BOLDFACE 101: THE CREATIVE WRITING PEER REVIEW

Workshops are an integral and exciting part of the Boldface experience. At first, however, they can seem intimidating. Don’t worry! This week’s installment of Boldface 101 introduces you to the process of giving and receiving peer reviews.

First and foremost, we urge you to prepare in advance. Thinking deeply about your critiques and making meaningful comments is important. Your classmates are there for the same reasons you are—to improve their writing. Don’t dismiss your role as peer and colleague, what you say matters! We hope you’ll check out the following pointers on giving and receiving feedback.

Giving Feedback to Fellow Writers

The golden rule is universal. Treat your peers and their writing with care and respect. Take this part of the writers conference seriously. You wouldn’t like it if others were inconsiderate of you or your work, so be mindful of how you present your comments. Beyond that, requirements are flexible. Your workshop leader will provide guidance in advance regarding how they want you to approach the process, but here are a few best practices to consider in the meantime:

- Avoid saying what you did or didn’t “like.” These kinds of statements have more to do with opinion and less to do with what is or is not successful in a given piece of writing. You don’t always have to “like” something to see whether it’s worthwhile or whether it’s accomplishing its goal as technique or craft.

- Provide constructive criticism AND reinforcement. It’s always nice to hear what you ARE doing effectively as a writer. Remember to encourage your peers when you spot something you think is especially effective, rather than letting it go unsaid and focusing 100% of your critique on what still needs improvement.

- Be specific. Generic and vague comments aren’t very helpful in a creative writing workshop. Your peer review isn’t going to be useful unless it contains detailed analysis and examples of what is/isn’t working in a piece of writing. Make sure to be specific and elaborate on your ideas.

- Check for author notes. If your peer has asked for feedback on a specific issue, make sure to address their concerns!

Don’t forget—you’ll be receiving feedback, too! Here are some things to remember when receiving constructive criticism:

- It’s not personal. So, don’t take it personally. We understand this is easier said than done, especially when it comes to your writing. But that’s just it. It’s your writing, not you, that’s being critiqued.

- Listen actively and to understand. In other words, don’t just give in to your first reaction, which may be purely defensive. Let your peers complete their thoughts and explain what they mean. Take some time to consider things before deciding whether to incorporate or leave out suggestions.

- Stay open-minded. You might receive some radical insights, but sometimes it’s helpful to try unexpected ideas! Perhaps your short story is the beginning of a novel, or a plot twist reveals itself. Writing is a magical process that can lead you down new paths if you let it. So, try to remain open to possibilities!

- Ask questions! If you don’t understand something, don’t hesitate to ask your group to clarify. That is, after all, why they’re there!

“Imagine spending the day at a coffeeshop filled with unique, passionate, intelligent writers who want to share their knowledge—and listen to you in kind. Now imagine doing that for five days in a row. That’s Boldface.” -Boldface 2017 Participant

We think you’ll find that meeting with the same group multiple times throughout the week makes for a close-knit and supportive environment. Hopefully, this brief guide to the creative writing workshop eliminates any uncertainties you may have. If not, let us know! Reach out anytime to [email protected] , or better yet, get involved in the conversation on Facebook , Twitter , and Instagram !

Don’t forget to check out the rest of the Boldface blog for the scoop on our awesome visiting writers and other useful information. Happy writing (and reviewing)!

Theme: Illdy . Copyright 2021. © All Rights Reserved.

Peer Review

About this Strategy Guide

This strategy guide explains how you can employ peer review in your classroom, guiding students as they offer each other constructive feedback to improve their writing and communication skills.

Research Basis

Strategy in practice, related resources.

Peer review refers to the many ways in which students can share their creative work with peers for constructive feedback and then use this feedback to revise and improve their work. For the writing process, revision is as important as drafting, but students often feel they cannot let go of their original words. By keeping an audience in mind and participating in focused peer review interactions, students can offer productive feedback, accept constructive criticism, and master revision. This is true of other creative projects, such as class presentations, podcasts, or blogs. Online tools can also help to broaden the concept of “peers.” Real literacy happens in a community of people who can make meaningful connections. Peer review facilitates the type of social interaction and collaboration that is vital for student learning.

Peer review can be used for different class projects in a variety of ways:

- Teach students to use these three steps to give peer feedback: Compliments, Suggestions, and Corrections (see the Peer Edit with Perfection! Handout ). Explain that starting with something positive makes the other person feel encouraged. You can also use Peer Edit With Perfection Tutorial to walk through the feedback process with your students.

- Provide students with sentence starter templates, such as, “My favorite part was _________ because __________,” to guide students in offering different types of feedback. After they start with something positive, have students point out areas that could be improved in terms of content, style, voice, and clarity by using another sentence starter (“A suggestion I can offer for improvement is ___________.”). The peer editor can mark spelling and grammar errors directly on the piece of writing.

- Teach students what constructive feedback means (providing feedback about areas that need improvement without criticizing the person). Feedback should be done in an analytical, kind way. Model this for students and ask them to try it. Show examples of vague feedback (“This should be more interesting.”) and clear feedback (“A description of the main character would help me to imagine him/her better.”), and have students point out which kind of feedback is most useful. The Peer Editing Guide offers general advice on how to listen to and receive feedback, as well as how to give it.

- For younger students, explain that you need helpers, so you will show them how to be writing teachers for each other. Model peer review by reading a student’s piece aloud, then have him/her leave the room while you discuss with the rest of the class what questions you will ask to elicit more detail. Have the student return, and ask those questions. Model active listening by repeating what the student says in different words. For very young students, encourage them to share personal stories with the class through drawings before gradually writing their stories.

- Create a chart and display it in the classroom so students can see the important steps of peer editing. For example, the steps might include: 1. Read the piece, 2. Say what you like about it, 3. Ask what the main idea is, 4. Listen, 5. Say “Add that, please” when you hear a good detail. For pre-writers, “Add that, please” might mean adding a detail to a picture. Make the chart gradually longer for subsequent sessions, and invite students to add dialogue to it based on what worked for them.

- Incorporate ways in which students will review each other’s work when you plan projects. Take note of which students work well together during peer review sessions for future pairings. Consider having two peer review sessions for the same project to encourage more thought and several rounds of revision.

- Have students review and comment on each other’s work online using Nicenet , a class blog, or class website.

- Have students write a class book, then take turns bringing it home to read. Encourage them to discuss the writing process with their parents or guardians and explain how they offered constructive feedback to help their peers.

