There’s No Such Thing as Free Will

But we’re better off believing in it anyway.

F or centuries , philosophers and theologians have almost unanimously held that civilization as we know it depends on a widespread belief in free will—and that losing this belief could be calamitous. Our codes of ethics, for example, assume that we can freely choose between right and wrong. In the Christian tradition, this is known as “moral liberty”—the capacity to discern and pursue the good, instead of merely being compelled by appetites and desires. The great Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant reaffirmed this link between freedom and goodness. If we are not free to choose, he argued, then it would make no sense to say we ought to choose the path of righteousness.

Today, the assumption of free will runs through every aspect of American politics, from welfare provision to criminal law. It permeates the popular culture and underpins the American dream—the belief that anyone can make something of themselves no matter what their start in life. As Barack Obama wrote in The Audacity of Hope , American “values are rooted in a basic optimism about life and a faith in free will.”

So what happens if this faith erodes?

The sciences have grown steadily bolder in their claim that all human behavior can be explained through the clockwork laws of cause and effect. This shift in perception is the continuation of an intellectual revolution that began about 150 years ago, when Charles Darwin first published On the Origin of Species . Shortly after Darwin put forth his theory of evolution, his cousin Sir Francis Galton began to draw out the implications: If we have evolved, then mental faculties like intelligence must be hereditary. But we use those faculties—which some people have to a greater degree than others—to make decisions. So our ability to choose our fate is not free, but depends on our biological inheritance.

Explore the June 2016 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Galton launched a debate that raged throughout the 20th century over nature versus nurture. Are our actions the unfolding effect of our genetics? Or the outcome of what has been imprinted on us by the environment? Impressive evidence accumulated for the importance of each factor. Whether scientists supported one, the other, or a mix of both, they increasingly assumed that our deeds must be determined by something .

In recent decades, research on the inner workings of the brain has helped to resolve the nature-nurture debate—and has dealt a further blow to the idea of free will. Brain scanners have enabled us to peer inside a living person’s skull, revealing intricate networks of neurons and allowing scientists to reach broad agreement that these networks are shaped by both genes and environment. But there is also agreement in the scientific community that the firing of neurons determines not just some or most but all of our thoughts, hopes, memories, and dreams.

We know that changes to brain chemistry can alter behavior—otherwise neither alcohol nor antipsychotics would have their desired effects. The same holds true for brain structure: Cases of ordinary adults becoming murderers or pedophiles after developing a brain tumor demonstrate how dependent we are on the physical properties of our gray stuff.

Many scientists say that the American physiologist Benjamin Libet demonstrated in the 1980s that we have no free will. It was already known that electrical activity builds up in a person’s brain before she, for example, moves her hand; Libet showed that this buildup occurs before the person consciously makes a decision to move. The conscious experience of deciding to act, which we usually associate with free will, appears to be an add-on, a post hoc reconstruction of events that occurs after the brain has already set the act in motion.

The 20th-century nature-nurture debate prepared us to think of ourselves as shaped by influences beyond our control. But it left some room, at least in the popular imagination, for the possibility that we could overcome our circumstances or our genes to become the author of our own destiny. The challenge posed by neuroscience is more radical: It describes the brain as a physical system like any other, and suggests that we no more will it to operate in a particular way than we will our heart to beat. The contemporary scientific image of human behavior is one of neurons firing, causing other neurons to fire, causing our thoughts and deeds, in an unbroken chain that stretches back to our birth and beyond. In principle, we are therefore completely predictable. If we could understand any individual’s brain architecture and chemistry well enough, we could, in theory, predict that individual’s response to any given stimulus with 100 percent accuracy.

This research and its implications are not new. What is new, though, is the spread of free-will skepticism beyond the laboratories and into the mainstream. The number of court cases, for example, that use evidence from neuroscience has more than doubled in the past decade—mostly in the context of defendants arguing that their brain made them do it. And many people are absorbing this message in other contexts, too, at least judging by the number of books and articles purporting to explain “your brain on” everything from music to magic. Determinism, to one degree or another, is gaining popular currency. The skeptics are in ascendance.

This development raises uncomfortable—and increasingly nontheoretical—questions: If moral responsibility depends on faith in our own agency, then as belief in determinism spreads, will we become morally irresponsible? And if we increasingly see belief in free will as a delusion, what will happen to all those institutions that are based on it?

In 2002, two psychologists had a simple but brilliant idea: Instead of speculating about what might happen if people lost belief in their capacity to choose, they could run an experiment to find out. Kathleen Vohs, then at the University of Utah, and Jonathan Schooler, of the University of Pittsburgh, asked one group of participants to read a passage arguing that free will was an illusion, and another group to read a passage that was neutral on the topic. Then they subjected the members of each group to a variety of temptations and observed their behavior. Would differences in abstract philosophical beliefs influence people’s decisions?

Yes, indeed. When asked to take a math test, with cheating made easy, the group primed to see free will as illusory proved more likely to take an illicit peek at the answers. When given an opportunity to steal—to take more money than they were due from an envelope of $1 coins—those whose belief in free will had been undermined pilfered more. On a range of measures, Vohs told me, she and Schooler found that “people who are induced to believe less in free will are more likely to behave immorally.”

It seems that when people stop believing they are free agents, they stop seeing themselves as blameworthy for their actions. Consequently, they act less responsibly and give in to their baser instincts. Vohs emphasized that this result is not limited to the contrived conditions of a lab experiment. “You see the same effects with people who naturally believe more or less in free will,” she said.

In another study, for instance, Vohs and colleagues measured the extent to which a group of day laborers believed in free will, then examined their performance on the job by looking at their supervisor’s ratings. Those who believed more strongly that they were in control of their own actions showed up on time for work more frequently and were rated by supervisors as more capable. In fact, belief in free will turned out to be a better predictor of job performance than established measures such as self-professed work ethic.

Another pioneer of research into the psychology of free will, Roy Baumeister of Florida State University, has extended these findings. For example, he and colleagues found that students with a weaker belief in free will were less likely to volunteer their time to help a classmate than were those whose belief in free will was stronger. Likewise, those primed to hold a deterministic view by reading statements like “Science has demonstrated that free will is an illusion” were less likely to give money to a homeless person or lend someone a cellphone.

Further studies by Baumeister and colleagues have linked a diminished belief in free will to stress, unhappiness, and a lesser commitment to relationships. They found that when subjects were induced to believe that “all human actions follow from prior events and ultimately can be understood in terms of the movement of molecules,” those subjects came away with a lower sense of life’s meaningfulness. Early this year, other researchers published a study showing that a weaker belief in free will correlates with poor academic performance.

The list goes on: Believing that free will is an illusion has been shown to make people less creative, more likely to conform, less willing to learn from their mistakes, and less grateful toward one another. In every regard, it seems, when we embrace determinism, we indulge our dark side.

Few scholars are comfortable suggesting that people ought to believe an outright lie. Advocating the perpetuation of untruths would breach their integrity and violate a principle that philosophers have long held dear: the Platonic hope that the true and the good go hand in hand. Saul Smilansky, a philosophy professor at the University of Haifa, in Israel, has wrestled with this dilemma throughout his career and come to a painful conclusion: “We cannot afford for people to internalize the truth” about free will.

Smilansky is convinced that free will does not exist in the traditional sense—and that it would be very bad if most people realized this. “Imagine,” he told me, “that I’m deliberating whether to do my duty, such as to parachute into enemy territory, or something more mundane like to risk my job by reporting on some wrongdoing. If everyone accepts that there is no free will, then I’ll know that people will say, ‘Whatever he did, he had no choice—we can’t blame him.’ So I know I’m not going to be condemned for taking the selfish option.” This, he believes, is very dangerous for society, and “the more people accept the determinist picture, the worse things will get.”

Determinism not only undermines blame, Smilansky argues; it also undermines praise. Imagine I do risk my life by jumping into enemy territory to perform a daring mission. Afterward, people will say that I had no choice, that my feats were merely, in Smilansky’s phrase, “an unfolding of the given,” and therefore hardly praiseworthy. And just as undermining blame would remove an obstacle to acting wickedly, so undermining praise would remove an incentive to do good. Our heroes would seem less inspiring, he argues, our achievements less noteworthy, and soon we would sink into decadence and despondency.

