- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Systematic Reviews & Evidence Synthesis Methods

- Types of Reviews

- Formulate Question

- Find Existing Reviews & Protocols

- Register a Protocol

- Searching Systematically

- Supplementary Searching

- Managing Results

- Deduplication

- Critical Appraisal

- Glossary of terms

- Librarian Support

- Video tutorials This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Review & Evidence Synthesis Boot Camp

What is a Systematic Review?

A systematic review gathers, assesses, and synthesizes all available empirical research on a specific question using a comprehensive search method with an aim to minimize bias.

Or, put another way :

A systematic review begins with a specific research question. Authors of the review gather and evaluate all experimental studies that address the question . Bringing together the findings of these separate studies allows the review authors to make new conclusions from what has been learned.

*The key characteristics of a systematic review are:

- A clearly stated set of objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies;

- An explicit, reproducible methodology;

- A systematic search that attempts to identify all relevant research;

- A critical appraisal of the included studies;

- A clear and objective synthesis and presentation of the characteristics and findings of the included studies.

*Lasserson T, Thomas J, Higgins JPT. Chapter 1: Starting a review. In Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

What is the difference between an evidence synthesis and a systematic review? A systematic review is a type of evidence synthesis. Any literature review is a type of evidence synthesis. For the various types of evidence syntheses/literature reviews, see the page on this guide Types of Reviews .

Systematic reviews are usually done as a team project , requiring cooperation and a commitment of (lots of) time and effort over an extended period. You will need at least 3 people and, depending on the scope of the project and the size of the database result sets, you should plan for 6-24 months from start to completion

Things to Know Before You Begin . . .

Run exploratory searches on the topic to get a sense of the plausibility of your project.

A systematic review requires a research question that is already well-covered in the primary literature. That is, if there has been little previous work on the topic, there will be little to analyze and conclusions hard to find.

A narrowly-focused research question may add little to the knowledge of the field of study.

Make sure someone else has not already 1) written a recent systematic review on your topic, or 2) is in the midst of a similar systematic review project. Instructions on how to check .

Team members will need to use research databases for searching the literature. If these databases are not available through library subscriptions or freely available, their use may require payment or travel. Look here for database recommendations .

It is extremely important to develop a protocol for your project. Guidance is provided here .

Tools such as a reference manager and a screening tool will save time.

Lynn Bostwick : Nursing, Nutrition, Pharmacy, Public Health

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Liz DeHart : Marine Science

Grant Hardaway : Educational Psychology, Kinesiology & Health Education, Social Work

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

- Last Updated: Apr 9, 2024 8:57 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/systematicreviews

1.2.2 What is a systematic review?

A systematic review attempts to collate all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view to minimizing bias, thus providing more reliable findings from which conclusions can be drawn and decisions made (Antman 1992, Oxman 1993) . The key characteristics of a systematic review are:

a clearly stated set of objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies;

an explicit, reproducible methodology;

a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies that would meet the eligibility criteria;

an assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies, for example through the assessment of risk of bias; and

a systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies.

Many systematic reviews contain meta-analyses. Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies (Glass 1976). By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analyses can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review (see Chapter 9, Section 9.1.3 ). They also facilitate investigations of the consistency of evidence across studies, and the exploration of differences across studies.

Systematic Review

- Library Help

- What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

- Steps of a Systematic Review

- Framing a Research Question

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Searching the Literature

- Managing the Process

- Meta-analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Introduction to Systematic Review

- Introduction

- Types of literature reviews

- Other Libguides

- Systematic review as part of a dissertation

- Tutorials & Guidelines & Examples from non-Medical Disciplines

Depending on your learning style, please explore the resources in various formats on the tabs above.

For additional tutorials, visit the SR Workshop Videos from UNC at Chapel Hill outlining each stage of the systematic review process.

Know the difference! Systematic review vs. literature review

Types of literature reviews along with associated methodologies

JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis . Find definitions and methodological guidance.

- Systematic Reviews - Chapters 1-7

- Mixed Methods Systematic Reviews - Chapter 8

- Diagnostic Test Accuracy Systematic Reviews - Chapter 9

- Umbrella Reviews - Chapter 10

- Scoping Reviews - Chapter 11

- Systematic Reviews of Measurement Properties - Chapter 12

Systematic reviews vs scoping reviews -

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal , 26 (2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Gough, D., Thomas, J., & Oliver, S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews, 1 (28). htt p s://doi.org/ 10.1186/2046-4053-1-28

Munn, Z., Peters, M., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review ? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC medical research methodology, 18 (1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. Also, check out the Libguide from Weill Cornell Medicine for the differences between a systematic review and a scoping review and when to embark on either one of them.

Sutton, A., Clowes, M., Preston, L., & Booth, A. (2019). Meeting the review family: Exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements . Health Information & Libraries Journal , 36 (3), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12276

Temple University. Review Types . - This guide provides useful descriptions of some of the types of reviews listed in the above article.

UMD Health Sciences and Human Services Library. Review Types . - Guide describing Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, and Rapid Reviews.

Whittemore, R., Chao, A., Jang, M., Minges, K. E., & Park, C. (2014). Methods for knowledge synthesis: An overview. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care, 43 (5), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.05.014

Differences between a systematic review and other types of reviews

Armstrong, R., Hall, B. J., Doyle, J., & Waters, E. (2011). ‘ Scoping the scope ’ of a cochrane review. Journal of Public Health , 33 (1), 147–150. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr015

Kowalczyk, N., & Truluck, C. (2013). Literature reviews and systematic reviews: What is the difference? Radiologic Technology , 85 (2), 219–222.

White, H., Albers, B., Gaarder, M., Kornør, H., Littell, J., Marshall, Z., Matthew, C., Pigott, T., Snilstveit, B., Waddington, H., & Welch, V. (2020). Guidance for producing a Campbell evidence and gap map . Campbell Systematic Reviews, 16 (4), e1125. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1125. Check also this comparison between evidence and gaps maps and systematic reviews.

Rapid Reviews Tutorials

Rapid Review Guidebook by the National Collaborating Centre of Methods and Tools (NCCMT)

Hamel, C., Michaud, A., Thuku, M., Skidmore, B., Stevens, A., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., & Garritty, C. (2021). Defining Rapid Reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews. Journal of clinical epidemiology , 129 , 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.09.041

- Müller, C., Lautenschläger, S., Meyer, G., & Stephan, A. (2017). Interventions to support people with dementia and their caregivers during the transition from home care to nursing home care: A systematic review . International Journal of Nursing Studies, 71 , 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.03.013

- Bhui, K. S., Aslam, R. W., Palinski, A., McCabe, R., Johnson, M. R. D., Weich, S., … Szczepura, A. (2015). Interventions to improve therapeutic communications between Black and minority ethnic patients and professionals in psychiatric services: Systematic review . The British Journal of Psychiatry, 207 (2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.158899

- Rosen, L. J., Noach, M. B., Winickoff, J. P., & Hovell, M. F. (2012). Parental smoking cessation to protect young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis . Pediatrics, 129 (1), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3209

Scoping Review

- Hyshka, E., Karekezi, K., Tan, B., Slater, L. G., Jahrig, J., & Wild, T. C. (2017). The role of consumer perspectives in estimating population need for substance use services: A scoping review . BMC Health Services Research, 171-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2153-z

- Olson, K., Hewit, J., Slater, L.G., Chambers, T., Hicks, D., Farmer, A., & ... Kolb, B. (2016). Assessing cognitive function in adults during or following chemotherapy: A scoping review . Supportive Care In Cancer, 24 (7), 3223-3234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3215-1

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency . Research Synthesis Methods, 5 (4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

- Scoping Review Tutorial from UNC at Chapel Hill

Qualitative Systematic Review/Meta-Synthesis

- Lee, H., Tamminen, K. A., Clark, A. M., Slater, L., Spence, J. C., & Holt, N. L. (2015). A meta-study of qualitative research examining determinants of children's independent active free play . International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity, 12 (5), 121-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0165-9

Videos on systematic reviews

Systematic Reviews: What are they? Are they right for my research? - 47 min. video recording with a closed caption option.

