- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

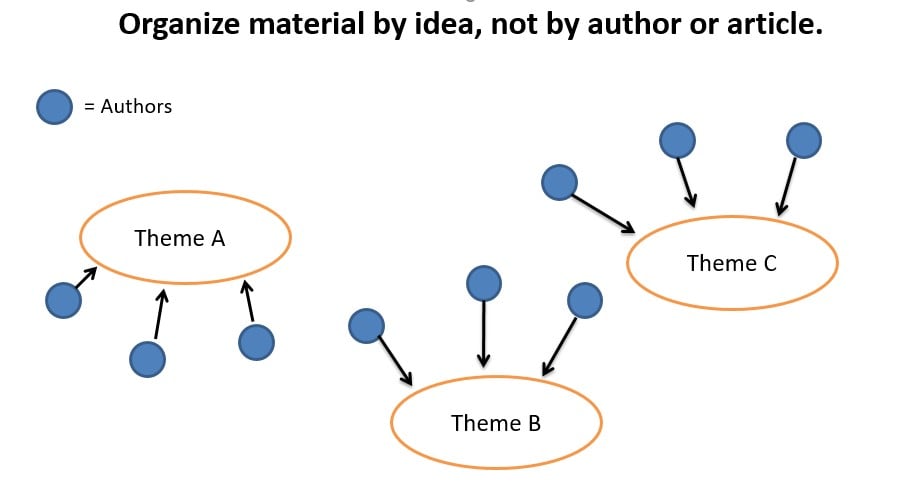

Synthesis Visualization

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

Approaches to synthesis.

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 10, 2024 4:46 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

Literature Syntheis 101

How To Synthesise The Existing Research (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | August 2023

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing a literature review is that they err on the side of describing the existing literature rather than providing a critical synthesis of it. In this post, we’ll unpack what exactly synthesis means and show you how to craft a strong literature synthesis using practical examples.

This post is based on our popular online course, Literature Review Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the full process of developing a literature review, step by step. If it’s your first time writing a literature review, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Literature Synthesis

- What exactly does “synthesis” mean?

- Aspect 1: Agreement

- Aspect 2: Disagreement

- Aspect 3: Key theories

- Aspect 4: Contexts

- Aspect 5: Methodologies

- Bringing it all together

What does “synthesis” actually mean?

As a starting point, let’s quickly define what exactly we mean when we use the term “synthesis” within the context of a literature review.

Simply put, literature synthesis means going beyond just describing what everyone has said and found. Instead, synthesis is about bringing together all the information from various sources to present a cohesive assessment of the current state of knowledge in relation to your study’s research aims and questions .

Put another way, a good synthesis tells the reader exactly where the current research is “at” in terms of the topic you’re interested in – specifically, what’s known , what’s not , and where there’s a need for more research .

So, how do you go about doing this?

Well, there’s no “one right way” when it comes to literature synthesis, but we’ve found that it’s particularly useful to ask yourself five key questions when you’re working on your literature review. Having done so, you can then address them more articulately within your actual write up. So, let’s take a look at each of these questions.

1. Points Of Agreement

The first question that you need to ask yourself is: “Overall, what things seem to be agreed upon by the vast majority of the literature?”

For example, if your research aim is to identify which factors contribute toward job satisfaction, you’ll need to identify which factors are broadly agreed upon and “settled” within the literature. Naturally, there may at times be some lone contrarian that has a radical viewpoint , but, provided that the vast majority of researchers are in agreement, you can put these random outliers to the side. That is, of course, unless your research aims to explore a contrarian viewpoint and there’s a clear justification for doing so.

Identifying what’s broadly agreed upon is an essential starting point for synthesising the literature, because you generally don’t want (or need) to reinvent the wheel or run down a road investigating something that is already well established . So, addressing this question first lays a foundation of “settled” knowledge.

Need a helping hand?

2. Points Of Disagreement

Related to the previous point, but on the other end of the spectrum, is the equally important question: “Where do the disagreements lie?” .

In other words, which things are not well agreed upon by current researchers? It’s important to clarify here that by disagreement, we don’t mean that researchers are (necessarily) fighting over it – just that there are relatively mixed findings within the empirical research , with no firm consensus amongst researchers.

This is a really important question to address as these “disagreements” will often set the stage for the research gap(s). In other words, they provide clues regarding potential opportunities for further research, which your study can then (hopefully) contribute toward filling. If you’re not familiar with the concept of a research gap, be sure to check out our explainer video covering exactly that .

3. Key Theories

The next question you need to ask yourself is: “Which key theories seem to be coming up repeatedly?” .

Within most research spaces, you’ll find that you keep running into a handful of key theories that are referred to over and over again. Apart from identifying these theories, you’ll also need to think about how they’re connected to each other. Specifically, you need to ask yourself:

- Are they all covering the same ground or do they have different focal points or underlying assumptions ?

- Do some of them feed into each other and if so, is there an opportunity to integrate them into a more cohesive theory?

- Do some of them pull in different directions ? If so, why might this be?

- Do all of the theories define the key concepts and variables in the same way, or is there some disconnect? If so, what’s the impact of this ?

Simply put, you’ll need to pay careful attention to the key theories in your research area, as they will need to feature within your theoretical framework , which will form a critical component within your final literature review. This will set the foundation for your entire study, so it’s essential that you be critical in this area of your literature synthesis.

If this sounds a bit fluffy, don’t worry. We deep dive into the theoretical framework (as well as the conceptual framework) and look at practical examples in Literature Review Bootcamp . If you’d like to learn more, take advantage of our limited-time offer to get 60% off the standard price.

4. Contexts

The next question that you need to address in your literature synthesis is an important one, and that is: “Which contexts have (and have not) been covered by the existing research?” .

For example, sticking with our earlier hypothetical topic (factors that impact job satisfaction), you may find that most of the research has focused on white-collar , management-level staff within a primarily Western context, but little has been done on blue-collar workers in an Eastern context. Given the significant socio-cultural differences between these two groups, this is an important observation, as it could present a contextual research gap .

In practical terms, this means that you’ll need to carefully assess the context of each piece of literature that you’re engaging with, especially the empirical research (i.e., studies that have collected and analysed real-world data). Ideally, you should keep notes regarding the context of each study in some sort of catalogue or sheet, so that you can easily make sense of this before you start the writing phase. If you’d like, our free literature catalogue worksheet is a great tool for this task.

5. Methodological Approaches

Last but certainly not least, you need to ask yourself the question: “What types of research methodologies have (and haven’t) been used?”