Smilansky advocates a view he calls illusionism—the belief that free will is indeed an illusion, but one that society must defend. The idea of determinism, and the facts supporting it, must be kept confined within the ivory tower. Only the initiated, behind those walls, should dare to, as he put it to me, “look the dark truth in the face.” Smilansky says he realizes that there is something drastic, even terrible, about this idea—but if the choice is between the true and the good, then for the sake of society, the true must go.

Smilansky’s arguments may sound odd at first, given his contention that the world is devoid of free will: If we are not really deciding anything, who cares what information is let loose? But new information, of course, is a sensory input like any other; it can change our behavior, even if we are not the conscious agents of that change. In the language of cause and effect, a belief in free will may not inspire us to make the best of ourselves, but it does stimulate us to do so.

Illusionism is a minority position among academic philosophers, most of whom still hope that the good and the true can be reconciled. But it represents an ancient strand of thought among intellectual elites. Nietzsche called free will “a theologians’ artifice” that permits us to “judge and punish.” And many thinkers have believed, as Smilansky does, that institutions of judgment and punishment are necessary if we are to avoid a fall into barbarism.

Smilansky is not advocating policies of Orwellian thought control . Luckily, he argues, we don’t need them. Belief in free will comes naturally to us. Scientists and commentators merely need to exercise some self-restraint, instead of gleefully disabusing people of the illusions that undergird all they hold dear. Most scientists “don’t realize what effect these ideas can have,” Smilansky told me. “Promoting determinism is complacent and dangerous.”

Yet not all scholars who argue publicly against free will are blind to the social and psychological consequences. Some simply don’t agree that these consequences might include the collapse of civilization. One of the most prominent is the neuroscientist and writer Sam Harris, who, in his 2012 book, Free Will , set out to bring down the fantasy of conscious choice. Like Smilansky, he believes that there is no such thing as free will. But Harris thinks we are better off without the whole notion of it.

“We need our beliefs to track what is true,” Harris told me. Illusions, no matter how well intentioned, will always hold us back. For example, we currently use the threat of imprisonment as a crude tool to persuade people not to do bad things. But if we instead accept that “human behavior arises from neurophysiology,” he argued, then we can better understand what is really causing people to do bad things despite this threat of punishment—and how to stop them. “We need,” Harris told me, “to know what are the levers we can pull as a society to encourage people to be the best version of themselves they can be.”

According to Harris, we should acknowledge that even the worst criminals—murderous psychopaths, for example—are in a sense unlucky. “They didn’t pick their genes. They didn’t pick their parents. They didn’t make their brains, yet their brains are the source of their intentions and actions.” In a deep sense, their crimes are not their fault. Recognizing this, we can dispassionately consider how to manage offenders in order to rehabilitate them, protect society, and reduce future offending. Harris thinks that, in time, “it might be possible to cure something like psychopathy,” but only if we accept that the brain, and not some airy-fairy free will, is the source of the deviancy.

Accepting this would also free us from hatred. Holding people responsible for their actions might sound like a keystone of civilized life, but we pay a high price for it: Blaming people makes us angry and vengeful, and that clouds our judgment.

“Compare the response to Hurricane Katrina,” Harris suggested, with “the response to the 9/11 act of terrorism.” For many Americans, the men who hijacked those planes are the embodiment of criminals who freely choose to do evil. But if we give up our notion of free will, then their behavior must be viewed like any other natural phenomenon—and this, Harris believes, would make us much more rational in our response.

Although the scale of the two catastrophes was similar, the reactions were wildly different. Nobody was striving to exact revenge on tropical storms or declare a War on Weather, so responses to Katrina could simply focus on rebuilding and preventing future disasters. The response to 9/11 , Harris argues, was clouded by outrage and the desire for vengeance, and has led to the unnecessary loss of countless more lives. Harris is not saying that we shouldn’t have reacted at all to 9/11, only that a coolheaded response would have looked very different and likely been much less wasteful. “Hatred is toxic,” he told me, “and can destabilize individual lives and whole societies. Losing belief in free will undercuts the rationale for ever hating anyone.”

Whereas the evidence from Kathleen Vohs and her colleagues suggests that social problems may arise from seeing our own actions as determined by forces beyond our control—weakening our morals, our motivation, and our sense of the meaningfulness of life—Harris thinks that social benefits will result from seeing other people’s behavior in the very same light. From that vantage point, the moral implications of determinism look very different, and quite a lot better.

What’s more, Harris argues, as ordinary people come to better understand how their brains work, many of the problems documented by Vohs and others will dissipate. Determinism, he writes in his book, does not mean “that conscious awareness and deliberative thinking serve no purpose.” Certain kinds of action require us to become conscious of a choice—to weigh arguments and appraise evidence. True, if we were put in exactly the same situation again, then 100 times out of 100 we would make the same decision, “just like rewinding a movie and playing it again.” But the act of deliberation—the wrestling with facts and emotions that we feel is essential to our nature—is nonetheless real.

The big problem, in Harris’s view, is that people often confuse determinism with fatalism. Determinism is the belief that our decisions are part of an unbreakable chain of cause and effect. Fatalism, on the other hand, is the belief that our decisions don’t really matter, because whatever is destined to happen will happen—like Oedipus’s marriage to his mother, despite his efforts to avoid that fate.

When people hear there is no free will, they wrongly become fatalistic; they think their efforts will make no difference. But this is a mistake. People are not moving toward an inevitable destiny; given a different stimulus (like a different idea about free will), they will behave differently and so have different lives. If people better understood these fine distinctions, Harris believes, the consequences of losing faith in free will would be much less negative than Vohs’s and Baumeister’s experiments suggest.

Can one go further still? Is there a way forward that preserves both the inspiring power of belief in free will and the compassionate understanding that comes with determinism?

Philosophers and theologians are used to talking about free will as if it is either on or off; as if our consciousness floats, like a ghost, entirely above the causal chain, or as if we roll through life like a rock down a hill. But there might be another way of looking at human agency.

Some scholars argue that we should think about freedom of choice in terms of our very real and sophisticated abilities to map out multiple potential responses to a particular situation. One of these is Bruce Waller, a philosophy professor at Youngstown State University. In his new book, Restorative Free Will , he writes that we should focus on our ability, in any given setting, to generate a wide range of options for ourselves, and to decide among them without external constraint.

For Waller, it simply doesn’t matter that these processes are underpinned by a causal chain of firing neurons. In his view, free will and determinism are not the opposites they are often taken to be; they simply describe our behavior at different levels.

Waller believes his account fits with a scientific understanding of how we evolved: Foraging animals—humans, but also mice, or bears, or crows—need to be able to generate options for themselves and make decisions in a complex and changing environment. Humans, with our massive brains, are much better at thinking up and weighing options than other animals are. Our range of options is much wider, and we are, in a meaningful way, freer as a result.

Waller’s definition of free will is in keeping with how a lot of ordinary people see it. One 2010 study found that people mostly thought of free will in terms of following their desires, free of coercion (such as someone holding a gun to your head). As long as we continue to believe in this kind of practical free will, that should be enough to preserve the sorts of ideals and ethical standards examined by Vohs and Baumeister.

Yet Waller’s account of free will still leads to a very different view of justice and responsibility than most people hold today. No one has caused himself: No one chose his genes or the environment into which he was born. Therefore no one bears ultimate responsibility for who he is and what he does. Waller told me he supported the sentiment of Barack Obama’s 2012 “You didn’t build that” speech, in which the president called attention to the external factors that help bring about success. He was also not surprised that it drew such a sharp reaction from those who want to believe that they were the sole architects of their achievements. But he argues that we must accept that life outcomes are determined by disparities in nature and nurture, “so we can take practical measures to remedy misfortune and help everyone to fulfill their potential.”

Understanding how will be the work of decades, as we slowly unravel the nature of our own minds. In many areas, that work will likely yield more compassion: offering more (and more precise) help to those who find themselves in a bad place. And when the threat of punishment is necessary as a deterrent, it will in many cases be balanced with efforts to strengthen, rather than undermine, the capacities for autonomy that are essential for anyone to lead a decent life. The kind of will that leads to success—seeing positive options for oneself, making good decisions and sticking to them—can be cultivated, and those at the bottom of society are most in need of that cultivation.

