The Difference Between Fiction and Nonfiction

Matt Grant is a Brooklyn-based writer, reader, and pop culture enthusiast. In addition to BookRiot, he is a staff writer at LitHub, where he writes about book news. Matt's work has appeared in Longreads, The Brooklyn Rail, Tor.com, Huffpost, and more. You can follow him online at www.mattgrantwriter.com or on Twitter: @mattgrantwriter

View All posts by Matt Grant

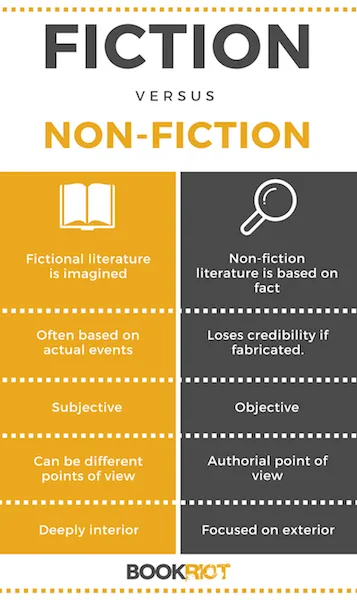

For writers and readers alike, it’s sometimes hard to tell the difference between fiction and nonfiction. In general, fiction refers to plot, settings, and characters created from the imagination, while nonfiction refers to factual stories focused on actual events and people. However, the difference between these two genres is sometimes blurred, as the two often intersect.

Before we go any further, it’s important to note that both fiction and nonfiction can be utilized in any medium (film, television, plays, etc.). Here, we’re focusing on the difference between fiction and nonfiction in literature in particular. Let’s look closer at each of these two categories and examine what sets them apart.

What Is Fiction?

When it comes to the differences between fiction and nonfiction, Joseph Salvatore, Associate Professor of Writing & Literature at The New School in New York City, says,

“I teach a course on the craft, theory, and practice of fiction writing, and in it, we discuss this topic all the time. Although all of the ideas and theories…are disputed and challenged by writers and critics alike (not only as to what fiction is but as to what it is in relation to other genres, e.g., creative nonfiction), I’d say there are some basic components of fiction.”

Fiction is fabricated and based on the author’s imagination. Short stories, novels, myths, legends, and fairy tales are all considered fiction. While settings, plot points, and characters in fiction are sometimes based on real-life events or people, writers use such things as jumping off points for their stories.

For instance, Stephen King sets many of his stories and novels in the fictional town of Derry, Maine. While Derry is not a real place, it is based on King’s actual hometown of Bangor . King has even created an entire topography for Derry that resembles the actual topography of Bangor.

Additionally, science fiction and fantasy books placed in imaginary worlds often take inspiration from the real world. A example of this is N.K. Jemisin’s The Broken Earth trilogy, in which she uses actual science and geological research to make her world believable.

Fiction often uses specific narrative techniques to heighten its impact. Salvatore says that some examples of these components are:

“The use of rich, evocative sensory detail; the different pacing tempos of dramatic and non-dramatic events; the juxtaposition of summarized narrative and dramatized scenes; the temporary delay and withholding of story information, to heighten suspense and complicate plot; the use of different points of view to narrate, including stark objective effacement and deep subjective interiority; and the stylized use of language to narrate events and render human consciousness.”

What Is Nonfiction?

Nonfiction, by contrast, is factual and reports on true events. Histories, biographies, journalism, and essays are all considered nonfiction. Usually, nonfiction has a higher standard to uphold than fiction. A few smatterings of fact in a work of fiction does not make it true, while a few fabrications in a nonfiction work can force that story to lose all credibility.

An example is when James Frey, author of A Million Little Pieces , was kicked out of Oprah’s Book Club in 2006 when it came to light that he had fabricated most of his memoir.

However, nonfiction often uses many of the techniques of fiction to make it more appealing. In Cold Blood is widely regarded as one of the best works of nonfiction to significantly blur the line between fiction and nonfiction, since Capote’s descriptions and detailing of events are so rich and evocative. However, this has led to questions about the veracity of his account.

“The so-called New Journalists, of Thompson’s and Wolfe’s and Didion’s day, used the same techniques [as fiction writers],” Salvatore says. “And certainly the resurgence of the so-called true-crime documentaries, both on TV and radio, use similar techniques.”

This has given rise to a new trend called creative nonfiction, which uses the techniques of fiction to report on true events. In his article “ What Is Creative Nonfiction? ” Lee Gutkind, the creator of Creative Nonfiction magazine, says the term:

“Refers to the use of literary craft, the techniques fiction writers, playwrights, and poets employ to present nonfiction—factually accurate prose about real people and events—in a compelling, vivid, dramatic manner. The goal is to make nonfiction stories read like fiction so that your readers are as enthralled by fact as they are by fantasy.”

Although it’s sometimes hard to tell the difference between fiction and nonfiction, especially in the hands of a skilled author, just remember this: If it reports the truth, it’s nonfiction. If it stretches the truth, it’s fiction.

You Might Also Like

Fiction vs. Nonfiction – What’s the Difference?

Home » Fiction vs. Nonfiction – What’s the Difference?

We see these words in libraries and bookstores, in magazines and online, but what do fiction and nonfiction really mean? What kinds of writing belong in each of these categories, and why?

You are not the first writer to ask these questions, and you will not be the last. Works of fiction and nonfiction can each be enthralling and valuable pieces of literature, but they are different in several important ways.

Continue reading to learn the differences between fiction and nonfiction , and how you can use these words in your own writing.

What is the Difference Between Fiction and Nonfiction?

In this post, I will compare fiction vs. nonfiction . I will use each of these words in at least one example sentence, so you can see them in context.

I will also show you a unique memory tool that will help you decide whether a piece of literature is fiction or nonfiction .

When to Use Fiction

In popular language, fiction is also used to describe anything that is not true.

Here are a few examples of the word fiction in a sentence,

- “I am penning a new work of fiction!” said the old-timey writer from a coffee shop in Paris.

- “The President’s allegations are pure fiction!” screamed the reporters.

- Many people did not know that The War of the Worlds was a work of fiction the first time they heard it.

- Some of the new technologies seem straight out of science fiction. – The Wall Street Journal

Novels are a classic example of fictional prose. If you enjoy reading novels, you are a fan of reading fiction.

When to Use Nonfiction

Here are a few more examples,

- “You will find the biography of Rutherford B. Hayes in the nonfiction section,” said the librarian.

- I would write a memoir, but the details of my life are so fantastical that people would not believe it is a work of nonfiction.

- The new self-help book climbed its way to the top of the nonfiction best sellers list.

- A biography of a book, rather than a person, is a relatively new wrinkle in nonfiction. – The Washington Post

If you enjoy reading biographies, memoirs, historical works, or books on current events, you are a fan of nonfiction works.

