and confidence in using the system. For instance, the resolution of the delivered videos should be optimal to cater to the needs of all the students who might encounter Internet speeds and or data plan restrictions (Pal & Patra, 2021 ). Preparation sessions should be delivered to all learners reassuring the availability of mentoring and technical support to enhance their self-confidence and, thereby, positively influencing learners' technology acceptance.

Moreover, a deeper examination of teachers' and students' attitudes on specific features of Zoom's break-out rooms, whiteboards, and screen sharing would be practical to further guide the transformation from traditional in-person instructions to online multimodalities. Technology orientation and continuous support are vital factors that lead to proficient skills and a positive attitude toward the learning system to be utilized promptly and effectively. To support the users more efficiently, universities should connect video conferencing features to the specific types of learning activities performed on the conferencing platform. System designers need such information to acknowledge learners' needs during the learning process and, thus, ensure that learners receive IT support when needed. Moreover, video conferencing platforms must enhance the system's usefulness and ease of use to maximize learners' acceptance. Educational stakeholders should also consider the acceptability of the used learning platform. Therefore, it is suggested that efforts should be directed toward knowing the reasons behind why a planned platform might not be entirely acceptable and preparing for improvement actions accordingly. Collecting feedback from the users of the video conferencing platform about the accessibility issues, problems, and recommendations for improvement is essential to optimize the effectiveness of e-learning.

The study concluded that the TAM affected university students' intention to use Zoom as a learning tool. As a result, there is the possibility of practical application in the development and management of Zoom in the university context. Stakeholders, including educators and policymakers, should work to develop ongoing training for educators to improve students' ability to use Zoom, improve their skills, and increase levels of acceptance toward e-learning platforms. E-learning course instructional design, motivation, communication, and support contribute to improved learning outcomes. As we enter a post-pandemic pedagogy, innovative plans and customized lesson designs within blended learning are desperately needed.

5 Conclusion

The main conclusion drawn is that PEoU with Zoom strongly affected PU, attitude, and perceived levels of learning when using the platform. Further, PU with Zoom predicted intentions to use Zoom in the future, directly and indirectly, on the relationship between PEoU and behavioral intentions; however, PU failed to influence perceived learning outcomes in the video conference class. Therefore, while PU predicted future use, it did not influence how well students reported their current performance in their video conference course.

5.1 Limitations and future direction

There are several limitations to this study that future research can address. Some of the shortcomings include but are not limited to the fact that the data is conducted during emergency remote online classes in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The settings surrounding the transfer to, and continuation with, online instruction was not the preferred mode of educational delivery, yet allowed a unique opportunity to gauge learner perceptions, expectations, and acceptance of video conference instruction with Zoom. Next, this study did not investigate external variables such as subjective norm, perceived interaction, self-efficacy with video conference tools, or joyfulness in TAM-based models. Furthermore, future work can include user log data for the actual use of Zoom features. Another drawback of this study is the use of Zoom as the only reference platform for assessing the PU and PEoU of the online learning platforms. Comparative research should be undertaken to examine whether a difference exists between other platforms (e.g., Skype, WebEx, and Google Meet). Future research should focus on measuring two or more e-learning platforms to bring out the natural state of the art of the claimed findings.

Future research should further develop and confirm these initial findings by conducting the study in different settings and by using a triangulation of data collections (e.g., classroom observations, focus individual and group interviews, artifacts). Further, research-based on self-report or system log files of actual use of the Zoom platform should be carried out to evaluate the validity of the results with the original TAM variables. Additionally, this study targeted only students; it would be wise to implement research with instructors and professors in the university. Moreover, the geographical location of the participants (i.e., one specific country) is a point of delimitation considering the usage behavior, and thus, the perception of usability could change with culture. Therefore, future studies could replicate results in a larger and international context that includes digital equality and gender inclusion as moderators for anticipating the actual usage of video-based systems to generalize the current findings.

Video conference software has permanently made its mark as the remedy for emergency online classes. Due their success, students, instructors, and administrators will likely adopt video conference tools more frequently and for reasons beyond social distancing measures. To this end, there continues to be a clear and present need to understand how video conference features with software like Zoom are incorporated as novel and effective learning environments that help meet academic objectives.

