Laurence Olivier

Laurence Olivier was one of the most acclaimed actors of the 20th century, known for his roles in numerous Shakespeare productions on stage and screen, as well as memorable turns in more modern classics.

(1907-1989)

Who Is Laurence Olivier?

Laurence Olivier was one of the most acclaimed actors of the 20th century. He is known for his career-defining performances of Shakespearean roles on stage and screen, as well as memorable turns in modern classics such as Wuthering Heights and Marathon Man . He was knighted by King George VI and later made Baron Olivier of Brighton by Queen Elizabeth II, who also gave him the Order of Merit. Outside of his acting career, Olivier is remembered for his love affair and tempestuous marriage to actress Vivien Leigh.

Laurence Kerr Olivier was born in Dorking, in Southern England, on May 22, 1907, to a strict religious family. Both his father and grandfather held prominent positions in the Anglican church; his mother too came from a family of career clerics, but she was his solace in the rigid household run by his father. As the youngest of their three children, Olivier was shattered when his mother died in 1920 when he only 12 years old. But despite his father's severity, it was he who encouraged Olivier, also known to the family as Kim, to pursue acting as a career after Shakespearean roles at school showcased his early talent.

Stage Career: Hamlet and Othello

Olivier enrolled at the Central School of Speech and Drama and followed theatrical tradition, joining the Birmingham Repertory company. He rose quickly from spear-carrier to leading man and soon moved to London's West End. An early theatrical success came with the debut of Noel Coward's Private Lives , which was quickly followed by a bold production of Romeo and Juliet , in which Olivier and John Gielgud alternated playing Romeo and Mercutio. The two actors, whose styles clashed, remained lifelong rivals.

Olivier made his mark with star turns in many of Shakespeare 's leading roles, including those of Hamlet, Henry V, Anthony, Richard III, Macbeth and Othello, and Leigh often appeared as his leading lady, making the couple, who married in 1940, London theater royalty. The couple also toured and appeared in the United States, capitalizing on her popularity from Gone With the Wind 's wild success. He was known to experience crippling stage fright, even as a seasoned actor.

After the demise of their marriage due to Leigh's battle with manic depression, Olivier made a career departure: He starred in John Osborne's The Entertainer , marking a turn in his life and acting approach. Helping to establishing the Royal National Theatre, Olivier became its founding director, serving from 1962 to 1973.

Film Career

Olivier's first forays into film were faltering, but he hit his stride as Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights and Rebecca , which catapulted him to matinee idol status—and helped fund his theatrical ventures. He also put to film some of his most famous Shakespearean roles, winning his first Academy Award (best actor in a leading role) and a second nomination (best director) for Hamlet .

Nevertheless, later in his career, Olivier took almost any role offered for the paycheck so that he could provide for his family. In addition to son Tarquin from his first marriage, he and his third wife, actress Joan Plowright, had three children together, son Richard and daughters Tamsin and Julie Kate. But Olivier went on to reclaim his reputation with acclaimed roles, including that of the Nazi dentist in Marathon Man . He received a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Academy in 1979.

Death and Legacy

Olivier published his autobiography, Confessions of an Actor , in 1984. Olivier, who has long been rumored to have had a sexual dalliance with actor Danny Kaye, admitted in his autobiography that he was tempted but never followed through with establishing a relationship with Kaye. Biographer Terry Coleman also dismissed this rumor in his 2005 work Olivier . He did, however, believe that Olivier may have been involved with actor Henry Ainley. Olivier's family has disputed this claim.

Following a decade's battle with cancer and related illnesses, Olivier died on July 11, 1989, at his home in West Sussex, England, just outside London. Olivier is one of the few actors to be buried in Westminster Abbey's esteemed Poet's Corner. The honor is fitting for the youngest actor to be knighted—at age 40, by King George VI —and the first to be elevated to the peerage—in 1970, by Queen Elizabeth II . Elizabeth II dubbed him Baron Olivier of Brighton, which allowed him to sit in the House of Lords; she later bestowed upon him the Order of Merit. The Olivier Awards, England's equivalent of the Tony's, are named in Olivier's honor.

Fifteen years after his death, Olivier starred as the villain in 2004's Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow through the magic of computer graphics. British theater critic Kenneth Tynan said of Olivier: "He's like a blank page and he'll be whatever you want him to be. He'll wait for you to give him a cue, and then he'll try to be that sort of person."

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Laurence Olivier

- Birth date: May 22, 1907

- Birth City: Dorking, South England

- Best Known For: Laurence Olivier was one of the most acclaimed actors of the 20th century, known for his roles in numerous Shakespeare productions on stage and screen, as well as memorable turns in more modern classics.

- Astrological Sign: Gemini

- Central School of Speech and Drama

- All Saints Choir School

- St. Edward's School

- Death date: July 11, 1989

- Death City: West Sussex, England

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

- Of all the things I’ve done in life, directing a motion picture is the most beautiful. It’s the most exciting and the nearest that an interpretive craftsman, such as an actor... can possibly get to being a creator.

- Acting is illusion, as much illusion as magic is, and not so much a matter of being real.

- Work is life for me, it is the only point of life-and with it there is almost religious belief that service is everything.

- If I wasn’t an actor, I think I’d have gone mad. You have to have extra voltage, some extra temperament to reach certain heights. Art is a little bit larger than life—it’s an exhalation of life and I think I you probably need a little touch of madness.

Famous British People

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Amy Winehouse

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Christopher Nolan

Emily Blunt

Jane Goodall

Princess Kate Is Seen for First Time Since Surgery

King Charles III

Culture History

Laurence Olivier

Laurence Olivier (1907-1989) was a distinguished English actor and director, widely considered one of the greatest actors of the 20th century. Renowned for his Shakespearean performances on both stage and screen, Olivier’s career spanned theatre, film, and television. He received numerous accolades, including Academy Awards for acting and directing. Notable works include “Hamlet,” “Henry V,” and “Wuthering Heights.” Olivier’s impact extended beyond his performances, contributing significantly to the development of British theatre and cinema.

Growing up in a family with a deep appreciation for the arts, Olivier displayed an early interest in acting. His father, Gerard Kerr Olivier, was a clergyman, and his mother, Agnes Louise Crookenden, had roots in a prosperous family. Sent to All Saints Choir School in London at a young age, Olivier’s passion for the stage blossomed as he immersed himself in theatrical productions.

