Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Distance learning in higher education during COVID-19: The role of basic psychological needs and intrinsic motivation for persistence and procrastination–a multi-country study

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Data curation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Mathematics, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Faculty of Education, Aleksandër Moisiu University, Durrës, Albania

Affiliation Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Philology and Education, Bedër University, Tirana, Albania

Affiliation Xiangya School of Nursing, Central South University, Changsha, China

Affiliations Xiangya School of Nursing, Central South University, Changsha, China, Department of Nursing Science, University of Turku, Turku, Finland

Affiliation Study of Nursing, University of Applied Sciences Bjelovar, Bjelovar, Croatia

Affiliation Baltic Film, Media and Arts School, Tallinn University, Tallinn, Estonia

Affiliation Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Affiliation Department of Psychology, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany

Affiliation Chair of Educational Psychology, Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Affiliation Department of Educational Studies, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

Affiliation Faculty of Education, University of Akureyri, Akureyri, Iceland

Affiliation Department of Global Education, Tsuru University, Tsuru, Japan

Affiliation Career Center, Osaka University, Osaka University, Suita, Japan

Affiliation Graduate School of Education, Osaka Kyoiku University, Kashiwara, Japan

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Prishtina ’Hasan Prishtina’, Pristina, Kosovo

Affiliation Department of Social Work, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Pristina ’Hasan Prishtina’, Pristina, Kosovo

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Klaipėda University, Klaipėda, Lithuania

Affiliation Geography Department, Junior College, University of Malta, Msida, Malta

Affiliation Institute of Family Studies, Faculty of Philosophy, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Skopje, North Macedonia

Affiliation Institute of Psychology, Faculty of Social Science, University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland

Affiliation Faculty of Historical and Pedagogical Sciences, University of Wrocław, Wrocław, Poland

Affiliation Faculty of Educational Studies, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland

Affiliation CERNESIM Environmental Research Center, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Iași, România

Affiliation Social Sciences and Humanities Research Department, Institute for Interdisciplinary Research, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iași, Iași, România

Affiliation Department of Informatics, Örebro University School of Business, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden

Affiliation Faculty of Social Studies, Penn State University, State College, Pennsylvania, United States of America

- [ ... ],

Affiliations Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, Department for Teacher Education, Centre for Teacher Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- [ view all ]

- [ view less ]

- Elisabeth R. Pelikan,

- Selma Korlat,

- Julia Reiter,

- Julia Holzer,

- Martin Mayerhofer,

- Barbara Schober,

- Christiane Spiel,

- Oriola Hamzallari,

- Ana Uka,

- Published: October 6, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, higher educational institutions worldwide switched to emergency distance learning in early 2020. The less structured environment of distance learning forced students to regulate their learning and motivation more independently. According to self-determination theory (SDT), satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence and social relatedness affects intrinsic motivation, which in turn relates to more active or passive learning behavior. As the social context plays a major role for basic need satisfaction, distance learning may impair basic need satisfaction and thus intrinsic motivation and learning behavior. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between basic need satisfaction and procrastination and persistence in the context of emergency distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in a cross-sectional study. We also investigated the mediating role of intrinsic motivation in this relationship. Furthermore, to test the universal importance of SDT for intrinsic motivation and learning behavior under these circumstances in different countries, we collected data in Europe, Asia and North America. A total of N = 15,462 participants from Albania, Austria, China, Croatia, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Japan, Kosovo, Lithuania, Poland, Malta, North Macedonia, Romania, Sweden, and the US answered questions regarding perceived competence, autonomy, social relatedness, intrinsic motivation, procrastination, persistence, and sociodemographic background. Our results support SDT’s claim of universality regarding the relation between basic psychological need fulfilment, intrinsic motivation, procrastination, and persistence. However, whereas perceived competence had the highest direct effect on procrastination and persistence, social relatedness was mainly influential via intrinsic motivation.

Citation: Pelikan ER, Korlat S, Reiter J, Holzer J, Mayerhofer M, Schober B, et al. (2021) Distance learning in higher education during COVID-19: The role of basic psychological needs and intrinsic motivation for persistence and procrastination–a multi-country study. PLoS ONE 16(10): e0257346. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346

Editor: Shah Md Atiqul Haq, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, BANGLADESH

Received: March 30, 2021; Accepted: August 29, 2021; Published: October 6, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Pelikan et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data is now publicly available: Pelikan ER, Korlat S, Reiter J, Lüftenegger M. Distance Learning in Higher Education During COVID-19: Basic Psychological Needs and Intrinsic Motivation 2021. doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/8CZX3 .

Funding: This work was funded by the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF) [ https://www.wwtf.at/ ] and the MEGA Bildungsstiftung [ https://www.megabildung.at/ ] through project COV20-025, as well as the Academy of Finland [ https://www.aka.fi ] through project 308351, 336138, and 345117. BS is the grant recipient of COV20-025. KSA is the grant recipient of 308351, 336138, and 345117. Open access funding was provided by University of Vienna. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

In early 2020, countries across the world faced rising COVID-19 infection rates, and various physical and social distancing measures to contain the spread of the virus were adopted, including curfews and closures of businesses, schools, and universities. By the end of April 2020, roughly 1.3 billion learners were affected by the closure of educational institutions [ 1 ]. At universities, instruction was urgently switched to distance learning, bearing challenges for all actors involved, particularly for students [ 2 ]. Moreover, since distance teaching requires ample preparation time and situation-specific didactic adaptation to be successful, previously established concepts for and research findings on distance learning cannot be applied undifferentiated to the emergency distance learning situation at hand [ 3 ].

Generally, it has been shown that the less structured learning environment in distance learning requires students to regulate their learning and motivation more independently [ 4 ]. In distance learning in particular, high intrinsic motivation has proven to be decisive for learning success, whereas low intrinsic motivation may lead to maladaptive behavior like procrastination (delaying an intended course of action despite negative consequences) [ 5 , 6 ]. According to self-determination theory (SDT), satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence and social relatedness leads to higher intrinsic motivation [ 7 ], which in turn promotes adaptive patterns of learning behavior. On the other hand, dissatisfaction of these basic psychological needs can detrimentally affect intrinsic motivation. According to SDT, satisfaction of the basic psychological needs occurs in interaction with the social environment. The context in which learning takes place as well as the support of social interactions it encompasses play a major role for basic need satisfaction [ 7 , 8 ]. Distance learning, particularly when it occurs simultaneously with other physical and social distancing measures, may impair basic need satisfaction and, in consequence, intrinsic motivation and learning behavior.

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between basic need satisfaction and two important learning behaviors—procrastination (as a consequence of low or absent intrinsic motivation) and persistence (as the volitional implementation of motivation)—in the context of emergency distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. In line with SDT [ 7 ] and previous studies (e.g., [ 9 ]), we also investigated the mediating role of intrinsic motivation in this relationship. Furthermore, to test the universal importance of SDT for intrinsic motivation and learning behavior under these specific circumstances, we collected data in 17 countries in Europe, Asia, and North America.

