- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

A Short History of ESKOM, Part 1 (1923-2001)

This short history of Electrical Supply Commission (ESKOM) aims to provide an overview of the history of the power utility over its first seventy-eight years. The significance of these dates is as follows: ESKOM was started in 1923 by the government and prominent industrialists and by 2001 it was a state-owned enterprise. During the abovementioned period, ESKOM had several feats and failings. This article endeavours to extract some lessons/reflections for the present from ESKOM’s past. This is especially important in 2022 where South Africa has had the most hours of load shedding on record and is seeking different solutions to power challenges amid a looming global environmental crisis.

Early Electrification in South Africa

The mineral revolution spurred electrification in South Africa. Kimberly was the first city to be electrified with streetlights installed in 1882, fifteen years after the discovery of diamonds in 1867. [1] More than diamond mining, the discovery of gold in 1882 was the engine behind electrification in South Africa, with towns on the Witwatersrand reef being electrified shortly after. [2] In 1891, Johannesburg was electrified and by the early 1900s, most large cities in the country had electricity. [3] The discovery of gold had concentrated demand for coal – a primary resource for electricity generation – and from the late 1800s, gold mining was tied to electricity. [4] Power stations were placed near goldmines, as goldmines were the centres of energy consumption, leading to the interdependence between energy generation and mineral discovery. [5]

Ben Fine and Zavareh Rustomjee argue that the “minerals-energy complex” lies at the heart of the South African economy. In their book, written in 1996, they argue that South Africa’s economic strength lies in the mining and energy sectors, which are interdependent and mutually beneficial. [6] The genesis of South Africa’s energy generation fits into this frame; the initial boom of gold mining, which required energy and electricity generated from coal. Initially, mining houses would generate their own electricity and coal mining capitalists would supply coal to individual mining houses. [7]

The Victoria Falls and Transvaal Power Company (VFTPC) was the principal generator of electricity in the early 1900s. It was started by Cecil John Rhodes in 1906 (himself a diamond mining magnate) and aimed to provide hydro-electric power from Victoria Falls, but eventually opted for the “abundant coal resources in the Transvaal, where operations at the time […] were easy and offered substantial profits”. [8] In this early period, the 1900s, South Africa was generating more electricity than the English cities of “London, Birmingham and Sheffield combined”. [9]

Gold mining effectively regulated the price of electricity, as they needed cheap electricity to function profitably. [10] The threat of a VFTPC monopoly over electricity production was an obstacle to the seamless profits of large mining houses, and added “the need for economies of scale and reliability”. This led to the centralisation of electricity production. The Transvaal Power Act (1910) effectively put electricity under state authority and as a public service. It was a watershed moment in an energy landscape which was characterised by the “fragmentation of electricity production”. [11] In the 1920s, electricity “shifted to the national arena” to support industrial growth, particularly in the fields of manufacturing and transport.

Electrification was the “ticket to industrialisation” and Prime Minister Jan Smuts had managed to unlock this capacity through an agreement with Sir William Hoy of the South African Railways (SAR). [12] The SAR had sought to supply railways with electricity from private companies or municipalities. The railway industry was becoming increasingly integral to the mineral-industrial complex partly to transport black workers from in and around southern Africa and to establish rail routes serving the coal collieries. [13] The need to reduce the cost of electricity saw the Merz Commission established. This commission recommended greater state intervention and that an act be established to regulate and unify electrical supply. The 1922 Electricity Act was drafted by Prime Minister Jan Smuts, the General Manager of the SAR and key mining experts including engineer Hendrik Van Der Bijl . [14]

The Creation of ESCOM

The 1922 Electricity Act set up two institutions in 1923: the Electricity Control Board (ECB) and the Electricity Supply Commission (ESCOM). ESCOM would supply electricity on a national scale and embark on new projects and investments while the ECB would regulate the costs of electricity. This effort to create a national power supplier and regulatory body jarred sharply with the VFTPC; Bill Freund notes that Smuts had to struggle against the company for two parliamentary years to firmly establish it. [15]

“Brilliant scientist” Hendrik Van der Bijl was enticed back to South Africa from America to be appointed as ESCOM’s first chairman. [16] ESCOM, designated as a public-private entity, was exempt from paying taxes and independent of parliament. As Freund notes, “The idea behind ESCOM was to make it as independent as possible from both private capital and from any political interest within the state”. [17] Van Der Bijl had managed to create a zone of breathing space between ESCOM and the government which allowed for “relative autonomy and technopolitical action”. This would avoid the “unpredictable ups and downs of political influence”. Jaglin and Dubresson suggest that throughout Van Der Bijl’s tenure and beyond, ESCOM’s leaders employed “technopolitical choices to promote a socio-political vision aligned to that of the government”. [18]

Despite it being at arms-length from the government, ESCOM had a duty to ensure that all of its projects were in the public interest and that electricity was supplied at the lowest possible cost. The electricity produced was reserved for mines, industry, railways and the white public. Leonard Gentle suggests that the mandate of ESCOM supplying electricity at “neither a profit nor at a loss” de-commodified electricity supply and resembled a type of regulated or Keynesian racial capitalism. [19] It was hoped that ESCOM would be able to set up conditions for private firms to disappear within thirty-five years of its inception. [20]

During the 1930s, ESCOM and the Iron and Steel Corporation of South Africa (ISCOR) (which was started one year after ESCOM in 1924) helped link the private sector to the government and were the growth engines behind the growth of the railways, mine houses and other industry. Yet, as Fine and Rustomjee argue, electrification and steel production did not lead to the extensive diversification of the economy, owing to the already entrenched minerals-energy complex. The structure of the economy thus required a cross-pollination between the minerals and energy industries for their mutual benefit rather than greater diversification. [21] Mining, steel production and industrialisation were “underpinned by cheap labour and cheap electricity”. This situation was a “win-win” for “gold mines, coal mines and municipalities”. [22]

Initially, ESCOM would supply electricity to the railways while VFTPC would supply electricity to the mines (at times ESCOM would supply electricity at cost price to the VFTPC). [23] During the late 1920s and early 1930s, ESCOM began building power stations but was still small in comparison to the VFTPC. [24] Following the abandonment of the Gold Standard in 1932 and the build-up to World War 2 (WW2) , the South African economy boomed and ESCOM’s output increased by five times between 1933 and 1948. Part of this growth was due to ESCOM taking over generation capacities at the request of municipalities from the mid-1940s. [25]

Bill Freund has posited that the establishment of ESCOM signalled the developmental ambitions of the government. Leading engineers like Van Der Bijl and H.J. Van Eck would lead ESCOM’s innovation, particularly with the transformation of coal into oil. In the annual report of ESCOM in 1948, ESCOM firmly placed itself to be a central part of industrialisation and the government’s developmental vision. Yet a more radical version of the state’s developmentalism was highlighted with the expropriation of the VFTPC in 1948. [26]

The VFTPC was a foreign company making large profits from electricity production. The opening of large, ore-rich Orange Free State goldmines required an abundance of cheap electricity, especially considering the depth of the gold and the amount of air-conditioning needed. ESCOM had an “irreplaceable niche” among mining interests, particularly with Harry Oppenheimer’s Anglo-American. Together with the government, Anglo-American helped ESCOM expropriate the VFTPC for £15, 5 million just prior to the National Party (NP) victory in 1948. This kind of state intervention was allowed under the 1910 Transvaal Power Act. [27]

Throughout the first twenty years of Van Der Bijl’s leadership, ESCOM had begun to build large coal-fired power stations. Van Der Bijl and Smuts (now at the end of his second term) had a simple and consistent aim: to provide cheap electricity. Controlling electricity and providing it at a cheap price was at the centre of “minerals-energy complex”. [28] The elimination of competition in the electricity sector, which outgoing Prime Minister Jan Smuts noted as “wasteful competition”, [29] was the only way to achieve smooth and nationally oriented industrialisation.