Abdullah, F., & Ward, R. (2016). Developing a general extended technology acceptance model for e-learning (GETAMEL) by analyzing commonly used external factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 56 , 238–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.036

Article Google Scholar

Alfadda, H. A., & Mahdi, H. S. (2021). Measuring students’ use of Zoom application in language course based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 50 , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09752-1

Alharbi, S., & Drew, S. (2014). Using the technology acceptance model in understanding academics’ behavioral intention to use learning management systems. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 5 (1), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2014.050120

Almaiah, M. A., Al-Khasawneh, A., & Althunibat, A. (2020). Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies, 25 , 5261–5280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10219-y

Al-Gahtani, S. S. (2016). Empirical investigation of e-learning acceptance and assimilation: A structural equation model. Applied Computing and Informatics, 12 (1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aci.2014.09.001

Al-Samarraie, H. (2019). A scoping review of videoconferencing systems in higher education: Learning paradigms, opportunities, and challenges. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning , 20 (3). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v20i4.4037

Bong, M., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2003). Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educational Psychology Review, 15 (1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021302408382

Buabeng-Andoh, C., Yaokumah, W., & Tarhini, A. (2019). Investigating students’ intentions to use ICT: A comparison of theoretical models. Education and Information Technologies, 24 , 643–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9796-1

Bui, T. H., Luong, D. H., Nguyen, X. A., Nguyen, H. L., & Ngo, T. T. (2020). Impact of female students’ perceptions on behavioral intention to use video conferencing tools in COVID-19: Data of Vietnam. Data in Brief, 32 , 106–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.106142

Chang, C.-T., Hajiyev, J., & Su, C.-R. (2017). Examining the students’ behavioral intention to use e-learning in Azerbaijan? The general extended technology acceptance model for e-learning approach. Computers & Education, 111 , 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.04.010

Cheung, R., & Vogel, D. (2013). Predicting user acceptance of collaborative technologies: An extension of the technology acceptance model for e-learning. Computers & Education, 63 , 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.12.003

Chuttur, M. Y. (2009). Overview of the technology acceptance model: Origins, developments and future directions. Sprouts: Working Papers on Information Systems , 9 (37), 1–21. http://sprouts.aisnet.org/9-37

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

MATH Google Scholar

Coman, C., Tiru, L. G., Mesesan-Schmitz, L., Stanciu, C., & Bularca, M. C. (2020). Online teaching and learning in higher education during the Coronavirus Pandemic: Students’ perspective. Sustainability, 12 (24), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410367

Crosthwaite, P. R., Bailey, D. R., & Meeker, A. (1986). Assessing in-class participation for EFL: Considerations of effectiveness and fairness for different learning styles (2015). Language Testing in Asia, 5 (9), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-015-0017-1

Crosthwaite, P. R., Bailey, D. R., & Meeker, A. (2015). Assessing in-class participation for EFL: considerations of effectiveness and fairness for different learning styles. Language Testing in Asia, 5 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-015-0017-1

Davis, F. D. (1986). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results, [doctoral dissertation, MIT Sloan School of Management]. Cambridge, MA. Retrieved from http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/15192 .

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13 (3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Farr, F., & Murray, L. (Eds.). (2016). The Routledge handbook of language learning and technology. Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research . Addison-Wesley.

Google Scholar

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

George, D., & Mallery, M. (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple study guide and reference, 17.0 update (10 th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Granic, A., & Marangunic, N. (2019). Technology acceptance model in educational context: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access, 28 (2), 273–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12864

Gupta, S., & Bostrom, R. (2013). An investigation of the appropriation of technology-mediated training methods incorporating enactive and collaborative learning. Information Systems Research, 24 (2), 454–469.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson College Division.

Hattie, J., & Yates, G. C. R. (2014). Visible learning and the science of how we learn . Routledge.

Ho, N. T. T., Sivapalan, S., Pham, H. H., Nguyen, L. T. M., Van Pham, A. T., & Dinh, H. V. (2020). Students’ adoption of e-learning in emergency situations: The case of a Vietnamese university during COVID-19. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 17 (4), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-08-2020-0164

Jan, S. K. (2015). The relationships between academic self-efficacy, computer self-efficacy, prior experience, and satisfaction with online learning. American Journal of Distance Education, 29 (1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2015.994366

Janson, A., Söllner, M., & Leimeister, J. M. (2017). Individual appropriation of learning management systems—antecedents and consequences. AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction , 9 (3), 173–201. 10 .17705/1thci.00094

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling . Guilford Publications.