Using peer review strategies, your students can learn to reflect on their own work, self-edit, listen to their peers, and assist others with constructive feedback. By guiding peer editing, you will ensure that your students’ work reflects thoughtful revision.

- Lesson Plans

- Strategy Guides

Using a collaborative story written by students, the teacher leads a shared-revising activity to help students consider content when revising, with students participating in the marking of text revisions.

After analyzing Family Pictures/Cuadros de Familia by Carmen Lomas Garza, students create a class book with artwork and information about their ancestry, traditions, and recipes, followed by a potluck lunch.

Students are encouraged to understand a book that the teacher reads aloud to create a new ending for it using the writing process.

While drafting a literary analysis essay (or another type of argument) of their own, students work in pairs to investigate advice for writing conclusions and to analyze conclusions of sample essays. They then draft two conclusions for their essay, select one, and reflect on what they have learned through the process.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Writers Workshop

Conducting Peer Review

Why include peer review in your course.

Writers need feedback on their writing in order to improve. While instructor feedback is valuable, asking students to respond to each other’s writing provides additional opportunities for before-the-deadline feedback without increasing the instructor’s workload.

There are other benefits to peer review, as well: Peer review fosters students’ awareness of their own and others’ writing processes and approaches to the writing task. It gives students practice assessing their own and others’ writing and can reinforce course-specific criteria for writing assignments. Moreover, by both giving and receiving critical feedback, peer review teaches valuable skills like listening, evaluating, responding, and reflecting. Incorporating peer review in your class allows students to gain multiple perspectives on their writing, mimicking the process of peer review in professional knowledge production. Finally, having students engage in active dialogue about their intentions and ideas contributes to a collaborative classroom community.

But Don’t Most Students Hate Peer Review?

Peer review sometimes has a bad reputation. Some students (and instructors) view peer review as unproductive because they’ve received advice that’s too nice or too vague to be helpful, too critical to be constructive, or too focused on surface-level editing issues rather than content. You can overcome these negative perceptions by effectively structuring peer review as a regular course component.

What are Best Practices for Peer Review?

To ensure that peer review benefits both the writer and the reader and leads to substantial revision, instructors need to set ground rules. First, the basics:

- Peer review can be conducted in or out of class, in-person or electronically

- Peer review can be conducted in pairs or groups (many writing scholars recommend groups of 3-4)

- Peer review can be conducted in any number of ways, from having students exchange papers in class to using peer review programs like SWoRD .

- Peer review will need to happen more than once for students to gain practice and fluency

- Peer review should be conducted at least several days before the final submission deadline, to give students enough time make large-scale revisions

- Provide clear parameters and require a deliverable, e.g., a form / handout or a letter to the writer

- Provide coaching and guidance to help students become better peer reviewers

Instructors should prepare students for peer review by discussing your expectations with the class: What makes feedback helpful or unhelpful? What meaningful feedback can writers take from their readers? What criteria should be used to review papers in this class? Consider providing examples or models of the kind of feedback you’d like students to provide.

Effective peer review is a guided, structured process. You’ll need to provide students with focused tasks or criteria. Encourage them to consider their drafts as “works-in-progress” and prompt them to use description rather than evaluative language. For example:

Instead of “Does the paper have a thesis statement” try “In just one to two sentences, state what position you think the writer is taking. Place stars around the sentence that you think presents the thesis.”

Instead of “Is the paper clearly organized?” try “On the back of this sheet, make an outline of the paper.”

Instead of “Is the paper clearly written” try “Highlight (in any color) any passages you had to read more than once to understand what the writer was saying.”

Students should also indicate at least one thing their peer’s writing is doing well. Students aren’t always aware of what’s working in their texts, so having peers provide positive feedback helps them gain insight into readers’ responses.

Instructors can foster metacognition and agency in the writing process by asking writers to prepare memos for their reviewers that contain a brief summary of the paper’s argument and questions pertaining to the current issues they’re struggling with, e.g., “How persuasive is my argument? What additional evidence could I incorporate? Does my paragraph on p. 2 seem too long?”

Finally, for peer review to work, instructors will need to teach revision and talk with students about how to handle constructive criticism. Often, students make changes related to “low-hanging fruit”—wrong words, missed citations—and avoid taking on larger revision challenges, like restructuring a paper or incorporating more persuasive evidence. Those larger changes can be daunting. Remind students that you care more about macro-level issues like content, structure, and genre conventions. You might ask students to write a memo or reflection summarizing their peer review feedback: What revision tasks will they prioritize? What will be most time-consuming? How will they take steps to address the most challenging or time-consuming revision tasks?

You might even share your own strategies for taking on large-scale revision tasks!

Additional Resources:

- Includes general guidelines and a model for structuring peer review

- Planning for peer review

- Helping students offer effective feedback

- Providing guidance on using feedback

- Sample peer review sheets

- Bean, J. (2011). Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom . 2 nd Ed., Chapter 15, “Coaching the Writing Process and Handling the Paper Load”

Related Links:

- Responding to Student Writing

- Incorporating Feedback

Copyright University of Illinois Board of Trustees Developed by ATLAS | Web Privacy Notice

- Our Mission

Centering Classroom Values in Peer Writing Workshops

By structuring peer feedback processes with intention, teachers can help students develop reflection and communication skills.

“What is more challenging for you—giving feedback or receiving feedback? Why do you think that is?”

I project this question on the board when students walk into our peer writing workshop. Along with helping them enter into the activity, it reveals the purpose driving our work: to become stronger at providing and receiving feedback—skills that translate beyond the classroom.

Peer workshops are some of the best days in our classroom. Below, I share practices I’ve found effective when facilitating these interactions in the writing classroom, transferable across units and contexts.

Teacher Preparation

There are many approaches to peer feedback, but over the years I’ve found two priorities key in the planning stage:

- Being intentional about the piece of writing students share. Less is more. Setting constraints for shorter pieces saves time on feedback day. And having the first peer workshop take place with creative or narrative writing allows students to get to know each other, as opposed to analytical or more standardized prompts.

- Establishing classroom values around growth and generosity. We introduce and reflect upon classroom core beliefs at the start of the year, centering these values. We circle back to them frequently; very intentionally, our classroom environment becomes a collaborative one—a critical precursor to peer workshops.

I also give students time in class to plan and write pieces they will workshop. Giving them time helps them feel confident and prepared and allows them to get support in person if needed.

Pre-Workshop Reflection

No matter how prepared students feel, they will likely also feel some anxiety on workshop day—a natural part of sharing work with others.