Olivier’s formal acting education began at the Central School of Speech Training and Dramatic Art in London. His early performances in West End productions earned him recognition, and he joined the Birmingham Repertory Theatre in the 1920s, gaining valuable experience in a variety of roles. His stage career took a significant leap when he joined the Old Vic Company in 1931, working alongside esteemed actors like Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud.

The early 1930s marked Olivier’s emergence as a promising talent in the London theater scene. His performances in Shakespearean plays, such as “Romeo and Juliet” and “Richard III,” showcased his remarkable range and garnered critical acclaim. Olivier’s magnetic stage presence, coupled with his ability to convey the depth of Shakespearean characters, earned him widespread admiration.

Olivier’s first foray into cinema occurred in the 1930 film “The Temporary Widow,” but it was his role as Heathcliff in “Wuthering Heights” (1939) that brought him international recognition. His performance as the brooding and passionate Heathcliff earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor, establishing him as a leading actor in the film industry.

The outbreak of World War II interrupted Olivier’s burgeoning film career, and he served in the Royal Navy. Despite the challenges of the war, Olivier continued to act and direct in various productions, including the film “Henry V” (1944), which he directed and starred in. The film, a patriotic and cinematic adaptation of Shakespeare’s play, received critical acclaim and marked a turning point in Olivier’s career.

Post-war, Olivier’s contributions to British cinema reached new heights. His performance in “Hamlet” (1948), which he also directed, earned him the Academy Award for Best Actor, making him the first actor to win an Oscar for a Shakespearean role. Olivier’s interpretation of the complex Danish prince showcased his mastery of both stage and screen, solidifying his reputation as a preeminent actor and director.

In the following years, Olivier continued to distinguish himself in both classical and contemporary roles. His roles in films like “Richard III” (1955), “The Entertainer” (1960), and “Sleuth” (1972) demonstrated his versatility and commitment to challenging, diverse characters. Olivier’s ability to seamlessly transition between classical and modern roles underscored his status as a consummate actor.

Beyond his achievements in film, Olivier’s impact on the stage remained profound. In 1963, he became the first artistic director of the National Theatre in London, a position he held for a decade. Under his leadership, the National Theatre established itself as a leading institution for classical and modern productions, nurturing new talents and fostering a vibrant theater community.

Olivier’s contributions to the arts were not limited to acting and directing. He also delved into producing, and his company, Woodfall Film Productions, played a pivotal role in the British New Wave cinema movement of the 1960s. Films like “Look Back in Anger” (1959) and “Tom Jones” (1963), produced by Olivier’s company, reflected a new, gritty realism in British cinema.

Despite his numerous accolades, Olivier faced personal challenges, including health issues and struggles with his mental well-being. His dedication to his craft sometimes led to physical and emotional strain, but his unwavering commitment to excellence remained undiminished. Olivier’s personal life also attracted public attention, particularly his relationships and marriages, including his high-profile marriage to actress Vivien Leigh.

As the years passed, Olivier continued to contribute to the arts, receiving numerous honors and awards. His knighthood in 1947 was followed by a life peerage in 1970, granting him the title of Baron Olivier of Brighton. He was also bestowed with the Order of Merit, one of the highest honors in the United Kingdom, in 1981.

Laurence Olivier’s final film appearance was in “War Requiem” (1989), a powerful anti-war film based on Benjamin Britten’s choral work. As Olivier battled health issues, his performance in the film, despite its brevity, demonstrated his enduring commitment to his craft.

On July 11, 1989, Laurence Olivier passed away at the age of 82. His death marked the end of an era, leaving behind a legacy that transcends generations. Olivier’s influence on acting and the broader landscape of performing arts remains immeasurable. His mastery of both stage and screen, coupled with his contributions to the development of the National Theatre, solidified his status as a true titan in the world of theater and film.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Lasted Stories

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

Laurence Olivier: A Life

- Episode aired 1983

A multi-award winning biography covering the life and career of actor/director Laurence Olivier. A multi-award winning biography covering the life and career of actor/director Laurence Olivier. A multi-award winning biography covering the life and career of actor/director Laurence Olivier.

- Laurence Olivier

- Melvyn Bragg

- Peggy Ashcroft

- 2 User reviews

- (as Dame Peggy Ashcroft)

- (archive footage)

- (as Sir John Gielgud)

- (as Sir Ralph Richardson)

- See all cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Did you know

- Connections Features Friends and Lovers (1931)

User reviews 2

- Nov 23, 2005

- 1983 (United Kingdom)

- United Kingdom

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Technical specs

- Runtime 3 hours

- Black and White

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- IMDb Answers: Help fill gaps in our data

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed

ADV – Leaderboard

Support American Theatre! A just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Make a fully tax-deductible donation today! Join TCG to ensure you get AT's return to print in your mailbox.

AMERICAN THEATRE

The national magazine for the american not-for-profit theatre, laurence olivier: a biography.

A review of a new look at the life and work of one of the 20th century’s most influential actors.

Share this:

Laurence Olivier: A Biography by Donald Spoto, Harper Collins, New York. 480 pp, $23 cloth.

Laurence Olivier ran, walked, hobbled, shuffled, galloped and sauntered through nearly 100 plays and 60 films in his long career—and that’s not including all the productions he directed. For his very first professional job, at the age of 18 in a music hall curtain-raiser called The Unfailing Instinct , his feet played an important part: Despite repeated warnings from cast and crew to watch out for the old-fashioned raised sill on the door, on his first entrance he tripped and went sprawling. He got a big laugh—one which, according to his autobiography, Confessions of an Actor , he never managed to top. But not for lack of trying; his first nursery performances were for his doting mother who died when he was only 12, and he continued to work for the loving acceptance of audiences all his life. Constance Cummings, appearing with Oliver when he played a character based on John Barrymore in the farcical Theatre Royal in 1934, recalled Olivier saying he would gladly break a leg to get a laugh. (As it happened, he did manage to fracture an ankle during the production.)

In the summer of 1933, Oliver’s first unsuccessful trip to Hollywood ended when Greta Garbo dismissed him after a bad screen test. Sulking, Olivier took his first wife, actress Jill Esmond—whose film career was doing nicely, thank you—to Honolulu for a holiday. Olivier broke a toe surfboarding.