The fundamental role of basic psychological needs for intrinsic motivation and learning behavior

SDT [ 7 ] provides a broad framework for understanding human motivation, proposing that the three basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and social relatedness must be satisfied for optimal functioning and intrinsic motivation. The need for autonomy refers to an internal perceived locus of control and a sense of agency. In an academic context, students who learn autonomously feel that they have an active choice in shaping their learning process. The need for competence refers to the feeling of being effective in one’s actions. In addition, students who perceive themselves as competent feel that they can successfully meet challenges and accomplish the tasks they are given. Finally, the need for social relatedness refers to feeling connected to and accepted by others. SDT proposes that the satisfaction of each of these three basic needs uniquely contributes to intrinsic motivation, a claim that has been proved in numerous studies and in various learning contexts. For example, Martinek and colleagues [ 10 ] found that autonomy satisfaction was positively whereas autonomy frustration was negatively related to intrinsic motivation in a sample of university students during COVID-19. The same held true for competence satisfaction and dissatisfaction. A recent study compared secondary school students who perceived themselves as highly competent in dealing with their school-related tasks during pandemic-induced distance learning to those who perceived themselves as low in competence [ 11 ]. Students with high perceived competence not only reported higher intrinsic motivation but also implemented more self-regulated learning strategies (such as goal setting, planning, time management and metacognitive strategies) and procrastinated less than students who perceived themselves as low in competence. Of the three basic psychological needs, the findings on the influence of social relatedness on intrinsic motivation have been most ambiguous. While in some studies, social relatedness enhanced intrinsic motivation (e.g., [ 12 ]), others could not establish a clear connection (e.g., [ 13 ]).

Intrinsic motivation, in turn, is regarded as particularly important for learning behavior and success (e.g., [ 6 , 14 ]). For example, students with higher intrinsic motivation tend to engage more in learning activities [ 9 , 15 ], show higher persistence [ 16 ] and procrastinate less [ 6 , 17 , 18 ]. Notably, intrinsic motivation is considered to be particularly important in distance learning, where students have to regulate their learning themselves. Distance-learning students not only have to consciously decide to engage in learning behavior but also persist despite manifold distractions and less external regulation [ 4 ].

Previous research also indicates that the satisfaction of each basic need uniquely contributes to the regulation of learning behavior [ 19 ]. Indeed, studies have shown a positive relationship between persistence and the three basic needs (autonomy [ 20 ]; competence [ 21 ]; social relatedness [ 22 ]). Furthermore, all three basic psychological needs have been found to be related to procrastination. In previous research with undergraduate students, autonomy-supportive teaching behavior was positively related to satisfaction of the needs for autonomy and competence, both of which led to less procrastination [ 23 ]. A qualitative study by Klingsieck and colleagues [ 18 ] supports the findings of previous studies on the relations of perceived competence and autonomy with procrastination, but additionally suggests a lack of social relatedness as a contributing factor to procrastination. Haghbin and colleagues [ 24 ] likewise found that people with low perceived competence avoided challenging tasks and procrastinated.

SDT has been applied in research across various contexts, including work (e.g., [ 25 ]), health (e.g., [ 26 ]), everyday life (e.g., [ 27 ]) and education (e.g., [ 15 , 28 ]). Moreover, the pivotal role of the three basic psychological needs for learning outcomes and functioning has been shown across multiple countries, including collectivistic as well as individualistic cultures (e.g., [ 29 , 30 ]), leading to the conclusion that satisfaction of the three basic needs is a fundamental and universal determinant of human motivation and consequently learning success [ 31 ].

Self-determination theory in a distance learning setting during COVID-19

As Chen and Jang [ 28 ] observed, SDT lends itself particularly well to investigating distance learning, as the three basic needs for autonomy, competence and social relatedness all relate to important aspects of distance learning. For example, distance learning usually offers students greater freedom in deciding where and when they want to learn [ 32 ]. This may provide students with a sense of agency over their learning, leading to increased perceived autonomy. At the same time, it requires students to regulate their motivation and learning more independently [ 4 ]. In the unique context of distance learning during COVID-19, it should be noted that students could not choose whether and to what extent to engage in distance learning, but had to comply with external stipulations, which in turn may have had a negative effect on perceived autonomy. Furthermore, distance learning may also influence perceived competence, as this is in part developed by receiving explicit or implicit feedback from teachers and peers [ 33 ]. Implicit feedback in particular may be harder to receive in a distance learning setting, where informal discussions and social cues are largely absent. The lack of face-to-face contact may also impede social relatedness between students and their peers as well as students and their teachers. Well-established communication practices are crucial for distance learning success (see [ 34 ] for an overview). However, providing a nurturing social context requires additional effort and guidance from teachers, which in turn necessitates sufficient skills and preparation on their part [ 34 , 35 ]. Moreover, the sudden switch to distance learning due to COVID-19 did not leave teachers and students time to gradually adjust to the new learning situation [ 36 ]. As intrinsic motivation is considered particularly relevant in the context of distance education [ 28 , 37 ], applying the SDT framework to the novel situation of pandemic-induced distance learning may lead to important insights that allow for informed recommendations for teachers and educational institutions about how to proceed in the context of continued distance teaching and learning.

In summary, the COVID-19 situation is a completely new environment, and basic need satisfaction during learning under pandemic-induced conditions has not been explored before. Considering that closures of educational institutions have affected billions of students worldwide and have been strongly debated in some countries, it seems particularly relevant to gain insights into which factors consistently influence conducive or maladaptive learning behavior in these circumstances in a wide range of countries and contextual settings.

Therefore, the overall goal of this study is to investigate the well-established relationship between the three basic needs for autonomy, competence, and social relatedness with intrinsic motivation in the new and specific situation of pandemic-induced distance learning. Firstly, we examine the relationship between each of the basic needs with intrinsic motivation. We expect that perceived satisfaction of the basic needs for autonomy (H1a), competence (H1b) and social relatedness (H1c) would be positively related to intrinsic motivation. In our second research question, we furthermore extend SDT’s predictions regarding two important aspects of learning behavior–procrastination (as a consequence of low or absent intrinsic motivation) and persistence (as the implementation of the volitional part of motivation) and hypothesize that each basic need will be positively related to persistence and negatively related to procrastination, both directly (procrastination: H2a –c; persistence: H3a –c) and mediated by intrinsic motivation (procrastination: H4a –c; persistence: H5a –c). We also proposed that perceived autonomy, competence, and social relatedness would have a direct negative relation with procrastination (H6a –c) and a direct positive relation with persistence (H7a –c). Finally, we investigate SDT’s claim of universality, and assume that the aforementioned relationships will emerge across countries we therefore expect a similar pattern of results in all observed countries (H8a –c). As previous studies have indicated that gender [ 4 , 17 , 38 ] and age [ 39 , 40 ]. May influence intrinsic motivation, persistence, and procrastination, we included participants’ gender and age as control variables.

Study design

Due to the circumstances, we opted for a cross-sectional study design across multiple countries, conducted as an online survey. We decided for an online-design due to the pandemic-related restrictions on physical contact with potential survey participants as well as due to the potential to reach a larger audience. As we were interested in the current situation in schools than in long-term development, and we were particularly interested in a large-scale section of the population in multiple countries, we decided on a cross-sectional design. In addition, a multi-country design is particularly interesting in a pandemic setting: During this global health crisis, educational institutions in all countries face the same challenge (to provide distance learning in a way that allows students to succeed) but do so within different frameworks depending on the specific measures each country has implemented. This provides a unique basis for comparing the effects of need fulfillment on students’ learning behavior cross-nationally, thus testing the universality of SDT.