Landrum, B. (2020). Examining students' confidence to learn online, self-regulation skills and perceptions of satisfaction and usefulness of online classes. Online Learning, 24 (3), 128–146. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v24i3.2066

Lee, Y. H., Hsiao, C., & Purnomo, S. H. (2014). An empirical examination of individual and system characteristics on enhancing e-learning acceptance. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 30 (5), 561–579. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.381

Mader, C., & Ming, K. (2015). Videoconferencing: A new opportunity to facilitate learning: The clearing house: A Journal of Educational Strategies. Issues and Ideas, 88 (4), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2015.1043974

Mailizar, M., Burg, D., & Maulina, S. (2021). Examining university students' behavioral intention to use e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: An extended TAM model. Education and Information Technologies , 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10557-5

Mishra, L., Gupta, T., & Shree, A. (2020). Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research, 1 , 100012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100012

Mohammadi, H. (2015). Investigating users’ perspectives on e-learning: An integration of TAM and IS success model. Computers in Human Behavior, 45 , 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.044

Muhaimin, M., Habibi, A., Mukminin, A., Pratama, R., Asrial, A., & Harja, H. (2019). Predicting factors affecting intention to use Web 20 in learning: Evidence from science education. Journal of Baltic Science Education, 18 (4), 595–606. https://doi.org/10.33225/jbse/19.18.595

Nikou, S. A., & Economides, A. A. (2017). Mobile-based assessment: Investigating the factors that influence behavioral intention to use. Computers & Education, 109 , 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.02.005

Nunnally, J. C. (1994). Psychometric theory 3E . Tata McGraw-hill education.

Pajo, K., & Wallace, C. (2001). Barriers to the uptake of web-based technology by university teachers. The Journal of Distance Education, 16 (1), 70–84.

Pal, D., & Patra, S. (2021). University students’ perception of video-based learning in times of COVID-19: A TAM/TTF perspective. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 37 (10), 903–921. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1848164

Pal, D., & Vanijja, V. (2020). Perceived usability evaluation of Microsoft Teams as an online learning platform during COVID-19 using system usability scale and technology acceptance model in India. Children and Youth Services Review, 119 , 105535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105535

Park, S. Y. (2009). An analysis of the technology acceptance model in understanding university students' behavioral intention to use e-learning. Educational Technology & Society , 12 (3), 150–162. Retrieved July 25, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.12.3.150

Park, S. Y., Nam, M.-W., & Cha, S.-B. (2012). University students’ behavioral intention to use mobile learning: Evaluating the technology acceptance model. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43 (4), 592–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01229.x

Pituch, K. A., & Lee, Y.-K. (2006). The influence of system characteristics on e-learning use. Computers & Education, 47 (2), 222–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2004.10.007

Revythi, A., & Tselios, N. (2019). Extension of technology acceptance model by using system usability scale to assess behavioral intention to use e-learning. Education and Information Technologies, 24 (4), 2341–2355.

Saadé, R. G., Nebebe, F., & Tan, W. (2007). Viability of the technology acceptance model in multimedia learning environments: Comparative study. Interdisciplinary Journal of Knowledge and Learning Objects, 3 (1), 175–184. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/44804/

Sukendro, S., Habibi, A., Khaeruddin, K., Indrayana, B., Syahruddin, S., Makadada, F. A., & Hakim, H. (2020). Using an extended Technology Acceptance Model to understand students' use of e-learning during Covid-19: Indonesian sport science education context. Heliyon , 6 (11), online journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05410 .