More training videos on systematic reviews:

Books on Systematic Reviews

Books on Meta-analysis

- University of Toronto Libraries - very detailed with good tips on the sensitivity and specificity of searches.

- Monash University - includes an interactive case study tutorial.

- Dalhousie University Libraries - a comprehensive How-To Guide on conducting a systematic review.

Guidelines for a systematic review as part of the dissertation

- Guidelines for Systematic Reviews in the Context of Doctoral Education Background by University of Victoria (PDF)

- Can I conduct a Systematic Review as my Master’s dissertation or PhD thesis? Yes, It Depends! by Farhad (blog)

- What is a Systematic Review Dissertation Like? by the University of Edinburgh (50 min video)

Further readings on experiences of PhD students and doctoral programs with systematic reviews

Puljak, L., & Sapunar, D. (2017). Acceptance of a systematic review as a thesis: Survey of biomedical doctoral programs in Europe . Systematic Reviews , 6 (1), 253. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0653-x

Perry, A., & Hammond, N. (2002). Systematic reviews: The experiences of a PhD Student . Psychology Learning & Teaching , 2 (1), 32–35. https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2002.2.1.32

Daigneault, P.-M., Jacob, S., & Ouimet, M. (2014). Using systematic review methods within a Ph.D. dissertation in political science: Challenges and lessons learned from practice . International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 17 (3), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.730704

UMD Doctor of Philosophy Degree Policies

Before you embark on a systematic review research project, check the UMD PhD Policies to make sure you are on the right path. Systematic reviews require a team of at least two reviewers and an information specialist or a librarian. Discuss with your advisor the authorship roles of the involved team members. Keep in mind that the UMD Doctor of Philosophy Degree Policies (scroll down to the section, Inclusion of one's own previously published materials in a dissertation ) outline such cases, specifically the following:

" It is recognized that a graduate student may co-author work with faculty members and colleagues that should be included in a dissertation . In such an event, a letter should be sent to the Dean of the Graduate School certifying that the student's examining committee has determined that the student made a substantial contribution to that work. This letter should also note that the inclusion of the work has the approval of the dissertation advisor and the program chair or Graduate Director. The letter should be included with the dissertation at the time of submission. The format of such inclusions must conform to the standard dissertation format. A foreword to the dissertation, as approved by the Dissertation Committee, must state that the student made substantial contributions to the relevant aspects of the jointly authored work included in the dissertation."

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions - See Part 2: General methods for Cochrane reviews

- Systematic Searches - Yale library video tutorial series

- Using PubMed's Clinical Queries to Find Systematic Reviews - From the U.S. National Library of Medicine

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: A step-by-step guide - From the University of Edinsburgh, Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology

Bioinformatics

- Mariano, D. C., Leite, C., Santos, L. H., Rocha, R. E., & de Melo-Minardi, R. C. (2017). A guide to performing systematic literature reviews in bioinformatics . arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.05813.

Environmental Sciences

Collaboration for Environmental Evidence. 2018. Guidelines and Standards for Evidence synthesis in Environmental Management. Version 5.0 (AS Pullin, GK Frampton, B Livoreil & G Petrokofsky, Eds) www.environmentalevidence.org/information-for-authors .

Pullin, A. S., & Stewart, G. B. (2006). Guidelines for systematic review in conservation and environmental management. Conservation Biology, 20 (6), 1647–1656. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00485.x

Engineering Education

- Borrego, M., Foster, M. J., & Froyd, J. E. (2014). Systematic literature reviews in engineering education and other developing interdisciplinary fields. Journal of Engineering Education, 103 (1), 45–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20038

Public Health

- Hannes, K., & Claes, L. (2007). Learn to read and write systematic reviews: The Belgian Campbell Group . Research on Social Work Practice, 17 (6), 748–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507303106

- McLeroy, K. R., Northridge, M. E., Balcazar, H., Greenberg, M. R., & Landers, S. J. (2012). Reporting guidelines and the American Journal of Public Health’s adoption of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses . American Journal of Public Health, 102 (5), 780–784. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300630

- Pollock, A., & Berge, E. (2018). How to do a systematic review. International Journal of Stroke, 13 (2), 138–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493017743796

- Institute of Medicine. (2011). Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews . https://doi.org/10.17226/13059

- Wanden-Berghe, C., & Sanz-Valero, J. (2012). Systematic reviews in nutrition: Standardized methodology . The British Journal of Nutrition, 107 Suppl 2, S3-7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114512001432

Social Sciences

- Bronson, D., & Davis, T. (2012). Finding and evaluating evidence: Systematic reviews and evidence-based practice (Pocket guides to social work research methods). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

- Cornell University Library Guide - Systematic literature reviews in engineering: Example: Software Engineering

- Biolchini, J., Mian, P. G., Natali, A. C. C., & Travassos, G. H. (2005). Systematic review in software engineering . System Engineering and Computer Science Department COPPE/UFRJ, Technical Report ES, 679 (05), 45.

- Biolchini, J. C., Mian, P. G., Natali, A. C. C., Conte, T. U., & Travassos, G. H. (2007). Scientific research ontology to support systematic review in software engineering . Advanced Engineering Informatics, 21 (2), 133–151.

- Kitchenham, B. (2007). Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering . [Technical Report]. Keele, UK, Keele University, 33(2004), 1-26.

- Weidt, F., & Silva, R. (2016). Systematic literature review in computer science: A practical guide . Relatórios Técnicos do DCC/UFJF , 1 .

- Academic Phrasebank - Get some inspiration and find some terms and phrases for writing your research paper

- Oxford English Dictionary - Use to locate word variants and proper spelling

- << Previous: Library Help

- Next: Steps of a Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 19, 2024 12:47 PM

- URL: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/SR

A Systematic Literature Review of Empirical Research on Epistemic Network Analysis in Education

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley-Blackwell Online Open

An overview of methodological approaches in systematic reviews

Prabhakar veginadu.

1 Department of Rural Clinical Sciences, La Trobe Rural Health School, La Trobe University, Bendigo Victoria, Australia

Hanny Calache

2 Lincoln International Institute for Rural Health, University of Lincoln, Brayford Pool, Lincoln UK

Akshaya Pandian

3 Department of Orthodontics, Saveetha Dental College, Chennai Tamil Nadu, India

Mohd Masood

Associated data.

APPENDIX B: List of excluded studies with detailed reasons for exclusion

APPENDIX C: Quality assessment of included reviews using AMSTAR 2

The aim of this overview is to identify and collate evidence from existing published systematic review (SR) articles evaluating various methodological approaches used at each stage of an SR.