He sprained his ankles a few times, once memorably during World War II while filming Henry V in Ireland, when he demonstrated to the local extras how to leap in ambush upon a mounted rider from a tree. But these same ankles managed to support his whole body weight night after night, when in the grand climax of his stage Coriolanus in 1959, Olivier was dangled upside down, like Mussolini. Eventually he tore cartilage in his knee (aggravating an old wound suffered while playing Richard III on tour in Australia years earlier) and was replaced by his understudy, Albert Finney.

Bare feet were key to the development of Olivier’s pantherlike walking style for Othello—one of his most elaborate and hailed characterizations at the National Theatre, which he founded and ran from 1963 to 1974. Crucially, he exploited a “flaw” in the Moor’s character—pride—that had been traditionally neglected in productions where Othello was little more than Iago’s stooge. As he recalls in his windy but fascinating book, On Acting : “Black…I had to be black…I had to look out from a black man’s world…A walk…I needed a walk. I must relax my feet. Get the right balance, not too taut, not too loose…I took off my shoes, then my socks. Barefoot, I felt the movement come to me. Slowly, it came: lithe, dignified, and sensual. Lilting, yet positive.”

Olivier hated his legs, which he thought “spindly” and so disguised them with padding under tights. He tore a calf muscle when, as Macheath in a 1952 film of the The Beggar’s Opera , he leaped onto a gaming table. More spectacularly, his calf was pierced with an arrow during filming of Richard III the next year; Olivier, who was also directing, insisted that the take be completed before the arrow was removed.

In one of his early films, Fire Over England , a costume romance which co-starred Vivien Leigh (his lover but not yet his second wife), Olivier’s habit of bravado on the set was equally dangerous. As Donald Spoto describes it in his new biography:

For a hazardous scene, Olivier insisted on performing his own stunts, as usual, as Vivien stood by, admiring. He was to spring aboard the studio galleon and throw a flaming torch along the oil-soaked floor, leaping over the side of the ship into a safety net below as the deck burst into flames…Olivier jumped and tossed the firebrand, but the flaming oil floated on the water and sped towards him. Making a swift but crooked dive overboard, he landed precariously on the net below, merely wrenching his back instead of breaking his neck or sustaining severe burns. To everyone’s astonishment and against the producer’s wishes, Olivier then insisted on doing numerous retakes.

Mercilessly self-regarding in the manner of all actors, Olivier pronounced: “As a child I was a shrimp, as a youth I was a weed—a miserably thin creature whose arms hung like wires from my shoulders.” At his full height, Olivier was 5′ 10″ and slender; when he played his first Hamlet in 1934, his waistline was 30 inches. In that production, Olivier made his Laertes (Michael Redgrave) very nervous, constantly taking chances in the duelling scene; by the time the production closed, Olivier had chunks of flesh nicked out of his scalp, arms and chest. Directing the film in 1947, Olivier again commanded his Laertes (Terrence Morgan) to lunge forcefully in the duel. Olivier was pierced in the chest and blood spurted, to everyone’s horror—fortunately it was only a flesh wound. Later, while filming Hamlet’s 15-foot leap down upon Claudius, Olivier jumped spread-eagle with such ferocity that the stunt double was knocked unconscious and lost two teeth.

More than any other single role or production, it was Olivier’s film of Henry V that made him a star. It was a stunning piece of wartime propaganda for the British cause, a heroic full-throttle acting job and an astonishingly imaginative piece of filmmaking that also happened to be Olivier’s directing debut. Once, while he was looking through the viewfinder to set up a shot, the (big, new) Technicolor camera fell on Olivier, dislocating his shoulder and tearing open his upper lip. The scar left by the stitches was subsequently often disguised by a moustache.

The actor Michael Gambon, who was a junior player at the National Theatre during Olivier’s tenure, has said: “I love his hands. He had a particular way of holding them, bent at the knuckle.”

Anthony Quinn, appearing with Olivier on Broadway in the 1960 Becket, was startled by his fellow actor’s tongue-loosening exercises backstage.

Olivier’s voice, often described as “silvery,” was his first ticket to performing. As a small boy, he auditioned for All Saints, a choir school, where he received a scholarship for an education his minister father would not otherwise have been able to afford. His adult voice was a tenor. Kenneth Tynan, who was Olivier’s literary adviser at the National, remembered:

I passed the news [that Olivier was to play Othello] to Orson Welles, himself a former Othello. He voiced an instant doubt. “Larry’s a natural tenor,” he rumbled, “and Othello’s a natural baritone.” When I mentioned this to Olivier, he gave me what Peter O’Toole has expressively called “that grey-eyed myopic stare that can turn you to stone.” There followed weeks of daily lessons that throbbed through the plywood walls of the National’s temporary offices near Waterloo Bridge. When the cast assembled to read the play (3 February 1964), Olivier’s voice was an octave lower than any of us had ever heard it.

The voice was also the locus of Olivier’s only real acting problem, which beset him first in mild form during this production of Othello—stage fright. In this case, it seems to have been related to a real, though yet slight, diminution of his memory and consequent fear of forgetting his lines. But his panic attacks in the last decade of his stage career—in which the muscles of his mouth and throat became constricted—grew increasingly severe. For two years he controlled the panic with Valium, but when working on the film Sleuth in 1972, Michael Caine correctly identified Valium as (ironically) the source of his co-star’s short-term memory lapses, and convinced him to “stop the pills.”

Olivier’s face was brooding and expressive, with a strong chin and amazing eyes. As a schoolboy, he appeared as Kate in an amateur production of The Taming of the Shrew presented at Stratford, and was noticed even then. One critic praised his frown, which he described as “painted on” and then wiped off for Kate’s sunny and submissive ending. “That was my own frown!” said the actor, whose brows did tend to grow together in one thick line. He had not yet begun his years of playing with makeup and putty that characterized his performances. At 17, he auditioned for a scholarship at an acting school run by Elsie Fogarty. He received the scholarship, but also the following criticism:

“You have a weakness…here,” and she placed the tip of her little finger on my forehead against the base of my remarkably low hairline, and slid it down to rest in the deep hollow of my brow line and the top of my nose….There was obviously some shyness behind my gaze….It lasted until I discovered the protective shelter of nose putty and enjoyed a pleasurable sense of relief and relaxation when some character part called for sculptural additions to my face.