Sample and procedure

The study was carried out across 17 countries, with central coordination taking place in Austria. It was approved and supported by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research and conducted online. International cooperation partners were recruited from previously established research networks (e.g., European Family Support Network [COST Action 18123]; Transnational Collaboration on Bullying, Migration and Integration at School Level [COST Action 18115]; International Panel on Social), resulting in data collection in 16 countries (Albania, China, Croatia, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Japan, Kosovo, Lithuania, Poland, Malta, North Macedonia, Romania, Sweden, USA) in addition to Austria. Data collection was carried out between April and August 2020. During this period, all participating countries were in some degree of pandemic-induced lockdown, which resulted in universities temporarily switching to distance learning. The online questionnaires were distributed among university students via online surveys by the research groups in each respective country. No restrictions were placed on participation other than being enrolled at a university in the sampling country. Participants were informed about the goals of the study, expected time it would take to fill out the questionnaire, voluntariness of participation and anonymity of the acquired data. All research partners ensured that all ethical and legal requirements related to data collection in their country context were met.

Only data from students who gave their written consent to participate, had reached the age of majority (18 or older) and filled out all questions regarding the study’s main variables were included in the analyses (for details on data cleaning rules and exclusion criteria, see [ 41 ]). Additional information on data collection in the various countries is provided in S1 Table in S1 File .

The overall sample of N = 15,462 students was predominantly female (71.7%, 27.4% male and 0.7% diverse) and ranged from 18 to 71 years, with the average participant age being 24.41 years ( SD = 6.93, Mdn = 22.00). Sample descriptives per country are presented in Table 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.t001

The variables analyzed here were part of a more extensive questionnaire; the complete questionnaire, as well as the analysis code and the data set, can be found at OSF [ 42 ] In order to take the unique situation into account, existing scales were adapted to the current pandemic context (e.g., adding “In the current home-learning situation …”), and supplemented with a small number of newly developed items. Subsequently, the survey was revised based on expert judgements from our research group and piloted with cognitive interview testing. The items were sent to the research partners in English and translated separately by each respective research team either using the translation-back-translation method or by at least two native-speaking experts. Subsequently, any differences were discussed, and a consolidated version was established.

To assure the reliability of the scales, we analyzed them using alpha coefficients separately for each country (see S2–S18 Tables in S1 File ). All items were answered on a rating scale from 1 (= strongly agree) to 5 (= strongly disagree) and students were instructed to answer with regard to the current situation (distance learning during the COVID-19 lockdown). Analyses were conducted with recoded items so that higher values reflected higher agreement with the statements.

Perceived autonomy was measured with two newly constructed items (“Currently, I can define my own areas of focus in my studies” and “Currently, I can perform tasks in the way that best suits me”; average α = .78, ranging from .62 to .86).

Perceived competence was measured with three items, which were constructed based on the Work-related Basic Need Satisfaction Scale (W-BNS; [ 25 ]) and transferred to the learning context (“Currently, I am dealing well with the demands of my studies”, “Currently, I have no doubts about whether I am capable of doing well in my studies” and “Currently, I am managing to make progress in studying for university”; average α = .83, ranging from .74 to .91).

Perceived social relatedness was assessed with three items, based on the W-BNS [ 43 ], (“Currently, I feel connected with my fellow students”, “Currently, I feel supported by my fellow students”) and the German Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale [ 44 ]; “Currently, I feel connected with the people who are important to me (family, friends)”; average α = .73, ranging from .64 to .88).

Intrinsic motivation was measured with three items which were slightly adapted from the Scales for the Measurement of Motivational Regulation for Learning in University Students (SMR-LS; [ 45 ]; “Currently, doing work for university is really fun”, “Currently, I am really enjoying studying and doing work for university” and “Currently, I find studying for university really exciting”; average α = .91, ranging from .83 to .94).

Procrastination was measured with three items adapted from the Procrastination Questionnaire for Students (Prokrastinationsfragebogen für Studierende; PFS; [ 46 ]): “In the current home-learning situation, I postpone tasks until the last minute”, “In the current home-learning situation, I often do not manage to start a task when I set out to do so”, and “In the current home-learning situation, I only start working on a task when I really need to”; average α = .88, ranging from .74 to .91).

Persistence was measured with three items adapted from the EPOCH measure [ 47 ]: “In the current home-learning situation, I finish whatever task I begin”, “In the current home-learning situation, I keep at my tasks until I am done with them” and “In the current home-learning situation, once I make a plan to study, I stick to it”; average α = .81, ranging from .74 to .88).

Data analysis.

Data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 26.0 and Mplus version 8.4. First, we tested for measurement invariance between countries prior to any substantial analyses. We conducted a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (CFAs) for all scales individually to test for configural, metric, and scalar invariance [ 48 , 49 ] (see S19 Table in S1 File ). We used maximum likelihood parameter estimates with robust standard errors (MLR) to deal with the non-normality of the data. CFI and RMSEA were used as indicators for absolute goodness of model fit. In line with Hu and Bentler [ 50 ], the following cutoff scores were considered to reflect excellent and adequate fit to the data, respectively: (a) CFI > 0.95 and CFI > 0.90; (b) RMSEA < .06 and RMSEA < .08. Relative model fit was assessed by comparing BICs of the nested models, with smaller BIC values indicating a better trade-off between model fit and model complexity [ 51 ]. Configural invariance indicates a factor structure that is universally applicable to all subgroups in the analysis, metric invariance implies that participants across all groups attribute the same meaning to the latent constructs measured, and scalar invariance indicates that participants across groups attribute the same meaning to the levels of the individual items [ 51 ]. Consequently, the extent to which the results can be interpreted depends on the level of measurement invariance that can be established.

For the main analyses, three latent multiple group mediation models were computed, each including one of the basic psychological needs as a predictor, intrinsic motivation as the mediator and procrastination and persistence as the outcomes. These three models served to test the hypothesis that perceived autonomy, competence and social relatedness are related to levels of procrastination and persistence, both directly and mediated through intrinsic motivation. We used bootstrapping in order to provide analyses robust to non-normal distribution variations, specifying 5,000 bootstrap iterations [ 52 ]. Results were estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) method. Bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals are reported.

Finally, in an exploratory step, we investigated the international applicability of the direct and mediated effects. To this end, an additional set of latent mediation models was computed where the path estimates were fixed in order to create an average model across all countries. This was prompted by the consistent patterns of results across countries we observed in the multigroup analyses. Model fit indices of these average models were compared to those of the multigroup models in order to establish the similarity of path coefficients between countries.

Statistical prerequisites

Table 2 provides overall descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables (see S2–S18 Tables in S1 File for descriptive statistics for the individual countries).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.t002

Metric measurement variance, but not scalar measurement invariance could be established for a simple model including the three individual items and no inter-correlations between perceived competence, perceived social relatedness, intrinsic motivation, and procrastination. For these four variables, the metric invariance model had a good absolute fit, whereas the scalar model did not, due to too high RMSEA; moreover, the relative fit was best for the metric model compared to both the configural and scalar model (see S18 Table in S1 File ). Metric, but not scalar invariance could also be established for persistence after modelling residual correlations between items 1 and 2 and items 2 and 3 of the scale. This was necessary due to the similar wording of the items (see “Measures” section for item wordings). Consequently, the same residual correlations were incorporated into all mediation models.