Taat, M. S., & Francis, A. (2020). Factors influencing the students acceptance of E-learning at teacher education institute: An exploratory study in Malaysia. International Journal of Higher Education, 9 (1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n1p133

Tarhini, A., Hone, K., & Liu, X. (2014). Measuring the moderating effect of gender and age on e-learning acceptance in England: A structural equation modeling approach for an extended technology acceptance model. Educational Computing Research, 51 (2), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.51.2.b

Teo, T., Sang, G., & Mei, B. (2018). Investigating pre-service teachers’ acceptance of Web 20 technologies in their future teaching: a Chinese perspective. Interactive Learning Environments, 27 (4), 530–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1489290

Utami, T. L. W. (2021). Technology adoption on online learning during Covid-19 pandemic: implementation of technology acceptance model (TAM). Diponegoro International Journal of Business, 4 (1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.14710/dijb.4.1.2021.8-19

Venkatesh, V., & Bala, H. (2008). Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decision Sciences, 39 (2), 273–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.2008.00192.x

Virtič, M. P., Dolenc, K., & Šorgo, A. (2021). Changes in online distance learning behaviour of university students during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak, and development of the model of forced distance online learning preferences. European Journal of Educational Research, 10 (1), 393–411. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.10.1.393

Vladova, G., Ullrich, A., Bender, B., & Gronau, N. (2021). Students’ Acceptance of technology-mediated teaching–how it was influenced during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: A Study from Germany. Frontiers in Psychology, 12 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636086

Wu, B., & Chen, X. (2017). Continuance intention to use MOOCs: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and task technology fit (TTF) model. Computers in Human Behavior, 67 , 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.028

Yang, Y., & Wang, X. (2019). Modeling the intention to use machine translation for student translators: An extension of Technology Acceptance Model. Computers & Education, 133 , 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.015

Zaharias, P. (2009). Usability in the context of e-learning: A framework augmenting ’traditional usability constructs with instructional design and motivation to learn. International Journal of Technology and Human Interaction (IJTHI), 5 (4), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.4018/jthi.2009062503

Zhang, S., Zhao, J., & Tan, W. (2008). Extending TAM for online learning systems: An intrinsic motivation perspective. Tsinghua Science & Technology, 13 (3), 312–317.

Download references

Acknowledgment

The researchers thank Prince Sultan University for funding this research project under grant [Education Research Lab- [ERL-CHS-2022/1]. In addition, this paper was supported by Konkuk University. Further, this paper was supported by Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

English Language and Literature Department, Konkuk University’s Glocal Campus, Chungju, South Korea

Daniel R. Bailey

Linguistics and Translation, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Norah Almusharraf

College of Languages and Translation at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Asma Almusharraf

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Dr. Daniel Bailey (data collection and analysis).

Dr. Norah Almusharraf (theoretical framework).

Dr. Asma Almusharraf (report and narratives).

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Asma Almusharraf .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests statement.

Conflict of interests-None

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Bailey, D.R., Almusharraf, N. & Almusharraf, A. Video conferencing in the e-learning context: explaining learning outcome with the technology acceptance model. Educ Inf Technol 27 , 7679–7698 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10949-1

Download citation

Received : 02 November 2021

Accepted : 09 February 2022

Published : 21 February 2022

Issue Date : July 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10949-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Technology acceptance model

- Video conference

- Computer-assisted language learning

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Advertisement

- Previous Article

- Next Article

1 Introduction

2 survey methods, 3 (zoom) fatigue, 4 shortcomings of video conferencing, 5 measuring video conferencing effectiveness, 6 video conferencing solutions, 7 overview and future research, 8 conclusion, acknowledgments, the shortcomings of video conferencing technology, methods for revealing them, and emerging xr solutions.

- Cite Icon Cite

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Search Site

Dani Paul Hove , Benjamin Watson; The Shortcomings of Video Conferencing Technology, Methods for Revealing Them, and Emerging XR Solutions. PRESENCE: Virtual and Augmented Reality 2022; 31 283–305. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/pres_a_00398

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Video conferencing has become a central part of our daily lives, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, so have its many limitations, resulting in poor support for communicative and social behavior and ultimately, “Zoom fatigue.” New technologies will be required to address these limitations, including many drawn from mixed reality (XR). In this paper, our goals are to equip and encourage future researchers to develop and test such technologies. Toward this end, we first survey research on the shortcomings of video conferencing systems, as defined before and after the pandemic. We then consider the methods that research uses to evaluate support for communicative behavior, and argue that those same methods should be employed in identifying, improving, and validating promising video conferencing technologies. Next, we survey emerging XR solutions to video conferencing's limitations, most of which do not employ head-mounted displays. We conclude by identifying several opportunities for video conferencing research in a post-pandemic, hybrid working environment.