ESCOM During Apartheid

With the growth of ESCOM’s coal-fired power stations, it expanded its workforce considerably. By the mid-1950s, ESCOM had 13,000 employees. Many of these salaried jobs were reserved for white workers and were a mechanism of the state to appease their constituency through job reservation . Entrenched in earlier years of ESCOM expansion, the power utility was a “technical system” for white society and a tool to upskill white people who had upward mobility through good jobs. [30] At the same time, inspired by their arms-length from the government and technical expertise, ESCOM was an arena of “professional competence”, whereby engineers were respected and the large coal-fired power stations made ESCOM effective. [31]

Coal had underpinned the electricity sector until the beginning of Apartheid and this was to expand in the coming years. In the late 1940s, gold mining consumed 59% of all electricity. To meet this demand, ESCOM helped develop some of the most advanced coal-fired plants in the world. [32] Yet from the NP win in 1948, the balance of the minerals-energy complex became increasingly delicate. From the late 1940s, ESCOM’s coal contracts in the Northern Transvaal (today Mpumalanga ) were largely held by Afrikaner capital (with ESCOM historically being a key instrument in enabling the growth of Afrikaner capital).

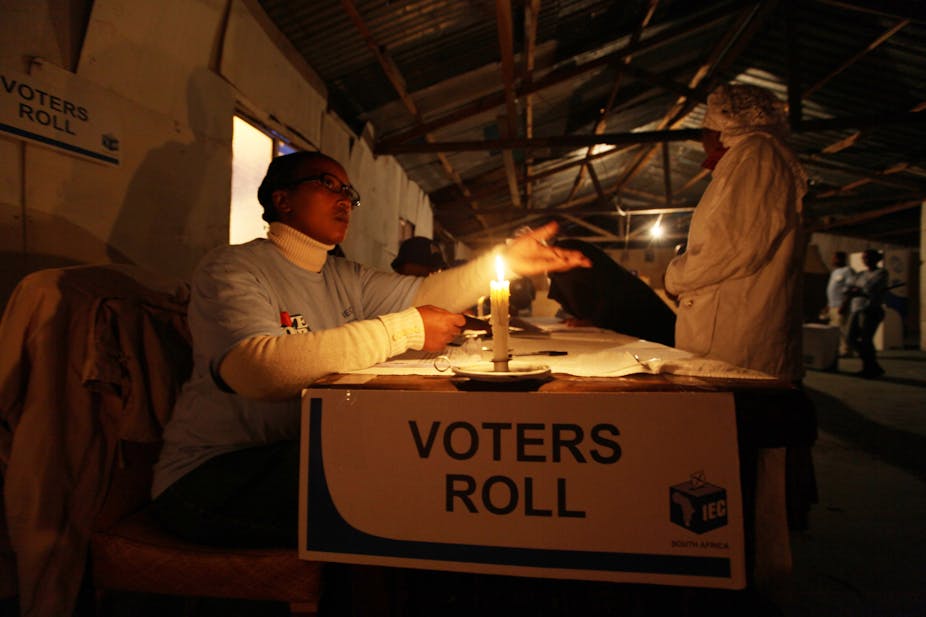

In 1948, Afrikaans coal mine owners decided to export coal instead of using it for domestic consumption, particularly because of ideological competition between Afrikaner nationalist interests and British imperial mining interests. With the expanding gold mines in the Orange Free State (OFS), the competition led to severe power shortages and load-shedding or “consumption reduction” between 1948 and 1953. In response to this, ESCOM increased their power stations. Between 1948 and 1975 electricity generation increased sixfold. [33]

Fine and Rustomjee suggest that ESCOM, South African Synthetic Oil Ltd (SASOL) and the Armaments Corporation of South Africa (ARMSCOR) were propelled by the growing interpenetration between Afrikaner and English capital. Evidence of this was seen in that coal contracts were given to large mining companies, like Anglo American, and the Federale Mynbou (then a subsidiary of SANLAM ). [34] These state corporations, including ISCOR ESCOM, ISCOR impressed foreigners (especially those from the USA) as did the government’s effort to expand them. [35]

The 1960s were characterised by the violent state repression of black resistance to assist the growth of the economy for Apartheid interests. The high economic growth of the 1960s was met with new power stations being built, some of which were the “most advanced” and “modern” in the world. These new power stations became interlocked into a national grid which was developed between 1969 and 1973. [36] ESCOM’s processes of transmission were fully automated and the entire grid could be controlled remotely by technicians from the national control centre in Simmerpan, Germiston. [37] Further growth in demand in the 1970s meant that ESCOM built new power stations, most of these being coal-fired. Modern technology was used to burn low-grade coal in large power stations like Duvha, Hendrina and Arnot (which still supply electricity today). [38]

In the 1970s, electricity was in huge demand domestically (as households began to use more appliances), but coal too was in high demand internationally after the oil price shot up. The coal industry thus exported from the 1970s, drawing from increasingly large coal reserves throughout the country. While the coal price was set to provide cheap electricity to ESCOM, the 1970s saw coal exported and many gold mining companies begin to own coal mines (eventually two-thirds of coal mines were owned by big gold mining companies). Evidence of the change in coal strategy is showcased by the fact that domestic coal consumption dropped by 52% from 90% in 1970 to 38% in 1985. So too, the Coal Resource Act of 1985 declared that price-fixing (to keep the price of coal low) be terminated. [39] Also in response to the oil crisis and growing international isolation, ESCOM adopted a coal-to-liquid strategy. [40]

During the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, ESCOM built 13 new coal-fired power stations. [41] The power giant also began to explore new forms of electricity. After uranium was discovered as being a by-product of gold mining, ESCOM sought to explore nuclear energy as an option (unfortunately, the South African government exported it, to ESCOM’s dismay). [42] Particularly after the oil price hike in 1973, the Apartheid government could justify nuclear energy. ESCOM bought the farm where Koeberg is now and embarked on a venture to build a nuclear power station with a French company. [43] The nuclear project was planned to open in 1976 but it was delayed because of an explosion of a reactor by a worker who was a member of the African National Congress (ANC). Eventually, the reactors were opened in 1984 and 1985 respectively. [44]

Freund asserts that Koeberg was not a success – South Africa had to import uranium because international prices were lower, making nuclear power uneconomic. Nuclear energy thus was not well integrated into government planning (partly highlighting coal’s dominance in the energy sector). ESCOM eventually took over the power station and helped pay for its deficits – it is estimated that ESCOM absorbed over R31 million of the costs and debts of Koeberg up until 2000. Eventually, nuclear power and ESCOM were decoupled in favour of the relationship between nuclear power and military equipment giant ARMSCOR. [45] Another ESCOM development was the Cahora Bassa hydroelectric power station in Mozambique. Owing to technology deficits in Mozambique, ESCOM bought Direct Current (DC) electricity in Mozambique and used technologically advanced thyristors to convert it to Alternating Current (AC). [46]

The expansion of ESCOM’s generation capacity during the 1960s and 1970s led to many black workers being employed in technical positions which were classed as “operations assistants” to side-step Apartheid legislation which reserved skilled work for white workers. [47]

ESCOM in the Period of Apartheid’s Economic Reforms

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the growing isolation of the Apartheid government, due to the intensification of the anti-Apartheid movement and international sanctions, coupled with the growth of neoliberalism globally meant that investment and government funding for state corporations dropped. [48]

Economic deregulation grew from the 1970s. America cancelled the Bretton Woods agreement in 1971 whereby the price of gold was set, which meant that the gold price began to fluctuate and old systems of controlling the prices of steel and electricity were put under significant pressure. In response to this, then President PW Botha endorsed a policy to stop setting prices. [49] Freund notes that ESCOM had “detached itself from the other parastatals and much of the state by the 1980s”. [50]

As previously mentioned, ESCOM had built a fleet of coal-fired power stations which had swelled their generation capacities. In the late 1970s and 1980s, this excess capacity hit financial constraints. The demand for electricity slowed because of low economic growth. ESCOM engineers had over-estimated demand. With lower growth, the massive new power stations had a less flexible generation, were receiving poor quality coal and had high maintenance. [51]