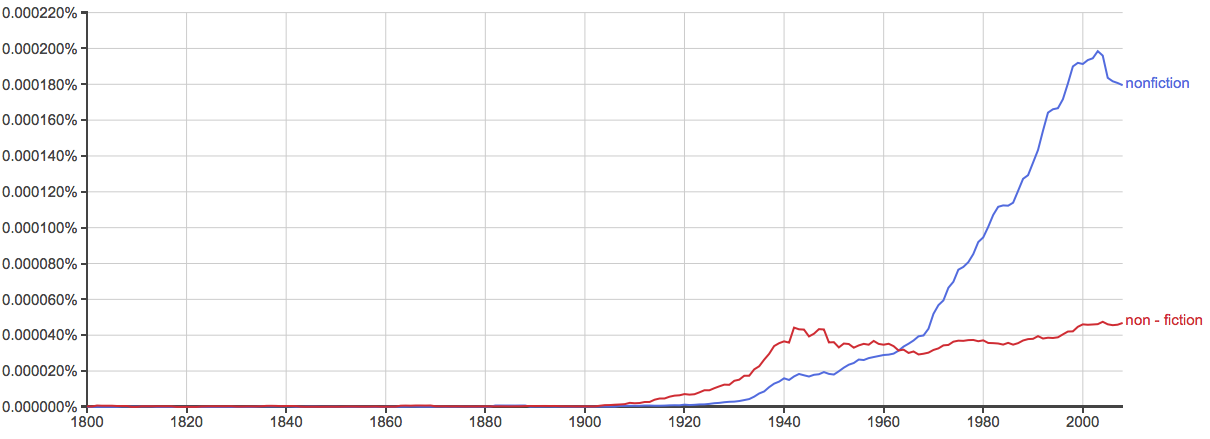

Nonfiction sometimes appears as a hyphenated word: non-fiction. Either spelling is accepted, but, as you can see from the below graph, you can see that nonfiction is much more common.

Trick to Remember the Difference

A work that is nonfiction is a recounting of real events. A work of fiction is based on made-up people or events.

Since fiction and false begin with the same letter, we can easily remember that fiction is false , even if it is an excellent and well-crafted story.

You can extend this mnemonic to nonfiction as well. A nonfiction story is not fake .

Is it fiction or nonfiction? Fiction and nonfiction are two categories of writing.

- Fiction deals with made-up people or events.

- Nonfiction deals with real life.

Fiction is also a word that is commonly used to describe anything that is not true , like wild accusations or patently false testimony. This article, though, is a work of nonfiction.

Since fiction and false each begin with the letter F , remembering that a work of fiction is not a true story should not be difficult to remember.

It might be difficult to remember the difference between these words, but remember, you can always reread this article for a quick refresher.

Fiction vs. nonfiction?

Nonfiction writing recounts real experiences, people, and periods. Fiction writing involves imaginary people, places, or periods, but it may incorporate story elements that mimic reality.

Your writing, at its best

Compose bold, clear, mistake-free, writing with Grammarly's AI-powered writing assistant

What is the difference between fiction and nonfiction ?

The terms fiction and nonfiction represent two types of literary genres, and they’re useful for distinguishing factual stories from imaginary ones. Fiction and nonfiction writing stand apart from other literary genres ( i.e., drama and poetry ) because they possess opposite conventions: reality vs. imagination.

What is fiction ?

Fiction is any type of writing that introduces an intricate plot, characters, and narratives that an author invents with their imagination. The word fiction is synonymous with terms like “ fable ,” “ figment ,” or “ fabrication ,” and each of these words has a collective meaning: falsehoods, inventions, and lies.

Not all fiction is entirely made-up, though. Historical fiction, for example, features periods with real events or people, but with an invented storyline. Additionally, science fiction novels function around real scientific theories, but the overall story is untrue.

What is nonfiction ?

Nonfiction is any writing that represents factual accounts on past or current events. Authors of nonfiction may write subjectively or objectively, but the overall content of their story is not invented (Murfin 340).

Works of nonfiction are not limited to traditional books, either. Additional examples of nonfiction include:

- Instruction manuals

- Safety pamphlets

- Journalism

- Recipes

- Medical charts

Comparing fiction and nonfiction texts

Outside of reality vs. imagination, nonfiction and fiction writing possess several typical features.

Fictional text features:

- Imaginary characters, settings, or periods

- A subjective narrative

- Novels, novellas, and short stories

- Literary fiction vs. genre fiction ( e.g., sci-fi, romance, mystery )

Nonfiction text features:

- Real people, events, and periods

- An authoritative narrative

- Autobiographies, letters, journals, essays, etc .

- Venn diagrams, anchor charts, mini-lessons, extension activities

- Index, citations, and bibliographies

- Academic/peer-reviewed publishers

What does fiction and nonfiction have in common?

Oftentimes, an elaborate work of fiction has more in common with nonfiction than a simple fairy tale or children’s book. Examples of shared traits include:

- Major literary publishers ( e.g., Hachette Books and HarperCollins )

- Photographic and illustrated book covers

- Stylistic elements such as an index, glossary, or citations

- Themes involving history, mythology, and science

- Creative prose narratives

Prose narratives of fiction vs. nonfiction

According to The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms , we can narrowly distinguish fiction from nonfiction through the use of “prose narratives,” a term that refers to an author’s storytelling form.

For works of fiction , authors typically use prose narratives such as the novel , novella , or short story . But for nonfiction books, prose narratives take the form of biographies , expository , letters , essays, and more.

Prose narratives of fiction

A novel is a long, fictional story that involves several characters with an established motivation, different locations, and an intricate plot. Examples of novels include:

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Beloved by Tony Morrison

A novel is not the same as a novella , which is a shorter fictional account that ranges between 50-100 pages long. You’ve likely heard of novellas such as:

- Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

- Animal Farm by George Orwell

Lastly, the short story normally contains 1,000-10,000 words and focuses on one event or length of time, such as:

- The Cask of Amontillado by Edgar Allen Poe

- The Story of an Hour by Kate Chopin

Prose narratives of nonfiction

Since nonfiction represents real people, experiences, or events, the most common prose narratives of nonfiction include:

- Biographies

- Autobiographies

- Journals

- Essays

- Informational texts

Biographies and autobiographies

A biography is written about another person, while an autobiography’s author tells the story of their own life. Popular biographies include:

- Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer

- Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

The difference between the two modes of nonfiction is further illustrated with autobiographies such as:

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass

- I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood up for Education and Was Shot by Malala Yousafzai

Journals and letters

Journals , diaries , and letters provide a glimpse into someone’s life at a particular moment. Diaries and letters are great resources for historical contexts, and especially for periods involving war or political scandals.

Journal and letters examples:

- The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

- Ever Yours: The Essential Letters by Vincent van Gogh

Essay writing

By definition, an essay is a short piece of writing that explores a specific subject, such as philosophy, science, or current events. We read essays within magazines, websites, scholarly journals, or through a published collection of essays.

Essay examples:

- Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace

- The Source of Self-Regard by Toni Morrison

Informational texts

Informational texts present clear, objective facts about a particular subject, and often take the form of periodicals, news articles, textbooks, printables, or instruction manuals. The difference between informational texts and biographical writing is that biographies possess a range of subjectivity toward a topic, while informational writing is purely educational.

Publishers of informational texts also tailor their writing toward an audience’s reading comprehension. For instance, instructions for first-grade reading levels use different vocabularies than a textbook for college students. The key similarity is that informational writing is clear and educational.

Genres of fiction vs. nonfiction

The French term genre means “kind” or “type,” and genres organize different styles, forms, or subjects of literature. Some sources believe fiction is categorized by genre fiction and literary fiction , while others believe that literary fiction is a subgenre of fiction itself. The same arguments exist within nonfiction genres, except nonfiction is organized by subject matter or writing style.

Whichever way you look at it, all nonfiction and fiction have distinct genres and subgenres that overlap, and there’s no single way to categorize literature without spurring controversy. If you’re ever doubtful about a particular book, try checking the publisher’s website.

What is literary fiction ?

If we stick to the dry characteristics of literary fiction , we can define it as any writing that produces an underlying commentary on the human condition. More specifically, literary fiction often involves a metaphorical , poetic narrative or critique around topics such as war, gender, race, sex, economy, or political ideologies.

Literary fiction examples:

- Quicksand by Nella Larsen

- The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera

- The Sellout by Paul Beatty

What is genre fiction ?