Over the recent years of the COVID-19 pandemic, a mass move toward remote work and communication has forced many to reckon with the long-term effects of video conferencing as a primary communication method. In particular, Zoom fatigue, or video conferencing fatigue, became particularly prominent during the pandemic (Fauville et al., 2021a ). Zoom fatigue is defined as physical and cognitive exhaustion resulting from intensive use of video conferencing tools (Riedl, 2021 ). Post-pandemic, most expect remote video conferencing to remain much more widely used than it was before COVID (Remmel, 2021 ), serving as both a safety precaution and a crucial enabler of a burgeoning hybrid home/office work environment as public health precautions end. Given this, understanding the challenges and opportunities of video conferencing is particularly important, both to prevent negative consequences and to realize benefits in the long term. This is especially pertinent as use of previously unconventional meeting environments, such as virtual reality, grows.

In seeking this understanding, our guiding questions are: (a) what shortcomings limited conferencing effectiveness prior to the pandemic and how do they contribute to Zoom fatigue, (b) what solutions have addressed these shortcomings and might ease Zoom fatigue in the post-pandemic hybrid working environment, and (c) what potential do nontraditional conferencing interfaces, such as XR, have to address these same shortcomings?

Toward this end, we survey research and opinion on video conferencing across several disciplines, both technical and social, and across several technologies, including traditional interfaces as well as mixed and virtual reality. We focus on video conferencing's shortcomings and evaluative methods for finding them, as defined both pre- and post-pandemic. We give particular attention to the cognitive and technological factors that contribute to Zoom fatigue, which emerged during the pandemic. Finally, we survey the emerging solutions that address known shortcomings, including several in VR and XR.

With this survey, we aim to provide future researchers with a foundation enabling video conferencing improvements reducing Zoom fatigue, especially in the post-pandemic, hybrid working environment.

Our survey fits within the narrative review framework, defined as a qualitative method seeking to describe current literature, without quantitative synthesis (Shadish et al., 2001 ). Given the limited literature on video conferencing over the past decades and the recent drastic increase in its use, video conferencing research is still nascent. For this reason, we turned to this narrative review method, which “describes existing literature using narratives without performing quantitative synthesis of study results” (Lam et al., 2011 ). Two examples of this sort of survey include Lam et al. ( 2011 ) and Perer and Schneiderman ( 2009 ).

We sought to survey references describing video conferencing systems and challenges, as well as the human behavior they sought to support and methods for evaluating that support. To collect references, we therefore first searched Google Scholar for material using the keywords “zoom fatigue,” “fatigue,” “video conferencing,” or “gaze awareness.” For references older than 2015, we set a threshold of 10 citations for acceptability, to restrict our survey to work that had had at least minimal impact, when there had been time for the research community to respond. The initial search returned approximately 180 papers. Both authors then examined each paper, discarding any that they agreed did not discuss video conferencing, communicative behavior, or methods for measuring and evaluating that behavior. We then studied the bibliographies of each remaining paper, examining any cited paper with a title that contained our search keywords, and discarding any that we agreed did not meet our inclusion criteria. We were left with 65 papers.

We next categorized these references using an iterative open coding (Creswell, 2014 ) methodology that began with three labels reflecting our concerns as we began our survey work: Measures , or methods for evaluating video conferencing success; Shortcomings, or weaknesses of video conferencing solutions; and Fatigue , or the general feeling of exhaustion that many report feeling after video conferencing. Within the Measures label, our sub-labels were technical , objective methods of measurement; behavioral , observational and experimental methods capturing human use; and subjective , methods that asked users to offer their judgments of video conferencing systems. Within the Shortcomings label, our sub-labels were delay , the lag users encounter between the moment they act and the moment that act is displayed to other conference participants; and gaze , the degree to which a system communicates where users are looking. Finally, with the Fatigue label, we used a zoom sub-label to mark discussion of fatigue in the context of video conferencing, and a general sub-label to indicate discussion of fatigue more generally.