ESCOM also struggled with financing and incurred a lot of debt. Their option to borrow money from international organisations was increasingly curtailed amid growing international isolation. They were forced to borrow money domestically at high-interest rates resulting in electricity prices being hiked by 166% in 1977. [52] The autonomy for ESCOM to expand internationally was, therefore “hermetic” by the mid-1980s. In the early 1980s, ESCOM had also borrowed a lot of money from financial institutions because of a record gold price, but after the gold price dropped, ESCOM sat with massive debt which culminated in the 1985 debt crisis. [53]

It was within this context that the De Villiers Commission was established in 1983. The De Villiers Commission proposed a two-tier governance structure of ESCOM headed by Ian McRae and Johannes Maree. The commission recommended that the “public interest clause” of ESCOM’s mandate be scrapped and that the parastatal must operate on a commercial basis. The “public interest clause” was replaced by a more liberal commitment “to provide the system by which the electricity needs of the consumer may be satisfied in the most cost-effective manner, subject to resource constraints and the national interest”. [54] This fitted in with international neoliberal ideas whereby public utilities “either be privatised or operate on a commercial basis”. [55]

The De Villiers Commission led to the Electricity Act of 1987. The public interest clause was repealed. ESCOM thus became ESKOM (the new name was a combination between ESCOM and the Afrikaans name for the power utility Elektrisiteitsvoorsieningskommissie (EVKOM) to make ESKOM), which was now commercial and responsible for its own profits and losses. [56] Market mechanisms were targeted to get cheaper electricity while ESKOM rapidly cut spending, stopping the construction of new power stations, reducing staff (from 66,000 in 1985 to 46,000 in 1991) and closing old power stations. [57] ESKOM chose corporatisation over privatisation. This meant that they were a commercial company with its own strategies and with a distance from government, but committed to supplying electricity to South Africa. [58]

ESKOM During Democracy

Jaglin and Dubresson suggest that just before the ANC came into power, they had an “ambiguous advantage”. Because of tax exemptions, low-cost coal and the reduction of investment spending “ESKOM produced the lowest cost electricity in the world”. [59] New demand for electricity from ESKOM grew from domestic consumption which rapidly expanded in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The 1990s were a period of intense negotiations which included both imperatives to liberalise and redistribute. This can be seen in the differing economic policies adopted by the ANC after Apartheid and the definitions of development. Internationalisation met an expanded minerals-energy complex and the status of public organisations changed. [60]

In 1991, ESKOM launched the “Electricity for All” campaign, where previously white-oriented electricity resources were to be expanded to the whole of South Africa, with 260 projects planned by 1992. Ian McRae had headed the plan to expand electricity into townships, particularly regarding the rolling out of prepaid electricity. McRae had held interviews with churches and township residents to seek amicable and long-term solutions to electrification. The 1994 National Electrification Programme and the 2001 integrated National Electrification Programme aided the expansion of “Electricity for All”. [61] Between 1994 and 1999, 80% of city dwellers and 46% of rural households had access to electricity (albeit through prepaid meters). Between 1991 and 2014, 4,3 million households were electrified with 2,8 million households electrified between 1991 and 2001. [62]

After Apartheid’s isolation, ESKOM began to expand into Africa to generate revenues. ESKOM reintegrated the Cahora Bassa project in Mozambique and developed capacities in West Africa through the “West African Power Corridor Project”. Other projects included exporting electricity to Namibia and hydroelectric power from the Congo River which were led by a subgroup of ESKOM called ESKOM Enterprises. [63]

ESKOM had prepared for the transition to democracy “well before the formation of the first democratic government”; black workers were employed and they comprised 60% of the total workforce in 1993 and over 50% of technical positions were occupied by black workers in 1997. [64] The mechanisms of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), the Employment Equity Act (EEA) and the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act (PPPFA) were implemented. The BEE Commission “emphasised strong intervention from government to grow black capitalism and eliminate the marginalisation of black citizens”. [65]

The Energy White Paper of 1998 signalled a new direction for energy policy. It aimed at promoting a new model of development in the energy sector. Many ANC members, who were based in an energy research unit at the University of Cape Town were trying to find solutions to South Africa’s energy problems based on “sustainable development”, including economic efficiency, social equity and environmental sustainability. [66]

The 1998 White Paper on Energy was drafted (and not implemented), but even in the draft, very little public participation occurred. This was symbolised by “top-down decision-making”. Most importantly, there was no policy discussion or initiation of a national nuclear strategy. [67] The ANC government failed to adopt a proper nuclear energy strategy. While they ended the relationship between nuclear and military weapons, they did not replace this with a nuclear energy strategy.

The new policy structure of ESKOM emanating from the 1998 Energy Policy suggested that ESKOM be unbundled, independent power provision be adopted and ESKOM eventually privatised. This was met with sharp reactions from the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP). The ANC government avoided the privatisation of ESKOM and instead opted for it to be state-owned and compete in the free market. Political differences in the Department of Minerals and Energy pushed it past the moment of the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) and this meant it wasn’t implemented. [68]

Jaglin and Dubresson suggest that ESKOM gradually became “deinstitutionalised”, being both subject to the common law and having a new management system. ESKOM became an “instrument of state power” which was stripped of the freedom and action available when “at an arms-length from the state”. [69] Additionally, after the 2001 ESKOM Conversion Act, it was “weakened” and stripped of its prerogatives of autonomy and cheap electricity, but large coal-fired power stations were retained. [70] Engineers’ power was greatly reduced, managers were appointed by cronyism structures and “political entryism” was applied. [71]

As mentioned before, Fine and Rustomjee argue that that the minerals-energy complex was the dominant force in South Africa’s economy; in 1996, they argued that over 90% of electricity was generated from coal and 21,6% of this was contained in the coal and gold mining sectors. [72] Coal has maintained its dominance in the post-Apartheid energy landscape. [73] The minerals-energy complex has, until today, been relatively unchallenged as ANC leaders have taken hold of it. [74]

Despite changes in structure and governance, in 2001, ESCOM was awarded global Power Company of the Year. It was providing massive amounts of electricity; in 2003, South Africa had almost double the electricity consumption per capita than the global average. [75] What followed is a maelstrom of poor decisions, poor maintenance and corruption. This will be chronicled in Part 2 of ESKOM’s history.

This article set out trying to find some lessons and reflections for the future from the past of ESKOM. There are a number of these which seem particularly pertinent. Firstly, the privatisation of ESKOM is an ambiguous process. In the 1920s and the late 1940s, the government initiated processes to take over electricity production both to keep electricity prices down and encourage economies of scale. Where privatisation or corporatisation seems valuable is in maintaining “an arms-length” from the state. Throughout its history, this enabled ESKOM to be independent of political influence to a certain degree. The reversal of this in the early 2000s by the ANC government seems a massive mistake and has led to patrimonialism and political appointments.

This leads to the second lesson/reflection. As Jaglin and Dubresson state, ESKOM had techno-political managers. Many of these managers were engineers and as engineers had the technical vision to achieve political ends. The ANC government has failed to use technical skills to address the country’s energy issues. Technical skills rather than an abundance of managerial skills thus would lead to innovation to deal with the country’s needs. This could be in the direction of spreading electricity to rural areas, enabling more township residents to access electricity, tightening payment systems and supplying more regular clean energy. There was in the past capacity within the ANC government, as shown in the drafting of the Energy White Paper in 1998, ESKOM’s expansion into Africa and the redistribution of electricity to millions of black South Africans, to embody a more developmental vision, but this has since dissipated dramatically.

A third reflection is that during times of energy crisis, the key is investment. When South Africa experienced load shedding between 1948 and 1953, they embarked on investment in a large fleet of coal-fired power stations and other energy sources from hydroelectric power and even nuclear. It is true that the ANC commissioned Kusile and Medupi coal-fired power stations after the bouts of load shedding in 2014. Yet these investments lead to a fourth reflection.

The building of large, coal-fired power stations certainly appeased the various stakeholders who were part of the minerals-energy complex. Yet during the 1980s, the Apartheid government planned large new coal-fired power stations but then demand dropped as gold mining struggled. These large coal-fired power stations were difficult to maintain and had less flexible generation. New energy sources from hydroelectric, solar, wind and nuclear need to be added into the mix on differing scales.