Broadly speaking, genre fiction (or popular fiction ) is any writing with a specific theme and the author’s marketability toward a particular audience (aka, the novel is likely a part of a book series). The most common genres of “ genre fiction ” include:

- Science Fiction

- Suspense/Thriller

Crime fiction and mystery

Crime fiction and mystery novels focus on the motivation of police, detectives, or criminals during an investigation. Four major subgenres of crime fiction and mystery include detective novels, cozy mysteries, caper stories, and police procedurals.

Crime fiction and mystery examples:

- The Godfather by Mario Puzo

- The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Steig Larsson

The fantasy genre traditionally occurs in medieval-esque settings and often includes mythical creatures such as wizards, elves, and dragons.

Fantasy examples:

- The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkein

- A Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin

The romance genre features stories about romantic relationships with a focus on intimate details. Romance themes often involve betrayal or heroism and elements of sensuality, idealism, morality, and desire.

Romance examples:

- Dead Until Dark by Charlaine Harris

- Fifty Shades of Grey by E.L. James

Science fiction

Science fiction is one of the largest growing genres because it encompasses several subgenres, such as dystopian, apocalyptic, superhero, or space travel themes. All sci-fi novels incorporate real or imagined scientific concepts within the past, future, or a different dimension of time.

Science fiction examples:

- Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler

- The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin

Suspense and horror

Sometimes described as two separate genres, suspense and horror writing focuses on the pursuit and escape of a main character or villain. Suspense writing uses cliffhangers to “grip” readers, but we can distinguish the horror genre through supernatural, demonic, or occult themes.

Suspense and horror examples:

- The Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris

- The Shining by Stephen King

Genres of nonfiction

Finally, we meet again in the nonfiction section. When it comes to nonfiction literature, the most common genres include:

- Autobiography/Biography (see “prose narratives” )

Narrative nonfiction

A memoir recounts the memories and experiences for a specific timeline in an author’s life. But unlike an autobiography, a memoir is less chronological and depends on memories and emotions rather than fact-checked research.

Memoir examples:

- Wild by Cheryl Strayed

- When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

Self-help writing focuses on delivering a lesson plan for self-improvement. Authors of self-help books describe experiences like a memoir, but the overall purpose is to teach readers a skill that the author possesses.

Self-help examples:

- How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie

- The Power of Now by Eckhart Tolle

The expository genre introduces or “ exposes ,” a complex subject to readers in an understandable manner. Expository books often take the form of children’s books to provide a clear, educational summary on topics such as history and science.

Examples of adult vs. children’s expository books include:

- Death by Black Hole by Neil deGrasse Tyson

- A Black Hole is Not a Hole by Carolyn Cinami Decristofano

Narrative nonfiction (or “ creative nonfiction ”) tells a true story in the form of literary fiction. In this case, the author presents an autobiography or biography with an emphasis on storytelling over chronology.

The line between creative nonfiction and literary fiction is thin when the narrative’s presentation is too subjective, and when specific facts are omitted or exaggerated. Literary scholars refer to such works as “ faction ,” a portmanteau word for writing that blurs the line between fiction and nonfiction (Murfin 177).

Narrative nonfiction examples:

- In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

- The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson

Additional resources for nonfiction vs. fiction ?

Understanding the elements of fiction vs. nonfiction writing is a common core standard for language arts (ELA) programs. If you’re looking to learn specific forms of fiction and nonfiction writing, The Word Counter provides additional articles, such as:

- Transition Words: How, When, and Why to Use Them

- What Are the Most Cringe-Worthy English Grammar Mistakes?

- Italics and Underlining: Titles of Books

Test Yourself!

Before you visit your next writing workshop, class discussion, or literacy center, test how well you understand the difference between fiction and nonfiction with the following multiple-choice questions (no peeking into Google!)

- True or false: An author’s imagination does not invent nonfiction writing. a. True b. False

- Which term is synonymous with fiction? a. Fact b. Fable c. Reality d. None of the above

- Which is a type of nonfiction writing? a. Novels b. Memoirs c. Novellas d. Short stories

- Which is not a trait of literary fiction? a. Underlying commentary on the human condition b. Poetic narrative c. Social and political commentary d. None of the above

- Which genre of nonfiction is the closest to literary fiction? a. Memoirs b. Expository c. Narrative nonfiction d. Self-help

Photo credits:

[1] Photo by Suad Kamardeen on Unsplash [2] Photo by Jonathan J. Castellon on Unsplash

- “ Essay .” Lexico , Oxford University Press, 2020.

- “ Fiction .” The Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Inc., 2020.

- MasterClass. “ What Is the Mystery Genre? Learn About Mystery and Crime Fiction, Plus 6 Tips for Writing a Mystery Novel .” MasterClass , 15 Aug 2019.

- Mazzeo, T.J. “ Writing Creative Nonfiction .” The Great Courses , 2012, pp.4.

- Murfin, R., Supryia M. Ray. “ The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms .” Third Ed, Bedford/St. Martins , 2009, pp. 177-340.

- “ Nonfiction .” Lexico , Oxford University Press, 2020.World Heritage Encyclopedia. “ List of Literary Genres .” World Library Foundation , 2020.

Alanna Madden

Alanna Madden is a freelance writer and editor from Portland, Oregon. Alanna specializes in data and news reporting and enjoys writing about art, culture, and STEM-related topics. I can be found on Linkedin .

Recent Posts

Allude vs. Elude?

Bad vs. badly?

Labor vs. labour?

Adaptor vs. adapter?

Fiction vs. Nonfiction: Literature Types (Compared)

- by Team Experts

- July 2, 2023 July 3, 2023

Discover the surprising differences between fiction and nonfiction literature types in this eye-opening comparison.

In conclusion, literature types are an essential aspect of written works that help readers understand the content, style, and purpose of a particular piece. Fiction and nonfiction are two major literature types that differ in their narrative style and content. Fiction includes imaginary stories and creative writing, while nonfiction includes fact-based writing and informational texts. Understanding these literature types and their differences can help readers choose the right book for their needs.

What are the Different Literary Types?

Narrative style in fiction and nonfiction writing, real-life events in nonfiction vs creative writing in fiction, informational texts: understanding their role in literature, common mistakes and misconceptions.

Overall, understanding the differences in narrative style between fiction and nonfiction writing is crucial for effective storytelling . While some elements may overlap, such as plot structure and conflict, the use of characterization, dialogue, imagery, tone, mood, setting, theme, foreshadowing, flashback, symbolism, irony, and climax differ greatly between the two styles . It is important to consider these elements when choosing a narrative style and to use them effectively to engage and captivate the reader.

Overall, the key difference between real-life events in nonfiction and creative writing in fiction is the purpose of the writing and the level of fictionalization. Nonfiction aims to inform and educate readers about real-life events, while fiction aims to entertain and engage readers through creative writing. Nonfiction requires accurate and reliable information about real-life events, while fiction requires creative ideas and imaginative storytelling. Nonfiction should be based on real-life events and should not be overly fictionalized, while fiction can be completely made up or based on real-life events with varying degrees of fictionalization. Both nonfiction and fiction require editing and revision to improve the clarity, coherence, and effectiveness of the writing.