As we iterated through the papers we found, we proposed additional labels and sub-labels, and adopted them if both authors approved. To the Shortcomings label, we added an objects of discussion sub-label referring to video conferencing support for referencing items of participant interest, and a nonverbal cues sub-label marking support for nonverbal communicative signals beside gaze and discussed objects. We also added a Focus label, referencing the type of knowledge a paper contains, with the sub-labels solution for an engineering improvement to video conferencing systems, new measures for methods of measuring communicative behavior; review for a survey of video conferencing research or communicative behavior, and study for an experiment examining communication in conferencing systems.

A Table Categorizing the Research Reviewed in This Paper, by Type of Evaluation Measure, Video Conferencing Shortcoming, Type of Fatigue, and Whether the Paper Describes New Solutions, New Evaluative Measures, or Is a Survey of Other Work

The pandemic has drastically increased the use of video conferencing, resulting in the widespread experience of what has come to be called “Zoom fatigue.” In this section, we first review recent popular literature addressing Zoom fatigue. Next, 0 we investigate research literature on the general phenomenon of fatigue (Table 1 , Fatigue, General Fatigue column), and Zoom fatigue itself (Table 1 , Fatigue, Zoom Fatigue column): specifically, its definition, measurement, and analyses of its components.

3.1 Recent Expert and Popular Opinion

The massive increase in the use of video conferencing during the pandemic created a rush of opinion about video conferencing's shortcomings, many focusing on apparent long-term consequences. The phrase “Zoom fatigue” was quickly coined (Sklar, 2020 ; Fosslien & Duffy, 2020 ; Degges-White, 2020 ; deHahn, 2020 ; Rosenberg, 2020 ; Robert, 2020 ), referring to a lasting fatigue born from the unique stresses of remote work using video conferencing (this phrase has become a standard, despite the existence of many video conferencing alternatives). A number of possible causes have been suggested. These include physical issues , related to the bad ergonomics of turning a freely moving, immersive meeting into a constrained event passing through a small rectangle (Degges-White, 2020 ); and emotional issues , like the turmoil and isolation of a pandemic (Degges-White, 2020 ). But most thinking has dwelled on nonverbal and social cues , including poor eye contact and seeming inattentiveness (Degges-White, 2020 ), “constant gaze” with a gallery of other faces creating the perception of being watched (Rosenberg, 2020 ; Jiang, 2020 ) (Bailenson, 2020 ), deficiency of gesture that requires a draining hyper-focus to pick up the little body language that remains (Hickman, 2020 ; deHahn, 2020 ), “big face,” in which faces appear larger than they would at a comfortable interpersonal distance (Bailenson, 2021 ), and poor backchanneling, which makes it harder to recover from misunderstandings and attentional lapses (Fosslien & Duffy, 2020 ; Sklar, 2020 ) through asides with other participants. Appropriately, much of this popular conjecture has been investigated through formal research.

3.2 Defining and Measuring Zoom Fatigue

Fatigue is “an unpleasant physical, cognitive, and emotional symptom described as a tiredness not relieved by common strategies that restore energy. Fatigue varies in duration and intensity, and it reduces, to different degrees, the ability to perform the usual daily activities” (Aaronson et al., 1999 ). When measuring subjective fatigue, “(1) There was found to be a high correlation between the frequency of complaints of fatigue and the feeling of fatigue; (2) The amount of feeling of fatigue is different for the type of symptom” (Yoshitake, 1971 ). These considerations should apply to Zoom fatigue, which is currently measured subjectively (Nesher Shoshan & Wehrt, 2021 ).

A diagram depicting Riedl's hypothesis for a conceptual model of what factors contribute to Zoom Fatigue, adapted from Riedl's study ( 2021 ).

3.3 The Components of Zoom Fatigue

Video conferencing delivers several types of information not present in face-to-face meetings, creating a stressful information overload. Much of this information is delivered nonverbally, as indicated by Figure 1 . One study suggests that nostalgia for a time before the pandemic may contribute to Zoom fatigue (Nesher Shoshan and Wehrt, 2021 ), but most thought points toward causes present prior to the COVID-19 crisis. The prominence of self-video in video conferencing has led to a rise in facial dissatisfaction, or mirror anxiety (Fauville et al., 2021b ), with some cases extending into “Zoom dysmorphia,” driving an increase in plastic surgery (Gasteratos et al., 2021 ), particularly among women (Ratan et al., 2021 ). Hyper-gaze from a grid of staring faces is yet another informational challenge (Fauville et al., 2021b ). On the other hand, much of the information normally present in person is missing in video conferencing: the combination of “being physically trapped” in front of the screen and “the cognitive load from producing and interpreting nonverbal cues” (Fauville et al., 2021b ) makes referencing a common context and creating shared attention and connection difficult. Academic classrooms and workplaces, marked by a high frequency and intensity of video conferencing, were shown to exacerbate Zoom fatigue, as did factors such as lower economic status, poor academic performance, and unstable internet connections (Oducado et al., 2021 ).

