Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples

Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples

Published on June 20, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

When you start planning a research project, developing research questions and creating a research design , you will have to make various decisions about the type of research you want to do.

There are many ways to categorize different types of research. The words you use to describe your research depend on your discipline and field. In general, though, the form your research design takes will be shaped by:

- The type of knowledge you aim to produce

- The type of data you will collect and analyze

- The sampling methods , timescale and location of the research

This article takes a look at some common distinctions made between different types of research and outlines the key differences between them.

Table of contents

Types of research aims, types of research data, types of sampling, timescale, and location, other interesting articles.

The first thing to consider is what kind of knowledge your research aims to contribute.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The next thing to consider is what type of data you will collect. Each kind of data is associated with a range of specific research methods and procedures.

Finally, you have to consider three closely related questions: how will you select the subjects or participants of the research? When and how often will you collect data from your subjects? And where will the research take place?

Keep in mind that the methods that you choose bring with them different risk factors and types of research bias . Biases aren’t completely avoidable, but can heavily impact the validity and reliability of your findings if left unchecked.

Choosing between all these different research types is part of the process of creating your research design , which determines exactly how your research will be conducted. But the type of research is only the first step: next, you have to make more concrete decisions about your research methods and the details of the study.

Read more about creating a research design

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/types-of-research/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a research design | types, guide & examples, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, what is your plagiarism score.

Mixed Methods Research: The Case for the Pragmatic Researcher

- First Online: 24 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Alistair McBeath 3

2108 Accesses

This chapter presents an introduction to mixed methods research and seeks to emphasise that the approach offers more potential to reveal a deeper understanding of life experiences than the use of either qualitative or quantitative research methods on their own. The history and emergence of mixed methods research are described and also its potential to be aligned with the world view of pragmatism. The fundamental design variants of mixed methods research are presented with reference to supporting research examples. The rationale and advantages of mixed methods are discussed as is the importance of its underlying methodological pluralism which favours the inclusive logic of ‘both/and’ as opposed to the dichotomous logic of ‘either/or’. The chapter concludes with a call for more information about mixed methods to be made available to those with a research interest within counselling and psychotherapy allowing them to discover the wonderful possibilities that are offered by mixed methods research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bager-Charleson, S., & McBeath, A. G. (2021). Containment, compassion and clarity. Mixed methods research into Supervision during Doctoral research for Psychotherapists and Counselling psychologist. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research . doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12498 .

Biddle, C., & Schafft, K. A. (2015). Axiology and anomaly in the practice of mixed methods work: Pragmatism, valuation, and the transformative paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 9 , 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689814533157

Article Google Scholar

Borders, L. D., Wester, K. L., Fickling, M. J., & Adamson, N. A. (2015). Dissertations in CACREP-accredited doctoral programs: An initial investigation. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 7 (3). https://doi.org/10.7729/73.1102

Brannen, J., Dodd, K., Oakley, A., & Storey, P. (1994). Young people, health and family life . Open University Press.

Google Scholar

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11 (4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Brierley, J. A. (2017). The role of a pragmatist paradigm when adopting mixed methods in behavioural accounting research. International Journal of Behavioural Accounting and Finance, 6 (2), 140–154.

Bryman, A. (2006a). Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qualitative Research, 6 (1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106058877

Bryman, A. (2006b). Paradigm Peace and the Implications for Quality. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory & Practice, 9 (2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570600595280

Cade, R., Gibson, S., Swan, K., & Nelson, K. (2018). A content analysis of counseling outcome research and evaluation (CORE) from 2010 to 2017. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 9 (1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2017.1413643

Cameron, R. (2011). Mixed methods research: The five P’s framework. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 9 , 96–108. Retrieved from http://www.ejbrm.com/volume9/issue2/p96

Cameron, R., & Miller, P. (2007) Mixed methods research: Phoenix of the paradigm wars. 21st Annual Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management (ANZAM) Conference, Sydney, December 2007.

Cooper, M., & McLeod, J. (2012). From either/or to both/and: Developing a pluralistic approach to counselling and psychotherapy. European Journal of Psychotherapy and Counselling , 1–13.

Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research . Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Sage.

Denzin, N. (1978). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Etherington, K. (2020). Becoming a narrative inquirer. In S. Bager-Charleson & A. G. McBeath (Eds.), Enjoying research in counselling and psychotherapy (pp. 71–94). Palgrave Macmillan.

Chapter Google Scholar

Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs - Principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48 (6), 2134–2156.

Frost, N., & Bailey-Rodriquez, D. (2020). Doing qualitatively driven mixed methods and pluralistic qualitative research. In S. Bager-Charleson & A. G. McBeath (Eds.), Enjoying research in counselling and psychotherapy (pp. 137–160). Palgrave Macmillan.

Gage, N. L. (1989). The paradigm wars and their aftermath: A “historical” sketch of research on teaching since 1989. Educational Researcher, 18 (7), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/1177163

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11 , 255–274. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737011003255

Grocke, D., Bloch, S., Castle, D., Thompson, G., Newton, R., Stewart, S., & Gold, C. (2014). Group music therapy for severe mental illness: a randomized embedded-experimental mixed methods study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 130 (2), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12224

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2010). Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice . The Guilford Press.

Howe, K. R. (1988). Against the quantitative-qualitative incompatibility thesis or Dogmas Die Hard. Educational Researcher, 17 (8), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/1175845

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33 , 14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033007014

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1 , 112–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806298224

Kaushik, V., & Walsh, C. A. (2019). Pragmatism as a research paradigm and its implications for social work research. Social Sciences, 8 (9), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8090255

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 1065–1122). Sage.

Maarouf, H. (2019). Pragmatism as a supportive paradigm for the mixed research approach: Conceptualizing the ontological, epistemological, and axiological stances of pragmatism. International Business Research, 12 (9), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v12n9p1

Mahalik, J. R. (2014). Both/and, not either/or: A call for methodological pluralism in research on masculinity. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15 (4), 365–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037308

Maxcy, S. J. (2003). Pragmatic threads in mixed method research in the social sciences: The search for multiple modes of inquiry and the end of the philosophy of formalism. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in the social and behavioural sciences (pp. 51–89). Sage.

McBeath, A. G. (2019). The motivations of psychotherapists: An in-depth survey. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19 (4), 377–387.

McBeath, A. G., & Bager-Charleson, S. (2022). Views on mixed methods research in counselling and psychotherapy: An online survey of research students and research supervisors (Manuscript submitted for publication). Metanoia Institute.

McBeath, A. G., Bager-Charleson, S., & Abarbanel, A. (2019). Therapists and Academic Writing: “Once upon a time psychotherapy practitioners and researchers were the same people”. European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy, 19 , 103–116.

Mertens, D. (2007). Transformative paradigm: Mixed methods and social justice. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1 (3), 212–225.

Molina-Azorin, J. F. (2016). Mixed methods research: An opportunity to improve our studies and our research skills. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 25 , 37–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redeen.2016.05.001

Morgan, D. L. (2007). Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: Methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1 , 48–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906292462

Morse, J. M. (1991). Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nursing Research, 40 , 120–123.

Neuman, W. (2014). Social research methods qualitative and quantitative approaches . Pearson.