I begin by having students go through these four norms as a class, selecting one they want to prioritize and sharing their selection with their group members:

- Generosity: Assuming 100 percent in your peers and giving 100 percent as a result in terms of investment and feedback.

- Curiosity: Entering into the space with a willingness to learn from the writing and feedback of those around you .

- Growth: Prioritizing how you can grow, not only in your own writing but also in receiving and providing feedback.

- Perspective: Valuing and engaging with how your own way of seeing things may be different than others’.

By talking through these norms and sharing priorities, students feel a sense of ownership and intentionality entering into workshopping—and practice important real-life self-advocacy skills.

As we begin the workshop, I have students attach a template to their draft for peers to fill out, by hand or digitally, thereby structuring feedback. Our template is built around Marisa Thompson’s close-reading TQE method , with students recording thoughts and questions as they read, noting the most important line and describing why, then noting an epiphany or major takeaway.

Next, students write their own “driving question” at the top of the feedback template—what do they want those reading their piece to focus on, or what are they most curious about regarding others’ perspectives? Naming the focus area you’d most like feedback on is another element of self-advocacy.

Finally, students share digital drafts, asking reviewers to make copies so that writers can’t see the feedback process as it unfolds and are able to stay present with the draft they’re reviewing.

Silent Workshopping

I require the classroom to be 100 percent silent during the feedback stage. Students are typically in trios, which means they have two peer writing samples to review. We split the silent feedback time in half, and I tell them when to switch to the next draft. I ask them to hold clarifying questions and commentary to stay true to our norm of being 100 percent invested in the feedback being provided.

For shorter texts (e.g., 200-to-300-word flash fiction), they get approximately 10 minutes per piece for reading and feedback, doing their best to complete the template. This becomes a really cool space too, as you can almost feel students drifting away from initial anxieties while losing themselves in the reading of each other’s work and the offering of intentional, constructive feedback.

Collaborative Workshopping

When it comes time to share feedback, I ask students to listen to feedback aloud without opening up their own text that is now filled with written feedback. Instead, they listen silently as both of their partners explain their noticings and wonderings first—a process designed to prioritize listening and being a willing recipient of feedback.

A few tips I’ve acquired over the years make this a smoother process:

- Outline the process and project instructions early on. For example, “Partner A will receive feedback from Partner B and Partner C, and then….” Once students dive in, it’s hard to slow them down!

- Have feedback recipients take notes. This gives them a place to prepare follow-up questions and clarifications while actively listening to feedback—another “beyond the classroom” skill.

- Allow groups to move at their own pace. I used to have minute-by-minute plans, but I’ve realized it’s much better to give each group space to move on only when they’re ready. To accommodate this, I have an independent reflection activity ready for them—that way, space is there for some groups to take longer than others.

Significance

After feedback exchanges, we return to our norms, asking students to reflect on how they lived up to their intentions and what it was like to give and receive feedback—making this a dual-learning experience.

To me, the true value of this activity is what it does for the learning community. If a classroom relies only on the eyes of a single teacher to provide feedback and support for everyone within it, that really limits where the community can go as writers.

When we lean into peer feedback and collaborative learning as a purposeful foundation of the classroom, we create an entirely different ceiling as far as what students can achieve—and, in the process, equip students with feedback and reflection skills that go far beyond any specific writing skill.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

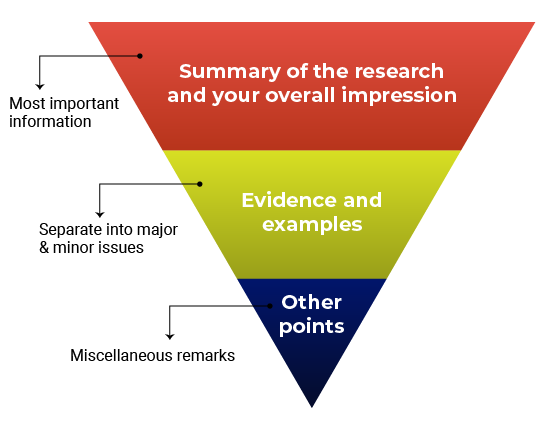

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Teaching Autoethnography

4. Workshop and Peer Review Process

It is essential as the instructor to create space in the classroom for the students where they feel free to comment on and discuss each other’s work. Your feedback is important, and so is the feedback they receive from their peers.

For all major assignments, I give students narrative written feedback. I do not copy edit or make a large number of marginal comments. I find in my experience that the more you can tell a story in your feedback, the easier it is for the students to process and incorporate your comments. This may not be a method that works for everyone, but I have found it to produce the best conversations and results.

In the remainder of this chapter, I will outline the two major methods I use to help students give peer feedback.

As often as possible, I try to make time in the class schedule for a large class workshop. This means each student will get to read her or his entire short work to the class for feedback. At my home institution, we are lucky to have a manageable class size of eighteen or twenty for our writing courses, making the full class workshop possible for everyone. If you have a larger class, you can alternate workshopping assignments, splitting up students so that only a few read each class period, making sure that everyone gets at least one chance to receive a full class workshop on a piece over the course of the semester. Another alternative when time in limited is to ask them to engage in a common practice of sampling sections of their longer pieces to share with the entire class. This mimics the process of a public reading in which authors are often asked to share pieces of longer works in hopes of encouraging the audience to want to read more. It is an important skill to develop and helps students see where the heart of a piece lies.

The rules I use for a workshop are common practice for many creative writing classes. Students are asked to read their work as written without any explanation. This helps the class hear the work as it appears on the page, closer to the experience of an outside reader unfamiliar with the person behind the writing and that person’s reasons for writing it. We have the added advantage of hearing each student’s voice, and this is also good practice for students who might want to share their work in a larger forum.

When students first share their work with the class, we follow a few simple rules. I draw a lot of principles for initial workshops from the Amherst Writers & Artists method. Pat Schneider’s book Writing Alone and With Others is a great resource and includes guidelines to build support and community in writing groups. Drawing on Schneider’s book, we offer only positive feedback to each other initially. This kind of feedback can include what we liked about the text, what stood out to us, what we remembered. This creates a safe space for the students to share first drafts of their writing. This work has not been critiqued or significantly edited, so sharing out loud and commenting in this way helps build student confidence. Students read in succession without pause. I encourage them to jot down things they like during the readings or to just take careful notice of what stands out to them. We then share our thoughts as a group. I also participate, reading work of my own and taking notes to model the behavior. This is a great way for students to get to know and trust each other and you. They start building community by referring to each other by name with the aid of name tags they keep on their desks for the first four weeks of class. If room allows, it also helps to have everyone sit in a circle when sharing.