The long nose and padded hunch-back for Richard; the three layers of body makeup buffed with chiffon and the gentian violet mouth dye for Othello; the blond hair for Hamlet; the filed from teeth for Archie Rice in The Entertainer —it is tempting, as Olivier himself suggests, to see his virtuosity with this aspect of stagecraft as very much a matter of hiding behind the disguise of the role. It was Jonathan Miller, directing Olivier in a 1970 Merchant of Venice , who finally called the actor’s makeup bluff, persuading him to ditch the big Jewish nose and go for something much simpler in his portrayal of Shylock. As it happens, Olivier fixated instead on a set of false teeth. “As he wore them in rehearsals (and indeed often around the corridors to bewilder and alarm people),” recalls Miller, “it was quite clear that he’d invested some emblematic significance in these teeth. His character seemed to grow outwards, from the molars, as it were.”

As Olivier aged, he used disguise less and less—in part because, having left the stage after 1974, his work was confined to films where more subtle measures were appropriate. In A Voyage Round My Father (1981), Olivier played a blind barrister. When I saw the film, his eyes look so completely glaucous I assumed he was wearing opaque contact lenses. But I learned from the Spoto biography that, plagued by a bad memory, Olivier was in fact reading his lines from a blackboard off-camera the whole time.

Olivier felt that it was a terrible weakness for him that he never wept in character—except for once only, in a performance of Othello . His eyes, aided in age by glasses, remained sharp until his death. Ronald Pickup, another fellow actor from the National days, called them “those wonderful, deep, blazing, hypnotic eyes, full of violence and humor.”

This was the body of the actor, an instinctual genius and workhorse who, from the winter of 1936 to the spring of 1938, “learned more than twelve thousand lines of Shakespeare in a schedule of performance and rehearsal that remains perhaps unique in the history of acting” (says Spoto). He was no intellectual, and in many ways his taste—such as one can gather from his taste in drapery, in costumes, in plays, in houses and in loves—was not exactly sophisticated.

Spoto’s book gives us the whole story, hook, line and sinker. There’s stuff purely of gossip interest: Olivier’s casual 10-year affair with Danny Kaye, for instance, and the rumors that he had an affair with Tynan while the critic worked for him at the National. There’s the suggestion that his sexual anxiety with women was only briefly allayed by the first passionate years of romance with Vivien Leigh; and the disappointment when his first wife, Jill Esmond, revealed her lesbian preferences (an event occasioning one of the real howlers in this book: Spoto writes, so broadmindedly, of Esmond that “her homosexuality would not have precluded a strong maternal instinct”).

Spoto is given to fairly sunny chaise-longue psychologizing; you can practically hear the rattle of the ice cubes in his g-and-t as he declares: “The reservoir from which he drew was fed not only by his own emotional history but also by a sense of emptiness and a consequent neediness. The awareness of inadequacy was suffused by a mysterious gift.” Olivier’s life, in fact, was anything but tragic: It was long, fulfilled, successful, beloved and talented, suffused with the gallant sense of public service that led him to build a National Theatre when he could have made a great deal more money being a movie star. Spoto keeps his subject at arm’s length at all times, through triumph and sorrow; it’s an admirable even-handedness, but I suspect it was because he couldn’t actually ever like his subject. To like Olivier, one must first and foremost love his acting, and Spoto seems not only not a fan (a mercy) but not even really appreciative of what makes the creature act, and what it means to do this sort of instinctual work for 70 years.

Spoto chronicles but seems uninterested in Olivier’s rivalries—especially with other male actors, and even more especially with John Gielgud and Ralph Richardson. Yet they are central to understanding Olivier’s insecurity and consequent cruelties, which are extremely important insofar at they may have diminished his work as an actor and as a director. Olivier shows his own hand in these matters in his book On Acting (which I recommend) and in his Confessions of an Actor (which I do not); and there’s Olivier at Work , a sort of Festschrift compiled by the National Theatre after his death.

Joan Plowright, Olivier’s widow, did not participate in Spoto’s researches; revelatory of what I assume to be the biographer’s pique, she is rarely mentioned, and tellingly is described as “a plain, dark-haired, brown-eyed young woman, [with] a somewhat gauzy, flat voice.” Only a wish for revenge could have prompted such an inapt description of one of the great beauties and wizards of the English stage.

Olivier loved the role of Hamlet better than any other. His performances of that part were widely praised; unfortunately, his film of Hamlet reveals, to my taste, an insipid interpretation of the role. His Henry V, on the other hand, has been justly called a classic. Here, in his early embodiment of energy and nobility, he achieved a sort of cultural apotheosis; as Charles Laughton said to him of his performance: “You are England, that’s all.” In Richard III , and in the great performances of Olivier’s later life (those that are available on video)— The Dance of Death , The Entertainer , Long Day’s Journey Into Night and King Lear— Olivier continued to embody England, an England in decline. Those raging, lionlike performances lampoon at the same time they embody the tyrannies of the empire and the patriarchy. They are indispensable artifacts of the history of acting and the history of a people.

April Bernard is the author of a novel, Pirate Jenny (Norton), and a book of poems, Blackbird Bye Bye (Randon House).

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by making a donation to our publisher, Theatre Communications Group. When you support American Theatre magazine and TCG, you support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism. Click here to make your fully tax-deductible donation today!

ADV – Billboard

©2024 Theatre Communications Group . All rights reserved.

- Entrances & Exits

- In Memoriam

- Approaches to Theatre Training

- Production Notebook

- Know a Theatre

- Theatre History

- Winter 2024 Issue

- Theme Packages

- The Subtext

- Theatrical Mustang

- Advertise in PRINT and/or DIGITAL

Sign up for the American Theatre newsletter

Get our latest U.S. theatre coverage sent directly to your inbox each week, and our roundup of theatre education content each month.

Sir Laurence Olivier, English Film and Shakespearean Actor

Universal / Getty Images

- Musical Theater

- Stand Up Comedy

Sir Laurence Olivier (May 22, 1907—July 11, 1989) ranks as one of the top British actors of the 20th century. He is particularly well-remembered for appearing in and directing Shakespearean plays both on stage and in film. His 1948 movie Hamlet was the first non-American production to win the Oscar for Best Picture.

Fast Facts: Sir Laurence Olivier

- Born : May 22, 1907 in Dorking, Surrey, England

- Died : July 11, 1989 in Steyning, West Sussex, England

- Occupation : Actor

- Spouses: Jill Esmond, Vivien Leigh, Joan Plowright

- Children: Tarquin, Julie Kate, Tamsin, Richard

- Selected Films : Wuthering Heights (1939) , Hamlet (1948) , Sleuth (1972)

- Key Accomplishments: U.K. knighthood (1947) , Best Actor Academy Award for Hamlet (1948), and Lifetime Achievement Academy Award (1979)

- Famous Quote : “I take a simple view of life: keep your eyes open and get on with it.”