Overall, understanding the role of informational texts in literature can provide readers with valuable knowledge and insights on various topics. However, it is important to approach these texts with a critical eye and consider the potential risks of biased or false information. By analyzing the purpose, type, structure, credibility , audience, and impact of informational texts, readers can gain a deeper understanding of the world around them.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The Truth About Fiction vs. Nonfiction

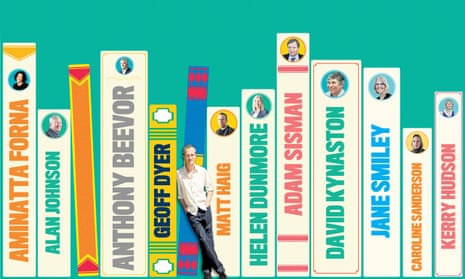

Aminatta forna, from reporter to novelist, and everything in between.

Some years ago I was invited to judge a literature prize. The prize was awarded on the basis of a writer’s body of work, but the prize organizers had limited the scope to works of fiction. Works of non-fiction by the same writer were not included. This made no sense to me and I said so. As a novelist and essayist I see the two forms as conjoined twins, sharing themes and concerns, which all come out of the same brain, but flow into two separate entities. The same is true of every writer I can think of who writes both fiction and non-fiction. Marilynne Robinson’s novels Gilead , Home and Housekeeping and her powerful essays examine her reflections on Christanity and morality. Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera, Chronicle of a Death Foretold and News of a Kidnapping tell of the history and making of modern Colombia. Michael Ondaatje says he wrote first his memoir Running in the Family about growing up in Sri Lanka, but felt the need to turn to fiction to write about the Sri Lankan civil war. Aleksandar Hemon’s Nowhere Man and his collection of essays The Book of My Lives excavate themes of loss and displacement from his hometown of Sarajevo.

Twelve years ago I was being interviewed on the radio about my debut novel Ancestor Stones , the first thing I had published following a memoir which had garnered a fair bit of attention. The novel told the stories of four women, each sisters growing up in a different era of a country’s history. The interviewer asked me a question that confounded me. Why I hadn’t written it as a work of nonfiction, she wanted to know. I replied that it would have been difficult, the people didn’t exist and the events I described in their lives hadn’t happened. Later I spent a little time pondering that question. Did the interviewer, who had spoken to hundreds of writers in her career as a critic and radio host, really have so little understanding of the process? I wondered if she thought, as I discovered a good many people lazily assumed, that the family described in the story was nothing more than a lightly disguised version of my own. The historical background to the stories was true, sure, but the stories themselves, the people, I had made all that up.

A while later I was guest lecturer at a British university giving a talk and reading from my memoir to a group of students of creative nonfiction. My publishers had described the book as a “story of a father, a family, a country and a continent.” I had grown up in Sierra Leone, the daughter of a political activist and dissident. The story I told was of my search to uncover events surrounding my father’s murder in the 1970s when I was eleven years old. Back then the kind of political upheaval that was played out in Sierra Leone was being played out all over the continent as nascent democracies of newly independent nations were hijacked by authoritarian regimes.

At the end of the session a middle-aged woman raised her hand: “Why,” she asked “had I gone to all the bother of writing a work of nonfiction when I could just as easily have written a novel.” To write the truest account I could mattered, I answered, a little testily, because these things actually happened. It mattered to my family, to the participants, the witnesses, and the people of the country. This was a book about how oppression unchecked causes a country to implode 25 years later, part of an unveiling of the things that had happened and never been spoken about.

“Each time a writer begins a book they make a contract with all the people who buy their book.”

I began my working career as a journalist, because having grown up in a country where the state controlled the newspapers and the narrative and fed misinformation to the public, truth telling was important to me. In this era of “fake news” my background as a journalist has turned out to be a useful one. I was trained to fact check and to question the reliability of each and every source, and hence these days I’m astonished to discover the credulity of the public, including some friends and Facebook acquaintances, who take apparently at face value stories which would not withstand a few moments scrutiny. “Fake news” has been around a long time from Joseph Goebbels to the British tabloids and the American entertainment magazines. What has changed thanks to social media is the mode and speed of delivery, also the messenger, from basement trolls, to Russian bots all the way to the leader of a Western superpower, who according to various sources lies publicly roughly five or six times a day, whilst at the same time condemning the output of the mainstream media as fake.

A decade after I joined the BBC however, I was done. I was never content as a reporter for a large organization. The problem, I gradually came to realize, was that I was obliged to speak with a voice not my own but another voice belonging to another kind of person. It was the voice of the BBC, a reflection of the broadcaster’s viewers and listeners, people who had on the whole lived lives quite unlike my own, who took for granted a shared knowledge, shared levels of experience, of familiarity and unfamiliarity with their world and the world beyond. They were the great middle class of middle England, and I was not one of them. The voice stuck in my craw. Everyone writes for their own reasons and if there is one thing that moves me to set out my thoughts on paper it is this: that ever since the years of my childhood I have never seen the world the way I am constantly being told it is and I could only do so in my own voice.

In the time I have been writing there have been huge shifts in the sphere of the realm we now call creative nonfiction. Where once most first person nonfiction was generally confined to travel writing, narrative journalism and essays, the late 20th century has seen a huge explosion in personal memoir, from Tobias Wolff and Mary Karr’s tales of family dysfunction to Jung Chang’s “memoir as narrative history,” Wild Swans, set against the historical back-sweep of the Chinese cultural revolution. In nature writing, Annie Dillard’s self-described “theodyssey,” which sees creation in tiny Tinker’s Creek, Helen Macdonald’s exploration of grief and falconry, the expanses of Barry Lopez Arctic Dreams . There are hybrids of every kind: William Fiennes’s account of his brother’s epilepsy combined with the history of the science of the brain in The Music Room , the magic and myth of Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior , and again Michael Ondaatje’s Running in the Family which moves beyond the very idea of form.

The writer of creative nonfiction and the writer of fiction have much in common. Both employ the techniques of narrative, plot, pace, mood and tone, considerations of tense and person, the depiction of character, the nuance of dialogue. Where the difference lies is that the primary source of the fiction writer is first and foremost their imagination, followed by their powers of observation and maybe a certain amount of research. The primary resource of the writer of creative nonfiction is lived experience, above and beyond all, memory, add to that observation and research.

Another difference lies in what I call the contract with the reader. Each time a writer begins a book they make a contract with all the people who buy their book. If the book is a work of fiction the contract is pretty vague, essentially saying: “Commit your time and patience to me and I will tell you a story.” There may be a sub-clause about the effort to entertain or to thrill, or some such. In my contract for each of my novels I have promised to try to show my readers the world in a way they have not seen before, or perhaps show it to them in a way they had not considered before. A contract for a work of nonfiction is a more precise affair. The writer says, I am telling you, and to the best of my ability, what I believe to be true. This is a contract not to be broken lightly.

“Where once most first person nonfiction was generally confined to travel writing, narrative journalism and essays, the late 20th century has seen a huge explosion in personal memoir.”

There are those writers of what is published under the heading nonfiction who freely confess to inventing some of their material. Clearly they have a different kind of contract with the reader from mine, or perhaps no contract at all. Whenever I am on stage with memoirists who do this, they start by explaining how the story was improved by those additions and that none of it mattered much anyway. In the words of the British writer Geoff Dyer: “The contrivances in my nonfiction are so factually trivial that their inclusion takes no skin off even the most inquisitorial nose.” And then there are writers such as W.G. Sebald and more recently Karl Ove Knausgaard who deliberately place their work in the twilight zone between fact and fiction. I won’t argue these writers case for them here, they know what they are doing.