Peer Review

Peer review is an essential part of the writing process. To facilitate review beyond the larger class workshop, which is not possible for extended pieces due to time constraints, I break students into small groups of three to five members, depending on class size, and have them exchange drafts. The first thing students do is write down concerns they have about their own writing. These concerns may include doubts about whether the text is cohesive, anyone will care about the topic, or a particular sentence is properly structured. Each then shares these concerns with a peer reviewer, who takes them into account when reading and reviewing the essay. The reviewers are asked first to read the writers’ concerns, second to put down their pens and read the entire draft from top to bottom, then third to respond in writing to the writers’ concerns and a sheet of peer review questions. I have included sample questions here that can work for any of the extended drafts with minor modifications. I help students keeps track of time and encourage them to spend forty to fifty minutes with each draft, especially the first time they are doing this. The students usuallyfinish at about the same time with my help. Once they have finished, they exchange written comments. The writers then read the feedback they were given and talk with their peer reviewers to clarify questions they have about the feedback and discuss overall impressions.

By doing peer reviews this way, students are able to have meaningful conversations with peers about their work, have the opportunity to see in detail how someone else chose to approach the assignment, and have written feedback and notes to take home for reference as they revise. Although students may understand feedback at the time of review, they may have forgotten much of the conversation by the time they are able to revise the paper. Having the written notes helps with this problem. As previously mentioned, I also always provide detailed feedback on student drafts of longer papers.

A sample three-week timeline for the formal paper might look like this: I ask students to turn in a draft for peer review during the first week. I ask students to bring two copies of their drafts so that during the class session I can do my first read of their work. This allows me to answer any immediate questions that come up during peer reviews or address concerns they want to begin working on right away. I provide detailed student feedback in the second week. I have a larger class discussion with the students about patterns I see in the writing so that we can have an open dialogue and share concerns. The final draft is due in the third week. Students are asked to submit the original draft, my comments, both peer reviews and their final draft. This way I can evaluate the process from top to bottom. For instance, if both peer reviewers and I suggest a revision to the introduction, I will expect a student to address this concern. In reviewing feedback, I encourage students to listen to their peers and to my feedback but ultimately to make their own decisions about how they want to revise their essays. The grade I assign is an assessment of where each essay is in relation to the progress I think it should make in the class.

Because of its creative nature, many students are interested in the prospect of publishing their personal writing. This may be different from what you have experienced in a typical first-year writing classroom. At this point, the students will have read a wide variety of pieces from essayists, fiction writers and journalists. With a variety of topics and perspectives represented, students will be able to identify with some of the writers and wish to join the conversation in a more public way. In class, I explain that publishing an essay requires another process, one that would take considerably more time and different audience awareness to achieve. We strive for progress within the limitations and scope of the semester, and I offer to meet with students individually to discuss paths to publication.

Peer Review Sheet (Sample)

Writer, please identify any issues you feel you are currently having with this piece of writing so that your reader/reviewer can focus on these issues.

How well does the author set up the idea of place/event in this piece? Point to specific details that give the concept of character dimension or stifle it on the page.

Are you able to get a clear sense of setting? How well do you feel situated in the environment of the piece? Explain how this feeling is achieved, citing details from the writing.

Does the author give enough personal background to situate the importance of the place/event as well as his or her own point of view? If so, what details help the author do this? If not, what do you think is missing?

Does the piece seem to flow from beginning to end? Is there a natural progression of characters and story line? If so, how is this accomplished? If not, how can the author make the piece flow more effectively?

Where does the story begin, and where does the story leave you? Do you feel you are able to enter the narrative easily and let it end where it does? Why or why not?

Is there specific language that you feel is particularly expressive and effective in this piece? If so, point it out here.

Is there specific language that you feel is somewhat stilted or dragging the narrative pace? If so, point it out here.

Do you have any additional suggestions or comments for revision? Please also feel free to use this space to express what you like best about the piece of writing.

I use a variety of readings to demonstrate different forms to the class. Even in a short period of time, it is important to expose students to many forms of personal writing, not just one. I also include forms other than nonfiction, such as fiction and poetry, to demonstrate writing styles. I cannot encourage you enough to choose readings that are appropriate for your own student body. What works for my students may very well not work for yours. My advice would always be to represent a diverse range of experiences to give students more opportunity to find a voice they can relate to and possibly identify with. I will include some sample readings throughout the chapters to give examples of readings that have worked in my classroom.

Teaching Autoethnography: Personal Writing in the Classroom Copyright © by Melissa Tombro is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Peer Review

The formula for writing a peer review is an organized process, but it’s easy to do when you follow a few simple steps. Writing a well-structured peer review can help maintain the quality and integrity of the research published in your field. According to Publons, the peer-review process “teaches you how to review a manuscript, spot common flaws in research papers, and improve your own chances of being a successful published author.” Listed below are four key steps to writing a quality peer review.

1. Read the manuscript in its entirety

It is important to read the manuscript through to make sure you are a good fit to assess the research. Also, the first read through is significant because this is when you develop your first impression of the article. Should a reviewer suspect plagiarism of any kind, s/he should contact the journal office at [email protected] .

2. Re-read the manuscript and take notes

After the first read through, you can now go back over the manuscript in more detail. For example, you should ask the following questions about the article to develop useful comments and critiques of the research and presentation of the material:

- Is this research appropriate for the journal?

- Does the content have archival value?

- Is this research important to the field?

- Does the introduction clearly explain motivation?

- Is the manuscript clear and balanced?

- Is the author a source of new information?

- Does the paper stay focused on its subject?

- Are the ideas and methods presented worthwhile, new, or creative?

- Does the paper evaluate the strengths and limitations of the work described?

- Is the impact of the results clearly stated?

- Is the paper free from personalities and bias?

- Is the work of others adequately cited?

- Are the tables and figures clear, relevant, and correct?

- Does the author demonstrate knowledge of basic composition skills, including word choice, sentence structure, paragraph development, grammar, punctuation, and spelling?

Please see SAE’s Reviewer Rubric/Guidelines for a complete list of judgment questions and scoring criteria that will be helpful in determining your recommendation for the paper.

3. Write a clear and constructive review

Comments are mandatory for a peer review . The best way to structure your review is to:

- Open your review with the most important comments—a summarization of the research and your impression of the research.

- Make sure to include feedback on the strengths, as well as the weaknesses, of the manuscript. Examples and explanations of those should consume most of the review. Provide details of what the authors need to do to improve the paper. Point out both minor and major flaws and offer solutions.