To some people, this may sound like a gratuitous attempt to have one’s cake and eat it too. And in a way it is. It is an attempt to retain the best parts of the free-will belief system while ditching the worst. President Obama—who has both defended “a faith in free will” and argued that we are not the sole architects of our fortune—has had to learn what a fine line this is to tread. Yet it might be what we need to rescue the American dream—and indeed, many of our ideas about civilization, the world over—in the scientific age.

About the Author

More Stories

Free Will Exists and Is Measurable

Chapter 5: The problem of free will and determinism

The problem of free will and determinism

Matthew Van Cleave

“You say: I am not free. But I have raised and lowered my arm. Everyone understands that this illogical answer is an irrefutable proof of freedom.”

-Leo Tolstoy

“Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills.”

-Arthur Shopenhauer

“None are more hopelessly enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.”

-Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

The term “freedom” is used in many contexts, from legal, to moral, to psychological, to social, to political, to theological. The founders of the United States often extolled the virtues of “liberty” and “freedom,” as well as cautioned us about how difficult they were to maintain. But what do these terms mean, exactly? What does it mean to claim that humans are (or are not) free? Almost anyone living in a liberal democracy today would affirm that freedom is a good thing, but they almost certainly do not all agree on what freedom is. With a concept as slippery as that of free will, it is not surprising that there is often disagreement. Thus, it will be important to be very clear on what precisely we are talking about when we are either affirming or denying that humans have free will. There is an important general point here that extends beyond the issue of free will: when debating whether or not x exists, we must first be clear on defining x, otherwise we will end up simply talking past each other . The philosophical problem of free will and determinism is the problem of whether or not free will exists in light of determinism. Thus, it is crucial to be clear in defining what we mean by “free will” and “determinism.” As we will see, these turn out to be difficult and contested philosophical questions. In this chapter we will consider these different positions and some of the arguments for, as well as objections to, them.

Let’s begin with an example. Consider the 1998 movie, The Truman Show . In that movie the main character, Truman Burbank (played by Jim Carrey), is the star of a reality television show. However, he doesn’t know that he is. He believes he is just an ordinary person living in an ordinary neighborhood, but in fact this neighborhood is an elaborate set of a television show in which all of his friends and acquaintances are just actors. His every moment is being filmed and broadcast to a whole world of fans that he doesn’t know exists and almost every detail of his life has been carefully orchestrated and controlled by the producers of the show. For example, Truman’s little town is surrounded by a lake, but since he has been conditioned to believe (falsely) that he had a traumatic boating accident in which his father died, he never has the desire to leave the small little town and venture out into the larger world (at least at first). So consider the life of Truman as described above. Is he free or not? On the one hand, he gets to do pretty much everything he wants to do and he is pretty happy. Truman doesn’t look like he’s being coerced in any explicit way and if you asked him if he was, he would almost certain reply that he wasn’t being coerced and that he was in charge of his life. That is, he would say that he was free (at least to the same extent that the rest of us would). These points all seem to suggest that he is free. For example, when Truman decides that he would rather not take a boat ride out to explore the wider world (which initially is his decision), he is doing what he wants to do. His action isn’t coerced and does not feel coerced to him. In contrast, if someone holds a gun to my head and tells me “your wallet or your life!” then my action of giving him my wallet is definitely coerced and feels so.

On the other hand, it seems clear the Truman’s life is being manipulated and controlled in a way that undermines his agency and thus his freedom. It seems clear that Truman is not the master of his fate in the way that he thinks he is. As Goethe says in the epigraph at the beginning of this chapter, there’s a sense in which people like Truman are those who are most helplessly enslaved, since Truman is subject to a massive illusion that he has no reason to suspect. In contrast, someone who knows she is a slave (such as slaves in the antebellum South in the United States) at least retains the autonomy of knowing that she is being controlled. Truman seems to be in the situation of being enslaved and not knowing it and it seems harder for such a person to escape that reality because they do not have any desire to (since they don’t know they are being manipulated and controlled).

As the Truman Show example illustrates, it seems there can be reasonable disagreement about whether or not Truman is free. On the one hand, there’s a sense in which he is free because he does what he wants and doesn’t feel manipulated. On the other hand, there’s a sense in which he isn’t free because what he wants to do is being manipulated by forces outside of his control (namely, the producers of the show). An even better example of this kind of thing comes from Aldous Huxley’s classic dystopia, Brave New World . In the society that Huxley envisions, everyone does what they want and no one is ever unhappy. So far this sounds utopic rather than dystopic. What makes it dystopic is the fact that this state of affairs is achieved by genetic and behavioral conditioning in a way that seems to remove any choice. The citizens of the Brave New World do what they want, yes, but they seems to have absolutely no control over what they want in the first place. Rather, their desires are essentially implanted in them by a process of conditioning long before they are old enough to understand what is going on. The citizens of Brave New World do what they want, but they have no control over what the want in the first place. In that sense, they are like robots: they only have the desires that are chosen for them by the architects of the society.

So are people free as long as they are doing what they want to—that is, choosing the act according to their strongest desires? If so, then notice that the citizens of Brave New World would count as free, as would Truman from The Truman Show , since these are both cases of individuals who are acting on their strongest desires. The problem is that those desires are not desires those individuals have chosen. It feels like the individuals in those scenarios are being manipulated in a way that we believe we aren’t. Perhaps true freedom requires more than just that one does what one most wants to do. Perhaps true freedom requires a genuine choice. But what is a genuine choice beyond doing what one most wants to do?

Philosophers are generally of two main camps concerning the question of what free will is. Compatibilists believe that free will requires only that we are doing what we want to do in a way that isn’t coerced—in short, free actions are voluntary actions. Incompatibilists , motivated by examples like the above where our desires are themselves manipulated, believe that free will requires a genuine choice and they claim that a choice is genuine if and only if, were we given the choice to make again, we could have chosen otherwise . I can perhaps best crystalize the difference between these two positions by moving to a theological example. Suppose that there is a god who created the universe, including humans, and who controls everything that goes on in the universe, including what humans do. But suppose that god does this not my directly coercing us to do things that we don’t want to do but, rather, by implanting the desire in us to do what god wants us to do. Thus human beings, by doing what the want to do, would actually be doing what god wanted them to do. According to the compatibilist, humans in this scenario would be free since they would be doing what they want to do. According to the incompatibilist, however, humans in this scenario would not be free because given the desire that god had implanted in them, they would always end up doing the same thing if given the decision to make (assuming that desires deterministically cause behaviors). If you don’t like the theological example, consider a sci-fi example which has the same exact structure. Suppose there is an eccentric neuroscientist who has figured out how to wire your brain with a mechanism by which he can implant desire into you.

Suppose that the neuroscientist implants in you the desire to start collecting stamps and you do so. However, you know none of this (the surgery to implant the device was done while you were sleeping and you are none the wiser).

From your perspective, one day you find yourself with the desire to start collecting stamps. It feels to you as though this was something you chose and were not coerced to do. However, the reality is that given this desire that the neuroscientist implanted in you, you could not have chosen not to have started collecting stamps (that is, you were necessitated to start collecting stamps, given the desire). Again, in this scenario the compatibilist would say that your choice to start collecting stamps was free (since it was something you wanted to do and did not feel coerced to you), but the incompatibilist would say that your choice was not free since given the implantation of the desire, you could not have chosen otherwise.

We have not quite yet gotten to the nub of the philosophical problem of free will and determinism because we have not yet talked about determinism and the problem it is supposed to present for free will. What is determinism?

Determinism is the doctrine that every cause is itself the effect of a prior cause. More precisely, if an event (E) is determined, then there are prior conditions (C) which are sufficient for the occurrence of E. That means that if C occurs, then E has to occur. Determinism is simply the claim that every event in the universe is determined. Determinism is assumed in the natural sciences such as physics, chemistry and biology (with the exception of quantum physics for reasons I won’t explain here). Science always assumes that any particular event has some law-like explanation—that is, underlying any particular cause is some set of law- like regularities. We might not know what the laws are, but the whole assumption of the natural sciences is that there are such laws, even if we don’t currently know what they are. It is this assumption that leads scientists to search for causes and patterns in the world, as opposed to just saying that everything is random. Where determinism starts to become contentious is when we move into the human sciences, such as psychology, sociology, and economics. To illustrate why this is contentious, consider the famous example of Laplace’s demon that comes from Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1814:

We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.