O’Cathain, A., Murphy, E., & Nicholl, J. (2010). Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. British Medical Journal, 341 , c4587. Retrieved from https://www.bmj.com/content/341/bmj.c4587

Pietkiewicz, I., & Smith, J. A. (2012). Praktyczny przewodnik interpretacyjnej analizy fenomenologicznej w badaniach jakościowych w psychologii. Czasopismo Psychologiczne, 18 (2), 361–369.

Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Qualitative research in counseling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.126

Reichardt, C. S., & Cook, T. D. (1979). Beyond qualitative versus quantitative methods. In T. D. Cook & C. S. Reichardt (Eds.), Qualitative and quantitative methods in evaluation research (pp. 7–32). Sage.

Stafford, M. R. (2020). Understanding randomised control trial design in counselling and psychotherapy. In G. McBeath (Ed.), S. Bager-Charleson & A (pp. 242–265). Enjoying Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (1998). Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches . Sage.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2003). Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research . Sage.

Williams, R. T. (2020). The paradigm wars: Is MMR really a solution? American Journal of Trade and Policy, 7 (3), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.18034/ajtp.v7i3.507

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Metanoia Institute, London, UK

Alistair McBeath

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alistair McBeath .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Sofie Bager-Charleson

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

McBeath, A. (2022). Mixed Methods Research: The Case for the Pragmatic Researcher. In: Bager-Charleson, S., McBeath, A. (eds) Supporting Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy . Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13942-0_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13942-0_10

Published : 24 January 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-13941-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-13942-0

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Serv Res

- v.48(6 Pt 2); 2013 Dec

Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs—Principles and Practices

Michael d fetters.

Family Medicine, University of Michigan, 1018 Fuller St., Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1213

Leslie A Curry

Yale School of Public Health (Health Policy), New Haven, CT

John W Creswell

Educational Psychology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE

Associated Data

Mixed methods research offers powerful tools for investigating complex processes and systems in health and health care. This article describes integration principles and practices at three levels in mixed methods research and provides illustrative examples. Integration at the study design level occurs through three basic mixed method designs—exploratory sequential, explanatory sequential, and convergent—and through four advanced frameworks—multistage, intervention, case study, and participatory. Integration at the methods level occurs through four approaches. In connecting, one database links to the other through sampling. With building, one database informs the data collection approach of the other. When merging, the two databases are brought together for analysis. With embedding, data collection and analysis link at multiple points. Integration at the interpretation and reporting level occurs through narrative, data transformation, and joint display. The fit of integration describes the extent the qualitative and quantitative findings cohere. Understanding these principles and practices of integration can help health services researchers leverage the strengths of mixed methods.

This article examines key integration principles and practices in mixed methods research. It begins with the role of mixed methods in health services research and the rationale for integration. Next, a series of principles describe how integration occurs at the study design level, the method level, and the interpretation and reporting level. After considering the “fit” of integrated qualitative and quantitative data, the article ends with two examples of mixed methods investigations to illustrate integration practices.

Health services research includes investigation of complex, multilevel processes, and systems that may require both quantitative and qualitative forms of data (Creswell, Fetters, and Ivankova 2004 ; Curry et al. 2013 ). The nature of the research question drives the choice of methods. Health services researchers use quantitative methodologies to address research questions about causality, generalizability, or magnitude of effects. Qualitative methodologies are applied to research questions to explore why or how a phenomenon occurs, to develop a theory, or to describe the nature of an individual's experience. Mixed methods research studies draw upon the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative approaches and provides an innovative approach for addressing contemporary issues in health services. As one indication of the growing interest in mixed methods research, the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences at the National Institutes of Health recently developed for researchers and grant reviewers the first best practices guideline on mixed methods research from the National Institutes of Health (Creswell et al. 2011 ).

Rationale for Integration

The integration of quantitative and qualitative data can dramatically enhance the value of mixed methods research (Bryman 2006 ; Creswell and Plano Clark 2011 ). Several advantages can accrue from integrating the two forms of data. The qualitative data can be used to assess the validity of quantitative findings. Quantitative data can also be used to help generate the qualitative sample or explain findings from the qualitative data. Qualitative inquiry can inform development or refinement of quantitative instruments or interventions, or generate hypotheses in the qualitative component for testing in the quantitative component (O'Cathain, Murphy, and Nicholl 2010 ). Although there are many potential gains from data integration, the extent to which mixed methods studies implement integration remains limited (Bryman 2006 ; Lewin, Glenton, and Oxman 2009 ). Nevertheless, there are specific approaches to integrate qualitative and quantitative research procedures and data (O'Cathain, Murphy, and Nicholl 2010 ; Creswell and Plano Clark 2011 ). These approaches can be implemented at the design, methods, and interpretation and reporting levels of research (see Table Table1 1 ).

Levels of Integration in Mixed Methods Research

Integration at the design level—the conceptualization of a study—can be accomplished through three basic designs and four advanced mixed methods frameworks that incorporate one of the basic designs. Basic designs include (1) exploratory sequential; (2) explanatory sequential; and (3) convergent designs. In sequential designs, the intent is to have one phase of the mixed methods study build on the other, whereas in the convergent designs the intent is to merge the phases in order that the quantitative and qualitative results can be compared.

In an exploratory sequential design , the researcher first collects and analyzes qualitative data, and these findings inform subsequent quantitative data collection (Onwuegbuzie, Bustamante, and Nelson 2010 ). For example, Wallace and colleagues conducted semistructured interviews with medical students, residents, and faculty about computing devices in medical education and used the qualitative data to identify key concepts subsequently measured in an online survey (Wallace, Clark, and White 2012 ).

In an explanatory sequential design , the researcher first collects and analyzes quantitative data, then the findings inform qualitative data collection and analysis (Ivankova, Creswell, and Stick 2006 ). For example, Carr explored the impact of pain on patient outcomes following surgery by conducting initial surveys about anxiety, depression, and pain that were followed by semistructured interviews to explore further these concepts (Carr 2000 ).

In a convergent design (sometimes referred to as a concurrent design), the qualitative and quantitative data are collected and analyzed during a similar timeframe. During this timeframe, an interactive approach may be used where iteratively data collection and analysis drives changes in the data collection procedures. For example, initial quantitative findings may influence the focus and kinds of qualitative data that are being collected or vice versa. For example, in one study Crabtree and colleagues used qualitative findings and quantitative findings iteratively in multiple phases such that the data were interacting to inform the final results (Crabtree et al. 2005 ). In the more common and technically simpler variation, qualitative and quantitative data collection occurs in parallel and analysis for integration begins well after the data collection process has proceeded or has been completed. Frequently, the two forms of data are analyzed separately and then merged. For example, Saint Arnault and colleagues conducted multiple surveys using standardized and culturally adapted instruments as well as ethnographic qualitative interviews to investigate how the illness experience, cultural interpretations, and social structural factors interact to influence help-seeking among Japanese women (Saint Arnault and Fetters 2011 ).

Advanced frameworks encompass adding to one of the three basic designs a larger framework that incorporates the basic design. The larger framework may involve (1) a multistage; (2) an intervention; (3) a case study; or (4) a participatory research framework.