- End the review with any additional remarks or suggestions.

There can be various ways to write your review with the structure listed above.

Example of comprehensive review

Writing a bad review for a paper not only frustrates the author but also allows for criticism of the peer-review process. It is important to be fair and give the review the time it deserves. While the comments below may be true, examples are needed to support the claims. What makes the paper of low archival value? What makes the paper great? In addition, there are no comments for suggestions to improve the manuscript, except for improving the grammar in the first example.

Examples of bad reviews:

- Many grammatical issues. Paper should be corrected for grammar and punctuation. Very interesting and timely subject.

- This paper does not have a high archival value; should be rejected.

- Great paper; recommend acceptance.

4. Make a recommendation

The last step for a peer reviewer is making a recommendation of either accept, reject, revise, or transfer. Be sure that your recommendation reflects your review. A recommendation of acceptance upon first review is rare and only to be used if there is no room for improvement.

Additional Reviewer Resources

- Example Review

- Advice and Resources for Reviewers from Publons

- Peer Review Resources from Sense about Science

For questions regarding SAE’s peer-review process or if you would like to be a reviewer, please contact [email protected] .

For questions on how to review in Editorial Manager®, please see Editorial Manager® Guide for Reviewers .

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1: Intro to Creative Writing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 132138

- Sybil Priebe

- North Dakota State College of Science via Independent Published

chapter 1: intro to creative writing:

Creative writing\(^7\) is any writing that goes outside the bounds of “normal”\(^8\) “professional,”\(^9\) journalistic, “academic,”\(^{10}\) or technical forms of literature, typically identified by an emphasis on narrative craft, character development, and the use of literary tropes or with various traditions of poetry and poetics. Due to the looseness of the definition, it is possible for writing such as feature stories to be considered creative writing, even though they fall under journalism, because the content of features is specifically focused on narrative and character development.

Both fictional and nonfictional works fall into this category, including such forms as novels, biographies, short stories, and poems. In the academic setting, creative writing is typically separated into fiction and poetry classes, with a focus on writing in an original style, as opposed to imitating pre-existing genres such as crime or horror. Writing for the screen and stage—screenwriting and playwrighting—are often taught separately but fit under the creative writing category as well.

Creative writing can technically be considered any writing of original composition.

the creative process: \(^{11}\)

Some people can simply sit down to write and have something to write about. For others, finding something to write about can be the hardest part of creative writing. Assuming that you are not in the first group, there are several things you can do to create ideas. Not all of these will work for all people, but most are at least useful tools in the process. Also, you never know when you might have an idea. Write down any ideas you have at any time and expand on them later.

For stories and poetry, the simplest method is to immerse yourself in the subject matter. If you want to write a short story, read a lot of short stories. If you want to write a poem, read poems. If you want to write something about love, read a lot of things about love, no matter the genre.

the writing process “reminder”\(^{12}\)

Please Note: Not all writers follow these steps perfectly and with each project, but let’s review them to cover our butts:

BRAINSTORMING

PROOFREADING

Outline\(^{13}\) your entire story so you know what to write. Start by writing a summary of your story in 1 paragraph. Use each sentence to explain the most important parts of your story. Then, take each sentence of your paragraph and expand it into greater detail. Keep working backward to add more detail to your story. This is known as the “snowflake method” of outlining.

getting started:

Find a comfortable space to write: consider the view, know yourself well enough to decide what you need in that physical space (music? coffee? blanket?).

Have the right tools: computer, notebook, favorite pens, etc.

Consider having a portable version of your favorite writing tool (small notebook or use an app on your phone?).

Start writing and try to make a daily habit out of it, even if you only get a paragraph or page down each day.

Keys to creativity: curiosity, passion, determination, awareness, energy, openness, sensitivity, listening, and observing...

getting ideas:

Ideas are everywhere! Ideas can be found:

Notebook or Image journal

Media: Magazines, newspapers, radio, TV, movies, etc.

Conversations with people

Artistic sources like photographs, family albums, home movies, illustrations, sculptures, and paintings.

Daily life: Standing in line at the grocery store, going to an ATM, working at your campus job, etc.

Music: Song lyrics, music videos, etc.

Beautiful or Horrible Settings

Favorite Objects

Favorite Books

How to generate ideas:

Play the game: "What if..."

Play the game: "I wonder..."

Use your favorite story as a model.

Revise favorite stories - nonfiction or fiction - into a different genre.

writer's block:\(^{14}\)

Writer’s block can happen to ANYONE, so here are some ways to break the block if it happens to you:

Write down anything that comes to mind.

Try to draw ideas from what has already been written.

Take a break from writing.

Read other peoples' writing to get ideas.

Talk to people. Ask others if they have any ideas.

Don't be afraid of writing awkwardly. Write it down and edit it later.

Set deadlines and keep them.

Work on multiple projects at a time; this way if you need to procrastinate on one project, you can work on another!

If you are jammed where you are, stop and write somewhere else, where it is comfortable.

Go somewhere where people are. Then people-watch. Who are these people? What do they do? Can you deduce\(^{15}\) anything based on what they are wearing or doing or saying? Make up random backstories for them, as if they were characters in your story.

peer workshops and feedback acronyms: \(^{16}\)

Having other humans give you feedback will help you improve misunderstandings within your work. Sometimes it takes another pair of eyes to see what you “missed” in your own writing. Please try not to get upset by the feedback; some people give creative criticism and others give negative criticism, but you will eventually learn by your own mistakes to improve your writing and that requires peer review and feedback from others.

If you are comfortable having your friends and family read your work, you could have them\(^{17}\) peer review your work. Have a nerdy friend who corrects your grammar? Pay them in pizza perhaps to read over your stuff!? If you are in college, you can use college tutors to review your work.

Peer Workshop activities can help create a “writing group vibe” to any course, so hopefully, that is a part of the creative writing class you are taking.

WWW and TAG

The acronyms involved with feedback – at least according to the educators of Twitter – are WWW and TAG. Here’s what they stand for, so feel free to use these strategies in your creative writing courses OR when giving feedback to ANYONE.

Are you open to the kinds of feedback you’ll get using that table above with the WWW/TAG pieces?

What do you typically want feedback on when it comes to projects? Why?

What do you feel comfortable giving feedback to classmates on? Why?

\(^7\)"Creative Writing." Wikipedia . 13 Nov 2016. 21 Nov 2016, 19:39 < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_writing >. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

\(^8\)Whoa, what is normal anyway?

\(^9\)What IS the definition of “professionalism”?