Laplace’s point is that if determinism were true, then everything that every happened in the universe, including every human action ever undertaken, had to have happened. Of course humans, being limited in knowledge, could never predict everything that would happen from here out, but some being that was unlimited in intelligence could do exactly that. Pause for a moment to consider what this means. If determinism is true, then Laplace’s demon would have been able to predict from the point of the big bang, that you would be reading these words on this page at this exact point of time. Or that you had what you had for breakfast this morning. Or any other fact in the universe. This seems hard to believe, since it seems like some things that happen in the universe didn’t have to happen. Certain human actions seem to be the paradigm case of such events. If I ate an omelet for breakfast this morning, that may be a fact but it seems strange to think that this fact was necessitated as soon as the big bang occurred. Human actions seem to have a kind of independence from web of deterministic web of causes and effects in a way that, say, billiard balls don’t.

Given that the cue ball his the 8 ball with a specific velocity, at a certain angle, and taking into effect the coefficient of friction of the felt on the pool table, the exact location of the 8 ball is, so to speak, already determined before it ends up there. But human behavior doesn’t seem to be like the behavior of the 8 ball in this way, which is why some people think that the human sciences are importantly different than the natural sciences. Whether or not the human sciences are also deterministic is an issue that helps distinguish the different philosophical positions one can take on free will, as we will see presently. But the important point to see right now is that determinism is a doctrine that applies to all causes, including human actions. Thus, if some particular brain state is what ultimately caused my action and that brain state itself was caused by a prior brain state, and so on, then my action had to occur given those earlier prior events. And that entails that I couldn’t have chosen to act otherwise, given that those earlier events took place . That means that the incompatibilist position on free will cannot be correct if determinism is true. Recall that incompatibilism requires that a choice is free only if one could have chosen differently, given all the same initial conditions. But if determinism is true, then human actions are no different than the 8 ball: given what has come before, the current event had to happen. Thus, if this morning I cooked an omelet, then my “choice” to make that omelet could not have been otherwise. Given the complex web of prior influences on my behavior, my making that omelet was determined. It had to occur.