In a multistage mixed methods framework , researchers use multiple stages of data collection that may include various combinations of exploratory sequential, explanatory sequential, and convergent approaches (Nastasi et al. 2007 ). By definition, such investigations will have multiple stages, defined here as three or more stages when there is a sequential component, or two or more stages when there is a convergent component; these differences distinguishes the multistage framework from the basic mixed methods designs. This type of framework may be used in longitudinal studies focused on evaluating the design, implementation, and assessment of a program or intervention. Krumholz and colleagues have used this design in large-scale outcomes research studies (Krumholz, Curry, and Bradley 2011 ). For example, a study by their team examining quality of hospital care for patients after heart attacks consisted of three phases: first, a quantitative analysis of risk-standardized mortality rates for patients with heart attacks to identify high and low performing hospitals; second, a qualitative phase to understand the processes, structures, and organizational environments of a purposeful sample of low and high performers and to generate hypotheses about factors associated with performance; and third, primary data collection through surveys of a nationally representative sample of hospitals to test these hypotheses quantitatively (Curry et al. 2011 ; Bradley et al. 2012 ). Ruffin and colleagues conducted a multistage mixed methods study to develop and test in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) a website to help users choose a screening approach to colorectal cancer. In the first stage, the authors employed a convergent design using focus groups and a survey (Ruffin et al. 2009 ). In the second stage, they developed the website based on multiple qualitative approaches (Fetters et al. 2004 ). In the third stage, the authors tested the website in an RCT to assess its effectiveness (Ruffin, Fetters, and Jimbo 2007 ). The multistage framework is the most general framework among advanced designs. The additional three frameworks frequently involve multiple stages or phases but differ from multistage by having a particular focus.

In an intervention mixed methods framework , the focus is on conducting a mixed methods intervention. Qualitative data are collected primarily to support the development of the intervention, to understand contextual factors during the intervention that could affect the outcome, and/or explain results after the intervention is completed (Creswell et al. 2009 ; Lewin, Glenton, and Oxman 2009 ). For example, Plano Clark and colleagues utilized data from a pretrial qualitative study to inform the design of a trial developed to compare a low dose and high dose behavioral intervention to improve cancer pain management—the trial also included prospective qualitative data collection during the trial (Plano Clark et al. 2013 ). The methodological approach for integrating qualitative data into an intervention pretrial, during the trial, or post-trial is called embedding (see below), and some authors refer to such trials as embedded designs (Creswell et al. 2009 ; Lewin, Glenton, and Oxman 2009 ).

In a case study framework , both qualitative and quantitative data are collected to build a comprehensive understanding of a case, the focus of the study (Yin 1984 ; Stake 1995 ). Case study involves intensive and detailed qualitative and quantitative data collection about the case (Luck, Jackson, and Usher 2006 ). The types of qualitative and quantitative data collected are chosen based on the nature of the case, feasibility issues, and the research question(s). In one mixed methods case study, Luck and colleagues utilized qualitative data from participant observation, semistructured interviews, informal field interviews and journaling, and quantitative data about violent events collected through structured observations to understand why nurses under-report violence in the workplace and describe how they handle it (Luck, Jackson, and Usher 2008 ). Comparative case studies are an extension of this framework and can be formulated in various ways. For example, Crabtree and colleagues used a comparative case approach to examine the delivery of clinical preventive services in family medicine offices (Crabtree et al. 2005 ).

In a participatory framework , the focus is on involving the voices of the targeted population in the research to inform the direction of the research. Often researchers specifically seek to address inequity, health disparities, or a social injustice through empowering marginalized or underrepresented populations. The distinguishing feature of a participatory framework is the strong emphasis on using mixed methods data collection through combinations of basic mixed methods designs or even another advanced design, for example, an intervention framework such as an RCT. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a participatory framework that focuses on social, structural, and physical environmental inequities and engages community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process (Macaulay et al. 1999 ; Israel et al. 2001 , 2013 ; Minkler and Wallerstein 2008 ). In one CBPR project, Johnson and colleagues used a mixed methods CBPR approach to collaborate with the Somali community to explore how attitudes, perceptions, and cultural practices such as female genital cutting influence their use of reproductive health services—this informed the development of interventional programs to improve culturally competent care (Johnson, Ali, and Shipp 2009 ). A similar variation involving an emerging participatory approach that Mertens refers to as transformative specifically focuses on promoting social justice (Mertens 2009 , 2012 ) and has been used with Laotian refugees (Silka 2009 ).

Creswell and Plano Clark conceptualize integration to occur through linking the methods of data collection and analysis (Creswell et al. 2011 ). Linking occurs in several ways: (1) connecting; (2) building; (3) merging; and (4) embedding (Table (Table2). 2 ). In a single line of inquiry, integration may occur through one or more of these approaches.

Integration through Methods

Integration through connecting occurs when one type of data links with the other through the sampling frame . For example, consider a study with a survey and qualitative interviews. The interview participants are selected from the population of participants who responded to the survey. Connecting can occur through sampling regardless of whether the design is explanatory sequential or convergent. That is, if the baseline survey data are analyzed, and then the participants sampled based on findings from the analysis, then the design is explanatory sequential. In contrast, the design is convergent if the data collection and analyses occur at the same time for the baseline survey and interviews of all or a subsample of the participants of the survey. A key defining factor in sequential or convergent is how the analysis occurs, either through building or merging, respectively.

Integration through building occurs when results from one data collection procedure informs the data collection approach of the other procedure, the latter building on the former. Items for inclusion in a survey are built upon previously collected qualitative data that generate hypotheses or identify constructs or language used by research participants. For example, in a project involving the cultural adaptation of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey for use in the Arabian Gulf (Hammoud et al. 2012 ), baseline qualitative interviews identified new domains of importance such as gender relations, diet, and interpreter use not found in the existing CAHPS instrument. In addition, phrases participants used during the interviews informed the wording of individual items.

Integration through merging of data occurs when researchers bring the two databases together for analysis and for comparison . Ideally, at the design phase, researchers develop a plan for collecting both forms of data in a way that will be conducive to merging the databases. For example, if quantitative data are collected with an instrument with a series of scales, qualitative data can be collected using parallel or similar questions (Castro et al. 2010 ). Merging typically occurs after the statistical analysis of the numerical data and qualitative analysis of the textual data. For example, in a multistage mixed methods study, Tomoaia-Cortisel and colleagues used multiple sources of existing quantitative and qualitative data as well as newly collected quantitative and qualitative data (Tomoaia-Cortisel et al. 2013 ). The researchers examined the relationship between quality of care according to key patient-centered medical home (PCMH) measures, and quantity of care using a productivity measure. By merging both scores of quality and quantity, with qualitative data from interviews, the authors illuminated the difficulty of achieving highly on both PCMH quality measures and productivity. The authors extended this understanding further by merging staff satisfaction scores and staff interview data to illustrate the greater work complexity but lower satisfaction for staff achieving measures for high-quality care (Tomoaia-Cortisel et al. 2013 ).