\(^{10}\)Can’t academic writing be creative?

\(^{11}\)"Creative Writing/Introduction." Wikibooks, The Free Textbook Project . 10 May 2009, 04:14 UTC. 9 Nov 2016, 19:39

< https://en.wikibooks.org/w/index.php...&oldid=1495539 >. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

\(^{12}\)It doesn’t really matter who created it; all you need to know is that you don’t HAVE to follow it perfectly. Not many people do.

\(^{13}\)Wikihow contributors. "How to Write Science Fiction." Wikihow. 29 May 2019. Web. 22 June 2019. http://www.wikihow.com/Write-Science-Fiction . Text available under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

\(^{14}\)"Creative Writing/Fiction technique." Wikibooks, The Free Textbook Project . 28 Jun 2016, 13:38 UTC. 9 Nov 2016, 20:36

< https://en.wikibooks.org/w/index.php...&oldid=3093632 >. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

\(^{15}\)Deduce = to reach a conclusion.

\(^{16}\)"Creative Writing/Peer Review." Wikibooks, The Free Textbook Project. 16 Aug 2016, 22:07 UTC. 9 Nov 2016, 20:12

< https://en.wikibooks.org/w/index.php...&oldid=3107005 >. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

\(^{17}\)This textbook we’ll try to use they/them pronouns throughout to be inclusive of all humans.

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Blog • Perfecting your Craft

Posted on Sep 04, 2019

49 Places to Find a Critique Circle to Improve Your Writing

Contrary to popular belief, writers aren’t solitary creatures by default. In fact, we’re often better when we write together , swapping trade secrets and exchanging manuscripts for mutual critique. Unfortunately, accidents of geography can stop us from congregating as often as we’d like. We don’t all live in literary hubs like London and NYC, so finding a critique circle in real life can be a bit of a challenge.

Luckily, you don’t have to be limited by the vagaries of place: there are plenty of online spaces where you can find writing partners ( and their excellent tips ). From the Critique Circle — the internet’s most famous writing group — to the more intimate critique groups studding the netscape, it’s easy enough to find gimlet-eyed readers ready to bring out the potential in your works-in-progress.

We’ve rounded 51 places to get feedback on your work. General writing critique groups are at the top, and genre-focused communities at the bottom. Because, to paraphrase the Starks of Winterfell , if the lone wolf dies while the pack survives, the lone writer struggles while the critique circle thrives.

GENERAL CRITIQUE GROUPS

1. Critique Circle

Most of this list is in alphabetical order, but Critique Circle is so well-known it’s worth breaking the mold. This Iceland-based community has a no-frills aesthetic. But since it opened in 2003, it’s offered more than 700,000 critiques for over 140,000 stories. Members sign up for free and earn credits — needed to put their work up for review — by offering feedback to other users. Every 3 reviews earns you enough credits to “buy” an opportunity to post.

Freshly enrolled writers have their work scheduled in a Newbie Queue, which sends their writing out for feedback faster than the regular queue. Word to the wise: the quality of feedback can vary — especially if they come from newbie members still learning the art of constructive criticism. But experienced members stand by to help to newbies as they get comfortable with the process.

Perfect if: You want to check out the internet’s most famous critique group

2. Reedsy Writing Prompts Contest

Yes, this one is facilitated through our very site! Here at Reedsy, we host a weekly writing contest where writers are invited to submit a short story based on one of our writing prompts. Shortly after launching this contest, we noticed a cool thing happening: writers started leaving constructive criticism and feedback on one another's stories — completely un prompted. We decided we wanted to encourage this initiative, so we created a critique circle within the contest.

Here's how it works: sign up for a free Reedsy Prompts account , and submit a short story to one of our contests. Once the contest ends, you'll receive an email asking you to leave feedback on other participants' stories — and the other entrants will likewise be encouraged to leave feedback on your story.

Perfect if: You want the opportunity to earn cash prizes as part of your critique circle experience

3. 10 Minute Novelists Facebook Group

This support group for time-crunched writers runs a weekly #BuddyDay thread every Tuesday, where members can post their work for review. Excerpts are fair game, as are blurbs , author bios, cover art, and the like. If you’d like to test drive a couple of different packages for your indie masterpiece, #BuddyDay might be a good place to start.

Even if it’s not Tuesday, 10 Minute Novelists is a great place to “hang out.” Members commiserate about how real life gets in the way of your literary dreams — and encourage each other to stick it out anyway.

Perfect if: You know you’ve got a novel inside you, but you can’t seem to carve out more than 10 minutes a day to actually write it

4. ABCTales

This free writing community lets members post their own work and comment on each others’ — think WattPad, with way less emphasis on One Direction fanfic. Discussion seems to revolve around how to write a poem to best effect, although some short story writers frequent the forums as well. The feedback tends to be earnest and encouraging. Members happily dole out congratulations at one another’s literary triumphs.

ABCTales emphasizes slow and steady writerly development more than hustling for bylines. The pieces posted on its forums likely won’t be eligible for publication at many mainstream outlets, so they tend to be exercises written for practice, or from sheer love of the craft. That said, there is a forum full of writers swapping tips for publication .

Perfect if: You want a wholesome community to help you hone your craft in a low-stakes way

5. Absolute Write Water Cooler

This sprawling writers’ forum can be a bit of a maze, but there’s a wealth of material to help you along on your writing journey. If you’re in search of critique, you’ll want to make your way to the Beta Readers, Mentors, and Writing Buddies board. It works a little like a craft-focused version of the old Craigslist Personals section. Just post a description of the piece you’re working on, and forum members who fancy giving it a beta read will get in touch.

While you’re waiting for your perfect beta reader to respond to your post, you can hang out on any of Absolute Write ’s other craft-focused message boards. Many are genre-specific: check out Now We’re Cookin’! if you’re into food writing, or Flash Fiction if you’re a fan of pith.

Perfect if: You harbor romantic fantasies of finding your One True Reader on a personals site

6. Christopher Fielden

Christopher Fielden’s website offers tons of free resources – ranging from how to do research, how to keep your creativity fresh, and advice about self-publishing. He also curates a list of writing competitions – whether you’re looking to submit a short story or a poem, there are tons of options to choose from. You can pay for a critique from his team as well and a seasoned writer like Dr. Lynda Nash or Allen Ashley will go over your short story, novel, or poem.

7. Beta Readers and Critique Partners Facebook Group

This Facebook group has been helping writers find beta readers for two years now, and it’s still going strong. Almost 500 new members joined in the last month, bringing the total up to over 7,000. Rest assured, the mods won’t tolerate any nonsense: scorched earth critiques are forbidden, and members are encouraged to be kind at all times.