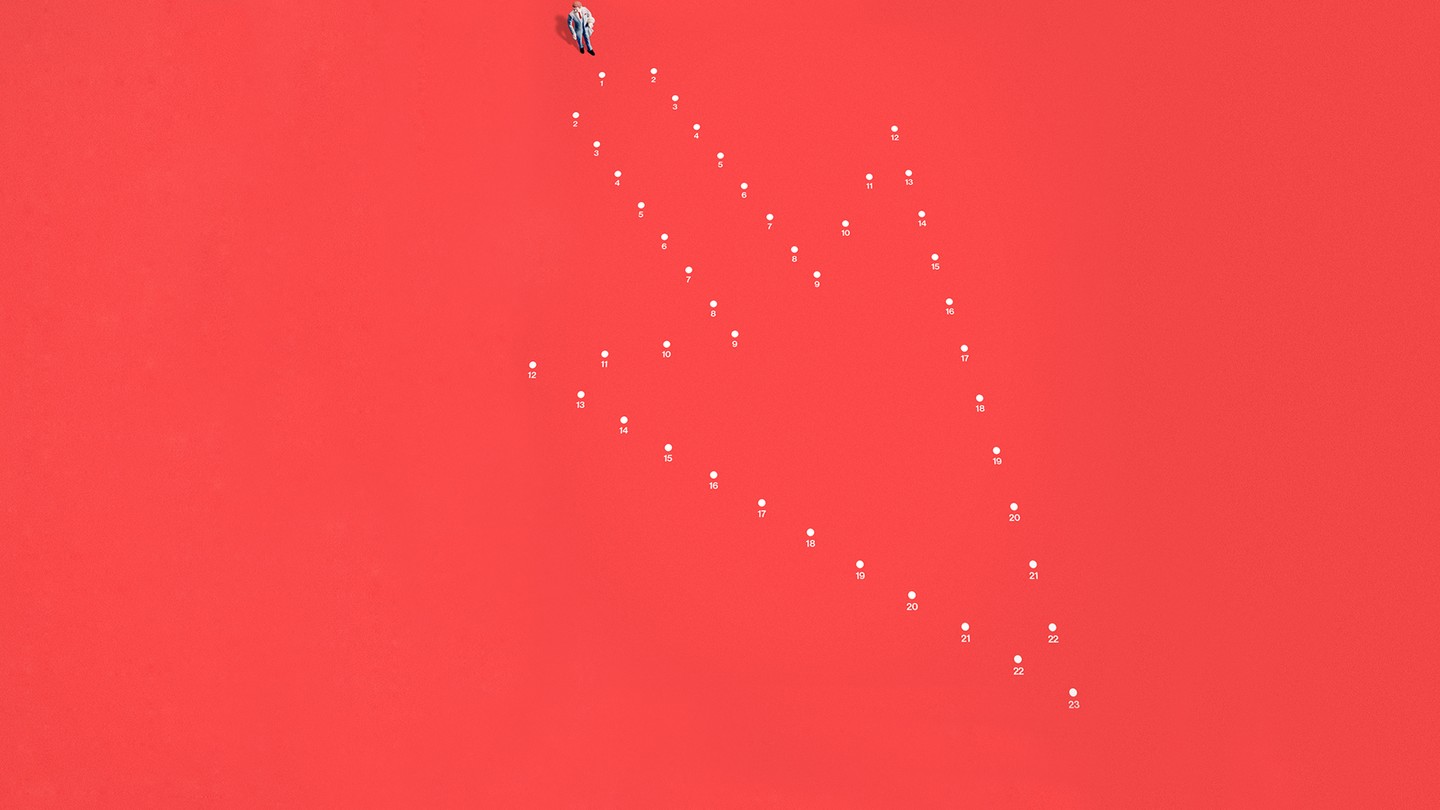

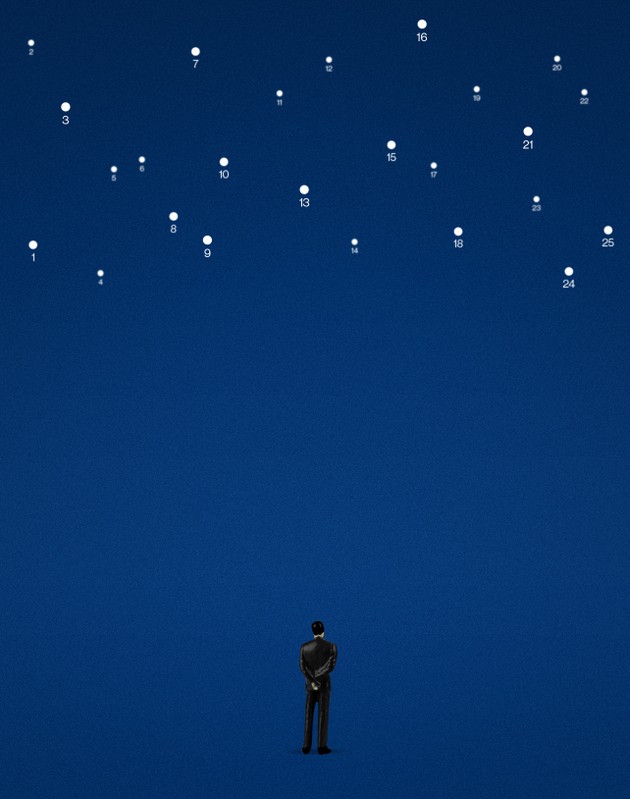

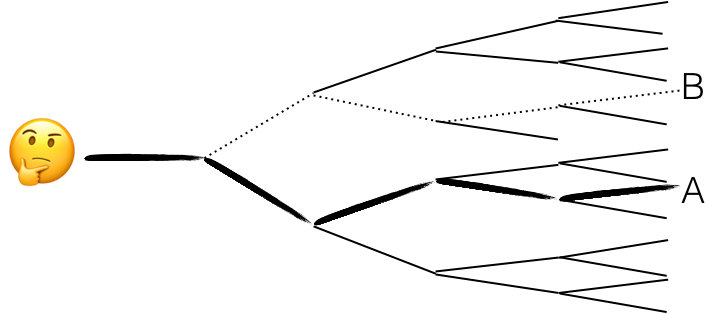

Of course, it feels to us, when contemplating our own futures, that there are many different possible ways our lives might go—many possible choices to be made. But if determinism is true, then this is an illusion. In reality, there is only one way that things could go, it’s just that we can’t see what that is because of our limited knowledge. Consider the figure below. Each junction in the figure below represents a decision I make and let’s suppose that some (much larger) decision tree like this could represent all of the possible ways my life could go. At any point in time, when contemplating what to do, it seems that I can conceive of my life going many different possible ways. Suppose that A represents one series of choices and B another. Suppose, further, that A represents what I actually do (looking backwards over my life from the future). Although from this point in time it seems that I could also have made the series of choices represented in B, if determinism is true then this is false. That is, if A is what ends up happening, then A is the only thing that ever could have happened . If it hasn’t yet hit you how determinism conflicts with our sense of our own possibilities in life, think about that for a second.

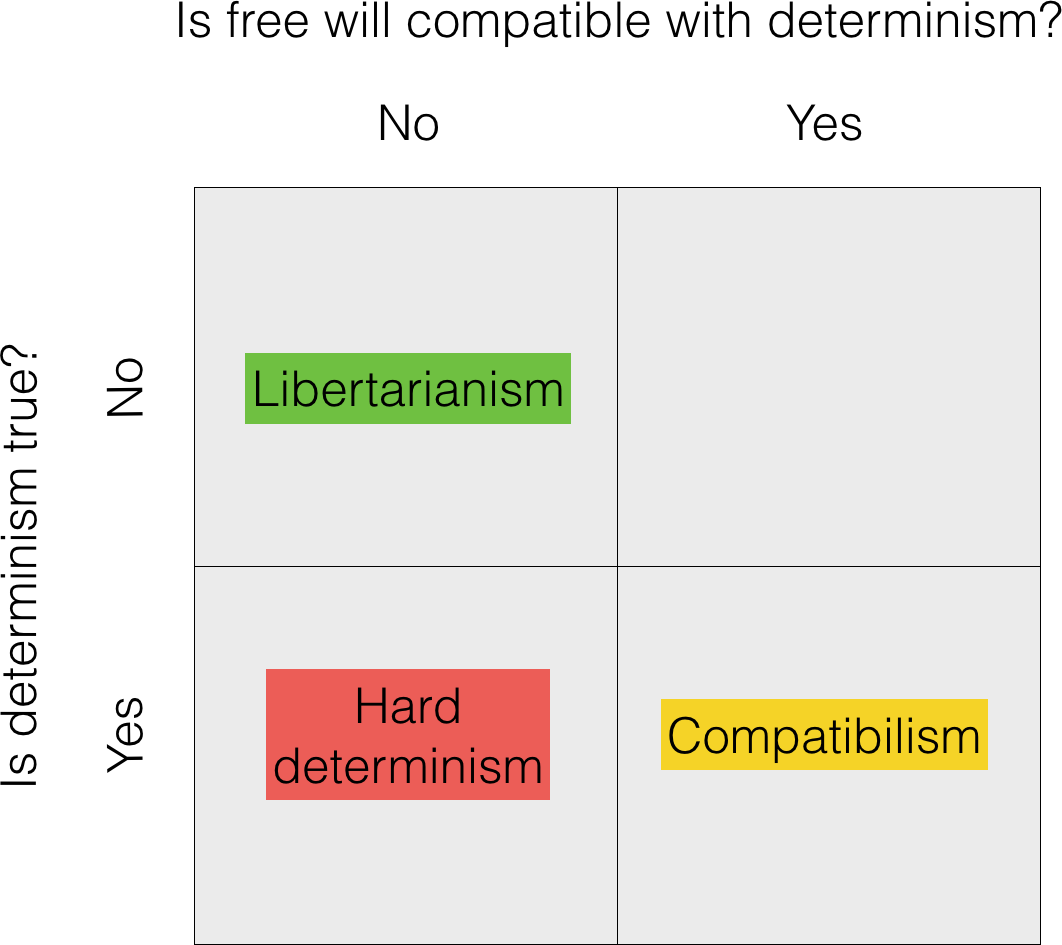

As the foregoing I hope makes clear, the incompatibilist definition of free will is incompatibile with determinism (that’s why it’s called “incompatibilist”). But that leaves open the question of which one is true. To say that free will and determinism are logically incompatible is just to say that they cannot both be true, meaning that one or the other must be false. But which one? Some will claim that it is determinism which is false. This position is called libertarianism (not to be confused with political libertarianism, which is a totally different idea). Others claim that determinism is true and that, therefore, there is no free will. This position is called hard determinism. A third type of position, compatibilism , rejects the incompatibilist definition of freedom and claims that free will and determinism are compatible (hence the name). The table below compares these different positions. But which one is correct? In the remainder of the chapter we will consider some arguments for and against these three positions on free will and determinism.

Libertarianism

Both libertarianism and hard determinism accept the following proposition: If determinism is true, then there is no free will. What distinguishes libertarianism from hard determinism is the libertarian’s claim that there is free will. But why should we think this? This question is especially pressing when we recognize that we assume a deterministic view in many other domains in life. When you have a toothache, we know that something must have caused that toothache and whatever cause that was, something else must have caused that cause. It would be a strange dentist who told you that your toothache didn’t have a cause but just randomly occurred. When the weather doesn’t go as the meteorologist predicts, we assume there must be a cause for why the weather did what it did. We might not ever know the cause in all its specific details, but assume there must be one. In cases like meteorology, when our scientific predictions are wrong, we don’t always go back and try to figure out what the actual causes were—why our predictions were wrong. But in other cases we do. Consider the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1986. Years later it was finally determined what led to that explosion (“O-ring” seals that were not designed for the colder condition of the launch). There’s a detailed deterministic physical explanation that one could give of how the failure of those O-rings led to the explosion of the Challenger. In all of these cases, determinism is the fundamental assumption and it seems almost nothing could overturn it.

But the libertarian thinks that the domain of human action is different than every other domain. Humans are somehow able to rise above all of the influences on them and make decisions that are not themselves determined by anything that precedes them. The philosopher Roderick Chisholm accurately captured the libertarian position when he claimed that “we have a prerogative which some would attribute only to God: each of us, when we really act, is a prime mover unmoved. In doing what we do, we cause certain events to happen, and nothing and no one, except we ourselves, causes us to cause those events to happen” (Chisholm, 1964). But why should we think that we have such a godlike ability? We will consider two arguments the libertarian makes in support of her position: the argument from intuitions and the argument from moral responsibility.

The argument from intuitions is based on the very strong intuition that there are some things that we have control over and that nothing causes us to do those things except for our own willing them. The strongest case for this concerns very simple actions, such as moving one’s finger. Suppose that I hold up my index finger and say that I am going to move it to the right or the to the left, but that I have not yet decided which way to move it. At the moment before I move my finger one way or the other, it truly seems to me that my future is open.

Nothing in my past and nothing in my present seems to be determining me to move my finger to the right or to the left. Rather, it seems to me that I have total control over what happens next. Whichever way I move my finger, it seems that I could have moved it the other way. So if, as a matter of fact, I move my finger to the right, it seems unquestionably true that I could have moved it to the left (and vice versa, mutatis mutandis ). Thus, in cases of simple actions like moving my finger to the right or left, it seems that the strong incompatibilist definition of freedom is met: we have a very strong intuition that no matter what I actually did, I could have chosen otherwise, were I to be given that exact choice again . The libertarian does not claim that all human actions are like this. Indeed, many of our actions (perhaps even ones that we think are free) are determined by prior causes. The libertarian’s claim is just that at least some of our actions do meet the incompatibilist’s definition of free and, thus, that determinism is not universally true.