The final point is the impending global environmental crisis. It seems that ESKOM is tangled in a web of past decisions which greatly impede their present. Yet the environmental crisis is an opportunity for ESKOM to break out of the minerals-energy complex and invest in new forms of electricity. This new investment would lead to the stabilisation of the national grid and grow technologies which pollute less than coal.

[1] Sylvy Jaglin and Alain Dubresson. Eskom: Electricity and Technopolitics in South Africa (Cape Town: UCT Press, 2016), p.9.

[3] Leonard Gentle, “Escom to Eskom: From racial Keynesian capitalism to neo-liberalism (1910–1994)” in David MacDonald (eds), Electric Capitalism: Recolonising Africa on the Power Grid (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2009), p.52.

[4] Richard Worthington, “Cheap at Half the Cost: Coal and Electricity in South Africa” in David MacDonald (eds), Electric Capitalism: Recolonising Africa on the Power Grid (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2009), p.119.

[5] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.53; Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.9

[6] Ben Fine and Zavareh Rustomjee. The Political Economy of South Africa: From Minerals Energy Complex to Industrialisation (London: Westview Press, 1996), p.5 and p.71.

[7] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.55.

[8] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.10.

[9] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, pp.53-54.

[10] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.11.

[11] Ibid, p.10.

[12] Renfrew Christie in Bill Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa: A Developmental History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), p.32.

[13] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, pp.57-58.

[14] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p. 56; Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, pp.11-12. The funding for ESCOM and the newly formed, government-led Iron and Steel Corporation of South Africa (ISCOR), formed in 1924, would come from gold mining tax.

[15] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, p.33.

[16] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.12 and Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, p.32.

[17] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, p.32.

[18] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, pp.15-16.

[19] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, pp.56-58 and Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, pp.11-13.

[20] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.12.

[21] Fine and Rustomjee, The Political Economy of South Africa, pp.133-134.

[22] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, pp.59-60.

[23] Ibid, p.58.

[24] Fine and Rustomjee, The Political Economy of South Africa, p.137.

[25] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.58.

[26] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, pp.67-72.

[27] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, p.70 and p.83; Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, pp.13-14; Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, pp.58-59.

[28] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, pp.67-68, Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, pp.14-15.

[29] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.60.

[30] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, p.92 and Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.14.

[31] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.16.

[32] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, p.177.

[33] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.17 and Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.62.

[34] Fine and Rustomjee, The Political Economy of South Africa, p.161 and p.195.

[35] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, p.127.

[36] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, p.83 and Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.62.

[37] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.62.

[38] Ibid, p.62.

[39] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, pp.177-178 and Fine and Rustomjee, The Political Economy of South Africa, p.169.

[40] Worthington, “Cheap at Half the Cost”, p.120.

[41] Ibid, p.120.

[42] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, p.172.

[43] David Fig, “A Price Too High: Nuclear Energy in South Africa” in David MacDonald (eds), Electric Capitalism: Recolonising Africa on the Power Grid (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2009), p.185.

[44] David Fig, “A Price Too High”, p.186.

[45] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, pp.173-176.

[46] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.60.

[47] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, pp.18-19.

[48] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.64.

[49] Freund, Twentieth Century South Africa, p.180 and p.193.

[50] Ibid, p.210.

[51] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.19. and Fine and Rustomjee, The Political Economy of South Africa p.199.

[52] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.19-20.

[53] Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.64.

[54] Ibid, p.50.

[55] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.20 and Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.64.

[56] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.21.

[57] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.21 and Gentle, “Escom to Eskom”, p.65.

[58] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.22.

[59] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.23.

[60] Ibid, pp.23-25.

[61] Ibid, p.56.

[62] Ibid, pp.57-61.

[63] Ibid, pp.104-105. Worthington, “Cheap at Half the Cost”, p.122.

[64] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.22.

[65] Ibid, p.125.

[66] Ibid, pp.30-33.

[67] Fig, “A Price Too High”, p.190.

[68] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, pp.33-35.

[69] Ibid, p.29-30.

[70] Ibid, pp.26-29.

[71] Ibid, p.30-33.

[72] Fine and Rustomjee, The Political Economy of South Africa, p.80.

[73] Worthington, “Cheap at Half the Cost”, p.144.

[74] Jaglin and Dubresson, Eskom, p.148.

[75] Richard Worthington, “Cheap at Half the Cost”, p.125.

- Fig, David. “A Price Too High: Nuclear Energy in South Africa” in David MacDonald (eds), Electric Capitalism: Recolonising Africa on the Power Grid (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2009).

- Fine, Ben and Zavareh Rustomjee. The Political Economy of South Africa: From Minerals Energy Complex to Industrialisation (London: Westview Press, 1996).

- Freund, Bill. Twentieth Century South Africa: A Developmental History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

- Gentle, Leonard. “Escom to Eskom: From racial Keynesian capitalism to neo-liberalism (1910–1994)” in David MacDonald (eds), Electric Capitalism: Recolonising Africa on the Power Grid (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2009).

- Jaglin, Sylvy and Alain Dubresson. Eskom: Electricity and Technopolitics in South Africa (Cape Town: UCT Press, 2016).

- MacDonald, David. (eds), Electric Capitalism: Recolonising Africa on the Power Grid (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2009)

- Worthington, Richard. “Cheap at Half the Cost: Coal and Electricity in South Africa” in David MacDonald (eds), Electric Capitalism: Recolonising Africa on the Power Grid (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2009).

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

- No results found

History of South Africa’s electricity sector

The history of the electricity sector in South Africa is characterised by very high growth in electricity intensity over the long term, as illustrated in Figure 30. There has also been a high level of volatility in the supply of electricity. South Africa’s resource-based economic growth trajectory has played an important role in the electricity-intensive nature of the economy. Indeed, the discovery of diamonds (1867) and gold (1886) were catalysts for the introduction of electricity on a commercial scale. Gold mining has been a major driver of electricity consumption, particularly as mines became deeper, increasing the amount of electricity utilised for the same quantity of output.

The generation of electricity increased signifi cantly in the 1932—1940 period (growing at an annual average rate of 14%, against a 7.6% growth in GDP), largely because of an increase in the price of gold, alongside the following developments:

• more households started using electricity;

• mechanisation continued — Iscor and the African Metals Corporation (AMCOR) commenced with metals and ferroalloys production respectively;

• mining activity expanded, with mines becoming deeper;

• negotiations with mines to build a new plant (Klip) resulted in an 11.5% fall in the cost of electricity.

Between 1947 and 1973, the introduction of import controls, together with the discovery of further gold resources, led to a sharp rise in the demand for electricity. This was reinforced by the further expansion of electrifi ed rail transport in 1950. Consequently, supply constraints arose in 1951, despite the construction of additional power stations. The power crisis was resolved in 1960 when electricity supply capacity was doubled. The average annual rate of increase in electricity demand during the 1947—1973 period was 8%, against a GDP growth rate of 5%.

In the light of current controversies surrounding electricity price hikes, it is interesting to note that South Africa’s electricity price increases were exceptionally high during the 1974—1978 period: 16.5% in 1975; 30.3% in 1976; 48.2% in 1977; and 16.5% in 1978. During this period GDP increased at an average annual rate of only 1.7%, while the electricity sector grew at an average annual rate of 7%.

From 1980 to 1986, blackouts and brown-outs caused major protests, resulting in an electricity crisis. In response, more power

stations were built within a relatively short period of time, in order to meet the rising demand. Electricity prices increased further (by 12.7% in 1981; 22.9% in 1982; and 19.8% in 1983). Despite the turmoil caused by the global oil price crisis of 1986, the recovery of the steel industry in 1984 and the high growth in gold mining resulted in growing electricity demand. Thus although the average annual GDP growth was only 1.1%, the electricity sector grew at an annual average rate of 4.7% per annum during this period.