For example, you might find that most studies have approached the topic using qualitative methods such as interviews and thematic analysis. Alternatively, you might find that most studies have used quantitative methods such as online surveys and statistical analysis.

But why does this matter?

Well, it can run in one of two potential directions . If you find that the vast majority of studies use a specific methodological approach, this could provide you with a firm foundation on which to base your own study’s methodology . In other words, you can use the methodologies of similar studies to inform (and justify) your own study’s research design .

On the other hand, you might argue that the lack of diverse methodological approaches presents a research gap , and therefore your study could contribute toward filling that gap by taking a different approach. For example, taking a qualitative approach to a research area that is typically approached quantitatively. Of course, if you’re going to go against the methodological grain, you’ll need to provide a strong justification for why your proposed approach makes sense. Nevertheless, it is something worth at least considering.

Regardless of which route you opt for, you need to pay careful attention to the methodologies used in the relevant studies and provide at least some discussion about this in your write-up. Again, it’s useful to keep track of this on some sort of spreadsheet or catalogue as you digest each article, so consider grabbing a copy of our free literature catalogue if you don’t have anything in place.

Bringing It All Together

Alright, so we’ve looked at five important questions that you need to ask (and answer) to help you develop a strong synthesis within your literature review. To recap, these are:

- Which things are broadly agreed upon within the current research?

- Which things are the subject of disagreement (or at least, present mixed findings)?

- Which theories seem to be central to your research topic and how do they relate or compare to each other?

- Which contexts have (and haven’t) been covered?

- Which methodological approaches are most common?

Importantly, you’re not just asking yourself these questions for the sake of asking them – they’re not just a reflection exercise. You need to weave your answers to them into your actual literature review when you write it up. How exactly you do this will vary from project to project depending on the structure you opt for, but you’ll still need to address them within your literature review, whichever route you go.

The best approach is to spend some time actually writing out your answers to these questions, as opposed to just thinking about them in your head. Putting your thoughts onto paper really helps you flesh out your thinking . As you do this, don’t just write down the answers – instead, think about what they mean in terms of the research gap you’ll present , as well as the methodological approach you’ll take . Your literature synthesis needs to lay the groundwork for these two things, so it’s essential that you link all of it together in your mind, and of course, on paper.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

excellent , thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Find This link opens in a new window

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

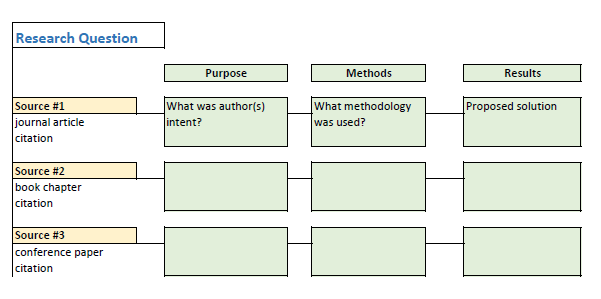

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 10:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

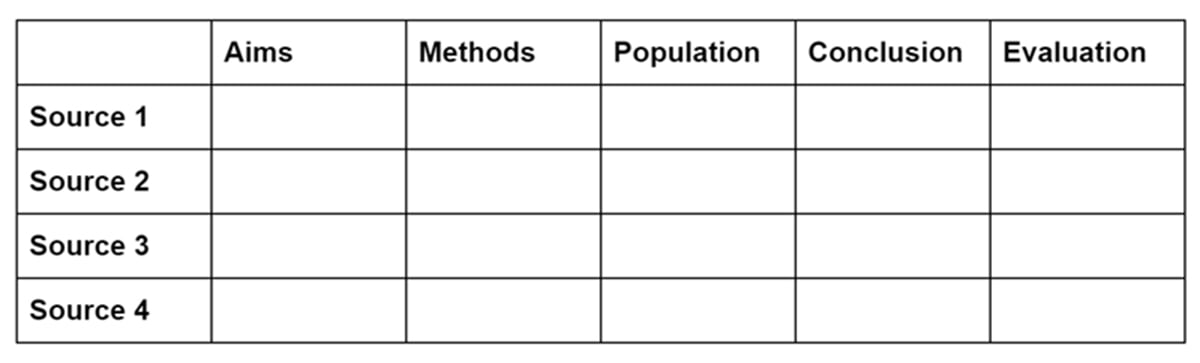

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

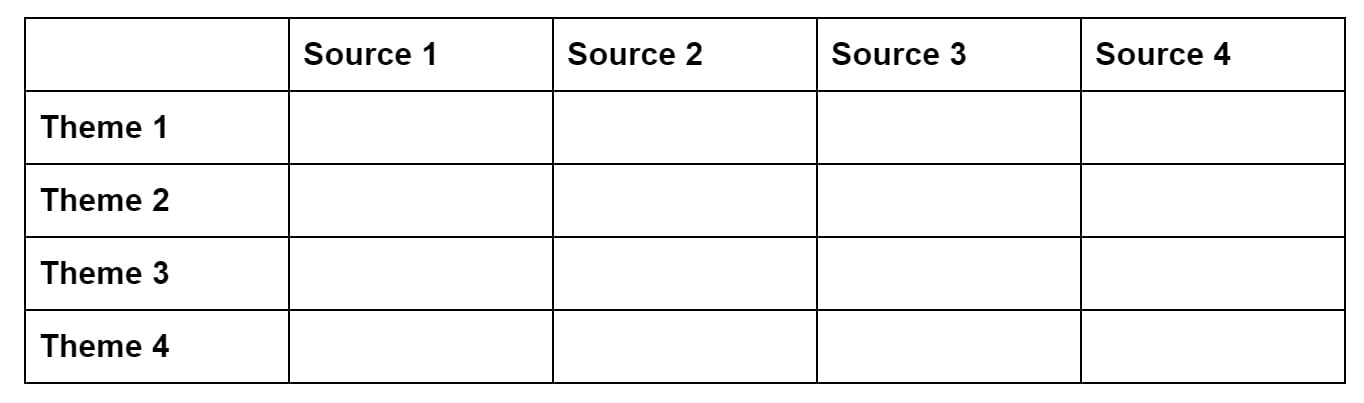

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Literature Reviews

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- Getting started

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

How to synthesize

Approaches to synthesis.

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

In the synthesis step of a literature review, researchers analyze and integrate information from selected sources to identify patterns and themes. This involves critically evaluating findings, recognizing commonalities, and constructing a cohesive narrative that contributes to the understanding of the research topic.