For the memoirist who purports to be telling only the truth and then is caught lying a special kind of fury is reserved. In 2003, at a book festival in Auckland I met a woman named Norma Khouri who had written a memoir called Forbidden Love which told the story of the honor killing of her childhood best friend in their native Jordan at the hand of the friend’s own brother. The girl’s supposed crime was to have fallen in love with a Christian. The book sold half a million copies and at the time we met Khouri had founded and was raising money for an organization to save Jordanian women in danger of being killed for “honor.” We appeared on the same panel, afterwards we drank at the bar. Norma was fun, she seemed to have survived her ordeal well, too well some said later, but I know many people who have faced extreme situations and they are often perfectly cheerful. I didn’t think too much about her American accent either, she told me, or perhaps I assumed, that she had been to the International School in Jordan. All in all I spent maybe two hours in her company.

I flew back to the UK and a month or two later I received an email from the panel chair David Leser, a well known Australian journalist and feature writer. He wrote that he had stayed up with Khouri late into the night after we had left the bar, had been deeply moved by her fragility and courage, even, he admitted later in an article, fallen a little in love with her.

“I began my working career as a journalist, because having grown up in a country where the state controlled the newspapers and the narrative and fed misinformation to the public, truth telling was important to me.”

Khouri was a fraud. She had left Jordan for Chicago at the age of three and had not set foot in her homeland since. The whole story had been a hoax. No best friend, no Christian lover, no honor killing. The rage at Khouri lasted for months. A decade later a filmmaker made a documentary about her: Forbidden Lie$, in which Khouri continues to try to vindicate herself, despite the mountain of seemingly irrefutable evidence including accusations of financial misconduct and her inability to provide evidence to prove the existence of her dead friend and her friend’s family. To Leser she admitted she had lied but, she said, for the right reasons. Those who met her including Leser (and me) never could decide whether she was a trickster, a fantasist or even a woman with some hidden trauma of her own.

Everyone, even Norma Khouri, has their own reasons to write, their own justifications for the choices they make, their contract with their readers, their contract with themselves. I ask my students of both fiction and nonfiction, but most of all those who wish to write personal memoirs (perhaps because of all the forms of writing it is the one most often confused with therapy): Why do people need to hear this story? Not, Why do you want to write this story? i.e Not what’s in it for you. What’s in it for them?

When I come to a begin a book it is usually with a question in mind, something I have been thinking about and I want to ask the reader to think about too. What turns the book into a novel is the arrival of a character. Elias Cole, the ambitious, morally equivocating coward in The Memory of Love came to me through a chance remark by a friend about her father, a successful academic who had somehow survived a villainous regime where his colleagues had not. I hired a man to paint my house who I discovered (on the last day) was a thrice imprisoned violent offender. Out of that encounter came Duro, the handyman Laura unthinkingly allows into her holiday home in The Hired Man .

My nonfiction begins with a question too. The difference, if I can pinpoint it, is that with nonfiction when I start to write I believe I may have come up with an answer, an answer of sorts at least. Don DeLillo once quipped that a fiction writer starts with meaning and manufactures events to represent it; the writer of creative nonfiction starts with events, then derives meaning from them. Gillian Slovo, both a novelist and memoirist, once told me that with nonfiction you always know what your story is, with fiction that isn’t necessarily the case. I think there is truth in both statements. It’s easy to lose sight of your story, meaning the deeper truth you are reaching for in fiction, the more it can be a slippery process. When it comes to nonfiction I discard or store numbers of stories, sometimes because I can’t think of the right way to tell them, but more often because although I know the story in narrative terms, I have not yet arrived at its meaning.

The best stories can arrive quite by chance, replete with meaning and maybe even with a great character through whom to tell them. Some years ago a stray dog I had adopted in Sierra Leone and given to a friend was hit by a car. The story of the effort to save her life, which involved many ordinary people in a country still on its knees after ten years of civil war, introduced me to Dr. Gudush Jalloh who was then the only working vet in the country (the others having all fled or been killed). Here was a man who devoted himself to the lives of the city’s street dogs, who, in the face of an announced cull, had stood up to represent the dogs before the City Council, who had driven around at night rousing the local people into action to save the lives of dogs. I wrote an essay for Granta , “The Last Vet,” about Gudush Jalloh, for to me everything about him represented something to which I had been giving a great deal of recent thought, the gap between Western and West African modes of thought. By writing about him I could reveal something to West Africans about their own culture and reverse the gaze on Western culture.

“The conversation,” I later wrote after spending two weeks in his company, will range over days: “African pragmatism and reality, Western sentiment, the schism between the values of the two and the West’s own conflicted treatment of animals. Of Jalloh’s lot in trying to embrace, negotiate and reconcile so many ways of thinking.”

Sometimes meaning comes later. I lived in Tehran when I was 14. The year was 1979, my mother was married to a diplomat who headed the UN’s development projects in the country. I found myself a teenage witness to one the great revolutions of all time, from its heady flowering in the hands of writers and artists, to the crushing of new found freedoms by the mullahs a year later. The events, their sequence and consequence, made no real sense to me at the time.

In the essay 1979 I wrote: “I was, at that time, an ardent revolutionary. I had a poster of Che Guevara on my wall and a sweatshirt bearing his image. I read his speeches and admitted to no one that I found them impenetrable. I was ardent—all I lacked was a revolution. And now here was a revolution [between the progressive authoritarian Shah and the defiant yet regressive Khomeini] and I had no idea whose side I was on.”

Decades later, watching the hopes and disappointment of the Arab Spring those months in Iran came back to me, this time with a fresh understanding, of the ways, the stepping stones, by which freedoms can also be hijacked and subverted. Of never believing it can be that easy.

At other times a thought process, which has been going on for months or even years, might begin to arrange itself into a sort of pattern. Like a pebble in my pocket I carry the notion around, collecting other pebbles which look similar, until I have a pocketful. I’ll spread them out on the table, these notes and observations, looking for the points of connection. Then there comes the moment, hopefully, when I see it. In that way fiction and nonfiction are not so different, that part of the process is the same. With fiction, though, I will begin to search for a narrative with which to veil those ideas.

Here’s Zadie Smith: “Tell the truth through whichever veil comes to hand—but tell it. Resign yourself to the lifelong sadness that comes from never being satisfied.”

And therein lies the difference. In nonfiction the writer seeks to remove the veils, to strip away and to reveal what is really there. On my noticeboard in my office in London I had pinned the lines: “Nonfiction reveals the lies, but only metaphor can reveal the truth.” I don’t know who said it, I’m afraid. I think it was Nadine Gordimer, but I’ve quoted it so many times that on the internet it is now ascribed to me. The quotation seems to me to be intended to elevate fiction as the higher form, and I agree that fiction allows me to reach for another less literal kind of truth. But there is something about stripping away the myths that veil the lies that is vitally satisfying. There , says the writer of nonfiction, I said it! I said it! And so is thus spared the lifelong sadness of never being satisfied.

After a long spell writing fiction I find I inevitably seek recourse in the clarity, the exactitude of nonfiction, a flight from the coyness of fiction. Then comes a time when I have said what needs to be said, facts become constraining and it’s time to revel in the boundless freedoms of the imagination once more. A novel begins with the thought: What if? A work of creative nonfiction begins with words: What is. The writer says to the reader: Wake up, smell the coffee and look at what is there.

The preceding is from the new Freeman’s channel at Literary Hub, which will feature excerpts from the print editions of Freeman’s , along with supplementary writing from contributors past, present and future. The latest issue of Freeman’s , a special edition featuring 29 of the best emerging writers from around the world, is available now.

Aminatta Forna

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

- Key Differences

Know the Differences & Comparisons

Difference Between Fiction and Nonfiction

Fiction can be understood as the literary work created as per one’s imagination, i.e. the author’s creative thought or made-up stories and characters. On the other hand, reading a nonfictional work means you are reading something that actually happened or someone that actually exist, i.e. it is not a cooked up story, rather it is fact and evidence-based account.