Ironically, in the 1987—2007 period, South Africa’s electricity supply capacity substantially exceeded the demand for electricity. Consequently, between 1990 and 2000, the real price of electricity decreased. Following the fi rst democratic elections in 1994, major changes occurred in the South African electricity environment, including:

• the establishment of the Atomic Energy Corporation’s plant in Pelindaba (1995);

• the establishment of a National Electricity Regulator in 1995 (now NERSA); and

• the publication of the White Paper on Energy Policy (1998).

The exceptionally cold winter of 1996, alongside the establishment of the new Hillside aluminium smelter, Columbus Steel and other heavy mineral plants, resulted in a very high demand for electricity. In the same period, the Saldanha Steel plant reached full capacity.

Further energy sector reforms and policy developments included the following:

• in 2002 Eskom was transformed from a statutory body to a public company — Eskom Holdings Limited, in terms of the White Paper on Energy Policy Act (Government of RSA 2001a);

Figure 30: Index of electricity intensity in South Africa, 1921—2011

Source: Eskom (2011)

South African electricity sales/GDP at market prices — 2005=100

0.160 0.140 0.120 0.100 0.080 0.060 0.040 0.020 0.000 1921 1931 1941 1951 1961 1971 1981 1991 2001 2011 kW h/R

• in 2003 the White Paper on Renewable Energy (Department of Minerals and Energy 2003) was released;

• in 2004 the National Energy Regulator Act (Government of RSA 2004) was promulgated and the importation of natural gas from Mozambique to South Africa commenced;

• in 2005, NERSA was established as a successor to the energy regulator created in 1995.

In January 2008, South Africa experienced another electricity supply crisis, evidenced by widespread load shedding. At the end of the same year, the global fi nancial crisis emerged, driving the South African economy into recession. Consequently, electricity demand contracted by -2.2% and -2.7% in 2008 and 2009 respectively. In 2009, measures were put in place to deal with the electricity crisis, including the reduction of supply to electricity intensive users such as mines and smelters.

In order to deal with the long-term challenges posed by the electricity sector, the South African Government promulgated an Integrated Resource Plan for Electricity 2010-2030 (IRP 2010) (Department of Energy 2010) in May 2011, following extensive modelling of the electricity sector and stakeholder consultations. The IRP 2010 was approved by Cabinet in 2011 as a long-term strategic plan to guide the expansion of electricity supply over the 2010-2030 period. To that end, it identifi es investments in the electricity sector that

are necessary to enable it to meet the anticipated demand for electricity in the most effi cient manner.

Notably, the level of electricity intensity started a decline from the early 2000s. This was due to the growth of economic sectors which are less electricity intensive, such as the fi nancial services sector, and was reinforced by:

• improvement in energy effi ciencies of existing facilities;

• new technologies using less energy per unit produced;

• downsizing electricity intensive products such as copper and plastic/fi bre;

• recovery and recycling of some materials/commodities.

Nevertheless, by international standards, energy intensity remains high.

Electricity sector demand and load profi les

- Overview of South Africa’s commercial ports In order to provide a more nuanced perspective of South Africa’s

- Operational issues

- Financing in the ports sector

- Finance for road infrastructure

- History of South Africa’s electricity sector (You are here)

- Challenges in the water sector

- Institutional issues

- Ensure reliable generation, distribution and transmission of electricity

- Ensure maintenance and strategic expansion of road and rail network, operational effi ciency,

- Actions needed to achieve each output

- To ensure the maintenance and strategic expansion of our road and rail network, and the operational effi ciency, capacity and competitiveness of our sea ports and rail

Related documents

- Alternatives to austerity and regressive tax policies

- Movement building

- Southern Africa

- Dismantling Corporate Power

- Energy democracy and climate justice

- About Amandla! Media

- Amandla Ulutsha

- Amandla! Archive

- AIDC Resource and Information Centre (RIC) Library

- Publications

- Systems Change not Climate Change – Podcast

- Solidarity Centre

- Amadiba Crisis Comittee

- Botshabelo Unemployment Movement

- PE Amandla Forum

- Progressive Youth Movement

- South African Green Revolutionary Council

- Partner News Archives

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ESKOM – 1923-2015

Sandra Van Niekerk | Why Eskom Is In a Mess and What to Do About It

In order to fully understand the problems facing Eskom and the electricity system today, it is important to understand the history of how electricity developed in South Africa, who was responsible and why it was developed; what changes were made and when, and in whose interests. Once we have this full picture, we can better understand what we need to do to transform the current system in order to meet basic social needs.

1.Beginnings of Escom

Escom (Electricity Supply Commission) was established in 1923 in terms of the Electricity Act (No 42 of 1922). Also established in terms of this Act was the Electricity Control Board (ECB) which controlled and licenced the electricity supply and set tariffs.

Before 1923, electricity in South Africa was generated by a large number of different bodies, including 40 municipalities and 18 private companies. The two largest companies were the Rand Mines Power Supply Company and the Victoria Falls and Transvaal Power Company. But industry, mining and transport increasingly needed a reliable and cheap source of electricity as they grew and consolidated their position in the economy. The railways in particular were looking for abundant, reliable and cheap electricity to power their electric-powered trains, and their need was a strong impetus for Escom’s formation.

So Escom’s main purpose was to ensure delivery of cheap electricity to the railways and mines. But its mandate was framed in terms of providing a public service, and supplying electricity ‘in the public interest’ (Gentle 2009: 50). Escom played a central role in driving the development of the South African capitalist economy, and made possible cheap power for the growing mining, transport and manufacturing sectors. White South Africans also benefitted from this cheap electricity, receiving a good quality, cheap service to residential areas during the apartheid years.

In these early years, there was no requirement for Escom to operate at a profit, and it was exempt from paying taxes, but there was a strong emphasis on it operating independently from government and parliament. It was required to finance its operational costs out of revenue generated by the sale of electricity. It also used this revenue to pay off the loans it raised to finance capital expenditure. Escom was only able to access money from the national fiscus through an Act of Parliament.

As Escom grew, it gradually took over the private, independent power stations until, by 1948, it was a vertically integrated state utility, responsible for generation, transmission and distribution (although with local government continuing to play a key role in relation to distribution ). As a producer of cheap electricity for mining, industry and the railways, it became a key driver of the Minerals-Energy Complex (MEC) and large-scale private monopoly capital.

2.From Escom to Eskom

In the 1970s, Escom was borrowing more on the foreign market to fund its new build programme, but the size of this programme was making it increasingly difficult to fund the loans through tariff increases. As a result, the government passed a new law that allowed Escom to set up a Capital Development Fund. Escom was able to retain its earnings and put any excess into this fund. As this fund built up, Escom was able to draw on it to fund its ongoing new build programme.

Developments in the international economy, such as the global energy crisis in the early 1970s, started putting pressure on Escom’s costs, with the result that the price of electricity started going up in the mid-1970s. At the same time, there was increasing pressure on the supply of electricity, so Escom continued with its massive build programme. There was another motivation as well – at a time of international sanctions against apartheid South Africa, the government was determined to build South Africa’s self-sufficiency, including energy self-sufficiency. [1] The new build programme included Koeberg (South Africa’s only nuclear plant), as well as new coal-fired plants.

In order to pay for this programme, electricity tariffs again went up in the early 1980s. These price increases hit the South African economy hard at a time when it was already under increasing strain. There was a great deal of public anger towards Escom and the increases.

In 1984 the government was forced to set up the de Villiers Commission to investigate the situation at Escom. This was done to appease the public and to review Escom’s operating and planning processes. As a result of the de Villiers Commission recommendations, and to mark a new stage in the development of the state utility, Escom underwent a name change, and from 1987 was known as Eskom. This was among a raft of changes proposed by the Commission, which were consolidated in two pieces of legislation – amendments to the 1922 Act (Electricity Amendment Act of 1985) and the Eskom Act of 1987.

Apart from the name change, other changes brought about by the de Villiers Commission included:

- The scrapping of the electricity control board and its replacement by the Electricity Council. The council would be in control of policy and planning. For the first time this included private capital being directly involved in decision making processes in the state.

- The Electricity Council appointing a management board – effectively setting up a two-tier structure of governance.