The argument from moral responsibility is a good example of what philosophers call a transcendental argument . Transcendental arguments attempt to establish the truth of something by showing that that thing is necessary in order for something else, which we strongly believe to be true, to be true. So consider the idea that normally developed adult human beings are morally responsible for their actions. For example, if Bob embezzles money from his charity in order to help pay for a new sports car, we would rightly hold Bob accountable for this action. That is, we would punish Bob and would see punishment as appropriate. But a necessary condition of holding Bob responsible is that Bob’s action was one that he chose, one that he was in control of, one that he could have chosen not to do. Philosophers call this principle ought implies can : if we say that someone ought (or ought not) do something, this implies that they can do it (that is, they are capable of doing it). The ought implies can principle is consistent with our legal practices. For example, in cases where we believe that a person was not capable of doing the right thing, we no longer hold them morally or criminally liable. A good example of this within our legal system is the insanity defense: if someone was determined to be incapable of appreciating the difference between right and wrong, we do not find them guilty of a crime. But notice what determinism would do to the ought implies can principle. If everything we ever do had to happen (think Laplace’s demon), that means that Bob had to embezzle those funds and buy that sports car. The universe demanded it. That means he couldn’t not have done those things. But if that is so, then, by the ought implies can principle, we cannot say that he ought not to have done those things. That is, we cannot hold Bob morally responsible for those things. But this seems absurd, the libertarian will say.

Surely Bob was responsible for those things and we are right to hold him responsible. But the only we way can reasonably do this is if we assume that his actions were chosen—that he could have chosen to do otherwise than he in fact chose. Thus, determinism is incompatible with the idea that human beings are morally responsible agents. The practice of holding each other to be morally responsible agents doesn’t make sense unless humans have incompatibilist free will—unless they could have chosen to do otherwise than they in fact did. That is the libertarian’s transcendental argument from moral responsibility.

Hard determinism

Hard determinism denies that there is free will. The hard determinist is a “tough-minded” individual who bravely accepts the implication of a scientific view of the world. Since we don’t in general accept that there are causes that are not themselves the result of prior causes, we should apply this to human actions too. And this means that humans, contrary to what they might believe (or wish to believe) about themselves, do not have free will. As noted above, hard determininsm follows from accepting the incompatibilist definition of free will as well as the claim that determinism is universally true. One of the strongest arguments in favor of hard determinism is based on the weakness of the libertarian position. In particular, the hard determinist argues that accepting the existence of free will leaves us with an inexplicable mystery: how can a physical system initiate causes that are not themselves caused?

If the libertarian is right, then when an action is free it is such that given exactly the same events leading up to one’s action, one still could have acted otherwise than they did. But this seems to require that the action/choice was not determined by any prior event or set of events. Consider my decision to make a cheese omelet for breakfast this morning. The libertarian will say that my decision to make the cheese omelet was not free unless I could have chosen to do otherwise (given all the same initial conditions). But that means that nothing was determining my decision. But what kind of thing is a decision such that it causes my actions but is not itself caused by anything? We do not know of any other kind of thing like this in the universe. Rather, we think that any event or thing must have been caused by some (typically complex) set of conditions or events. Things don’t just pop into existence without being caused . That is as fundamental a principle as any we can think of. Philosophers have for centuries upheld the principle that “nothing comes from nothing.” They even have a fancy Latin phrase for it: ex nihilo nihil fir [1] . The problem is that my decision to make a cheese omelet seems to be just that: something that causes but is not itself caused. Indeed, as noted earlier, the libertarian Roderick Chisholm embraces this consequence of the libertarian position very clearly when he claimed that when we exercise our free will,

“we have a prerogative which some would attribute only to God: each of us, when we really act, is a prime mover unmoved. In doing what we do, we cause certain events to happen, and nothing and no one, except we ourselves, causes us to cause those events to happen” (Chisholm, 1964).

How could something like this exist? At this point the libertarian might respond something like this:

I am not claiming that something comes from nothing; I am just claiming that our decisions are not themselves determined by any prior thing. Rather, we ourselves, as agents, cause our decisions and nothing else causes us to cause those decisions (at least in cases where we have acted freely).

However, it seems that the libertarian in this case has simply pushed the mystery back one step: we cause our decisions, granted, but what causes us to make those decisions? The libertarian’s answer here is that nothing causes us. But now we have the same problem again: the agent is responsible for causing the decision but nothing causes the agent to make that decision. Thus we seem to have something coming from nothing. Let’s call this argument the argument from mysterious causes. Here’s the argument in standard form:

- The existence of free will implies that when an agent freely decides to do something, the agent’s choice is not caused (determined) by anything.

- To say that something has no cause is to violate the ex nihilo nihil fit principle.

- But nothing can violate the ex nihilo nihil fit principle.

- Therefore, there is no free will (from 1-3)

The hard determinist will make a strong case for premise 3 in the above argument by invoking basic scientific principles such as the law of conservation of energy, which says that the amount of energy within a closed system stays that same. That is, energy cannot be created or destroyed. Consider a billiard ball. If it is to move then it must get the required energy to do so from someplace else (typically another billiard ball knocking into it, the cue stick hitting it or someone tilting the pool table). To allow that something could occur without any cause—in this case, the agent’s decision—would be a violation of the conservation of energy principle, which is as basic a scientific principle as we know. When forced to choose between uphold such a basic scientific principle as this and believing in free will, the hard determinist opts for the former. The hard determinist will put the ball in the libertarian’s court to explain how something could come from nothing.

I will close this section by indicating how these problems in philosophy often ramify into other areas of philosophy. In the first place, there is a fairly common way that libertarians respond to the charge that their view violates basic principles such as ex nihilo nihil fit and, more specifically, the physical law of conservation of energy. Libertarians could claim that the mind is not physical—a position known in the philosophy of mind as “substance dualism” (see philosophy of mind chapter in this textbook for more on substance dualism). If the mind isn’t physical, then neither are our mental events, such our decisions.

Rather, all of these things are nonphysical entities. If decisions are nonphysical entities, there is at least no violation of the physical laws such as the law of conservation of energy. [2] Of course, if the libertarian were to take this route of defending her position, she would then need to defend this further assumption (no small task). In any case, my main point here is to see the way that responses to the problem of free well and determinism may connect with other issue within philosophy. In this case, the libertarian’s defense of free will may turn out to depend on the defensibility of other assumptions they make about the nature of the mind. But the libertarian is not the only one who will need to ultimately connect her account of free will up with other issues in philosophy. Since hard determinists deny that free will exists, it seems that they will owe us some account of moral responsibility. If, moral responsibility requires that humans have free will (see previous section), then in denying free will we seem to also be denying that humans have moral responsibility. Thus, hard determinists will face the objection that in rejecting free will they also destroy moral responsibility.

But since it seems we must hold individuals morally to account for certain actions (such as the embezzler from the previous section), the hard determinist

needs some account of how it makes sense to do this given that human being don’t have free will. My point here is not to broach the issue of how the hard determinist might answer this, but simply to show how hard determinist’s position on the problem of free will and determinism must ultimately connect with other issues in philosophy, such issues in metaethics [3] . This is a common thing that happens in philosophy. We may try to consider an issue or problem in isolation, but sooner or later that problem will connect up with other issues in philosophy.

Compatibilism

The best argument for compatibilism builds on a consideration of the difficulties with the incompatibilist definition of free will (which both the libertarian and the hard determinist accept). As defined above, compatibilists agree with the hard determinists that determinism is true, but reject the incompatibilist definition of free will that hard determinists accept. This allows compatbilists to claim that free will is compatible with determinism. Both libertarians and hard compatibilists tend to feel that this is somehow cheating, but the compatibilist attempts to convince us arguing that the strong incompatibilist definition of freedom is problematic and that only the weaker compatibilist definition of freedom—free actions are voluntary actions—will work. We will consider two objections that the compatibilist raises for the incompatibilist definition of freedom: the epistemic objection and the arbitrariness objection . Then we will consider the compatibilist’s own definition of free will and show how that definition fits better with some of our common sense intuitions about the nature of free actions.