The search was conducted in five electronic databases from inception to November 2020 and updated in February 2022: MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and APA PsycINFO. Title and abstract screening were performed in two stages by one reviewer, supported by a second reviewer. Full‐text screening, data extraction, and quality appraisal were performed by two reviewers independently. The quality of the included SRs was assessed using the AMSTAR 2 checklist.

The search retrieved 41,556 unique citations, of which 9 SRs were deemed eligible for inclusion in final synthesis. Included SRs evaluated 24 unique methodological approaches used for defining the review scope and eligibility, literature search, screening, data extraction, and quality appraisal in the SR process. Limited evidence supports the following (a) searching multiple resources (electronic databases, handsearching, and reference lists) to identify relevant literature; (b) excluding non‐English, gray, and unpublished literature, and (c) use of text‐mining approaches during title and abstract screening.

The overview identified limited SR‐level evidence on various methodological approaches currently employed during five of the seven fundamental steps in the SR process, as well as some methodological modifications currently used in expedited SRs. Overall, findings of this overview highlight the dearth of published SRs focused on SR methodologies and this warrants future work in this area.

1. INTRODUCTION

Evidence synthesis is a prerequisite for knowledge translation. 1 A well conducted systematic review (SR), often in conjunction with meta‐analyses (MA) when appropriate, is considered the “gold standard” of methods for synthesizing evidence related to a topic of interest. 2 The central strength of an SR is the transparency of the methods used to systematically search, appraise, and synthesize the available evidence. 3 Several guidelines, developed by various organizations, are available for the conduct of an SR; 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 among these, Cochrane is considered a pioneer in developing rigorous and highly structured methodology for the conduct of SRs. 8 The guidelines developed by these organizations outline seven fundamental steps required in SR process: defining the scope of the review and eligibility criteria, literature searching and retrieval, selecting eligible studies, extracting relevant data, assessing risk of bias (RoB) in included studies, synthesizing results, and assessing certainty of evidence (CoE) and presenting findings. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7

The methodological rigor involved in an SR can require a significant amount of time and resource, which may not always be available. 9 As a result, there has been a proliferation of modifications made to the traditional SR process, such as refining, shortening, bypassing, or omitting one or more steps, 10 , 11 for example, limits on the number and type of databases searched, limits on publication date, language, and types of studies included, and limiting to one reviewer for screening and selection of studies, as opposed to two or more reviewers. 10 , 11 These methodological modifications are made to accommodate the needs of and resource constraints of the reviewers and stakeholders (e.g., organizations, policymakers, health care professionals, and other knowledge users). While such modifications are considered time and resource efficient, they may introduce bias in the review process reducing their usefulness. 5

Substantial research has been conducted examining various approaches used in the standardized SR methodology and their impact on the validity of SR results. There are a number of published reviews examining the approaches or modifications corresponding to single 12 , 13 or multiple steps 14 involved in an SR. However, there is yet to be a comprehensive summary of the SR‐level evidence for all the seven fundamental steps in an SR. Such a holistic evidence synthesis will provide an empirical basis to confirm the validity of current accepted practices in the conduct of SRs. Furthermore, sometimes there is a balance that needs to be achieved between the resource availability and the need to synthesize the evidence in the best way possible, given the constraints. This evidence base will also inform the choice of modifications to be made to the SR methods, as well as the potential impact of these modifications on the SR results. An overview is considered the choice of approach for summarizing existing evidence on a broad topic, directing the reader to evidence, or highlighting the gaps in evidence, where the evidence is derived exclusively from SRs. 15 Therefore, for this review, an overview approach was used to (a) identify and collate evidence from existing published SR articles evaluating various methodological approaches employed in each of the seven fundamental steps of an SR and (b) highlight both the gaps in the current research and the potential areas for future research on the methods employed in SRs.

An a priori protocol was developed for this overview but was not registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), as the review was primarily methodological in nature and did not meet PROSPERO eligibility criteria for registration. The protocol is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. This overview was conducted based on the guidelines for the conduct of overviews as outlined in The Cochrane Handbook. 15 Reporting followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐analyses (PRISMA) statement. 3

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Only published SRs, with or without associated MA, were included in this overview. We adopted the defining characteristics of SRs from The Cochrane Handbook. 5 According to The Cochrane Handbook, a review was considered systematic if it satisfied the following criteria: (a) clearly states the objectives and eligibility criteria for study inclusion; (b) provides reproducible methodology; (c) includes a systematic search to identify all eligible studies; (d) reports assessment of validity of findings of included studies (e.g., RoB assessment of the included studies); (e) systematically presents all the characteristics or findings of the included studies. 5 Reviews that did not meet all of the above criteria were not considered a SR for this study and were excluded. MA‐only articles were included if it was mentioned that the MA was based on an SR.

SRs and/or MA of primary studies evaluating methodological approaches used in defining review scope and study eligibility, literature search, study selection, data extraction, RoB assessment, data synthesis, and CoE assessment and reporting were included. The methodological approaches examined in these SRs and/or MA can also be related to the substeps or elements of these steps; for example, applying limits on date or type of publication are the elements of literature search. Included SRs examined or compared various aspects of a method or methods, and the associated factors, including but not limited to: precision or effectiveness; accuracy or reliability; impact on the SR and/or MA results; reproducibility of an SR steps or bias occurred; time and/or resource efficiency. SRs assessing the methodological quality of SRs (e.g., adherence to reporting guidelines), evaluating techniques for building search strategies or the use of specific database filters (e.g., use of Boolean operators or search filters for randomized controlled trials), examining various tools used for RoB or CoE assessment (e.g., ROBINS vs. Cochrane RoB tool), or evaluating statistical techniques used in meta‐analyses were excluded. 14

2.2. Search

The search for published SRs was performed on the following scientific databases initially from inception to third week of November 2020 and updated in the last week of February 2022: MEDLINE (via Ovid), Embase (via Ovid), Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and American Psychological Association (APA) PsycINFO. Search was restricted to English language publications. Following the objectives of this study, study design filters within databases were used to restrict the search to SRs and MA, where available. The reference lists of included SRs were also searched for potentially relevant publications.

The search terms included keywords, truncations, and subject headings for the key concepts in the review question: SRs and/or MA, methods, and evaluation. Some of the terms were adopted from the search strategy used in a previous review by Robson et al., which reviewed primary studies on methodological approaches used in study selection, data extraction, and quality appraisal steps of SR process. 14 Individual search strategies were developed for respective databases by combining the search terms using appropriate proximity and Boolean operators, along with the related subject headings in order to identify SRs and/or MA. 16 , 17 A senior librarian was consulted in the design of the search terms and strategy. Appendix A presents the detailed search strategies for all five databases.

2.3. Study selection and data extraction

Title and abstract screening of references were performed in three steps. First, one reviewer (PV) screened all the titles and excluded obviously irrelevant citations, for example, articles on topics not related to SRs, non‐SR publications (such as randomized controlled trials, observational studies, scoping reviews, etc.). Next, from the remaining citations, a random sample of 200 titles and abstracts were screened against the predefined eligibility criteria by two reviewers (PV and MM), independently, in duplicate. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. This step ensured that the responses of the two reviewers were calibrated for consistency in the application of the eligibility criteria in the screening process. Finally, all the remaining titles and abstracts were reviewed by a single “calibrated” reviewer (PV) to identify potential full‐text records. Full‐text screening was performed by at least two authors independently (PV screened all the records, and duplicate assessment was conducted by MM, HC, or MG), with discrepancies resolved via discussions or by consulting a third reviewer.