Finally, as the perceived autonomy scale consisted of only two items, it had to be fitted in a model with a correlating factor in order to compute measurement invariance. Both perceived competence and perceived social relatedness were correlated with perceived autonomy ( r = .59** and r = .31**, respectively; see Table 2 ). Therefore, we fit two models combining perceived autonomy with each of these factors; in both cases, metric measurement invariance was established (see S19 Table in S1 File ).

In summary, these results suggest that the meaning of all constructs we aimed to measure was understood similarly by participants across different countries. Consequently, we were able to fit the same mediation model in all countries and compare the resulting path coefficients.

Both gender and age were statistically significantly correlated with perceived competence, perceived social relatedness, intrinsic motivation, procrastination, and persistence (see S20–S22 Tables in S1 File ).

Mediation analyses

Autonomy hypothesis..

We hypothesized that higher perceived autonomy would relate to less procrastination and more persistence, both directly and indirectly (mediated through intrinsic learning motivation). Indeed, perceived autonomy was related negatively to procrastination (H6a) in most countries. Confidence intervals did not include zero in 10 out of 17 countries, all effect estimates were negative and standardized effect estimates ranged from b stand = - .02 to -.46 (see Fig 1 ). Furthermore, perceived autonomy was directly positively related to persistence in most countries. Specifically, for the direct effect of perceived autonomy on persistence (H7a), all but one country (USA, b stand = -.02; p = .621; CI [-.13, .08]) exhibited distinctly positive effect estimates ranging from b stand = .18 to .72 and confidence intervals that did not include zero.

Countries are ordered by sample size from top (highest) to bottom (lowest).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.g001

In terms of indirect effects of perceived autonomy on procrastination mediated by intrinsic motivation (H7a), confidence intervals did not include zero in 8 out of 17 countries and effect estimates were mostly negative, ranging from b stand = -.33 to .03. Indirect effects of perceived autonomy on persistence (mediated by intrinsic motivation; H5a) were distinctly positive and confidence intervals did not include zero in 12 out of 17 countries. The indirect effect estimates and confidence intervals for all remaining countries were consistently positive, with the standardized effect estimates ranging from b stand = .13 to .39, indicating a robust, positive mediated effect of autonomy on persistence. Fig 2 displays the unstandardized path coefficients and their two-sided 5% confidence intervals for the indirect effects of perceived autonomy on procrastination via intrinsic motivation (left) and of perceived autonomy on persistence via intrinsic motivation (right).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.g002

Unstandardized and standardized path coefficients, standard errors, p-values and bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals for the direct and indirect effects of perceived autonomy on procrastination and persistence for each country are provided in S23–S26 Tables in S1 File , respectively.

Competence hypothesis. Secondly, we hypothesized that higher perceived competence would relate to less procrastination and more persistence both directly and indirectly, mediated through intrinsic learning motivation. Direct effects on procrastination (H6b) were negative in most countries and confidence intervals did not include zero in 10 out of 17 countries (see Fig 3 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.g003

Standardized effect estimates ranged from b stand = -.02 to -.60, with 10 out of 17 countries exhibiting at least a medium-sized effect. Correspondingly, effect estimates for the direct effects on persistence were positive everywhere except the USA and confidence intervals did not include zero in 14 out of 17 countries (see Fig 3 ). Standardized effect estimates ranged from b stand = -.05 to .64 with 14 out of 17 countries displaying an at least medium-sized positive effect.

The pattern of results for the indirect effects of perceived competence on procrastination mediated by learning motivation (H4b) is illustrated in Fig 4 : Effect estimates were negative with the exception of China and the USA. Confidence intervals did not include zero in 7 out of 17 countries. Standardized effect estimates range between b stand = .06 and -.46. Indirect effects of perceived competence on persistence were positive everywhere except for two countries and confidence intervals did not include zero in 7 out of 17 countries (see Fig 4 ). Standardized effect estimates varied between b stand = -.07 and .46 (see S23–S26 Tables in S1 File for unstandardized and standardized path coefficients).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.g004

Social relatedness hypothesis.

Finally, we hypothesized that stronger perceived social relatedness would be both directly and indirectly (mediated through intrinsic learning motivation) related to less procrastination and more persistence. The pattern of results was more ambiguous here than for perceived autonomy and perceived competence. Direct effect estimates on procrastination (H6c) were negative in 12 countries; however, the confidence intervals included zero in 12 out of 17 countries (see Fig 5 ). Standardized effect estimates ranged from b stand = -.01 to b stand = .33. The direct relation between perceived social relatedness and persistence (H7c) yielded 14 negative and three positive effect estimates. Confidence intervals did not include zero in 7 out of 17 countries (see Fig 5 ), with standardized effect estimates ranging from b stand = -.01 to b stand = .31.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.g005

In terms of indirect effects of perceived social relatedness being related to procrastination mediated by intrinsic motivation (H4c), the pattern of results was consistent: All effect estimates except those for the USA were clearly negative, and confidence intervals did not include zero in 15 out of 17 countries (see Fig 6 ). Standardized effect estimates ranged between b stand = .00 and b stand = -.46. Indirect paths of perceived social relatedness on persistence showed positive effect estimates and standardized effect estimates ranging from b stand = .00 to .44 and confidence intervals not including zero in 16 out of 17 countries (see Fig 6 ; see S23–S26 Tables in S1 File for unstandardized and standardized path coefficients).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.g006

Meta-analytic approach

Due to the overall similarity of the results across many countries, we decided to compute, in an additional, exploratory step, the same models with path estimates fixed across countries. This resulted in three models with average path estimates across the entire sample. Standardized path coefficients for the direct and indirect effects of the basic psychological needs on procrastination and persistence are presented in S27 and S28 Tables in S1 File , respectively. We compared the model fits of these three average models to those of the multigroup mediation models: If the fit of the average model is better than that of the multigroup model, it indicates that the individual countries are similar enough to be combined into one model. The amount of explained variance per model, outcome variable and country are provided in S29 Table in S1 File for procrastination and S30 Table in S1 File for persistence.

Perceived autonomy.

Relative model fit was better for the perceived autonomy model with fixed paths (BIC = 432,707.89) compared to the multigroup model (BIC = 432,799.01). Absolute model fit was equally good in the multigroup model (RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97) and in the fixed path model (RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97). Consequently, the general model in Fig 7 describes the data from all 17 countries equally well. The average amount of explained variance, however, is slightly higher in the multigroup model, with 19.9% of the variance in procrastination and 33.7% of the variance in persistence explained, as compared to 18.3% and 27.6% in the fixed path model. The amount of variance explained increased substantially in some countries when fixing the paths: in the multigroup model, explained variance ranges from 2.2% to 44.4% for procrastination and from 0.9% to 69.9% for persistence, compared to 13.0% - 27.7% and 18.2% to 63.2% in the fixed path model. Notably, the amount of variance explained did not change much in the three countries with the largest samples, Austria, Sweden, and Finland; countries with much smaller samples and larger confidence intervals were more affected.