The epistemic objection is that there is no way for us to ever know whether any one of our actions was free or not. Recall that the incompatibilist definition of freedom says that a decision is free if and only if I could have chosen otherwise than I in fact chose, given exactly all the same conditions. This means that if we were, so to speak, rewind the tape of time and be given that decision to make over again, we could have chosen differently. So suppose the question is whether my decision to make a cheese omelet for breakfast was free. To answer this question, we would have to know when I could have chosen differently. But how am I supposed to know that ? It seems that I would have to answer a question about a strange counterfactual : if given that decision to make over again, would I choose the same way every time or not? How on earth am I supposed to know how to answer that question? I could say that it seems to me that I could make a different decision regarding making the cheese omelet (for example, I could have decided to eat cereal instead), but why should I think that that is the right answer? After all, how things seem regularly turn out to be not the case—especially in science. The problem is that I don’t seem to have any good way of answering this counterfactual question of what I would choose if given the same decision to make over again. Thus the epistemic objection [4] is that since I have no way of knowing whether I would/wouldn’t make the same decision again, I can never know whether any of my actions are free.

The arbitrariness objection is that it turns our free actions into arbitrary actions. And arbitrary actions are not free actions. To see why, consider that if the incompatibilist definition is true, then nothing determines our free choices, not even our own desires . For if our desires were determining our choices then if we were to rewind the tape of time and, so to speak, reset everything— including our desires —the same way, then given those same desires we would choose the same way every time. And that would mean our choice was not free, according to the incompatbilist. It is imperative to remember that incompatibilism says that if an action is not free if it is determined ( including if it is determined by our own desires ). But now the question is: if my desires are not causing my decision, what is? When I make a decision, where does that decision come from, if not from my desires and beliefs? Presumably it cannot come from nothing ( ex nihilo nihil fit ). The problem is that if the incompatibilist rejects that anything is causing my decisions, then how can my decisions be anything but arbitrary?

Presumably an arbitrary decision—a decision not driven by any reason at all—is not an exercise of my freedom. Freedom seems to require that we are exercising some kind of control over my actions and decisions. If my action or decision is arbitrary that means that no reason or explanation of the action/decision can be given. Here’s the arbitrariness objection cast as a reductio ad absurdum argument:

- A free choice is one that isn’t determined by anything, including our desires. [incompatibilist definition of freedom]

- If our own desires are not determining our choices, then those choices are arbitrary.

- If a choice is arbitrary then it is not something over which we have control

- If a choice isn’t something over which we have control, then it isn’t a free choice

- Therefore, a free choice is not a free choice (from 1-4)

A reductio ad absurdum argument is one that starts with a certain assumption and then derives a contradiction from that assumption, thereby showing that assumption must be false. In this case, the incompatibilist’s definition of a free choice leads to the contradiction that something that is a free choice isn’t a free choice.

What has gone wrong here? The compatibilist will claim that what has gone wrong is incompatibilist’s idea that a free action must be one that isn’t caused/determined by anything. The compatibilist claims that free actions can still be determined, as long as what is determining them is our own internal reasons, over which we have some control, rather than external things over which we have no control. Free choices, according to the compatibilist, are just choices that are caused by our own best reasons . The fact that, given the exact same choices, I couldn’t have chosen otherwise doesn’t undermine what freedom is (as the incompatibilist claims) but defines what it is. Consider an example. Suppose that my goal is to spend the shortest amount of time on my commute home from work so that I can be on time for a dinner date. Also suppose, for simplicity, that there are only three possible routes that I can take: route 1 is the shortest, whereas route 2 is longer but scenic and 3 is more direct but has potentially more traffic, especially during rush hour. I am leaving early from work today so that I can make my dinner date but before I leave, I check the traffic and learn that there has been a wreck on route 1. Thus, I must choose between routes 2 and 3. I reason that since I am leaving earlier, route 3 will be the quickest since there won’t be much traffic while I’m on my early commute home. So I take route 3 and arrive home in a timely manner: mission accomplished. The compatibilist would say that this is a paradigm case of a free action (or a series of free actions). The decisions I made about how to get home were drive both by my desire to get home quickly and also by the information I was operating with. Assuming that that information was good and I reasoned well with it and was thereby able to accomplish my goal (that is, get home in a timely manner), then my action is free. My action is free not because my choices were undetermined, but rather because my choices were determined (caused) by my own best reasons—that is, by my desires and informed beliefs. The incompatibilist, in contrast, would say that an action is free only if I could have chosen otherwise, given all the same conditions again. But think of what that would mean in the case above! Why on earth would I choose routes 1 or 2 in the above scenario, given that my most pressing goal is to be able to get to my dinner date on time? Why would anyone knowingly choose to do something that thwarts their primary goals? It doesn’t seem that, given the set of beliefs and desires that I actually had at the time, I could have chosen otherwise in that situation. Of course, if you change the information I had (my beliefs) or you change what I wanted to accomplish (my desires), then of course I could have acted otherwise than I did. If I didn’t have anything pressing to do when I left work and wanted a scenic and leisurely drive home in my new convertible, then I probably would have taken route 2! But that isn’t what the incompatibilist requires for free will. As we’ve seen, they require the much stronger condition that one’s action be such that it could have been different even if they faced exactly the same condition over again. But in this scenario that would be an irrational thing to do. Of course, if one’s goal were to be irrational and to thwart one’s own desires, I suppose they could do that. But that would still seem to be acting in accordance with one’s desires.

Many times free will is treated as an all or nothing thing, either humans have it or they don’t. This seems to be exactly how the libertarian and hard determinist see the matter. And that makes sense given that they are both incompatibilists and view free will and determinism like oil and water—they don’t mix. But it is interesting to note that it is common for us to talk about decisions, action, or even whole lives (or periods of a life) as being more or less free . Consider the Goethe quotation at the beginning of this chapter: “none are more enslaved than those who falsely believe they are free.” Here Goethe is conceiving of freedom as coming in degrees and claiming that those who think they are free but aren’t as less free than those who aren’t free and know it. But this way of speaking implies that free will and determinism are actually on a continuum rather than a black and white either or. The compatibilist can build this fact about our ordinary ways of speaking about freedom into an argument for their position. Call this the argument from ordinary language . The argument from ordinary language is that only compatibilism is able to accommodate our common way of speaking about freedom coming in degrees—that is, as actions or decisions being more or less free. The libertarian can’t account for this since the libertarian sees freedom as an all or nothing matter: if you couldn’t have done otherwise then your action was not truly free; if you could have done otherwise, then it was. In contrast, the compatibilist is able to explain the difference between more/less free action on the continuum. For the compatibilist, the freest actions are those in which one reasons well with the best information, thus acting for one’s own best reasons, thus furthering one’s interests. The least free actions are those in which one lacks information and reason poorly, thus not acting for one’s own best reasons, thus not furthering one’s interests. Since reasoning well, being informed, and being reflective are all things that come in degrees (since one can possess these traits to a greater or lesser extent) and since these attribute define what free will is for the compatibilist, it follows that free will comes in degrees. And that means that the compatibilist is able to make sense or a very common way that we talk about freedom (as coming in degrees) and thus make sense of ourselves, whereas the libertarian isn’t.

There’s one further advantage that compatibilists can claim over libertarians. Libertarians defend the claim that there are at least some cases where one exercises one’s free will and that this entails that determinism is false. However, this leaves totally open the extent of human free will. Even if it were true that there are at least some cases where humans exercise free will, there might not be very many instances and/or those decisions in which we exercise free will might be fairly trivial (for example, moving one’s finger to the left or right). But if it were to turn out that free will was relatively rare, then even if the libertarian were correct that there are at least some instances where we exercise free will, it would be cold comfort to those who believe in free will. Imagine: if there were only a handful of cases in your life where your decision was an exercise of your free will, then it doesn’t seem like you have lived a life which was very free. In other words, in such a case, for all practical purposes, determinism would be true.