Here are some examples of how to approach synthesizing the literature:

💡 By themes or concepts

🕘 Historically or chronologically

📊 By methodology

These organizational approaches can also be used when writing your review. It can be beneficial to begin organizing your references by these approaches in your citation manager by using folders, groups, or collections.

Create a synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix allows you to visually organize your literature.

Topic: ______________________________________________

Topic: Chemical exposure to workers in nail salons

- << Previous: 4. Organize your results

- Next: 6. Write the review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2024 12:40 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/lit-reviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

Library Guides

Literature reviews: synthesis.

- Criticality

Synthesise Information

So, how can you create paragraphs within your literature review that demonstrates your knowledge of the scholarship that has been done in your field of study?

You will need to present a synthesis of the texts you read.

Doug Specht, Senior Lecturer at the Westminster School of Media and Communication, explains synthesis for us in the following video:

Synthesising Texts

What is synthesis?

Synthesis is an important element of academic writing, demonstrating comprehension, analysis, evaluation and original creation.

With synthesis you extract content from different sources to create an original text. While paraphrase and summary maintain the structure of the given source(s), with synthesis you create a new structure.

The sources will provide different perspectives and evidence on a topic. They will be put together when agreeing, contrasted when disagreeing. The sources must be referenced.

Perfect your synthesis by showing the flow of your reasoning, expressing critical evaluation of the sources and drawing conclusions.

When you synthesise think of "using strategic thinking to resolve a problem requiring the integration of diverse pieces of information around a structuring theme" (Mateos and Sole 2009, p448).

Synthesis is a complex activity, which requires a high degree of comprehension and active engagement with the subject. As you progress in higher education, so increase the expectations on your abilities to synthesise.

How to synthesise in a literature review:

Identify themes/issues you'd like to discuss in the literature review. Think of an outline.

Read the literature and identify these themes/issues.

Critically analyse the texts asking: how does the text I'm reading relate to the other texts I've read on the same topic? Is it in agreement? Does it differ in its perspective? Is it stronger or weaker? How does it differ (could be scope, methods, year of publication etc.). Draw your conclusions on the state of the literature on the topic.

Start writing your literature review, structuring it according to the outline you planned.

Put together sources stating the same point; contrast sources presenting counter-arguments or different points.

Present your critical analysis.

Always provide the references.

The best synthesis requires a "recursive process" whereby you read the source texts, identify relevant parts, take notes, produce drafts, re-read the source texts, revise your text, re-write... (Mateos and Sole, 2009).

What is good synthesis?

The quality of your synthesis can be assessed considering the following (Mateos and Sole, 2009, p439):

Integration and connection of the information from the source texts around a structuring theme.

Selection of ideas necessary for producing the synthesis.

Appropriateness of the interpretation.

Elaboration of the content.

Example of Synthesis

Original texts (fictitious):

Synthesis:

Animal experimentation is a subject of heated debate. Some argue that painful experiments should be banned. Indeed it has been demonstrated that such experiments make animals suffer physically and psychologically (Chowdhury 2012; Panatta and Hudson 2016). On the other hand, it has been argued that animal experimentation can save human lives and reduce harm on humans (Smith 2008). This argument is only valid for toxicological testing, not for tests that, for example, merely improve the efficacy of a cosmetic (Turner 2015). It can be suggested that animal experimentation should be regulated to only allow toxicological risk assessment, and the suffering to the animals should be minimised.

Bibliography

Mateos, M. and Sole, I. (2009). Synthesising Information from various texts: A Study of Procedures and Products at Different Educational Levels. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24 (4), 435-451. Available from https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03178760 [Accessed 29 June 2021].

- << Previous: Structure

- Next: Criticality >>

- Last Updated: Nov 18, 2023 10:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/literature-reviews

CONNECT WITH US

Literature Review How To

- Things To Consider

- Synthesizing Sources

- Video Tutorials

- Books On Literature Reviews

What is Synthesis

What is Synthesis? Synthesis writing is a form of analysis related to comparison and contrast, classification and division. On a basic level, synthesis requires the writer to pull together two or more summaries, looking for themes in each text. In synthesis, you search for the links between various materials in order to make your point. Most advanced academic writing, including literature reviews, relies heavily on synthesis. (Temple University Writing Center)

How To Synthesize Sources in a Literature Review

Literature reviews synthesize large amounts of information and present it in a coherent, organized fashion. In a literature review you will be combining material from several texts to create a new text – your literature review.

You will use common points among the sources you have gathered to help you synthesize the material. This will help ensure that your literature review is organized by subtopic, not by source. This means various authors' names can appear and reappear throughout the literature review, and each paragraph will mention several different authors.

When you shift from writing summaries of the content of a source to synthesizing content from sources, there is a number things you must keep in mind:

- Look for specific connections and or links between your sources and how those relate to your thesis or question.

- When writing and organizing your literature review be aware that your readers need to understand how and why the information from the different sources overlap.

- Organize your literature review by the themes you find within your sources or themes you have identified.

- << Previous: Things To Consider

- Next: Video Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Nov 30, 2018 4:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.csun.edu/literature-review

Report ADA Problems with Library Services and Resources

A Guide to Evidence Synthesis: What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Meet Our Team

- Our Published Reviews and Protocols

- What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Types of Evidence Synthesis

- Evidence Synthesis Across Disciplines

- Finding and Appraising Existing Systematic Reviews

- 0. Develop a Protocol

- 1. Draft your Research Question

- 2. Select Databases

- 3. Select Grey Literature Sources

- 4. Write a Search Strategy

- 5. Register a Protocol

- 6. Translate Search Strategies

- 7. Citation Management

- 8. Article Screening

- 9. Risk of Bias Assessment

- 10. Data Extraction

- 11. Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Evidence Synthesis Institute for Librarians

- Open Access Evidence Synthesis Resources

What are Evidence Syntheses?

What are evidence syntheses.

According to the Royal Society, 'evidence synthesis' refers to the process of bringing together information from a range of sources and disciplines to inform debates and decisions on specific issues. They generally include a methodical and comprehensive literature synthesis focused on a well-formulated research question. Their aim is to identify and synthesize all of the scholarly research on a particular topic, including both published and unpublished studies. Evidence syntheses are conducted in an unbiased, reproducible way to provide evidence for practice and policy-making, as well as to identify gaps in the research. Evidence syntheses may also include a meta-analysis, a more quantitative process of synthesizing and visualizing data retrieved from various studies.

Evidence syntheses are much more time-intensive than traditional literature reviews and require a multi-person research team. See this PredicTER tool to get a sense of a systematic review timeline (one type of evidence synthesis). Before embarking on an evidence synthesis, it's important to clearly identify your reasons for conducting one. For a list of types of evidence synthesis projects, see the next tab.