- Eskom started to operate on a commercial basis and no longer being governed by the principle of operating as a not-for-profit entity.

- Stopping the capital development fund (this had happened in 1985).

- Setting a national tariff, which meant municipalities would no longer set their own tariffs.

- Eskom falling under the Ministry of Public Enterprises, rather than the Ministry of Minerals and Energy Affairs. Overall energy policy, however, was still determined by the Ministry of Minerals and Energy Affairs.

- Separating out non-regulated activities of Eskom and consolidating them into Eskom Enterprises.

Eskom Enterprises, acting like a private company, took on electricity contracts in other parts of Africa, as well as in the telecommunications and information technology sector. But these did not go well, and by 2004 Eskom had retreated back into a focus on domestic electricity “in line with the government’s greater emphasis on using state-owned enterprises for development”. (Greenberg 2009: 73)

Another important development was that the different components of Eskom – generation, transmission and distribution – began to pay tariffs to each other. This served to bring market relations into the electricity sector. (Greenberg 74)

The process of corporatising Eskom started with the shift from Escom to Eskom, and it culminated in the Eskom Conversion Act No 13 of 2001, which made Eskom subject to the Companies Act (no 61 of 1973). While Escom was charged with operating “in the public interest”, the 1987 Act spoke about Eskom needing “to provide the system by which the electricity needs of the consumer may be satisfied in the most cost-effective manner, subject to resource constraints and the national interest.” (Gentle 2009: 50).Thus the 1987 shift from Escom to Eskom represents a key moment in the shift from a public entity to a commercial entity operating along market-based lines. Gentle argues that the change in name “marks a radical rupture in the nature of South African capitalism and its mode of accumulation….. [It was] a change from a form of Keynesian racial capitalism, in which the state secured the conditions necessary for accumulation for the capitalist class as a whole based on cheap black labour power, cheap energy and regulated capitals, to a neoliberal state attempting to open up new arenas for commodification.” [2]

3.Ongoing corporatisation of Eskom after 1994

The corporatisation process continued and was deepened in the 1990s after the ending of apartheid and the coming to power of the ANC government in 1994 . Growth, employment and redistribution (GEAR), the macroeconomic policy that the government adopted in 1996, consolidated the neoliberal orientation of the government, which impacted heavily on the future direction of Eskom.

In 1994 Eskom had a “spare” capacity of 31%, and electricity in South Africa was among the cheapest in the world. The cheap electricity was made possible because Eskom was no longer involved in a new build programme, and because it was accessing cheap coal through long-term supply contracts.

Big multinationals took advantage of the cheap electricity to negotiate even cheaper contracts with Eskom. In particular, aluminium and ferrochrome smelter companies, like BHP Billiton, entered into special pricing agreements, called Embedded Derivative Contracts , that guaranteed particularly cheap electricity for periods of up to 25 years. The terms of these contracts were kept secret for many years by Eskom. It was eventually forced to reveal some of the details after an Access to Information court case ruled against it. While some of these contracts actually stretched back to the apartheid years, some of them had only been concluded in 2003.

In 1995 the Electricity Control Board (ECB) was replaced by the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (NERSA). NERSA had regulatory jurisdiction over Eskom and local authorities: it regulated market access by licencing producers, transmitters, distributors and sellers of electricity, and it approved all tariffs.

The Electricity White Paper was released in 1998. It spoke about the unbundling of Eskom, which was one of the state utilities that the government planned to privatise. It envisaged 30% of electricity generation coming from the private sector. Unbundling was seen as a necessary part of the plan since it would break Eskom up into different entities, which would then face competition from other market operators.

The plan for a restructured electricity sector called for the establishment of six Regional Electricity Distributors (REDs) which would consolidate the distribution function previously carried out by a combination of Eskom and municipalities. The REDs would fall under a new entity to be established – Eskom Holdings. Also falling under Eskom Holdings would be a separate Transmission Utility, which would be initially state owned but possibly later privatised; and system operator.

The Eskom Amendment Act of 1998 started the formal, legal process of corporatising Eskom in the lead up to full unbundling and privatisation. In terms of this legislation, the State became the sole owner of Eskom’s equity, its tax-exempt status was repealed, and the Minister of Public Enterprises was mandated to incorporate it as a limited liability company with share capital.

The process of corporatisation was completed in 2001 with the passing of the Eskom Conversion Act (no 13 of 2001). In terms of this Act, Eskom was converted, in 2002, from a statutory body into a company under the Companies Act (no 61) of 1973, with the ultimate goal of listing on the stock exchange. As a company, Eskom was required to pay taxes and dividends to the state. The nature of the Eskom board also shifted. It was no longer a two-tier structure, with a management board and an Electricity Council. It became a single board of directors which consisted mostly of representatives of big business, a few academics and one Department of Public Enterprises (DPE) representative (Greenberg p77). The role of stakeholders in the Electricity Council was done away with.

The practical implication of this corporatisation was the ringfencing of the three units – generation, transmission and distribution. The aim was for the private sector to be generating 30% of electricity by 2004, and for Eskom to strengthen its financial viability by taking on contracts in other countries in Africa through Eskom Enterprises.

Eventually the plans to set up the REDs and to fully privatise Eskom were shelved. This was partly because of stiff opposition to privatisation from the unions, and partly because of a waning international appetite for privatisation. The South African Local Government Association (SALGA), which represented municipalities across the country, also strongly resisted the moves to set up the REDs. One of their major concerns with the proposal was the loss of income it represented – municipalities are heavily dependent on the sale of electricity as a source of income.

The process of reforms had started in 1987, and had gone through a number of iterations, not least because of the first democratic elections bringing the ANC to power. The end result was a corporatised Eskom, with plans to increase competition in the generation sector through bringing in Independent Power Producers (IPPs).

Share this article:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- Announcing “Eskom Transformed”: The Case for a Big Eskom in the Age of Austerity

- What is the ‘Just Transition?’

- Why Should We Oppose Unbundling? (Part 1)

- Financing a Socially-Owned Transformed Eskom

2 Comments on “ A BRIEF HISTORY OF ESKOM – 1923-2015 ”

Informative, interesting and required reading for adding to a national debate on the socio-political crisis of the country.

Sandra, thanks for great work and making it freely avaiiable. Value the generosity

1 Pings/Trackbacks for "A BRIEF HISTORY OF ESKOM – 1923-2015"

[…] are certainly sometimes commercially driven, such as Eskom following its 2001 reorganisation and corporatisation. But vertically integrated utilities can also produce and distribute […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Resource Centers

- Poverty on the rise in South Africa!

- Press Conference | CryX MTBPS 2021 action plan!

- What will it take to fix our municipalities?

- Why We Must Transform Eskom

- Anglo-America in South Africa: a History of Abuses and Violations.

- Voices of the Streets – Episode 7: Struggle in the City of Cape Town (Part 2)

© 2024 AIDC. All Rights Reserved. Sitemap

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

South Africa's Electricity Crisis: How did we get here? And how do we put things right?

Related Papers

Catrina Godinho

Martin Rodriguez Pardina , Pierre Audinet

Sharon Beder

Policy Research Working Papers

Zeljko Bogetic

Jacobus Holtzhausen

Ben Sebitosi

Utilities Policy

Grové Steyn

Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy

Julie A Cohn

This paper traces historical trends and experiences with the U.S. electrical grid to help frame choices as more renewables are brought into the system.

African Communist

Reneva Fourie

South Africa has been experiencing periodic electricity outages since 2006. The reasons attributed to these outages ranged from unanticipated fires damaging transmission cables, to bolts damaging electricity generation plants. In January

Distributed Generation and its Implications for the Utility Industry

Jenny Riesz , Magnus Hindsberger

29 The Energy Politics of South Africa

Lucy Baker, University of Sussex

Jesse Burton, University of Cape Town

Hilton Trollip, University of Cape Town

- Published: 08 June 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter explores key processes within South Africa’s electricity sector that evolved under the presidency of Jacob Zuma from his inauguration in 2009 until he was forced out of office in early 2018. These processes include the introduction of a national planning process for electricity; the implementation of a procurement program for privately generated renewable electricity; and a highly controversial nuclear procurement program, since scrapped following Zuma’s departure. The chapter’s exploration takes place within the context of a decade of “state capture” and corruption. Drawing from a wide range of literature on South Africa’s energy policy, it advances perspectives of the “minerals-energy complex” (Fine and Rustomjee 1996), which has been a dominant framework for the analysis of the country’s political economy and its electricity sector. The chapter concludes with a research agenda that brings together the literature on sociotechnical transitions with that of analyses of the nature of the state.