Now, in this article, we are going to look at the differences between fiction and nonfiction

Content: Fiction Vs Nonfiction

Comparison chart, definition of fiction.

Fiction can be understood as an imaginative creation, which does not exist in reality, rather it is produced by the author’s creative thought. It is a type of imaginative prose literature, which can be both spoken or written account containing imaginary characters, events and descriptions.

Writing fiction means that the writer creates their own fantasy world, in their minds and introduce it to the rest of the world through the book. As the story is not real and factual, they cook it up in a way that makes it very interesting and engaging.

From the reader’s point of view, fictional work refers to the creative fabrication of a fantasy world, by the author, i.e. the author imagines the entire story and its characters, the overall plot, dialogues and setting.

The work of fictions is never based on a true story, and so when we go through such works, it visualizes such situation which we may never face in reality or we will come across those characters who we may never get a chance to meet in our real life and also take us to a world where we may never go otherwise.

It is that form of entertainment or art which contains hypothetical plot and characteristics in any format, such as comics, television programs, audio recordings, drama, novel, novella, short story, fairy tales, films, fables, etc. It includes writing related to mystery, suspense, crime thrillers, fantasies, science fiction, romance, etc.

So, fictional writings have the ability to inspire, or change the perspectives towards life, engage in the story, surprise with the twist and turn and also scare or amaze with the ending.

Definition of Nonfiction

Nonfiction is the widest form of literature which contains informative, educational and factual writings. It is a true account or representation of a particular subject. It claims to portray authentic and truthful information, description, events, places, characters or existed things.

Although, the statements and explanation provided may or may not be exact and so it is possible that it provides a true or false narrative of the subject which is talked about. Nevertheless, the author who created the account often believes or claim it to be true, when it is being created.

When a nonfictional work is created, the emphasis is given to the simplicity, clarity, and straightforwardness. It encompasses essays, expository, memoirs, self-help, documentaries, textbooks, biographies and autobiographies, newspaper report and books on history, politics, science, technology, business and economics.

The main purpose of reading nonfictional books is to learn more about a subject and increase the knowledge base.

Key Differences Between Fiction and Nonfiction

Upcoming points will explain the difference between fiction and nonfiction

- Fiction is a literary work which contains the imaginary world, i.e. characters, situation, setting and dialogue. On the flip side, nonfiction implies that type of writing which provides true information or contains such facts or events which are real.

- Fiction is subjective in nature, as the author has the freedom to add his opinion or perspective to the writeup. As well as the writer can elaborate any character, plot or setting as per his imagination. However, nonfiction is objective because the writer cannot add his/her opinion, as it is purely fact-based and authentic and because there is no scope for imagination, the writer needs to be straightforward.

- When writing fiction, the author has the flexibility, to move the story in the direction which make it more exciting and interesting. Conversely, nonfictional writers do not have such flexibility because they have to provide information which is true and real.

- In a fictional work, the writer is of the opinion that the audience will follow and understand the theme which is hidden in the content. In fact, the story can be interpreted by the readers in different ways depending on their level of understanding. As against, in a nonfictional work, there is a simple and direct presentation of the information and facts. So, there is only one interpretation.

- The main purpose of writing fiction is to entertain the readers, whereas nonfiction writing educates the reader about a subject or to further their knowledge about something.

- In fictional writing, references may or may not be provided by the author. On the other hand, in nonfictional writing references are provided compulsorily by the writer wherever required, so as to make the writing more credible.

- Fiction is always from the perspective of the narrator, i.e. the writer, or the character, i.e. the main or supporting character of the story. In contrast, non-fiction is always from the perspective of the author.

By and large, fiction and nonfiction are diametrically opposite to one another. In a fictional work, most of the part is imaginary i.e. scripted by the author. Fictional stories help the readers to take a break from their everyday boring life, and lost in the dreamy world of excitement, for quite some time.

On the contrary, nonfiction is all about factual stories, that emphasize on actual events, characters and places. It tends to teach and explain things to the readers.

You Might Also Like:

Md Sumon Ahmed says

May 2, 2020 at 9:27 pm

Thank You Very helpfull articel.

Richard Scott Rahn says

November 20, 2021 at 2:07 am

I have been reading posts regarding this topic and this post is one of the most interesting and informative one I have read. Thank you for this!

Barrack harruner says

July 20, 2022 at 12:11 pm

this post is one among the interesting post that i have see its such an amazing post👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌👌

Kevin Gustafson says

July 29, 2022 at 8:38 pm

kitley says

March 22, 2023 at 5:31 pm

So helpful…

Nikkita Estep says

April 14, 2023 at 3:59 am

This is an interesting post

Mbasugh Fanen says

September 19, 2023 at 2:01 am

This post is so amazing it’s interesting educative and informative as well when I get more time will share it with many of my friends keep on please 🇧🇹🇧🇹🇧🇹🇧🇹🇧🇹🇧🇹🇧🇹🇧🇹🇧🇹🇧🇹🇧🇹🇧🇹

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.7: Writing About Fiction and Creative Nonfiction

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 101130

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

Writing an analysis of a piece of fiction can be a mystifying process. First, literary analyses (or papers that offer an interpretation of a story) rely on the assumption that stories must mean something. How does a story mean something? Isn't a story just an arrangement of characters and events? And if the author wanted to convey a meaning, wouldn't he or she be much better off writing an essay just telling us what he or she meant?

It's pretty easy to see how at least some stories convey clear meanings or morals. Just think about a parable like the prodigal son or a nursery tale about "crying wolf." Stories like these are reduced down to the bare elements, giving us just enough detail to lead us to their main points, and because they are relatively easy to understand and tend to stick in our memories, they're often used in some kinds of education.

But if the meanings were always as clear as they are in parables, who would really need to write a paper analyzing them? Interpretations of fiction would not be interesting if the meanings of the stories were clear to everyone who reads them. Thankfully (or perhaps regrettably, depending on your perspective) the stories we're asked to interpret in our classes are a good bit more complicated than most parables. They use characters, settings, and actions to illustrate issues that have no easy resolution. They show different sides of a problem, and they can raise new questions. In short, the stories we read in class have meanings that are arguable and complicated, and it's our job to sort them out.

It might seem that the stories do have specific meanings, and the instructor has already decided what those meanings are. Not true. Instructors can be pretty dazzling (or mystifying) with their interpretations, but that's because they have a lot of practice with stories and have developed a sense of the kinds of things to look for. Even so, the most well-informed professor rarely arrives at conclusions that someone else wouldn't disagree with. In fact, most professors are aware that their interpretations are debatable and actually love a good argument. But let's not go to the other extreme. To say that there is no one answer is not to say that anything we decide to say about a novel or short story is valid, interesting, or valuable. Interpretations of fiction are often opinions, but not all opinions are equal.

So what makes a valid and interesting opinion? A good interpretation of fiction will:

- avoid the obvious (in other words, it won't argue a conclusion that most readers could reach on their own from a general knowledge of the story)

- support its main points with strong evidence from the story

- use careful reasoning to explain how that evidence relates to the main points of the interpretation.

The following steps are intended as a guide through the difficult process of writing an interpretive paper that meets these criteria. Writing tends to be a highly individual task, so adapt these suggestions to fit your own habits and inclinations.

Writing an Essay on Fiction in 9 Steps

1. become familiar with the text.

There's no substitute for a good general knowledge of your story. A good paper inevitably begins with the writer having a solid understanding of the work that they interpret. Being able to have the whole book, short story, or play in your head—at least in a general way—when you begin thinking through ideas will be a great help and will actually allow you to write the paper more quickly in the long run. It's even a good idea to spend some time just thinking about the story. Flip back through the book and consider what interests you about this piece of writing—what seemed strange, new, or important?