Integration through embedding occurs when data collection and analysis are being linked at multiple points and is especially important in interventional advanced designs, but it can also occur in other designs. Embedding may involve any combination of connecting, building, or merging, but the hallmark is recurrently linking qualitative data collection to quantitative data collection at multiple points. Embedding may occur in the pretrial period, when qualitative (or even a combination of qualitative and quantitative) data can be used in various ways such as clarifying outcome measures, understanding contextual factors that could lead to bias and should be controlled for, or for developing measurement tools to be utilized during the trial. During the trial, qualitative data collection can be used to understand contextual factors that could influence the trial results or provide detailed information about the nature of the experience of subjects. Post-trial qualitative data collection can be used to explain outliers, debrief subjects or researchers about events or experiences that occurred during the trial, or develop hypotheses about changes that might be necessary for widespread implementation outside of a controlled research environment. Such studies require caution to avoid threatening the validity of the trial design. In a site-level controlled trial of a quality improvement approach for implementing evidence-based employment services for patients at specialty mental health clinics, Hamilton and colleagues collected semistructured interview data before, during, and after implementation (Hamilton et al. 2013 ). In another interesting example, Jaen and colleagues used an embedded approach for evaluating practice change in a trial comparing facilitated and self-directed implementation strategies for PCMH. The authors use both embedded quantitative and qualitative evaluation procedures including medical record audit, patient and staff surveys, direct observation, interviews, and text review (Jaen et al. 2010 ).

Method level integration commonly relates to the type of design used in a study. For example, connecting follows naturally in sequential designs, while merging can occur in any design. Embedding generally occurs in an interventional design. Thus, the design sets parameters for what methodological integration choices can be made.

Integration of qualitative and quantitative data at the interpretation and reporting level occurs through three approaches: (1) integrating through narrative; (2) integrating through data transformation; and (3) integrating through joint displays. A variety of strategies have been offered for publishing that incorporate these approaches (Stange, Crabtree, and Miller 2006 ; Creswell and Tashakkori 2007 ).

When integrating through narrative , researchers describe the qualitative and quantitative findings in a single or series of reports. There are three approaches to integration through narrative in research reports. The weaving approach involves writing both qualitative and quantitative findings together on a theme-by-theme or concept-by-concept basis. For example, in their work on vehicle crashes among the elderly, Classen and colleagues used a weaving approach to integrate results from a national crash dataset and perspectives of stakeholders to summarize causative factors of vehicle crashes and develop empirical guidelines for public health interventions (Classen et al. 2007 ). The contiguous approach to integration involves the presentation of findings within a single report, but the qualitative and quantitative findings are reported in different sections. For example, Carr and colleagues reported survey findings in the first half of the results section and the qualitative results about contextual factors in a subsequent part of the report (Carr 2000 ). In their study of a quality improvement approach for implementing evidence-based employment services at specialty mental health clinics, Hamilton and colleagues used this approach but differ by presenting the qualitative results first and the quantitative results second (Hamilton et al. 2013 ). The staged approach to integration often occurs in multistage mixed methods studies when the results of each step are reported in stages as the data are analyzed and published separately. For example, Wilson and colleagues used an intervention mixed methods framework involving a clinical trial of usual care, nicotine gum, and gum plus counseling on smoking cessation (Wilson et al. 1988 ). They also used interviews to find the meaning patients attributed to their stopping smoking (Willms 1991 ). The authors published the papers separately but in the second published paper, the interview paper, they only briefly mention the original clinical trial paper.

Integration through data transformation happens in two steps. First, one type of data must be converted into the other type of data (i.e., qualitative into quantitative or quantitative into qualitative). Second, the transformed data are then integrated with the data that have not been transformed. In qualitative studies, researchers sometimes code the qualitative data and then count the frequency of codes or domains identified, a process known also as content analysis (Krippendorff 2013 ). Data transformation in the mixed methods context refers to transforming the qualitative data into numeric counts and variables using content analysis so that the data can be integrated with a quantitative database. Merging in mixed methods goes beyond content analysis by comparing the transformed qualitative data with a quantitative database. Zickmund and colleagues used qualitatively elicited patient views of self transformed to a numerical variable, and mortality data to conduct hierarchical multivariable logistical modeling (Zickmund et al. 2013 ).

Researchers have used additional variations. Qualitative data can be transformed to quantitative data, then integrated with illustrative examples from the original qualitative dataset. For example, Ruffin and colleagues transformed qualitative responses from focus group data about colorectal cancer (CRC) screening preferences into quantitative variables, and then integrated these findings with representative quotations from three different constituencies (Ruffin et al. 2009 ). Quantitative data can also be transformed into a qualitative format that could be used for comparison with qualitatively accessed data. For example, Pluye and colleagues examined a series of study outcomes with variable strengths of association that were converted into qualitative levels and compared across the studies based on patterns found (Pluye et al. 2005 ).

When integrating through joint displays , researchers integrate the data by bringing the data together through a visual means to draw out new insights beyond the information gained from the separate quantitative and qualitative results. This can occur through organizing related data in a figure, table, matrix, or graph. In their quality improvement study to enhance colorectal cancer screening in practices, Shaw and colleagues collocated a series of qualitatively identified factors with CRC screening rates at baseline and 12 months later (Shaw et al. 2013 ).

When using any of these analytical and representation procedures, a potential question of coherence of the quantitative and qualitative findings may occur. The “fit” of data integration refers to coherence of the quantitative and qualitative findings. The assessment of fit of integration leads to three possible outcomes. Confirmation occurs when the findings from both types of data confirm the results of the other. As the two data sources provide similar conclusions, the results have greater credibility. Expansion occurs when the findings from the two sources of data diverge and expand insights of the phenomenon of interest by addressing different aspects of a single phenomenon or by describing complementary aspects of a central phenomenon of interest. For example, quantitative data may speak to the strength of associations while qualitative data may speak to the nature of those associations. Discordance occurs if the qualitative and quantitative findings are inconsistent, incongruous, contradict, conflict, or disagree with each other. Options for reporting the findings include looking for potential sources of bias, and examining methodological assumptions and procedures. Investigators may handle discordant results in different ways such as gathering additional data, re-analyzing existing databases to resolve differences, seeking explanations from theory, or challenging the validity of the constructs. Further analysis may occur with the existing databases or in follow-up studies. Authors deal with this conundrum by discussing reasons for the conflicting results, identifying potential explanations from theory, and laying out future research options (Pluye et al. 2005 ; Moffatt et al. 2006 ).

Below, two examples of mixed methods illustrate the integration practices. The first study used an exploratory sequential mixed methods design (Curry et al. 2011 ) and the second used a convergent mixed methods design (Meurer et al. 2012 ).

Example 1. Integration in an Exploratory Sequential Mixed Methods Study—The Survival after Acute Myocardial Infarction Study (American College of Cardiology 2013 )

Despite more than a decade of efforts to improve care for patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), there remains substantial variation across hospitals in mortality rates for patients with AMI (Krumholz et al. 2009 ; Popescu et al. 2009 ). Yet the vast majority of this variation remains unexplained (Bradley et al. 2012 ), and little is known about how hospitals achieve reductions in risk-standardized mortality rates (RSMRs) for patients with AMI. This study sought to understand diverse and complex aspects of AMI care including hospital structures (e.g., emergency department space), processes (e.g., emergency response protocols, coordination within hospital units), and hospital internal environments (e.g., organizational culture).

Integration through design . An exploratory sequential mixed methods design using both qualitative and quantitative approaches was best suited to gain a comprehensive understanding of how these features may be related to quality of AMI care as reflected in RSMRs. The 4-year investigation aimed to first generate and then empirically test hypotheses concerning hospital-based efforts that may be associated with lower RSMRs (Figure (Figure1 1 ).