Thus, it seems like the question of how widespread free will is is an important one. However, the libertarian seems unable to answer it for reasons that we’ve already seen. Answering the question requires knowing whether or not one could have acted otherwise than one in fact did. But in order to know this, we’d have to know how to answer a strange counterfactual—whether I could have acted differently given all the same conditions. As noted earlier (“the epistemic objection”), this raises a tough epistemological question for the libertarian: how could he ever know how to answer this question? And so how could he ever know whether a particular action was free or not? In contrast, the compatibilist can easily answer the question of how widespread free will is: how “free” one’s life is depends on the extent to which one’s actions are driven by their own best reasons. And this, in turn, depends on factors such as how well-informed, reflective, and reasonable a person is. This might not always be easy to determine, but it seems more tractable than trying to figure out the truth conditions of the libertarian’s counterfactual.

In short, it seems that compatibilism has significant advantages over both libertarianism and hard determinism. As compared to the libertarian, compatibilism gives a better answer to how free will can come in degrees as well as how widespread free will is. It also doesn’t face the arbitrariness objection or the epistemic objection. As compared to the hard determinist, the compatibilist is able to give a more satisfying answer to the moral responsibility issue. Unlike the hard determinist, who sees all action as equally determined (and so not under our control), the compatibilist thinks there is an important distinction within the class of human actions: those that are under our control versus those that aren’t. As we’ve seen above, the compatibilist doesn’t see this distinction as black and white, but, rather, as existing on a continuum. However, a vague boundary is still a boundary. That is, for the compatibilist there are still paradigm cases in which a person has acted freely and thus should be held morally responsible for that action (for example, the person who embezzles money from a charity and then covers it up) and clear cases in which a person hasn’t acted freely (for example, the person who was told to do something by their boss but didn’t know that it was actually something illegal). The compatibilist’s point is that this distinction between free and unfree actions matters, both morally and legally, and that we would be unwise to simply jettison this distinction, as the hard determinist does. We do need some distinction within the class of human actions between those for which we hold people responsible and those for which we don’t. The compatibilist’s claim is that they are able to do with while the hard determinist isn’t. And they’re able to do it without inheriting any of the problems of the libertarian position.

Study questions

- True or false: Compatibilists and libertarians agree on what free will is (on the concept of free will).

- True or false: Hard determinists and libertarians agree that an action is free only when I could have chosen otherwise than I in fact chose.

- True or false: the libertarian gives a transcendental argument for why we must have free will.

- True or false: both compatibilists and hard determinists believe that all human actions are determined.

- True or false: compatibilists see free will as an all or nothing matter: either an action is free or it isn’t; there’s no middle ground.

- True or false: compatibilists think that in the case of a truly free action, I could have chosen otherwise than I in fact did choose.

- True or false: One objection to libertarianism is that on that view it is difficult to know when a particular action was free.

- True or false: determinism is a fundamental assumption of the natural sciences (physics, chemistry, biology, and so on).

- True or false: the best that support the libertarian’s position are cases of very simple or arbitrary actions, such as choosing to move my finger to the left or to the right.

- True or false: libertarians thinks that as long as my choices are caused by my desires, I have chosen freely.

For deeper thought

- Consider the Shopenhauer quotation at the beginning of the chapter. Which of the three views do you think this supports and why?

- Consider the movie The Truman Show . How would the libertarian and compatibilist disagree regarding whether or not Truman has free will?

- Consider the Tolstoy quote at the beginning of the chapter. Which of the three views does this support and why?

- Consider a child being raised by white supremacist parents who grows up to have white supremacist views and to act on those views. As a child, does this individual have free will? As an adult, do they have free will? Defend your answer with reference to one of the three views.

- Consider the eccentric neuroscientist example (above). How might a compatibilist try to show that this isn’t really an objection to her view? That is, how might the compatibilist show that this is not a case in which the individual’s action is the result of a well-informed, reflective choice?

- Actually, the phrase was originally a Latin phrase, not an English one because at the time in Medieval Europe philosophers wrote in Latin. ↵

- On the other hand, if these nonphysical decisions are supposed to have physical effects in the world (such as causing our behaviors) then although there is no problem with the agent’s decision itself being uncaused, there would still be a problem with how that decision can be translated into the physical world without violating the law of conservation of energy. ↵

- One well-known and influential attempt to reconcile moral responsibility with determinism is P.F. Strawson’s “Freedom and Resentment” (1962). ↵

- The term “epistemic” just denotes something relating to knowledge. It comes from the Greek work episteme, which means knowledge or belief. ↵

Introduction to Philosophy Copyright © by Matthew Van Cleave is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Free Will

- Frontiers - Frontiers in Human Neuroscience - Free Will and Neuroscience: From explaining freedom away to new ways of operationalizing and measuring it

- Simply Psychology - Freewill vs Determinism in Psychology

- Humanities LibreTexts - Free Will, Determinism, and Responsibility

- University of Central Florida Pressbooks - The problem of free will and determinism

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Physiology of Free Will

- Cal Poly Pomona - Angels, Demons, and Free Will

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Free Will

- University of Notre Dame - Is free will possible?

- Nature - Is free will an illusion?

- Psychology Today - Free Will

- Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Free Will

- London School of Economics and Political Science - Free Will: The Basic

free will , in philosophy and science , the supposed power or capacity of humans to make decisions or perform actions independently of any prior event or state of the universe. Arguments for free will have been based on the subjective experience of freedom, on sentiments of guilt, on revealed religion , and on the common assumption of individual moral responsibility that underlies the concepts of law, reward, punishment, and incentive. In theology , the existence of free will must be reconciled with God’s omniscience and benevolence and with divine grace , which allegedly is necessary for any meritorious act. A prominent feature of existentialism is the concept of a radical, perpetual, and frequently agonizing freedom of choice . Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–80), for example, spoke of the individual “condemned to be free.”

The existence of free will is denied by some proponents of determinism , the thesis that every event in the universe is causally inevitable. Determinism entails that, in a situation in which people make a certain decision or perform a certain action, it is impossible that they could have made any other decision or performed any other action. In other words, it is never true that people could have decided or acted otherwise than they actually did. Philosophers and scientists who believe that determinism in this sense is incompatible with free will are known as “hard” determinists.

In contrast, so-called “soft” determinists, also called compatibilists, believe that determinism and free will are compatible after all. In most cases, soft determinists attempt to achieve this reconciliation by subtly revising or weakening the commonsense notion of free will. Contemporary soft determinists have included the English philosopher G.E. Moore (1873–1958), who held that acting freely means only that one would have acted otherwise had one decided to do so (even if, in fact, one could not have decided to do so), and the American philosopher Harry Frankfurt (born 1929), who has argued that acting freely amounts to identifying with or approving of one’s own desires (even if those desires are such that one cannot help but act on them).

The extreme alternative to determinism is indeterminism , the view that at least some events have no deterministic cause but occur randomly, or by chance. Indeterminism is supported to some extent by research in quantum mechanics , which suggests that some events at the quantum level are in principle unpredictable (and therefore random). Philosophers and scientists who believe that the universe is indeterministic and that humans possess free will are known as “libertarians” (libertarianism in this sense is not to be confused with the school of political philosophy called libertarianism ). Although it is possible to hold that the universe is indeterministic and that human actions are nevertheless determined, few contemporary philosophers defend this view.

Libertarianism is vulnerable to what is called the “intelligibility” objection, which points out that people can have no more control over a purely random action than they have over an action that is deterministically inevitable; in neither case does free will enter the picture. Hence, if human actions are indeterministic, free will does not exist. See also free will and moral responsibility .

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Hume on Free Will

But to proceed in this reconciling project with regard to the question of liberty and necessity; the most contentious question of metaphysics, the most contentious science… —David Hume (EU 8.23/95)

It is widely accepted that David Hume’s contribution to the free will debate is one of the most influential statements of the “compatibilist” position, where this is understood as the view that human freedom and moral responsibility can be reconciled with (causal) determinism. Hume’s arguments on this subject are found primarily in the sections titled “Of liberty and necessity”, as first presented in A Treatise of Human Nature (2.3.1–2) and, later, in a slightly amended form, in the Enquiry concerning Human Understanding (sec. 8). Although both contributions share the same title, there are, nevertheless, some significant differences between them. This includes, for example, some substantial additions in the Enquiry discussion as it relates to problems of religion, such as predestination and divine foreknowledge. These differences should not, however, be exaggerated. Hume’s basic strategy and compatibilist commitments remain much the same in both works.