2. Explore potential topics

Perhaps your instructor has given you a list of topics to choose, or perhaps you have been asked to create your own. Either way, you'll need to generate ideas to use in the paper—even with an assigned topic, you'll have to develop your own interpretation. Let's assume for now that you are choosing your own topic.

After reading your story, a topic may just jump out at you, or you may have recognized a pattern or identified a problem that you'd like to think about in more detail. What is a pattern or a problem?

A pattern can be the recurrence of certain kinds of imagery or events. Usually, repetition of particular aspects of a story (similar events in the plot, similar descriptions, even repetition of particular words) tends to render those elements more conspicuous. Let's say I'm writing a paper on Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein . In the course of reading that book, I keep noticing the author's use of biblical imagery: Victor Frankenstein anticipates that "a new species would bless me as its creator and source" (52) while the monster is not sure whether to consider himself as an Adam or a Satan. These details might help me interpret the way characters think about themselves and about each other, as well as allow me to infer what the author might have wanted her reader to think by using the Bible as a frame of reference. On another subject, I also notice that the book repeatedly refers to types of education. The story mentions books that its characters read and the different contexts in which learning takes place.

A problem, on the other hand, is something in the story that bugs you or that doesn't seem to add up. A character might act in some way that's unaccountable, a narrator may leave out what we think is important information (or may focus on something that seems trivial), or a narrator or character may offer an explanation that doesn't seem to make sense to us. Not all problems lead in interesting directions, but some definitely do and even seem to be important parts of the story. In Frankenstein , Victor works day and night to achieve his goal of bringing life to the dead, but once he realizes his goal, he is immediately repulsed by his creation and runs away. Why? Is there something wrong with his creation, something wrong with his goal in the first place, or something wrong with Victor himself? The book doesn't give us a clear answer but seems to invite us to interpret this problem.

If nothing immediately strikes you as interesting or no patterns or problems jump out at you, don't worry. Just start making a list of whatever you remember from your reading, regardless of how insignificant it may seem to you now. Consider a character's peculiar behavior or comments, the unusual way the narrator describes an event, or the author's placement of an action in an odd context. (Step 5 will cover some further elements of fiction that you might find useful at this stage as well.)

There's a good chance that some of these intriguing moments and oddities will relate to other points in the story, eventually revealing some kind of pattern and giving you potential topics for your paper. Also keep in mind that if you found something peculiar in the story you're writing about, chances are good that other people will have been perplexed by these moments in the story as well and will be interested to see how you make sense of it all. It's even a good idea to test your ideas out on a friend, a classmate, or an instructor since talking about your ideas will help you develop them and push them beyond obvious interpretations of the story. And it's only by pushing those ideas that you can write a paper that raises interesting issues or problems and that offers creative interpretations related to those issues.

3. Select a topic with a lot of evidence

If you're selecting from a number of possible topics, narrow down your list by identifying how much evidence or how many specific details you could use to investigate each potential issue. Do this step just off the top of your head. Keep in mind that persuasive papers rely on ample evidence and that having a lot of details to choose from can also make your paper easier to write.

It might be helpful at this point to jot down all the events or elements of the story that have some bearing on the two or three topics that seem most promising. This can give you a more visual sense of how much evidence you will have to work with on each potential topic. It's during this activity that having a good knowledge of your story will come in handy and save you a lot of time. Don't launch into a topic without considering all the options first because you may end up with a topic that seemed promising initially but that only leads to a dead end.

4. Write out a working thesis

Based on the evidence that relates to your topic—and what you anticipate you might say about those pieces of evidence—come up with a working thesis. Don't spend a lot of time composing this statement at this stage since it will probably change (and a changing thesis statement is a good sign that you're starting to say more interesting and complex things on your subject). At this point in my Frankenstein project, I've become interested in ideas on education that seem to appear pretty regularly, and I have a general sense that aspects of Victor's education lead to tragedy. Without considering things too deeply, I'll just write something like, "Victor Frankenstein’s tragic ambition was fueled by a faulty education."

5. Make an extended list of evidence

Once you have a working topic in mind, skim back over the story and make a more comprehensive list of the details that relate to your point. For my paper about education in Frankenstein , I'll want to take notes on what Victor Frankenstein reads at home, where he goes to school and why, what he studies at school, what others think about those studies, etc. And even though I'm primarily interested in Victor's education, at this stage in the writing, I'm also interested in moments of education in the novel that don't directly involve this character. These other examples might provide a context or some useful contrasts that could illuminate my evidence relating to Victor. With this goal in mind, I'll also take notes on how the monster educates himself, what he reads, and what he learns from those he watches. As you make your notes keep track of page numbers so you can quickly find the passages in your book again and so you can easily document quoted passages when you write without having to fish back through the book.

At this point, you want to include anything, anything, that might be useful, and you also want to avoid the temptation to arrive at definite conclusions about your topic. Remember that one of the qualities that makes for a good interpretation is that it avoids the obvious. You want to develop complex ideas, and the best way to do that is to keep your ideas flexible until you’ve considered the evidence carefully. A good gauge of complexity is whether you feel you understand more about your topic than you did when you began (and even just reaching a higher state of confusion is a good indicator that you’re treating your topic in a complex way).

When you jot down ideas, you can focus on the observations from the narrator or things that certain characters say or do. These elements are certainly important. It might help you come up with more evidence if you also take into account some of the broader components that go into making fiction, things like plot, point of view, character, setting, and symbols.

Plot is the string of events that go into the narrative. Think of this as the "who did what to whom" part of the story. Plots can be significant in themselves since chances are pretty good that some action in the story will relate to your main idea. For my paper on education in Frankenstein , I'm interested in Victor's going to the University of Ingolstadt to realize his father's wish that Victor attend school where he could learn about a another culture. Plots can also allow you to make connections between the story you're interpreting and some other stories, and those connections might be useful in your interpretation. For example, the plot of Frankenstein , which involves a man who desires to bring life to the dead and creates a monster in the process, bears some similarity to the ancient Greek story of Icarus who flew too close to the sun on his wax wings. Both tell the story of a character who reaches too ambitiously after knowledge and suffers dire consequences.

Your plot could also have similarities to whole groups of other stories, all having conventional or easily recognizable plots. These types of stories are often called genres. Some popular genres include the gothic, the romance, the detective story, the bildungsroman (this is just a German term for a novel that is centered around the development of its main characters), and the novel of manners (a novel that focuses on the behavior and foibles of a particular class or social group). These categories are often helpful in characterizing a piece of writing, but this approach has its limitations. Many novels don't fit nicely into one genre, and others seem to borrow a bit from a variety of different categories. For example, given my working thesis on education, I am more interested in Victor's development than in relating Frankenstein to the gothic genre, so I might decide to treat the novel as a bildungsroman.

And just to complicate matters that much more, genre can sometimes take into account not only the type of plot but the form the novelist uses to convey that plot. A story might be told in a series of letters (this is called an epistolary form), in a sequence of journal entries, or in a combination of forms ( Frankenstein is actually told as a journal included within a letter).

These matters of form also introduce questions of point of view, that is, who is telling the story and what do they or don’t they know. Is the tale told by an omniscient or all-knowing narrator who doesn’t interact in the events, or is it presented by one of the characters within the story? Can the reader trust that person to give an objective account, or does that narrator color the story with his or her own biases and interests?