*** p = < .001.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.g007

Overall, perceived autonomy had significant direct and indirect effects on both procrastination and persistence; higher perceived autonomy was related to less procrastination directly ( b unstand = -.27, SE = .02, p = < .001) and mediated by learning motivation ( b unstand = -.20, SE = .01, p = < .001) and to more persistence directly ( b unstand = .24, SE = .01, p = < .001) and mediated by learning motivation ( b unstand = .12, SE = .01, p = < .001). Direct effects for the autonomy model are shown in Fig 7 ; for the indirect effects see Table 3 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.t003

Effects of age and gender varied across countries (see S20 Table in S1 File ).

Perceived competence.

For the perceived competence model, relative fit decreased when fixing the path coefficient estimates (BIC = 465,830.44 to BIC = 466,020.70). The absolute fit indices were also better for the multigroup model (RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96) than for the fixed path model (RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96). Hence, multigroup modelling describes the data across all countries somewhat better than a fixed path model as depicted in Fig 8 . Correspondingly, the fixed path model explained less variance on average than did the multigroup model, with 23.2% instead of 24.3% of the variance in procrastination and 32.9% instead of 37.3% of the variance in persistence explained. Explained variance ranged from 1.0% to 51.9% for procrastination in the multigroup model, as compared to 13.9% - 34.4% in the fixed path model. The amount of variance in persistence explained ranged from 1.0% to 58.1% in the multigroup model and from 23.5% to 55.9% in the fixed path model (see S29 and S30 Tables in S1 File ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.g008

Overall, higher perceived competence was related to less procrastination ( b unstand = -.44, SE = .02, p = < .001) and to higher persistence ( b unstand = .32, SE = .01, p = < .001). These effects were partly mediated by intrinsic learning motivation ( b unstand = -.11, SE = .01, p = < .001, and b unstand = .07, SE = .01, p = < .001, respectively; see Table 3 ). Effects of gender and age varied between countries, see S21 Table in S1 File .

Perceived social relatedness.

Finally, the perceived social relatedness model with fixed paths had a relatively better model fit (BIC = 479,428.46) than the multigroup model (BIC = 479,604.61). Likewise, the absolute model fit was similar in the model with path coefficients fixed across countries (RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96) and the multigroup model (RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97). The multigroup model explained 17.6% of the variance in procrastination and 26.3% of the variance in persistence, as compared to 15.2% and 21.6%, respectively in the fixed path model. Explained variance for procrastination ranged between 0.5% and 48.1% in the multigroup model, and from 9.0% to 23.0% in the fixed path model. Similarly, the multigroup model explained between 1.0% and 56.5% of the variance in persistence across countries, while the fixed path model explained between 15.6% and 48.3% (see S29 and S30 Tables in S1 File ).

Hence, the fixed path model depicted in Fig 9 is well-suited for describing data across all 17 countries. Higher perceived social relatedness is related to less procrastination both directly ( b unstand = -.06, SE = .01, p = < .001) and indirectly through learning motivation ( b unstand = -.12, SE = .01, p = < .001). Likewise, it is related to higher persistence both directly ( b unstand = .07, SE = .01, p = < .001) and indirectly through learning motivation ( b unstand = .08, SE = .00, p = < .001; see Table 3 ). Effects of gender and age are shown in S22 Table in S1 File .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.g009

The aim of this study was to extend current research on the association between the basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and social relatedness with intrinsic motivation and two important aspects of learning behavior—procrastination and persistence—in the new and unique situation of pandemic-induced distance learning. We also investigated SDT’s [ 7 ] postulate that the relation between basic psychological need satisfaction and active (persistence) as well as passive (procrastination) learning behavior is mediated by intrinsic motivation. To test the theory’s underlying claim of universality, we collected data from N = 15,462 students across 17 countries in Europe, Asia, and North America.

Confirming our hypothesis, we found that the three basic psychological needs were consistently and positively related to intrinsic motivation in all countries except for the USA (H1a - c). This consistent result is in line with self-determination theory [ 7 ] and other previous studies (e.g., 9), which have found that satisfaction of the three basic needs for autonomy, competence and social relatedness is related to higher intrinsic motivation. Notably, the association with intrinsic motivation was stronger for perceived autonomy and perceived competence than for perceived social relatedness. This also has been found in previous studies [ 4 , 9 , 28 ]. Pandemic-induced distance learning, where physical and subsequential social contact in all areas of life was severely constricted, might further exacerbate this discrepancy, as instructors may have not been able to establish adequate communication structures due to the rapid switch to distance learning [ 36 , 53 ]. As hypothesized, intrinsic motivation was in general negatively related to procrastination (H2a - c) and positively related to persistence (H3a - c), indicating that students who are intrinsically motivated are less prone to procrastination and more persistent when studying. This again underlines the importance of intrinsic motivation for adaptive learning behavior, even and particularly in a distance learning setting, where students are more prone to disengage from classes [ 34 ].

The mediating effect of intrinsic motivation on procrastination and persistence

Direct effects of the basic needs on the outcomes were consistently more ambiguous (with smaller effect estimates and larger confidence intervals, including zero in more countries) than indirect effects mediated by intrinsic motivation. This difference was particularly pronounced for perceived social relatedness, where a clear negative direct effect on procrastination (H6c) could be observed only in the three countries with the largest sample size (Austria, Sweden, Finland) and Romania, whereas the confidence interval in most countries included zero. Moreover, in Estonia there was even a clear positive effect. The unexpected effect in the Estonian sample may be attributed to the fact that this country collected data only from international exchange students. Since the lockdown in Estonia was declared only a few weeks after the start of the semester, international exchange students had only a very short period of time to establish contacts with fellow students on site. Accordingly, there was probably little integration into university structures and social contacts were maintained more on a personal level with contacts from the home country. Thus, such students’ fulfillment of this basic need might have required more time and effort, leading to higher procrastination and less persistence in learning.

A diametrically opposite pattern was observed for persistence (H7c), where some direct effects of social relatedness were unexpectedly negative or close to zero. We therefore conclude that evidence for a direct negative relationship between social relatedness and procrastination and a direct positive relationship between social relatedness and persistence is lacking. This could be due to the specificity of the COVID-19 situation and resulting lockdowns, in which maintaining social contact took students’ focus off learning. In line with SDT, however, indirect effects of perceived social relatedness on procrastination (H4c) and persistence (H5c) mediated via intrinsic motivation were much more visible and in the expected directions. We conclude that, while the direct relation between perceived social relatedness and procrastination is ambiguous, there is strong evidence that the relationship between social relatedness and the measured learning behaviors is mediated by intrinsic motivation. Our results strongly underscore SDT’s assumption that close social relations promote intrinsic motivation, which in turn has a positive effect on learning behavior (e.g., [ 6 , 14 ]). The effects for perceived competence exhibited a somewhat clearer and hypothesis-conforming pattern. All direct effects of perceived competence on procrastination (H6b) were in the expected negative direction, albeit with confidence intervals spanning zero in 7 out of 17 countries. Direct effects of perceived competence on persistence (H7b) were consistently positive with the exception of the USA, where we observed a very small and non-significant negative effect. Indirect effects of perceived competence on procrastination (H4b) and persistence (H5b) as mediated by intrinsic motivation were mostly consistent with our expectations as well. Considering this overall pattern of results, we conclude that there is strong evidence that perceived competence is negatively associated with procrastination and positively associated with persistence. Furthermore, our results also support SDT’s postulate that the relationship between perceived competence and the measured learning behaviors is mediated by intrinsic motivation.