How Does a Traditional Literature Review Differ From an Evidence Synthesis?

How does a systematic review differ from a traditional literature review.

One commonly used form of evidence synthesis is a systematic review. This table compares a traditional literature review with a systematic review.

Video: Reproducibility and transparent methods (Video 3:25)

Reporting Standards

There are some reporting standards for evidence syntheses. These can serve as guidelines for protocol and manuscript preparation and journals may require that these standards are followed for the review type that is being employed (e.g. systematic review, scoping review, etc).

- PRISMA checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

- PRISMA-P Standards An updated version of the original PRISMA standards for protocol development.

- PRISMA - ScR Reporting guidelines for scoping reviews and evidence maps

- PRISMA-IPD Standards Extension of the original PRISMA standards for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of individual participant data.

- EQUATOR Network The EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research) Network is an international initiative that seeks to improve the reliability and value of published health research literature by promoting transparent and accurate reporting and wider use of robust reporting guidelines. They provide a list of various standards for reporting in systematic reviews.

Video: Guidelines and reporting standards

PRISMA Flow Diagram

The PRISMA flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of an evidence synthesis. It maps the search (number of records identified), screening (number of records included and excluded), and selection (reasons for exclusion). Many evidence syntheses include a PRISMA flow diagram in the published manuscript.

See below for resources to help you generate your own PRISMA flow diagram.

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Tool

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Word Template

- << Previous: Our Published Reviews and Protocols

- Next: Types of Evidence Synthesis >>

- Last Updated: Apr 22, 2024 2:24 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evidence-synthesis

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Synthesizing Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you look for areas where your sources agree or disagree and try to draw broader conclusions about your topic based on what your sources say, you are engaging in synthesis. Writing a research paper usually requires synthesizing the available sources in order to provide new insight or a different perspective into your particular topic (as opposed to simply restating what each individual source says about your research topic).

Note that synthesizing is not the same as summarizing.

- A summary restates the information in one or more sources without providing new insight or reaching new conclusions.

- A synthesis draws on multiple sources to reach a broader conclusion.

There are two types of syntheses: explanatory syntheses and argumentative syntheses . Explanatory syntheses seek to bring sources together to explain a perspective and the reasoning behind it. Argumentative syntheses seek to bring sources together to make an argument. Both types of synthesis involve looking for relationships between sources and drawing conclusions.

In order to successfully synthesize your sources, you might begin by grouping your sources by topic and looking for connections. For example, if you were researching the pros and cons of encouraging healthy eating in children, you would want to separate your sources to find which ones agree with each other and which ones disagree.

After you have a good idea of what your sources are saying, you want to construct your body paragraphs in a way that acknowledges different sources and highlights where you can draw new conclusions.

As you continue synthesizing, here are a few points to remember:

- Don’t force a relationship between sources if there isn’t one. Not all of your sources have to complement one another.

- Do your best to highlight the relationships between sources in very clear ways.

- Don’t ignore any outliers in your research. It’s important to take note of every perspective (even those that disagree with your broader conclusions).

Example Syntheses

Below are two examples of synthesis: one where synthesis is NOT utilized well, and one where it is.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for KidsHealth , encourages parents to be role models for their children by not dieting or vocalizing concerns about their body image. The first popular diet began in 1863. William Banting named it the “Banting” diet after himself, and it consisted of eating fruits, vegetables, meat, and dry wine. Despite the fact that dieting has been around for over a hundred and fifty years, parents should not diet because it hinders children’s understanding of healthy eating.

In this sample paragraph, the paragraph begins with one idea then drastically shifts to another. Rather than comparing the sources, the author simply describes their content. This leads the paragraph to veer in an different direction at the end, and it prevents the paragraph from expressing any strong arguments or conclusions.

An example of a stronger synthesis can be found below.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Different scientists and educators have different strategies for promoting a well-rounded diet while still encouraging body positivity in children. David R. Just and Joseph Price suggest in their article “Using Incentives to Encourage Healthy Eating in Children” that children are more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they are given a reward (855-856). Similarly, Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for Kids Health , encourages parents to be role models for their children. She states that “parents who are always dieting or complaining about their bodies may foster these same negative feelings in their kids. Try to keep a positive approach about food” (Ben-Joseph). Martha J. Nepper and Weiwen Chai support Ben-Joseph’s suggestions in their article “Parents’ Barriers and Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating among School-age Children.” Nepper and Chai note, “Parents felt that patience, consistency, educating themselves on proper nutrition, and having more healthy foods available in the home were important strategies when developing healthy eating habits for their children.” By following some of these ideas, parents can help their children develop healthy eating habits while still maintaining body positivity.

In this example, the author puts different sources in conversation with one another. Rather than simply describing the content of the sources in order, the author uses transitions (like "similarly") and makes the relationship between the sources evident.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- AIMS Public Health

- v.3(1); 2016

What Synthesis Methodology Should I Use? A Review and Analysis of Approaches to Research Synthesis

Kara schick-makaroff.

1 Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Marjorie MacDonald

2 School of Nursing, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

Marilyn Plummer

3 College of Nursing, Camosun College, Victoria, BC, Canada

Judy Burgess

4 Student Services, University Health Services, Victoria, BC, Canada

Wendy Neander

Associated data, additional file 1.

When we began this process, we were doctoral students and a faculty member in a research methods course. As students, we were facing a review of the literature for our dissertations. We encountered several different ways of conducting a review but were unable to locate any resources that synthesized all of the various synthesis methodologies. Our purpose is to present a comprehensive overview and assessment of the main approaches to research synthesis. We use ‘research synthesis’ as a broad overarching term to describe various approaches to combining, integrating, and synthesizing research findings.

We conducted an integrative review of the literature to explore the historical, contextual, and evolving nature of research synthesis. We searched five databases, reviewed websites of key organizations, hand-searched several journals, and examined relevant texts from the reference lists of the documents we had already obtained.

We identified four broad categories of research synthesis methodology including conventional, quantitative, qualitative, and emerging syntheses. Each of the broad categories was compared to the others on the following: key characteristics, purpose, method, product, context, underlying assumptions, unit of analysis, strengths and limitations, and when to use each approach.

Conclusions

The current state of research synthesis reflects significant advancements in emerging synthesis studies that integrate diverse data types and sources. New approaches to research synthesis provide a much broader range of review alternatives available to health and social science students and researchers.