Data related to review characteristics, results, key findings, and conclusions were extracted by at least two reviewers independently (PV performed data extraction for all the reviews and duplicate extraction was performed by AP, HC, or MG).

2.4. Quality assessment of included reviews

The quality assessment of the included SRs was performed using the AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews). The tool consists of a 16‐item checklist addressing critical and noncritical domains. 18 For the purpose of this study, the domain related to MA was reclassified from critical to noncritical, as SRs with and without MA were included. The other six critical domains were used according to the tool guidelines. 18 Two reviewers (PV and AP) independently responded to each of the 16 items in the checklist with either “yes,” “partial yes,” or “no.” Based on the interpretations of the critical and noncritical domains, the overall quality of the review was rated as high, moderate, low, or critically low. 18 Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer.

2.5. Data synthesis

To provide an understandable summary of existing evidence syntheses, characteristics of the methods evaluated in the included SRs were examined and key findings were categorized and presented based on the corresponding step in the SR process. The categories of key elements within each step were discussed and agreed by the authors. Results of the included reviews were tabulated and summarized descriptively, along with a discussion on any overlap in the primary studies. 15 No quantitative analyses of the data were performed.

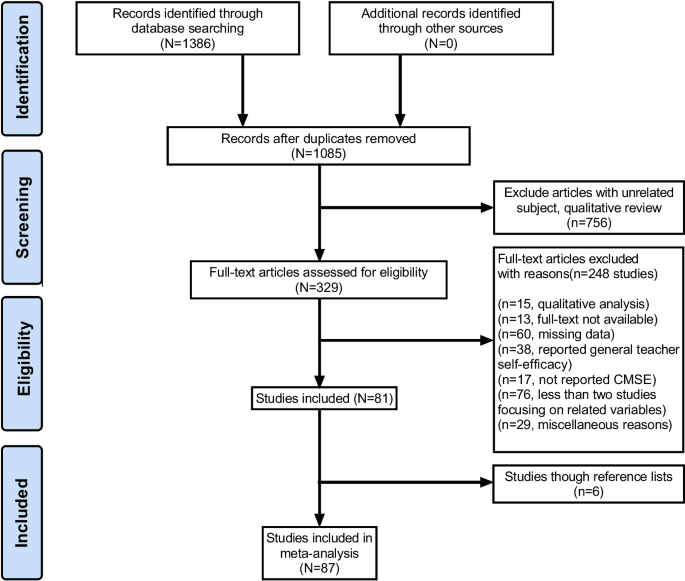

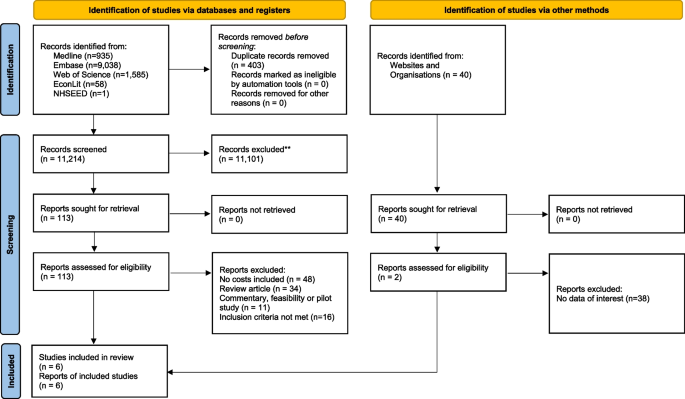

From 41,556 unique citations identified through literature search, 50 full‐text records were reviewed, and nine systematic reviews 14 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 were deemed eligible for inclusion. The flow of studies through the screening process is presented in Figure 1 . A list of excluded studies with reasons can be found in Appendix B .

Study selection flowchart

3.1. Characteristics of included reviews

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of included SRs. The majority of the included reviews (six of nine) were published after 2010. 14 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Four of the nine included SRs were Cochrane reviews. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 The number of databases searched in the reviews ranged from 2 to 14, 2 reviews searched gray literature sources, 24 , 25 and 7 reviews included a supplementary search strategy to identify relevant literature. 14 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 26 Three of the included SRs (all Cochrane reviews) included an integrated MA. 20 , 21 , 23

Characteristics of included studies

SR = systematic review; MA = meta‐analysis; RCT = randomized controlled trial; CCT = controlled clinical trial; N/R = not reported.

The included SRs evaluated 24 unique methodological approaches (26 in total) used across five steps in the SR process; 8 SRs evaluated 6 approaches, 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 while 1 review evaluated 18 approaches. 14 Exclusion of gray or unpublished literature 21 , 26 and blinding of reviewers for RoB assessment 14 , 23 were evaluated in two reviews each. Included SRs evaluated methods used in five different steps in the SR process, including methods used in defining the scope of review ( n = 3), literature search ( n = 3), study selection ( n = 2), data extraction ( n = 1), and RoB assessment ( n = 2) (Table 2 ).

Summary of findings from review evaluating systematic review methods

There was some overlap in the primary studies evaluated in the included SRs on the same topics: Schmucker et al. 26 and Hopewell et al. 21 ( n = 4), Hopewell et al. 20 and Crumley et al. 19 ( n = 30), and Robson et al. 14 and Morissette et al. 23 ( n = 4). There were no conflicting results between any of the identified SRs on the same topic.

3.2. Methodological quality of included reviews

Overall, the quality of the included reviews was assessed as moderate at best (Table 2 ). The most common critical weakness in the reviews was failure to provide justification for excluding individual studies (four reviews). Detailed quality assessment is provided in Appendix C .

3.3. Evidence on systematic review methods

3.3.1. methods for defining review scope and eligibility.

Two SRs investigated the effect of excluding data obtained from gray or unpublished sources on the pooled effect estimates of MA. 21 , 26 Hopewell et al. 21 reviewed five studies that compared the impact of gray literature on the results of a cohort of MA of RCTs in health care interventions. Gray literature was defined as information published in “print or electronic sources not controlled by commercial or academic publishers.” Findings showed an overall greater treatment effect for published trials than trials reported in gray literature. In a more recent review, Schmucker et al. 26 addressed similar objectives, by investigating gray and unpublished data in medicine. In addition to gray literature, defined similar to the previous review by Hopewell et al., the authors also evaluated unpublished data—defined as “supplemental unpublished data related to published trials, data obtained from the Food and Drug Administration or other regulatory websites or postmarketing analyses hidden from the public.” The review found that in majority of the MA, excluding gray literature had little or no effect on the pooled effect estimates. The evidence was limited to conclude if the data from gray and unpublished literature had an impact on the conclusions of MA. 26

Morrison et al. 24 examined five studies measuring the effect of excluding non‐English language RCTs on the summary treatment effects of SR‐based MA in various fields of conventional medicine. Although none of the included studies reported major difference in the treatment effect estimates between English only and non‐English inclusive MA, the review found inconsistent evidence regarding the methodological and reporting quality of English and non‐English trials. 24 As such, there might be a risk of introducing “language bias” when excluding non‐English language RCTs. The authors also noted that the numbers of non‐English trials vary across medical specialties, as does the impact of these trials on MA results. Based on these findings, Morrison et al. 24 conclude that literature searches must include non‐English studies when resources and time are available to minimize the risk of introducing “language bias.”