Example Illustrating Integration in an Exploratory Sequential Mixed Methods Design from the Survival after Acute Myocardial Infarction Study

Integration through methods . The first phase was a qualitative study of acute care hospitals in the United States (Curry et al. 2011 ). Methodological integration occurred through connecting as the 11 hospitals in the purposeful sample ranked in either the top 5 percent or bottom 5 percent of RSMRs for each of the two most recent years of data (2005–2006, 2006–2007) from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The qualitative data from 158 key staff interviews informed the generation of hypotheses regarding factors potentially associated with better performance (see Table Table3) 3 ) (Curry et al. 2011 ). These hypotheses were used to build an online quantitative survey that was administered in a cross-sectional study of 537 acute care hospitals (91 percent response rate) (Curry et al. 2011 ; Krumholz, Curry, and Bradley 2011 ; Bradley et al. 2012 ).

Examples of How the Qualitative Data Were Used to Build Quantitative Survey Items in the Survival after Acute Myocardial Infarction Study

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CEO, chief executive officer. Adapted with permission from Bradley, Curry et al., Annals of Internal Medicine , May 1, 2012.

Mixed methods were used to characterize the care practices and processes in higher performing organizations as well as the organizational environment where they were implemented. Figure Figure1 1 illustrates points in the process of integration. In Aim 1, the qualitative component connected with the CMS database in order to identify a positive deviance sample. The investigators conducted a systematic analysis of the qualitative data using a multidisciplinary team. This provided (point 1, Figure 1 ) a rich characterization of prominent themes that distinguished higher-performing from lower-performing hospitals and generated hypotheses regarding factors influencing AMI mortality rates (Curry et al. 2011 ). In Aim 2, the investigators built a 68 item-survey from the qualitative data. Key concepts from the qualitative data (point 2, Figure 1 ) were operationalized as quantitative items for inclusion in a web-based survey in order to test the hypotheses statistically in a nationally representative sample of hospitals (Bradley et al. 2012 ). The authors analyzed the quantitative survey data and then merged the quantitative findings (point 3, Figure 1 ) and qualitative analysis (point 4, Figure 1 ) in a single paper. The merging of the qualitative and quantitative produced a comprehensive, multifaceted description of factors influencing RSMRs as well as the impact of these factors on RSMRs that was presented using a weaving narrative . For example, problem-solving and learning was a prominent theme that differentiated higher-performing from lower-performing hospitals. In higher-performing hospitals, adverse events were perceived as opportunities for learning and improvement, approaches to data feedback were nonpunitive, innovation and creativity were valued and supported, and new ideas were sought. In the multivariable analysis, having an organizational environment where clinicians are encouraged to creatively solve problems was significantly associated with lower RSMRs (0.84 percentage points). Finally, additional analyses of qualitative data examining organizational features related to high-quality discharge planning (point 5, Figure Figure1) 1 ) (Cherlin et al. 2013 ), and examining collaborations with emergency medical services (point 6, Figure Figure1) 1 ) (Landman et al. 2013 ) were also methodologically connected through sampling of high-performing hospitals in the CMS database.

Integration through Interpretation and Reporting . The authors used primarily a staged narrative approach for reporting their results. The process and outcomes of integration of qualitative and quantitative data were primarily described in the quantitative paper (Bradley et al. 2012 ). The qualitative data informed the development of domains and concepts for a quantitative survey. Mapping of all survey items to corresponding concepts from the qualitative findings was reported in a web appendix of the published article. In the presentation of results from the multivariate model, multiple strategies that had significant associations with RSMRs were reported, with a summary of how these strategies corresponded to five of the six domains from the qualitative component. Quantitative and qualitative findings were synthesized through narrative both in the results and discussion using weaving . Key aspects of the organizational environment included effective communication and collaboration among groups, broad staff presence, and expertise. A culture of problem solving and learning were apparent in the qualitative findings and statistically associated with higher RSMRs in the quantitative findings. Regarding fit , the quantitative findings (Bradley et al. 2012 ) primarily confirmed the qualitative findings (Curry et al. 2011 ). Thus, higher performing hospitals were not distinguished by specific practices, but instead by organizational environments that could foster higher quality care. An accompanying editorial (Davidoff 2012 ) discusses the complementary relationship between the qualitative and quantitative findings, highlighting again the respective purposes of each component. The additional qualitative analyses were published separately (Cherlin et al. 2013 ; Landman et al. 2013 ) and illustrate staged approach to reporting through narrative with ample referencing to the previous studies. This example also illustrates expansion of the previously published findings (Stange, Crabtree, and Miller 2006 ).

Example 2. Integration in a Convergent Mixed Methods Study—The Adaptive Designs Accelerating Promising Trials into Treatments (ADAPT-IT) Study

The RCT is considered by many trialists to be the gold standard of evidence. Adaptive clinical trials (ACTs) have been developed as innovative trials with potential benefits over traditional trials. However, controversy remains regarding assumptions made in ACTs and the validity of results (Berry 2011 ). Adaptive designs comprise a spectrum of potential trial design changes (Meurer et al. 2012 ). A simple adaptation involves early trial termination rules based on statistical boundaries (Pocock 1977 ), while a complex adaptation in a dose-finding trial could identify promising treatments for specific subpopulations and tailor enrollment to maximize information gained (Yee et al. 2012 ). The overarching objective of ADAPT-IT is “To illustrate and explore how best to use adaptive clinical trial designs to improve the evaluation of drugs and medical devices and to use mixed methods to characterize and understand the beliefs, opinions, and concerns of key stakeholders during and after the development process”(Meurer et al. 2012 ).

Integration through design . One study from the mixed methods evaluation aim of the investigation seeks to describe and compare the beliefs and perspectives of key stakeholders in the clinical trial enterprise about potential ethical advantages and disadvantages of ACT approaches. A mixed methods convergent design was utilized to collect quantitative data through a 22-item ACTs beliefs survey using questions with a 100-point visual analog scale, and qualitative data from unstructured open-response questions on the survey and mini focus group interviews. The scales on the survey instrument assessed beliefs about ethical advantages and disadvantages of adaptive designs from the patient, research, and societal perspectives. The qualitative questions on the survey and in the interview guides elicited why participants feel there are advantages or disadvantages to using adaptive designs. A mixed methods approach was implemented to elucidate participants’ beliefs, to identify the reasoning behind the beliefs expressed, and to integrate the data together to provide the broadest possible understanding. Fifty-three individuals participated from the four stakeholder groups: academic clinicians ( n = 22); academic biostatisticians ( n = 5); consultant biostatisticians ( n = 6); and other stakeholders, including FDA and NIH personnel and patient advocates ( n = 20).

Integration through methods . The quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently, and the approach to integration involved merging . With the content of the scales on the survey in mind, the mixed methods team developed the open-ended responses on the survey and interview questions for mini focus groups to parallel visual analog scale (VAS) questions about ethical advantages and disadvantages. By making this choice intentionally during the design, integration through merging would naturally follow. The research team conducted separate analyses of the quantitative and qualitative data in parallel . For the quantitative analytics, the team calculated descriptive statistics, mean scores, and standard deviations across the four stakeholder groups. Box plots of the data by group were developed to allow intra- and intergroup comparisons. For the qualitative analytics, the investigators immersed themselves in the qualitative database, developed a coding scheme, and conducted thematic searches using the codes. Since the items on the VASs and the questions on the qualitative interview guides were developed in tandem, the codes in the coding scheme were similarly developed based on the items on the scales and the interview questions. As additional themes emerged, codes to capture these were added. The methodological procedures facilitated thematic searches of the text database about perceived ethical advantages and disadvantages that could be matched and merged with the scaled data on beliefs about ethical advantages and disadvantages.