Yet video conferencing users need not wait for technological upgrades to reduce their fatigue. Bennett et al. ( 2021 ) offer a number of recommendations for reducing Zoom fatigue, as illustrated in Table 2 . Concrete recommendations include better meeting times, improved group belongingness, and muting microphones when not speaking; less certain recommendations include turning off webcams, using “hide self” view, taking breaks, and establishing group norms.

A Table Explaining Recommendations for Reducing Video Conference Fatigue, Adapted from Figure 6 of Bennett et al.’s ( 2021 ) Study on Video Conference Fatigue

Video conferencing has been with us for nearly a century (Peters, 1938 ), and research on its limitations predates the pandemic by decades. While research on video conferencing's long-term effects is sparse, researchers did investigate many of the same shortcomings studied by Zoom fatigue investigators such as Riedl et al. ( 2021 ). We group the most relevant work into projects addressing problems with delay, gaze, objects of discussion, and a variety of nonverbal conversational cues.

Delay (lag) remains one of the most widely researched of video conferencing's technical shortcomings (Table 1 , Shortcomings, Delay column), and was represented in 12 out of 21 papers within the Measures, Technical column in Table 1 . Delay for video conferencing is defined as the time elapsed between the moment of input (e.g., a joke or a smile) and the resulting response (e.g., a retort or a laugh): “glass-to-glass.” As a factor often outside the control of users, the majority of research compares delay's quantitative severity against its qualitative effects. VideoLat is one system for measuring glass-to-glass video conferencing delays (Jansen & Bulterman, 2013 ). Users display a QR code to the camera, and compare the times that it is detected by the camera and displayed on an output monitor. We discuss more tools for measuring delay in Section 5.1 .

A Table Illustrating Turn-Taking in a Collaborative Puzzle Task, Adapted from Gergle et al.’s study ( 2012 )

In addition to disrupting conversation and its general quality, video conferencing delay has emotional effects. Delays over 100 ms have impacted user feelings of “fairness” in competitive events hosted on video conferencing, like a quiz game scenario (Ishibashi et al., 2006 ), with perceived fairness degrading as delay increases. Symmetrical and asymmetrical delay of 1200 ms has caused users to mistakenly attribute technical issues to personal shortcomings (Schoenenberg et al., 2014 ; Schoenenberg, 2016 ), where users were likely to feel that delayed conversational partners were inattentive, undisciplined, or less friendly.

Because it is largely a technical problem, delay's effects are difficult for users to solve themselves. For example, reducing video quality may reduce delay, but it also reduces visual communicative cues. These studies confirm that even a fraction of a second (100–500 ms) of delay can create conversational challenges. However, most of these studies examined only single video conferences. We suspect that, over several conferences (i.e., a fairly typical day of post-pandemic hybrid or remote work), even less delay (<100 ms) may suffice to increase the cognitive effort Riedl et al. ( 2021 ) include in their model, and create Zoom fatigue.

Gaze awareness is the ability to identify what—or importantly, who—a person is looking at. The majority of papers offering video conferencing solutions we reviewed (see Table 1 , Focus/Solution column) addressed gaze. These investigations are especially important, given that few of today's common video conferencing systems can effectively depict gaze. In the real world, our view of a conversational partner and their view of us correspond. However, in video conferencing systems, because camera and display are rarely colocated, this correspondence is broken. Even minor offsets in camera and display can notably affect our ability to recognize whether we are being looked at (Grayson & Monk, 2003 ). Gaze depiction becomes even more problematic as the number of conference participants grows: one camera cannot colocate with many participants. Yet when gaze can be effectively communicated by video conferencing, it has notable effects, especially in light of the importance of eye contact in mediated communication (Bohannon et al., 2013 ).