3.3.2. Methods for searching studies

Crumley et al. 19 analyzed recall (also referred to as “sensitivity” by some researchers; defined as “percentage of relevant studies identified by the search”) and precision (defined as “percentage of studies identified by the search that were relevant”) when searching a single resource to identify randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials, as opposed to searching multiple resources. The studies included in their review frequently compared a MEDLINE only search with the search involving a combination of other resources. The review found low median recall estimates (median values between 24% and 92%) and very low median precisions (median values between 0% and 49%) for most of the electronic databases when searched singularly. 19 A between‐database comparison, based on the type of search strategy used, showed better recall and precision for complex and Cochrane Highly Sensitive search strategies (CHSSS). In conclusion, the authors emphasize that literature searches for trials in SRs must include multiple sources. 19

In an SR comparing handsearching and electronic database searching, Hopewell et al. 20 found that handsearching retrieved more relevant RCTs (retrieval rate of 92%−100%) than searching in a single electronic database (retrieval rates of 67% for PsycINFO/PsycLIT, 55% for MEDLINE, and 49% for Embase). The retrieval rates varied depending on the quality of handsearching, type of electronic search strategy used (e.g., simple, complex or CHSSS), and type of trial reports searched (e.g., full reports, conference abstracts, etc.). The authors concluded that handsearching was particularly important in identifying full trials published in nonindexed journals and in languages other than English, as well as those published as abstracts and letters. 20

The effectiveness of checking reference lists to retrieve additional relevant studies for an SR was investigated by Horsley et al. 22 The review reported that checking reference lists yielded 2.5%–40% more studies depending on the quality and comprehensiveness of the electronic search used. The authors conclude that there is some evidence, although from poor quality studies, to support use of checking reference lists to supplement database searching. 22

3.3.3. Methods for selecting studies

Three approaches relevant to reviewer characteristics, including number, experience, and blinding of reviewers involved in the screening process were highlighted in an SR by Robson et al. 14 Based on the retrieved evidence, the authors recommended that two independent, experienced, and unblinded reviewers be involved in study selection. 14 A modified approach has also been suggested by the review authors, where one reviewer screens and the other reviewer verifies the list of excluded studies, when the resources are limited. It should be noted however this suggestion is likely based on the authors’ opinion, as there was no evidence related to this from the studies included in the review.

Robson et al. 14 also reported two methods describing the use of technology for screening studies: use of Google Translate for translating languages (for example, German language articles to English) to facilitate screening was considered a viable method, while using two computer monitors for screening did not increase the screening efficiency in SR. Title‐first screening was found to be more efficient than simultaneous screening of titles and abstracts, although the gain in time with the former method was lesser than the latter. Therefore, considering that the search results are routinely exported as titles and abstracts, Robson et al. 14 recommend screening titles and abstracts simultaneously. However, the authors note that these conclusions were based on very limited number (in most instances one study per method) of low‐quality studies. 14

3.3.4. Methods for data extraction

Robson et al. 14 examined three approaches for data extraction relevant to reviewer characteristics, including number, experience, and blinding of reviewers (similar to the study selection step). Although based on limited evidence from a small number of studies, the authors recommended use of two experienced and unblinded reviewers for data extraction. The experience of the reviewers was suggested to be especially important when extracting continuous outcomes (or quantitative) data. However, when the resources are limited, data extraction by one reviewer and a verification of the outcomes data by a second reviewer was recommended.

As for the methods involving use of technology, Robson et al. 14 identified limited evidence on the use of two monitors to improve the data extraction efficiency and computer‐assisted programs for graphical data extraction. However, use of Google Translate for data extraction in non‐English articles was not considered to be viable. 14 In the same review, Robson et al. 14 identified evidence supporting contacting authors for obtaining additional relevant data.

3.3.5. Methods for RoB assessment

Two SRs examined the impact of blinding of reviewers for RoB assessments. 14 , 23 Morissette et al. 23 investigated the mean differences between the blinded and unblinded RoB assessment scores and found inconsistent differences among the included studies providing no definitive conclusions. Similar conclusions were drawn in a more recent review by Robson et al., 14 which included four studies on reviewer blinding for RoB assessment that completely overlapped with Morissette et al. 23

Use of experienced reviewers and provision of additional guidance for RoB assessment were examined by Robson et al. 14 The review concluded that providing intensive training and guidance on assessing studies reporting insufficient data to the reviewers improves RoB assessments. 14 Obtaining additional data related to quality assessment by contacting study authors was also found to help the RoB assessments, although based on limited evidence. When assessing the qualitative or mixed method reviews, Robson et al. 14 recommends the use of a structured RoB tool as opposed to an unstructured tool. No SRs were identified on data synthesis and CoE assessment and reporting steps.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. summary of findings.

Nine SRs examining 24 unique methods used across five steps in the SR process were identified in this overview. The collective evidence supports some current traditional and modified SR practices, while challenging other approaches. However, the quality of the included reviews was assessed to be moderate at best and in the majority of the included SRs, evidence related to the evaluated methods was obtained from very limited numbers of primary studies. As such, the interpretations from these SRs should be made cautiously.

The evidence gathered from the included SRs corroborate a few current SR approaches. 5 For example, it is important to search multiple resources for identifying relevant trials (RCTs and/or CCTs). The resources must include a combination of electronic database searching, handsearching, and reference lists of retrieved articles. 5 However, no SRs have been identified that evaluated the impact of the number of electronic databases searched. A recent study by Halladay et al. 27 found that articles on therapeutic intervention, retrieved by searching databases other than PubMed (including Embase), contributed only a small amount of information to the MA and also had a minimal impact on the MA results. The authors concluded that when the resources are limited and when large number of studies are expected to be retrieved for the SR or MA, PubMed‐only search can yield reliable results. 27

Findings from the included SRs also reiterate some methodological modifications currently employed to “expedite” the SR process. 10 , 11 For example, excluding non‐English language trials and gray/unpublished trials from MA have been shown to have minimal or no impact on the results of MA. 24 , 26 However, the efficiency of these SR methods, in terms of time and the resources used, have not been evaluated in the included SRs. 24 , 26 Of the SRs included, only two have focused on the aspect of efficiency 14 , 25 ; O'Mara‐Eves et al. 25 report some evidence to support the use of text‐mining approaches for title and abstract screening in order to increase the rate of screening. Moreover, only one included SR 14 considered primary studies that evaluated reliability (inter‐ or intra‐reviewer consistency) and accuracy (validity when compared against a “gold standard” method) of the SR methods. This can be attributed to the limited number of primary studies that evaluated these outcomes when evaluating the SR methods. 14 Lack of outcome measures related to reliability, accuracy, and efficiency precludes making definitive recommendations on the use of these methods/modifications. Future research studies must focus on these outcomes.

Some evaluated methods may be relevant to multiple steps; for example, exclusions based on publication status (gray/unpublished literature) and language of publication (non‐English language studies) can be outlined in the a priori eligibility criteria or can be incorporated as search limits in the search strategy. SRs included in this overview focused on the effect of study exclusions on pooled treatment effect estimates or MA conclusions. Excluding studies from the search results, after conducting a comprehensive search, based on different eligibility criteria may yield different results when compared to the results obtained when limiting the search itself. 28 Further studies are required to examine this aspect.