1. Introduction

Since the turn of the century, public health emergencies have been identified worldwide, particularly related to infectious diseases. For example, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Canada in 2002-2003, the recent Ebola epidemic in Africa, and the ongoing HIV/AIDs pandemic are global health concerns. There have also been dramatic increases in the prevalence of chronic diseases around the world [1] – [3] . These epidemiological challenges have raised concerns about the ability of health systems worldwide to address these crises. As a result, public health systems reform has been initiated in a number of countries. In Canada, as in other countries, the role of evidence to support public health reform and improve population health has been given high priority. Yet, there continues to be a significant gap between the production of evidence through research and its application in practice [4] – [5] . One strategy to address this gap has been the development of new research synthesis methodologies to deal with the time-sensitive and wide ranging evidence needs of policy makers and practitioners in all areas of health care, including public health.

As doctoral nursing students facing a review of the literature for our dissertations, and as a faculty member teaching a research methods course, we encountered several ways of conducting a research synthesis but found no comprehensive resources that discussed, compared, and contrasted various synthesis methodologies on their purposes, processes, strengths and limitations. To complicate matters, writers use terms interchangeably or use different terms to mean the same thing, and the literature is often contradictory about various approaches. Some texts [6] , [7] – [9] did provide a preliminary understanding about how research synthesis had been taken up in nursing, but these did not meet our requirements. Thus, in this article we address the need for a comprehensive overview of research synthesis methodologies to guide public health, health care, and social science researchers and practitioners.

Research synthesis is relatively new in public health but has a long history in other fields dating back to the late 1800s. Research synthesis, a research process in its own right [10] , has become more prominent in the wake of the evidence-based movement of the 1990s. Research syntheses have found their advocates and detractors in all disciplines, with challenges to the processes of systematic review and meta-analysis, in particular, being raised by critics of evidence-based healthcare [11] – [13] .

Our purpose was to conduct an integrative review of the literature to explore the historical, contextual, and evolving nature of research synthesis [14] – [15] . We synthesize and critique the main approaches to research synthesis that are relevant for public health, health care, and social scientists. Research synthesis is the overarching term we use to describe approaches to combining, aggregating, integrating, and synthesizing primary research findings. Each synthesis methodology draws on different types of findings depending on the purpose and product of the chosen synthesis (see Additional File 1 ).

3. Method of Review

Based on our current knowledge of the literature, we identified these approaches to include in our review: systematic review, meta-analysis, qualitative meta-synthesis, meta-narrative synthesis, scoping review, rapid review, realist synthesis, concept analysis, literature review, and integrative review. Our first step was to divide the synthesis types among the research team. Each member did a preliminary search to identify key texts. The team then met to develop search terms and a framework to guide the review.

Over the period of 2008 to 2012 we extensively searched the literature, updating our search at several time points, not restricting our search by date. The dates of texts reviewed range from 1967 to 2015. We used the terms above combined with the term “method* (e.g., “realist synthesis” and “method*) in the database Health Source: Academic Edition (includes Medline and CINAHL). This search yielded very few texts on some methodologies and many on others. We realized that many documents on research synthesis had not been picked up in the search. Therefore, we also searched Google Scholar, PubMed, ERIC, and Social Science Index, as well as the websites of key organizations such as the Joanna Briggs Institute, the University of York Centre for Evidence-Based Nursing, and the Cochrane Collaboration database. We hand searched several nursing, social science, public health and health policy journals. Finally, we traced relevant documents from the references in obtained texts.

We included works that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) published in English; (2) discussed the history of research synthesis; (3) explicitly described the approach and specific methods; or (4) identified issues, challenges, strengths and limitations of the particular methodology. We excluded research reports that resulted from the use of particular synthesis methodologies unless they also included criteria 2, 3, or 4 above.

Based on our search, we identified additional types of research synthesis (e.g., meta-interpretation, best evidence synthesis, critical interpretive synthesis, meta-summary, grounded formal theory). Still, we missed some important developments in meta-analysis, for example, identified by the journal's reviewers that have now been discussed briefly in the paper. The final set of 197 texts included in our review comprised theoretical, empirical, and conceptual papers, books, editorials and commentaries, and policy documents.

In our preliminary review of key texts, the team inductively developed a framework of the important elements of each method for comparison. In the next phase, each text was read carefully, and data for these elements were extracted into a table for comparison on the points of: key characteristics, purpose, methods, and product; see Additional File 1 ). Once the data were grouped and extracted, we synthesized across categories based on the following additional points of comparison: complexity of the process, degree of systematization, consideration of context, underlying assumptions, unit of analysis, and when to use each approach. In our results, we discuss our comparison of the various synthesis approaches on the elements above. Drawing only on documents for the review, ethics approval was not required.

We identified four broad categories of research synthesis methodology: Conventional, quantitative, qualitative, and emerging syntheses. From our dataset of 197 texts, we had 14 texts on conventional synthesis, 64 on quantitative synthesis, 78 on qualitative synthesis, and 41 on emerging syntheses. Table 1 provides an overview of the four types of research synthesis, definitions, types of data used, products, and examples of the methodology.

Although we group these types of synthesis into four broad categories on the basis of similarities, each type within a category has unique characteristics, which may differ from the overall group similarities. Each could be explored in greater depth to tease out their unique characteristics, but detailed comparison is beyond the scope of this article.

Additional File 1 presents one or more selected types of synthesis that represent the broad category but is not an exhaustive presentation of all types within each category. It provides more depth for specific examples from each category of synthesis on the characteristics, purpose, methods, and products than is found in Table 1 .

4.1. Key Characteristics

4.1.1. what is it.

Here we draw on two types of categorization. First, we utilize Dixon Woods et al.'s [49] classification of research syntheses as being either integrative or interpretive . (Please note that integrative syntheses are not the same as an integrative review as defined in Additional File 1 .) Second, we use Popay's [80] enhancement and epistemological models .

The defining characteristics of integrative syntheses are that they involve summarizing the data achieved by pooling data [49] . Integrative syntheses include systematic reviews, meta-analyses, as well as scoping and rapid reviews because each of these focus on summarizing data. They also define concepts from the outset (although this may not always be true in scoping or rapid reviews) and deal with a well-specified phenomenon of interest.