The Beta Readers and Critique Partners group welcomes members of all skill levels. Participants do their best to keep in mind whether they’re reading a seasoned pro, or someone just getting started as a beta reader . Self-promotion is banned, so don’t worry about being spammed.

Perfect if: You want a group where newbies can freely mingle with seasoned pros

8. Critique It

This peer review tool works like Google Docs on steroids: a group of collaborators can work on the same project, leave each other feedback, and feel like they’re all gathered around the same desk even if they’re actually scattered across the globe. Unlike GDocs, Critique It makes it easy to drop in video and audio files as well. That way, critics can leave their feedback in whatever format they like.

It won’t actually help you find a critique group. But it will let you form one with whoever you choose — no matter where in the world they’re based.

Perfect if: You want to form a writing group with friends from afar

9. The Desk Drawer

Here’s a critique group with high standards: send out multiple submissions that haven’t been spell-checked, and the group just might kick you out. This ultra-active, email-based workshop is a perfect fit for the kind of scribblers who thrive off prompts — and who want to use them to hone their craft in the (virtual) company of fifty-odd like-minded writers. Every week, The Desk Drawer sends out a writing exercise. Members can respond directly to the prompt with a SUB (submission) — or offer a CRIT (critique) of another writer’s response.

To stay on the mailing list, workshoppers have to send out at least three posts a month: 1 SUB and 2 CRITS, or 3 CRITS. And membership is selective: if you’d like to join, you’ll have to send in a short, 100- to 250-word writing sample based on a prompt.

Perfect if: You want some disciplined — but mutually encouraging — writing buddies to keep you honest as you build up a writing habit

10. Fiction Writers Global Facebook Group

Despite its name, this community welcomes writers of fiction and non-fiction alike, although those who work specialize in erotica are encouraged to find an alternative group. At 13 years old, it’s one of the longer-running writing communities on Facebook. The mods have laid down the law to ensure it continues to run smoothly: fundraising, self-promotion, and even memes are strictly banned.

If you’re still weighing the pros and cons of traditional versus self-publishing , Fiction Writers Global might be the perfect group for you. They have members going both these routes who are always happy to share their experiences.

Perfect if: You’re determined to go the indie route — or thinking seriously about it

11. Hatrack River Writers Workshop

This 18+, members-only workshop was founded by renowned speculative fiction writer Orson Scott Card, of Ender’s Game fame , and it’s now hosted by short fiction writer Kathleen Dalton Woodbury. Both these writers cut their teeth on genre fiction, but don’t feel limited to tales of magic and spacefaring — anything goes, except for fanfic.

At the Hatrack River Writers Workshop , members can submit the first 13 lines of a WIP for review — an exercise designed to make sure the story hooks the reader as efficiently as possible . A loosely structured Writing Class forum offers prompts, called “assignments,” designed to help blocked writers start (or finish) stalled works.

Perfect if: You want to polish your story’s opening to a mirror-shine

12. Inked Voices

Unlike the cozy, Web 1.0 vibes of older online critique groups, Inked Voices is as sleek as they come, with cloud-based functionality and an elegant visual brand. Its polished look and feel make sense considering this isn’t so much a writing group as a platform for finding — or creating — writing groups, complete with a shiny workshopping app that has version control and calendar notifications built in.

Each workshop is private, invite-only, and capped at 8 members. You can sign up for a two-week free trial, but after that, the service costs $10 per month, or $75 for the year. Membership also lets you tune in for free to lectures by industry pros.

Perfect if: You’re willing to pay for an intimate, yet high-tech, workshop experience

13. Litopia

This website calls itself the “oldest writers’ colony on the ‘net,” a description that probably proves its age. One of its main draws? The writing groups that allow members to post their WIPs for peer review. The community tends to be friendly and mutually encouraging — probably the reason Litopia has lasted so long.

There’s another major draw: every Sunday, literary agent Peter Cox reviews several 700-word excerpts from members work on-air, in a podcast called Pop-Up Submissions. Cox tackles this process with a rotating cast of industry professionals as his guests. They’ve even been known to ask for a synopsis from a writer who impresses.

Perfect if: You’ve always wanted to spend some time in a writer’s colony, but you can’t jet off to Eureka Springs just yet

14. My Writers Circle

This easy-going discussion forum is light on dues and regulations, but members seem to be friendly and respectful anyway. A stickied thread on the Welcome Board encourages new members to read and comment on at least 3 pieces of writing before posting their own work for review. But this isn’t the kind of hard-and-fast rule that’ll lead to banning if you fall short. Members go along with it because they genuinely care about one another’s writing progress.

My Writers Circle has three dedicated workshop boards that allow forum users to seek feedback on their writing. One, called Review My Work, accepts general fiction and nonfiction, while additional spaces allow poets and dramatists of all kinds to get their verse, plays, and TV scripts critiqued.

Perfect if: You want a community where people are nice because they want to be — not because they have to be

15. Nathan Bransford - The Forums

Nathan Bransford worked as an agent before he switched over to the other side of the submissions process. Now, he’s a published middle-grade novelist and the author of a well-rated, self-published craft book called How to Write a Novel . In the midst of all his success, Bransford gives back to the literary community by running his ultra-popular Forums.

A board called Connect With a Critique Partner functions as matchmaker central for writers seeking their perfect beta readers. And if you’re not looking for something long-term, there’s the Excerpts forum, where you can post a bit of your WIP for quick hit of feedback.

Perfect if: You want to be part of a writing community that’s uber-active, but low-key

16. The Next Big Writer

Since 2005, this cult-favorite workshop has provided thousands of writers with a friendly forum for exchanging critiques. The site boasts an innovative points system designed to guarantee substantive, actionable feedback. To gain access, you’ll have to pay: $8.95 a month, $21.95 a quarter, or $69.95 for the whole year. Fortunately, there’s an opportunity to try before you buy: a 7-day free trial lets you get a taste of what the site has to offer.

The Next Big Writer also hosts periodic contests : grand prize winners receive $600 and professional critiques, while runners-up stand to gain $150 and 3 months of free membership. Meanwhile, all entrants get feedback on their submissions.

Perfect if: You like the sound of a members’ only writing contest with big prizes — in both cash and critique

17. NovelPro

This fiction writing workshop is one of the more costly online communities to join. But it has the rigor of an MFA program, at a tiny fraction of the price. Members — their numbers are capped at 50 — pay $120 a year. And that’s after a stringent application process requiring the first and last chapters of a finished, 60,000-word fiction manuscript and a 250-word blurb. Think of it as a bootcamp for your novel.