Integration through Interpretation and Reporting Procedures . Having organized the quantitative and the qualitative data in a format based on thematic relevance to allow merging , higher order integration interpretation was needed. Two approaches were used. First the results from the quantitative and qualitative data were integrated using a joint display. As illustrated in Figure Figure2, 2 , the left provides the participants’ quantitative ratings of their beliefs about the ethical advantages as derived from the visual analog scales, with the lowest anchor of 0 signifying definitely not agreeing with the statement and the highest anchor of 100 signifying definite agreement with the statement. The right side provides illustrative qualitative data from the free-text responses on the survey and the mini focus groups. Color matching (see online version) of the box plots and text responses was devised to help the team match visually the quantitative and qualitative responses from the constituent groups. Multiple steps in developing the joint display contributed to an interpretation of the data.

Example of Joint Display Illustrating Integration at the Interpretation and Reporting Level from the ADAPT-IT Project—Potential Ethical Advantages for Patients When Using Adaptive Clinical Trial Designs

In the final report, the quantitative data integration uses a narrative approach that describes the quantitative and qualitative results thematically. The specific type of narrative integration is weaving because the results are connected to each other thematically, and the qualitative and quantitative data weave back and forth around similar themes or concepts. The narrative provides intragroup comparisons of the results from the scales about beliefs that are supported by text from the qualitative database. Each of the six sections of the results contain quantitative scores with intergroup comparisons among the four groups studied, that is, academic researchers, academic biostatisticians, consultant biostatisticians, and “other” stakeholders and quotations from each group.

Regarding the fit of the quantitative and qualitative data, the integration resulted in an expansion of understanding. The qualitative comments provided information about the spectrum of opinions about ethical advantages and disadvantages, but the scales in particular were illustrative showing there was polarization of opinion about these issues among two of the constituencies.

This article provides an update on mixed methods designs and principles and practices for achieving integration at the design, methods, and interpretation and reporting levels. Mixed methodology offers a new framework for thinking about health services research with substantial potential to generate unique insights into multifaceted phenomena related to health care quality, access, and delivery. When research questions would benefit from a mixed methods approach, researchers need to make careful choices for integration procedures. Due attention to integration at the design, method, and interpretation and reporting levels can enhance the quality of mixed methods health services research and generate rigorous evidence that matters to patients.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement : At the invitation of Helen I. Meissner, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, an earlier version of this article was presented for the NIH-OBSSR Workshop, “Using Mixed Methods to Optimize Dissemination and Implementation of Health Interventions,” Natcher Conference Center, NIH Campus, Bethesda, MD, May 3, 2012. Beth Ragle assisted with entry of references and formatting. Dr. Fetters acknowledges the other members of the ADAPT-IT project's Mixed Methods team, Laurie J. Legocki, William J. Meurer, and Shirley Frederiksen, for their contributions to the development of Figure 2 .

Disclosures : None.

Disclaimers : None.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

- American College of Cardiology. 2013. “Surviving MI Intiative” [accessed on May 12, 2013]. Available at http://www.cardiosource.org/Science-And-Quality/Quality-Programs/Surviving-MI-Initiative.aspx .

- Berry DA. “Adaptive Clinical Trials: The Promise and the Caution” Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011; 29 (6):606–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Spatz ES, Herrin J, Cherlin EJ, Curtis JP, Thompson JW, Ting HH, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. “Hospital Strategies for Reducing Risk-Standardized Mortality Rates in Acute Myocardial Infarction” Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012; 156 (9):618–26. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bryman A. “Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Research: How Is It Done?” Qualitative Inquiry. 2006; 6 (1):97–113. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carr E. “Exploring the Effect of Postoperative Pain on Patient Outcomes Following Surgery” Acute Pain. 2000; 3 (4):183–93. [ Google Scholar ]

- Castro FG, Kellison JG, Boyd SJ, Kopak A. “A Methodology for Conducting Integrative Mixed Methods Research and Data Analyses” Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2010; 4 (4):342–60. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cherlin EJ, Curry LA, Thompson JW, Greysen SR, Spatz E, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. “Features of High Quality Discharge Planning for Patients Following Acute Myocardial Infarction” Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013; 28 (3):436–43. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Classen S, Lopez ED, Winter S, Awadzi KD, Ferree N, Garvan CW. “Population-Based Health Promotion Perspective for Older Driver Safety: Conceptual Framework to Intervention Plan” Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2007; 2 (4):677–93. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Tallia AF, Cohen DJ, DiCicco-Bloom B, McIlvain HE, Aita VA, Scott JG, Gregory PB, Stange KC, McDaniel RR., Jr “Delivery of Clinical Preventive Services in Family Medicine Offices” Annals of Family Medicine. 2005; 3 (5):430–5. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell JW, Fetters MD, Ivankova NV. “Designing a Mixed Methods Study in Primary Care” Annals of Family Medicine. 2004; 2 (1):7–12. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell JW, Tashakkori A. “Editorial: Developing Publishable Mixed Methods Manuscripts” Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007; 1 (107):106–11. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell JW, Fetters MD, Plano Clark VL, Morales A. “Mixed Methods Intervention Trials” In: Andrew S, Halcomb E, editors. Mixed Methods Research for Nursing and the Health Sciences. Chichester, West Sussex; Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing; 2009. pp. 161–80. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, Smith KC, Working Group Assistance . Washington, DC: Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR), National Institutes of Health (NIH); 2011. “Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences” p. 27. H. I. Meissner. [ Google Scholar ]