Interpretive syntheses are primarily concerned with the development of concepts and theories that integrate concepts [49] . The analysis in interpretive synthesis is conceptual both in process and outcome, and “the product is not aggregations of data, but theory” [49] , [p.12]. Interpretive syntheses involve induction and interpretation, and are primarily conceptual in process and outcome. Examples include integrative reviews, some systematic reviews, all of the qualitative syntheses, meta-narrative, realist and critical interpretive syntheses. Of note, both quantitative and qualitative studies can be either integrative or interpretive

The second categorization, enhancement versus epistemological , applies to those approaches that use multiple data types and sources [80] . Popay's [80] classification reflects the ways that qualitative data are valued in relation to quantitative data.

In the enhancement model , qualitative data adds something to quantitative analysis. The enhancement model is reflected in systematic reviews and meta-analyses that use some qualitative data to enhance interpretation and explanation. It may also be reflected in some rapid reviews that draw on quantitative data but use some qualitative data.

The epistemological model assumes that quantitative and qualitative data are equal and each has something unique to contribute. All of the other review approaches, except pure quantitative or qualitative syntheses, reflect the epistemological model because they value all data types equally but see them as contributing different understandings.

4.1.2. Data type

By and large, the quantitative approaches (quantitative systematic review and meta-analysis) have typically used purely quantitative data (i.e., expressed in numeric form). More recently, both Cochrane [81] and Campbell [82] collaborations are grappling with the need to, and the process of, integrating qualitative research into a systematic review. The qualitative approaches use qualitative data (i.e., expressed in words). All of the emerging synthesis types, as well as the conventional integrative review, incorporate qualitative and quantitative study designs and data.

4.1.3. Research question

Four types of research questions direct inquiry across the different types of syntheses. The first is a well-developed research question that gives direction to the synthesis (e.g., meta-analysis, systematic review, meta-study, concept analysis, rapid review, realist synthesis). The second begins as a broad general question that evolves and becomes more refined over the course of the synthesis (e.g., meta-ethnography, scoping review, meta-narrative, critical interpretive synthesis). In the third type, the synthesis begins with a phenomenon of interest and the question emerges in the analytic process (e.g., grounded formal theory). Lastly, there is no clear question, but rather a general review purpose (e.g., integrative review). Thus, the requirement for a well-defined question cuts across at least three of the synthesis types (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, and emerging).

4.1.4. Quality appraisal

This is a contested issue within and between the four synthesis categories. There are strong proponents of quality appraisal in the quantitative traditions of systematic review and meta-analysis based on the need for strong studies that will not jeopardize validity of the overall findings. Nonetheless, there is no consensus on pre-defined criteria; many scales exist that vary dramatically in composition. This has methodological implications for the credibility of findings [83] .

Specific methodologies from the conventional, qualitative, and emerging categories support quality appraisal but do so with caveats. In conventional integrative reviews appraisal is recommended, but depends on the sampling frame used in the study [18] . In meta-study, appraisal criteria are explicit but quality criteria are used in different ways depending on the specific requirements of the inquiry [54] . Among the emerging syntheses, meta-narrative review developers support appraisal of a study based on criteria from the research tradition of the primary study [67] , [84] – [85] . Realist synthesis similarly supports the use of high quality evidence, but appraisal checklists are viewed with scepticism and evidence is judged based on relevance to the research question and whether a credible inference may be drawn [69] . Like realist, critical interpretive syntheses do not judge quality using standardized appraisal instruments. They will exclude fatally flawed studies, but there is no consensus on what ‘fatally flawed’ means [49] , [71] . Appraisal is based on relevance to the inquiry, not rigor of the study.

There is no agreement on quality appraisal among qualitative meta-ethnographers with some supporting and others refuting the need for appraisal. [60] , [62] . Opponents of quality appraisal are found among authors of qualitative (grounded formal theory and concept analysis) and emerging syntheses (scoping and rapid reviews) because quality is not deemed relevant to the intention of the synthesis; the studies being reviewed are not effectiveness studies where quality is extremely important. These qualitative synthesis are often reviews of theoretical developments where the concept itself is what is important, or reviews that provide quotations from the raw data so readers can make their own judgements about the relevance and utility of the data. For example, in formal grounded theory, the purpose of theory generation and authenticity of data used to generate the theory is not as important as the conceptual category. Inaccuracies may be corrected in other ways, such as using the constant comparative method, which facilitates development of theoretical concepts that are repeatedly found in the data [86] – [87] . For pragmatic reasons, evidence is not assessed in rapid and scoping reviews, in part to produce a timely product. The issue of quality appraisal is unresolved across the terrain of research synthesis and we consider this further in our discussion.

4.2. Purpose

All research syntheses share a common purpose -- to summarize, synthesize, or integrate research findings from diverse studies. This helps readers stay abreast of the burgeoning literature in a field. Our discussion here is at the level of the four categories of synthesis. Beginning with conventional literature syntheses, the overall purpose is to attend to mature topics for the purpose of re-conceptualization or to new topics requiring preliminary conceptualization [14] . Such syntheses may be helpful to consider contradictory evidence, map shifting trends in the study of a phenomenon, and describe the emergence of research in diverse fields [14] . The purpose here is to set the stage for a study by identifying what has been done, gaps in the literature, important research questions, or to develop a conceptual framework to guide data collection and analysis.

The purpose of quantitative systematic reviews is to combine, aggregate, or integrate empirical research to be able to generalize from a group of studies and determine the limits of generalization [27] . The focus of quantitative systematic reviews has been primarily on aggregating the results of studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions using experimental, quasi-experimental, and more recently, observational designs. Systematic reviews can be done with or without quantitative meta-analysis but a meta-analysis always takes place within the context of a systematic review. Researchers must consider the review's purpose and the nature of their data in undertaking a quantitative synthesis; this will assist in determining the approach.

The purpose of qualitative syntheses is broadly to synthesize complex health experiences, practices, or concepts arising in healthcare environments. There may be various purposes depending on the qualitative methodology. For example, in hermeneutic studies the aim may be holistic explanation or understanding of a phenomenon [42] , which is deepened by integrating the findings from multiple studies. In grounded formal theory, the aim is to produce a conceptual framework or theory expected to be applicable beyond the original study. Although not able to generalize from qualitative research in the statistical sense [88] , qualitative researchers usually do want to say something about the applicability of their synthesis to other settings or phenomena. This notion of ‘theoretical generalization’ has been referred to as ‘transferability’ [89] – [90] and is an important criterion of rigour in qualitative research. It applies equally to the products of a qualitative synthesis in which the synthesis of multiple studies on the same phenomenon strengthens the ability to draw transferable conclusions.