Even if an applicant’s writing sample passes muster, they still might not make the cut — there’s also a critique exercise that asks them to pass judgment on a sample novel chapter, with a 2-day turnaround. No wonder prospective NovelPro members are urged to reconsider unless their prose is “accomplished” and their fiction skills “advanced.”

Perfect if: You want a critique group that’ll take your work as seriously as you do

Free course: Novel Revision

Finished with your first draft? Plan and execute a powerful rewrite with this online course from the editors behind #RevPit. Get started now.

18. Prolitfic

Launched by University of Texas students frustrated by the vagaries of the publishing process, this slick, Gen Z-friendly site encourages emerging writers to help each other out with thorough, actionable reviews. Members critique one another’s critiques — dare we call it metacritique? — to keep the quality of feedback high.

Prolitfic 's rating rubric, which assigns all submissions a star rating out of 5, insures that all reviewers are coming from the same place. Reviewers with higher levels of Spark, or site engagement, have their feedback weighted more heavily when the site calculates each submission’s overall rating.

Perfect if: You’re a serious, young writer hoping to find support in a tight-knit community built by your peers

19. Scribophile

One of the best-known writing communities on the web, Scribophile promises 3 insightful critiques for every piece of work you submit. Members earn the right to receive critiques by stocking up on karma points, which they can get by offering feedback on other works. You can get extra karma points by reacting to other users’ critiques — by clicking on Facebook-like buttons that say “thorough,” “constructive,” and the like — and by having your critiques showered with positive reactions.

A free membership lets you put two 3,000-word pieces up for critique, while premium memberships won’t throttle your output — but will cost you either $9 per month or $65 for the year.

Perfect if: You’d like to play with a critique system that has shades of Reddit — but far more civil!

20. SheWrites Groups

This long-standing community for writing women boasts a treasure trove of craft-focused articles. But the site also hosts a wealth of writing groups, split into genres and topics. Whether they work on screenplays, horror novels , or depictions of the environment, women writers can find a group to post their work for feedback — and commiserate on the travails of writing life.

In addition to their articles and writing groups, She Writes also operates a hybrid publishing company that distributes through Ingram and, naturally, brings women’s writing into the light.

Perfect if: You’re a woman writer in search of a friendly community full of like-minded, mutually encouraging folks

21. Sub It Club

Gearing up to submit finished work can be even more daunting than writing it in the first place. If you’d like to get some friendly eyes on your query letters or pitches — in a virtual walled garden away from any agents or publishers — this closed Facebook group might be the perfect place for you.

If you’re in need of more than a one-off review, Sub It Club runs a Critique Partner Matchup group to pair off writing buddies. The group moderators also run a blog with plenty of tips on crafting cover letters, dealing with rejection, and all other parts of the submission process .

Perfect if: You want a private, low-stress setting to get some feedback and vent about life as a yet-to-be-published writer

22. WritersCafe.org

This sizable — but friendly! — community boasts over 800,000 users, all of whom can access its critique forums for free. Members offer feedback to one another at all stages of the writing process: from proofing near-finished pieces to leaving more substantive feedback for still-marinating works.

For more quantitative-minded scribblers, WritersCafe ’s graphs make it easy to visualize how their work is being received. The site also allows members to host their own writing contests — and even courses to share their expertise with fellow Cafe patrons.

Perfect if: You’re a visual, data-driven writer who prefers to think in charts — even when it comes to writing!

23. Writer’s Digest Critique Central

Writer’s Digest is an institution in the literary world, and its critique forum is as popular as you’d expect: it’s collected more than 10,000 threads and nearly 90,000 individual posts over the years.

Critique Central boasts dedicated boards for a variety of genres — poetry is the most popular, with literary fiction next in line. You can also find spaces dedicated to polishing query letters and synopses, and a board that aggregates critique guidelines to make sure every member is giving — and getting — the best feedback possible.

Perfect if: You’d like a one-stop shop for critiquing your WIPs, queries, and synopses

24. The Writers Match

Founded by a veteran children’s book author, The Writers Match aims to, well, match writers with their comrades-in-craft from around the world. Think of it as okCupid for critique partners. Just fill out a profile and then shop for matches on the Members page, where writers will be sorted according to experience and genre.

If you find any promising would-be partners, shoot them a message and see if the literary sparks fly. And if it turns out you don’t quite vibe, there are plenty of other fish in the sea of critique.

Perfect if: You live somewhere without a robust writing community, and you’re tired of missing out

25. Writers World Facebook Group

Founded by veteran editor and sci-fi author Randall Andrews, this critique group welcomes serious writers of book-length prose. Members aim to shepherd each other’s manuscripts through all stages of the publication process, from the developmental edit to the query.

Andrews himself remains heavily involved in Writers World ’s day-to-day activity, pitching in with critiques informed by his 30 years of experience in the publishing industry. He’s also happy to explain his comments, and weighs in periodically with links to useful resources on craft.

Perfect if: You’ve got a book in the works, and you’re in the market for a critique group headed by a mentor who’s extremely generous with his time

26. Writing.Com

This sprawling community has been a meeting point for writers of all levels since 2000, whether their goals are to be published in a top-shelf literary magazine or to score an A in English Composition. Writing.Com users, who work in every genre under the sun, make use of the site’s portfolio system to post their writing and seek feedback from fellow community members.

Free memberships allow users to store up to 10 items in their personal portfolio, while the various tiers of paid membership gradually increase the limit — starting at the 50 items afforded by the $19.95 per year Basic Membership.

Perfect if: You want to be part of an enormous community where you’re sure to encounter a diversity of viewpoints

27. Writing, Prompts & Critiques Facebook Group

Writing, Prompts & Critiques is pretty much exactly what it says on the tin. Members seek critique on posted threads and can also comment on one another’s responses to the group’s daily writing exercises.

Speaking of which: unlike conventional writing prompts, which encourage you to write new work, WPC’s daily challenges try to get you thinking more deeply about your existing projects. So come with a manuscript in hand, and see if the folks here can’t help you make it even better.

Perfect if: You’d like to get some feedback on a WIP — and experiment with some writing exercises to refine it

28. Writing to Publish

This 25-year-old critique group might have an American flag gif on its homepage, but its membership is worldwide. Writing to Publish members meet live in a chat room every other Monday at 7 PM Pacific time — which the website helpfully specifies is lunchtime on Tuesday for Australians.