This chapter has been written in the aftermath of nearly a decade of state capture and a national discourse on corruption that emerged at the end of 2016. While the extent of state capture is still coming to light (Joffe 2018 ), the country’s electricity sector has been at its center. Within this context, we focus on key processes within the electricity sector and the state-owned utility Eskom that evolved under the presidency of Jacob Zuma from his inauguration in 2009 until he was forced out of office in February 2018. Zuma’s presidency was riddled with allegations of corruption and graft that include but have gone far beyond the electricity sector. As we discuss here, the challenges associated with the design and implementation of national policies on energy have been intertwined with intensifying national political conflict and broader political battles within the ruling national party, the African National Congress (ANC), and the state. Since Zuma was ousted from power, a number of key sticking points in the electricity sector have been reversed by current (2019) president Cyril Ramaphosa. Yet while Zuma is facing charges that include corruption, racketeering, fraud, and tax evasion—charges that were dropped prior to his becoming president in 2009—many of Zuma’s cronies remain in power (Momoniat 2018 ). The impact this will continue to have on national politics and the politics of electricity will require further political analysis over the coming years.

Eskom, the state-owned, vertically integrated monopoly utility, generates 85 percent of electricity from coal. Privately owned, utility-scale renewable energy makes a small contribution to electricity generation of approximately 5 percent, along with other independent power producers (IPPs), but is dependent on Eskom as the single buyer and transmission operator to purchase this electricity. Nuclear power accounts for 6 percent of electricity production, gas/diesel for 2 percent, and the remainder comes from imported hydro (Eskom 2017 ) (see Figure 29.1 ).

South Africa’s installed capacity, 2018.

South Africa’s energy sector is dominated by coal, which accounts for approximately 75 percent of primary energy. Of total national coal production of approximately 250 million metric tons per annum, 41 percent is converted into electricity and 15 percent into liquid fuels, and 8 percent is used directly by industry (Hartley et al, 2019 ); the remainder is exported, primarily to the Pacific market.

An electricity supply crisis that gripped the country over the period 2007–2015 has been succeeded by stagnant demand (Steyn, Burton, and Steenkamp 2017 ). This situation is partly a result of increasing electricity prices; the average standard tariff increased from R0.18 ($0.13) 1 in 2006/2007 to R0.82 ($0.59) in 2016/2017, an increase of 355 percent, while inflation increased by 74 percent over the same period and is projected to continue rising (Eskom 2019a ). At the same time there has been a decline in economic growth, from around 4 percent between 2000 and 2010 to 2 percent between 2010 and 2015, and to 1 percent or lower since 2016 (IMF 2019 ). This has been accompanied by a parallel reduction in demand from the country’s energy-intensive mineral-extraction industries, whose industrial sales shrank by 13 percent between 2013/2014 and 2017/2018 (Eskom 2018 ). While the commissioning of some units of the country’s largest coal-fired power stations, Medupi and Kusile, currently still under construction, has somewhat alleviated the supply shortages, chronic underfunding for the maintenance of coal-storage and coal-fired infrastructure remains a risk. With 30 percent of Eskom’s plant out of service due to planned and unplanned outages (Eskom 2018 ), this led to further load shedding in late 2018 and early 2019, despite a large capacity margin. Indeed, in 2018 available dispatch generation capacity stood at 32GW out of 47GW net maximum capacity (Eskom 2019b ).

This chapter develops theoretical perspectives on the political economy of South Africa’s electricity sector that have analyzed its embeddedness within the context of the country’s “minerals-energy complex” (MEC) (Fine and Rustomjee 1996 ). We account for shifts that have taken place since 2009, focusing in particular on the introduction of a national planning process for electricity; the implementation of a procurement program for privately generated electricity from renewable energy; and a highly controversial nuclear procurement program, since scrapped under President Ramaphosa (Baker et al. 2015 ; DoE 2018 ; Eberhard, Kolker, and Leighland, 2014 ).

This chapter advances our combined long-standing and in-depth expertise and insights into South Africa’s electricity sector and political economy (Baker and Burton 2018 ; Baker, Newell, and Phillips 2014 ; Baker et al. 2015 ). In addition to an academic literature review, our theoretical development is informed by an extensive content analysis of gray literature pertaining to energy and related sectors, including government documents, national policies, parliamentary transcriptions, and industry reports, as well as a systematic consultation of relevant media, including sources such as Business Day , Engineering News , and ESI Africa .

In this chapter we first explain the nature of South Africa’s MEC as a descriptive and theoretical starting point for understanding the historical and contemporary development of the labor-intensive, energy-intensive, and carbon-intensive economy in which the electricity sector is embedded. We next examine the crises currently being experienced in the electricity sector and the way in which it has been involved in and affected by processes of state capture. This examination is followed by a discussion of the political and economic challenges to key processes in the electricity sector in recent years. Finally, we suggest a future research agenda that focuses on alternative framings for the technological and political nature of South Africa, including concepts of a political economy of electricity and the role of the state in energy transitions.

National Context: The Minerals-Energy Complex and Beyond

The political economy of South Africa’s electricity sector has been characterized by the country’s MEC (Fine and Rustomjee 1996 ), a concept coined at the end of apartheid that has continued to be used as the dominant framework for a critical analysis of South Africa’s political economy, including its energy sector and industrial dynamics. The MEC has long provided a descriptive starting point for understanding the nature of South Africa’s capital-intensive, energy-intensive, and carbon-intensive economy. It also provides a critical analytical framework for understanding key trends in the country’s economic and political history as well as the structural causes of socioeconomic inequality and environmental injustice, such as the effects of continued coal development on local communities (Hallowes 2014 ; Peek and Taylor 2014 ).

The MEC refers to the country’s unique and evolving system of accumulation, which historically was based on cheap coal for generating cheap electricity. Coupled with cheap labor, this combination provided input into export-oriented mining and minerals processing and beneficiation 2 (Fine and Rustomjee 1996 ). Historically, the MEC has been characterized by an evolving relationship and set of linkages between highly concentrated ownership structures of the state, state-owned enterprises, corporate capital, and a powerful financial system (Ashman and Fine 2013 ). Indeed, Marquard ( 2006 , 71) described the South African economy as an associated “industrial policy complex,” “consisting of a number of overlapping policy networks … and coordinated by what can be termed an ‘industrial policy elite’ … with close connections to the political elite.” The inter-linkages have been characterized by a particular historical dynamic of “conflict and coordination” (Baker et al. 2015 , 7).

The MEC has offered an analytical framework to address the socioeconomic and political legacy of apartheid and the nature of state and capital relations in contemporary South Africa (Padayachee 2010 , 2). The MEC has been understood as an “architecture” (Freund 2010 ) that encompasses critical links and networks of power between the financial sector, government, the private sector, and state-owned enterprises, which are commercial corporations wholly or majority owned by the government, such as the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) and Eskom. Various studies have applied an MEC framing to the electricity sector (Büscher 2009 ; Hallowes and Munnik 2007 ; McDonald 2009 ). More recent analyses have extended this framing to the country’s new renewable energy industry and in so doing have drawn from the sociotechnical transitions literature to incorporate a perspective that is more aware of the nature of technological development, infrastructure, and innovation than the otherwise political and socioeconomic analyses (Baker 2015 , 2016 ; Baker, Newell, and Phillips 2014 ).