- Curry LA, Spatz E, Cherlin E, Thompson JW, Berg D, Ting HH, Decker C, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. “What Distinguishes Top-Performing Hospitals in Acute Myocardial Infarction Mortality Rates? A Qualitative Study” Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011; 154 (6):384–90. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Curry L, Krumholz HM, O'Cathain A, Plano Clark V, Cherlin E, Bradley EH. “Mixed Methods in Biomedical and Health Services Research” Circulation. 2013; 6 (1):119–23. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davidoff F. “Is Every Defect Really a Treasure?” Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012; 156 (9):664–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fetters MD, Ivankova NV, Ruffin MT, Creswell JW, Power D. “Developing a Web Site in Primary Care” Family Medicine. 2004; 36 (9):651–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hamilton A, Cohen A, Glover D, Whelan F, Chemerinski E, McNagny KP, Mullins D, Reist C, Schubert M, Young AS. “Implementation of Evidence-Based Employment Services in Specialty Mental Health: Mixed Methods Research” Health Services Research. 2013; 48 (S2):2224–44. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hammoud MM, Elnashar M, Abdelrahim H, Khidir A, Elliott HAK, Killawi A, Padela AI, Al Khal AL, Bener A, Fetters MD. “Challenges and Opportunities of US and Arab Collaborations in Health Services Research: A Case Study from Qatar” Global Journal of Health Science. 2012; 4 (6):148–59. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. “Community-Based Participatory Research: Policy Recommendations for Promoting a Partnership Approach in Health Research” Education for Health. 2001; 14 (2):182–97. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker E. Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ivankova NV, Creswell JW, Stick S. “Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice” Field Methods. 2006; 18 (1):3–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jaen CR, Crabtree BF, Palmer RF, Ferrer RL, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stewart EE, Wood R, Davila M, Stange KC. “Methods for Evaluating Practice Change Toward a Patient-Centered Medical Home” Annals of Family Medicine. 2010; 8 (Suppl 1):S9–20. S92. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson CE, Ali SA, Shipp MPL. “Building Comunity-Based Participatory Research Partnerships with a Somali Refugee Community” American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009; 37 (6S1):S230–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Krumholz HM, Curry LA, Bradley EH. “Survival after Acute Myocardial Infarction (SAMI) Study: The Design and Implementation of a Positive Deviance Study” American Heart Journal. 2011; 162 (6):981–7. e9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krumholz HM, Merrill AR, Schone EM, Schreiner GC, Chen J, Bradley EH, Wang Y, Lin Z, Straube BM, Rapp MT, Normand SL, Drye EE. “Patterns of Hospital Performance in Acute Myocardial Infarction and Heart Failure 30-Day Mortality and Readmission” Circulation. 2009; 2 (5):407–13. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Landman AB, Spatz ES, Cherlin EJ, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH, Curry LA. “Hospital Collaboration with Emergency Medical Services in the Care of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: Perspectives from Key Hospital Staff” Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2013; 61 (2):185–95. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewin S, Glenton C, Oxman AD. “Use of Qualitative Methods Alongside Randomised Controlled Trials of Complex Healthcare Interventions: Methodological Study” British Medical Journal. 2009; 339 :b3496. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luck L, Jackson D, Usher K. “Case Study: A Bridge across the Paradigms” Nursing Inquiry. 2006; 13 (2):103–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Usher K. “Innocent or Culpable? Meanings that Emergency Department Nurses Ascribe to Individual Acts of Violence” Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008; 17 (8):1071–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Macaulay AC, Commanda LE, Freeman WL, Gibson N, McCabe ML, Robbins CM, Twohig PL. “Participatory Research Maximises Community and Lay Involvement” British Medical Journal. 1999; 319 (7212):774–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mertens DM. Transformative Research and Evaluation. New York: The Guilford Press; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mertens DM. “Transformative Mixed Methods: Addressing Inequities” American Behavioral Scientist. 2012; 56 (6):802–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Meurer WJ, Lewis RJ, Tagle D, Fetters M, Legocki L, Berry S, Connor J, Durkalski V, Elm J, Zhao W, Frederiksen S, Silbergleit R, Palesch Y, Berry DA, Barsan WG. “An Overview of the Adaptive Designs Accelerating Promising Trials Into Treatments (ADAPT_IT) Project” Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2012; 60 (4):451–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moffatt S, White M, Mackintosh J, Howel D. “Using Quantitative and Qualitative Data in Health Services Research—What Happens When Mixed Methods Findings Conflict?” BMC Health Services Research. 2006; 6 (28):1–10. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nastasi BK, Hitchcock J, Sarkar S, Burkholder G, Varjas K, Jayasena A. “Mixed Methods in Intervention Research: Theory to Adaptation” Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007; 1 (2):164–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. “Three Techniques for Integrating Data in Mixed Methods Studies” British Medical Journal. 2010; 341 :c4587. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Bustamante RM, Nelson JA. “Mixed Research as a Tool for Developing Quantitative Instruments” Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2010; 4 (1):56–78. [ Google Scholar ]

- Plano Clark VL, Schumacher K, West C, Edrington J, Dunn LB, Harzstark A, Melisko M, Rabow MW, Swift PS, Miaskowski C. “Practices for Embedding an Interpretive Qualitative Approach within a Randomized Clinical Trial” Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2013; 7 (3):219–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pluye P, Grad RM, Dunikowski LG, Stephenson R. “Impact of Clinical Information-Retrieval Technology on Physicians: A Literature Review of Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Methods Studies” International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2005; 74 (9):745–68. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pocock SJ. “Group Sequential Methods in the Design and Analysis of Clinical Trials” Biomedics. 1977; 64 (2):191–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- Popescu I, Werner RM, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Cram P. “Characteristics and Outcomes of America's Lowest-Performing Hospitals: An Analysis of Acute Myocardial Infarction Hospital Care in the United States” Circulation. 2009; 2 (3):221–7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ruffin MTI, Fetters MD, Jimbo M. “Preference-Based Electronic Decision Aid to Promote Colorectal Cancer Screening: Results of A Randomized Controlled Trial” Preventive Medicine. 2007; 45 (4):267–73. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ruffin MT, Creswell JW, Jimbo M, Fetters MD. “Factors Influencing Choices for Colorectal Cancer Screening among Previously Unscreened African and Caucasion Americans: Findings from a Mixed Methods Investigation” Journal of Community Health. 2009; 34 (2):79–89. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saint Arnault D, Fetters MD. “RO1 Funding for Mixed Methods Research: Lessons Learned from the “Mixed-Method Analysis of Japanese Depression” Project” Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2011; 5 (4):309–29. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scammon DL, Tomoaia-Cotisel A, Day R, Day J, Kim J, Waitzman N, Farrell T, Magill M. “Connecting the Dots and Merging Meaning: Using Mixed Methods to Study Primary Care Delivery Transformation” Health Services Research. 2013; 48 (S2):2181–207. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shaw EK, Ohman-Strickland PA, Piasecki A, Hudson SV, Ferrante JM, McDaniel RR, Jr, Nutting PA, Crabtree BF. “Effects of Facilitated Team Meetings and Learning Collaboratives on Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in Primary Care Practices: A Cluster Randomized Trial” Annals of Family Medicine. 2013; 11 (3):220–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Silka L. “Partnership Ethics” In: Mertens DM, Ginsberg PE, editors. Handbook of Social Research Ethics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 337–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stake R. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stange KC, Crabtree BF, Miller WL. “Publishing Multimethod Research” Annals of Family Medicine. 2006; 4 (4):292–4. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wallace S, Clark M, White J. “‘It's On My iPhone’: Attitudes to the Use of Mobile Computing Devices in Medical Education, A Mixed-Methods Study” BMJ Open. 2012; 2 (4) e001099. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Willms DG. “A New Stage, A New Life: Individual Success in Quitting Smoking” Social Science and Medicine. 1991; 33 (12):1365–71. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson DM, Taylor DW, Gilbert JR, Best JA, Lindsay EA, Willms DG, Singer J. “A Randomized Trial of a Family Physician Intervention for Smoking Cessation” Journal of the American Medical Association. 1988; 260 (11):1570–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yee D, Haddad T, Albain K, Barker A, Benz C, Boughey J, Buxton M, Chien AJ, DeMichele A, Dilts D, Elias A, Haluska P, Hogarth M, Hu A, Hytlon N, Kaplan HG, Kelloff GG, Khan Q, Lang J, Leyland-Jones B, Liu M, Nanda R, Northfelt D, Olopade OI, Park J, Parker B, Parkinson D, Pearson-White S, Perlmutter J, Pusztai L, Symmans F, Rugo H, Tripathy D, Wallace A, Wholley D, Van't Veer L, Berry DA, Esserman L. “Adaptive Trials in the Neoadjuvant Setting: A Model to Safely Tailor Care While Accelerating Drug Development” Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012; 30 (36):4584–6. author reply 88–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1984. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zickmund S, Yang S, Mulvey EP, Bost JE, Shinkunas LA, LaBrecque DR. “Predicting Cancer Mortality: Developing a New Cancer Care Variable Using Mixed Methods and the Quasi-Statistical Approach” Health Services Research. 2013; 48 (S2):2208–23. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2024

Participatory methods used in the evaluation of medical devices: a comparison of focus groups, interviews, and a survey

- Kas Woudstra 1 , 2 ,

- Marcia Tummers 1 ,

- Catharina J. M. Klijn 3 ,

- Lotte Sondag 3 ,

- Floris Schreuder 3 ,

- Rob Reuzel 1 &

- Maroeska Rovers 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 462 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Stakeholder engagement in evaluation of medical devices is crucial for aligning devices with stakeholders’ views, needs, and values. Methods for these engagements have however not been compared to analyse their relative merits for medical device evaluation. Therefore, we systematically compared these three methods in terms of themes, interaction, and time-investment.