It is notable that the estimated direct effects of perceived competence on procrastination and persistence were higher than the indirect effects in most countries we investigated. Although SDT proposes that perceived competence leads to higher intrinsic motivation, Deci and Ryan [ 8 ] also argue that it affects all types of motivation and regulation, including less autonomous forms such as introjected and identified motivation, indicating that if the need for competence is not satisfied, all types of motivation are negatively affected. This may result in a general amotivation and lack of action. In our study, we only investigated intrinsic motivation as a mediator. For future research, it might be advantageous to further differentiate between different types of externally and internally controlled behavior. Furthermore, perceived competence increases when tasks are experienced as optimally challenging [ 7 , 54 ]. However, in order for instructors to provide the optimal level of difficulty and support needed, frequent communication with students is essential. Considering that data collection for the present study took place at a time of great uncertainty, when many countries had only transitioned to distance learning a few weeks prior, it is reasonable to assume that both structural support as well as communication and feedback mechanisms had not yet matured to a degree that would favor individualized and competency-based work.

However, our findings corroborate those from earlier studies insofar as they underline the associations between perceived competence and positive learning behavior (e.g., [ 19 ]), that is, lower procrastination [ 18 ] and higher persistence (e.g., [ 21 ]), even in an exceptional situation like pandemic-induced distance learning.

Turning to perceived autonomy, although the confidence intervals for the direct effects of perceived autonomy on procrastination (H6a) did span zero in most countries with smaller sample sizes, all effect estimates indicated a negative relation with procrastination. We expected these relationships from previous studies [ 18 , 23 ]; however, the effect might have been even more pronounced in the relatively autonomous learning situation of distance learning, where students usually have increased autonomy in deciding when, where, and how to learn. While this bears the risk of procrastination, it also comes with the opportunity to consciously delay less pressing tasks in favor of other, more important or urgent tasks (also called strategic delay ) [ 5 ], resulting in lower procrastination. In future studies, it might be beneficial to differentiate between passive forms of procrastination and active strategic delay in order to obtain more detailed information on the mechanisms behind this relationship. Direct effects of autonomy on persistence (H7a) were consistently positive. Students who are free to choose their preferred time and place to study may engage more with their studies and therefore be more persistent.

Indirect effects of perceived autonomy on procrastination mediated by intrinsic motivation (H4a) were negative in all but two countries (China and the USA), which is generally consistent with our hypothesis and in line with previous research (e.g., [ 23 ]). Additionally, we found a positive indirect effect of autonomy on persistence (H5a), indicating that autonomy and intrinsic motivation play a crucial role in students’ persistence in a distance learning setting. Based on our results, we conclude that perceived autonomy is negatively related to procrastination and positively related to persistence, and that this relationship is mediated by intrinsic motivation. It is worth noting that, unlike with perceived competence, the direct and indirect effects of perceived autonomy on the outcomes procrastination and persistence were similarly strong, suggesting that perceived autonomy is important not only as a driver of intrinsic motivation but also at a more direct level. It is important to make the best possible use of the opportunity for greater autonomy that distance learning offers. However, autonomy is not to be equated with a lack of structure; instead, learners should be given the opportunity to make their own decisions within certain framework conditions.

The applicability of self-determination theory across countries

Overall, the results of our mediation analysis for the separate countries support the claim posited by SDT that basic need satisfaction is essential for intrinsic motivation and learning across different countries and settings. In an exploratory analysis, we tested a fixed path model including all countries at once, in order to test whether a simplified general model would yield a similar amount of explained variance. For perceived autonomy and social relatedness, the model fit increased, whereas for perceived competence it decreased slightly compared to the multigroup model. However, all fixed path models exhibited adequate model fit. Considering that the circumstances in which distance learning took place in different countries varied to some degree (see also Limitations), these findings are a strong indicator for the universality of SDT.

Study strengths and limitations

Although the current study has several strengths, including a large sample size and data from multiple countries, three limitations must be considered. First, it must be noted that sample sizes varied widely across the 17 countries in our study, with one country above 6,000 (Austria), two above 1,000 (Finland and Sweden) and the rest ranging between 104 and 905. Random sampling effects are more problematic in smaller samples; hence, this large variation weakens our ability to conduct cross-country comparisons. At the same time, small sample sizes weaken the interpretability of results within each country; thus, our results for Austria, Finland and Sweden are considerably more robust than for the remaining fourteen countries. Additionally, two participating countries collected specific subsamples: In China, participants were only recruited from one university, a nursing school. In Estonia, only international exchange students were invited to participate. Nevertheless, with the exception of the unexpected positive direct relationship between social relatedness and procrastination, all observed divergent effects were non-significant. Indeed, this adds to the support for SDT’s claims to universality regarding the relationship between perceived autonomy, competence, and social relatedness with intrinsic motivation: Results in the included countries were, despite their differing subsamples, in line with the overall trend of results, supporting the idea that SDT applies equally to different groups of learners.

Second, due to the large number of countries in our sample and the overall volatility of the situation, learning circumstances were not identical for all participants. Due to factors such as COVID-19 case counts and national governments’ political priorities, lockdown measures varied in their strictness across settings. Some universities were fully closed, some allowed on-site teaching for particular groups (e.g., students in the middle of a laboratory internship), and some switched to distance learning but held exams on site (see S1 Table in S1 File for further information). Therefore, learning conditions were not as comparable as in a strict experimental setting. On the other hand, this strengthens the ecological validity of our study. The fact that the pattern of results was similar across contexts with certain variation in learning conditions further supports the universal applicability of SDT.

Finally, due to the novelty of the COVID-19 situation, some of the measures were newly developed for this study. Due to the need to react swiftly and collect data on the constantly evolving situation, it was not possible to conduct a comprehensive validation study of the instruments. Nevertheless, we were able to confirm the validity of our instruments in several ways, including cognitive interview testing, CFAs, CR, and measurement invariance testing.

Conclusion and future directions

In general, our results further support previous research on the relation between basic psychological need fulfilment and intrinsic motivation, as proposed in self-determination theory. It also extends past findings by applying this well-established theory to the new and unique situation of pandemic-induced distance learning across 17 different countries. Moreover, it underlines the importance of perceived autonomy and competence for procrastination and persistence in this setting. However, various other directions for further research remain to be pursued. While our findings point to the relevance of social relatedness for intrinsic motivation in addition to perceived competence and autonomy, further research should explore the specific mechanisms necessary to promote social connectedness in distance learning. Furthermore, in our study, we investigated intrinsic motivation, as the most autonomous form of motivation. Future research might address different types of externally and internally regulated motivation in order to further differentiate our results regarding the relations between basic need satisfaction and motivation. Finally, a longitudinal study design could provide deeper insights into the trajectory of need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation and learning behavior during extended periods of social distancing and could provide insights into potential forms of support implemented by teachers and coping mechanisms developed by students.

Supporting information

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346.s001

- 1. UNESCO [Internet]. 2020. COVID-19 Impact on Education; [cited 13 th March 2021]. Available from: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

- 2. United Nations. Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond [cited 13 th March 2021]. [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf#

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 16. Schunk DH, Pintrich PR, Meece JL. Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications. 4th ed. London: Pearson Higher Education; 2014.