An illustration of how GA Display creates gaze awareness in its video conferencing solution, adapted from Monk et al.’s study ( 2002 ).

The importance of gaze has resulted in a number of solutions in addition to GA Display and Multiview, which focus more on engineering the solutions themselves than on understanding the importance of gaze (Edelmann et al., 2013 ; He et al., 2021 ; Lawrence et al., 2021 ). We discuss these in more detail in Section 6 . Gan et al. ( 2020 ) use ethnographic methods to study an underserved use of video conferencing, in which maintaining gaze is central: three-party video calls wherein one participant (e.g., a child) is less able to manage the technology, so that another (e.g., a grandparent) must help them speak with the third participant (e.g., a parent). They identify a range of needs for future video conferencing solutions to address.

Although few existing video conferencing solutions rely on it (e.g., D'Angelo & Begel, 2017 ), gaze tracking may play an important role in maintaining gaze awareness in the future. Fortunately, gaze tracking technology is already quite effective and quickly becoming more so: recent systems have achieved a refresh rate of 10,000 Hz using less than 12 Mbits of bandwidth (Angelopoulos et al., 2021 ), or even power draws as low as 16 mW that are still accurate to within 2.67° while maintaining 400-Hz refresh rates (Li et al., 2020 ). Power and refresh rate concerns are especially important for XR headsets, in which power and latency can hinder not only eye-tracking effectiveness, but general comfort. Headset-less solutions to video conferencing will likely mandate sophisticated gaze tracking on top of other tracking technologies.

Like delay, lack of video conferencing support for gaze likely contributes to Zoom fatigue. As seen in Figure 1 , lack of eye contact likely engenders a lack of shared attention, which in turn increases the cognitive load of video conferencing. Given the growing availability of inexpensive cameras and gaze tracking solutions, support for gaze may offer a widely applicable salve to long-term fatigue.

4.3 Objects of Discussion

Conversation often centers around a shared object, such as a whiteboard diagram, a presentation, or a working document. In such cases, discussion is filled with shorthand “deictic” references that make use of the object's context like “that one,” “to the left of” and with pointing, “over there.” Facilitating such conversational grounding has been particularly important for improving performance on shared tasks during video conferencing. Objects of discussion are an important part of shared attention and the papers we review (Table 1 , Shortcomings, Object column), and a large portion of the papers that offer novel video conferencing solutions. With their ability to overlay virtual objects onto real world views, XR and AR are uniquely equipped to address this issue.

An illustration of how Remote Manipulator operates, provided courtesy of Feick et al. ( 2018 ).

With their ability to overlay virtual objects onto real-world views, XR and AR may be uniquely equipped to provide the grounding conversational context of objects of discussion. We could not find research examining support for objects of discussion in video conferencing over the long term, but expect that like reductions in delay and support for gaze, it may improve the quality of communication and lower Zoom fatigue.

4.4 Additional Nonverbal Cues

In addition to gaze and objects of discussion, a variety of other nonverbal cues play an important role in conversation and are not commonly well-supported by existing conferencing systems, including spatial location, gesture, facial expression, and body language (Table 1 , Shortcomings, Other Cues column). While none of these individual shortcomings is a dominant theme, collectively these shortcomings form a significant portion of the literature we review.

Gesture and expression are particularly important in speech formation and clarity, and have aided understanding in collaborative tasks (Driskell & Radtke, 2003 ; Driskell et al., 2003 ). Early studies confirmed the value of video in delivering such nonverbal cues, with video conferencing supporting more natural conversations as measured by improved turn taking, distinguishing among speakers, and better ability to interrupt/interject (Whittaker, 2003 ). When compared with audio-only solutions, video conferencing not only increased perceived naturalness, but also mitigated the impact of delays up to 500 ms (Tam et al., 2012 ). Emphasizing the importance of visuals, Berndtsson et al. ( 2012 ) found that it was more important to synchronize audio and video than to reduce audio delays. This was true even at delays lower than 600 ms (Berndtsson et al., 2012 ), with users preferring video conferencing over audio-only communication. In a virtual reality system without video, the introduction of more facially expressive avatars not only increased presence and social attraction, but also increased task performance (Wu et al., 2021 ).