The overarching purpose of emerging syntheses is challenging the more traditional types of syntheses, in part by using data from both quantitative and qualitative studies with diverse designs for analysis. Beyond this, however, each emerging synthesis methodology has a unique purpose. In meta-narrative review, the purpose is to identify different research traditions in the area, synthesize a complex and diverse body of research. Critical interpretive synthesis shares this characteristic. Although a distinctive approach, critical interpretive synthesis utilizes a modification of the analytic strategies of meta-ethnography [61] (e.g., reciprocal translational analysis, refutational synthesis, and lines of argument synthesis) but goes beyond the use of these to bring a critical perspective to bear in challenging the normative or epistemological assumptions in the primary literature [72] – [73] . The unique purpose of a realist synthesis is to amalgamate complex empirical evidence and theoretical understandings within a diverse body of literature to uncover the operative mechanisms and contexts that affect the outcomes of social interventions. In a scoping review, the intention is to find key concepts, examine the range of research in an area, and identify gaps in the literature. The purpose of a rapid review is comparable to that of a scoping review, but done quickly to meet the time-sensitive information needs of policy makers.

4.3. Method

4.3.1. degree of systematization.

There are varying degrees of systematization across the categories of research synthesis. The most systematized are quantitative systematic reviews and meta-analyses. There are clear processes in each with judgments to be made at each step, although there are no agreed upon guidelines for this. The process is inherently subjective despite attempts to develop objective and systematic processes [91] – [92] . Mullen and Ramirez [27] suggest that there is often a false sense of rigour implied by the terms ‘systematic review’ and ‘meta-analysis’ because of their clearly defined procedures.

In comparison with some types of qualitative synthesis, concept analysis is quite procedural. Qualitative meta-synthesis also has defined procedures and is systematic, yet perhaps less so than concept analysis. Qualitative meta-synthesis starts in an unsystematic way but becomes more systematic as it unfolds. Procedures and frameworks exist for some of the emerging types of synthesis [e.g., [50] , [63] , [71] , [93] ] but are not linear, have considerable flexibility, and are often messy with emergent processes [85] . Conventional literature reviews tend not to be as systematic as the other three types. In fact, the lack of systematization in conventional literature synthesis was the reason for the development of more systematic quantitative [17] , [20] and qualitative [45] – [46] , [61] approaches. Some authors in the field [18] have clarified processes for integrative reviews making them more systematic and rigorous, but most conventional syntheses remain relatively unsystematic in comparison with other types.

4.3.2. Complexity of the process

Some synthesis processes are considerably more complex than others. Methodologies with clearly defined steps are arguably less complex than the more flexible and emergent ones. We know that any study encounters challenges and it is rare that a pre-determined research protocol can be followed exactly as intended. Not even the rigorous methods associated with Cochrane [81] systematic reviews and meta-analyses are always implemented exactly as intended. Even when dealing with numbers rather than words, interpretation is always part of the process. Our collective experience suggests that new methodologies (e.g., meta-narrative synthesis and realist synthesis) that integrate different data types and methods are more complex than conventional reviews or the rapid and scoping reviews.

4.4. Product

The products of research syntheses usually take three distinct formats (see Table 1 and Additional File 1 for further details). The first representation is in tables, charts, graphical displays, diagrams and maps as seen in integrative, scoping and rapid reviews, meta-analyses, and critical interpretive syntheses. The second type of synthesis product is the use of mathematical scores. Summary statements of effectiveness are mathematically displayed in meta-analyses (as an effect size), systematic reviews, and rapid reviews (statistical significance).

The third synthesis product may be a theory or theoretical framework. A mid-range theory can be produced from formal grounded theory, meta-study, meta-ethnography, and realist synthesis. Theoretical/conceptual frameworks or conceptual maps may be created in meta-narrative and critical interpretive syntheses, and integrative reviews. Concepts for use within theories are produced in concept analysis. While these three product types span the categories of research synthesis, narrative description and summary is used to present the products resulting from all methodologies.

4.5. Consideration of context

There are diverse ways that context is considered in the four broad categories of synthesis. Context may be considered to the extent that it features within primary studies for the purpose of the review. Context may also be understood as an integral aspect of both the phenomenon under study and the synthesis methodology (e.g., realist synthesis). Quantitative systematic reviews and meta-analyses have typically been conducted on studies using experimental and quasi-experimental designs and more recently observational studies, which control for contextual features to allow for understanding of the ‘true’ effect of the intervention [94] .

More recently, systematic reviews have included covariates or mediating variables (i.e., contextual factors) to help explain variability in the results across studies [27] . Context, however, is usually handled in the narrative discussion of findings rather than in the synthesis itself. This lack of attention to context has been one criticism leveled against systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which restrict the types of research designs that are considered [e.g., [95] ].

When conventional literature reviews incorporate studies that deal with context, there is a place for considering contextual influences on the intervention or phenomenon. Reviews of quantitative experimental studies tend to be devoid of contextual considerations since the original studies are similarly devoid, but context might figure prominently in a literature review that incorporates both quantitative and qualitative studies.

Qualitative syntheses have been conducted on the contextual features of a particular phenomenon [33] . Paterson et al. [54] advise researchers to attend to how context may have influenced the findings of particular primary studies. In qualitative analysis, contextual features may form categories by which the data can be compared and contrasted to facilitate interpretation. Because qualitative research is often conducted to understand a phenomenon as a whole, context may be a focus, although this varies with the qualitative methodology. At the same time, the findings in a qualitative synthesis are abstracted from the original reports and taken to a higher level of conceptualization, thus removing them from the original context.

Meta-narrative synthesis [67] , [84] , because it draws on diverse research traditions and methodologies, may incorporate context into the analysis and findings. There is not, however, an explicit step in the process that directs the analyst to consider context. Generally, the research question guiding the synthesis is an important factor in whether context will be a focus.

More recent iterations of concept analysis [47] , [96] – [97] explicitly consider context reflecting the assumption that a concept's meaning is determined by its context. Morse [47] points out, however, that Wilson's [98] approach to concept analysis, and those based on Wilson [e.g., [45] ], identify attributes that are devoid of context, while Rodgers' [96] , [99] evolutionary method considers context (e.g., antecedents, consequences, and relationships to other concepts) in concept development.

Realist synthesis [69] considers context as integral to the study. It draws on a critical realist logic of inquiry grounded in the work of Bhaskar [100] , who argues that empirical co-occurrence of events is insufficient for inferring causation. One must identify generative mechanisms whose properties are causal and, depending on the situation, may nor may not be activated [94] . Context interacts with program/intervention elements and thus cannot be differentiated from the phenomenon [69] . This approach synthesizes evidence on generative mechanisms and analyzes contextual features that activate them; the result feeds back into the context. The focus is on what works, for whom, under what conditions, why and how [68] .