Character refers to the qualities assigned to the individual figures in the plot. Consider why the author assigns certain qualities to a character or characters and how any such qualities might relate to your topic. For example, a discussion of Victor Frankenstein’s education might take into account aspects of his character that appear to be developed (or underdeveloped) by the particular kind of education he undertakes. Victor tends to be ambitious, even compulsive about his studies, and I might be able to argue that his tendency to be extravagant leads him to devote his own education to writers who asserted grand, if questionable, conclusions.

Setting is the environment in which all of the actions take place. What is the time period, the location, the time of day, the season, the weather, the type of room or building? What is the general mood, and who is present? All of these elements can reflect on the story’s events, and though the setting of a story tends to be less conspicuous than plot and character, setting still colors everything that's said and done within its context. If Victor Frankenstein does all of his experiments in "a solitary chamber, or rather a cell, at the top of the house, and separated from all the other apartments by a staircase" (53) we might conclude that there is something anti-social, isolated, and stale, maybe even unnatural about his project and his way of learning.

Obviously, if you consider all of these elements, you'll probably have too much evidence to fit effectively into one paper. Your goal is merely to consider each of these aspects of fiction and include only those that are most relevant to your topic and most interesting to your reader. A good interpretive paper does not need to cover all elements of the story — plot, genre, narrative form, character, and setting. In fact, a paper that did try to say something about all of these elements would be unfocused. You might find that most of your topic could be supported by a consideration of character alone. That's fine. For my Frankenstein paper, I'm finding that my evidence largely has to do with the setting, evidence that could lead to some interesting conclusions that my reader probably hasn't recognized on his or her own.

6. Select your evidence

Once you've made your expanded list of evidence, decide which supporting details are the strongest. First, select the facts which bear the closest relation to your thesis statement. Second, choose the pieces of evidence you'll be able to say the most about. Readers tend to be more dazzled with your interpretations of evidence than with a lot of quotes from the book. It would be useful to refer to Victor Frankenstein's youthful reading in alchemy, but my reader will be more impressed by some analysis of how the writings of the alchemists—who pursued magical principles of chemistry and physics—reflect the ambition of his own goals. Select the details that will allow you to show off your own reasoning skills and allow you to help the reader see the story in a way he or she may not have seen it before.

7. Refine your thesis

Now it's time to go back to your working thesis and refine it so that it reflects your new understanding of your topic. This step and the previous step (selecting evidence) are actually best done at the same time, since selecting your evidence and defining the focus of your paper depend upon each other. Don't forget to consider the scope of your project: how long is the paper supposed to be, and what can you reasonably cover in a paper of that length? In rethinking the issue of education in Frankenstein , I realize that I can narrow my topic in a number of ways: I could focus on education and culture (Victor's education abroad), education in the sciences as opposed to the humanities (the monster reads Milton, Goethe, and Plutarch), or differences in learning environments (e.g. independent study, university study, family reading). Since I think I found some interesting evidence in the settings that I can interpret in a way that will get my reader's attention, I'll take this last option and refine my working thesis about Victor's faulty education to something like this: "Victor Frankenstein’s education in unnaturally isolated environments fosters his tragic ambition."

8. Organize your evidence

Once you have a clear thesis you can go back to your list of selected evidence and group all the similar details together. The ideas that tie these clusters of evidence together can then become the claims that you'll make in your paper. As you begin thinking about what claims you can make (i.e. what kinds of conclusion you can come to) keep in mind that they should not only relate to all the evidence but also clearly support your thesis. Once you're satisfied with the way you've grouped your evidence and with the way that your claims relate to your thesis, you can begin to consider the most logical way to organize each of those claims. To support my thesis about Frankenstein , I've decided to group my evidence chronologically. I'll start with Victor's education at home, then discuss his learning at the University, and finally address his own experiments. This arrangement will let me show that Victor was always prone to isolation in his education and that this tendency gets stronger as he becomes more ambitious.

There are certainly other organizational options that might work better depending on the type of points I want to stress. I could organize a discussion of education by the various forms of education found in the novel (for example, education through reading, through classrooms, and through observation), by specific characters (education for Victor, the monster, and Victor's bride, Elizabeth), or by the effects of various types of education (those with harmful, beneficial, or neutral effects).

9. Interpret your evidence

Avoid the temptation to load your paper with evidence from your story. Each time you use a specific reference to your story, be sure to explain the significance of that evidence in your own words. To get your readers' interest, you need to draw their attention to elements of the story that they wouldn't necessarily notice or understand on their own. If you're quoting passages without interpreting them, you're not demonstrating your reasoning skills or helping the reader. In most cases, interpreting your evidence merely involves putting into your paper what is already in your head. Remember that we, as readers, are lazy — all of us. We don't want to have to figure out a writer's reasoning for ourselves; we want all the thinking to be done for us in the paper.

General Hints

The previous nine steps are intended to give you a sense of the tasks usually involved in writing a good interpretive paper. What follows are just some additional hints that might help you find an interesting topic and maybe even make the process a little more enjoyable.

1. Make your thesis relevant to your readers

You'll be able to keep your readers' attention more easily if you pick a topic that relates to daily experience. Avoid writing a paper that identifies a pattern in a story but doesn’t quite explain why that pattern leads to an interesting interpretation. Identifying the biblical references in Frankenstein might provide a good start to a paper—Mary Shelley does use a lot of biblical allusions—but a good paper must also tell the reader why those references are meaningful. So what makes an interesting paper topic? Simply put, it has to address issues that we can use in our own lives. Your thesis should be able to answer the brutal question "So what?" Does your paper tell your reader something relevant about the context of the story you're interpreting or about the human condition?

Some categories, like race, gender, and social class, are dependable sources of interest. This is not to say that all good papers necessarily deal with one of these issues. My thesis on education in Frankenstein does not. But a lot of readers would probably be less interested in reading a paper that traces the instances of water imagery than in reading a paper that compares male or female stereotypes used in a story or that takes a close look at relationships between characters of different races. Again, don't feel compelled to write on race, gender, or class. The main idea is that you ask yourself whether the topic you've selected connects with a major human concern, and there are a lot of options here (for example, issues that relate to economics, family dynamics, education, religion, law, politics, sexuality, history, and psychology, among others).

Also, don't assume that as long as you address one of these issues, your paper will be interesting. As mentioned in step 2, you need to address these big topics in a complex way. Doing this requires that you don’t go into a topic with a preconceived notion of what you’ll find. Be prepared to challenge your own ideas about what gender, race, or class mean in a particular text.

2. Select a topic of interest to you

Though you may feel like you have to select a topic that sounds like something your instructor would be interested in, don't overlook the fact that you'll be more invested in your paper and probably get more out of it if you make the topic something pertinent to yourself. Pick a topic that might allow you to learn about yourself and what you find important.

Of course, your topic can't entirely be of your choosing. We're always at the mercy of the evidence that's available to us. For example, your interest may really be in political issues, but if you're reading Frankenstein , you might face some difficulties in finding enough evidence to make a good paper on that kind of topic. If, on the other hand, you're interested in ethics, philosophy, science, psychology, religion, or even geography, you'll probably have more than enough to write about and find yourself in the good position of having to select only the best pieces of evidence.

3. Make your thesis specific

The effort to be more specific almost always leads to a thesis that will get your reader's attention, and it also separates you from the crowd as someone who challenges ideas and looks into topics more deeply. A paper about education in general in Frankenstein will probably not get my reader's attention as much as a more specific topic about the impact of the learning environment on the main character. My readers may have already thought to some extent about ideas of education in the novel, if they have read it, but the chance that they have thought through something more specific like the educational environment is slim.

Contributors and Attributions

Adapted from Literature (Fiction) . Provided by: UNC College of Arts and Sciences Writing Center. License: CC BY-NC-ND .

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article