- 19. Connell JP, Wellborn JG. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In: Gunnar MR, Sroufe LA, editors. Self-processes and development. Hilsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1991. pp. 43–77.

- 33. Legault L. The Need for Competence. 2017 [cited 22 March 2021]. In: Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [pp. 1–3]. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1123-1

- 36. Hodges C, Moore S, Lockee B, Trust T, Bond A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. 2020 March 27 [cited 13 th March 2021]. In: Educause Review [Internet]. Available from: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- 37. Mills R. The centrality of learner support in open and distance learning. In: Mills R, Tait A, editors. Rethinking learner support in distance education: Change and continuity in an international context. London: Routledge; 2003. pp. 102–113.

- 41. Schober B, Lüftenegger M, Spiel C. Learning conditions during COVID-19 Students (SUF edition); 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 22]. Database: AUSSDA [Internet]. Available from: https://data.aussda.at/citation?persistentId=10.11587/XIU3TX

- 42. Pelikan ER, Korlat S, Reiter J, Lüftenegger M. Distance Learning in Higher Education During COVID-19: Basic Psychological Needs and Intrinsic Motivation [Internet]. OSF; 2021. Available from: osf.io/8czx3

- 46. Glöckner-Rist A, Engberding M, Höcker A, Rist F. Prokrastinationsfragebogen für Studierende (PfS) [Procrastination Scale for Students]. In: Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen [Summary of items and scales in social science] ZIS Version 1300. Bonn: GESIS; 2014. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714002803 pmid:25482960

- 48. Millsap RE. Statistical approaches to measurement invariance. 1st ed. New York: Routledge; 2011.

- 52. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2018.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Research Briefing

- Published: 15 June 2022

Distance education strategies to improve learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

Nature Human Behaviour volume 6 , pages 913–914 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2532 Accesses

1 Citations

53 Altmetric

Metrics details

A randomized controlled trial of approximately 4,500 households in Botswana during the COVID-19 pandemic was conducted to investigate the effectiveness of using low-tech learning interventions during school closures. A simple combination of phone tutoring and SMS messages substantially improved learning in primary school children in a cost-effective manner.

The problem

The COVID-19 pandemic placed enormous pressure on education systems worldwide. At the peak of the crisis, school closures forced over 1.6 billion learners out of classrooms, exacerbating a learning crisis that existed before the pandemic 1 . Widespread school closures are not unique to COVID-19 — teacher strikes, summer breaks, earthquakes, viruses such as influenza and Ebola, and extreme weather conditions all result in school closures. The cost of school closures has proven to be substantial, particularly for households of lower socioeconomic status 2 , 3 . Reducing learning loss requires outside-school interventions that can effectively deliver instructions to children. However, little evidence exists on how to implement cost-effective learning interventions during school disruptions that can reach as many families as possible.

The solution

The use of mobile phones provides a potential solution to deliver educational instruction when schooling is disrupted, with the advantage of being widely accessible and cost effective 4 . However, this ‘low-tech’ solution is less commonly used in education relative to ‘high-tech’ approaches that rely on internet-based instruction, despite only 15–60% of households in low- and middle-income countries having internet access. By contrast, it is estimated that 70–90% of households own at least one mobile phone, suggesting that the use of mobile phones has the potential to provide educational instruction in resource-constrained contexts at scale. To examine this possibility, we conducted a randomized controlled trial, with a sample of approximately 4,500 households across Botswana, testing two mobile phone-based methods as low-tech solutions to support parents when educating children during the COVID-19 pandemic. In one treatment arm, SMS messages provided a few basic numeracy ‘problems of the week’; a second treatment arm supplemented these weekly SMS messages with a live 15–20-minute phone call from a teacher to provide a walkthrough of numeracy problems.

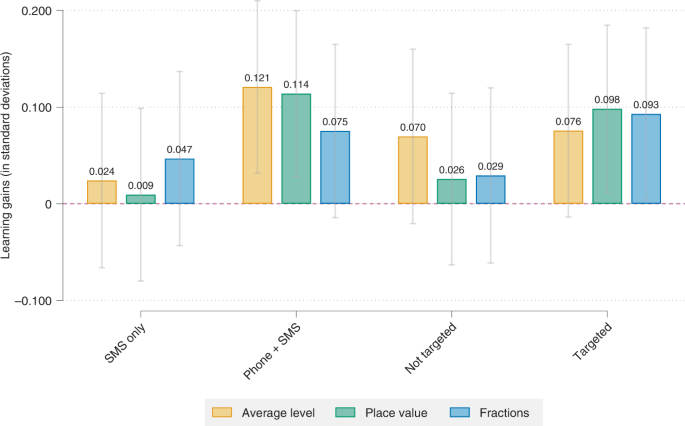

We found that SMS messages alone had little effect on household engagement in education and learning. However, a combination of phone calls with SMS interventions resulted in a pronounced improvement, increasing learning by 0.12 standard deviations (Fig. 1 ) — or up to 0.89 standard deviations of learning per US $100 — which represents one of the most cost-effective learning interventions 5 . We further developed remote assessments, as a means to measure learning, and found that targeting instruction on the basis of the results of assessments improved learning gains in certain proficiencies, particularly for place value and fractions (Fig. 1 ). Finally, we found high parental engagement: parents became more confident and accurate in their beliefs about their child’s education. Overall, this study shows that instruction through mobile phones can provide an effective, scalable method for education delivery beyond traditional schooling approaches.

The graph shows the effects (in standard deviations) of multiple learning strategies relative to the control (no intervention) group. ‘Average level’ represents results from the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 0 to 4 scale corresponding to no operations (0), addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. ‘Place value’ and ‘fractions’ refer to two types of problem. Each group (such as ‘phone + SMS’) refers to randomized treatment groups pooled across the designated category. ‘Targeted’ refers to children in a subset that received additional targeted instruction on the basis of child-specific learning levels; ‘not targeted’ refers to children within a subgroup that did not receive targeted instruction. © 2022, Angrist, N. et al.

The implications

Our findings have immediate policy relevance as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to disrupt schooling. Even where schools have re-opened, instruction time has often been reduced owing to social distancing measures, such as double-shift systems in which half of the students attend school in the morning and the other half attend in the afternoon.

Providing additional educational instruction out of school is therefore a current priority. More broadly, our findings have implications for the role of simple, low-tech methods to support education during many forms of school disruption, including teacher strikes, summer holidays, public health crises, weather shocks, natural disasters, and in refugee and conflict settings. In moments in which schooling is disrupted, education systems require resilient approaches to continue to provide education.

Despite our trial including a very large sample size, our data are limited to a single context: the COVID-19 pandemic in Botswana. Future research might involve similar trials to assess how well a low-tech learning approach can be adapted across low- and middle-income countries. We are currently engaged in an active research agenda focused on education in emergencies, which includes a multicontext study testing the adaptability and scalability of remote mobile phone education across five countries: India, Kenya, Nepal, the Philippines and Uganda. Finally, it is important to note that our study evaluates only a subset of potential interventions; other low-tech methods of educational instruction, such as radio and TV, require further investigation.