Early Life and Career

Born in the market town of Dorking, Surrey, in southeastern England, Sir Laurence Olivier grew up the son of an Anglican priest. In 1916, at age nine, he passed a singing audition and was admitted to the choir school of All Saints, Margaret Street church in central London. Appearing in the school's production of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar the following year, he drew the attention of Ellen Terry, one of the greatest British Shakespearean actors of the era.

After a series of successes in school productions, Olivier's father encouraged him to pursue acting as a profession. In 1926, he joined the Birmingham Repertory Company, one of the top theatre companies in England. After building his reputation as a top young actor, two momentous events occurred in Olivier's life in 1930.

Early in the year, Sir Laurence Olivier traveled to Berlin to appear in two minor films. He did not enjoy working in movies, but it paid better than much of his theatre work. Later in the year, the legendary playwright Noel Coward cast Olivier in his new play Private Lives during its London debut. It was his first successful stage appearance in London's West End, and he traveled to New York to appear in the Broadway opening of the play in 1931.

English Stage Star

After dabbling with film acting in the U.S. in the early 1930s with little success, Sir Laurence Olivier returned to England and the stage. He joined the Old Vic company in 1936. Among his colleagues at the company were acting legends Dame Edith Evans, Ruth Gordon, Alec Guinness, and Michael Redgrave. In 1937, the group performed Hamlet at Elsinore, the castle in Denmark that Shakespeare picked as the play's setting. It began a tradition of Elsinore performances that have featured such renowned actors as Richard Burton , Kenneth Branagh, and Jude Law.

The Old Vic company survived World War II by touring England with a small entourage after the German bombing of London left their theatre severely damaged. Olivier took on the duties of co-director of the company in 1944. Among his roles was the lead in Shakespeare's Richard III , widely considered one of the best acting performances of his career. The Old Vic company toured Germany in 1945 producing plays for the victorious Allied military forces stationed there. By 1949, the company was world famous, but Olivier was exhausted. By the end of the year, he left to become an independent actor-manager.

In the 1950s, Sir Laurence Olivier found himself a star of both stage and screen. He balanced Shakespearean productions with contemporary plays. In 1957, he starred in the Wet End production of John Osborne's The Entertainer . It received tremendous acclaim, and Olivier later earned an Oscar nomination for his 1960 film version.

In 1963, with the support of the British government, the National Theatre presented its first production of Hamlet starring Peter O'Toole and Sir Laurence Olivier as the company's first director. He remained in charge of the company for a decade, directed eight plays and acted in thirteen. His first lead role at the National Theatre was a 1964 production of Othello, widely celebrated as one of his best.

Hollywood Success

Sir Laurence Olivier appeared in a series of films in both Hollywood and the U.K. in the early 1930s, but none of them brought him significant success. Offered a salary of $50,000, he agreed to travel back to Hollywood in 1939 to appear in an adaptation of the romantic novel Wuthering Heights . The result was one of his most celebrated movie performances and his first Oscar nomination for acting. His film success continued in 1940 with the starring role in Alfred Hitchcock's Best Picture-winning Rebecca .

World War II disrupted Olivier's film career, but he did appear in movies that helped the British propaganda effort. At the behest of the British government in 1944, Olivier directed and starred in a film production of Shakespeare's Henry V. It was a rousing critical and commercial success, earning Oscar nominations for Best Picture and Best Actor but winning neither.

Three years later, Sir Laurence Olivier achieved arguably his greatest success in film. He directed and starred in 1948's Hamlet . Shakespeare's play was trimmed to focus more on relationships than politics. Critics and audiences applauded the effort, and the movie became the first non-American production to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. Olivier also won the Best Actor award.

Olivier completed two more Shakespearean film productions that earned him Oscar nominations for Best Actor. In 1954, he brought Richard III to the screen with fellow knighted actors Sir Cedrick Hardwicke, Sir John Gielgud, and Sir Ralph Richardson. The National Theatre's production of Othello appeared as a movie in 1965 and earned a total of four Oscar nominations including Best Actor.

Later Career

Two of Sir Laurence Olivier's most revered movie appearances came late in his career. In 1972, on leave from the National Theatre, he co-starred with Michael Caine in the film version of the stage play Sleuth . Both lead actors earned Oscar nominations. He took on the role of a Nazi torturer in 1976's Marathon Man . Amid strong critical reviews, he received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor.

Illness plagued the last two decades of Olivier's life, and in the 1970s and 1980s, acting became increasingly difficult, but he continued to work. Extending his performances to TV, he earned Emmy Awards for a 1973 production of Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night , Love Among the Ruins , a 1975 romantic comedy with Katharine Hepburn , and 1981's Brideshead Revisited . In 1978, he earned his ninth Oscar nomination, appearing as a Nazi hunter in The Boys From Brazil .

Marriage to Vivien Leigh

In 1936, while married to his first wife, Jill Esmond, Sir Laurence Olivier met fellow actor Vivien Leigh and began an affair. She was married to Leigh Holman. They co-starred as lovers in the 1937 film Fire Over England . The pair hoped to appear together in Wuthering Heights , but Vivien Leigh was rejected. Instead, she sought out and secured the role of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone With the Wind .

In 1940, both Olivier and Leigh divorced their spouses and they married late in the year. In 1948, the couple embarked on a tour of Australia and New Zealand with the Old Vic company. There, Sir Laurence Olivier claims that he "lost" his wife when she began an affair with actor Peter Finch. When they returned to London, despite the affair, Olivier hired Finch, and he continued his relationship with Vivien Leigh on and off for several years.

With Vivien Leigh suffering from alcoholism and the bipolar disorder that plagued much of her life, the marriage slowly disintegrated in the late 1950s. They began divorce proceedings in 1960, and Sir Laurence Olivier married his third wife, Joan Plowright, in March 1961, three months after his divorce became final.

Sir Laurence Olivier is recognized as one of the greatest performers and champions of Shakespeare's plays. He also achieved success in a wide range of additional plays and films. Historians list him alongside Sir John Gielgud and Sir Ralph Richardson as one of three of the greats of the British stage in the 20th century.