4.6. Underlying Philosophical and Theoretical Assumptions

When we began our review, we ‘assumed’ that the assumptions underlying synthesis methodologies would be a distinguishing characteristic of synthesis types, and that we could compare the various types on their assumptions, explicit or implicit. We found, however, that many authors did not explicate the underlying assumptions of their methodologies, and it was difficult to infer them. Kirkevold [101] has argued that integrative reviews need to be carried out from an explicit philosophical or theoretical perspective. We argue this should be true for all types of synthesis.

Authors of some emerging synthesis approaches have been very explicit about their assumptions and philosophical underpinnings. An implicit assumption of most emerging synthesis methodologies is that quantitative systematic reviews and meta-analyses have limited utility in some fields [e.g., in public health – [13] , [102] ] and for some kinds of review questions like those about feasibility and appropriateness versus effectiveness [103] – [104] . They also assume that ontologically and epistemologically, both kinds of data can be combined. This is a significant debate in the literature because it is about the commensurability of overarching paradigms [105] but this is beyond the scope of this review.

Realist synthesis is philosophically grounded in critical realism or, as noted above, a realist logic of inquiry [93] , [99] , [106] – [107] . Key assumptions regarding the nature of interventions that inform critical realism have been described above in the section on context. See Pawson et al. [106] for more information on critical realism, the philosophical basis of realist synthesis.

Meta-narrative synthesis is explicitly rooted in a constructivist philosophy of science [108] in which knowledge is socially constructed rather than discovered, and what we take to be ‘truth’ is a matter of perspective. Reality has a pluralistic and plastic character, and there is no pre-existing ‘real world’ independent of human construction and language [109] . See Greenhalgh et al. [67] , [85] and Greenhalgh & Wong [97] for more discussion of the constructivist basis of meta-narrative synthesis.

In the case of purely quantitative or qualitative syntheses, it may be an easier matter to uncover unstated assumptions because they are likely to be shared with those of the primary studies in the genre. For example, grounded formal theory shares the philosophical and theoretical underpinnings of grounded theory, rooted in the theoretical perspective of symbolic interactionism [110] – [111] and the philosophy of pragmatism [87] , [112] – [114] .

As with meta-narrative synthesis, meta-study developers identify constructivism as their interpretive philosophical foundation [54] , [88] . Epistemologically, constructivism focuses on how people construct and re-construct knowledge about a specific phenomenon, and has three main assumptions: (1) reality is seen as multiple, at times even incompatible with the phenomenon under consideration; (2) just as primary researchers construct interpretations from participants' data, meta-study researchers also construct understandings about the primary researchers' original findings. Thus, meta-synthesis is a construction of a construction, or a meta-construction; and (3) all constructions are shaped by the historical, social and ideological context in which they originated [54] . The key message here is that reports of any synthesis would benefit from an explicit identification of the underlying philosophical perspectives to facilitate a better understanding of the results, how they were derived, and how they are being interpreted.

4.7. Unit of Analysis

The unit of analysis for each category of review is generally distinct. For the emerging synthesis approaches, the unit of analysis is specific to the intention. In meta-narrative synthesis it is the storyline in diverse research traditions; in rapid review or scoping review, it depends on the focus but could be a concept; and in realist synthesis, it is the theories rather than programs that are the units of analysis. The elements of theory that are important in the analysis are mechanisms of action, the context, and the outcome [107] .

For qualitative synthesis, the units of analysis are generally themes, concepts or theories, although in meta-study, the units of analysis can be research findings (“meta-data-analysis”), research methods (“meta-method”) or philosophical/theoretical perspectives (“meta-theory”) [54] . In quantitative synthesis, the units of analysis range from specific statistics for systematic reviews to effect size of the intervention for meta-analysis. More recently, some systematic reviews focus on theories [115] – [116] , therefore it depends on the research question. Similarly, within conventional literature synthesis the units of analysis also depend on the research purpose, focus and question as well as on the type of research methods incorporated into the review. What is important in all research syntheses, however, is that the unit of analysis needs to be made explicit. Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

4.8. Strengths and Limitations

In this section, we discuss the overarching strengths and limitations of synthesis methodologies as a whole and then highlight strengths and weaknesses across each of our four categories of synthesis.

4.8.1. Strengths of Research Syntheses in General

With the vast proliferation of research reports and the increased ease of retrieval, research synthesis has become more accessible providing a way of looking broadly at the current state of research. The availability of syntheses helps researchers, practitioners, and policy makers keep up with the burgeoning literature in their fields without which evidence-informed policy or practice would be difficult. Syntheses explain variation and difference in the data helping us identify the relevance for our own situations; they identify gaps in the literature leading to new research questions and study designs. They help us to know when to replicate a study and when to avoid excessively duplicating research. Syntheses can inform policy and practice in a way that well-designed single studies cannot; they provide building blocks for theory that helps us to understand and explain our phenomena of interest.

4.8.2. Limitations of Research Syntheses in General

The process of selecting, combining, integrating, and synthesizing across diverse study designs and data types can be complex and potentially rife with bias, even with those methodologies that have clearly defined steps. Just because a rigorous and standardized approach has been used does not mean that implicit judgements will not influence the interpretations and choices made at different stages.

In all types of synthesis, the quantity of data can be considerable, requiring difficult decisions about scope, which may affect relevance. The quantity of available data also has implications for the size of the research team. Few reviews these days can be done independently, in particular because decisions about inclusion and exclusion may require the involvement of more than one person to ensure reliability.

For all types of synthesis, it is likely that in areas with large, amorphous, and diverse bodies of literature, even the most sophisticated search strategies will not turn up all the relevant and important texts. This may be more important in some synthesis methodologies than in others, but the omission of key documents can influence the results of all syntheses. This issue can be addressed, at least in part, by including a library scientist on the research team as required by some funding agencies. Even then, it is possible to miss key texts. In this review, for example, because none of us are trained in or conduct meta-analyses, we were not even aware that we had missed some new developments in this field such as meta-regression [117] – [118] , network meta-analysis [119] – [121] , and the use of individual patient data in meta-analyses [122] – [123] .

One limitation of systematic reviews and meta-analyses is that they rapidly go out of date. We thought this might be true for all types of synthesis, although we wondered if those that produce theory might not be somewhat more enduring. We have not answered this question but it is open for debate. For all types of synthesis, the analytic skills and the time required are considerable so it is clear that training is important before embarking on a review, and some types of review may not be appropriate for students or busy practitioners.