A number of changes have been made to the MEC framework since its earlier use. First, twenty-five years after the transition to democracy, the assumed homogeneity of the MEC and the formal and informal institutions underpinning it have been subject to economic, political, and technical change, due to a combination of endogenous and exogenous factors. Such changes include shifts in the contribution of different sectors to gross domestic product (GDP), including the increased role of finance and tertiary sectors in the country’s economy (Ashman and Fine 2013 ). For instance, South Africa’s financial and business services now account for 24 percent of the county’s GDP (Bhorat, Cassim, and Hirsch 2014 ) and form the country’s single largest economic sector in terms of contribution to GDP, leading to what Ashman and Fine ( 2013 , 146) describe as a “financialised MEC.” At the same time, declining prices in international commodity markets have reduced the international competitiveness of many of South Africa’s beneficiated exports. While elements of the relationship between the state and energy-intensive businesses have remained intact, emerging changes have arisen from parallel economic, technological, and ideological pressures.

A second change is the formation of a new black economic and political elite following socioeconomic redistribution policies introduced after the end of apartheid under black economic empowerment (BEE) policies and legislation, 3 and more recently the country’s mining charter and minerals legislation. In the energy sector, this new elite has played an important role in diversifying ownership of the country’s coal-mining houses, which were previously owned by a small number of large international conglomerates (such as Anglo American and BHP-Billiton). Eskom now purchases almost 40 percent of its coal from smaller, BEE-owned mines, at much higher delivered costs (Burton, Caetano and McCall et al. 2018 ).

Further shifts in the coal market have included changes in international demand for the country’s coal (from Europe to India), depletion of the country’s cheaper coal resources as a result of increased demand from China and India, and the end of long-term coal contracts between tied coal mines and Eskom. Consequently, the era of cheap coal in South Africa has come to an end (Burton and Winkler 2014 ; Spencer et al. 2017 ). This, in addition to international greenhouse gas emissions agreements, will in the long term require the structural phaseout of coal in South Africa.

A third change in the MEC is the increasing dispersal and fragmentation of previously entrenched relationships between and within different political, state, industrial, and financial institutions, which spells a fundamental reshaping of South Africa’s political economy. As McDonald ( 2009 ) has argued, the relationship between “big state and big capital is changing.” This change has been accompanied by growing factional battles within the ruling ANC, as well as political battles in other key parts of the polity. As a post-colonial liberation movement, the ANC accommodated organized labor, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), and the South African Communist Party (SACP), with which it forms the Tripartite Alliance. This “broad church” (Gumede 2007 , 305) has always brought with it ideological tensions. Not least, organized labor has fallen into internal disarray, with COSATU splitting apart and giving rise to a new union federation that is no longer aligned with the ANC, and there is growing competition and fragmentation between unions competing within sectors (Bezuidenhout and Tshoaedi 2017 ).

The means by which Zuma came to power and the dynamic of his presidency highlighted factional divisions within the party that were often more about networks of patronage than about questions of policy (Butler and Southall 2015 ). Moreover, while the ANC has demonstrated its willingness to put the party before the constitution and the public interest, it is clear that contemporary South Africa is no longer about the one-party state, but is experiencing an unraveling of long-standing political strongholds (Butler and Southall 2015 ).Understanding the dynamics of political factions and their interests and influence over policy decisions is a key area of further research.

An Electricity Sector in Crisis and the Role of State Capture

At the heart of South Africa’s MEC sits the state-owned monopoly utility Eskom, which has been integral to balancing the interests of the state and businesses for almost a century. South Africa’s relative international isolation under apartheid meant that the country avoided the global trend of electricity sector liberalization pushed by the World Bank and other multilateral and bilateral donors as part of structural adjustment programs during the 1980s and 1990s (Gratwick and Eberhard 2008 ). Therefore, Eskom has essentially retained its monopoly over electricity generation, transmission, and the majority of distribution despite various failed attempts to liberalize it over the years. While there are long-standing tensions within government and related institutions and a spectrum of ideological differences between those advocating state ownership of the electricity sector at one end and those for liberalization and market reform at the other, factions within Eskom and related interests have long resisted the introduction of IPPs and the creation of an independent systems operator for transmission that would undermine Eskom’s current monopoly control (Baker and Burton 2018 ). The long-running ideological battle over ownership has been overlaid with a crisis partly caused by techno-institutional shifts in the sector and partly by runaway costs of large coal-fired power plants still under construction, operating expenses, and coal supplies, which have in turn been exacerbated by corruption (Eberhard and Godinho 2017b ; Steyn, Burton, and Steenkamp 2017 ). National debates over whether or not to keep Eskom as a vertically integrated monopoly or under state ownership have continued under the new era of governance heralded by President Ramaphosa (National Treasury 2019 ; Moneyweb 2019 ).

Facing a financial and management crisis, Eskom has been at the center of national scandals on state capture and failures of corporate and financial management, as discussed later in the chapter (Bhorat et al. 2017 ; Public Protector 2016 ). A huge program for the construction of new electricity generation capacity, initiated in 2005, is now several years delayed, more than 200 percent over budget, and subject to its own corruption allegations (Mntongana 2018 ). As a result, the state is now heavily exposed to Eskom’s debt as a result of guarantees it has provided to the utility (National Treasury 2018 ), as are other institutions that also hold Eskom’s debt, such as the Public Investment Corporation (which manages the pensions of government employees). The utility’s sales base is in decline, and regulated tariffs are not rising in line with the applications Eskom has made to the country’s energy regulator, NERSA, for rate increases. On the brink of bankruptcy, the largest recipient of state guarantees and bailouts and loans from development finance institutions, and with a capital budget larger than that of any other state-owned entity, Eskom is simply too big to fail. Eskom’s financial failure would impose a fundamental threat to the South African economy. The utility’s bonds are no longer considered creditworthy by investors (Laing 2018 ), it faces insolvency, it ran at a loss in financial year 2018/2019, and it has received various state bailouts in recent years. In the context of these crises, in the next section we discuss three key processes: the politics of electricity planning, renewable energy procurement from independent power producers, and nuclear procurement.

Key Processes in the Electricity Sector

Under Zuma, state capture evolved into massive corruption by a predatory elite. The term “state capture” was first used for South Africa by the country’s former public protector. 4 who as part of a nationwide investigation was among the first to expose the systemic corruption within Eskom and other state-owned enterprises in a groundbreaking report published in November 2016 (Public Protector 2016 ).

In October 2017, based on the 2016 report, the parliament began an enquiry into the state capture of Eskom and other state-owned enterprises (Levy 2018 ). Beyond the public protector’s report, the sheer extent and nature of state capture has been described in detail in a growing body of evidence, including by journalists and academics (Bhorat et al. 2017 ; Merten 2018 ; Pauw 2017 ;). Such evidence clearly illustrates ANC-sanctioned corruption across the economy and government. In brief, it has involved the ransacking and infiltration of public finances and government departments, including the intelligence networks; tax collection authorities (the South African Revenue Service); the National Prosecuting Authority; and state-owned enterprises, not least Eskom, but also transport (Transnet), aviation (South African Airways), and defense (Denel). Brian Molefe, the then chief executive officer of Eskom, was heavily implicated in multiple corruption scandals in different sectors and involving different levels of government. A judicial commission of inquiry into allegations of state capture, corruption, and fraud in the public sector has been looking into the contracts between Eskom’s power stations and its coal suppliers, in particular the irregular sale of the Optimum coal mine by mining giant Glencore to a company co-owned by the infamous Gupta family 5 and former president Zuma’s son. The sale implicated the minister of mineral resources and the head of the electricity generation division at Eskom, among others (Eberhard and Godinho 2017b ). Formal corruption investigations have resulted in a strongly worded parliamentary report recommending criminal investigations (Parliament of South Africa 2018 ), and a Judicial Commission of Enquiry has been hearing evidence under oath since August 2018, much of it damning (Hoffman 2019 ; Swilling 2019 ; Turok 2018 ; Zondo Commission 2019 ). The extension of capture throughout the state and state-owned enterprises, which have been “repurposed” for the benefit of a narrow elite within the ANC, highlights that the politics of energy must be analyzed in light of the broader politics within South Africa. Yet thus far theoretical research remains limited.

The Politics of Electricity Planning