Olivier remains one of the most decorated actors in the history of the Academy Awards. His Oscar nominations span nearly forty years from 1939 through 1978. Olivier earned an honorary Oscar for Lifetime Achievement in 1978.

- Coleman, Terry. Olivier . Henry Holt, 2006.

- Ziegler, Philip. Olivier . MacLehose Press, 2014.

- 7 Classic Melodramas

- 9 Essential Richard Burton Movies

- Marlon Brando Biography

- 7 Classic Movies Starring Gregory Peck

- Biography of Sylvester Stallone: Rocky, Rambo, and Beyond

- The Life of Bela Lugosi: Hollywood's Most Famous Dracula

- 8 Classic Historical Epic Movies

- 5 Classic Movies Starring Natalie Wood

- Biography of Frank Sinatra, Legendary Singer, Entertainer

- Most Famous 16 Dancers of the Past Century

- Mel Gibson's 10 Best Movies?

- Grace Kelly

- 9 Classic War Movies

- 6 Classics Starring James Cagney

- Profile of Classical Ballerina Margot Fonteyn

- 5 Famous Arab Actors From Omar Sharif to Salma Hayek

The Guilt, Misery Behind Olivier’s Genius : LAURENCE OLIVIER; A Biography, <i> by Donald Spoto,</i> HarperCollins, $23; 387 pages

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Included among the photographs of Laurence Olivier that appear in these pages is this intriguing one: “Aged fourteen, as Katharine in ‘The Taming of the Shrew.’ ” It might be worth the price of the book just to have a look at that picture.

The grand English actress Sybil Thorndike, whose children went to the same school, saw young Laurence perform as Kate and found him to be “a perfect little bitch.” Olivier would go on to assume 121 stage roles and appear in 58 movies before his death at 82.

But to judge from Donald Spoto’s intelligent, sure-handed biography, Olivier continued to live up to Thorndike’s description, or to the male counterpart--bastard.

Olivier said he was particularly fond of his 1982 performance as King Lear because Lear is “just a selfish, irascible old bastard--so am I. It’s an absolutely straight part for me.”

That Lear, along with Olivier’s Hamlet and his famous wartime performance in the movie “Henry V,” give a permanent record of Olivier’s astonishing ability. Spoto shows that Olivier’s genius arose from a tangled mess of misery, guilt and sexual ambivalence.

After a ponderous opening enumerating Olivier’s Surrey forebears, Spoto’s book picks up speed fast. Having written biographies of Alfred Hitchcock and Tennessee Williams, Spoto has plenty of sympathy for the deprived boy who grows up to be a genius.

Olivier’s chilly genteel clerical father, Gerard, never seemed to like his son. Olivier lost his earliest, most attentive audience when his mother, Agnes (“My heaven, my hope, my entire world, my own worshiped Mummy”), died of a brain tumor when he was 12.

He was, in his own words, “a muddled kind of boy, a weakling.” Olivier continued, muddled through boarding school--appeasing bullies and sadistic teachers--and the Central School of Speech and Drama of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, where his classmates described him as disheveled and threadbare (his father stopped supporting him when he turned 17).

After a short stint with the Birmingham Repertory Company, Olivier got a big break from playwright Noel Coward, who cast him as Victor, the stolid second spouse of the capricious Amanda in “Private Lives.”

Coward, eight years older, fell in love with Olivier, but restricted his involvement to professional encouragement and making up lists of classics for the younger man to read. Along with John Gielgud, Coward comes across as a hero in this book.

Greta Garbo wanted Olivier as her co-star in “Queen Christina,” but after trying out a passionate embrace, she rejected him. Garbo’s chilly refusal came at the same time Olivier’s wife, Jill Esmond, was deciding that she would make her love life exclusively lesbian, almost. Not surprising that around this time Olivier opted for mastery in his professional life.

After seeing a Los Angeles performance of King Lear by a Stratford company, Olivier said, “Listening to the compliments flying, I came to a decision . . . . I was determined to be the greatest actor of all time.”

Olivier met Vivien Leigh, who would become his second wife, at the same time that Jill Esmond announced she was expecting a child.

Olivier’s first son, Tarquin, was born in 1936 when Olivier was 29. That same year he continued his movie career (with “Fire Over England,” an Alexander Korda swashbuckler) and launched an affair with Leigh, his co-star. Seeing Esmond and the baby on weekends and Leigh on weekdays, Olivier went back to the stage to portray Hamlet, Henry V, Macbeth, and Iago to Ralph Richardson’s Othello.

With six Shakespearean roles in 16 months, he was on his way to becoming the most famous actor of his time, if not indisputably the greatest actor of all time. From winter, 1936, to spring, 1938, he learned more than 12,000 lines of Shakespeare, while deciding to leave his wife and marry Vivien Leigh.

Back in Hollywood, Olivier played Heathcliff in William Wyler’s “Wuthering Heights.” He was passed over for an Oscar, while Vivien, as Scarlett in “Gone With the Wind,” won the best actress award. But at the time, Olivier felt superior to movies; he had opined to Wyler, “I suppose this anemic little medium cannot recognize great acting.”

When he and Leigh got together to do “Romeo and Juliet” on Broadway, however, it was a flop. They married and returned to wartime England, where Olivier became Sub-Lieutenant Olivier of the Fleet Air Arm.

After destroying two planes by crashing one into another without leaving the ground, he was assigned to repacking parachutes. He decided correctly that he could do more for his country by making a movie of “Henry V.”

At 50, Olivier had the nerve to play Archie Rice, in “The Entertainer.” Of the character, an outdated fraud, Olivier remarked, “It’s what I really am. . . . “ Perhaps not a fraud, but certainly muddled. While married to Leigh, Olivier had a 10-year-affair with Danny Kaye, a pairing that may take readers some effort to wrap their minds around.

On a tour to Australia, Olivier fell in love with the handsome young Aussie actor Peter Finch. So did Vivien. While Vivien had an affair with Finch back in England, Olivier had brief interludes with actresses Dorothy Tutin, Claire Bloom and Maxine Audley.

(Truly attentive moviegoers will recognize Audley as the aristocratic dark-haired foil for Marilyn Monroe in “The Prince and the Showgirl.”)

He then fell in love with Joan Plowright, the sturdy and talented actress who played his daughter in the stage production of “The Entertainer” and would become his third wife.