Noam Angrist 1,2

1 University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

2 Youth Impact, Gaborone, Botswana.

Expert opinion

“This is a timely and carefully executed and analysed study. The authors provide evidence of a promising, innovative, replicable, potentially scalable and cost-effective intervention to address the massive educational challenge posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is a valuable contribution to the literature, although it remains unclear whether the observed short-term gains persist or wane further into the future.” Juan E. Saavedra, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Behind the paper

We launched this study within a month of school closures in Botswana, providing some of the first experimental evidence on distance education during the COVID-19 pandemic. This rapid response was enabled by the depth and breadth of presence of Youth Impact in Botswana — an evidence-based nongovernmental organization that provides health and education programmes. Youth Impact provides education services to over 20% of primary schools in the country in partnership with the government, and had experience in running more than 20 rapid randomized trials prior to the pandemic. Our study demonstrates the power of real-time, rigorous evidence to identify effective solutions in a moment of enormous uncertainty and need. The results emerged quickly, were policy-relevant and have been followed by efforts in at least 5 countries reaching over 20,000 students, galvanizing a global and growing evidence base on effective approaches to education in emergencies. N.A.

From the editor

“The challenge of mitigating learning loss during the COVID-19 pandemic is crucial, and this paper by Angrist et al. stands out for its efforts to tackle this problem and test an intervention that could potentially be widely implemented.” Aisha Bradshaw, Senior Editor , Nature Human Behaviour .

Angrist, N., Djankov, S., Goldberg, P. K. & Patrinos, H. A. Measuring human capital using global learning data. Nature 592 , 403–408 (2021). This paper reports evidence of low levels of learning and limited educational progress across 164 countries, a phenomenon that the international education community has called ‘the learning crisis’ .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J. & Greathouse, S. The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: a narrative and meta-analytic review. Rev. Educational Res. 66 , 227–268 (1996). This paper reports learning losses from annual summer vacations — a recurring school closure .

Article Google Scholar

Andrabi, T., Daniels B. & Das J. Human capital accumulation and disasters: evidence from the Pakistan earthquake of 2005. J. Hum. Res . 0520-10887R1 (2021). This paper reports learning losses from an earthquake, a school disruption with long-term ramifications .

Aker, J. C., Ksoll, C. & Lybbert, T. J. Can mobile phones improve learning? Evidence from a field experiment in Niger. Amer. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 4 , 94–120 (2012). This paper demonstrates the potential of education provided via mobile phone for adults in a low-resource setting .

Kremer, M., Brannen, C. & Glennerster, R. The challenge of education and learning in the developing world. Science 340 , 297–300 (2013). This review article summarizes cost-effective and rigorously evaluated interventions in education .

Download references

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This is a summary of: Angrist, N., Bergman, P. & Matsheng, M. Experimental evidence on learning using low-tech when school is out. Nat. Hum. Behav . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01381-z (2022)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Distance education strategies to improve learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Hum Behav 6 , 913–914 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01382-y

Download citation

Published : 15 June 2022

Issue Date : July 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01382-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Mini review article, distance learning in higher education during covid-19.

- 1 Department of Pedagogy of Higher Education, Kazan (Volga Region) Federal University, Kazan, Russia

- 2 Department of Jurisprudence, Bauman Moscow State Technical University, Moscow, Russia

- 3 Department of English for Professional Communication, Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia

- 4 Department of Foreign Languages, RUDN University, Moscow, Russia

- 5 Department of Medical and Social Assessment, Emergency, and Ambulatory Therapy, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia

COVID-19’s pandemic has hastened the expansion of online learning across all levels of education. Countries have pushed to expand their use of distant education and make it mandatory in view of the danger of being unable to resume face-to-face education. The most frequently reported disadvantages are technological challenges and the resulting inability to open the system. Prior to the pandemic, interest in distance learning was burgeoning, as it was a unique style of instruction. The mini-review aims to ascertain students’ attitudes about distant learning during COVID-19. To accomplish the objective, articles were retrieved from the ERIC database. We utilize the search phrases “Distance learning” AND “University” AND “COVID.” We compiled a list of 139 articles. We chose papers with “full text” and “peer reviewed only” sections. Following the exclusion, 58 articles persisted. Then, using content analysis, publications relating to students’ perspectives on distance learning were identified. There were 27 articles in the final list. Students’ perspectives on distant education are classified into four categories: perception and attitudes, advantages of distance learning, disadvantages of distance learning, and challenges for distance learning. In all studies, due of pandemic constraints, online data gathering methods were selected. Surveys and questionnaires were utilized as data collection tools. When students are asked to compare face-to-face and online learning techniques, they assert that online learning has the potential to compensate for any limitations caused by pandemic conditions. Students’ perspectives and degrees of satisfaction range widely, from good to negative. Distance learning is advantageous since it allows for learning at any time and from any location. Distance education benefits both accomplishment and learning. Staying at home is safer and less stressful for students during pandemics. Distance education contributes to a variety of physical and psychological health concerns, including fear, anxiety, stress, and attention problems. Many schools lack enough infrastructure as a result of the pandemic’s rapid transition to online schooling. Future researchers can study what kind of online education methods could be used to eliminate student concerns.

Introduction

The pandemic of COVID-19 has accelerated the spread of online learning at all stages of education, from kindergarten to higher education. Prior to the epidemic, several colleges offered online education. However, as a result of the epidemic, several governments discontinued face-to-face schooling in favor of compulsory distance education.

The COVID-19 problem had a detrimental effect on the world’s educational system. As a result, educational institutions around the world developed a new technique for delivering instructional programs ( Graham et al., 2020 ; Akhmadieva et al., 2021 ; Gaba et al., 2021 ; Insorio and Macandog, 2022 ; Tal et al., 2022 ). Distance education has been the sole choice in the majority of countries throughout this period, and these countries have sought to increase their use of distance education and make it mandatory in light of the risk of not being able to restart face-to-face schooling ( Falode et al., 2020 ; Gonçalves et al., 2020 ; Tugun et al., 2020 ; Altun et al., 2021 ; Valeeva and Kalimullin, 2021 ; Zagkos et al., 2022 ).

What Is Distance Learning

Britannica defines distance learning as “form of education in which the main elements include physical separation of teachers and students during instruction and the use of various technologies to facilitate student-teacher and student-student communication” ( Simonson and Berg, 2016 ). The subject of distant learning has been studied extensively in the fields of pedagogics and psychology for quite some time ( Palatovska et al., 2021 ).

The primary distinction is that early in the history of distant education, the majority of interactions between professors and students were asynchronous. With the advent of the Internet, synchronous work prospects expanded to include anything from chat rooms to videoconferencing services. Additionally, asynchronous material exchange was substantially relocated to digital settings and communication channels ( Virtič et al., 2021 ).

Distance learning is a fundamentally different way to communication as well as a different learning framework. An instructor may not meet with pupils in live broadcasts at all in distance learning, but merely follow them in a chat if required ( Bozkurt and Sharma, 2020 ). Audio podcasts, films, numerous simulators, and online quizzes are just a few of the technological tools available for distance learning. The major aspect of distance learning, on the other hand, is the detailed tracking of a student’s performance, which helps to develop his or her own trajectory. While online learning attempts to replicate classroom learning methods, distant learning employs a computer game format, with new levels available only after the previous ones have been completed ( Bakhov et al., 2021 ).