Although we acknowledge the lack of standardized quality assessment tools for methodological study designs, we adhered to the Cochrane criteria for identifying SRs in this overview. This was done to ensure consistency in the quality of the included evidence. As a result, we excluded three reviews that did not provide any form of discussion on the quality of the included studies. The methods investigated in these reviews concern supplementary search, 29 data extraction, 12 and screening. 13 However, methods reported in two of these three reviews, by Mathes et al. 12 and Waffenschmidt et al., 13 have also been examined in the SR by Robson et al., 14 which was included in this overview; in most instances (with the exception of one study included in Mathes et al. 12 and Waffenschmidt et al. 13 each), the studies examined in these excluded reviews overlapped with those in the SR by Robson et al. 14

One of the key gaps in the knowledge observed in this overview was the dearth of SRs on the methods used in the data synthesis component of SR. Narrative and quantitative syntheses are the two most commonly used approaches for synthesizing data in evidence synthesis. 5 There are some published studies on the proposed indications and implications of these two approaches. 30 , 31 These studies found that both data synthesis methods produced comparable results and have their own advantages, suggesting that the choice of the method must be based on the purpose of the review. 31 With increasing number of “expedited” SR approaches (so called “rapid reviews”) avoiding MA, 10 , 11 further research studies are warranted in this area to determine the impact of the type of data synthesis on the results of the SR.

4.2. Implications for future research

The findings of this overview highlight several areas of paucity in primary research and evidence synthesis on SR methods. First, no SRs were identified on methods used in two important components of the SR process, including data synthesis and CoE and reporting. As for the included SRs, a limited number of evaluation studies have been identified for several methods. This indicates that further research is required to corroborate many of the methods recommended in current SR guidelines. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Second, some SRs evaluated the impact of methods on the results of quantitative synthesis and MA conclusions. Future research studies must also focus on the interpretations of SR results. 28 , 32 Finally, most of the included SRs were conducted on specific topics related to the field of health care, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other areas. It is important that future research studies evaluating evidence syntheses broaden the objectives and include studies on different topics within the field of health care.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first overview summarizing current evidence from SRs and MA on different methodological approaches used in several fundamental steps in SR conduct. The overview methodology followed well established guidelines and strict criteria defined for the inclusion of SRs.

There are several limitations related to the nature of the included reviews. Evidence for most of the methods investigated in the included reviews was derived from a limited number of primary studies. Also, the majority of the included SRs may be considered outdated as they were published (or last updated) more than 5 years ago 33 ; only three of the nine SRs have been published in the last 5 years. 14 , 25 , 26 Therefore, important and recent evidence related to these topics may not have been included. Substantial numbers of included SRs were conducted in the field of health, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Some method evaluations in the included SRs focused on quantitative analyses components and MA conclusions only. As such, the applicability of these findings to SR more broadly is still unclear. 28 Considering the methodological nature of our overview, limiting the inclusion of SRs according to the Cochrane criteria might have resulted in missing some relevant evidence from those reviews without a quality assessment component. 12 , 13 , 29 Although the included SRs performed some form of quality appraisal of the included studies, most of them did not use a standardized RoB tool, which may impact the confidence in their conclusions. Due to the type of outcome measures used for the method evaluations in the primary studies and the included SRs, some of the identified methods have not been validated against a reference standard.

Some limitations in the overview process must be noted. While our literature search was exhaustive covering five bibliographic databases and supplementary search of reference lists, no gray sources or other evidence resources were searched. Also, the search was primarily conducted in health databases, which might have resulted in missing SRs published in other fields. Moreover, only English language SRs were included for feasibility. As the literature search retrieved large number of citations (i.e., 41,556), the title and abstract screening was performed by a single reviewer, calibrated for consistency in the screening process by another reviewer, owing to time and resource limitations. These might have potentially resulted in some errors when retrieving and selecting relevant SRs. The SR methods were grouped based on key elements of each recommended SR step, as agreed by the authors. This categorization pertains to the identified set of methods and should be considered subjective.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This overview identified limited SR‐level evidence on various methodological approaches currently employed during five of the seven fundamental steps in the SR process. Limited evidence was also identified on some methodological modifications currently used to expedite the SR process. Overall, findings highlight the dearth of SRs on SR methodologies, warranting further work to confirm several current recommendations on conventional and expedited SR processes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

APPENDIX A: Detailed search strategies

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The first author is supported by a La Trobe University Full Fee Research Scholarship and a Graduate Research Scholarship.

Open Access Funding provided by La Trobe University.

Veginadu P, Calache H, Gussy M, Pandian A, Masood M. An overview of methodological approaches in systematic reviews . J Evid Based Med . 2022; 15 :39–54. 10.1111/jebm.12468 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest Content

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 11, Issue 1

- Validity and reliability of outcome measures to assess dysfunctional breathing: a systematic review

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9067-2817 Vikram Mohan 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0049-8430 Chandrasekar Rathinam 2 , 3 ,

- Derick Yates 3 ,

- Aatit Paungmali 4 and

- Christopher Boos 5 , 6

- 1 Department of Rehabilitation and Sports Sciences, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences , Bournemouth University , Bournemouth , UK

- 2 University of Birmingham , Birmingham , UK

- 3 Birmingham Women's and Children's NHS Foundation Trust , Birmingham , UK

- 4 Department of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences , Chiang Mai University , Chiang Mai , Thailand

- 5 Cardiology Department , University Hospitals Dorset NHS Foundation Trust , Poole , UK

- 6 Faculty of Health and Social Sciences , Bournemouth University , Bournemouth , UK

- Correspondence to Chandrasekar Rathinam; c.rathinam{at}bham.ac.uk

Objective This study aimed to systematically review the psychometric properties of outcome measures that assess dysfunctional breathing (DB) in adults.

Methods Studies on developing and evaluating measurement properties to assess DB were included. The study investigated the empirical research published between 1990 and February 2022, with an updated search in May 2023 in the Cochrane Library database of systematic reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Ovid Medline (full), the Ovid Excerta Medica Database, the Ovid allied and complementary medicines database, the Ebscohost Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and the Physiotherapy Evidence Database. The included studies’ methodological quality was assessed using the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) risk of bias checklist. Data analysis and synthesis followed the COSMIN methodology for reviews of outcome measurement instruments.

Results Sixteen studies met the inclusion criteria, and 10 outcome measures were identified. The psychometric properties of these outcome measures were evaluated using COSMIN. The Nijmegen Questionnaire (NQ) is the only outcome measure with ‘sufficient’ ratings for content validity, internal consistency, reliability and construct validity. All other outcome measures did not report characteristics of content validity in the patients’ group.

Discussion The NQ showed high-quality evidence for validity and reliability in assessing DB. Our review suggests that using NQ to evaluate DB in people with bronchial asthma and hyperventilation syndrome is helpful. Further evaluation of the psychometric properties is needed for the remaining outcome measures before considering them for clinical use.

PROSPERO registration number CRD42021274960.

- Patient Outcome Assessment

- Respiratory Measurement

- Physical Examination

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All the relevant data were available at https://osf.io/49hju/ .