Feeling guilty about mistreating Leigh and, Spoto surmises, about his bisexuality, Olivier found it better to be on stage than living his real life. “Thank Christ, for the next three hours I’ll be Coriolanus,” Olivier wrote. “Nothing like me, not one of my problems. . . .”

The stage may be an escape, but it’s not a place for cowards. Spoto has great respect for Olivier’s courage in working up to the end of his life--through awful illness, a stormy 10 years as director of the National Theater, and extreme loneliness.

He was separated from Plowright at the end of his life. “Joan expected me to die at 70,” Olivier told friends when he was 77. Even worse than his painful illness were panic attacks that made him forget his lines.

The temperament that made Olivier escape to the stage was tough on wives, lovers, friends and children, but a gift to people who saw him act. Could it be that the perfection of the life doesn’t matter if you get the art right?

Olivier was not much given to theorizing about the art of acting. He liked what Margot Fonteyn said when she was asked to explain what she had communicated in a ballet. She answered: “I explained it while I was doing it.”

Next: Jonathan Kirsch reviews “To the End of Time” by Richard M. Clurman (Simon & Schuster).

More to Read

5 essential Russell Banks novels you should read

Jan. 8, 2023

Rising-star author Anthony Veasna So died at 28. Now you can read his unfinished novel

Dec. 4, 2023

Salman Rushdie’s upcoming memoir delays trial of man charged in 2022 stabbing

Jan. 3, 2024

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

The week’s bestselling books, March 31

March 27, 2024

Storytellers can inspire climate action without killing hope

March 26, 2024

Entertainment & Arts

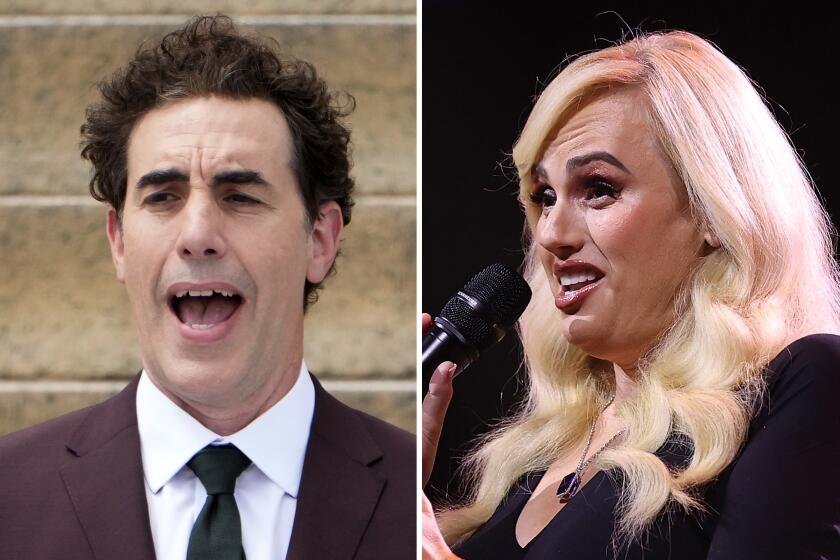

Sacha Baron Cohen counters Rebel Wilson after she claims reps ‘bullied’ her over book

March 25, 2024

The week’s bestselling books, March 24

March 20, 2024

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Joan Plowright at 90: the star who spoke truth to British theatre

On the actor’s birthday, our critic picks three key performances that illuminate her gift for earthy honesty

J oan Plowright, who celebrates her 90th birthday today, is the senior figure in a remarkable generation of actors including Judi Dench, Maggie Smith and Eileen Atkins, all celebrated in the film Nothing Like a Dame . Her marriage to Laurence Olivier inevitably made her part of showbiz aristocracy but Plowright brought to British theatre a quality of earthiness and emotional directness shared by near-contemporaries such as Albert Finney , Peter O’Toole and Billie Whitelaw . As the daughter of a Lincolnshire newspaper editor, she could hardly be called working-class yet she was part of a movement that helped British theatre shed its aura of evasive gentility.

You could, for the sake of convenience, divide Plowright’s working life into three phases: her Royal Court period, her National Theatre years and her post-National freelance career.

Rather than catalogue her performances, I would pick out three that illustrate her capacity to give us the unvarnished truth. She came to prominence in the Royal Court of the 1950s but, although I missed her in The Country Wife and the double bill of Ionesco’s The Chairs and The Lesson, where she played a wizened crone and a preyed-on pupil, I did catch her as Beatie Bryant in Arnold Wesker’s Roots – which quickly became a landmark in postwar drama.

The point about Beatie is that she is the daughter of Norfolk farmworkers who, on returning home, first parrots the opinions of her London boyfriend and then, when he fails to turn up, discovers her own voice. Wesker’s play is part of a long line, harking back to Shaw’s Pygmalion and anticipating Willy Russell’s Educating Rita , about female self-realisation. Everyone who saw it remembers the ecstasy that illumined Plowright’s features as she realised she was at last speaking, and thinking, for herself. But Plowright caught no less well Beatie’s potential for joy in the scene where she danced round the stage as her mother clapped to the rhythmic excitement of Bizet’s suite from L’Arlésienne.

Olivier claimed to be “knocked off my feet by her performance”. By 1961 he and Plowright were married and she became a vital part of his inaugural Chichester Festival theatre seasons, which provided a launchpad for the National Theatre company. It can sometimes be tedious to bang on about old productions but anyone who wishes can still find on DVD Olivier’s Uncle Vanya which played at Chichester in 1962-63 and then at the Old Vic. It was one of the great Chekhov experiences of the 20th century, and Plowright’s performance as Sonya, hopelessly in love with Astrov (played by Olivier), was a model of stoic endurance in the face of unfulfilled passion.

The great moment comes at the play’s end when Sonya is left alone with her uncle to face a future of loveless toil. It would be easy to play Sonya’s final consoling speech sentimentally. Instead Plowright, looking at the desolate features of Michael Redgrave as Vanya, struck a note of almost buoyant optimism as she claimed: “When our time comes, we shall die without a murmur … we shall see a light that is bright and lovely and beautiful … we shall rest.” Plowright caught perfectly Sonya’s note of defiant faith in a way that brought tears to my eyes at the time, and that still does when I watch or listen to that performance.