We compared focus groups, interviews, and an online survey in a case-study on minimally invasive endoscopy-guided surgery for patients with intracerebral haemorrhage. The focus groups and interviews featured two rounds, one explorative focussing on individual perspectives, and one interactive focussing on the exchange of perspectives between participants. The comparison between methods was made in terms of number and content of themes, how participants interact, and hours invested by all researchers.

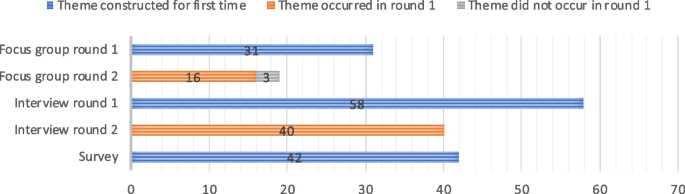

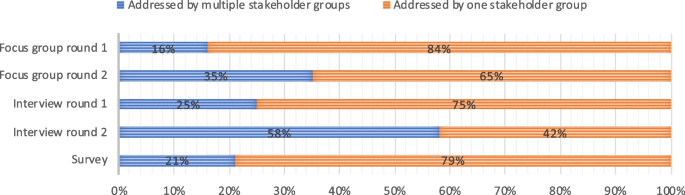

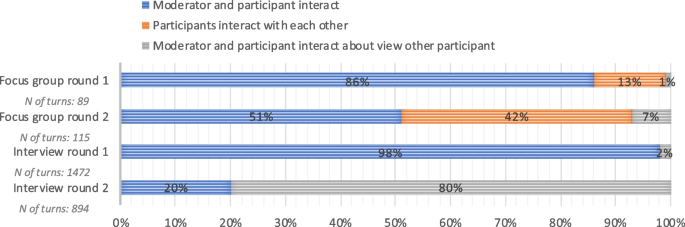

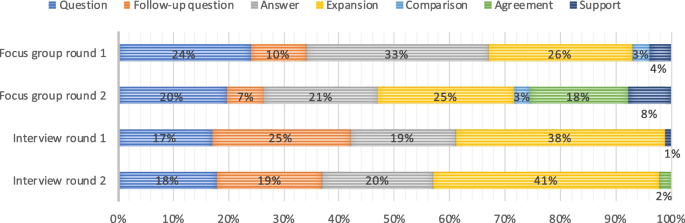

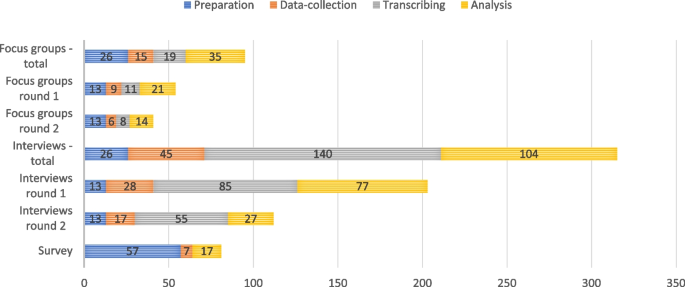

The focus groups generated 34 themes, the interviews 58, and the survey 42. Various improvements for the assessment of the surgical procedure were only discussed in the interviews. In focus groups, participants were inclined to emphasise agreement and support, whereas the interviews consisted of questions and answers. The total time investment for researchers of focus groups was 95 h, of interviews 315 h, and survey 81 h.

Conclusions

Within the context of medical device evaluation, interviews appeared to be the most appropriate method for understanding stakeholder views since they provide a scope and depth of information that is not generated by other methods. Focus groups were useful to rapidly bring views together. Surveys enabled a quick exploration. Researchers should account for these methodological differences and select the method that is suitable for their research aim.

Peer Review reports

Medical devices form an intricate part of the healthcare system. Novel medical devices like robots, nano-technologies, and e-health platforms carry the promise of improving healthcare systems [ 1 ]. As medical devices become more pervasive and complex, it is essential to develop and apply these technologies so that they solve the most pressing medical problems in global healthcare systems. Multiple guidelines and regulations exist that stimulate a practice of medical device research and development that is aimed at solving critical health problems [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. In these documents, one of the recommendations is to actively involve a diverse selection of stakeholders in the research and development process of medical devices. This should lead to better informed decisions during evaluation: aligning devices with the views, needs, and values of stakeholders like medical professionals or patients. This, in turn, can optimise the use of resources spent on research, development, implementation, or use [ 5 ].

There are several methods for stakeholder involvement but these have not been compared against the background of their suitability for medical device evaluation purposes. Studying methods within this context is important, because there are some typical requirements in medical device evaluation. Methods should yield relevant information for research or development choices, preferably foster agreement among stakeholders regarding the future development and implementation of the medical device, and be feasible in terms of resources. By relevant information we mean: any information that helps to understand what features a device should have or how research into a device should be conducted to meet the needs and values of stakeholders. This could involve effectiveness, functionalities, ease of use, affordability, or possible spill overs. By analysing stakeholder needs and practices and making consequent design changes, medical devices can become more valuable [ 6 , 7 ]. Fostering agreement is important to ensure that a device is sufficiently endorsed to make implementation successful. This requires interaction between stakeholders to find common ground [ 8 ]. In entrepreneurial settings where resources are limited and the life-cycle of medical devices is relatively short, development trajectories generally cannot be too long and costly [ 9 ]. Participatory methods can—on the other hand – give insights into development, evaluation, and implementation issues that can occur, and therefore possibly save costs. Due to these unique conditions, it is important to specifically analyse participatory methods in the context of medical device evaluation or development. Some general comparisons of interviews, focus groups, and surveys exist terms of effect on outcomes exist, but these comparisons are not directly applicable to medical devices, nor are they compared all three together [ 10 , 11 , 12 ].

Interviews and focus groups are the most often-used methods in participatory research of medical devices and therefore we compare these in this study [ 13 ]. Surveys are chosen because they are also used in qualitative research and because they methodologically differ on various aspects from interviews and focus groups [ 13 ]. Qualitative surveys offer open text boxes and therefore researchers cannot ask follow-up questions, and there is no direct interaction between researchers and participants. Therefore, we aimed to investigate how focus groups, interviews, and a survey compare in terms of the number of relevant themes they provide, interaction between stakeholders, and time-investment, when conducted in the context of the evaluation of a medical device.

Comparison in one clinical case