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2023-001884

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Clinicians commonly use various outcome measures to examine dysfunctional breathing (DB). Currently, no review is available that examines these outcome measures psychometric properties.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The psychometric properties of the available DB outcome measures in adults are reviewed. Nijmegen Questionnaire (NQ) is the only available outcome measure graded as ‘very high’ quality and evaluated by the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments tool.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The existing outcome measures need to establish content validity and other psychometric properties prior to consideration for clinical use. NQ can be used to assess DB in the adult population.

Introduction

The normal breathing pattern consists of thoracic and abdominal cavity expansion during inhalation and retraction during exhalation. 1 Dysfunctional breathing (DB) deviates from the typical biomechanical pattern. 2 3 Barker and Everard (2015) proposed a definition for DB as ‘an alteration in the normal biomechanical patterns of breathing that results in intermittent or chronic symptoms that may be respiratory and/or non-respiratory’. 3 The DB subtypes include thoracic and extrathoracic patterns. 2 3 Thoracic DB is often observed in hyperventilation and extrathoracic DB in patients with paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction. 3 A DB has historically been identified under a variety of nomenclature; a few examples include thoracoabdominal asynchrony, breathing pattern dysfunction, breathing pattern disorder, unexplained breathlessness, psychological breathlessness, panic breathing, apical breathing, periodic deep sighing, hyperventilation and paradoxical breathing. 3 4 DB has an estimated prevalence of 29% and 8% in people with and without asthma, respectively. 5 This signifies that the general adult population and those with lung disease may experience DB with symptoms that may improve with treatment, contributing to improved quality of life (QoL). 6

Several respiratory disorders, such as bronchial asthma, sleep apnoea and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, are reported to be linked with DB. 7–9 Breathlessness, chest tightness, anxiety, light-headedness and fatigue can occur in people with these illnesses and DB. 6–9 QoL, anxiety, sense of coherence and asthma control are significantly reduced in patients with DB, and breathing retraining has been shown to improve DB and health-related QoL. 10 11 Even though the DB is non-specific in some instances, it can lead directly to misdiagnosing respiratory disease in many situations. 4 Despite the clinical importance of evaluating DB, a consensus on the assessment method still needs to be reached. The potential impacts of DB on constructs like bodily biochemistry, psychological functioning and social aspects must also be considered in a comprehensive evaluation. 6 12–14

Clinical judgement and outcome measures enhance symptom-specific DB evaluation. An outcome measure that examines DB is required to guide suitable treatments. A range of objective evaluation instruments are available, including respiratory movement measuring instruments and respiratory inductive plethysmography. 15 16 These laboratory-based measurement methods offer identification of DB, and they have excellent reliability and validity. 16 17 However, these outcome measures cannot be used in routine clinical practice, especially in the community, due to time consumption, expensive equipment and the need for specific clinical environments. Clinicians often use various outcome measures to assess DB. 18–20 These include Hi-Lo breathing, 21 the Manual Assessment of Respiratory Motion (MARM), 21 the Self-Evaluation of Breathing Questionnaire (SEBQ), 22 the Breathing Pattern Assessment Tool (BPAT), 23 the Total Faulty Breathing Scale (TFBS) 24 and Nijmegen Questionnaire (NQ). 25

The available outcome measures use various methods to detect DB. For example, in MARM, the examiners use the palpation method to detect DB 21 ; Hi-Lo and TFBS assess breathing motion through observation 26 and NQ through self-reported measures. 15 21 25 Before any outcome measure is viable for routine clinical practice, validity and reliability must be established to ensure clinicians’ confidence in the measurement. To determine best practices for the assessment of DB, a systematic review of the existing literature to explore the reliability and validity of outcome measures is imperative. The systematic retrieval and appraisal of all literature about DB with a quantitative synthesis will lead to best practice guidelines for clinicians and researchers. This systematic review aims to provide a synthesis of outcome measures used to evaluate DB and appraise the psychometric properties of these outcome measures.

This study used the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) guidelines for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. 27–29 The methods of this systematic review follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations for systematic reviews and outcome measurement instrument selection, which are currently being piloted. 30 We registered this review protocol on PROSPERO (CRD42021274960) and updated the amendments regularly.

Search strategy

An experienced medical librarian (DY) carried out literature searches in the Cochrane Library database of systematic reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Ovid Medline (full), the Ovid Excerta Medica Database (Embase), the Ovid Allied and complementary medicines database, the Ebscohost Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro).

To perform the literature searches, a construct (DB), instrument (assessment instruments) and outcome (validity and reliability) framework were employed. Following a scoping search, relevant synonyms were found and validated as suitable and informative by the review team’s clinicians and academics. Searches were carried out to identify the relevant subject headings for those databases with a subject thesaurus (MeSH or Emtree) and text words in each database’s title and abstract fields. Proximity operators were used to combine search words together in the title and abstract fields to increase search sensitivity. To increase the precision of the results returned by the searches, the review team decided to include a NOT operator in the search strategies to screen out papers related to sleep apnoea at the database search stage.

Searches were run in February 2022 and repeated in May 2023 before study completion to ensure the review considered the most recently published research. Due to the limited search functionality of the PEDro, this was searched using separate individual search phrases to identify relevant research on DB. On 22 February 2022, five of those phrases were identified as abstracts, and these were ‘dysfunctional breathing’, ‘breathing disorder’, ‘thoracoabdominal synchrony’, ‘apical breathing’ and ‘respiratory dysfunction’. These phrases were searched again on 11 May 2023. Date limits were applied to screen out papers published before 1990. The rationale for this decision was that the term DB or breathing pattern dysfunction, only came into existence and began to be used commonly in the medical literature in 1990. A copy of the full search strategy run in Ovid Medline and other databases is available ( online supplemental file S1 ). The resulting references identified by the database searches were uploaded into the Endnote reference management software package to allow for an initial screening.

Supplemental material

Study selection.

The following inclusion criteria were considered: (1) an outcome measure that investigated the validity and/or reliability of DB in the adult population (18+ years) using clinician-reported and patient-reported outcome measures and (2) full articles and service evaluation reports published in a peer-reviewed journal in English. Exclusion criteria were studies that used laboratory-based outcome measures, systematic reviews, conference abstracts, research letters, commentaries and letters to the editor.

Data extraction (selection and coding)

Two independent reviewers (VM and CR) screened the titles and abstracts for relevancy using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Reference lists of all included studies were also searched for relevant titles. The authors (VM and CR) retrieved full-text articles that met the study criteria. The first author (VM) article (TFBS) was included in this review; to mitigate conflict of interest and reduce bias, only CR investigated the articles related to TFBS. The PRISMA flow diagram of this procedure is depicted in figure 1 using the PRISMA 2020 statement. 31

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart. AMED, Ovid allied and complementary medicines database; CINAHL, Ebscohost Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; EMBASE, Ovid Excerta Medica Database; MEDLINE, Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online; PEDro, Physiotherapy Evidence Database.

Risk of bias and quality of results

The team used the COSMIN methodology for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) and clinician-reported outcome measures to evaluate the psychometric characteristics of outcome measures used in persons with DB. 27–29 The COSMIN PROM recommends using an outcome measure with ’sufficient' content validity and internal consistency. 27–29 The reviewers (VM and CR) individually extracted and evaluated the data for the first nine attributes listed in the COSMIN tool.