Plowright went on to do many fine things at the National including a strong-willed Maggie in Hobson’s Choice, leading her chosen groom off to the marriage bed by his ears, a deeply sensual Masha in Three Sisters and a single-minded Portia in The Merchant of Venice who first preaches mercy and then displays a vindictive cruelty to Shylock. She was an integral part of the National company at the Old Vic, but the determination to avoid any sense of favouritism – and the fact that she had three young children to bring up – meant that her potential was not always fulfilled. I would love to have seen her play Cleopatra, Lady Macbeth, or Hedda Gabler.

After the National, however, Plowright achieved much. She did Shakespeare at Chichester, Chekhov in the West End, two fine plays by Eduardo di Filippo and enjoyed a late-blossoming film career often under the direction of Franco Zeffirelli. But, if I had to pick out one performance that revealed her unrivalled capacity for earthy truthfulness and emotional honesty, it would be that as Poncia in Nuria Espert’s production of Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba at the Lyric Hammersmith, and then the West End, in 1986. The character is the servant to the tyrannical heroine (played by Glenda Jackson). Everything about this performance was perfect, from the way Plowright evoked a lifetime of household drudgery, by smoothing the nap of folded linen, to the hint that she shared the same longing for life and gaiety as Bernarda Alba’s imprisoned daughters.

This is a quality that has characterised much of Plowright’s work: the ability to combine down-to-earth practicality and common sense with an irrepressible joie de vivre. From reading Plowright’s fascinating memoirs, And That’s Not All , you realise how much the National in its early years – and Olivier in particular – owed to her quiet wisdom. Looking back over her rich career is to be reminded of how much she has been a force for change in British acting.

- Joan Plowright

- Laurence Olivier

- National Theatre

- Old Vic Theatre

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Laurence Olivier: A Life. Part 1 & 2 (South Bank Show 1982) The Full Documentary. Originally aired on October 17th, 1982, on ITV. Widely regarded as the m...

This video is about Laurence Olivier Biography in English. Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier, OM ( 22 May 1907 - 11 July 1989) was an English actor and di...

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier, OM was an English actor who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, dominated the British sta...

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier, OM (22nd May 1907 - 11th July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richards...

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier, OM (/ ˈ l ɒr ə n s ˈ k ɜːr ə ˈ l ɪ v i eɪ /; 22 May 1907 - 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage of the mid-20th century. He also worked in films throughout his career, playing more than fifty cinema ...

Short Biography about the iconic actor Laurence OlivierAll new basic biographical videos based on icon actors and actresses from old Hollywood.The video cont...

Laurence Olivier was born on May 22, 1907, in Surrey, England. He became one of the most revered actors of his time, known for his talent and versatility in ...

Laurence Olivier (born May 22, 1907, Dorking, Surrey, England—died July 11, 1989, near London, England) was a towering figure of the British stage and screen, acclaimed in his lifetime as the greatest English-speaking actor of the 20th century. He was the first member of his profession to be elevated to a life peerage.

Laurence Olivier. Actor: Sleuth. Laurence Olivier could speak William Shakespeare's lines as naturally as if he were "actually thinking them", said English playwright Charles Bennett, who met Olivier in 1927. Laurence Kerr Olivier was born in Dorking, Surrey, England, to Agnes Louise (Crookenden) and Gerard Kerr Olivier, a High Anglican priest. His surname came from a great-great-grandfather ...

Name: Laurence Olivier. Birth date: May 22, 1907. Birth City: Dorking, South England. Best Known For: Laurence Olivier was one of the most acclaimed actors of the 20th century, known for his roles ...

Laurence Olivier. Actor: Sleuth. Laurence Olivier could speak William Shakespeare's lines as naturally as if he were "actually thinking them", said English playwright Charles Bennett, who met Olivier in 1927. Laurence Kerr Olivier was born in Dorking, Surrey, England, to Agnes Louise (Crookenden) and Gerard Kerr Olivier, a High Anglican priest.

Laurence Olivier (1907-1989) was a distinguished English actor and director, widely considered one of the greatest actors of the 20th century. Renowned for his Shakespearean performances on both stage and screen, Olivier's career spanned theatre, film, and television.

Laurence Olivier (1907-1989) was an English actor who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, dominated the British stage of the mid-20th century. He also worked in films throughout his career, playing more than fifty cinema roles. From 1935 he performed in radio broadcasts and, from 1956, had considerable success in television roles.

Laurence Olivier: A Life: With Laurence Olivier, Melvyn Bragg, Peggy Ashcroft, Jill Esmond. A multi-award winning biography covering the life and career of actor/director Laurence Olivier.

Laurence Olivier: A Biography by Donald Spoto, Harper Collins, New York. 480 pp, $23 cloth. Laurence Olivier ran, walked, hobbled, shuffled, galloped and sauntered through nearly 100 plays and 60 films in his long career—and that's not including all the productions he directed. For his very first professional job, at the age of 18 in a ...

Laurence Olivier biography: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V52CFmmnuf8Laurence Olivier biography

Updated on 04/30/19. Sir Laurence Olivier (May 22, 1907—July 11, 1989) ranks as one of the top British actors of the 20th century. He is particularly well-remembered for appearing in and directing Shakespearean plays both on stage and in film. His 1948 movie Hamlet was the first non-American production to win the Oscar for Best Picture.

Born May 22, 1907, in the town of Dorking southwest of London, Laurence Kerr Olivier was the third child of an Anglican clergyman who encouraged him to try acting. At age 10, he was Brutus in a ...

Facts. Also Known As. Sir Laurence Olivier • Baron Olivier of Brighton • Laurence Olivier, Baron Olivier of Brighton • Laurence Kerr Olivier. Born. May 22, 1907 • Dorking • England. Died. July 11, 1989 (aged 82) • near London • England. Awards And Honors.

Olivier, he asserts, was "drunk with desire" for Leigh's "transcendent beauty" and he describes their first illicit encounters as if with his eye to a peephole: "hands, lips, limbs ...

I was told Olivier couldn't bear playing second fiddle, and he was jealous of me. But there was no denying his greatness. Derek Granger. "When I joined, Corrie was already a big ratings ...

Olivier met Vivien Leigh, who would become his second wife, at the same time that Jill Esmond announced she was expecting a child. Olivier's first son, Tarquin, was born in 1936 when Olivier was 29.

Joan Plowright and Laurence Olivier on their wedding day in 1961. Photograph: NY Daily News via Getty Images. Olivier claimed to be "knocked off my feet by her performance".