The COSMIN checklist was used to assess the methodological rigour of each outcome measure across the measurement attributes. These include reliability, validity and other psychometric properties. The methodologies provided for evaluating the measurement properties of all the outcome measures are included in this systematic review. Study quality was assessed separately for each measurement property using a four-point rating system (very good, adequate, doubtful, inadequate or not applicable). 29 The 'worst score counts' principle was used, where the overall rating for each measurement property is given by the lowest rating of any standard in the box. 28 29 The results of individual studies on measurement characteristics were compared with COSMIN criteria for good measurement qualities. Each outcome was graded as sufficient (+), insufficient (−) or indeterminate (?). Relevance, comprehensiveness and comprehensibility criteria were used to grade the quality of the results in research reporting on content validity.

The result of each study on a measurement property is rated using the most recent standards for good measurement properties. The total ratings of the study outcomes for each measurement property per outcome measure were summarised as sufficient (+), insufficient (−), indeterminate (?) or inconsistent (±). An overall rating was calculated by summing the scoring of each study; if 75% of the studies had the same scoring, that scoring became the overall rating (+ or −). However, if <75% of the studies had the same scoring, the overall rating would become inconsistent (±). If more than two articles were available, a summary of the overall evidence for measuring the properties of the outcome measures was determined. The lowest and highest results for each measurement property of an outcome measure are displayed to illustrate a set of findings that have been qualitatively aggregated.

The evidence’s quality was rated using a modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system, with grades of ‘high’, ‘moderate’, ‘low’ or ‘very low’. 27 The quality of the evidence was not rated for studies with an uncertain overall rating. For the quality assessment, two reviewers (VM and CR) independently worked on each stage while taking into account factors including the risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision and indirectness. Starting with high-quality evidence, the quality of the evidence was reduced while considering all factors for the outcome measures. Disagreements were addressed by discussion and/or consultation with a third reviewer (AP).

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in this review due to the complexity of evaluating the psychometric properties of the DB tools.

Our first search (22 February 2022) yielded 1735 references. After removing duplicates, 1246 references were included for title and abstract screening. In our second search (11 May 2023), we identified 144 references. After removing duplicates, 96 references were included for title and abstract screening. Sixteen papers met inclusion criteria, seven through database searching and nine through searching reference lists of included studies ( figure 1 ).

Overview of outcome measures

Our search identified the following ten outcome measures that have examined reliability and/or validity components: Breathing Vigilance Questionnaires (Breathe-VQ), 32 MARM, 15 21 NQ, 33–37 BPAT, 38 39 Hi Lo test, 21 clinical assessments of increased work of breathing, 40 Milstein Breathing Pattern Assessment Index (M-BPAI), 41 SEBQ, 14 22 TFBS 24 26 and Dyspnoea-12 (D12) questionnaire. 38 The Hi-Lo and D-12 scales were not included in this review for evaluation because they are not the primary scales used to assess DB. 21 38 Of the 16 studies, only nine included participants with DB, and the remaining seven included healthy participants. The COSMIN guidelines recommend testing the measurement properties on the target population. 27 However, the identified studies have used these outcome measures in patients and healthy people. Therefore, these groups’ measurement properties were given separately ( table 1 ( online supplemental file S2 ).

- View inline

Characteristics of outcome measures in studies involving patients

Developmental and content validity studies

Developmental studies.

The evidence synthesis of the developmental and content validity of available outcome measures is summarised in table 2 . Of the eight outcome measures, only two were reported to have developmental and content validity properties. 32 33 35 36 A representative patient sample and a cognitive interview are required to develop an outcome measure. A cognitive interview study offers information on the items’ depth, especially their readability as an outcome measure. However, this was only followed in some of the included studies. All four studies involved experts 32 34–36 and three involved patients. 34–36 Concept elucidation was deemed ‘inadequate’ for Breathe-VQ and Korean-NQ because only healthy participants engaged in the studies. 32 33 Other NQ trials were rated ‘very good’ since the patients involved were typical of the target population.

Evidence synthesis of developmental, content validity of Nijmegen Questionnaire and Breathing Vigilance Questionnaire using COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments checklist

Content validity studies

Three of the four articles on the content validity of NQ involved patients 34–36 and all four involved experts. 33–36 Of these three studies, patients’ relevance, comprehensiveness and comprehensibility were evaluated for one study only. 34 A cognitive interview was conducted for the Breathe-VQ, but the quality was ‘inadequate’ as it was not conducted in a patient population. 32 No studies on the development and content validity of TFBS, MARM or SEBQ were found. Only the NQ has been considered for rating, and it was judged as ‘sufficient’.

Risk of bias assessment rating of other measurement properties

The evidence synthesis for all outcome measures and additional measurement properties is summarised in table 3 ( online supplemental file S3 ) and Supplementary file S4— https://osf.io/49hju/ .

Methodological quality and rating of psychometric properties in studies involving patients

Internal structure

Among the included studies, only three reported structural validity. 32 34 37 Two studies explored the structural validity of the NQ measure, 34 37 and one study explored the Breathe-VQ measure. 26 NQ structural validity was examined using the Rasch model and exploratory factor analysis with ‘very good’ and ‘inadequate’ quality. 34 37 For structural validity, the Breathe-VQ study employed exploratory/confirmatory factor analysis of ‘very good’ quality. 32 The internal consistency of the NQ, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, ranged from >0.70 to 0.92 with a ‘very good’ quality and ‘sufficient’ rating. 34 35 However, Rasch and factor analysis do not apply to other outcome measures, especially clinician-reported outcome measures.

Reliability

In total, 10 studies reported reliability measures. M-BPAI 41 and TFBS 24 26 were rated to have ‘very good’ methodological quality and ‘sufficient’ rating. 41 The methodological quality and rating were the same as the MARM and SEBQ. 15 21 22 Only one study that reported the reliability of clinical assessment of the work of breathing exhibited ‘adequate’ methodological quality and was ‘indeterminate’ for the rating. 40 The test-retest reliability values for NQ were in the range of 0.90 and 0.98, corresponding to ‘very good’ to ‘adequate’ quality. 34–36 It was also judged that the NQ’s overall rating was ‘sufficient’. The correlation value ranges from 0.81 to 0.82 when analysing NQ’s hypothesis testing for construct validity, indicating ‘very good’ quality and ‘sufficient’ rating. 34 35 A more comprehensive evidence synthesis for these and other outcome measures is available in Supplementary file S4— https://osf.io/49hju/ .

GRADE quality

The reviewers used GRADE to assess the quality of studies that involved participants with respiratory disease since the clinical application would be acceptable in the actual patient population. As a result, only the NQ that included individuals with asthma and hyperventilation syndrome was included in the GRADE quality assessment. The evidence quality is ‘high’ for the NQ in reliability and hypothesis testing for construct validity domains but ‘low’ for cross-cultural and structural validity domains. The GRADE quality assessment cannot be applied to the remaining outcome measures.

This systematic review presented an overview of outcome measures used to assess DB and evaluated the psychometric properties of outcome measures used in healthy and DB populations. NQ is the only outcome measure with sufficient psychometric properties to be considered by clinicians for the DB assessment.

Nijmegen Questionnaire

NQ’s measurement properties have gained much attention due to its long record and frequent use in DB assessment, notably in conditions including bronchial asthma and hyperventilation syndrome. 39 42 The available evidence indicated that the NQ had been evaluated using rigorous methods, and its content validity, internal consistency and reliability were commonly reported. This outcome measure has been translated into other languages, but for one of the translated versions, the PROM development and content validity were not well documented. 34 However, other measurement properties were well established. 34